Evaluating the Community Land Record System in Monwabisi Park Informal Settlement in the Context of Hybrid Governance and Organisational Culture

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Objectives

1.2. Problem Context

1.3. Key Findings

2. Methods

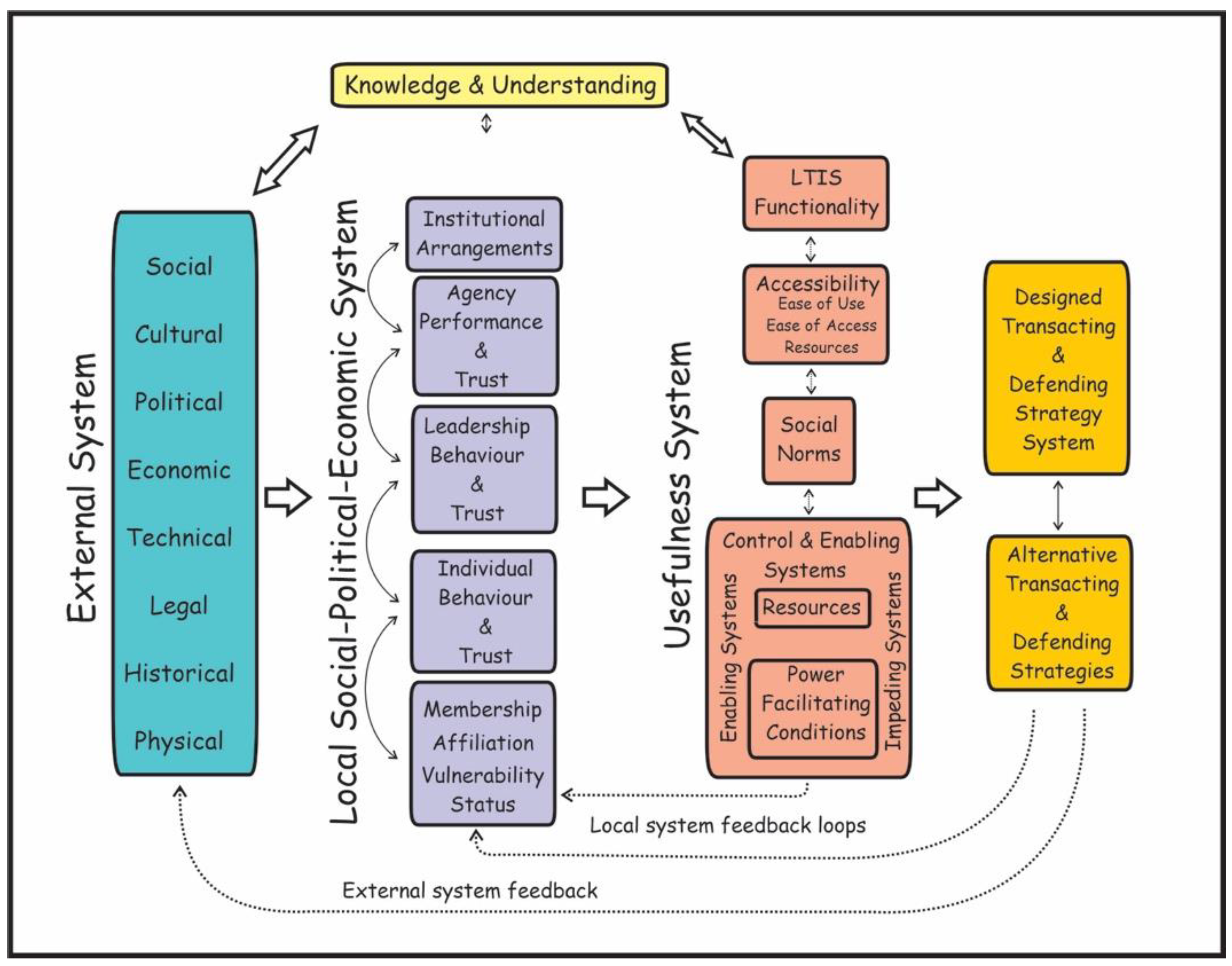

3. Framework for Analysing Community Records

3.1. Usefulness System

3.2. Local Social-Political-Economic System

3.3. External System

3.4. Applying the Framework in Sensitive Tenure Situations

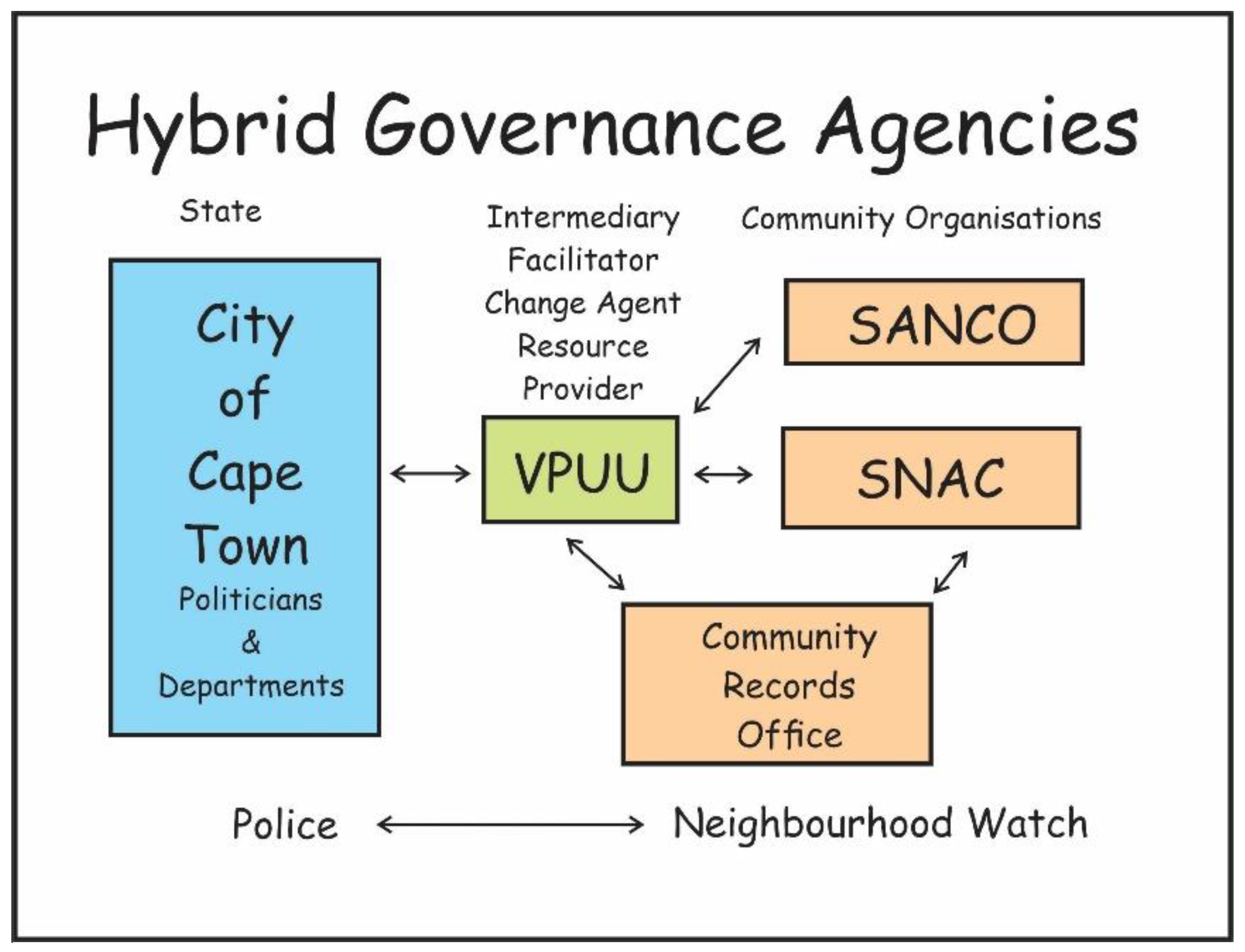

4. Hybrid Governance and Informal Settlements

4.1. Hybrid Governance and Informal Settlement Land Administration

4.2. Informal Settlement Upgrading

5. Organisational Culture and Community Records Development

6. Monwabisi Park

6.1. Development History, Institutions and Strategies

6.2. Tenure Governance Protocols

6.3. The Community Records System

7. Resident, SANCO, CRS and SNAC Interview Findings

7.1. Planning, Administration and Development

7.2. Crime and Personal Safety

7.3. Hybrid Land Governance Dynamics

7.4. Transaction Strategy: Acquiring a Shack

7.5. Defending Tenure and Knowledge and Usefulness of CRS

8. Discussion

8.1. External System

8.2. Local Social-Political-Economic System

8.3. Hybrid Governance

8.4. Organisational Culture and CRS Development Strategy

8.5. Usefulness System

8.6. Transacting and Defending Strategy System

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stats, S.A. Census Data: City of Cape Town Living Conditions. Available online: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=1021&id=city-of-cape-town-municipality (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Barry, M.; Roux, L. Land ownership and land registration suitability theory in state-subsidised housing in a rural South African town. Habitat Int. 2016, 53, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M. Evaluating Cadastral Systems in Periods of Uncertainty: A Study of Cape Town’s Xhosa-speaking Communities. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Natal, Durban, South Africa, December 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, M. Applying the theory of planned behaviour to cadastral systems. Surv. Rev. 2005, 38, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M. Hybrid land tenure administration in Dunoon, South Africa. Land Use Policy 2020, 90, 104301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, K. Increasing Tenure Security in Informal Settlements in South Africa: Legal and Administrative Recognition in Monwabisi Park, Khayelitsha. In Proceedings of the Urban LandMark Annual Conference: Investing in land and strengthening property rights, Johannesburg, South Africa, 12–13 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- VPUU. Violence Prevention through Urban Upgrading: A Manual for Safety as a Public Good. Available online: http://vpuu.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/VPUU_a-manual-for-safety-as-a-public-good.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- United Nations. Pretoria Declaration: Outcome Document of the Habitat III Thematic Meeting on Informal Settlements; Pretoria, South Africa, 7–8 April 2016. 2016. Available online: http://habitat3.org/wp-content/uploads/Pretoria-Declaration.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Western Cape Government. Municipal Economic Review and Outlook, Western Cape Government Provincial Treasury: 7 Wale Street, Cape Town, SA, USA, 2018. p. 534. Available online: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/assets/departments/treasury/Documents/Research-and-Report/2018/2018_mero_revised.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Barry, M.; Roux, L. Hybrid Governance and Land Purchase strategies in a state-subsidised housing project in a rural South African town. Surv. Rev. 2018, 51, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat/GLTN. Handling Land: Innovative Tools for Land Governance and Secure Tenure; United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat)/Global Land Tools Network (GLTN): Nairobi, Kenya, 2012; p. 170. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/handling-land-innovative-tools-for-land-governance-and-secure-tenure (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- UN-SDGs. Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Statistics Division-Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) of the United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security. 2012. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i2801e/i2801e.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). Governance of Tenure Technical Guides, 9 and 10. 2017. Available online: http://www.fao.org/tenure/resources/collections/governanceoftenuretechnicalguides/en/ (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Lengoiboni, M.; Richter, C.; Zevenbergen, J. Cross-cutting challenges to innovation in land tenure documentation. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, M. Notes Learning from Experience–Dunoon and Westlake. In Proceedings of the Workshop Connecting Research and Policy on Housing and Infrastructure in South African Cities, Cape Town, South Africa, 19–20 July 2017, (unpublished). [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and user acceptance in information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furneaux, B.; Wade, M. Theoretical constructs and relationships in information systems research. In Handbook of Research on Contemporary Theoretical Models in Information Systems; Dwivedi, Y.K., Lal, B., Williams, M.D., Schneberger, S.L., Wade, M., Eds.; Information Science Reference: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, L.; Barry, M. Land Rights in the Township: Building Incremental Tenure in Cape Town, South. Africa, 2009–2016; Innovations for Successful Societies; Trustees of Princeton University: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2017; Available online: https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/sites/successfulsocieties/files/LS_Land_SouthAfrica_May2017_1.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Royston, L.; Kingwill, R. Report of the VPUU Learning Workshop, Cape Town, 25–26 June 2015. (Unpublished VPUU internal document).

- Hood, J.C. Orthodoxy vs. Power: Defining the traits of grounded theory. The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory; Bryant, A., Charmaz, K., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2007; pp. 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, M.; Asiedu, K. Visualising changing tenure relationships: The talking titler methodology, data mining and social network analysis. Surv Rev. 2016, 49, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfouz, A. Contemporary information systems alternative models to tam: A theoretical perspective. In Handbook of Research on Contemporary Theoretical Models in Information Systems; Dwivedi, Y.K., Lal, B., Williams, M.D., Schneberger, S.L., Wade, M., Eds.; Information Science Reference: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 229–241. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, J. The technology acceptance model and other user acceptance theories. In Handbook of Research on Contemporary Theoretical Models in Information Systems; Dwivedi, Y.K., Lal, B., Williams, M.D., Schneberger, S.L., Wade, M., Eds.; Information Science Reference: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 277–294. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 538. [Google Scholar]

- Kingwill, R. The Map is not the Territory: Law and Custom in African Freehold: A South African Case Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS), University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa, December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Boege, V.; Brown, A.; Clements, K.; Nolan, A. On Hybrid. Political Orders and Emerging States: State Formation in the Context of “Fragility”; Berghof Research Center for Constructive Conflict Management: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, C. Rule and rupture: State formation through the production of property and citizenship. Dev. Chang. 2016, 47, 1199–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renders, M.; Terlinden, U. Negotiating statehood in a hybrid political order: The case of Somaliland. Dev. Chang. 2010, 41, 723–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.S. Hybridization and urban governance: Malleability, modality, or mind-set? Urban. Aff. Rev. 2017, 53, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meagher, K.; De Herdt, T.; Titeca, K. Unravelling Public Authority: Paths of Hybrid Governance in Africa; IS Academy on Human Security in Fragile States, Research Brief 10; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2014; Available online: http://urbanlandmark.org.za/downloads/Land_Biographies_Full_Report_LowRes.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Hagmann, T.; Péclard, D. Negotiating statehood: Dynamics of power and domination in Africa. Dev. Chang. 2010, 41, 539–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benda-Beckmann, F.V.; Benda-Beckmann, K.V.; Wiber, M.G. The Properties of Property. In Changing Properties of Property, 1st ed.; Benda-Beckmann, F.V., Benda-Beckmann, K.V., Wiber, M.G., Eds.; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, C.; Rubin, M. ‘Divisible Spaces’: Land Biographies in Diepkloof, Thokoza and Doornfontein, Gauteng. Urban LandMark. Report. 2008. Available online: http://urbanlandmark.org.za/downloads/Land_Biographies_Full_Report_LowRes.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Roux, L.M. Land Registration Use: Sales in a State-subsidised Housing Estate in South Africa. UCGE Report 20372. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, January 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Menski, W. Comparative Law in a Global context, The Legal Systems of Africa and Asia, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; p. 659. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, M.; Danso, E. Tenure Security, Land registration and customary tenure in Peri-urban Accra: A Case Study. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Luthango, M.; Reyes, E.; Gubevu, M. Informal settlement upgrading and safety: Experiences from Cape Town, South Africa. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2016, 32, 471–493. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Doing institutional analysis: Digging deeper than markets and hierarchies. In Handbook of New Institutional Economics. Menard, C., Shirley, M.M., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg/Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 819–848. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; p. 345. [Google Scholar]

- Anciano, F.; Piper, L. Democracy Disconnected: Participation and Governance in a City of the South; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. 262. [Google Scholar]

- Postman, Z. Court Interdicts Ekurhuleni from Reblocking Informal Settlement, GoundUp. Available online: https://www.groundup.org.za/article/court-interdicts-ekurhuleni-reblocking-informal-settlement/ (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Huchzermeyer, M. Unlawful Occupation: Informal Settlements and Urban. Policy in South. Africa and Brazil; Africa World Press: Trenton, NJ, USA, 2004; p. 274. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Quick Guide 2: Low-Income Housing Approaches to Helping the Urban. Poor Find. Adequate Housing in African Cities; United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat): Nairobi, Kenya, 2011; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Royston, L. Incrementally Securing Tenure: Promising Practices in Informal Settlement Upgrading in Southern Africa. In Proceedings of the World Bank 2014 Land and Poverty Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 24–27 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ciriola, L.R.; Görgens, T.; van Donk, M.; Smit, W.; Drimie, S. Upgrading informal settlements in South Africa. In Upgrading Informal in South Africa: A Partnership-Based Approach, 1st ed.; Ciriola, L.R., Görgens, T., van Donk, M., Smit, W., Drimie, S., Eds.; University of Cape Town Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2016; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Smit, W. Informal settlement upgrading: International lessons and local challenges. In Upgrading Informal in South Africa: A Partnership-Based Approach, 1st ed.; Ciriola, L.R., Görgens, T., van Donk, M., Smit, W., Drimie, S., Eds.; University of Cape Town Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2016; pp. 26–48. [Google Scholar]

- Western Cape Government. Informal Settlement Support Programme (ISSP) 2016 for the Western Cape. 2016. Available online: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/general-publication/informal-settlement-support-programme-issp-2016-western-cape?toc_page=1 (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Huchzermeyer, M. The struggle for in situ upgrading of informal settlements: A reflection on cases in Gauteng. Dev. South. Afr. 2009, 26, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, G. Recognising tenure and settlement rights of the poor: The City of Johannesburg’s programme to regularise informal settlements. In Untitled: Securing Land Tenure in Urban and Rural South Africa, 1st ed.; Hornby, D., Kingwill, R., Royston, L., Cousins, B., Eds.; University of KwaZulu-Natal Press: Durban, South Africa, 2017; pp. 361–387. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, H.; Lampel, J.; Quinn, J.B.; Goshal, S. The Strategy Process, Concepts, Contexts, Cases, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003; p. 489. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, C. Information Systems Strategic Management: An Integrated Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, T.; Marshall, T.E. Corporate culture, related chief executive officer traits, and the development of executive information systems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 1996, 12, 449–464. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.M. Information systems planning—Principles and practice. South. Afr. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 1985, 53, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Muhsen, A.R.; Barry, M.B. Technical challenges in developing flexible land records software. Surv. Land Inf. Sci. 2008, 68, 171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Gemey Abrahams Consultants. Incrementally securing tenure in Cape Town: Informal Settlement Transformation Programme pilot project in Monwabisi Park, Technical Report, Urban LandMark. 2013. Available online: http://www.urbanlandmark.org.za/downloads/tsfsap_tr_05.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Arnstein, S.R.A. Ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 5, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worcester Polytechnic Institute-Cape Town Project Center. Community Mobilisation through Reblocking: An Interactive Upgrading Anthology. 2013. Available online: https://wp.wpi.edu/capetown/projects/p2013/community-mobilisation-through-reblocking-in-flamingo-crescent/reblocking-a-mobilisation-anthology/ (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- VPUU. Monwabisi Park In-situ Upgrade Baseline Survey. September 2009; (Unpublished VPUU internal document). [Google Scholar]

- Department of Community Safety-Western Cape Government. Western Cape Provincial Constitution and Code of Conduct for Neighbourhood Watch Structures. 1999; p. 31. Available online: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/sites/www.westerncape.gov.za/files/documents/2004/1/1999_draft_code_conduct_nieghbourhood_watch.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Royston, L. ‘Entanglement’: A case study of changing tenure and social relations in inner-city buildings in Johannesburg. In Untitled: Securing Land Tenure in Urban and Rural South Africa; Hornby, D., Kingwill, R., Royston, L., Cousins, B., Eds.; University of KwaZulu-Natal Press: Durban, South Africa, 2017; pp. 196–234. [Google Scholar]

- Berens, C. VPUU Community Register Database Description. 2016; (Unpublished VPUU internal document). [Google Scholar]

- West Cape News. SANCO stole our money, say residents, West Cape News. 28 March 2011. Available online: https://westcapenews.com/?p=2866 (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Nombulelo, D.H. Monwabisi Park Residents Lay Charges against City Law Enforcement, GoundUp. 2015. Available online: https://www.groundup.org.za/article/monwabisi-park-residents-lay-charge-against-city-law-enforcement_3221/ (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Gontsana, M.A. Khayeltisha Residents Accuse City Officials of Corruption, GroundUp. Available online: https://www.groundup.org.za/article/khayelitsha-residents-accuse-city-officials-corruption/ (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Barry, M.; Whittal, J. Land title theory and land registration in a Mbekweni RDP housing project. Land Use Policy 2016, 56, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | ISO 19152:2012 covers basic components of land administration and provides an abstract, conceptual model with four packages related to parties (people and organizations); basic administrative units, rights, responsibilities, and restrictions (ownership rights); spatial units (parcels, and the legal space of buildings and utility networks); spatial sources (surveying), and spatial representations (geometry and topology). ISO creates documents that provide requirements, specifications, guidelines or characteristics that can be used consistently to ensure that materials, products, processes and services are fit for their purpose. ISOs can be purchased from the ISO Store or its members including the South African Bureau of Standards (SABS). |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barry, M.; Kingwill, R. Evaluating the Community Land Record System in Monwabisi Park Informal Settlement in the Context of Hybrid Governance and Organisational Culture. Land 2020, 9, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9040124

Barry M, Kingwill R. Evaluating the Community Land Record System in Monwabisi Park Informal Settlement in the Context of Hybrid Governance and Organisational Culture. Land. 2020; 9(4):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9040124

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarry, Michael, and Rosalie Kingwill. 2020. "Evaluating the Community Land Record System in Monwabisi Park Informal Settlement in the Context of Hybrid Governance and Organisational Culture" Land 9, no. 4: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9040124

APA StyleBarry, M., & Kingwill, R. (2020). Evaluating the Community Land Record System in Monwabisi Park Informal Settlement in the Context of Hybrid Governance and Organisational Culture. Land, 9(4), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9040124