Study of Heathland Succession, Prescribed Burning, and Future Perspectives at Kringsjå, Norway

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Haugesund, Karmøy, Steinsfjellet, and Kringsjå

2.1. Haugesund Region and Steinsfjellet Mountain Summit

2.2. Kringsjå Mountain Cabin

2.3. Kringsjå Sheep Farm

2.4. Activities at the Kringsjå Cabin and Sheep Farm

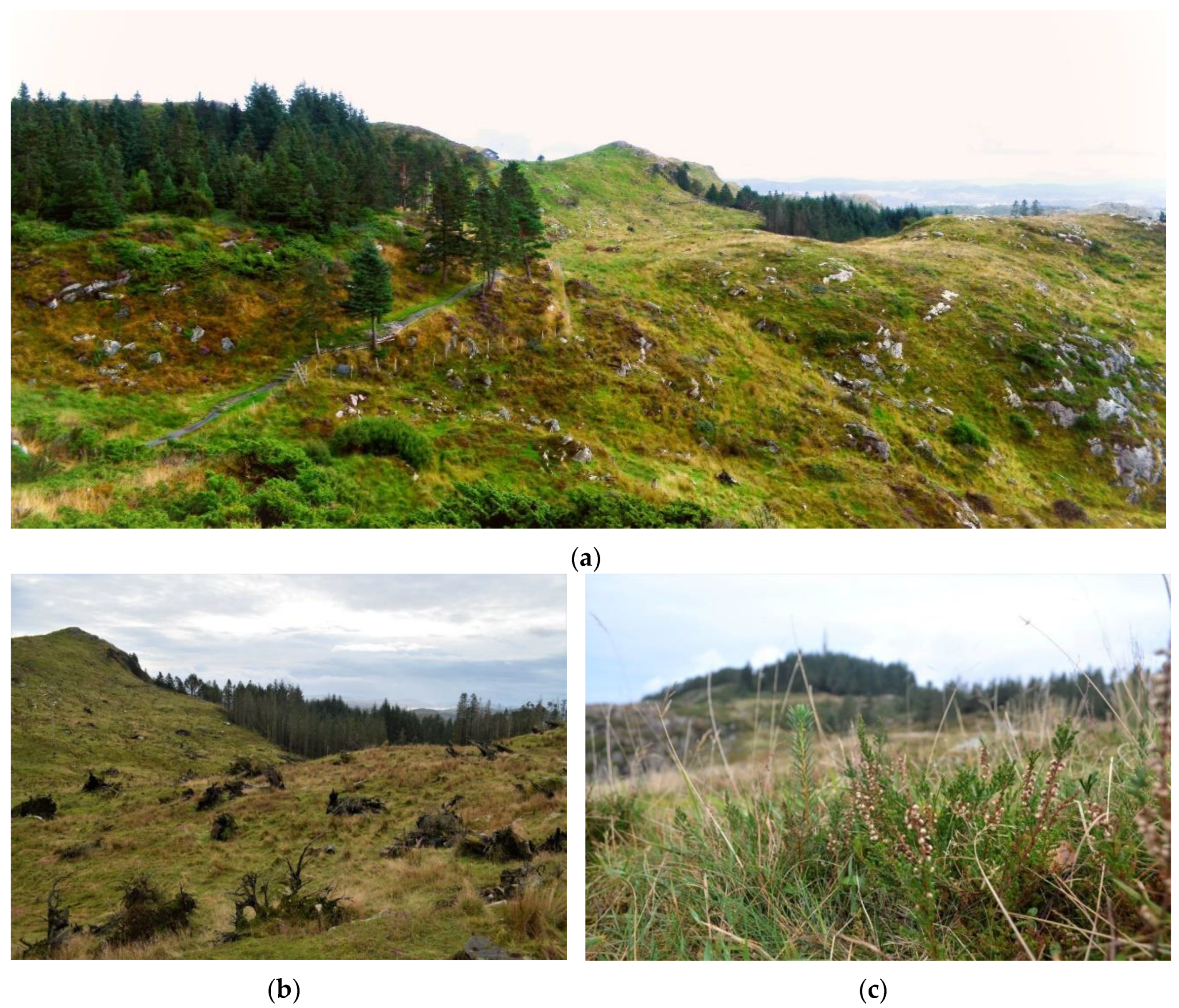

3. Successional Development at Steinsfjellet

3.1. The Calluna Dominated Heathland Maintenance Cycle

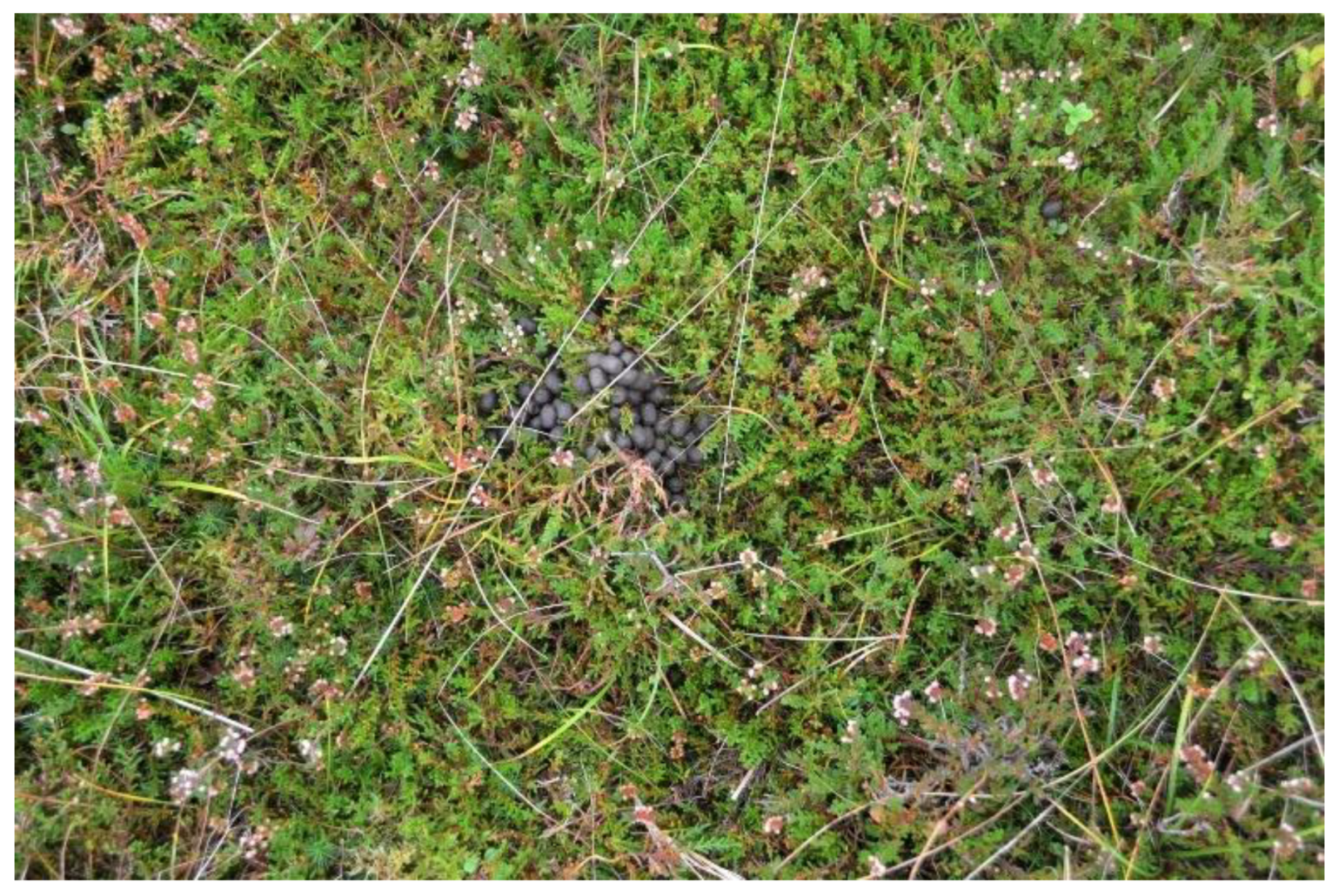

3.2. The Current Vegetation at Steinsfjellet

3.3. Successional Development in Unmanaged Versus Managed Areas at Steinsfjellet

3.4. Ancient Heathland Habitat Reclaiming Process

3.5. Prescribed Burning

4. Stimulating Synergies between Tourism and Landscape

4.1. Understanding the Historical Institutional Context of the Region

4.2. Strive for Integrated Policy Aimed at Synergetic Interactions

4.3. Gain an Overview of All Stakeholders

4.4. Include All Stakeholders

4.5. Develop a Shared Story

4.6. Co-Create a Vision for the Future

4.7. Allow for Flexibility in the Local Implementation

4.8. Dare to Experiment

4.9. Takeaways

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Commercial path dependency (single focus on economic revenue, discrete role of government, strong commercial actors, segmented politics, and paternalistic decision making)

- Limited regional focus on tourism (regional underdeveloped infrastructure, culture, nature-based tourism)

- Entertainment tourism might negatively affect tourist attractions’ dignity (and might harm the environment)

- Viking tourism might exclude culturally diverse group sense of belonging because of historical emphasis on Scandinavian ethnicity.

- External changes (such as decreasing number of tourists due to pandemic)

- Increased global, national, and local support towards SDGs and circular economy and increased attention to synergetic initiatives (e.g., between tourism and landscape).

- The Norwegian society is trending towards participation and activity-based local environmental protection, culture, and identity.

- Tourism (help stakeholders organise and present their regional heritage).

- Regional Viking tourism (remind today’s society about ecological caretaking, historic international orientation, trade, cultural exchange).

- Slow tourism to provide people the opportunity to “connect” with nature and learn about local history.

- Government involvement: Might delay and complicate activities (due to regulations, stalemate decision-making, and bureaucracy).

- Lack of government involvement might limit opportunities (in terms of awareness, acceptance, and support); e.g., relatively small funds provided by the government to contribute to areas of quality Calluna heathlands.

- Limiting infrastructure: Traffic, and toilet facility.

- Monetary costs associated with maintaining paths, mountain cabin, sheep farm, and Calluna heathland.

- Complexities of co-creation (potential conflict; side-tracking; multiplicity of objectives; competition; efficiency/success rate unknown (unforeseen); land ownership; dependability on others etc.).

- Economic viability of experiment-based activity (uncertainty of economic sustainability).

- Contribute to regional objectives (Circular economy and “city viable, sustainable, and lively to attract citizens and commerce”).

- Nature-based tourism: Attract tourists because of the beautiful vicinity, and husbandry (Wild Norwegian Sheep).

- Expertise in Calluna heathland maintenance (collaboration with local prescribed burner groups might foster further experimentation and a dynamic site for environmental tourism).

- Learning points from other successful tourist initiatives (such as Avaldsnes, HCL, village tourism in Hordaland, and MHC in Italy).

- Previous experience with tourism (specific learning points: The tourist enjoyed learning about the local Viking history, fed the (Viking) sheep, and experienced the beautiful view).

- Socio-environmental objectives (aiming to provide benefits to the society).

- Inclusive approach (across social groups, ages, and cultures).

- Broad Stakeholder involvement (collaborate with volunteers; social service; WUI researchers; prescribe burners; academia) (impact: coverage, awareness building, popular opinion, monetary contribution, practical and knowledge expertise, on-site development, network-building).

- Continues network building with local government, tourist officials, media and environmental intuitions that have visited Kringsjå the past months to learn about the ongoing activities.

- Agile approach: Innovative and experimentational (e.g., pilot research fields demonstrating local successional development. Provided as educational value for local schools).

- Implementation of a Kringsjå Living Lab. A living lab might shape a dynamic storyline that facilitates activities that provide “learning value” to society; potentially taking care of and convoying information about heathland restoration. Co-creating a Living Lab might enable small-scale developments paving pathways to synergetic interactions (facilitate participatory action, enabling an open dialogue, overcoming misunderstandings/disagreement, shared objectives, outlining direction of activity).

References

- Jurdao, S.; Chuvieco, E.; Arevalillo, J.M. Modelling Fire Ignition Probability from Satellite Estimates of Live Fuel Moisture Content. Fire Ecol. 2012, 8, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento-Gonçalves, A.; Vieira, A. Wildfires in the wildland-urban interface: Key concepts and evaluation methodologies. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 707, 135529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, A.; Pallares-Barbera, M.; Valldeperas, N.; Gisbert, M. Wildfires in the wildland-urban interface in Catalonia: Vulnerability analysis based on land use and land cover change. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 673, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palaiologou, P.; Kalabokidis, K.; Ager, A.A.; Day, M.A. Development of Comprehensive Fuel Management Strategies for Reducing Wildfire Risk in Greece. Forests 2020, 11, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowery, M.; Read, M.; Johnston, K.; Wafaie, T. Planning the Wildland-Urban Interface; Report 594, Planning Advisory Service; American Planning Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-61190-202-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rego, F.M.C.C.; Rodríguez, J.M.M.; Calzada, V.R.V.; Xanthopoulos, G. Forest Fires—Sparking Firesmart Policies in the EU; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; p. 53. ISBN 978-92-79-77493-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddet Fra flammene—Det Var Et skikkelig Inferno (Rescued from the Flames—It Was a Real Inferno). Available online: https://www.vg.no/nyheter/innenriks/i/vQldqV/reddet-fra-flammene-det-var-et-skikkelig-inferno (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- How Climate Change is Causing ‘Mega-Fires’ and Forcing People to Migrate in Portugal. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/2020/06/17/how-climate-change-is-causing-mega-fires-and-forcing-people-to-migrate-in-portugal (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Log, T.; Vandvik, V.; Velle, L.G.; Metallinou, M.-M. Reducing Wooden Structure and Wildland-Urban Interface Fire Disaster Risk through Dynamic Risk Assessment and Management. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2020, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Metallinou, M.-M. Emergence of and Learning Processes in a Civic Group Resuming Prescribed Burning in Norway. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesio, L. Can fire avoid massive and rapid habitat change in Italian heathlands? J. Nat. Conserv. 2014, 22, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, M.J.; De Luís, M.; Raventós, J.; Escarré, A. Factors influencing fire behavior in shrublands of different stand ages and the implications for using prescribed burning to reduce wildfire risk. J. Environ. Manag. 2002, 65, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaland, P.E. The origin and management of Norwegian coastal heaths as reflected by pollen analysis. In Anthropogenic Indicators in Pollen Diagrams; Behre, K.E., Ed.; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1986; pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prøsch-Danielsen, L.; Simonsen, A. Palaeoecological investigations towards the reconstruction of the history of forest clearances and coastal heathlands in southwestern Norway. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2000, 9, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimingham, C.H. Ecology of Heathlands; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1972; ISBN 10: 0412104601. [Google Scholar]

- Gimingham, C.H. Biological flora of the British Isles: Calluna vulgaris (L) hull. J. Ecol. 1960, 48, 455–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandvik, V.; Töpper, J.P.; Cook, Z.; Daws, M.I.; Heegaard, E.; Måren, I.E.; Velle, L.G. Management-driven evolution in a domesticated ecosystem. Biol. Lett. 2014, 10, 20131082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Log, T.; Thuestad, G.; Velle, L.G.; Khattri, S.K.; Kleppe, G. Unmanaged heathland—A fire risk in subzero temperatures? Fire Saf. J. 2017, 90, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljostatus Kystlynghei (The Environmental Condition of Calluna Heathlands). Available online: https://miljostatus.miljodirektoratet.no/kystlyngheiKaland (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Kaland, P.-E.; Kvamme, M. Kystsyngheiene i Norge–Kunnskapsstatus og Beskrivelse av 23 Referanseområder (The Coastal Calluna Heathlands in Norway—Knowledge Status and Description of 23 Areas of Reference); Miljødirektoratet: Oslo, Norway, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hauglin, M.; Ørka, H.O. Discriminating between Native Norway Spruce and Invasive Sitka Spruce—A Comparison of Multitemporal Landsat 8 Imagery, Aerial Images and Airborne Laser Scanner Data. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nygaard, P.H.; Øyen, B.-H. Spread of the Introduced Sitka Spruce (Picea sitchensis) in Coastal Norway. Forests 2017, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Velle, L.G.; Nilsen, L.S.; Vandvik, V. The age of Calluna stands moderates post-fire regeneration rate and trends in northern Calluna heathlands. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2012, 15, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Log, T. Modeling Drying of Degenerated Calluna vulgaris for Wildfire and Prescribed Burning Risk Assessment. Forests 2020, 11, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DSB. Brannene i Lærdal, Flatanger og på Frøya Vinteren 2014 (The Fires in Lærdal, Flatanger and on Frøya Winter 2014); Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection: Tønsberg, Norway, 2014; ISBN 978-82-7768-342-3.

- Lindgaard, A.; Henriksen, S. Norsk Rødliste for Naturtyper 2011(Norwegian Red List of Habitats 2011); Artsdatabanken: Trondheim, Norway, 2011; ISBN 13: 978-82-92838-29-7. [Google Scholar]

- Myr (Marsh). Available online: https://www.sabima.no/trua-natur/myr/ (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Harstad, B.; Harestad, A.; Fludal, A. Beitetrykk i Lynghei;—Produksjon av Kjøtt—Produksjon av Landskap (Grazing Pressure in Heathlands;—Production of Meat—Production of Landscape); Norsk landbruksrådgiving Rogaland: Haugesund, Norway, 2014; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Gammelnorsk Sau (Old Norwegian Sheep). Available online: www.nibio.no/tema/mat/husdyrgenetiske-ressurser/bevaringsverdige-husdyrraser/sau/gammelnorsk-sau (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- Boustras, G.; Boukas, N. Forest fires’ impact on tourism development: A comparative study of Greece and Cyprus. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2013, 24, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Værlandet. Meet the Old Norse Sheep. Available online: www.hurtigruten.co.uk/excursions/norway/varlandet-meet-the-old-norse-sheep/ (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Ruud, T. See Haugalandet, Final Report; Haugaland Landbruksrådgjeving: Ølen, Norway, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D.B.A.; MacDonald, A.J.; Marsden, J.H.; Galbraith, C.A. Upland heather moorland in Great Britain: A review of international importance, vegetation change and some objectives for nature conservation. Biol. Conserv. 1995, 71, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppock, J.T. Tourism and conservation. Tour. Manag. 1982, 3, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslinga, J.; Groote, P.; Vanclay, F. Towards Resilient Regions: Policy Recommendations for Stimulating Synergy between Tourism and Landscape. Land 2020, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yapeng, O.U. Emerging Civic Engagement in the Revitalization of Minor Historic Centers, Cases from Reggio Calabria, Italy. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS 19th General Assembly and Scientific Symposium “Heritage and Democracy”, New Delhi, India, 13–14 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Goeldner, C.R.; Ritchie, B.J.R. Tourism: Principles, Practices, Philosophies, 11th ed.; Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, J.C. The Business of Tourism, 8th ed.; Prentice Hall: Essex, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-52645-944-2. [Google Scholar]

- Forskrift om vern av Villsau frå Norskekysten/Villsau fra Norskekysten Som Geografisk Nemning (Regulation on the Protection of Villsau from the Norwegian Coast/Villsau from the Norwegian Coast as a Geographical Naming); The Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food: Oslo, Norway, 2010. Available online: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2010-11-04-1402 (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- Guttormsen, T.S. Branding local heritage and popularising a remote past: The example of Haugesund in Western Norway. AP Online J. Public Archaeol. 2017, 4, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, A. Kulturlandskap og biologisk mangfald på Haugalandet (The Cultural landscape and biodiversitet at Haugalandet). Fylkesmannen i Rogaland Miljørapport 2010, 5, 212. [Google Scholar]

- Haugesund—Tettstedet (Haugesund—Town Area). Available online: https://snl.no/Haugesund_-_tettstedet (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Næringsliv (Commerce). Available online: https://haugalandvekst.no/tema/naeringsliv/ (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Landbruk og mat (Agriculture and Food). Available online: https://www.fylkesmannen.no/Rogaland/Landbruk-og-mat/ (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Haugesund Klima (Haugesund Climate). Available online: https://no.climate-data.org/europa/norge/rogaland/haugesund-6831/ (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Haugesund Cruise Port. Available online: https://karmsundhavn.no/forretningsomrader/haugesund-cruise-port/ (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Lie, R.W. Ældste Nordmand (Oldest Norwegian); Skalks Gæstebog; Wormanium: Oslo, Norway, 1985; pp. 47–50. ISBN 87-8516-088-1. [Google Scholar]

- Farrar, A.; Kendal, D.; Williams, K.J.H.; Zeeman, B.J. Social and Ecological Dimensions of Urban Conservation Grasslands and Their Management through Prescribed Burning and Woody Vegetation Removal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avaldsnes Norges Eldste Kongsete (Avaldsnes, the Oldest Kingdom of Norway). Available online: https://avaldsnes.info/ (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Norges Riksmonument (the Norwegian National Monument). Available online: https://www.visithaugesund.no/opplevelser/norges-riksmonument-p794713 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Steinsfjellet—tur Med Panoramautsikt (Steinsfjellet—A Hike with Panoramic Views). Available online: https://www.visithaugesund.no/opplevelser/steinsfjellet-tur-med-panoramautsikt-p1575913 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Kringsjå—Et Møtested for Store og Små (Kringsjå—A Meeting Place for Young and Old). Available online: http://www.kringsjaa.net/ (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Økologisk Drift (Organic Farming). Available online: http://www.kringsjaa.net/index.php/okologisk-drift (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Lillesund, V.F.; Hansen, R.V.; Kvalevåg, M.M.; Vold, E.M.; Husby, V.; Bråten, K.G.; Opsahl, J.; Økstad, E. Utfasing av uttak og bruk av torv—Kunnskapsutredning om Konsekvenser for Naturmangfold, Klima, Næring og Forbrukere (Phasing Out Extraction and Use of Peat—Knowledge Study on Consequences for Biodiversity, Climate, Industry and Consumers); Report M-951; Norwegian Environment Agency: Trondheim, Norway, 2018.

- Webb, N.R. The traditional management of European heathlands. J. Appl. Ecol. 1998, 35, 987–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velle, L.G.; Vandvik, V. Succession after prescribed burning in coastal Calluna heathlands along a 340-km latitudinal gradient. J. Veg. Sci. 2014, 25, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, L.S.; Johansen, L.; Velle, L.G. Early stages of Calluna vulgaris regeneration after burning of coastal heath in central Norway. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2005, 8, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimingham, C.H. The Lowland Heathland Management Handbook; English Nature: Peterborough, UK, 1992; ISBN 1 85716 0770. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, M.H. An exceptional Calluna vulgaris winter die-back event, Abernethy Forest, Scottish Highlands. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2008, 1, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.A.; Denelle, P.; Sánchez Ruiz, F.M.; Santana, V.M.; Marrs, R.H. Prescribed moorland burning meets good practice guidelines: A monitoring case study using aerial photography in the Peak District, UK. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 62, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davies, G.M.; Legg, J.J.; O’hara, R.; MacDonals, A.J.; Smith, A.A. Winter desiccation and rapid changes in the live fuel moisture content of Calluna vulgaris. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2010, 3, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, G.M.; Domènech, R.; Gray, A.; Johnson, P.C.D. Vegetation structure and fire weather influence variation in burn severity and fuel consumption during peatland wildfires. Biogeosciences 2016, 13, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saure, H.I.; Vandvik, V.; Hassel, K.; Vetaas, O.R. Effects of invasion by introduced versus native conifers on coastal heathland vegetation. J. Veg. Sci. 2013, 24, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øyen, B.H.; Nygaard, P.H. Impact of Sitka spruce on biodiversity in NW Europe with a special focus on Norway—Evidence, perceptions and regulations. Scand. J. For. Res. 2020, 35, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diotte, M.; Bergeron, Y. Fire and the distribution of Juniperus communis L. in the Boreal Forest of Quebec, Canada. J. Biogeogr. 1989, 16, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tør du/dere bli med opp og se I fjellet? (Do You Dare Join Me Up to Look at the Mountain?). Available online: https://www.h-avis.no/meninger/leserbrev/tor-du-dere-bli-med-opp-og-se-i-fjellet/s/2-2.921-1.8335443 (accessed on 14 July 2020).

- Davies, G.M.; Legg, C.J. Fuel moisture thresholds in flammability of Calluna vulgaris. Fire Technol. 2011, 47, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, G.M.; Legg, C.J.; Smith, A.A.; MacDonald, A.J. Rate of spread of fires in Calluna vulgaris-dominated moorlands. J. Appl. Ecol. 2009, 46, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spesielle Miljøtiltak i Jordbruket (SMIL). Available online: https://www.landbruksdirektoratet.no/no/miljo-og-okologisk/spesielle-miljotiltak/om-tilskudd-til-spesielle-miljotiltak-i-jordbruket (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Rusten, G.; Iversen, N.M.; Hem, L.E. Våronn Med Nye Muligheter: Ressurs-og Opplevelsesbasert Verdiskaping på Vestlandsbygdene (Agricultural Spring Preparations with New Opportunities: Resource- and Experience-Based Value Creation in the Western Countryside); Fagbokforlaget Vigmostad & Bjørke AS: Bergen, Norway, 2007; ISBN 978-82-450-0624-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bonadonna, A.; Rostagno, A.; Beltramo, R. Improving the Landscape and Tourism in Marginal Areas: The Case of Land Consolidation Associations in the North-West of Italy. Land 2020, 9, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A. Emerging Patterns of Mountain Tourism in a Dynamic Landscape: Insights from Kamikochi Valley in Japan. Land 2020, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heslinga, J.H.; Groote, P.D.; Vanclay, F. Understanding the historical institutional context by using content analysis of local policy and planning documents: Assessing the interactions between tourism and landscape on the Island of Terschelling in the Wadden Sea Region. Tour Manag. 2018, 66, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tennøy, A.; Øksenholt, K.V.; Nore, N. Analyser av tre scenarier for arealutvikling i Haugesund (Analyzes of Three Scenarios for Area Development in Haugesund); Transportøkonomisk Institutt. Stiftelsen Norsk Senter for Samferdselsforskning: Oslo, Norway, 2014; Volume 1322. [Google Scholar]

- Kommuneplanens Samfunnsdel 2014–2030 (The Society Part of the Municipality Plan 2014–2030). Available online: https://www.haugesund.kommune.no/lokaldemokrati/kommunale-planer/kommuneplan (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Fuenfschilling, L.; Truffer, B. The structuration of socio-technical regimes—Conceptual foundations from institutional theory. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 772–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Circular Economy Action Plan. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/circular-economy/ (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Sandifer, P.A.; Sutton-Grier, A.E.; Ward, B.P. Exploring connections among nature, biodiversity, ecosystem services, and human health and well-being: Opportunities to enhance health and biodiversity conservation. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andresen, S.A. Contesting scale: A space of the political in a post-disaster context. Political Geogr. 2020, 81, 102203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslinga, J.H.; Groote, P.D.; Vanclay, F. Strengthening governance processes to improve benefit sharing from tourism in protected areas by using stakeholder analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 773–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eimhjellen, I.; Loga, J.M. Nye Samarbeidsrelasjoner Mellom Kommuner og Frivillige Aktører: Samskaping i nye Samarbeidsforhold? (New Collaborative Relationships between Municipalities and Voluntary Actors: Co-Creation in New Collaborative Relationships?); Center for Research on Civil Society and Volunteer Sector: Oslo, Norway, 2017; ISBN 978-82-7763- 578-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ødegård, G.; Loga, J.; Steen-Johnsen, K.; Ravneberg, B. Fellesskap og forskjellighet. Integrasjon og nettverksbygging i flerkulturelle lokalsamfunn (Community and Diversity. Integration and Networking in Local Neighborhoods); Abstrakt Forlag: Oslo, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Enjolras, B.; Strømsnes, K. Scandinavian Civil Society and Social Transformations: The Case of Norway—Nonprofit and Civil Society Studies; Dekker, P., Benjamin, L., Enjolras, B., Strømsnes, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 9783319772639. [Google Scholar]

- Gulbrandsen, T.; Ødegård, G. Frivillige Organizasjoner i En Ny Tid, Utfordringer og Endringsprosesser (Voluntary Organizations in a New Era, Challenges and Change Processes); Center for Research on Civil Society and Volunteer Sector: Oslo, Norway, 2011; p. 123. ISBN 978-82-7763-359-6. [Google Scholar]

- Arnesen, D.; Sivesind, K.H.; Gulbrandsen, T. Fra Medlemsbaserte Organisasjoner til Koordinert Frivillighet? Det Norske Organisasjonssamfunnet fra 1980 til 2013 (From Member-Based Organizations to Coordinated Volunteerism? The Norwegian Organizational Society from 1980 to 2013); Center for Research on Civil Society and Volunteer Sector: Oslo, Norway, 2016; p. 106. ISBN 978-82-7763-517-0. [Google Scholar]

- Arnesen, D.; Sivesind, K.H. Organisasjonslandskap i Endring 2009–2019, fra Ideololgisk Samfunnsendring til Individuell Utfoldelse? (Organizational Landscape in Change 2009–2019, from Ideological Change in Society to Individual Expression?); Institutt for samfunnsforskning: Oslo, Norway, 2020; p. 108. ISBN 978-82-7763-517-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ingstad, E.S.L.; Loga, J. Sosialt entreprenørskap i Norge: En introduksjon til feltet. (Social entrepreneurship in Norway: An introduction to the field). Praktisk Økonomi Finans 2016, 32, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youth and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/youth/world-youth-report/wyr2018.html (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Lyngheisenteret (the Calluna Heathland Centre). Available online: http://www.muho.no/lyngheisenteret (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Manniche, J.; Larsen, K.T.; Broegaard, R.B.; Holland, E. Destination: A Circular Tourism Economy A Handbook for Transitioning Toward a Circular Economy within the Tourism and Hospitality Sectors in the South Baltic Region; Centre for Regional & Tourism Research (CRT): Bornholm, Denmark, 2017; ISBN 9788793583047. [Google Scholar]

- Munkvold, B.E. Diffusing crisis management solutions through living labs: Opportunities and challenges. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, (ISCRAM), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 22–25 May 2016; ISBN 978-84-608-7984-8. [Google Scholar]

- Veeckman, C.; Schuurman, D.; Leminen, S.; Westerlund, M. Linking living lab characteristics and their outcomes: Towards a conceptual framework. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2013, 3, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedtke, C.; Welfens, M.J.; Rohn, H.; Nordmann, J. LIVING LAB: User-driven innovation for sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergvall-Kareborn, B.H.M.S.A.; Hoist, M.; Stahlbrost, A. Concept Design with a Living Lab Approach. In Proceedings of the 2009 42nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hakkarainen, L.; Hyysalo, S. How do we keep the living laboratory alive? Learning and conflicts in living lab collaboration. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, L.; Velle, L.G.; Wehn, S.; Hovstad, K.A. Kystlynghei i Naturindeks for Norge-Utvikling av indikatorer og datagrunnlag; NIBIO Report; NIBIO: Kvithamar, Norway, 2015; Volume 1, ISBN 978-82-17-01459-1.

- Green, S.; Elliot, M.; Armstrong, A.; Hendry, S.J. Phytophthora austrocedrae emerges as a serious threat to juniper (Juniperus communis) in Britain. Plant Pathol. 2015, 64, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menton, M.; Lerrea, C.; Latorre, S.; Martinez-Alier, J.; Peck, M.; Temper, L.; Walter, M. Environmental justice and the SDGs: From synergies to gaps and contradictions. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gjedrem, A.M. This is Our Light, We should Catch This One: A Story of Women Empowerment through Decentralized Solar Power in Jordan and in Tonga. Master’s Thesis, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Ås, Norway, May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, V.; Alderson, L.; Hall, S.; Sponenberg, D.P. Mason’s World Encyclopedia of Livestock Breeds and Breeding; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2016; p. 200. ISBN 978-1-84593-466-8. [Google Scholar]

- Meir om Kystlynghei Som Utvald Naturtype (More about Coastal Heathland as a Selected Habitat Type). Available online: https://www.fylkesmannen.no/Rogaland/Miljo-og-klima/Skjulte-tekstar/Meir-om-kystlynghei-som-utvald-naturtype/ (accessed on 27 October 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gjedrem, A.M.; Log, T. Study of Heathland Succession, Prescribed Burning, and Future Perspectives at Kringsjå, Norway. Land 2020, 9, 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120485

Gjedrem AM, Log T. Study of Heathland Succession, Prescribed Burning, and Future Perspectives at Kringsjå, Norway. Land. 2020; 9(12):485. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120485

Chicago/Turabian StyleGjedrem, Anna Marie, and Torgrim Log. 2020. "Study of Heathland Succession, Prescribed Burning, and Future Perspectives at Kringsjå, Norway" Land 9, no. 12: 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120485