Landscape—A Review with a European Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Concept of Landscape—Birth and Definition

2.1. Origin and Etymology of the Word “Landscape”

2.2. Selected Landscape Theories

“We like the landscape because we like nature, and the landscape is the portrait of it”.[24], F. Paulhan, 2016, p. 5

“Only when I saw the Earth from space, in all its ineffable beauty and fragility, I realized that the most urgent task for humanity is to take care of it and preserve it for future generations”.[42], S. Jahn, December 2007, National Geographic Magazine

2.3. Landscape Legislation and the Question of Identity

“In the flesh of the landscape all the stigmata of the past are impressed and endured. Landscape is a memory and I can interrogate it”.[63], M. Corajoud in B. Cillo, 2008, p. 87

3. Landscape Mutation—Abandonment and Residual Spaces

3.1. Changed Landscape

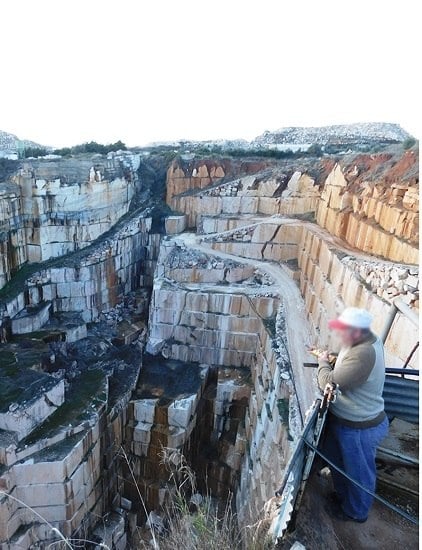

The Case of the Quarry

- Open air: type of quarry used to extract deposits of mineral resources near the surface.

- Underground: requires equipment or workers to operate under the surface of the earth.

- Pit: type of open pit typical for flat areas, where mining is carried out along graded surfaces that extend downwards to below the level of the countryside [75].

3.2. Landscapes of Abandonment

3.2.1. The Friche Concept

3.2.2. Wasteland and the Notion of Terrain Vague

3.2.3. Drosscape as a Refuse Space

- Wastelandscape of dwelling (LOD): refers to voids of land that are integrally designed into housing developments, especially into walled or gate enclaves. These voids often have singular programmatic intentions (golf course, buffer zone, preservation area, trail system, etc.). There are two types of LOD voids: those that are outside and inside the enclave. “Outside” voids encircle the enclave as buffers and separators from adjacent development or other possible nuisance land uses that may affect the quality of life held by the dwellers of the enclave. “Inside” voids are designed, for example, to allow for public utility easements that cross throughout enclave territory. They serve the social, circulation, and recreation needs of their inhabitants.

- Wastelandscape of transition (LOT): reveals the transitory nature of capital investment and real estate speculation. Some LOTs are intentionally designed and built as transitional land uses, such as staging areas, storage yards, parking surfaces, transfer stations, etc.

- Wastelandscape of infrastructure (LIN): includes the landscape surfaces that are associated with the infrastructure, including easements, setbacks, and rights-of-way associated with transportation (such as highway corridors and interchanges), electric transmission, oil and gas pipelines, waterways, and railways.

- Wastelandscape of obsolescence (LOO): refers to the sites that are designed for accommodating consumer wastes. These include municipal-solid waste landfills, wastewater-treatment facilities, and “cars dismantlers”.

- Wastelandscape of exchange (LEX): refers to shopping centers and all those urban complexes where the commercial, but also catering, fitness, and entertainment functions are concentrated. They are boxes that are surrounded by parking lots and can only be reached via expressways. They generate many interstices, waste spaces, and often they become places of waste when they become unsuccessful and lose their economic value.

4. Re-Designing the Dead Landscape

4.1. Recycle and Reutilization of the Waste Material

“Rebuilding instead of building: building on, around, inside, on, with waste materials; to live in ruins instead of building; re-naturalize rather than re-urbanize”.[120], P. Ciorra in S. Marini, V. Santangelo, 2013, p. 13

4.2. Rehabilitation Concept—A Bridge Between Past and Present

“The only thing introduction that we can ever know for certain about the world is that which exists now or has existed in the past. To make something new we must start with what is or has been and change it in some way to make it fresh. How to make old things new, how to see something common and banal in a new and fresh way is the central problem”.[131], L. Olin, 1998, p. 159

“When we live in a place, make a home in it, a permanent investment, we are said to inhabit it. A good place is one in which we feel comfortable, that fits us like a pair of worn jeans”.[138], T. Waterman, 2009, p. 6

4.3. The Promotion of Art and Landscape Architecture in the Abandonment Territory

“Today one can very easily imagine that a polluted place produces a beautiful landscape and that in the opposite a non-polluted place is not necessarily beautiful”.[141], B. Lassus, 1991, p. 64

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jakob, M. Il Paesaggio; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Raffestin, C. Du Paysage à l’espace Ou Les Signes de La Géographie. Hèrodote 1978, 9, 90–104. [Google Scholar]

- Fedeli, P. La Natura Violata: Ecologia e Mondo Romano; Sellerio: Palermo, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McHarg, I.L. Design with Nature; American Museum of Natural History: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, R. Sprawltown: Looking for the City on Its Edges; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, A. Drosscape: Wasting Land in Urban. America; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Duby, J.; Wallon, A. Histoire de La France Rurale; Le Seuil: Paris, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Augè, M. Non-Lieux: Introduction à Une Anthropologie de La Surmodernité; Le Seuil: Paris, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, O.; Lautensach, H. Geografia de Portugal; Edições João Sá da Costa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Veríssimo Serrão, A. Filosofia Da Paisagem, Uma Antologia, 2nd ed.; Centro de Filosofia Universidade de Lisboa: Lisbon, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

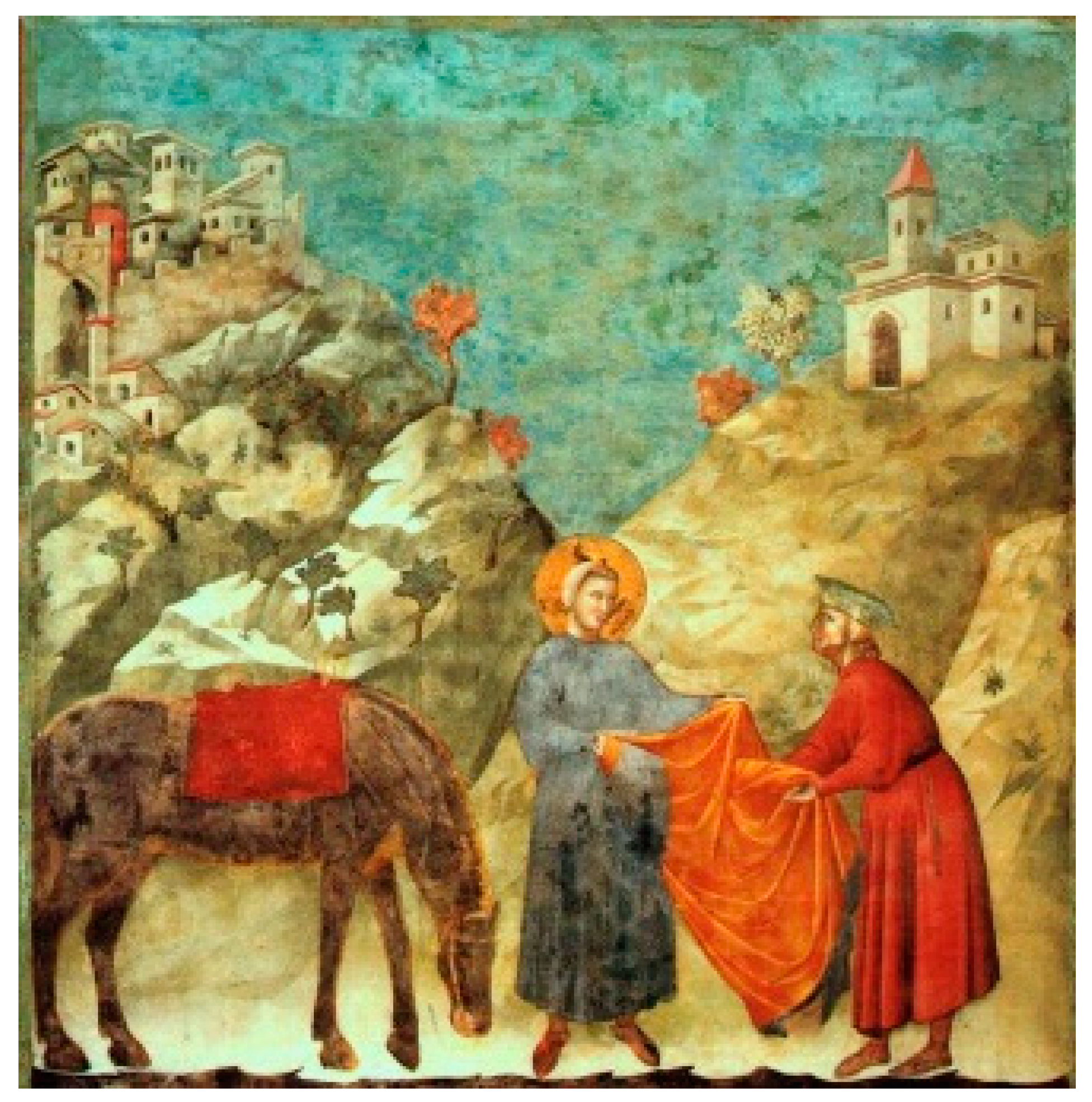

- Salvini, R. All the Paintings of Giotto; Hawthorn Books: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

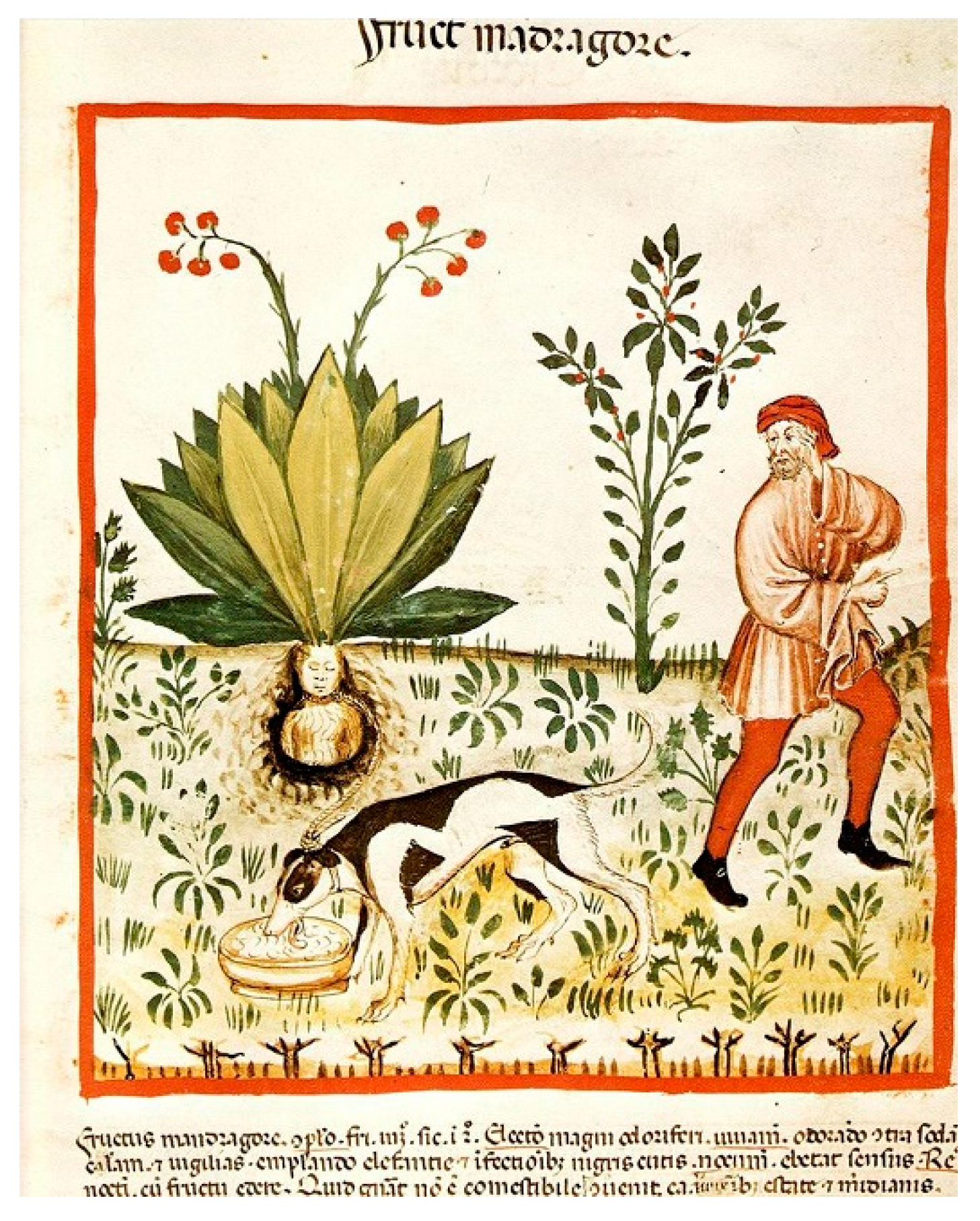

- Hanley, D. Tacuinum Sanitatis: Health and Well Being: A Primitive Medieval Guide; Cognoscenti Books: Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

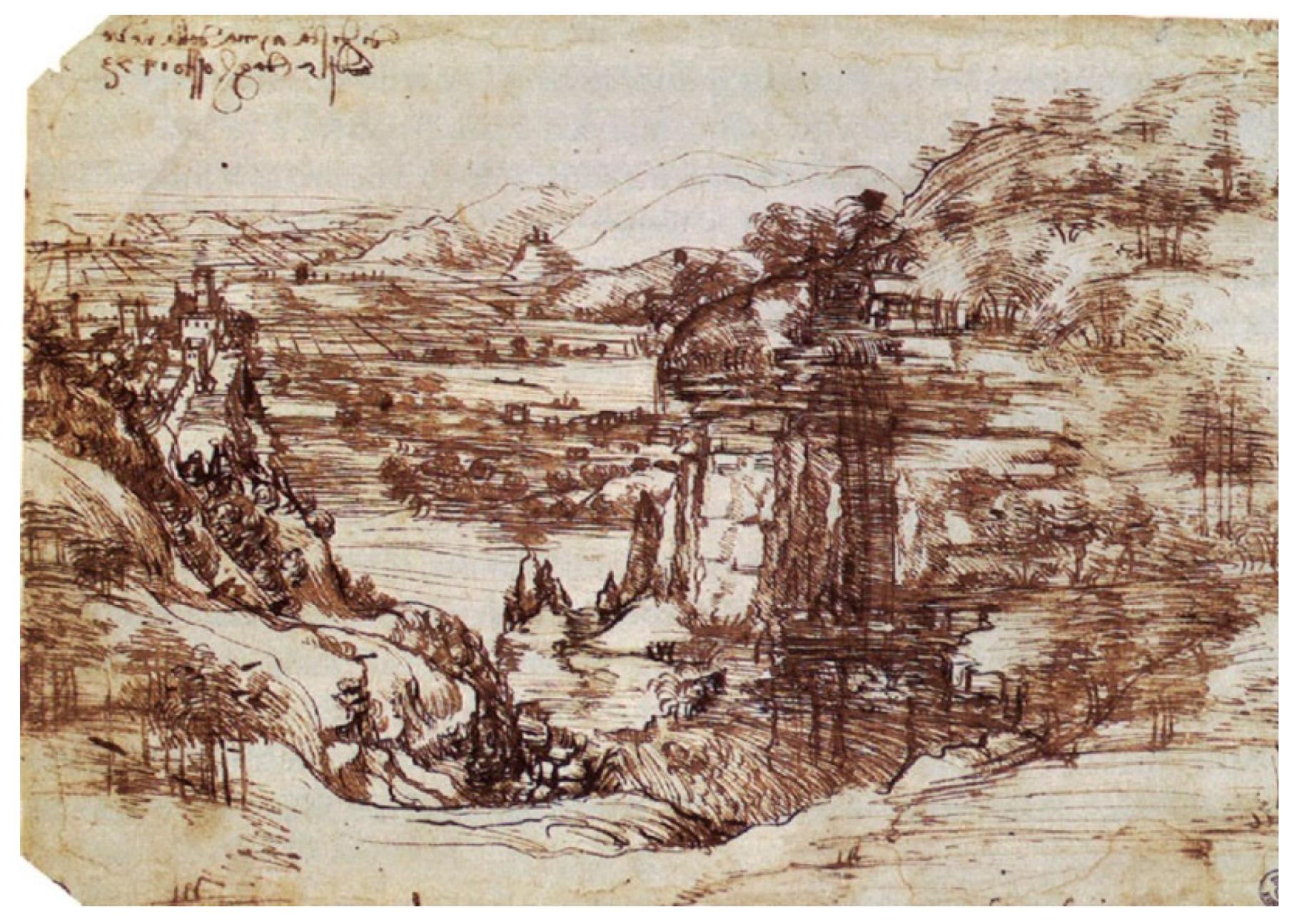

- Cricco, G.; Di Teodoro, F. Itinerario Nell’arte, 4th ed.; Zanichelli: Modena, Italy, 2017; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Jellicoe, G.; Jellicoe, S. The Landscape of Man; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto-Correia, T. Landscape Identity, a Key for Integration. In Landscape—Our Home; Indigo-Zeist: Stuttugart, Germany, 2000; pp. 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Tufnell, B. Land Art; Tate Gallery Pubn, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Weilacher, U. Between Landscape Architecture and Land Art; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland; Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Martinet, J. Le Paysage: Signifiant et Signifié. In Lire le Paysage, Lire les Paysages, Act du Colloque des 24 et 25 Novembre 1983; CIEREC: Saint-Etienne, France, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Luginbühl, Y. Rappresentazioni Sociali Del Paesaggio Ed Evoluzione Della Domanda Sociale. In Di Chi è il Paesaggio? CLEUP: Padova, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Luginbühl, Y. Paysage et Démocratie. In Dimensions du Paysage: Réflexions et Propositions Pour la Mise en Œuvre de la Convention Européenne du Paysage; Conseil de l’Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2017; pp. 243–283. [Google Scholar]

- Cagnato, A. Le Origini Del Paesaggio. Labsus Papers, May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, J. The Landscape Imagination: Collected Essays of James Corner 1990–2010; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, G. The Philosophy of Landscape. Sage J. 2007, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhan, F. L’ Esthetique Du Paysage; Librairie Felix Alcan: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Amiel, H.F. Fragments d’un Journal Intime, nouvelle éd. ed; Stock: Paris, France, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Lettini, L.; Maffei, D. La Rappresentazione Del Paesaggio; Tirrenia Stampatori: Turin, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti, G. Paesaggi Culturali. Teoria e Casi Di Studio; Unicopli: Milan, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti, G. Alle Origini Del Paesaggio Culturale. Aspetti Di Filologia e Genealogia Del Paesaggio; Unicopli: Milan, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, B. Livro Do Desassossego; Ática: Lisbon, Portugal, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Twigger-Ross, C.; Uzzell, D.L. Place and Identity Processes. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M. The Elusive Reality of Landscape. Concepts and Approaches in Landscape Research. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. 1991, 45, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M. The Concept of Cultural Landscape: Discourse and Narratives. In Landscape Interfaces; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2003; pp. 21–51. [Google Scholar]

- Antrop, M. Where Are the Genii Loci? Landscape—Our Home. In Essays on the Culture of the European Landscape as a Task; Freies Geistesleben: Stuttgart, Germany, 2000; pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Domingues, A. A Paisagem Revisitada. Finisterra J. 2001, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunto, R. Paesaggio-Ambiente-Territorio: Un Tentativo Di Precisazione Concettuale. In Bollettino del Centro Internazionale di Studi di Architettura Andrea Palladio; Progetto Trentino: Trento, TN, Italy, 1976; pp. 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Assunto, R. Il Paesaggio e L’estetica; Novecento: Palermo, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Turri, E. Il Paesaggio Degli Uomini. La Natura, La Cultura, La Storia; Zanichelli: Bologna, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tilley, C.Y. Space, Place, Landscape and Perception: Phenomenological Perspectives. In A Phenomenology of Landscape: Place, Paths and Monuments; Berg: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D. Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Poli, D. Progettare Il Paesaggio Nella Crisi Della Modernità. Casi, Riflessioni, Studi Sul Senso Del Paesaggio Contemporaneo; All’insegna del Giglio: Florence, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, G. Il Giardiniere Planetario; 22 Publishing: Milan, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, S. Cit in National Geographic Magazine, 1st ed.; The National Geographic Society: Washington, DC, USA, December 2007; Volume 212, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Naveh, Z.; Lieberman, A.S. Landscape Ecology Theory and Application, 2nd ed.; Springer Science + Bussiness Media: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Budd, M. The Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature: Essays on the Aesthetics of Nature; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, A. Why Landscape Beauty Matters. Land 2014, 3, 1251–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffero, T. L’estetica Di Schelling; Laterza: Rome/Bari, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Italian Legislative Decree. 2004. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2004-02-24&atto.codiceRedazionale=004G0066&elenco30giorni=false (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Leone, A. Riflessioni Sul Paesaggio; Aracne: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kizos, T.; Plieninger, T.; Iosifides, T.; García-Martín, M.; Girod, G.; Karro, K.; Palang, H.; Printsmann, A.; Shaw, B.; Nagy, J.; et al. Responding to Landscape Change: Stakeholder Participation and Social Capital in Five European Landscapes. Land 2018, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miccoli, S.; Finucci, F.; Murro, R. Social Evaluation Approaches in Landscape Projects. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7906–7920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop, M.; Van Eetvelde, V. Landscape Perspectives: The Holistic Nature of Landscape; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Usher, M.B. Landscape Character: Perspectives on Management and Change; The Stationery Office: Edinburgh, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Washer, D. Learning from European Trans-Frontier Landscapes. In Second Meeting of the Workshop for the Implementation of the European Landscape Convention; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, O. Portugal, o Mediterrâneo e o Atlântico; Livraria Sá da Costa Editora: Lisbon, Portugal, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar, J. As Regiões Portuguesas; Direcção Geral do Desenvolvimento Regional: Lisbon, Portugal, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson, R.; Peterson, A. Authenticity in Landscape Conservation and Management—The Importance of the Local Context. In Landscape Interfaces; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, Holland, 2003; pp. 319–356. [Google Scholar]

- Janin, C. Peut-on Faire l’économie Du Paysage Pour Gérer Le Territoire? L’agriculture dans le paysage, une autre maniére de faire du dèveloppement local. J. Alp. Res. 1995, 15, 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto-Correia, T.; Ramos, I. As Identidades Locais Em Espaço Rural: As Tradicionais e as Novas Funções Da Paisagem Rural. In Identidades Locais e Globalização; Atas da Universidade de Verão: Montemor-o-Novo, Portugal, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hilman, J. L’anima Dei Luoghi; Rizzoli: Milan, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shama, S. Paesaggio e Memoria; Mondadori: Milan, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Raffestin, C. Space, Territory, and Territoriality. Environ. Plan. Soc. Space 2012, 30, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cillo, B. Nuovi Orizzonti Del Paesaggio; Alinea: Florence, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lassus, B. The Landscape Approach; Penn University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Venturi Ferraiolo, M. Paesaggi Rivelati. Passeggiare Con Bernard Lassus; Guerini e Associati: Milan, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Weilacher, U. In Gardens: Profiles of Contemporary European Landscape Architecture; Birkhauser: Basel, Switzerland; Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Matteini, T. Paesaggi Del Tempo: Documenti Archeologici e Rovine Artificiali Nel Disegno Di Giardini e Paesaggi; Alinea: Florence, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bèlanger, P. Landscape as Infrastructure. Landsc. J. 2009, 28, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, L. Vita e Morte Del Paesaggio Industriale; Università degli Studi di Trento: Trento, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, T. Hardrock Gold: A Miner’s Tale; University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, OK, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Boca, D.; Oneto, G. Discariche, Cave, Miniere Ed. Aree Difficili o Inquinate; Il Sole 24 Ore Pirola: Milan, Italy, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Frare, G.P. Cave. Tecniche Di Coltivazione e Recupero Ambientale; Zoppelli: Treviso, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vallario, A. Attività Estrattive, Cave e Recupero Ambientale; Liguori: Naples, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brodkom, F. Codice Di Buona Pratica Ambientale Nell’Industria Estrattiva Europea; PEI Srl: Parma, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fornaro, M.; Lovera, E.; Sacerdote, I. La Coltivazione Delle Cave e Il Recupero Ambientale. Estrazione Di Materiali Per Usi Industriali e Pietre Ornamentali; Politeko: Turin, Italy, 2002; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbella, L. Arte Mineraria; Hoepli: Milan, Italy, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Gisotti, G. Le Cave. Recupero e Pianificazione Ambientale; Flaccovio Dario: Palermo, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tsolaki-Fiaka, S.; Bathrellos, G.D.; Skilodimou, H.D. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis for an Abandoned Quarry in the Evros Region (NE Greece). Land 2018, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinarelli, G. La Riscrittura Dello Scarto: Il Caso Dell’ex Cementificio Italcementi Di Albino; Milan Politecnic: Milan, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chaline, C. La Régénération Urbaine; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Di Marco, C. La Riconversione Dei Paesaggi Di Scarto: Saint-Étienne, Da Cittá Nera a Cittá Del Design; Dipartimento di Architettura, Universitá degli studi Federico II: Naples, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dumesnil, F.; Ouellet, C. La Réhabilitation Des Friches Industrielles: Un Pas Vers La Ville Viable? Vertigo Revue Électron. Sci. L’Environ. 2002, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénécal, G.; Saint-Laurent, D. Espaces Libres et Enjeux Écologiques: Deux Récits Du Développement Urbain à Montréal. Rech. Sociograph. 1999, 40, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénécal, G.; Saint-Laurent, D. Les Espaces Dégradés: Contraintes et Conquêtes; Presses de l’Université du Québec: Saint-Foy, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, M.J.Z.; Zapata, M.J.; Hall, M.C. Organising Waste in the City; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Viale, G. Un Mondo Usa e Getta. La Civiltà Dei Rifiuti e i Rifiuti Della Civiltà; Feltrinelli: Milan, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. Wasting Away; Sierra Club Books: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Di Marco, C. Drosscape, Un Concetto Trasmigrante Che Identifica Paesaggi Plurali. In Atti Della XVII Conferenza Nazionale SIU—Società Italiana Degli Urbanisti, L’urbanistica Italiana nel Mondo; Planum Publisher: Milan, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, M.C. The Ecological and Environmental Significance of Urban Wasteland and Drosscapes. In Organising Waste in the City: International Perspectives on Narratives and Practices; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- De Solà Morales, I. Terrain Vague. In Anytime; MIT Press: Cambdrige, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Pineiros, E. Terrain Vague and the Urban Imagery. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, J. Derelict Britain; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Boeri, S. The Narrowing of Land Uses. Rassegna 1990, 42, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M. Dead Cities; The New Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, P. Terrain Vague: Interstices at the Edge of the Pale; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Secchi, B. II Vuoto. Un Progetto per L’urbanistica; Einaudi: Turin, Italy, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, M.; Rahamann, H. Tokyo Void: Possibilities in Absence; Jovis Edition: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stalker. Manifesto. Available online: www.osservatorionomade.net/tarkowsky/manifesto/manifesting.htm (accessed on 9 April 2019).

- Secchi, B. Un’urbanistico Di Spazi Aperti/For a Town-Planning of Open Spaces. Casabella 1993, 597–598, 116–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kivell, P.; Hatfield, S. Derelict Land – Some Positive Perspectives. In Environment, Planning and Land Use; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 1998; pp. 118–129. [Google Scholar]

- Oxenham, J.R. Reclaiming Derelict Land; Faber: London, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Smithson, R. Sites and Settings. In Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, A.; Pagano, M. Terra Incognita: Vacant Land and Urban. Strategies; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Northam, M. Vacant Urban Land in the Amencan City. Land Econ. 1971, 47, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmell, R. Colonization of Industrial Wasteland; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Nabarro, R.; Richards, D. Wasteland: A Thames Television Report; Thames: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Boeri, S.; Lanzani, A.; Marini, E. Nuovi Spazi Senza Nome (New Nameless Spaces). Casabella 1993, 57, 74–76, 123–124. [Google Scholar]

- Lerup, L. Stim and Dross: Rethinking the Metropolis. Assemblage 1994, 25, 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.T. Readings of the Attenuated Landscape. In Slow Space; Monacelli: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 186–213. [Google Scholar]

- Doron, G. The Dead Zone and the Architecture of Transgression. City 2000, 4, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielson, T. The Return of the Excessive: Superfluous Landscapes. Space Cult. 2002, 5, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupers, K.; Missen, M. Spaces of Uncertainty; Verlag Muller and Busmann: Wuppertal, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, G. Le Manifeste Du Tiers-Paysage; Editions Sujet/Objet: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gandy, M. Concrete and Clay: Reworking Nature in New York City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, A. Reclaming the American West; Princenton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rathje, W.; Murphy, C. Rubbish: The Archeology of Garbage; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alker, S. The Definition of Brownfield. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2000, 43, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, J. Not Unlike Life Itself: Landscape Strategy Now. Harv. Des. Mag. 2004, 21, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, J. Terra Fluxus. In The Landscape Urban Reader; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Marini, S.; Santangelo, V. Re-Cycle Italy. Nuovi Cicli Di Vita Per Architetture e Infrastrutture Della Città e Del Paesaggio; Aracne: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tarpino, A. Spaesati. Luoghi Dell’Italia in Abbandono Tra Memoria e Futuro; Passaggi Einaudi: Turin, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fabian, L. Recycling City. Lifecycle, Embodied Energy, Inclusion; Giavedoni Editore: Pordenone, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Waldheim, C. Landscape as Urbanism: A General Theory; Princenton University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, J. Recovering Landscape: Essays in Contemporary Landscape Architecture. Gard. Hist. 1999, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobs, J. The Death and Life of the Great American City; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi, N. A Estetica Da Bela Natureza. In Filosofia da Paisagem, Uma Antologia; Centro de Filosofia da Universidade de Lisboa: Lisbon, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, M.C. The Great Frame-up: Fantastic Appearances. In Contemporary Spatial Politics, Spatial Practices; Sage: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- De Girardin, R.L. De La Composition Des Paysages; Champ Vallon: Paris, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, F.C. Fundamentos Da Arquitetura Paisagista; Instituto da Conservação da Natureza: Lisbon, Portugal, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Olin, L. Form, Meaning, and Expression in Landscape Architecture. Landsc. J. 1988, 2, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonesio, L. Oltre Il Paesaggio. I Luoghi Tra Estetica e Geofilosofia; Arianna Editrice: Bologna, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bonesio, L. Geofilosofia Del Paesaggio; Mimemis: Milan, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, D. The Past Is a Foreign Country—Revisited; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cervellati, P.L. L’arte Di Curare La Città; Il mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Joachim, J. Rapid Re(f)Use: 3-D Fabricated Positive Waste Ecologies. Archit. Des. 2010, 80, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corajoud, M. Le Paysage C’est L’endroit Ou Le Ciel et La Terre Se Touchent; Actes Sud: Arles, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, T. The Fundamentals of Landscape Architecture; AVA Publishing: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, E.K. Uncertains Parks: Disturbed Sites, Citizen and Risk Society. In Large Parks; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 58–85. [Google Scholar]

- Smithson, R. Incidents of Mirror-Travel in the Yucatan. In The Writings of Robert Smithson; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; pp. 94–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lassus, B. Les Continuitès Du Paysage. Urbanisme 1991, 250, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Marini, S. Architettura Parassita. Strategie Di Riciclaggio Per La Città; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marini, S. Spazi Bianchi. Progettare Lo Scarto. In L’architettura e le Sue Declinazioni; Ipertesto: Verona, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marini, S. Nuove Terre. Architetture e Paesaggi Dello Scarto; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kenneth, C. L’art Du Paysage; Arlèa: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, F.; Jiao, Y.-Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Tian, H.; Cheng, Y. Reclamation and Reuse of Abandoned Quarry: A Case Study of Ice World & Water Park in Changsha. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 85, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margiotta, S.; Sansò, P. Abandoned Quarries and Geotourism. an Opportunity for the Salento Quarry District (Apulia, Southern Italy). Geoheritage 2017, 9, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berisha, H.; Bulica, J.; Gashi, S.; Kouklidis, K.; Mastoris, J.; Dragasakis, K. Case Study on Quarry Rehabilitation and Land Resettlement in Dimce Quarry. Geo-Resour. Environ. Eng. (GREE) 2017, 2, 271–274. [Google Scholar]

- Vosloo, P. Post-Industrial Urban Quarries as Places of Recreation and the New Wilderness—A South African Perspective. Town Reg. Plan. 2018, 72, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepankar, K.A. Feasibility of Waste Marble Powder in Concrete as Partial Substitution of Cement and Sand Amalgam for Sustainable Growth. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 15, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulubeyli, G.C.; Artir, R. Properties of Hardened Concrete Produced by Waste Marble. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 2181–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, A.C. Caracterização de Rejeitados de Escombreiras de Pedreiras de Rocha Ornamental Para Aplicação Em Camadas Não Ligadas de Pavimentos Rodoviários; Duraspace: Lisbon, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, C.F.; Esteves, L.D. The Mounds of Estremoz Marble Waste: Between Refuse and Reuse. In Waste 2015—Solutions, Treatments and Opportunities; CRC Press: London, UK, 2015; pp. 305–310. [Google Scholar]

- Talento, K.; Amado, M.; Kullberg, J.C. The Metamorphosis of the Landscape: The Adaptive Reuse of Marble Waste. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Architecture and Built Environment with AWARDS, Venice, Italy, 22–24 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zagari, F. Questo è Paesaggio 48 Definizioni; Mancuso Editore: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Reference | Definition | Reference | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Corner, 2014) | There is nothing natural about landscape. It is a product of the imagination, anything that is previously imagined and afterwards represented in images. It is the result of an architectural project. | (Turri, 2003) | Social aspect of the landscape: it exists because there are those who look at it, giving it a meaning. |

| (Simmel, 2007) | Landscape derives from nature, being a part of nature itself. | (Tilley, 1994) | The landscape is the artificial result of a culture that perpetually redefines its relationship with nature, in which the subject is entirely part of it. |

| (Paulhan, 2016) | We like landscape because we like nature, and the landscape is the portrait of it. | (Cosgrove, 1998) | The social landscape has two ideal typical figures: the “Insider”, rooted inhabitant, and the “Outsider”, disinterested spectator. |

| (Amiel, 1931) (Soares, 1982) | Landscape is a state of the soul. | (Poli, 2002) | In the social landscape she also describes the figure of “care- taker”, he who takes care of the places by choice. |

| (Lettini & Maffei, 1999); (Andreotti, 1996, 1998) | Inner landscape: relations that unite places with personality and experience. | (Clement, 2008) | It is important to consider Planet Earth as a single garden of which man is the gardener, highlighting the global sense of the landscape. |

| (Twigger-Ross & Uzzel, 1996); (Jones, 1991, 2003) | Description of cultural landscape as a landscape transformed by man, where exist relations between him and the territory. | (Jakob, 2009) | There is a landscape formula which could summarize all the landscape definitions: L = S + N (Landscape= Subject + Nature) |

| (Antrop, 2000) | The landscape is a whole that is more than the sum of the parts, being the necessary synthesis for the true understanding of the whole. | (Budd, 2002) | He is in favor of a positive aesthetic that accepts all nature as beautiful, since it is not altered by man, accepting exclusively its natural changes. |

| (Domingues, 2001) | Landscape identifies itself with the object of study of geography. It is an element positioning between the natural and human sciences. | (Griffero, 1996) | The landscape, being an aesthetic component, arouses emotions in the subject that admires it. |

| (Assunto, 1976, 2006) | The landscape is a form that the environment confers on the territory. It is the country considered from the artistic point of view. |

| Reference | Definition | Reference | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Chaline, 1999) | Friche | (Lerup, 1994) | Dross |

| (Solà Morales, 1995) | Terrain Vague | (Leong, 1998) | No-man’s land |

| (Berger, 2007) | Drosscape | (Doron, 2000) | Dead zones and transgressive zones |

| (Barr, 1969); (Kivell & Hatfield, 1998); (Oxenham, 1966) | Derelict land | (Nielson, 2002) | Superfluous landscapes |

| (Smithson, 1996) | Zero panorama, empty or abstract settings and dead spots | (Cupers & Miessen, 2002) | Spaces of uncertainty |

| (Bowman & Pagano, 2004); (Northam, 1971) | Vacant land | (Clement, 2003) | Le Tiers-Paysage, les delaisses, the third landscape and Leftover lands |

| (Gemmell, 1977); (Nabarro & Richards, 1980) | Wasteland | (Johnas & Rahmann, 2014) | Brownfields, in-between spaces, white areas, Blank areas, SLOAPs |

| (Secchi, 1989) | Il vuoto (the void) | Voids | |

| (Lynch, 1990); | Urban wilds and urban sinks | (Bowman & Pagano, 2004) | Terra incognita (unknown land) |

| (Boeri, Lanzani & Marini, 1993) | New nameless places | (Cupers & Miessen, 2002) | Spaces of uncertainty |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Talento, K.; Amado, M.; Kullberg, J.C. Landscape—A Review with a European Perspective. Land 2019, 8, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8060085

Talento K, Amado M, Kullberg JC. Landscape—A Review with a European Perspective. Land. 2019; 8(6):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8060085

Chicago/Turabian StyleTalento, Katia, Miguel Amado, and Josè Carlos Kullberg. 2019. "Landscape—A Review with a European Perspective" Land 8, no. 6: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8060085

APA StyleTalento, K., Amado, M., & Kullberg, J. C. (2019). Landscape—A Review with a European Perspective. Land, 8(6), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8060085