4.1. Conflict and Post-Conflict Rwanda

The conflict in Rwanda is considered a protracted conflict that took place during the period between 1959 and 1994. Land issues are considered a major cause in that they were used as a fueling factor for the increase of ethnic tensions [

27]. Political representation and unresolved governance issues are additional causes [

28]. The first violent conflict in 1959-1963 in Rwanda resulted in half a million refugees crossing the borders to neighboring countries. This group of refugees stayed in refuge until 1994. For the period after the first violent conflict, the government of Rwanda used land as a political tool, redistributing abandoned properties to their political followers and military officers, causing illegal occupation by secondary occupants. The second violent conflict in Rwanda finished in 1994 with a genocide that caused more than one million people to die, a large number of IDPs, and more than two and a half million refugees [

29]. The Arusha Peace Agreement Document was signed in 1993. Only after the victory of the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF), which took control of the whole country by mid-July 1994, did the security situation improve. Displaced people began to return. In process terms, this moment can be considered as the start of the post-conflict period.

The emergency period in post-conflict Rwanda lasted from 1994 to 1997 and was marked by unity and reconciliation activities. After the humanitarian crisis, the main focus was on the provision of shelter, food, and providing basic living conditions for the population returning in masses [

30]. Actors on the ground did not seem to understand the importance of land issues at this time; they were totally out of the focus of activities [

31]. The time from 1997 until the end of 2002 can be seen as the early recovery period. This period involved the development of a legal framework, national policy developments, setting up new government structures, and development of strategies for implementation. The period after 2003 can be identified as the reconstruction period. It involved the implementation and execution of the legal frameworks, national policy, and development programs [

25].

In the following sub-sections, the empirical data about displacement and land administration in post-conflict Rwanda are categorized into the above three post-conflict periods (emergency, early recovery, and reconstruction periods) in order to elaborate on the nexus between displacement and land administration.

4.2. Displacement and Return during the Emergency Period in Post-conflict Rwanda

In the aftermath of the genocide of the Tutsi, many “1959 refugees” who were living in neighboring countries such as Uganda, Tanzania, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Burundi returned back to Rwanda in big numbers in 1994. At the same time, the so-called “1994 refugees”, mainly the Hutus who fled Rwanda in fear of retribution, took refuge in the same counties mentioned above. This left the land (prior to 1959 occupied by Tutsi and given to Hutu after 1963) vacant to be occupied by the returning Tutsi, the “1959 refugees”. Due to the impacts of the war and the genocide, many of the properties, including houses, had been destroyed. The authorities decided to locate the returning Tutsi to houses and fields that had been abandoned by the Hutu. During 1996-1997, the “1994 refugees” returned and witnessed that the land they had been occupying for over three decades was now occupied by other people who also claimed legal rights to the same land. At that moment, the country was facing the challenge of two successive legitimate and yet competing claims from two groups of returnees. One former local leader explained that “the government authorities convinced them to share”.

Although some respondents during the fieldwork interviews did mention that local leaders at the cell and sector level were in charge of land issues, many respondents agreed that by that time, nobody was seriously considering how to handle the land issues. Everybody was concerned about the safety of returning refugees and how to provide them with food and shelter. There were no land related complaints at the time. The interview with the former mayor recounts that “by that time, we were not thinking and working on the land issues. What mattered for us as authority was to provide food and shelter for returning refugees. Some individuals used that period of emergency and went on to grab land that was left vacant by 1994 refugees” [

3]. This moment of the emergency period shows that where displacement had occurred, land administration could have been prioritized. Elite groups normally take advantage of dysfunctional government to grab and legalize the land that either belonged to the displaced people or to the public.

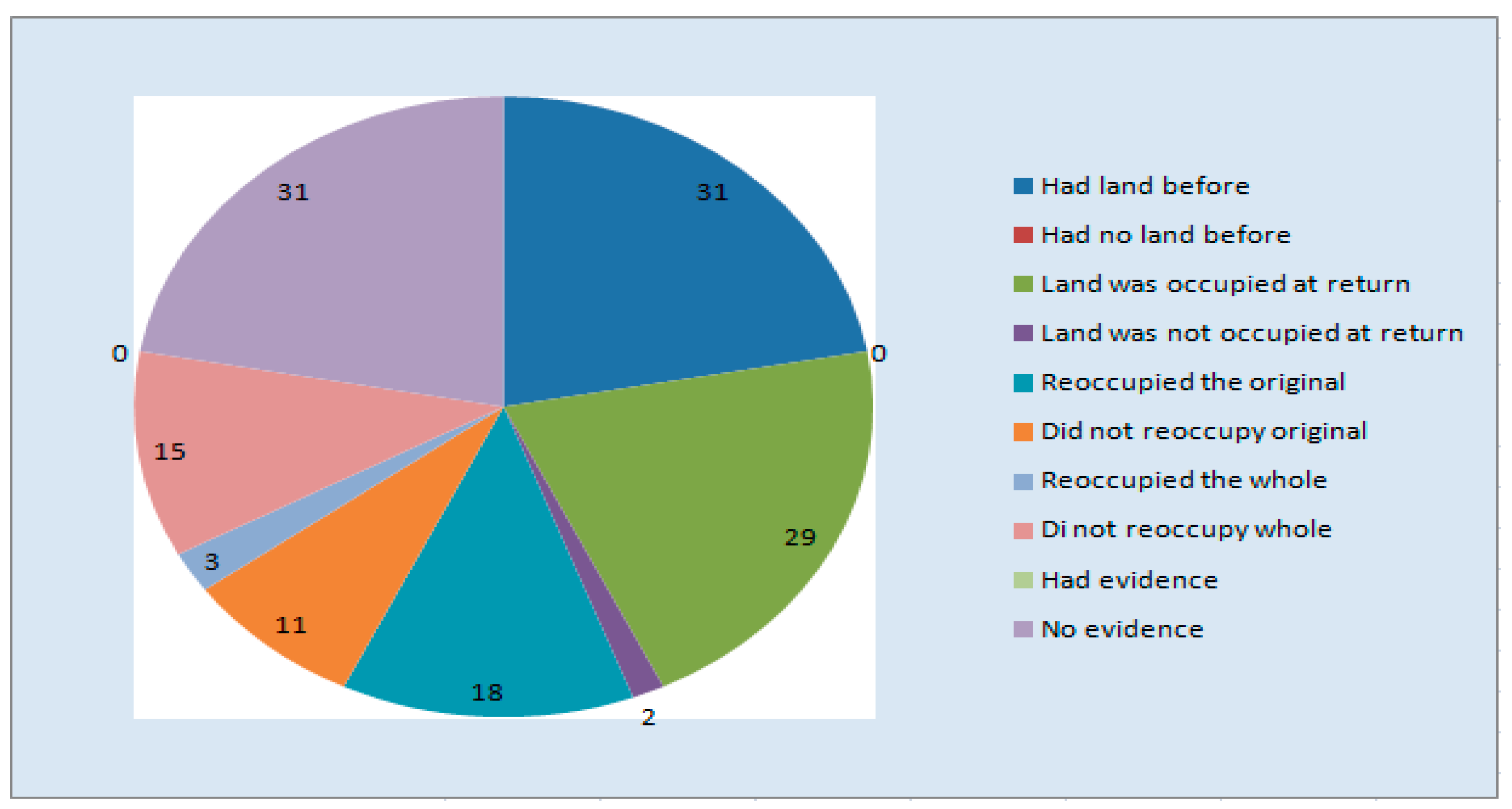

From the interviews with local people from the three groups, the “1959 refugees”, the “1994 refugees”, and the IDPs, the data reveal that a big number of people never repossessed their land, and even for those who did repossess it, it was not of the same extent as it was prior to displacement. This shows how displacement affects land tenure and land administration with long-term and permanent effects. The

Table 1 below shows the synthesis of the data analysis of the repossession of land in post-conflict Rwanda.

For better visualization, the same synthesis of the data analysis on the repossession of land in post-conflict Rwanda is also represented in the following pie chart in

Figure 1.

Discussion:

In the case of Rwanda, there was no fully operating public professional body in charge of land administration during the emergency period. Land issues tended to be handled informally, sporadically, and by officials with little skills and knowledge in land administration. This resulted in the public undertaking either illegal or informal actions, either intentionally or due to ignorance. Thus, the emergency period was characterized by responding to emergency security challenges, social and political challenges related to the big number of returning refugees, and how they could best get food and shelter. In this period, land-related issues and challenges were not considered priority issues.

4.3. Early Recovery Period in the Case of Post-Conflict Rwanda

The early recovery period was a bit different from the emergency period. In the early recovery period, the security situation started to stabilize. Since people started to plan for the future, they needed land to cultivate crops and housing, and here land claims and disputes started to come to the fore. The data collected reveal how the people and Rwandan authorities reacted to land claims and disputes in the early recovery period of post-conflict Rwanda.

During the interview with the director of the One Stop Center of the study district, he responded that “the authority could not address the issue before it could rise, as, by that time, many people were suspicious of each other so they had to wait and seek guidance or the regulations from the authority”.

After repatriation of the refugees from both the 1959 and the 1994 groups, the country had entered an early recovery period of a post-conflict state, life had turned to normal, and government institutions started working. However, land issues also grew in complexity. The fieldwork researcher wanted to identify how the authority handled the land issue after the repatriation of the displaced persons, and from respondents’ answers, it was found that all confirmed the complexity of the situation. This is how an interviewed respondent from the One Stop Center described it: “It was a challenging moment, with no legal direction to solve different overlapping rights to land by different people from different groups of returnees, so we gave local people chances to search for a solution themselves”.

Complexity in land matters manifested, for instance, in parcels of land with different claimants. These claimants varied between two to four, all claiming rights to ownership, many of whom had genuine reasons. Thus, there was no other option but to let them all share the same parcel of land, as explained by one respondent and a former leader: “We had no clear and legal formula to solve the claims of these people, so we gathered local leaders, and in a period of eight days we had the task to find the solution. The outcome was ‘land sharing’ and Imidugudu settlements, because these came out as the only approach that would allow us to cope with the situation of solving a land issue and at the same time could be used to exemplify political achievement during national campaigns for peace, unity and reconciliation”. Land sharing policy was an informal policy and was implemented differently in different sectors depending on the prevailing conditions per each sector. In principle, the “1959 refugees” had to share the same parcel of land with the “1994 refugees”, further adding to the complexity and precariousness of the situation due to the fact that these two groups knew each other as members from the periods of violent conflict. The basic framework for setting land contestations was provided in the Arusha Accord (top-down approach), but the implementation of land sharing and Imidugudu settlements was bottom-up [

17].

The Arusha Peace Agreement Document (PAD) recommended that, in relation to land matters, in order to promote social harmony and national reconciliation, refugees who left the country more than 10 years ago should not reclaim their original properties because the land might have been occupied by other people [

32].

According to the peace agreement between the Rwandan Government and the RPF, the “1959 refugees” were not allowed to reclaim and repossess their land. They were instructed to be resettled to state land provided by the government. The so-called “Imidugudu” program was meant for the returnees that did not manage to get land via land sharing. They were offered to take state land in national parks [

25]. This was not welcomed by all “1959 refugees” and often resulted in their return to their previously possessed land before the displacement took place in Rwanda. In the early recovery period, the “1959 refugees” legally challenged the government over the right to repossess their land, to which the government finally had to agree in order to avoid new claims and disputes. For instance, Mr. Ivan

1, an interviewed returnee, wondered, “when you look to the way these people were expelled, you would see that it would be unfair not to allow them to resettle in their place of origin”. Thus, the authorities decided to let these people reoccupy their land and share with the others that had acquired it in the period 1962–1994 [

3].

As seen above, secondary occupants could be 1959 returnees, 1994 returnees, IDPs, state, or the church. Since it was confirmed by the data collected that the majority of “1959 refugees” did not reoccupy their land, it was paramount to know how the Rwandan government solved such an outstanding legitimate claim. The interview with the former minister of local government answered the researchers’ concerns: “The law was clear, all the land belonged to the state. So the government took control of land, it was easy to declare the state requisition since the land tenure allowed it. That’s why the sharing principle was deployed and people had to accept it because they had no alternative. As leaders we had no other legal solutions; so we had to opt for unconventional ad-hoc solutions”.

Such as in the emergency period, at the beginning of the early recovery period, government had limited staff with required skills and knowledge to deal professionally with land issues. In post-conflict Rwanda, the actors involved in implementing the land sharing process were local people who were tasked to implement it themselves while supervised by their local leaders. This was the moment when the land claims and disputes over land were at their peak. To conduct the land sharing process, a land claim committee of four people was chosen, representing the four groups, respectively—that is, one representing the “1959 refugees”, one the “1994 refugees”, one the IDPs, and one for the survivors of the Tutsi genocide. All were supervised by the cell chairman. Each cell reported to the sector councilor. One interviewed respondent answered that, “As we were still in a period of mistrust and suspicion, we choose committees from different groups, that is one person from 1994, one from 1959, one from genocide survivors, one from IDPs and the head of the cell as the representative of the authority” [

3].

However, in addition to the many land claim controversies between the two main groups of the displaced people during the early recovery period, other land claims arose, adding to the nature and the degree of the complexity. Fieldwork data collection revealed new challenges that surfaced, emanating from practices of land sharing.

The following excerpt provides an example that illustrates the complexities involved in the case of shared family land:

Jean and Pierre are brothers; and together they owned 3 hectares of land before 1994. In 1994, Pierre fled to take refuge in fear of retribution. Immediately after the end of the war, Jean had to share the land with another person, Mark. Mark was a 1959 returnee. Pierre returned in 2000 and asked Jean for his part. But Jean no longer had Pierre’s part. So, Jean asked Pierre to share Jean’s part of the land that the latter had received during the land sharing process. Pierre did not accept this and lodged a land claim through the mediation committee for restitution of their family land against Mark. Pierre lost the case and later decided to turn to an ordinary court against the state.

Discussion:

The early recovery period in post-conflict Rwanda was characterized by an improved security situation. Once all returnees were taken care of, people and Rwandan authorities started planning their future through appropriate reforms, the new constitution, and established appropriate legal frameworks. Because in this period all displaced people returned, land issues became a paramount challenge. Tackling the complex land issues was achieved through land sharing and Imidugudu settlements, which were ad-hoc solutions that intended to support peace unity and reconciliation. With respect to land issues, this period witnessed a peak in land claims and land disputes. The setting up of the mediation committees at village/settlement levels, including members of all four affected groups, showed to be a very helpful and effective tool in addition to the three level state land dispute mechanisms. Through instruments like the PAD, these measures were enforced to pave the way forward towards peace, unity, and reconciliation.

4.4. Reconstruction Period in the Case of Post-Conflict Rwanda

The period of reconstruction begins when a country is stable and embarks on institutionalizing long term development programs to foster economic growth and sustainability. In Rwanda, one of the development programs was the Land Tenure Regularization (LTR) program from 2008 to 2014. LTR aimed to improve agricultural productivity, enhance economic development, and reduce social tensions. The program was in line with the adoption of the new constitution, national land policy, promulgation of organic land law (currently changed to new land law), and the establishment of a public institution with the task to oversee the management and use of land in the country.

While during this period, the implementation of land reforms determined by land policy and law was meant to foster economic growth, authorities continued to face the challenge of an increasing number of contradictory land claims and disputes. These originated in the emergency and early recovery periods and how land issues had been handled during these earlier post-conflict periods. While many of these land claim and distribution issues were family matters, they did often have their roots in the practices of land sharing promoted in previous post-conflict periods. The words of one respondent summarize the situation as follows: “Almost all of the claims are family cases but mostly related to land sharing”. The case of Mr. Green illustrates the complexity of the situation:

Mr. Green left the country in 1959 after the massacre of his father and grandfather, They had 30 hectors of land with a forest and a house in it. His land was redistributed to local people by the then government in 1962. Mr. Green returned back in 1994 and found that those who had been occupying the land were displaced just before he returned. Mr. Green re-occupied his land. During the 1997 land sharing, he refused to share the land with anybody, claiming that the land used to be his family’s land and of all the descendants of his late grandfather the late Mr. Gray. As the country regained stability, many of the people who had received the land from the then government and occupied that land (in the period 1962-1994) returned and started to lodge claims to the authority over the right to the same land that Mr. Green had re-occupied. In 2009, there were 37 claimants all claiming rights over the same 30 hectares of land.

Throughout the research and interviews conducted in [

3], the responses from different interviewees revealed that many of the complaints received were related to: (1) the Tutsi-Hutu conflicts of 1959 and 1994; (2) the land sharing practices of 1996–2003; (3) land of the genocide survivors, especially orphans’ land, which was now occupied by others or by the state; (4) conflicts between family members due to how land sharing was handled; and (5) related to land taken by the Imidugudu settlement.

Exploring the nature of these competing claims more closely, it was found that some of the claims made by one of the partners in land sharing were fraudulent. This resulted in only partial official registration of documents and family members filing claims against one another, contesting the results of land sharing. In some cases, land sharing was unfair. In other cases, some family members used the situation of other family members’ longer time absence. Complaints related to the Imidugudu settlement concerned mainly land that belonged to the orphans of the 1994 genocide. From the nature of these complaints that were further processed in the official state legal system (the three level land dispute mechanism), it became clear that the continued contradictions and new filing of land claims, as well as land related disputes, were associated with previous periods of displacement.

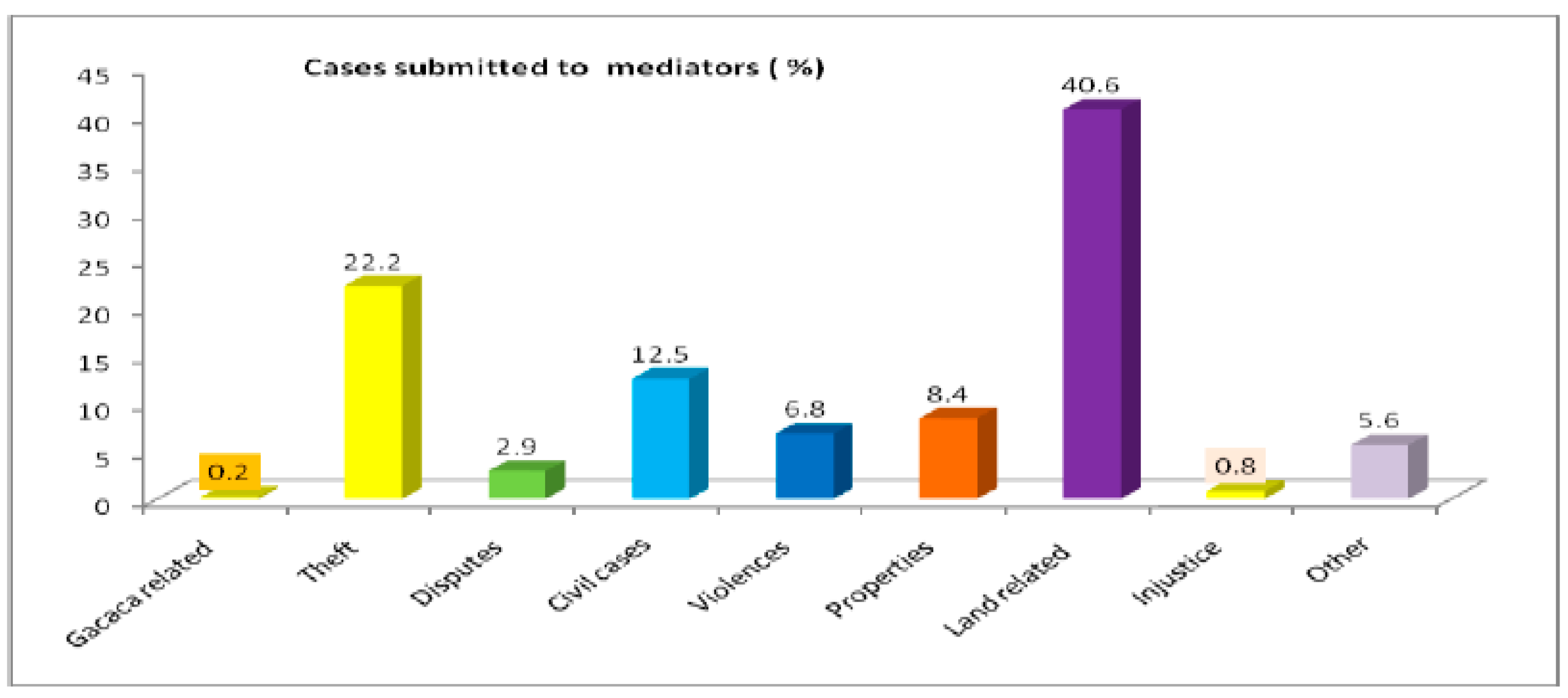

Although some interviewed respondents attributed contradictory land claims and disputes to poor governance that led to the displacement of people, many respondents attributed the continuation of the problem to the post-conflict period and how land issues had then been handled. As one respondent stated, “We receive claims that are not related entirely on displacement, but on how the land issue was handled after the displacement, especially when land sharing occurred”. When asked how by the researcher, the response was that, “Some claimants say that, for example, family land was given to one person who shared with a returnee without other family members getting anything”. Based on secondary data received from the National Secretariat for Mediation Committees, it was observed that many of the cases handled by these committees are land related, and given the responses received from respondents, many of the cases received are related to displacement. The following

Figure 2 represents the variety of cases submitted to the mediation committee in one cell; here, land-related cases dominate, making up 41% of the nine different types of cases.

In addition to the findings from

Figure 2, respondents from National Secretariat for Mediation Committees acknowledged that all received land related cases were solved before or during the implementation of the LTR program. The received and solved land related cases by these committees coupled with almost all land sharing cases (for which “the government authorities convinced them to share”, as stated in

Section 4.2) and disputed family matters related to land suggest that land disputes and claims were in big numbers and serious threats to the fragile post-conflict situation.

Reviewing the general report of the LTR program (secondary data source from fieldwork from RNRA) for the whole territory of Rwanda, it was noted that 0.13% of demarcated parcels with complete information were under dispute in court and therefore remained unregistered as per LTR regulations. In addition, there were 1,494,943 non-registered parcels (14% of demarcated land), the information for which was incomplete due to the fact that the true owners had either been killed and no close kin were found to take over the land, or the original owners had been displaced and never returned. The following

Table 2 provides more detailed figures from the general report of LTR program.

Land parcels that were under scrutiny regarding claim legitimacy or under dispute during the LTR process were skipped in the process and registered in a claims register, and the respective claimants were directed or referred to competent authorities or the court. Once a decision was taken for one of such parcels, it would then be registered again under the final, true owner’s identity. An interviewee summarized the process as follows: “During LTR, we used a claims register, where we registered all the parcels that were in conflict, of which no owner of that land would be registered on it until an administrative document is produced by the party that could prove to be the true owner or by court decision”.

The case study of Gillingham and Bruckle (2014) on LTR identified the following as key success factors for the LTR process: political commitment, a detailed LTR approach developed in an earlier phase of the program, and the program’s flexibility. Their case study identified some points that need attention in the longer term—further development of the land administration system, as well as financial and judicial sustainability are required [

33].

Discussion:

It was not until the reconstruction period that the government of Rwanda really recognized the importance of land and land administration as important state functions with high priority for the government’s political agenda. The LTR program and appropriate legal institutional and organizational adjustments were identified. Ad-hoc policies and activities performed in regard to land sharing and Imudugudu settlements that were not conventional but rather aimed at the development of peace, unity, and reconciliation were developed further, and the land was registered during the LTR project. Nevertheless, the continued high number of land claims and land disputes directly related to concerns about longer term land tenure security hampered these efforts.

Because claim competition and disputes during this period originated from previous post-conflict periods, the example illustrates the importance of bringing land formalization and administration to the forefront of post-conflict activities early on in the peace building and state development process.