Abstract

This philosophical paper explores the aesthetic argument for landscape conservation. The main claim is that the experience of beautiful landscapes is an essential part of the good human life. Beautiful landscapes make us feel at home in the world. Their great and irreplaceable value lies therein. To establish this claim, the concepts of landscape and “Stimmung” are clarified. It is shown how “Stimmung” (in the sense of mood) is infused into landscape (as atmosphere) and how we respond to it aesthetically. We respond by resonating or feeling at home. The paper ends by indicating how art can help us to better appreciate landscape beauty. This is done by way of an example from contemporary nature poetry, Michael Donhauser’s Variationen in Prosa, which begins with “Und was da war, es nahm uns an” (“And what was there accepted us”).

1. Thought Experiment

Think of your favourite places in nature, where you like to go hiking or cycling or where you just like to be, watching, listening, feeling, enjoying it all. Now imagine that all these places no longer exist, that natural beauty has become extinct. How would this affect the quality of your life? Would it affect it only marginally, or not at all, or fundamentally? Let me illustrate this thought experiment with two examples.

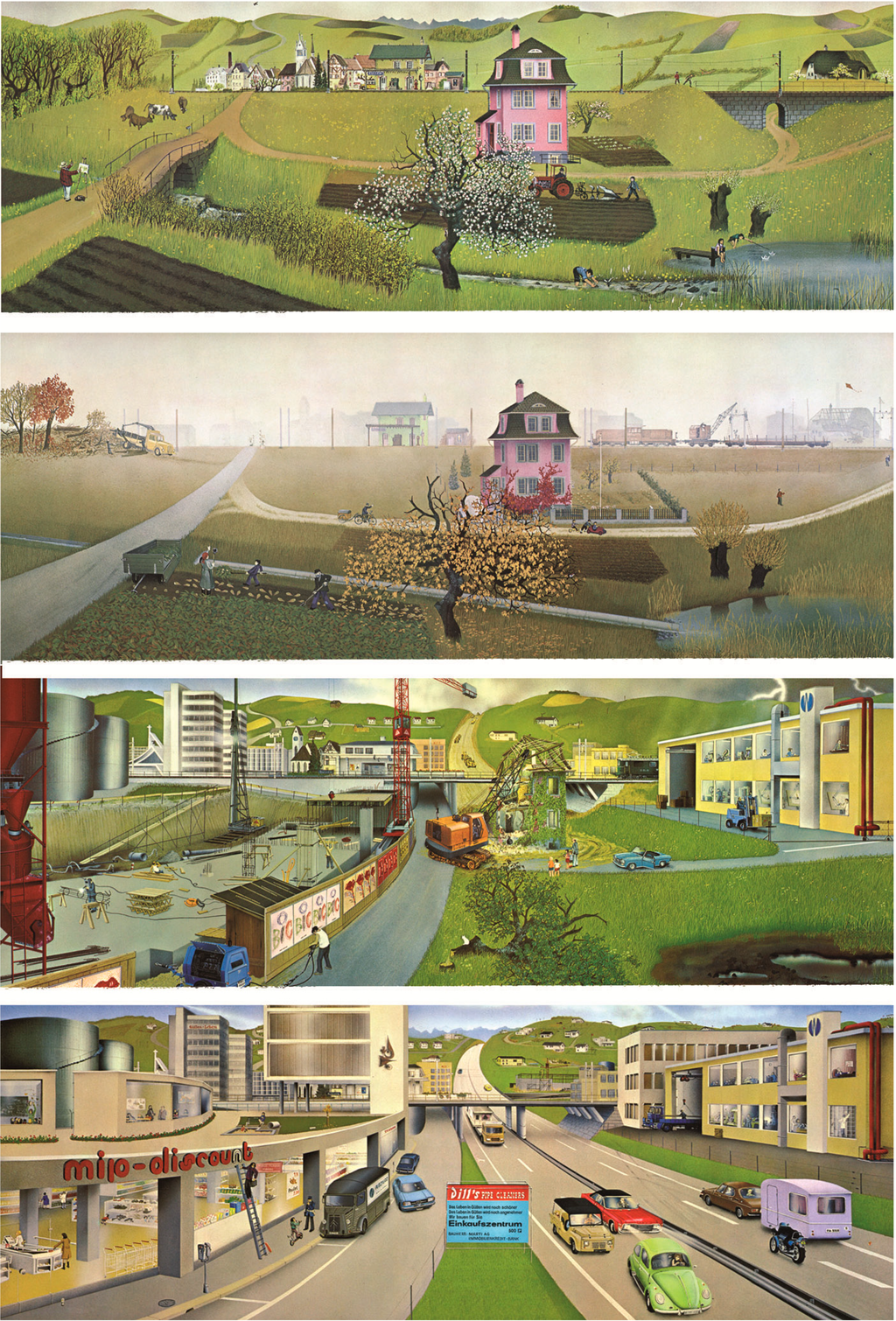

The first example is a set of pictures, Alle Jahre wieder saust der Presslufthammer nieder (in English, roughly: every year the jackhammer’s pounding returns) painted by Jörg Müller [1]. In Figure 1, you find four of the seven pictures in Müller’s series. Can you guess what these pictures represent? Which country? Which year?

Figure 1.

The changing countryside (© by Jörg Müller).

The pictures show a typical Swiss countryside and how it changed between the years 1953 and 1972. Can you tell what season it is in the various pictures?

In the first picture, it is obviously springtime, the fruit tree in the middle of the picture is in full bloom; in the second picture it is autumn, the leaves are yellow. However, what about the season in the last picture? It is difficult to tell, is it not? For nothing much remains of nature. The trees, meadows and fields are gone, the cows are gone, the brook and the pond. All that remains is the grass. The grass is green all year round. As it happens, it is autumn, the mini-tree planted on the roof of the discount store has yellow leaves.

When I think of my own favourite places, I think of something like the first picture. In fact, the place where I live in Switzerland still looks a little bit like it. If you wanted to punish me, you could take me to the highway median strip in the last picture and abandon me there for an hour or two. I would hate it: this busy, noisy, stinking, ugly non-place. I would definitely not want to live in a world where this yellow-grey human crust has covered the entire surface of the Earth (For a scientific study about the changing Swiss countryside see Die ausgewechselte Landschaft [2]. The photographs on the back cover of this work show what Switzerland looks like in many places today: “levelled, plot aligned, drained, regulated, hypertrophied, devoid of species diversity, obstructed, destroyed by urban sprawl, illuminated, cut open, channelled, covered in artificial snow, over travelled, wired.”).

My second example is more radical. It is the American science fiction film Soylent Green from 1973, directed by Richard Fleischer. The film is set in New York in the year 2022. New York has 40 million inhabitants and is suffering from overpopulation, pollution, dwindling resources, unemployment, poverty, dying oceans, and a hot climate due to the greenhouse effect. Much of the population survives on processed food rations. One of them is “soylent green”, allegedly made of plankton. The film is about how Detective Thorn and his aged, wise friend Solomon (Sol), who remembers life before the current miserable state, find out what soylent green is really made of.

Detective Thorn searches the apartment of a murdered member of the board of the company that produces soylent green, and helps himself to some of the luxuries he finds there, like real bourbon, fresh vegetables, and a flank steak, which Sol then cooks for them. Here is a quote from their conversation over dinner:

Sol: Son of a bitch. I haven’t eaten like this in years.Det. Thorn: I never ate like this.Sol: And now you know what you’ve been missing. There was a world, once, you punk.Det. Thorn: Yes, so you keep telling me.Sol: I was there. I can prove it.Det. Thorn: I know, I know. When you were young, people were better.Sol: Ah, nuts. People were always rotten. But the world was beautiful.

What Sol and Detective Thorn find out is that “soylent green is people”—it is made of human remains. Unable to live with this discovery, Sol seeks assisted suicide at a government clinic called “Home”. The death-scene, in which Sol is hygienically dispatched with the help of piped-in light classical music and movies of flowering fields and breaking waves, flashed before him on a towering screen, is regarded as the best scene in the film. Ironically, the actor who played Sol (Edward G. Robinson) died of cancer 12 days after the filming. By the way, a food substitute, called “soylent”, has been available for shipping in the U.S. since April 2014—to save you, as it says in the advertisement, the time, money and effort that usually go into preparing food. Just google “soylent”.

Let me go back to the question I started with: How would a world devoid of landscape beauty affect your quality of life? Here are three possible answers: 1. not at all; 2. only marginally; and 3. fundamentally.

- The loss of landscape beauty would not affect the quality of my life at all: Beautiful landscapes may be a luxury that is “nice to have” from time to time, but I can live a perfectly happy life without them. There is so much else that life has to offer: romantic love, freedom, social recognition, you name it. Besides, we live in a world in which millions of people are starving: You cannot eat natural beauty!This position may come in several variants:

- I can do without all beauty, really.

- I love beauty, beautiful music, painting and literature. However, landscape beauty leaves me cold, it does not touch me. I am a city dweller anyway, a wholehearted urbanist.

- I love landscape beauty, but I believe it is not that special, it can be replaced by other kinds of beauty. I would be just as happy reading literature instead, for example.

- The loss of landscape beauty would affect the quality of my life, but only marginally: I love beautiful landscapes and believe that they are irreplaceable. Still, you cannot have everything, and there are many ways to have a good life. You have to make choices. A world lacking natural beauty, would be an impoverished world, just like a world lacking music or painting would be impoverished. However, this would not prevent me from being able to have a fairly good life. I would simply seek other sources of fulfilment.

- The loss of landscape beauty would affect the quality of my life fundamentally: The experience of natural beauty is a necessary part of my good life. I could not live well without it. (This is Sol’s attitude, I guess. Sol would probably consider Thorn’s life as lacking, even though Thorn himself does not seem to be missing anything. Thorn even suspects that Sol is nostalgic or sentimental: “I know, I know. When you were young, people were better.”—Objective quality of life must be distinguished from subjective good or bad feelings. Missing something (subjective) is not the same as lacking something essential (objective). The thought experiment that I asked you to perform is about how the loss of landscape beauty would affect the objective quality of your life.).

I could go on listing further possible answers to my question, for example: 4. my life would be downright bad without landscape beauty or 5. it would be miserable; or, moving to the other extreme, 0. my life would actually be better, as I hate nature (and beauty) anyway, it disgusts me. However, I will stick to what I believe are the most probable answers.

2. Main Claim

The view I want to defend, my main claim, is a generalized version of position 3, namely, that the experience of landscape beauty is an essential part of the good human life. We humans cannot fare well without it. The reason for this is that the experience of beautiful landscapes makes us feel at home in the world. Their great and irreplaceable value lies therein (This claim is stronger than the one I used to defend in my earlier writings on environmental ethics, see [3]).

Why is it important to defend this view? It is important primarily for reasons of nature conservation. The aesthetic argument is one of the best nature conservation arguments we have. There are, to be sure, also other good arguments, like the basic needs argument (we need clean air to breathe) or the hedonistic argument (green has a soothing effect, sunlight is stimulating) (See [3] again for a critical taxonomy of all major anthropocentric and physiocentric nature conservation arguments). Still, the aesthetic argument is special, as it can substantiate our intuition that nature is more than a resource to be managed; it is an “other” which speaks to us, it has intrinsic value. So, we have to make the aesthetic argument as strong as we can. If it can be shown that landscape beauty is necessary for a good human life, and if moral respect and justice require that all human beings can live well, here and in the rest of the world, now and in the years to come (“can live well”, not “must”; nobody is to be forced), this would provide a powerful argument in support of the conservation of landscape beauty, and thus of nature.

3. Method

I will defend the claim about the great and irreplaceable value of landscape beauty philosophically, clarifying concepts, such as the concepts of landscape and “Stimmung”, and building, step by step, a rational argument in its favour. Clarifying concepts requires distinguishing them from neighbouring concepts. As Ludwig Wittgenstein famously put it: “I’ll teach you differences”. You can see the most important concepts and their neighbours at a glance when you look at the headings of the following sections.

The philosophical method I employ does not deny that all our concepts are cultural constructions and that cultures and concepts change in time. The 18th-century German romantic movement, for example, did much to deepen our faculty to appreciate landscape beauty, but it did not invent it, or so I will hold. As my main claim is anthropological, I will look for concepts with a universal core. How these concepts have changed with time is not my topic here.

4. The Concept of Landscape

In order to clarify the concept of landscape I first have to say what nature is. Nature is that part of the world which has not been made by human beings but comes into existence, changes, and vanishes more or less by itself. The opposite of “nature” in this sense is “artefact”, something made by human beings like a table, computer, or statue. This understanding of the concept of nature can already be found in Aristotle.

The amount of pristine nature or wilderness is rapidly decreasing in our modern world. Most of what we call “nature”, the conservation and aesthetic contemplation of which I am concerned about, lies in fact somewhere between the two extremes: pure nature and pure artefact. In fact, wilderness may often be too threatening to allow for aesthetic contemplation. A case in point is the changed aesthetic valence of the Alps. Its valence changed from repulsive ugliness to attractive sublimity [4].

In nature, we can distinguish between individual natural organisms (like plants and animals) and things (like rocks) on the one hand, and larger natural units (like landscapes) on the other. Most landscapes today are cultivated and not untouched or wild. They are syntheses of natural and cultural processes [5,6]. They are not necessarily less beautiful because of that; consider, for example, the gardenlike English landscape.

There is no sharp boundary between landscapes and gardens (or parks), as again England with its landscape gardens shows. Gardens are, first, laid out for aesthetic enjoyment; they stand between art and nature in this respect. Second, they typically surround a house and are themselves surrounded by a fence; they mediate between the house and the landscape [7].

To regard landscape as larger natural unit is only one understanding of it. This topographical understanding, for which I opt here, must be distinguished from two more restricted aesthetic ones: first, landscape as a larger natural unit in aesthetic contemplation, and second, as a larger natural unit in autonomous aesthetic contemplation (see below). All three understandings concern our everyday concept of landscape. I will not address more specific, scientific or academic, landscape definitions as they all presuppose and build upon the everyday concept. The everyday concept is the common ground on which we all stand if we want to have fruitful debates across disciplines (For an overview of the multitude of more specific landscape definitions see [8]; for views which stress the constructed character of landscapes see [9,10]).

4.1. Larger Natural Unit

In 12th-century Old High German, “lantscaf” denoted a larger natural area and its population. In the 15th-century Netherlands, the term could also refer to a painting of a larger natural unit; art historians still talk of “landscapes” in these terms. If landscapes are larger natural units, what constitutes their unity? As I shall suggest in the next section on “Stimmung”, it is atmosphere that provides this unity. Today, the boundaries of landscapes are no longer also political as they were in the beginning, as the German synonym “Gebiet” (“region”, from “gebieten” = to rule) makes explicit.

4.2. Larger Natural Unit in Aesthetic Contemplation

According to this aesthetic understanding, you encounter landscapes only when you attend to what is around you for its own sake. You do not experience landscapes when all you are after is recreation or research.

4.3. Larger Natural Unit in Autonomous Aesthetic Contemplation

The second, even more restricted aesthetic understanding is closely linked with Joachim Ritter’s well-known essay on landscape aesthetics [11] (Ritter, in fact, follows Georg Simmel [12,13]). For Ritter, the phenomenon of landscape begins with Petrarch’s ascent of Mont Ventoux in 1336, since Petrarch in this excursion and its literary reflection attended to nature as such and not only to nature as the book of God. This position is standard in contemporary landscape aesthetics [14,15,16].

However, it could be argued that also the contemplation of landscape that has not yet emancipated itself from the religious or metaphysical world-view and lacks autonomy in this sense is an aesthetic contemplation, albeit not a pure but a symbolic one. After all, these pre-Enlightenment people did not just see letters in the book of God, but rivers, valleys and hills. Consider, for example, the “locus amoenus” in Plato’s Phaedrus (On the appreciation of landscape in antiquity see [17]).

5. The Concept of “Stimmung”

The German word “Stimmung” is untranslatable (arguably even more untranslatable than “Heimat”, where “being at home” or living in a “place” as opposed to a space, at least comes close). “Stimmung” covers three phenomena, while its English and French counterparts (“mood”, “attunement”, “ambience”/“ambiance”, “humeur” or “atmosphère”) usually cover only one or two [18,19]. The three phenomena covered by “Stimmung” are: harmony, mood, and atmosphere.

5.1. Harmony

Harmony or being in tune is the original meaning of “Stimmung” from the 16th-century. Musical instruments were said to be in tune and ready to be played, and later, in the 18th-century, the same was said about the faculties of the human soul. In the Critique of Judgement, Immanuel Kant famously talks about the harmony, “proportionierte Stimmung”, of the faculties of imagination and understanding in aesthetic contemplation.

5.2. Mood

Moods belong to the sphere of human affective experiences. In contrast to standard emotions (like anger, sorrow, or joy), which are about something or other in particular, moods (like being cheerful, satisfied, or “blue” and gloomy) have no specific objects, but rather they are about life and the world at large.

Both, (specific) emotions and (general) moods, are to be distinguished from bodily feelings, which live in the body and are not about anything at all. Bodily feelings come in two variants, too. There are specific bodily feelings, like headaches, which are located in the head, and general ones, like fatigue, which pervade your whole body (Cf., e.g., [20]; for these well-established distinctions in the philosophy of the emotions).

Moods form the basis of our psychic life; they modulate and integrate us (creating harmony, as in Section 5.1). Some moods come and go, others are more permanent and make up part of our character. Some moods are genuine, whereas others are artificial, produced by drugs. Genuine moods degenerate when they are no longer directed to the world but inverted, sought and enjoyed for their own sake, as in kitsch and sentimentality (remember how Thorn thinks that Sol is wallowing in sentimentality when he yearns for the good old days?) (The classic study on moods is by Otto Friedrich Bollnow [21]; which sadly has not been translated into English [22]; on kitsch and sentimentality see apart from Bollnow: [23]; and [24]).

5.3. Atmosphere

When landscapes, cities, or buildings are said to have atmosphere or aura they are regarded not only as integrated wholes (as in Section 5.1), but also as full of feeling, e.g., as full of peace or melancholy (as in Section 5.2). The atmospheres of landscapes change with the weather, the time of day and the season. These changing atmospheres can be distinguished from the more permanent atmosphere or character of landscapes. The character of landscapes is constituted by their physiognomy, their climate, and their history. Both the character and the changing atmospheres of landscapes are objective phenomena, even if subjective factors like personal memories and moods also play a role in actual landscape experience [25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

It is landscape character that gives landscapes their unity. Landscape character is the principle of unity behind the topographical concept of landscape (outlined in Section 4.1). Because not all experience of atmospheric, larger natural units is aesthetic rather than hedonistic or scientific, the aesthetic concepts of landscape (in Section 4.2 and Section 4.3) seem too narrow.

What follows from this conceptual arrangement is that, when a larger natural area loses its character due to human destruction, it lacks the unity necessary for being a landscape. It turns into an expressionless heterogeneity, into a non-place or landscape garbage—as we can see in Jörg Müller’s last picture. It does not turn into an ugly landscape. Ugly landscapes are the opposite of aesthetically attractive and in this wide sense “beautiful” landscapes (When cities lose their character, they turn into non-places too. Cf. Alexander Mitscherlich’s influential pamphlet [32]; and Jörg Müller, in his second set of pictures [33]).

To sum up, my two central claims so far are first, that landscapes are larger natural units, and second, that their principle of unity is character. This is the conceptual basis on which I will now try to reconstruct aesthetic landscape experience.

6. How “Stimmung” is Infused into Landscape

Phenomenologists such as Martin Heidegger, Hermann Schmitz, and Gernot Böhme maintain that to ask how “Stimmung”, in the sense of “mood”, is infused into landscape, as atmosphere, is the wrong question to ask. For them, “Stimmung” is already out there. When we move in a landscape we enter its “Stimmung”. The phenomenon of “Stimmung” is prior to the divide between subject and world, or so they say.

Yet, this understanding of “Stimmung” makes it seem like a more primitive phenomenon than it actually is. Adults differentiate between themselves and the world and still they experience “Stimmung”. So, the question remains: How is it infused into landscape? There are four main answers to this question. I will argue for the last one, the “expressive model”. In order to better understand it, it is helpful to compare it with the first three, simpler models.

6.1. Causal Model

According to the first answer, the fact that a landscape is peaceful means that it makes us peaceful, but is not really peaceful itself; to call it peaceful only projects the feeling it causes in us back onto it.

6.2. Associative Model

According to the second answer, the fact that a landscape is peaceful means that it makes us think of something peaceful, but is not really peaceful itself.

Both the popular causal and associative models fail to realize that the peaceful feeling is intimately related to the landscape. How the landscape looks, sounds, and smells is integral to a full description of the feeling. Contrast this with a bottle of wine that makes you cheerful and remember the good old days. To describe your cheerfulness you do not need to talk about how the wine tastes.

6.3. Animistic Model

According to the third model, the fact that a landscape is peaceful means that it is filled with spirits, fairies, or nymphs, which really are peaceful themselves. While small children may believe this [34], as adults we know that it is not the case. This leaves us with the expressive model.

6.4. Expressive Model

The fact that a landscape is peaceful means that it expresses peacefulness and really is peaceful itself, but not in the literal sense (as in the former model). Moritz Geiger, a pupil of Edmund Husserl, spelled out the expressive model for colours and landscapes, contrasting both the causal “Bewirkungstheorie” (theory of effect) and the animistic “Belebungstheorie” (theory of animation) with his own expressive “Gefühlscharaktertheorie” (theory of emotional character) [35].

The English philosopher Roger Scruton developed the expressive model in more detail for music and before that for architecture [36,37] (On architecture see also Nelson Goodman [38]). In music we can distinguish three levels: the primary and physical level of vibrations in the air; the secondary and phenomenal level of heard sounds—“audibila” that the deaf person cannot hear; and the tertiary and musical level of tones heard in the sounds. This tertiary level makes up the atmosphere of music. To hear tones in music moving up and down, attracting and repelling each other, striving forward and lingering, crying out and comforting is to hear sounds through the metaphor of human life: of human movement in space, of human action and feeling. A metaphor is the deliberative application of a term or phrase to something that is known not to exemplify it. Hearing music is metaphorical hearing. It is hearing with double intentionality, hearing both sounds and tones by hearing tones in sounds.

Building on Scruton, atmospheres in landscapes can be understood as tertiary aspects like atmospheres in music. Landscape atmospheres are as real as their colours and sounds on the secondary level, which in turn are as real as the light waves and the air vibrations on the primary level.

However, atmospheres in landscape are more primitive than atmospheres in an expressive art like music. Expressive art is a communication from soul to soul. It has a message. It pursues meaning. It articulates, explores, and meditates on human concepts in a structure all of its own. Expressiveness in art is an achievement. This does not hold for landscapes. Compared with art, the expressiveness of landscapes is a superficial phenomenon. Still, our habit of seeing expression in landscapes is irresistible. As Roger Scruton puts it:

“Because we are subjects the world looks back at us with a questioning regard, and we respond by organizing and conceptualizing it in other ways than those endorsed by science. The world as we live it is not the world as science explains it, any more than the smile of Mona Lisa is a smear of pigments on a canvas. But this lived world is as real as the Mona Lisa’s smile”.[39]

Against imperialist tendencies in the natural sciences and their mathematically calculating dominion over nature—“die rechnende Weltbemeisterung”, as Theodor Litt calls it, the gazing devotion to the expressive richness of the world—“die schauende Hingabe”, is to be defended [40]. As Malcolm Budd in [41] notes, “no satisfactory account has been given of the experience of nature as the bearer of expressive qualities“. In Allen Carlson’s online survey on environmental aesthetics in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy [42], expressiveness is not even mentioned. In fact, Carlson’s own “scientific approach” [43] runs counter to it. According to his approach, we need scientific knowledge to appreciate nature aesthetically. But do we really need to know that a bird’s song is a territorial marker in order to hear it as a melody? In contrast to this, Emily Brady [44] at least stresses the role of imagination (as fourfold: “exploratory”, “projective”, “ampliative”, and “revelatory”). What she calls “projection” and “seeing as” corresponds in part to my expressive model. In recent years some phenomenological approaches, often following in the footsteps of Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty, have managed to enter English-speaking environmental aesthetics, see e.g., [45].

7. Ways of Experiencing Landscape “Stimmung”

As a basis for understanding the specifically aesthetic way of experiencing the “Stimmung” of landscapes, four more basic kinds of landscape experience have to be distinguished: perception, empathy, sympathy, and infection. The contemporary debate on empathy, in which “empathy” can mean any of these different phenomena, is still in need to regain the conceptual standard that phenomenology had reached at the beginning of the last century, most notably in the writings of Max Scheler and Edith Stein. They distinguish between “Wahrnehmung” (perception), “Einfühlung” (empathy), “Mitgefühl” (sympathy), and “Ansteckung” (infection) [46,47,48,49].

7.1. Perception

When you perceive that a landscape is peaceful, you remain affectively more or less neutral. You simply realize that it is peaceful (in the metaphorical sense).

7.2. Empathy

When you empathize with a peaceful landscape, you move with its atmosphere but you do not share it. Why would you not share it? Perhaps, it is because you are not in the right mood for it, but have agreed to make note of its character.

As the example of cruelty makes clear, empathy occupies an intermediate position between perception and sympathy. Cruel people are not sympathetic to the suffering of their victims. Still, they need empathy to enjoy it thoroughly.

7.3. Sympathy

When you sympathize with a peaceful landscape you move with its atmosphere and share it. You resonate emotionally, like you do when you listen to a good piece of music. Sympathy is an emotion in the full sense, including bodily feeling, cognition, evaluation, and behaviour, while empathy is “only” a deeper, more vivid mode of cognitive understanding.

7.4. Infection

When you are infected by a peaceful landscape, you are swayed by its atmosphere.

Infection is causal, while perception, empathy, and sympathy are intentional; they are directed to the expressive quality of the landscape. In being directed to an “other”, they presuppose some distance between self and other. Infection is not alert to this distance. Infection is relevant for mental health and wellness, but it is itself not an aesthetic phenomenon in the non-instrumental, disinterested or contemplative sense of the term.

7.5. Aesthetic Contemplation

To experience a landscape aesthetically is not only to attend to it, to perceive it (Section 7.1) and empathize with it (Section 7.2) for its own sake, but also to move with it and share it (Section 7.3) for its own sake.

In stressing first, the distance built into sympathy, and second, its disinterestedness, this understanding of aesthetic experience is obviously Kantian in a loose sense, even if Kant’s own aesthetics is much colder than that. The emotion of sympathy does not play any role in it. Still, with Kant, it is important to distinguish between the aesthetic experience itself and its physiological and psychological, e.g., hedonistic, impact or effect. The main thesis of my paper about how landscape beauty makes us feel at home in the world does not concern impact or effect. Rather, it concerns the quality of the aesthetic experience itself [50].

As social beings we enjoy sympathetic coordination. A paradigmatic case of this is dancing. Perfect coordination or resonance feels like unity although it is, strictly speaking, nothing but perfect coordination, as Martin Buber knows when he writes about the mystic in I and Thou:

“What the ecstatic man calls union is the enrapturing dynamic of relation, not a unity arisen in this moment of the world’s time that dissolves the I and Thou, but the dynamic of relation itself, which can put itself before its bearers as they steadily confront one another, and cover each from the feeling of the other enraptured one. Here, then, on the brink, the relational act goes beyond itself; the relation itself in its vital unity is felt so forcibly that its parts seem to fade before it, and in the force of its life, the I and the Thou, between which it is established, are forgotten”.[51,52]

Otto Friedrich Bollnow also talks about “Vereinigung” (unification) in his unpublished manuscript “Mensch und Natur” from the 1980s. Theodor Litt speaks of “liebende Einswerdung” (loving fusion) and “Amalgamierung” [53]. Josef König in contrast just calls it “Resonanz” in [50], as does, today, Hartmut Rosa in [54].

We call something “beautiful” (in the general sense) when it invites and rewards this kind of intrinsic sympathetic contemplation.

8. How Beautiful Landscapes Make Us Feel at Home in the World

Beautiful landscapes invite and reward sympathetic contemplation for its own sake. As we experience them synaesthetically, feeling them with all our senses, not only with our eyes and ears, which are more capable of aesthetic neutrality and distance than our noses, tongues, and fingers are, sensual feeling and, yes, also infection is part and parcel of aesthetic landscape experience [55,56,57,58].

It is both the synaesthetic feeling and the sensed Buberian unity that explain why we feel immersed, at home, in beautiful landscapes. Beautiful landscapes are irreplaceable in that they fulfill our longing to be part of the natural world, the world that is just there, contingently, which comes into being, changes, and vanishes by itself. Beautiful landscapes heal the rift between subject and nature, both the nature out there and the nature in us. As Otto Friedrich Bollnow says:

“It is disastrous when humans live in the stony deserts of cities, in rooms that more often than not are fully air-conditioned, and are scarcely affected anymore by the changing seasons. For this reason, it is extremely important that humans experience the rhythms of nature as well as the rhythms that order their own lives; that they feel the pauses and slow down for them, and then respond to the reawakening of life in the spring with all their energy, experiencing it as a radical renewal. But this can only occur in the intense experience of the sprouting green of nature. As Hölderlin writes in his lovely verses, the “holy green” “refreshes” us and transforms us into youths again”.[59]

Beautiful landscapes teach us how to “dwell” on earth, Bollnow continues, following Martin Heidegger. They give us a sense of place and make us honour it. They invite us to put down roots somewhere and identify and care for it, as our special “Heimat” [60,61].

8.1. Three Understandings of Feeling at Home

There are stronger and weaker forms of feeling at home in nature. So far, I have mainly focused on the strongest one, perfect sympathetic coordination which feels like unity.

Often, however, we succeed only partially in our attempt at sympathetically moving with a landscape. Our failure need not be due to ourselves, it may also be due to the object. The classical distinction between the beautiful and the sublime is relevant here. For our purposes, it can be reconstructed as follows. Only the beautiful (now in a more limited sense than before and no longer synonymous with “aesthetically attractive”) allows us to be fully taken up in the object. To be sure, the sublime, in its infinite extent and power, entices us to sympathetically move with it, too. The subject enjoys participating in its magnitude and power. However, the subject also feels painfully reminded of her own insignificance and vulnerability. The sublime confronts us with a tension between a celebration of the object and self-negation. Still, insofar as the sublime appeals to us and invites us to partially move with it, neither leaving us cold nor threatening us existentially, we can talk about feeling at home (in a weaker sense) in sublime nature too [62]. Otto Friedrich Bollnow, in his unpublished manuscript “Mensch und Natur” [63], makes a similar point. He stresses that we should not confuse our being at home in nature (“Geborgenheit”) with absolute security (“Sicherheit”), as nature always also has aspects of the uncanny and the threatening (“zugleich immer etwas Unheimliches und Bedrohliches”). On Bollnow’s anthropology of dwelling, see [64].

A third understanding opens up when we attend to the landscape that surrounds us not as landscape as such, but in relation to ourselves, that is, in its functionality for our own good life. In Kantian terminology, the latter kind of experience is directed at the “dependent” beauty of the landscape and not at its “pure” beauty (“beauty” now again in the wide sense). A landscape that looks as if it affords a good human life is beautiful in the functional sense. It is ugly if it does not. Thus, contrary to “positive aesthetics” [43,65], there is a sense, in which nature can be ugly.

The distinction between functional and pure beauty must not be confused with the point I made right at the beginning (in Section 4), namely, that most landscapes today are marked by human labour. Even pristine nature can be functionally beautiful. Admittedly, it will be less frequently so than cultivated nature. It is no accident that we speak about the “garden” Eden. In functionally beautiful landscapes we feel at home, not only because they have a pleasant physiological and psychological impact on us, but also because they indicate, by the way they look, sound, and smell, that they can support humans and provide for their needs. Evolutionary aesthetics, which traces our idea of beauty back to our sense for landscapes with a high survival value for our species, like the savannah, finds its limited justification here [66].

In his Ästhetik der Natur, Martin Seel calls this functional aesthetic dimension “corresponsive” and contrasts it with two other aesthetic dimensions, the “contemplative” and the “imaginative”. His contemplative dimension concerns the pure beauty of nature, whereas his imaginative dimension looks at nature through the glasses of art, especially landscape painting. As Seel’s Neo-Kantian aesthetics is the most refined recent work on environmental aesthetics I know of, it makes sense to explore how my approach relates to his (Unfortunately, Seel’s book [67] has not yet been translated into English and the international English-speaking discussion remains unaware of it. Allen Carlson in his online survey does not even cite it. For an English translation of some of Seel’s core ideas, see [68]; for a critical review see [69]).

8.2. Contemplation, Correspondence, and Imagination

Seel explains these three dimensions by referring to the view across Lake Constance from his former office at the University of Constance.

The first, contemplative experience of nature sees nature “as cheering space of detachment from active life” [70]. It perceives nature by abstracting from the importance and value of things for recognition and action. The I dissolves and disappears in the space of nature. This view of Lake Constance is free of meaning; it shows a constantly changing sensual play of appearances—the dancing of light reflexes, the corrugation of the waves, the fanning of the colours—but does not endow them with any particular significance other than what they are.

The second, corresponsive perception of nature experiences nature “as a place that illustrates a successful human life” [70]. It opens up an articulated space that no longer is meaning-free, but rather highly meaningful, in which the synaesthetic I is enclosed. This existentially interested gaze onto Lake Constance sees the refreshing coolness of the lake’s surface in summer and the warming vapour of the mist in winter. It remains attached to certain places in memory or in feelings of anticipating joy.

Third, the imaginative experience of nature renders nature “as a mirror of the human world full of images” [70]. Nature is seen as if it were an artwork freely improvising on other works and styles of art. The I finds that her horizon is widened as a result of this double reflection of our being-in-the-world. That kind of gaze onto Lake Constance perceives the way in which the lake communicates with Lorrain and Watteau, then with Turner and Hodler.

The experience of landscape that I have dealt with here is not tantamount to Seel’s “corresponsive” mode, as one might assume on first sight, but rather close to his “contemplative” mode. In contrast to Seel I believe that both, and in fact all three kinds of nature experience, can make us feel at home or “enclosed” in the world. Seel tends to exaggerate the differences between them anyway. What he calls “imaginative” is not really an aesthetic dimension in its own right, but rather an important indication about how much our view of nature is influenced by cultural history. Seel also goes too far when he denies that a landscape we experience contemplatively can have any expressive articulateness, any anthropomorphic expression. Seel’s formalism or autonomism of contemplation is reminiscent of similar movements in the aesthetics of music and architecture that pretend to be exclusively concerned with a meaning-free play of appearances while the language they employ to render this disinterestedness is permeated by expressiveness. Is not the “dancing” of light reflexes or the corrugation of waves on Lake Constance anthropomorphic and expressive, after all?

Yet, what is particularly convincing is Seel’s anti-metaphysical stance. He sternly resists every temptation to read the corresponsive or contemplative beauty of nature as a “wink” (in Kant’s words) given to us by the world or by God, signalling to us that we are welcome in the world. Roger Scruton seems less transparent and steadfast regarding this point. Who is reassuring us, we want to ask, when Scruton writes about the experience of natural beauty in his book Beauty: “It contains a reassurance that this world is a right and fitting place to be—a home in which our human powers and prospects find confirmation.” [71]? My main thesis about landscape and home is not meant in a metaphysical or even theological manner, although aesthetic landscape experience no doubt triggers a lot of thinking (as Kant puts it); it triggers also metaphysical and theological aesthetic ideas.

9. Aesthetic Education: Michael Donhauser’s Variationen in Prosa

No artificial substitute of nature can make us feel at home in the world which is just there. This is the point of the death-scene in Soylent Green, in which Sol is dispatched with the help of movies of flowering fields and breaking waves. Still, art has a function; it may teach us, how to experience natural beauty in a better, fuller, keener, and deeper manner. Art presents us with icons of our emotions. Roger Scruton once again:

“We encounter works of art as perfected icons of our felt potential, and appropriate them in order to bring form, lucidity, and self-knowledge to our inner life. The human psyche is transformed by art, but only because art provides us with the expressive gestures towards which our emotions lean in their search for sympathy—gestures which we seize, when we encounter them, with a sense of being carried at last to a destination that we could not reach alone, as when a poem offers us the words of love or grief which we cannot find in ourselves. Art realizes what is otherwise inchoate, unformed, and incommunicable. It does this because we recognize its expressive properties, and appropriate them as vehicles of our own emotion”.[72]

(For more on cultivating emotions through art see [73,74].)

Read, by way of an example, the first variation in prose “And What Was There Accepted Us” by the Viennese nature poet Michael Donhauser. This poem lures us through the music of its language into a benign atmosphere at a lake, both on the purely sensual level and on the aesthetic level of non-instrumental contemplation and sympathetic coordination. Like its counterpart in nature, Michael Donhauser’s poem envelops us and makes us feel at home:

“Und was da war, es nahm uns an, verloren ging, was streifte noch als Lächeln bald die Frage, ob, denn wo sie war, so nah verzweigt, war Früchten gleich, die reiften, fiel, was schön war, gross, was ungetrübt, es war ein Weg, ein Duft, und was durchs Laub als Luftzug fuhr, das war ein Sehen, war wie Wut, erinnert schon als Lust und schau, wie standen wir am See im Licht, da voll die Dolden, da der Tag uns gütig fast umfing, mit Armen, die wie trunken noch erblühten dann und sanken, süss und mild.”“And what was there accepted us, what was lost was what, as yet a smile, caressed the question presently of whether, for where that was, so close and branching out, was like a fruit that mellowed, fell, was lovely too, largesse, a thing unblemished, it was a way, a fragrance, and what ranged breeze-like through the leaves was seeing, was like fury, remembered now as rapture, and look, how by the lake we stood in the light, the clusters full, and the day all but embracing us, benign, its arms as if in drunken blossom sinking, sweet and soft”.[75]

(The English translation is [76]. For more on the form of prose poetry see [77].)

The poem begins with an upbeat note before introducing the subject of the following variations, the “what”. There is, however, also an abstract “we” that has left behind “the question presently of whether” and feels accepted, embraced, intoxicated by a gentle, full, pure and benign atmosphere at a lake. If it was not for the breeze that announces the evening and thus the end of the day, for the “all but” of being embraced, and for the “sinking” of the blossoming arms that embrace, one would have to call this atmosphere “paradisiacal”. The gentleness is rendered by the repeated use of the German “w” and the multiple use of the dark and quiet “a” right at the beginning: “Und was da war, es nahm uns an”. The preterite tense, rather unusual in German poetry, may have been chosen in this case to underscore these specific sound patterns, since “a” and “w” form the basic mood or “Stimmung” of all the variations. This basis supports first, the fullness and richness of the “voll die Dolden” with its associated sound pattern of “golden”, then, the purity, beauty and splendour in the vowel pattern “i–a–e” in the declamation: “Wie standen wir am See im Licht”, and finally, the force, almost violent, of the climactic realization: “Das war ein Sehen, war wie Wut”. The beauty that the sound evokes in this first variation is part of its message.

Yet, being at home in nature does not equal being at home in paradise. Indeed, if you read on in Donhauser’s prose poem cycle, the summer mood declines and becomes autumnal or, more precisely, one of “Sommersneige”, waning summer, to take up the title of a poem by Georg Trakl—an atmosphere akin perhaps to Emily Dickinson’s famous renditions of the Indian summer, for example in “As imperceptibly as Grief/The Summer lapsed away/Too imperceptible at last/To seem like Perfidy”.

This is a mixed atmosphere of beauty with a touch of sublimity, an atmosphere of sweetness with a touch of melancholy, an atmosphere of enjoying the fullness and ripeness of summer whilst dreading the coming of winter. Entering this atmosphere one rehearses, as Roger Scruton writes with regard to Schubert’s music, “something that it is very hard to feel—the impulse to selfless gratitude for the gift of life, in full awareness that the gift will soon have vanished” [78].

This mixed atmosphere is being inflected throughout the cycle. Its most mature expression can probably be found in a variation that relates the experience of a bitter night of solitude in a room in which there was only a bunch of tulips that “seemed to celebrate their wilting” (“zu feiern schien das Welken”) [79]. The tulips provoke reflections on the fact that we—in spite of the “memento mori” and all the premonitions of our ultimate demise—may have led our lives too carelessly. Only those who abandon themselves to the plentitude and whirl of life while not neglecting destitution and death, may have assumed an appropriate attitude towards life, they may find themselves “uniquely presented” with blessings (“wie beschenkt nur ohnegleichen sich fände, was hingegeben dem Taumel schaute die Fülle als Not”) [79].

When we go along with these landscape “Stimmungen”, be it under the guidance of art or not, then we put ourselves into a direct relation to our creatureliness. We are gaining a grounding “Stimmung” that is commensurate with the basic conditions of having been born and having to die—a grounding “Stimmung” that carries and modulates our psychic activities in their entirety. In a purely artificial world, by contrast, we run the risk of losing our humanity; we are threatened by an oblivion of and alienation from being. We are in need of beautiful landscapes, so that we do not forget what it means to be part of nature as a human. This is why the experience of beautiful landscapes is a necessary constituent of the good human life.

Acknowledgments

The research on this essay was supported by the Rachel Carson Center in Munich in 2014. I am also indebted to Michael Donhauser and the students who participated in our joint seminar on poetry and philosophy at the University of Basel in spring 2012.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Müller, J. Alle Jahre wieder saust der Presslufthammer nieder oder Die Veränderung der Landschaft; Sauerländer: Aarau, Switzerland, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ewald, K.; Klaus, G. Die ausgewechselte Landschaft; Haupt: Bern, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, A. Ethics of Nature; de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1999; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Bätzing, W. Die Alpen; Beck: München, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, F. Urban landscape perspectives. Land 2014, 3, 342–350. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, O.; Cousins, S.A.O. Historical landscape perspectives on grasslands in Sweden and the Baltic region. Land 2014, 3, 300–321. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, D.E. A Philosophy of Gardens; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff, T.; Trepl, L. Landschaft, Wildnis, Ökosystem. Zur kulturbedingten Vieldeutigkeit ästhetischer, moralischer und theoretischer Naturauffassungen. In Vieldeutige Natur; Kirchhoff, T., Trepl, L., Eds.; Transcript: Bielefeld, Germany, 2009; pp. 13–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D.E. Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape; Wisconsin University Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Olwig, K.R. Landscape, Nature, and Body Politics; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, J. Landschaft. In Subjektivität; Ritter, J., Ed.; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 1974; pp. 141–166. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, G. Philosophie der Landschaft. In Aufsätze und Abhandlungen 1909–1918; Simmel, G., Ed.; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 2001; pp. 471–482. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, G. The philosophy of landscape. Theory Cult. Soc. 2007, 24, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Smuda, M. (Ed.) Landschaft; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 1986.

- Kemal, S.; Gaskell, I. (Eds.) Landscape, Natural Beauty, and the Arts; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993.

- Kirchhoff, T.; Trepl, L. (Eds.) Vieldeutige Natur; Transcript: Bielefeld, Germany, 2009.

- Elliger, W. Die Darstellung der Landschaft in der Griechischen Dichtung; de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, L. Classical and Christian Ideas of World Harmony. Prolegomena to an Interpretation of the Word “Stimmung”; John Hopkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Wellbery, D.E. Stimmung. In Ästhetische Grundbegriffe 5; Barck, K., Fontius, M., Schlenstedt, D., Steinwachs, B., Wolfzettel, F., Eds.; Metzler: Stuttgart, Germany, 2003; pp. 703–733. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ze’ev, A. The Subtlety of Emotions; MIT: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bollnow, O.F. Das Wesen der Stimmungen; Vittorio Klostermann: Frankfurt, Germany, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, M. Feelings of Being: Phenomenology, Psychiatry and the Sense of Reality; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, M. Sentimentality. Proc. Aristot. Soc. 1976, 77, 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Scruton, R. Culture. In The Aesthetics of Music; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997; pp. 485–488. [Google Scholar]

- Bollnow, O.F. Mensch und Raum; Kohlhammer: Stuttgart, Germany, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Bollnow, O.F. Human Space; Hyphen Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Augé, M. Non-Lieux; Editions du Seuil: Paris, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Augé, M. Non-Places; Verso: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, G. Atmosphäre; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, H. Der Leib, der Raum und die Gefühle; Arcaden: Ostfildern, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, E. The Fate of Place; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mitscherlich, A. Die Unwirtlichkeit unserer Städte; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, J. Hier fällt ein Haus, dort steht ein Kran und ewig droht der Baggerzahn oder Die Veränderung der Stadt; Sauerländer: Aarau, Switzerland, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhard, U. Kind und Natur; Westdeutscher Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, M. Zum Problem der Stimmungseinfühlung. Z. Für Ästhet. Allg. Kunstwiss 1911, 6, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Scruton, R. The Aesthetics of Music; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Scruton, R. The Aesthetics of Architecture; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, N. How buildings mean. In Reconceptions in Philosophy and Other Arts and Sciences; Goodman, N., Elgin, C.Z., Eds.; Hackett: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 1988; pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Scruton, R. The face of the earth. In The Face of God; Continuum: London, UK, 2012; pp. 128–129. [Google Scholar]

- Litt, T. Naturwissenschaft und Menschenbildung. In Naturwissenschaft und Menschenbildung; Quellen und Meyer: Heidelberg, Germany, 1959; p. 166. [Google Scholar]

- Budd, M. Nature’s expressive qualities. In The Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, A. Environmental aesthetics. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Zalta, E.N., Ed.; Summer 2012 ed. Available online: http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2012/entries/environmental-aesthetics/ (accessed on 22 October 2014).

- Carlson, A. Aesthetics and the Environment; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, E. Imagination and the aesthetic appreciation of nature. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 1998, 56, 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Benediktsson, K.; Lund, K.A. (Eds.) Conversations with Landscape; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2010.

- Scheler, M. Wesen und Formen der Sympathie; Bouvier: Bonn, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Scheler, M. The Nature of Sympathy; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, E. Zum Problem der Einfühlung; Herder: Freiburg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, E. On the Problem of Empathy; ICS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- König, J. Die Natur der ästhetischen Wirkung. In Vorträge und Aufsätze; Patzig, G., Ed.; Alber: Freiburg, Germany, 1978; pp. 256–337. [Google Scholar]

- Buber, M. Ich und Du; Lambert Schneider: Darmstadt, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Buber, M. I and Thou; Continuum: London, UK, 2004; p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Litt, T. Naturwissenschaft und Menschenbildung; Quellen und Meyer: Heidelberg, Germany, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, H. Weltbeziehungen; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, H. Der Adel des Sehens. In Organismus und Freiheit; Jonas, H., Ed.; Vandenhoeck: Göttingen, Germany, 1973; pp. 198–225. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, H. The nobility of sight. Philos. Phenomenol. Res. 1954, 14, 507–519. [Google Scholar]

- Berleant, A. The Aesthetics of Environment; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, G. Atmosphäre. Essays zur neuen Ästhetik; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bollnow, O.F. Die Stadt, das Grün und der Mensch. In Zwischen Philosophie und Pädagogik; Bollnow, O.F., Ed.; Weitz: Aachen, Germany, 1988; pp. 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. Bauen, Wohnen, Denken. In Vorträge und Aufsätze; Heidegger, M., Ed.; Klostermann: Frankfurt, Germany, 1951; pp. 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. Building dwelling thinking. In Poetry, Language, Thought; Heidegger, M., Ed.; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, T. The emotional experience of the sublime. Can. J. Philos. 2012, 42, 125–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bollnow, O.F. Mensch und Natur. Unpublished manuscript, 1980s. p. 25. Available online: http://www.otto-friedrich-bollnow.de/doc/MenschundNatur.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2014).

- Schütz, G. Menschliches Wesen als Wohnenkönnen. Otto Friedrich Bollnows hermeneutische Anthropologie. In Otto Friedrich Bollnow. Rezeption und Forschungsperspektiven; Kümmel, F., Ed.; Vardan Verlag: Hechingen, Germany, 2010; pp. 189–224. [Google Scholar]

- Budd, M. The Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, D. The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure, and Human Evolution; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Seel, M. Eine Ästhetik der Natur; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Seel, M. Aesthetic arguments in the ethics of Nature. Thesis Eleven 1992, 32, 76–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, C. Beyond the frame—Art, ecology and the aesthetics of Nature. Thesis Eleven 1992, 32, 114–128. [Google Scholar]

- Seel, M. Ästhetische Verhältnisse. In Eine Ästhetik der Natur; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 1991; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Scruton, R. Beauty; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Scruton, R. A note on Levinson. In The Aesthetics of Music; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997; p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- Hepburn, R.W. The arts and the education of feeling and emotion. In Wonder and Other Essays; Hepburn, R.W., Ed.; University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 1984; pp. 88–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bieri, P. Wie wäre es, gebildet zu sein? In “Was den Menschen eigentlich zum Menschen macht …” Klassische Texte einer Philosophie der Bildung; Lang, H.-U., Steenblock, V., Eds.; Alber: Freiburg, Germany, 2010; pp. 205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Donhauser, M. Und was da war. In Variationen in Prosa; Matthes & Seitz: Berlin, Germany, 2013; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith, I. And what was there. In Moving Pictures. Judith Albert with Poetry by Michael Donhauser; Krebs, A., Ed.; Lady Margaret Hall: Oxford, UK, 2012; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, H.-J. Vers und Prosa bei Baudelaire. In Vier Veränderungen über Rhythmus; Frey, H.-J., Ed.; Urs Engeler: Basel, Switzerland, 2000; pp. 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Scruton, R. Value and structure. In The Aesthetics of Music; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997; p. 359. [Google Scholar]

- Donhauser, M. Variationen in Prosa; Matthes & Seitz: Berlin, Germany, 2013; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).