Abstract

In the last two decades, socio-economic changes in Europe have had a significant effect on land cover changes, but it is unclear how this has affected mountain areas. We focus on two mountain areas: the eastern Italian Alps and the Romanian Curvature Carpathians. We classified land cover from Earth observation data after 1989 by using applied remote sensing techniques. We also analyzed socio-economic data and conducted semi-structured interviews with local stakeholders. In Italy, most of the land conversion processes followed long-term trends. In Romania, they took off with the sudden political changes after 1989. In both areas, forest expansion was the biggest, but potentially not the most consequential change. More consequential changes were urbanization in Italy and small-scale deforestation in Romania, since both increased the risk of hydro-meteorological hazards. Stakeholders’ views were an added value to the spatial analysis and vice versa. For example, stakeholders’ explanations resolved the seeming contradiction of decreased economic activity and increased urbanization (Italian site), as a consequence of secondary home building. Furthermore, spatial analysis revealed that urbanization in Romania was less significant with regard to consequences for the wider human-environment system than many stakeholders thought.

1. Introduction

Throughout the centuries, European mountain areas have been shaped gradually by human activities, resulting in diverse landscapes. Then, the 20th century brought rapid socio-economic transformation. Thus, land use and land cover change are now intense in spatial and temporal terms, presenting a break to the long steadiness of landscape evolution [1]. Examples of sudden changes range from land abandonment after the collapse of the Soviet Union [2], substantial expansion of urban areas after the introduction of a market-based economy [3], to illegal logging due to warfare and corruption [4]. In mountains, we see a tremendous decline in agriculture, improved accessibility through new infrastructure and the increased development of recreational areas [5,6,7].

These land cover changes can have strong impacts on human well-being on a broader scale, since mountains provide many services, e.g., water provision, agricultural production, hazard prevention and others [6,8,9]. One main concern is that land cover changes can lead to increased hazard risks, e.g., through local changes of the runoff dynamics [8,9]. Another important trend is that of land abandonment and natural reforestation in hilly and mountain areas, combined with the removal of riparian vegetation and urbanization in the valleys, contributing to habitat loss, lower biodiversity and a more homogenous mountain landscape [1,10,11].

The strong link of mountain land cover change to human well-being has recently led to an increased interest of policy makers and planners in the causes and consequences of these changes [12]. Researchers call for increased efforts to monitor and analyze land cover changes, especially in areas affected by high rates of socio-economic changes [13].

The main goal of this study was to investigate land cover changes in two major European mountain areas: the mountain community of Gemonese, Canal del Ferro and Val Canale in the Italian Alps, and the Carpathians of Buzau County in Romania. The areas were selected due to their particular socio-economic trajectories since 1989 and their representativeness in terms of physical and biogeographic characteristics for the Alps and Carpathians, respectively. The Alps and the Carpathians are two major mountain areas in Europe. Here, the main European rivers originate, providing water and energy to a large portion of the European population. Both are acknowledged as major European biodiversity hotspots [14,15]. The Alps are considered to be one of the first tourist destinations, and here, tourism is a major economic factor [16]. In the Romanian Carpathians, tourism is still underdeveloped, however, with major potential [17].

In general, there is more research on land use and cover changes in the Alps than in the Carpathians. Focusing on the Italian Alps, the research undertaken so far ranges from identifying changes to the forest cover [18], land abandonment [19], the main drivers of land cover change [11], the role of socio-economic and natural characteristics [7] and the consequences of land cover changes on biodiversity [10]. However, there is a lack of research investigating the consequences for land cover of the significant socio-economic changes linked to the industrialization of Europe: migrations to the lowlands and the expansion of traffic routes due to mechanization [16,20]. Our Alpine study area lies in the Eastern Italian Alps, which have been experiencing the highest depopulation rates and decreases in economic activities in the last three decades [21].

In the Carpathian region, research focuses on the abandonment of grasslands and cropland and the expansion of forests as the most widespread land cover changes [22,23,24,25,26]. Though more rapid in nature, these changes are in line with the long-term trends for all European mountain areas, including the Alps [27]. However, there is another interesting process that is particular to the Carpathian region: the increase in the quantity of (illegal) logging, as well as changes in the spatial pattern of the logging [28,29,30,31,32]. Processes like this are linked to the fall of Communism since 1989 and the expansion of the European Union in the years after 2000. Their effects on land cover and the related consequences are as yet understudied.

For both case study areas, our main research interests were related to land cover changes as a possible result of sudden socio-economic changes. More importantly, we were interested in which land cover changes were most significant in terms of consequences to the environment and human activities. To map and analyze land cover changes, we used applied remote sensing techniques. To study the driving forces behind land cover changes more in depth, we performed a series of interviews with stakeholders and experts.

2. Study Areas

2.1. Gemona, Canal del Ferro and Val Canale

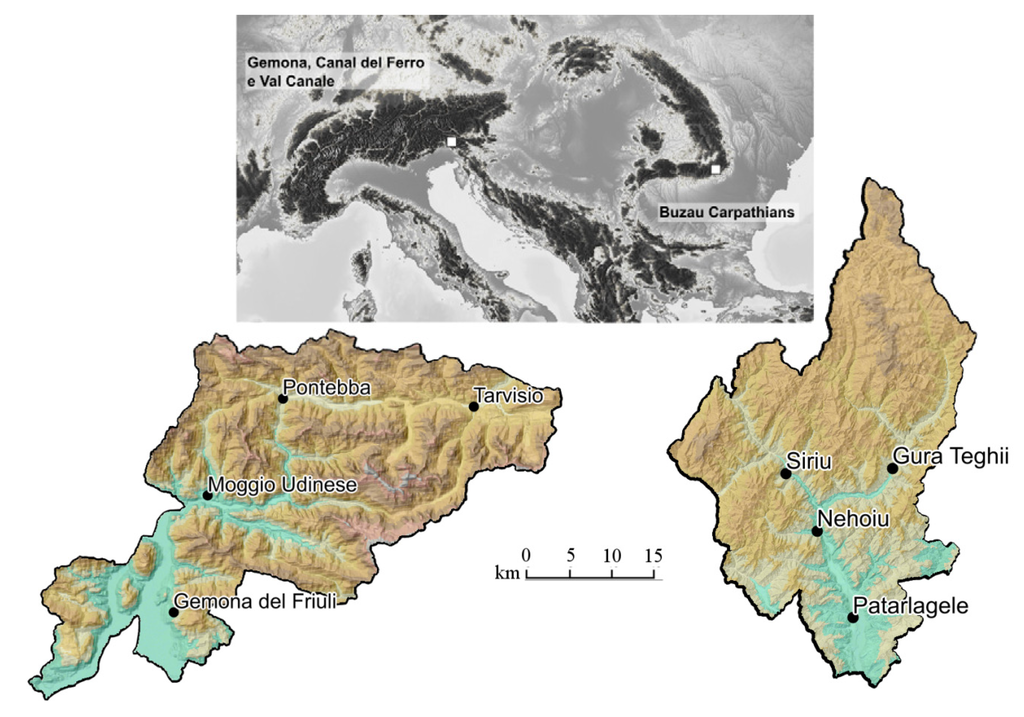

The mountain community of Gemona, Canal del Ferro and Val Canale study lies in the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia in northeastern Italy on the border with Austria and Slovenia (46°30′25″N, 13°26′25″E, Figure 1). It covers an area of 1,148 km2 and consists of 15 municipalities. It is situated between the Carnic and Julian Alps, which rise up to 2,754 m, in the discharge area of the river Fella, a major left-hand tributary of the Tagliamento River. The relative relief in the upland area is more than 1,500 m. The area is characterized by steep slopes and high precipitation levels; the Fella river catchment has a mean altitude of 1,140 m a.s.l. and an average mean precipitation of 1,920 mm [33]. The area consists mostly of limestone [34]. The area is seismically active and exposed to many natural hazards, among which are landslides, flash floods and debris flows [34]. In the past, the main river valley was defined by a mosaic of grasslands, settlements and forests. Today, it is intensely urbanized due to numerous pieces of infrastructure. Animal husbandry in the uplands is dominated by cattle. On the southern edge of the case study area begins the lowland Friulian plain, strongly altered due to urbanization and intensified large-scale agriculture in the decades after the Second World War. The total population of the area is 33,286 inhabitants, with only two settlements over 4,000 inhabitants (Tarvisio and Gemona del Friuli, the latter situated in the lowlands). The area is of high importance for Italy, serving as a communication and energy corridor to neighboring Austria and Slovenia. It is subject to numerous efforts of the regional and national government to develop infrastructure and to mitigate risks. Interest for preserving the population and the landscape is high, also due to the growing touristic development.

Figure 1.

Locations of the study areas. The overview map adapted from [35].

2.2. Buzau Carpathians

The Romanian site lies in Buzau County in the south-east of the country, bordering the counties of Brasov, Covasna, Prahova and Vrancea (45°25′18″N, 26°17′46″E, Figure 1). It is situated between the lower Subcarpathians and the higher Carpathians along the Buzau river valley and covers an area of 1,127 km2. The Carpathians rise from 1,300 to 1,772 m, with a relative relief of 500 to 800 m. The mean altitude of the area is 896 m a.s.l., with the geology being represented mainly by deposits of Paleogene flysch. The yearly amount of precipitation in the area is between 630 and 700 mm. Landslides cover large areas in the case study site; in some parts, more than two-thirds of the total area [36]. The urbanization pattern is characterized by long settlements along the main Buzau river valley, also extending to side catchments. The total population of the area is 34,421 inhabitants; Nehoiu (11,355 inhabitants) and Patarlagele (7,831 inhabitants) are the biggest settlements. With a share of up to 40%, agriculture is an important part of the local economy; however, its share of the local and national economy is declining [37]. Subsistence farming evolved at the end of the 19th and the beginning of 20th century and is still important in the area [36]. It has gained importance after the collapse of socialism and the subsequent emergence of small plots following decollectivization [38]. Wood harvesting is another significant activity. The wood is mostly being exported and some used for fuel. Other notable activities in the area are mineral extraction (diatomite) and energy production (a water reservoir in Siriu).

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

For the Italian study area, more data were available than for the Romanian one. For the Italian area, we acquired land use maps for the years 1980 and 2000 [39]. To perform our analysis and to update the land use map for the most recent situation (2010), we used the following data: numeric regional technical maps, orthophoto images (latest for 2011), a 25-m resolution digital elevation model (DEM), erosion and landslide maps, building cadasters, local spatial plans and forest type maps [39]. We obtained municipal and regional socio-economic, agricultural and forestry statistics from the Italian statistics portal [40], from the atlas of mountain communities [21], the agricultural census [41] and the Friuli Venezia Giulia statistical yearbooks [42].

For the Romanian case study area, we acquired Landsat 5 images (path/row 183/28) for 1989 (18 August), 2000 (5 June) and 2010 (12 August) from the United States Geological Survey [43]. We also obtained higher-resolution satellite images for the year 2010 [44]. For some localities (e.g., Nehoiu), we acquired local spatial plans and a detailed topographic map (1:5,000); otherwise, we used the 1:10,000 topographic map, produced in the 1970s. These maps were used to digitize settlements, rivers, water bodies and specific agricultural land (such as orchards). We used a 25-m resolution DEM for Buzau County [45]. Municipal and regional statistics on socio-economic, land use and agricultural and forestry variables were obtained from the Romanian National Institute of Statistics and Buzau county statistics office [46].

The DEMs were resampled to the resolution of the land cover datasets (30 m). From the DEM, we derived the slope and aspect. The ground truth for training and accuracy assessment was primarily mapped from ancillary data: high-resolution orthophoto and satellite images. For the same purpose, we also performed fieldwork in both areas: in March, August and September of 2012 in Italy and July and September 2012, in Romania.

In both areas, there were limitations to the accessibility of the data. The Italian area is affected by the economies in neighboring Slovenia and Carinthia in Austria, as well as Carnia and lowland Friuli in Italy. This is manifested in numerous landowners or farmers managing the area from neighboring regions and, therefore, not covered by accessible data. In the Romanian area, some of the data is incomplete or data from the local level is conflicting with data from the higher (national) level, which we assume is a consequence of the insecure and possibly chaotic institutional conditions in Romania after the year 1990. Furthermore, detailed data on land ownership is not accessible.

3.2. Land Cover Mapping and Classification

The discrepancy in data availability between the case study areas resulted in two different land cover mapping methods. The year 1989 was chosen as a baseline year for both areas in accordance with the stakeholders and to represent the situation before the intense socio-economic changes. For the Italian case study area, we updated existent 1980 and 2000 land use maps to improve the level of detail and to generate the 2010 map, using the above-mentioned ancillary data. All maps were updated by manual digitization and the integration of different datasets (e.g., land use and forest type map) in a GIS [47]. The land use maps were stratified into land cover maps, with a smaller number of classes (7 instead of 15), to enable comparison with the Romanian case study area. For example, different forest types (deciduous, coniferous) were joined to a single forest class, with the same procedure being used for different agricultural, grassland, built up and water classes.

For the Romanian area, we used a semi-automatic land cover classification procedure. First, we generated the most recent land cover map, using the 2010 Landsat image and ancillary data. We started with generating a forest/non-forest map by unsupervised clustering using Iterative Self-Organizing Data Analysis (ISODATA), resulting in 40 clusters. We classified the remaining areas as cultivated, grasslands, bare areas and other vegetation using supervised maximum likelihood classification, where training areas were digitized using visual assessment of satellite images, existing high-resolution data and field data. Urban (built-up) areas, roads and water were digitized manually, with cultivated areas being edited manually, as well, using the information from the census and topographic maps. Subsequently, we merged the individual classification maps (for particular classes). The 2010 map had a small number of clouds, which we masked, and then, later, digitized manually. We applied the same procedure for producing the 1989 land cover. Images were processed, co-registered (automatic tie points) and classified using the ENVI image analysis software [48]. Due to the spatial resolution of Landsat images and the nature of the possible expansion of settlements in this rural area (individual new objects), it was not possible to observe the changes of the settlements. Therefore, settlements, together with water bodies, were masked, as they were assumed to not have changed much in this area, an assumption, backed by municipal land use statistics. Areas where settlement expansion has been observed in the field or identified by stakeholders were digitized manually. The 2000 Landsat image was used to check the validity of the changes between 1989 and 2010 in the case of reforestation. For example, if an area covered by forest in 2010, had not been covered by forest in 2000, we manually edited it and classified it as “other vegetation”, as a forest cannot fully develop in this time. We applied a majority filter of 9 pixels to reduce the noise in the images.

3.3. Land Cover Change Detection and Accuracy Assessment

To analyze the land cover changes, we applied a post-classification comparison of land cover maps between the years 1989 and 2010. By generating difference maps, we were able to identify the major land cover change processes and the level of persistence through a cross-tabulation matrix [49]. After identifying the major land cover change processes in the area, we analyzed them in the context of topographic (slope classes and elevation) and spatial variables (distance to settlements).

We assessed the accuracy and estimated the areas of change, using the procedures for post-classification change analysis accuracy assessment [50]. Assessments in both areas were based on an independent stratified random sample of 9 pixel sample units, visually interpreted using the previously mentioned satellite or orthophoto images. For both areas, we assessed the accuracy of the main observed land cover change categories that are described in the later chapters. We used 325 reference units, with 100 and 75 units for the persistent forest and other areas and 50 units for each remaining change category. In the procedure, we calculated the error-adjusted area of each land cover change category, its 95% confidence interval and the user’s, producer’s and overall accuracy of the change map.

3.4. Identifying Driving Forces of Change

To better understand the reasons and dynamics of land cover changes, as well as the related qualitative socio-economic aspects, we conducted 24 interviews with local and regional experts, stakeholders and researchers from both areas (Table 1). The objective of the interviews was to collect information on demographic, agricultural, forestry, economic, cultural and institutional, proximate and distant driving forces and consequences of land cover change. Interviews were performed in October and November 2012, in Italy, and July and September 2012, in Romania. The interviews were grounded on a review of local, regional and national policy documents on mountains, agriculture, forestry and the environment, as well as relevant scientific literature. The interview protocol included questions on the observed land cover changes, their possible consequences and importance, possible changes to the demography, agriculture, economy and tourism of the areas, the role of decision making on different levels (local, regional, national, etc.) and, also, the possible effects of external driving forces, such as global political changes.

Table 1.

List of interviewees.

| Level | Interviewee | Aspect of Change |

|---|---|---|

| Municipal | Mayor, Vice Mayor (2, I, R) | a, b, d |

| Local historian (2, I, R) | a, b | |

| Forestry technician (3, I, R) | c, e | |

| Spatial planner (2, I, R) | c, d, e | |

| Officer for environmental protection (1, R) | c, e | |

| Technical officer, local emergency or fire department (2, I, R) | e | |

| Farmers (10, R) | b, e | |

| Researchers on human and physical geography (2, I, R) | a, d, e | |

| Regional | Forestry officials (3, I, R) | b, c |

| Geologist (1, I) | c, d | |

| Officials at regional civil protection agency (2, I, R) | e | |

| Officials at regional environmental agency (1, R) | c, e | |

| Researchers on rural economy and land cover change (2, I, R) | a, b, d, e | |

| National | Statistical officials (1, R) | a, b, d |

Notes: I, Italian area; R, Romanian area; a, demographic changes; b, changes to agriculture, forestry; c, environmental (agriculture, forestry, risk) policy; d, economic development; e, consequences of land cover change.

The results of the interviews were used in different ways to describe land cover changes in the analyzed areas. First, they were used to complement accessible socio-economic data and to describe possible interactions between land cover changes and socio-economic changes. Secondly, they were used to explain intangible driving forces or the ones not covered by accessible data, such as changes to policy. Moreover, the results were used to receive information about stakeholders’ perception on land cover changes. This is particularly important when trying to describe the significance of land cover changes. Furthermore, in this way, we were able to identify potential mismatches between our spatial analysis and stakeholders’ knowledge, resulting in improved knowledge on land cover changes in the analyzed areas, as opposed to only analyzing accessible socio-economic data.

4. Results

In the following chapters, we first present the results of our remote sensing analysis: land cover maps and land cover changes since 1989. The results of the interviews follow where observed land cover changes are discussed in relation with socio-economic changes since 1989. Based on both remote sensing analysis and stakeholders’ interviews, we identified seven land cover classes (Table 2) and five conversions (Table 3).

Table 2.

Land cover class definitions.

| Land Cover Class | |

|---|---|

| Urban | Built-up areas (structures, transport network) |

| Cultivated | Arable land and land covered by permanent crops (e.g., orchards) |

| Forest | Densely vegetated areas >1 ha (otherwise, “other vegetation”, as discussed with stakeholders) |

| Grasslands | Natural grasslands, pastures |

| Other vegetation | Riverine vegetation, vegetated area smaller than 1 ha, transitional shrubland |

| Water | Water courses and bodies |

| Bare | Open spaces with no vegetation, rocks, large river beds |

Table 3.

Definitions and assumptions on land cover conversions.

| Conversions | |

|---|---|

| Urban expansion | to built up |

| Reforestation | to forest |

| Deforestation | removal of forest |

| Abandonment | from cultivated to grasslands or “other vegetation” |

| Remaining conversions | All remaining conversions, mostly defined by geomorphologic processes and a consequent increase in bare areas (landslides, scree areas) |

4.1. Land Cover and Land Cover Changes

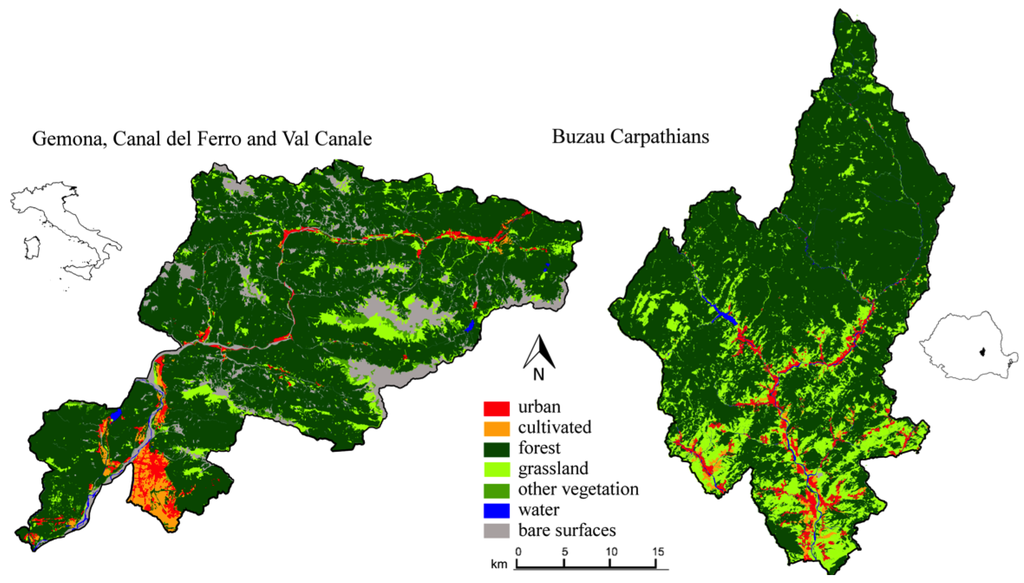

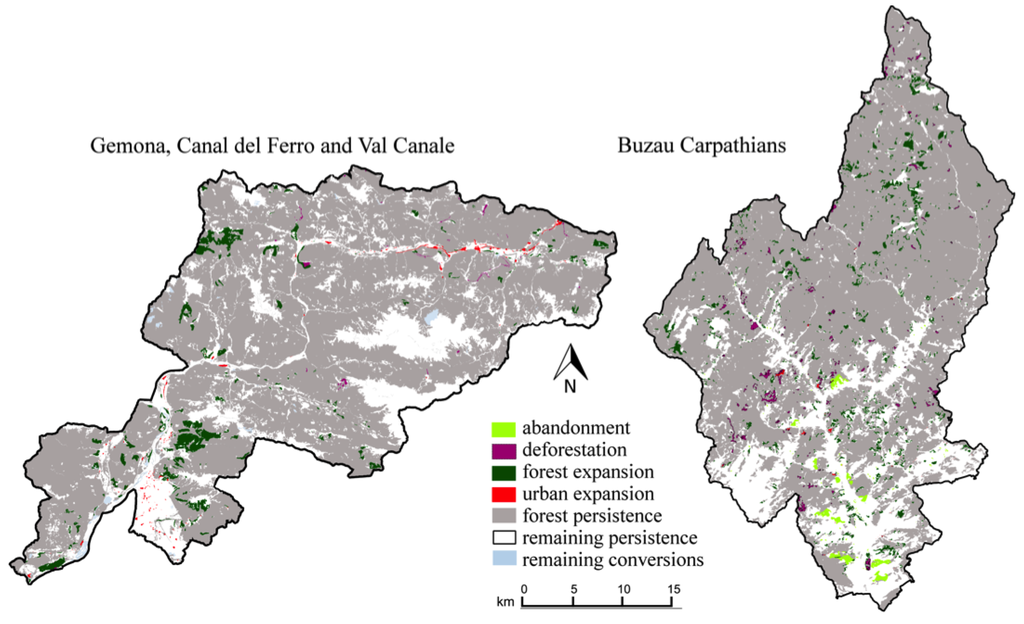

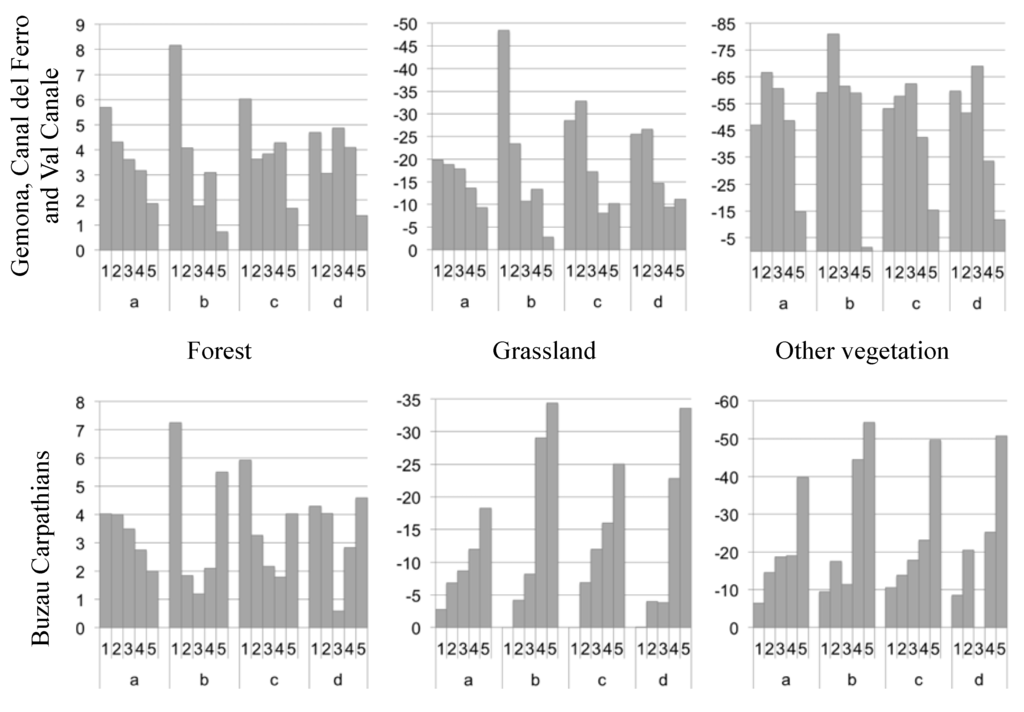

In the Italian area, the plain is characterized by intensively cultivated and urban land. The foothills and slopes are mostly covered by forests, whereas grasslands dominate wider side valleys and areas above the tree line. Urban areas in the narrow Fella valley are present on alluvium fans and confluences of the main and side valleys (Figure 2). In 2010, most of the area was covered by forests (74.7%), bare surfaces (10.3%) and grasslands (8%) (Table 4). In terms of the change in area relative to the initial area of a particular land cover class, the most striking changes between 1989 and 2010 were urban expansion, loss of grassland and loss of “other vegetation” (Table 4). Overall, 3.9% of the area changed since 1989. Neglecting the persistent bare and water areas, 4.4% of the remaining area changed. In terms of the area of a particular conversion relative to the total changed area, by far the biggest change can be attributed to reforestation, followed by urban expansion and deforestation (Table 5, Figure 3). The loss of grasslands on account of forest expansion is comparable with similar areas in the Italian Alps [11]. The expansion of urban areas, however, was rather exceptional, especially when taking into account depopulation and the abandonment of the area, as discussed later. Remaining land cover conversions are 45% defined by geomorphologic processes and a consequence of the increase in bare areas (landslides, scree areas). In terms of the number of patches converted, urban expansion was the major land cover change, whereas the process of reforestation is characterized by the largest mean patch size. The processes of re- and de-forestation show variations in the distribution among the classes of slope, elevation and distance to settlements (Figure 4). There are also variations in the spatial distribution of other land cover changes; e.g., urban expansion occurred mainly in the main valley and in the lowlands (Figure 3). The overall accuracy for the change map is 91.7%, with high estimated accuracies for each land cover change category (Table 6). Nevertheless, the categories of urban expansion and deforestation might have been overestimated, as they are not within the margin of error (at a 95% confidence interval). Furthermore, the area covered by the process of forest expansion is characterized by a large uncertainty, as presented by the wide confidence interval of almost 45% of the adjusted area of forest expansion (Table 6).

Figure 2.

Classified land cover maps of the case study areas for 2010.

In the Romanian case study area, the higher Carpathians are covered by forests with fragments of grasslands. In the lower Subcarpathians, the forest cover is much more fragmented and grasslands prevail in the landscape. The main Buzau river valley is characterized by urban areas and grassland; also, the majority of cultivated land is present in the flood plain (Figure 2). In 2010, forests cover most of the area (75.7%), followed by grasslands (19.4%) and urban areas (3.3%) (Table 4). In terms of the change in area relative to the initial area of a particular land cover class, most changes occurred to cultivated land, followed by “other vegetation” and grasslands. The high rate of abandonment of cultivated land after 1989 (−37.4%, Table 4) is not unusual; similar mountainous areas in Romania witnessed even higher abandonment rates [23]. In relative terms, 4.8% of the whole area has changed (Table 5). Most of the changes can be attributed to reforestation, followed by deforestation and the abandonment of agricultural areas (Figure 3). Re- and de-forestation show some similarities in the distribution among slope classes, however, varying in terms of elevation and distance to settlements (Figure 4). Here, the majority of forest expansions occurred in higher altitudes, a consequence of grassland abandonment in these areas after 1989. Most of the deforestation occurred near the main Buzau valley (Figure 3). The overall accuracy of the change map is 89.2%. Despite being characterized by a high level of accuracy, the adjusted areas of forest expansion, deforestation and abandonment are associated with high uncertainties, as reflected by the wide margins of error. Taking into account these uncertainties, forest expansion could be between 2,714.8 and 5,247.8 ha, deforestation between 610.8 and 1,329 ha and abandonment between 516.7 and 928.7 ha (Table 6). Moreover, due to the lack of high-detail multi-temporal data and the nature of the data used (the spatial and temporal resolution of Landsat), our results might not take into account all land cover processes in the area. We suspect that some possibly substantial small-scale deforestation went unaccounted for. Furthermore, estimations of land abandonment could be problematic, as it is difficult to differentiate among particular land cover classes, e.g., between cultivated areas and grassland or bare areas.

Table 4.

Comparison of land cover changes in both case study areas. Changes are expressed as overall increases or decreases in the percent of areas covered by the particular land cover type (net changes). Swaps are defined as the total percent of pixels that have changed from or to the particular land cover type, ignoring the persistent areas of the land cover type (100% of persistent areas). The concept of swapping is being used to show the dynamics of each particular land cover class, more precisely, the amount of both gains and losses it has experienced. Therefore, it is not only focusing on net changes, but also describing the extent of possible change trends opposing the main trend of a net increase or decrease.

| Class | Gemona, Canal del Ferro and Val Canale | Buzau Carpathians | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land Cover (km2) | Land Cover Change (%) | Land Cover (km2) | Land Cover Change (%) | |||||

| 1989 | 2010 | Change | Swaps | 1989 | 2010 | Change | Swaps | |

| Urban | 23.9 | 27.4 | 14.9 | 0 | 36.7 | 37.5 | 2.1 | 0 |

| Cultivated | 27.7 | 26.9 | −2.9 | 6.1 | 17.2 | 10.8 | −37.4 | 37.4 |

| Forest | 829.8 | 857.8 | 3.4 | 0.3 | 818.4 | 840.9 | 2.8 | 1.4 |

| Grassland | 119.5 | 92.5 | −22.6 | 25.8 | 234.7 | 218.9 | −6.7 | 13.9 |

| Other vegetation | 24.7 | 20.4 | −17.4 | 23.1 | 8.7 | 7.8 | −9.9 | 22 |

| Water | 3.9 | 3.9 | ~0 | 0 | 11.1 | 11.1 | ~0 | 0 |

| Bare surfaces | 118.9 | 119.6 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ~0 | ~0 |

Table 5.

Major land cover conversions (%).

| Conversion | Gemona, Canal del Ferro and Val Canale | Buzau Carpathians | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion (%) | No. of Patches | Mean Patch Size (ha) | Proportion (%) | No. of Patches | Mean Patch Size (ha) | |

| Total conversion | 3.9/4.4 a (44.6 km2) | 907 | 4.9 | 4.8 (52.8 km2) | 1527 | 3.5 |

| Urban expansion | 8.1 | 258 | 1.4 | 0.1 | b | b |

| Reforestation | 72.5 | 227 | 14.3 | 64.3 | 838 | 4.1 |

| Deforestation | 5.8 | 75 | 1.5 | 21.9 | 332 | 2.8 |

| Abandonment | 0.8 | b | b | 13.5 | 142 | 5.0 |

| Remaining | 12.8 | 347 | 3.2 | 0.2 | 215 | 1.0 |

Notes: a, neglecting the persistent water and bare surfaces; b, few conversions were observed, either due to the spatial resolution of the data or the spatial scale of the process, and are counted in the “remaining” conversions.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of land cover conversions between 1989 and 2010. See Table 4 for the conversion definition and Table 6 for the estimations of the accuracy and areas. Remaining persistence and conversion present land cover persistence or conversion other than described by abandonment, deforestation, forest and urban expansion and forest persistence.

Table 6.

Accuracy assessment and estimation of areas with a margin of error at a 95% confidence interval for both land cover change maps (Figure 3). CI, confidence interval.

| Change category | Classified Area (ha) | Adjusted Area (ha) | 95% CI (ha) | 95% CI (%) | User’s Accuracy (%) | Producer’s Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemona, Canal del Ferro and Val Canale | ||||||

| Rem. persistence | 27,784.9 | 29,930.8 | 3,570.0 | 11.9 | 96.0 | 81.8 |

| Forest persistence | 81,442.1 | 79,977.6 | 4,020.9 | 5.0 | 95.0 | 91.3 |

| Forest expansion | 3,234.3 | 3,736.8 | 1,674.2 | 44.8 | 88.0 | 97.8 |

| Deforestation | 112.5 | 99.0 | 10.5 | 10.6 | 88.0 | 95.7 |

| Urban expansion | 350.2 | 309.8 | 21.2 | 6.8 | 86.0 | 100.0 |

| Buzau Carpathians | ||||||

| Rem. persistence | 26,657.6 | 27,712.7 | 3,664.2 | 13.2 | 90.7 | 84.0 |

| Forest persistence | 80,678.9 | 78,884.0 | 3,413.5 | 4.3 | 96.0 | 92.3 |

| Forest expansion | 3,435.8 | 3,981.3 | 1,266.5 | 31.8 | 84.0 | 85.7 |

| Deforestation | 1,085.0 | 970.0 | 359.2 | 37.0 | 86.0 | 93.5 |

| Abandonment | 715.0 | 722.7 | 206.0 | 28.5 | 82.0 | 95.3 |

Figure 4.

Summary of major land cover changes in quintile classes of slope (a), elevation (b) and distance to settlements (c) and roads (d). The charts present the percentage of forest, grassland and other vegetation classes that changed (increased or decreased).

4.2. Socio-Economic Changes

Both areas experienced significant socio-economic changes in the last 20 years (Table 7). The demographic changes in both areas are characterized by a substantial decrease in population and an increase in the population-aging index. Furthermore, both witnessed a substantial decrease in agricultural activities, portrayed both by a decrease in employment in the sector, as well as in the number of livestock, especially sheep and goats. The decrease in sheep and goat populations in the analyzed areas since 1990 is around 40% above the average 23% decrease in the European Union [51].

The Italian area used to be more commercially and strategically important due to its border location and had numerous customs, commercial and military zones. A significant part of its trade and transport activities diminished after the collapse of Yugoslavia in the year 1991 and even more after the entry of Austria and, later, Slovenia to the European Union, with the introduction of the Schengen regime. The majority of the army was withdrawn from the area, and commercial and customs zones were abandoned, accompanied by a breakdown of the local industry and mining activities. The area lost its role as an important trade and employment center in the wider region, even though it became better connected with the European highway and railroad network. Tourism activities, on the other side, witnessed an increase, as tourism became a more important part of the local economy. Even though wood processing witnessed an increase of activity in the area, forest harvesting declined by a third and is well below the allowed amount of forest harvesting.

Table 7.

Socio-economic changes in the areas since 1989.

| Change | Gemona, Canal del Ferro and Val Canale a | Buzau Carpathians b |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Depopulation: −9.6% of whole area, −31% Pontebba, −21% Tarvisio, −17% Resia. | Depopulation: −12.4% of whole area, −18% Gura Teghii, −17% Panatau. |

| Aging index c | 151.2 in 1990; 216.3 in 2010. | 79.9 in 1990; 143.7 in 2010. |

| Agricultural activities | −36.6% of cattle, −39.2 of sheep and goats, −69.8% of farming associations, −26.5 of employees in agriculture d. | −4.3% of cattle, −39.7% of sheep and goats, −12% of orchards, −32% of employees in agriculture and forestry. The collapse of agricultural associations and the emergence of subsistence farming (small fields and gardens). |

| Forestry activities | Wood harvest: −33% (currently 15%–20% of the annual increment) e. Employment in wood processing industry: +8.2%. Forest managed by state owned forestry associations. | Wood harvest: +23% (currently around 45% of the annual increment and rising). Employment in wood processing industry: −66%. The emergence of private forestry associations. The end of the governmental reforestation program: annually 400–600 ha reforested before 1989 e. |

| Industry and commerce | Employment: −12% in trade, −21% in transport, storage and communications, −73% in mineral extraction. | Employment: −39% in industry, −53% in mineral extraction. |

| Tourism | 0.5% increase in employees. Substantial expansion of tourism and recreation areas and an increase of overnights. Organization of the Winter Universiade in 2003. | −33% of employees. Individual tourist accommodations and a decrease in overnights. |

| Infrastructure | After 1989, completion of the infrastructural corridor: highway, high-speed railroad, high-voltage power line and gas pipeline. | After 1989, neglected by governmental infrastructural plans. Regular reconstruction of national road and railroad due to landslides. |

| Other | Withdrawal of army from the area after 1991. | Land restitution reforms: before 1989, nearly 100% of forests state owned. After the reforms, land returned to its former owners, resulting in 34.7% of forests in private ownership in 2011 f |

Notes: a, all statistics, collected on a municipal level from [40], if not stated otherwise; b, all statistics, collected on a municipal level from [46], if not stated otherwise; c, (population over 64/population under 15) × 100; d, [41]; e, forestry officials, regional data; f, agricultural officials.

The Romanian area witnessed socio-economic changes similar to the whole Carpathian region after the fall of communism: the fall of large-scale collective agricultural associations, the emergence of new land use policies and land ownership reforms, resulting in numerous new land owners [52,53]. Until the end of the 1980s, the area was subject to several governmental development and infrastructural plans. Examples of these are the water reservoir near Siriu in the northwest of the area, built for flood regulation, water storage for irrigation and energy production, and the reforestation plans, with the aim of reforesting the slopes in this landslide prone area and ensuring steady economic benefits from the forests. Since the 1990s, Romania has been expanding its traffic (motorways) and energy infrastructure; however, this area has been neglected by these plans. Furthermore, since 1989, the area has witnessed a collapse of industry, mineral extraction and wood processing activities, on one side, and a rapid increase in wood harvesting, on the other.

4.3. Stakeholders’ Perception of Land Cover Changes

In the Italian area, the results of the stakeholders’ interviews were consistent with the findings of land cover mapping and classification (Table 8). Due to the multiple direct and indirect effects on the local economy, demography and land cover, the majority of stakeholders recognized as the most important change the completion of the infrastructural corridor through the valley, i.e., the highway, high-speed railroad, high-voltage power line and gas pipeline. For stakeholders at the regional level, the second most significant change was the expansion of forests. Stakeholders from the municipal level described a wide variety of significant changes, i.e., the expansion of settlements and recreational and sports facilities. The municipal authorities emphasized that before the legislation on risk zoning (law 267/1998, which clearly identified building constraints depending on risk levels), settlement expansion occurred also in areas at high risk of landslides, debris flows and flash floods. In fact, high risk areas, where houses were built before the law enforcement, experienced catastrophic consequences in terms of human casualties and financial damages in 2003 when several municipalities of the area were affected by numerous flash floods [34]. Besides the aspect of increased risk, settlement and infrastructural expansion changed the alpine landscape, as mentioned by researcher in the rural economy:

Table 8.

Summary of stakeholders’ perception of land cover changes in both areas.

| Gemona, Canal del Ferro and Val Canale | Buzau Carpathians | |

|---|---|---|

| Stakeholders’ Observations | ||

| Major changes observed | Forest and urban expansion | Urban expansion |

| Possible causes identified | Forest expansion follows a long-term trend of agricultural abandonment, whereas urban expansion was caused by promoting economic activities, real estate investment and demand for secondary housing | Rapid economic development of Romania in the last 20 years, the increase in the well-being of the population and the demand for more housing and enterprise areas; chaotic dispersal as a result of legislative difficulties in the transition era |

| Perception of land cover changes | Associated with negative consequences due to landscape degradation and increased hydro-meteorological risk | Mostly positive, as the changes went hand-in-hand with economic development; recognized the increase in the hydro-meteorological risk |

| Researchers’ Observations | ||

| Major changes observed | Forest and urban expansion | Forest expansion and deforestation |

| Comment on perceived changes | Stakeholders’ observations in line with data | Stakeholders mostly think that land cover changes observed by the researchers are not that significant, as they compare the region to other Romanian regions, where similar changes happened on a larger scale |

| Perception of the consequences of land cover changes | Stakeholders’ mostly aware of possible consequences of land cover changes | Stakeholders’ minimize the possible negative consequences of deforestation, such as increased erosion and changes to landslide occurrence. They are aware of a possible higher risk, due to the increase in the value and number of the elements of risk |

“New infrastructure, together with the abandonment of the old one (mostly still present) caused severe degradation of the alpine landscape of the area. Some parts of the valley, like near Pontebba, are almost devastated due to the dense network of infrastructure.”

In the Romanian area, a few of the involved stakeholders identified deforestation among the most important land cover processes, as was revealed by our spatial data analysis (see Section 4.1 and Table 5). A usual explanation of the perceived irrelevance of this process was that the neighboring regions were more affected by it. As the rates and spatial pattern of deforestation after land ownership reforms in Romania vary in different regions [23,30,31], the process in Buzau County might be considered moderate by comparison. As reported by a representative of a privately owned forestry association:

“Most illegal wood harvesting activities do not occur in the form of clear cuttings, with the majority of the clear cuts occurring in privately owned forests. Compared to other Romanian regions, large scale clear cuts have not reached alarming levels and mostly occur in the form of smaller patches.”

Instead, the majority of stakeholders in Romania identified the increase of urban areas as most important, even though, in quantitative terms, our analysis observed it as relatively minor. This might be explained by their own focus on the process of obtaining building permits and dealing with the increasing demands of residents and investors, after Romania’s entry into the European Union. As reported by one of the interviewees:

“Most of our time in the last 10 years has been spent on enabling the increase of economic activities and the well-being of the population. Expansion of urban areas was a consequence of this. I consider these changes as positive and most important, even though they might have some negative consequences. These changes have led to more funds for the local authorities, enabling the development of new activities.”(Spatial planner)

Table 9 summarizes the results emerging from these discussions with local stakeholders in a qualitative way. The aim of the table is to capture, in relatively simple and immediate terms, the variability of land cover processes resulting from long- versus short-term trends. We identified the perceived position intuitively without quantitative evaluation. As “short-term”, we define conversions that were influenced mostly by recent socio-economic changes, while “long-term” refers to conversions following a trajectory specific for the case study for a longer time period than was analyzed.

At first glance, conversions in Romania are predominately due to recent events, or classified as “short-term” (Table 9), with the exception of “reforestation”, which has a longer history than the other conversions, which were mostly spiked by the end of the communist regime in 1989. Most conversion trends in Italy have a longer history, with the exception of urbanization. Further stakeholder views together with why urbanization may be occurring despite factors otherwise indicating economic decline (see Table 7) will be discussed below.

Table 9.

Land cover changes as defined as short- or long-term processes. This qualitative evaluation is based on the results of stakeholders’ interviews. Short-term changes were influenced mostly by recent socio-economic changes, whereas long-term ones describe changes specific for the case study for a longer time period than was analyzed.

| Land Cover Conversion | Gemona, Canal del Ferro and Val Canale | Buzau Carpathians |

|---|---|---|

| Urban expansion | Short-term | Medium to long-term |

| Reforestation | Long-term | Medium-term |

| Deforestation | Medium to long-term | Short-term |

| Land abandonment | Long-term | Short-term |

5. Discussion

Drastic socio-economic changes since 1989 have had a significant effect on land cover changes in both areas. Even though the processes differ in spatial and relative terms between both case study areas, we could observe some surprising land cover processes, when relating them to socio-economic trends, especially depopulation in both areas. Examples of that are the significant increases of human influences in the form of urban expansion in Italy and deforestation in Romania. Further reasons behind these processes are discussed in this section.

Despite the decline in population and economic activities, a notable expansion of the urban land cover occurred in the Italian case study area. This can be associated with an increase in infrastructural and real estate development since the end of the 1980s. Three factors worked together to result in urban expansion: policy-makers encouraging real estate building to promote economic activity and wellbeing in the area, people building real estate as a form of investment and people building secondary homes due to the region’s recreational and aesthetic value. In our area, all three factors were at work, while the last one, encouragement by policy-makers and real estate as investment, seem to have been dominant. As one interviewee stated:

“Policy-makers in the last few decades promoted construction, due to its influence on other economic activities, and saw it as a way to increase the living standard. Construction firms were engaging in housing and infrastructure projects, resulting in a large number of empty objects and possibly over-dimensioned infrastructure. Moreover, the emergence of secondary homes did not occur solely due to the attractive landscape in the area, but also as it was endorsed as a good way to save money through real estate.”(Researcher in human geography)

Two other changes in the Italian site are more intuitively consistent with the decline of population and economic activity: land abandonment and reforestation. Both started after the Second World War, starting at the higher elevation areas: until 1989 most of the grassland areas at higher elevations had already been reforested, resulting in the doubling of the forest cover since 1950, as explained by the forestry officials.

At the same time, we identified deforestation as a minor land cover change process in the Italian area. According to our spatial analysis, 63.2% of this deforestation was due to the expansion of recreational areas (ski resorts) or energy infrastructure (gas pipelines, high voltage power lines), which occurred after 1989. Therefore, we attributed deforestation partly to the changes in the last 20 years.

In the Romanian area, the majority of land cover changes can be attributed to the sudden political changes and the consequent socio-economic and legislative difficulties. For example, after 1989, Romania introduced three land ownership reforms, where previously seized land is returned, with the 247/2005 restitution law being the latest [37]. Whereas most of the agricultural land is now under private ownership, the majority of the forest is still owned by the government (Table 7). As the following quote implies, ownership changes are among the most significant causes of deforestation:

“The Romanian forest code itself promotes sustainable forestry. The difficulties in its implementation and insufficient monitoring, together with the interplay between unemployment, poverty and chaotic land ownership legislation (three different reforms), lead to illegal logging.”(Private forestry official)

Remaining land cover processes, such as land abandonment and consequential reforestation, are associated with the collapse of former agricultural associations, the evident decline of agricultural activities and the fragmented new land ownership pattern (Table 7). This made the management of the existent agricultural land nearly impossible, resulting in land abandonment and reforestation. On the other hand, the emergence of subsistence farms increased the pressure on slopes. This phenomenon, basically unknown to most European mountain areas, has been identified in the field, as the scale of the process (individual gardens and fields) prevents it from being identified by accessible data. Nevertheless, it is significant, as the potential side effects of steep slope farming are known to be severe (soil erosion, increased hazard occurrence) [54].

In both areas, the most extensive land cover change process was reforestation. It is well recognized in societies that experience economic development with urbanization and industrialization [55,56] and typical for European mountain areas. As summarized in Table 9, land cover change processes in Italy (except for urban expansion) were mostly following long-term trends, as opposed to Romania, where most of the processes can be attributed to socio-economic changes in the last 20 years, i.e., what we consider short term. Interviewees in both areas agreed that it is difficult to cope with and manage external influences. What is more, they argued that external influences are the prevailing cause behind the negative consequences of land cover change (e.g., landscape degradation, increased risk).

Furthermore, for both study areas, the proportion of the area that changed (below 5%) might seem unimportant. Pontius et al. [49], however, noted that scientists should resist indicating the importance of land use/cover change processes solely due to their statistical importance. Therefore, we argue that the observed land cover changes are significant, when putting them into the context of changes to ecosystem services provisioning and the short analyzed time frame of a little over 20 years. Both case study areas are defined by complex physical-geographic characteristics, where deforestation and settlement expansion could have led to soil erosion and the increased occurrence or consequences of hydro-meteorological hazards, Moreover, land abandonment and forest expansion can have a significant effect on the landscape image and biodiversity of the areas.

This study has shown how a brief analysis of land cover change might lead to ignoring processes of land cover change, which occur on a smaller spatial extent, that, however, have significant consequences. Furthermore, while some processes (e.g., forest expansion) might be following a long-term trend typical for European mountain areas, others might be experiencing a rapid change that can be attributed solely to the context of the case study area. We demonstrated how necessary it is to recognize these particular processes of land cover change and to try to identify the possible driving forces behind them. Overall driving forces, such as depopulation and general economic development, are not enough to describe land cover changes, as they might result in contrasting and unanticipated results. Other driving forces, such as external investors (in real estate), political decisions on the national level (infrastructural projects), changes to policy (land ownership, forest management) and the uncertainty connected with all these driving forces might prevail, especially in a time of transition. What is more, these external driving forces are beyond the abilities of local decision makers to cope with the pressures to the land cover. This is especially important in mountain areas, as they have to deal with the possible negative consequences of these changes, for example, in the form of increased risk or degradation of the landscape.

6. Conclusions

Socio-economic changes in Europe after the end of the 1980s resulted in a variety of land cover changes in the Alps and the Carpathians. In relative terms, the most widespread land cover process in both of the analyzed mountain areas was the expansion of forest cover. The spatial and temporal rate of this long-term process is similar to most European mountain areas. This process goes along with the loss of important habitats for biodiversity, such as grasslands, and changes in traditional forms of agriculture, such as sheep and goat pastures.

Other observed land cover changes show how local processes differ from general trends. The Eastern Italian Alps area witnessed a substantial expansion of urban areas, among others, due to secondary housing, tourism and traffic infrastructure. In the Romanian Carpathians, deforestation was identified as one of the most significant land cover change processes. Results in both areas pose new questions on the possible increase of risk to hydro-meteorological hazards due to the observed land cover changes. Another important potential consequence to the land cover changes includes soil degradation due to erosion.

The complex relationship between socio-economic changes as driving forces, and land cover changes as a consequence, is difficult to describe and analyze. Therefore, different types of data and methods, i.e., quantitative remote sensing analysis and qualitative interviews, have been used and integrated. In this way, we were able to portray a broader picture of land cover changes in a time of intense socio-economic changes. The revealed mismatches between stakeholders’ perceptions and the results of spatial data analysis represent an added value to the spatial research results, particularly in answering the possible causes behind land cover changes and in understanding the importance of particular changes that seem relatively small, as, for example, in the Romanian site.

It is a continuing challenge in studies of local land cover changes and socio-economic transitions to integrate all observations, in order to understand the driving forces of land cover changes in a more comprehensive and systematic way. From our experiences in both study areas, we suspect that a continuous, long-term and inclusive transdisciplinary process may best help define scientific questions and support politicians and decision makers in understanding and managing the expected land cover changes in European mountain areas.

Acknowledgments

This work is a part of the CHANGES project (Changing Hydro-meteorological Risks, As Analyzed by a New Generation of European Scientists), a Marie Curie Initial Training Network, funded by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme, FP7/2007–2013, under Grant Agreement No. 263953. We would also like to thank two anonymous referees for their comments on this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Žiga Malek was involved in all stages of the research: data gathering and interpretation, field visits, land cover classification, GIS and statistical analysis, performing the majority of interviews. Anna Scolobig was involved in data gathering, design of the interview protocol, performing interviews, stakeholder perception analysis and socio-economic data interpretation. Dagmar Schröter was involved in the design of interview protocol, stakeholder perception analysis and socio-economic data interpretation. All authors were involved in the design of the research and writing of the report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Olsson, E.G.A.; Austrheim, G.; Grenne, S.N. Landscape change patterns in mountains, land use and environmental diversity, Mid-Norway 1960–1993. Landsc. Ecol. 2000, 15, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioffe, G.; Nefedova, T.; Zaslavsky, I. From spatial continuity to fragmentation: The case of russian farming. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2004, 94, 913–943. [Google Scholar]

- Bičı́k, I.; Jeleček, L.; Štěpánek, V. Land-use changes and their social driving forces in Czechia in the 19th and 20th centuries. Land Use Policy 2001, 18, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irland, L.C. State failure, corruption, and warfare: Challenges for forest policy. J. Sustain. For. 2008, 27, 189–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, D.; Crabtree, J.; Wiesinger, G.; Dax, T.; Stamou, N.; Fleury, P.; Gutierrez Lazpita, J.; Gibon, A. Agricultural abandonment in mountain areas of Europe: Environmental consequences and policy response. J. Environ. Manag. 2000, 59, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, C.; Spehn, E.; Baron, J.; Ohsawa, M. Mountain Systems. In Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Current State and Trends: Findings of the Condition and Trends Working Group of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 681–716. [Google Scholar]

- Tasser, E.; Walde, J.; Tappeiner, U.; Teutsch, A.; Noggler, W. Land-use changes and natural reforestation in the Eastern Central Alps. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 118, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasser, E.; Mader, M.; Tappeiner, U. Effects of land use in alpine grasslands on the probability of landslides. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2003, 4, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glade, T. Landslide occurrence as a response to land use change: A review of evidence from New Zealand. Catena 2003, 51, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemini, C.; Rizzoli, A. Land use change and biodiversity conservation in the Alps. J. Mt. Ecol. 2003, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Giupponi, C.; Ramanzin, M.; Sturaro, E.; Fuser, S. Climate and land use changes, biodiversity and agri-environmental measures in the Belluno province, Italy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2006, 9, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneeberger, N.; Bürgi, M.; Hersperger, A.M.; Ewald, K.C. Driving forces and rates of landscape change as a promising combination for landscape change research—An application on the northern fringe of the Swiss Alps. Land Use Policy 2007, 24, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Geist, H. Land-Use and Land-Cover Change: Local Processes and Global Impacts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kräuchi, N.; Brang, P.; Schönenberger, W. Forests of mountainous regions: Gaps in knowledge and research needs. For. Ecol. Manag. 2000, 132, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremene, C.; Groza, G.; Rakosy, L.; Schileyko, A.A.; Baur, A.; Erhardt, A.; Baur, B. Alterations of steppe-like grasslands in Eastern Europe: A threat to regional biodiversity hotspots. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 1606–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bätzing, W. Die Alpen: Geschichte und Zukunft Einer Europäischen Kulturlandschaft; C.H.Beck: München, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Erdeli, G.; Dinca, A.I. Tourism—A vulnerable strength in the protected areas of the Romanian Carpathians. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 19, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Valle, E.; Lamedica, S.; Pilli, R.; Anfodillo, T. Land use change and forest carbon sink assessment in an alpine mountain area of the Veneto region (Northeast Italy). Mt. Res. Dev. 2009, 29, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocca, G.; Sturaro, E.; Gallo, L.; Ramanzin, M. Is the abandonment of traditional livestock farming systems the main driver of mountain landscape change in Alpine areas? Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, O.; Borsdorf, A.; Fischer, A.; Stotter, J. Mountains Under Climate and Global Change Conditions—Research Results in the Alps. In Climate Change—Geophysical Foundations and Ecological Effects; Blanco, J.A., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nazionale della Montagna. Atlante Statistico Della Montagna Italiana. Statistical Atlas of Italian Mountains; Bononia University Press: Bologna, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Turnock, D. Ecoregion-based conservation in the Carpathians and the land-use implications. Land Use Policy 2002, 19, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuemmerle, T.; Müller, D.; Griffiths, P.; Rusu, M. Land use change in Southern Romania after the collapse of socialism. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2008, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, D.; Kuemmerle, T.; Rusu, M.; Griffiths, P. Lost in transition: Determinants of post-socialist cropland abandonment in Romania. J. Land Use Sci. 2009, 4, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taff, G.N.; Müller, D.; Kuemmerle, T.; Ozdeneral, E.; Walsh, S.J. Reforestation in Central and Eastern Europe After the Breakdown of Socialism. In Reforesting Landscapes; Nagendra, H., Southworth, J., Eds.; Springer-Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 10, pp. 121–147. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, M.; Kuemmerle, T.; Elbakidze, M.; Ozdogan, M.; Radeloff, V.C.; Keuler, N.S.; Prishchepov, A.V.; Kruhlov, I.; Hostert, P. Patterns and drivers of post-socialist farmland abandonment in Western Ukraine. Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, J.; Estreguil, C.; Vogt, P. Forest cover and pattern changes in the Carpathians over the last decades. Eur. J. For. Res. 2007, 126, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuemmerle, T.; Hostert, P.; Radeloff, V.C.; Perzanowski, K.; Kruhlov, I. Post-socialist forest disturbance in the Carpathian border region of Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine. Ecol. Appl. 2007, 17, 1279–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuemmerle, T.; Chaskovskyy, O.; Knorn, J.; Radeloff, V.C.; Kruhlov, I.; Keeton, W.S.; Hostert, P. Forest cover change and illegal logging in the Ukrainian Carpathians in the transition period from 1988 to 2007. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 1194–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Kuemmerle, T.; Kennedy, R.E.; Abrudan, I.V.; Knorn, J.; Hostert, P. Using annual time-series of Landsat images to assess the effects of forest restitution in post-socialist Romania. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 118, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorn, J.; Kuemmerle, T.; Radeloff, V.C.; Keeton, W.S.; Gancz, V.; Biriş, I.A.; Svoboda, M.; Griffiths, P.; Hagatis, A.; Hostert, P. Continued loss of temperate old-growth forests in the Romanian Carpathians despite an increasing protected area network. Environ. Conserv. 2012, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Knorn, J.; Kuemmerle, T.; Radeloff, V.C.; Szabo, A.; Mindrescu, M.; Keeton, W.S.; Abrudan, I.; Griffiths, P.; Gancz, V.; Hostert, P. Forest restitution and protected area effectiveness in post-socialist Romania. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 146, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangati, M. Flash Flood Analysis and Modelling in Mountain Regions. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Padova, Padova, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Borga, M.; Boscolo, P.; Zanon, F.; Sangati, M. Hydrometeorological analysis of the 29 August 2003 flash flood in the eastern Italian Alps. J. Hydrometeorol. 2007, 8, 1049–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, A.; Reuter, H.I.; Nelson, A.; Guevara, E. Hole-Filled Seamless SRTM Data V4. International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). Available online: http://srtm.csi.cgiar.org (accessed on 11 November 2013).

- Muică, N.; Turnock, D. A toponomical approach to the agrarian history of the pătârlagele depression (Buzău Subcarpathians, România). Hum. Geogr. 2008, 2, 928–949. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of Romania. Programul Naţional de Dezvoltare Rurală 2007–2013; Government of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2012.

- Bălteanu, D.; Popovici, E.A. Land use changes and land degradation in post-socialist Romania. Romanian J. Geogr. 2010, 54, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Regione, F.V.G. Catalog of Territorial and Environmental Data of the Autonomous Region Friuli Venezia Giulia. Available online: http://irdat.regione.fvg.it/WebGIS/ (accessed on 20 January 2012).

- Instituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT). Italian National Institute for Statistics Data Warehouse. Available online: http://dati.istat.it/ (accessed on 19 April 2012).

- Instituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT). Censimento Generale dell’Agricoltura. Italian Agricultural Census. Available online: http://dati-censimentoagricoltura.istat.it (accessed on 19 April 2012).

- Autonomous Region of Friuli Venezia Giulia. Statistics of the Autonomous Region of Friuli Venezia Giulia. Available online: http://www.regione.fvg.it/rafvg/cms/RAFVG/ (accessed on 20 April 2012).

- US Geological Survey (USGS). Earth Explorer. Available online: http://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 18 January 2013).

- Google Earth 7.0 Nehoiu, Romania. 45°25′18″N, 26°17′46″E. Digital Globe 2012. Available online: http://earth.google.com/ (accessed on15 September 2012).

- Romanian Academy, Institute for Geography (IGAR). Digital Elevation Model for Buzau County; IGAR: Bucharest, Romania, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Institutul National de Statistica (INSSE). Romanian National Institute of Statistics Data Portal. Available online: http://www.insse.ro/ (accessed on 11 May 2012).

- Quantum GIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. 2012. Available online: http://www.qgis.org (accessed on 10 January 2013).

- Exelis ENVI; Exelis Visual Information Solutions: Boulder, CO, USA, 2012.

- Pontius, R.G., Jr.; Shusas, E.; McEachern, M. Detecting important categorical land changes while accounting for persistence. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 101, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P.; Foody, G.M.; Stehman, S.V.; Woodcock, C.E. Making better use of accuracy data in land change studies: Estimating accuracy and area and quantifying uncertainty using stratified estimation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 129, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataide Dias, R.; Mahon, G.; Dore, G. EU Sheep and Goat Population in December 2007 and Production Forecasts for 2008; Eurostat Publication No. 67; European Comission, Eurostat: Luxemburg, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mathijs, E.; Swinnen, J.F.M. The economics of agricultural decollectivization in East Central Europe and the former Soviet Union. Econ.Dev. Cult. Chang. 1998, 47, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lerman, Z.; Csaki, C.; Feder, G. Evolving farm structures and land use patterns in former socialist countries. Quart. J. Int. Agric. 2004, 43, 309–336. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, R. Soil degradation by erosion. Land Degrad. Dev. 2001, 12, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, A. The Transition from Deforestation to Reforestation in Europe. In Agricultural Technologies and Tropical Deforestation; Angelsen, A., Kaimowitz, D., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2001; pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rudel, T.K.; Coomes, O.T.; Moran, E.; Achard, F.; Angelsen, A.; Xu, J.; Lambin, E. Forest transitions: Towards a global understanding of land use change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2005, 15, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).