Compensation and Resettlement Policies after Compulsory Land Acquisition for Hydropower Development in Vietnam: Policy and Practice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Analytical Framework

3. Research Design and Methodology

3.1. Research Problem

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3.2.1. Primary Data

3.2.2. Limitation of Research

4. Results and discusions

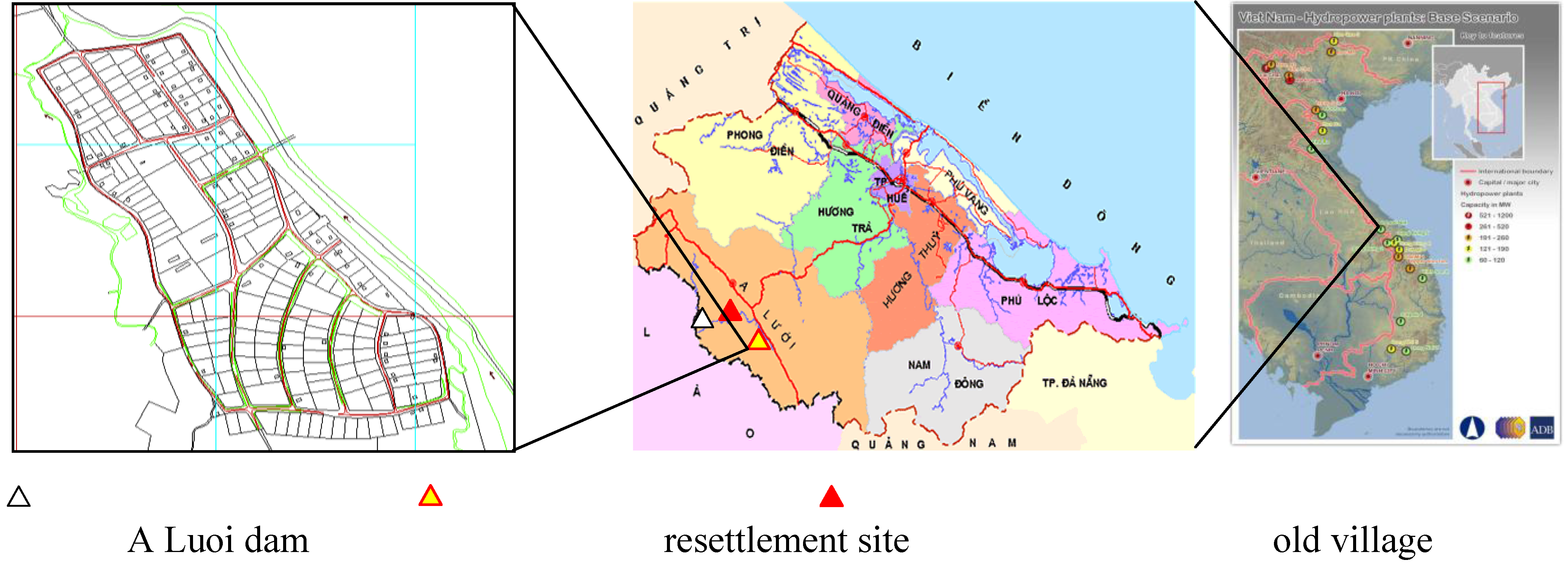

4.1. Study Site and Historical of Displaced People

| # of Respondents | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity of interviewees | Ta Oi | 58 | 96.7 |

| Kinh | 2 | 3.3 | |

| Gender of interviewees | Male | 24 | 40.0 |

| Female | 36 | 60.0 | |

| Education level of interviewees | Illiterate | 20 | 33.3 |

| Primary | 14 | 23.3 | |

| Secondary | 19 | 31.7 | |

| High school | 7 | 11.7 | |

| Occupation of interviewees | Unemployed | 9 | 15 |

| Farmer | 42 | 70 | |

| Carpenter | 2 | 3.3 | |

| Government official | 7 | 11.7 | |

| Economic status of households | Non-poor | 34 | 56.7 |

| Poor | 26 | 43.3 | |

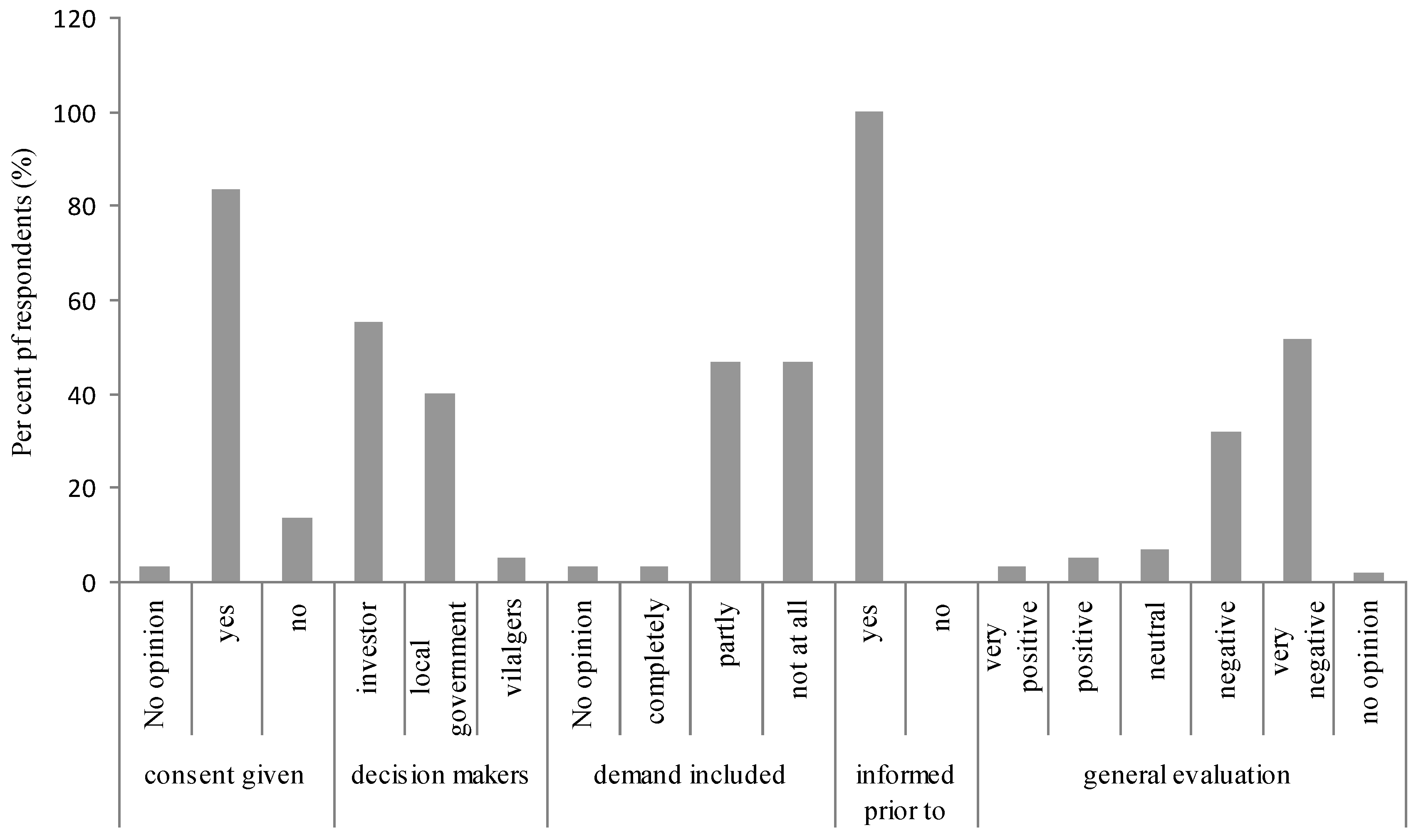

4.2. The Investment and Land Acquisition Process

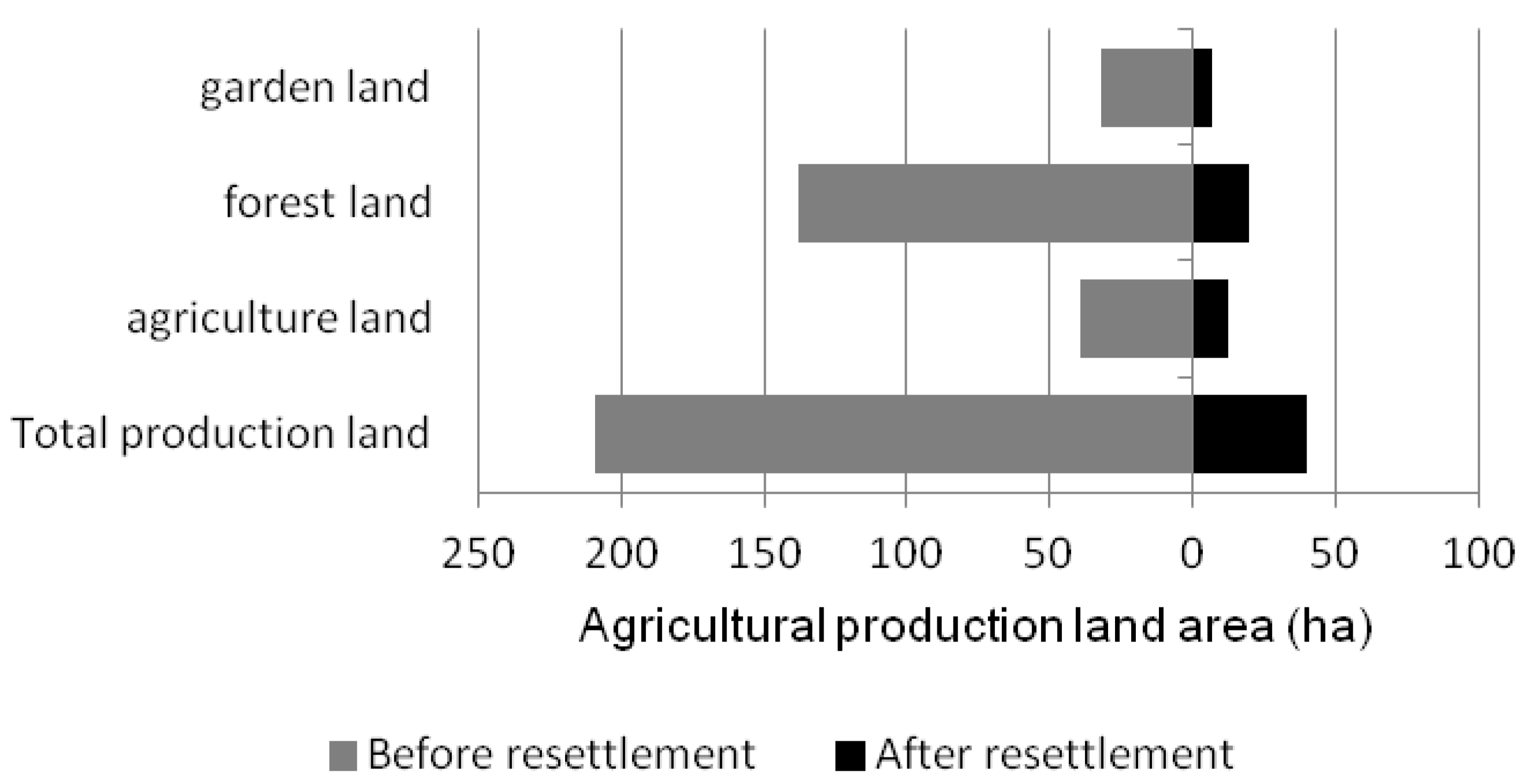

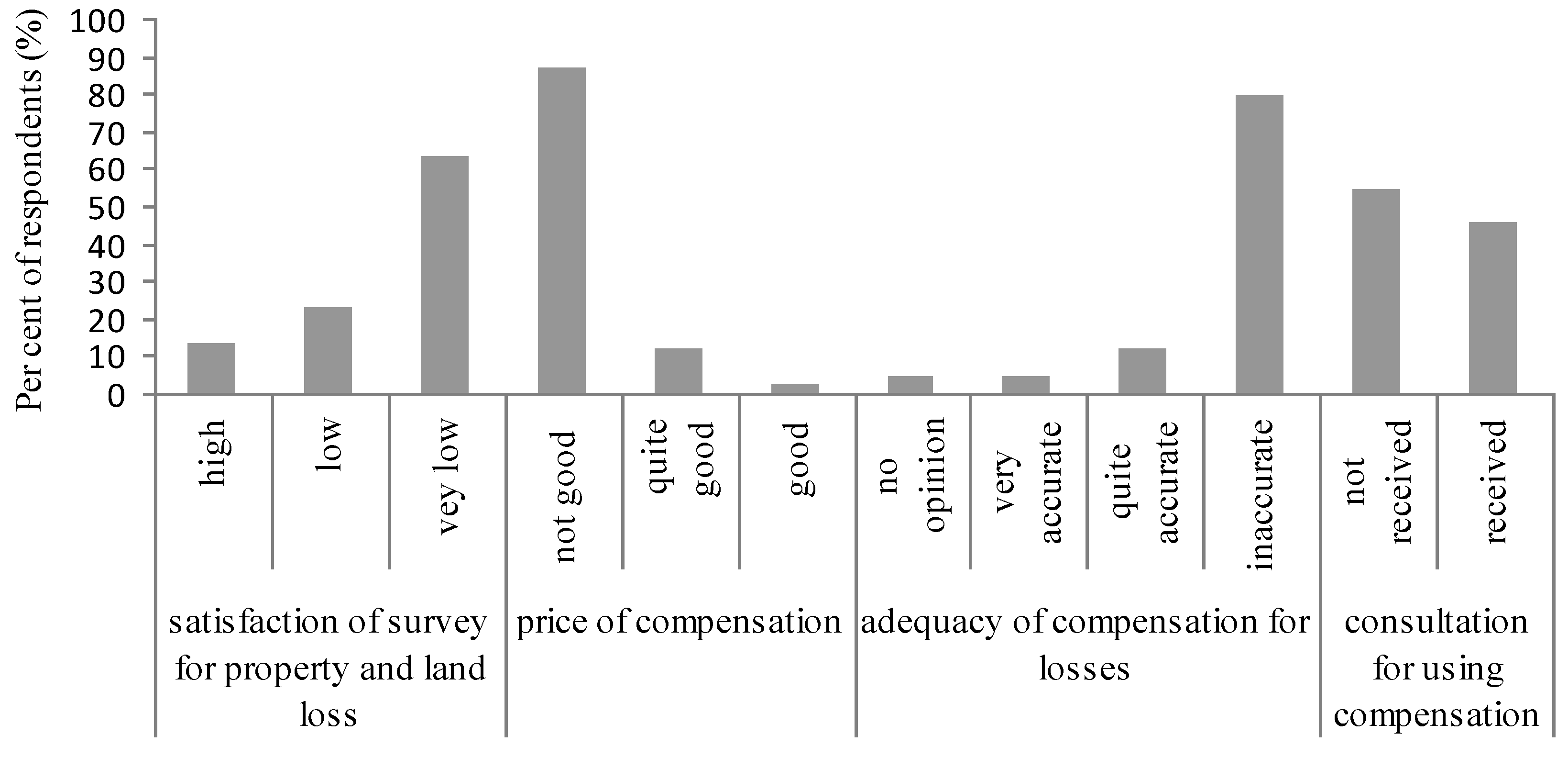

4.3. Compensation and Resettlement for A Den Households

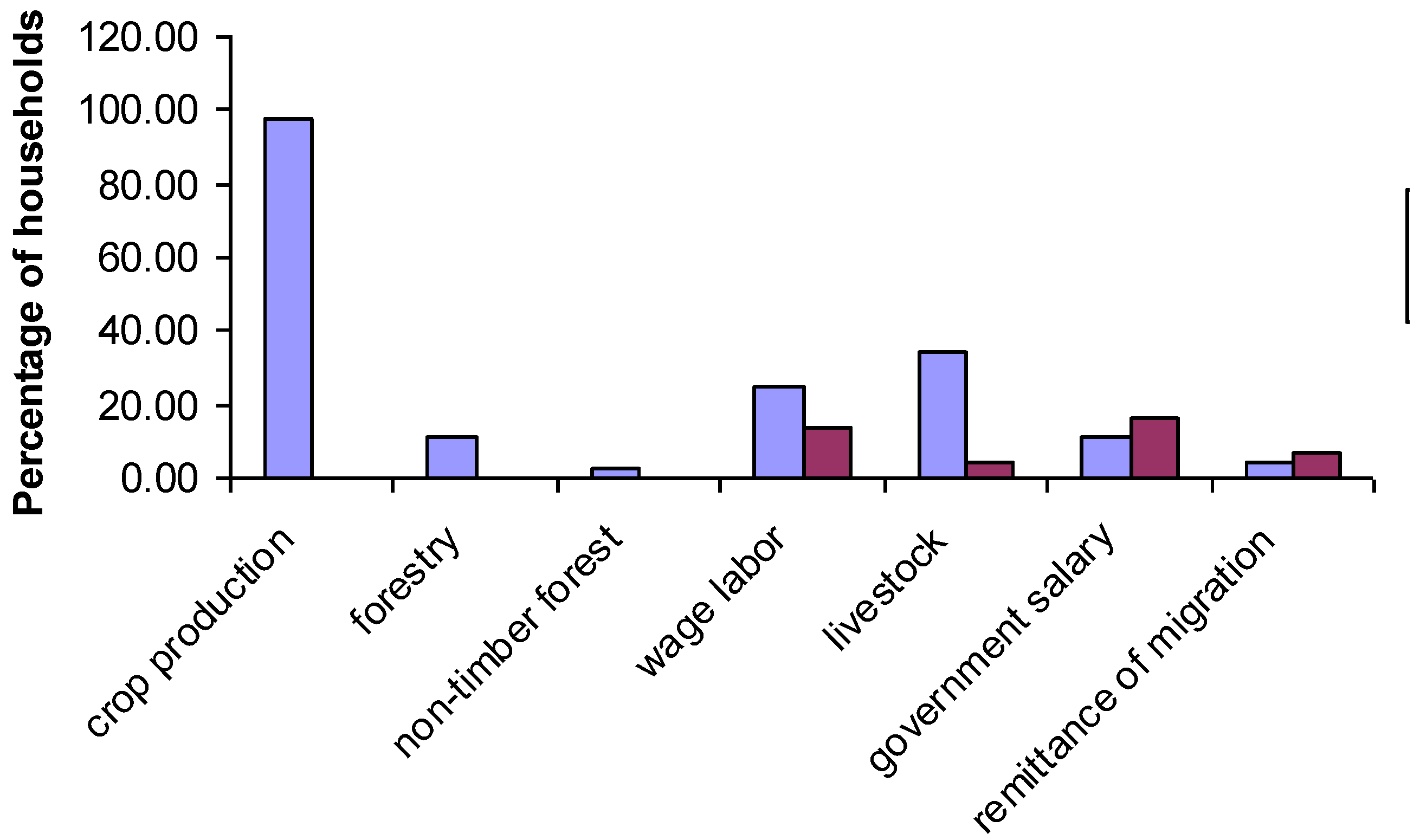

4.4. Problems after Resettlement

| Sum | Mean | Maximum | Minimum | Range | Variance | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| income before displacement | 1,428 | 32 | 243 | 0 | 243 | 1,457 | 38 |

| income after resettlement | 263 | 6 | 75 | 0 | 75 | 215 | 15 |

4.5. Discussions and Policy Implication

Policy Implications

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Viitanen, K.; Kakulu, I. Global Concerns in Compulsory Purchase and Compensation Process. In Proceedings of the Meeting of FIG Working Week 2008: Integrating Generations and FIG/UN-HABITAT Seminar: Improving Slum Conditions through Innovative Financing, Stockholm, Sweden, 14–19 June 2008.

- Alemu, B.Y. Expropriation, valuation and compensation practice in Ethiopia: The case of Bahir Dar city and surrounding. Prop. Manag. 2003, 31, 132–158. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.S.; Vu, K.T. Land acquisition in transitional Hanoi, Vietnam. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 1097–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusiluka, M.M.; Kongela, S.; Kusiluka, M.A.; Karimuribo, E.D.; Kusiluka, L.J.M. The negative impact of land acquisition on indigenous communities’ livelihood and environment in Tanzania. Habitat Int. 2004, 35, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Syagga, P.M.; Olima, W.H.A. The impact of compulsory land acquisition on displaced households: The case of the third Nairobi water supply project, Kenya. Habitat Int. 1996, 20, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M. The risks and reconstruction model for resettling displaced populations. World Dev. 1997, 25, 1569–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C. Policy and praxis of land acquisition in China. Land Use Policy 2007, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jayewardene, R.A. Cause for Concern: Health and Resettlemen. In Development, Displacement and Resettlement: Focus on Asian Experiences; Mathur, H.M., Cernea, M.M., Eds.; Vikas Publishing: New Delhi, India, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Larbi, W.O.; Antwi, A.; Olomolaiye, P. Compulsory land acquisition in Ghana—Policy and praxis. Land Use Policy 2004, 21, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.Q. Development and displacement in Bangladesh: Toward a resettlement policy. Asian Survey 1996, 36, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, R.; Roth, M. Land tenure and investment in African agriculture: Theory and evidence. J. Mod. Afri. Stud. 1990, 28, 265–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.C.M.; Bao, H. The logic behind conflicts in land acquisitions in contemporary China: A framework based upon game theory. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogami, H. The economics of involuntary resettlement: Questions and challenges edited by Michael M. Cernea. Dev. Econ. 2002, 40, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, S.; Taifur, W.D. Resettlement and development: A survey of two of Indonesia’s Koto Panjang resettlement villages. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2013, 29, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C. The effects of land acquisition on China’s economic future. Landlines. 2004. Available online: http://www.lincolninst.edu/pubs/872_Effects-of-Land-Acquisition-on-China-s-Economic-Future (accessed on 6 October 2013).

- Turton, D. Development and Change, 2009. In Review of the Book Can Compensation Prevent Impoverishment? Reforming Resettlement through Investments and Benefit-Sharing; Cernea, M.M., Mathur, H.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; Volume 40, pp. 977–993. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, H.; Schreinemachers, P. Resettling farm households in northwestern Vietnam: Livelihood change and adaptation. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2011, 27, 769–785. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, H.; Schreinemachers, P. Hydropower development in Vietnam: Involuntary resettlement and factors enabling rehabilitation. Land Use Policy 2013, 31, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coit, K. Housing policy and slum upgrading in Ho-Chi-Minh city. Habitat Int. 1998, 22, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, N. Dam development in Vietnam: The evolution of dam-induced resettlement policy. Water Altern. 2010, 3, 324–340. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A.M. A Market without the right? Property rights. Econ. Transit. 2004, 12, 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang, N.N. Vietnam and the sustainable development of the Mekong River Basin. Water Sci. Technol. J. Int. Assoc. Water Pollut. Res. 2002, 45, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Thu, T.T.; Perera, R. Consequences of the two-price system for land in the land and housing market in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank, Compulsory Land Acquisition and Voluntary Land Conversion in Vietnam: The Conceptual Approach, Land Valuation and Grievance Redress Mechanism; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- The Government Inspectorate of Vietnam, The Situation and Result of Citizen Meetings, Resolution of Complaints and Denunciations between 2008 and 2011 and Solutions for Coming Years; The Government Inspectorate of Vietnam: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2012.

- Ministry of Industry and Trade (MOIT)-Vietnam, Result of Hydropower Dam Construction Survey Nationwide; MOIT: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2007.

- Manyari, W.V.; de Carvalho, O.A. Environmental considerations in energy planning for the amazon region: Downstream effects of dams. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 6526–6534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerer, L.B.; Scudder, T. Health impacts of large dams. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1999, 19, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scodanibbio, L.; Mañez, G. The world commission on dams: A fundamental step towards integrated water resources management and poverty reduction? A pilot case in the Lower Zambezi, Mozambique. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2005, 30, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudder, T. Social Impacts of Large Dam Projects. In Large Dams: Learning from the Past, Looking at the Future; Dorcey, T., Steiner, T., Dorcey, A., Steiner, M., Acreman, M., Orlando, B., Eds.; International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)/The World Bank Group: Gland, Switzerland/Cambridge, UK, and Washington, DC, USA, 1997; pp. 41–68. [Google Scholar]

- Scudder, T. Social Impacts. In Water Resources: Environmental Planning, Management and Development; Biswas, A.K., Ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 623–665. [Google Scholar]

- Scudder, T. The world commission on dams and the need for a new development paradigm. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2001, 17, 329–341. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Development and Environment, Vietnam (CODE), Displacement, Resettlement, Living Stability and Environmental & Resources Protection in Hydropower Dam Projects; CODE: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2010.

- Centre for Consultation on Electricity 1 (CCE1)-Vietnam, Result of Livelihood Surveys in the Reservoirs of Hydropower Dam and Resettlement Planning for Lai Chau Hydropower Dam; CCE1: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2007.

- Department of Cooperatives and Rural Development (DOCRD)-Vietnam, Displacement and Resettlement Policies for National Programmes in the Mountainous Areas and Ethnic Minority Groups—Problems Needs to be Addressed; DOCRD: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2007.

- Full Name (ISPRE), The Status of Resettlement Programmes in the Hydropower Dams in Vietnam; ISPRE: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2009.

- World Bank, The World Bank Operational Manual; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Sebenius, J.K.; Eiran, E.; Feinberg, K.R.; Cernea, M.; McGovern, F. Compensation schemes and dispute resolution mechanisms: Beyond the obvious. Negot. J. 2005, 21, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M. Impoverishment Risks, Risk Management, and Reconstruction: A Model of Population Displacement and Resettlement. In Proceedings of the Meeting of the UN Symposium on Hydropower and Sustainable Development; Beijing, China: 20 October 2004.

- Yuefang, D.; Steil, S. China three gorges project resettlement: Policy, planning and implementation. J. Refug. Stud. 2003, 16, 422–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald-Wilmsen, B.; Webber, M. Dams and displacement: Raising the standards and broadening the research agenda. Water Altern. 2010, 3, 142–161. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank, Involuntary Resettlement Sources Book: Planning and Implementation in Development Projects; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2004.

- World Commission on Dams, Water and Development: A New Framework for Decision Making; The Earthscan Publications Ltd: London, UK/Sterling, VA, USA, 2000.

- Zoomers, A. Globalisation and the foreignisation of space: Seven processes driving the current global land grab. J. Peasant Stud. 2010, 37, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The International Finance Corporation. The Performance Standard 5—Land Acquisition and Involuntary Resettlement. Available online: http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/3d82c70049a79073b82cfaa8c6a8312a/PS5_English_2012.pdf?MOD=AJPERES (accessed on 24 October 2013).

- Knetsch, J.L. Property Rights and Compensation: Compulsory Acquisition and Other Losses; Butterworth & Co (Canada) Ltd: Toronto, Canada, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Asian Development Bank (ADB), Compensation and Valuation in Resettlement: Cambodia, ADB, People’s Republic of China and India; Report No. 9; ADB: The Philippines, 2007.

- International Valuation Standards Council. International Standard Framework. Available online: http://www.ivsc.org//sites/default/files/IVS%20Framework.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2013).

- Miceli, T.J.; Segerson, K. The economics of eminent domain: Private property, public use, and just compensation. Found. Trend. Microecon. 2007, 3, 275–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemann, P.; Shapiro, P. Efficiency and fairness: Compensation for takings. Int. Rev. Law Econ. 2008, 28, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ty, P.H.; Phuc, N.Q.; van Western, A.C.M. Vietnam in the Debate on Land Grabbing: Conversion of Agricultural Land for Urban Expansion and Hydropower Development. In The Forthcoming Book the Global Land Grab: Beyond the Hype; Kaag, M.M.A., Zommers, A., Eds.; Zed Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Thua Thien Hue Province. Annual Report of Provincial Budget in 2012. Available online: http://vbpl.thuathienhue.gov.vn/default.asp?opt=doc_all&sel=all_general&DocId=19441 (accessed on 4 November 2013).

- The Sai Gon Giai Phong Newspaper. The Efficiency of Budget Spending in Da Nang City. Available online: http://sgtt.vn/Goc-nhin/144298/Hieu-qua-chi-tieu-ngan-sach-nhin-tu-Da-Nang.html (accessed on 4 November 2013).

- Chapter 12. Policy Briefs. In Agricultural Development and Land Policy in Vietnam; Marsh, S.P.; MacAulay, T.G.; Hung, P.V. (Eds.) ACIAR Monograph No. 126; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research: Bruce, ACT, Australia, 2007; p. 72.

- Phan, V.Q.C.; Fujimoto, A. Land tenure and tenancy conditions in relation to rice production in three villages in the Red River Delta, Vietnam. Issaas 2012, 18, 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Stockholm Environment Institute, Strategic Environmental Assessment of Hydropower in Vietnam 1993–2004 in the Context of Power Development Plan VI; The National Political Publisher: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2007.

- Thua Thien Hue Provincial People’s Committee. Administration of Thua Thien Hue Province [Map]. Available online: http://thuathienhue.gov.vn/ (accessed on 3 May 2013).

- Central Hydropower Joint-Stock Company, Vietnam. Finance Planning in 2012. Available online: http://www.chp.vn/CoDong.html (accessed on 28 October 2013).

- The National Assembly of Vietnam. The 2003 Land Law. Available online: http://www.chinhphu.vn/portal/page/portal/chinhphu/hethongvanban?class_id=1&mode=detail&document_id=32479 (accessed on 28 October 2013).

- Le, P. Corruption through Friendship Groups. The Law Newspaper of Ho Chi Minh. Available online: http://phapluattp.vn/20130408114623224p0c1013/tham-nhung-qua-nh243m-th226n-huu.htm (accessed on 4 September 2013).

- Mai, V.T. From Changing Ways to Work to Some Urgent Issues of the Party Building at the Present. The Communist Review. Available online: http://www.tapchicongsan.org.vn/Home/xay-dung-dang/2013/20963/Tu-Sua-doi-loi-lam-viec-den-Mot-so-van-de-cap.aspx (accessed on 5 September 2013).

List of Interviews

1. Household Interviews 2011 and 2013

| Number of Respondents | Respondents’ Name | Address of Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hồ Văn Hồi | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 2 | Hồ Thị Xao | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 3 | Lê Thị Lai | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 4 | Hồ Thị Trang | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 5 | Hồ Thị Kết | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 6 | Hồ Thị Măl | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 7 | Hồ Văn Ngập | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 8 | Hồ Thị Năng | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 9 | A Viết Thị Phương | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 10 | Hồ Thị Ngoan | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 11 | Hồ Văn Líu | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 12 | Hồ Thị Ngươi | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 13 | Hồ Văn Hiếu | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 14 | Hồ Văn Lần | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 15 | Hồ Văn Hương | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 16 | Hồ Văn Nóch | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 17 | Hồ Văn Khươi | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 18 | Hồ Văn Long | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 19 | A Viết Huy | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 20 | Hồ Đắc Bồng | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 21 | Hồ Thị Lăng | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 22 | Hồ Thị Sơi | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 23 | Hồ Văn Trôi | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 24 | Hồ Thị Trể | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 25 | Hồ Văn Hách | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 26 | Hồ Văn Huỳnh | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 27 | Hồ Thị Tú | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 28 | Nguyễn Văn Ni | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 29 | Hồ Đắc Lộc | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 30 | Hồ Văn Huynh | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 31 | Hồ Thị Quốc | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 32 | Hồ Văn Ngân | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 33 | Phạm Xuân Sáng | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 34 | Hồ Văn Việt | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 35 | Hồ Văn Mùi | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 36 | Hồ Văn Mích | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 37 | Hồ Bá | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 38 | Hồ Văn Mạnh | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 39 | Hồ Văn Thoa | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 40 | Hồ Thị Ngư | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 41 | Hồ Văn Nghết | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 42 | Hồ Thị En | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 43 | Hồ Văn Minh | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 44 | Nguyễn Văn Bình | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 45 | Hồ Thị Ương | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 46 | Hồ Xuân Tả | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 47 | Kả Hình | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 48 | Hồ Thị Mựh | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 49 | Hồ Sỹ Ngà | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 50 | Hồ Văn Ngờ | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 51 | Hồ Thị Nụ | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 52 | Hồ Thị Xiên | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 53 | Hồ Thị Dên | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 54 | Hồ Văn Hoá | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 55 | Nguyễn Văn Tư | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 56 | Hồ Sĩ Dũng | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 57 | Hồ Văn Hồ | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 58 | Hồ Thị Tríu | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 59 | Hồ Xuân Võ | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

| 60 | Hồ Thị Vớt | A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam |

2. In-depth Interviews in 2013

- Hồ Sĩ Dũng—A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam

- Hồ Văn Mùi—A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, Aluoi District, Vietnam

3. Interviews with District Officials and a Staff of A Luoi Hydropower Dam in 2013

- Nguyễn Văn Rin—Staff of district department of natural resource and environment and a member of BCAR, A luoi district, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

- oàn Quang Pháp—Staff of district department of natural resource and environment and a member of BCAR, A luoi district, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

- Nguyễn Duy Chinh—Vice head of district department of natural resource and environment and a member of BCAR, A luoi district, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

- Hoàng Văn Nam—Staff of A luoi hydropower company and a member of BCAR, A luoi district, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

4. Interviews with Host Commune (Hong Thuong Commune, Aluoi District) in 2013

- Nguyễn Văn Sót—Chairman of Hong Thuong commune, A luoi district, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

- Lê Văn Dũng—Vice chairman of Hong Thuong commune, A luoi district, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

5. Interview with a Former Village Headman in 2013

- A Viết Huy—Former village headman – A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, A luoi district, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

6. Focus Group Discussion in 2013

- A Viết Huy—Former village headman—A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, A luoi district, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

- Nguyễn Văn Sót—Chairmain of Hong Thuong commune, A luoi district, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

- Hồ Văn Mích—Elder of A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, A luoi district, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

- Hồ Bá—Elder of A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, A luoi district, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

- Hồ Sỹ Ngà—Elder of A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, A luoi district, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

- Hồ Văn Khươi—Young people and cadastral official of Hong Thai commune, A luoi district, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

- Hồ Văn Minh—Young people and police of Hong Thai commune, A luoi district, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

- Hồ Xuân Tả—The patriarch of A Đên village, Hong Thai commune, A luoi district, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

7. Interview with a Former Vice Minister of Ministry of Natural Resource and Environment (MONRE) in 2013

- Prof. Dr. Đặng Hùng Võ—Hà Nội, Việt Nam

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Ty, P.H.; Van Westen, A.C.M.; Zoomers, A. Compensation and Resettlement Policies after Compulsory Land Acquisition for Hydropower Development in Vietnam: Policy and Practice. Land 2013, 2, 678-704. https://doi.org/10.3390/land2040678

Ty PH, Van Westen ACM, Zoomers A. Compensation and Resettlement Policies after Compulsory Land Acquisition for Hydropower Development in Vietnam: Policy and Practice. Land. 2013; 2(4):678-704. https://doi.org/10.3390/land2040678

Chicago/Turabian StyleTy, Pham Huu, A. C. M. Van Westen, and Annelies Zoomers. 2013. "Compensation and Resettlement Policies after Compulsory Land Acquisition for Hydropower Development in Vietnam: Policy and Practice" Land 2, no. 4: 678-704. https://doi.org/10.3390/land2040678

APA StyleTy, P. H., Van Westen, A. C. M., & Zoomers, A. (2013). Compensation and Resettlement Policies after Compulsory Land Acquisition for Hydropower Development in Vietnam: Policy and Practice. Land, 2(4), 678-704. https://doi.org/10.3390/land2040678