Strengthening Climate Resilience Through Urban Policy: A Mixed-Method Framework with Case Study Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Policy Review and Evaluation

2.2.1. Policy Review

2.2.2. Policy Evaluation Framework

2.2.3. Selected Policies

2.3. Semi-Structured Interview

3. Results

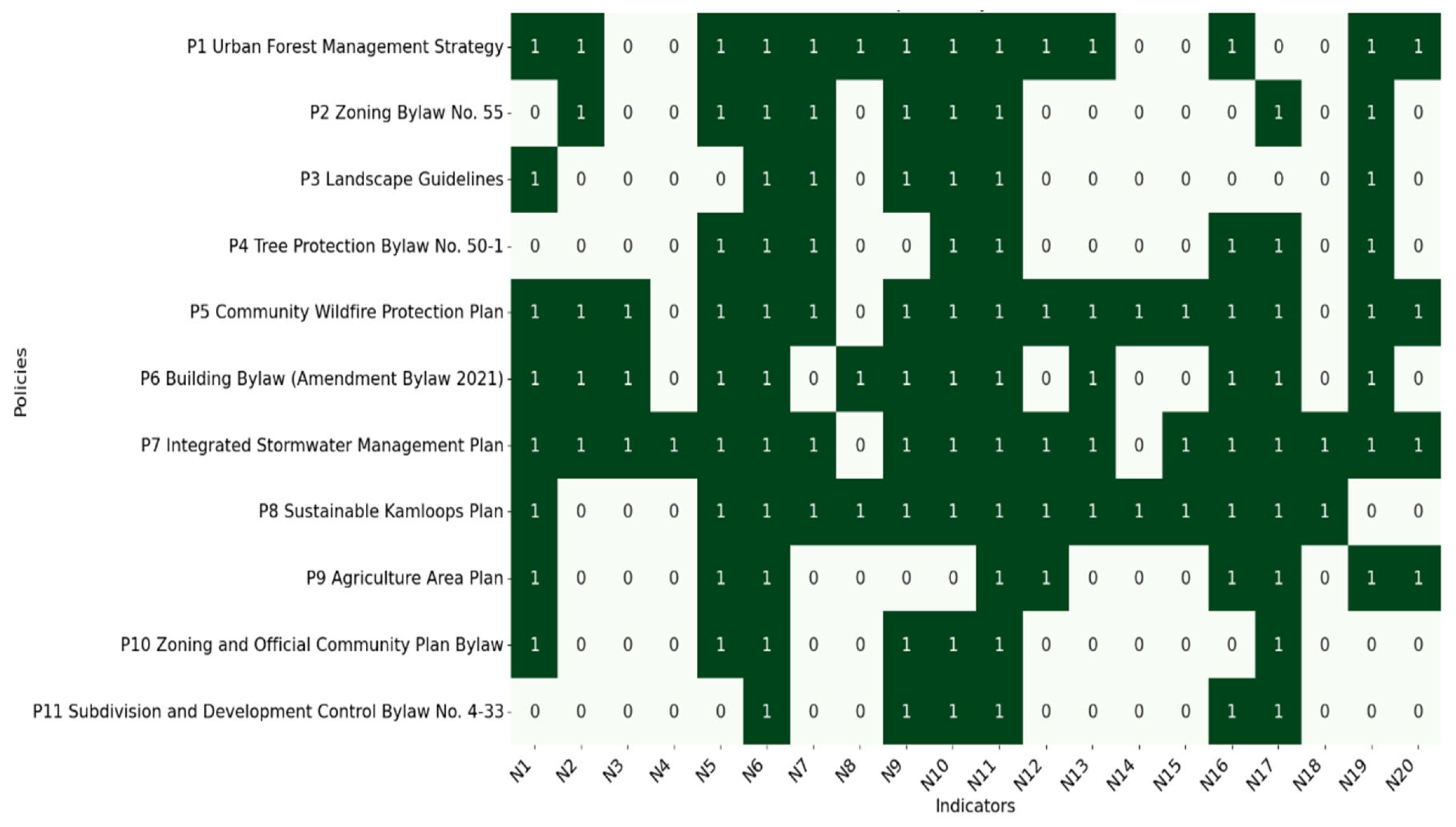

3.1. Current Policy Evaluation Results

3.2. Identified Challenges and Gaps

3.2.1. Lack of Adaptability and Flexibility

3.2.2. Lack of Clear Climate Change Goals

3.2.3. Lack of Emphasis on Education and Research

3.2.4. Absence of Long-Term Projections and Risk Assessments

3.2.5. Implementation Gaps

3.2.6. Unclear Funding and Resource Allocation

3.2.7. Unclear Partnerships and Collaborations

3.3. Interview Results

3.3.1. Discussions on Fundings Mechanisms and Collaborative Approaches to Resilience

3.3.2. Discussions on the Terms of Resilience

3.3.3. Discussions on Policy Updates

3.3.4. Discussions on Indigenous Community Involved

4. Policy Implications

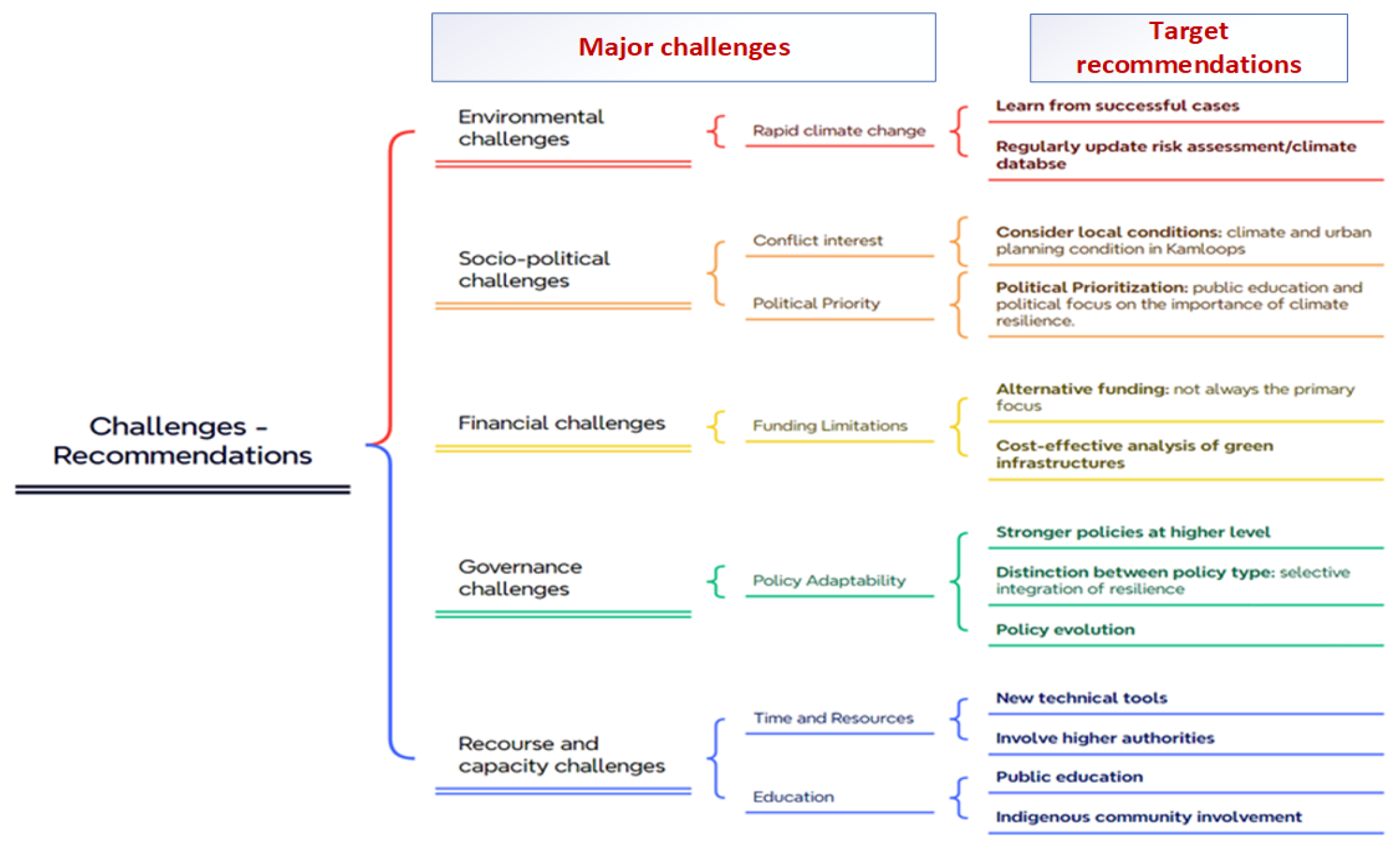

4.1. Challenges and Recommendations

- (1)

- Environmental challenges and recommendations

- (2)

- Social-political challenges and recommendations

- (3)

- Financial challenges and recommendations

- (4)

- Governance challenges and recommendations

- (5)

- Resource and capacity challenges and recommendations

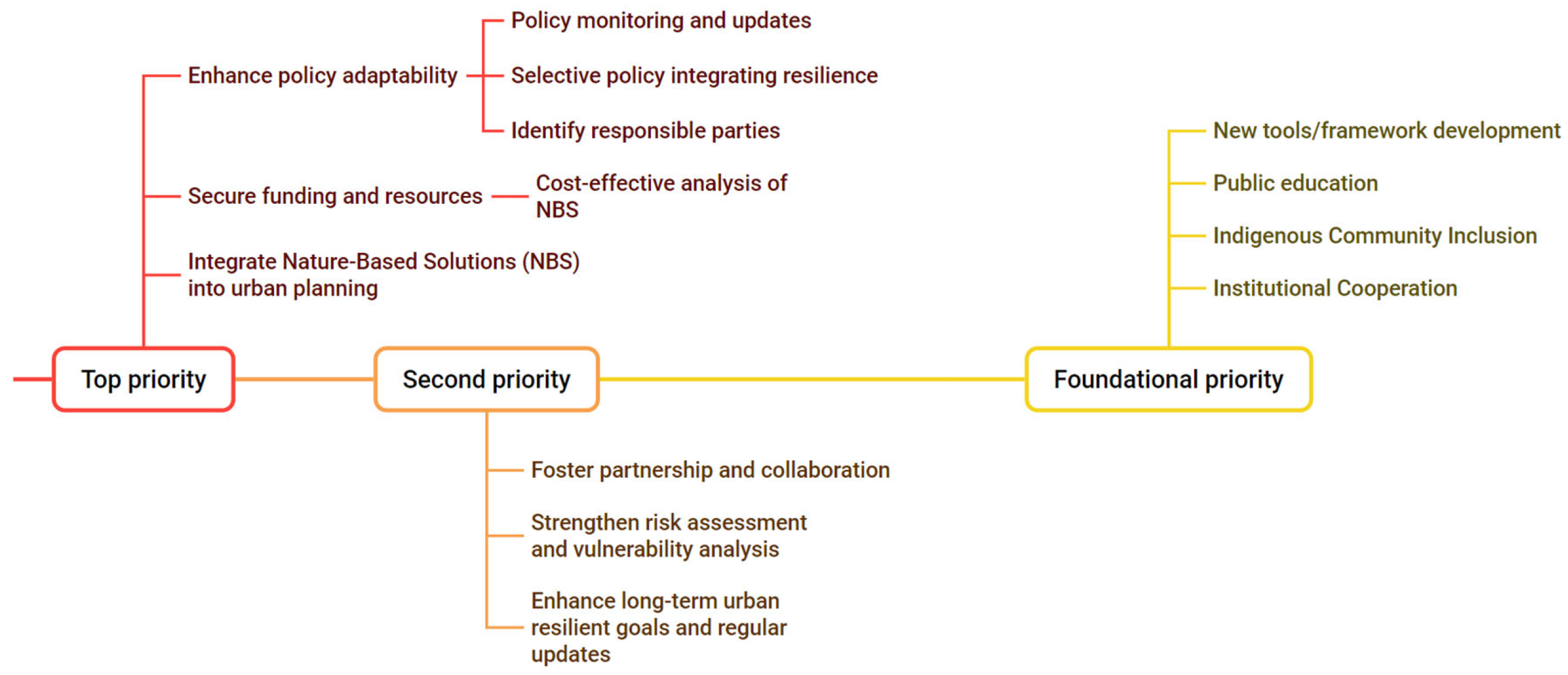

4.2. Next Steps for Integrating Resilience into Urban Policy Development

4.2.1. Top Priority: Immediate and High-Impact Actions

4.2.2. Second Priority: Supportive Measures for Urban Resilience

4.2.3. Foundational Priority: Establishing a Strong Institutional and Social Base

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tschakert, P.; Dietrich, K.A. Anticipatory Learning for Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, V.; Shields, J.; Akbar, M. Migration and Resilience in Urban Canada: Why Social Resilience, Why Now? Int. Migr. Integr. 2022, 23, 1421–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezvani, S.M.; Falcão, M.J.; Komljenovic, D.; de Almeida, N.M. A Systematic Literature Review on Urban Resilience Enabled with Asset and Disaster Risk Management Approaches and GIS-Based Decision Support Tools. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottar, S.; Wandel, J. Municipal Perspectives on Managed Retreat and Flood Mitigation: A Case Analysis of Merritt, Canada after the 2021 British Columbia Flood Disaster. Clim. Change 2024, 177, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.; Christianson, A.; Spinks, M. Return to Flame: Reasons for Burning in Lytton First Nation, British Columbia. J. For. 2018, 116, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirzadeh, M.; Sobhaninia, S.; Sharifi, A. Urban Resilience: A Vague or an Evolutionary Concept? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 81, 103853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C.; Mehta, L.; McGranahan, G.; Cannon, T.; Gupte, J.; Tanner, T. Resilience as a Policy Narrative: Potentials and Limits in the Context of Urban Planning. Clim. Dev. 2018, 10, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozza, A.; Asprone, D.; Manfredi, G. Developing an Integrated Framework to Quantify Resilience of Urban Systems against Disasters. Nat. Hazards 2015, 78, 1729–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, S.; Birchall, S.J. Climate Change Resilience in the Canadian Arctic: The Need for Collaboration in the Face of a Changing Landscape. Can. Geogr./Géographies Can. 2020, 64, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AminShokravi, A.; Heravi, G. Developing the Framework for Evaluation of the Inherent Static Resilience of the Access to Care Network. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Burton, C.G.; Emrich, C.T. Disaster Resilience Indicators for Benchmarking Baseline Conditions. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2010, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Feng, H.; Shao, Q. Evaluating Urban Flood Resilience within the Social-Economic-Natural Complex Ecosystem: A Case Study of Cities in the Yangtze River Delta. Land 2023, 12, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyeye, K.; Bairi, A.; Emmitt, S.; Hyde, K. Socially-Integrated Resilience in Building-Level Water Networks Using Smart Microgrid plus Net. Procedia Eng. 2018, 212, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, T.; Yodo, N. Resilience-Based Recovery Assessments of Networked Infrastructure Systems under Localized Attacks. Infrastructures 2019, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abenayake, C.; Jayasinghe, A.; Kalpana, H.; Wijegunarathna, E.; Mahanama, P. An Innovative Approach to Assess the Impact of Urban Flooding: Modeling Transportation System Failure Due to Urban Flooding. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 147, 102772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsari, R.; Shorabeh, S.; Lomer, A.; Homaee, M.; Arsanjani, J. Using Artificial Neural Networks to Assess Earthquake Vulnerability in Urban Blocks of Tehran. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coaffee, J.; Therrien, M.-C.; Chelleri, L.; Henstra, D.; Aldrich, D.P.; Mitchell, C.L.; Tsenkova, S.; Rigaud, É.; Participants, T. Urban Resilience Implementation: A Policy Challenge and Research Agenda for the 21st Century. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2018, 26, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderies, J.M.; Folke, C.; Walker, B.; Ostrom, E. Aligning Key Concepts for Global Change Policy: Robustness, Resilience, and Sustainability. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmutina, K.; Lizarralde, G.; Dainty, A.; Bosher, L. Unpacking Resilience Policy Discourse. Cities 2016, 58, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A.; Kirbyshire, A. Supporting Governance for Climate Resilience: Working with Political Institutions. Available online: https://odi.org/en/publications/supporting-governance-for-climate-resilience-working-with-political-institutions/ (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Dubinsky, L. In Praise of Small Cities: Cultural Life in Kamloops, BC. Can. J. Commun. 2006, 31, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labossière, L.M.M.; McGee, T.K. Innovative Wildfire Mitigation by Municipal Governments: Two Case Studies in Western Canada. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 22, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, A.A. Emergency Public Health Planning in British Columbia. Can. J. Public Health/Rev. Can. Sante’e Publique 1963, 54, 410–416. [Google Scholar]

- Engward, H.; Davis, G. Being Reflexive in Qualitative Grounded Theory: Discussion and Application of a Model of Reflexivity. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 1530–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnett, N.L.; Birchall, S.J. The Influence of Regional Strategic Policy on Municipal Climate Adaptation Planning. Reg. Stud. 2023, 57, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamout, S.; Boarin, P.; Wilkinson, S. The Shift from Sustainability to Resilience as a Driver for Policy Change: A Policy Analysis for More Resilient and Sustainable Cities in Jordan. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, S. The Effect of Pilot Climate-Resilient City Policies on Urban Climate Resilience: Evidence from Quasi-Natural Experiments. Cities 2024, 153, 105316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Li, D.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y. Climate Change Scenario Simulations for Urban Flood Resilience with System Dynamics Approach: A Case Study of Smart City Shanghai in Yangtze River Delta Region. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 112, 104801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Brown, K.; Nelson, D.R.; Berkes, F.; Eakin, H.; Folke, C.; Galvin, K.; Gunderson, L.; Goulden, M.; O’Brien, K.; et al. Resilience Implications of Policy Responses to Climate Change. WIREs Clim. Change 2011, 2, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G. Community Resilience and Environmental Transitions; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-203-14491-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L.; Kuhl, L.; Matthews, N. Addressing Power and Scale in Resilience Programming: A Call to Engage across Funding, Delivery and Evaluation. Geogr. J. 2020, 186, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemzadeh, S.; Talebiyan, H.; Talebi, S.; Duenas-Osorio, L.; Mesbahi, M. Resource Allocation for Infrastructure Resilience Using Artificial Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 32nd International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI), Baltimore, MD, USA, 9–11 November 2020; pp. 617–624. [Google Scholar]

- Boston, J.; Lawrence, J. Funding Climate Change Adaptation: The Case for a New Policy Framework. Policy Q. 2018, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, I.; Huq, S.; Lim, B.; Pilifosova, O.; Schipper, E.L. From Impacts Assessment to Adaptation Priorities: The Shaping of Adaptation Policy. Clim. Policy 2002, 2, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P. Urban Resilience for Whom, What, When, Where, and Why? Urban Geogr. 2019, 40, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, J.R.; Dovidio, J.F.; Thomsen, L. Fusion with Political Leaders Predicts Willingness to Persecute Immigrants and Political Opponents. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2019, 3, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wang, W.; Huang, G.; Zhou, S.; Zhu, S.; Feng, H. How to Enhance Citizens’ Sense of Gain in Smart Cities? A SWOT-AHP-TOWS Approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 165, 787–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Sun, Z.; Du, M. Differences and Drivers of Urban Resilience in Eight Major Urban Agglomerations: Evidence from China. Land 2022, 11, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Fan, X.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.-J. Resource Allocation Among Competing Innovators. Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 6059–6074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djalante, R.; Holley, C.; Thomalla, F.; Carnegie, M. Pathways for Adaptive and Integrated Disaster Resilience. Nat. Hazards 2013, 69, 2105–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plough, A.; Fielding, J.E.; Chandra, A.; Williams, M.; Eisenman, D.; Wells, K.B.; Law, G.Y.; Fogleman, S.; Magaña, A. Building Community Disaster Resilience: Perspectives from a Large Urban County Department of Public Health. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1190–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social and Ecological Resilience: Are They Related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D.J. The Applicability of the Concept of Resilience to Social Systems: Some Sources of Optimism and Nagging Doubts. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 1135–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.; Elmqvist, T.; Gunderson, L.; Holling, C.S.; Walker, B. Resilience and Sustainable Development: Building Adaptive Capacity in a World of Transformations. AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 2002, 31, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cretney, R. Resilience for Whom? Emerging Critical Geographies of Socio-Ecological Resilience. Geogr. Compass 2014, 8, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, D.A.; DeLeo, R.A.; Albright, E.A.; Taylor, K.; Birkland, T.; Zhang, M.; Koebele, E.; Jeschke, N.; Shanahan, E.A.; Cage, C. Policy Learning and Change during Crisis: COVID-19 Policy Responses across Six States. Rev. Policy Res. 2023, 40, 10–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, R.; Chapola, J.; Owen, K.; Hurlbert, M.; Foggin, A. Indigenous Land-Based Practices for Climate Crisis Adaptions. Explore 2024, 20, 103042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorji, T.; Rinchen, K.; Morrison-Saunders, A.; Blake, D.; Banham, V.; Pelden, S. Understanding How Indigenous Knowledge Contributes to Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience: A Systematic Literature Review. Environ. Manag. 2024, 74, 1101–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonda, N.; Flores, S.; Casolo, J.J.; Nightingale, A.J. Resilience and Conflict: Rethinking Climate Resilience through Indigenous Territorial Struggles. J. Peasant Stud. 2023, 50, 2312–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moggridge, B.J.; Thompson, R.M. Chapter 18—Indigenous Engagement to Support Resilience: A Case Study from Kamilaroi Country (NSW, Australia). In Resilience and Riverine Landscapes; Thoms, M., Fuller, I., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 363–387. ISBN 978-0-323-91716-2. [Google Scholar]

- City of Kelowna Flooding. Available online: https://www.kelowna.ca/our-community/environment/flooding (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Dharmarathne, G.; Waduge, A.O.; Bogahawaththa, M.; Rathnayake, U.; Meddage, D.P.P. Adapting Cities to the Surge: A Comprehensive Review of Climate-Induced Urban Flooding. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.; Webb, J. A Place-Based Model for Understanding Community Resilience to Natural Disasters. Glob. Environ. Change 2008, 18, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Climate Threats | Strategic Response | Related Policy | Resilience Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flooding | Improved stormwater management, floodplain mapping | Integrated Stormwater Management Plan Zoning Bylaw No. 55 Building Bylaw Tree Protection Bylaw Subdivision Control Bylaw | Construct flood barriers, restore natural floodplains |

| Wildfires | FireSmart programs, land-use planning | Community Wildfire Protection Plan Zoning Bylaw No. 55 | Conduct controlled burns, create defensible spaces |

| Extreme heat | Urban greening, heat response plans | Urban Forest Management Plan Zoning Bylaw No. 55 Landscape Guidelines Tree Protection Bylaw | Increase urban tree canopy, create cooling centers |

| Drought | Water conservation, alternative water sources | Sustainable Kamloops Plan Agriculture Area Plan | Implement water-saving technologies, diversify water supply sources |

| Dimensions | Indicators | Explanations |

|---|---|---|

| Goals | N1: Content of climate change | The content of climate change is included in the policy |

| N2: Climate change resilience integrated | The concept of climate change resilience is integrated in the policy. | |

| N3: Climate resilience as part of its own goal | The policy adopts the climate adaptation/resilience as part of its own goal. | |

| N4: Long-term goals | The policy has long-term goals on climate resilience. | |

| Policy content | N5: Climate change resilience strategies | The policy has detailed requirements/strategies on climate change and resilience enhancement. |

| N6: Land-use and development strategies related to climate impacts | The policy involves the land-use and development strategies related to climate impacts. | |

| N7: Green infrastructure strategies related to climate impacts | The policy involves the green infrastructure strategies related to climate impacts. | |

| N8: Energy strategies related to climate impacts | The policy involves the energy strategies related to climate impacts. | |

| N9: Resilience strategy connections with provincial or national policy | The policy mentions its connections with related provincial or national resilience policy. | |

| N10: Resilience strategy connections with other policy. | The policy mentions its connections with other related policies. | |

| N11: Language used and strength of policies | Clear mandates, uses strong language, e.g., should versus must | |

| N12: Education and research | The policy mentions the need for education and research in climate resilience. | |

| Fact Base | N13: Reliable climate data | The policy is supported or developed based on reliable climate data or it provides access to reliable climate data. |

| N14: Long-term projections | The policy requires long-term projection of a particular natural disaster. | |

| N15: Risk assessment or vulnerability analysis | The policy requires risk assessment or vulnerability analysis for a particular natural disaster. | |

| Implementation | N16: Implementation plan with individual actions | The policy includes an implementation plan with individual actions. |

| N17: Implementation timeline | The implementation timeline of the policy is clear. | |

| N18: Funding identified | There are fundings supporting the implementation of the policy. | |

| N19: Responsible parties identified | Responsible parties are identified in the policy. | |

| N20: Partnerships and collaborations | The policy develops meaningful relationships between organizations and citizens. |

| No. | Name of the Policy | Year | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Urban Forest Management strategy | 2016 | A plan to enhance and manage the urban tree canopy to improve resilience to climate change. |

| P2 | Zoning Bylaw No. 55 | 2021 | Regulations governing land use and development, including provisions for climate resilience. |

| P3 | Landscape Guidelines | 2007 | Guidelines promoting sustainable landscaping practices to mitigate climate impacts. |

| P4 | Tree Protection Bylaw No. 50-1 | 2017 (Amendment bylaw 2022) | A bylaw aimed at preserving and protecting trees within the city to enhance green infrastructure. |

| P5 | Community wildfire protection plan | 2016 | Focuses on reducing wildfire risks through FireSmart programs, land-use planning, and community education. |

| P6 | Building Bylaw | 2006 (Amendment bylaw 2021) | Regulations ensuring that building designs and constructions adhere to resilience and sustainability standards. |

| P7 | Integrated Stormwater Management Plan | 2009 | Plan addressing stormwater management to prevent flooding and enhance water quality. |

| P8 | Sustainable Kamloops Plan | 2010 | Guidelines promoting sustainable development practices to reduce environmental impact and enhance resilience. |

| P9 | Agriculture Area Plan | 2013 | A plan aimed at promoting sustainable agricultural practices and enhancing the resilience of agricultural areas to climate change. |

| P10 | Zoning and Official Community Plan Bylaw Amendments for Compliance with Provincial Housing Legislation | 2024 | Amendments to ensure zoning and community plans comply with provincial housing legislation, promoting sustainable and resilient housing development. |

| P11 | Subdivision and Development Control Bylaw No. 4-33 | 2012 | A bylaw regulating the subdivision and development process to ensure sustainable and resilient community growth. |

| Main Challenges | Suggestions |

|---|---|

| Rapid climate change conflicting interests (e.g., development vs. natural resource protection). Funding limitations. Policies need to be adaptable | Look at successful cases like Logan Lake and Kelowna consider the specific climate and conditions of Kamloops compared to other regions in BC Involve higher authorities, such as the National Energy Board, to ensure big companies are held accountable for restoration and other responsibilities. Emphasis on the need for stronger policies at higher levels to support local policy enforcement |

| Four to five years ago, understanding the impacts of climate change on the community was a significant challenge. Time and resources are always a general challenge but not specific to climate resilience policies. | Recognized a distinction between regulatory documents (like the subdivision development control bylaw) and visionary policies (like the Official Community Plan). Suggested that resilience should be incorporated primarily in higher-level, visionary policies rather than detailed regulatory documents. Emphasized the importance of selecting appropriate locations for development to avoid flood-prone areas and integrate natural flood protection methods. Climate resilience should be integrated selectively, focusing on policies where it is most relevant rather than uniformly across all policies. |

| Political Priority: Climate resilience is not always a high political priority, impacting policy development. Education: Need for education among staff, politicians, and the public to prioritize climate resilience. | Exploring practical, cost-effective tools and requirements to enhance climate resilience without adding undue regulatory burdens. The need for greater public education and political prioritization of climate resilience |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, S.; Feng, H. Strengthening Climate Resilience Through Urban Policy: A Mixed-Method Framework with Case Study Insights. Land 2025, 14, 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040890

Zhu S, Feng H. Strengthening Climate Resilience Through Urban Policy: A Mixed-Method Framework with Case Study Insights. Land. 2025; 14(4):890. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040890

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Shiyao, and Haibo Feng. 2025. "Strengthening Climate Resilience Through Urban Policy: A Mixed-Method Framework with Case Study Insights" Land 14, no. 4: 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040890

APA StyleZhu, S., & Feng, H. (2025). Strengthening Climate Resilience Through Urban Policy: A Mixed-Method Framework with Case Study Insights. Land, 14(4), 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040890