1. Introduction

As a policy tool for land management, land consolidation (LC) is commonly employed to reconcile the conflict between economic development and land use across various countries [

1]. It serves as a significant catalyst for sustainable rural development [

2] and has attracted the attention of scholars, experts, and policymakers worldwide [

3]. Relevant studies indicate that land consolidation facilitates the reduction in land fragmentation [

4], enhances land use efficiency, improves highway accessibility, optimizes rural spatial structures [

5], boosts agricultural output, increases profitability [

6] and elevates the living standards of farmers [

7]. However, due to the diverse natural, social, economic, and policy environments across different countries, substantial variations exist in the objectives, methods, and procedures of land consolidation [

8], leading to differing impacts on rural areas and farmers.

China’s land consolidation has progressed rapidly over the past three decades. Initially, the primary objective of land consolidation was to increase the amount of cultivated land [

9]. However, it has now evolved into comprehensive land consolidation (CLC), which aims to enhance intensive production, improve quality of life, and promote ecological sustainability [

10]. Currently, China’s rural regions face significant challenges, including the abandonment of agricultural land, the vacancy of residential plots, the outflow of rural talent, and the degradation of the ecological environment [

11,

12]. These issues severely hinder the sustainable development of rural areas [

13]. Particularly in the mountainous areas of southwest China, farmers encounter significant risks in their daily lives and production due to the constraints imposed by the terrain and environmental fragility, which limit available alternative livelihood options [

7]. For these farmers, land constitutes the most essential production resource, providing crucial support for survival, agricultural activities, and social security [

14,

15]. Consequently, investigating the effects of CLC on farmers’ livelihoods is vital for promoting sustainable development in these mountainous regions.

“Livelihood” refers to a living based on capabilities, assets, and activities. A livelihood is considered sustainable when it can withstand external shocks, maintain asset levels, and achieve the sustainable use of natural resources [

16]. Scholars around the world have extensively explored the issue of sustainable livelihoods, developing various analytical frameworks. The Sustainable Livelihood Framework (SLF) established by the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) [

17] has become a mainstream paradigm due to its systematic approach and applicability [

18]. It analyzes how livelihood assets, within the context of vulnerability, influence livelihood strategies through structures and processes, subsequently affecting livelihood outcomes and promoting sustainable development for farmers. Initially, the SLF was primarily used to analyze the relationship between poverty in rural areas and the vulnerability of farmers [

19]. As research has evolved, scholars have utilized SLF to examine the development of farmers’ livelihoods under different vulnerability contexts, such as climate change [

20], environmental risks [

21], water–energy–food nexus [

22], and land reclamation policies [

23]. Additionally, some researchers have adapted and innovated SLF in response to contemporary challenges, highlighting a structured, dynamic, and ecologically coordinated approach to defining rural livelihoods [

24].

Currently, scholars have begun to investigate the impact mechanisms of land consolidation on farmers’ livelihoods based on the SLF. However, most studies focus on single projects, such as the effects of agricultural land consolidation (ALC) on farmers’ livelihoods [

23,

25]. For instance, Zhang et al. [

26] studied the impact of ALC on the incomes of both impoverished and non-impoverished households, indicating that ALC can promote income increases for both groups, with the income growth effect being greater for non-impoverished households. Olivia et al. [

27] examined the changes in smallholder livelihood strategies in Argentina’s Gran Chaco region, which is undergoing large-scale land development, suggesting that due to the constraints of land dynamics and resource acquisition pressures, cattle and sheep breeders may be more inclined towards stable pig farming. The comprehensive land consolidation (CLC) proposed by the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) emphasizes not only the reallocation of parcels but also other measures to promote rural development, such as building road networks, controlling soil erosion, and managing and protecting village environments [

28]. In China, CLC encompasses not only agricultural land consolidation (ALC) but also rural construction land consolidation (RLC) and ecological protection and restoration (EPR). However, there is currently a lack of systematic elaboration and quantitative research on the effects of CLC on farmers’ livelihoods.

In the southwestern mountainous regions of China, the significant variation in elevation and slope creates heterogeneous geographical conditions that may lead to spatial differentiation in the effects of CLC. Existing research has already highlighted the impact of CLC under different natural conditions on farmers’ livelihoods. For example, Li et al. [

29] considered factors such as elevation and slope in their study of the effects of land consolidation on sustainable poverty alleviation, revealing that higher elevations and steeper slopes significantly negatively affect the implementation outcomes of land consolidation. Zhang et al. [

30] investigated the income-increasing effects of agricultural land consolidation in both plain and mountainous areas, finding that the income growth effect in plain areas is markedly greater than that in mountainous areas. Most existing studies employ a binary classification framework of “plain-mountain”, overlooking the nuanced regulation of CLC effects by the continuous gradient of topography and lacking a systematic analysis of the relationship between terrain gradients and the effects of CLC. Current studies on terrain gradients primarily focus on multiple factors, including elevation, slope, terrain relief, and terrain position index, to explore the effects of terrain gradients on regional land use [

31], habitat quality [

32], and rural revitalization [

33], thereby providing theoretical support for this research.

This study focuses on the Anning River basin in the mountainous region of southwest China, where it examines terrain gradients using elevation, slope, and the terrain position index. It collects livelihood data from farmers across different terrain gradients through a questionnaire survey, analyzes the impact of CLC on farmers’ livelihood capital and strategies, and offers policy recommendations, aiming to provide references for the implementation of CLC and the sustainable livelihood development of farmers in the Anning River basin.

5. Discussion

Land is the most important production factor and source of livelihood for farmers, especially in the rural areas of the southwestern mountainous regions where alternative livelihood options are scarce [

7]. CLC is expected to significantly impact farmers’ livelihoods. However, existing research has rarely considered the differential impacts of CLC across various terrain gradients. This study addresses this gap by analyzing the effects of CLC on farmers’ livelihoods from a theoretical perspective, taking into account the complex topography of the Anning River basin. By calculating the Livelihood Capital Index based on household livelihood data, we examine the changes in livelihood capital before and after CLC. The results indicate that CLC has both positive and negative impacts on farmers’ natural capital, while positively affecting human, material, financial, and social capital. This aligns with the findings of Zhang [

7] and Xie [

35]. However, the predecessors focused on the effects of agricultural land consolidation, whereas this study provides a comprehensive analysis of all elements involved in CLC. Across different terrain gradients, the changes in farmers’ livelihood capital and the net effects of CLC exhibit a trend of medium-terrain areas > low-terrain areas > high-terrain areas, which is consistent with Zhang’s conclusions regarding the income effects of agricultural land consolidation based on landform types [

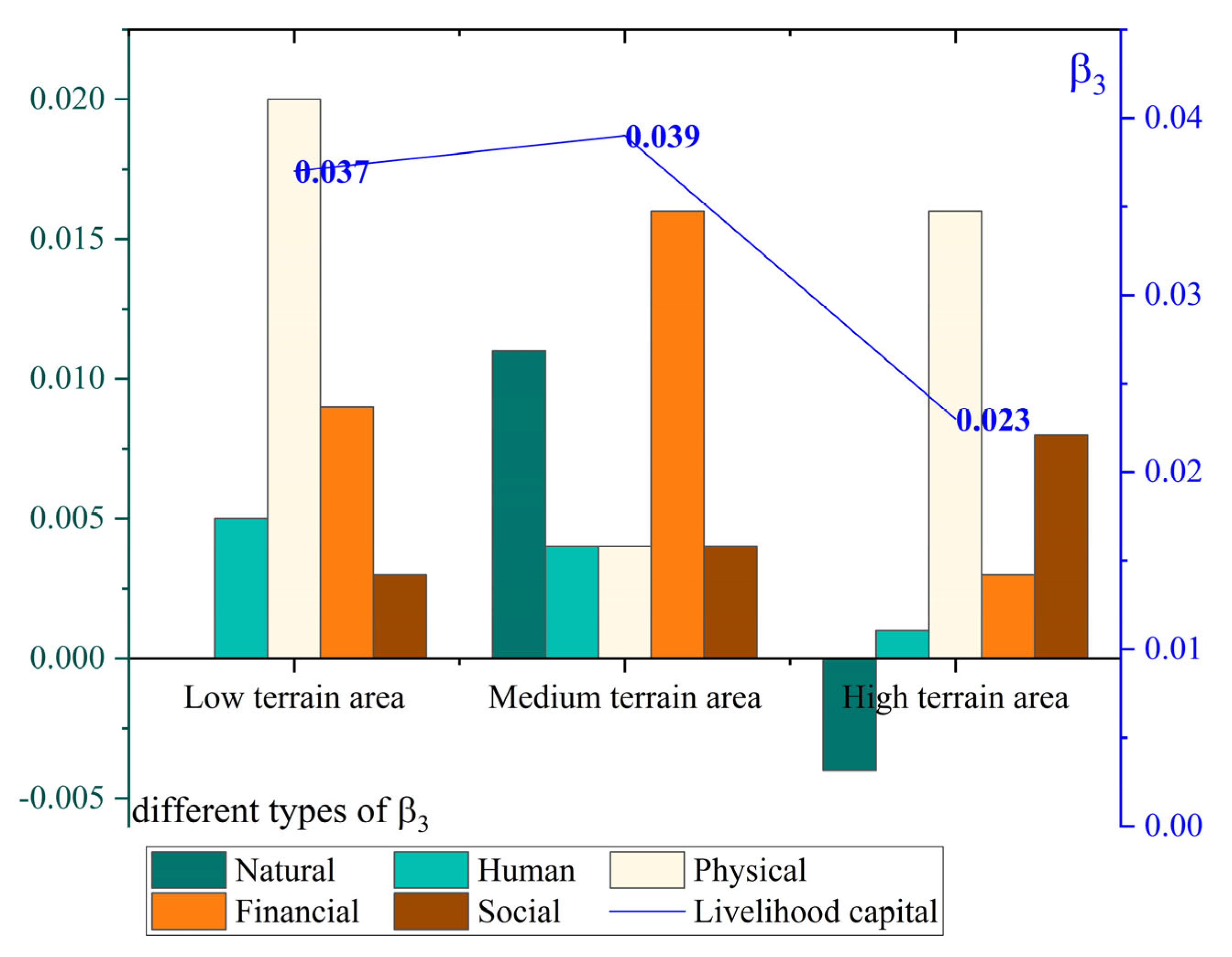

30]. This trend can primarily be attributed to the substantial landholdings of farmers in the medium-terrain areas, which, after participating in CLC, have led to large-scale cultivation, improved land use efficiency, and increased agricultural output, resulting in significant gains in natural and financial capital for these farmers.

In terms of farmers’ livelihood strategy, CLC has led to a general shift towards diversification and non-farm activities, aligning with the conclusions of Wu [

46] that the construction of high-standard farmland promotes the transition of traditional smallholder livelihood strategies towards diversification and non-farm activities. However, changes in livelihood strategies across different terrain gradients exhibit variability. In the low-terrain areas, farmers are transitioning from traditional agricultural types and agricultural multi-employment types to non-agricultural multi-employment types and non-agricultural types. This shift is primarily due to the fact that many farmers in the low-terrain area have transferred their land, allowing them to engage in diverse livelihood activities, consistent with the findings of Han [

47]. In medium-terrain areas, farmers are transitioning from traditional agricultural types to modern agricultural types, as CLC has resulted in enabling farmers to participate in village cooperatives for large-scale modern agricultural production. In high-terrain areas, the shift is mainly from traditional agricultural and agricultural multi-employment types to non-agricultural multi-employment types. This is because farmers in these areas have seen their farmland become state-owned after relocating, with family labor primarily engaged in local and external wage work and business activities, resulting in minimal agricultural production. Using the ordered logistic regression model, this study assesses the direct and indirect impacts of CLC on farmers’ livelihood strategies and identifies the livelihood factors influencing these strategies. This provides a scientific basis for the selection of livelihood strategies and promotes the sustainable development of farmers in mountainous areas.

However, this study has some limitations. First, CLC is a complex project that includes agricultural land consolidation, construction land consolidation, and rural ecological protection and restoration. The analysis of the impact of CLC on farmers’ livelihood capital and strategies is somewhat general and lacks in-depth research on the effects of different land consolidation projects on farmers’ livelihood, which is insufficient to establish an impact mechanism. Future research should explore the logical relationships among various CLC projects impacting on farmers’ livelihood capital and transitions, as well as conduct empirical studies to investigate the mechanisms. Second, the sample villages selected for the survey are limited in number and coverage. Although these villages were selected based on multiple criteria to ensure typicality and have passed reliability and validity tests, the results may not sufficiently reflect the overall impact of CLC across the entire Anning River basin. Future research should expand to include other project areas within the basin, broaden the scope of the investigation, and involve multiple rounds of long-term data collection from the same sample of households. This would help establish a sustainable monitoring mechanism for changes in household livelihoods, with the aim of guiding sustainable livelihood development for farmers.

6. Conclusions

In the context of developing the “Second Granary of Tianfu” in the Anning River basin, this study considers the complexity of the region’s topography by classifying it into terrain gradient zones based on elevation, slope, and terrain position index. It investigates typical villages across different terrain gradients to obtain multidimensional livelihood data and analyzes the impact of CLC on farmers’ livelihoods and the effects of terrain gradient, leading to the following conclusions: (1) CLC can effectively enhance farmers’ livelihood capital, demonstrating a trend of medium-terrain area > low-terrain area > high-terrain area. However, it has negative effects on the natural capital of certain farmers, primarily due to an increased willingness of some farmers to transfer land and the reclamation of land by the state from relocated households. (2) After CLC, the trend of farmers’ livelihood type transformation generally shifted from traditional agricultural types to modern agricultural types and agricultural multi-employment types, and from agricultural multi-employment types to non-agricultural multi-employment types. This indicates that CLC is driving an overall transition of farmers’ livelihood types towards diversification and non-agricultural activities. (3) CLC has a significant direct impact on the livelihood transition of farmers in low-terrain areas, while its effects in medium-terrain areas and high-terrain areas are not significant. From an indirect perspective, CLC significantly influences farmers’ livelihood transitions by affecting cultivated land area, irrigation water adequacy, labor skill levels, the value of production materials, annual household income, annual agricultural income, income channels, borrowing channels, and land disputes.

The study on the impact of CLC on farmers’ livelihoods in the Anning River basin has identified issues related to terrain constraints, resource limitations, natural capital loss, and variations in land quality. In response, differentiated policy measures for CLC have been proposed for high-, medium-, and low-terrain areas as follows.

For villages in high-terrain areas that are ecologically fragile and unsuitable for long-term habitation, priority should be given to disaster risk relocation, ecological relocation, and off-site relocation, along with rural construction land consolidation and community service center establishment. For villages suitable for development, soil improvement projects and ecological compensation for reforestation should be implemented to maximize ecological benefits.

In medium-terrain areas, where CLC significantly enhances farmers’ livelihood capital, further implementation is needed, including land leveling, irrigation systems, and field road construction to improve agricultural land quality and infrastructure. Local resources, such as ecological livestock farming and high-value cash crops, should be utilized to expand agricultural product distribution channels.

In low-terrain areas, where some villages have already established large-scale crop cultivation and cooperative organizations, those not yet implementing CLC should learn from these examples and enhance land use efficiency. This land can be transferred to agricultural companies or cooperatives for modern farming. Additionally, ecological protection of river systems should focus on vegetation measures for riverbank greening to reduce runoff and prevent soil and water loss.