Abstract

In the context of the implementation of the rural revitalization strategy in China, returning rural migrant workers are bound to have a certain impact on the rural economy, and land is a very important factor in the agricultural economy. Using data from the 2018 China Labor Dynamic Survey (CLDS), this study examines how migrant workers’ return behaviors influence farmland transfer-in. To address potential endogeneity, the analysis employs the Probit model, instrumental variable methods, and propensity score matching. The findings reveal that returning migrant workers significantly promote farmland transfer-in. Households with returning migrant workers exhibit stronger demands for land transfer-in and tend to operate farmland on a larger scale. Furthermore, returning migrant workers drive farmland expansion through mechanization labor substitution, enhanced access to agricultural loans, and reduced non-farm participation. Additionally, returning migrant workers who are highly educated and younger play a particularly influential role, underscoring the heterogeneous impacts across different migrant groups. This study provides empirical evidence for rural revitalization policies in China by systematically analyzing the effect of returning migrant workers in promoting land transfer-in and the path of influence on farmland scale.

1. Introduction

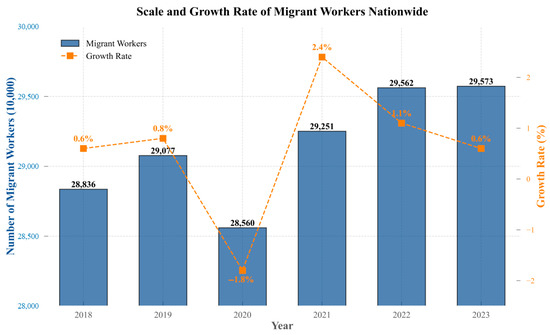

In recent years, China’s economic development has entered a new normal, with the industrial structure constantly upgraded and some low- and medium-end industries moving to South-East Asia, where labor prices are lower, resulting in fewer and fewer urban jobs. Against this backdrop, China government proposed the implementation of the ‘Rural Revitalization Strategy’, which provides new ideas for solving the ‘Three Rural Issues’ in the new era. With the implementation of the Rural Revitalization Strategy and the integration of urban and rural areas, rural transport, financial support, network information technology, and other infrastructures have improved significantly, farmers who used to go out to work have chosen to return to start their own businesses, and the return of rural migrant workers to their hometowns has gradually become the ‘norm’. Figure 1 illustrates scale and growth rate of migrant workers’ migration in China. The Data from the National Rural Workers Monitoring and Survey Report show that the proportion of migrant workers going out to work in China has dropped from 63.3% in 2010 to 59.4% in 2023, while the proportion of local migrant workers has risen from 36.7% to 40.6%, with the return of migrant workers from central and western regions obvious, and the number of migrant workers employed in the central and western regions in 2023 will be 69.82 million and 65.52 million, up 3.1% and 3.1% from the previous year by 3.1 per cent and 1.8 per cent, respectively, while the number of employed migrant workers in the eastern region during the same period decreased by 1.1 per cent from the previous year. Compared with local farmers, returning rural migrant workers often have higher human capital and have accumulated a large amount of wealth, and, in the context of the implementation of the rural revitalization strategy, returning rural migrant workers are bound to have a certain impact on the rural economy, which is the main motivation for the research in this paper.

Figure 1.

Scale and growth rate of migrant workers’ migration in China.

Looking back at the history of China’s population mobility, the reform of state-owned enterprises in the late 1990s and the impact of the global financial crisis on the export-oriented enterprises in the southeast coast in 2008 have both seen a wave of migrant workers returning to their hometowns. However, these were short-term passive returns caused by macroeconomic fluctuations, and most of the returnees still have the possibility to go out again [1]. Such a short-term return of rural migrant workers often only increases the surplus labor force in the countryside and does not have a significant impact on the rural economy [2]. Unlike in the past, the implementation of the rural revitalization strategy has led to the ‘normalization’ of rural migrant workers’ return to their hometowns, with a certain scale and sustainability [3]. This ‘normalization’ of rural migrant workers‘ return to their hometowns has attracted widespread attention from scholars at home and abroad, and the existing research mainly focuses on the impact of rural migrant workers’ return to their hometowns on the returnees and their families and on changes in the social and economic structure of rural areas. Compared with those who remain in rural areas, returning migrant workers tend to have stronger learning capabilities and adaptability [4], exhibit a higher propensity for entrepreneurship [5,6], and possess greater social capital [7].

The literature indicates that experience in off-farm employment plays a crucial role in enhancing the capital advantages of farm households. One of the primary reasons for this is that urban jobs offer higher incomes, allowing returning farm households to secure higher wages based on their previous participation in the urban labor market. Additionally, due to the transfer costs associated with returning [8], returning farmers may accumulate capital by saving a portion of their earnings or reducing their cost of living, thereby further strengthening their capital advantages. And research indicates that they can increase household incomes and savings rates [9]. At the same time, parents returning to their hometowns positively influence the physical and mental well-being of left-behind children, thereby significantly improving their quality of life [10]; however, some studies suggest that returning migrant workers may decrease their investment in children’s education [11]. For the rural socio-economic structure, most studies have concluded that this return of migrant workers is economically justified and that returning rural labor positively influences local economic development. Research suggests that returning migrant workers are integral to rural economic revitalization, social capital formation, and the reallocation of human resources [12]. Through resource flows and industrial integration, returning migrant workers propel rural economic development and stimulate rural industry revitalization [13]. Additionally, they significantly transform rural employment structures by encouraging the expansion of non-agricultural sectors and diversifying rural labor markets [14]. Further research shows that returning migrant workers create rural employment opportunities through entrepreneurship and investment [15], fostering a shift toward a more diversified rural economic structure [16]. Returning migrant workers alleviate rural labor shortages and promote the transformation and sustainable development of rural economies through industrial revitalization and capital inflows. This dynamic substantially strengthens urban–rural coordination and social stability [17].

Overall, their entrepreneurial activities and capital investments enhance household economies and advance regional economic development and agricultural modernization, ultimately fostering shared prosperity [12]. However, existing studies on the behavior of rural migrant workers returning to their hometowns have mainly explored the impact of returning migrant workers on the rural socio-economic structure from the perspective of the effective allocation of labor resources. Under the current system, it is extremely important to achieve the effective allocation of rural land resources in the process of promoting rural revitalization, especially in the context of massive rural labor mobility and rapid urbanization, as the transfer of agricultural land has become a key issue for the rural economy. Statistics show that, in 2004, China’s rural contracted land transfer area was only 0.58 billion mu, and, by 2022, the transfer of family-contracted arable land area has exceeded 532 million mu. However, the growth rate of agricultural land transfer has shown a clear slowdown trend; the average annual growth rate of agricultural land transfer in 2006–2009 was 38.88 percent, and, in 2010–2016, it dropped to 16.64 percent. In 2020, the proportion of farmers operating arable land below 30 acres was as high as 95.8 percent, and the proportion of farmers with a scale of more than 50 acres accounted for only 1.7 percent. This shows that the actual effect of land transfer has not met expectations, and the effective promotion of the transfer of rural land in China needs to be further explored.

Scholars at home and abroad have also conducted extensive research on agricultural land transfer but mainly examined the influencing factors of agricultural land transfer from three perspectives: institutional, internal and external factors. Moreover, farmers with greater resource endowments tend to expand their operational scale, making them more likely to transfer land [18]. Individual characteristics also influence transfer decisions, with studies showing that farmers who are younger and more educated are less inclined to transfer their land out [19]. External factors also play a crucial role in farmland transfer. Climate change, particularly the rise in extreme weather events, significantly affects transfer behavior, as farmers may transfer land to mitigate uncertainty [20,21]. Additionally, collective organizations, agricultural value chains, etc., help regulate transfer behavior and facilitate land transactions [22,23]. Improved public infrastructure and social services lower transfer costs and substantially enhance farmers’ ability to engage in land transfer [22,24].

Although a few scholars have explored the impact of labor mobility on the willingness and mode of land transfer, arguing that dynamic labor mobility alters transfer patterns [25], proves efficiency and scale [26], and had a lasting impact on land intensification and large-scale operations, studies that explicitly examine how returning migrant workers affect the transfer of agricultural land from the unique perspective of returning migrant workers are scarce, and even fewer studies have been conducted, especially through investment in agricultural machinery, access to credit, and reduction in non-farm employment participation. Moreover, most studies rely on regional samples, limiting their generalizability.

The main contributions of this study are as follows: (1) It focuses on individual farm households, extending the analytical scope to the family level. It systematically explores the role of returning family members in agricultural production, particularly in labor allocation and resource integration. This perspective allows for a comprehensive evaluation of returning migrant workers’ multifaceted impact on farmland transfers, filling gaps in the literature on family-level dynamics. (2) This study conducts an in-depth investigation of the mechanisms through which returning migrant workers stimulate farmland transfers. Unlike the existing literature that focused on a single pathway, this study examines how returning migrant workers promote large-scale agricultural operations through farm machinery purchases, agricultural loans, and reduced non-farm employment. The findings indicate that returning labor complements the existing farm workforce while introducing innovative technology and capital, thereby fueling large-scale agricultural development. Furthermore, this study clarifies how education level, return timing, and return motivation influence farmland transfer and large-scale operations. Returning migrant workers expand land operation scales and enhance agricultural production efficiency, reinforcing their role as a key driver of agrarian modernization. These findings offer more targeted policy recommendations by addressing research gaps concerning the varied impacts of returning migrant workers. (3) This study employs rigorous empirical strategies to ensure the robustness of its findings. The use of propensity score matching (PSM) and instrumental variable (IV) approaches helps mitigate potential endogeneity issues, thereby strengthening the credibility of causal relationships. This methodological rigor enhances the reliability of the findings and provides a valuable reference for future research. (4) Furthermore, utilizing data from the 2018 China Labor Dynamic Survey (CLDS), which is nationally representative, this study offers new empirical evidence on the role of returning migrant workers in the rural economy. By systematically analyzing how they facilitate agricultural land transfers and promote large-scale farming operations, this research not only fills existing gaps in the literature but also provides empirical support for optimizing rural revitalization policies.

2. Policy Context and Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Policy Context

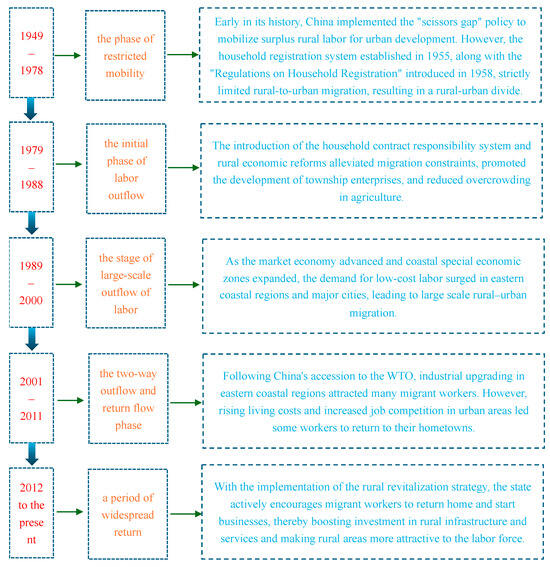

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, migrant labor mobility has undergone five distinct stages of development. Figure 2 illustrates the phases of rural labor mobility and policy changes in China.

Figure 2.

Phases of rural labor mobility and policy changes in China.

2.1.1. 1949–1978: The Restricted Mobility Phase

In the early years of New China, in order to promote the industrialization strategy and maintain urban and rural stability, the State gradually established a strict household registration system. The promulgation of the 1955 Instruction on the Establishment of a Formal Household Registration System and the 1958 Regulations on Household Registration established a household registration system that was bifurcated between urban and rural areas. This system, by restricting the movement of the rural population to the cities, safeguarded the supply of low-cost labor for the development of heavy industry while maintaining urban employment and social order. Strict household registration controls have kept peasants permanently confined to the agricultural sector, with only limited avenues for changing their status through enlistment in the military, further education, or planned labor recruitment. However, with diminishing marginal returns in agriculture and the problem of rural labor surplus becoming increasingly apparent, farmers sought mobility opportunities through various informal means, laying the groundwork for labor migration in the post-reform and opening-up period.

2.1.2. 1979–1988: The Initial Phase of Labor Outflow

The implementation of the household contract responsibility system has reintroduced the family as the basic unit of agricultural production, promoting the transformation of the agricultural business model from collectivized production to a small-farm economy, resulting in a surplus of agricultural labor. Against this background, the State has gradually relaxed restrictions on rural population movement, encouraging the transfer of labor to small towns. By 1998, the number of established towns nationwide had increased to 5.7 times the 1978 figure, absorbing some 150 million rural people [27]. At this stage, labor mobility was characterized by a ‘leave-the-land-but-don’t-leave-the-hometown’ pattern, with surplus rural labor employed mainly in local township enterprises or family workshops [28] and concentrated in economically developed areas with high agricultural productivity. Although the policy allows for small-city work and regional mobility, the scale of migration is still strictly limited, marking the initial exploration of the marketization of rural labor.

2.1.3. 1989–2000: The Large-Scale Labor Outflow Phase

Market-oriented reforms and the development of special economic zones along the coast have created a huge demand for low-cost labor in the eastern part of the country, which has led to a rapid expansion in the scale of cross-regional migration of rural labor and the formation of a wave of migrants who are ‘leaving the land and leaving the countryside’. Migrants mainly flowed to developed areas such as the Pearl River Delta and the Yangtze River Delta, concentrating on labor-intensive industries such as construction, manufacturing, and services, etc. In 1995, the National Conference on the Management of the Floating Population formally acknowledged the phenomenon of labor mobility for the first time and put forward the regulatory principles of ‘adapting to local conditions, strengthening management, and guiding the movement in an orderly manner’. Although the government has attempted to regulate mobility through a series of policies [29], the scale of migration has continued to expand. While this large-scale labor migration has contributed to urban economic growth, it has led to a loss of human capital and a decline in productivity in rural areas, ultimately prompting the government to shift to a policy orientation of protecting the rights and interests of migrant workers.

2.1.4. 2001–2011: The Two-Way Labor Flow Phase

Although rural labor outflows persisted, returning migrant workers gradually increased, giving rise to a bidirectional pattern of simultaneous labor outflows and returns. Following China’s WTO accession, industries in the eastern coastal regions upgraded, resulting in tiered labor mobility that redirected migrant workers into higher-value jobs in the construction, manufacturing, and service sectors. However, rising living costs and fierce job competition in these coastal areas prompted some migrants to return home or seek opportunities further inland. Additionally, the industrial gradient transfer bolstered central and western regions, enhancing their capacity to absorb returning laborers. This trend was exacerbated by the 2008 financial crisis, which led to drastic order reductions in export-oriented enterprises, resulting in widespread job losses and a surge in returning migrant workers [29]. A 2009 National Bureau of Statistics survey estimated that, by late 2008, approximately 70 million individuals had returned home, with 20% remaining permanently (Source: National Statistical Office). This “two-way flow” helped alleviate urban employment pressures, stimulated rural economic growth, facilitated urban–rural resource reallocation, and laid the foundation for sustainable rural development.

2.1.5. 2012–Present: A Period of Widespread Returns

Since 2012, China’s rural revitalization strategy and urban–rural integration policies have stimulated returning migrant workers through enhanced rural infrastructure and public services. The establishment of 341 rural entrepreneurship pilot counties (2016–2017) (Source of data: Circular on the Pilot Work of Supporting the Return of Migrant Workers and Others to Their Hometowns to Start Businesses in the Context of New Urbanization (Development and Reform Employment [2015] No. 2811) significantly improved employment opportunities in central/western regions, resulting in 22.8% returning migrant workers by 2017, with over 70% migrants preferring local employment (Data source: nhc. (2017). China Migrant Population Development Report 2017. Beijing: China Population Press). As China’s economic growth slows, urban job demand continues to outpace supply, and challenges such as rising living costs, stagnant wages, and the rigid dual hukou system exert increasing pressure on migrant workers, further accelerating returning migrant worker trends [30].

2.2. Theoretical Analysis

2.2.1. Human Capital, Return of Migrant Workers, and Large-Scale Farmland Management

According to Schultz’s hypothesis, human capital accumulation is essential for transitioning from traditional to modern agriculture. Only farmers who have mastered modern agricultural production technology, relevant management experience, and competitive advantages in farm operations can be transformed into large-scale operators through farmland transfer [18]. Among the many human capital investment strategies, returning migrant workers play a particularly important role. Returning migrant workers are able to bring valuable urban work experience, professional skills, and financial capital to their hometowns [17]. Unlike ordinary left-behind farmers, returnee farmers, influenced by their urban life and work experience, have unique advantages regarding accepting and applying advanced agricultural technologies, information collection and processing, and management experience [18,31]. It can be seen that, after receiving the baptism of modern civilization and marketization in the towns and cities, the returning farmers who have gained the accumulation of nonagricultural income may no longer stick to the traditional small-scale operation mode but tend to expand the scale of operation by transferring the land with the capital accumulated during the period of working in order to obtain higher remuneration for the scale of agriculture.

Compared to farmers who have never migrated, returning migrant workers are more inclined to invest more in modern agricultural production technologies [32], more capable of adopting and disseminating, by virtue of their accumulated financial capital, good market sense and advanced trading capabilities [31], and are more willing to participate in the agricultural land transfer process. In contrast, non-migratory farmers prioritize production stability over expansion. Building on these insights, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1:

Returning migrant workers increase farm households’ demand for land transfer and promote farmland expansions.

2.2.2. The Return of Migrant Workers, the Scale of Farmland Management, and Mechanization Replacing Labor

According to the theory of exogenous progress, introducing and promoting external scientific and technological advancements—such as new mechanical technologies—is crucial for transforming agricultural production methods [33]. Compared to traditional farming, machinery serves as a fundamental modern agricultural technology. Returning migrant workers often engage in diverse industries and positions, which enhances their capacity to learn and adapt to novel circumstances [4]. Upon returning, the non-farming skills they acquire in urban settings also positively influence their ability to learn agricultural production techniques [5]. Consequently, compared to those who never left, returning migrant workers are more likely to adopt modern agricultural machinery, replacing traditional manual or animal labor [34]. As a specialized asset, agricultural machinery targets specific production tasks but is constrained by seasonality. These factors often reduce utilization efficiency, leading to investment lock-ins and sunk costs. Under relatively adequate labor supply conditions, the probability of farmers expanding the scale of their land operations to increase household income will rise [35]. Moreover, whether passive or active return, the fact remains that migrant workers have lost non-farm employment opportunities in the cities. Upon return, they naturally reconnect spatially with agricultural production, which means that the probability that they will engage in agricultural production upon return increases.

Therefore, returning migrant workers typically transfer land to expand their operational scale, enhance machinery utilization efficiency, and achieve a better match between land size and specialized equipment investments [32]. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

Returning migrant workers expand farmland operations through mechanization, replacing labor.

2.2.3. The Return of Migrant Workers, the Scale of Farmland Operations, and Productive Agricultural Lending

The larger the scale of operation of agricultural land, the more farmers need to invest in seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, and other means of agricultural production. Farmers need to add additional funds to the original production base to purchase the means of production needed to expand the land area [4], thus creating a demand for capital by farmers. Farmers’ production capital originates from two principal sources: wealth accumulated through household business and wage income and capital acquired through formal or informal borrowing [36]. When farmers lack sufficient funds for large-scale operations, those with financing capabilities can secure credit support through the appropriate market channels. Evidence suggests that credit access facilitates agricultural investment and encourages farmers to transfer land [37]. Additionally, shaped by the city’s contractual and impersonal social relations, returning migrant workers often exhibit higher financial literacy and a stronger entrepreneurial mindset [38]. As a result, they have greater potential for achieving higher investment returns. Consequently, profit-oriented financial institutions are more inclined to support returning migrant workers, providing them with tremendous opportunities to expand operations through agricultural production loans [34]. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3:

Returning migrant workers indirectly promote farmland expansion through agricultural production loans.

2.2.4. Returning Migrant Workers, Farmland Scale, and Non-Farm Participation

The outflow of prime working-age men and women can reduce both the quantity and quality of family farm labor, increase household exit rates and farmland outflows, and negatively impact agricultural production [39]. From the supply side, the off-farm transfer of agricultural labor has indeed changed the relationship between agriculture and land, providing land for large-scale production [36]. According to data from the China Household Finance Survey in 2015 and 2017, no one was willing to lease land, which was the second most important reason that farmers did not lease their land (the first being self-farming). Among them, 10.93 percent of the farmers who did not lease their land in 2015 did so because no one was willing to take the lease, while this proportion rose to 14.96 percent in 2017.

As more household members participate in non-farm work, and farm income’s share of total household income drops, agriculture’s diminishing significance leads farm households to reduce their inputs in agricultural production [4]. Consequently, they are less inclined to invest in agriculture, adopt advanced production technologies, or expand farmland operations. Due to the limited availability of family labor, when some family members engage in agricultural production, their participation in non-agricultural activities inevitably decreases [8]. The return of migrant workers directly impacts household agricultural production by increasing the available labor force, thereby altering the previously “balanced” human–land allocation that existed in their absence. To prevent excessive labor input per unit of land and to pursue higher returns from agricultural operations, it is reasonable to speculate that returning migrant workers will move beyond traditional small-scale, decentralized farming. Instead, they are likely to expand their agricultural operations by transferring land, leveraging the capital they accumulated during their period of off-farm employment. It is important to note that this paper is concerned with the moderate scale of agricultural operations, which, at its core refers to the scale of agricultural production based on the moderate scale of land.

Therefore, when migrant workers return to farming and reduce non-farm participation, the relative importance of agriculture grows within households, increasing their focus on farming and boosting their willingness to invest [36]. Consequently, they have become more inclined to purchase agricultural equipment, upgrade production technology, and cultivate additional acreage, thereby promoting farmland expansion [32]. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4:

Returning migrant workers indirectly foster farmland expansion by reducing non-farm activities.

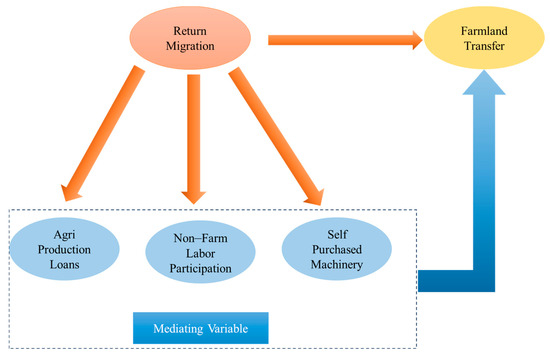

Figure 3 illustrates the theoretical framework diagram of this study.

Figure 3.

Theoretical framework diagram.

3. Research Design

3.1. Data Sources

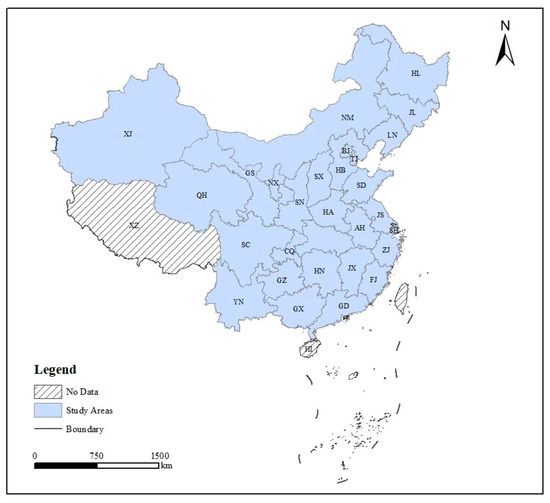

The data for this study were derived from the CLDS, a large-scale longitudinal survey characterized by broad coverage and an interdisciplinary approach. The CLDS targets working-age individuals (15–64 years) and examines the status and dynamics of the labor force in education, employment, labor rights, occupational mobility, safety and health, job satisfaction, and overall well-being. Additionally, the survey includes information on the political, economic, and social development of the communities where the respondents lived, as well as household demographics, property and income, consumption patterns, charitable donations, rural production, land use, and other relevant domains. In terms of representativeness, the CLDS spans 29 provinces and municipalities (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, Tibet, and Hainan, seen in Figure 4) and encompasses over 400 communities, 14,000 households, and 18,000 individual labor force participants. It ensures nationwide coverage and uniquely represents the eastern, central, and western regions of Guangdong Province and the Pearl River Delta. The CLDS employs a rigorous scientific sampling design, specifically utilizing a multi-stage, multilevel probability sampling approach proportionate to labor force size. Moreover, the CLDS is the first in China to implement a rotating sample design, randomly splitting the sample into four segments. Each segment is followed for four consecutive rounds (six years), after which it is withdrawn from the survey and replaced with a new rotating sample. This innovative framework effectively adapts to China’s rapidly evolving socio-economic landscape and leverages the advantages of cross-sectional surveys to maintain data timeliness and stability. The 2018 CLDS data are scientifically robust and nationally representative, owing to the rigorous sampling methods and broad coverage described above. These attributes provide credible empirical support for this study and enhance its validity and generalizability. To meet this study’s requirements, we excluded nonagricultural households and samples with ambiguous responses or missing values, ultimately retaining 622 farming households engaged in agricultural production. The observed sample size varies across models during the empirical analysis because certain variables contain missing data.

Figure 4.

Sample distribution map in China (Note: This map is based on the standard map No. GS (2024) 0650 downloaded from the Standard Map Service website of the Ministry of Natural Resources. The base map boundary is not modified).

3.2. Variable Settings

3.2.1. Explained Variables

The core aim of agricultural modernization is to enhance agricultural productivity. Land transfer is an effective way to mitigate land abandonment, improve land-use efficiency, and optimize factor allocation and marginal output [40]. Drawing on Jian and Biliang [36], this study adopts “whether the household transfers-in farmland” as a measurement criterion. Therefore, this study uses “whether a household transfers-in farmland” as the explanatory variable to determine if farmers have expanded their operational scale via land transfer. Based on the 2018 household questionnaire of the CLDS, land transfer refers to a household acquiring others’ land through rental, substitute farming, or similar arrangements. This binary variable takes the value of one if a household reports having transferred land and zero otherwise. Using land transfer behavior as the focal measure directly captures households’ actual participation in land transactions and shifts in operational scales. This approach has been widely adopted in land transfer research. Moreover, this indicator can be effectively integrated with explanatory and control variables, thereby providing insights into farmers’ decision-making logic and factors influencing land transfers.

3.2.2. Explanatory Variables

The explanatory variables in this study were derived from the 2018 CLDS. They were selected based on responses to explicit survey questions to ensure both scientific rigor and variable relevance. Specifically, the question “Do you have the experience of going out to work (moving across counties/townships for more than half a year)?” identified whether the household head or farmer had worked away from home, thus defining the sample’s scope of work experience. The question “Do you plan to return to your hometown?” identifies those who intend to return and screen potential returnees, and “Is your current occupation agricultural-related?” confirmed that the sample engages in agricultural activities, thus determining the returnees’ participation in farming. By logically screening and cross-verifying these responses, this study ensured the accuracy of the explanatory variables and the reliability of the data. Since this study examines how returning migrant workers affect agricultural production, “return” was conceptualized not only as spatial relocation (i.e., returning home) but also in terms of the nature of work (i.e., whether they are engaged in agriculture). Accordingly, drawing on prior research [9,41], this study employs “migrant return farmhouse” and “head return farm” as key binary explanatory variables (coded 0 or 1). Here, “migrant return farmhouse” indicates whether any household member returned home for agricultural production, whereas “head return farm” denotes whether the household head specifically returned to their domicile to farm. The household head was selected as an indicator because they hold a dominant decision-making position and primarily oversee the family’s agricultural production and management.

3.2.3. Control Variables

Drawing on prior studies [42], this study identifies control variables at three primary levels: household head, family, and village characteristics. Household head characteristics include age, gender, education level (assigned by the highest education attained among the sampled individuals), health status (measured via self-reported well-being), and political status. The family-level variables included average health status, average education level, and household machinery condition (log-transformed value of farm machinery). Village-level characteristics included mechanized services, topography, and location.

3.2.4. Mechanism Variables

Drawing on previous research [43], this study designates “mechanization replacing labor”, “nonfarm employment ratio”, “nonfarm economic status” and “agri production loans” as mediating variables to examine how returning migrant workers affect large-scale agricultural operations. Specifically, “mechanization to replace labor” captures a household’s strategic decision to substitute labor with mechanized production. Both “nonfarm employment ratio” and “nonfarm economic status” measure the impact of nonfarm participation on farmland transfer through changes in household human capital input and income composition. Additionally, “agricultural production loans” indicate whether a farm household obtains credit for production, thereby illuminating how capital supply fosters large-scale farmland management. Descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of variables and descriptive statistics.

3.3. Model Selection

As this study uses farmland transfer by returning migrant workers as a proxy for large-scale operations, we employ a Probit model to examine how returning migrant workers influence farmers’ decisions to transfer land.

where denotes a dummy variable for whether transfers to farmland; is a binary dummy variable for the return of migrant workers and the head of household to farming; is a variable for the characteristics of the head of the farm household, family, and village, including age, gender, education_level, hh_political_statuss, health_status, avg_health_status, avg_education_level, machinery_condition, mechanized_services, village-topography, and location; is an error term; is a constant term; and is a coefficient to be estimated.

Since rural labor returns do not occur randomly, they are shaped by a combination of individual, family, and village-level factors. For example, family events such as caring for children and the elderly significantly drive rural laborers to return home, leading to self-selected return behavior. In order to mitigate self-selection bias, this study follows previous studies [10,44] and adopts PSM under the ‘counterfactual framework’. In this paper, households where the head of the household (or any member of the household) returns home to work on the farm are designated as the experimental group, and households where no rural laborers return to their home villages are designated as the control group. The model is as follows:

where denotes the sample household number; is a binary dummy variable for the return of migrant workers and the head of household to farming. or can be expressed as ATE, which means that a sample of households with covariate characteristics was randomly selected to have the average treatment effect of the impact of returning migrant workers’ households on the transfer of agricultural land; ATT denotes that a sample with returning migrant workers’ households with covariate characteristics was randomly selected to have the average treatment effect of returning migrant workers on the average treatment effect of the impact of agricultural land transfer ATE, set as follows:

Next, this study will continue to use the instrumental variable approach to further address the potential endogeneity issue by adopting a model to construct a decision-making policy for the first stage of migrant workers returning to farming, set as follows:

Included among these are unobserved latent variables in the return of migrant workers to agriculture. This variable needs to be estimated indirectly from other variables. are the observable status of decision making by migrant workers to return to farming, i.e., whether they choose to return to farming in reality or not. is an instrumental variable indicating the number of migrant workers returning to farming, i.e., the number of people returning to farming in the same village, denoting a set of control variables that may influence the decision of migrant workers to return to farming.

The second stage of the agricultural land transfer decision equation is as follows:

Among them, demonstrate the predicted values estimated from the equations in the first stage.

Descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Problem-solving model selection.

4. Result Analysis

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

Table 3 presents the benchmark regression results on how returning migrant workers influence farm households’ operational scales. In models (1)–(4), where “migrant return farmhouse” is the explanatory variable, the marginal effect is 0.1137, indicating that returning migrant workers raise the probability of farmland transfer by farm households at the 1% significance level. In models (5)–(8), where “head return farm” is used as the explanatory variable, the marginal effect is 0.1197, suggesting that household heads returning to farming increase the farmland operation scale at the 1% significance level. These benchmark findings confirm H1, indicating that returning migrant workers address agricultural labor shortages while promoting large-scale farm operations. This process not only plays a pivotal role in revitalizing the rural economy but also safeguards national food security and optimizes agricultural structures, thus infusing more incredible momentum into agricultural scaling and rural modernization and aiding the “Three Rural Areas” initiative in progressing toward high-quality development. This conclusion aligns with those of Jiaojiao et al. [45], who also observed that returning migrant workers facilitate the expansion of agricultural land transfer.

Table 3.

Impact of returning migrant workers on the scale of farmland management of farm households: benchmark regression.

4.2. Counterfactual Framework Analysis

The effect of returning migrant workers on land transfer-in and farmland-scale operations may be influenced by unobserved factors that simultaneously affect farm household operational decisions and the return choices of migrant workers. This would maybe lead to a certain degree of self-selection bias among returning migrant workers.

To mitigate the bias from self-selection, this study employs PSM under the “counterfactual framework”. Based on the control variables in Table 1, we designate households in which the head (or any family member) returned to farming as the treatment group and those without returning migrant workers as the control group. We then use nearest-neighbor, radius, and kernel matching to estimate the average treatment effect of returning migrant workers. Table 4 indicates that results remain broadly consistent across different matching methods: returning migrant workers significantly promote farmland scaling among farm households at the 1% level. Compared with the benchmark regression coefficients of 0.3847 (migrant return farmhouse) and 0.4415 (head return farm), the PSM estimates are lower. These lower coefficients imply that the benchmark regression is overestimated. However, employing PSM effectively mitigates the self-selection bias, enhancing the robustness of our findings. Table 4 also shows the minor differences among the matching methods for specific estimates. However, the overall conclusion remains consistent: returning migrant workers are more likely to transfer farmland and expand their operational scale than non-returnees. This finding further confirms the consistency of the conclusions of this study.

Table 4.

Impact of migrant workers’ return and farmers’ farmland scale-up: propensity score matching.

The main reasons for the return of migrant workers may be based on the following three aspects: Fist, since 2008, accelerated industrial relocation and restructuring have increased employment opportunities in central and western regions, attracting many migrant workers back to their hometowns. Second, several factors contribute to this return, including persistently high housing prices, rising urban living costs, unequal access to public services, and emotional ties to home. Finally, family events such as caring for children and older people significantly drive rural migrant laborers’ returns, resulting in self-selective return behaviors.

Regardless of whether their return is voluntary or forced, migrant workers inevitably lose non-farm employment opportunities in cities. Upon returning, they naturally reconnect with agricultural production, increasing the likelihood of their engagement in farming activities.

4.3. Endogenous Discussions

To address potential endogeneity issues, this study further employed an instrumental variable (IV) approach in order to reduce estimation bias.

This study employs a two-stage least squares (2SLS) model for re-estimation to address the endogeneity arising from omitted variables. Concerning IVs, this study uses a clustering-based approach, drawing on established methodologies [45]. The IV is the number of individuals returning to farming in the same village (excluding respondents), which captures the extent of migrant workers’ returns. This variable is highly correlated with farmers’ returns to farming and meets the correlation conditions for IVs. Simultaneously, the variable satisfies the exclusion restriction, as it only affects farmers’ return decisions by influencing their return decisions rather than directly affecting farmland transfer behavior. Additionally, the IV is independent of the error term, ensuring its homogeneity, thus effectively mitigating the endogeneity problem and providing a reliable basis for causal inference. In the first-stage IV regression, the “number of individuals returning to the same village” coefficients are positive and significant at 1%, indicating a strong correlation with the household and household head return. This validates the instrumental variables. The first-stage F-statistic exceeds 10, thus satisfying the IV validity criteria. Table 5 reveals that the baseline estimates overstate the effect of returning migrant laborers on farmland transfer and operational scale. After accounting for endogeneity, returning migrant labor still facilitates farmland transfer at the 10% level, underscoring the reliable of these findings.

Table 5.

Impact of return of migrant workers and farmland scale-up of farm households: instrumental variables.

4.4. Robustness Checks

This paper mainly tested the samples by the substitution of explanatory variables and the replacement of measurement models to verify the robustness of the estimated results.

4.4.1. Substitution of Explanatory Variables

The increasing number of people returning to agricultural work partially alleviates farm labor shortages, significantly promotes the expansion of farming operations, and enhances agrarian production efficiency. In this study, we employ a variable replacement approach for the robustness test, use the 2SLS model, and, following Jian and Biliang [36], treat “the number of people returning to work in the same village” as the explanatory variable for “farmland transfer”. As shown in Table 6, an increase in the number of people returning to the same village contributes significantly to farmland transfer at the 10% significance level, indicating that the positive effect of returning migrant workers on the farmland transfer-in is robust.

Table 6.

Replacement of explanatory variables.

4.4.2. Replacement of Measurement Models

Drawing on the relevant literature [5,47], this study employs Logit and Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) models for robustness testing. As the cumulative distribution function of the Logit model has a closed-form expression, the difference between the Logit and Probit distributions is negligible when the sample size is sufficiently large. Binary variables can be treated as continuous. The results in Table 7 indicate that replacing the Probit model with either the Logit or the OLS models for robustness testing supports the conclusion that returning migrant workers promote agricultural land transfers. This finding further verifies the accuracy and reliability of the benchmark regression results of this study.

Table 7.

Replacement of measurement models.

4.5. Further Analysis: Farmland Scale Expansion

This study draws on previous theoretical support and the relevant literature to identify the mediating variables that clarify how the core explanatory variables operate within the proposed channel before constructing the mediation effect model. It then employs a three-step mediation analysis to conduct statistical tests. The aim is to further analyze the ways in which returning migrant workers promote the scaling up of agricultural land when they promote land transfer-in.

This paper argues that returning migrant workers facilitate large-scale agricultural operations through three primary paths: investing in agricultural machinery to substitute for labor, increasing access to agricultural production loans, and reducing engagement in non-farm participation. The results in Table 8 indicate that the pathways of returning migrant workers are scaling up farmland. Among them, Panel A demonstrates the Pathways of Action for migrant return farmhouse, Panel B demonstrates the Pathways of Action for head return farm.

Table 8.

The pathways of returning migrant workers in scaling up farmland.

4.5.1. The Pathway of Mechanization Replacing Labor

Purchasing farm machinery offers vital support for returning migrant workers, ensuring secure agricultural production and enabling mechanization to expand the scale of farmland. Studies indicate that returning migrant workers bring back capital and skills while advancing agricultural mechanization through farm machinery purchases [5,33]. Such technological inputs mitigate labor shortages and inefficiencies in traditional agriculture, laying the groundwork for large-scale operations. Purchasing personal farm machinery as a capital-intensive input lowers per-unit production costs and motivates returning migrant workers to increase their operational scale through farmland transfer, facilitating efficient agricultural resource integration [31,32]. Collectively, these points underscore the pivotal role of returning labor in advancing agricultural modernization. A mediating effect of farm machinery purchases is confirmed: the “returning migrant workers → mechanization replacing labor → farmland transfer-in” pathway holds, validating research H2. Qian et al. [48] noted that greater ownership of farm machinery strengthens farmers’ inclination to lease land and increases their incentive for scale expansion.

4.5.2. The Pathway of Increased Agricultural Production Loans

As an intermediary variable, agriculturally productive loans provide farmers with essential financial support, enabling investments in modern farm technologies and equipment. These investments enhance farmers’ production capacity, alleviate capital constraints, and incentivize them to acquire additional land through transfers, thereby increasing the operational scale. Studies indicate that returning migrant workers boost household labor reserves through accumulated capital and experience and elevate financial literacy and loan accessibility [34,38]. By backing farmers’ investments in mechanized equipment, land transfer, and production technology upgrades, agriculturally productive loans effectively lower the financial barriers to large-scale operations, offering a critical impetus for agricultural resource integration and modernization [32,37]. This financial support encourages migrant workers to return to large-scale agricultural operations. Overall, agricultural production loans mediate between returning migrant workers and large-scale operations, confirming the pathway “returning migrant workers → increased agricultural production loans → large-scale agricultural operations” and validating H3. This conclusion aligns with those of Yu et al. [49] and Zhao [34], who suggested that returning migrant workers are more likely to obtain credit, thereby raising both the likelihood of land transfer participation and future intentions. Furthermore, increased access to credit contributes to the expansion [49].

4.5.3. The Pathway of Reduced Non-Farm Participation

Before migrant workers returned to agriculture, off-farm employment provided families with a stable income. However, due to the limited availability of labor, it also led to a shortage of manpower for agricultural production. And those with higher non-farm earnings tend to transfer their land, gradually withdrawing from agriculture and lowering their farmland demand. Additionally, non-farm participation lowers farmers’ demand for farmland resources, while transferring out land raises non-farm labor productivity. Moreover, as households engage in non-farm activities for extended periods, both the likelihood and scale of farmland transfer-out increase [50]. Once migrant workers return, family labor is freed from non-farm employment and can focus more on agricultural production, thus easing labor shortages [34]. This transition heightens households’ emphasis on farming inputs and boosts their demand for farmland transfer and large-scale operations while lowering agricultural labor costs and directly supporting large-scale production [32,39]. Second, through resource reallocation, returning migrant workers diminish the dominance of non-farm activities by reinstating agriculture as the primary income source. This shift in non-farm economic status compels farmers to allocate more capital and effort to agricultural production, thereby increasing the operational scale through farmland transfer [32,33]. Overall, non-farm participation mediates returning migrant workers and large-scale operations, confirming the pathway “returning migrant workers → reduced non-farm participation → large-scale operations” and supporting H4. This aligns with Zhao [34], who contended that returning migrant workers boost the agricultural labor force while reducing non-farm participation. Moreover, our findings resonate with those of Xie and Lu [51] and Che [52], indicating that greater non-farm participation, spurred by migrant outmigration, encourages land outflow and deters inflow. However, returning migrant workers reverse this pattern.

4.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.6.1. Can Age of Returning Migrant Workers Impact Farmland Transfer

This section presents a heterogeneity analysis of returning migrant workers across age groups. Differences in physical capacity, cognitive skills, and production habits among age cohorts may influence agricultural business decisions in distinct ways. Drawing on Jian and Biliang [36] and recognizing 60 years old as a critical retirement threshold in China, we classify returning migrant workers aged 60 or above as “old-aged” and those under 60 as “middle-aged and young-aged”. We then compare how these age groups affect agricultural land transfers. As shown in Table 9, the return of migrant workers under the age of 60 years significantly facilitates farmland transfer at the 5% significance level. In contrast, migrant workers aged 60 years or older appear to hinder large-scale farmland operations. A plausible explanation is that young and middle-aged returnees possess more muscular physical stamina and adaptability than older returnees. Additionally, they are more receptive to modern agricultural technology and large-scale management practices. These findings are consistent with those of Zhang et al. [20], who reported a negative correlation between farmer age and land transfer behavior, indicating that older-age farmers are less likely to engage in farmland transfers, particularly for croplands.

Table 9.

Impact of the return of migrant workers of different age groups on the scale of farmland management.

4.6.2. Can Educational Level of Returning Migrant Workers Influence Farmland Transfer

This section presents a heterogeneity analysis of the educational levels of returning migrant workers. Highly educated returning migrant workers have substantial knowledge, technical skills, managerial abilities, and social capital. Prior research also indicated that higher education levels increase farmers’ willingness to transfer land. Consequently, the impact of returning migrant workers on agricultural land transfers may vary according to different levels of education. Drawing on prior research [19] and considering actual education levels, returning migrant farmworkers with junior-high-level education or higher are classified as “highly educated”. In contrast, those below junior high school are labeled “low educated”. The results in Table 10 indicate that returning migrant farm households and household heads with higher educational levels significantly increase farmland transfers at the 5% level. However, while the coefficient for low-education returning farm households and household heads is positive, it is not statistically significant. This result may stem from the more substantial knowledge base, technical proficiency, and managerial capacity of highly educated farmers, which give them a competitive edge in agricultural production. This conclusion aligns with that of Zhu et al. [19], who suggested that enhancing farmers’ education levels effectively promotes land transfer.

Table 10.

Impact of returning migrant workers with different levels of education on the scale of farmland management.

4.6.3. Can the Timing of Migrant Workers’ Return Affect Farmland Transfer

This section presents a heterogeneity analysis of farmland management outcomes based on migrant workers’ different return periods. Since the 2008 financial crisis, significant numbers of migrant workers have returned to their hometowns. According to a 2009 National Bureau of Statistics survey, approximately 70 million individuals returned to their hometowns by the end of 2008, and 20% of this labor force did not migrate again. Mei and Mingguo [30] reported that the 2008 financial crisis caused a sharp decline in export-oriented enterprises in Southern and Eastern China, creating a shortage of jobs and compelling many migrant workers to return home. This study draws on Mei and Mingguo [30] to investigate the effect of migrant worker return periods on farmland management. We classify migrant workers who returned before 2008 as “early-returning” farm households and those returning in or after 2008 as “recent-returning” farm households. The regression coefficients in Table 11 indicate that, compared with early returning farm households, recent returnees facilitated agricultural land transfer at a 5% significance level for one variable and a 10% significance level for the other. A plausible explanation is that recent returnees have spent more time in urban market-oriented environments, granting them more profound insights into large-scale agricultural operations and stronger resource integration and innovation capacities. This result aligns with Jian and Biliang [36], who reported that recent returnees exert a more substantial influence on farmland transfer and management than early returnees.

Table 11.

Impact of returning migrant workers in different periods on the scale of farmland management.

4.6.4. Can Agricultural Support Services Facilitate Farmland Transfer by Returning Migrant Workers

This section presents a heterogeneity analysis of various agricultural support services. With agrarian modernization, advanced agricultural machinery, characterized by rapid growth, broad application, and efficient production technology, has liberated farmers from labor shortages, low labor quality, and high hiring and supervision costs. Consequently, farmers are increasingly motivated to expand land inflow [17]. Providing agricultural support and benefit services creates favorable market conditions for large-scale operations. These services help expand the scale of farming while reducing agrarian production costs. This study utilizes 2018 CLDS data to examine whether villages provide the following services to support or benefit agriculture: “support agricultural production and help farmers achieve prosperity”. The corresponding research question is whether villages offer support or benefit services to agriculture. According to Table 12, which compares the heterogeneous effects of returning migrant workers on agricultural land transfer under various agricultural support and benefit services, the following conclusions can be drawn: returning migrant workers promote agricultural land transfer and expand farmland operations at a 10% significance level but only in villages that offer these services. This outcome is primarily attributable to the service-induced optimization of production factors, reduced production and transaction costs, and a favorable external environment for large-scale land operations. Similar findings were reported by Su et al. [25], who observed that custodianship services for farmland can effectively facilitate large-scale farmland management.

Table 12.

Impact of return of migrant workers on the scale of farmland operations of farm households under different scenarios of farm support and agricultural services.

4.6.5. Can the Return of Migrant Workers to Farming Be the Primary Driver of Large-Scale Agricultural Operations

Previous studies have indicated that returning migrant workers significantly and positively influence farmland transfer and the expansion of farmland scale. However, farmland-scale expansion does not necessarily lead to large-scale operation. Considering China’s agricultural context, this study adopts the classification approach proposed by Xu et al. [53]. Specifically, farmland operations smaller than 8 acres are classified as small-scale farming, from 8 (inclusive) to 30 acres as general-scale farming and 30 acres or more as large-scale farming. We also conducted separate regression analyses for each category. The results in Table 13 indicate that returning migrant workers significantly promote farmland transfer on small-scale (less than 8 acres) and medium-scale farms (8–30 acres) at the 5% and 10% significance levels, meaning that returning migrant workers and household heads exert a more pronounced influence on small- and general-scale farm households and can also significantly enhance large-scale farmland operations. However, the effect of establishing large-scale farm households remains insignificant, likely because returning to farming does not fulfill the substantial resource inputs required by large-scale operations. Therefore, compared with other large-scale farmers, returning migrant workers represent a key development focus for moderately large-scale farms in China. This conclusion is consistent with that of Wu et al. [32], who reported that returning migrant workers can significantly expand the scale of agricultural production.

Table 13.

Impact of returning migrant workers on the generation of farm households of different sizes.

4.6.6. Can Returning Migrant Workers Become Efficient Agricultural Businesses

Agricultural land transfer has been demonstrated to significantly increase agricultural land productivity. Consequently, as participants in land transfer, do returning migrant workers also exhibit agricultural land productivity? Drawing on Jian and Biliang [36], this study employs the logged agricultural land productivity as a proxy for production performance to address this question. The results in Table 14 reveal that, when migrant farm workers and household heads return to farming, they significantly increase their agricultural land productivity at the 1% significance level. This finding suggests that returning migrant workers achieve higher agricultural land productivity than stay-at-home farmers, underscoring the pivotal role of the returning labor force in boosting productivity and advancing agricultural modernization. This outcome aligns with that of Shen and Wang [33], who, using quasi-natural experimental data, discovered that returning migrant workers effectively enhance agricultural land productivity by improving the level of mechanization.

Table 14.

Impact of returning migrant workers on agricultural land productivity of farm households.

4.6.7. Can Different Regions Facilitate Farmland Transfer by Returning Migrant Workers

This section presents the role of geographic regions in influencing the facilitation of farmland transfer by returning migrant workers. Drawing from Fan et al. [46], we classify the regions into eastern, central, and western regions. We then compare how these region groups affect agricultural land transfers. As shown in Table 15, the return of migrant workers in the eastern and central regions significantly facilitates farmland transfer at the 5% significance level. In contrast, the results for the return of migrant workers in the western regions were not significant. A possible explanation for these findings is that the eastern and central regions have benefited from more robust rural revitalization policies, greater access to financial resources, and better infrastructure, making these areas more receptive to the modern agricultural practices that returning migrant workers often bring. On the other hand, the western region, with its lower levels of agricultural modernization, may not provide the same level of support for large-scale farmland operations, limiting the potential for farmland transfer by returnees. These findings are consistent with those of Jiaojiao et al. [45] and Kai et al. [35], who reported that, in the east-central region, the return of migrant workers could facilitate the transfer of land.

Table 15.

Impact of region on farmland transfer by returning migrant workers.

5. Discussion

This study provides empirical evidence for rural revitalization policies in China by systematically analyzing the effect of returning migrant workers in promoting land transfer-in and the path of influence on farmland scale. This has certain theoretical significance for the modernization of agriculture in China.

This study has similarities and differences with existing studies on related topics. The empirical results show that the return of migrant workers to farming alleviates the shortage of agricultural labor, supplements household human capital, and facilitates land diversion, which corroborates the findings of Jian and Biliang [36] and Jiaojiao et al. [45]. In addition, this paper argues that the returning migrant workers will return to agricultural production, which is inconsistent with the findings of Wu et al. [32], who concluded that migrant workers tend to be more engaged in non-agricultural employment rather than returning directly to the agricultural sector after return. The primary reason for the inconsistent findings may lie in the differing time points of data collection, which can also reflect the varying phases of economic cycles during which the studies were conducted. Moreover, this study argues that returning migrant farm workers in the east-central region play a more significant role in land diversion than those in the western region. This difference may be attributed to the more challenging operating conditions for agricultural production in the western areas, including access to mechanized agrarian technologies and agricultural loans, which limit the ability of return migrant workers to expand land transfers in these regions.

This study has some limitations that should be noted. On the one hand, this study focuses on the Chinese context, specifically rural China. These findings may not apply to agricultural systems or migration patterns in other regions or countries with different socioeconomic conditions. For instance, in Europe, the coexistence of land purchases and leases has provided an effective way to expand agricultural operations continuously [54]. On the other hand, this study uses data from the 2018 China Labor Dynamic Survey (CLDS) to rely on sectional data, limiting its ability to capture long-term trends in migrant workers’ return behaviors and farmland transfers. Changes in migration patterns and agricultural policies may influence these dynamics. Therefore, future research should use longitudinal data to track the evolving role of returning migrant workers.

It is recommended that future studies use panel data to further identify trends and track the evolution in migrant workers’ return behaviors and farmland transfer. International scholars are also encouraged to explore this topic further in the regional context, to enhance the global body of research on the subject.

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

This study systematically examines migrant workers’ influence on farmland-scale operations and the underlying mechanisms. First, the baseline regression results and multiple robustness checks indicate that migrant workers returning to agriculture significantly promote farmland transfer. Compared with households left behind, returning farm households operate farmland on a considerably larger scale, validating H1. Second, the mechanism analysis reveals that mechanization replacing labor, agricultural production loans, and non-farm participation act as mediators significantly accelerating farmland transfer to returning migrant workers. Specifically, returning migrant workers enhance agricultural mechanization by substituting labor, securing financial support through agricultural loans, and reducing non-farm participation to concentrate on farming activities—measures that collectively foster farmland transfer and confirm H2, H3, and H4. Third, the heterogeneity analysis indicates that the effect of returning migrant farm workers from diverse villages, return periods, education levels, and age groups have varying influences on farmland-scale operations. Notably, returning migrant workers who reside in villages offering agricultural support services, who have returned more recently, possess higher education levels, or belong to middle-aged and younger cohorts demonstrate a stronger propensity to advance farmland-scale operations. Fourth, the fragmentation of land and the decentralized, family-based agricultural model have resulted in a pattern of small-scale, dispersed farming operations in China. Returning migrant workers, influenced by various macroeconomic factors, often possess greater financial resources than stay-behind farmers. This financial advantage enables them to acquire land from those who have left arable land unused or exceeded their productive capacity due to engagement in non-farm employment. Further analysis reveals that returning migrant workers represent a critical development focus for large-scale operations and exhibit higher agricultural land productivity rates than their stay-behind counterparts.

6.2. Policy Recommendations

Drawing on this analysis, this study proposes policy recommendations to effectively harness the positive impact of returning migrant workers on agricultural production and offers empirical support for rural revitalization strategies.

First, the government should strengthen the urban–rural social security system and provide specialized funds and tax incentives to reduce capital barriers for returning migrant workers. Second, it should offer subsidies and low-interest loans to facilitate the acquisition of modern agricultural machinery, particularly high-efficiency tractors and harvesters, while promoting shared machinery platforms at a lower cost. Third, the government should strengthen agricultural financial services by providing tailored low-interest loans, flexible repayment plans, and streamlined loan approvals to enhance migrant workers’ access to financing. Fourth, more investment should be directed toward basic education and vocational training, particularly for modern agricultural technologies and management skills. Finally, policies should prioritize highly educated returning migrant workers by providing farming skills, technical support, and financial aid to facilitate their integration into large-scale agricultural operations. Simultaneously, younger and middle-aged workers should receive advanced equipment training, loans, and subsidies to encourage agriculture investment. Additionally, land-transfer policies should be promoted in regions with well-established agricultural support services tailored to local conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.W. and Y.Z.; methodology: Y.Z.; software: Y.Z.; validation: Y.Z., Y.W. and Z.W.; formal analysis: W.W.; investigation: Z.W.; resources: Z.W.; data curation: Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation: Y.Z.; writing—review and editing: Y.W.; visualization: W.W.; supervision: Y.W.; project administration: Y.W.; funding acquisition: Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Sichuan Province Philosophy Social Sciences Planning Program (grant no. SCJJ23ND222); the Western Rural Revitalization Research Center Project (grant no. WRR202301); and the National College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (grant no. 202410626010).

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study was provided by the Center for Social Science Survey at Sun Yat-Sen University, and raw data can be applied via official email (cssdata@mail.sysu.edu.cn). The Stata code used for this paper is available upon request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Center for Social Science Survey at Sun Yat-Sen University for providing the dataset used in this study. We also acknowledge the support from the Sichuan Province Philosophy Social Sciences Planning Program, the Western Rural Revitalization Research Center Project, and the National College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program. Additionally, the authors would like to express their gratitude to the reviewers for their constructive feedback and suggestions, which helped improve this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TVE | Township and Village Enterprise |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| CLDS | China Labor Dynamic Survey |

References

- Constant, A.F.; Zimmermann, K.F. Circular and repeat migration: Counts of exits and years away from the host country. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2011, 30, 495–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.W.; Fan, C.C. Success or failure: Selectivity and reasons of return migration in Sichuan and Anhui, China. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2006, 5, 939–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaodan, H.; Minkai, D.; Yahong, Z. Return migration and resource allocation in rural revitalization: Based on the micro-level analysis of return migrants’ behavior. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 2, 19–33. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhilei, S.; Jia, W. Migrant worker experience and rural labor force new technology acquisition. J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. 2013, 2, 48–56+159. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xi, C.H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Qu, X. Does migration work experience promote return home for entrepreneurship? The mediation of cognitive ability and the moderation of risk preference. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, A.Z.; Pang, G.; Zeng, G. Entrepreneurial effect of rural return migrants: Evidence from China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1078199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, L. How does migration working experience change farmers’ social capital in rural China? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahba, J. Selection, selection, selection: The impact of return migration. J. Popul. Econ. 2015, 28, 535–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, F. Migrant Workers and the Mystery of China’s High Savings Rate: An Analysis Based on a Search Matching Model. J. Manag. World 2017, 4, 20–31+59+187. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Shen, Z.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Tang, B. Will the situation of Left-Behind children improve when their parents Return? evidence from China. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2024, 164, 107856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junwu, X.; Zhaoxiong, C.; Junjie, W. Return of migrant workers, educational investment in children and intergenerational mobility in China? Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 76, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.Z.; Hu, S.; Zhou, B.; Lv, L.; Sui, X. Entrepreneurship and the formation mechanism of Taobao Villages: Implications for sustainable development in rural areas. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 100, 103030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.G. Research on the linkage mechanism between migrant workers returning home to start businesses and rural industry revitalization based on the combination prediction and dynamic simulation model. Comp. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 1848822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.L.; Jin, Z.Y. Impact of return migration on employment structure: Evidence from rural China. J. Asian Econ. 2024, 91, 101697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Yin, X.; Zheng, X.; Li, W. Lose to win: Entrepreneurship of returned migrants in China. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2017, 58, 341–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Aleman, S.; Gonzalez-Lozano, H. Return migration and self-employment: Evidence from Mexican migrants. J. Lab. Res. 2021, 42, 148–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.; Xiangguang, C.; Yanyan, Z. Can returning to hometown entrepreneurship raise rural residents’ income examination based on the pilot policy of returning to hometown entrepreneurship. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2024, 7, 111–128. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zeng, W.; Liu, Z. Farmer heterogeneity and land transfer decisions based on the dual perspectives of economic endowment and land endowment. Land 2022, 11, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.S.; Wei, C.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, X. Influencing factors of farmers’ land circulation in mountainous Chongqing in China based on A multi-class logistic model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Y. Knowing and doing: The perception of subsidy policy and farmland transfer. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, W.; Xu, G.W. Analysis of the influential factors for changes to land use in China’s Xingwen Global Geopark against a tourism development background. Geocarto Int. 2016, 31, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.R.; Zhao, Q.J. How does the method of farmland transfer affect the “non-grain” of farmland in China? Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1418983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Guo, Y.; Dang, H.; Zhu, J.; Abula, K. The Second-Round Effects of the Agriculture Value Chain on Farmers’ Land Transfer-in: Evidence From the 2019 Land Economy Survey Data of Eleven Provinces in China. Land 2024, 4, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, W.; Wu, K.X.; Du, Y.; Yang, H.F. The Trade-Offs between Supply and Demand Dynamics of Ecosystem Services in the Bay Areas of Metropolitan Regions: A Case Study in Quanzhou, China. Land 2022, 1, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.Q.; Huang, Q.; Meng, Q.; Zang, L.; Xiao, H. Socialized farmland operation—An institutional interpretation of farmland scale management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zheng, W.; Zhong, T. Impact of migrant and returning farmer professionalization on food production diversity. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 94, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistical Office. Sexies: The Rise of Township and Village Enterprises. 1999. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/zt_18555/ztfx/xzg50nxlfxbg/202303/t20230301_1920444.html (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Linfei, S. Surplus of the rural labor force and its way out. Soc. Sci. China 1982, 05, 121–133. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hongyuan, S.; Huabo, H.; Guangming, L. Analysis of policy issues on rural labor mobility. Manag. World 2002, 5, 55–65+87–153. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Mingguo, G. Characterization of migrant workers’ return in the context of financial crisis. Rural. Econ. 2009, 12, 116–119. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huo, C.J.; Chen, L.M. Research on the impact of land circulation on the income gap of rural households: Evidence from CHIP. Land 2021, 10, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]