Abstract

The development of the bioeconomy in the European Union is promoted through various policies. In Greece, however, there is a paucity of research on bioeconomy issues and policies at both the national and regional levels. This study systematically examines the feasibility of developing a bioeconomy blueprint within the context of a geographically isolated and mountainous region. By employing an integrated strategic framework combining sustainable resource management, innovation and participatory governance, the proposed framework emphasizes the transition from conventional, unsustainable economic practices to a contemporary development paradigm underpinned by the tenets of the circular economy and the utilization of local resources. A central tenet of the proposed framework is the enhancement of collaborative endeavors among local stakeholders, academic institutions, and business entities, with the overarching objective being the promotion of cutting-edge technologies and the economic diversification of the region. Concurrently, emphasis is placed on the necessity to establish conducive policies, regulatory frameworks, and financial mechanisms that will facilitate the development of sustainable industries and mitigate the environmental impact. The text emphasizes the importance of human resources development through educational and training programs, ensuring adaptability to the demands of the emerging bioeconomy. The study concludes that, despite the inherent difficulties arising from geographical isolation and limited access to resources, the region has the potential for sustainable development. The region’s capacity for sustainable development is contingent upon the implementation of suitable strategies and the mobilization of investment, which will be instrumental in the establishment of a robust and environmentally sustainable economic model.

1. Introduction

The blueprint for the development of a regional bioeconomy strategy serves as a fundamental component within the governance model, as it facilitates the transition towards a sustainable and resilient economy [1,2,3]. This strategic framework harmonizes local initiatives with overarching national and European policies for the bio-based economy, while concurrently advocating a holistic approach to economic development, environmental management, and social inclusion [4]. Fundamentally, the blueprint functions as a mechanism for strategic planning and policy development [5,6]. It articulates a clear vision and establishes specific objectives and priorities for the effective utilization of biological resources, thereby ensuring that regional policies are aligned with national and European strategies for the bio-based economy [7,8]. This alignment is crucial to exploiting funding opportunities and maximize the impact of bio-based economy initiatives.

A fundamental function of the blueprint is to facilitate sustainable resource management [9,10]. Western Macedonia, a region historically dependent on lignite mining, is undergoing a transition towards more sustainable economic activities [11,12]. The blueprint emphasizes the importance of the sustainable utilization of biological resources, with a particular focus on practices that encourage environmental conservation while catalyzing economic growth. It also promotes the principles of a circular economy, encouraging the minimization and reuse of waste and by-products, thereby reducing the ecological footprint of regional industries. The blueprint’s contribution to supporting local industries in Western Macedonia in the reuse of agricultural by-products or the conversion of organic waste into bioenergy or compost is significant in terms of closing resource cycles and reducing dependence on external inputs, underscoring the significance of economic diversification and innovation as pivotal elements. The blueprint’s strategic objective is to reduce the region’s reliance on lignite by fostering the emergence of bio-based industries [13]. This diversification is vital for economic resilience, providing new opportunities in sectors such as bioenergy, bioproducts, and sustainable agriculture [13]. The transition from a conventional economic model, based on the depletion of natural resources, to the bioeconomy is a complex process that has already commenced in several regions of Europe. Regions such as the Ruhr in Germany, Asturias in Spain, and several regions in Poland are facing similar challenges as Western Macedonia, as they seek to gradually move away from dependence on coal and the fossil fuel industry, adopting alternative forms of development based on sustainability and innovation. The Ruhr region in Germany serves as a prime example of this transition, having successfully transitioned from heavy industry and coal mining to an economy based on knowledge, innovation, and biotechnology [14]. The German strategy, which focuses on funding from national and European programs, has played a pivotal role in this transformation [2,15]. The creation of research and development clusters and the upgrading of the workforce through training programs have also been instrumental in this process [16]. Conversely, the case of Asturias, a former coal-producing region, demonstrates that the success of the transition process hinges on the integration of green growth policies with local specificities [17,18]. The region has invested in bioeconomy sectors such as forestry and sustainable agriculture, while implementing tax incentives to attract investment. Conversely, Poland, which has numerous coal-producing regions, is implementing a gradual transition based on the development of local bioeconomy initiatives, the strengthening of the circular economy, and the linkage of the agricultural sector with the industrial production of sustainable products [19,20]. Alongside this, it is implementing policies to enhance social acceptance of the transition in order to mitigate the social and economic impacts.

The blueprint for Western Macedonia has been shown to function as a catalyst for innovation by encouraging research and development in bio-based technologies [21,22] and fostering an ecosystem conducive to technological progress and entrepreneurship by supporting start-ups [23] and facilitating partnerships between academia, industry, and government [24]. The blueprint also promotes the establishment of partnerships with local agricultural cooperatives for the production of bio-based products. Furthermore, to stimulate innovation, the blueprint supports incubator programs that help bio-based start-ups develop and scale their technologies by fostering collaboration between universities, research institutions, and regional businesses.

Conversely, the blueprint also plays a pivotal role in job creation and skills development [25,26]. As the region undergoes a transition away from lignite mining, there is an increasing demand for new skills and training programs that are tailored to the emerging bio-based industries [27]. The blueprint details initiatives designed to equip the workforce with the necessary skills to thrive in these emerging sectors [28]. This emphasis on education and training is not only a means of enhancing employability, but also of ensuring that the benefits of the transition to the bio-based economy are widely shared, contributing to social stability and economic inclusion [29]. The blueprint’s capacity to catalyze employment creation and skills development is underscored by its proposed collaboration with local technical schools and universities in the design of training programs, with the objective of providing certifications in bio-based domains such as bioprocess engineering and sustainable agriculture practices. Furthermore, the establishment of partnerships with bio-based companies has the potential to offer apprenticeships or internships, thereby providing workers with practical experience [30]. These targeted programs have been meticulously designed to ensure that as Western Macedonia transitions from lignite mining, the local workforce is adequately prepared for new roles, thereby supporting economic inclusion and social stability across the region [27].

Stakeholder engagement represents a further pivotal function of the blueprint, as an effective governance in the transition to the bioeconomy requires the active participation of various stakeholders, including local communities, businesses, research institutions and non-governmental organizations [31,32,33]. The blueprint provides a framework for inclusive decision-making, ensuring that different perspectives are considered when formulating bioeconomy policies. It can facilitate the organization of regular stakeholder forums, wherein representatives of local communities, businesses, research institutions, and NGOs collaborate on the formulation of bioeconomy policy proposals. The establishment of advisory committees comprising these stakeholders is also recommended, with a view to ensuring the ongoing provision of input and feedback on key decisions [34]. This overarching framework is meticulously designed to ensure the integration of diverse perspectives into the decision-making process, thereby enhancing trust and accountability by making stakeholders feel directly involved in the region’s transition to the bioeconomy [35].

The blueprint under discussion identifies financing and the attraction of investment as critical elements. The document identifies potential sources of funding, including European Union (EU) programs, national funds, and private investment, to support bioeconomy projects. Potential sources of support for bioeconomy projects include EU programs such as Horizon Europe and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), and national funds targeting green transition initiatives. The demonstration of strategies to attract private investment, such as tax incentives for biotech-based start-ups, is also outlined. Demonstrating the region’s commitment to sustainable development and highlighting its strategic advantages for bio-based industries are instrumental in attracting the investment necessary to scale up bioeconomy activities. The blueprint also references the sustainable development plans of Western Macedonia, including the Just Transition development plan, which delineates a roadmap for transitioning from lignite dependency while prioritizing bioeconomy. This alignment with both regional and European strategies demonstrates a proactive attitude towards sustainable development, which can be attractive to investors wishing to support green industries [36].

Finally, the bioeconomy blueprint incorporates monitoring and evaluation mechanisms [25,37]. It establishes a framework of benchmarks and indicators, serving as quantifiable metrics to assess the advancement and ramifications of bioeconomy initiatives on economic growth, environmental sustainability, and social well-being. The ongoing monitoring and evaluation process enables the adaptation of strategies and actions, thereby ensuring that the region remains on track to achieve its bioeconomy objectives [38].

The present study aims to address the research gap concerning the absence of a comprehensive strategic framework for the bioeconomy in Western Macedonia. The study aims to address this deficit by proposing a bespoke strategy that is informed by the region’s unique characteristics, including its specific challenges and strengths. Specifically, it explores the potential for leveraging local biological resources, integrating the circular economy, and aligning the bioeconomy with the region’s development priorities. Concurrently, the formulation of policies that can support this transition is emphasized, with particular attention directed towards job creation, innovation development, and investment attraction. The study also identifies the need to strengthen inclusiveness and transparency in the decision-making process, as well as the absence of mechanisms for monitoring and evaluating progress in the bioeconomy. Consequently, the study makes two major contributions: firstly, it offers a theoretical framework and, secondly, it provides practical guidelines that can be applied to strengthen the regional bioeconomy.

The manuscript’s originality lies in its formulation of an integrated bioeconomy development strategy for Western Macedonia, tailored to the region’s specific needs and challenges. Rather than merely adhering to the overarching directives set forth by the European Union or national strategies, the manuscript emphasizes the implementation of policies and practices that are uniquely suited to the region. The manuscript draws upon the region’s historical reliance on lignite mining and the imperative for a transition towards more sustainable and innovative economic activities. The study proposes concrete models of cooperation between local agricultural cooperatives, businesses, universities, and research institutions that enhance the production and application of bio-based technologies. The manuscript’s innovative character is rooted in its integration of theoretical analysis with practical, applied models, a combination that is pivotal to facilitating the transition of Western Macedonia to a sustainable and resilient bioeconomy.

The objective of this study is to formulate an integrated and sustainable framework for the development of the bioeconomy in Western Macedonia. The objective is to provide a framework to guide the region’s strategic transition from a lignite-based economy to a new, sustainable economic model based on the bioeconomy. Concurrently, the objective is to align regional initiatives with European and national bioeconomy policies, ensuring synergies that facilitate access to financial instruments and resources. Furthermore, the study seeks to strengthen the regional economy through job creation and skills development in the workforce. In summary, the strategy provides a roadmap for the implementation of the bioeconomy strategy in Western Macedonia, with the overarching objectives being sustainable development, environmental protection, and improved social well-being.

The present manuscript is comprised of five sections. The first part presents the introduction, in which the context and significance of the study are described. The second part of the manuscript is dedicated to the discussion of the research methodology, encompassing the methods that were employed and a detailed description of the study area. The third part of the manuscript presents the results of the research, while the fourth part includes the discussion, where the findings are interpreted and compared with the relevant literature. Finally, Part 5 presents the conclusions of the study, as well as suggestions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The Region of Western Macedonia is located in the northwestern part of Greece and comprises four Regional Units: Kozani, Kastoria, Grevena, and Florina (Figure 1) [11]. The region’s topography is marked by a pronounced mountainous and semi-mountainous landscape. Its climate is continental, with cold winters and cool summers, influenced by altitude and distance from the sea. Notably, Western Macedonia is the only region in Greece that is not affected by the sea [39].

Figure 1.

Map of Western Macedonia Region. Source: Author’s own creation.

The region’s economy is predominantly reliant on the energy sector, as Western Macedonia is a notable energy center in Greece due to its lignite deposits and power plants. Nevertheless, the transition to a post-lignite era represents a critical issue for the region’s economic development [40]. Concurrently, agriculture and livestock farming represent pivotal sectors within the regional economy [12]. The industrial and craft sector is also of significance, with a particular emphasis on fur production, a traditional activity in the region. Furthermore, the region’s cultural and natural heritage, including its lakes, ski resorts, and historical monuments, has led to an increase in tourism, which has further boosted the economy. The Region of Western Macedonia is currently undergoing an economic transformation with the aim of diversifying its economic base and promoting green growth [41]. Significant emphasis is being placed on the bioeconomy, the circular economy and innovation, with the aim of leveraging European financial instruments and programs.

Western Macedonia has been designated as a region exhibiting emerging innovation levels in accordance with the Regional Innovation Scoreboard 2023 [42]. According to the Regional Development Plan 2021–2025, the region’s GDP per capita in 2019 was 17,900 euros, which is lower than the national average of 20,200 euros and the EU average of 30,000 euros. Furthermore, between 2015 and 2019, the region witnessed a negative GDP per capita growth rate of −0.55%, contrasting with the growth recorded at both the national level (1.28%) and the European level (2.86%) [43].

West Macedonia is the region with the lowest population density in Greece, with 29 inhabitants per square kilometer in 2021, compared to 82 at national level and 118 in the EU. Moreover, West Macedonia exhibits a notably high employment rate in agriculture and mining, standing at 24.7% in 2021. This figure is substantially higher than the national average of 12.9% and the European average of 4.6% [43]. According to the Regional Development Programme 2021–2025, West Macedonia has a relative sufficiency of waste management infrastructure and an effective regional planning system, capable of achieving the ambitious targets of the National Waste Management Plan for 2025 and 2050. The financial requirements are modest and pertain to investments in low-cost infrastructure, with the primary objective being to enhance the source separation system for specific waste categories that are not currently addressed by the prevailing or alternative collection systems [44].

In the context of European, national, and local legislation, there is a notable impact on the economic and societal structure of Western Macedonia. The revised EU waste legislation and the Circular Economy Action Plan promote sustainable resource management, influencing local practices in waste management and production [45]. At the national level, the National Waste Management Plan establishes the overarching framework for waste management, while the Regional Waste Management Plan of Western Macedonia adapts these guidelines to address the specific needs of the region. The influence of these legislative instruments on the regional economy is twofold: first, they encourage investment in waste management infrastructure, and second, they promote the adoption of circular economy practices. Additionally, the EU Bioeconomy Strategy, which emphasizes sustainable and circular management of natural resources, exerts a significant influence on sectors such as agro-industry and food in Western Macedonia, resulting in alterations to production processes and waste management [44]. Consequently, the overarching legislative framework, operating at various levels, significantly influences the development of strategies for sustainable development, economic restructuring, and enhancing the quality of life for the region’s inhabitants.

2.2. Research Methods and Context

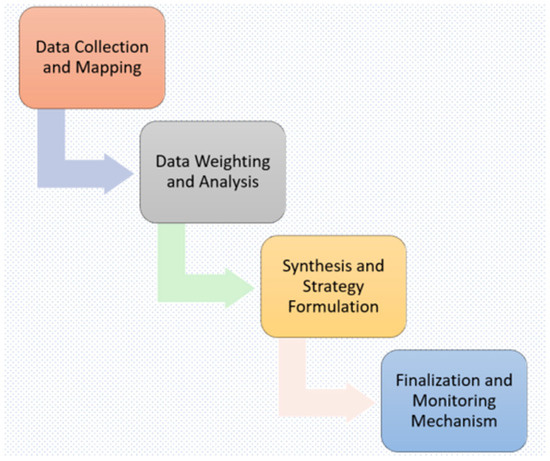

The development of the strategic plan for the bioeconomy in Western Macedonia was based on a multi-methodological approach that combined quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis techniques. The design of the methodology was developed with the aim of developing a holistic strategy, taking into account local challenges, opportunities, and prospects for sustainable development [46,47]. The methodological approach encompassed a multi-stage process, integrating literature review, secondary data analysis, structured interviews with key stakeholders, and participatory policy co-design workshops. Subsequently, a data weighting and analysis process was initiated, utilizing qualitative content analysis, SWOT analysis in conjunction with the Delphi method, and a categorization of stakeholders’ perspectives [48,49]. This process ensured a systematic synthesis of the data, reflecting both local realities and international best practices in the final strategies. The proposed plan was then shaped through a hierarchical decision-making process, which included the initial identification of key priorities, the adaptation of the strategic proposals through feedback from experts and local stakeholders, and the formulation of specific policy interventions based on the feasibility and viability of implementation [50]. Finally, the final plan includes a mechanism for continuous monitoring and evaluation, allowing for dynamic adaptation of the strategies in line with developments in the region and in the wider European bioeconomy policy (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Key stages of the methodological approach. Source: Author’s own creation.

In the context of the BIOMODEL4REGIONS project (Grant Agreement ID: 101060476), CluBE (Bioeconomy and Environment Cluster of Western Macedonia) played a pivotal role in the formulation of the blueprint for the bioeconomy in the region of Western Macedonia. CluBE was centrally involved in the elaboration and formulation of strategies and guidelines related to the bioeconomy with the aim of enhancing sustainability and innovation in the region. CluBE developed bespoke guidelines for key bio-based sectors (agriculture, forestry, waste management) to facilitate sustainable practices and ensure that each sector is aligned with the bioeconomy objectives. Furthermore, CluBE provided recommendations to local policymakers to establish supporting regulations for the bioeconomy [27]. These recommendations encompass incentives for sustainable practices and tax benefits for companies that adopt bio-based processes, thereby ensuring the creation of an enabling environment for the development of the bioeconomy.

The project’s success was significantly influenced by the contributions of representatives from academia, local bio-based enterprises, and regional and local authorities. The active involvement of these stakeholders in the workshops facilitated the collection of invaluable insights and proposals, which were then integrated into the blueprint’s development. Furthermore, the interviews conducted by these representatives have facilitated a more profound understanding of local needs and perspectives, thereby reinforcing the overall project strategy. This collaborative approach is demonstrative of the effectiveness of the strategy and underlines the importance of involving all stakeholders in promoting the bioeconomy in the region.

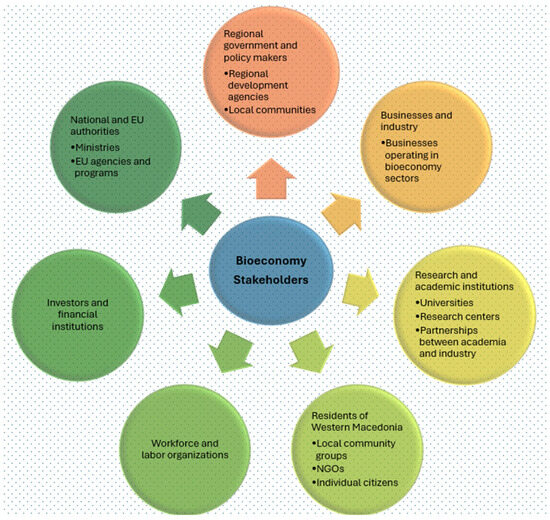

The blueprint for the development of the bioeconomy strategy in Western Macedonia is a key strategic document designed to guide the region in a transformational landscape towards sustainable economic growth. This document has been meticulously crafted to serve a wide range of stakeholders (Figure 3), each of whom plays a critical role in the successful implementation of bioeconomy principles. The blueprint is comprehensive in nature, addressing the multifaceted needs and roles of the aforementioned stakeholders through an integrated and inclusive approach.

Figure 3.

Stakeholders involved in the bioeconomy strategy blueprint. Source: Author’s own creation.

The blueprint has been designed with regional governments and policymakers in mind. These stakeholders are responsible for establishing strategic directions and implementing policies that promote the development of the bioeconomy [22]. A salient feature of the blueprint is the involvement of regional development agencies, local municipalities, and elected officials in this process. The responsibilities of these stakeholders encompass the formulation and enforcement of policies that encourage sustainable practices, the coordination of efforts with national and European agencies to secure the necessary funding, and the continuous monitoring and evaluation of the impact of bioeconomy initiatives [51]. This alignment with broader national and EU strategies is crucial to capitalize on funding opportunities and optimize the effectiveness of bioeconomy projects.

Businesses and industry leaders, given their pivotal role in the adoption and scaling of bio-based technologies and practices, are also key stakeholders [52]. Of particular significance are companies operating within sectors such as agriculture, forestry, bioenergy, food processing, and waste management. By allocating financial resources and embracing bio-based innovations, these companies contribute to economic diversification and resilience. Collaborations with research institutions facilitate the development of novel products and technologies, thus promoting the region’s bioeconomy. Furthermore, businesses contribute significantly to policy development, ensuring that regulations support economic growth and innovation [26].

Research and academic institutions represent a pivotal group targeted by the blueprint. Universities, research centers, and academic institutions play a pivotal role in promoting innovation and technologies in the bioeconomy [53]. Researchers, professors, and students engaged in bioeconomy-related studies contribute through cutting-edge research and development, and these institutions also play a vital role in training the future workforce by offering educational programs that equip students with the skills needed in bio-based industries [54]. Partnerships between academia and industry ensure the transfer and commercialization of new technologies, enhancing the region’s competitive advantage. The blueprint is also designed with local communities and citizens in mind, with the inhabitants of Western Macedonia being directly affected by the economic and environmental changes brought about by the transition to bioeconomy. Local community groups, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and individual citizens are encouraged to participate in public consultations, providing feedback on bioeconomy projects and ensuring that initiatives meet their needs and expectations [55]. By engaging in sustainable practices and supporting local bioeconomy-based businesses, communities play a vital role in the region’s transition. These stakeholders can also benefit from new employment opportunities and an improved quality of life resulting from sustainable economic development [51].

In the context of Western Macedonia’s transition away from lignite mining, workforce and employee organizations assume a pivotal role in the region’s economic transformation [56]. The necessity for new skills and training programs tailored to the bio-based sectors is of paramount importance. Vocational training centers, trade unions, and employment agencies are involved in identifying skills shortages and providing the necessary training. These entities advocate for fair labor practices and the establishment of adequate working conditions, thereby ensuring that the transition to the bioeconomy is socially inclusive. By facilitating the transition of workers from traditional industries to new bio-based sectors, these organizations contribute to the economic resilience and social stability of the region [8].

Investors and financial institutions represent a further key audience for the blue-print. Financial institutions, encompassing banks, venture capitalists, and public and private investment funds, play a pivotal role in providing the capital necessary to support bioeconomy projects [57]. By evaluating the viability and sustainability of investments in bio-based industries, financial institutions contribute to the assurance that projects are financially sound and environmentally sustainable. Their involvement is critical to the expansion of bioeconomy activities and the attraction of further investment, thereby promoting regional economic development.

Finally, national and EU authorities are vital stakeholders in the blueprint. National governmental bodies and EU institutions are responsible for establishing the regulatory frameworks that govern regional bioeconomy initiatives, as well as providing the necessary funding and support [58]. Ministries associated with agriculture, the environment, and economic development, in conjunction with relevant EU agencies and programs, assume a pivotal role in establishing standards and providing incentives [38]. Their support ensures that regional activities are aligned with national sustainability and EU objectives, facilitating a coherent and coordinated approach to bioeconomy development.

3. Results

The blueprint for the development of a strategic bioeconomy in Western Macedonia is a fundamental guide for the region’s transition to a sustainable and resilient economic model. The document is not intended to represent a definitive conclusion but rather to provide a methodical plan that can be followed to create an integrated bioeconomy strategy [59] and to delineate the preliminary steps (Figure 4) required to ensure that Western Macedonia can effectively utilize its biological resources, thereby supporting sustainable growth and regional development.

Figure 4.

Steps towards a strategic bioeconomy. Source: Author’s own creation.

The initial phase entails the refinement of the overarching vision and the undertaking of meticulous planning. This stage is pivotal in establishing specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound objectives that will direct the region’s bioeconomy initiatives. Specifically, a comprehensive assessment of the region’s biological resources, identification of key areas for development, and establishment of clear goals and milestones are required [8,60]. Furthermore, a thorough analysis of the prevailing economic, environmental, and social conditions is imperative to adapt the bioeconomy strategy to the unique characteristics of Western Macedonia. This detailed planning process is instrumental in ensuring that the strategy is both realistic and ambitious, thereby providing a clear roadmap for future actions. The execution of these assessments and the establishment of objectives will be undertaken by regional development agencies, local government, and the university. The financial provision for this initiative will be drawn from Community and national development funds, allocated through the local government budget.

The subsequent stage of the process will entail the further development of collaborative relationships with a diverse array of stakeholders, whose effective engagement is imperative in order to guarantee that a variety of perspectives are incorporated into the bioeconomy strategy [61,62,63]. This will be achieved through the organization of workshops, public consultations, and collaborative platforms where local communities, entrepreneurs, academic institutions, and civil society organizations can contribute their views. Such a participatory approach enhances the legitimacy and effectiveness of the bioeconomy strategy by fostering a sense of ownership and commitment among all stakeholders [64]. In this regard, regional authorities, academic institutions, and local chambers of commerce are poised to play pivotal roles. The financial sustenance for this initiative can be drawn from multiple sources, including local authorities and public-private partnerships.

The subsequent step is the formulation of concrete policies and regulations. The creation of a favorable regulatory framework that supports bio-based businesses, promotes sustainable practices and incentivizes innovation is essential [65]. Key areas that such policies should address include land use, resource management, waste reduction, and environmental protection. The integration of bioeconomy principles into existing regional policies is pivotal in ensuring a coherent approach to sustainable development and aligning regional efforts with national and EU strategies, facilitating a coordinated and effective implementation [66]. The role of regional authorities, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, environmental agencies and legal experts is pivotal in this process, and the funding for its implementation can be drawn from the European Structural and Investment Funds and national funding programs.

The transition to a bioeconomy necessitates a skilled workforce that is equipped with the necessary knowledge and expertise [29]. Investing in education and training programs to develop these skills is imperative, constituting the fourth step in the development of the strategy. Partnerships with universities, vocational training centers, and industry partners are essential for the design and implementation of effective training initiatives. The establishment of local capacity ensures that the workforce is prepared to meet the demands of the emerging bioeconomy, contributing to economic resilience and social stability [67]. The capacity building process enhances employability, while also driving innovation and productivity in the bio-based sectors. The implementation of this step will be undertaken by the university, local businesses, and employment agencies, with funding coming from national and European resources. Securing adequate funding and attracting investment is another necessary step in implementing a comprehensive bioeconomy strategy. Identifying and accessing different sources of funding, including EU programs, national funds, private investment, and public-private partnerships, is essential [68]. The development of appealing investment proposals and the promotion of the region’s commitment to sustainability can assist in attracting investors. Securing financial support for bioeconomy projects is imperative for their successful implementation and scalability, resulting in economic growth and job creation. Regional development agencies, local authorities, business incubators developed within the university and financial institutions can assume the role of securing funding, drawing on private venture capital in addition to European and national resources.

The establishment of monitoring and evaluation mechanisms represents the penultimate step in the process of monitoring progress and assessing the impact of bioeconomy initiatives [7,69,70]. The establishment of a robust system for the collection of data, the measurement of results and the evaluation of the effectiveness of policies and projects allows for continuous improvement [71]. Regular monitoring and evaluation facilitate the implementation of adjustments and improvements, thereby ensuring that the bioeconomy strategy remains dynamic and responsive to changing circumstances. Achieving long-term sustainability goals necessitates continuous learning and adaptation. The responsibility for this work should be assigned to district agencies, the local statistical authority, and independent assessors.

Finally, public awareness and effective communication of the benefits and opportunities of the bioeconomy are important to ensure public support and participation [72]. The development of communication strategies to inform and educate the public about bioeconomy initiatives is pivotal, whilst utilizing diverse media channels, organizing awareness campaigns, and highlighting success stories can foster a positive perception of the bioeconomy [22]. Community participation and support are pivotal to the successful implementation of bioeconomy projects. The implementation of this critical step can be undertaken by both the regional authority and the local media in partnership with PR companies and community organizations, while the financial resources can be provided by private sponsorship from the involved businesses and information campaigns by the regional authority.

Western Macedonia has set its sights on a bioeconomy that is driven by transparency, inclusiveness, and innovation. This vision is comprised of several key elements, each of which has specific strategic objectives and operational goals to ensure its successful implementation. Transparency is identified as a fundamental principle of this vision, with the establishment of open data platforms intended for the real-time monitoring of environmentally sustainable production and the facilitation of public access to environmental impact reports [73,74]. In addition, transparent communication channels between government, business, and citizens will be developed. Participation is another crucial element, promoting the active involvement of all social groups in the bioeconomy [75]. The region aims to ensure equitable access to resources and benefits from eco-friendly initiatives by developing tailored programs to engage marginalized communities. Innovation will be promoted through research and development of sustainable technologies, encouraging public-private partnerships and providing incentives for start-ups and SMEs in the bioeconomy [76,77]. The region will also implement clear and accessible reward systems for environmentally friendly practices, including tax benefits and grants for green initiatives, as well as recognition of environmentally friendly achievements.

The establishment of long-term commitment and cooperation between stakeholders is to be facilitated by the formation of strong partnerships between government, industry, academia, and civil society. Furthermore, sustained funding and political support for bioeconomy initiatives is to be ensured, thus promoting a culture of continuous improvement and adaptation [78,79]. Finally, the development of specific training programs is to be initiated, with the objective of enabling all citizens of the Region of Western Macedonia to participate fully in the bioeconomy. These programs will facilitate access to technology and digital tools, with the aim of encouraging participation through digital platforms.

By focusing on these strategic and operational objectives, Western Macedonia aims to build a sustainable bioeconomy that is transparent, inclusive, innovative, and environmentally responsible, ensuring long-term prosperity and participation of all community members (Table 1).

Table 1.

Strengthening the bioeconomy through strategic planning.

4. Discussion

The bioeconomy strategies of regions in transition are differentiated according to local priorities and available resources, forming three main categories. Firstly, certain regions, such as the Ruhr in Germany, are adopting strategies that are innovation and research-focused, with investments in research centers, partnerships with universities, and promotion of biotechnology and green innovation [14]. Conversely, regions such as Asturias in Spain are emphasizing the diversification of their production model, with a focus on sustainable practices in agriculture, forestry, and tourism, while leveraging local natural resources [17,18]. Thirdly, regions in Poland are pursuing gradual adaptation strategies through social participation and environmental policies, implementing measures to ensure social acceptance of the transition and providing support to local producers and enterprises active in the bioeconomy [20,80]. The Region of Western Macedonia has formulated a bioeconomy strategy within the context of decarbonization and the search for new sustainable economic activities.

In developing a strategy for the bioeconomy, it is important to focus on several priorities. First, educating both producers and consumers about the benefits of the bioeconomy is crucial [79,81]. This includes implementing strong communication strategies to raise awareness and understanding of how bio-based products and practices contribute to sustainability and economic development [82]. Improving green labelling schemes is another key priority [76,83]. The introduction of clear and reliable labels will help consumers to easily identify and choose organic products. This will not only promote environmentally friendly choices, but also encourage producers to adopt sustainable practices.

The strategy should include comprehensive and measurable objectives, with a particular focus on economic and environmental impacts [84,85]. These objectives should set clear, quantifiable targets to monitor progress and ensure accountability. By focusing on measurable results, the strategy can lead to significant improvements in both economic performance and environmental sustainability. The subsequent implementation of a governance model is also essential. This model should aim to streamline processes and minimize bureaucracy, making it easier for businesses and stakeholders to engage in bioeconomy activities [86]. Simplifying administrative procedures will encourage innovation and greater participation in the bioeconomy [87,88].

The strategy should focus mainly on waste management and innovative recovery options. This includes setting up systems for efficient waste collection, recycling, and conversion of waste into valuable products such as compost, bioenergy, and biomaterials. Prioritizing waste management will not only reduce environmental impacts but also create new economic opportunities. The bioeconomy in Western Macedonia is gradually developing, driven by the need for sustainable practices in agriculture, waste management, and various industrial sectors. The favorable climate and increasing environmental awareness of citizens are creating a supportive environment for the development of bio-based industries [89,90,91]. However, significant challenges remain, including economic constraints, technological gaps, and regulatory complexity.

Economic challenges, in particular limited financial resources, limit the ability of companies to invest in upgrading facilities and adopting new technologies [78,83]. While subsidies provide some relief, they are often insufficient to cover all necessary investments, limiting the scale and impact of bio-based initiatives. Technological barriers also limit growth as companies struggle to access advanced, locally adapted technologies [78,92,93]. This technological lag reduces operational efficiency and impacts the sector’s ability to expand and meet the growing demand for sustainable solutions [94]. Finally, legal and regulatory barriers further complicate the landscape, as companies often face lengthy and costly processes to obtain the necessary permits and certifications [85]. This creates uncertainty that makes it difficult for them to plan and invest in long-term growth, especially when competing with larger international players that may have easier access to global markets.

The bioproducts sector in Western Macedonia has a significant impact on communities, particularly in terms of job creation. Initiatives that promote sustainable practices help to raise public awareness of environmental protection [95,96,97]. In addition, bio-based cooperatives contribute to the local economy by providing stable employment opportunities, especially in rural areas where employment opportunities are limited [98]. However, challenges related to working conditions, especially during peak periods when workloads and associated health risks increase. Training programs and sustainability policies further enhance community involvement.

The economic potential of the bio-product sector in Western Macedonia is promising, especially with the growing global demand for sustainable products. Organic and sustainable food markets are benefiting from increased consumer awareness, creating new opportunities for growth [99,100]. Access to EU funding is helping to support the stability and growth of cooperatives, while training programs are improving productivity through sustainable agricultural practices. However, economic and technological barriers continue to limit the sector’s ability to scale up.

In terms of export potential, there are significant opportunities to expand markets, particularly for sustainable materials where demand is growing [101]. Certification and compliance with environmental standards increase competitiveness, but also pose additional regulatory and logistical challenges [102]. Expanding waste management and sustainability initiatives can attract investment and improve market reach, although technological and regulatory barriers still need to be addressed [103,104]. Overall, these drivers and barriers shape the development of the bioeconomy in Western Macedonia and influence its social, environmental, and economic contribution to the region.

5. Conclusions

The development and implementation of the bioeconomy strategy in Western Macedonia will be guided by several planned steps to ensure sustainable development and innovation. Initially, efforts to engage stakeholders will be expanded to include more stakeholders from different sectors, including industry, academia, and civil society. This will include the organization of additional workshops, focus groups, and public consultations to bring together different perspectives and promote collaborative partnerships. The detailed blueprint delineates specific tasks, assigns roles and responsibilities, and outlines resource needs, including technical support, funding allocation, and schedule management, to ensure a structured and transparent implementation process. The integration of these structured activities with practical operational objectives will cultivate a sustainable, inclusive bioeconomy that responds to the evolving needs of communities and businesses in Western Macedonia.

The development of policy and regulatory frameworks is equally crucial, as it will lead to their refinement and expansion to support the bioeconomy. This will include the establishment of new regulations that will provide incentives for sustainable practices, as well as the review of existing policies to ensure their alignment with strategic objectives. The development of a robust policy and regulatory framework for the bioeconomy in Western Macedonia will be achieved through a structured approach to ensure the implementation of actionable steps, clear responsibilities, deadlines and the necessary resources. The overarching objective of this framework is to establish a policy environment that offers incentives for sustainable bio-based practices and is aligned with the long-term goals of the bioeconomy.

Infrastructure development is another key area of focus, as it is pivotal to the growth of bio-based businesses in Western Macedonia. By allocating resources to logistics, waste management, and renewable energy, the strategy guarantees that bio-based businesses will possess the requisite resources for sustainable growth and long-term resilience. The strategy will prioritize the enhancement of logistics networks to facilitate efficient transport and distribution of materials for bio-based businesses, thereby minimizing both time and cost. The strategy will also strengthen waste management systems to support the principles of the circular economy, including the creation of dedicated facilities for recycling and waste-to-energy processes.

Finally, the strategy calls for the enhancement of a monitoring and evaluation system to oversee the advancement of the bioeconomy strategy in Western Macedonia, ensuring both accountability and adaptability. To this end, the introduction of advanced data collection tools, data analysis mechanisms, and feedback loops between evaluation findings and strategic planning adjustments is imperative. The implementation of these improvements will yield clear, actionable insights, thereby enabling the strategy to undergo timely updates as required. Key tasks will include the selection and implementation of advanced digital tools for data collection, which will enable real-time monitoring of key performance indicators (KPIs) across bioeconomy projects.

The limitations of this study are related to several factors that affect the implementation and effectiveness of the proposed bioeconomy strategy. A review of international experience indicates that effective transition strategies are characterized by long-term planning with clearly defined objectives, the securing of funding, adaptation to local needs, and active participation by society and business. In the context of Western Macedonia, despite the presence of challenges such as geographical isolation, inadequate technological infrastructure, and financial limitations, the implementation of a bespoke strategy that incorporates international best practices has the potential to facilitate a successful transition. It is imperative that these strategies are adaptable and evolve in accordance with the unique characteristics of the region. Primarily, the geographical isolation of the study area and the limited infrastructure are significant barriers to the development of the required supply chains and the establishment of links with markets. Additionally, the financial resources available to support initiatives are often limited, making it difficult to implement large investments and finance innovative technologies. Technological barriers, such as the paucity of adapted and advanced bio-based solutions, further limit the ability to scale up activities. Concurrently, the complexity and bureaucracy of regulatory and administrative processes can impede progress and act as a deterrent to investors. The dearth of skilled personnel within the regional workforce necessitates the implementation of extensive educational and training programs, which in turn require time and additional resources. Finally, social resistance and a lack of awareness of the benefits of the bioeconomy can affect the acceptance and active participation of local communities, limiting the overall effectiveness of initiatives.

Future research that may emerge from this manuscript focuses on various directions for improving and implementing bioeconomy strategies. Firstly, there is a necessity for detailed studies to be conducted in order to assess local biological resources and their potential for sustainable exploitation, with a focus on innovative practices and technologies. In addition, the effectiveness of different governance and cooperation models between local actors, businesses, and research institutions could be investigated to enhance inclusiveness and efficiency in policy implementation. Concurrently, the exploration of innovative financing mechanisms to augment investment in bio-based enterprises could be undertaken. The implementation of systems to monitor and evaluate the progress and impact of bioeconomy initiatives is a subject that merits further research, with a view to continuously improving strategies. Finally, the integration of social aspects, such as acceptance by local communities and changes in social structures, is important for the formulation of integrated sustainable development strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-I.P. and A.F.; methodology, C.-I.P.; validation, C.-I.P. and T.K.; investigation, C.-I.P.; resources, C.-I.P. and G.M.; data curation, C.-I.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-I.P.; writing—review and editing, C.-I.P. and A.F.; visualization, C.-I.P.; supervision, C.-I.P., A.F., G.M., T.K. and Y.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project “BIOMODEL4REGIONS—Supporting the establishment of the innovative governance models to achieve better-informed decision-making processes, social engagement and innovation in the bio-based economy” (Grant Agreement 101060476), that is funding by the HORIZON EUROPE.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to disclose the use of DeepL Write as a language support tool, which was utilized to enhance the clarity and quality of the manuscript. This acknowledgement is made in the interests of transparency and adherence to best practice in academic publishing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EU | European Union |

| ERDF | European Regional Development Fund |

| NGOs | non-governmental organizations |

| CluBE | Bioeconomy and Environment Cluster of Western Macedonia |

References

- de Besi, M.; McCormick, K. Towards a Bioeconomy in Europe: National, Regional and Industrial Strategies. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10461–10478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Börner, J.; Förster, J.; von Braun, J. Governance of the Bioeconomy: A Global Comparative Study of National Bioeconomy Strategies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R. Bioeconomy Strategies: Contexts, Visions, Guiding Implementation Principles and Resulting Debates. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanis, C.; Stavropoulos, A.; Stavropoulou, E.; Tsigalou, C.; Constantinidis, T.C.; Bezirtzoglou, E. A Spotlight on Environmental Sustainability in View of the European Green Deal. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowicz, M. Bioeconomy as a Concept for the Development of Agriculture and Agribusiness. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2020, 365, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Luo, J.; Pu, A.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wu, S.; Long, Y.; Leng, Y.; Dong, Z.; Wan, X. From Biotechnology to Bioeconomy: A Review of Development Dynamics and Pathways. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Bogdanski, A.; Boldt, C.; Börner, J.; von Braun, J.; Concubhair, C.O.; Ní Choncubhair, Ó.; Durham, B.; Ecuru, J.; Lang, C.; et al. Bioeconomy Globalization: Recent Trends and Drivers of National Programs and Policies; International Advisory Council on Global Bioeconomy: 2024. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5023374 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Staffas, L.; Gustavsson, M.; McCormick, K. Strategies and Policies for the Bioeconomy and Bio-Based Economy: An Analysis of Official National Approaches. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2751–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Gu, Y. Mineral Resources and the Green Economy: A Blueprint for Sustainable Development and Innovation. Resour. Policy 2024, 88, 104461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B. A New Blueprint for a Green Economy; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2013; ISBN 9780203097298. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou, C.-I.; Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Loizou, E.; Jurga, P. Operational Taxonomy of Farmers’ towards Circular Bioeconomy in Regional Level. Oper. Res. 2024, 24, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, C.-I.; Loizou, E.; Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Karelakis, C. Agricultural Resources and Practices in the Circular Bioeconomy Adoption: Evidence from a Rural Region of Greece. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2023, 15, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venghaus, S.; Stark, S.; Hilgert, P. Transformation Towards a Sustainable Regional Bioeconomy—A Monitoring Approach. In Transformation Towards Sustainability; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 201–229. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, A.; Schroeder, H. How to Avoid Unjust Energy Transitions: Insights from the Ruhr Region. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2022, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, K.; Dahlke, J. Born to Transform? German Bioeconomy Policy and Research Projects for Transformations towards Sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 195, 107366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbert, E.; Ladu, L.; Morone, P.; Quitzow, R. Comparing Policy Strategies for a Transition to a Bioeconomy in Europe: The Case of Italy and Germany. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 33, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Sánchez, J.P.; García-Elcoro, V.E.; Rosillo-Calle, F.; Xiberta-Bernat, J. Assessment of Forest Bioenergy Potential in a Coal-Producing Area in Asturias (Spain) and Recommendations for Setting up a Biomass Logistic Centre (BLC). Appl. Energy 2016, 171, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, B.M.; Paredes, J.P.; García, R. Integration of Biocoal in Distributed Energy Systems: A Potential Case Study in the Spanish Coal-Mining Regions. Energy 2023, 263, 125833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, E.; Tyczewska, A.; Twardowski, T. Bioeconomy Development Factors in the European Union and Poland. New Biotechnol. 2021, 60, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikielewicz, D.; Dąbrowski, P.; Bochniak, R.; Gołąbek, A. Current Status, Barriers and Development Perspectives for Circular Bioeconomy in Polish South Baltic Area. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengal, P.; Wubbolts, M.; Zika, E.; Ruiz, A.; Brigitta, D.; Pieniadz, A.; Black, S. Bio-Based Industries Joint Undertaking: The Catalyst for Sustainable Bio-Based Economic Growth in Europe. New Biotechnol. 2018, 40, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, C.; Shapira, P. Building the Bioeconomy: A Targeted Assessment Approach to Identifying Biobased Technologies, Challenges and Opportunities. Eng. Biol. 2024, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlangwani, E.; Mpye, K.L.; Matsuro, L.; Dlamini, B. The Use of Technological Innovation in Bio-Based Industries to Foster Growth in the Bioeconomy: A South African Perspective. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2023, 19, 2200300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, A.S.; Santos, J.M.R.C.A. Sustainability from Policy to Practice: Assessing the Impact of European Research and Innovation Frameworks on Circular Bioeconomy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracco, S.; Calicioglu, O.; Gomez San Juan, M.; Flammini, A. Assessing the Contribution of Bioeconomy to the Total Economy: A Review of National Frameworks. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, A.; Twardowski, T.; Wohlgemuth, R. Bioeconomy for Sustainable Development. Biotechnol. J. 2019, 14, 1800638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, C.-I.; Loizou, E.; Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Michailidis, A.; Karelakis, C.; Fallas, Y.; Paltaki, A. What Makes Farmers Aware in Adopting Circular Bioeconomy Practices? Evidence from a Greek Rural Region. Land 2023, 12, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The White House. National Bioeconomy Blueprint; The White House: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Paltaki, A.; Loizou, E.; Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Partalidou, M.; Nastis, S.; Papadopoulou, C.I.; Michailidis, A. Farmers’ Training Needs in Bioeconomy: Evidence from Greece. Int. J. Sustain. Agric. Manag. Inform. 2024, 10, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtsal, Y.; Rinaldi, G.M.; Grande, M.M.; Viaggi, D. Education and Training in Agriculture and the Bioeconomy: Learning from Each Other. In Agricultural Bioeconomy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 287–313. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, G.; Szopik-Depczyńska, K.; Beltramo, R.; D’Adamo, I.; Ioppolo, G. Smart and Sustainable Bioeconomy Platform: A New Approach towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argente-Garcia, J.E.; Bernardeau-Esteller, J.; Aguilera, C.; Gómez Pinchetti, J.L.; Semitiel-García, M.; Skarmeta Gómez, A.F. Multi-Stakeholder Networks as Governance Structures and ICT Tools to Boost Blue Biotechnology in Spain. Sustainability 2024, 17, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, L.; Iles, A. Scales of Progress, Power and Potential in the US Bioeconomy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, D.H.J.; Klaassen, P.; van Wassenaer, L.; Broerse, J.E.W. Constructing the Public in Roadmapping the Transition to a Bioeconomy: A Case Study from the Netherlands. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, P.M.; González García, S.; Imbert, E.; Lijó, L.; Moreira, M.T.; Tani, A.; Tartiu, V.E.; Morone, P. Transitioning towards the Bio-economy: Assessing the Social Dimension through a Stakeholder Lens. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1135–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorek, S.; Spangenberg, J.H. Sustainable Consumption within a Sustainable Economy—Beyond Green Growth and Green Economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linser, S.; Lier, M. The Contribution of Sustainable Development Goals and Forest-Related Indicators to National Bioeconomy Progress Monitoring. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, N.; Giuntoli, J.; Araujo, R.; Avraamides, M.; Balzi, E.; Barredo, J.I.; Baruth, B.; Becker, W.; Borzacchiello, M.T.; Bulgheroni, C.; et al. Development of a Bioeconomy Monitoring Framework for the European Union: An Integrative and Collaborative Approach. New Biotechnol. 2020, 59, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonoglou, D.; Rontos, K.; Salvati, L. Toward a Socio-Environmental Disadvantaged Region? The Case of Western Macedonia, Greece. In Environmental Sustainability and Global Change; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 157–191. [Google Scholar]

- Samara, E.; Kilintzis, P.; Katsoras, E.; Martinidis, G.; Kosti, P. A Dynamic Analysis to Examine Regional Development in the Context of a Digitally Enabled Regional Innovation System: The Case of Western and Central Macedonia (Greece). Systems 2024, 12, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinidis, G.; Dyjakon, A.; Minta, S.; Ramut, R. Intellectual Capital and Sustainable S3 in the Regions of Central Macedonia and Western Macedonia, Greece. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commision: Regional Innovation Scoreboard 2023—Regional Profiles Greece; European Commision: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Development Programming Directorate of the Western Macedonia Region. Regional Development Programme of Western Macedonia 2021–2025. Available online: https://www.pdm.gov.gr/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/fek-ppa-pdm-2021-2025-5582-1-12-2021.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Special Operational Program Management Service of the Region of Western Macedonia (EYDEP PDM) Western Macedonia Region Program 2021–2027 1st Program Draft. Available online: https://pepdym.gr/images/Wb/6PEP/050/11/2.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Timmermans, F.; Katainen, J. Reflection Paper Towards a Sustainable Europe by 2030; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, J. Sustainable Development: Meaning, History, Principles, Pillars, and Implications for Human Action: Literature Review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1653531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherp, A.; George, C.; Kirkpatrick, C. A Methodology for Assessing National Sustainable Development Strategies. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2004, 22, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munier, N. Strategic Approach in Multi-Criteria Decision Making; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 351, ISBN 978-3-031-44452-4. [Google Scholar]

- Saritas, O.; Pace, L.A.; Stalpers, S.I.P. Stakeholder Participation and Dialogue in Foresight. In Participation and Interaction in Foresight; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kouskoura, A.; Kalliontzi, E.; Skalkos, D.; Bakouros, I. Evaluating Experts’ Perceptions on Regional Competitiveness Based on the Ten Key Factors of Assessment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szarka, N.; García Laverde, L.; Thrän, D.; Kiyko, O.; Ilkiv, M.; Moravčíková, D.; Cudlínová, E.; Lapka, M.; Hatvani, N.; Koós, Á.; et al. Stakeholder Engagement in the Co-Design of Regional Bioeconomy Strategies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieken, S.; Dallendörfer, M.; Henseleit, M.; Siekmann, F.; Venghaus, S. The Multitudes of Bioeconomies: A Systematic Review of Stakeholders’ Bioeconomy Perceptions. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1703–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigkas, M.; Karagouni, G. State/Academia Key Stakeholders’ Perceptions Regarding Bioeconomy: Evidence from Greece. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Escobar, C.H.; Granobles Torres, J.C.; Villa Rodríguez, A.O. A Critical Analysis of the Dynamics of Stakeholders for Bioeconomy Innovation: The Case of Caldas, Colombia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, L.; Giurca, A.; Kleinschmit, D. Contesting the Framing of Bioeconomy Policy in Germany: The NGO Perspective. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2022, 24, 822–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Grundmann, P. What Does an Inclusive Bioeconomy Mean for Primary Producers? An Analysis of European Bioeconomy Strategies. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2023, 25, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiden, S.; Lucas, H. Innovation and Bioeconomy. In The Bioeconomy System; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 269–287. [Google Scholar]

- Patermann, C.; Aguilar, A. The Origins of the Bioeconomy in the European Union. New Biotechnol. 2018, 40, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. Enhancing Stakeholder Involvement in EU Bioeconomy Policy; Final Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Liu, Q.; Pu, A.; Wang, S.; Chen, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Z.; Wan, X. Knowledge Mapping of Bioeconomy: A Bibliometric Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, J.P.; Murphy, E.; Scott, M. Bioeconomy, Planning and Sustainable Development: A Theoretical Framework. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Celebi, D.; Pansera, M. A Framework for a Responsible Circular Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 400, 136679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.E.; Kopke, K.; O’Mahony, C. Towards a Circular Economy: Using Stakeholder Subjectivity to Identify Priorities, Consensus, and Conflict in the Irish EPS/XPS Market. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urmetzer, S.; Lask, J.; Vargas-Carpintero, R.; Pyka, A. Learning to Change: Transformative Knowledge for Building a Sustainable Bioeconomy. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 167, 106435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, D.; Veijonaho, S.; Toppinen, A. Towards Sustainability? Forest-Based Circular Bioeconomy Business Models in Finnish SMEs. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 110, 101848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurster, S.; Ladu, L. Bio-Based Products in the Automotive Industry: The Need for Ecolabels, Standards, and Regulations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fytili, D.; Zabaniotou, A. Organizational, Societal, Knowledge and Skills Capacity for a Low Carbon Energy Transition in a Circular Waste Bioeconomy (CWBE): Observational Evidence of the Thessaly Region in Greece. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 813, 151870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harichandan, S.; Kar, S.K. Financing the Hydrogen Industry: Exploring Demand and Supply Chain Dynamics. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebolledo-Leiva, R.; Moreira, M.T.; González-García, S. Progress of Social Assessment in the Framework of Bioeconomy under a Life Cycle Perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 175, 113162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavy, S.; Allegretti, G.; Presotto, E.; Montoya, M.A.; Talamini, E. Measuring the Bioeconomy Economically: Exploring the Connections between Concepts, Methods, Data, Indicators and Their Limitations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyka, A.; Cardellini, G.; van Meijl, H.; Verkerk, P.J. Modelling the Bioeconomy: Emerging Approaches to Address Policy Needs. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Cai, X.; Hu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Lee, Y.; Khanna, M.; Cortés-Peña, Y.R.; Guest, J.S.; Kent, J.; Hudiburg, T.W.; et al. An Agent-Based Modeling Tool Supporting Bioenergy and Bio-Product Community Communication Regarding Cellulosic Bioeconomy Development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regona, M.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Hon, C.; Teo, M. Artificial Intelligence and Sustainable Development Goals: Systematic Literature Review of the Construction Industry. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 108, 105499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Boas, I.; Oosterveer, P. Transparency in Global Sustainability Governance: To What Effect? J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2020, 22, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasolino, N.G.; Zavalloni, M.; Viaggi, D. The Role of Collaboration and Entrepreneurship in Strengthening the Participation of Primary Producers in the Bioeconomy. In Agricultural Bioeconomy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Fava, F.; Gardossi, L.; Brigidi, P.; Morone, P.; Carosi, D.A.R.; Lenzi, A. The Bioeconomy in Italy and the New National Strategy for a More Competitive and Sustainable Country. New Biotechnol. 2021, 61, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyarov, A.; Osmakova, A.; Popov, V. Bioeconomy in Russia: Today and Tomorrow. New Biotechnol. 2021, 60, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvador, R.; Barros, M.V.; Donner, M.; Brito, P.; Halog, A.; De Francisco, A.C. How to Advance Regional Circular Bioeconomy Systems? Identifying Barriers, Challenges, Drivers, and Opportunities. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 32, 248–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Hernández, A.; Esteban, E.; Garrido, P. Transition to a Bioeconomy: Perspectives from Social Sciences. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 224, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinek, P.; Smol, M. Bioeconomy as One of the Key Areas of Implementing a Circular Economy (CE) in Poland. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2020, 76, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, C.-I.; Loizou, E.; Chatzitheodoridis, F. Priorities in Bioeconomy Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review. Energies 2022, 15, 7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Sierra, A.; Zika, E.; Lange, L.; Ruiz de Azúa, P.L.; Canalis, A.; Mallorquín Esteban, P.; Paiano, P.; Mengal, P. The Bio-Based Industries Joint Undertaking: A High Impact Initiative That Is Transforming the Bio-Based Industries in Europe. New Biotechnol. 2021, 60, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Christensen, T.; Panoutsou, C. Policy Review for Biomass Value Chains in the European Bioeconomy. Glob. Transit. 2021, 3, 13–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, P.J.; Damerell, A. Bioeconomy and Circular Economy Approaches Need to Enhance the Focus on Biodiversity to Achieve Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfahrt, J.; Ferchaud, F.; Gabrielle, B.; Godard, C.; Kurek, B.; Loyce, C.; Therond, O. Characteristics of Bioeconomy Systems and Sustainability Issues at the Territorial Scale. A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, A.; Godina, R.; Azevedo, S.G.; Matias, J.C.O. Current Status, Emerging Challenges, and Future Prospects of Industrial Symbiosis in Portugal. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, R.; Puglieri, F.N.; Halog, A.; Andrade, F.G.D.; Piekarski, C.M.; De Francisco, A.C. Key Aspects for Designing Business Models for a Circular Bioeconomy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 124341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim-Lim, S.A.; Jamaludin, A.A.; Islam, A.S.M.T.; Weerabahu, S.; Priyono, A. Unlocking Potential for a Circular Bioeconomy Transition through Digital Innovation, Lean Manufacturing and Green Practices: A Review. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, R.-G.; Thomsen, M. Review of Ecosystem Services in a Bio-Based Circular Economy and Governance Mechanisms. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 50, 101298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruf, J.; Emberger-Klein, A.; Menrad, K. Consumer Response to Bio-Based Products—A Systematic Review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 34, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairon Azhar, N.N.; Ang, D.T.-C.; Abdullah, R.; Harikrishna, J.A.; Cheng, A. Bio-Based Materials Riding the Wave of Sustainability: Common Misconceptions, Opportunities, Challenges and the Way Forward. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottinger, A.; Ladu, L.; Quitzow, R. Studying the Transition towards a Circular Bioeconomy—A Systematic Literature Review on Transition Studies and Existing Barriers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reim, W.; Parida, V.; Sjödin, D.R. Circular Business Models for the Bio-Economy: A Review and New Directions for Future Research. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Dong, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Hua, J.; Liu, Y.; Osman, A.I.; Farghali, M.; Huang, L.; et al. Biomaterials Technology and Policies in the Building Sector: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 715–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrah, J.K.; Vidal, D.G.; Dinis, M.A.P. Raising Awareness on Solid Waste Management through Formal Education for Sustainability: A Developing Countries Evidence Review. Recycling 2021, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berchin, I.I.; de Aguiar Dutra, A.R.; de Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O. How Do Higher Education Institutions Promote Sustainable Development? A Literature Review. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Agrawal, S.; Samadhiya, A.; Kumar, A.; Luthra, S.; Jain, V. Adoption of Green Finance and Green Innovation for Achieving Circularity: An Exploratory Review and Future Directions. Geosci. Front. 2024, 15, 101669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marting Vidaurre, N.A.; Vargas-Carpintero, R.; Wagner, M.; Lask, J.; Lewandowski, I. Social Aspects in the Assessment of Biobased Value Chains. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Anh, T.; Nguyen-To, T. Consumer Purchasing Behaviour of Organic Food in an Emerging Market. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.D.; Bragança, L.; da Silva, M.V.; Oliveira, R.S. Challenges and Solutions for Sustainable Food Systems: The Potential of Home Hydroponics. Sustainability 2024, 16, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshood, T.; Nawanir, G.; Mahmud, F.; Mohamad, F.; Ahmad, M.; Abdul Ghani, A. Expanding Policy for Biodegradable Plastic Products and Market Dynamics of Bio-Based Plastics: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshmandi, M.; Sahebi, H.; Ashayeri, J. The Incorporated Environmental Policies and Regulations into Bioenergy Supply Chain Management: A Literature Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rena; Yadav, S.; Patel, S.; Killedar, D.J.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, R. Eco-Innovations and Sustainability in Solid Waste Management: An Indian Upfront in Technological, Organizational, Start-Ups and Financial Framework. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 113953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, T.M.W.; Xiong, X.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Yu, I.K.M.; Poon, C.S. Sustainable Food Waste Management towards Circular Bioeconomy: Policy Review, Limitations and Opportunities. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 297, 122497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).