Land Reforms Revisited: An Emerging Perspective on the Hellenic Land Administration Reform as a Wicked Policy Problem

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Wicked Problems: Origin, Definition, and Characteristics

- (1)

- There is no definite formulation of a wicked problem;

- (2)

- Wicked problems have no stopping rule;

- (3)

- Solutions to wicked problems are not true or false but good or bad;

- (4)

- There is no immediate or ultimate test of a solution to a wicked problem;

- (5)

- Every solution is essentially a “one-shot operation”; because there is no opportunity to learn by trial and error, every attempt counts significantly;

- (6)

- Wicked problems have no clear solution and perhaps not even a set of possible solutions;

- (7)

- Every wicked problem is essentially unique;

- (8)

- Every wicked problem can be considered to be a symptom of another problem;

- (9)

- There are multiple explanations for a wicked problem;

- (10)

- The planner (policymaker) has no right to be wrong.

2.2. The Wickedness of Land Reforms

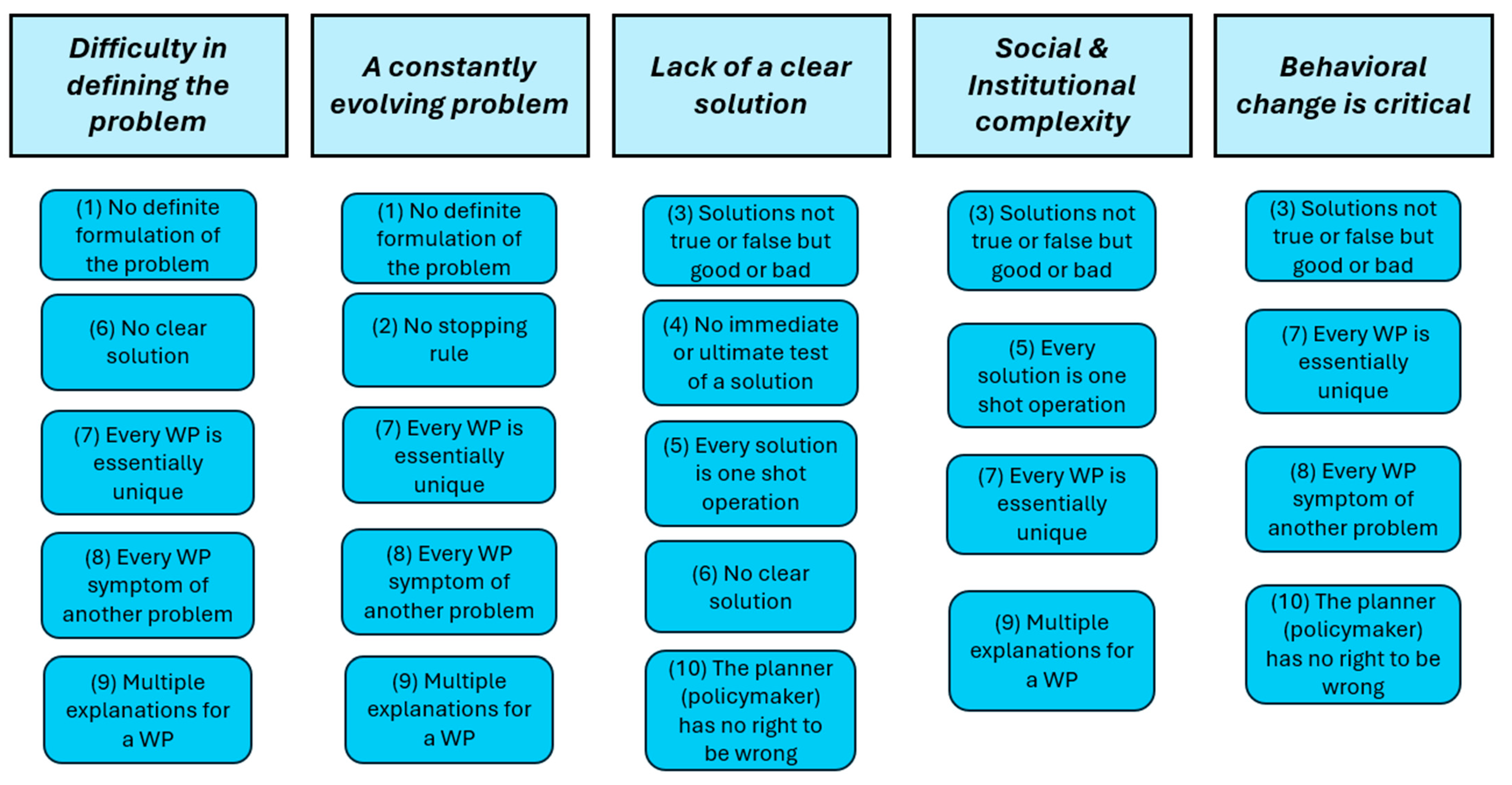

2.2.1. Difficulty in Defining the Problem

2.2.2. The Problem Is Constantly Evolving

2.2.3. Lack of a Clear Solution

2.2.4. Social and Institutional Complexity

2.2.5. Behavioral Change Is Critical

3. Discussion

3.1. Complexity

3.2. Conflict

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Appendix A. Conceptual Mapping of Land Reforms’ Traits and Wicked Problem Characteristics

Appendix B. Tables

| Year | Milestone | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 | Law 2308/1995 | Foundational law providing the legal framework for the cadastral adjudication process. |

| 1998 | Law 2664/1998 | Foundation law providing the legal framework for the operation of the Hellenic Cadastre System (HCS). |

| 2001 | Constitutional Amendment | Reinforced the mandate for establishing a comprehensive land and forestry registry system. |

| 2010 | 1st EAP | Provided the acceleration of the reform and set the milestone for completion in 2020. |

| 2010 | Law 3889/2010 | Provisions for the ratification of forest maps. |

| 2012 | 2nd EAP | Provided, among others, the acceleration of the reform; strict deadlines for the validation of forest maps and delineation of coastal zones; tendered the cadastral projects in the rest of the country; streamlined property transfer procedures for tax purposes; and set the milestone for completion in 2020. |

| 2013 | Law 4164/2013 | Abolition of HEMCO; simplification of procurement procedures. |

| 2014 | Law 4280/2014 | Forestry Regulation Legislation (Chapter C). |

| 2015 | 3rd EAP | Provided, among others, the adoption of a new legislative framework about forests and the preparation of forest maps; to set up a new organizational structure to operate the HCS; to proceed the cadastral registration in the rest of the country. |

| 2016 | Law 4389/2016 | Accelerated forest map preparation, verification, and validation (Chapter Θ). |

| 2018 | Law 4512/2018 | Established the framework for merging land administration organizations (of the HCS, RMS, and DC) (Chapter A). |

| August 2018 | End of Economic Adjustment Programs—Onset of Enhanced Surveillance (till 2022)—HLAR progress continued to be monitored by EU authorities. | |

| 2020 | Law 4685/2020 | Provisions for forest maps and unauthorized land-use changes in forests. |

| 2021 | Law 4821/2021 | Acceleration of completion of the HCS; correction of first registrations; and licensed surveyors to update the cadastral maps. |

| PD 3/2021 | Transfer of responsibilities of the HELLENIC CADASTRE to the Ministry of Digital Governance | |

| 2022 | Law 4915/2022 | Regulates state ownership rights in land plots which have been afforested (Article 93). |

| Law 4936/2022 | Regulates state ownership rights in land plots that have been afforested in the cadastral registration process (Article 40). | |

| Law 4934/2022 | Provision for the inclusion of the areas pertinent to DC in the HCS and harmonization of legal frameworks. | |

| 2023 | Law 5076/2023 | Acceleration of completion of the HCS; handling pending registering deeds to the HCS; strengthening operational capacity of the HELLENIC CADASTRE; and simplification and acceleration of property transfer. |

| 2024 | Law 5142/2024 | Acceleration of cadastral registration to complete the HCS; simplification of procedures; introduced AI in land administration; provisions for the operation of the HELLENIC CADASTRE. |

| Sources for Table A1 |

|

| Year | Activity | Progress Achieved |

|---|---|---|

| 1995–1999 | Initiation of the first-generation cadastral pilot programs | Early groundwork for mapping and registration. |

| 2008 | Launch of second-generation cadastral projects | Accelerated cadastral registration in urban areas. |

| 2009 | Onset of crisis | Cadastral registration completed of 17% of total property rights—6% of the country’s area. |

| 2011 | Procurement of third-generation cadastral projects | Targeted ~18% of the country’s property rights (~26% of the area) in peri-urban and rural areas. |

| 2016 | Procurement of fourth-generation cadastral projects | Targeted ~42% of the country’s property rights (~63.4% of the area) covering an additional 4000 municipalities, including in rural and mountainous areas. |

| 2019 | EC co-funding of fouth-generation cadastral projects | Boosted progress with EC approval co-financing, with funds from the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF); cadastral registration completed ~33% of property rights (8,8% of the country’s area). |

| 2021 | Digitizing the mortgage offices’ registry books | Initiation of the project (procurement) to digitize registry books to enhance access to old land registry records and facilitate property transfer procedures. |

| 2023 | Accelerated efforts toward completing 100% cadastral coverage; organizational restructuring | Cadastral registration completed ~42% of property rights (15% of the country’s area); creation of 14 cadastral offices and 69 branches; forest maps validated for 88,5% of the total area. |

| 2024 | cadastral registration rate ~52% of total property rights at the end of 2024. | |

| 2025 | Projected completion date of the adjudication process | Abolishment of ~390 mortgage offices and creation of 17 cadastral offices and 75 branches in January 2025; Aiming to achieve national cadastral registration by the end of 2025. |

| Sources for Table A2 |

|

References

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackoff, R. Redesigning the Future: A Systems Approach to Societal Problems; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 1–260. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, W.N. Methods of the Second Type: Coping with the Wilderness of Conventional Policy Analysis. Policy Stud. Rev. 1988, 7, 720–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. The Structure of Ill Structured Problems. Artif. Intell. 1973, 4, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisschemoller, M.; Hoppe, R. Coping with Intractable Controversies: The Case for Problem Structuring in Policy Design and Analysis. Knowl. Policy 1995, 8, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D.; Fricska, S.; Wehrmann, B.; Augustinus, C.; Munro-Faure, P.; Törhönen, M.-P.; Arial, A. Towards Improved Land Governance. Rome. Food 2009, 781, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, T. Land Administration Reform: Indicators of Success and Future Challenges; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou, D. The Unpromised Land: Agrarian Reform and Conflict Worldwide; Zed Books: London, UK, 1990; p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- Davy, B. After form. The credibility thesis meets property theory. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, S.; Babalola, K.; Whittal, J. Theories of land reform and their impact on land reform success in Southern Africa. Land 2019, 8, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, I.; Enemark, S.; Wallace, J.; Rajabifard, A. Land Administration for Sustainable Development, 1st ed.; Esri Academic Press: Redlands, CA, USA, 2010; p. 487. [Google Scholar]

- Zevenbergen, J. Land Administration:To See the Change from Day to Day; International Training Institute (ITC): Enschede, The Nederland, 2009; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Zevenbergen, J.; De Vries, W.T.; Bennett, R.M. Future directions in responsible land administration. In Advances in Responsible Land Administration; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deligiannis, I. Thoughts for the type and the evidentiary power of the Cadastre that is designed to be implemented in Greece. Nomiko Vima 1993, 41, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Doris, F. Key legislative policy choices in the draft law on the National Cadastre. In The Land Register; Ant. Sakkoulas: Athens, Greece, 2001; pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- FIG. The Statement on the Cadastre. FIG Publication No.11; The International Federation of Surveyors (FIG): Canberra, Australia, 1995; p. 15. ISBN 0 644 4533 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Parliament. Introductory Report of Law 2664/1998; Hellenic Parliament: Athens, Greece, 1998; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, J.; Steudler, D. Cadastre 2014: A Vision for a Future Cadastral System; FIG Commission 7: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1998; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Salamastrakis, D. Comparison of the Draft Law for the Hellenic Cadastre with the Cadastral Regulation of the Dodecanese Cadastre. In The Land Register, 1st ed.; Ant.Sakkoulas: Athens, Greece, 2001; pp. 123–184. [Google Scholar]

- Sarris, E. Hellenic Cadastre: Concerns about the new institution. In Proceedings of the Hellenic Cadastre, Cadastral Offices, Practical Problems of Implementation, Thessaloniki Bar Association, Thessaloniki, Greece, 1 November 2005; pp. 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- UNECE. Land Administration Guidelines with Special Reference to Countries in Transition; United Nations: New York, NY, USA; Geneva, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Balla, E.; Zevenbergen, J.; Madureira, A.M.; Georgiadou, Y. Too Much, Too Soon? The Changes in Greece’s Land Administration Organizations during the Economic Crisis Period 2009 to 2018. Land 2022, 11, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Papadimas, L. Insight-Typically Greek, Delayed Land Register is Never-Ending Epic|Reuters. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-eurozone-greece-cadastre-insight-idUKKCN0SC0LA20151018/ (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Lavagnon, A.; Hodgson, D. Learning from international development projects: Blending Critical Project Studies and Critical Development Studies. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 1182–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, E. The Hellenic Cadastre. In Reforms in Public Administration during the Crisis (Executive summary in English); Spanou, C., Ed.; Papazissis Publishers: Athens, Greece, 2019; pp. 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Termeer, C.; Dewulf, A.; Biesbroek, R. A critical assessment of the wicked problem concept: Relevance and usefulness for policy science and practice. Policy Soc. 2019, 38, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; t Hart, P. From crisis to reform? Exploring three post-COVID pathways. Policy Soc. 2022, 41, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, J. The Critical Juncture Concept’s Evolving Capacity to Explain Policy Change. Eur. Policy Anal. 2019, 5, 170–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, J.; Howlett, M.; Murphy, M. Re-thinking the coronavirus pandemic as a policy punctuation: COVID-19 as a path-clearing policy accelerator. Policy Soc. 2022, 41, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanou, C. Crisis, Reform and the Way Forward in Greece: A Turbulent Decade; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Walby, S. Crisis and society: Developing the theory of crisis in the context of COVID-19. Glob. Discourse 2022, 12, 498–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, U.; Vermaas, P.E. The Wickedness of Rittel and Webber’s Dilemmas. Adm. Soc. 2020, 52, 960–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, E.; Zevenbergen, J.; Madureira, M. The development of a cadastral system from a policy reform perspective: The case of the Hellenic Cadastre. In Proceedings of the FIG e-Working Week 2021: Smart Surveyors for Land and Water Management. Challenges in a New Reality, Apeldoorn, Virtually, the Netherlands, 21–25 June 2021; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Balla, E.; Zevenbergen, J.; Madureira, A.M. Who’s and what? A case of competitive frames in Greece’s Land Administration Reform. Manuscr. Submitt. Publ. 2024, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Skaburskis, A. The origin of “wicked problems”. Plan. Theory Pract. 2008, 9, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchman, C.W. Guest Editorial : Wicked Problems. Manag. Sci. 1967, 14, B141–B142. [Google Scholar]

- Naime, M. Defining wicked problems for public policy: The case of Mexico’s disappearances. Gestión Y Análisis De Políticas Públicas 2020, 12, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camillus, J.C. Strategy as a wicked problem. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Head, B.; Alford, J. Wicked problems: The implications for public management. Int. Res. Soc. Public Manag. 12 Annu. Conf. 2008, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, R.; Burge, J. Untangling wicked problems. Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. AIEDAM 2016, 30, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N. Wicked Problems and Network Approaches to Resolution. Int. Public Manag. Rev. 2000, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Burge, J.E.; McCall, R. Diagnosing Wicked Problems. In Design Computing and Cognition; Gero, J.S., Hanna, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 313–326. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, F.D. Irregular Conflict and the Wicked Problem Dilemma: Strategies of Imperfection. Prism 2011, 2, 75–100. [Google Scholar]

- Alford, J.; Head, B.W. Wicked and less wicked problems: A typology and a contingency framework. Policy Soc. 2017, 36, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.; Head, B.W. Wicked tendencies in policy problems: Rethinking the distinction between social and technical problems. Policy Soc. 2017, 36, 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grint, K. Wicked Problems and Clumsy Solutions: The Role of Leadership. In The New Public Leadership Challenge; Brookes, S., Grint, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.; Meszoely, G.M.; Waddell, S.; Dentoni, D. The complexity of wicked problems in large scale change. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2015, 28, 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.N. Working with wicked problems in socio-ecological systems: Awareness, acceptance, and adaptation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, B.; Alford, J. Wicked Problems: Implications for Public Policy and Management. Adm. Soc. 2015, 47, 711–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termeer, C.; Dewulf, A.; Breeman, G.; Stiller, S. Governance Capabilities for Dealing Wisely with Wicked Problems. Adm. Soc. 2015, 47, 680–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termeer, C.; Dewulf, A. A small wins framework to overcome the evaluation paradox of governing wicked problems. Policy Soc. 2019, 38, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannink, D.; Trommel, W. Intelligent modes of imperfect governance. Policy Soc. 2019, 38, 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, N.; Hoppe, R. Problematizing ‘wickedness’: A critique of the wicked problems concept, from philosophy to practice. Policy Soc. 2019, 38, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, B. Forty years of wicked problems literature : Forging closer links to policy studies. Policy Soc. 2019, 38, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lônngren, J.; Poeck, K.V. Wicked problems : A mapping review of the literature. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2021, 28, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pava, C. New Strategies of Systems Change : Reclaiming Nonsynoptic Methods. Hum. Relat. 1986, 39, 615–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoulias, D.B.; Tsoukas, H. Managing Reforms on a Large Scale: What Role for OR/MS? J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1994, 45, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, B. The Law and Its Limits: Land Grievances, Wicked Problems, and Transitional Justice in Timor-Leste. Int. J. Transitional Justice 2021, 15, 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.; Fourie, C. Wicked Problems, Soft Systems and Cadastral Systems in Periods of Uncertainty. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Spatial Information for Sustainable Development, Nairobi, Kenya, 2–5 October 2001; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, M. Evaluating Cadastral Systems in Periods of Uncertainty: A Study of Cape Town’s Xhosa-Speaking Communities. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Natal, Durban, South Africa, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Păunescu, V.; Kohli, D.; Iliescu, A.-I.; Nap, M.-E.; Suba, E.-E.; Sălăgean, T. An Evaluation of the National Program of Systematic Land Registration in Romania Using the Fit for Purpose Spatial Framework Principles. Land 2022, 11, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, E. Property rights and governance of Africa’s rangelands: A policy overview. Nat. Resour. Forum 2009, 33, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, D.; Roberge, D. From Québec to Athens: Two National-Level Cadastral Projects One Challenge: Realignment For Success. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Spatial Information for Sustainable Development, Nairobi, Kenya, 2–5 October 2001; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, F.; Genovese, E. From parcels to global cadastre: Challenges and issues of the post-cadastral reform in Quebec. Surv. Rev. 2011, 44, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trist, E. Referent Organizations and the Development of Inter-Organizational Domains. Hum. Relat. 1983, 36, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunescu, C.; Paunescu, V. Realization of the Systematic Cadastre in Romania. J. Remote Sens. GIS 2021, 10, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, A. Moving from a Deed system to a Land Book Examples of Greece and Romania. In Proceedings of the UN/ECE WPLA Workshop on Spatial Information Management for Sustainable Real Estate Market Best Practice Guidelines on Nation-wide Land Administration, Athens, Greece, 28–31 May 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, M.; Sibanda, S.; Turner, S. Land Tenure Reform and Rural Livelihoods in Southern Africa. Nat. Resour. Perspect. 1999, February, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, B.; Zullo, F.; Fiorini, L.; Marucci, A. Illegal building in Italy: Too complex a problem for national land policy? Cities 2021, 112, 103159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantouvalou, M.; Mavridou, M.; Vaiou, D. Processes of social integration and Urban development in Greece: Southern challenges to European unification. Eur. Plan. Stud. 1995, 3, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, E.; Mantouvalou, M.; Vatavali, F. Housing production, ownership and globalization: Social aspects of changes in Greece and Albania. FORUM A+P 3 Period. Shk. Per Archit. Dhe Planif. Urban 2009, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Potsiou, C. Informal Urban development in Europe: Experiences from Albania and Greece; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2010; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chiodelli, F.; Moroni, S. The complex nexus between informality and the law: Reconsidering unauthorised settlements in light of the concept of nomotropism. Geoforum 2014, 51, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulgaris, Y. Greece: A Country Paradoxically Modern, 1st ed.; Polis: Athens, Greece, 2019; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, G. Land Registration and Cadastral Systems: Tools for Land Information and Management, 2nd ed.; Addison Wesley Longman Limited: Essex, UK, 1996; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, S.R. Land Law and Registration; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Dale, P.; McLaughlin, J. Land Administration; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 1–169. [Google Scholar]

- Gazis, A. The Cadastre and the Cadastre Books. Nomiko Vima 1992, 40, 1170–1178. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Varvaressos, A. Le Livres Fonciers et le Moyen de Leur Introduction en Grece; Ministere de l’Agriculture. Service des Etudes Agricoles et Economiques: Athenes, Greece, 1940; p. 171. [Google Scholar]

- Ladi, S.; Dalakou, V. Public Policy Analysis, 2nd ed.; Papazisis Publications: Athens, Greece, 2016; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Spanou, C.; Balla, E.; Ioannou, C.; Lampropoulou, M.; Oikonomou, D. Reforms in Public Administration Under the Crisis (Executive Summary in English); Papazissis Publishers: Athens, Greece, 2019; pp. 1–91. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.; Rein, M. Frame Reflection: Toward the Resolution of Intractable Policy Controversies; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, H.; Demir, T. Policy Communities. In Handbook of Public Policy Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pross, P. Canadian Pressure Groups: Talking Chameleons. In Pressure Groups; Richardson, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993; pp. 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon, J. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–235. [Google Scholar]

- Technical Chamber of Greece. Update of the Business Plan for the Completion of the National Cadastre; Technical Chamber of Greece: Athens, Greece, 2009; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans, L.M.; Thissen, W.A.H. Actor analysis methods and their use for public policy analysts. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2008, 196, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakyriakopoulos, G.; Panagiotou, A.A. Understanding the “people issues” of organizationally modernising a land registration system. In Proceedings of the Land Governance in an Interconnected World, Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, Washington, DC, USA, 20–24 March 2017; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Stakeholder Analysis Updated in February 2019 to Reflect the Establishment of the Hellenic Cadastre. World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- PAEPMO. Intervention of the Panhellenic Association of Employees in Private Mortgage Offices in Public Consultation of Ministry’s of Finance Draft Law 2014 “Deeds Registration Fees from Mortgage Offices”. Available online: http://www.opengov.gr/minfin/?c=23993 (accessed on 25 January 2025). (In Greek).

- Hellenic Parliament. Minutes of the Standing Committee on Production and Trade. In Hellenic Parliament; Hellenic Parliament: Athens, Greece, 2018; pp. 1–82. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J.M. Promoting Policy Reforms: The Twilight of Conditionality? World Dev. 1996, 24, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanou, C. External influence on structural reform: Did policy conditionality strengthen reform capacity in Greece? Public Policy Adm. 2018, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.; Pritchett, L.; Woolcock, M. Building State Capability. Evidence, Analysis, Action; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; p. 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J. The Washington Consensus as Policy Prescription for Development. In Proceedings of the Practitioners of Development, Washington, DC, USA, 13 January 2004; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- TFGR. Framework Development of the Greek Cadastre; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014; p. 45.

- TFGR. Second Quarterly Report; European Commission: Athens, Greece, 2012; p. 36.

- TFGR. Seventh Activity Report; European Commission: Athens, Greece, 2014; p. 23.

- TFGR. Sixth Activity Report; European Commission: Athens, Greece, 2015; p. 56.

- TFGR. First Quarterly Report; European Commission: Athens, Greece, 2011; p. 28.

- World Bank. Institutional Arrangements and Road Map–Component B; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone, K. External conditionality and the debt crisis: The ‘Troika’ and public administration reform in Greece. J. Eur. Public Policy 2015, 22, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Compliance Report; The Third Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece. First Review; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; pp. 1–33.

- European Commission. Compliance Report: The Third Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece. Second Review; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; pp. 1–71.

- European Commission. Compliance Report: ESM Stability Support Programme for Greece. Third Review; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; pp. 1–73.

- European Commission. Compliance Report: ESM Stability Support Programme for Greece. Fourth Review; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- Pierson, P. Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2000, 94, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S. Re-examining the International Diffusion of Planning. In Urban Planning in a Changing World, 1st ed.; Freestone, R., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; pp. 40–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dolowitz, D.; Marsh, D. Learning from Abroad: The Role of Policy Transfer in Contemporary Policy-Making. Gov. Int. J. Policy Adm. 2000, 13, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, D.; Sharman, J.C. Policy diffusion and policy transfer. Policy Stud. 2009, 30, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoukas, H. Enactive Reforms: Towards an Enactive Theory. In From Stagnation to Forced Adjustment; Kalyvas, S., Pagoulatos, G., Tsoukas, H., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, B.; Xiang, W.-N. Why is an APT approach to wicked problems important? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 154, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, B.W. Wicked Problems in Public Policy: Understanding and Responding to Complex Challenges; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, M.; Pritchett, L.; Woolcock, M. Escaping Capability Traps Through Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA). World Dev. 2013, 51, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B. Working with the Grain: Integrating Governance and Growth in Development Strategies; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balla, E.; Madureira, A.M.; Zevenbergen, J. Land Reforms Revisited: An Emerging Perspective on the Hellenic Land Administration Reform as a Wicked Policy Problem. Land 2025, 14, 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14020282

Balla E, Madureira AM, Zevenbergen J. Land Reforms Revisited: An Emerging Perspective on the Hellenic Land Administration Reform as a Wicked Policy Problem. Land. 2025; 14(2):282. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14020282

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalla, Evangelia, Ana Mafalda Madureira, and Jaap Zevenbergen. 2025. "Land Reforms Revisited: An Emerging Perspective on the Hellenic Land Administration Reform as a Wicked Policy Problem" Land 14, no. 2: 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14020282

APA StyleBalla, E., Madureira, A. M., & Zevenbergen, J. (2025). Land Reforms Revisited: An Emerging Perspective on the Hellenic Land Administration Reform as a Wicked Policy Problem. Land, 14(2), 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14020282