Land Governance in French-Speaking Africa: Comparative Analysis of Legal and Institutional Reforms for Sustainable Management of Community Lands

Abstract

1. Introduction

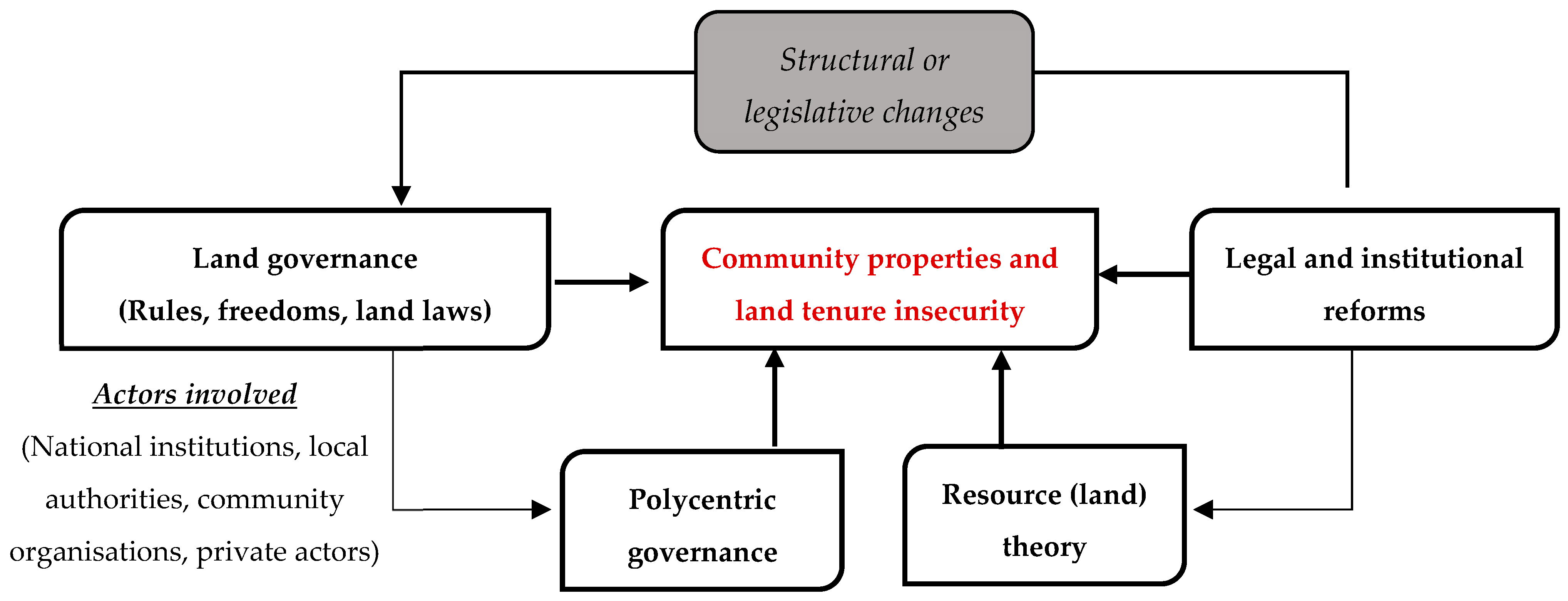

2. Conceptual and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.1.1. Concept of Land Governance

2.1.2. Legal and Institutional Reforms

2.1.3. Specificities of Community Lands in Africa

2.1.4. Land Tenure Insecurity

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.2.1. Resource Theory

2.2.2. Theoretical Model Around Common Goods: Case of Land Resources

3. Materials and Methods

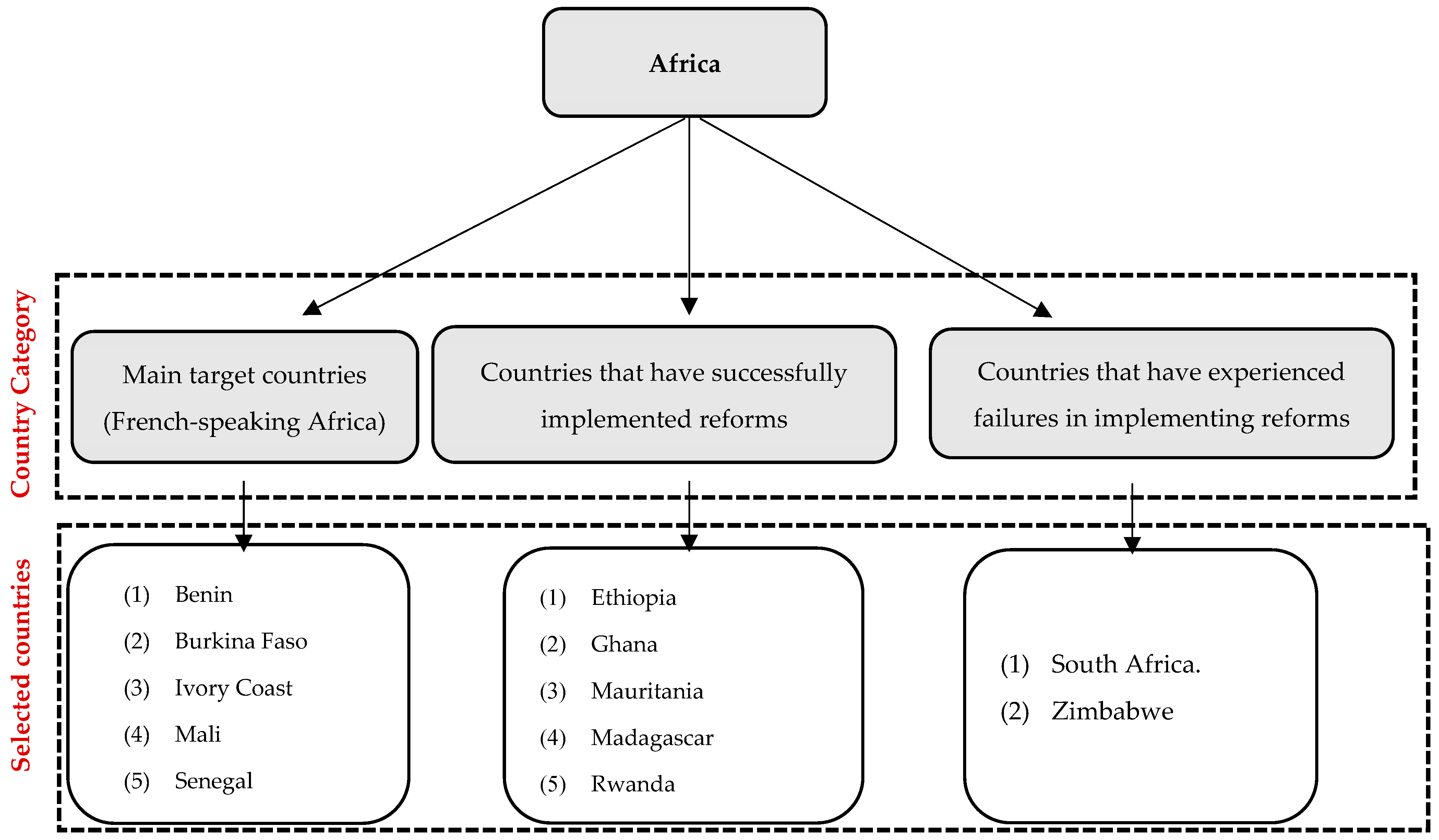

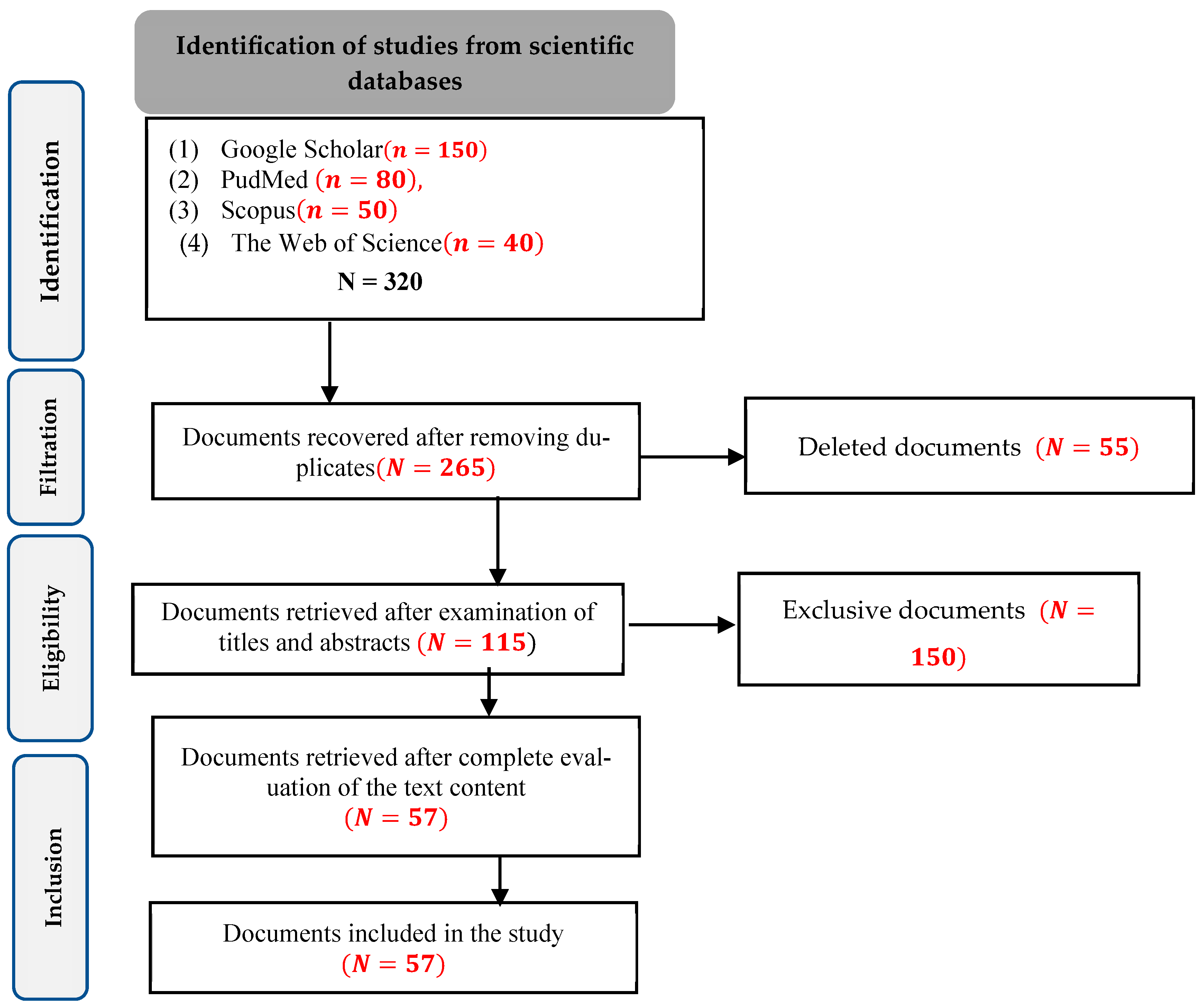

3.1. Data Collection Materials and Methods

3.2. Eligibility Criteria for Documents or References Used

3.3. Search Strategy

3.4. Analysis Method

4. Results

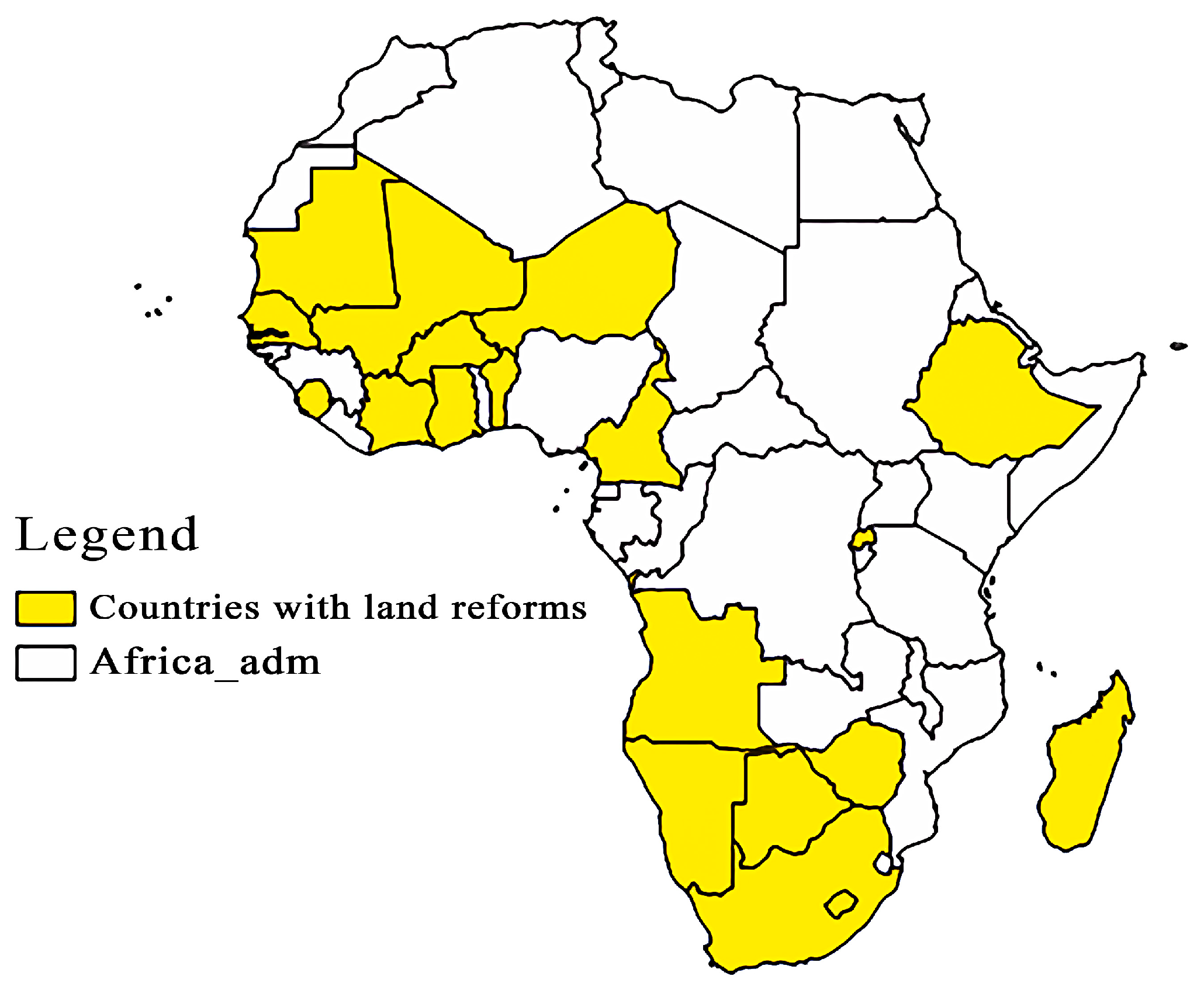

4.1. Spatial Analysis of Countries That Have Undergone Legal and Institutional Reforms in Africa

4.2. State of Play of Land Governance in French-Speaking Africa

4.3. Analysis of Legal and Institutional Reforms

4.3.1. Major Agrarian Reforms Undertaken in Various French-Speaking African Countries

4.3.2. Comparative Analysis of Different Reforms on Land Governance in French-Speaking Africa

4.4. Impact of Reforms on Community Land Management

4.5. Case Studies of Successful Reforms and Failed Selected Based on the Relevance of the Objectives Pursued and the Results Obtained

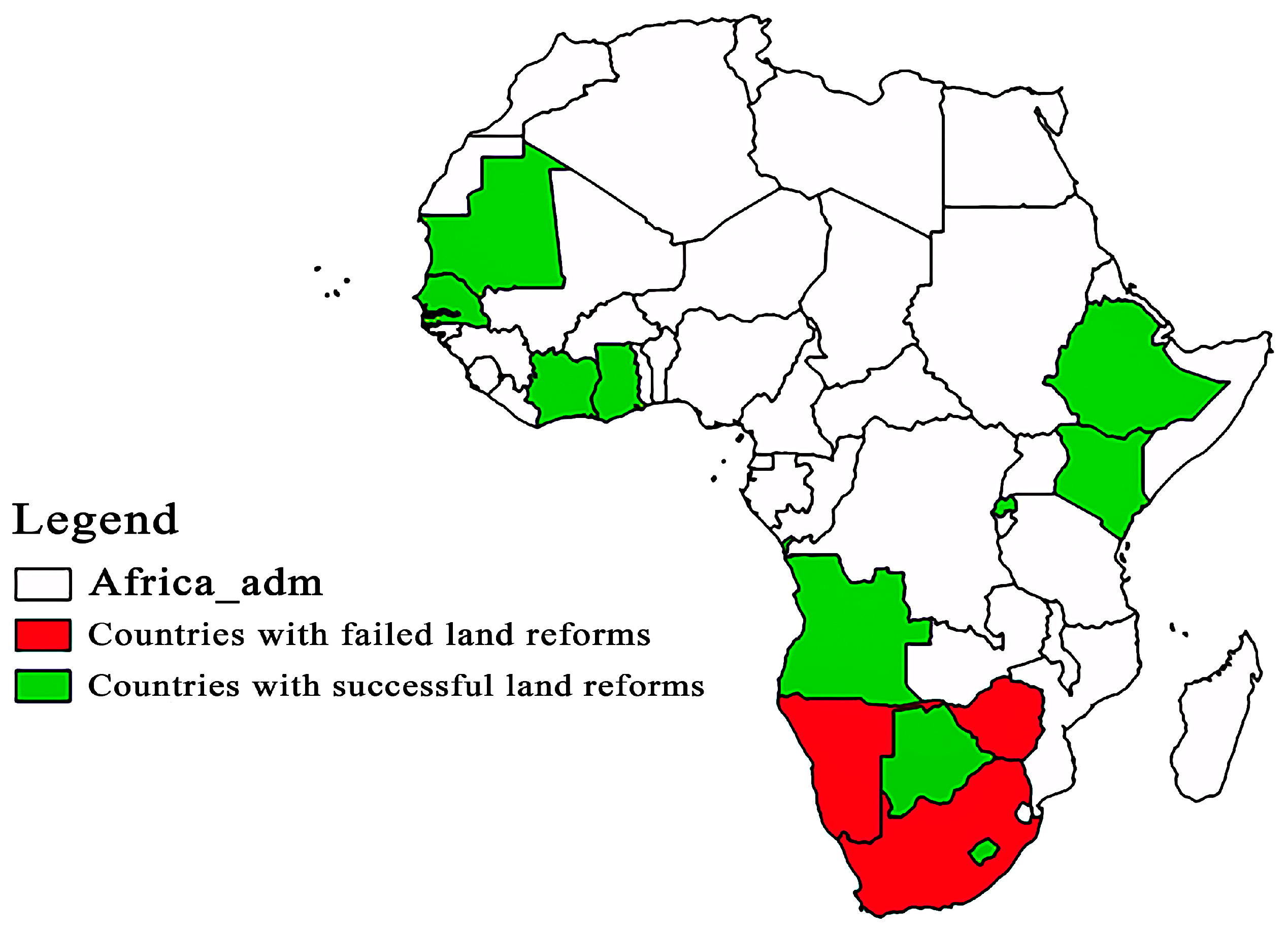

4.5.1. Spatial Analysis of Successful and Failed Reform Cases in Africa

4.5.2. Some Examples of Successful and Unsuccessful Reforms

4.6. Challenges for Sustainable Community Land Management

4.6.1. Land Conflicts

4.6.2. Access to Land and Securing Land Rights

4.6.3. Impact of Climate Change and Demographic Pressures

4.7. Strategies for More Effective Land Governance

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Country | Agrarian Reforms | Goals | Actors Involved in the Implementation Process | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benin | Law No. 2013-01 of 14 August 2013 relating to the land and property code in the Republic of Benin | This law reduces land insecurity, improves access to land for local populations and modernizes land management to combat the fragmentation of plots. | The Ministry of Finance through the National Agency for Estates and Heritage, local authorities, civil society organizations, technical and financial partners. | In an approach focused on rural areas and decentralization, the 2013 legal reform only reinforced the land registration procedure inherited from the colonial era. This led to a break with the recognition of customary land rights by favoring formal land registration mechanisms to the detriment of traditional practices. | [10,52,62,63,64] |

| Senegal | Law on the national domain adopted on 17 June 1964 (law 64–46) | The main objective of this law is to provide Senegal with a unified legal framework for land management. | The Ministry of Rural Development (state) and rural communities created by decree under the authority of the State. Procedure: All lands not classified in the public domain, not registered and whose ownership has not been transcribed to the mortgage registry constitute by right the national domain. | This law allowed for the nationalization of unregistered land, giving the state centralized control over a large part of the national territory. However, it also gave rise to tensions, particularly in areas where customary rights were predominant. | [6,64,65,66] |

| Law 2004-16 known as the Agro-Sylvo-Pastoral Orientation Law (LOASP) | It unambiguously aims to introduce new land governance assisted by the market. | Consultation of the state (under the authority of the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock) with professional agricultural organizations, non-governmental organizations, local elected officials, public and parapublic establishments, company civil society and partners in agro-sylvo-pastoral development. | This led to the modernization and diversification of agriculture. | [6,66,67] |

| Country | Agrarian Reforms | Goals | Actors Involved in the Implementation Process | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mali | Law No. 63-7/AN-RM of 11 January 1963, establishing the fundamental law on land and real estate matters | Provide a legal framework for the management of public and private lands and domains of the State, by regulating the ownership, occupation and use of land. | This involved the Ministry of State Property and Land Affairs. Principle: the absolute withdrawal of land and natural resource management powers from traditional authorities (such as village or community chiefs) and the centralization of their management under the authority of the state. | Land regulation and titling have been implemented unevenly, with disparities between urban and rural areas. | [57,68] |

| Law No. 06-45 on agricultural orientation of 5 September 2006 | Ensure that farmers, especially smallholders, have secure access to land to promote agricultural production. | Actors in the agricultural sector: professional agricultural organizations, the Chambers of Agriculture (the Ministry of Agriculture), and state and local authorities. This applies to two types of agricultural holdings: family farms and agricultural businesses (recognized and secure). | Attempts at land reform have since sought to resolve the tensions created by this law, notably by recognizing customary rights and decentralizing land management. | [68,85] | |

| Land and property management reform launched in Mali in 2014 | Improving land and land resource management in the country | Three ministries were involved: the Ministry of State Lands and Land Affairs, the Ministry of Agriculture, and the Ministry of the Environment. Other stakeholders: local authorities and local communities, farmers’ organizations, international donors and technical partners. This was a participatory and multi-stakeholder process aimed at modernizing land management, strengthening legal certainty and promoting inclusive and sustainable land governance. | This improves land security, modernizing legal and institutional frameworks | [86] | |

| Law No. 2017-001 of 11 April 2017 relating to agricultural land | Secure land rights for smallholder farmers, particularly in rural areas, and encourage sustainable agricultural investments. | The implementation mechanism is essentially based on the institutional and territorial framework of rural municipalities, in other words, on the synergy between policies, the land security actions of local actors and the development of complementarity between rural municipalities and local land management institutions. These are mainly village land commissions (customary chiefs) and the National Observatory of Agricultural Land (the Ministry of Rural Development). | The implementation of rural land registration has progressed, but it is hampered by local interest conflicts and traditional practices. | [68,87] | |

| Ivory Coast | Rural Land Law of 23 December 1998, revised in 2013, aimed at formalizing customary land rights and encouraging rural investment | Reserves rural land ownership for Ivorians. | This involved the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development and village communities. Principles: the issuance of land certificates, but it lack of knowledge of the registration and formalization of relations between holders of customary rights and non-owner operators. | It plays a key role in rural land management, but its implementation remains complex due to challenges such as land conflicts and slow procedures. | [69,70] |

| Law No. 2015-537 of 20 July 2015 on agricultural orientation of Ivory Coast | Provides for the implementation of a policy that aims to secure the rights of customary owners and occupants to keep young people and women in the territory on an identified land heritage and to enhance the value of land resources. | This involved the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (state), national institutions responsible for social cohesion, agricultural organizations and civil society organizations. Consultation for the implementation of this policy aimed at strengthening social cohesion between rural stakeholders. | This results in securing the rights of customary holders, enhancing the value of land resources, equitable access for men and women to said resource and its sustainable management. | [71] | |

| Burkina Faso | Law 034-2012/AN on agrarian and land reorganization (RAF) in Burkina Faso was adopted on 2 July 1984 | Marginalizes customary powers and promote “rational” land management based on the nationalization of land and the prohibition of the land market. | This involved several ministries (the Minister of Regional Planning and Decentralization, Minister of Economy and Finance, Minister of Housing and Urban Planning, Minister of Agriculture and Food Security, Minister of Animal and Fisheries Resources, Minister of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Minister of Equipment and Opening Up, Minister of Territorial Administration and Security, and Minister of Justice) in collaboration with local authorities and competent technical services. Implementation: The Raf had focused on urban land but had not proposed anything on rural land. There was no land management structure. There was no land registry. We relied on oral testimonies to attest to the ownership of one and the other. | The law has never been applied because Burkina Faso has never had the means to match its ambitions in terms of regional planning. | [10,72,73] |

| In June 2009, Law No. 0342009/AN of 16 June 2009, relating to rural land tenure | This law defines the land and property regime applicable to rural land and establishes the principles of land security for all rural land stakeholders, with an emphasis on the issuance of rights. | The ministries concerned were Finance, Territorial Administration and Decentralization, and Agriculture. At the population level, the implementation of this law is based on the establishment, at the municipal level, of a rural land service (SFR) and, at the village level, of a Village Land Commission (CFV) attached to the Village Development Committee (CVD). | This results in the distribution of national lands between domains (of the state, local authorities and individuals), land charters, the creation of structures at the communal and village levels, consultation bodies at the communal level, the creation of a village body responsible for resolving conflicts, and the recognition of the legitimate rights of populations, which gives the right to a certificate of land possession. | [72] |

References

- Groupe de la Banque Mondiale. Améliorer la Gouvernance Foncière en Afrique Pour Encourager le Partage de la Prospérité. 2013. Available online: https://www.banquemondiale.org/fr/region/afr/publication/securing-africas-land-for-shared-prosperity (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Tsinda, A.; Chikolwa, N. Stratégie de Gouvernance Foncière. 2022. Available online: https://orfao.uemoa.int/sites/default/files/2023-12/au-giz2022-fr-strategie-gouvernance-fonciere-2023-2032-low-res.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Sine, D.; Sine, A. La Gouvernance Foncière en Afrique. 2023. Available online: https://www.geometres-francophones.org/5e8sef5sdgf/uploads/2019/12/FGF2019-SESSION1_SINE.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Commission Economique Pour L’afrique. Politiques foncières en Afrique: Un cadre pour le renforcement des droits fonciers, l’amélioration de la productivité et des conditions d’existence. In Cadre et Lignes Directrices sur les Politiques Foncières en Afrique; Commission Economique Pour L’afrique: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2010; pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Anseeuw, W.; Bouquet, E. Rénovation des Politiques Publiques et Enjeux de la Réforme Foncière sur les Terres Communautaires en Afrique du Sud. 2010. Available online: https://www.foncier-developpement.fr/wp-content/uploads/politique-fonciere-afrique-sud-FR.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Ndiaye, A. La Réforme des Régimes Fonciers au Sénégal: Condition de L’éradication de la Pauvreté Rurale et de la Souveraineté Alimentaire. 2011. Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-00653556v1 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Ntampaka, C. Gouvernance Foncière en Afrique Centrale. Gouvernance Foncière en Afrique Centrale Dr. Charles Ntampaka Décembre, 2008. Organisation des Nations Unies Pour L’alimentation et Agriculture. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/1226cbb7-de55-41d7-9316-e083820417b7/content (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Bron-Saidatou, F.; Yankori, S.S. Les Terres Communautaires… ou Terrains de Chefferie, Terres Pastorales, Ressources Forestières. 2005. Available online: https://duddal.org/files/original/059b31fd6a87afff5dc28a86e2a343d255c8f8fb.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Benkahla, A.; Seck, S.; Ba, C.O. Pour une Véritable Concertation sur les Enjeux et Objectifs D’une Reforme Foncière au Sénégal. 2011. Available online: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/450rkf (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Lavigne Delville, P. Les réformes de politiques publiques en Afrique de l’Ouest, entre polity, politics et extraversion. Eau potable et foncier en milieu rural (Bénin, Burkina Faso). Gouv. Et Action Publique 2018, 7, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UA; BAD; CEA. Politiques Foncières en Afrique: Un Cadre Pour le Renforcement des Droits Fonciers, L’amélioration de la Productivité et des Conditions D’existence. 2010. Available online: https://data.landportal.info/pt/node/13068?page=11 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Sonkoue, M.; Ngono, R.; Bolin, A. Résoudre les Conflits Fonciers par le Dialogue: Leçons aux Marges D’une aire Protégée du Cameroun; IIED: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grislain, Q.; Bourgoin, J.; Magrin, G.; Burnod, P.; Anseeuw, W. Les observatoires fonciers en Afrique: Un outil de gouvernance des territoires face aux réalités du terrain. Bull. L’association Géogr. Fr. 2023, 100, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basserie, V.; D’Aquino, P. Sécurisation et Régulation Foncières: Des Enjeux aux Outils. Quelques Obstacles à la Cohérence des Politiques; Foncier Développement: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kassis, G. Une Analyse Économique de la Gouvernance du Foncier Agri-Alimentaire: Des Changements Institutionnels aux Perspectives D’avenir. Doctoral Dissertation, Université Grenoble Alpes, Grenoble, France, 2023; pp. 1–225. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, N. Terres Agricoles Périurbaines: Une Gouvernance Foncière en Construction; Quae: Versailles, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thiel, A.; Garrick, D.E.; Blomquist, W.A. (Eds.) Governing Complexity: Analyzing and Applying Polycentricity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kassis, G.; Bertrand, N. Action collective foncière et émergence de projets agri alimentaires dans le dispositif PAEN. Le cas de l’aire métropolitaine lyonnaise. Écon. Rural. 2023, 383, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S. Défendre l’espace agricole: L’accumulation des textes. In Terres Agricoles Périurbaines. Une Gouvernance Foncière en Construction; Editions Quae: Versailles, France, 2013; pp. 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis, M.D. An introduction to IAD and the language of the Ostrom workshop: A simple guide to a complex framework. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. La gouvernance foncière. La terre, la pêche et les forêts Nos précieuses ressources naturelles. Agissons pour sa mise en œuvre! In Directives Volontaires pour une Gouvernance Responsable des Régimes Fonciers Applicables aux Terres, aux Pêches et aux Forêts dans le Contexte de la Sécurité Alimentaire Nationale; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bierschenk, T.; Olivierde Sardan, J.-P. (Eds.) States at Work. Dynamics of African Bureaucracies; Brill: Leyde, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Cling, J.-P.; Razafindrakoto, M.; Roubaud, F. La Banque mondiale et la lutte contre la pauvreté: “Tout changer pour que tout reste pareil?”. Polit. Afr. 2002, 87, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsen, R. The World Bank’s Good Governance Agenda. Narratives of Democracy and Power. In Ethnographies of Aid. Exploring Development Texts and Encounters; Gould, J., Marcussen, H.S., Eds.; Roskilde University: Roskilde, Denmark, 2004; pp. 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bergamaschi, I. Mali: Patterns and Limits of Donor-driven Ownership. In The Politics of Aid. African Strategies for Dealing with Donors; Whitfield, L., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 217–245. [Google Scholar]

- Ouattara, S. La Politique Foncière au Burkina Faso: Une Élaboration Participative? Inter-Réseaux. 2008. Available online: https://www.inter-reseaux.org/publication/41-42-lagriculture-en-quete-de-politiques/la-politique-fonciere-au-burkina-faso-une-elaboration-participative/ (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- OXFAM International. Pourquoi les Droits Fonciers Collectifs nous Concernent Toutes et tous | Oxfam International. 2023. Available online: https://www.oxfam.org/fr/agir/campagnes/defendons-le-droit-la-terre/pourquoi-les-droits-fonciers-collectifs-nous-concernent-toutes-et-tous (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Kenfack Essougong, U.P.; Teguia SJ, M. How secure are land rights in Cameroon? A review of the evolution of land tenure system and its implications on tenure security and rural livelihoods. GeoJournal 2019, 84, 1645–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoh, A.J.; Akiwumi, F. Colonial legacies, land policies and the millennium development goals: Lessons from Cameroon and Sierra Leone. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolcerocca, A. State property vs. customary ownership: A comparative framework in West Africa. J. Peasant. Stud. 2022, 49, 1064–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, P. Conflicts over Land and Threats to Customary Tenure in Africa; CID Working Paper Series; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dachaga, W.; de Vries, W.T. Land tenure security and health nexus: A conceptual framework for navigating the connections between land tenure security and health. Land 2021, 10, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.; Augustinus, C. Framework for Evaluating Continuum of Land Rights Scenarios. In Securing Land and Property Rights for All; UN-Habitat and GLTN: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Land Tenure and Rural Development; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- VanGelder, J.L. What tenure security? The case for a tripartite view. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittal, J. A new conceptual model for the continuum of land rights. S. Afr. J. Geomat. 2014, 3, 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Simbizi, M.C.D.; Bennett, R.M.; Zevenbergen, J. Land tenure security: Revisiting and refining the concept for Sub-Saharan Africa’s rural poor. Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K. Land Policies for Growth and Poverty Reduction; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ege, S. Land tenure insecurity in post-certification Amhara, Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 2017, 64, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnot, C.D.; Luckert, M.K.; PC Boxall, P.C. What Is tenure security? Conceptual implications for empirical analysis. Land Econ. 2011, 87, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weppe, X.; Warnier, V.; Lecocq, X.; Fréry, F. When the premises of a theory induce bad practices. JB Barney’s “Resource theory”. Rev. Fr. Gest. 2012, 38, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnier, V.; Weppe, X.; Lecocq, X. Extending resource-based theory: Considering strategic, ordinary and junk resources. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 1359–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Mahoney, J.T. Resource-based and property rights perspectives on value creation: The case of oil field unitization. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2002, 23, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, J.L.; Combes-Motel, P.; Schwartz, S. Un survol de la théorie des biens communs. Rev. D’économie Dév. 2016, 24, 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.E.; Ankersen, T.; Barchiesi, S.; Meyer, C.K.; Altieri, A.H.; Osborne, T.Z.; Angelini, C. Governance and the mangrove commons: Advancing the cross-scale, nested framework for the global conservation and wise use of mangroves. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 312, 114823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, K.; Gruby, R.L. Polycentric systems of governance: A theoretical model for the commons. Policy Stud. J. 2019, 47, 927–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–241. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.0 (Updated July, 2019). Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Ishtiaque, A. US farmers’ adaptations to climate change: A systematic review of adaptation-focused studies in the US agriculture context. Environ. Res. Clim. 2023, 2, 022001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Santesso, N.; Guyatt, G.H. Systematic reviews of the literature: An introduction to current methods. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2024, kwae232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delville, P.L. Harmonising formal law and customary land rights in French-speaking West Africa. In Evolving Land Rights, Policy and Tenure in Africa; Toulmin, C., Quan, J., Eds.; DFID/IIED/NRI: London, UK, 2000; pp. 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- AlRyalat, S.A.S.; Malkawi, L.W.; Momani, S.M. Comparing bibliometric analysis using PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. JoVE (J. Vis. Exp.) 2019, e58494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selçuk, A.A. A guide for systematic reviews: PRISMA. Turk. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 57, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappy. Les Enjeux de la Gouvernance Foncière Locale en Afrique de L’ouest et à Madagascar, 2024. Gret. Available online: https://gret.org/les-enjeux-de-la-gouvernance-fonciere-locale-en-afrique-de-louest-et-a-madagascar/ (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Ouedraogo, H.M.G. De la connaissance à la reconnaissance des droits fonciers africains endogènes. Études Rural. 2011, 187, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djiré, M.; Kéita, A. Cadre D’analyse de la Gouvernance Foncière Mali; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baro, D.M.; Diagana, I.; Kader, I.A.; Konté, B.; Wane, B.; Ndiaye, A.; Mariam, L.; Abdellatif, M.V.O. Contribution à l’Amélioration de la Politique Foncière en Mauritanie à Travers L’usage du Cadre d’Analyse de la Gouvernance Foncière (CAGF). 2014. Available online: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/a91b90185037e5f11e9f99a989ac11dd-0050062013/related/Mauritania-FINAL-Report-Oct2014.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Tribillon, J.-F. Les régimes fonciers en Afrique subsaharienne. L’Économie Polit. 2018, 78, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zola, X. La Réforme Foncière pour Soutenir les Jeunes et les Femmes et Favoriser la Sécurité Alimentaire au Bénin. 2017. Available online: https://archive.uneca.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-documents/LPI/CLPA_2017/Presentations/la_reforme_fonciere_pour_soutenir_les_jeunes_et_les_femmes.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Roe, D.; Nelson, F.; Sandbrook, C. Gestion Communautaire des Ressources Naturelles en Afrique: Impacts, Expériences et Orientations Futures; IIED: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Avohoueme, M.B.; Mongbo, R.L. Politique publique locale foncière au Benin: Une catégorie sous l’emprise de l’aide internationale. Sci. Hum. 2016, 1, 1–23. Available online: http://publication.lecames.org/index.php/hum/article/view/577/405 (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Droit Afrique. Bénin: Code Foncier et Domanial Loi n°2013-01 du 14 Janvier 2013. Modifiée par la loi n°2017-15 du 26 Mai 2017. Available online: https://www.droit-afrique.com/uploads/Benin-Code-2013-domanial-et-foncier-MAJ-2017.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- OHADA.com. Réussir la Réforme Foncière: Le Code Foncier du Bénin, 2016. OHADA.com. Available online: https://www.ohada.com/actualite/2859/reussir-la-reforme-fonciere-le-code-foncier-du-benin.html (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Fall, M.L. La Réforme Foncière. 2004. Available online: https://www.geometres-francophones.org/5e8sef5sdgf/uploads/2018/12/Session3-04-Fall.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Hassan, S. Les Dernières Évolutions dans L’accès au Foncier en Afrique de L’ouest; L’Organisation pour l’Alimentation et l’Agriculture (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Diouf, N.C. Concertation Paysanne Pour L’influence de la loi D’orientation Agro-Sylvo Pastorale au Sénégal; IIED: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Coulibaly, M. Une Nouvelle loi Pour Sécuriser les Terres au Profit des Paysans Maliens; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2017; Available online: https://www.iisd.org/articles/insight/une-nouvelle-loi-pour-securiser-les-terres-au-profit-des-paysans-maliens (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Chauveau, J.-P. La Réforme Foncière de 1998 en Côte d’Ivoire à la Lumière de L’histoire des Dispositifs de Sécurisation des Droits Coutumiers: Une Economie Politique de la Question des Transferts de Droits Entre Autochtones et “Etrangers” en Côte D’ivoire Forestière; Institut de Recherche pour le Développement: Marseille, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- et Dutheuil, H. Comment Réinventer le Système Foncier Rural en Côte d’Ivoire. Une Etude Multiculturelle et Multidisciplinaire; Une Vision Libérale du Progrès; Audace, Institut Afrique: Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 2016; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Direction du Foncier Rural. Déclaration de Politique Foncière Rurale de la Cote d’Ivoire; Direction du Foncier Rural: Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hochet, P. Les enjeux de la mise en œuvre de la loi portant régime foncier rural au Burkina Faso. In 57: Foncier: Innover Ensemble; Inter-réseaux-Développement rural: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gouvernement du Burkina Faso. LOI N°034-2012/AN Portant Réorganisation Agraire et Foncière au Burkina Faso, 2012. Décret n°2012-716/PRES Promulguant la loi n°034-2012/AN du 02 Juillet 2012 Portant Réorganisation Agraire et Foncière au Burkina Faso. Available online: https://orfao.uemoa.int/sites/default/files/2022-11/Brochure%20Loi%20RAF%20034-2012%20AN%20BD.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Pennec, J. La Rénovation des Cadres Juridiques de Gouvernance Foncière Dans les Pays en Développement: Étude de cas Croisée du Niger, d’Haïti et de l’Afrique du Sud. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Bretagne Occidentale, Brest, France, 2023. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-04257339 (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Karsenty, A.; Bertrand, A. La Sécurisation Foncière en Afrique: Pour une Gestion Viable des Ressources Renouvelables; KARTHALA Editions: Paris, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Delville, P.L.; Colin, J.-P.; Ka, I.; Merlet, M. Étude Régionale sur les Marchés Fonciers Ruraux en Afrique de L’ouest et les Outils de leur Régulation. 2017. Available online: http://www.foncier-developpement.fr/publication/etude-regionale-marches-fonciers-ruraux-afrique-de-louest-outils-de-regulation/ (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Dossa, K.F.; Miassi, Y.E. Land Management and Adoption of Biodiversity Conservation Approaches. Am. J. Environ. Clim. 2024, 3, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niang, M.M. La Mise en Place des Réformes Agro-Foncières. 2005. Available online: https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/doc34-07/02620.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Slayi, M.; Zhou, L.; Thamaga, K.H.; Nyambo, P. The Role of Social Inclusion in Restoring Communal Rangelands in Southern Africa: A Systematic Review of Approaches, Challenges, and Outcomes. Land 2024, 13, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teketay, D.; Kashe, K.; Madome, J.; Kabelo, M.; Neelo, J.; Mmusi, M.; Masamba, W. Enhancement of diversity, stand structure and regeneration of woody species through area exclosure: The case of a mopane woodland in northern Botswana. Ecol. Process. 2018, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finca, A.; Linnane, S.; Slinger, J.; Getty, D.; Samuels, M.I.; Timpong-Jones, E.C. Implications of the breakdown in the indigenous knowledge system for rangeland management and policy: A case study from the Eastern Cape in South Africa. Afr. J. Range Forage Sci. 2023, 40, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gxasheka, M.; Beyene, S.T.; Mlisa, N.L.; Lesoli, M. Farmers’ perceptions of vegetation change, rangeland condition and degradation in three communal grasslands of South Africa. Trop. Ecol. 2017, 58, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Mbaiwa, J.E.; Mbaiwa, T.; Siphambe, G. The community-based natural resource management programme in southern Africa–promise or peril?: The case of Botswana. In Positive Tourism in Africa; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Tayou Tayou, R. The Impact of Rule of Law and Property Rights On Development and Economic Growth: A Comparative Analysis of Cameroon and Côte d’Ivoire. Master’s Thesis, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bélières, J.F. Agriculture Familiale et Politiques Publiques au Mali; UMR Art-Dev: Montpellier, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, M. Chronique d’une réforme foncière dans la trajectoire politique du Mali. Anthropol. Dév. 2018, 48–49, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministère du développement rural. Politique Fonciere Agricole du Mali (PFA). Ministère du Développement Rural, Sécretariat Général. République du Mali. 2020. Available online: https://orfao.uemoa.int/sites/default/files/2020-10/01.%20PFA%20Corrig%C3%A9e%20Version%20SGG%20finale1.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2024).

| Country | Goals | Similarities and Differences | Actors Involved | Results Obtained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benin | Reduction in land tenure insecurity and modernization of land management | Similarity with the case of Senegal Centralized approach and marginalization of customary rights | Ministry of Finance, National Land Agency, local authorities, technical partners | Reducing land fragmentation, debates on the marginalization of customary rights, resistance of rural communities |

| Senegal | Nationalization of unregistered land, market-oriented agricultural modernization (LOASP, 2004) | Similarity with Benin and Mali Centralized approach and agricultural orientations | State (Ministry of Rural Development), professional agricultural organizations, NGOs, local officials and international partners. | Creation of tensions related to customary rights, reduction in conflicts thanks to inclusive approaches with the LOASP 2004 |

| Mali | Securing smallholder land rights, institutional modernization | Mixed approach allowing partial recognition of customary rights, distinct from the case of Senegal and Benin Decentralization similar to the case of Burkina Faso | State through several ministries, rural communities (village land commissions) | Some progress slowed by local practices and institutional tensions |

| Ivory Coast | Formalization of customary rights, social inclusion and land tenure security for sustainable agricultural land management | In terms of similarity, this country adopts approach close to that of Mali (securing land rights) and Senegal (agricultural orientation) In terms of difference, reforms here prioritize inclusive approach (social cohesion) | State (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development), village communities and agricultural organizations. | Valorization of land resources, social cohesion, delays in the implementation of reforms and persistence of land conflicts |

| Burkina Faso | Securing land rights, promoting rural investment | Objective of securing land rights similar to that of Mali and Ivory Coast, but stands out through an approach focused on strong decentralization with establishment of village commissions for land management | The ministries concerned (Finance, Territorial Administration and Decentralization, Agriculture); Population (Rural Land Service SFR), rural communities (Village Land Commission) | Practical challenges in managing land conflicts, decentralization hampered by resource constraints |

| Country | Reforms | Case or Objective (Success or Failure) |

|---|---|---|

| Concrete cases of successful reforms | ||

| Ethiopia and Madagascar | Decentralization of land administration systems | In some areas, land administration responsibilities are delegated to local governments, facilitating the registration and certification of household land holdings [2]. |

| Ghana | Considering customary land tenure systems | The legalization of the customary land tenure system, which governs more than 80% of rural land, has led to the establishment of Customary Land Secretariats (CLSs), strengthening land administration capacities and ensuring the transparent delivery of land services based on customary and statutory land rights [2]. |

| Rwanda | Digitization of the land administration system | Rwanda has modernized its land administration system by adopting geographic information systems (GISs), reducing land transfer time to 7 days compared to an average of over 40 days in many other African countries [2]. |

| Mauritius | Digitization of the land administration system | Like Rwanda, Mauritius has digitalized its land system, improving the efficiency of land transactions [2]. |

| Concrete cases of failed reforms | ||

| South Africa and Zimbabwe | Land redistribution reforms | Indigenous land rights reforms have also been experimented with in these African countries through various measures such as the issuance of individual and collective land titles or the appropriation of land to produce cash crops; they have, however, had limited success due to the persistence of social and cultural attachment to the land and, in some cases, due to contestations and conflicts [2]. |

| Strategies | How to Get There | References |

|---|---|---|

| Capacity building | Training and skills development, infrastructure improvement (road infrastructure, administrative infrastructure such as land management offices, land documentation centers, digital tools for land registration), strengthening interinstitutional coordination | [1,3,7,16,56,57,60,75,78] |

| Integration of land and customary rights | Legal recognition of customary rights, participation of local communities | |

| Transparency and the fight against corruption | Transparency in land management processes, strengthening of control and sanction mechanisms | |

| Improved conflict resolution | Creation of local conflict resolution mechanisms, strengthening the role of justice | |

| Participatory and inclusive approach | Stakeholder engagement, awareness and education | |

| Adoption of flexible and adaptive policies | Flexibility in the application of laws | |

| Sustainable development and environmental protection | Promotion of sustainable agricultural practices, protection of community lands against excessive exploitation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bah, I.; Dossa, K.F. Land Governance in French-Speaking Africa: Comparative Analysis of Legal and Institutional Reforms for Sustainable Management of Community Lands. Land 2025, 14, 276. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14020276

Bah I, Dossa KF. Land Governance in French-Speaking Africa: Comparative Analysis of Legal and Institutional Reforms for Sustainable Management of Community Lands. Land. 2025; 14(2):276. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14020276

Chicago/Turabian StyleBah, Idiatou, and Kossivi Fabrice Dossa. 2025. "Land Governance in French-Speaking Africa: Comparative Analysis of Legal and Institutional Reforms for Sustainable Management of Community Lands" Land 14, no. 2: 276. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14020276

APA StyleBah, I., & Dossa, K. F. (2025). Land Governance in French-Speaking Africa: Comparative Analysis of Legal and Institutional Reforms for Sustainable Management of Community Lands. Land, 14(2), 276. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14020276