Abstract

Population distribution and socioeconomic development are pivotal elements for achieving national sustainable development and represent critical aspects of the spatiotemporal heterogeneity and imbalance within the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China”. This study examines the spatial distribution patterns and evolutionary characteristics of the population from 1935 to 2020 and economic dynamics from 2010 to 2020 in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” through methods such as spatial interpolation, spatial autocorrelation, and other advanced spatial analytical techniques. Furthermore, the article explores the coordination between population and economic development within this region by employing the gravity index and inconsistency index. The findings reveal that the population distribution in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” lacks significant aggregation characteristics, with pronounced spatiotemporal differentiation observed along the “Hu Line”. From 2010 to 2020, socioeconomic indicators exhibited substantial disparities in spatial agglomeration, characterized by marked heterogeneity. Regarding the coordination between population and economic dynamics, this study highlights a progressive reduction in the distance between the centers of population and economic gravity, accompanied by a declining deviation trend. This indicates an improvement in balance and an increase in the degree of coupling over time.

1. Introduction

The population and economy of a region are closely interrelated as core issues of sustainable development [1,2]. With the rapid development of regional economy and urbanization, population issues, economic development issues, and the coordinated development of population and economy have become increasingly prominent [3,4]. Population growth is both a cause and a result of economic development; it can have a positive impact on economic development, but excessive population density can also inhibit socioeconomic development [5,6]. In 1935, the famous Chinese geographer Mr. Hu Huanyong elaborated on the spatial and temporal differences between China’s population distribution and socioeconomic development in his article “The Distribution of Population in China”, which also opened a new chapter in the study of China’s population and economic geography [7]. In order to meet the needs of China’s socioeconomic development and ecological civilization construction in the new era, Academician Guo Huadong proposed the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” in December 2017. According to the requirements of “Beautiful China”, in the Mid-Spine Belt region, ecological civilization construction should be taken as the leading factor, and it should be integrated into all aspects and the whole process of economic construction, political construction, cultural construction, and social construction [8]. The proposal of this scientific issue effectively promoted the research work related to China’s sustainable development. Therefore, exploring the spatial coordination between population distribution and economic development is of great significance for promoting national development strategies, promoting the coordinated development of regional population, society, economy, resources, and the environment, and thus realizing high-quality development in the region.

In order to explore the potential risks of economic development (e.g., to society and medical security systems) caused by the transformation of population reproduction, many studies have conducted comprehensive social analyses based on population and economic data. Stein Emil Vollset et al. predicted future population sizes and point out that, against the backdrop of population decline, some countries will maintain their population sizes by improving policies to promote economic development and consolidate political interests [9]. David E. Bloom et al. made predictions on the number of people aged 60 and above in various countries over the next four decades, analyzed the potential risks to pension systems and healthcare services in combination with economic growth rates, and proposed measures to address these risks [10]. Megan E. Heim LaFrombois et al. analyzed the mismatch between population loss and urban planning strategies in 35 shrinking cities in the United States. The survey results indicated that population loss is not a decisive factor in comprehensive urban planning [11]. Jane P. Messina et al. used demographic and socioeconomic data combined with climate data to predict dengue fever virus adaptation and population exposure risk to cope with future dengue fever risks [12]. Linda Marcia Mendes Delazeri et al. studied the impact of different economic and climate scenarios on the rural population changes in the northeast region of Brazil and put forward corresponding policy-making suggestions [13].

In recent years, research on the relationship between regional population and economy in China and the evolution of their spatial patterns has become increasingly in-depth, with an increasing number of research methods [14,15]. Wang et al. used the gravity method, geographical concentration, and the inconsistency index to study the agglomeration characteristics of population and economy in the Yangtze River Delta and their spatial distribution relationship, pointing out that the spatial distribution relationship between population and economy will tend towards coordinated development [16]. Mao et al. analyzed the impact of the floating population distribution in Zhejiang Province on the level of urbanization, finding that the floating population has improved the level of urbanization in Zhejiang Province [17]. Cheng et al. studied the relationship between population distribution and topography in the Wujiang River Basin of Guizhou Province, concluding that in the relationship between altitude and population, the highest population distribution occurs between 1000 and 1400 m, and noting that population density decreases with increasing slope and topographic relief [18]. Jiang et al. analyzed the spatiotemporal evolution and influencing factors of population distribution in the Pearl River–Xijiang Economic Belt, showing that GDP, level of public services, income level of residents, and industrial structure all have a positive impact on the population distribution in the economic belt [19]. Liu Tao et al. analyzed the spatial pattern and concentration trend of China’s population distribution from 2000 to 2020, finding that China’s population distribution still maintains the basic pattern of being “dense in the east and sparse in the west”, with a continuously strengthening trend of spatial agglomeration in the southeastern half [20]. Zhen et al. used the population agglomeration index and relative population change to study the population distribution trend in China’s border areas, and proposed that the population development strategy of “moderate agglomeration” and “moderate evacuation” should be adopted in specific areas [21]. Liang et al. used the regional center of gravity model to analyze the changes in population and economic center of gravity since the reform and opening China up, and used the geographic detector to analyze the impact of economic and social factors on population density and economic growth. They described multiple stages of population and economic center of gravity movement, found an increasing development gap between the north and the south, and analyzed the factors affecting the distribution of Chinese population density and economic development [22].

Combining domestic and international research results, population redistribution in China has similarities with other countries in the world. Regions with a higher level of economic development can provide a large number of job opportunities and better living conditions, attracting population inflows. Regions rich in resources can attract a large number of people to engage in resource-related industries locally. The government’s regional development policies can guide population distribution and promote the reasonable flow of population to underdeveloped areas. With the advancement of urbanization, a large number of rural populations have transferred to cities. In addition, population redistribution in China also has special characteristics. Population distribution in China shows a distinct “Hu Huanyong Line” feature, with a dense population on the east side and a sparse population on the west side. In contrast, other countries have their own unique population distribution patterns, such as Russia, where the population is mainly concentrated in the economically and culturally developed European part [23]. China is a populous country. Although the population is currently experiencing negative growth, the total population is still very large. In contrast, some developed countries such as Japan have a small total population, are experiencing negative growth, and are facing serious problems, such as population aging and labor shortages [24]. In some developing countries, such as some countries in Africa, rapid population growth has brought huge pressure on resources, the environment, and social development [25]. The Chinese government has played a strong guiding role in population distribution. In contrast, some Western countries emphasize the role of market mechanisms in population distribution and have relatively less government intervention.

Since the reform and opening up, with the rapid development of China’s social economy, the unbalanced flow of population among cities has accelerated, and the spatial and temporal pattern of population distribution has undergone tremendous changes. The regional economic differences in China have been continuously expanding, becoming a major issue that must be addressed for the sustained, healthy, and rapid development of the national economy [26,27,28]. Therefore, this study uses three periods of data from 2010 to 2020 for the three major industries in China and nine periods of population data from 1935 to 2020 as data sources. It adopts spatial interpolation, centroid migration, spatial autocorrelation, the inconsistency index, and other spatial analysis methods to reveal the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of population and socioeconomic development in the “beautiful China midline” and the spatiotemporal coupling relationship between population and economy. The above research reveals the current situation of unbalanced population distribution and economic development within the region, and provides a theoretical basis for determining the population scale in regional urban planning, formulating reasonable development strategies, and promoting sustainable development policies related to population and economy, which has important practical significance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

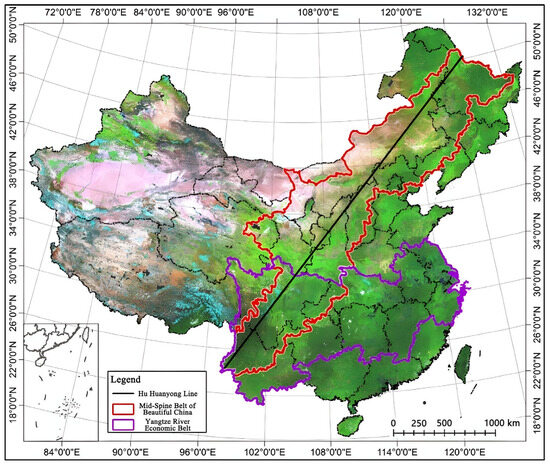

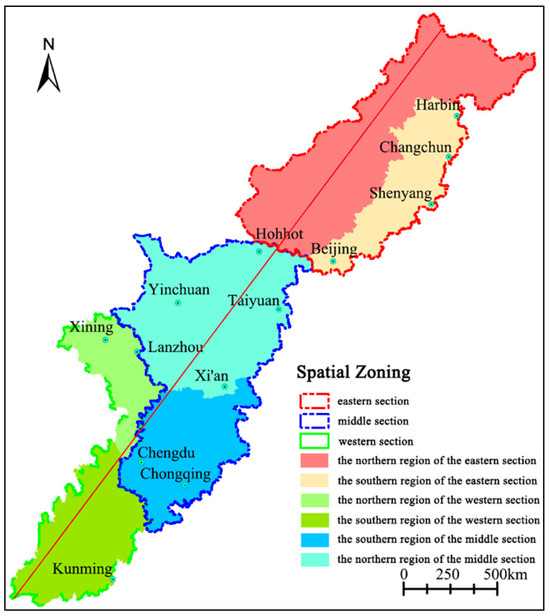

As shown in Figure 1, the “Beautiful Mid-Spine Belt” is located at the “mid-spine” of China’s territory (running 45° from northeast to southwest across the country), spanning longitude 97°25′ E to 133°21′ E and latitude 23°36′ N to 50°57′ N. The “Mid-Spine Belt” is an envelope zone formed by the displacement of China’s population density mutation line (“Hu Huanyong Line”) over the past 80 years, with its natural human background being an ecologically fragile agro-pastoral ecotone. The core area involves nine provinces, including Heilongjiang, Jilin, Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Gansu, Ningxia, Yunnan, and Sichuan, with a total area of about 2.444 million km2, accounting for about 25.4% of China’s land area. The terrain within the region is complex, encompassing five basic types—plateau, mountain, hill, plain, and basin—with significant topographic relief, mainly showing a trend of being lower in the northeast and higher in the southwest. The “Mid-Spine Belt” is dominated by a temperate monsoon climate north of the Qinling Mountains, with annual precipitation ranging from 400 to 800 mm and an average annual temperature of 5.97 °C. Most of the area south of the Qinling Mountains has a subtropical monsoon climate, with annual precipitation ranging from 1000 to 1500 mm and an average annual temperature of 12.98 °C. In 2020, the total population of the “Mid-Spine Belt” was 345 million, accounting for about 24.64% of China’s total population, and the region’s gross domestic product was CNY 19.81 trillion, accounting for about 20.04% of the national GDP (source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, NBSPRC (www.stats.gov.cn)).

Figure 1.

“Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” spatial zoning.

According to the “National New Urbanization Plan (2014–2020)”, the country will steadily build 19 urban agglomerations in the future, and the “Mid-Spine Belt” will be home to more than 10 of them. Since “Western Development” and the construction of urban agglomerations were proposed, the living environment of the “Mid-Spine Belt” has undergone significant changes. At the same time, due to the long-term pursuit of economic growth and the expansion of construction space, the quality of the living environment in different regions varies greatly. Therefore, by analyzing the living environment of the “Mid-Spine Belt”, we can provide people with new places for living, working, and leisure, which will also become an important link in achieving China’s sustainable development goals and a strategic focus for solving the unbalanced and inadequate development between the east and west of the “Hu Huanyong Line”.

2.2. Data Sources

The data used in this study include nine sets of national county-level population statistics from 1935, 1953, 1964, 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, 2015, and 2020, three sets of national county-level socioeconomic data from 2010, 2015, and 2020, and national county-level administrative division vector data. The population data from 1980 to 2020 and the economic data of China’s primary, secondary, and tertiary industries from 2010 to 2020 are from the China Statistical Yearbook published by the National Bureau of Statistics. The population data for 1990, 2000, and 2010 are, respectively from the fourth, fifth, and sixth national population censuses. The county-level administrative division vector data are from the 1:1 million vector map provided by the National Basic Geographic Information Center. In different periods, administrative boundaries have been locally adjusted according to economic development needs. To effectively reflect the continuity and changing trends of population distribution in each period, this study performs spatial correlation, data revision, and inverse distance weighted spatial interpolation on the population distribution data and administrative division data (https://www.webmap.cn).

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Analysis of Population Distribution and Social and Economic Balance

The population and economic centers of gravity can reflect the spatial differences and imbalances in population distribution and economic development levels of a region from a different perspective. The mathematical expression is as follows [29,30]:

where n represents the number of county-level administrative units; X and Y represent the spatial locations of the population and economic centers of the entire study area; Xi and Yi represent the spatial locations of the center of the ith county-level unit; and Pi represents the population or GDP of the ith county-level unit.

2.3.2. Spatial Clustering Analysis of Population Distribution and Social Economy

To deeply reflect the overall spatial correlation between population and economy and further explore the intrinsic link between and change process of population and economic spatial distribution within the region, a spatial autocorrelation analysis method based on Queen’s adjacency spatial weights is adopted to explore the degree of aggregation and dispersion of population distribution and socio-economic factors. Spatial autocorrelation is divided into global autocorrelation and local autocorrelation.

The Moran’s I (Moran’s index) is used to test whether there is a correlation between adjacent areas within the entire study area. The range of I values is [−1, 1]. When the I value is greater than 0, the population distribution tends towards spatial agglomeration, indicating a positive correlation; when the I value is less than 0, the population distribution tends to be dispersed. The closer the absolute value of I is to 1, the higher the correlation degree of population distribution. When the I value is close to 0, it indicates that the adjacent spatial units are mainly distributed in a random state, or there is no spatial autocorrelation between adjacent spatial units. Its mathematical expression is [31,32,33]

where n represents the number of county-level administrative units in the study area, xi and xj represent the population density of the ith and jth county-level units, respectively, the average value of population density x is presented, and Wij is the spatial weight.

The local Moran’s I (LISA) measure can be used to test the degree of correlation between each county unit and its neighboring units. The LISA agglomeration map is mainly divided into four different spatial correlation types: high–high, low–low, low–high, and high–low. The Moran’s I scatter plot describes the quadrant where each county’s population density is located, and the four quadrants correspond to the four spatial correlation types between the county unit and its neighboring units: the first and third quadrants are positively correlated, respectively, with the high–high and low–low types; the second and fourth quadrants are negatively correlated, respectively, with the low–high and high–low types. The slope of the line represents the Moran’s I index. The mathematical expression for local spatial autocorrelation is [32,33,34,35,36]

The four quadrants of the Moran’s I scatter plot correspond to high–high clustering, low–low clustering, high–low clustering, and low–high clustering, respectively. This corresponds to the LISA clustering map and reflects the spatial association between the four types of analysis units and their neighboring units.

2.3.3. Coupling Analysis of Population Distribution and Economic Development

The Coupling and Unbalance Index of Population and GDP (CUP) refers to the ratio of the proportion of population in a certain region to the proportion of GDP, which can reflect the degree of coupling between the spatial distribution of population and economy in the region. The closer its value is to 1, the better the degree of coupling between population and economy, and the more coordinated the development of population and economy. Conversely, it indicates that the degree of coupling between population and economy is worse, and the development of population and economy is less coordinated. Its mathematical expression formula is [37,38,39]

where n represents the number of county-level administrative units, pi and ui represent the population agglomeration level and economic agglomeration level of the ith unit, respectively, and Pi and Ui represent the population and GDP of the ith region, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial–Temporal Characteristics of Population

3.1.1. Spatial Distribution Pattern of Population Density

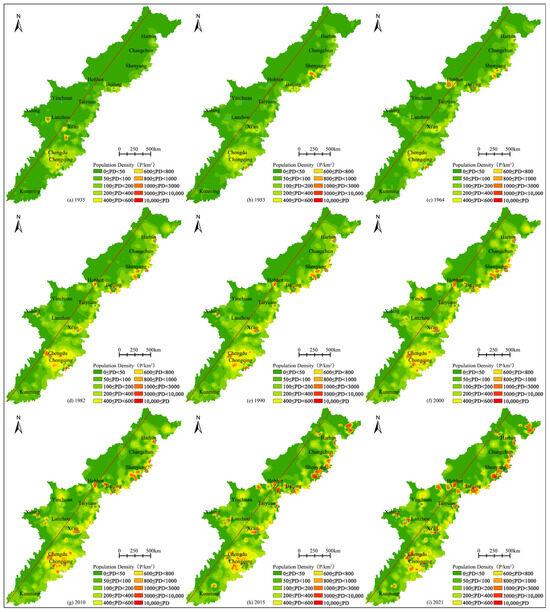

Using inverse distance weighted (IDW) spatial interpolation, the population density values for each county and city within the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” were visualized, resulting in a series of population density classification maps (Figure 2) spanning from 1935 to 2020. These maps reveal a strikingly uneven population distribution within the region. Specifically, the population density on the southeast side of the Hu Huanyong Line is significantly higher than on the northwest side, with dense populations primarily clustered around provincial capital-centered urban agglomerations, forming distinct population concentration zones in certain areas. Population density is categorized into three classes: high-density areas (≥400 people/km2), medium-density areas (200–400 people/km2), and low-density areas (<200 people/km2).

Figure 2.

(a–i) Spatial–temporal evolution characteristics of population distribution in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” from 1935 to 2020.

Between 1935 and 1953, high-density population zones were concentrated in the Chengdu–Chongqing urban agglomeration, Lanxi urban agglomeration, Guanzhong Plain, Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei urban agglomeration, and the northwest portion of the Liaozhongnan urban agglomeration. The Chengdu–Chongqing region, a vital urban belt in western China, serves as a strategic link connecting east and west, and north and south. Similarly, the Lanxi urban agglomeration, with its natural resource wealth, scientific strengths, and favorable agricultural conditions, has high population density. The Guanzhong Plain, steeped in historical significance as the cradle of Chinese civilization and a Silk Road starting point, holds a crucial strategic role in China’s modernization and international engagement. The Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, often referred to as the “Capital Economic Circle”, and the Liaozhongnan urban agglomeration, an industrial hub and critical gateway for northeastern China’s opening up, further exemplify regions of high population density, supported by their economic development, strategic locations, and policy advantages.

Medium-density areas during this period were distributed across regions such as the Jinzhong urban agglomeration centered on Taiyuan and the Songnen Plain in northeastern China, characterized by favorable topographies such as plains and hills, robust agricultural resources, and moderate population densities. Conversely, low-density areas included the Central Yunnan urban agglomeration, the Ningxia Yellow River urban agglomeration, the Hohhot–Baotou–Ordos–Yinchuan urban cluster, and regions like the Greater and Lesser Xing’an Mountains, Inner Mongolia, and the Sanjiang Plain. These regions face challenges such as complex terrain, harsh climates, underdeveloped economies, and fragile ecological environments, resulting in significant population outflows and low densities.

Between 1953 and 2010, shifts in population density occurred as the Jinzhong urban agglomeration and Songnen Plain transitioned from medium- to high-density areas, while Hohhot shifted from low to high density. The Ningxia Yellow River urban agglomeration, Central Yunnan urban agglomeration, and Sanjiang Plain advanced from low- to medium-density areas during the same period. By 2015, these regions had further transformed into high-density population zones, reflecting dynamic shifts in population distribution driven by improved economic conditions, policy support, and infrastructural development.

From the perspective of spatial changes, from 1935 to 2020, the overall population density of the “Mid-Spine Belt” showed an increasing trend. With the acceleration of industrialization, urbanization, modernization, and the reform of the registered residence system, the level of economic development between regions has become increasingly unbalanced. The differences in population density changes among different areas are significant, and the population distribution tends to be dispersed. The range of high-value and medium-value areas of population density in various urban agglomerations and regions has gradually expanded, while the range of low-value areas of population density has decreased. This is especially evident on the southeast side of the Hu Huanyong line after 1982. This is due to the fact that after the reform and opening up, the economic center of gravity moved southeastward, attracting a large number of people, which led to a rapid growth of population in the urban agglomerations on the southeast side.

3.1.2. Spatial Aggregation Characteristics and Evolutionary Trends of Population Distribution

The overall autocorrelation characteristics of population distribution in various counties and cities were revealed using the Global Moran’s I index. The global autocorrelation index of population density distribution at the county level in the “Mid-Spine Belt” from 1935 to 2020 was calculated using GeoDa 1.20.0.36 software (Table 1).

Table 1.

Global autocorrelation index of population density in the “mid-spine belt” from 1935 to 2020.

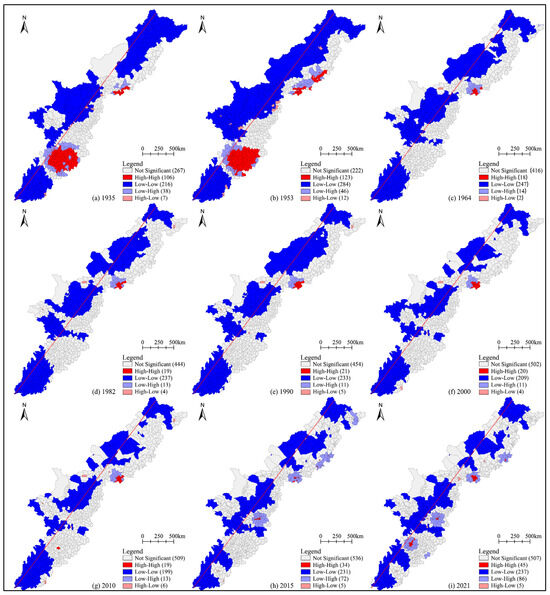

From 1935 to 2020, most of the county-level units in the “Mid-Spine Belt” fell into the first and third quadrants. The number of scatter points in the third quadrant was much higher than that in the first quadrant, and they were mostly around the slope line, indicating a positive spatial correlation in the population density distribution of the “Mid-Spine Belt”. There were a few scatter points in the second and fourth quadrants, where the population density of the county-level units differed significantly from other counties. As time went on, the scatter points showed a trend of spreading outwards, indicating that the differences in population agglomeration characteristics among counties were continuously increasing.

At a 5% significance level, the population density distribution of the “Mid-Spine Belt” has always exhibited characteristics of spatial agglomeration (Table 1). From 1935 to 1953, the Global Moran’s I index rose from 0.153 to 0.256, indicating a temporary increase in population agglomeration. In 1964, it decreased to 0.116, indicating a trend towards population dispersion. From 1964 to 2000, it continued to rise from 0.116 to 0.162, with areas where the population density of counties and cities was similar, aggregating spatially, and the differences in spatial development became increasingly significant. From 2000 to 2020, it continued to decline from 0.162 to 0.111, weakening the trend of spatial convergence in population density and reducing the differences in spatial development. In summary, the population density distribution in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” exhibits positive spatial correlation, and the population density distribution of counties and cities is not independent in space, meaning that areas with low population density are adjacent to each other, and areas with high population density are also adjacent to each other.

In the entire “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China”, the main types of population agglomeration are HH agglomeration and LL agglomeration (Figure 3). HH agglomeration indicates contiguous areas with a growing trend in population density. This was most significant in 1935 and 1953, and mainly distributed in the Chengdu–Chongqing urban agglomeration, the northwest of the Liaozhongnan urban agglomeration, and Beijing. These areas are all characterized by high population density and relatively high levels of economic development, attracting a large number of people to migrate in due to economic advantages and driving the development of surrounding areas, resulting in high population density in these areas. After 1953, the Chengdu–Chongqing urban agglomeration shifted from HH agglomeration to a non-significant area. LL agglomeration indicates contiguous areas with low population density, mainly concentrated on the west side of the Hu Huanyong Line, as well as Yunnan Province and northern Heilongjiang (including the Greater and Lesser Xing’an Mountains and the Sanjiang Plain, which became a non-significant area from LL agglomeration after 1964). These areas have a relatively low level of socioeconomic development and a relatively complex natural geographical environment, showing a clear low-density population agglomeration, and their coverage areas have gradually shrunk overall. Before 1964, LH agglomeration was mainly distributed in the Chengdu–Chongqing urban agglomeration and the surrounding areas of Beijing; after 1964, the LH agglomeration in the Chengdu–Chongqing region became a non-significant area, and LH basically only existed around Beijing; after 2015, LH agglomeration reappeared in some local areas such as the Guanzhong region, the Liaozhongnan urban agglomeration, and the surrounding areas of Chengdu. HL agglomeration is only distributed in small quantities around and within the HH and LL agglomeration areas, with strong randomness and obvious spatial heterogeneity.

Figure 3.

(a–i) Spatial–temporal evolution characteristics of the agglomeration distribution in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” from 1935 to 2020.

3.2. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of the Economy

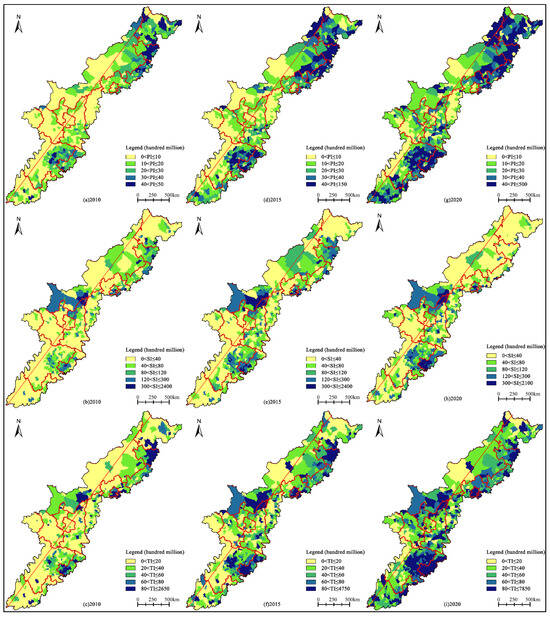

3.2.1. Spatial Distribution Pattern of Socio-Economic Factors

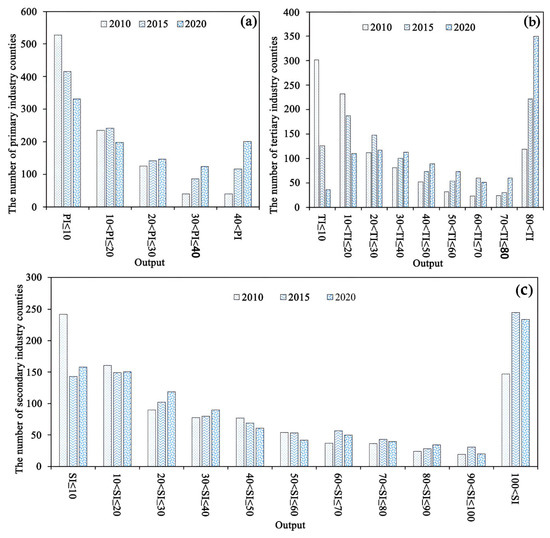

In the past decade, the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” have developed rapidly, especially the primary and tertiary industries; the three major industries have shown significant imbalances in time and space scales. At the same time, combined with the temporal and spatial differences of industries, it can be inferred that there is also significant spatial heterogeneity in the socioeconomic resources of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Changes in the number of counties in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” by socioeconomic level from 2010 to 2020: (a) the number of primary-industry counties; (b) the number of tertiary-industry counties; (c) the number of secondary-industry counties.

Figure 5.

Spatial–temporal distribution and evolution characteristics of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” from 2010 to 2020: (a,d,g) are the output values of the primary industry for three years; (b,e,h) are the output values of the secondary industry for three years; (c,f,i) are the output values of the tertiary industry for three years.

From 2010 to 2020, the proportion of counties with low-level primary industry output value in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” was relatively large, and the proportion of high-level counties increased to a certain extent. Among them, the proportion of counties with PI ≤ CNY 1 billion decreased from 54.4% to 33.1%, the proportion of counties with CNY 1 billion < PI ≤ CNY 2 billion decreased from 24.3% to 19.8%, the proportion of counties with CNY 2 billion < PI ≤ CNY 3 billion increased from 13.0% to 14.6%, the proportion of counties with CNY 3 billion < PI ≤ CNY 4 billion increased from 4.1% to 12.4%, and the proportion of counties with PI > CNY 4 billion increased from 4.1% to 20% (Figure 4). Spatially, the counties with the largest output value in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” from 2010 to 2020 were Qiqihar City (CNY 15.8 billion), Shuangcheng County (CNY 14 billion), and Ningjiang County (CNY 22 billion). At the same time, there were significant regional differences. The primary industry in the eastern region and the southwestern Sichuan Basin and Yunnan–Guizhou region developed rapidly, while the central region developed relatively slowly, especially in the northern region affected by natural conditions along the “Hu Line” (Figure 5).

From 2010 to 2020, the regions with a relatively rapid development rate of secondary industry output value in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” were mainly concentrated in the border areas of Inner Mongolia, including Ningxia, Gansu, and Shaanxi, the Sichuan Basin, areas along the Yellow River, and typical large cities (such as Xi’an, Beijing, Chongqing, Chengdu, Harbin, etc.) and their surrounding areas. The overall development in the northeast region showed a downward trend (Figure 5). Combining the overall situation of each county, it can be seen that the secondary industry in the “Beautiful China Mid-Spine Belt” has shown a trend of “growth decline” in the past 10 years. It was especially affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, when the overall economy was in a state of decline and stagnation. At the same time, the proportion of counties with an SI of less than CNY 5 billion increased by nearly 10%, among which the proportion of counties with an SI of less than CNY 10 billion was 8.2%, showing a more obvious increase; the proportion of counties with an SI of less than CNY 1 billion decreased from 25% in 2010 to 15.8% in 2020, and the proportion of counties at other levels of development did not change significantly overall (Figure 4). Therefore, the secondary industry in some areas of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” developed rapidly, and regional differences further increased.

Among the three major industries, the tertiary industry developed the fastest in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” from 2010 to 2020, especially in counties with a total investment (TI) of less than CNY 8 billion, which increased significantly with a growth rate of 22.7%. At the same time, the number of counties with a TI of less than CNY 1 billion decreased by 27.6%, the number of counties with a TI of CNY 1 billion to CNY 2 billion decreased by 12%, and the number of other development levels increased steadily. From the perspective of spatial distribution, the regions with rapid development are mainly distributed in the border areas of Shaanxi–Inner Mongolia–Ningxia, the Sichuan Basin, and the southern side of the “Hu Huanyong Line” in Northeast China, especially along the eastern boundary of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China”. At the same time, in the past 10 years, the most prominent regions for the development of the tertiary industry have been Chaoyang County and Haidian County in Beijing, with the functions of the capital city being adjusted.

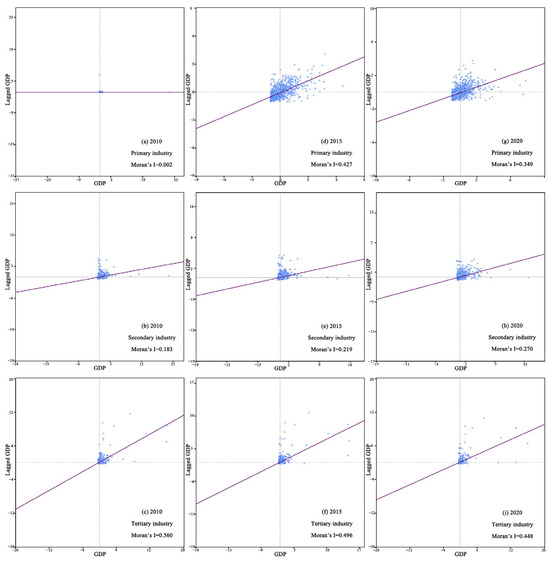

3.2.2. Characteristics and Evolutionary Trends of Socioeconomic Spatial Agglomeration

From 2010 to 2020, the spatial agglomeration degree of socioeconomic indicators in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” at the global scale was not high; it was relatively dispersed and there were significant spatiotemporal differences (Figure 6). In terms of the size of the global agglomeration index, the trend was as follows: I secondary industry < I primary industry < I tertiary industry; in terms of the magnitude of changes in the global agglomeration index, the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” showed the largest change in I primary industry, followed by I tertiary industry and I secondary industry. From 2010 to 2020, the slope of the trend line of primary industry agglomeration degree showed an increasing–decreasing trend; the trend line of secondary industry agglomeration degree showed a parallel state; and the slope of the trend line of tertiary industry agglomeration degree showed a continuously weak downward trend. The overall change in secondary and tertiary industries was not obvious.

Figure 6.

Spatial–temporal evolution characteristics of socio-economic indicators in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” at the global scale from 2010 to 2020: (a,d,g) are the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of the primary industry at the global scale from 2010 to 2020; (b,e,h) are the spatial–temporal evolution characteristics of the secondary industry at the global scale from 2010 to 2020; (c,f,i) are the output values of the tertiary industry at the global scale from 2010 to 2020.

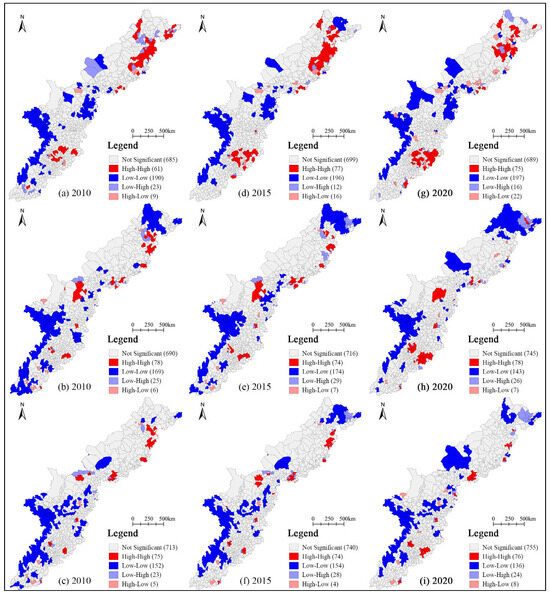

From 2010 to 2020, the spatial aggregation characteristics of socioeconomic indicators on a local scale in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” exhibited significant heterogeneity (Figure 7). The overall development of the primary industry was relatively dispersed, with high agglomeration levels in the Northeast China urban agglomeration and the Sichuan Basin urban agglomeration, while low-agglomeration areas were mainly concentrated in the marginal areas of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau (i.e., the northern part of the southwest section of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China”) and Shanxi Province. The areas with high agglomeration levels of secondary and tertiary industries were relatively few and scattered, while the low-agglomeration areas were mainly located in the marginal areas of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and the border areas between Northeast China and Russia.

Figure 7.

Spatial–temporal evolution characteristics of socio-economic indicators in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” at the local scale from 2010 to 2020: (a,d,g) are the spatial–temporal evolution characteristics of the primary industry at the local scale from 2010 to 2020; (b,e,h) are the spatial–temporal evolution characteristics of the secondary industry at the local scale from 2010 to 2020; (c,f,i) are the output values of the tertiary industry at the local scale from 2010 to 2020.

3.3. Spatial–Temporal Coupling of Population Distribution and Social Economy

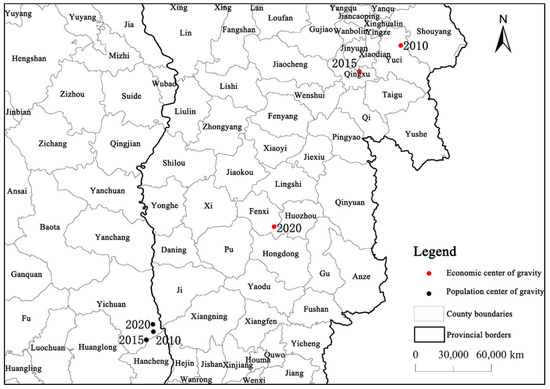

3.3.1. Spatial–Temporal Evolution Characteristics of Population and Economic Gravity Center

The migration direction of population and economy clearly reflects the dynamic changes and equilibrium of population distribution and economy, and their equilibrium determines the correlation between population distribution and economy. According to the calculation method of population distribution and socio-economic center of gravity, the spatial coordinates of the population and economic center of gravity of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” from 2010 to 2020 were calculated, and a population and economic center of gravity map (Figure 8) was obtained, revealing the spatiotemporal evolution and connection between population distribution and economy in the Yangtze River Delta.

Figure 8.

Population and economic center of gravity map of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” from 2010 to 2020.

From a spatial distribution perspective, the population and economic centers of gravity are roughly located in the middle of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China”. The population center of gravity is located to the southwest of the geometric center (X = 533,925, Y = 4,136,136), while the economic center of gravity is located to the southeast of the geometric center. Both centers consistently deviate from the geometric center, indicating that the population and economic distribution in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” are not balanced. From 2010 to 2020, the population center of gravity in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” consistently moved within Yichuan County, with no significant changes in the spatial distribution pattern of the population (Figure 8). In contrast, the changes in the economic center of gravity were more pronounced. From 2010 to 2020, the economic center of gravity consistently migrated southwestward, with the migration distance increasing year by year. The population center of gravity was always located to the southwest of the economic center of gravity, and the distance between the two centers decreased year by year. From 2010 to 2020, the degree of spatial deviation between the population and economic center of gravity in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” showed a weakening trend, with improved balance and increased coupling, reflecting to some extent that the evolution of population and economy mutually promote each other.

3.3.2. Analysis of the Coordination Between Population and Economy

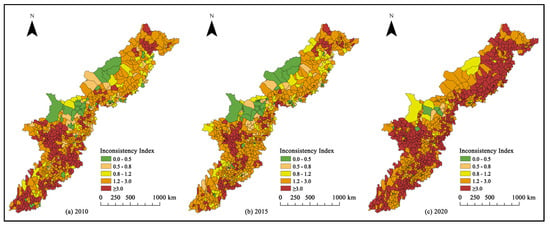

Based on the population and economic inconsistency index (C), the degree of economic consistency in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” was evaluated and analyzed. When the C value is greater than 1, the population agglomeration is higher than the economic concentration of the region; when the C value is less than 1, the population agglomeration is lower than the economic concentration of the region; when the C value is equal to 1, it indicates that the population agglomeration is consistent with the level of economic agglomeration. According to the classification standard of consistency, the population distribution and socioeconomic inconsistency index of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” are divided into five categories (Table 2), and spatial visualization processing is carried out to obtain the distribution map of inconsistency types (Figure 9).

Table 2.

Classification standards for the inconsistency index of population and economy in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China”.

Figure 9.

Distribution of population and economic inconsistency types in the Yangtze River Delta from 2010 to 2020.

The consistency between the economic level and population in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” shows significant regional differences (Figure 9). In 2010, the overall inconsistency index was higher on the right side of the Hu Huanyong Line, and the inconsistency index was also higher on both sides of the lower and middle sections of the Hu Huanyong Line, that is, on the eastern side of the Middle Ridge Zone. For example, the Chengdu–Chongqing urban agglomeration had a higher inconsistency index due to its large population, while the northeastern and central–western parts of Yunnan had higher inconsistency indices due to their lower economic levels. The inconsistency index in the Middle Ridge Zone was lower, mainly in eastern Inner Mongolia, northern Shanxi Province, and Ningxia, where the economic level was low and the population was small, resulting in a lower inconsistency index. In 2015, the inconsistency index in the northeastern and southwestern parts of the “Middle Ridge Zone” decreased slightly, but not significantly. For example, the southernmost part of the Middle Ridge Zone saw a decrease in the ratio of population to economic development due to economic growth, resulting in a lower inconsistency index. In 2020, the overall inconsistency index between population and economy in the “Middle Ridge Zone” increased, especially in the northeastern and southwestern parts of the Middle Ridge Zone. The inconsistency index also increased due to the rapid development of economy and urbanization in Liaoning, Jilin, the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei urban agglomeration, and the Chengdu–Chongqing urban agglomeration, and a large influx of population, leading to an increase in the ratio of population to economy and thus a higher inconsistency index. At this time, only a small part of the central and western parts of Inner Mongolia, northern Shaanxi Province, and eastern Inner Mongolia had an inconsistency index close to 1, indicating that the degree of population growth was consistent with the level of economic agglomeration.

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial Division of the Beautiful China Mid-Ridge Zone Based on Spatial Clustering

Based on the analysis of the overall population distribution, socio-economic factors, and their spatiotemporal correlations in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China”, this article divides the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” into three parts: east, central, and west, with six regions (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Spatial division of “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” based on spatial clustering.

4.1.1. Analysis of the Characteristics of the Eastern Section

The northern region of the eastern section: The area is located in the northern part of the Xing’an Mountains, mainly involving the Hulunbuir grassland, parts of the Heilongjiang River Basin, and the Songhua River Basin. The consistency of population and economic agglomeration is relatively low. The population density is relatively low compared to the southern region of the eastern section, and the spatial agglomeration type of population mostly presents as LL agglomeration. The agglomeration degree of the primary industry is relatively high, while the agglomeration degree of the secondary and tertiary industries is relatively low. The overall output value is low, and the socioeconomic agglomeration type is mostly insignificant. The surrounding areas north of Hulunbuir and some border areas between Northeast China and Russia present LL agglomeration in terms of socioeconomic agglomeration type. The main sources of socioeconomic development are import and export trade, aquaculture, and planting.

The southern region of the eastern section: Located in the southern part of the Xing’an Mountains, it belongs to the Songhua River and Liaohe River basins, and is a mountainous and plain area in the southern part of the Xing’an Mountains. This area is an old industrial base in Northeast China and a part of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. The degree of population and economic agglomeration is highly inconsistent. The population density is relatively high, and the type of population agglomeration is mostly insignificant. The population agglomeration type in Beijing and its surrounding areas presents as HH agglomeration, while some areas in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region present as LH agglomeration. The development foundation of the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries is good, and the overall social output value is high.

4.1.2. Analysis of the Characteristics of the Middle Section

The northern region of the middle section: The area is located in the northern part of the Qinling Mountains and the western part of the Taihang Mountains, belonging to the Loess Plateau region, the southern mountainous area, and the middle reaches of the Yellow River Basin. The terrain is rugged, with scattered small plains, and it belongs to the Yinchuan–Xi’an–Taiyuan–Hohhot urban agglomeration. The overall population and economic agglomeration in the region show diversity.

The southern region of the middle section: Located in the southern part of the Qinling Mountains, involving parts of the Sichuan Basin, the main terrain is mountainous, with intermountain plains and significant topographic relief. It belongs to the Chengdu–Chongqing urban circle. The degree of population and economic agglomeration is highly inconsistent. The population density is relatively high, and the overall population agglomeration type is not significant. The population agglomeration type in the Chengdu area presents as HH agglomeration. As the distance from Chengdu increases, the population in the surrounding areas gradually decreases, and the agglomeration type presents as LH agglomeration. The level of socioeconomic development is relatively good, and areas with a high degree of agglomeration are mostly located in the Chengdu and Chongqing urban circles. The planting industry is mainly rice and winter wheat, and the development of the three major industries is relatively balanced.

4.1.3. Analysis of the Characteristics of the Western Section

The northern region of the western section: Located at the eastern foothills of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, the terrain involves two major terraces in China, with significant topographic relief. There are scattered small plains in the east, belonging to the Xining–Lanzhou urban agglomeration. The degree of population and economic agglomeration is highly inconsistent. The overall population density is relatively low. In Xining, Lanzhou, and their surrounding areas, due to the relatively developed local economy, there are high-density population areas and relatively low levels of socioeconomic development. The overall agglomeration type is LL agglomeration. Agriculture is mainly based on animal husbandry and planting, with planting mainly focusing on miscellaneous grains. There are significant differences in the development space of the three major industries.

The southern region of the western section: Located in the southeastern part of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, the main terrain is part of the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau, with significant topographic relief. The region mainly comprises the Kunming urban agglomeration, with a high degree of inconsistency between population and economic agglomeration. The population density is low, and the population agglomeration characteristics obviously tend towards LL agglomeration. The economic development is relatively backward, and there are large spatial and temporal differences in social and economic development in the region, with uneven development. The tertiary industry (such as tourism) is relatively good, and the planting industry is mainly based on corn and rice in mountain terraces.

4.2. Population Distribution and Social and Economic Development Trends in the Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China

From a demographic perspective, since 1935, the population density of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” has been continuously increasing. However, the growth rate gradually slowed down from 1982 to 2020. In addition, scattered high-density areas first appeared in large urban areas, followed by the gradual emergence of medium-density areas around the high-density areas and their continuous expansion. Subsequently, some high-density areas formed within the medium-density areas. From 1935 to 2020, the characteristics of population agglomeration reflected the large regional differences in population distribution in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China”, and the regional differences in population distribution characteristics increased year by year, but the overall distribution of agglomeration types remained relatively stable. Therefore, in the future, while the population density of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” continues to rise, the growth rate will still maintain a slowdown trend. At the same time, due to the influence of natural geographical conditions and socio-economic industrial structure, the northwest direction of the Beijing urban circle, the southwest direction of the Xining–Lanzhou urban circle, and the northern part of the southwest section of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China”, bounded by the “Hu Huanyong Line”, will continue to exhibit low-density areas. The overall agglomeration characteristics of population distribution in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” will still exhibit diversity, and under the further strengthening of regional differences in population agglomeration characteristics, the overall characteristic distribution will not change significantly. For example, some areas around the “Hu Huanyong Line” will still exhibit LL agglomeration types due to their topography and industrial structure, while HH and HL agglomeration types will appear in large cities and their surrounding areas.

From an economic perspective, the output value of the primary and tertiary industries in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” has shown a continuous upward trend from 2010 to 2020. The output value of the secondary industry increased from 2010 to 2015, but decreased from 2015 to 2020 due to changes in regional functions and industrial restructuring. Overall, it shows a characteristic of first increasing and then decreasing. The spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of socioeconomic indicators in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” from 2010 to 2020 visually demonstrate the agglomeration characteristics of the three major industries, facilitating the analysis of regional characteristics and their advantages. The development of the three major industries in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” is fragmented, with significant regional development differences. Combined with a comprehensive analysis of the development of the three major industries, it is found that most regions have pillar industries. The areas surrounding the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau are not conducive to the development of the three major industries due to their rugged terrain. The agglomeration characteristics of the three major industries in the southwest direction of the Xining–Lanzhou urban circle and the northern part of the southwest section bounded by the “Hu Huanyong Line” have always shown LL agglomeration types. Therefore, it is comprehensively predicted that the output value of the primary and tertiary industries in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” will continue to increase in the future, but due to issues such as environmental carrying capacity, the growth rate will slow down. Due to the sustainable development strategy, the output value of the secondary industry will further decrease due to its scale reduction. Overall, the agglomeration of the three major industries will still show non-agglomeration characteristics in most regions due to significant regional industrial development differences. Due to the radiation effect of large cities on their surrounding areas, the agglomeration of the tertiary industry will form HH agglomeration characteristics in large cities while expanding outward, gradually forming HL agglomeration characteristics with surrounding areas. At the same time, due to significant natural geographical differences in the region, the development of the three major industries is greatly restricted. The agglomeration of the three major industries in some regions will show LL agglomeration types for a considerable period of time, and the differences in agglomeration caused by regional differences will further increase.

Since 2010, the population center of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” has been located in Yichuan County for a long time, and the population distribution has been relatively stable. However, the economic center of gravity has shifted from Yuci County to Fenxi County since 2010, which has resulted in significant changes. This is due to the stable population distribution and the structural adjustment of the three major industries made by various regions to cater to the quantity and quality of local labor force, which caused the economic center of gravity to migrate from Yuci County to Fenxi County in the southwest [40,41,42,43]. The coupling degree between the economic center of gravity and the population center has deepened. The consistency characteristics of population and economy macroscopically reflect that the coordination of population and economy in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” needs to be improved. In recent years, the environmental carrying capacity of the population in large cities in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” has been severely challenged, and its attraction to external populations has also led to overpopulation in surrounding areas. Therefore, the coupling degree between the economic center of gravity and the population center of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” will continue to deepen. At the same time, due to the increasing spatial heterogeneity of economic development, the coordinated development of population and economy is an urgent problem to be solved for the sustainable development of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China”. Therefore, small- and medium-sized cities and towns should focus more on regional characteristic economic development, loose population attraction policies, and social infrastructure construction to improve the quality of regional human settlement environment.

5. Conclusions

This study uses population density and the three major industries in China as its main indicators, using nine periods of population data from 1935 to 2020 and three periods of data on the three major industries from 2010 to 2020 as data sources. Spatial interpolation, centroid migration, spatial autocorrelation, and the inconsistency index are used to reveal the laws and evolution characteristics of the spatial distribution of population and economy in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China”. The conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- On both sides of the “Hu Line”, there is a significant spatial variation in population distribution. The population is mainly distributed on the eastern edge of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” and in the Sichuan Basin. Over time, the population growth rate has become significantly higher in the Hexi Corridor, Hetao Plain, and major urban agglomerations.

- (2)

- At the global scale, the population distribution of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” does not show significant aggregation characteristics, but rather exhibits notable spatial heterogeneity. The years with relatively obvious population distribution agglomeration are mainly 1953 and 2000, due to the rapid increase in population in the early days of the founding of the People’s Republic of China and the national western development strategy. At the local scale, the population distribution of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” from 1935 to 2020 can be divided into three parts: the northeast region, the central region (Xi’an–Lanzhou–Hohhot–Gansu), and the southwest region (Sichuan Basin, south of the Qinling Mountains).

- (3)

- On a global scale, there were significant spatial agglomeration differences in socioeconomic indicators in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” from 2010 to 2020. Second industry < first industry < tertiary industry. The first industry had the largest change, while the changes in the second and tertiary industries were relatively less significant. On a local scale, the spatial agglomeration of socioeconomic indicators in the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China” from 2010 to 2020 showed significant heterogeneity. The regions with high agglomeration of the primary industry were located in the Northeast urban agglomeration and the Sichuan Basin urban agglomeration; the regions with high agglomeration of the secondary and tertiary industries were relatively few and scattered; and the regions with low agglomeration of the three industries were mainly located in the northern part of the southwest section of the “Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China”.

- (4)

- From 2010 to 2020, the changes in the economic center of gravity of the “Beautiful China Mid-Spine Belt” were more pronounced compared to the population center of gravity. The migration distance of the economic center of gravity increased year by year, and the distance between the two decreased year by year. At the same time, the deviation between the population and economic centers of gravity in space showed a weakening trend, with improved balance and increased coupling.

Based on the degree of imbalance and agglomeration characteristics of population and economic development, decision-making and management departments can develop precise strategies for the integrated planning and coordinated layout of both elements on spatial and temporal scales. At the micro level, for situations where the population is concentrated in urban centers while the surrounding rural areas have sparse populations and underdeveloped economies, a reasonable layout of industries and infrastructure can be adopted to guide the rational distribution of population and economic activities. At the macro level, for regions with large differences in economic development levels, such as the eastern coastal areas and the central and western regions, national-level regional coordinated development strategies should be formulated. Through policy preferences and resource allocation, the investment environment in less developed areas can be improved to attract industries and population, thereby reducing the degree of regional imbalance. For regions with significant differences in spatial agglomeration, decision-making and management departments can formulate regional coordinated development strategies, such as formulating cross-regional economic cooperation plans and implementing targeted support policies for developed and underdeveloped areas. This will help narrow the wealth gap caused by spatial agglomeration effects.

This study comprehensively analyzes population, economic development, and their clustering characteristics in the “Beautiful China Middle Ridge Belt” through the equilibrium analysis of population distribution and social economy, spatial cluster analysis, and the coupling analysis of population distribution and economic development, and excavates the coupling trend of population and economy, which intuitively reflects the potential population and economic coordination problems in each region of the study area. The practical use of the study is described in the corresponding context.

However, the above insights are based on a macro analysis of output value and population, which can be affected by a variety of factors. Follow-up research can further analyze the influencing factors of local GDP changes and population changes according to the policies, zoning, and customs of each region, so as to make more refined predictions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Y.; methodology, Q.Y.; validation, J.Y.; formal analysis, Q.Y. and J.Y.; investigation, J.Y.; data curation, W.C. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Y. and J.Y.; writing—review and editing, Q.Y., J.Y., Y.L., and W.C.; supervision, Y.L. and S.J.; funding acquisition, Q.Y. and Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, S.; Wang, Z. Studies on Spatial Consistency between Population Agglomeration and Economic Agglomeration in China. Popul. J. 2017, 39, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Q. Simulating spatial distribution and varying patterns of population in Urumqi, China. In Proceedings of the MIPPR 2007: Remote Sensing and GIS Data Processing and Applications; and Innovative Multispectral Technology and Applications, Wuhan, China, 15–17 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, X.; Wu, J. Dynamics of Spatial Pattern between Population and Economies in Northeast China. Popul. J. 2018, 40, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Wang, C.; Liu, L. Spatio-temporal Change Analysis of Population and Economic Gravity Center Gravity Center Based on ArcGIS. Geospat. Inf. 2022, 20, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Fumitaka, F.; Wong, H. The Relationship between Population and Economic Growth in AsianEconomies. ASEAN Econ. Bull. 2005, 22, 314–330. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z. Study on the Space—time Coupling between Population and Economy Based on GIS. Geomat. Spat. Inf. Technol. 2019, 42, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H. Distribution of Chinese population—With statistical tables and density charts. Chin. J. Geogr. Sci. 1935, 2, 33–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Gou, H.; Luo, L.; Chang, R. From Hu Huanyong Line to Mid-Spine Belt of Beautiful China: Breakthrough in Scientific Cognition and Change in Development Mode. China Acad. J. 2021, 36, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollset, S.E.; Goren, E.; Yuan, C.-W.; Cao, J.; Smith, A.E.; Hsiao, T.; Bisignano, C.; Azhar, G.S.; Castro, E.; Chalek, J.; et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: A forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2020, 396, 1285–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D.E.; Chatterji, S.; Kowal, P.; Lloyd-Sherlock, P.; McKee, M.; Rechel, B.; Rosenberg, L.; Smith, J.P. Macroeconomic implications of population ageing and selected policy responses. Lancet 2015, 385, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim LaFrombois, M.E.; Park, Y.; Yurcaba, D. How U.S. Shrinking Cities Plan for Change: Comparing Population Projections and Planning Strategies in Depopulating U.S. Cities. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 43, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, J.P.; Brady, O.J.; Golding, N.; Kraemer, M.U.G.; Wint, G.R.W.; Ray, S.E.; Pigott, D.M.; Shearer, F.M.; Johnson, K.; Earl, L.; et al. The current and future global distribution and population at risk of dengue. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delazeri, L.M.M.; Da Cunha, D.A.; Vicerra, P.M.M.; Oliveira, L.R. Rural outmigration in Northeast Brazil: Evidence from shared socioeconomic pathways and climate change scenarios. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 91, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Liu, X. Multi-scale Studies on the Space Consistency between Population Distribution and Economic Development in China. Popul. Econ. 2013, 9, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gou, W.; An, X.; Wang, S. The Research on The Coordination Development of Population Distribution and Regional EconomyIN Shanxi Province. Econ. Geogr. 2004, 24, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Duan, X.; Tian, F.; Qin, X. Study on The Relationship Between Population and Economic Spatial Distribution in Yangtze River Delta. Econ. Geogr. 2009, 29, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Mu, G. The Mechanism of the Distribution Evolution of Floating Population and Urbanization—A Case Study of Zhejiang. Popul. J. 2016, 38, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Li, X. Relationship between population distribution and topography of the Wujiang River Watershed in Guizhou province. Geogr. Res. 2020, 39, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Zhu, B.; Liu, Y. Analysis on the Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Population Distribution and Its Influencing Factors in the Pearl River-Xijiang river Economic Belt. South China Popul. 2020, 35, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Peng, R.; Zhuo, Y.; Cao, G. China’s changing population distribution and influencing factors: Insights from the 2020 census data. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Feng, Z.; Lei, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, F. Regional Features and National Differences in Population Distribution in China’s Border Regions (2000–2015). Sustainability 2017, 9, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Chen, M.; Luo, X.; Xian, Y. Changes pattern in the population and economic gravity centers since the Reform and Opening up in China: The widening gaps between the South and North. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, V.V. Territorial Distribution of the Population in the Russian Federation. Econ. Reg. 2017, 13, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Inoue, N. The Future Process of Japan’s Population Aging: A Cluster Analysis Using Small Area Population Projection Data. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2024, 43, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, A.; Guido, Z.; Tuholske, C.; Pakalniskis, A.; Lopus, S.; Caylor, K.; Evans, T. Dynamics of population growth in secondary cities across southern Africa. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 35, 2501–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Yang, Y. Study on the evaluation of the coordinated development of population and economy—Taking Wuwei of Gansu Province as an example. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2010, 24, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; He, L. Spatiotemporal changes in population distribution and socioeconomic development in China from 1950 to 2010. Arab. J. Geosci. 2017, 10, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BI, Q. Spatial differences in the coupling of population structure and regional economy in Inner Mongolia. RrnCai ZiYuan KaiFa 2015, 4, 235–236. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; LI, Z. Evolvement characteristics of population and economic gravity centers in tarim river basin, uygur autonomous region of Xinjiang, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 23, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Huang, L.; Shen, B. Study on spatial interpolation method of monthly mean temperature in Shaanxi Province. J. Water Resour. Water Eng. 2017, 28, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Huang, W. Research on Evolution of Population and Economy Spatial Distribution Pattern in Ecologically Fragile Areas: A Case Study of Ningxia, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 814569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; He, L. Temporal-Spatial coupling analysis between population change trend and socioeconomic development in China from 1952 to 2010. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 20, 1424–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Lu, Y. Spatial distribution pattern of population and characteristics of its evolution in China during 1935–2010. Geogr. Res. 2016, 35, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, K. Research on the Spatial Pattern of Coupling Between Population Structure and Economic Development —A Case Study of Counties in Jiangsu Province. Popul. Decelopment 2018, 24, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Qiao, H. An empirical study on the spatial distribution of the population, economy and water resources in Northeast China. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2015, 79–82, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Xu, Y. Spatial Temporal Pattern and Influencing Factors of Population Distribution in Shandong Province. Anhui Agric. Sci. Bull. 2019, 25, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z. Spatial Effect of Population—Economic Distribution Consistency in China. Popul. Res. 2013, 37, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z.; Zhang, P. Simulation analysis on spatial pattern of urban population in Shenyang City, China in Late 20th century. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2011, 21, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Wahap, H. Spatio-temporal Evolution Analysis of Population Distribution and Economic Development Inconsistent in Xinjiang. Areal Res. Dev. 2016, 35, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Spatial—Temporal Evolution of Population and Economy in Beijing—Tianjin—Hebei Region. Econ. Probl. Explor. 2022, 11, 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Wang, H.; Dong, Y. Research on the Influencing Factors of Population Flow Decision in Northwest Region: Based on New Spatial Economics. Northwest Popul. J. 2022, 43, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Shan, L.; Yuan, Y.; Peng, F. Temporal-spatial pattern and its influence factors about population migration in three provinces of northeast China. J. Liaoning Norm. Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2019, 42, 391–402. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Xiang, G.; Peethambaran, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Hu, F. AFGL-Net: Attentive Fusion of Global and Local Deep Features for Building Façades Parsing. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).