Transforming Public Space with Nature-Based Solutions: Lessons from Participatory Regeneration in Lorca, Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

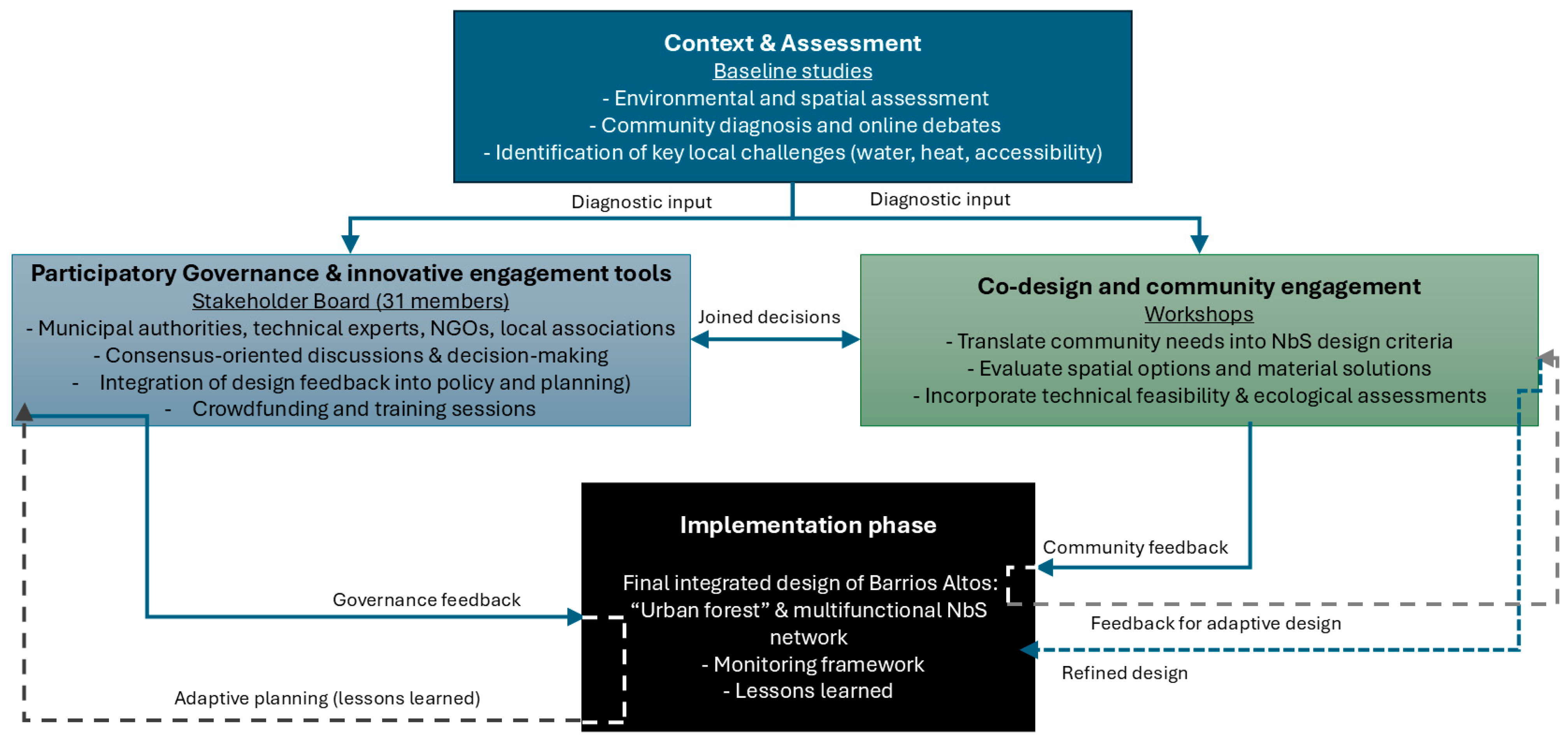

2. Materials and Methods

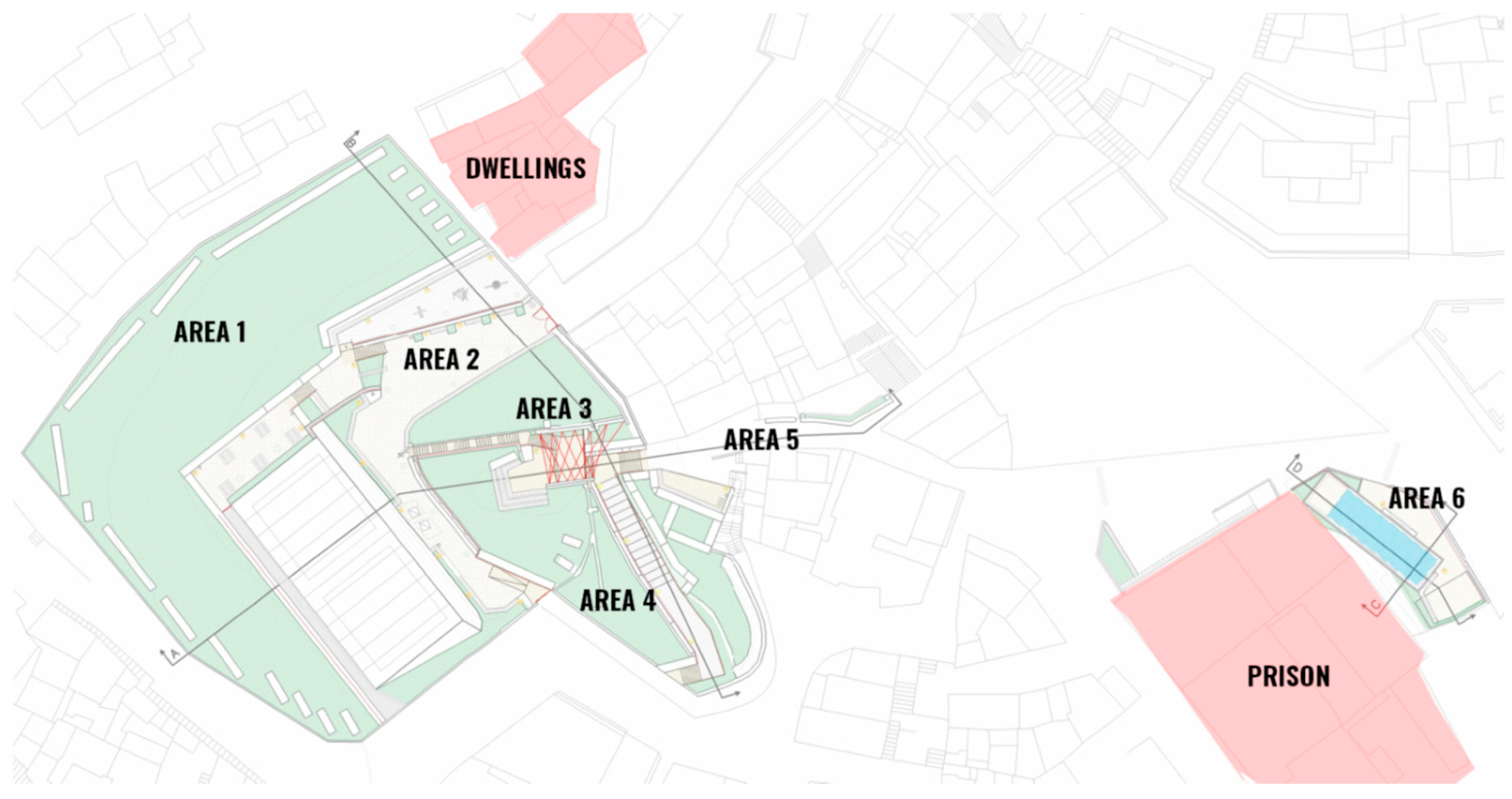

2.1. Study Area and Baseline Community Assessment

2.2. Participatory Governance and Stakeholder Mapping

2.3. Co-Design Workshops and Integration into NbS Design

2.4. Participatory Governance Plan and Innovative Tools

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

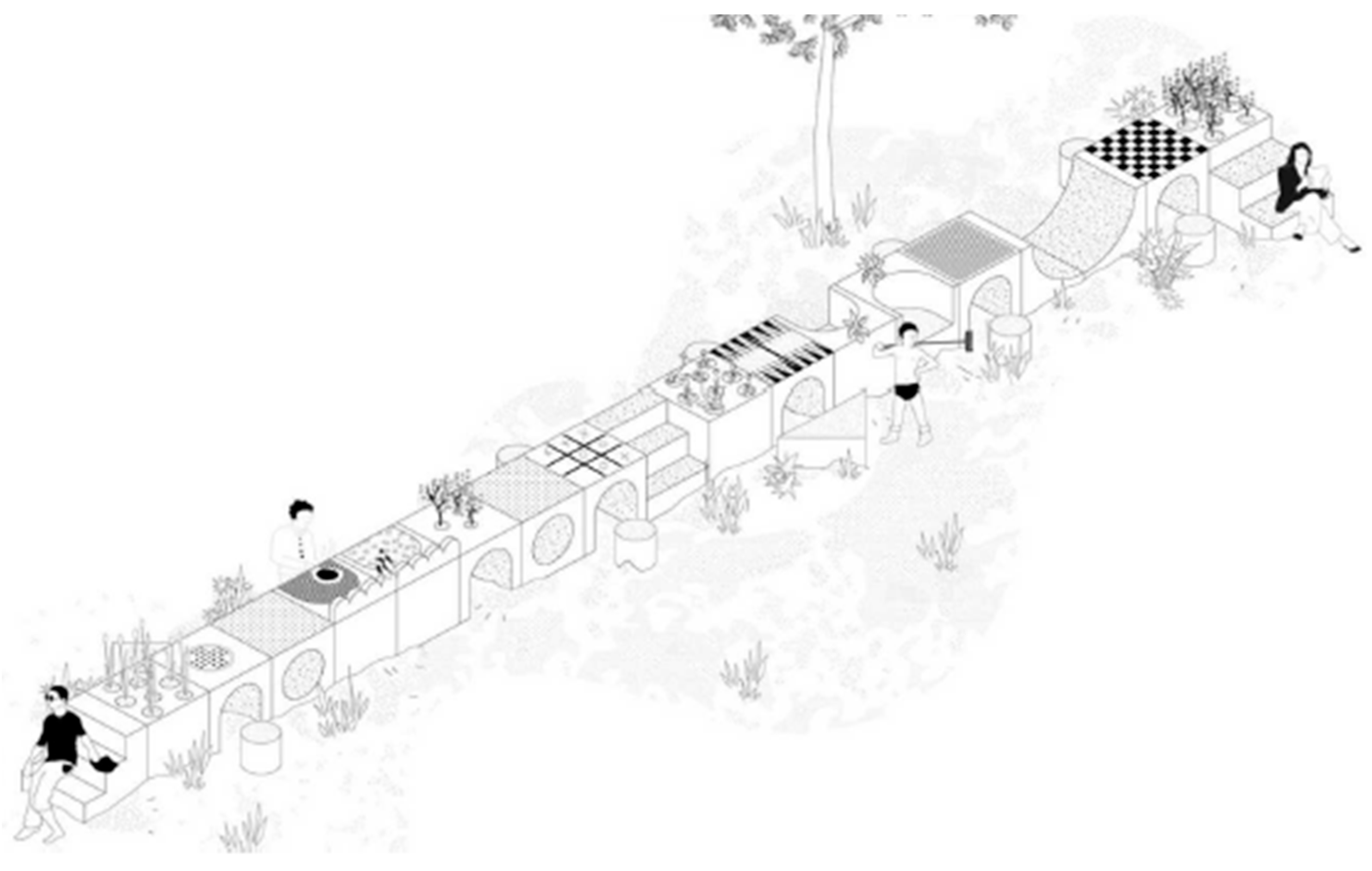

3.1. Co-Designed Interventions and Features

- Residents emphasized accessibility and safety, pointing to the steep slopes of San Pedro Street, accidents caused by limited mobility options, and dangerous traffic on the nearby highway, all underscoring the need for railings, ramps, and wheelchair access, including around the Church as a key community site.

- Green infrastructure was welcomed but with caveats: vegetation should be carefully selected to avoid allergies, provide shade, and remain accessible, while also incorporating spaces for physical activity.

- Participants—particularly women—stressed family and community needs, calling for shaded play areas, craft and educational workshops, and childcare provision to enable participation in cultural or recreational activities.

3.2. Participatory Governance and Community Engagement Outcomes

3.3. Challenges, Limitations and Lessons Learned

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EU | European Union |

| NatUR-W | Nature-based Urban Regeneration through Water |

| NbS | Nature-based Solutions |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

References

- Rogers, N.J.; Adams, V.M.; Byrne, J.A. Agenda-setting and policy leadership for municipal climate change adaptation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 161, 103869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo, S.; Amado, M.; Ferreira, F. Challenges and opportunities in the use of nature-based solutions for urban adaptation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankao, P.R.; Qin, H. Conceptualizing urban vulnerability to global climate and environmental change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K. Equity in Urban Climate Change Adaptation Planning: A Review of Research. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Hansen, R. Principles for urban nature-based solutions. Ambio 2022, 51, 1388–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, S.E.; Grimm, N.B. Nature-based approaches to managing climate change impacts in cities. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 375, 20190124. [Google Scholar]

- Herranz-Pascual, K.; Anchustegui, P.; Cantergiani, C.; Iraurgi, I. Tool Used to Assess Co-Benefits of Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Ecosystems for Human Wellbeing: Second Validation via Measurement Application. Land 2025, 14, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Moglia, M. Mainstreaming nature-based solutions in cities: A systematic literature review and a proposal for facilitating urban transitions. Land Use Policy 2023, 130, 106661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmierczak, A. From the first European Climate Risk Assessment to action in policy and practice. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34 (Suppl. 3), ckae144.357. [Google Scholar]

- Solecki, W.; Roberts, D.; Seto, K.C. Strategies to improve the impact of the IPCC Special Report on Climate Change and Cities. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2024, 14, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perini, K.; Calise, C.; Castellari, P.; Roccotiello, E. Microclimatic and environmental improvement in a Mediterranean city through the regeneration of an area with nature-based solutions: A case study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzan, M.V.; Geneletti, D.; Grace, M.; De Santis, L.; Tomaskinova, J.; Reddington, H.; Collier, M. Assessing nature-based solutions uptake in a Mediterranean climate: Insights from the case-study of Malta. Nat. Based Solut. 2022, 2, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciuto, L.; Licciardello, F.; Scavera, V.; Verde, D.; Giuffrida, E.R.; Cirelli, G.L. The role of nature-based solutions for the water flow management in a Mediterranean urban area. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 208, 107375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bona, S.; Silva-Afonso, A.; Gomes, R.; Matos, R.; Rodrigues, F. Nature-based solutions in urban areas: A European analysis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T. Mainstream nature-based solutions for urban climate resilience. BioScience 2022, 72, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Jagt, A.P.; Buijs, A.; Dobbs, C.; van Lierop, M.; Pauleit, S.; Randrup, T.B.; Wild, T. An action framework for the participatory assessment of nature-based solutions in cities. Ambio 2023, 52, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekpour, S.; Tawfik, S.; Chesterfield, C. Designing collaborative governance for nature-based solutions. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 62, 127177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, B.; Sekulova, F.; Hörschelmann, K.; Salk, C.F.; Takahashi, W.; Wamsler, C. Citizen participation in the governance of nature--based solutions. Environ. Policy Gov. 2022, 32, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.S.; Ferranti, E.; Ghermandi, A.; Pert, P. Nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1672694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N. Seven lessons for planning nature-based solutions in cities. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 93, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhearson, T.; Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N. Nature-based solutions for sustainable, resilient, and equitable cities. In Nature-Based Solutions for Cities; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; p. xviii-11. [Google Scholar]

- Puskás, N.; Abunnasr, Y.; Naalbandian, S. Assessing deeper levels of participation in nature-based solutions in urban landscapes—A literature review of real-world cases. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 210, 104065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnou, C.; Pino, J.; Davies, C.; Winkel, G.; De Vreese, R. Co-design processes to address nature-based solutions and ecosystem services demands: The long and winding road towards inclusive urban planning. Front. Sustain. Cities 2020, 2, 572556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, C. Reviving Barrios Altos: A New Vision for Lorca. European Urban Initiative—Portico 2025. Available online: https://portico.urban-initiative.eu/urban-stories/european-urban-initiative/reviving-barrios-altos-new-vision-lorca-6691 (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Wamsler, C.; Raggers, S. Principles for supporting city—Citizen commoning for climate adaptation: From adaptation governance to sustainable transformation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 85, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Graves, A.; Dandy, N.; Posthumus, H.; Hubacek, K.; Morris, J.; Prell, C.; Quinn, C.H.; Stringer, L.C. Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasin, N.; Kumar, S.; Singh, G.S. Participatory nature-driven urbanism: A pathway to achieving SDG-11 through community-led action. Urban Ecosyst. 2025, 28, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Slinger, J.; Vreugdenhil, H.; Van Daalen, E. Social-ecological systems governance: From paradigm to management approach. Nat. Cult. 2010, 5, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauleit, S.; Zölch, T.; Hansen, R.; Randrup, T.B.; van den Bosch, C.K. Nature-based solutions and climate change—Four shades of green. In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages between Science, Policy and Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sarzynski, A. Public participation, civic capacity, and climate change adaptation in cities. Urban Clim. 2015, 14, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Few, R.; Brown, K.; Tompkins, E.L. Public participation and climate change adaptation: Avoiding the illusion of inclusion. Clim. Policy 2007, 7, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Global Standard for Nature-Based Solutions: A User-Friendly Framework for the Verification, Design and Scaling up of NbS; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, V.N.; Price, A.; Austin, S.; Moobela, C. Defining, identifying and mapping stakeholders in the assessment of urban sustainability. In Proceedings of the SUE-MoT Conference 2007: International Conference on Whole Life Sustainability and Its Assessment, Glasgow, UK, 27–29 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Falleth, E.I.; Hanssen, G.S.; Saglie, I.L. Challenges to democracy in market-oriented urban planning in Norway. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llosa, C.D.L.; Reyes, E.M., Jr.; Agaton, C.B. Drivers of Successful Implementation of Nature-Based Solutions Initiatives: Challenges and Policy Recommendations. In Nature-Based Solutions for Urban and Peri-Urban Areas: For Resilient and Sustainable Urbanization; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 309–326. [Google Scholar]

- Olbertz, M.; Jafari, M.; Papina, C.; Abatzidi, A.; Tzortzi, J.N.; Mornar, N.; Timpe, A. The quadruple helix model in practice: Co-creating NBS requires novel governance approaches. Urban Transform. 2025, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munthe-Kaas, P. Agonism and co-design of urban spaces. Urban Res. Pract. 2015, 8, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Águas, S. Do Design ao Co-Design: Uma oportunidade de design participativo na transformação do espaço público. W@terfront 2012, 22, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Karrasch, L.; Klenke, T.; Woltjer, J. Linking the ecosystem services approach to social preferences and needs in integrated coastal land use management—A planning approach. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, I.; Ferreira, I.; Arlati, A.; Bradely, S.; Lupp, G.; Nunes, N. Towards a co-governance approach for nature-based solutions. In Guidelines for Co-Creation and Co-Governance of Nature-Based Solutions: Insights from EU-Funded Projects; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; pp. 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ataol, Ö.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Van Wesemael, P. Children’s participation in urban planning and design: A systematic review. Child. Youth Environ. 2019, 29, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozi, A.A.; Firoozi, A.A. Empowering Urban Resilience: Harnessing Crowdfunding for Sustainable Green Infrastructure. In Sustainable Financing—A Contemporary Guide for Green Finance, Crowdfunding and Digital Currencies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 177–199. [Google Scholar]

- Afzalan, N.; Muller, B. Online participatory technologies: Opportunities and challenges for enriching participatory planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2018, 84, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, C. NatUR-W New Urban Forest for Barrios Altos, Lorca: Insights over Design, Challenges and Opportunities. European Urban Initiative—Portico 2025b. Available online: https://portico.urban-initiative.eu/urban-stories/european-urban-initiative/natur-w-new-urban-forest-barrios-altos-lorca-insights-over-design-challenges-and-opportunities-7848 (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Raymond, C.; Breil, M.; Nita, M.; Kabisch, N.; de Bel, M.; Enzi, V.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Geneletti, G.; Lovinger, L.; Cardinaletti, M.; et al. An Impact Evaluation Framework to Support Planning and Evaluation of Nature-Based Solutions Projects. Report Prepared by the EKLIPSE Expert Working Group on Nature-based Solutions to Promote Climate Resilience in Urban Areas. 2017. Available online: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:3ecfc907-1971-473a-87f3-63d1204120f0 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Buijs, A.E.; Mattijssen, T.J.; Van der Jagt, A.P.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Andersson, E.; Elands, B.H.; Møller, M.S. Active citizenship for urban green infrastructure: Fostering the diversity and dynamics of citizen contributions through mosaic governance. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, I.H.; Morello, E.; Ludlow, D.; Salvia, G. Co-creation pathways to inform shared governance of urban living labs in practice: Lessons from three European projects. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 690458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, D.H. Co-creation in urban governance: From inclusion to innovation. Scand. J. Public Adm. 2018, 22, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. Barcelona Green Infrastructure and Biodiversity Plan 2020. 2013. Available online: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/ecologiaurbana/sites/default/files/Barcelona%20green%20infrastructure%20and%20biodiversity%20plan%202020.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Granberg, M.; Jernæs, N.K.; Martens, V.V.; Nielsen, V.K.S.; Haugen, A. Effects of climate-related adaptation and mitigation measures on Nordic cultural heritage. Heritage 2022, 5, 2210–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porębska, A.; Godyń, I.; Radzicki, K.; Nachlik, E.; Rizzi, P. Built heritage, sustainable development, and natural hazards: Flood protection and UNESCO world heritage site protection strategies in Krakow, Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Government Agencies and Authorities | Local, regional, and national bodies such as the city council, urban planning authorities, environmental agencies, and transportation departments. |

| Community and Residents | Individuals and families living within the area—directly affected by the project. |

| Environmental and Conservation Organizations | Local environmental groups, national conservation bodies, and international NGOs focused on ecological preservation |

| Local SMEs and Private Sector | Local businesses, developers, and real estate investors, contributing to or impacted by the project. |

| Experts and Academics | Researchers, scholars, and professionals with expertise in urban planning, environmental science, and sociology. |

| Educational Institutions and Teachers | Schools, universities, and teachers, engaged in education, awareness-raising, and knowledge transfer. |

| Funding Bodies and Financial Institutions | Banks, investment firms, grant agencies, and international economic organizations providing financial resources. |

| Media and Communication Channels | Newspapers, television, online platforms, and social media disseminating project-related information. |

| Regulatory and Compliance Bodies | National agencies (e.g., water authorities), ensuring adherence to laws, regulations, and standards. |

| General Public | Individuals and groups, indirectly affected by the project, including those outside the study area but interested in its outcomes. |

| Vulnerable Groups | Low-income households, elderly people, children and youth, persons with disabilities, immigrants, refugees, and minority groups. |

| Activity/Data Source | Purpose and Description | Participants/Data Details |

|---|---|---|

| Expert’s initial Survey (Spring 2022) | Gathered broader input by asking experts to identify issues related to key urban challenges. | 18 survey responses from experts. Quantified preferences (e.g., % selecting priorities/solutions). |

| Stakeholder Forum (Jan 2024) | Mapped stakeholders’ influence and interest; established Stakeholder Board and project vision. | 31 participants (city officials, NGO leaders, residents, business owners). |

| Co-Design Workshop 1 (Feb 2024) | Brainstormed community needs and ideas for the whole neighborhood (with a focus on the urban forest); facilitated inclusive discussions and mappings. | 30 local residents (mixed ages and genders; included youth and elderly). Notes, sketches, and idea lists were recorded. |

| Co-Design Workshop 2 (Mar 2024) | Presented and refined draft NbS designs with community feedback; prioritized design options. | 20 residents (many returning from W1). Collected written feedback, votes on options, and discussion transcripts. |

| Stakeholder Board Meetings (2024–2025) | Ongoing participatory governance meetings to co-manage implementation, review designs, and plan maintenance/activities. | Board members (subset of forum). Meeting minutes documenting decisions and action items. |

| Technical Assessments/Indicators (parallel to above) | Site surveys, climate measurements (indicators), and engineering analysis to ensure NbS feasibility and to monitor NbS efficiency. These run in parallel and inform the design integration. | Data outputs included site maps, CAD designs, environmental metrics (e.g., projected cooling effect), which were cross-checked with community priorities. |

| Community Needs or Preferences | Incorporated Design Response |

|---|---|

| Safe play areas for children and youth | The design successfully incorporates child-friendly play zones that allow for supervision by parents |

| Demand for ample shade in summer | Inclusion of a vine-covered pergola at the main entrance and the planting of additional shade trees along pathways |

| Spaces for cultural and educational activities (e.g., crafts, dance) | A small amphitheater has been included in the design, providing the community with a dedicated space for such events. One of the old storage rooms has been renovated and repurposed as a multipurpose space that can host workshops, classes, and other community-driven activities. |

| Safety measures on steep streets and terraces | Key areas, such as the main entrance, the newly designed access near the storage buildings, and the central gathering space, are all now fully accessible. The slope in the park’s lower section was softened to make it more manageable, and handrails were installed throughout the park to improve safety and accessibility. |

| Use of allergy-friendly vegetation and specific preferences for vegetation and plant types | While not all requests could be fully implemented, efforts were made to incorporate as many community suggestions as possible while ensuring the species chosen are best suited for the park’s environment. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Latinopoulos, D.; Pelaez-Sanchez, S.; Briega Martos, P.; Berruezo, E.; Outón, P. Transforming Public Space with Nature-Based Solutions: Lessons from Participatory Regeneration in Lorca, Spain. Land 2025, 14, 2066. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102066

Latinopoulos D, Pelaez-Sanchez S, Briega Martos P, Berruezo E, Outón P. Transforming Public Space with Nature-Based Solutions: Lessons from Participatory Regeneration in Lorca, Spain. Land. 2025; 14(10):2066. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102066

Chicago/Turabian StyleLatinopoulos, Dionysis, Sara Pelaez-Sanchez, Patricia Briega Martos, Enrique Berruezo, and Pablo Outón. 2025. "Transforming Public Space with Nature-Based Solutions: Lessons from Participatory Regeneration in Lorca, Spain" Land 14, no. 10: 2066. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102066

APA StyleLatinopoulos, D., Pelaez-Sanchez, S., Briega Martos, P., Berruezo, E., & Outón, P. (2025). Transforming Public Space with Nature-Based Solutions: Lessons from Participatory Regeneration in Lorca, Spain. Land, 14(10), 2066. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102066