Exploring the Transformation Path and Enlightenment of Border Cities: A Case Study of Jilong, Tibet, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Reviewing Border Cities: Lessons and Strategies

3. Materials and Methods

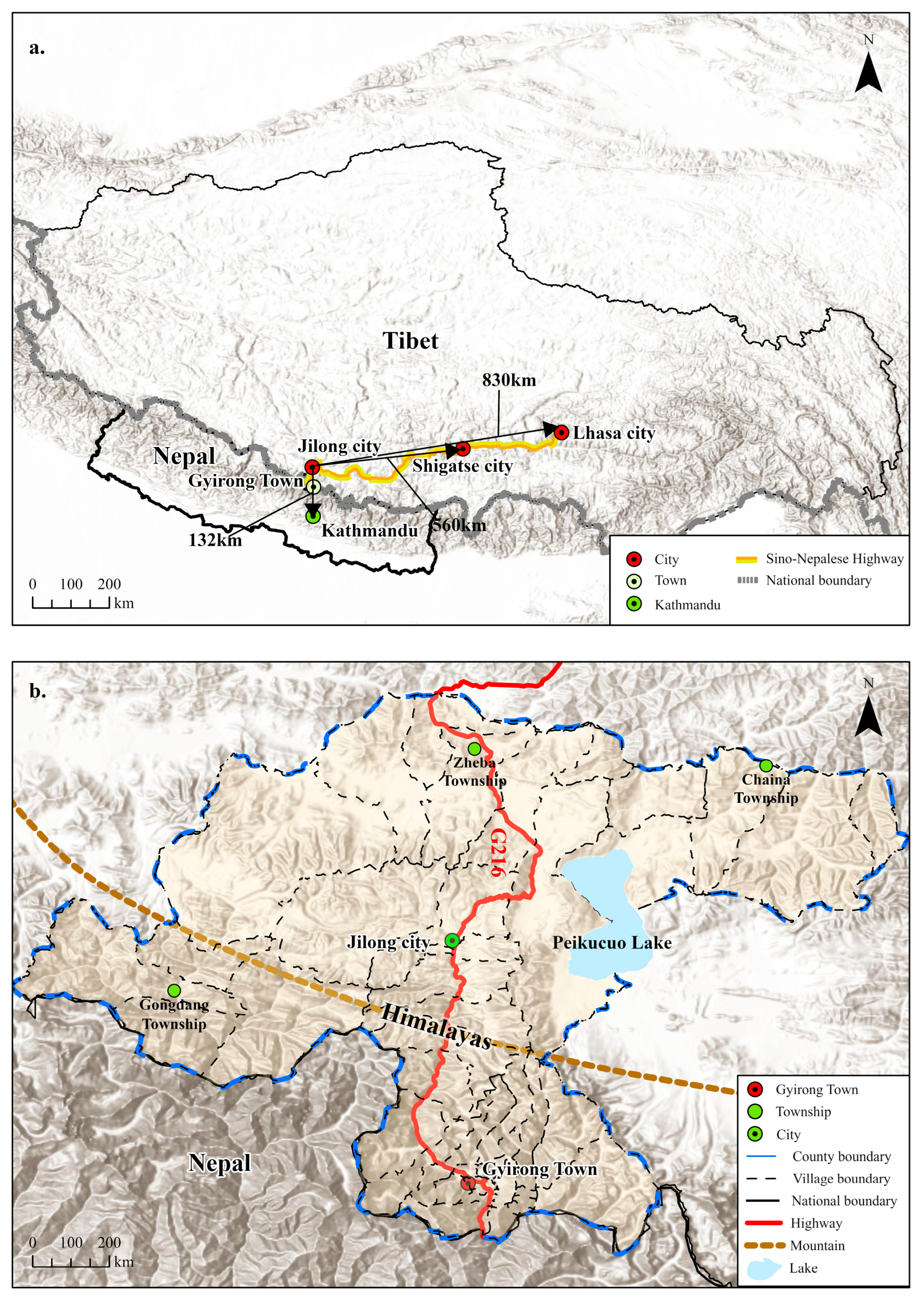

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Research Design and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

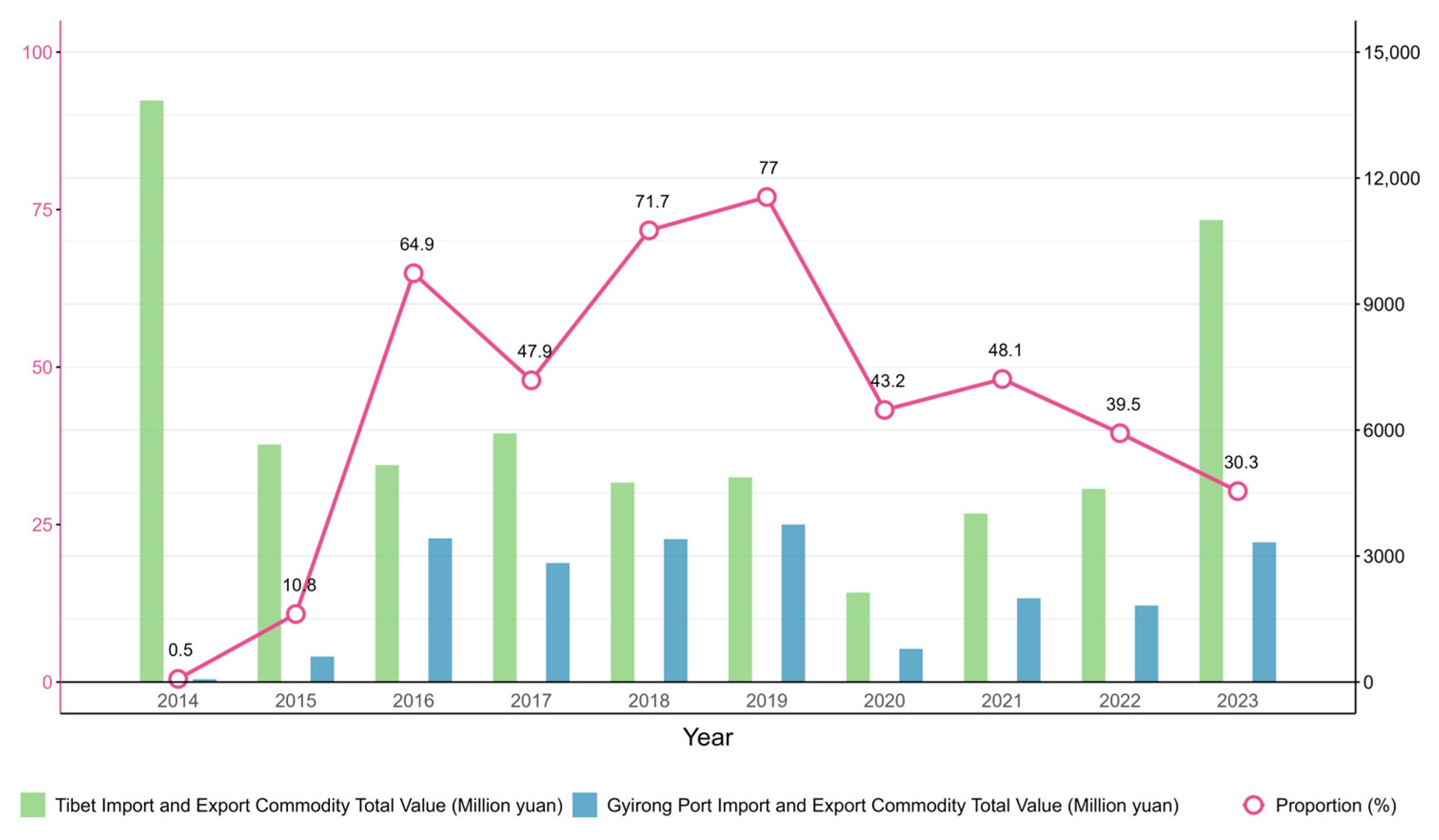

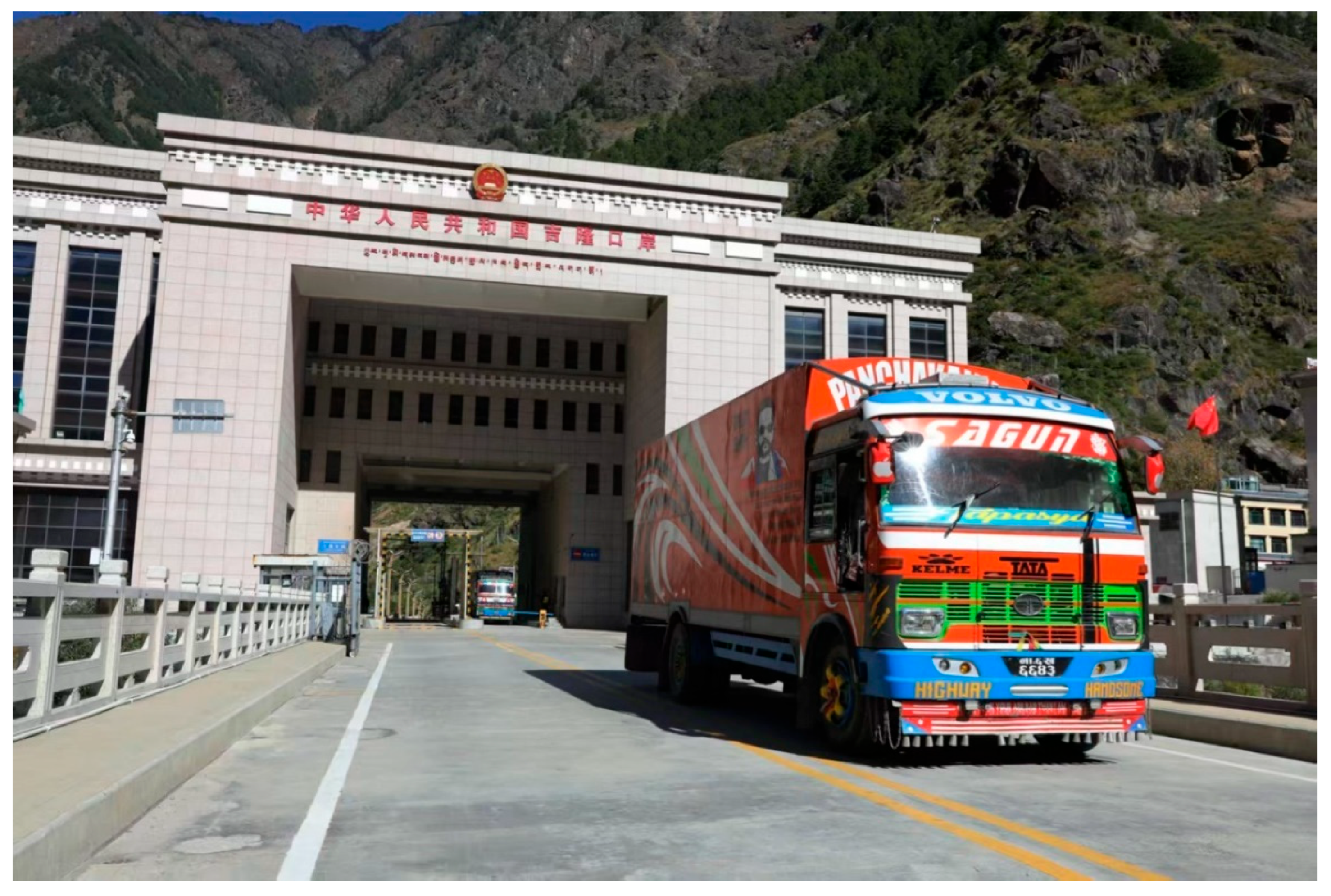

4.1. The Petty Trade Path in Border City

4.1.1. Phase I: Navigating the Petty Trade of the Border City

4.1.2. Phase 2: Petty Trade Transitions Since the 2015 Earthquake

4.1.3. Phase 3: The Diversified Development Propelled by the Belt and Road Initiative

4.2. Identifying the Development Factors of Border Cities

4.2.1. Ecological Fragility

4.2.2. Insufficient Infrastructure

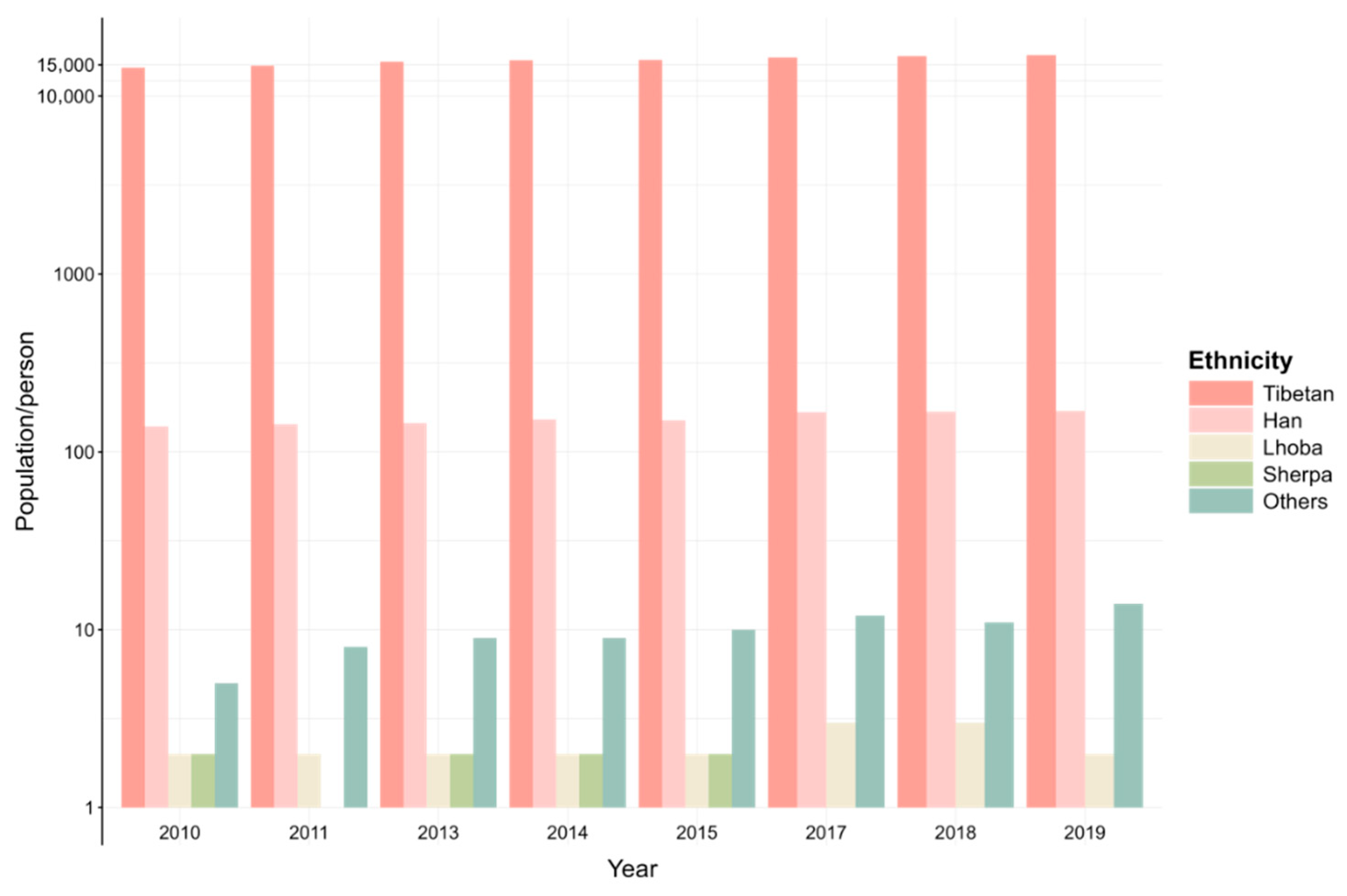

4.2.3. Labor Force Predicament

4.2.4. Policy Support

4.3. Strategies and Insights for the Transformation of Border Cities

4.3.1. Enhance Cross-Border Cooperation

4.3.2. Diversified Development of Industries

4.3.3. Strengthen Infrastructure Construction

4.3.4. Implementing a Talent Introduction and Cultivation Plan

4.3.5. Constructing Policies Tailored to Local Conditions

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Age | Ethnicity | Main Points | Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government officials | 48 | Tibetan | The ecological environment of Jilong city is relatively fragile, possessing a constrained capacity for resource carrying. | GO01 |

| 52 | Tibetan | In Jilong city, the degree of urbanization remains notably low, with a paucity of public service facilities. | GO02 | |

| 36 | Tibetan | JBEZ has garnered substantial investments, fostering the advancement of the processing industry and tourism. | GO03 | |

| 55 | Han | Owing to its elevated altitude and constrained space for human habitation and development, Jilong city incurs significant expenses for both developmental and security purposes. | GO04 | |

| 41 | Tibetan | The frequent geological disasters in Jilong city have notably exacerbated the challenges associated with ecological governance. | GO05 | |

| 59 | Han | Jilong city faces dual challenges in its governance: a vulnerable ecological environment and a precarious foundation for agricultural and livestock production. | GO06 | |

| 33 | Tibetan | To boost household income, the manufacturing industry should prioritize developing distinctive ethnic handicrafts. | GO07 | |

| 45 | Tibetan | Full integration of culture and tourism through the utilization of Jilong’s natural and cultural heritage. | GO08 | |

| 50 | Tibetan | Prioritizing transportation infrastructure planning in Jilong city and accelerating the China–Nepal cross-border railway project. | GO09 | |

| 38 | Han | The frequency of earthquakes and other geological disasters in Jilong city lead to the destruction of infrastructure such as housing and roads, disrupting the livelihoods of the residents. | GO10 | |

| 56 | Tibetan | Recent years have seen a substantial rise in tourism in Jilong city, necessitating an improvement in government service capabilities and the enhancement of infrastructure. | GO11 | |

| 43 | Han | Jilong city should integrate ecological and environmental protection into its overall development strategy. | GO12 | |

| 29 | Tibetan | The potential should be harnessed to elevate the significance of Jilong Port in bolstering trade and cultural connections with Nepal. | GO13 | |

| 47 | Tibetan | The Jilong government promotes tourism development by strengthening tourism publicity, organizing large-scale events, and creating distinctive cultural and tourism brands. | GO14 | |

| 54 | Tibetan | The establishment of the JBEZ constitutes a pivotal development platform for Jilong city. Concurrently, the government proactively implements supportive policies to facilitate the comprehensive advancement of Jilong. | GO15 | |

| 39 | Tibetan | Jilong city is characterized by a small population size and a limited availability of talents. | GO16 | |

| 51 | Han | With support from national funds, Jilong city has enhanced infrastructure construction and advanced post-disaster reconstruction efforts. | GO17 | |

| 57 | Tibetan | The establishment of JBEZ has drawn a considerable number of businesses to Jilong city, thereby infusing a new dynamism into the area’s economic development. | GO18 | |

| 48 | Tibetan | JBEZ has introduced 24 related enterprises, and the number of foreign trade enterprises registered in Jilong has exceeded 200. | GO19 | |

| 49 | Tibetan | The government has opened a convenient government service hall in JBEZ, dedicated to serving enterprises and residents. | GO20 | |

| Managers of entrepreneurs | 32 | Tibetan | The shortage of water supply, drainage, and sewage treatment infrastructure in Jilong city poses significant obstacles to enterprise development. | ME01 |

| 45 | Tibetan | The operation of the China–Nepal cross-border railway will serve as a catalyst for enhancing bilateral trade at Jilong city. | ME02 | |

| 51 | Han | Within the framework of JBEZ, the government has implemented diverse policies to offer comprehensive nanny-like services. The purpose of these government services is to expedite the process of enterprise establishment and production. | ME03 | |

| 28 | Tibetan | The border city is characterized by severe living conditions, resulting in a twofold talent development deficit: they struggle to consistently attract high-quality talents from external sources, and there is a noticeable lack of professional skills among local talents. | ME04 | |

| 56 | Tibetan | The underdeveloped infrastructure of Jilong city presents a significant impediment to development, and its road transport system is notably susceptible to natural disasters. | ME05 | |

| 39 | Han | The LSTC multimodal transport corridor enhances the logistics system by bolstering freight efficiency and diminishing transportation expenses. | ME06 | |

| 48 | Tibetan | Joining the LSTC has improved Jilong’s transport links with inland Chinese cities and created new trade channels. | ME07 | |

| 36 | Tibetan | The LSTC multimodal transport has significantly enhanced the market competitiveness of Chinese new energy vehicles in Nepal through reducing logistics costs. | ME08 | |

| 53 | Tibetan | Jilong Customs has implemented a dedicated declaration window for domestically produced new energy vehicles. This measure is a significant factor contributing to its substantial increase in export volumes in recent years. | ME09 | |

| 41 | Tibetan | Customs clearance efficiency at ports is a critical concern for enterprises, as it directly impacts their costs and loss rates. | ME10 | |

| 59 | Tibetan | A key factor enticing enterprises to invest in Jilong city is the distinctive policies offered by JBEZ, including tax incentives and central financial subsidies. | ME11 | |

| 34 | Tibetan | Jilong port, serving as a significant gateway to the Belt and Road, has garnered considerable attention from businesses seeking to establish operations. This strategic location enables them to effectively access and penetrate emerging markets. | ME12 | |

| 50 | Tibetan | The allure of Jilong for Chinese herbal medicine companies lies in its copious local medicinal materials, coupled with the imported ones received through the port. | ME13 | |

| 43 | Han | The company’s investment in Jilong city was driven by the potential long-term strategic opportunities offered by foreign trade and the Belt and Road Initiative. | ME14 | |

| 47 | Tibetan | The construction of the China–Nepal cross-border railway has garnered significant attention from enterprises, who anticipate that it will reduce transport costs and expedite delivery times via rail transport. | ME15 | |

| Residents and tourists | 22 | Han | Due to its close proximity to Nepal, Jilong city offers a unique opportunity to immerse oneself in Nepali culture. Meanwhile, it attracts a significant number of Nepalese visitors who arrive via the Jilong port. | RT01 |

| 35 | Tibetan | During the COVID-19 pandemic, the exchange of both trade and people between Jilong city and Nepal was nearly suspended. | RT02 | |

| 64 | Tibetan | The implementation of the grassland ecological protection subsidy and reward policy has led to notable improvements in the grassland ecological environment, as well as an increase in income for farmers and herdsmen. | RT03 | |

| 29 | Tibetan | The contrast between the off- and on-season in Jilong’s tourism industry is highly pronounced, with recurrent road construction frequently impeding transportation. | RT04 | |

| 42 | Tibetan | In recent years, Jilong city saw a rise in tourist numbers, which included many international visitors. | RT05 | |

| 37 | Tibetan | The influx of a significant number of tourists has also led to issues such as environmental degradation. | RT06 | |

| 56 | Han | Historically, the trade goods available at Jilong Port were limited and mainly comprised traditional primary products. | RT07 | |

| 25 | Tibetan | Short video platforms such as TikTok significantly boosted Jilong’s popularity, thereby attracting a large number of visitors. | RT08 | |

| 31 | Tibetan | In Jilong city, numerous Nepali shops exist where individuals can purchase a variety of Nepali products and frequently encounter Nepali people. | RT09 | |

| 51 | Tibetan | The surge in tourism has prompted local residents to establish homestays, restaurants, and various other service-oriented businesses as their primary source of income. | RT10 | |

| 45 | Tibetan | While the state-issued ecological protection subsidy has somewhat augmented the income of herdsmen, there remains ambiguity regarding the future production modes they can potentially develop. | RT11 | |

| 56 | Tibetan | As an important channel leading to the Jilong Port, the highway is vulnerable to natural disasters such as earthquakes and flash floods. | RT12 | |

| 48 | Tibetan | Jilong, a border city situated at the China–Nepal border, has seen a significant influx of Nepalese migrant workers, predominantly employed in the service sector. | RT13 | |

| 26 | Tibetan | Tourists are drawn to Jilong primarily for its natural beauty and its unique features as a border city. | RT14 | |

| 33 | Tibetan | As an increasing number of enterprises establish operations in Jilong city, the local populace now has more opportunities to find employment within the region. | RT15 | |

| 24 | Han | Jilong city boasts of exquisite natural scenery. Additionally, its status as a Chinese–Nepalese border city imbues it with a rich Nepalese character. This is evident in the local Nepalese shops where Nepalese shopkeepers are a common sight. | RT16 | |

| 29 | Tibetan | Despite its stunning natural landscape, Jilong city is confronted with notable challenges including inconvenient transportation and inadequate signal coverage. | RT17 |

References

- United Nations Sustainable Development Action. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Robinson, J. Developing ordinary cities: City visioning processes in Durban and Johannesburg. Environ. Plan. A 2008, 40, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Korah, P.I.; Dongzagla, A.; Nunbogu, A.M.; Niminga-Bekad, R.; Kuusaanae, E.D.; Abubakar, Z. City profile: Wa, Ghana. Cities 2020, 97, 102524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Chahine, T.; Sun, M. Ruili, China: The China-Myanmar nexus hub at the crossroads. Cities 2020, 104, 102766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, S. Towards a paradigm of Southern urbanism. City 2017, 21, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D. The new urban imperative for secondary cities. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III), Quito, Ecuador, 17–20 October 2016; UN-Habitat: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.J. Three waves of state-led gentrification in China. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2019, 110, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, F. Rethinking China’s urban governance: The role of the state in neighbourhoods, cities and regions. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2022, 46, 775–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Guo, Y.; Chen, W. Assembling plateau urbanism through special economic zones: Evidence from the Tibetan Plateau, China. Cities 2024, 149, 104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, H.W. Strategic Coupling: East Asian Industrial Transformation in the New Global Economy; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N. Open questions on state rescaling. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2009, 2, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Robinson, C.; Bouzarovski, S. China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the emerging geographies of global urbanisation. Geogr. J. 2020, 186, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Li, K.; Cong, N.; Wu, S.; Peng, F. Spatial-Temporal Variation Characteristics and Obstacle Factors of Resilience in Border Cities of Northeast China. Land 2023, 12, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, F.; Chen, Q. Ice and snow tourism in China’s ecological civilization era: The Altay, Xinjiang experience. Habitat Int. 2025, 159, 103375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, C. The border as a resource in the global urban space: A contribution to the cross-border metropolis hypothesis. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1697–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N. New State Spaces: Urban Governance and the Rescaling of Statehood; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Moisio, S.; Paasi, A. From Geopolitical to Geoeconomic? The Changing Political Rationalities of State Space. Geopolitics 2013, 18, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Sun, M.; Liu, Z. Grounding border city regionalism in contemporary China: Evidence from Ruili and Mengla in Yunnan province. Territ. Polit. Gov. 2022, 12, 1158–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokkola, E.-K. Border-regional resilience in EU internal and external border areas in Finland. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 1587–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, J. The Territorial Trap: The Geographical Assumptions of International Relations Theory. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 1994, 1, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptak, T.; Laine, J.; Hu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Konrad, V.; Velde, M. Understanding borders through dynamic processes: Capturing relational motion from south-west China’s radiation centre. Territ. Polit. Gov. 2022, 10, 834–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yuan, Z. Making a safer space? Rethinking space and securitization in the old town redevelopment project of Kashgar, China. Polit. Geogr. 2019, 69, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatter, J. Beyond hierarchies and networks: Institutional logics and change in transboundary spaces. Governance 2003, 16, 503–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Hassink, R. Regional resilience: The critique revisited. In Creating Resilient Economies; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2016; pp. 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakola, F. Borders, planning and policy transfer: Historical transformation of development discourses in the Finnish Torne Valley. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 1806–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blatter, J. Emerging cross-border regions as a step towards sustainable development? Experiences and considerations from examples in Europe and North America. Int. J. Econ. Dev. 2000, 2, 402–439. [Google Scholar]

- Su, X.; Li, C. Bordering dynamics and the geopolitics of cross-border tourism between China and Myanmar. Polit. Geogr. 2021, 86, 102372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.F. Researching state rescaling in China: Methodological reflections. Area Dev. Policy 2018, 3, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimer, M.; Thøgersen, S. Doing Fieldwork in China; NIAS Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Paudel, D.; Le Billon, P. Geo-logics of power: Disaster capitalism, Himalayan materialities, and the geopolitical economy of reconstruction in post-earthquake Nepal. Geopolitics 2018, 25, 838–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, T.; Su, K. Exploring the evolution process and driving mechanism of traditional trade routes in Himalayan region. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2021, 76, 2157–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.K.; Adhikari, K.P.; Acharya, B.; Lamichhane, K.; Mishra, M.; Sijapati, D.B. Private housing compliance with public seismic safety measures after 2015 Gorkha earthquake in Nepal. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 111, 104690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murton, G.; Lord, A.; Beazley, R. “A handshake across the Himalayas”: Chinese investment, hydropower development, and state formation in Nepal. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2016, 57, 403–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memorandum of Understanding Between the Ministry of Commerce of China and the Ministry of Industry of Nepal on the Establishment of the China-Nepal Cross-Border Economic Cooperation Zone. Available online: http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ae/ai/201705/20170502575229.shtml (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Hazardous Ideas for the Himalayas: Hydroelectric Projects of India and China. Available online: https://www.visionias.net/2020/12/hazardous-ideas-for-the-himalayas-hydroelectric-projects-of-india-and-china.html (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Vision and Proposed Actions Outlined on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road. Available online: https://language.chinadaily.com.cn/2015-03/30/content_19950951.htm (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Gyirong Port—The Only Opened Overland Pass Between Nepal & Tibet. Available online: https://www.tibetdiscovery.com/tibet-ports/gyirong-port/ (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- China, Nepal Upgrade Ties. Available online: https://english.www.gov.cn/news/topnews/201910/13/content_WS5da28059c6d0bcf8c4c14fd0.html (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Tibet Accelerates Integration into the Construction of the Western Land-Sea New Channel. Available online: https://www.stdaily.com/web/gdxw/2025-05/07/content_335870.html (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Syafrini, D.; Nurdin, M.F.; Sugandi, Y.S.; Miko, A. Transformation of a coal mining city into a cultured mining heritage tourism city in Sawahlunto, Indonesia: A response to the threat of becoming a ghost town. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2022, 19, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murton, G. Beyond the BRI: The volumetric presence of China in Nepal. Territ. Polit. Gov. 2023, 12, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal Hopes Riding on Cross-Border Rail. Available online: https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202301/07/WS63b8c7e5a31057c47eba83a0.html (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Bhandari, B.D. Belt and Road Cooperation: Shaping a Brighter Shared Future. In Proceedings of the 2nd Belt and Road Forum, Beijing, China, 25–27 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Song, T.; Liu, W.; Liu, Z.; Wuzhati, Y. Policy mobilities and the China model: Pairing aid policy in Xinjiang. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyirong County: The Aid-Tibet Project Provides Strong Impetus for High-Quality Development. Shigatse Munic. Available online: http://www.rikaze.gov.cn/content/2024/438583.html (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Jilong Border Area: Transforming from a Frontier Town to an Open Highland-The Metamorphosis of an Economic Miracle. Available online: https://rikaze.xzdw.gov.cn/xwzx_455/xsdt/202501/t20250118_543815.html (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Wang, W.; Wu, F.; Zhang, F. Assembling state power through rescaling: Inter-jurisdictional development in the Beijing-Tianjin Zhongguancun Tech Town. Polit. Geogr. 2024, 112, 103131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 14th Five-Year Plan and the Long-Range Objectives through the Year 2035 for National Economic and Social Development in Tibet Autonomous Region. Available online: https://drc.xizang.gov.cn/xwzx/daod/202103/t20210329_197641.html (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Lu, X. Re-territorializing Mengla: From “backwater” to “bridgehead” of China’s socio-economic development. Cities 2021, 117, 103311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibet’s Jilong Border Economic Cooperation Zone Project Progress. Available online: https://www.cdi.org.cn/Article/Detail?Id=17224 (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Arnaud, B. Neoliberalizing state spaces in postwar Western Europe: The emergence of a new integrative regime of sovereignty. Polit. Geogr. 2022, 97, 102694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, S. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Parnell, S.; Robinson, J. (Re)theorizing cities from the Global South: Looking beyond neoliberalism. Urban Geogr. 2013, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ling, J.; He, S. Actually existing state entrepreneurialism: From conceptualization to materialization. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2023, 48, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Port | Distance from Shigatse (km) | Distance from Kathmandu (km) | Population (Person) | Area (km2) | Elevation (m) | Counterpart City in Nepal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jilong | 560 | 132 | 3946 | 747 | 2600 | Rasuwa District |

| Zhangmu | 473 | 120 | 2184 | 334 | 2300 | Sindhupalchowk District |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, T.; Wang, S.; Song, Z. Exploring the Transformation Path and Enlightenment of Border Cities: A Case Study of Jilong, Tibet, China. Land 2025, 14, 1935. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14101935

Song T, Wang S, Song Z. Exploring the Transformation Path and Enlightenment of Border Cities: A Case Study of Jilong, Tibet, China. Land. 2025; 14(10):1935. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14101935

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Tao, Shiyu Wang, and Zhouying Song. 2025. "Exploring the Transformation Path and Enlightenment of Border Cities: A Case Study of Jilong, Tibet, China" Land 14, no. 10: 1935. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14101935

APA StyleSong, T., Wang, S., & Song, Z. (2025). Exploring the Transformation Path and Enlightenment of Border Cities: A Case Study of Jilong, Tibet, China. Land, 14(10), 1935. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14101935