Loving and Healing a Hurt City: Planning a Green Monterrey Metropolitan Area

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Urban Problems

2.2. Emotions and Urban Planning

| Love is a fire that burns unseen; |

| It’s a wound that hurts and doesn’t feel; |

| It is discontented contentment; |

| It is a pain that goes unnoticed without hurting. |

| It’s not wanting more than wanting well; |

| It’s a lonely walk between us; |

| It’s never to settle for happiness; |

| It is a care that gains in losing itself. |

| It’s wanting to be trapped by will; |

| It’s serving those who win the winner; |

| Have someone kill us, loyalty. |

| But how to cause can your favor |

| In human hearts friendship, |

| If so, contrary to itself, is it the same love? |

2.3. Earth Emotions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Monterrey Metropolitan Area (MMA)

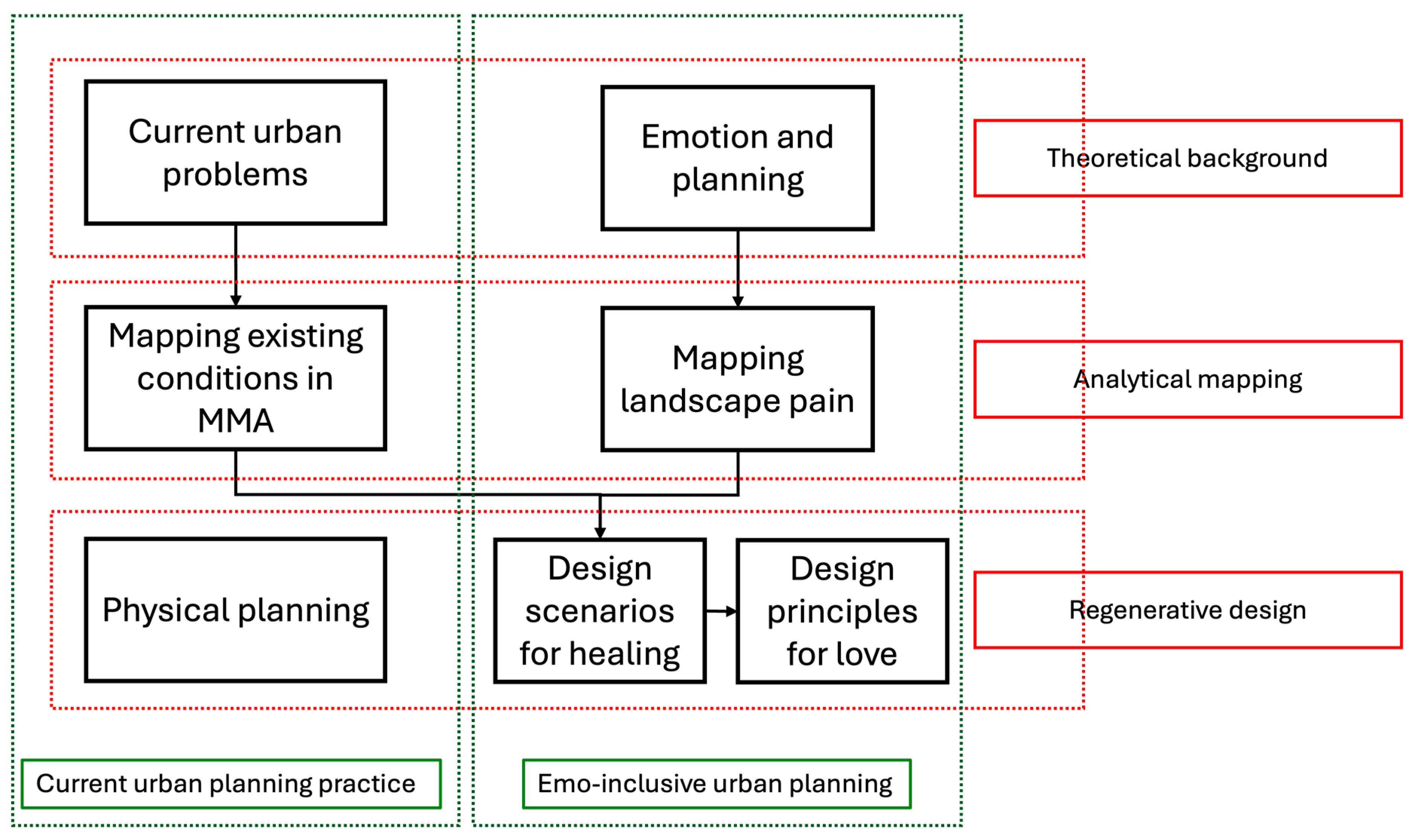

3.2. Methods

4. Results

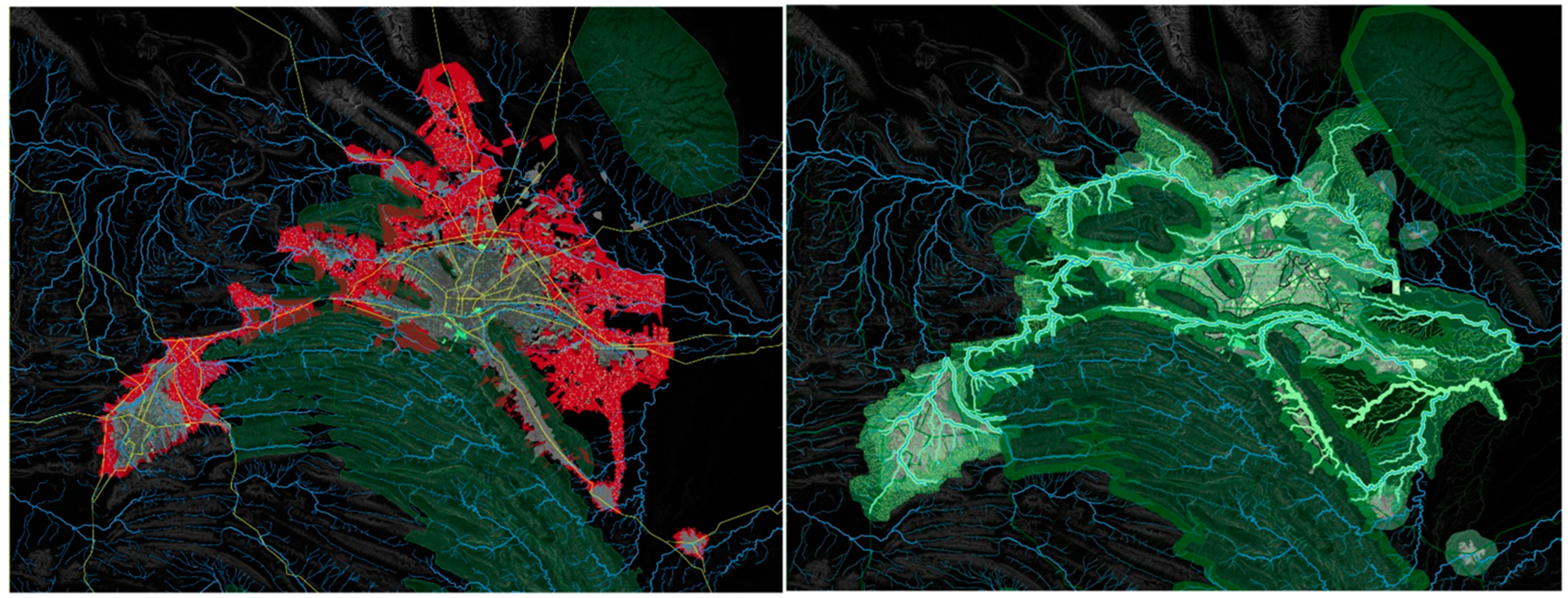

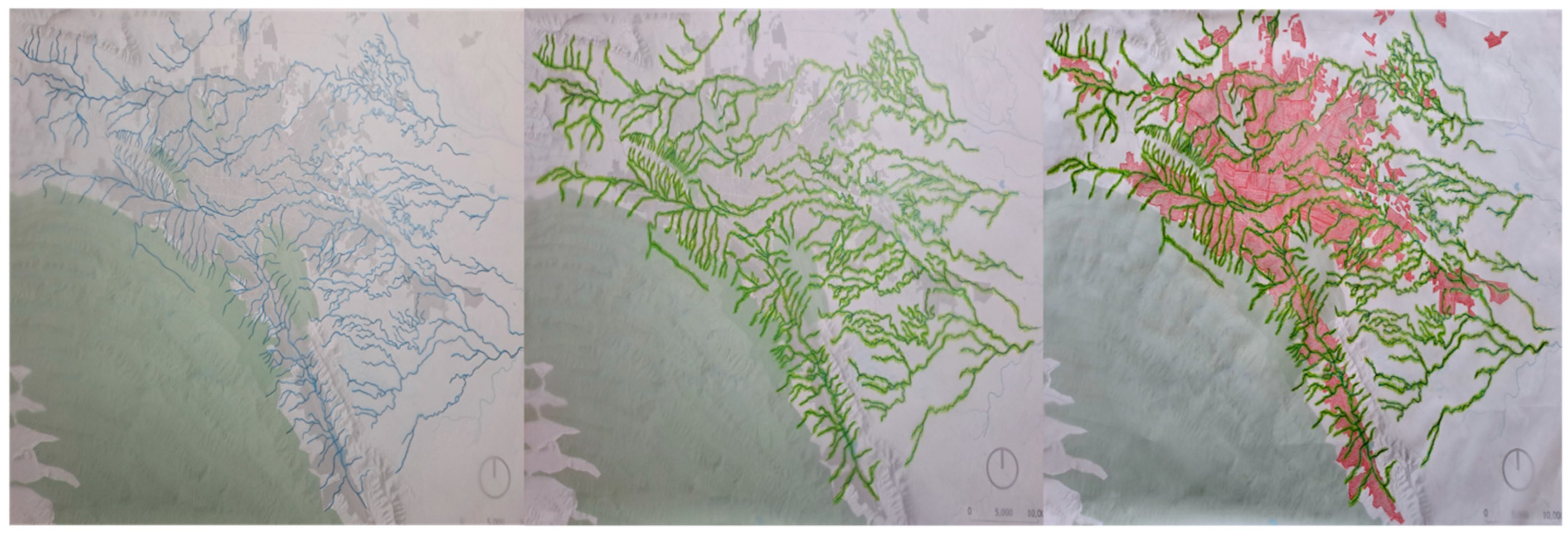

4.1. Discrepancy Between the Natural Qualities and Urban Impacts

4.2. Need to Distinguish Between the Pain, Healing, and Love

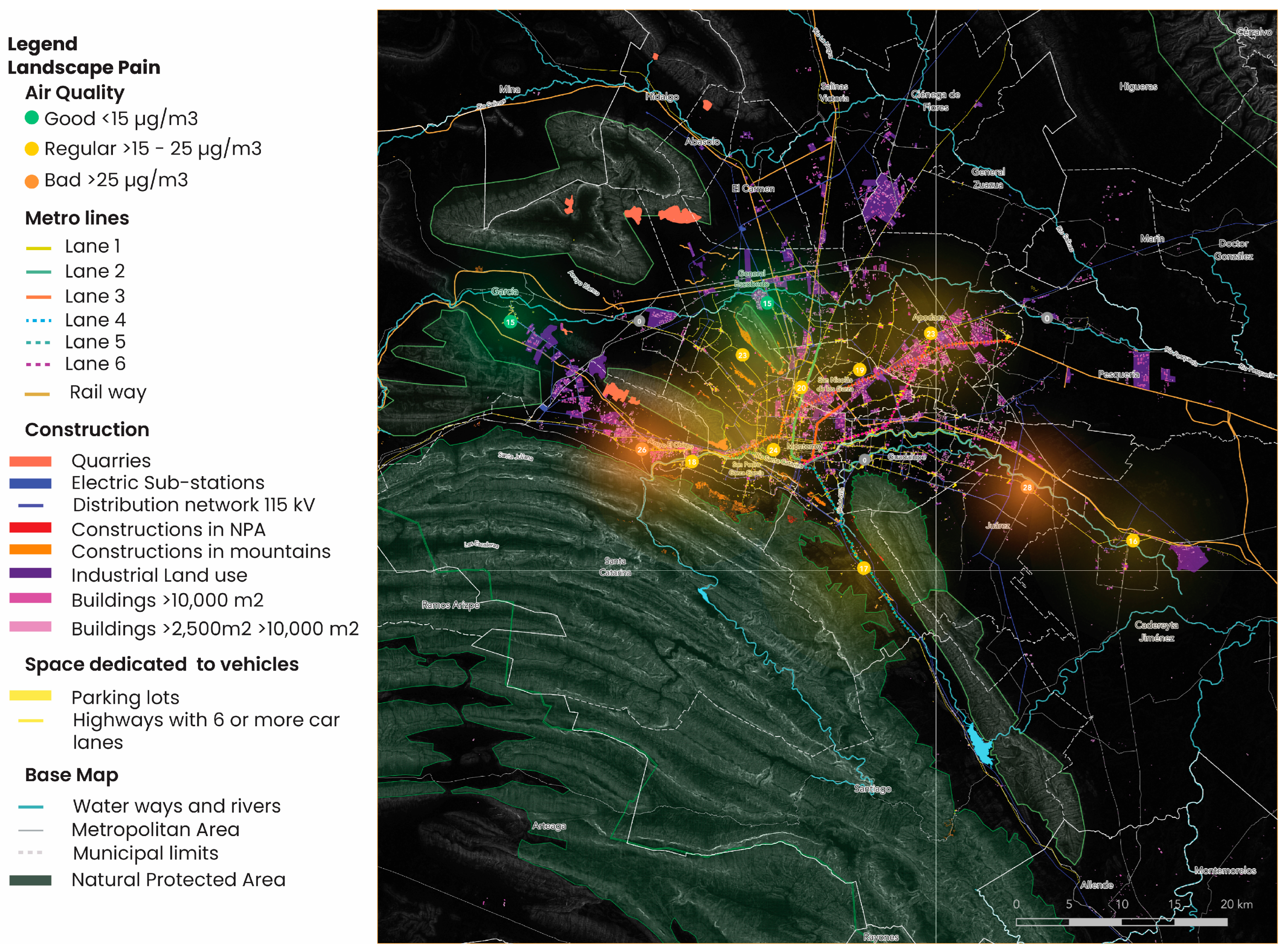

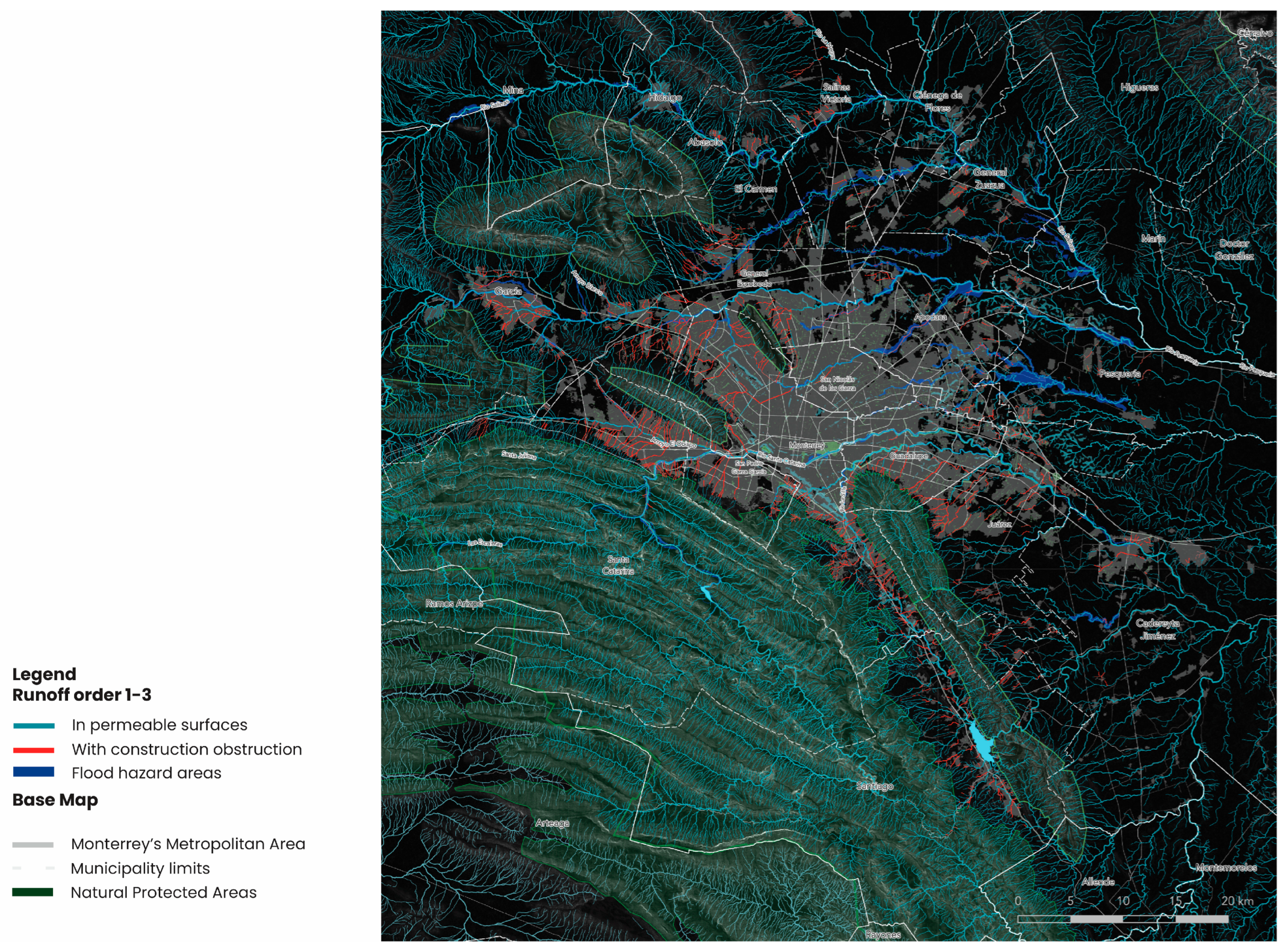

- (Landscape) Pain—The painful emotions (visual, emotional, physical, and health) highlight all elements that people experience as unpleasant or hurting. Landscape pain has been identified as the estimated visual and/or environmental problems, in a qualitative analysis, based on the individual mapping of specific topics (Section 4.3).

- Heal—The healing opportunities were the solutions for the identified problems (pain), in the form of the scenarios and greening strategy (this is a research-by-design and creative step and not derived explicitly from data). These emotions can help to compensate for and repair pain, resolving the environmental or visual pain. This way, healthy landscapes reduce the negative impacts induced. Air and water pollution are reduced to acceptable levels, visual landscape disturbances are removed, and spatial misfits, such as too-large constructions and too-broad infrastructures are reduced in size. The scale at which healing is most effective is at the systems or structural level and at the source of the pain (e.g., emission of toxic pollutants).

- Love—This is a projection of design principles for several characteristic spaces in the city, for instance where the pain is most felt (heavy infrastructure or visual barriers for example), or where opportunities emerged (hydrological corridors for example). These emotions indicate the transformations of public spaces to make them attractive for the residents (human and non-human) to access, spend time with or in, and appreciate. This goes beyond the reparation of negative impacts (pain) but improves the quality of the direct environment, often at the (hyper)local scale.

4.3. Landscape Pain Is Widespread

- Quarries and constructions in nature reserves. In the Monterrey Metropolitan Area (MMA), 1289 ha. are excavations (quarries) found on slopes in mountain zones. In addition, 29,928 constructions (houses or other buildings) are located on slopes of mountains and hills. Of these constructions, 3497 are in Natural Protected Areas.

- Green spaces. There is a lack of access to green spaces and a limited amount of green space per person. In the entire Metropolitan Area, including the urban fringes and agricultural land, there is 22.2 m2 of green space per inhabitant. However, these green spaces are not equitably accessible to all inhabitants, and the indicator is not representative of a green city compared to the 51 m2 per capita in Barcelona [95]. At the same time, it is advised to have a minimum of 9.5 m2 of green space per inhabitant [111]. Although this indicator is outdated and is average, while urban areas are composed of very different densities, functionalities, and activities, it still indicates how well cities do. When parks and green spaces in the urban precincts of the Monterrey Metropolitan Area are calculated, there is only a mere 4 m2 of green space per capita.Furthermore, applying the 3-30-300 rule [112], the advised 30% of tree cover is only met in 50% of the Monterrey Metropolitan Area, and only 43% of the population has access to a green public space within 300 m or a five-minute walk [113]. For vulnerable groups such as children (25%) and elderly (40%), this accessibility is even lower. This unbalanced distribution of green spaces over the different neighborhoods in the city leads to the most vulnerable urban population living in the hottest conditions, suffering from urban heat [114]. In Monterrey, approximately 40% of the population that faces a medium or high social gap [97] has access to a public green space.

- Main roads (over six lanes) and surface parking. In the MMA 670 km of highways, over six lanes are found and over 996 ha. for parking, which is two-thirds of the space allocated for public parks. The emissions caused by the cars using this infrastructure are estimated at 7,764,568 tons of CO2/year. This car infrastructure has profound impacts on human health through air pollution [115], soil degradation [116], and a general decline in quality of life [117].

- Large-size buildings. In the MMA, 972 buildings of over 10,000 m2 and another 7628 between 2500 and 10,000 m2 are found. These buildings, mainly logistics and industrial, have no or a significant deficit of green spaces on and around them. It causes large, uncovered surfaces, which are a primary cause of the urban heat island effect [118,119].

- Rail tracks and public transport are elevated above ground (metro system). The 411 km of rail tracks provide a noise problem, as many of these lines generate 80–100 dB [120] and 19.3 km of elevated metro lines. The transportation network exaggerates barriers between neighborhoods, rivers, and green spaces, creating problematic underpasses that reduce the views of the mountainous landscape.

- Polluting industries such as the Pemex refinery emit the majority of PM10 and PM2.5 particles, causing adverse effects on human health and causing life-threatening diseases [121]. It is estimated that, in 2021, 1684 deaths were directly related to air pollution.

4.4. Healing

4.5. Love

- The hydro-ecological corridors (Figure 7) are revived as linear elements located where the original creeks flowed. The design principle aims to integrate nature into the city, re-naturalize watersheds [117], and reduce temperatures in the MMA. The transformation from an impermeable street without green and trees under which the waterway is hidden into a pleasant space for people to linger and enjoy it from their homes has not only environmental benefits but also invites people to go out and use the space and be close to nature.

- 2.

- Water retention spaces (Figure 8) are located in areas where water runs off the mountain slopes, and there is a serious risk of flooding. The retention basins or ponds are designed to recharge the aquifer by infiltration and water absorption into the soil, and in the meantime, will reduce flood risk and improve the natural habitat. These spaces are crucial to slowing down runoff water, storing it, and releasing it slowly, but they also present an attractive small park to the people where they can experience nature, cooler temperatures, contemplate, and relax. It transforms an old quarry, currently a neglected space, into an area where people can relate to and spend time.

- 3.

- Green islands have high permeability, contrary to concrete squares, roofs, or facades. This design principle aims to allow nature to reconquer these spaces and surfaces. This way, green areas emerge and are integrated into neighborhoods through small parks, green roofs, and vertical green facades. For example, people can use these novel green spaces as an urban food garden. These implementations allow people to become active and collaborate on planting and harvesting collectively grown crops. These practices improve social cohesion in the neighborhood, and people feel more attached to their direct environment [139,140]. As an additional benefit, these green spaces reduce the impervious surface, regulate the temperature, minimize urban heat, and capture excess rainwater.

- 4.

- Greenways are spaces aligned with the road and rail network. Many of these left-over spaces are neglected and have become unsafe and unpleasant, turning into spatial barriers that are difficult to cross for pedestrians. By proposing to improve the spatial quality using green and natural vegetation and clear paths and routes, these spaces can become a place for people to rest and safely cross these infrastructures. They could even become spaces where the residents spend more time for play or recreation since they feel more at ease. In addition, these areas can regulate the local water system and can prevent droughts and floods, and biodiversity is enhanced.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Pain is primarily focused on experienced problems, and mapping pain is an analytical process on a regional-to-local scale. It visualizes the current situation.

- Healing is oriented towards the systemic strategies that can heal broken elements and landscapes in the metropolis; hence, it is working on a regional scale and focusing on the future.

- Love aims to develop concrete future design solutions for the (hyper)local scale at the neighborhood and public space extents.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision, (ST/ESA/SER.A/366); United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision (ST/ESA/SER.A/420); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2021 Urban Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/urban-health (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- UNEP. Cities and Climate Change. Available online: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/resource-efficiency/what-we-do/cities-and-climate-change#:~:text=Rising%20global%20temperatures%20causes%20sea,housing%2C%20human%20livelihoods%20and%20health (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- IPCC. IPCC, 2022: Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability; Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2008; IEA: Paris, France, 2008; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2008 (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Dhakal, S. Climate change and cities: The making of a climate friendly future. In Urban Energy Transition: From Fossil Fuel to Renewable Power; Droege, P., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Poumanyvong, P.; Kaneko, S. Does urbanization lead to less energy use and lower CO2 emissions? A cross-country analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 70, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.C.; Dalton, M.; Fuchs, R.; Jiang, L.; Pachauri, S.; Zigova, K. Global demographic trends and future carbon emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 17521–17526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, H.K.; Hamoodi, M.; Al-Hameedawi, A.N. Urban heat islands: A review of contributing factors, effects and data. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1129, 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Sustainable, Resource Efficient Cities—Making it Happen! UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/1124SustainableResourceEfficientCities.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Molina, M.J.; Molina, L.T. Megacities and Atmospheric Pollution. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2004, 54, 644–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqua, A.; Hahladakis, J.N.; Al-Attiya, W.A.K. An overview of the environmental pollution and health effects associated with waste landfilling and open dumping. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 58514–58536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakács, T. Public health problems in metropolitan areas. In Metropolitan Problems; Miles, S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 191–213. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Climate Change and Social Vulnerability in the United States: A Focus on Six Impacts. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2021. EPA 430-R-21-003. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/cira/social-vulnerability-report (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Vernberg, W.B.; Scott, G.I.; Strozier, S.H.; Bemiss, J.; Daugomah, J.W. The Effects of Urbanization on Human and Ecosystem Health. In Sustainable Development in the Southeastern Coastal Zone; Vernberg, F.J., Vernberg, W.B., Siewicki, T.S., Eds.; University of South Carolina Press: Columbia, South Carolina, 1996; pp. 221–239. [Google Scholar]

- Zipperer Wayne, C.; Northrop, R.; Andreu, M. Urban Development and Environmental Degradation. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science. 2020. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/environmentalscience/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.001.0001/acrefore-9780199389414-e-97 (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- McGrane, S.J. Impacts of urbanisation on hydrological and water quality dynamics, and urban water management: A review. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2016, 61, 2295–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Habitat Global State of Metropolis 2020. Population Data Booklet. UN Habitat: Nairobi, Kenia. 2020. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/09/gsm-population-data-booklet-2020_3.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Oxford Dictionaries. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20160307093630/http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/metropolis?q=Metropolis (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Collins Dictionary. Available online: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/metropolis (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Owen, D. Green Metropolis: Why Living Smaller, Living Closer, and Driving Less Are the Keys to Sustainability; Riverhead Books: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Beatley, T. Green Metropolis. A new book argues that Manhattan is the greenest city in the United States. Places J. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.A.; Andrade, J.S., Jr.; Makse, H.A. Large cities are less green. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; He, J.; Liu, D.; Zhao, H.; Huang, J. Inequality in urban green provision: A comparative study of large cities throughout the world. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripple, W.J.; Wolf, C.; Gregg, J.W.; Rockström, J.; Mann, M.E.; Oreskes, N.; Lenton, T.M.; Rahmstorf, S.; Newsome, T.M.; Xu, C.; et al. The 2024 state of the climate report: Perilous times on planet Earth. BioScience 2024, 74, biae087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN News Cities: A ’Cause of and Solution to’ Climate Change. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/09/1046662 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Kowarik, I. Novel urban ecosystems, biodiversity, and conservation. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 1974–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahers, J.-B.; Rosado, L. The material footprints of cities and importance of resource use indicators for urban circular economy policies: A comparison of urban metabolisms of Nantes-Saint-Nazaire and Gothenburg. Clean. Prod. Lett. 2023, 4, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, R.; Gargiulo, C.; Zucaro, F.; Angiello, G.; Carpentieri, G. Urban Energy Consumptions: Its Determinants and Future Research. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 191, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, J.; Zhou, B.; Barry, M. The impact of megacities on health: Preparing for a resilient future. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e176–e178. [Google Scholar]

- Cerón Breton, R.M.; Céron Breton, J.; De la Luz Espinosa Fuentes, M.; Kahl, J.; Espinosa Guzman, A.A.; Martínez, R.G.; Guarnaccia, C.; del Carmen Lara Severino, R.; Ramirez Lara, E.; Francavilla, A.B. Short-term associations between morbidity and air pollution in metropolitan area of Monterrey, Mexico. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.D.; Engelke, P.O. The built environment and human activity patterns: Exploring the impacts of urban form on public health. J. Plan. Lit. 2001, 16, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, R.P.; Hynes, H.P. Obesity, physical activity, and the urban environment: Public health research needs. Environ. Health 2006, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krefis, A.C.; Augustin, M.; Schlünzen, K.H.; Oßenbrügge, J.; Augustin, J. How does the urban environment affect health and well-being? A systematic review. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, N. Mental health, stress and the contemporary metropolis. In Urban Transformations and Public Health in the Emergent City; Keith, M., De Souza Santos, A.A., Eds.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2020; pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Iungman, T.; Cirach, M.; Marando, F.; Pereira-Barboza, E.; Khomenko, S.; Masselot, P.; Quijal-Zamorano, M.; Mueller, N.; Gasparrini, A.; Urquiza, J.; et al. Cooling cities through urban green infrastructure: A health impact assessment of European cities. Lancet 2023, 401, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathiany, S.; Dakos, V.; Scheffer, M.; Lenton, T.M. Climate models predict increasing temperature variability in poor countries. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaar5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashinze, U.K.; Edeigba, B.A.; Umoh, A.A.; Biu, P.W.; Daraojimba, A.I. Urban green infrastructure and its role in sustainable cities: A comprehensive review. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, E.; Comín, F.A. Urban Green Infrastructure and Sustainable Development: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, J. Green infrastructure for cities: The spatial dimension. In Cities of the Future Towards Integrated Sustainable Water and Landscape Management; Novotny, V., Brown, P., Eds.; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, A.; Cirella, G.T. Urban sustainability: Integrating ecology in city design and planning. In Sustainable Human–Nature Relations: Environmental Scholarship, Economic Evaluation, Urban Strategies; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 187–204. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zyl, B.; Cilliers, E.J.; Lategan, L.G.; Cilliers, S.S. Closing the gap between urban planning and urban ecology: A South African perspective. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Singh, R.; Singh, P.; Raghubanshi, A.S. Urban ecology–current state of research and concepts. In Urban Ecology; Verma, P., Singh, R., Singh, P., Raghubanshi, A.S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggema, R. Adaptation to Climate Change: A Spatial Challenge; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Araos, M.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Ford, J.D.; Austin, S.E.; Biesbroek, R.; Lesnikowski, A. Climate change adaptation planning in large cities: A systematic global assessment. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 66, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasini, R. The Symbiotic Field. Landscape Paradigms and Post-Urban Spaces; The Urban Book Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alsayed, S.S. Urban human needs: Conceptual framework to promoting urban city fulfills human desires. Front. Sustain. Cities 2024, 6, 1395980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupat, E. People in Cities. The Urban Environment and its Effects; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, A. Emotion and Urban Experience: Implications for Design. Des. Issues 2000, 16, 67–79. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1511816 (accessed on 21 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Lively, K.J.; Heise, D.R. Sociological realms of emotional experience. Am. J. Sociol. 2004, 109, 1109–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A. The sociology of emotions. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1989, 15, 317–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L.F.; Mesquita, B.; Ochsner, K.N.; Gross, J.J. The experience of emotion. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 373–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seamon, D. Emotional experience of the environment. Am. Behav. Sci. 1984, 27, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, A. Anthropology and emotion. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 2014, 20, 545–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, B.T. Emotional Geography. Ethnologia Europaea 2006, 36, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Thagard, P. Emotional cognition in urban planning. In Complexity, Cognition, Urban Planning and Design; Portugali, J., Stolk, E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 197–213. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, R. Affective landscapes: Capturing emotions in place. In The Routledge Handbook of Methodologies in Human Geography; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2022; pp. 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Vaz de Camoes, L. (1524–1589) Amor Um Fogo Que Arde Sem se Ver. Available online: https://allpoetry.com/Amor--um-fogo-que-arde-sem-se-ver#tr_8492145 (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Davidson, J.; Milligan, C. Embodying Emotion Sensing Space: Introducing Emotional Geographies. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2004, 5, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, G. The Metropolis and the Mental Life. In On Individuality and Social Forms; Levine, D., Ed.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1971; pp. 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Futrell, R. The Expendable City: Las Vegas and the Limits of Sustainability. Humboldt J. Soc. Relat. 2001, 26, 81–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lofland, L.H. The Public Realm: Exploring the City’s Quintessential Social Territory; Aldine de Gruytrer: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Borer, M.I. Being in the City: The Sociology of Urban Experiences. Sociol. Compass 2013, 7, 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COMPAC Luis Barragán, A Style Marked by Emotion. Available online: https://www.thedecorativesurfaces.com/en/luis-barragan/ (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Cheshmehzangi, A. Identity of Cities and City of Identities; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; The MIT Press: Cambridge, CA, USA; London, UK, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Silverstein, M.; Jacobson, M.; Fiksdahl-King, I.; Angel, S. A Pattern Language. Towns, Buildings, Construction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kaymaz, I. Urban landscapes and identity. In Advances in Landscape Architecture; Özyavuz, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmiero, M.; Piccardi, L. The Role of Emotional Landmarks on Topographical Memory. Front. Psychol. Sect. Cogn. 2017, 8, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samavati, S.; Veenhoven, R. Happiness in urban environments: What we know and don’t know yet. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2024, 39, 1649–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joye, Y.; Van den Berg, A. Is love for green in our genes? A critical analysis of evolutionary assumptions in restorative environments research. Urban For. Urban Green. 2011, 10, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia: The Human Bond with Other Species; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Steg, L.; Van den Berg, A.E.; De Groot, J.I.M. (Eds.) Environmental Psychology: An Introduction; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Evans, G.W.; Jamner, L.D.; Davis, D.S.; Gärling, T. Tracking restoration in natural and urban field settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. Meditation, restoration, and the management of mental fatigue. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 480–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 224–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, C.; Macfarlane, A.H.; Hikuroa, D.C.H.; McConchie, C.; Payne, M.; Holmes, H.; Mohi, R.; Hughes, M.W. Landscape change as a platform for environmental and social healing. Kōtuitui N. Z. J. Soc. Sci. Online 2022, 17, 352–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio Cisneros, I.I. Geología y Estado. Forma, Fondo y Territorios Vecinos de México; UANL: Monterrey, Mexico, 2018; 402p. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Cisneros, I.I. Uncomfortable environmental issues: Advised cases for medical geology in Monterrey, México. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Medical Geology, Monterrey, Mexico, 6–9 August 2023; p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- Crutzen, P.J.; Stoermer, E.F. The “Anthropocene”. Glob. Chang. Newsl. 2000, 41, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Crutzen, P.J. Geology of mankind. Nature 2002, 415, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, G. Ecopsychology in the symbio-cene. Ecopsychology 2014, 6, 58–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G. Exiting the Anthropocene and Entering the Symbiocene. 2015. Available online: https://glennaalbrecht.wordpress.com/2015/12/17/exiting-the-anthropocene-and-entering-the-symbiocene/ (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Albrecht, G.A. Negating solastalgia: An emotional revolution from the Anthropocene to the Symbiocene. Am. Imago 2020, 77, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G.A. Earth Emotions: New Words for a New World; Cornell University Press: Ithaka, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, G.; Sartore, G.M.; Connor, L.; Higginbotham, N.; Freeman, S.; Kelly, B.; Stain, H.; Tonna, A.; Pollard, G. Solastalgia: The distress caused by environmental change. Australasian Psychiatry 2007, 15 (Suppl. 1), S95–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SEDATU; CONAPO; INEGI. Metrópolis de Mexico 2020; Gobierno de México: México City, Mexico, 2024. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/sedatu/MM2020_06022024.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Lehner, B.; Verdin, K.; Jarvis, A. New global hydrography derived from spaceborne elevation data. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 2008, 89, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). Simulador de Flujos de Agua de Cuencas Hidrográficas (SIATL). 2020. Available online: https://antares.inegi.org.mx/analisis/red_hidro/siatl/# (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Secretaría de Medio Ambiente de Nuevo León. Listado de Árboles y Plantas Nativas del Estado de Nuevo León [PDF]. 2023. Available online: https://historico.nl.gob.mx/publicaciones/listado-de-arboles-y-plantas-nativas-del-estado-de-nuevo-leon (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- INEGI. Registro Vehicular en los 18 Municipios del Área Metropolitana de Monterrey; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Mexico City, Mexico, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional d’Estadística i Institut d’Estadística de Catalunya. 2022. Available online: https://www.idescat.cat/emex/?id=080193&lang=es (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- GHS Settlement Characteristics. 2018. Available online: https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/JRC_GHSL_P2023A_GHS_BUILT_C (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- CONEVAL Índice de Rezago Social 2020 a Nivel Nacional, Estatal, Municipal y Localidad. 2020. Available online: https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/IRS/Paginas/Indice_Rezago_Social_2020.aspx (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- CONAGUA Informe de Precipitaciones y Eventos Hidrometeorológicos en México. 2021. Comisión Nacional del Agua. Available online: https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/es/climatologia/pronostico-climatico/precipitacion-form (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Carpio, A.; Ponce-Lopez, R.; Lozano-García, D.F. Urban form, land use, and cover change and their impact on carbon emissions in the Monterrey Metropolitan area, Mexico. Urban Clim. 2021, 39, 100947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Agencia Aspacial Europea. Mapa de la Isla de Calor Urbano (UHI). Copernicus Open Access Hub. 2024. Available online: https://browser.dataspace.copernicus.eu (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Global Land Analysis & Discovery. Global Forest Loss due to Fire. 2022. Available online: https://glad.earthengine.app/view/global-forest-loss-due-to-fire (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Observatorio de la Calidad del Aire. Datos históricos sobre la calidad del aire en el Área Metropolitana de Monterrey; Instituto Nacional de Ecología y Cambio Climático: México City, Mexico, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- BCStats. 2023. Available online: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/data/statistics/people-population-community/population/pop_bc_annual_estimates.csv (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- INEGI. Censo Poblacional. 2020. Available online: www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/#resultados_generales (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Información Meteorológica y Climatológica. Comisión Nacional del Agua. 2023. Available online: https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/es/ (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Sirko, W.; Kashubin, S.; Ritter, M.; Annkah, A.; Bouchareb, Y.S.E.; Dauphin, Y.; Keysers, D.; Neumann, M.; Cisse, M.; Quinn, J.A. Continental-scale building detection from high resolution satellite imagery. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.12283. [Google Scholar]

- Open Buildings Dataset (Google Earth Engine). Available online: https://sites.research.google/gr/open-buildings/#open-buildings-download (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Debbage, N.; Marshall Shepherd, J. The urban heat island effect and city contiguity. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2015, 54, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balon, N.; Hrdalo, I.; Mrđa, A.; Kamenečki, M.; Tomić Reljić, D.; Pereković, P. Landscape urbanism—Retrospective on development, basic principles and application. Architecture 2023, 3, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Georgescu, M.; Wu, J. Impacts of landscape changes on local and regional climate: A systematic review. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 35, 1269–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Health Indicators of Sustainable Cities in the Context of the Rio+20 UN Conference on Sustainable Development; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Konijnendijk, C.C. Evidence-based guidelines for greener, healthier, more resilient neighborhoods: Introducing the 3–30–300 rule. J. For. Res. 2023, 34, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Urban Green Spaces: A Brief for Action; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Bonn, Germany, 2017; Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289052498 (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Zhou, W.; Wang, J.; Cadenasso, M.L. Effects of the spatial configuration of trees on urban heat mitigation: A comparative study. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 195, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, T. Transportation and public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2013, 34, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoub, D. The High Cost of Free Parking; Planner Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ’just green enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, A.M.; Dennis, L.Y.C.; Liu, C. A review on the generation, determination and mitigation of urban heat island. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 20, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamouris, M. Analyzing the heat island magnitude and characteristics in one hundred Asian and Australian cities and regions. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 512–513, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC (Center for Disease Control and Prevention). What Noises Cause Hearing Loss? 2020. Available online: www.cdc.gov/nceh/hearing_loss/what_noises_cause_hearing_loss.html (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Kheifets, L.; Swanson, J. Electric and magnetic fields and cancer: The epidemiological evidence. Environ. Res. 2020, 186, 109565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.B. The Management and Control of Urban Runoff Quality. Water Environ. J. 1989, 3, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, R.; Selsky, J.W.; Van der Heijden, K. Business Planning for Turbulent Times: New Methods for Applying Scenarios; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R.; Dassen, T. Thinking in Improbabilities. In Trends in Urban Design: Insights for the Future Urban Professional; Roggema, R., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Heijden, K. Scenarios: The Art of Strategic Conversation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, G.; Van der Heijden, K.; Burt, G.; Bradfield, R.; Cairns, G. Scenario planning interventions in organizations: An analysis of the causes of success and failure. Futures 2008, 40, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, P.; Martinez Perez, A.; Roggema, R.; Williams, L. (Eds.) Repurposing the Green Belt in the 21st Century; UCL Press: London, UK, 2020; 168p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggema, R. From Your Balcony to the World: An Ecocathedric Approach to Regenerating Urban Landscapes; Keynote Forum on Urban Innovation and Sustainability: San Pedro Garza Garcia, Mexico, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R. (Ed.) Nature-Driven Urbanism; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R. From Nature-based to Nature-driven: Landscape first for the design of Moeder Zernike. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggema, R.; Monti, S. Nature driven planning for the FEW-Nexus in Western Sydney. In TransFEWmation. Towards Design-Led Food-Energy-Water Systems for Future Urbanization; Roggema, R., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 59–94. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R.; Keeffe, G.; Tillie, N. Nature-based urbanization: Scan opportunities, determine directions and create inspiring ecologies. Land 2021, 10, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggema, R.; Tillie, N.; Hollanders, M. Designing the adaptive landscape: Leapfrogging stacked vulnerabilities. Land 2021, 10, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijhuis, S. Landscape-Based Urbanism: Cultivating Urban Landscapes Through Design. In Design for Regenerative Cities and Landscapes: Rebalancing Human Impact and Natural Environment; Roggema, R., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 249–277. [Google Scholar]

- Nijhuis, S.; Xiong, L.; Cannatella, D. Towards a Landscape-based Regional Design Approach for Adaptive Transformation in Urbanizing Deltas. Res. Urban. Ser. 2022, 6, 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-Melo, G. La Planificación de una Metrópoli: Por un Urbanismo Integral, Humanista y Sustentable, Tomo I; UANL: Monterrey, Mexico, 2014; 272p. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Cisneros, I.I. Preliminary cartographic diagnosis for environmental and geological compensations in the municipality of Guadalupe, Nuevo León. Ing. Investig. Tecnol. 2023, XXIV, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Wel, P. Hydrate Monterrey: A Spatial Strategy to Implement Green and Blue Infrastructure in Order to Tackle Droughts and Heat Stress in Monterrey, Mexico. Master’s Thesis, Architecture and the Built Environment, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Petit-Boix, A.; Apul, D. From cascade to bottom-up ecosystem services model: How does social cohesion emerge from urban agriculture? Sustainability 2018, 10, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefani, M.C.; Orsini, F.; Magrefi, F.; Sanyé-Mengual, E.; Pennisi, G.; Michelon, N.; Bazzocchi, G.; Gianquinto, G. Toward the Creation of Urban Foodscapes: Case Studies of Successful Urban Agriculture Projects for Income Generation, Food Security, and Social Cohesion. In Urban Horticulture. Sustainable Development and Biodiversity; Nandwani, D., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Habitat. Greener Cities Partnership (UN-Habitat and UN Environment. 2016. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/greener-cities-partnership (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- WEF. Nature Positive: Guidelines for the Transition in Cities, Insight Report. In collaboration with Oliver Wyman. 2024. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Nature_Positive_Guidelines_for_the_Transition_in_Cities_2024.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Trees of the World. Available online: https://treecitiesoftheworld.org (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Yu, K. The sponge city: Planning, Design and Political Design. In Architecture and the Climate Emergency—Everything Needs to Change; Pelsmakers, S., Newman, N., Eds.; RIBA Publishing: London, UK, 2021; pp. 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- C40 Cities and ARUP. Urban Rewilding. The Value and co-Benefits of Nature in Urban Spaces. 2023. Available online: https://c40.my.salesforce.com/sfc/p/#36000001Enhz/a/Hp000000haJF/GiSUGhj3_IYcI_fm4n08xW8Vap411v2vVsjom_rGzCw (accessed on 21 October 2024).

| Map | Data Source |

|---|---|

| Rio Bravo basin | Lehner et al., 2008 [91] |

| Monterrey’s subbasins | INEGI 2020 [92] |

| Ecoregions | Secretaría de Medio Ambiente de Nuevo León 2023 [93] |

| Land cover | NALCMS |

| Green cover, city comparison | INEGI (2023) [94], BC Stats (2023) [103], Instituto Nacional d’Estadística I Institut d’Estadística de Catalunya (2022) [95], GHS Settlement Characteristics (2018) [96]. |

| Percentage natural area | NALCMS 2020, GHSL 2018 [96] |

| Proximity to green spaces and accessibility by vulnerable groups | LANDSAT 2019, Population and Housing Census [104], INEGI, 2020 [104], Open Street Maps, CONEVAL 2020 [97] |

| Heat index | URSA, BID |

| Rainfall | CONAGUA [98], Servicio Meteorológico Nacional, 2023 [105] |

| Urban growth | Secretaria de Desarrollo Sustentable de Nuevo León, Carpio et al., 2021 [99], GHSL and Consejo Nuevo León |

| Urban density | Secretaría de Desarrollo Sustentable de Nuevo León (2018), Carpio et al. (2021) [99], GHSL and Consejo Nuevo León (2023). |

| Urban heat islands and wildfires | Copernicus Agencia Espacial Europea (2024) [100]; Global land analysis and discovery (2022) [101] |

| Air quality | The Observatory of Air Quality in Metropolitan Monterrey OCCAMM 2024 [102] |

| Verb | Translation | Etymology | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAIN | |||

| Terraphthora | Earth-destroyer | terra = earth; phthora = to destroy, destroy, ruin | Earth destroyers will be increasingly held accountable, both by the public and politicians. |

| Tierratrauma | Earth trauma | tierra = region/zone; trauma = wound | An ‘acute Earth-based existential trauma in the present’. |

| Solastalgia | Consolation | solari = to comfort; nostalgia = longing for past times | A ‘pain or distress caused by the loss -or lack of- solace and the sense of desolation connected to the present state of one’s home and territory’. |

| Terrafuria | Climate rage | terra = earth; furia = anger, rage | ‘The extreme anger unleashed within those who can see the self-destructive tendencies in the current forms of industrial-technological society and feel they must protest and act to change its direction’. |

| HEAL | |||

| Sumbiofact | Built-with-nature | sumbio = from the close cooperation between two or more different biological entities; factum = operation, creation, result of action/deed | Fabricated by human/nature interaction. As distinct from ‘artifact’, an object made artificially by a human being. |

| Symbiocene | symbiosis = living together; kainos = new | The Symbiocene will be in evidence when there is no discernible impact of human activity on the planet other than the temporary remains of their teeth and bones. Everything that humans do will be integrated within the support systems of all life and will leave no trace’. | |

| LOVE | |||

| Endomophilia | Own-place-love | endemos = native, at home, born and raised in, among us; philia = love for | ‘The particular love of that which is locally and regionally distinctive as felt by the people of that place’. |

| Eutierria | Planet connection | eu = good; terra = earth; tierra = region/zone | ‘A positive and good feeling of oneness with the Earth and its life forces where the boundaries between self and the rest of nature are obliterated and a deep sense of peace and connectedness pervades consciousness’. |

| Psychoterratic | Earth soul movements | psyche = the human soul or spirit; terratic = relating to the earth | ‘Emotions related to (positively and negatively) perceived and felt states of the Earth’. |

| Terranascia | Soil enricher | terra = earth; nascia = to be born | ‘Green Gold’, ’Earth creator’ |

| Map | Data Sources |

|---|---|

| Quarries and constructions in natural reserves | NPA, Open buildings dataset (Google Earth Engine), Sirko et al., 2021 [106] |

| Large roads (more than six lanes each way) | INEGI [104] |

| XL and L buildings | Open buildings dataset (Google Earth Engine, https://sites.research.google/gr/open-buildings/#open-buildings-download, Accessed on 9 October 2024) [107]. Sirko et al., 2021 [106] |

| Heat islands | Debbage and Marshall Shepherd, 2015 [108] |

| Railways and above metro system | INEGI, PRIMUS 2019 [92] |

| Energy infrastructure/air quality | Secretaria de Desarrollo Sustentable de Nuevo Leon, 2018. |

| Hydrological obstructions | INEGI 2020 [92], Open buildings dataset [107] |

| Landscape transformation | Balon et al., 2023 [109]; Cao et al., 2020 [110] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roggema, R.; Rubio Cisneros, I.I.; Junco López, R.; Ramirez Leal, P.; Ramirez Suarez, M.; Ortiz Díaz, M. Loving and Healing a Hurt City: Planning a Green Monterrey Metropolitan Area. Land 2025, 14, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14010164

Roggema R, Rubio Cisneros II, Junco López R, Ramirez Leal P, Ramirez Suarez M, Ortiz Díaz M. Loving and Healing a Hurt City: Planning a Green Monterrey Metropolitan Area. Land. 2025; 14(1):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14010164

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoggema, Rob, Igor Ishi Rubio Cisneros, Rodrigo Junco López, Paulina Ramirez Leal, Marina Ramirez Suarez, and Miguel Ortiz Díaz. 2025. "Loving and Healing a Hurt City: Planning a Green Monterrey Metropolitan Area" Land 14, no. 1: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14010164

APA StyleRoggema, R., Rubio Cisneros, I. I., Junco López, R., Ramirez Leal, P., Ramirez Suarez, M., & Ortiz Díaz, M. (2025). Loving and Healing a Hurt City: Planning a Green Monterrey Metropolitan Area. Land, 14(1), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14010164