1. Introduction

Tropical coastal ecosystems are globally recognized for their rich biodiversity and high productivity [

1]. Among these ecosystems, coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangroves play pivotal roles in maintaining oceanic health and balance [

1]. Mangroves are intertidal ecosystems that provide vital biodiversity support and coastal protection worldwide [

2]. They thrive at the interface between terrestrial and marine environments, forming unique habitats that stabilize coastal areas. Beyond biodiversity, mangroves deliver essential ecosystem services, including flood protection, water storage, and habitat preservation [

3,

4]. They are highly productive environments, providing habitats for 75% of commercial fishery species during various life stages [

5,

6]. For example, Indonesia is an important habitat for its diversity of fish and invertebrate species, the abundance of which supports the livelihoods of the country’s coastal communities [

7]. In mangroves, factors such as soil and water are essential because they play a fundamental role in the natural distribution and biological activity of mangroves [

8]. Also, they create physical and chemical conditions that affect abiotic factors such as soil anaerobiosis, organic matter accumulation, and nutrient availability, but also biotic such as species richness and composition. Thus, they determine the species that remain in wetlands and their primary productivity [

9]. In addition to these ecological functions, mangroves have recently been recognized in the fight against climate change [

10] because they capture and store blue carbon, help protect coasts, maintain marine biodiversity, and support the sustainability of local communities [

11]. For this reason, preservation and restoration are essential in the fight against climate change and in adapting to its impacts.

The degradation and loss of species diversity in these ecosystems are exacerbated by challenges such as habitat loss, which can significantly diminish ecosystem services [

12]. Activities such as mangrove cutting for charcoal production, building materials, fuelwood, and fishing further contribute to these threats [

13]. While these activities have contributed to economic and social development, they have also pressured mangrove ecosystems significantly, compromising their biodiversity, structure, and functioning. In recent decades, mangroves have faced increasing pressures due to various anthropogenic activities, leading to significant degradation and raising concerns about their conservation and ecological functioning. The expansion of the human population and the consequent increase in demand for natural resources has led to the intensive exploitation of mangrove areas for purposes such as agriculture, aquaculture, urbanization, mining, and industry [

14]. The clearing of mangroves for timber, charcoal, and space for human activities has led to ecosystem fragmentation and degradation, which can negatively affect biodiversity and the ability of mangroves to provide essential ecosystem services [

15]. In addition, advancing agriculture and aquaculture often involves introducing chemicals and nutrients into nearby water bodies, affecting habitat quality and water pollution [

16,

17]. Overexploitation of fishery resources and soil degradation have also directly impacted the health and resilience of mangrove ecosystems [

17].

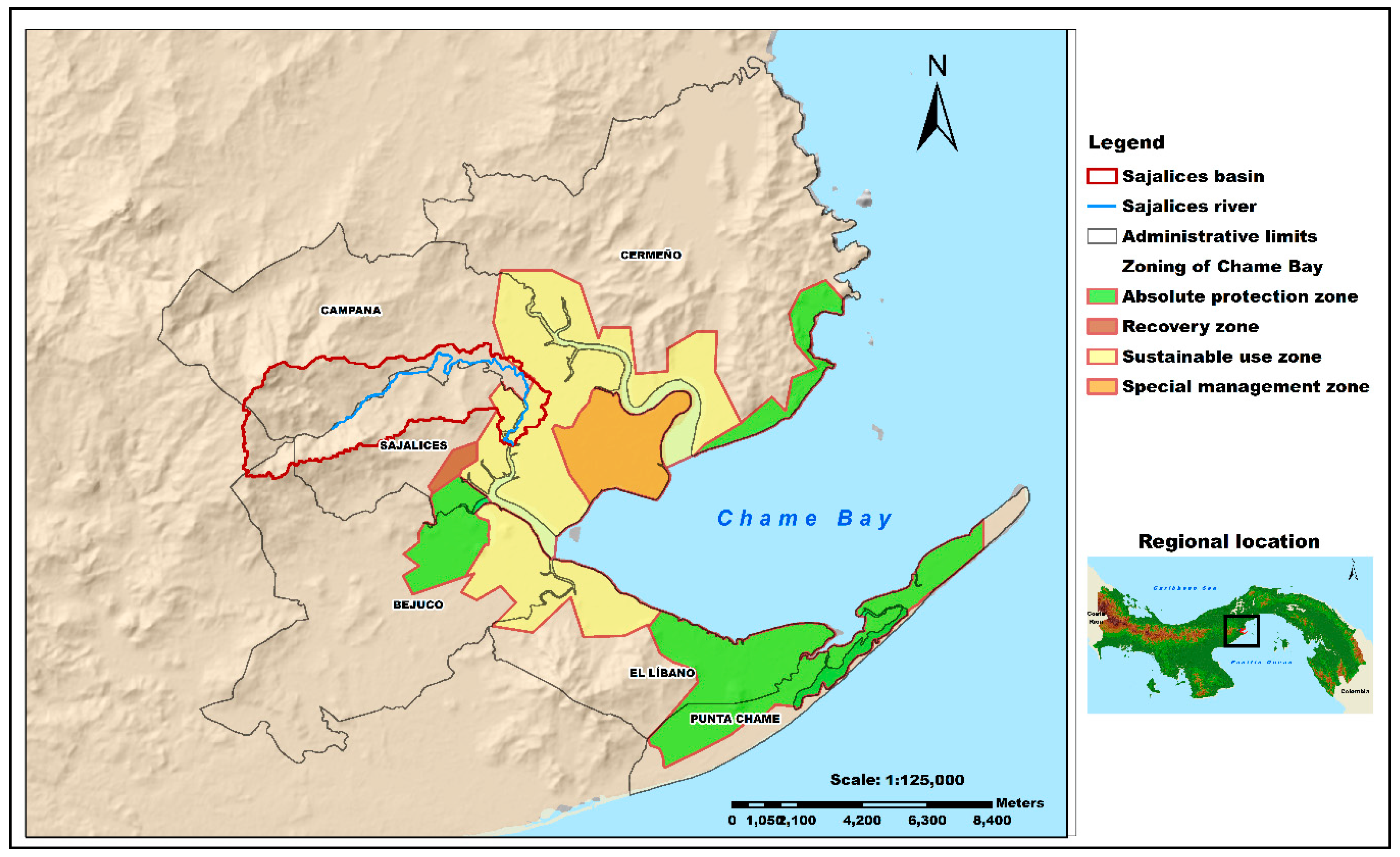

According to the Environmental Information Directorate (DIA) of the Ministry of Environment, Panama has 177,293 ha of mangroves, of which 164,124 ha are in the Pacific and 13,169 ha in the Caribbean: representing 2.4% of the country’s forest cover. Panama’s intertidal mangrove is home to the most significant number of mangrove species in the Americas [

1]; 12 species of the 65 species identified worldwide have been reported [

18]. The mangroves of Chame Bay are home to many marine and terrestrial species. They are part of the tropical and subtropical dry forest ecoregion, which is in a critical state of conservation [

19]. One of the most notable impacts of anthropogenic activities on mangroves is habitat loss due to converting mangrove areas into agricultural expansion, the establishment of farms, shrimp farms, salt ponds, or urban land [

20].

According to data from the Environmental Information Directorate of the Ministry of Environment, Chame Bay experienced a worrying loss of 6% of mangrove forest from illegal logging between 2012 and 2019. The National Directorate of Protected Areas and Biodiversity of the Ministry of Environment highlights that these mangroves face significant threats derived from anthropogenic activities, such as mangrove forest fragmentation, overuse, and excessive exploitation for mangrove charcoal production and mangrove stick extraction resulting in biodiversity loss. Exploitation for charcoal production contributes to the loss of this vital ecosystem and generates greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to climate change. In addition, residents are in a vulnerable position due to exposure to the smoke generated by the ovens used in this extractive activity [

21].

Anthropogenic actions have become increasingly important in defining the dynamics and trajectory of mangrove ecosystem regeneration worldwide [

13]. For example, in Indonesia coal mining represents the main anthropogenic activity causing disturbance to mangrove ecosystems [

22]. Additionally, the extent of mangroves continues to decrease at an alarming rate due to land use change, and this phenomenon is aggravated mainly by the expansion of tourism developments [

16,

23]. These developments often promote the construction of hotel infrastructures that are not ecologically sustainable [

17]. This uncontrolled growth in areas close to mangroves seriously threatens the integrity of these fragile ecosystems [

17]. This situation reflects a lack of effective regulation and control that jeopardizes the conservation of mangroves, despite their vital importance in climate change mitigation and their essential role in coastal protection and the maintenance of marine biodiversity. The urgent need to address these problems and promote sustainable development practices in mangrove areas is undeniable if we are to preserve these crucial ecosystems for future generations [

20]. Due to the loss and deterioration of mangroves, it is essential to implement not only conservation measures to preserve the mangroves that are still in good condition, but also restoration actions that enable the recovery of critical elements, such as their original structure, functions, and dynamics. Therefore, mangrove restoration is fundamental in conserving these valuable ecosystems and mitigating climate change’s impact.

Ecological restoration goes beyond just recovering the natural aspects of the ecosystem [

21] and it is now recognized that restoration must encompass a broad spectrum of practices that not only include aspects of the natural sciences, but also dimensions of the human sciences, economic factors, and relevant cultural dimensions [

24]. This perspective implies that successful restoration requires a holistic view considering historical, social, cultural, political, aesthetic, economic, and moral attributes [

25]. In addition, it must consider how restoration efforts relate to patterns of resource use and the values and activities that are significant to the society in question [

26]. Also, the importance of community involvement, with a sound scientific understanding of the ecosystem’s preconditions, is emphasized [

27]. Ultimately, it is recognized that the relationship between natural ecosystems and human influence is diverse and variable [

28]. The diversity of ecosystems is evident, some have been profoundly transformed by human activity [

29], while others have evolved due to traditional practices that resemble natural disturbances [

30]. This nuanced understanding of the relationship between humans and nature is critical to the planning and implementation of restoration projects that are effective and culturally sensitive [

31]. The adaptation of restoration strategies to the particularities of each ecosystem and the historical and cultural interaction is therefore fundamental to achieving positive and lasting results [

32].

In order to address the problems posed by the degradation of mangroves in Chame Bay and the importance of their restoration, this research has the following objectives: to assess the level of knowledge and perception of local communities and users about the ecological relevance of mangroves and the ecosystem services they provide; to analyse the current participation of farmers and charcoal producers in mangrove restoration actions and their willingness to get involved in future ecological regeneration processes; and to examine the relationship between socio-demographic variables, such as age, educational level and professional sector, with the perception, involvement and willingness to participate in restoration.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Respondents

The respondents’ profile reveals a balanced distribution in terms of gender, with 55% of respondents being female and 44.7% male, while a minimal percentage of 0.3% chose not to answer. A wide diversity in terms of age ranges is observed, reflecting the inclusion of different age groups in the study. For example, 22.3% of respondents fall in the 18–30 age range, representing youth and young adults in the sample. Likewise, 30.3% were between the ages of 31 and 50, indicating the presence of people in the intermediate stage of life. On the other hand, 33.3% belong to the 51 to 71 age group, reflecting the significant presence of older individuals in the sample. In addition, 14% of the respondents are over 71 years of age, highlighting the inclusion of elderly people in the study. Regarding the educational background of the respondents, the sample reflects a diversity in terms of education. It is observed that 0.7% of the respondents have postgraduate studies, indicating a limited presence of individuals with a high level of specialization, 14.7% have a bachelor’s degree, indicating individuals who have completed university studies, 15.3% have technical training, reflecting the presence of individuals with specific skills and knowledge, 41% have completed secondary education, indicating the largest representation of individuals with an intermediate educational level, and 28.3% of the respondents have primary education, highlighting a basic educational level in the sample.

The result of the data analysis indicates differences by gender for the earnings. Among the total number of men surveyed, 56.53% identified themselves as salaried employees, while 43.47% stated that they were self-employed. On the other hand, 59.06% of the women surveyed indicated that they were salaried, and 40.94% reported being self-employed. The analysis of the household income of the respondents reveals a wide variety of economic situations within the sample, reflecting the socioeconomic diversity present in the population studied. Forty-six percent of respondents report a household income of less than $500 per month, suggesting the significant presence of households with limited economic income. On the other hand, 39.7% of respondents have incomes between $600 and $800 per month, indicating a considerable proportion of households with moderate incomes, considering that the minimum wage in Panama is $600. In addition, 14.3% of respondents report incomes above $801 per month, reflecting the economic diversity of the community.

Thirty-eight percent of respondents indicated that the mangrove represents regulating services (water cycle, erosion control, soil fertility maintenance, water regulation, sanitation, and pollination), followed by 32% for provisioning services (food, water: agriculture and consumption, energy resources: firewood, raw materials, genetic resources), and 26% of respondents who did not answer. In the case of cultural services (education, cultural diversity, aesthetic value, belonging, scientific knowledge, recreational services, and ecotourism) and support services (photosynthesis, species habitat, conservation of genetic diversity, nutrient cycling, primary production), 2% of respondents consider these services to be what the mangrove represents.

3.2. Ecosystem Service Provisioning in Relation to Economic Activity and Interaction with the Mangrove

The ecosystem service of provisioning plays a crucial role in the economic activity of the communities that interact with mangroves. In the case of the primary sector, which includes agricultural and fishing activities, accounting for 38% of respondents, mangroves provide essential resources such as fish, shellfish, and timber, which are fundamental for subsistence and local commerce. This sector relies heavily on the health of the mangroves to maintain their productivity and ensure the livelihoods of the families that depend on these natural resources. On the other hand, the tertiary sector, which comprises 58% of respondents, benefits indirectly from mangroves through service and commerce-related activities. To a lesser extent, the secondary sector, with 2% of respondents, also interacts with mangroves through the transformation of products derived from these ecosystems, such as the production of handicrafts and other manufactured goods. Finally, the remaining 2%, classified as “other”, includes various activities that, although not specified, may be related to the sustainable use and conservation of mangroves, highlighting the multifaceted importance of these ecosystems for the local economy and the provision of essential resources.

3.3. Ecosystem Service Regulation and Mangrove Conservation

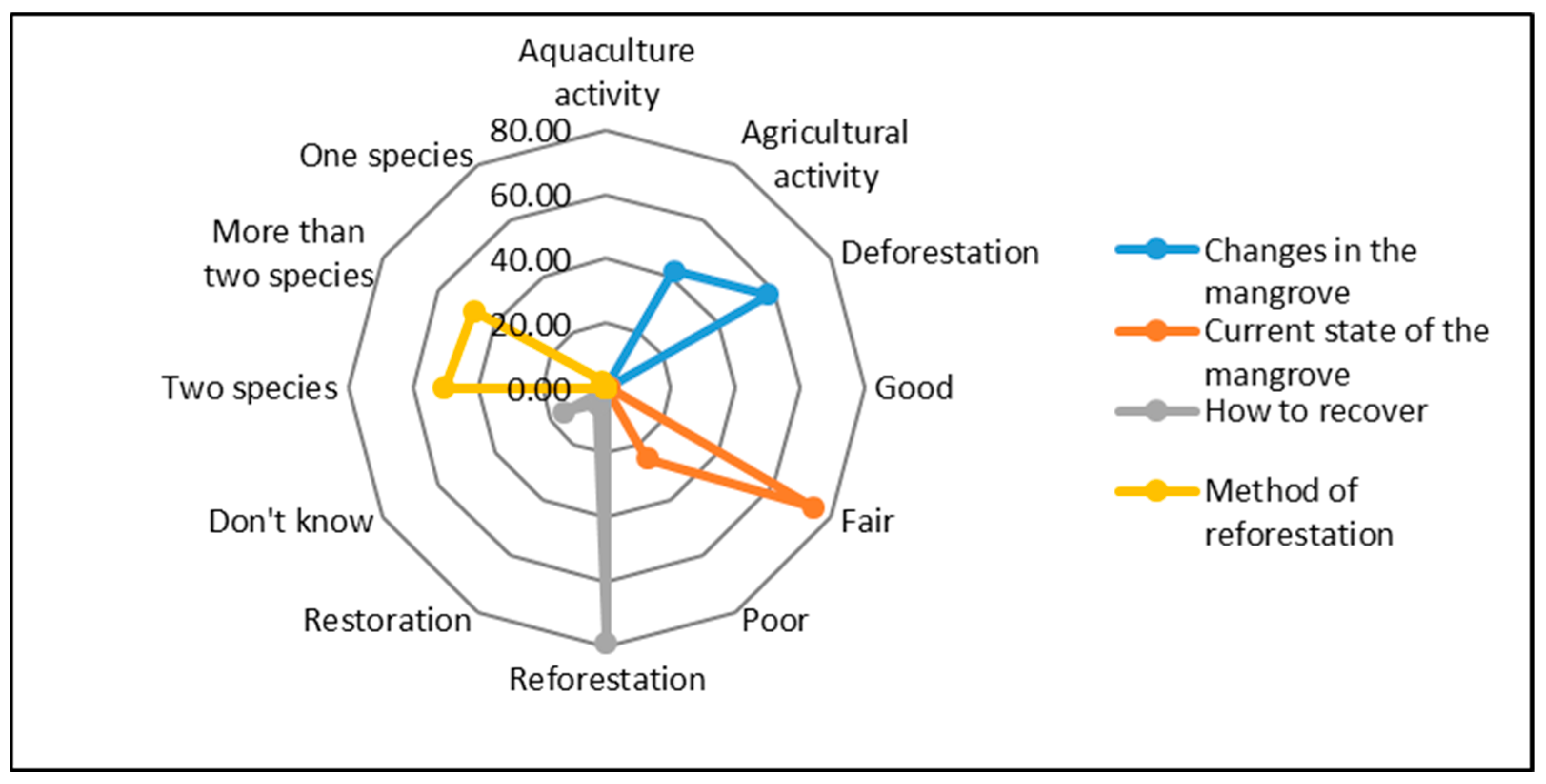

The results highlight that many respondents (57.87%) attribute changes in the mangrove forest mainly to deforestation, underscoring concern about the loss of forest cover in these ecosystems. In addition, agricultural activity is also perceived as another factor, mentioned by 41.87% of respondents (

Figure 2). Regarding the perception of the current state of the mangrove, many respondents (74%) consider it to be in fair condition, while a quarter of respondents (25%) perceive it to be in poor condition. Only a small percentage (1%) consider the mangrove to be in good condition, suggesting widespread concern for the health of these ecosystems. Many respondents (79.21%) suggest that reforestation is the best way to recover the mangrove, highlighting the importance of taking restoration actions. However, only 15.05% of respondents advocate plantation, indicating the possibility that they may consider restoration approaches other than mangrove planting. In addition, a small percentage (5.73%) do not have a clear opinion on how to restore the mangrove (

Figure 2).

In relation to restoration methods, most respondents (69%) believe that mangrove restoration should be carried out using assisted regeneration, underscoring the acceptance of this technique among the community, however, 30% of respondents believe that both methods (assisted and natural) should be used. Only 1% advocate natural regeneration as the primary approach (

Figure 2). Regarding preference for the number of mangrove species in assisted regeneration efforts, half of the respondents (50%) felt that two mangrove species should be used. Forty-eight percent prefer to use more than two species. Only a small percentage (2%) believe that a single species is sufficient for regeneration (

Figure 2). Respondents show a varied knowledge of mangrove species, with

Rhizophora mangle,

Laguncularia racemosa, and

Pelliciera rhizophorae as the best known.

3.4. Ecosystem Support Service and User Participation

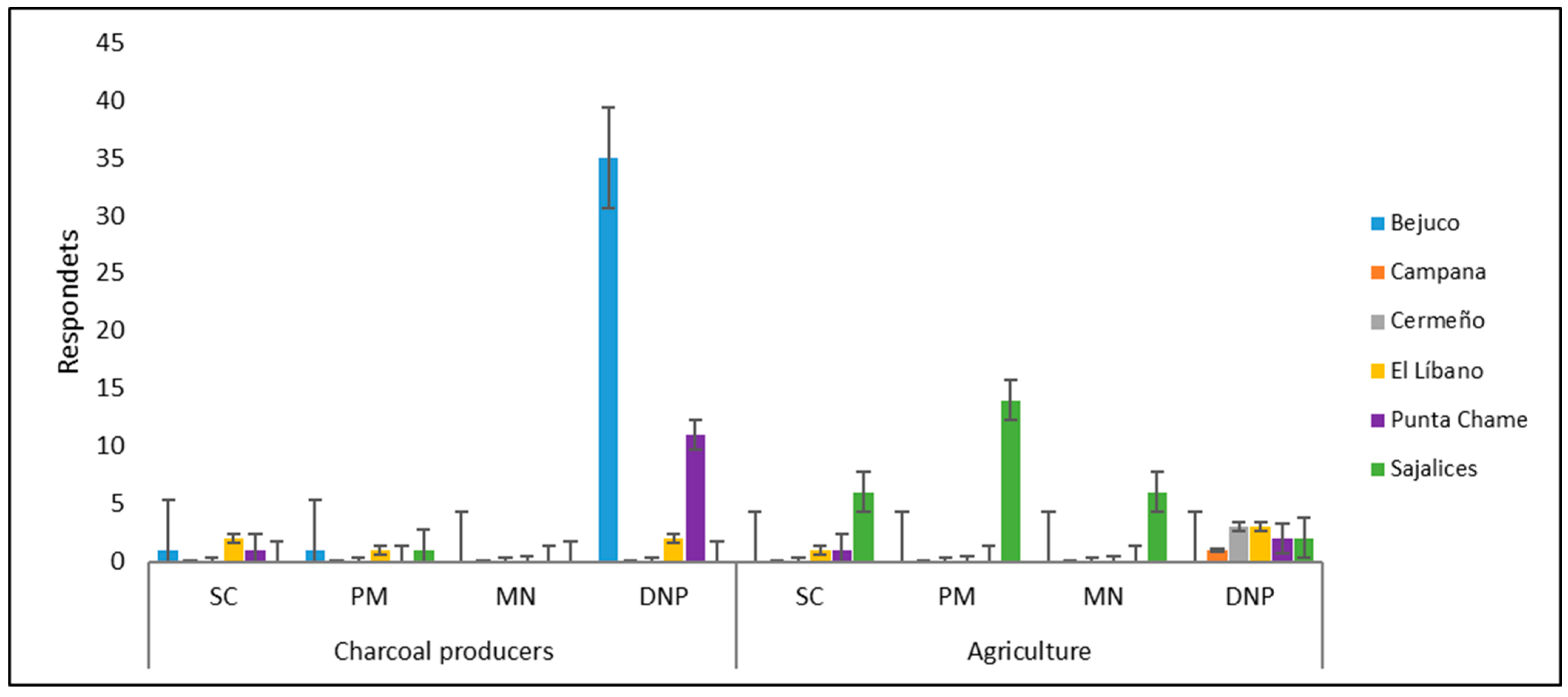

Among the charcoal producers, 15% have already participated in restoration actions. Of the group that participated in restoration, 38.78% were involved in mangrove seed collection, 44.90% in mangrove planting, and 16.33% in nursery propagation. 54.90% of the farmers surveyed have participated in restoration actions. 35.71% participated in mangrove seed collection, 53.57% in mangrove planting, and 10.71% in nursery propagation.

Figure 3 shows the participation of respondents in various activities related to mangrove conservation and restoration, categorized into townships. In the case of charcoal producers, respondents from Bejuco showed a notably higher tendency to not participate, while the other localities such as Campana, Cermeño, El Líbano, Punta Chame, and Sajalices have considerably lower participation in all activities. As for farmers, respondents from Sajalices stood out for their participation in mangrove planting, being the group with the highest participation in conservation activities. The other activities and localities showed more balanced participation, but in general, the option of “not participating” remains predominant in several communities, with the exception of Sajalices in the nursery and mangrove planting activities. Users’ perceptions of mangrove restoration do not seem to differ according to educational level and social interaction patterns.

Since charcoal production is the economic activity with the greatest impact on the mangrove, the results indicate that 77.27% of the agricultural sector expressed interest in participating in these activities, while 22.73% expressed no desire to get involved. On the other hand, in the case of charcoal producers, 59.46% showed a willingness to participate, while 25.68% showed no interest (

Figure 4). The error bars associated with the graph indicate variability in responses, being more pronounced among farmers compared to charcoal producers. However, when comparing the perception of participation in restoration processes between the two groups, no significant differences were observed, suggesting a similar general trend in terms of willingness to get involved in mangrove restoration.

The results of the chi-square statistical analysis (

Table 2) reveal that farmers have a significantly higher participation in mangrove restoration actions. This result suggests that farmers are more willing or involved in activities that promote ecosystem regeneration. In addition, charcoal producers also show significant participation in these restoration actions, although in a smaller proportion. However, when directly comparing participation between farmers and charcoal producers, no significant differences were found, indicating that both groups are equally willing to participate in restoration, although the motives or magnitude of their participation may vary.

4. Discussion

The results of the surveys applied to the users and inhabitants of the mangrove forest of Chame Bay offer detailed insight into their knowledge, perceptions, and experiences about this valuable ecosystem. These results provide an in-depth understanding of the social, economic, and environmental dynamics and offer useful information to guide future management and conservation strategies in the protected area. Also, the analysis of the data obtained revealed several significant aspects related to the salary situation by gender, the respondents’ main economic activity, and their perception of the services provided by the mangroves.

Regarding gender and age status profile, the results indicate that a higher percentage of female respondents identified themselves as wage earners compared to men. This trend could suggest a greater presence of women in roles that have traditionally been considered salaried jobs. This could result from changes in job opportunities and greater inclusion of females in previously male-dominated sectors [

37]. In terms of gender and employment, it has been identified that in several regions women have a greater presence in salaried jobs, reflecting both advances in inclusion and possible wage inequalities. In a similar survey conducted about mangrove governance in southeastern Cuba, 46.2% of respondents were women, with a considerable number of them participating in the public sector [

38]. However, it is important to consider the possibility that this greater presence in salaried jobs may also be related to the persistence of gender-based wage inequalities, where females could be more likely to occupy lower-paid positions [

39,

40]. On the other hand, the results also indicate that a higher percentage of male respondents identified themselves as self-employed than women. This trend could be related to the notion of independence and autonomy that is often associated with self-employment [

41]. Some men may seek the flexibility and control offered by self-employment as a response to traditional expectations of being the main economic providers in the household. In addition, this difference could be related to inequalities in work opportunities, as some women may feel limited in their access to self-employment roles due to factors such as lack of resources or unequal access to networks and opportunities.

In Chame Bay, the predominant economic activities in the studied region are included in the tertiary sector, which is oriented towards services and commerce. This is influenced by tourism and recreational activities of the local population [

42]. The primary sector also maintains a significant presence, highlighting the importance of agricultural and fishing activities in the region’s economy [

34]. These results provide a deeper understanding of the distribution of economic activities among the respondents and their potential impact on the community and the region in general. The finding that the tertiary sector was identified as the one concentrating the majority of the economic activities of respondents is consistent with the global trend of transition towards service-based economies in many regions [

43]. The strong presence of the tertiary sector indicates increasing urbanization, as well as the importance of trade and service activities for the local economy. Furthermore, this result can be an indicator of economic diversification and adaptation to changing market demands.

On the other hand, respondents who indicated that they were engaged in the primary sector (agricultural, charcoal, and fishing activities) indicated a significant proportion of individuals who depend directly on natural resources for their livelihoods. This reflects the continued importance of primary activities in employment generation and food supply. However, it may also point to challenges related to sustainability and natural resource management in the context of increasing pressure on the environment [

44].

The most limited group of economic activities is in the secondary sector (industrial and manufacturing), which may indicate less industrialization in the studied region. This may have various economic implications, from a lack of industrial infrastructure to possible limitations in the availability of resources and skilled labor for manufacturing. Although this proportion is low, its importance should not be underestimated, as the secondary sector usually triggers broader economic growth processes.

The “other” category indicates activities not specified in the survey. This category may represent a diversity of occupations and economic activities that do not fit into the predefined categories. The existence of this category underscores the complexity and diversity of economic activities in the region, which may reflect adaptation and innovation in response to changing needs and emerging opportunities.

The results reveal important findings that shed light on the community’s perception of mangrove ecosystem degradation and restoration. One of the most prominent aspects is the attribution of deforestation as the main factor of change in the mangrove. This result reflects widespread concern about the loss of forest cover in mangroves and underscores the importance of addressing deforestation as a critical threat to the integrity of these ecosystems [

45]. The perception of agricultural activity as another relevant factor suggests the need to consider conservation strategies that address agricultural practices in these areas.

The community’s assessment of the state of the mangrove shows divided opinions: while the majority considers it to be in fair condition, a significant portion perceives it to be in poor condition. This discrepancy could be due to variations in knowledge, experience, or economic dependence on the mangrove, as well as the environmental awareness of the respondents. This perception reflects widespread concern for the health and stability of mangroves, indicating the need to implement effective measures to ensure their long-term conservation [

46].

This study reveals that the majority of respondents prefer reforestation as a method of mangrove recovery, indicating strong support for active restoration efforts to revive these crucial ecosystems. This preference is supported by a general understanding that mangrove planting can be an effective strategy for revitalizing these ecosystems [

47]. However, it is important to recognize that this preference may be influenced by a lack of knowledge about alternative methods of mangrove restoration. The implementation of other techniques, such as hydrological restoration, water quality management, or coastal wetland conservation, could offer complementary or even more effective solutions in certain contexts [

48]. However, a group of respondents show a preference for alternative methods of regeneration, suggesting that they consider options other than simply planting mangroves. This highlights the importance of exploring more diverse restoration approaches tailored to the specific conditions of each mangrove area.

In terms of restoration methods, the acceptance of assisted regeneration of respondents is an indicator that the community is willing to support approaches that involve active intervention in mangrove restoration. For example, one of the key strategies that has been implemented in the region is mangrove restoration through assisted regeneration, where they have carried out mangrove plantations in degraded or deforested areas [

49].

The respondents who advocate the use of both methods (assisted and natural) demonstrate a deep understanding of the need to balance natural and assisted approaches. Through integration of natural methods (such as natural regeneration and conservation of existing habitats) with assisted approaches (such as reforestation and rehabilitation of degraded ecosystems), regeneration efforts can be successful and promote long-term mangrove recovery. The preference for the use of more than two mangrove species in assisted regeneration efforts highlights the importance of species diversity in the mangrove. This suggests that the community values the diversity of the ecosystem and understands the relevance of multi-species regeneration to strengthen the resilience of the Chame Bay mangroves [

50].

Mangroves provide a variety of ecosystem services that contribute to the sustainable development of coastal communities [

51]. Mangroves provide a wide range of ecosystem services that are fundamental to the sustainable development of coastal communities, including Chame Bay. Public perception of these services, especially regulating services such as carbon sequestration, prevention of natural disasters, and regulation of water flows, plays a key role in the effectiveness of conservation efforts [

52]. The majority of respondents in similar studies recognize the importance of mangroves for coastal protection and their ability to support local economic activities such as fishing. This coincides with the results obtained in Chame Bay, where reforestation is seen as the most viable method to restore degraded mangroves. Coastal users and communities perceive mangroves as vital to their well-being and livelihoods and recognize the ability of mangroves to provide a range of benefits, such as coastal and erosion protection, provision of habitats for marine species, and contribution to food security through fisheries [

53]. However, it is also crucial to promote greater knowledge about alternative restoration methods, such as hydrological restoration and water quality management, which may offer more comprehensive and sustainable solutions in certain contexts [

38]. Also, environmentalists understand the critical role of mangroves in mitigating climate change by acting as carbon sinks and in improving water quality by filtering sediments and pollutants [

11].

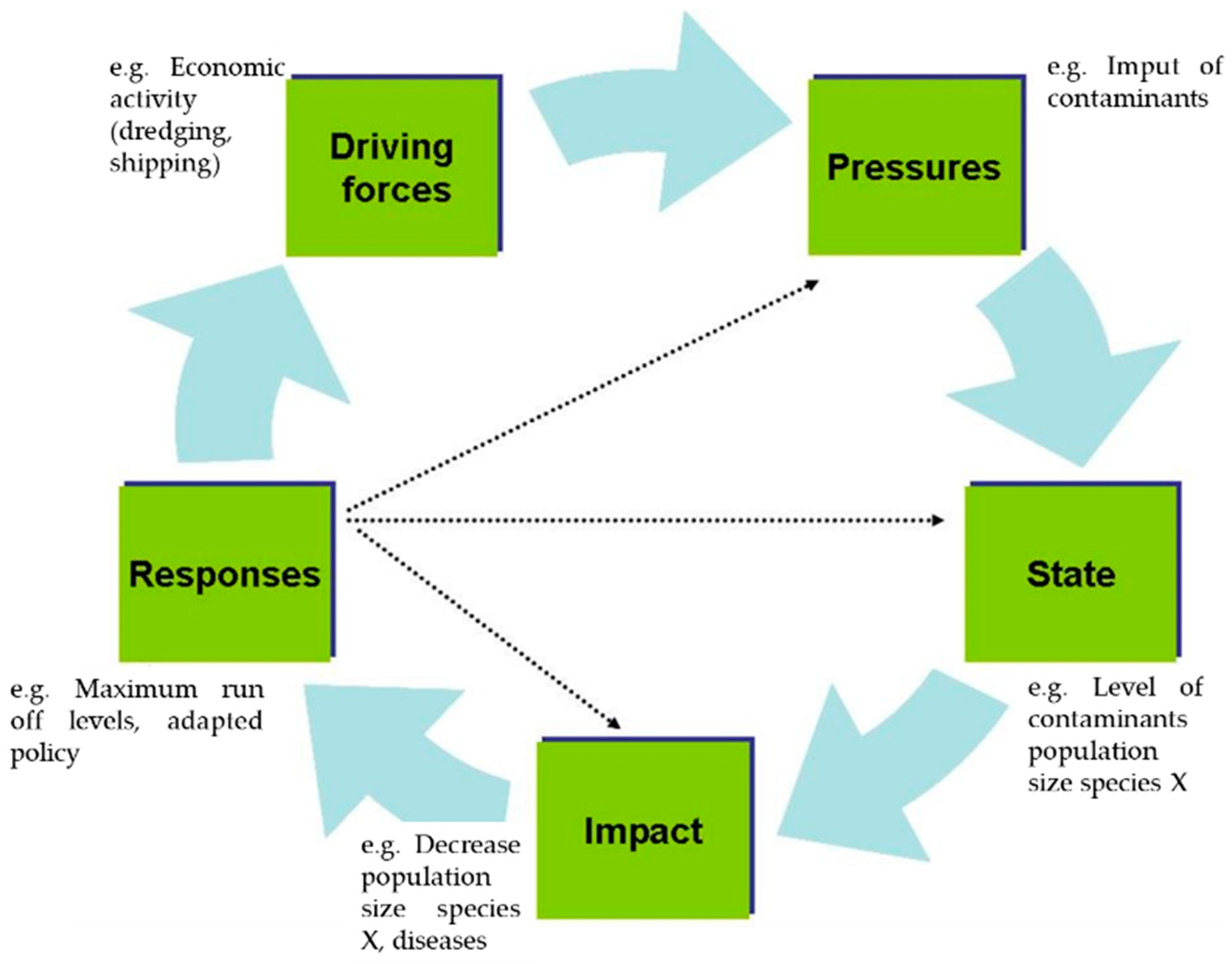

The analysis of participation in restoration actions highlights a positive attitude of both charcoal burners and farmers towards involvement in regeneration processes. This is important, as it suggests a genuine interest in mangrove conservation and regeneration on the part of key stakeholders involved in economic activities related to the exploitation of these ecosystems. This behavior can be interpreted under the Driving Forces-Pressure-State-Impact-Responses (DPSIR) framework, as shown in

Figure 5. The driving forces, such as the demand for charcoal, have generated significant pressure on mangroves, affecting their conservation status on mangroves. The community response through restoration reflects an effort to mitigate impacts and reverse the degradation process. This provision represents an opportunity to develop participatory regeneration strategies that integrate the knowledge and needs of local communities, which could enhance the long-term effectiveness and sustainability of conservation efforts in these environments. Taking Ecuador as a reference, the country has implemented a Conservation Plan with Communities, which has allowed the protection of approximately 69,300 ha of mangroves [

54]. The National Plan for the Conservation of Mangroves in Continental Ecuador (2019–2030) is a strategic effort aimed at protecting and restoring mangroves in Ecuador, promoting their sustainable management through community participation, scientific research, and multi-sectoral collaboration. A key measure of the plan is the “Mangrove Partner” program, which facilitates sustainable use agreements, allowing local communities to manage mangroves sustainably while obtaining economic benefits. This model is transferable to other regions, such as Chame Bay, where it could incentivize local conservation and income generation from sustainable practices, thus strengthening community resilience.

The information provided by charcoal producers and agricultural producers is valuable for assessing community perception of mangrove regeneration, identifying challenges and opportunities in regeneration efforts, customizing communication and awareness strategies, measuring community engagement, and encouraging community participation.

Rhizophora mangle,

L. racemosa, and

A. germinans are species with commercial value for communities that produce charcoal and are extracted from the mangrove causing its degradation [

42]. The greater participation of charcoal burners in restoration actions compared to farmers suggests that there are opportunities to promote mangrove restoration in both groups. This finding highlights the need to develop specific programs that not only maintain the interest of charcoal burners, but also encourage greater involvement of farmers. By creating strategies tailored to the characteristics and needs of each group, the success of restoration projects and the long-term sustainability of the ecosystem could be maximized. The involvement of charcoal producers in restoration actions suggests that there is a growing awareness and interest among this group in the importance of mangrove restoration. This could be indicative of a gradual [

55] change in practices and values, as charcoal producers are directly linked to activities that may have negative impacts on mangroves. This involvement could be influenced by factors such as public opinion pressure, government regulations, or even awareness initiatives promoting environmental conservation.

This study highlighted the participation of farmers in mangrove restoration actions. Participation may be related to land use and proximity to mangrove areas. Participation in restoration activities is prominent among farmers, suggesting that there is a shared understanding of the importance of these actions. Of those who participated in restoration actions, the specific percentages of participation in the different activities (seed collection, mangrove planting, and nursery propagation) provide useful information on the preferences and capabilities of those involved. Participation in mangrove planting stands out as the most common activity, suggesting an understanding of the importance of strengthening the mangrove population for ecosystem health. Such is the case in El Palmar (Tabasco, Mexico) where community members planted

R. mangrove propagules in an area of 160 ha under restoration [

47]. On the other hand, seed collection and nursery propagation also show a significant degree of participation, indicating a commitment to the preservation of the mangrove life cycle. For example, the Mangroves of Colombia Project in its phase II has promoted community participation in the restoration of degraded mangrove areas [

56], where a transplant of

R. mangle from the Canal de Diques zone to the Barranca Zone in Colombia was carried out, the recovery has been successful in areas affected by high salinity [

57].

Taken together, these results suggest that, although users may have more positive attitudes towards mangrove restoration, a continuous, multidisciplinary approach is required to reverse degradation. Although these activities could be seen as contradictory to their primary occupations, the willingness to participate and positive perceptions indicate that the ecological and socioeconomic importance of mangrove conservation has been successfully conveyed. For example, forest restoration with stakeholders in semi-arid areas of North Africa was conducted with knowledge sharing, mutual assistance, environmental education, and social solidarity, resulting, according to respondents, in learning new ideas in ecological restoration, erosion, and flood control [

58]. These results also have implications for collaboration and inclusive restoration program design, as they seem to suggest that different sectors may have a common interest in mangrove protection.

In terms of user perception, the fact that there do not appear to be significant differences in relation to educational level and social interaction patterns is an important finding. This could indicate that the positive perception towards mangrove restoration is shared by a wide range of individuals, regardless of their educational level or social network. Within the process communities become active agents in the protection of their environment [

21], generating a sense of responsibility [

59]. The results suggest that awareness and support for mangrove conservation could be rooted in broader values and general appreciation of the ecological benefits provided by these ecosystems [

60]. Active community participation in restoration ensures that care and monitoring of the area continues over time, contributing to the long-term sustainability of mangroves undergoing restoration [

61].

The present study emerges as a significant contribution in the context of mangrove restoration in Central America, as it provides a deeper understanding of the perceptions and preferences of communities in mangrove areas with diverse social and economic contexts. The data collected reflect a diversity of opinions and needs in relation to mangrove restoration, providing a solid basis for the design of engagement and participation strategies that are truly inclusive and effective.

A key aspect highlighted by this study is the variability in community perceptions of mangrove conditions, causes of mangrove degradation, and preferences for restoration methods. The study conducted in southeastern Cuba highlights how local communities recognize the ecosystem services of mangroves, although they do not directly depend on them for their livelihoods. Perceptions of these services vary according to respondents’ occupation and locality, which is consistent with the importance of mangroves in coastal protection and local livelihoods through fishing and agriculture [

38]. This variability correlates with the different social and economic contexts in which these communities find themselves. Therefore, the study recognizes that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to mangrove restoration and that it is essential to consider the particularities of each context.

In this sense, the results of the study provide guidance for the adaptation of restoration strategies to the specific conditions and perspectives of each community. For example, in areas where deforestation is identified as the main threat to mangroves, strategies may focus on promoting reforestation practices and raising awareness of the importance of conserving forest cover. In contrast, in places where agricultural activities are perceived as a threat, strategies could include the promotion of sustainable agricultural and livestock practices. This is consistent with the findings of [

62], who noted that agricultural and aquaculture activities, along with anthropogenic pressures, are significant contributors to mangrove deforestation globally.

In addition, the study also highlights the need to actively involve the community in the planning and implementation of restoration actions. The acceptance of assisted regeneration by most respondents and the preference for mangrove species diversity in restoration provides valuable guidelines for the implementation of restoration projects with community support and participation.

Ultimately, the study highlights the importance of tailoring mangrove restoration strategies to the specific circumstances of each community and involving local stakeholders in the decision-making process. These findings will serve as a basis for the design of future restoration strategies that are socially inclusive and economically sustainable, thus contributing to the long-term preservation of mangroves in Central America.