Abstract

Mangroves are vital intertidal ecosystems that support biodiversity and protect coastal communities, but face increasing pressure from anthropogenic activities that sustain local livelihoods. It is crucial to integrate the social dimension into conservation efforts by encouraging community participation in mangrove restoration. Chame Bay, located on the central Pacific coast of Panama, is a protected area with significant mangrove cover, but despite its management plan, degradation continues due to intensive timber extraction for charcoal production and insufficient natural regeneration. This study investigates local knowledge and perceptions of mangrove functions and regeneration. A proportional stratified sampling of the Chame Bay population was used, with 300 interviews conducted among key stakeholders, including residents and mangrove resource users. Variables such as age, education, and profession were analyzed in relation to perceptions, participation, and willingness to participate in restoration efforts. Results indicate that 24.67% of the population’s primary economic activity is charcoal production from mangrove wood, with 15% of producers already involved in restoration and 60% willing to participate. These findings highlight the potential for community-driven restoration and emphasize the need for environmental education to encourage participation. This study provides essential information for designing restoration strategies in mangrove areas in Central America.

1. Introduction

Tropical coastal ecosystems are globally recognized for their rich biodiversity and high productivity [1]. Among these ecosystems, coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangroves play pivotal roles in maintaining oceanic health and balance [1]. Mangroves are intertidal ecosystems that provide vital biodiversity support and coastal protection worldwide [2]. They thrive at the interface between terrestrial and marine environments, forming unique habitats that stabilize coastal areas. Beyond biodiversity, mangroves deliver essential ecosystem services, including flood protection, water storage, and habitat preservation [3,4]. They are highly productive environments, providing habitats for 75% of commercial fishery species during various life stages [5,6]. For example, Indonesia is an important habitat for its diversity of fish and invertebrate species, the abundance of which supports the livelihoods of the country’s coastal communities [7]. In mangroves, factors such as soil and water are essential because they play a fundamental role in the natural distribution and biological activity of mangroves [8]. Also, they create physical and chemical conditions that affect abiotic factors such as soil anaerobiosis, organic matter accumulation, and nutrient availability, but also biotic such as species richness and composition. Thus, they determine the species that remain in wetlands and their primary productivity [9]. In addition to these ecological functions, mangroves have recently been recognized in the fight against climate change [10] because they capture and store blue carbon, help protect coasts, maintain marine biodiversity, and support the sustainability of local communities [11]. For this reason, preservation and restoration are essential in the fight against climate change and in adapting to its impacts.

The degradation and loss of species diversity in these ecosystems are exacerbated by challenges such as habitat loss, which can significantly diminish ecosystem services [12]. Activities such as mangrove cutting for charcoal production, building materials, fuelwood, and fishing further contribute to these threats [13]. While these activities have contributed to economic and social development, they have also pressured mangrove ecosystems significantly, compromising their biodiversity, structure, and functioning. In recent decades, mangroves have faced increasing pressures due to various anthropogenic activities, leading to significant degradation and raising concerns about their conservation and ecological functioning. The expansion of the human population and the consequent increase in demand for natural resources has led to the intensive exploitation of mangrove areas for purposes such as agriculture, aquaculture, urbanization, mining, and industry [14]. The clearing of mangroves for timber, charcoal, and space for human activities has led to ecosystem fragmentation and degradation, which can negatively affect biodiversity and the ability of mangroves to provide essential ecosystem services [15]. In addition, advancing agriculture and aquaculture often involves introducing chemicals and nutrients into nearby water bodies, affecting habitat quality and water pollution [16,17]. Overexploitation of fishery resources and soil degradation have also directly impacted the health and resilience of mangrove ecosystems [17].

According to the Environmental Information Directorate (DIA) of the Ministry of Environment, Panama has 177,293 ha of mangroves, of which 164,124 ha are in the Pacific and 13,169 ha in the Caribbean: representing 2.4% of the country’s forest cover. Panama’s intertidal mangrove is home to the most significant number of mangrove species in the Americas [1]; 12 species of the 65 species identified worldwide have been reported [18]. The mangroves of Chame Bay are home to many marine and terrestrial species. They are part of the tropical and subtropical dry forest ecoregion, which is in a critical state of conservation [19]. One of the most notable impacts of anthropogenic activities on mangroves is habitat loss due to converting mangrove areas into agricultural expansion, the establishment of farms, shrimp farms, salt ponds, or urban land [20].

According to data from the Environmental Information Directorate of the Ministry of Environment, Chame Bay experienced a worrying loss of 6% of mangrove forest from illegal logging between 2012 and 2019. The National Directorate of Protected Areas and Biodiversity of the Ministry of Environment highlights that these mangroves face significant threats derived from anthropogenic activities, such as mangrove forest fragmentation, overuse, and excessive exploitation for mangrove charcoal production and mangrove stick extraction resulting in biodiversity loss. Exploitation for charcoal production contributes to the loss of this vital ecosystem and generates greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to climate change. In addition, residents are in a vulnerable position due to exposure to the smoke generated by the ovens used in this extractive activity [21].

Anthropogenic actions have become increasingly important in defining the dynamics and trajectory of mangrove ecosystem regeneration worldwide [13]. For example, in Indonesia coal mining represents the main anthropogenic activity causing disturbance to mangrove ecosystems [22]. Additionally, the extent of mangroves continues to decrease at an alarming rate due to land use change, and this phenomenon is aggravated mainly by the expansion of tourism developments [16,23]. These developments often promote the construction of hotel infrastructures that are not ecologically sustainable [17]. This uncontrolled growth in areas close to mangroves seriously threatens the integrity of these fragile ecosystems [17]. This situation reflects a lack of effective regulation and control that jeopardizes the conservation of mangroves, despite their vital importance in climate change mitigation and their essential role in coastal protection and the maintenance of marine biodiversity. The urgent need to address these problems and promote sustainable development practices in mangrove areas is undeniable if we are to preserve these crucial ecosystems for future generations [20]. Due to the loss and deterioration of mangroves, it is essential to implement not only conservation measures to preserve the mangroves that are still in good condition, but also restoration actions that enable the recovery of critical elements, such as their original structure, functions, and dynamics. Therefore, mangrove restoration is fundamental in conserving these valuable ecosystems and mitigating climate change’s impact.

Ecological restoration goes beyond just recovering the natural aspects of the ecosystem [21] and it is now recognized that restoration must encompass a broad spectrum of practices that not only include aspects of the natural sciences, but also dimensions of the human sciences, economic factors, and relevant cultural dimensions [24]. This perspective implies that successful restoration requires a holistic view considering historical, social, cultural, political, aesthetic, economic, and moral attributes [25]. In addition, it must consider how restoration efforts relate to patterns of resource use and the values and activities that are significant to the society in question [26]. Also, the importance of community involvement, with a sound scientific understanding of the ecosystem’s preconditions, is emphasized [27]. Ultimately, it is recognized that the relationship between natural ecosystems and human influence is diverse and variable [28]. The diversity of ecosystems is evident, some have been profoundly transformed by human activity [29], while others have evolved due to traditional practices that resemble natural disturbances [30]. This nuanced understanding of the relationship between humans and nature is critical to the planning and implementation of restoration projects that are effective and culturally sensitive [31]. The adaptation of restoration strategies to the particularities of each ecosystem and the historical and cultural interaction is therefore fundamental to achieving positive and lasting results [32].

In order to address the problems posed by the degradation of mangroves in Chame Bay and the importance of their restoration, this research has the following objectives: to assess the level of knowledge and perception of local communities and users about the ecological relevance of mangroves and the ecosystem services they provide; to analyse the current participation of farmers and charcoal producers in mangrove restoration actions and their willingness to get involved in future ecological regeneration processes; and to examine the relationship between socio-demographic variables, such as age, educational level and professional sector, with the perception, involvement and willingness to participate in restoration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Research

The perception survey is a valuable tool that could provide us with essential information to make informed decisions and design strategies promoting sustainability and mangrove regeneration. At the same time, this tool allows us to respect the socioeconomic and cultural dynamics of the communities that depend on these critical ecosystems, thus ensuring environmentally responsible and socially inclusive management.

Conducting this survey in the Chame Bay mangrove represents a fundamental step in obtaining crucial information on the socioeconomic situation and, equally relevant, the perception of the communities that use the mangroves concerning their regeneration process. The surveys applied to the inhabitants and users of the Chame Bay mangrove responded to the following variables: (a) users’ knowledge of mangroves, (b) local perception of mangroves and the services they provide, (c) mangrove-related activities, and (d) mangrove management and conservation actions, and were applied to a representative sample of the target population. This valuable information becomes essential for understanding the complex interactions between humans and the mangrove ecosystem. The analysis and use of the data resulting from the survey is important, as it will allow us to shed light on the direct and indirect effects that anthropogenic processes exert on mangrove regeneration. The perception of the communities that interact with these ecosystems is critical in understanding how mangrove areas have been affected over time due to human influence.

This knowledge is vital for developing effective conservation and restoration strategies. The survey results will be key in expanding our understanding of how mangrove degradation impacts mangrove-dependent communities. In addition, they will allow us to assess the willingness of these communities to participate in restoration processes. By identifying the factors that influence the perception and desire to engage in mangrove restoration, we can tailor conservation and management strategies to be more effective and attuned to the needs and desires of local communities. In our study, we set out to examine the perception and knowledge of mangrove communities and users regarding the regeneration of these vital ecosystems and to understand how this regeneration influences their lives. By analyzing these perceptions and knowledge in detail, we were able to gain a clear picture of the opinions and perspectives of mangrove users and inhabitants. Based on these analyses, we can offer fundamental recommendations that contribute to the sustainable management of these valuable ecosystems, ensuring their long-term conservation and promoting harmony between the local community and their natural environment.

2.2. Study Area

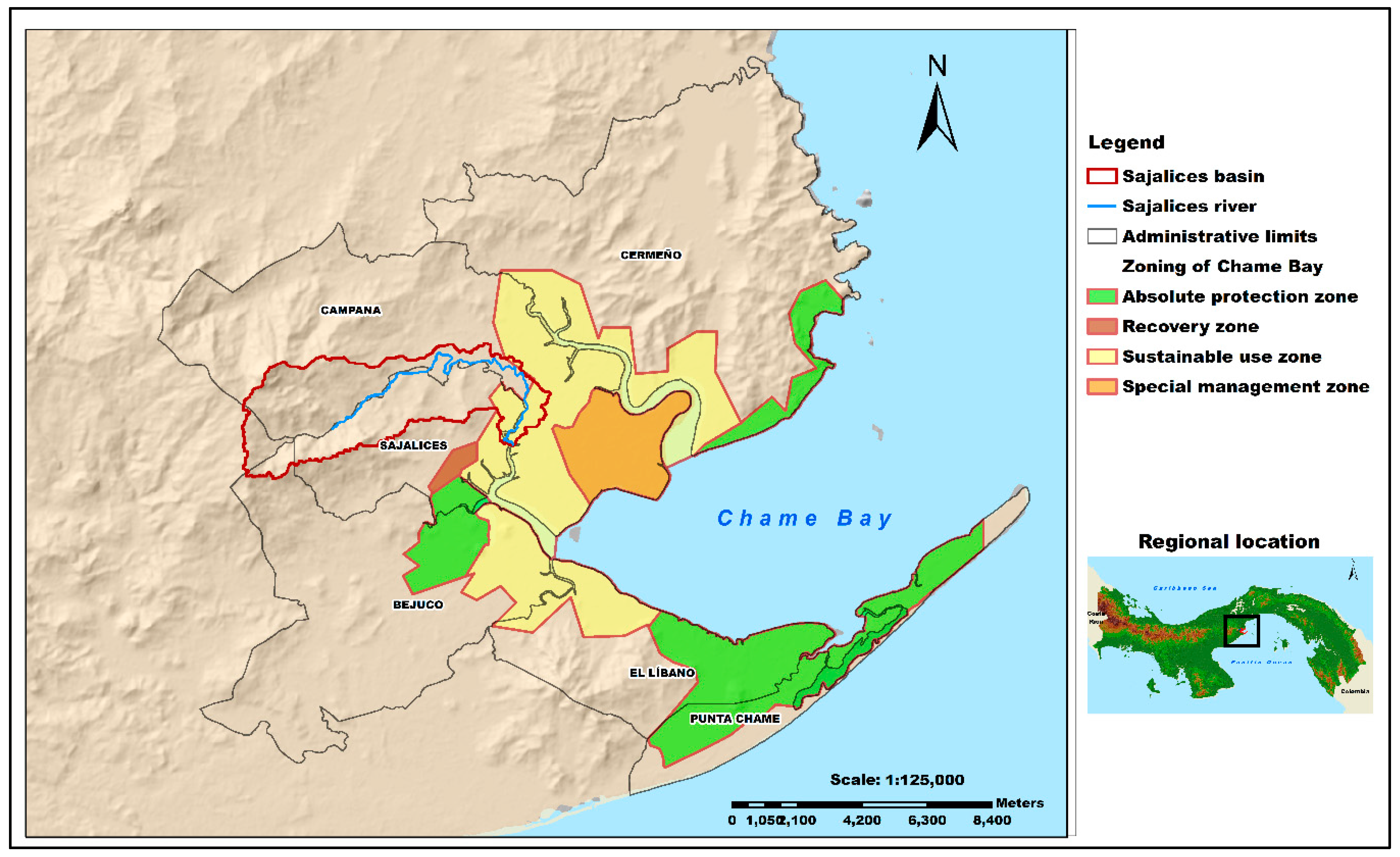

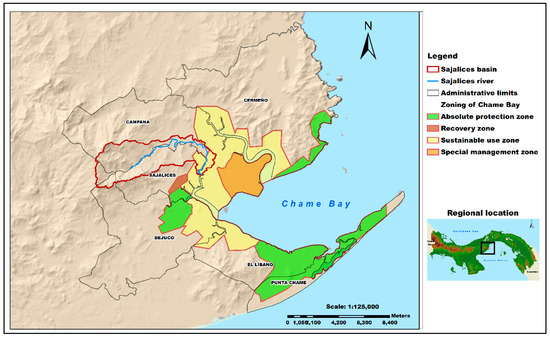

The present study was conducted in the Chame Bay Protected Area, Panama. The terrestrial portion of Chame Bay, located 65 km southwest (Figure 1) of the capital city, between the coordinates 8°39′48.6″ N, 79°50′52.5″ W, and 8°39′35.4″ N, 79°50′48.3″ W, includes a mangrove extension of 6000 ha where the benefits and overexploitation of this type of ecosystem converge [33]. The mangrove forests of Chame Bay have seven species of mangroves: Rhizophora mangle, Avicennia bicolor, Laguncularia racemosa, Pelliciera rhizophorae, Avicenia germinans, Conocarpus erectus, and Rhizophora racemosa. The predominant species are Rhizophora mangle and Rhizophora racemosa; Avicennia germinans and Avicennia bicolor are found in pure stands and forming mixed stands. There are also species associated with mangrove vegetation such as Anacardium excelsum, Guazuma ulmifolia, Coccoloba uvifera, Acrostichum aureum and Fimbristylis spadicea [34].

Figure 1.

Location of Chame Bay Protected Area.

2.3. Survey Design

This study used proportional stratified sampling of the population within the Chame Bay protected area (Table 1) to ensure that each critical subgroup was adequately represented. The strata are defined as the protected area’s township: Punta Chame, El Líbano, Bejuco, Sajalices, Campana, and Cermeño. Stratified selection ensured that each geographic location in the protected area had a proportional presence in the final sample.

Table 1.

Number of surveys applied per township within the protected areas of Chame Bay.

2.4. Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was calculated considering a confidence level of 95%, a margin of error of 5%, and the size of the total population per township within the protected area; the following formula was used:

where:

n: Sample size.

N: Population size.

: Standard deviation of the population (0.5).

Z: Critical value based on the desired confidence level (1.96).

e: Acceptable limit of sampling error.

The confidence level used in the study indicates that there will be a 95% probability that the results are within an acceptable margin of error (Z = 1.96). The margin of error we used is 5% (e = 0.05), which indicates that the survey results may vary by +/−5% concerning the actual population. The population size was 300 surveys, ensuring a significant representation of the population studied.

2.5. Implementation of the Perception Survey

Before the full implementation of the survey, we conducted an initial set of 10 pilot surveys to verify the questionnaire’s effectiveness and clarity. During this pilot phase, adjustments and corrections were made to the survey format based on participants’ responses and comments. This process ensured consistency and comprehensibility before applying the full sample. The survey was conducted through interviews with inhabitants and users in each village within the protected area (Table 1, Figure 1). The questionnaire was designed with questions based on ecosystem services: supporting, provisioning, regulating, and cultural [35]. The surveys responded to the following variables: (a) users’ knowledge of mangroves, (b) local perception of mangroves and the services they provide, (c) mangrove-related activities, and (d) mangrove management and conservation actions, and were applied to a representative sample of the target population. The survey team was trained to ensure uniformity in data collection.

2.6. Ethical Considerations and Consent

In the Panamanian context, research is regulated by the National Bioethics Committee (CNBE), established in Executive Decree No. 1843 [36]. The CNBE, focused on health research, oversees ethical issues related to research in the country. Importantly, since our study is not within the scope of health research, specific permission from the CNBE was not required to conduct the survey. Despite this, strict ethical protocols were followed during the implementation of the study. Before applying the questionnaire, detailed information about the purpose of the study was provided to the respondents. Their consent was explicitly requested, and they were assured of the absolute confidentiality of their responses. This approach ensured that the study was conducted in an ethical and respectful manner, meeting the standards of integrity, privacy required for research and absolute confidentiality of their personal information.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The chi-square test statistic was used within the framework of our research on the perception of users in relation to mangrove restoration actions. This statistical analysis was used to evaluate and understand the relationship between the variables associated with the participants’ perceptions and the actions implemented in the mangrove restoration process. The chi-square test allowed us to examine the possible dependence or independence of the variables, which in turn shed light on the perceptions of the users in relation to these mangrove restoration actions.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Respondents

The respondents’ profile reveals a balanced distribution in terms of gender, with 55% of respondents being female and 44.7% male, while a minimal percentage of 0.3% chose not to answer. A wide diversity in terms of age ranges is observed, reflecting the inclusion of different age groups in the study. For example, 22.3% of respondents fall in the 18–30 age range, representing youth and young adults in the sample. Likewise, 30.3% were between the ages of 31 and 50, indicating the presence of people in the intermediate stage of life. On the other hand, 33.3% belong to the 51 to 71 age group, reflecting the significant presence of older individuals in the sample. In addition, 14% of the respondents are over 71 years of age, highlighting the inclusion of elderly people in the study. Regarding the educational background of the respondents, the sample reflects a diversity in terms of education. It is observed that 0.7% of the respondents have postgraduate studies, indicating a limited presence of individuals with a high level of specialization, 14.7% have a bachelor’s degree, indicating individuals who have completed university studies, 15.3% have technical training, reflecting the presence of individuals with specific skills and knowledge, 41% have completed secondary education, indicating the largest representation of individuals with an intermediate educational level, and 28.3% of the respondents have primary education, highlighting a basic educational level in the sample.

The result of the data analysis indicates differences by gender for the earnings. Among the total number of men surveyed, 56.53% identified themselves as salaried employees, while 43.47% stated that they were self-employed. On the other hand, 59.06% of the women surveyed indicated that they were salaried, and 40.94% reported being self-employed. The analysis of the household income of the respondents reveals a wide variety of economic situations within the sample, reflecting the socioeconomic diversity present in the population studied. Forty-six percent of respondents report a household income of less than $500 per month, suggesting the significant presence of households with limited economic income. On the other hand, 39.7% of respondents have incomes between $600 and $800 per month, indicating a considerable proportion of households with moderate incomes, considering that the minimum wage in Panama is $600. In addition, 14.3% of respondents report incomes above $801 per month, reflecting the economic diversity of the community.

Thirty-eight percent of respondents indicated that the mangrove represents regulating services (water cycle, erosion control, soil fertility maintenance, water regulation, sanitation, and pollination), followed by 32% for provisioning services (food, water: agriculture and consumption, energy resources: firewood, raw materials, genetic resources), and 26% of respondents who did not answer. In the case of cultural services (education, cultural diversity, aesthetic value, belonging, scientific knowledge, recreational services, and ecotourism) and support services (photosynthesis, species habitat, conservation of genetic diversity, nutrient cycling, primary production), 2% of respondents consider these services to be what the mangrove represents.

3.2. Ecosystem Service Provisioning in Relation to Economic Activity and Interaction with the Mangrove

The ecosystem service of provisioning plays a crucial role in the economic activity of the communities that interact with mangroves. In the case of the primary sector, which includes agricultural and fishing activities, accounting for 38% of respondents, mangroves provide essential resources such as fish, shellfish, and timber, which are fundamental for subsistence and local commerce. This sector relies heavily on the health of the mangroves to maintain their productivity and ensure the livelihoods of the families that depend on these natural resources. On the other hand, the tertiary sector, which comprises 58% of respondents, benefits indirectly from mangroves through service and commerce-related activities. To a lesser extent, the secondary sector, with 2% of respondents, also interacts with mangroves through the transformation of products derived from these ecosystems, such as the production of handicrafts and other manufactured goods. Finally, the remaining 2%, classified as “other”, includes various activities that, although not specified, may be related to the sustainable use and conservation of mangroves, highlighting the multifaceted importance of these ecosystems for the local economy and the provision of essential resources.

3.3. Ecosystem Service Regulation and Mangrove Conservation

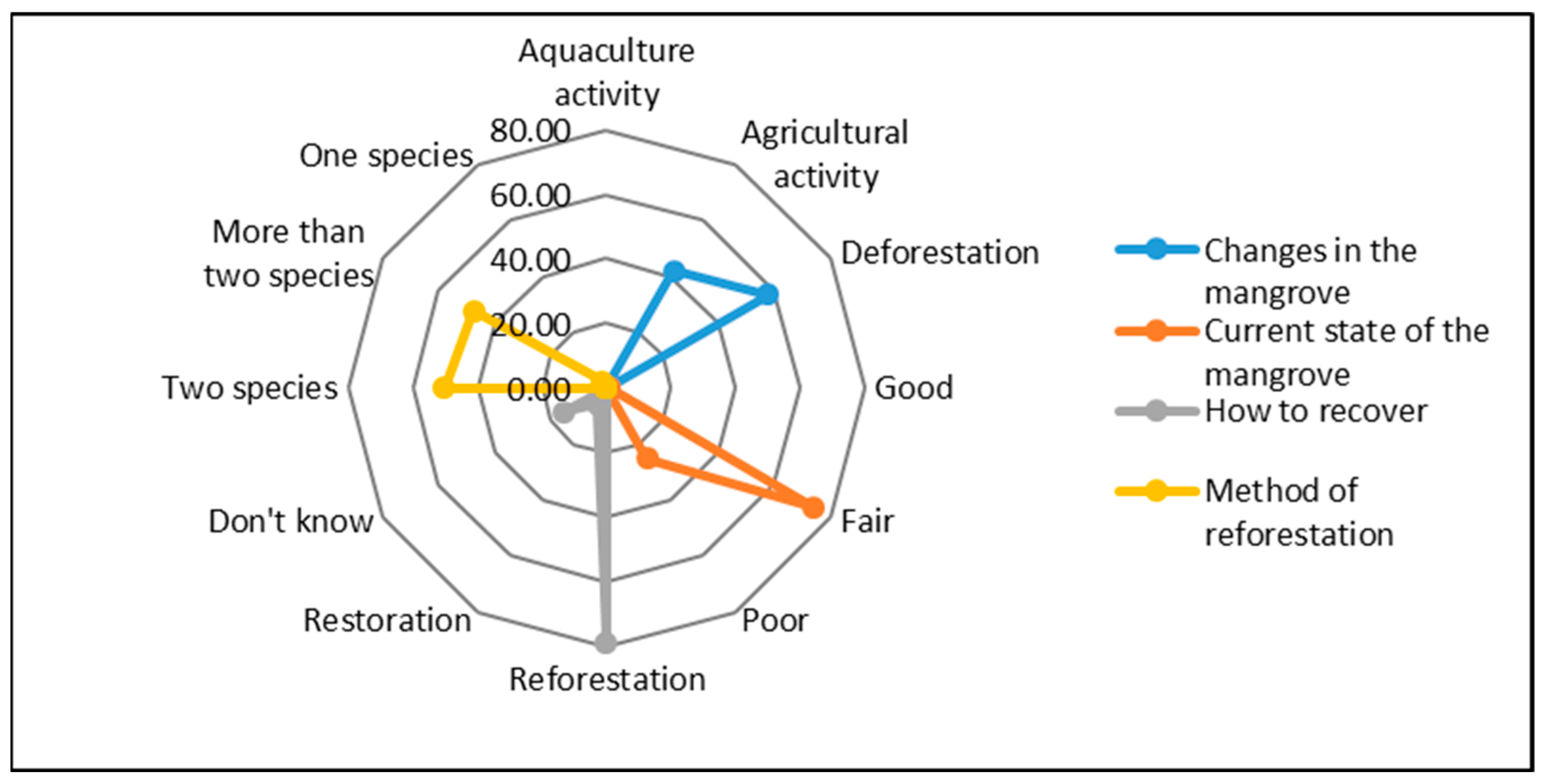

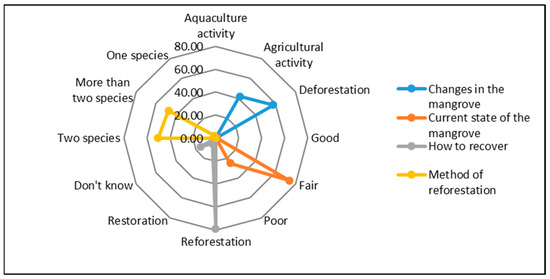

The results highlight that many respondents (57.87%) attribute changes in the mangrove forest mainly to deforestation, underscoring concern about the loss of forest cover in these ecosystems. In addition, agricultural activity is also perceived as another factor, mentioned by 41.87% of respondents (Figure 2). Regarding the perception of the current state of the mangrove, many respondents (74%) consider it to be in fair condition, while a quarter of respondents (25%) perceive it to be in poor condition. Only a small percentage (1%) consider the mangrove to be in good condition, suggesting widespread concern for the health of these ecosystems. Many respondents (79.21%) suggest that reforestation is the best way to recover the mangrove, highlighting the importance of taking restoration actions. However, only 15.05% of respondents advocate plantation, indicating the possibility that they may consider restoration approaches other than mangrove planting. In addition, a small percentage (5.73%) do not have a clear opinion on how to restore the mangrove (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Community perception of the current state, changes, and reforestation methods of mangroves shows a visual representation of how local communities perceive different aspects related to mangroves. These aspects include the changes observed in the mangrove ecosystems, the current state they are in, the proposed recovery methods, and the reforestation techniques used or recommended.

In relation to restoration methods, most respondents (69%) believe that mangrove restoration should be carried out using assisted regeneration, underscoring the acceptance of this technique among the community, however, 30% of respondents believe that both methods (assisted and natural) should be used. Only 1% advocate natural regeneration as the primary approach (Figure 2). Regarding preference for the number of mangrove species in assisted regeneration efforts, half of the respondents (50%) felt that two mangrove species should be used. Forty-eight percent prefer to use more than two species. Only a small percentage (2%) believe that a single species is sufficient for regeneration (Figure 2). Respondents show a varied knowledge of mangrove species, with Rhizophora mangle, Laguncularia racemosa, and Pelliciera rhizophorae as the best known.

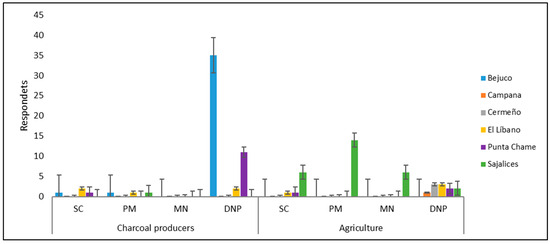

3.4. Ecosystem Support Service and User Participation

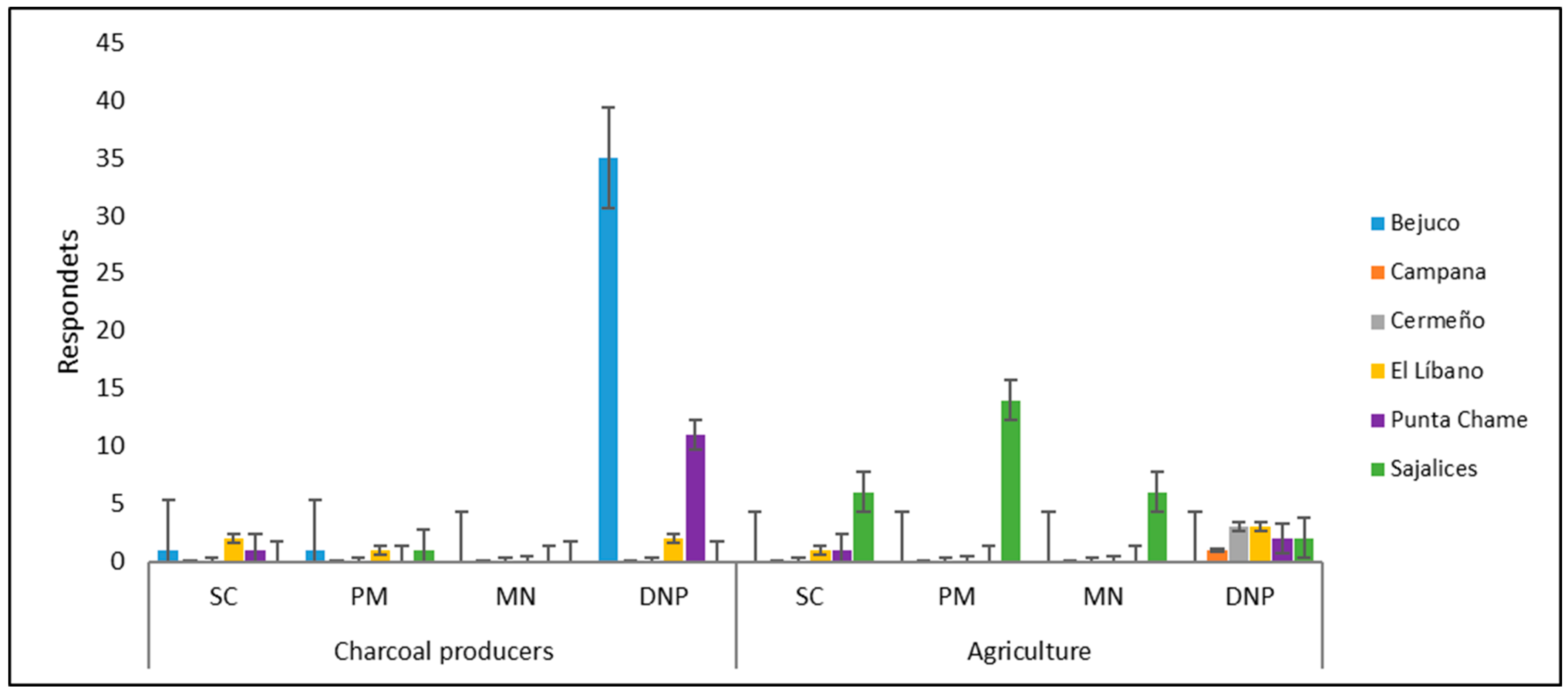

Among the charcoal producers, 15% have already participated in restoration actions. Of the group that participated in restoration, 38.78% were involved in mangrove seed collection, 44.90% in mangrove planting, and 16.33% in nursery propagation. 54.90% of the farmers surveyed have participated in restoration actions. 35.71% participated in mangrove seed collection, 53.57% in mangrove planting, and 10.71% in nursery propagation. Figure 3 shows the participation of respondents in various activities related to mangrove conservation and restoration, categorized into townships. In the case of charcoal producers, respondents from Bejuco showed a notably higher tendency to not participate, while the other localities such as Campana, Cermeño, El Líbano, Punta Chame, and Sajalices have considerably lower participation in all activities. As for farmers, respondents from Sajalices stood out for their participation in mangrove planting, being the group with the highest participation in conservation activities. The other activities and localities showed more balanced participation, but in general, the option of “not participating” remains predominant in several communities, with the exception of Sajalices in the nursery and mangrove planting activities. Users’ perceptions of mangrove restoration do not seem to differ according to educational level and social interaction patterns.

Figure 3.

Restoration actions by producers. The figure shows the restoration actions carried out by farmers and charcoal producers by township. The bars indicate the people who have participated by township in activities such as seed collection, mangrove planting, and nursery propagation, which shows the degree of involvement in mangrove regeneration. SC: Seed collection; PM: Planting of mangroves; MN: Mangroves nursery; DNP: Does not participate.

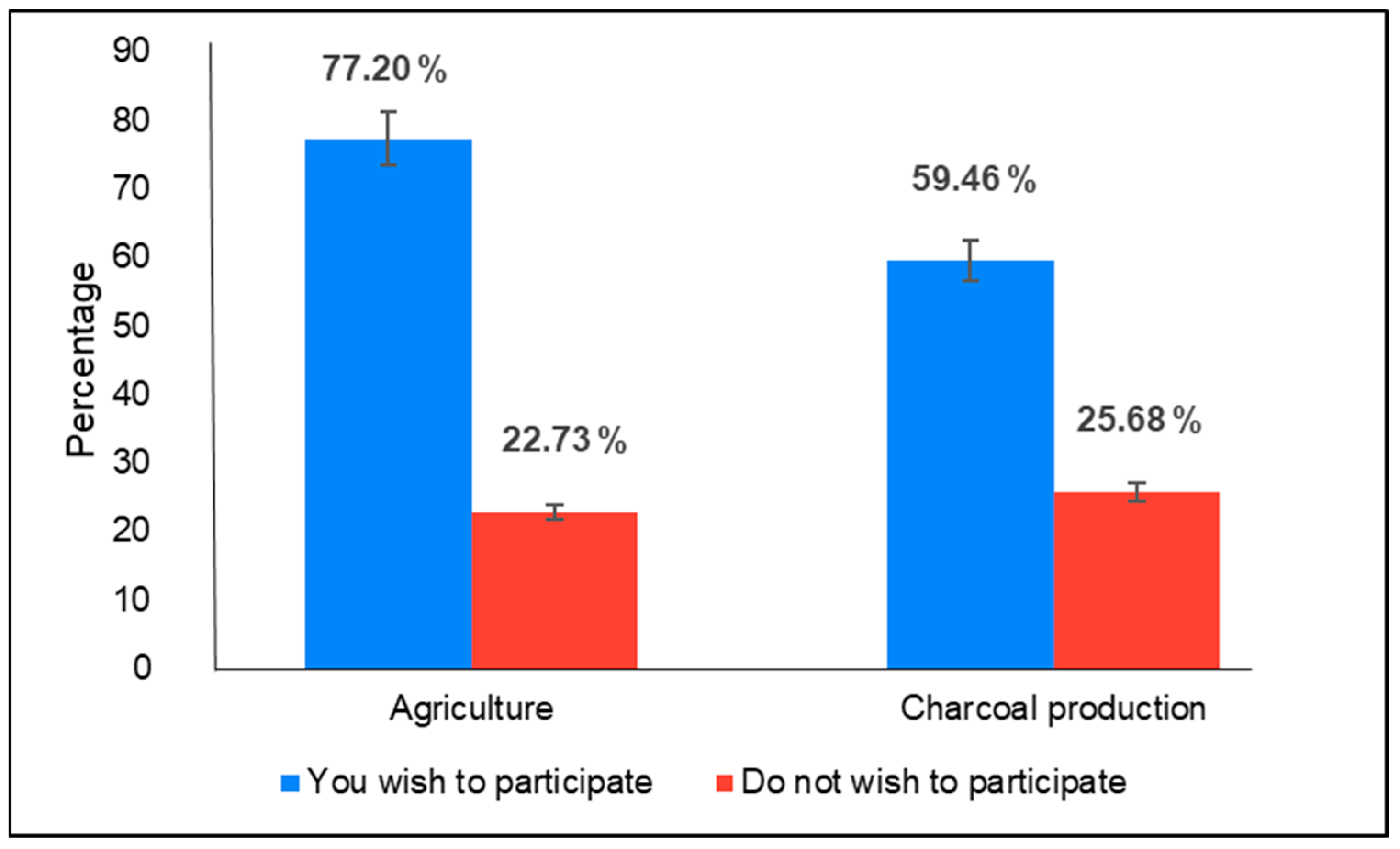

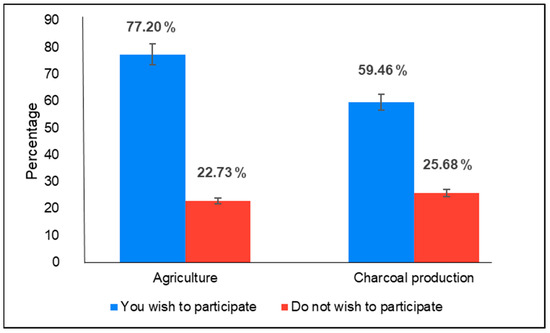

Since charcoal production is the economic activity with the greatest impact on the mangrove, the results indicate that 77.27% of the agricultural sector expressed interest in participating in these activities, while 22.73% expressed no desire to get involved. On the other hand, in the case of charcoal producers, 59.46% showed a willingness to participate, while 25.68% showed no interest (Figure 4). The error bars associated with the graph indicate variability in responses, being more pronounced among farmers compared to charcoal producers. However, when comparing the perception of participation in restoration processes between the two groups, no significant differences were observed, suggesting a similar general trend in terms of willingness to get involved in mangrove restoration.

Figure 4.

Involvement of charcoal producers and farmers in mangrove restoration activities.

The results of the chi-square statistical analysis (Table 2) reveal that farmers have a significantly higher participation in mangrove restoration actions. This result suggests that farmers are more willing or involved in activities that promote ecosystem regeneration. In addition, charcoal producers also show significant participation in these restoration actions, although in a smaller proportion. However, when directly comparing participation between farmers and charcoal producers, no significant differences were found, indicating that both groups are equally willing to participate in restoration, although the motives or magnitude of their participation may vary.

Table 2.

Chi-square analysis. The chi-square test was applied to the surveys applied to the users and inhabitants of the mangroves of Chame Bay to evaluate the relationship between various qualitative variables and the respondents’ perception of the mangrove. This analysis allowed us to determine if there was a significant association between factors such as participation in restoration activities (agriculture and charcoal production), interest in reforestation, the current state of the mangroves, knowledge about ecosystem conservation, and the productive practices of the users.

4. Discussion

The results of the surveys applied to the users and inhabitants of the mangrove forest of Chame Bay offer detailed insight into their knowledge, perceptions, and experiences about this valuable ecosystem. These results provide an in-depth understanding of the social, economic, and environmental dynamics and offer useful information to guide future management and conservation strategies in the protected area. Also, the analysis of the data obtained revealed several significant aspects related to the salary situation by gender, the respondents’ main economic activity, and their perception of the services provided by the mangroves.

Regarding gender and age status profile, the results indicate that a higher percentage of female respondents identified themselves as wage earners compared to men. This trend could suggest a greater presence of women in roles that have traditionally been considered salaried jobs. This could result from changes in job opportunities and greater inclusion of females in previously male-dominated sectors [37]. In terms of gender and employment, it has been identified that in several regions women have a greater presence in salaried jobs, reflecting both advances in inclusion and possible wage inequalities. In a similar survey conducted about mangrove governance in southeastern Cuba, 46.2% of respondents were women, with a considerable number of them participating in the public sector [38]. However, it is important to consider the possibility that this greater presence in salaried jobs may also be related to the persistence of gender-based wage inequalities, where females could be more likely to occupy lower-paid positions [39,40]. On the other hand, the results also indicate that a higher percentage of male respondents identified themselves as self-employed than women. This trend could be related to the notion of independence and autonomy that is often associated with self-employment [41]. Some men may seek the flexibility and control offered by self-employment as a response to traditional expectations of being the main economic providers in the household. In addition, this difference could be related to inequalities in work opportunities, as some women may feel limited in their access to self-employment roles due to factors such as lack of resources or unequal access to networks and opportunities.

In Chame Bay, the predominant economic activities in the studied region are included in the tertiary sector, which is oriented towards services and commerce. This is influenced by tourism and recreational activities of the local population [42]. The primary sector also maintains a significant presence, highlighting the importance of agricultural and fishing activities in the region’s economy [34]. These results provide a deeper understanding of the distribution of economic activities among the respondents and their potential impact on the community and the region in general. The finding that the tertiary sector was identified as the one concentrating the majority of the economic activities of respondents is consistent with the global trend of transition towards service-based economies in many regions [43]. The strong presence of the tertiary sector indicates increasing urbanization, as well as the importance of trade and service activities for the local economy. Furthermore, this result can be an indicator of economic diversification and adaptation to changing market demands.

On the other hand, respondents who indicated that they were engaged in the primary sector (agricultural, charcoal, and fishing activities) indicated a significant proportion of individuals who depend directly on natural resources for their livelihoods. This reflects the continued importance of primary activities in employment generation and food supply. However, it may also point to challenges related to sustainability and natural resource management in the context of increasing pressure on the environment [44].

The most limited group of economic activities is in the secondary sector (industrial and manufacturing), which may indicate less industrialization in the studied region. This may have various economic implications, from a lack of industrial infrastructure to possible limitations in the availability of resources and skilled labor for manufacturing. Although this proportion is low, its importance should not be underestimated, as the secondary sector usually triggers broader economic growth processes.

The “other” category indicates activities not specified in the survey. This category may represent a diversity of occupations and economic activities that do not fit into the predefined categories. The existence of this category underscores the complexity and diversity of economic activities in the region, which may reflect adaptation and innovation in response to changing needs and emerging opportunities.

The results reveal important findings that shed light on the community’s perception of mangrove ecosystem degradation and restoration. One of the most prominent aspects is the attribution of deforestation as the main factor of change in the mangrove. This result reflects widespread concern about the loss of forest cover in mangroves and underscores the importance of addressing deforestation as a critical threat to the integrity of these ecosystems [45]. The perception of agricultural activity as another relevant factor suggests the need to consider conservation strategies that address agricultural practices in these areas.

The community’s assessment of the state of the mangrove shows divided opinions: while the majority considers it to be in fair condition, a significant portion perceives it to be in poor condition. This discrepancy could be due to variations in knowledge, experience, or economic dependence on the mangrove, as well as the environmental awareness of the respondents. This perception reflects widespread concern for the health and stability of mangroves, indicating the need to implement effective measures to ensure their long-term conservation [46].

This study reveals that the majority of respondents prefer reforestation as a method of mangrove recovery, indicating strong support for active restoration efforts to revive these crucial ecosystems. This preference is supported by a general understanding that mangrove planting can be an effective strategy for revitalizing these ecosystems [47]. However, it is important to recognize that this preference may be influenced by a lack of knowledge about alternative methods of mangrove restoration. The implementation of other techniques, such as hydrological restoration, water quality management, or coastal wetland conservation, could offer complementary or even more effective solutions in certain contexts [48]. However, a group of respondents show a preference for alternative methods of regeneration, suggesting that they consider options other than simply planting mangroves. This highlights the importance of exploring more diverse restoration approaches tailored to the specific conditions of each mangrove area.

In terms of restoration methods, the acceptance of assisted regeneration of respondents is an indicator that the community is willing to support approaches that involve active intervention in mangrove restoration. For example, one of the key strategies that has been implemented in the region is mangrove restoration through assisted regeneration, where they have carried out mangrove plantations in degraded or deforested areas [49].

The respondents who advocate the use of both methods (assisted and natural) demonstrate a deep understanding of the need to balance natural and assisted approaches. Through integration of natural methods (such as natural regeneration and conservation of existing habitats) with assisted approaches (such as reforestation and rehabilitation of degraded ecosystems), regeneration efforts can be successful and promote long-term mangrove recovery. The preference for the use of more than two mangrove species in assisted regeneration efforts highlights the importance of species diversity in the mangrove. This suggests that the community values the diversity of the ecosystem and understands the relevance of multi-species regeneration to strengthen the resilience of the Chame Bay mangroves [50].

Mangroves provide a variety of ecosystem services that contribute to the sustainable development of coastal communities [51]. Mangroves provide a wide range of ecosystem services that are fundamental to the sustainable development of coastal communities, including Chame Bay. Public perception of these services, especially regulating services such as carbon sequestration, prevention of natural disasters, and regulation of water flows, plays a key role in the effectiveness of conservation efforts [52]. The majority of respondents in similar studies recognize the importance of mangroves for coastal protection and their ability to support local economic activities such as fishing. This coincides with the results obtained in Chame Bay, where reforestation is seen as the most viable method to restore degraded mangroves. Coastal users and communities perceive mangroves as vital to their well-being and livelihoods and recognize the ability of mangroves to provide a range of benefits, such as coastal and erosion protection, provision of habitats for marine species, and contribution to food security through fisheries [53]. However, it is also crucial to promote greater knowledge about alternative restoration methods, such as hydrological restoration and water quality management, which may offer more comprehensive and sustainable solutions in certain contexts [38]. Also, environmentalists understand the critical role of mangroves in mitigating climate change by acting as carbon sinks and in improving water quality by filtering sediments and pollutants [11].

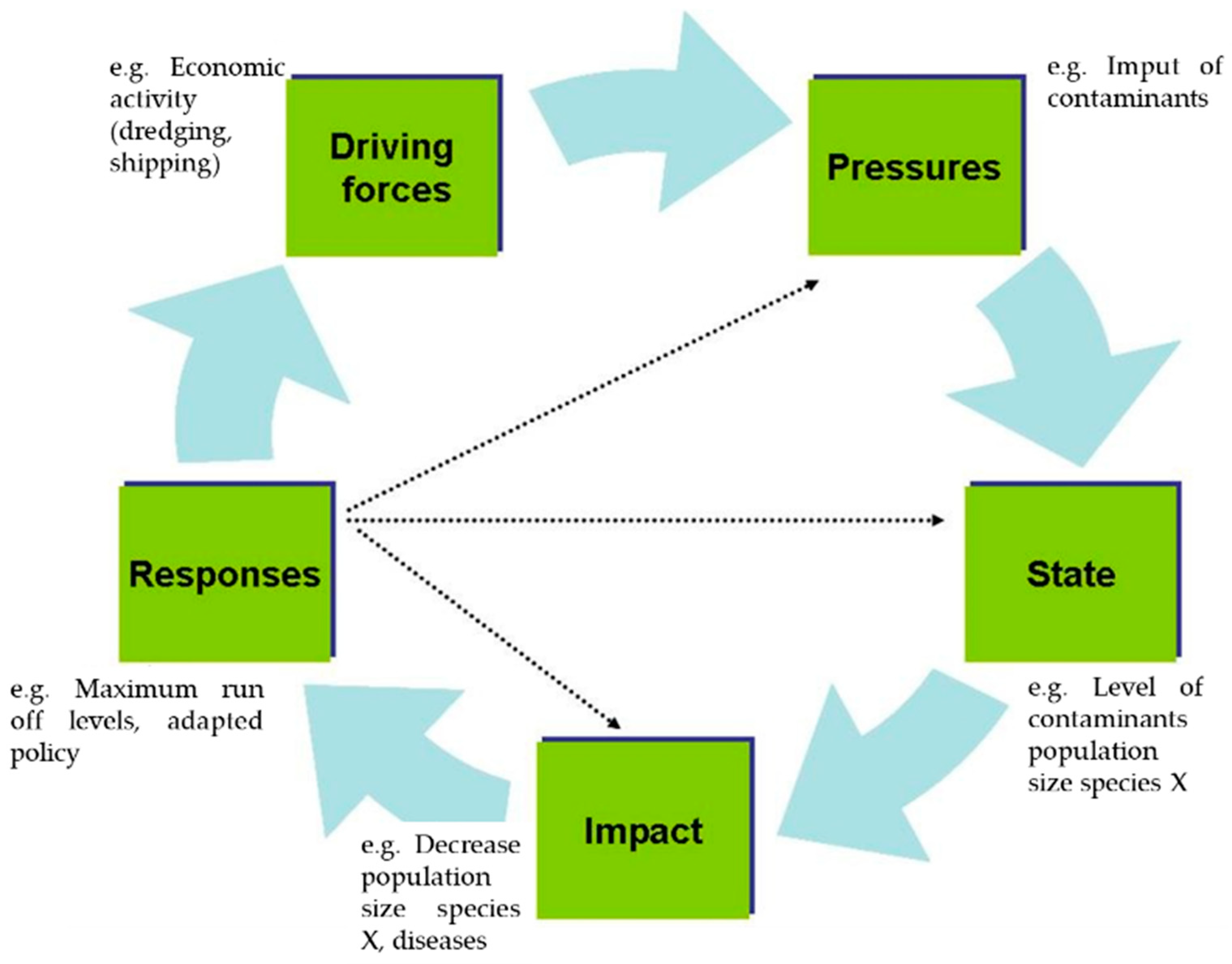

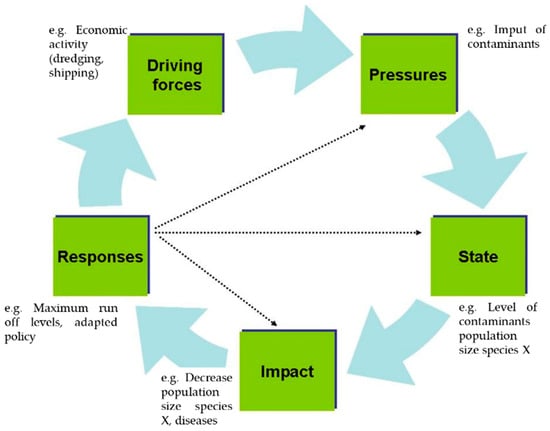

The analysis of participation in restoration actions highlights a positive attitude of both charcoal burners and farmers towards involvement in regeneration processes. This is important, as it suggests a genuine interest in mangrove conservation and regeneration on the part of key stakeholders involved in economic activities related to the exploitation of these ecosystems. This behavior can be interpreted under the Driving Forces-Pressure-State-Impact-Responses (DPSIR) framework, as shown in Figure 5. The driving forces, such as the demand for charcoal, have generated significant pressure on mangroves, affecting their conservation status on mangroves. The community response through restoration reflects an effort to mitigate impacts and reverse the degradation process. This provision represents an opportunity to develop participatory regeneration strategies that integrate the knowledge and needs of local communities, which could enhance the long-term effectiveness and sustainability of conservation efforts in these environments. Taking Ecuador as a reference, the country has implemented a Conservation Plan with Communities, which has allowed the protection of approximately 69,300 ha of mangroves [54]. The National Plan for the Conservation of Mangroves in Continental Ecuador (2019–2030) is a strategic effort aimed at protecting and restoring mangroves in Ecuador, promoting their sustainable management through community participation, scientific research, and multi-sectoral collaboration. A key measure of the plan is the “Mangrove Partner” program, which facilitates sustainable use agreements, allowing local communities to manage mangroves sustainably while obtaining economic benefits. This model is transferable to other regions, such as Chame Bay, where it could incentivize local conservation and income generation from sustainable practices, thus strengthening community resilience.

Figure 5.

Driving Forces-Pressure-State-Impact-Responses (DPSIR) model. This model reveals the causal relationships between human activities and the mangrove, making it possible to identify and analyze how driving forces (socioeconomic and cultural factors) exert pressure on the ecosystem, modifying its state and generating impacts that affect environmental health and human well-being. In turn, this approach facilitates the implementation of appropriate responses, focused on mitigating, preventing or remedying negative effects, promoting a more sustainable and effective mangrove management. Source: EcoShape, 2008.

The information provided by charcoal producers and agricultural producers is valuable for assessing community perception of mangrove regeneration, identifying challenges and opportunities in regeneration efforts, customizing communication and awareness strategies, measuring community engagement, and encouraging community participation.

Rhizophora mangle, L. racemosa, and A. germinans are species with commercial value for communities that produce charcoal and are extracted from the mangrove causing its degradation [42]. The greater participation of charcoal burners in restoration actions compared to farmers suggests that there are opportunities to promote mangrove restoration in both groups. This finding highlights the need to develop specific programs that not only maintain the interest of charcoal burners, but also encourage greater involvement of farmers. By creating strategies tailored to the characteristics and needs of each group, the success of restoration projects and the long-term sustainability of the ecosystem could be maximized. The involvement of charcoal producers in restoration actions suggests that there is a growing awareness and interest among this group in the importance of mangrove restoration. This could be indicative of a gradual [55] change in practices and values, as charcoal producers are directly linked to activities that may have negative impacts on mangroves. This involvement could be influenced by factors such as public opinion pressure, government regulations, or even awareness initiatives promoting environmental conservation.

This study highlighted the participation of farmers in mangrove restoration actions. Participation may be related to land use and proximity to mangrove areas. Participation in restoration activities is prominent among farmers, suggesting that there is a shared understanding of the importance of these actions. Of those who participated in restoration actions, the specific percentages of participation in the different activities (seed collection, mangrove planting, and nursery propagation) provide useful information on the preferences and capabilities of those involved. Participation in mangrove planting stands out as the most common activity, suggesting an understanding of the importance of strengthening the mangrove population for ecosystem health. Such is the case in El Palmar (Tabasco, Mexico) where community members planted R. mangrove propagules in an area of 160 ha under restoration [47]. On the other hand, seed collection and nursery propagation also show a significant degree of participation, indicating a commitment to the preservation of the mangrove life cycle. For example, the Mangroves of Colombia Project in its phase II has promoted community participation in the restoration of degraded mangrove areas [56], where a transplant of R. mangle from the Canal de Diques zone to the Barranca Zone in Colombia was carried out, the recovery has been successful in areas affected by high salinity [57].

Taken together, these results suggest that, although users may have more positive attitudes towards mangrove restoration, a continuous, multidisciplinary approach is required to reverse degradation. Although these activities could be seen as contradictory to their primary occupations, the willingness to participate and positive perceptions indicate that the ecological and socioeconomic importance of mangrove conservation has been successfully conveyed. For example, forest restoration with stakeholders in semi-arid areas of North Africa was conducted with knowledge sharing, mutual assistance, environmental education, and social solidarity, resulting, according to respondents, in learning new ideas in ecological restoration, erosion, and flood control [58]. These results also have implications for collaboration and inclusive restoration program design, as they seem to suggest that different sectors may have a common interest in mangrove protection.

In terms of user perception, the fact that there do not appear to be significant differences in relation to educational level and social interaction patterns is an important finding. This could indicate that the positive perception towards mangrove restoration is shared by a wide range of individuals, regardless of their educational level or social network. Within the process communities become active agents in the protection of their environment [21], generating a sense of responsibility [59]. The results suggest that awareness and support for mangrove conservation could be rooted in broader values and general appreciation of the ecological benefits provided by these ecosystems [60]. Active community participation in restoration ensures that care and monitoring of the area continues over time, contributing to the long-term sustainability of mangroves undergoing restoration [61].

The present study emerges as a significant contribution in the context of mangrove restoration in Central America, as it provides a deeper understanding of the perceptions and preferences of communities in mangrove areas with diverse social and economic contexts. The data collected reflect a diversity of opinions and needs in relation to mangrove restoration, providing a solid basis for the design of engagement and participation strategies that are truly inclusive and effective.

A key aspect highlighted by this study is the variability in community perceptions of mangrove conditions, causes of mangrove degradation, and preferences for restoration methods. The study conducted in southeastern Cuba highlights how local communities recognize the ecosystem services of mangroves, although they do not directly depend on them for their livelihoods. Perceptions of these services vary according to respondents’ occupation and locality, which is consistent with the importance of mangroves in coastal protection and local livelihoods through fishing and agriculture [38]. This variability correlates with the different social and economic contexts in which these communities find themselves. Therefore, the study recognizes that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to mangrove restoration and that it is essential to consider the particularities of each context.

In this sense, the results of the study provide guidance for the adaptation of restoration strategies to the specific conditions and perspectives of each community. For example, in areas where deforestation is identified as the main threat to mangroves, strategies may focus on promoting reforestation practices and raising awareness of the importance of conserving forest cover. In contrast, in places where agricultural activities are perceived as a threat, strategies could include the promotion of sustainable agricultural and livestock practices. This is consistent with the findings of [62], who noted that agricultural and aquaculture activities, along with anthropogenic pressures, are significant contributors to mangrove deforestation globally.

In addition, the study also highlights the need to actively involve the community in the planning and implementation of restoration actions. The acceptance of assisted regeneration by most respondents and the preference for mangrove species diversity in restoration provides valuable guidelines for the implementation of restoration projects with community support and participation.

Ultimately, the study highlights the importance of tailoring mangrove restoration strategies to the specific circumstances of each community and involving local stakeholders in the decision-making process. These findings will serve as a basis for the design of future restoration strategies that are socially inclusive and economically sustainable, thus contributing to the long-term preservation of mangroves in Central America.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the level of knowledge and perception that local communities and users of the mangroves of Chame Bay have about their ecological importance and the ecosystem services they provide was evaluated. The results show that, although the majority of respondents recognize the benefits of mangroves, there are differences in the depth of this knowledge, mainly linked to socio-demographic factors such as age, educational level, and professional sector.

In addition, the current involvement of farmers and charcoal producers in mangrove restoration actions has been analyzed. While both groups have shown interest in ecological restoration, farmers seem to be more willing to be actively involved in future regeneration processes. However, a portion of the charcoal producers showed a willingness to participate, which highlights the importance of integrating both groups in restoration efforts.

The relationship between sociodemographic variables and the perception and willingness to participate suggests that restoration strategies should be adapted to the particularities of each social group. The promotion of environmental education and the development of training programs may be key to increasing community participation in mangrove conservation.

This study highlights the need to actively involve local communities in mangrove management and restoration, recognizing the differences in knowledge and interests of different groups. The resulting recommendations provide a solid basis for designing more inclusive and effective restoration strategies that ensure the long-term sustainability of the Chame Bay mangroves.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, R.J.D.C.-A.; Writing—review & editing, O.R.L., P.M.R.-G. and J.F.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) funded the Forest Research Centre through project UIDB/00239/2020 and Associate Laboratory TERRA through funding LA/P/0092/2020.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

This study has been conducted in the frame of the International Doctorate in Agriculture and Environment for Development (DIAMD) made up of more than 20 institutions from more than 10 Spanish and Portuguese-speaking countries, coordinated by University of Santiago de Compostela. The Panama Institute for Agricultural Innovation for the collaboration with the technical and logistical team in the study of Chame Bay. The Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) funded the Forest Research Centre through project UIDB/00239/2020 and Associate Laboratory TERRA through funding LA/P/0092/2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Spalding, M.; Kainuma, M.; Collins, L. World Atlas of Mangroves; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 319–336. [Google Scholar]

- López, M.R. Mangroves: Biodiversity Safeguards and Silent Heroes in the Face of Climate Change; Institute of Oceanography, FURG: Rio Grande, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Balvanera, P.; Cotler, H. Acercamiento al estudio de los servicios ecosistémicos. Gac. Ecológica 2007, 84, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Valdez, V.; Ruiz-Luna, A. Marco conceptual y clasificación de los servicios ecosistémicos. Revista Bio Ciencias 2012, 1, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- ONU; Proyecto de Bosques Azules; Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente. Enfoque de Conservación del Ecosistema Costero y Promover el Financiamiento de Carbono con Base en los Manglares; ONU: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Le Heron, R.; Lundquist, C.; Logie, J.; Blackett, P.; Le Heron, E.; Awatere, S.; Hyslop, J. A soio-ecological appraisal of perceived ricks associated with mangrove (Mãnawa) management in Aotearoa New Zealand. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2022, 56, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermgassen, P.; Worthington, T.A.; Gair, J.R.; Garnett, E.E.; Mukherjee, N.; Longley-Wood, K.; Nagelkerken, I.; Abrantes, K.; Aburto-Oropeza, O.; Acosta, A.; et al. The global fish and invertebrate abundance value of mangroves. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, V.J.E. Las Mariposas Diurnas (Insecta: Lepidóptera: Papilionoidea) del Manglar de Tumilco en Tuxpan; Universidad Veracruzana: Veracruz, México, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Verdugo, F.; Moreno-Casasola, P.; Agraz, H.C.; López, R.H.; Benítez, P.D.; Travieso, B.A. La topografía y el hidroperiodo: Dos factores que condicionan la restauración de los humedales costeros. Bol. Soc. Bot. Méx. 2007, 80, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangoko, B.; Berg, H.; Mangora, M.M.; Shalli, M.S.; Gullström, M. Community perceptions of climate change and ecosystem-based adaptation in the mangrove ecosystem of the Rufiji Delta, Tanzania. Clim. Dev. 2022, 14, 896–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo, J.M.D.; Uchiyama, Y.; Kohsaka, R. Perceptions of local communities on mangrove forests, their services and management: Implications for Eco-DRR and blue carbon management for Eastern Samar, Philippines. J. For. Res. 2020, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.A.; Berry, P.M.; Simpson, G.; Haslett, J.R.; Blicharska, M.; Bucur, M.; Dunford, R.; Egoh, B.; GarciaLiorente, M.; Geamana, N.; et al. Linkages between biodiversity attributes and ecosystem services: A systematic review. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 9, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nju Enoh, C.A.; Ambo, F.B. Economic and environmental implication of Wood explotation in the mangrove ecosystem in Tiko, South West Region of Cameroon. J. Geogr. Environ. Earth Sci. Int. 2024, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aye, W.N.; Wen, Y.; Marin, K.; Thapa, S.; Tun, A.W. Contribution of Mangrove Forest to the Livelihood of Local Communities in Ayeyar waddy Region, Myanmar. Forests 2019, 10, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol-Sánchez, A.; Hernández-Melchor, G.I.; Hernández-Hernández, M. Bioeconomic development and mangroves in Latin America. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua. Rev. Iberoam. De Bioeconomía Y Cambio Climático 2022, 8, 2007–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Capítulo 6: América del Norte y Central. In The World’s Mangroves 1980–2005; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2007; ISBN 978-92-5-105856-5. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Mejía, M.A.; Aguirre Vallejo, A.; Flores Hernández, M.; Guardado Govea, X. El impacto que produce el sector turismo en los manglares de las costas mexicanas. Contactos 2010, 77, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Spalding, M.; Kainuma, M.; Collins, L.; Blasco-Takali, F.; Blasco, F. World Atlas of Mangroves; International Society for Mangrove Ecosystems c/o Faculty of Agriculture, University of the Ryukyus: Okinawa, Japan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- CONFOREC. Plan de Manejo de los Manglares de la Bahía de Chame. Proyecto de Conservación y Repoblación de Áreas Amenazadas del Bosque de Manglar del Pacífico Panameño (ANAM-OIMT); CONFOREC: Panamá, Panamá, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- ANAM-ARAP. Manglares de Panamá. Importancia, Mejores Prácticas y Regulaciones Vigentes; Andrés Tarté: Panamá, República de Panamá, 2013; Available online: https://lac.wetlands.org/publicacion/manglares-de-panama-importancia-mejores-practicas-y-regulaciones-vigentes/ (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Pesci, R.; Pérez, J.; Pesci, L. Proyectar la Sustentabilidad. Enfoque y Metodología de FLACAM Para Proyectos de Sustentabilidad; Editorial CEPA: La Plata, Argentina, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cahyaningsih, A.P.; Deanova, A.K.; Pristiawati, C.M.; Ulumuddin, Y.I.; Kusumaningrum, L.; Setyawan, A.D. Causes and impacts of anthropogenic activities on mangrove deforestation and degradation in Indonesia. Intl. J. Bonorowo Wetl. 2022, 12, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiela, I.; Bowen, J.L.; York, J.K. Mangrove Forests: One of the World’s Threatened Major Tropical Environments. BioScience 2001, 51, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, J.; Urrego, L.E. Environmental management of mangrove ecosystems. An approach for the Colombian case. Rev. Gestión Y Ambiente 2009, 12, 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hirales-Cota, M.; Espinoza-Avalos, J.; Schmook, B.; Ruiz-Luna, A.; Ramos-Reyes, R. Drivers of mangrove deforestation in Mahahual-Xcalak, Quintana Roo, southeast Mexico. Cienc. Mar. 2010, 36, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANAM. Gaceta Oficial, Resolución AG 0364, por Medio del cual se crea el Área Protegida Manglares de la Bahía de Chame, República de Panamá; Autoridad Nacional del Ambiente, Panamá, 2009; Available online: https://www.gacetaoficial.gob.pa/pdfTemp/26301/GacetaNo_26301_20090611.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Gann, G.D.; McDonald, T.; Walder, B.; Aronson, J.; Nelson, C.R.; Jonson, J.; Hallett, J.G.; Eisenberg, C.; Guariguata, M.R.; Liu, J.; et al. International principles, and standards for the practice of ecological restoration. second edition. Restor Ecol. 2019, 27, S1–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, E. The two-culture problem: Ecological restoration and the integration of knowledge. Restor. Ecol. 2005, 13, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanturf, J.A.; Palik, B.J.; Dumroese, R.K. Restauración forestal contemporánea: Una revisión que enfatiza la función. Bosque Ecol. Y Gestión 2014, 331, 292–323. [Google Scholar]

- Uprety, Y.; Asselin, H.; Bergeron, Y.; Doyon, F.; Boucher, J.F. Contribution of traditional knowledge to ecological restoration: Practices and applications. Ecoscience 2012, 19, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meli, P.; Ceccon, E.; Mastragelo, M.; Calle Días, Z. Ecosystem restoration and human well-being in Latin America. Ecosyst. People 2022, 18, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Delgado, E. Coastal Restoration Challenges and Strategies for Small Island Developing States in the Face of Sea Level Rise and Climate Change. Coast 2024, 4, 235–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANAM. Informe del Componente de Manglar, Región de Panamá Oeste. Proyecto de Conservación y Repoblación de Áreas Amenazadas del Bosque de Manglar del Pacífico Panameño; José Berdiales: Panamá, Panamá, 2009; Available online: https://www.itto.int/files/itto_project_db_input/2457/Competition/pd156-02-p3%20rev2(F)_Proyecto%20de%20Conservacion%20y%20Repoblacion%20de%20Areas%20Amenazadas_S.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Berdiales, J.; Chavarría, J. Informe del Componente de Manglar, Región de Panamá Oeste; Organización de Maderas Tropicales (OIMT)–Autoridad Nacional del Ambiente (ANAM): Panamá, Panamá, 2009; 47p. [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washintong, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. Regulations of the National Research Bioethics Committee of Panama; Executive Decree No. 1843; Ministry of Health: Panamá, Republic of Panama, 2014; Available online: https://cnbi.senacyt.gob.pa/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Decreto-Ejecutivo-N1843-del-16-de-diciembre-de-2014-unificado.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Vaca, I. Oportunidades y desafíos Para la Autonomía de las Mujeres en el Futuro Escenario del Trabajo; Serie Asuntos de Género, N° 154 (LC/TS.2019/3); Santiago, Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL): Santiago, Chile, 2019; Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/edc6e8c4-d873-4ad7-a069-1a4a260ca8c1/content (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Cruz-Portorreal, Y.; Beenaerts, N.; Koedam, N.; Reyes Dominguez, O.J.; Milanes, C.B.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F.; Pérez Montero, O. Perception of Mangrove Social–Ecological System Governance in Southeastern Cuba. Water 2024, 16, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteve-Volart, B. Gender Discrimination and Growth: Theory and Evidence from India; London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, G.E. Centro urbanos de América Latina 1997, 2006: Disparidades Salariales Según Género y Crecimiento Económico. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, (131.132); Universidad Nuestra Señora del Rosario: Bogotá, Colombia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, K. Social theory anew: From contesting modernity to revisiting ou conceptual toolbox—The case of individualization. Curr. Sociol. 2021, 69, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANAM–OIMT. Proyecto de Conservación y Repoblación de Áreas Amenazadas del Bosque de Manglar del Pacífico Panameño; CONFOREC, S.A. República de Panamá. 2007. Available online: https://www.itto.int/files/itto_project_db_input/2457/Technical/Informe%20de%20Plan%20de%20Manejo_Version%202.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- ONU. El papel de la economía y el comercio de servicios en la transformación estructural y el desarrollo inclusivo. In Proceedings of the Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre Comercio y Desarrollo. Reunión multianual de Expertos sobre Comercio, Servicios y Desarrollo, Quinto Período de Sesiones, Ginebra, Switzerland, 18–20 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J. Recursos Naturales, Medio Ambiente y Sostenibilidad: 70 Años de Pensamiento de la CEPAL; Libros de la CEPAL, N° 158 (LC/PUB.2019/18-P); Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL): Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.; Hassan, L.; Abdullah-Al, M.; Mustafa-Kamal, A.H.; Hanafi-Idris, M.; Ziaul-Hoque, M.; Mahmoood, R.; Alam, M.N.; Ali, A. Human intervention caused massive destruction of the second largest mangrove forest, Chakaria Sundarbans, Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Pollut. 2024, 31, 25329–25341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo, J.M.D.; Uchiyama, Y.; Kohsaka, R. 2022. Community perceptions of long-term mangrove cover changes and its drivers from a typhoon-prone province in the Philippines. Ambio 2022, 51, 972–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ruíz, P.A.; Betancourth-Buitrago, R.A.; Arteaga-Cote, M.; Carbajal-Borges, J.P.; Teutli-Hernández, C.; Laffonn-Leal, S. Fostering a Participatory Process for Ecological Restoration of Mangroves in Pantanos de Centla Biosphere Reserve (Tabasco, Mexico). Ecosyst. People 2022, 18, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teutli-Hernández, C.; Herrera-Silveira, J.A.; Cisneros-de la Cruz, D.J.; y Roman-Cuesta, R. Guía Para la Restauración Ecológica de Manglares: Lecciones Aprendidas. Proyecto Mainstreaming Wetland into the Climate Agenda: A Multi-Level Approach (SWAMP); CIFOR/CINVESTAV-IPN/UNAM-Sisal/PMC: Yucatán, México, 2020; 42p, Available online: https://www.cifor-icraf.org/publications/pdf_files/Books/2020-Guia-SWAMP.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J.A.; Mancera-Pineda, J.E.; Tabera, H. Mangrove restoration in Colombia: Trends and lessons learned. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 496, 119414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Silveira, J.A.; Teutli-Hernández, C.; Cinco-Castro, S.; Ramirez-Ramirez, J.; Carrillo Baeza, L.; Pech-Poot, E.; Pérez-Martínez, O.; Zenteno-Díaz, K.; Erosa-Angulo, J.; Us-Balam, H.; et al. Red Multi-Institucional. Programa Regional para la Caracterización y el Monitoreo de Ecosistemas de Manglar del Golfo de México y Caribe Mexicano: Península de Yucatán. Segunda Etapa. Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados-Mérida. Ecosistemas Costeros de la Península de Yucatán; Informe final SNIB-CONABIO, Proyecto No. KN003. Merida, Ciudad de México, 2018. Available online: http://www.conabio.gob.mx/institucion/proyectos/resultados/InfFN009.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Vilela, J.J. Sensibilización Sobre la Importancia del Manejo de Desechos de Estopa de Cocotero Frente al Cambio Climático. Caso de Estudio Manglar de la REMACAM, en las Comunidades Pampanal de Bolivar y Tambillo; Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, FLACSO: Quito, Ecuador, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer-Novelli, Y.; Spalding, M.; Vander-Stocken, T.; Wodehouse, D.; Yong, J.W.H.; Zimmer, M.; Friess, D.A. Public Perceptions of Mangrove Forests Matter for Their Conservation. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 603651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, M.D.; McIvor, A.L.; Beck, M.W.; Koch, E.W.; Möller, I.; Reed, D.J.; Rubinoff, P.; Spencer, T.; Trevor, J.; Tolhurst, T.; et al. Coastal ecosystems: A critical element of risk reduction. Conserv. Lett. 2013, 7, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, R.; Santillán, X. Plan de Acción Nacional Para la Conservación de los Manglares del Ecuador Continental. Ministerio de Ambiente de Ecuador, Conservación Internacional Ecuador, Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura (UNESCO) y la Comisión Permanente del Pacífico Sur (CPPS); Proyecto Conservación de Manglar en el Pacífico Este Tropical: Guayaquil, Ecuador, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Macamo, C.C.F.; Ináciode Costa, F.; Bandeira, S.; Adams, J.B.; Balidy, H.J. Mangrove community-based management in Eastern Africa: Experiences from rural Mozambique. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1337678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Páez, H.; Ulloa-Delgado, G. Experiencias de restauración en el Proyecto Manglares de Colombia; Ponce de León, E., Ed.; Mem.Sem.Sem.Nal de Restauración Ecológica y Reforestación, FAAE/FESCOL/FNA/GTZ: Santa Fé de Bogotá, Colombia, 2000; pp. 219–258. [Google Scholar]

- Grosso-Vargas, J.; Sánchez-Arias, L.; Restrepo, R. y Avendaño, D. Control de la Salinidad en Efluentes Líquidos en Campos de Producción de Petróleo Mediante la Utilización de Manglares (R. mangle, L. racemosa y A. germinans); ICP-ECOPETROL/BIOSFERA: Bogotá, Colombia, 1995; pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Derak, M.; Cortina, J.; Taiqui, L.; Aledo, A. A proposed framework for participatory forest restoration in semiarid areas of North Africa. Restor. Ecol. 2018, 26, S18–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccon, E.; Méndez-Toribio, M.; Martínez-Garza, C. Social participation in forest restoration projects: Insights from a national assessment in Mexico. Hum. Ecol. 2020, 48, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián-Piqueras, M.; Filyushkina, A.; Johnson, D.; López-Rodríguez, M.; March, H.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Peppler-Lisbach, C.; Quintas-Soriano, C.; Raymond, C.; Ruiz-Mallén, I.; et al. Scientific and local ecological knowledge, shaping perceptions towards protected areas and related ecosystem services. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 35, 2549–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, D.; Merino-Pérez, L. The Rise of Community Forestry in Mexico: History, Concepts, and Lessons Learned from Twenty-Five Years of Community Timber Production; A Report in partial fulfillment of Grant No. 1010-0595; The Ford Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmik, A.K.; Padmanaban, R.; Cabral, P.; Romeiras, M.M. Global Mangrove Deforestation and Its Interacting Social-Ecological Drivers: A Systematic Review and Synthesis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).