Influence of Livelihood Capitals on Landscape Service Cognition and Behavioral Intentions in Rural Heritage Sites

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How do farmers with different livelihood strategies differ in their cognition of landscape services and behavioral intentions?

- (2)

- What are the specific pathways through which different types of livelihood capital influence landscape service cognition and behavioral intentions?

- (3)

- Does landscape service cognition mediate the relationship between livelihood capital and farmers’ behavioral intentions?

2. Research Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Research Framework

2.2. Research Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Questionnaire Design

- Basic Socioeconomic Characteristics of the Respondents: This consisted of education level, household size, etc.

- Livelihood Capital Status of the Respondents: This aspect examines various types of capital, including human capital, natural capital, physical capital, financial capital, social capital, and cultural capital.

- Respondents’ Cognition of Landscape Services in the Area: Respondents are asked to evaluate their awareness and understanding of landscape services based on their own perceptions.

- Behavioral Willingness of the Respondents: This consisted of willingness to participate, willingness to protect, and willingness to promote.

3.3. Variable Selection and Measurement

- Independent Variable (IV): Farmers’ livelihood capital, which includes 12 indicators across six dimensions: human capital, natural capital, physical capital, financial capital, social capital, and cultural capital.

- Mediating Variable (MV): Farmers’ cognition of landscape services, comprising 11 measurement indicators within four dimensions: ecology, production, society, and landscape culture.

- Dependent Variable (DV): Farmers’ behavioral intentions, which include three dimensions: willingness to participate, willingness to protect, and willingness to publicize, totaling 11 items.

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive and Analysis

4.2. Differences in Landscape Service Cognition Among Farmers with Different Livelihood Strategies

4.3. Differences in the Behavioral Intentions Among Farmers with Different Livelihood Strategies

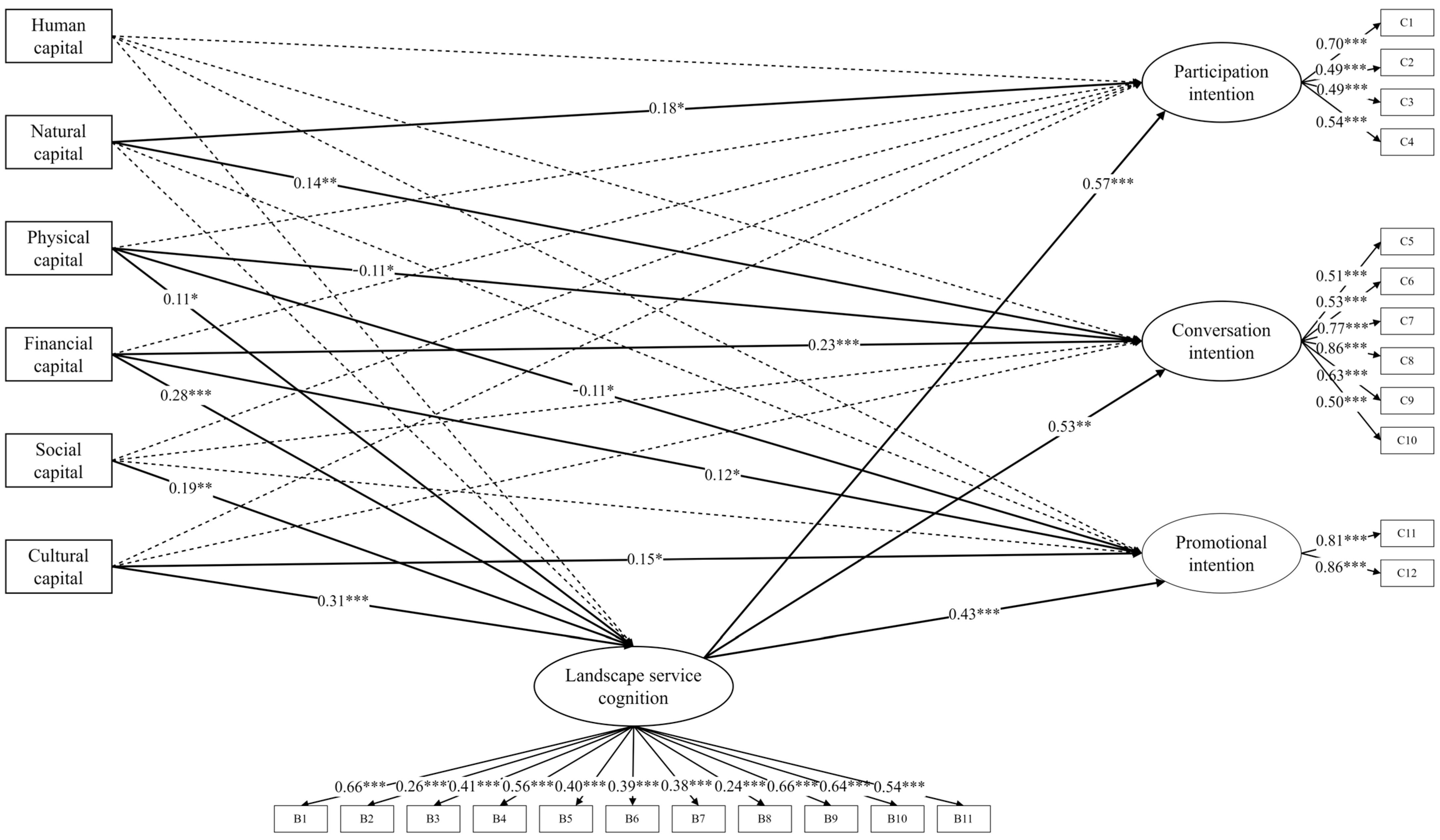

4.4. Results of Structural Equation Model Regression

5. Discussion

5.1. Differences in Landscape Service Cognition and Behavioral Intentions Among Farmers with Different Livelihood Strategies

5.2. The Impact of Farmers’ Livelihood Capital and Landscape Service Cognition on Behavioral Intentions

5.3. Policy Recommendations

- (1)

- Promoting the Synergistic Development of Cultural and Financial Capital.

- (2)

- Enhancing Livelihood Capital to Improve Landscape Service Cognition.

- (3)

- Differentiated Strategies for Farmers with Different Livelihood Strategies.

5.4. Limitations and Future Works

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The normalized levels of human capital (0.541), social capital (0.671), and cultural capital (0.645) are relatively high among farmers in the study area, while the levels of natural capital, physical capital, and financial capital are comparatively low.

- (2)

- Diversified livelihood farmers exhibit the highest levels of overall landscape service cognition and behavioral intentions. They stand out in their recognition of ecological and cultural services and demonstrate a strong enthusiasm for participating in ecological agriculture and the handicrafts and processing industries. In contrast, subsidy-dependent farmers have the lowest level of behavioral intentions.

- (3)

- Natural capital, financial capital, and cultural capital play key roles in influencing farmers’ landscape service cognition and behavioral intentions. Additionally, landscape service cognition mediates the relationship between livelihood capital and farmers’ behavioral intentions.

- (4)

- To enhance farmers’ willingness to protect rural heritage, the focus should be on improving and accumulating natural, physical, and financial capital. In contrast, to increase farmers’ willingness to promote rural heritage, the accumulation of cultural capital is particularly crucial.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1992; IDS Discussion Paper No. 296. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Gao, M.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Shi, Y. Study on identification of rural settlement heritage aggregation areas in China and its spatial pattern. J. Urban Reg. Plan. 2023, 15, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.C.; Calla, S.; Lécuyer, L. Just and sustainable transformed agricultural landscapes: An analysis based on local food actors’ ideal visions of agriculture. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 342, 108236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csurgó, B.; Smith, M.K. The value of cultural ecosystem services in a rural landscape context. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 86, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, N.; Xie, X. On the efficiency and influencing factors of farmers’ tourism livelihood in world heritage site: A case study of Danxia Mt. in Guangdong Province. Sci. Technol. Manag. Land Resour. 2021, 37, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G.; Wang, Y. Integrating tea and tourism: A sustainable livelihoods approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1591–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bires, Z.; Raj, S. Tourism as a pathway to livelihood diversification: Evidence from biosphere reserves, Ethiopia. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, M.; Min, Q.; Li, W. Specialization or diversification? The situation and transition of households’ livelihood in agricultural heritage systems. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2018, 16, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, J.; Wang, Y. Effects of Livelihood Capital on the Farmers’ Behavioral Intention of Rural Residential Land Development Right Transfer: Evidence from Wujin District, Changzhou City, China. Land 2023, 12, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, H.; Byres, T.J. From Peasant Studies to Agrarian Change. J. Agrar. Change 2001, 1, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Li, H.; Min, Q. Value and conservation actors of Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (IAHS) from the perspective of rural households. Resour. Sci. 2020, 42, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Liu, W.; Xiong, C.; Bai, X. Value Transformation and Ecological Practice: The Path to Realizing the Value of Ecotourism Products in Heritage Sites—A Case Study of the Qitai Dry Farming System in Xinjiang. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Min, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, M.; Xiong, Y. Analysis on the rural households aiming at the conservation of agricultural heritage system. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2017, 27, 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1998; IDS Working Paper No. 72. [Google Scholar]

- DFID. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; DFID: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, M.C. An integrated approach to assess the impacts of tourism on community development and sustainable livelihoods. Community Dev. J. 2009, 44, 186–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zheng, H.; Wang, X.; Peng, W.; Ma, D.; Li, C. Classification of the Relationship between Household Welfare and Ecosystem Reliance in the Miyun Reservoir Watershed, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, M.; Min, Q.; He, S.; Jiao, W. Review of eco-environmental effect of farmers’ livelihood strategy transformation. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 8172–8182. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. Social Networks, Perceived Value and Farmers’ Behavior of Cultivated Land Quality Protection. Ph.D. Thesis, Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University, Xianyang, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. Mainstreaming Ecosystem Service Trade-Offs into Farmland Use and Livelihood Strategies. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University: Hangzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, J.; Liu, Y.; Gao, L. Research on the relationship between fishermen’s willingness to exit fishing and sustainable livelihood capitals in the Yangtze River Basin: Based on survey data from the Poyang Lake Area. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2022, 42, 196–205. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F.; Ouyang, C.; Xu, X.; Jia, Y. Study on farmers’ willingness to change livelihood strategies under the background of rural tourism. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 30, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Halder, P.; Zhang, X.; Qu, M. Analyzing the deviation between farmers’ Land transfer intention and behavior in China’s impoverished mountainous Area: A Logistic-ISM model approach. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, Y. Farmers’ Cognition and Behavioral Response towards Cultivated Land Quality Protection in Northeast China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhao, M. The influence of environmental concern and institutional trust on farmers’ willingness to participate in rural domestic waste treatment. Resour. Sci. 2019, 41, 1500–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, J.; Zhao, P.; Chen, K.; Wu, L. Factors affecting the willingness of agricultural green production from the perspective of farmers’ perceptions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 738, 140289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Qiao, D.; Hao, Q.; Ji, Y.; Chen, D.; Xu, T. Gap between knowledge and action: Understanding the consistency of farmers’ ecological cognition and green production behavior in Hainan Province, China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, G. How does livelihood capital affect farmers’ pro-environment behavior? Mediating effect based on value perception. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2021, 20, 610–620. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, X.; Liu, Y.; Peng, W. The association of farmers’ cognition, intention and behaviour towards sustainable intensification of cultivated land use in Shandong Province, China. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2024, 22, 2318930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H. Understanding rural landscape for better resident-led management: Residents’ perceptions on rural landscape as everyday landscapes. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; He, G. The mechanism and empirical study of livelihood capital’s impact on the differentiation of farmers in mountainous area under SLA framework—A case study of farmers in Guangxi mountainous area. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2021, 42, 144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; Wu, X. The impacts of rural tourism on the vulnerability of farmers’ livelihood: From the perspective of coupled social-ecological system. Res. Agric. Mod. 2018, 39, 654–664. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; He, S.; Min, Q.; Sun, Y. Influence of traditional ecological awareness of rural households on tourism livelihood options in agricultural heritage sites. Tour. Trib. 2024, 39, 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z.; Zhang, H. Research on social, norms, environmental regulations and farmers’ fertilization behavior selection. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2021, 42, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fleig, L.; Ngo, J.; Román, B.L.; Ntzani, E.E.; Satta, P.; Warner, L.M.; Schwarzer, R.; Brandi, M.L. Beyond single behaviour theory: Adding cross-behaviour cognitions to the health action process approach. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 824–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Hu, W.; Li, G. Mechanism of rural land landscape cultural value co-creation: Scenario, cognitions, and farmers’ behavior. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Li, Z.; Xun, L.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Chen, X. Relationship between residents’ place perception, place attachment and protection attitude: A case study of typical Dike-pond agricultural village in Foshan City. Areal Res. Dev. 2023, 42, 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, A.J.; Ryan, R.L. Place attachment and landscape preservation in rural New England: A Maine case study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 86, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhou, K.; Chen, X. Influence of Livelihood Capital of Rural Reservoir Resettled Households on the Choice of Livelihood Strategies in China. Water 2022, 14, 4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, C.; Ren, W.; Wang, X. Study on the Landscape Multifunctionality and Multi-subject Game in the Fuzhou West Lake Water Heritage. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 39, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Wang, R.; Dai, M.; Ou, Y. The influence of culture on the sustainable livelihoods of households in rural tourism destinations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1235–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y. Reclamation and Irrigation: Researching on History of Farmland Water Conservancy in Ancient Putian (627-1850); Nanjing Agricultural University: Nanjing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, L.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Y. The relationship between livelihood capital, multi-functional value perception of cultivated land and farmers’ willingness to land transfer: A regional observations in the period of poverty alleviation and rural revitalization. China Land Sci. 2022, 36, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Pellegrini, P.; Wang, H. Comparative Residents’ Satisfaction Evaluation for Socially Sustainable Regeneration—The Case of Two High-Density Communities in Suzhou. Land 2022, 11, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, F.; Ji, T.; Xin, K. Differences in livelihood resilience of farm households in the Yellow River Basin under the background of livelihood strategies and its influencing factors: Taking Henan Province as an example. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 44, 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, H.; He, F.; Zhou, G.; Zou, M. Evaluation of the sustainable livelihood of farming households in traditional village tourism area: A case study of four typical traditional villages in Chenzhou City, Hunan Province. Prog. Geogr. 2023, 42, 884–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yin, K. Impact of part-time farmer households’ characteristics on farmer decision—Based on asurvey of 715 households in three gorges reservoir. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2015, 31, 1510–1514. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D.; Huang, X.; Wang, C. Farmers’ livelihood resilience and its optimization strategy in Loess Plateau of north Shaanxi province. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, Y.; Yu, X.; Bakker, M.; De Groot, R.; Carsjens, G.J.; Duan, H.; Huang, C. Analysis of the relationship between cross-cultural perceptions of landscapes and cultural ecosystem services in Genheyuan region, Northeast China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 43, 101112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Lan, H.; Xue, B. Dependence of farmers’livelihoods on environmental resource in key ecological function area: A case study of Gannan Plateau, China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 31, 554–562. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, A.; Wei, Y.; Zhong, F.; Wang, P. How do climate change perception and value cognition affect farmers’ sustainable livelihood capacity? An analysis based on an improved DFID sustainable livelihood framework. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferse, S.C.A.; Liu, W.; Vogt, C.A.; Luo, J.; He, G.; Frank, K.A.; Liu, J. Drivers and Socioeconomic Impacts of Tourism Participation in Protected Areas. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35420. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.; Lei, H.; Ren, H. Livelihood Capital, Ecological Cognition, and Farmers’ Green Production Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y. Impact of livelihood capital and rural site conditions on livelihood resilience of farm households: Evidence from contiguous poverty–stricken areas in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 123808–123826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Fang, C.; Qiu, D.; Wang, L. Impact of farmer households’ livelihood assets on their options of economic compensation patterns for cultivated land protection. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sang, Y.; Zhang, A. How livelihood capital affects farmers’ willingness to pay for farmland non-market value? Evidence from Jianghan Plain, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 51456–51468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Cheng, W. Study on the impact of livelihood capital on farmers’ willingness of homestead exit—An empirical analysis based on ordered logit model in Dingxi City. Nat. Resour. Econ. China 2023, 36, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Xu, F.; Liu, Y.-M.; Pu, L.-J.; Liu, L.-Y.; Xu, Y. Analysis on farmers’ behavioral intension of cropland use and its influencing factors in the coastal areas of Northern Jiangsu province. J. Nat. Resour. 2022, 37, 1643–1653. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.; Sun, Y.; Min, Q.; Jiao, W. A Community Livelihood Approach to Agricultural Heritage System Conservation and Tourism Development: Xuanhua Grape Garden Urban Agricultural Heritage Site, Hebei Province of China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Tian, W.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S. Environmental regulation, high-quality economic development and ecological capital utilization. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1325289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, G. Impact of Agricultural Cooperatives on Farmers’ Collective Action: A Study Based on the Socio-Ecological System Framework. Agriculture 2024, 14, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Shuai, C.; Shuai, Y.; Cheng, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, F. How Livelihood Assets Contribute to Sustainable Development of Smallholder Farmers. J. Int. Dev. 2020, 32, 408–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Livelihood Capital | Indicator | Magnitude Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Human capital | Education level (A1) | Illiteracy = 1; Elementary school and below = 2; Junior high school = 3; High school/technical secondary school = 4; Junior college/higher vocational college and above = 5 |

| Proportion of household labor force (A2) | 0~≤1/5 = 1; 1/5~≤2/5 = 2; 2/5~≤3/5 = 3; 3/5~≤4/5 = 4; 4/5~≤1 = 5 | |

| Natural capital | Household cropland area (A3) | 0~≤1 mu = 1; 1~≤2 mu = 2; 2~≤3 mu = 3; 3~≤4 mu = 4; >4 mu = 5 |

| Water and fertilizer conditions of cropland (A4) | Very poor = 1; Poor = 2; Neutral = 3; Good = 4; Very good = 5 | |

| Physical capital | Types of household appliances (A5) | 0 ~ 2 items = 1; 3 ~ 4 items = 2; 5 ~ 6 items = 3; 7 ~ 8 items = 4; More than 8 items = 5 |

| Types of residential housing (A6) | Old house = 1; Renovated old house = 2; Refurbished house = 3; Newly built house = 4 | |

| Financial capital | Household savings status (A7) | 30,000~60,000 yuan = 1; 60,000 to 100,000 yuan = 2; 100,000 to 300,000 yuan = 3; 300,000 to 500,000 yuan = 4; More than 500,000 yuan = 5 |

| The difficulty of lending money to others (A8) | Very difficult = 1; Difficult = 2; Average = 3; Easy = 4; Very easy = 5 | |

| Social capital | The closeness with relatives and friends (A9) | Never interact = 1; Rarely interact = 2; Occasionally interact = 3; Fairly often interact = 4; Frequently interact = 5 |

| Willingness to participate in village activities (A10) | Never participate = 1; Occasionally participate passively = 2; Occasionally participate actively = 3; Frequently participate = 4; Lead participation = 5 | |

| Cultural capital | The level of understanding of folklore (A11) | Not familiar at all = 1; Slightly unfamiliar = 2; Neutral = 3; Somewhat familiar = 4; Very familiar = 5 |

| The degree of recognition of rural cultural values (A12) | Do not approve at all = 1; Somewhat disapprove = 2; Neutral = 3; Somewhat approve = 4; Strongly approve = 5 |

| Variable Setup | Magnitude Definition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape service cognition | Climate regulation | The climate here is comfortable and pleasant (B1) | 1 = Strongly disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neutral 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly agree |

| Storm-water management | There is no risk of flooding here (B2) | ||

| Freshwater supply | The water quality here is excellent (B3) | ||

| Habitat maintenance | There is a great diversity of species here (B4) | ||

| Food supply | There is a large production of grains, vegetables, and fruits here (B5) | ||

| Residential support | There are many people living here (B6) | ||

| Employment security | There are many ways to earn money here (B7) | ||

| Transportation | The transportation here is very convenient (B8) | ||

| Cultural value | The culture here makes me feel proud (B9) | ||

| Landscape aesthetics | The scenery here is beautiful (B10) | ||

| Recreation and leisure | This place meets the needs for recreation and leisure (B11) | ||

| Behavioral Intentions | Participation intention | Support eco-agriculture and leisure tourism for rural heritage conservation. (C1) | 1 = Strongly unwilling 2 = Unwilling 3 = Neutral 4 = Willing 5 = Strongly willing |

| Invest time/funds in eco-agriculture. (C2) | |||

| Invest time/funds in handicrafts and processing. (C3) | |||

| Invest time/funds in tourism. (C4) | |||

| Conservation intention | The overall willingness to protect the Mulanbei rural heritage. (C5) | ||

| Actively engage in environmental protection. (C6) | |||

| Accept industrial land transition subsidies to protect rural heritage. (C7) | |||

| Embrace farmland transfer benefits for heritage. (C8) | |||

| Rent and renovate idle homes for preservation. (C9) | |||

| Donate to protect rural heritage. (C10) | |||

| Promotion intention | Participate in local cultural promotions. (C11) | ||

| Encourage others to preserve rural characteristics. (C12) | |||

| Livelihood Strategies | Quantity (Household) | Proportion (%) | Living Mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diversified livelihood | 39 | 11.1 | Mainly to civil servants, public institutions (including village cadres) |

| Wage-operated | 149 | 42.6 | Enterprise employees, engaging in handicrafts, processing, tourism, commerce, etc. |

| Purely agricultural | 82 | 23.4 | Mainly farming |

| Labor-led | 52 | 14.9 | Mainly for workers |

| Subsidy-dependent | 28 | 8 | Other (mostly retired, unemployed) |

| Dimension | Cronbach’ s α | KMO |

|---|---|---|

| Landscape service cognition | 0.773 | 0.819 |

| Participation intention | 0.686 | 0.648 |

| Conservation intention | 0.815 | 0.780 |

| Promotion intention | 0.826 | 0.500 |

| Dimension Fit Index | Recommended Value | Fit Value |

|---|---|---|

| X2 | The smaller the better | 860.531 |

| X2/df | <3.0 | 2.502 |

| GFI | >0.9 | 0.853 |

| AGFI | >0.8 | 0.814 |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | 0.066 |

| Hypothesis | Path Relationship | Estimated Value | S.E. | C.R | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Human capital → Participation intention | 0.090 | 0.630 | 1.423 | 0.155 | Not accept |

| H1b | Human capital → Conservation intention | 0.048 | 0.029 | 1.626 | 0.104 | Not accept |

| H1c | Human capital → Promotion intention | 0.018 | 0.057 | 0.321 | 0.749 | Not accept |

| H1d | Natural capital → Participation intention | 0.128 | 0.046 | 2.794 | * | Accept |

| H1e | Natural capital → Conservation intention | 0.056 | 0.022 | 2.593 | ** | Accept |

| H1f | Natural capital → Promotion intention | 0.003 | 0.041 | 0.063 | 0.950 | Not accept |

| H1g | Physical capital → Participation intention | −0.002 | 0.062 | −0.033 | 0.973 | Not accept |

| H1h | Physical capital → Conservation intention | −0.063 | 0.030 | −2.112 | * | Accept |

| H1i | Physical capital → Promotion intention | −0.110 | 0.057 | −2.090 | * | Accept |

| H1j | Financial capital → Participation intention | 0.081 | 0.060 | 1.342 | 0.180 | Not accept |

| H1k | Financial capital → Conservation intention | 0.112 | 0.030 | 3.724 | *** | Accept |

| H1l | Financial capital → Promotion intention | 0.113 | 0.055 | 2.069 | * | Accept |

| H1m | Social capital → Participation intention | 0.070 | 0.058 | 1.189 | 0.234 | Not accept |

| H1n | Social capital → Conservation intention | −0.008 | 0.028 | −0.276 | 0.783 | Not accept |

| H1o | Social capital → Promotion intention | 0.059 | 0.054 | 1.089 | 0.276 | Not accept |

| H1p | Cultural capital → Participation intention | 0.051 | 0.070 | 0.724 | 0.469 | Not accept |

| H1q | Cultural capital → Conservation intention | −0.052 | 0.033 | −1.546 | 0.122 | Not accept |

| H1r | Cultural capital → Promotion intention | 0.150 | 0.070 | 2.127 | * | Accept |

| H2a | Human capital → Landscape service cognition | 0.016 | 0.040 | 0.395 | 0.693 | Not accept |

| H2b | Natural capital → Landscape service cognition | 0.024 | 0.029 | 0.821 | 0.412 | Not accept |

| H2c | Physical capital → Landscape service cognition | 0.084 | 0.041 | 2.044 | * | Accept |

| H2d | Financial capital→ Landscape service cognition | 0.181 | 0.040 | 4.511 | *** | Accept |

| H2e | Social capital → Landscape service cognition | 0.118 | 0.039 | 3.039 | ** | Accept |

| H2f | Cultural capital → Landscape service cognition | 0.208 | 0.047 | 4.435 | *** | Accept |

| H3a | Landscape service cognition → Participation intention | 0.772 | 0.152 | 5.076 | *** | Accept |

| H3b | Landscape service cognition → Conservation intention | 0.401 | 0.077 | 5.182 | *** | Accept |

| H3c | Landscape service cognition → Promotion intention | 0.614 | 0.123 | 4.994 | *** | Accept |

| Hypothesis | Hypothesized Path | Standardized Indirect Effect | Bias-Corrected | Percentile | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Limit | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Lower Limit | ||||

| H4 | Natural capital → Landscape service cognition → Participation intention | 0.026 | 0.088 | −0.020 | 0.083 | −0.038 | Not accept |

| Natural capital → Landscape service cognition → Conservation intention | 0.024 | 0.082 | −0.017 | 0.077 | −0.021 | Not accept | |

| Physical capital → Landscape service cognition → Conservation intention | 0.060 * | 0.129 | 0.011 | 0.123 | 0.007 | Accept | |

| Physical capital → Landscape service cognition → Promotion intention | 0.049 * | 0.108 | 0.010 | 0.103 | 0.006 | Accept | |

| Financial capital → Landscape service cognition → Conservation intention | 0.146 ** | 0.226 | 0.073 | 0.232 | 0.077 | Accept | |

| Financial capital → Landscape service cognition → Promotion intention | 0.119 ** | 0.193 | 0.062 | 0.191 | 0.060 | Accept | |

| Cultural capital → Landscape service cognition → Promotion intention | 0.131 ** | 0.215 | 0.061 | 0.222 | 0.063 | Accept | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Cheng, Y.; Cai, J.; Zhang, X. Influence of Livelihood Capitals on Landscape Service Cognition and Behavioral Intentions in Rural Heritage Sites. Land 2024, 13, 1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13111770

Li S, Cheng Y, Cai J, Zhang X. Influence of Livelihood Capitals on Landscape Service Cognition and Behavioral Intentions in Rural Heritage Sites. Land. 2024; 13(11):1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13111770

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Shiying, Yaqi Cheng, Jiayu Cai, and Xuewei Zhang. 2024. "Influence of Livelihood Capitals on Landscape Service Cognition and Behavioral Intentions in Rural Heritage Sites" Land 13, no. 11: 1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13111770

APA StyleLi, S., Cheng, Y., Cai, J., & Zhang, X. (2024). Influence of Livelihood Capitals on Landscape Service Cognition and Behavioral Intentions in Rural Heritage Sites. Land, 13(11), 1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13111770