Cultural Heritage, Migration, and Land Use Transformation in San José Chiltepec, Oaxaca

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Indigenous Communities, Peasantry, and Territorial Identity

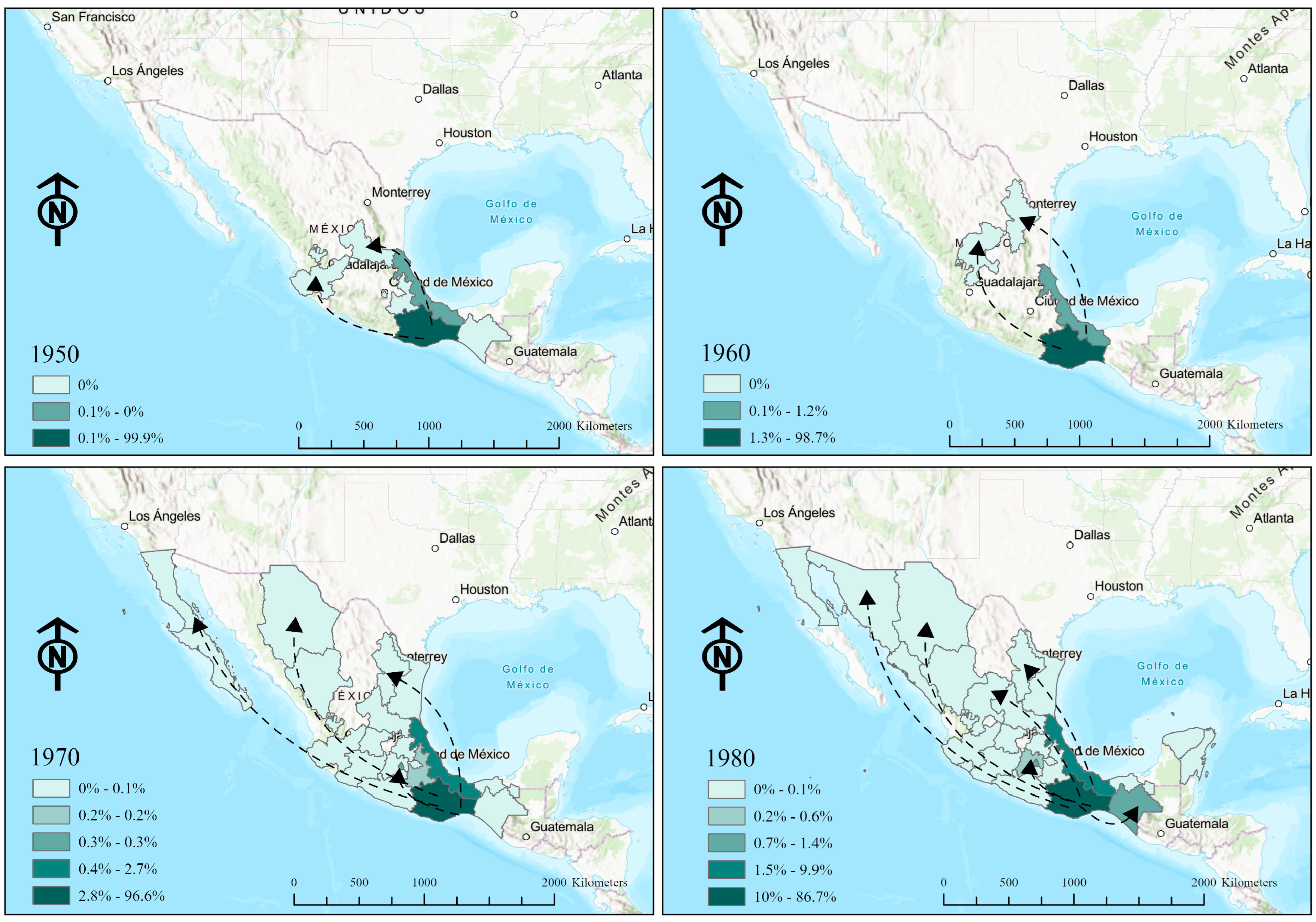

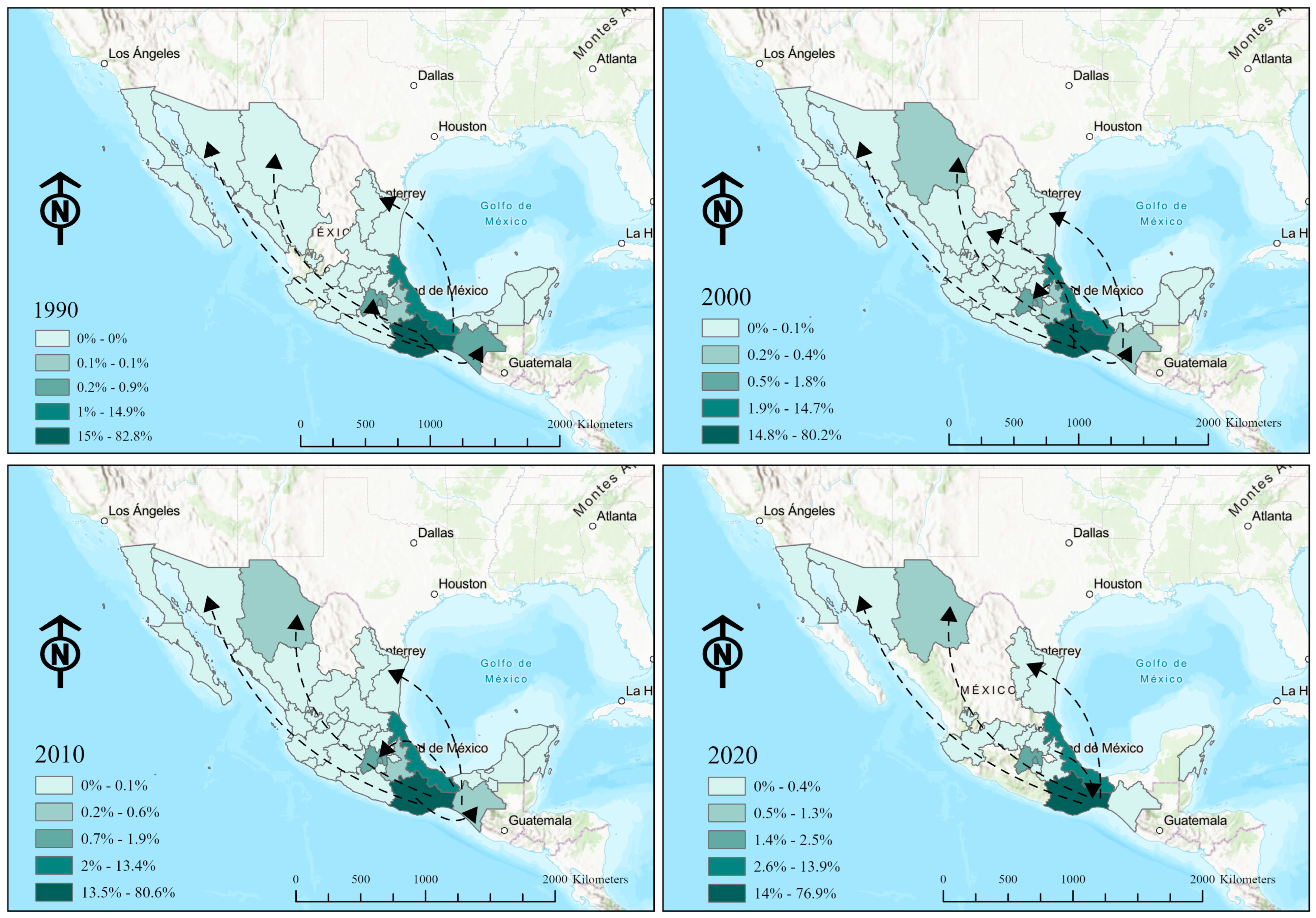

2.2. Migration, Knowledge Loss, and Cultural Heritage

2.3. Sustainable Land Management, Agricultural Techonology, and Indigenous Contexts

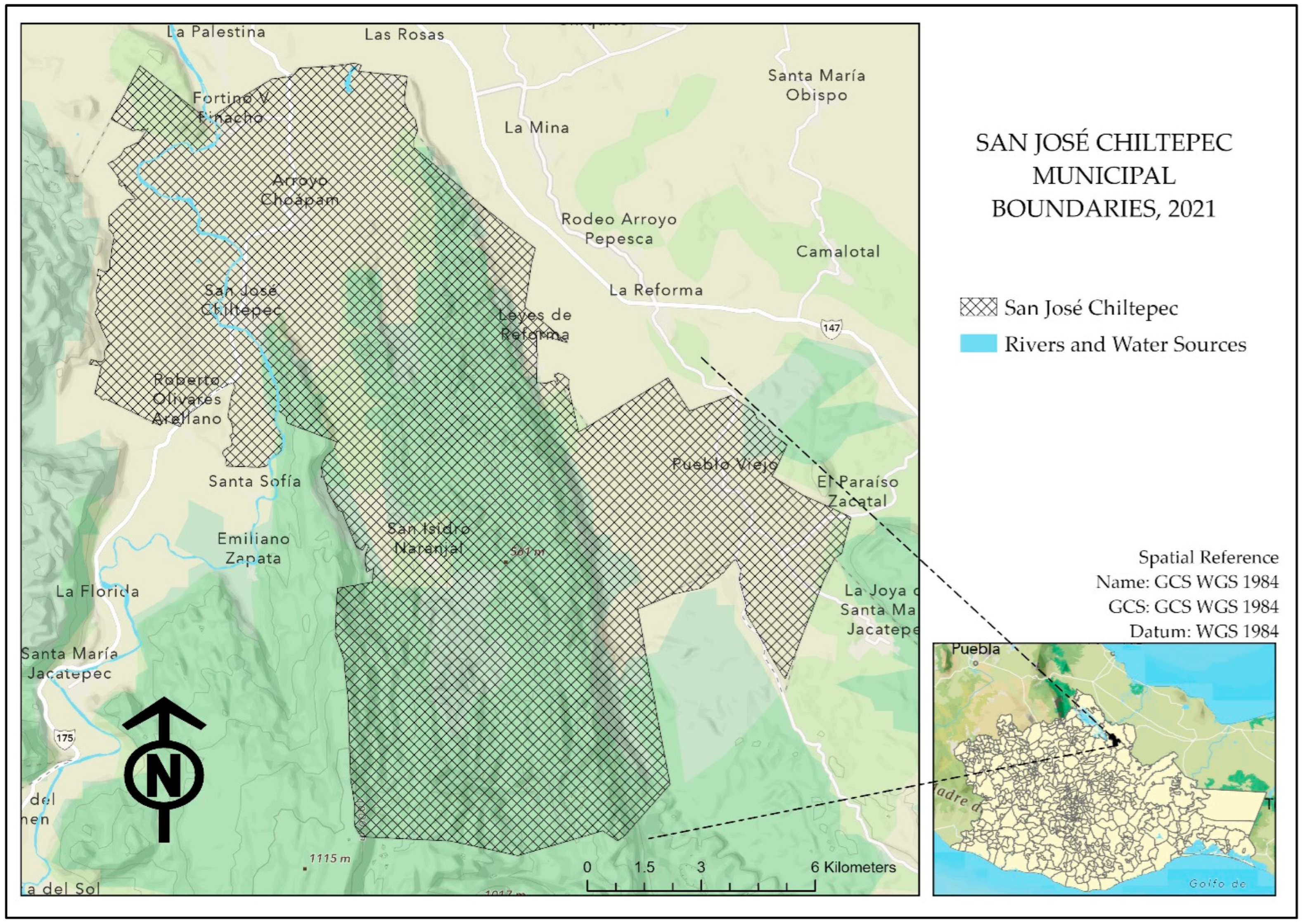

2.4. Study Site Location and Context: Importance of the Region and Research

3. Materials and Methods

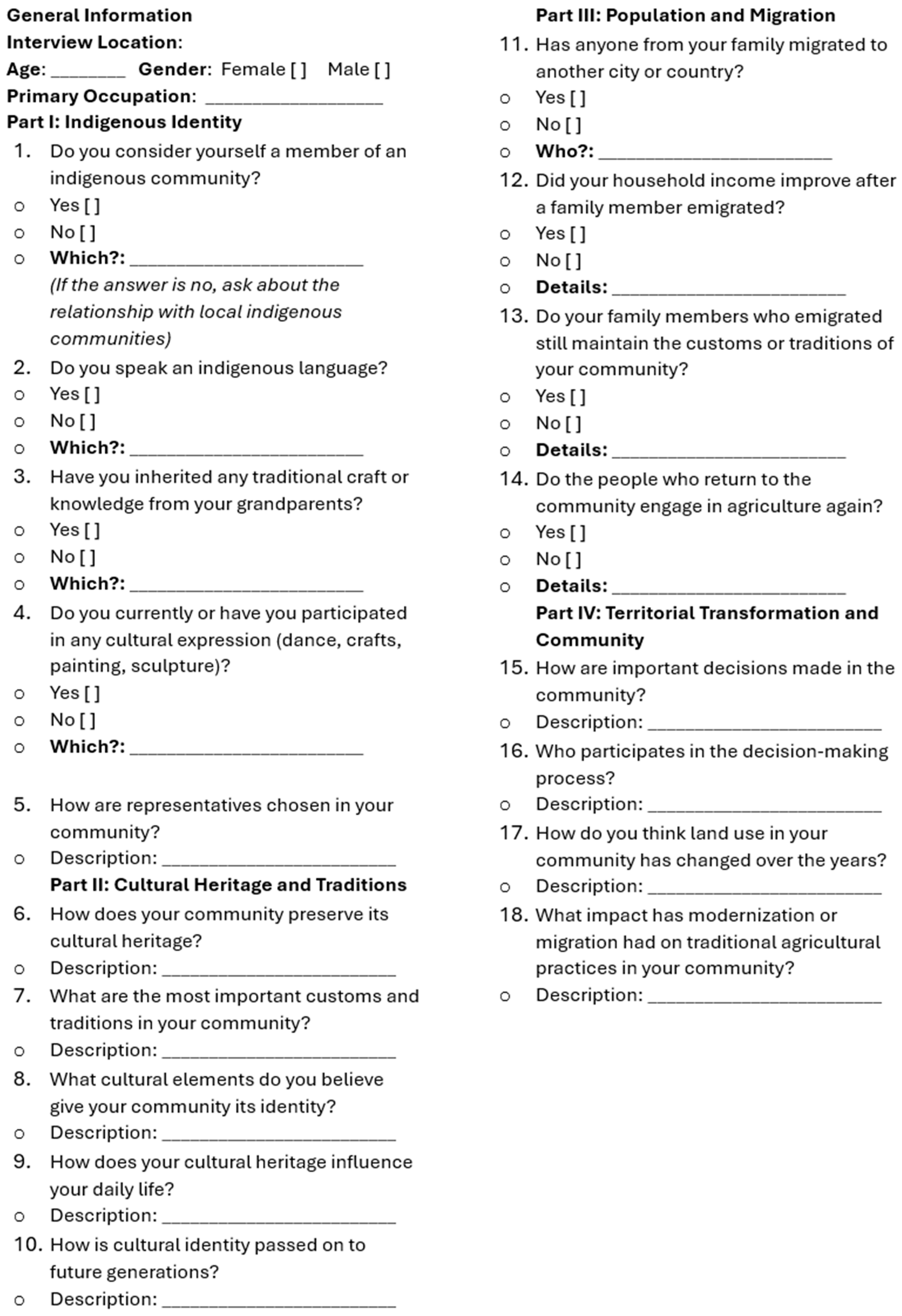

3.1. Data Collection

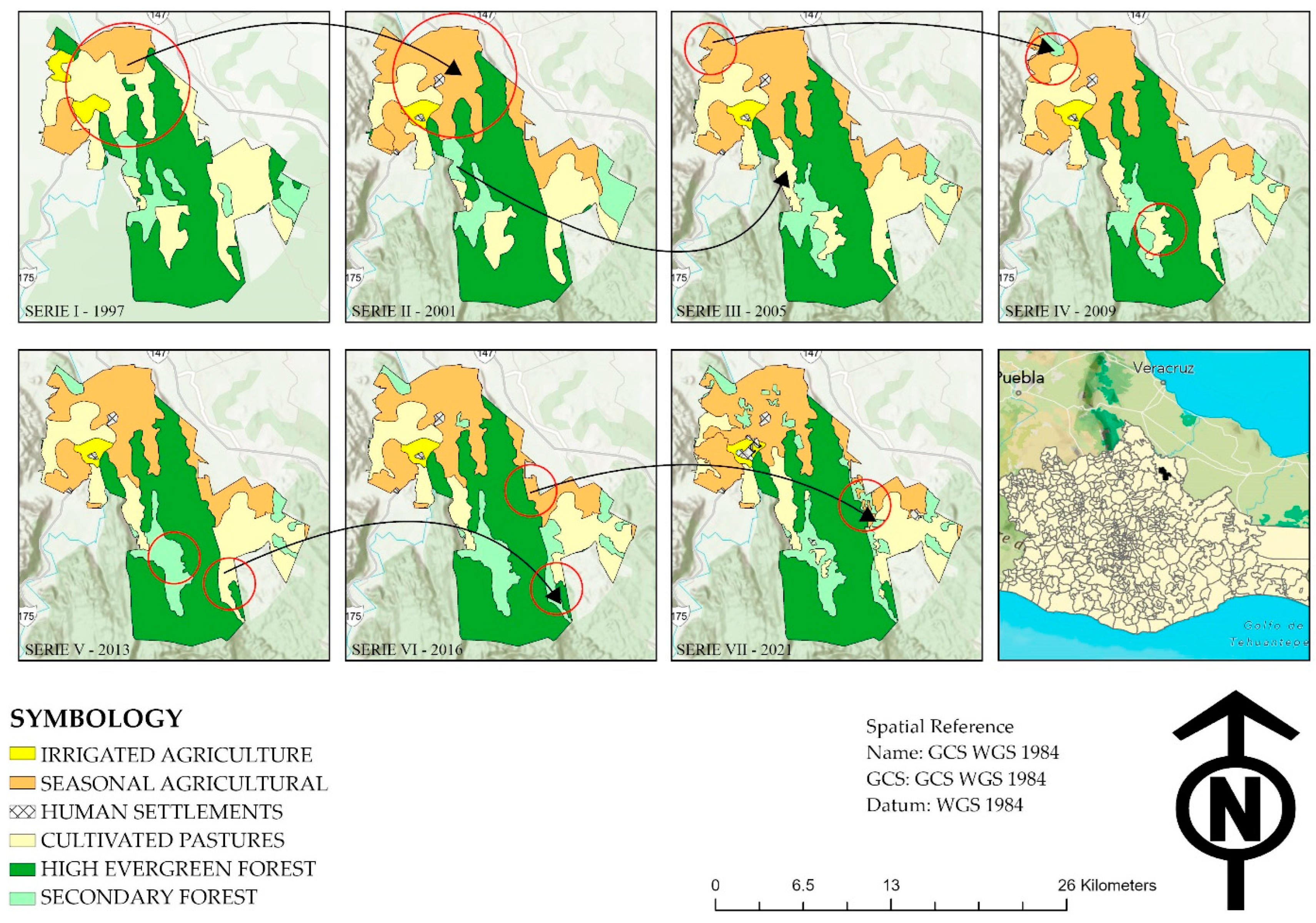

3.2. Geospatial Analysis

3.3. Ethnographic Approach

3.4. Data Validation and Triangulation

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Cultural Heritage, Migration, and Transformation of Land Use

4.2. Agricultural and Vegetation Dynamics: Irrigation, Pastures, and Forests

4.2.1. Shifts in Irrigated Agriculture: Adaptation and Decline

4.2.2. Dynamics of Seasonal Agriculture: Resilience in Traditional Practices

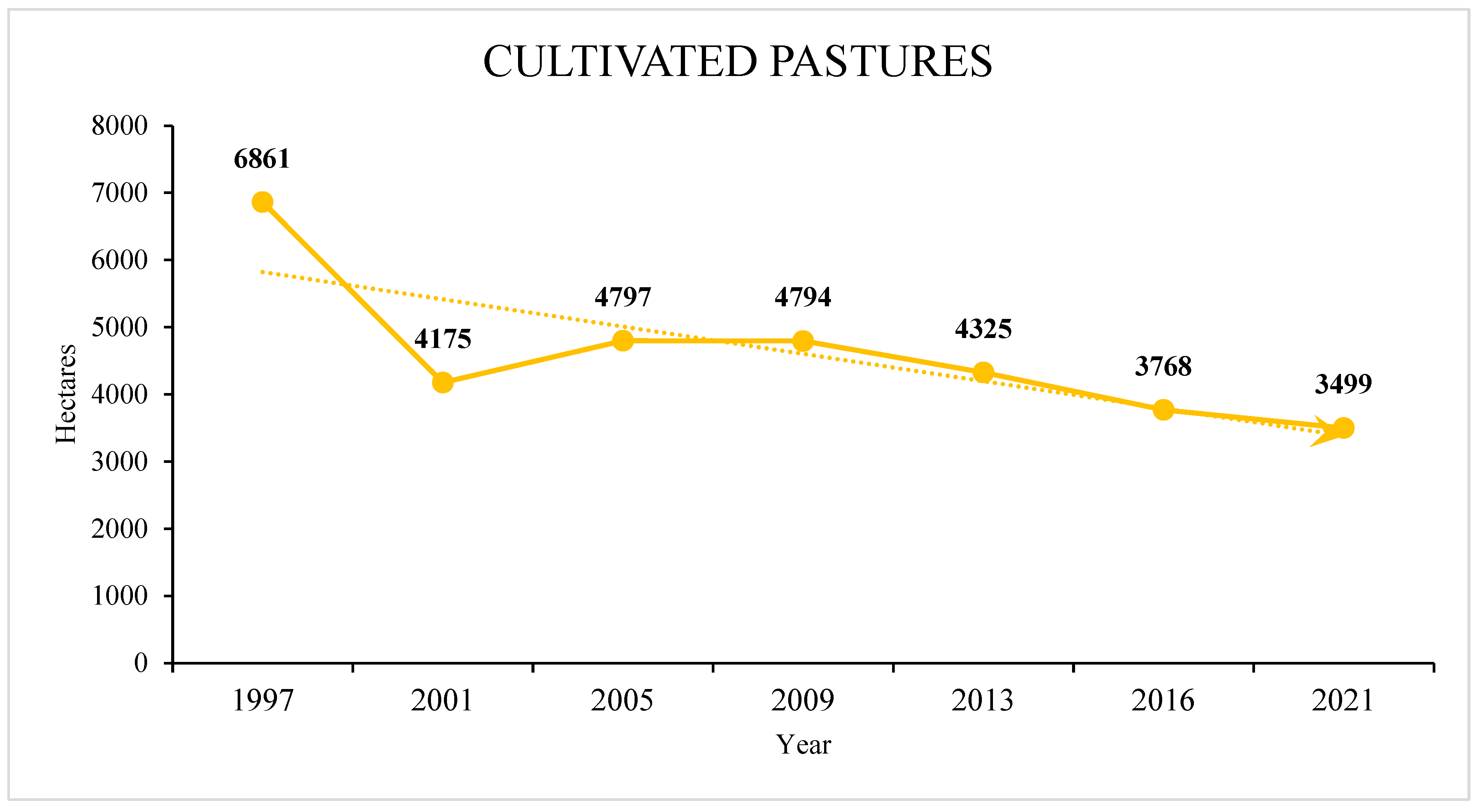

4.2.3. Evolution of Cultivated Pastures and Livestock Management

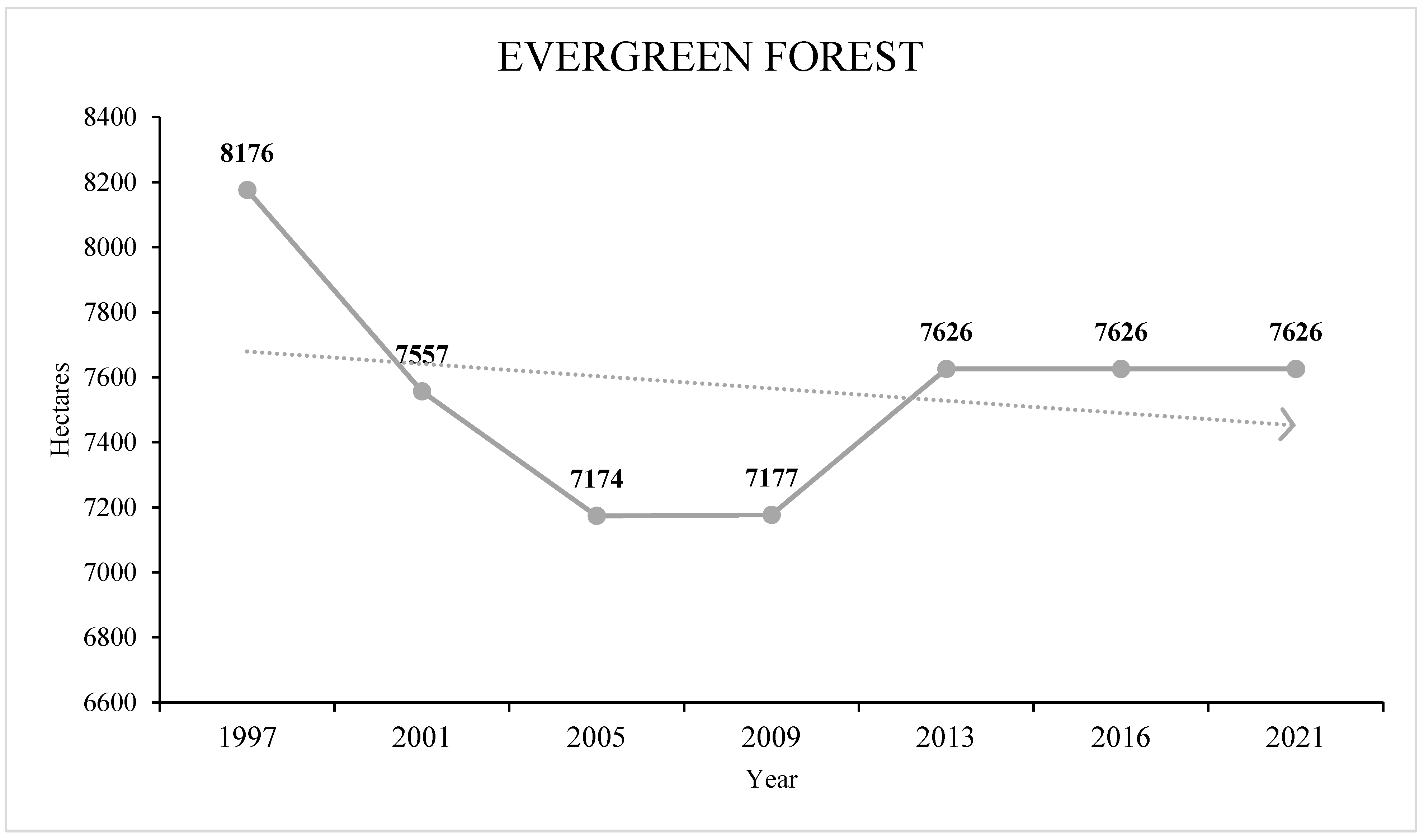

4.2.4. Evergreen Forest: Conservation and Land Use Pressures

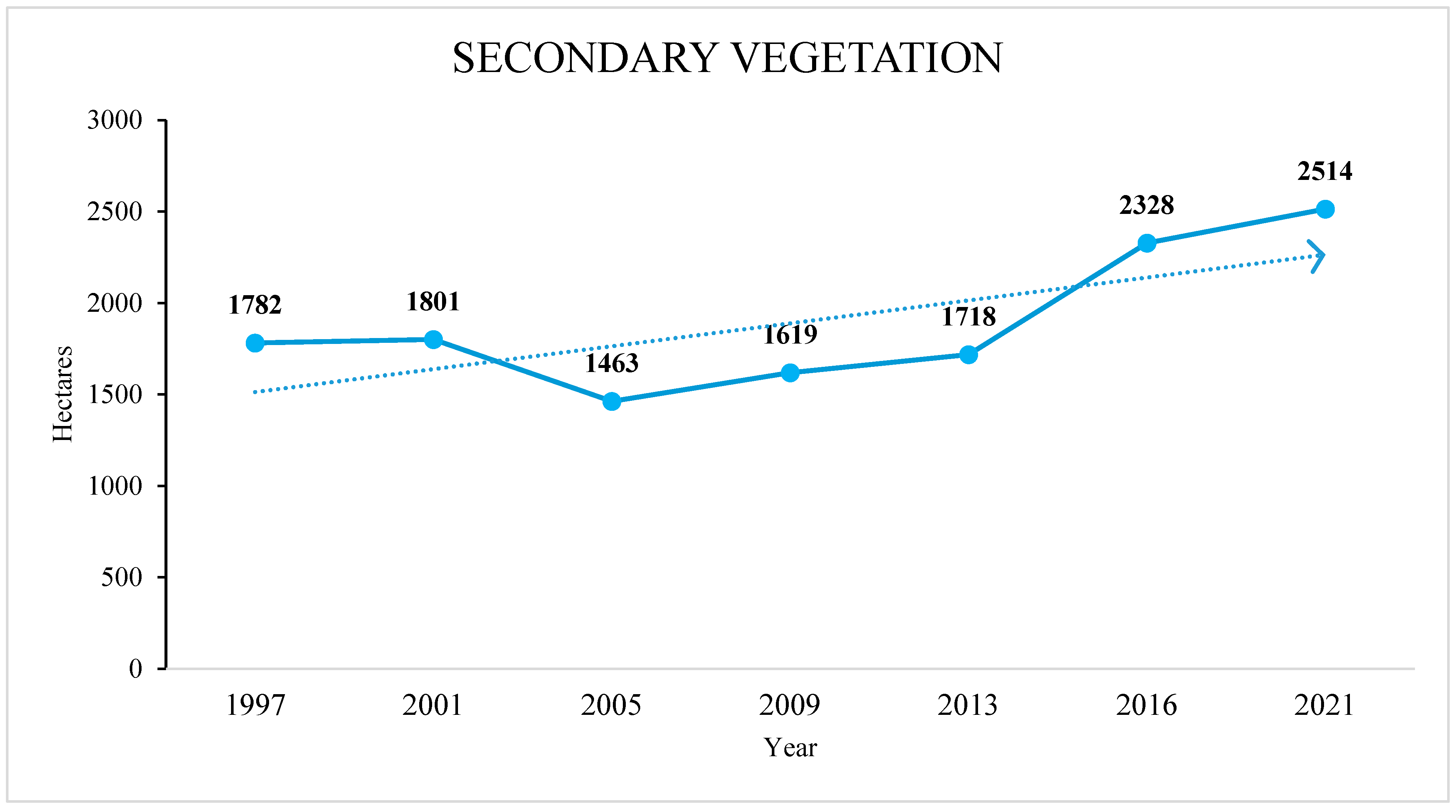

4.2.5. Expansion of Secondary Vegetation: Regrowth and Land Use Recovery

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Lindner, C.; Degbelo, A.; Vassányi, G.; Kundert, K.; Schwering, A. The SmartLandMaps Approach for Participatory Land Rights Mapping. Land 2023, 12, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bada, X.; Fox, J. Persistent Rurality in Mexico and ‘the Right to Stay Home’. J. Peasant Stud. 2022, 49, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Ramírez, G. Migración Internacional y Cambio En Los Poblados de Origen. Rev. Mex. Sociol. 2017, 79, 515–542. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D. Percepciones Comunitarias Sobre Mecanismos de Conservación de Recursos Naturales Bajo Un Enfoque Paisajístico En Tres Ejidos de La Chinantla, Oaxaca. In Aproximaciones teórico-Metodológicas para el Análisis Territorial y el Desarrollo Regional Sostenible; Martínez-Pellegrini, S.E., Sarmiento-Franco, J.F., Valles-Aragón, M.C., Eds.; Recuperación transformadora de los territorios con equidad y sostenibilidad; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas y Asociación Mexicana de Ciencias para el Desarrollo Regional: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-607-30-5332-7. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Liu, J.; Zhang, M. Land Property Rights, Spatial Form, and Land Performance: A Framework of Policy Performance Evaluation on Collective-Owned Construction Land and Evidence from Rural China. Land 2024, 13, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, K.L.; Ramirez, L.F.; Sum, C.; Lopez-Ridaura, S.; Dale, V.H. Enhance Indigenous Agricultural Systems to Reduce Migration. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byamugisha, F.F.K. Experiences and Development Impacts of Securing Land Rights at Scale in Developing Countries: Case Studies of China and Vietnam. Land 2021, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierros-González, I.; Mora-Rivera, J. Drivers of Livelihood Strategies: Evidence from Mexico’s Indigenous Rural Households. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boltvinik, J. Funcionamiento Económico de Los Hogares; Sus Fuentes de Bienestar y Sus Recursos. Estud. Sociológicos 2024, 42, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleitas, K.; Paz, M.; Valverde, S. Aportes de Alexander Chayanov a Los Estudios de La Antropología Económica y Rural. Papeles Trab.-Cent. Estud. Interdiscip. En Etnolingüística Antropol. Socio-Cult. 2020, 40, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.; Nakagawa, Y.; Kobayashi, Y. Conditions under Which Rural-to-Urban Migration Enhances Social and Economic Sustainability of Home Communities: A Case Study in Vietnam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selod, H.; Shilpi, F. Rural-Urban Migration in Developing Countries: Lessons from the Literature. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2021, 91, 103713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragomeli, R.; Annunziata, A.; Punzo, G. Promoting the Transition towards Agriculture 4.0: A Systematic Literature Review on Drivers and Barriers. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemtou, M.; Kakkavou, K.; Anastasiou, E.; Fountas, S.; Pedersen, S.M.; Isakhanyan, G.; Erekalo, K.T.; Pazos-Vidal, S. Farmers’ Transition to Climate-Smart Agriculture: A Systematic Review of the Decision-Making Factors Affecting Adoption. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Carr, D. A Review of Small Farmer Land Use and Deforestation in Tropical Forest Frontiers: Implications for Conservation and Sustainable Livelihoods. Land 2021, 10, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, S.A.; Johnson, L.; Mendoza Chui, K. Indigenous Methodologies in International Research on Indigenous Family and Community Engagement. Rev. Educ. Res. 2024, 0, 00346543241279565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L. Indigenous Intergenerational Resilience and Lifelong Learning: Critical Leverage Points for Deep Sustainability Transformation in Turbulent Times. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojong, N. Indigenous Land Rights: Where Are We Today and Where Should the Research Go in the Future? Settl. Colon. Stud. 2020, 10, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Sarker, T.; Yadav, A.; Garg, I.; Gupta, M.; Sarvaiya, H. Indigenous Communities and Sustainable Development: A Review and Research Agenda. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2024, 43, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon (Iñupiaq), H.S.J.; Ross, J.A.; Bauer-Armstrong, C.; Moreno, M.; Byington (Choctaw), R.; Bowman (Lunaape/Mohican), N. Integrating Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Land into Land Management through Indigenous-Academic Partnerships. Land Use Policy 2023, 125, 106469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.C.; Ban, N.C.; Bhattacharyya, J. A Review of Successes, Challenges, and Lessons from Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 241, 108271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Pérez-Pacheco, R.; Vásquez-Lopez, A.; Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Ortiz-Hernández, F.E. La Inclusión de Comunidades En La Conservación de Áreas Naturales. Caso Parque Nacional Montaña de Celaque, Honduras. Interciencia 2018, 43, 168–174. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Rocha, E.E.; Osorio-García, M.; Nava-Bernal, G.E. Transformación Del Paisaje Rural Desde Los Significados Sociales: Caso Malinalco, Estado de México. Investig. Tur. 2024, 28, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ren, X.; Lu, F. Research Status and Trends of Agrobiodiversity and Traditional Knowledge Based on Bibliometric Analysis (1992-Mid–2022). Diversity 2022, 14, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangha, K.K. Global Importance of Indigenous and Local Communities’ Managed Lands: Building a Case for Stewardship Schemes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, D.B.; Duran, E.; Molina, O. Beyond Harvests in the Commons: Multi-Scale Governance and Turbulence in Indigenous/Community Conserved Areas in Oaxaca, Mexico. Int. J. Commons 2012, 6, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, D.; Stoeckl, N.; Larson, S.; Grainger, D.; Addison, J.; Larson, A. The Learning Generated Through Indigenous Natural Resources Management Programs Increases Quality of Life for Indigenous People—Improving Numerous Contributors to Wellbeing. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 180, 106899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI. Compendio de Información Geográfica Municipal 2010. San José Chiltepec, Oaxaca; Compendio de información geográfica municipal; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2010; p. 9.

- INEGI. Marco Geoestadístico, Diciembre 2023. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=794551067314 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- DATAMEXICO. San José Chiltepec: Economía, Empleo, Equidad, Calidad de Vida, Educación, Salud y Seguridad Pública. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/geo/san-jose-chiltepec (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Auderset, J.; Moser, P. Exploring Agriculture in the Age of Industrial Capitalism: Swiss Farmers and Agronomists in North America and the Transnational Entanglements of Agricultural Knowledge, 1870s to 1950s. Agric. Hist. 2022, 96, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezquerro-Cañete, A. The Agrarian Question of Extractive Capital: Political Economy, Rural Change, and Peasant Struggle in 21st Century Paraguay; Saint Mary’s University: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez, S. Capitalismo Del Conocimiento: ¿méxico En La Integración? Probl. Desarro. 2006, 37, 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezquerro-Cañete, A.; Veltmeyer, H. Extractivismo, Desarrollo Capitalista y La Cuestión Agraria En El Siglo XXI. Rev. Interdiscip. Estud. Agrar. 2022, 57, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado-López, E.; Torres Tranco, J.L.; Scherer Ibarra, G. La lucha por la tierra en México (1976-1982). Rev. Mex. Cienc. Políticas Soc. 2019, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saumade, F. Carnaval y emigración temporal en México. La cosmología otomí regenerada por la aculturación. Dimens. Antropológica 2012, 56, 99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta-Calderón, J.A. La Cuestión Indígena En México y América Latina. Textual Análisis Medio Rural Latinoam. 2018, 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Olazabal-Arrabal, M.A.; Rodríguez-Méndez, V.; González-Fontes, R. La Identidad Cultural Como Recurso Local y Su Integración a La Gestión Del Desarrollo Territorial. Retos Dir. 2021, 15, 27–60. [Google Scholar]

- Teresa, A.P. de Población y Recursos En La Región Chinanteca de Oaxaca. Desacatos Rev. Cienc. Soc. 1999, 1, 125–151. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Pérez-Pacheco, R.; Ortiz-Hernández, F.E.; Martínez-Tomás, S.H.; Tavera-Cortés, M.E. Nature-Based Solutions for Conservation and Food Sovereignty in Indigenous Communities of Oaxaca. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Ortiz-Hernández, F.E. Herramientas Metodológicas En Procesos Participativos En Comunidades Rurales Para La Conservación de Recursos Naturales. In Estrategias para el Desarrollo Sostenibles de México, Tavera-Cortés, M.E., Ed.; ASMIIA: Texcoco, Edo. de México. Mexico, 2022; pp. 93–106. ISBN 978-607-99921-0-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Aquino-Bolaños, T. Huertos Familiares y Participación Comunitaria Para La Generación de Medios de Vida Sostenibles. In Los objetivos del Desarrollo Sostenible versus la Pandemia de la COVID-19; Tavera-Cortés, M.E., Ed.; ASMIIA: Texcoco, Edo. de México. Mexico, 2023; pp. 125–138. ISBN 978-607-596-753-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas-Tabares, F. Proyectos Turísticos. Localización e Inversión, Turismo, 2nd ed.; Trillas: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2006; ISBN 968-24-7581-3. [Google Scholar]

- Huizar-Sánchez, M.d.l.A.; Villanueva-Sánchez, R. El Inventario de Recursos Turísticos. Formulación y Evaluación, 1st ed.; Universidad de Guadalajara: Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, 2021; ISBN 978-607-571-231-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Alberti-Manzanares, M.D.P.; Figueroa-Rodríguez, O.L.; Talavera-Magaña, D.; Cordero, J.C.M. Patrimonio Cultural y Género Como Estrategia de Desarrollo En Tepetlaoxtoc, Estado de México. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2011, 9, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casa del Pueblo, Pueblo Viejo, Chiltepec, Oax. Proyecto Huipiles—Preparación de Materiales y Equipo. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=egNlT5-jArk (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Ortiz-Hernández, F.E. Personal Communication Semi-structured interview for stakeholders. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mundaca, A. Chiltepec, Pueblo Chinanteco de Oaxaca con Altares de Yuca, Iguana y Pejelagarto. Available online: https://oaxaca.eluniversal.com.mx/mas-de-oaxaca/chiltepec-pueblo-chinanteco-de-oaxaca-con-altares-de-yuca-iguana-y-pegelagarto (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Mundaca, A. Cochinita a la Cubana, Legado de Migración y Mestizaje que Arraigó en la Cuenca de Oaxaca. Available online: https://oaxaca.eluniversal.com.mx/mas-de-oaxaca/cochinita-la-cubana-legado-de-migracion-y-mestizaje-que-arraigo-en-la-cuenca-de-oaxaca (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Vivar, J.L. Día de Muertos en Chiltepec, Oaxaca. Available online: https://www.milenio.com/opinion/jose-luis-vivar/columna-jose-luis-vivar/dia-de-muertos-en-chiltepec-oaxaca (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- INEGI. VII Censo General de Población 1950. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/1950/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- INEGI. X Censo General de Población y Vivienda 1980. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/1980/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- INEGI. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie I. Continuo Nacional. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825007020 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- SISPLADE. Plan Municipal de Desarrollo 2008–2010. San José Chiltepec; Planes municipales de desarrollo; Gobierno del estado de Oaxaca: Oaxaca, Mexico, 2008; p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie II. Continuo Nacional. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825007021 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- INEGI. IX Censo General de Población 1970. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/1970/#tabulados (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- INEGI. XI Censo General de Población y Vivienda 1990. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/1990/ (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- INEGI. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Castañeda-Navarrete, J. Rural Urbanisation and Home Gardening in Southern Mexico: Agrobiodiversity Loss and Alternative Pathways. J. Peasant Stud. 2023, 50, 1227–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarrubias-Villa, F.; González-Vera, C.; Covarrubias-Machuca, F.S. El Campesinado En La Teorización Marxista de Los Modos de Producción. Hybris Rev. Filos. 2022, 13, 41–68. [Google Scholar]

- Paré, L. El Proletariado Agrícola En México: ¿campesinos Sin Tierra o Proletarios Agrícolas? 8th ed.; Siglo XXI: Distrito Federal, Mexico, 1988; ISBN 978-968-23-1473-5. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ramírez, F. Experiencias Sobre Choques Culturales En La Educación Básica En Una Localidad Chinanteca, Mamoo: San Miguel Maninaltepec, Oaxaca, En La Década de Los 80´s. Bachelor’s Thesis, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Puebla, Mexico, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, C.; de Cea, M.; Fuentes, C. Reconocimiento Débil: Derechos de Pueblos Indígenas En Chile. Perfiles Latinoam. 2017, 25, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Silva, J.M.; Romero-Borré, J.; Arias-Montero, S.R.; Briones-Mendoza, X.F. Migración: Contexto, Impacto y Desafío. Una Reflexión Teórica. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2020, XXVI, 299–313. [Google Scholar]

- SISPLADE. Plan Municipal de Desarrollo 2014–2016. San José Chiltepec; Planes municipales de desarrollo; Gobierno del estado de Oaxaca: Oaxaca, Mexico, 2014; p. 138. [Google Scholar]

- SISPLADE. Plan Municipal de Desarrollo 2022–2024. San José Chiltepec; Planes municipales de desarrollo; Gobierno del estado de Oaxaca: Oaxaca, Mexico, 2022; p. 294. [Google Scholar]

- Devine, J.A.; Ojeda, D.; Yie-Garzón, S.M. Formaciones Actuales de Lo Campesino En América Latina: Conceptualizaciones, Sujetos/as Políticos/as y Territorios En Disputa. Antipoda Rev. Antropol. Arqueol. 2020, 1, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concheiro-San Vicente, L. Descampesinistas Contra Campesinistas: Una Polémica Marxista En Torno al Campesinado Mexicano. Inflexiones Rev. Cienc. Soc. Humanidades 2022, 10, 36–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.; Jackson, G.; McNamara, K.E. Climate-Driven Losses to Knowledge Systems and Cultural Heritage: A Literature Review Exploring the Impacts on Indigenous and Local Cultures. Anthr. Rev. 2023, 10, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Carrera, V. La Segunda Revalorización Del Campesinado En México: De “Pobres” y “Población Redundante” a Sujetos Productivos y de Derechos. EntreDiversidades Rev. Cienc. Soc. Humanidades 2016, 7, 14–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svampa, M. Desde Abajo… La Transformación de Las Identidades Sociales, Sociedad, 3rd ed.; Biblos: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2009; ISBN 978-950-786-267-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rojo-Horta, J. Chinantecos Desplazados Por La Presa Cerro de Oro, En Oaxaca. El Cotid. 2014, 183, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI. INEGI. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie III. Continuo Nacional. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825007022 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- INEGI. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie IV. Conjunto Nacional. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825007023 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- INEGI. Conjunto de datos vectoriales de la carta de Uso del suelo y vegetación. In Escala 1:250 000. Serie V. Conjunto Nacional. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825007024 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- INEGI. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie VI. Conjunto Nacional. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=889463598459 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Molinari, M.S.; Aguilar-Medina, J.Í. Cosmovisión de La Vida Cotidiana En Chiltepec, Oaxaca. Diario De Campo 2013, 12, 19–56. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Pérez-Pacheco, R. Construyendo Capacidades Locales Para Obtener Financiamiento Colectivo e Implementar Huertos Familiares En La Chinantla, Oaxaca. In Los objetivos del Desarrollo Sostenible versus la Pandemia de la COVID-19; Tavera-Cortés, M.E., Ed.; ASMIIA: Texcoco, Edo. de México. Mexico, 2023; pp. 112–124. ISBN 978-607-596-753-0. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, N.A.A.; Ariffin, N.F.M.; Ismail, N.A.; Ismail, S.; Alias, A.; Utaberta, N. The Comparison of the Best Practices of the Community-Based Education for Living Heritage Site Conservation. Lect. Notes Civ. Eng. 2022, 161, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Al Mamun, A.; Naznen, F.; Masud, M.M. Adoption of Conservative Agricultural Practices among Rural Chinese Farmers. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeweld, W.; Van Huylenbroeck, G.; Tesfay, G.; Speelman, S. Smallholder Farmers’ Behavioural Intentions towards Sustainable Agricultural Practices. J. Environ. Manage. 2017, 187, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SISPLADE. Atlas de Riesgos de San José Chiltepec; Atlas de riesgos; Gobierno del estado de Oaxaca: Oaxaca, Mexico, 2011; p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Gracia, P.; Gómez-Díaz, J.D.; Monterroso-Rivas, A.I.; Uribe-Gómez, M. Tecnologías Agroforestales Para Una Selva Baja Caducifolia: Propuesta Metodológica. Rev. Mex. Cienc. For. 2020, 10, 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Vega, J. Cubiertas Vegetales y Barreras Vivas: Tecnologías Con Potencial Para Reducir La Erosión En Oaxaca, México. Terra Latinoam. 2001, 19, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Burgos-Herrera, B.; Cruz-León, A.; Uribe-Gómez, M.; Lara-Bueno, A.; Maldonado-Torres, R. Valor Cultural de Especies Arbóreas En Sistemas Agroforestales de La Sierra de Huautla, Morelos. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2016, 7, 3277–3286. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda-López, R.; Febvre, N.; Martínez, M. Importancia de Proteger Pequeñas Áreas Periurbanas Por Su Riqueza Avifaunística: El Caso de Mompaní, Querétaro, México. Huitzil 2010, 11, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Natural Elements | Description |

|---|---|

| San Isidro Naranjal Waterfalls | This continuous-flow mountain waterfall features turquoise-toned water and stunning natural landscapes. It is in good conservation status, free of debris. Visitors can engage in ecotourism, landscape observation, and hiking activities. Category: waterfalls; type: continuous flow waterfall; subtype: mountain waterfall. |

| Papaloapan River | A seasonal river with scenic landscapes, its flow varies according to the time of year. The river’s flow is sustained by rainfall in the Papaloapan Basin. Activities include birdwatching and capturing photographs of the scenic river environment. Category: rivers; type: seasonal river; subtype: scenic river. |

| Conservation Area | A protected area where endemic fauna, including birds and mammals, can be observed. Due to the conservation status of the natural reserves, deeper access to the lowland forest is restricted because of the danger posed by species like snakes and tarantulas. Local guides lead hiking tours in designated areas for short stays and exploration. Category: flora and fauna observation sites; type: endemic fauna; subtype: birds and mammals. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Aquino-Bolaños, T.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Ortiz-Hernández, F.E.; Pérez-Pacheco, R.; López-Cruz, J.Y. Cultural Heritage, Migration, and Land Use Transformation in San José Chiltepec, Oaxaca. Land 2024, 13, 1658. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13101658

Lugo-Espinosa G, Acevedo-Ortiz MA, Aquino-Bolaños T, Ortiz-Hernández YD, Ortiz-Hernández FE, Pérez-Pacheco R, López-Cruz JY. Cultural Heritage, Migration, and Land Use Transformation in San José Chiltepec, Oaxaca. Land. 2024; 13(10):1658. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13101658

Chicago/Turabian StyleLugo-Espinosa, Gema, Marco Aurelio Acevedo-Ortiz, Teodulfo Aquino-Bolaños, Yolanda Donají Ortiz-Hernández, Fernando Elí Ortiz-Hernández, Rafael Pérez-Pacheco, and Juana Yolanda López-Cruz. 2024. "Cultural Heritage, Migration, and Land Use Transformation in San José Chiltepec, Oaxaca" Land 13, no. 10: 1658. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13101658

APA StyleLugo-Espinosa, G., Acevedo-Ortiz, M. A., Aquino-Bolaños, T., Ortiz-Hernández, Y. D., Ortiz-Hernández, F. E., Pérez-Pacheco, R., & López-Cruz, J. Y. (2024). Cultural Heritage, Migration, and Land Use Transformation in San José Chiltepec, Oaxaca. Land, 13(10), 1658. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13101658