Abstract

Tourism boosts the regional economy and encompasses various sectors that determine its potential, promoting economic, environmental and social development by generating the creation of small and medium-sized enterprises and employment, thus improving people’s quality of life. In this context, an analysis of the structural changes in the number of visitors to the Kuélap archaeological site in the region of Amazonas, Peru was conducted. The closure of the Kuélap Monumental Archaeological Zone was selected as the object of analysis since the Kuélap archaeological site constitutes the most prominent tourist resource in the department of Amazonas and is the main attraction for tourists to visit. This study was carried out by using an analytical and descriptive approach, with a non-experimental longitudinal and cross-sectional design. Data from the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Tourism (MINCETUR) were used, and the perspective of tourism providers by means of a survey applied to a sample of 83 entrepreneurs in Chachapoyas, Tingo and La Malca was analysed. The results show that the implementation of cable cars in Kuélap has had a positive impact of 54% on sales and employment, while the COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact of 81%. On the other hand, the closure of the archaeological site has had a negative impact of 52%. Any negative impact on the Kuélap archaeological site resulted in a slowdown in the regional economy. In conclusion, from the point of view of visitor records and the perspective of tourism providers regarding structural changes, social impact is reflected in different economic sectors and, therefore, in the development of the local and regional economy. It is essential to consider these aspects when making decisions and developing strategies to promote tourism in the region in order to improve the quality of life of its residents (social, economic and cultural well-being).

1. Introduction

Tourism is an important sector that generates jobs and income and contributes to the gross domestic product (GDP), contributing to the economic development of a tourist destination [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Visits to tourism resources used to be less common in the past; however, the onset of globalization with changes in means of transport, population growth, technological revolution, emergence of social networks, as well as the increase in communication media generated accelerated growth in visits to tourism resources [7,8,9], having a dynamic and positive effect on the economy, thereby creating employment and income for the host country [10]. Therefore, the tourism sector has contributed significantly to socioeconomic development in several regions of the world [11,12], making the sustainable management of tourist destinations essential [13,14,15,16].

In recent years, tourism has been considered an alternative way to attract economic resources in poorer regions and has led to economic development [17,18,19]. Furthermore, it has become one of the most dynamic forms of business worldwide [20]. This trend has given rise to the globalization of tourism, offering quality services in different social strata, and has promoted an internalization of the activity, which has gained strength in the business field [21]. Tourism has become a positive tool for local and regional development, allowing for economic, social and cultural benefits in the community, which improves the quality of life of the people who dedicate themselves to this activity [22]; however, there is some social concern in relation to the saturation of visitors, especially in traditional tourist destinations, and the management, planning and measurement of its impact are crucial points for tourism development [23], being the key actor who should be concerned with mitigating negative impacts.

It should also be taken into account that tourism in recent decades has had negative impacts that undermine spaces for coexistence and sociability, due to the excessive increase in tourist flows [24,25,26]. In the past, tourism was strongly accelerated by the arrival of trains and planes [27]. Currently, climate change is generating serious consequences in archaeological areas, representing a direct or indirect threat that could endanger the survival of tourism activity [28,29]. This involves risks that could trigger a crisis in the tourism industry. These could be due to viruses, natural threats, sabotage of critical infrastructure, etc. [30], as well as other factors that could give rise to negative attitudes, beliefs, expectations or behaviours that harm the experience of tourists [31].

Although it is recognized that tourism is essential to boost the economy, it must also be taken into account that it can contribute to environmental problems, particularly in highly visited areas [32,33]. The tourist load implies that tourism spaces deteriorate and lose their attractiveness, which negatively impacts the preservation of cultural identity [34]. Despite the importance of the studies carried out by researchers on sustainable tourism, it has still not been possible to stop environmental degradation or resolve social discrepancies [35].

Tourism is an important income-generating activity for many regions and countries. However, the closure of tourism resources due to the COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on travelling, leading to increased unemployment and reduced business income for families and companies that depend on tourism activity [36]. Many tourism resources have had to close or have experienced a significant decrease in their flow of visitors, which has generated uncertainty and a decrease in their economic income [37]. Furthermore, the technological measures implemented to prevent the spread of the coronavirus have affected workers in the tourism sector, due to the various reactions of tourists to the possibility of being in contact with potentially infected people, generating discrimination and racism, which has had negative consequences on people’s mental health [38]. This has caused a considerable impact on the viability of several tourism companies around the world, generating pessimism in the industry and an identification of the urgent need to adapt to the social context [39]. As a result, there has been a significant reduction in income and employment, affecting economic and social development [40,41,42].

Globally, the pandemic has had a devastating impact on the tourism sector, with a 72% drop in international tourist arrivals in 2020, most severely affecting developing countries and tourist destinations that depend on international tourism. In Peru, COVID-19 has had a significant impact on the demand for international tourism, with a 76.8% drop in international tourist arrivals between January and October 2020 [41].

The Kuélap archaeological site, located in the northeast of Peru, Kuélapis the main tourism resource of the Amazon region. In Amazonas, the tourism sector has undergone significant structural changes, from the implementation of cable cars to the closure of the Kuélap Monumental Archaeological Zone, which is one of the main tourism resources of the region. In 2022, only 40,000 tourists visited the Kuélap Monumental Archaeological Zone. This is a decrease of 33% compared to 2021 and 61.6% compared to pre-pandemic levels [43]. These abrupt changes have affected many tourists and have had a significant impact on the providers of tourism services located in the area.

Regarding the economic development of the tourism sector in the Kuélap destination in Amazonas, it is possible to observe structural and scale effects that have had both positive and negative implications [44]. A positive effect is the implementation of cable cars as a means of transport to attract tourists, which highlights the tourism sector as a highly attractive place that offers the opportunity to connect with nature and becomes a key factor in the tourism offer of the region [45], generating a positive impact on tourist attraction and the intention to visit and continue visiting the place [46]. This implementation also has an economic value, both direct and indirect in the region. In a direct way, it led to an increase in tourists, both domestic and foreign, while indirectly, it facilitated the arrival of tourists who decided to settle permanently in the region [47]. The increase in tourists in the site resulted in a direct increase in jobs and income, which in turn contributed to the revitalization of a sustainable economy [48].

This study is distinguished from other studies by its comprehensive approach, considering the intersection of factors such as cable cars, the pandemic and the closure of Kuélap, thus providing a holistic view of the challenges faced by the tourism sector in the region. The uniqueness of this study lies in its dual approach, addressing both supply and demand.

The contribution of this research revolves around the factors that determine tourist visits to the Kuélap archaeological site. This involves the events that can affect the supply and demand of tourist services generated around this heritage. Furthermore, the application of quantitative methods for detecting structural breakage in the series of visits to this archaeological site has no known precedent in academia.

The theoretical contributions of this study are oriented towards the significance that various factors can have on archaeological sites. In this research, it was verified that not all of the hypothesized factors were significant in the demand for the tourist resource in question.

Future limitations should be able to collect a greater number of observations in the series so that more reliable estimators can be obtained, in light of verifying the findings found here.

This document is structured as follows: after the introduction in which the topic under study is presented and the objective is stated, the variables under study are presented in the second section, and then the materials and methods are discussed. Section four shows the results of the research that allow for discussion in the following sections along with the conclusions derived from it.

This research focuses on the structural changes in tourist behaviour from 2013 to 2022 and how the situation of tourism in the area was addressed. The objectives of this research are as follows:

RQ1: To analyse the perspective of providers in relation to the economic impact generated by the implementation of cable cars, the COVID-19 pandemic and the closure of Kuélap in the tourism sector in 2023;

RQ2: To determine the presence of structural breaks in the demand for the Kuélap Monumental Archaeological Zone in the period of 2013–2023;

RQ3: To estimate the effects of the implementation of cable cars, the COVID-19 pandemic and the closure of Kuélap in the tourism sector in 2023.

2. Variables under Study

2.1. The Structural Economic Impact of Visits

Tourism is one of the most significant sectors for many countries and is also one of the most sensitive to structural changes in society and climate change. Economic impact occurs as a result of the contribution generated by an economic activity, producing both positive and negative effects due to people’s actions and natural factors [49]. The economic impact of tourism has a structural nature and becomes evident over time, either directly, indirectly or induced, affecting several economic aspects such as production, the environment, family income and employment [50,51].

The 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant economic impact on all economic sectors worldwide [43]. The tourism sector experienced a sharp fall in the number of travellers, which led to a collapse in tourism businesses, causing many families to switch from the tourism sector to the agricultural sector [24]. In addition, the hotel sector and other actors in tourist centres were forced to reduce their number of employees [52]. Likewise, the seasonality and periodicity of visits to tourist sites had an impact on income and employment generation [53].

In coastal areas, climate change, including the increase in marine storm and rough water events, had significant impacts on tourist areas [54]. In the jungle, the El Niño phenomenon also posed a threat to the tourism sector [55]. At the same time, the tourism sector was affected by the irresponsibility of tourists in terms of bad social practices [56], which often had negative effects on the sector’s employees. On the other hand, job insecurity and the economic pressure faced by families also had an impact on workers’ mental health [57]. Tourism proves to be a scenario that allows for regional integration, as it favours the generation of employment and economic income for host populations [58].

2.2. Perception of Providers among Kuélap Tourists

Tourists’ perception of providers refers to the way in which tourist service providers, such as lodgings, restaurants, travel agencies and artisans, among others, are perceived by tourists [59]. This perception can be influenced by various factors, such as the quality of the services offered, customer service, infrastructure, security, cultural authenticity and other elements that influence the tourist’s experience [60].

Tourists’ perception of providers is crucial for the success and competitiveness of tourist destinations and tourism-related companies. If tourists have a good perception of providers, they are more likely to revisit the destination, recommend the place to other travellers and generate a positive economic impact. To understand tourists’ perception of providers, market research, surveys and analysis of tourist comments and reviews can be conducted [61]. These tools make it possible to collect information on tourists’ satisfaction with the services received, identify providers’ strengths and weaknesses and obtain ideas to improve the tourist experience [62].

Furthermore, this perception may be influenced by marketing strategies, effective communication, the promotion of cultural authenticity and local heritage, as well as by quality management and staff training in the tourism industry [63]. It is important to highlight that tourists’ perception of providers may vary from one tourist to another, since each person has different expectations and preferences. Tourism providers are the ones who offer services to the needs of tourists and strive to provide comfortable experiences.

3. Materials and Methods

This paper utilises quantitative research of different levels. The economic impact of the implementation of cable cars [ITK], the COVID-19 pandemic [PC19] and the closure of Kuélap [CK] in the tourism sector associated with Kuélap was studied from a double perspective: supply and demand.

The survey utilised was designed by the researchers; it was structured taking into consideration the fundamental variables of this study. It comprised a total of twenty-three (23) questions, covering both closed and open options. These questions were designed to address various aspects, such as the general data of the company, its current situation and perceived impacts, as well as the expectations and recommendations of the respondents to reactivate tourism in the department of Amazonas; this instrument was validated by expert judgment.

For this purpose, a search for primary information was carried out in the studies of the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Tourism (MINCETUR), and a questionnaire was developed to contrast the changes in tourism providers. The methodology was a quantitative analysis of a longitudinal, non-experimental design. The number of respondents collected was 83 providers, of which the main findings and conclusions are presented in this study.

Data collection was carried out between the months of January and July 2023. MS Excel was used to process the surveys, while R statistical software (R version: 4.2.3) was used to quantitatively estimate the structural break. The F-test-based structural change test is a statistical tool used to detect whether there are significant differences in the parameters of a regression model in different data segments. In other words, it is used to identify points at which there is a structural change or a break in the behaviour of a time series or data set.

3.1. Kuélap Monumental Archaeological Zone

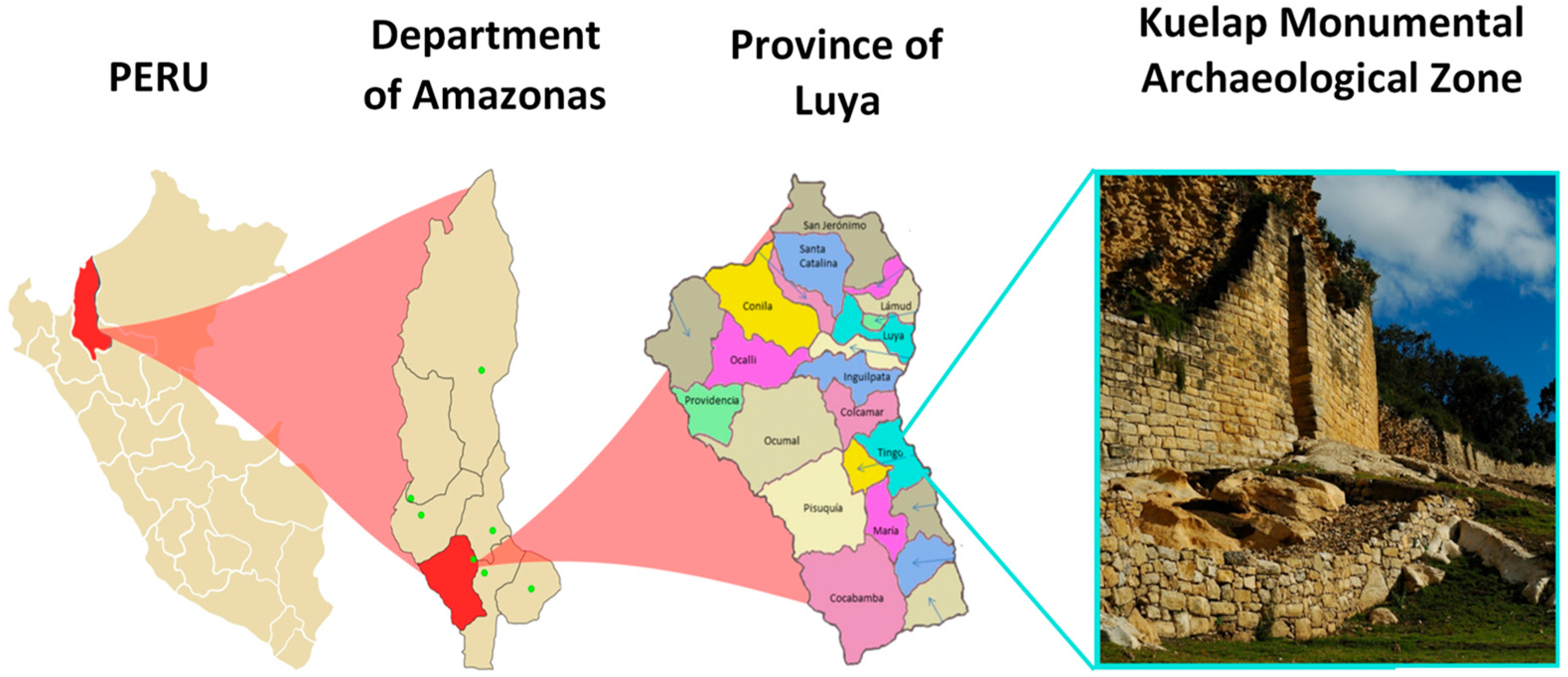

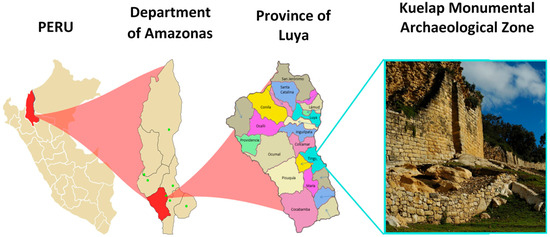

The Kuélap Monumental Archaeological Zone is located in the district of Tingo, province of Luya, department of Amazonas, Peru. It stands majestically on a natural promontory of limestone rock at an altitude of 3000 m above sea level, on the left bank of the Utcubamba River. This fortified citadel, oriented from north to south, represents one of the most outstanding architectural vestiges of the Chachapoya culture, whose occupation spans from the 5th century AD until the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century. Nestled in a humid montane forest ecosystem, with leafy trees populated with bromeliads, orchids, moss and lichens, the citadel extends 584 m and occupies around 6 hectares. Surrounded by a perimeter wall 10 to 20 m high, built entirely of finely edged limestone, the main entrance, trapezoidal and once covered by a false vault, faces west, while two additional entrances point east. On the platform, there are more than 550 structures, mainly circular, with solid bases decorated with zigzag and rhombus friezes. Structures such as the Templo Mayor on the southwest side, initially called Tintero, and the Pueblo Alto to the northwest, with its imposing tower, stand out. The citadel exhibits stones carved in high relief with anthropomorphic, zoomorphic and geometric designs, found in the Main Temple, entrances and perimeter wall, as well as numerous burials in walls and circular structures (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Kuélap Monumental Archaeological Zone is located in the northeastern region of Peru, specifically in the department of Amazonas, in the Province of Luya and the District of Tingo.

3.2. Offer: Perceptions of the Offer

The target population consisted of 83 tourism service providers, including lodging businesses, restaurants, travel agencies, crafts, tourist guides, tourist transportation and muleteers in the towns of La Malca, Tingo and Chachapoyas. These towns constitute the tourist hub of Kuélap. Non-probabilistic snowball sampling was used; this sampling technique is essential when trying to reach inaccessible or hard-to-find populations. Using the survey technique, a questionnaire with two sections was applied to obtain detailed information from the respondents. Prior to its application, a pilot test was conducted in 5% of the population in order to evaluate the internal consistency and validity of the instrument.

3.3. Demand from the Sector: Analysis of the Structural Break and Effects of the Visits to Kuélap

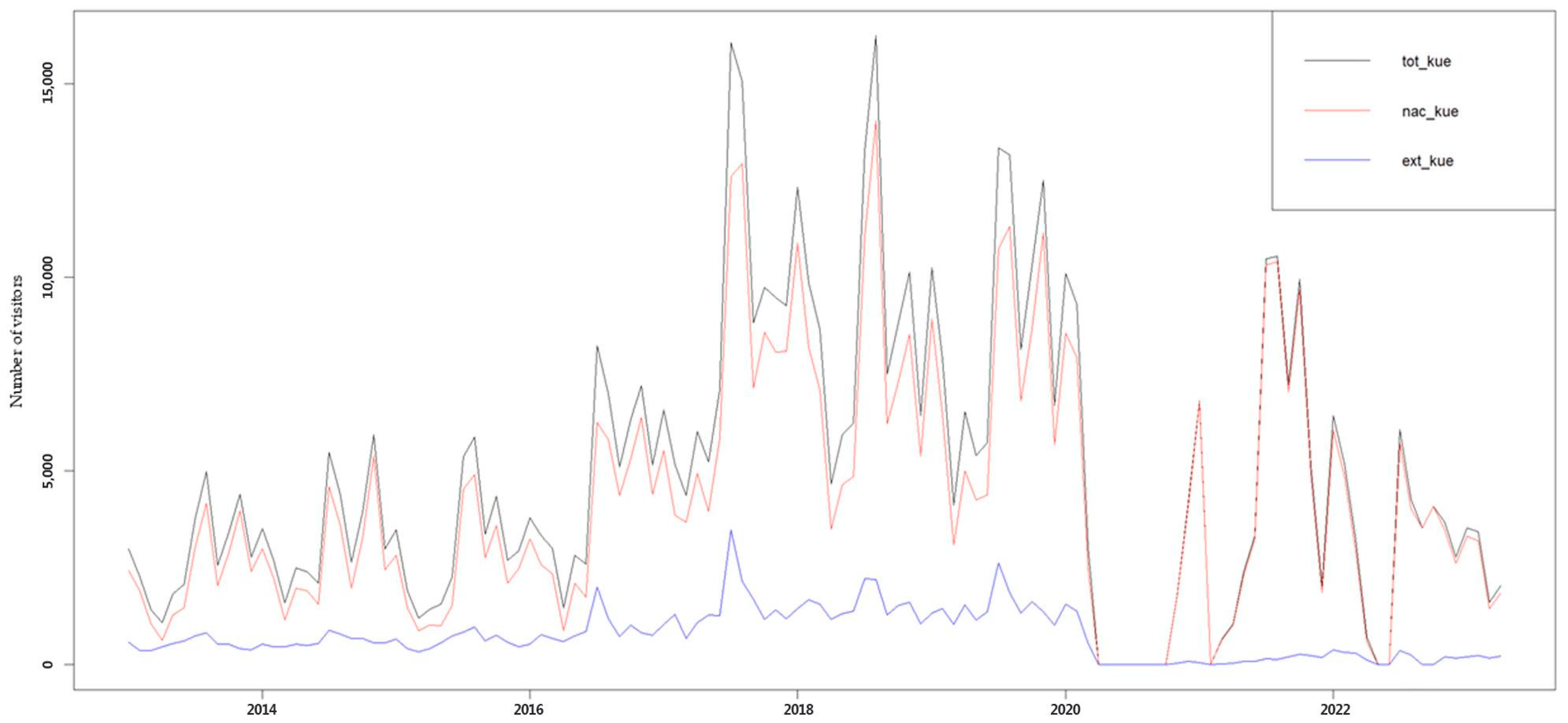

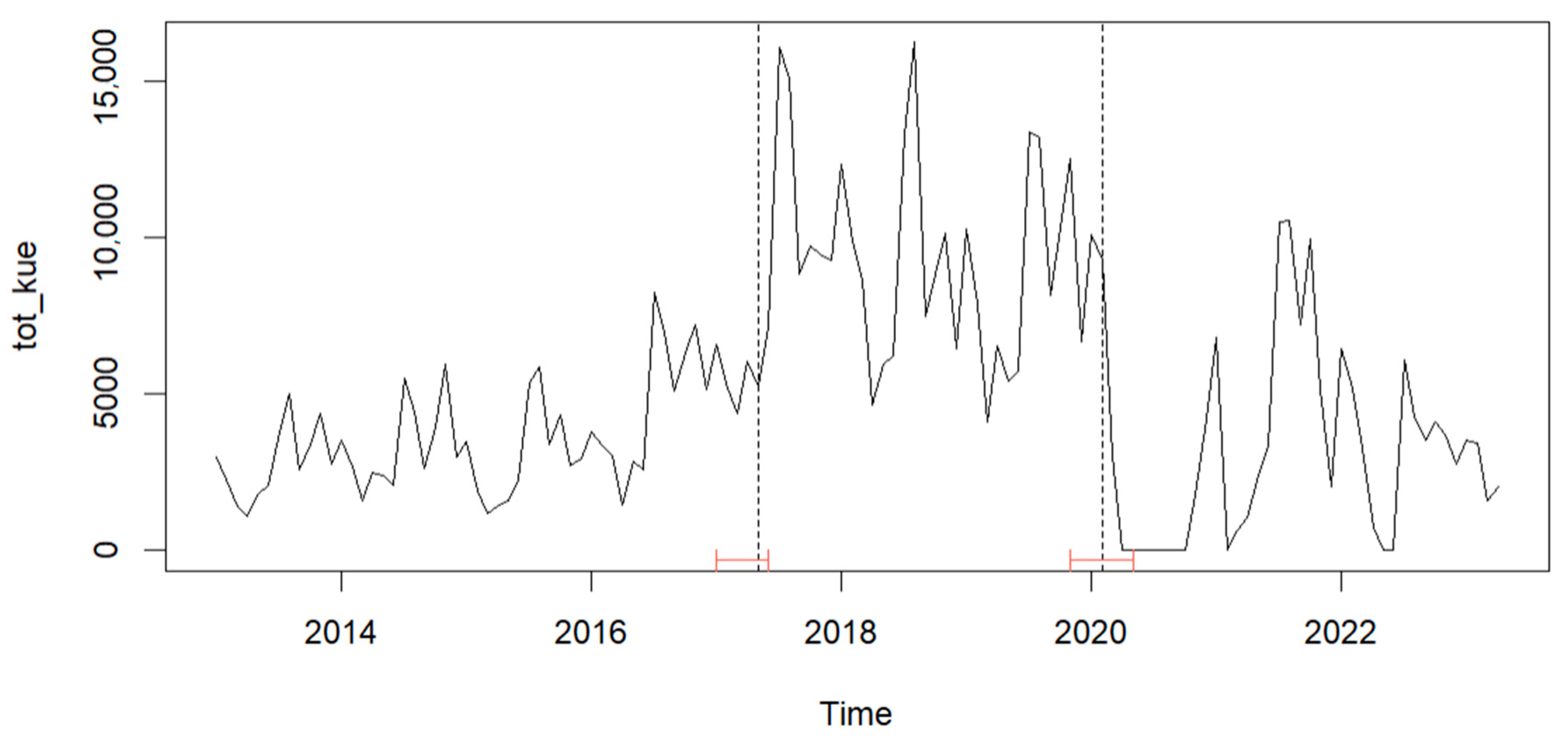

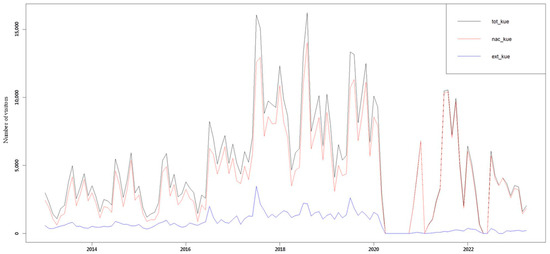

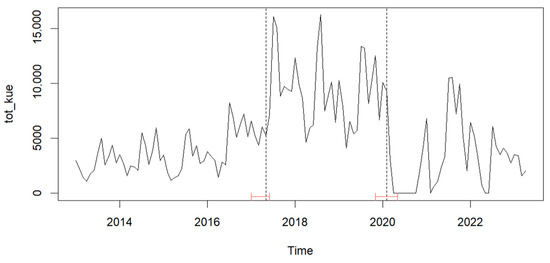

Figure 2 shows the behaviour of visits during the years 2013 and 2023. Visually, there is a significant increase in visits in 2017; while in 2020, a sharp drop is evident. The most striking aspect from 2020 onwards is that visits by foreigners are almost non-existent, and since then, the series has been composed mainly of national tourists.

Figure 2.

Evolution of visits to the Kuélap archaeological site, 2013–2023.

Quantitative analysis was carried out in three phases: in the first phase, a descriptive analysis of visits to the Kuélap archaeological site was carried out. Next, the presence of significant structural breaks in the series of interest was examined using the structural changes test based on the F-test (Strucchange package in Rstudio). Finally, the effects of the economic impact of the implementation of cable cars [ITK], the COVID-19 pandemic [PC19] and closure of Kuélap [CK] on visits were estimated using the GLS (Generalized Least Squares) method.

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Perceptions of Offers

A socioeconomic impact analysis on the perspective of tourism sector providers associated with the Kuélap archaeological site yielded the following results: 56% of the total respondents were female. In addition, it was found that 84% of them had a RUC (tax identification number) and an operating license registered in the Regional Directorate of Tourism of Amazonas (DIRCETUR). Within this group, 66% corresponded to microenterprises. This highlights the high level of the formalization of tourism sector providers in Kuélap, since the majority are microenterprises that invoice up to 742,500 soles per year. This formalization is crucial for the development of economic activity, since it allows them to validate their contracts, as well as be protected by law.

Regarding the main activities of the providers, the following stand out: restaurants (33%), lodging (28%), crafts (20%) and travel agencies (11%). In addition, it was identified that some providers also engaged in secondary activities such as restaurants, agriculture and lodging, highlighting the importance of restaurant and lodging services being part of both primary and secondary activities.

Regarding their current situation, 69.5% mentioned that they worked full time; regarding debts and loans, 64.2% did not have any debts or loans, and 68.7% had not requested credits at the present time. Also, regarding the communication aspect of their offers, the most used media were social networks (65%), telephone (38.6%) and websites (36.1%). It is noteworthy that there was an important sector that did not use any media to disseminate its products or services (27.1%).

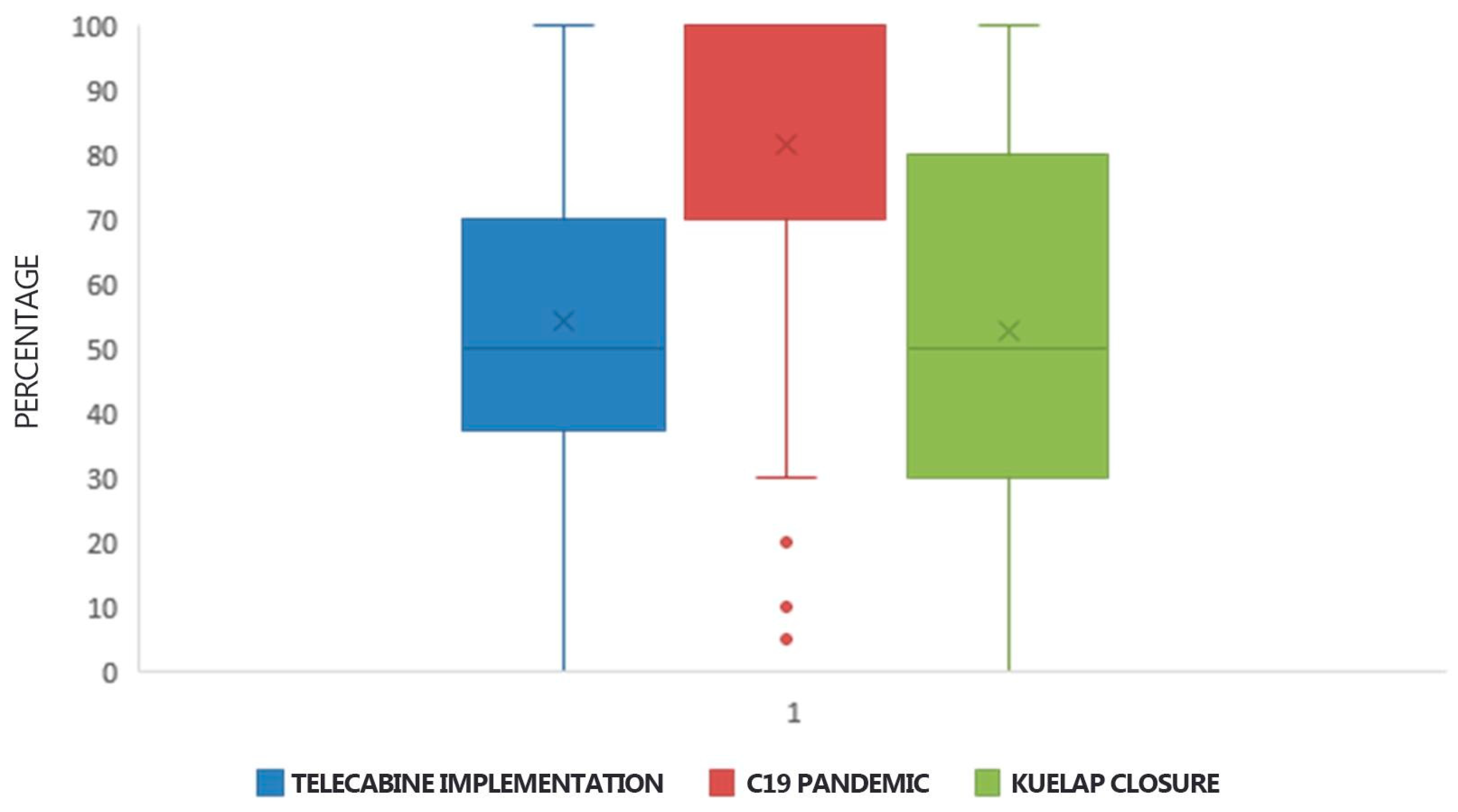

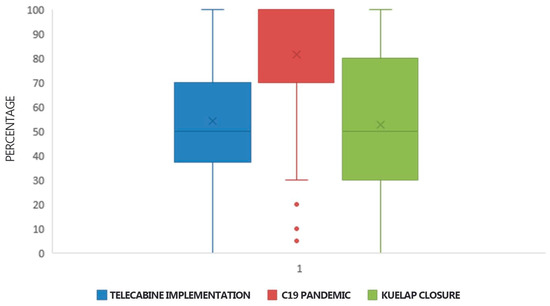

Regarding the factors that most affected sales, the perceptions were quite clear: in all cases, the main response was the high impact on sales (59.8% in the case of the economic impact of the implementation of cable cars [ITK], 74.4% for the COVID-19 pandemic [PC19] and 59% for the closure of Kuélap [CK]). However, among the negative factors, survey takers responded that it was mainly PC19 that had the greatest impact on sales (65.9%). This perception coincides with the perception of absolute variations in sales, as shown in Figure 3, where the variations were 54.2%, 81.4% and 52.9% for ITK, PC19 and CK, respectively.

Figure 3.

Perception of the absolute variation in sales.

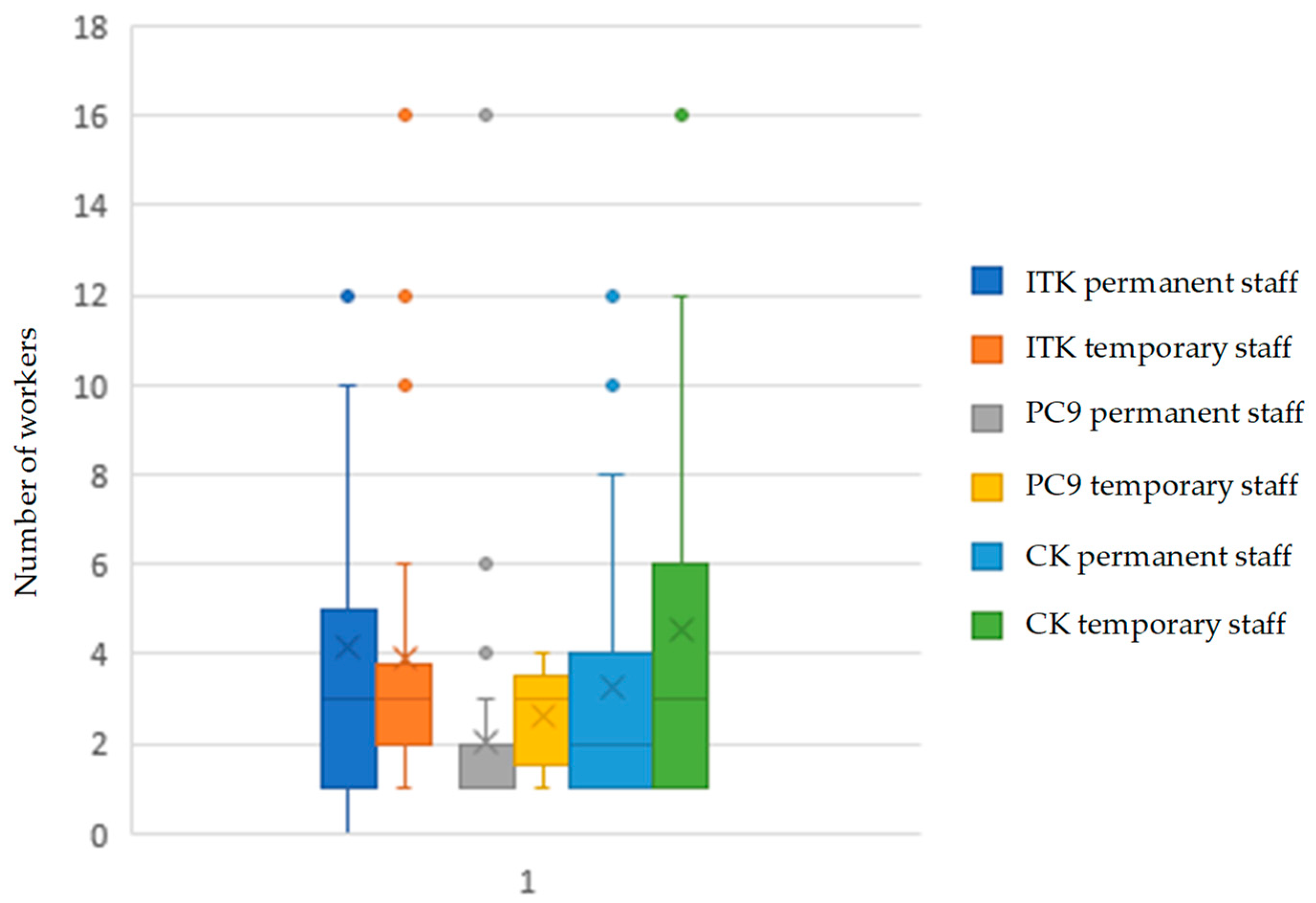

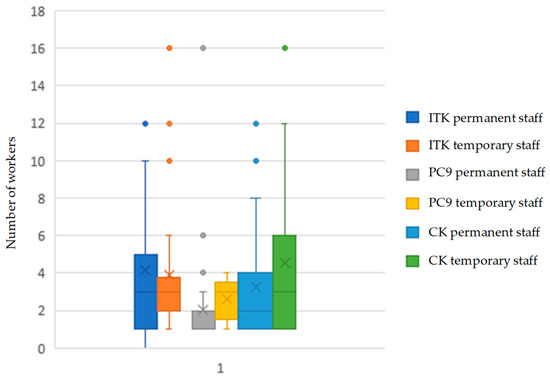

In each of the events studied, it was to be expected that people estimated the impacts and, consequently, developed strategies for hiring staff. Figure 4 shows the distribution of the number of workers for each of the events involved. Regarding permanent workers, an average of 4.2, 3 and 3.3 was observed for the economic impact of the implementation of cable cars [ITK], the COVID-19 pandemic [PC19] and closure of Kuélap [CK], respectively. On the other hand, the number of temporary workers corresponded to 3.9, 2.6 and 4.6 for ITK, PC19 and CK, respectively.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the employment of workers by type and event.

As for providers’ projections, they mainly indicated that by the year 2023, sales would decrease (41.3%); followed by those who believed that sales would remain unchanged (33.8%). Regarding the measures they would take in their current situation, 73.5% indicated that they would not make staff cuts, 71.1% would not reduce working hours, 74.7% would not request loans, 81.9% would not postpone or apply for rent reductions and 84.3% did not plan to close their offices or premises. These measures were in line with the expectations of the scenario for their business in 2023, since 87.8% projected the continuation of their business.

Finally, regarding the aspects that business owners considered positive or negative for the reactivation of tourism in their sector, the expansion of the Chachapoyas airport, an increase in commercial flights to Chachapoyas (69.9%) and the reopening of the Kuélap archaeological site were considered to have a positive influence (86.8%); those considered negative were uncertainty regarding the reopening of the Kuélap archaeological site (77.1%) and the poor state of the roads to tourism resources (59%).

4.2. Results about Visits to the Kuélap Archaeological Site

Figure 5 details the presence of structural breaks in the series analysed by means of the F-test. With a high significance (p-value = 0.000), it was estimated that the optimal partition occurred in three segments, i.e., through the presence of two structural breaks corresponding to May 2017 (i.e., January to June 2017) and February 2017 (i.e., November 2019 to May 2020).

Figure 5.

Analysis of a structural break in visits to the Kuélap archaeological site.

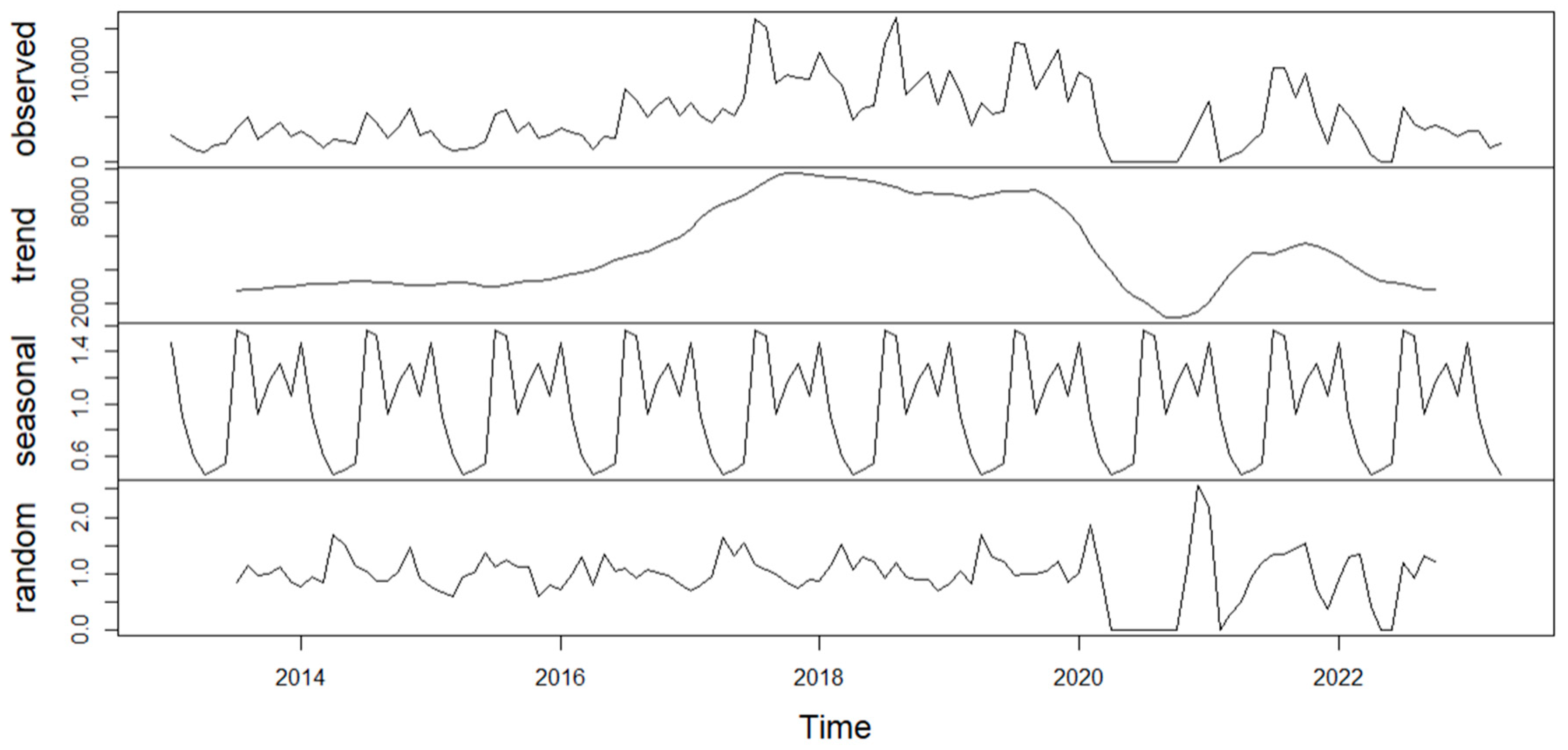

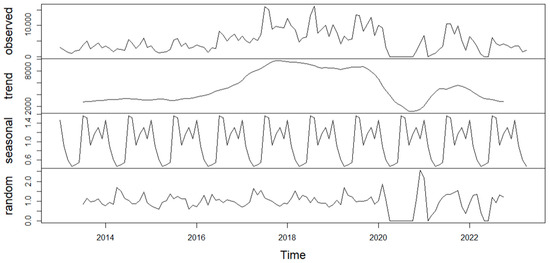

Figure 6 shows that visits to the Kuélap archaeological centre before May 2017 (the implementation of the cable car system) maintained a similar average over time. However, from this point onwards, there was the first break. Figure 5 shows an increase in the intercept of the series, keeping the slope of the series constant. The second break corresponds to the restrictive measures imposed by the government in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (February 2020). This break corresponds to a decrease in the intercept of the series, as well as in its trend.

Figure 6.

Decomposition of series of tourist visits to Kuélap, 2013–2023 (multiplicative model).

4.3. Estimation of the Effects of the Implementation of Cable Cars, the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Closure of Kuélap on Visits to the Kuélap Archaeological Site

Table 1 shows the results of the generalized least squares estimation for the visits of national tourists to Kuélap (nac_kue) and foreigners (ext_kue). The regressor variables are composed of the implementation of Kuélap cable cars (ITK), the presence of the COVID-19 pandemic [PC19] and the partial closure of Kuélap [CK].

Table 1.

Estimation results by GLS.

In the case of national visits to Kuélap, the ITK is significant (p-value = 0.004); its average impact was an increase of 3123.1 visitors. Regarding the PC19, there was also an important level of significance (p-value = 0.012), with its average effect being a reduction of 2956.6 national visits. Finally, the CK did not have a significant effect on national visits.

Regarding visits by foreigners to Kuélap, the ITK was significant (p-value = 0.000), positively affecting 603.2 visits on average. A significant effect of the PC19 was evident (p-value = 0.000), with an average reduction of 846.6 visitors. Finally, the CK showed statistical significance (p-value = 0.017) in its average reduction, which was 466.3 visits.

5. Discussion

The results of this research show that, from the perspective of structural break analysis, the factors that were significant in the series of visitors to Kuélap in the period of 2013–2023, were the implementation of cable cars and the COVID-19 pandemic. The closure of Kuélap was only mentioned as an important factor from a supply point of view.

From the supply perspective, the implementation of cable cars had a positive impact of 54% on sales and an employment rate of 4.2 permanent employees and 3.9 temporary employees on average. Regarding demand, the model estimated an increase of 3123 national visits and 603 foreign visits on average per month. It is important to highlight that the implementation of cable cars has had a significant positive impact on sales in the sector, with an increase in both national and foreign tourists, consistent with the research by Neira et al. [45], indicating that the economic impact is directly related to national tourists and that their spending increased by almost twice, directly impacting the local economy. For Rodríguez et al. [48], these changes directly have an impact on more jobs, which is consistent with the results found, indicating that each event corresponded to a different amount of labour employed. It is important to highlight that tourism in a certain place drives growth and demand for various services and goods, which allows for the generating of greater benefits for local communities [23], becoming a relevant socioeconomic mobilizer [64].

On the other hand, according to the providers, the negative impacts were mainly due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with an 81% decrease in sales and an average of 3 permanent jobs and 2.6 temporary jobs. Regarding this same fact, it was verified that demand decreased by 2957 national visitors and 847 foreign tourists per month. These impacts have generated a considerable decrease in the sales of products and services related to Kuélap. In the case of COVID-19, research by Vela and Bautista [65] and Bullemore-Campbell and Cristóbal-Fransi [66] indicates that tourism has had an impact on commercial activities and lodging establishments, as well as an increase in the production and administrative costs necessary to provide adequate service to clients. In addition, the Cepal report [67] points out the drastic dismissal of workers and decrease in wages. Regarding the United Nations policy report [68], these factors are shown to directly affect employment and sales, putting family income at risk and increasing the risk of poverty in the tourism sector.

This is related to ESAN [69] reports, which indicate that the pandemic has had a devastating impact on the tourism sector, with a 72% drop in international tourist arrivals in 2020. The study also highlights the fact that the impact of the pandemic has been uneven, most severely affecting developing countries and tourist destinations that depend on international tourism. Lončarić et al., ref. [70] conclude that the pandemic has had a significant impact on all aspects of tourism, from tourism businesses to tourism destinations. Their study also highlights the fact that the impact of the pandemic has been more severe in tourist destinations that depend on international tourism and in developing countries.

As for the presence of structural breaks in the demand for the Kuélap Monumental Archaeological Zone of Kuélap in the 2013–2023 period, the presence of structural breaks in the series was analysed using the F-test. With a high significance (p-value = 0.000), it was estimated that optimal participation occurred in three segments, i.e., through the presence of two structural breaks corresponding to May 2017 (IC: January to June 2017) and February 2017 (IC: November 2019 to May 2020). Visits to the Kuélap archaeological centre before May 2017 (the implementation of the cable car system) maintained a similar average over time; however, from this point onwards, the first break occurred. The second break corresponds to the restrictive measures imposed by the government in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (February 2020). This break corresponds to a decrease in the intercept of the series, as well as in its trend.

Tudela-Mamani et al. [41] analysed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the demand for international tourism in Peru. The authors used the Box–Jenkins methodology to estimate a time series model that describes the evolution of international tourism demand in Peru. The authors found that the pandemic has had a significant impact on international tourism demand in Peru, with a 76.8% drop in international tourist arrivals between January and October 2020.

Regarding the closure of Kuélap, the providers stated that, as a result of this closure, sales decreased by 52.9%, and employment rates of 3.3 permanent employees and 4.6 temporary employees hired on average. The demand estimate showed a significant reduction in foreign visitors by 466 on a monthly average basis, while it was not significant for national visitors. At the same time, some important data were collected on the current supply associated with Kuélap: about 30% did not communicate their offers, 66% were microenterprises and 68.7% had not requested loans despite the negative situation, which showed their refusal to leverage the financial system. It is essential to recognize that these negative structural breaks not only affected companies and employees directly related to KuélapKuélap but have also had an effect on other local economic sectors. The Regional Chamber of Tourism of Amazonas stated that 50% of the tourism businesses in the region would go bankrupt or withdraw if the closure of Kuélap persisted [71]. The decrease in tourism has an indirect impact on restaurants, hotels, transport companies and other services that depend on the influx of visitors, which generates uncertainty, loss of employment or closure of companies, as was the case of Yucatan in Mexico [37].

From the point of view of the providers and based on DIRCETUR data on visitor numbers, it was concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic has affected sales and employment even more than the closure of Kuélap.

This study showed the significant impacts that tourism has had on the regional economy, which makes it possible to state that tourism is the solution to boost the community’s economy. These results are related to those by Shang et al. [71], who argue that tourism is an appropriate solution to support developing countries. In addition, Mendoza [72] indicate that tourism is the tool for many families who can obtain income, improve the local image and provide quality service to tourists in the way that Lee and Brahmasrene [73] have outlined, regarding tourism as having a very significant direct impact on economic growth. On the other hand, climate change represents a challenge for the tourism sector and is quickly becoming a threat [74]. This is evidenced in the COVID-19 pandemic, which has generated a great crisis in international tourism [75]. From the perspective of MSMEs, COVID-19 has had a negative and significant impact on business performance and innovation capacity [76].

The study manages to identify the significant positive economic impact of the installation of the cable cars and negative impacts due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the closure of Kuélap. These results are in agreement with the study by López et al. [77], which indicate negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism sector in Spain due to the impossibility of traveling due to imposed restrictions and the closure of tourist resources. Sánchez-Rivero et al. [36] indicated disturbances in the tourism business sector in the context of COVID-19. This is also in agreement with Rudneva and Privis [78] who pointed out the positive impacts of the use of cable cars on the development of the economy and tourism in Blagoveshchensk (Russia, Amur region) and Heilongjiang province (China).

6. Conclusions

This study offers a distinctive contribution by comprehensively analysing the impacts of the implementation of cable cars, the COVID-19 pandemic and the closure of Kuélap on the tourism sector of the Amazon region. Its uniqueness lies in its meticulous consideration of both the positive and negative aspects that affect the tourism industry. Unlike other research, this study addresses the complexity of the phenomenon by closely examining the benefits generated by cable cars, such as increased sales and employment, along with the significant challenges arising from the pandemic and the closure of Kuélap. A notable feature is the inclusion of the perspective of the bidders, providing a complete view of the perceptions and experiences of the local tourism sector. The identification of structural breaks in demand, linked to specific events such as the implementation of cable cars and restrictive measures due to the pandemic, adds depth to the temporal and contextual analysis, differentiating this study by revealing the complexities that influence tourist behaviour in the region. That is, the uniqueness of this work lies in its comprehensive and detailed approach, as well as in the consideration of multiple perspectives to offer a more complete understanding of the factors that impact the regional economy, which had not been done before in the Amazon region, generating a precedent for other similar tourist resources.

As for the perspective of providers regarding the economic impact generated by the implementation of cable cars, the COVID-19 pandemic and the closure of Kuélap on the tourism sector in 2023, which are the factors that had the greatest impact on sales, the perspectives were quite clear: in all of the cases, the main response was the high impact on sales (59.8% in the case of the economic impact of the implementation of cable cars [ITK], 74.4% for the COVID-19 pandemic [PC19] and 59% for the closure of Kuélap [CK]). However, among the negative factors, survey takers responded that it was mainly PC19 that had the greatest impact on sales (65.9%). This perspective coincides with the perspective of absolute variations on sales, where the variations were 54.2%, 81.4% and 52.9% for ITK, PC19 and CK, respectively.

The closure of Kuélap has had a slight negative impact on foreign visitors but not a significant one on national visitors. This situation reduces the demand of the sector and as a consequence, reduces the services offered by the providers and employment in the tourism sector associated with the site. It is important to recognize that a temporary closure may not necessarily have significance on the demand for the tourist services that it creates and is generated around an archaeological site. This can be explained because the archaeological site serves to create a certain tourist ecosystem and no longer represents the axis of its demand.

This study showed that the tourist site of Kuélap, in the Amazonas region, is an important factor for the regional economy. It has been observed that any event that harms the archaeological site of Kuélap is reflected in a decrease in national and foreign tourists, which negatively affects tourist offers and, therefore, causes a decrease in employment and sales. This is detrimental to families’ standard of living, as well as to the growth of the local and regional economy, although most of the providers do not plan to cut salaries, wages or hours; on the contrary, the majority plan to continue operating their business.

There are various factors not studied in this research that are also determinants of the demand for the Kuélap tourist site, such as the social, economic and political context; competitive position compared to other tourist resources; and internal site administration and operation. Such factors should also be studied to holistically understand the phenomena of market variations. There is a need to establish collaborative contingency plans that involve government authorities, tourism companies and local communities, and there is a need to improve the care and conservation of Kuélap to prevent its deterioration and closure. The uniqueness of this study lies in its dual approach, addressing both supply and demand. From a supply perspective, the positive impact of cable cars on sales and employment stands out, but negative impacts are also evident, especially those related to the pandemic and the temporary closure of Kuélap. Quantifying these impacts provides a detailed understanding of the economic dynamics at play. This study contributes to current knowledge by filling an existing gap through integrating supply and demand data, providing a more complete picture of economic effects. Furthermore, by revealing important data about the current offers associated with Kuélap, it offers valuable information for future development strategies. Finally, this study sheds light on the importance of Kuélap to the regional economy and highlights the need for strategic and collaborative approaches to mitigate adverse impacts and promote the sustainability of tourism in the Amazonas region, Peru.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, data gathering, simulations and numerical tests, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, and writing—review and editing, F.O.Z.C.A., A.J.S.P., C.E.A.R., R.M.E.-H. and J.Á.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication has been funded by the Instituto de Investigación de Economía y Desarrollo, Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas, Peru. The Consejería de Economía, Ciencia y Agenda Digital de la Junta de Extremadura and by the European Regional Development Fund of the European Union through the reference grant GR21161.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sharma, A.; Kukreja, S.; Sharma, A. Role of tourism in social and economic development of society. Int. J. Adv. Res. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2012, 1, 10–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalič, T. Economic impacts of tourism, particularly its potential contribution to economic development. In Handbook of Tourism Economics: Analysis, New Applications and Case Studies; World Scientific: Singapore, 2013; pp. 645–682. [Google Scholar]

- Bunghez, C.L. The importance of tourism to a destination’s economy. J. East. Eur. Res. Bus. Econ. 2016, 2016, 143495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, F.; Rahmati, M.; Karimi, A. Contribution of tourism to economic growth in Iran’s Provinces: GDM approach. Future Bus. J. 2018, 4, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamel, L. The relation between tourism and economic growth: A case of Saudi Arabia as an emerging tourism destination. Virtual Econ. 2020, 3, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanquey, Y.; Lagos, N.; Llanco, C. Análisis del crecimiento económico en función del turismo en Chile, periodo 2000–2018. Rev. Interam. Ambiente Tur. 2021, 17, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, S.; Page, S.J.; Buhalis, D. Social media as a destination marketing tool: Its use by national tourism organisations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, 16, 211–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaoutzi, M. Tourism and Regional Development; Giaoutzi, M., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaya, H.; Kang, M. Turismo metaverso para el desarrollo turístico sostenible: Agenda turística 2030. Tour. Rev. 2023, 78, 381–394. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobo-Hernández, C.A.; Leyva-Osuna, B.A.; Daniel Ochoa, Y.J.; Mendoza Apodaca, M.d.R. La influencia del capital intelectual en el desempeño organizacional en empresas turísticas de México. Rev. Interam. Ambiente Tur. 2019, 15, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Asif, M.; Haq, M.Z.U.; Rehman, H.U. The contribution of sustainable tourism to economic growth and employment in Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Narváez, C.F.; González-Sanabria, J.S.; Cáceres-Castellanos, G. Toma de decisiones en el sector turismo mediante el uso de Sistemas de Información Geográfica e inteligencia de negocios. Rev. Científica 2020, 38, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, M.J.; Breda, Z.; Cordeiro, C. Sports tourism development and destination sustainability: The case of the coastal area of the Aveiro region, Portugal. In Sport Tourism and Sustainable Destinations; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 143–172. [Google Scholar]

- Garrigos-Simon, F.J.; Narangajavana-Kaosiri, Y.; Lengua-Lengua, I. Tourism and sustainability: A bibliometric and visualization analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibănescu, B.C.; Stoleriu, O.M.; Munteanu, A.; Iațu, C. The impact of tourism on sustainable development of rural areas: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, M.D.; Longley-Wood, K.; McNulty, V.P.; Constantine, S.; Acosta-Morel, M.; Anthony, V.; Cole, A.D.; Hall, G.; Nickel, B.A.; Schill, S.R.; et al. Nature dependent tourism—Combining big data and local knowledge. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 337, 117696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén Herrera, S.R.; Vera Peña, V.M. Impacto de la tecno ciencia en la gestión del marketing del turismo comunitario. Rev. Univ. Soc. 2020, 12, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Bibi, S.; Lorenzo, A.; Lyu, J.; Babar, Z.U. Tourism and development in developing economies: A policy implication perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Momsen, J.H. Tourism and poverty reduction: Issues for small island states. In Tourism and Sustainable Development Goals; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Streimikiene, D.; Svagzdiene, B.; Jasinskas, E.; Simanavicius, A. Sustainable tourism development and competitiveness: The systematic literature review. Sustain. Develop. 2021, 29, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango-Marín, M. Transformación urbana reciente y turismo globalizado en el centro de Medellín. An. Investig. Arquit. 2022, 12, e311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erul, E.; Woosnam, K.M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Salazar, J. Complementing theories to explain emotional solidarity. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 31, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, P. Tourism Impacts, Planning and Management: Fourth Edition; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutty, M.; Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. The global effects and impacts of tourism: An overview. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 36–63. [Google Scholar]

- Postma, A.; Schmuecker, D. Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: Conceptual model and strategic framework. J. Tour. Futures 2017, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero Rescalvo, M.; Jover Báez, J. Paisajes de la turistificación: Una aproximación metodológica a través del caso de Sevilla. Cuad. Geográficos 2020, 60, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can Leeuwen, E.S.; Piet Rietveld, P.N. Economic Impacts of Tourism: A Meta-Analytic Comparison of Regional Output Multipliers, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogendoorn, G.; Fitchett, J.M. Tourism and climate change: A review of threats and adaptation strategies for Africa. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 742–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomatis, F. Análisis de posibles repercusiones del cambio climático sobre el Camino de Santiago Francés en su paso por Castilla y León (España). Rev. Interam. Ambiente Tur. 2020, 16, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, J.C.; Acevedo-Navas, C. Diagnóstico de riesgos en el sector turístico latinoamericano para el trienio 2020–2022. Rev. Científica Gen. José María Córdova 2021, 19, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo Arcos, L.; Moo Canul, M.d.J.; Segrado Pavón, R.G. Percepción social del aprovechamiento turístico en áreas naturales protegidas. Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Tur. 2022, 16, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Driha, O.M.; Shahbaz, M.; Sinha, A. The effects of tourism and globalization over environmental degradation in developed countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 7130–7144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vithayaporn, S.; Nitivattananon, V.; Sasaki, N.; Santoso, D.S. Assessment of the Factors Influencing the Performance of the Adoption of Green Logistics in Urban Tourism in Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos Vargas, M.; Castillo Ramiro, J.J. Estimación de la Capacidad de Carga Turística en Agua Selva (Tabasco–México): Base para la planificación y el desarrollo regional. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2018, 27, 295–315. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.ar/pdf/eypt/v27n2/v27n2a06.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Alonso-Muñoz, S.; Torrejón-Ramos, M.; Medina-Salgado, M.-S.; González-Sánchez, R. Sustainability as a building block for tourism—Future research: Tourism Agenda 2030. Tour. Rev. 2023, 78, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rivero, M.; Rodríguez-Rangel, M.C.; Ricci-Risquete, A. Percepción empresarial de la pandemia por COVID-19 y su impacto en el turismo: Un análisis cualitativo del destino Extremadura, España. Estud. Gerenciales 2021, 37, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enseñat Soberanis, F. Uso turístico del patrimonio arqueológico en la península de Yucatán: Una visión desde los actores involucrados en Tulum y Cobá. Península 2020, 16, 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, I.L. COVID-19: How can travel medicine benefit from tourism’s focus on people during a pandemic? Trop. Dis. Travel Med. Vaccines 2022, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R.; Whitsed, R. The impact of COVID-19 on the Australian outdoor recreation industry from the perspective of practitioners. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 41, 100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatibura, D.M.; Motshegwa, N. Developing Virtual Tourism in the Wake of COVID-19: A Critical Function of Tourism Destination Management Organizations. In Teaching Cases in Tourism, Hospitality and Events; CABI: London, UK, 2023; pp. 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudela-Mamani, J.W.; Cahui-Cahui, E.; Aliaga-Melo, G. Impacto del COVID-19 en la demanda de turismo internacional del Perú. Una aplicación de la metodología Box-Jenkins. Rev. Investig. Altoandinas J. High Andean Res. 2022, 24, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sann, R.; Lai, P.-C.; Chen, C.-T. Crisis Adaptation in a Thai Community-Based Tourism Setting during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Phenomenological Approach. Sustainability 2022, 15, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINCETUR. Reporte Regional de Turismo Amazonas. 2022. Available online: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/4331692/Reporte%20Regional%20de%20Turismo%20Amazonas%20A%C3%B1o%202022.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Zheng, H. Influencing factors of regional tourism eco-efficiency under the background of green development in the western China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 3512–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira Córdova, O.L.; Choy Chea, J.M.; Mory Olivares, C.E. Impacto de la Implementación de la Telecabina de Kuélap en el Turismo de la Región Amazonas; Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas: Lima, Peru, 2018; pp. 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- Bieszk-Stolorz, B.; Dmytrów, K.; Eglinskiene, J.; Marx, S.; Miluniec, A.; Muszyńska, K.; Niedoszytko, G.; Podlesińska, W.; Rostoványi, A.V.; Swacha, J.; et al. Impact of the availability of gamified e-guides on museum visit intention. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 192, 4358–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, A.; Will, E. Análisis del Impacto Económico del Sistema de Telecabinas KUÉLAP en el Turismo de la Región de Amazonas, Periodo 2017–2018 [Registo Nacional de Trabajo de Investigación]. 2019. Available online: https://repositorio.epneumann.edu.pe/xmlui/handle/EPNEUMANN/120 (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Rodríguez, M.; Ricart, J.E.; Fageda, X. Telecabinas Kuélap (Perú) 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.iese.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/ST-0469.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- O’Malley, L.; C Harris, L.; Story, V. Managing Tourist Risk, Grief and Distrust Post COVID-19. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2023, 23, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez, J.A.; Lorenzo, P.d.A.; Cañizares Pacheco, E. Estudio de Impacto Económico. Estudio de Impacto Económica. 2012. Available online: https://www.pwc.es/es/sector-publico/assets/brochure-estudios-impacto-economico.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Scarlett, H.G. Tourism recovery and the economic impact: A panel assessment. Res. Glob. 2021, 3, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyadi, H.S.; Newsome, D. The post COVID-19 tourism dilemma for geoparks in Indonesia. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2021, 9, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza Huamanchumo, R.M.; Gamarra Flores, C.E.; Ángeles Barrantes, D. El ecoturismo como reactivador de los emprendimientos locales en áreas naturales protegidas. Rev. Univ. Soc. 2020, 12, 436–443. [Google Scholar]

- García-Romero, L.; Carreira-Galbán, T.; Rodríguez-Báez, J.Á.; Máyer-Suárez, P.; Hernández-Calvento, L.; Yánes-Luque, A. Mapping Environmental Impacts on Coastal Tourist Areas of Oceanic Islands (Gran Canaria, Canary Islands): A Current and Future Scenarios Assessment. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Zhu, Y.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, G.; Gu, S.; Shen, Q.; Meshram, S.G.; Alvandi, E. Identification and Prioritization of Tourism Development Strategies Using SWOT, QSPM, and AHP: A Case Study of Changbai Mountain in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairy, H.A.; Elzek, Y.; Aliane, N.; Agina, M.F. Perceived Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility Effect on Green Perceived Value and Green Attitude in Hospitality and Tourism Industry: The Mediating Role of Environmental Well-Being. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S. Mental Health of Tourism Employees Post COVID-19 Pandemic: A Test of Antecedents and Moderators. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 626–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavaleta Chavez Arroyo, F.O.; Sánchez Pantaleón, A.J.; Navarro-Mendoza, Y.P.; Esparza-Huamanchumo, R.M. Community Tourism Conditions and Sustainable Management of a Community Tourism Association: The Case of Cruz Pata, Peru. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdek Pereira, C.M.; Reis Gonçalo, C.; Terezinha Coelho, T. La capacidad relacional como movilizadora de negocios para el turismo de eventos. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2020, 29, 730–748. [Google Scholar]

- Beltami, D.; Barbini, F. Sistema de Calidad en Turismo: Posibilidades y Restricciones de su Implementación en Mar de Plata [Universidad Nacional Mar de Plata]. 2011. Available online: http://nulan.mdp.edu.ar/id/eprint/1330/1/castellucci_di.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Restrepo Abondano, J.M.; Guerrero Orozco, J.; Olaya Cantor, N.C. Política Desarrollo Sostenible. 2020. Available online: https://www.mincit.gov.co/minturismo/calidad-y-desarrollo-sostenible/politicas-del-sector-turismo/politica-de-turismo-sostenible/documento-de-politica-politica-de-turismo-sostenib.aspx (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Valle Pérez Colmenares, S. La planificación y prevención de los impactos ambientales del turismo como herramienta para el desarrollo sostenible: Caso de estudio Timotes, Venezuela. Rev. Interam. Ambiente Tur. 2017, 13, 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Palacio, M.; Castaño-Molina, V. La promoción turística a través de técnicas tradicionales y nuevas una revisión de 2009 a 2014. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2015, 24, 737–757. [Google Scholar]

- Maneejuk, P.; Yamaka, W.; Srichaikul, W. Tourism Development and Economic Growth in Southeast Asian Countries under the Presence of Structural Break: Panel Kink with GME Estimator. Mathematics 2022, 10, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela Cuipal, E.M.; Bautista Núñez, J. Impacto Económico Del COVID-19 En El Sector Hotelero De La Ciudad De Chachapoyas, 2020–2021. Horiz. Empres. 2022, 9, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullemore-Campbell, J.; Cristóbal-Fransi, E. La dirección comercial en época de pandemia: El impacto del COVID-19 en la gestión de ventas. Inf. Tecnológica 2021, 32, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepal, N. Evaluación de los Efectos e Impactos de la Pandemia de COVID-19 Sobre el Turismo en América Latina y el Caribe: Aplicación de la Metodología para la Evaluación de Desastres (DaLA). 2021. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/46551/1/S2000674_es.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- United Nations. Informe de Políticas: La COVID-19 y la Transformación del Turismo. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2020/10/policy_brief_covid-19_and_transforming_tourism_spanish.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- ESAN. Cierre de Kuélap: ¿Cómo Afecta al Turismo en Amazonas? ATV. 2023. Available online: https://www.esan.edu.pe/conexion-esan/cierre-de-Kuélap-como-afecta-al-turismo-en-amazonas (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Lončarić, D.; Popović, P.; Kapeš, J. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review. Tourism 2022, 70, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Bi, C.; Wei, X.; Jiang, D.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Rasoulinezhad, E. Eco-tourism, climate change, and environmental policies: Empirical evidence from developing economies. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza Loayza, E.C. Gestión del Turismo Rural Comunitario y Satisfacción del Turista en la Comunidad de Janac Chuquibamba Distrito de Lamay Provincia de Calca. [Universidad San Martin de Porras]. 2018. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12727/4593 (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Lee, J.W.; Brahmasrene, T. Tourism effects on the environment and economic sustainability of sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Sustain. Develop. World Ecol. 2016, 23, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoulinezhad, E.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Role of green finance in improving energy efficiency and renewable energy development. Energy Effic. 2022, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somoza Medina, X. Turismo internacional y pandemia. Análisis comparativo de Cancún y Mallorca. Investig. Turísticas 2023, 25, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, N.S.; Rahmayanti, P.L.D. The role of innovation capability in mediation of COVID-19 risk perception and entrepreneurship orientation to business performance. Uncertain Supply Chain. Manag. 2023, 11, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.; Del Vas, G.; Cabrera, M. Impact of the Pandemic on Tourism and Transport in Mediterranean Regions. The Case of Murcia, Spain. Rev. Geogr. Venez. 2023, 64, 36–45. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85174592180&partnerID=40&md5=b6ccbba102f33521b282dcd57f4bb6d4 (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Rudneva, Z.S.; Privis, S.S. Teleférico Transfronterizo: Nuevas Oportunidades, Tecnologías y Perspectivas Para la Cooperación Cercana a la Frontera. In En Actas de la Conferencia AIP; Publicación AIP: New York, NY, USA; Volume 2476, Number 1; Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85160534910&doi=10.1063%2f5.0105967&partnerID=40&md5=5205c144f45eba4b87b09435ea9925a2 (accessed on 15 December 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).