Abstract

Rent regulation has a significant impact on tenant–landlord relations and the overall functioning of the private rented sector. Different forms of rent regulation—in relation to rent levels, rent increases, security of tenure, etc.—also affect the quality, the social composition and, ultimately, the size of the private rented sector. Together they affect the character of much urban regeneration and renewal. The introduction in Portugal of more flexible rent regimes that aimed to gradually replace open-ended tenancies with freely negotiated contracts led researchers to classify the country as a free market system. In this paper, by using a mixed methods approach that combined desk-based research with census data and in-depth interviews, we test the) classification of Portugal’s rented sector as a free market against empirical evidence and examine the impacts of the main rent regulation regimes on social sustainability-oriented urban regeneration. Our results show that open-ended contracts, which were signed before the 1990s, still account for a significant part of the private rented sector, thus the classification of Portugal’s rent regulation regime as a free-market system does not capture the country’s most significant features. This is particularly evident in inner-city Lisbon, where various extreme rent regimes (in terms of contract duration, tenant security and prices) coexist, giving rise to tensions between housing quality and demographic shifts that threaten the overall social sustainability of the city.

1. Introduction

There is a vast body of literature that compares different types of—and rationales for–government rent regulation and examines its (long-lasting) effects upon markets [1]. The body of literature that has observed that rent regulation, which has been described as “rent policy in which rents are controlled below theoretical market levels” [2] (p. 46), is linked to other regulation that affects tenant—landlord relations, such as that which deals with tenant security and contract duration. A basic distinction can be made between fixed or definitive contracts versus open-ended contracts [3].

There is also regulation, which is typically formalised within legislative frameworks, concerning the circumstances or events that justify the termination of a lease, and the efficacy of enforcement mechanisms (inside or outside the legal system) for dispute resolution. For example, when tenants breach the terms of the contract, such as in cases of persistent delayed rent payments or property damage.

The comparison of regulatory environments across countries and over time has enabled the identification of different regimes of rent regulation, from the point of view of how rigidly they regulate rent increases and/or set initial rents, or how they have (or have not) been associated with other forms of social or economic support, such as exemptions from landlord fees, or tenants’ housing allowances [4].

Studies have also shown the importance of correctly calibrating rent regulation and tenancy security. On the one hand, there is evidence that overly strict rent regulations can protect tenants from rent increases, but not necessarily from poor housing conditions. As they limit profitability for private rental landlords, they tend to discourage building improvement and maintenance [5] as well as further investments in the sector, thus limiting housing supply. Overly strict rent price protection can also have other negative consequences for the housing market, such as the growth of informal markets, and mismatches between dwellings size and family needs, with small households occupying large dwellings, and large households unable to find larger dwellings that satisfy their need [6,7]. On the other hand, there is also evidence from Germany and Switzerland that rent controls can be compatible with the development of a rental market that protect tenants from eviction and excessive rent increases, and that allows landlords to make enough profit [8]. Whitehead et al. [9] note that strong tenancy protection is a precondition for long-term demand for rental dwellings, as lower tenant security pushes more consumers towards the owner-occupied secure. Whitehead and Williams [10] also note the relevance of path dependency (the influence of past events on the present and future) and that sudden large changes in policy can take a long time to take full effect.

Studies at the local level have additionally looked at the impact of rent regulation changes on particular social groups and geographical areas, such as inner cities (characterized by an old housing stock, high incidence of renting rather than ownership and elderly populations), specifically insofar as these changes affect population dynamics, building quality, etc. [11,12,13]. These studies have also scrutinized the role of rent regulation in the context of wider urban regeneration [14] and urban land-use policies [15]. However, as far as we are aware, this is the first study (albeit preliminary) dedicated to exploring the effects of diverse rent regulation regimes on the dynamics of physical and social transformation in Portugal. This paper pursues two objectives, seeking to make a significant contribution by addressing and bridging this gap.

Firstly, this paper aims to deepen understanding of the Portuguese rent regulation system by providing a more nuanced, comprehensive and accurate characterization. In a recent classification of 33 European countries based on their rent regulation system and welfare state regime, Kettunen and Ruonavaara [16] identify Portugal as a country with a free rent market. For this classification the authors chose to exclude rent regulation for pre-1990 leases, a methodological criterion which, although valid, was not tested against empirical data. In this paper we answer two research questions related to this classification: 1. What is the prevalence of pre-1990s contracts in the private rental sector (PRS) in terms of households and dwellings, and how do the characteristics of the current rent negotiation system, when applied to these contracts, impact rent increases and housing quality? 2. Does the classification of Portugal’s rent regulation regime as a free-market system capture its most significant features?

Secondly, this paper investigates the effects of the rent regulation regimes implemented during recent decades on social sustainability-focused urban regeneration in inner-city Lisbon. This objective is achieved through answering the following research question: 3. How do the 2006 and 2012 reforms influenced the relationships between tenants and landlords, the overall functioning of the PRS, and urban regeneration processes in inner-city Lisbon, and were they focused on social sustainability?

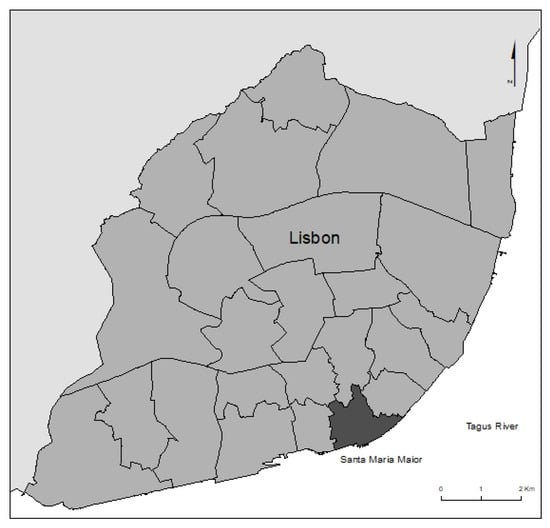

In the context of this study, the “inner-city” refers to the administrative boundaries of the parish of Santa Maria Maior (SMM), created in 2012, one of the six parishes within the historical centre of Lisbon. The selection of the case study can be justified on several grounds related to the area’s specific features. First, it is in an attractive territory in the heart of Lisbon, which is composed of the well-known traditional neighbourhoods of Alfama, Chiado, Castelo and Mouraria. Secondly, it has high proportions of private rental housing, open-ended contracts and low rents, suggesting the effect of rent regulation over time and the potential impact that schemes aimed at updating rents can have in this area. Thirdly, the resident population in SMM has high levels of social vulnerability (e.g., economic deprivation, aged population).

2. Rent Regulation: A Key Housing Policy Instrument

Rent regulation is a housing policy instrument that aims to keep rents below a theoretical market level. It can be described as a restrictive government policy, although, as Clarke and Oxley [17] point out, it has been associated with other instruments, such as subsidies (in different forms) that seek to expand housing supply, improve affordability, satisfy certain quality standards and assure security and access for households in poverty. For example, rent regulation has been linked to housing allowances that are subsidies tied to housing which are paid to consumers or directly to landlords or mortgage lenders on the consumers’ behalf. In several countries (such as the UK or Denmark) low-income households in the PRS are entitled to housing benefits. Scanlon [18] stipulates that government housing subsidies covers around 35% of households in the PRS.

Rent regulations, which are formulated and implemented in the context of specific power relations, are guided by different ideals and objectives, (such as those of market efficiency and social protection, a mix of these) and have a significant impact on the overall operation of the PRS [19]. This is important for several complementary reasons. On the one hand, private rental has traditionally been an important type of tenure for low-income families [20,21], thus errors in the sector’s regulation can have major consequences, not only for more vulnerable families, but also for levels of cohesion, which are linked to socio-spatial segregation processes. On the other hand, the PRS has been a destination for global real estate investment in search of greater profitability [22,23], which has led to the proliferation of second homes, that are linked to seasonal uses and short-term rentals and had facilitated by the co-existence of two urban phenomena: overheated housing markets and major ‘rent gaps’ centred and dependent on the dynamics of tourism development.

Urban regeneration has been a priority in neighbourhoods where a decades-long absence of public and private investment has contributed to their general degradation and the dilapidation of buildings. Regeneration projects attempt to improve the image of these places in order to attract new inward investment in social, economic and green infrastructure, as well as middle-high income people to these neighbourhoods. Urban regeneration involves a series of environmental, economic, social and cultural improvements that generally increase land and real estate values, resulting inadvertently in displacement, gentrification, decreasing liveability and an increasing need for affordable housing [24].

Urban rehabilitation, meanwhile, is a more specific process of urban transformation. It too is prompted by the degradation of urban buildings, but is limited to the conservation, recovery and retrofitting of buildings and urban spaces to provide—as in urban regeneration—better living conditions for their inhabitants, while maintaining the basic structural scheme and the original exterior appearance of buildings and urban spaces. Although urban rehabilitation can range from simpler to more complex interventions, it is never as broad and deep as urban regeneration.

A sustainability-oriented urban regeneration approach should be able to connect the stimulation of economic growth and environmental enhancement with social and cultural vitality, and seeks to achieve social sustainability at the community or local level [25]. Social sustainability depends on how individuals, communities and societies live with each other and set out to achieve the objectives of urban development, taking into account the physical and social limits and potentialities of their places and communities. At a more operational level, social sustainability stems from actions in key thematic areas—encompassing the economic, environmental and cultural spheres—which range from capacity building and skills development to tackling environmental and spatial inequalities. Thus a social sustainability approach brings together traditional social policy areas and principles—such as equity, housing and health; the built environment and heritage; and identity, sense of place and culture—with emerging issues—such as participation, empowerment and access; social capital; social mixing and cohesion; and well-being and quality of life. These are critical areas for the social sustainability of local communities and neighbourhoods, and it is of fundamental importance to assess the potential direct and indirect impact that proposed urban regeneration projects are likely to generate for them, in order to prevent displacement and gentrification in terms of housing and local economic activities and services [26,27]. These areas have become the focus of an international interest in social sustainability, a concept that is increasingly being used by governments, public agencies, policy makers, NGOs and corporations to frame decisions about urban development, regeneration and housing, as part of a burgeoning policy discourse on the sustainability and resilience of cities, and is also associated with the different impacts of rent regulation regimes [28].

International comparative analyses have identified different generations of rent regulation. Whilst some authors have distinguished between a first and a second generation of rent regulation, more recently others have opted to add a third ideal type. In the first group are Priemus [2] or Haffner et al. [5] for whom the first generation of rent regulation (implemented during the First and Second World Wars) consisted of either the application to all rents of nominal rent caps, or the limiting of all yearly rent increases to below the inflation rate. This was a very restrictive instrument or, in Priemus’ [2] words, a sort of emergency-braking system. The second generation of rent regulation, introduced in several countries in the 1980s, was a gradual relaxation or softening of the previous long-standing hard controls. It allowed rents to increase annually, by a certain percentage, or by supplementary additional discretionary rises in response to some combination of landlord cost increases and profitability concerns. Lind [29] identify two dimensions along which the second generation of rent regulation may vary: (i) the type of contracts subject to regulation—existing vs. new rental contracts; and (ii) the basis for rent regulation—cost-based vs. market based. In relation to the former, while some countries have applied regulation to both existing and new contracts, limiting what landlords can charge when letting residential property, in other countries regulation has been restricted to existing contracts.

Looking at these differences, Kettunen and Ruonavaara [16] opted to add a third generation of rent regulation and to apply it to the classification of 33 countries. In their own words: “If both initial rents and rent increases were regulated, it was classified as second-generation rent control. If only rent increases were regulated, it was classified as third-generation rent control” (p. 16). Even though they recognized that the range of second- and third-generation rent regulations was not always clear cut, and that in many countries the former is only applied to some parts of the housing stock (e.g., in larger cities or areas of high demand), they were able to distinguish between a second generation of rent controls (applied both to initial rents for new lettings and rent increases within tenancies) and a third generation of rent controls, which constitute a much lighter form of regulation applied solely within an individual tenancy.

The work of Kettunen and Ruonavaara [16], which likens the typology of four distinct welfare regimes [30] to the typology of three generations of rent regulation, provides a good illustration of the relevance of ‘ideal types’ for building theory and guiding the formation of hypothesis [31,32]. It also illustrates the importance of testing hypotheses against statistical data, as the authors did for the Nordic countries. More questionable, however, is Kettunen and Ruonavaara’s [16] decision to exclude from the classification of other countries (such as Portugal) what they designate as “old strict laws” that “are still applied to rental contracts dated before the 1990s” (Idem, p. 6). In the end Portugal is classified as a country with a free rent market. An idea that became somehow common in some political and academic debates that over the last decades governments have almost complete liberalized or abolished rent controls in Portugal.

3. Materials and Methods

In this paper, we employ a mixed methods approach that combines desk-research of the grey literature with the analysis of census data and in-depth interviews to address our research questions. First, we review technical reports, legislation, scientific publications and non-scientific sources in order to provide a brief history of rent regulation in Portugal. Next, to evaluate the weight of pre-1990s contracts in the private rental sector and its effects (research question 1), and to understand whether the Portuguese rent regime may be classified as a free market system (research question 2), we look at the 2011 Census data at the national and local level. This allows us to witness the cumulative effects of decades of rent regulation on the PRS, with a specific focus on the repercussions of the 2006 rent regime on urban regeneration processes, particularly regarding housing quality and various aspects of social sustainability. It also offers the profile of the PRS at three geographical scales—Portugal, Lisbon and SMM—one year before the introduction of the 2012 rent regime, regarding several variables such as the type/duration of contracts, rent prices, dwellings conditions, or age and socioeconomic group of the tenants. Due to the reorganization of Lisbon’s parishes in 2012, the area of SMM was derived from the 2011 Census data of the 12 constituent parishes that formed SMM (Castelo, Madalena, Mártires, Sacramento, Santa Justa, Santiago, Santo Estêvão, São Cristóvão e São Lourenço, São Miguel, São Nicolau, Sé and Socorro). Regarding census data, it worth noting that: (i) censuses in Portugal do not collect data on income, which explain the use of the socio-economic group as a proxy for income in this study; (ii) most information on the rental sector do not distinguish private from social rental sectors; and (iii) that, to guarantee the anonymity and confidentiality of individuals in territories with a small number of residents, as it happens in some inner centre neighbourhoods, there is a limit to the number of variables that can be combined. Nevertheless, the use of 2011 Census data is crucial to examine processes of change at fine spatial scales of analysis, and to examine the long-run impacts of policies within the city, including the residential patterns of various social groups, such as spatial distribution by tenure, price and quality.

Finally, in order to discuss the influence of recent reforms on the relationships between tenants and landlords, the overall functioning of the PRS and urban regeneration processes in inner-city Lisbon, as well as their connection to social sustainability (research question 3), we analyse data collected from five in-depth interviews. Table 1 provides a summary of the main characteristics of the interviewees.

Table 1.

Interviewees institutional affiliations.

In this paper, the use of mixed methods was crucial to overcome limitations arising from the absence of administrative data concerning various aspects, such as contract numbers, evictions and the characteristics of new contrasts.

4. A Brief History of the Rent Regulation in Portugal

Rent control was first introduced in Portugal in 1910 and since then has been used both to control the initial rent that landlords can charge and any subsequent increases [33]. The main rent freezes occurred in 1948 in the cities of Lisbon and Porto and were extended in 1974 to the whole country [34], a context of national and international economic crisis. In the 1980s, several timid initiatives were established to restore the normal operation of the rental market. Although the government established criteria for annual rent updates based on coefficients, the high inflation of the 1970s and 1980s made these derisory, amplifying the discrepancy between existing contracts and new tenancies. Low rents meant a poor economic return for landlords who had no incentive to carry out the necessary conservation works, increasing the dereliction of buildings in the oldest parts of the main Portuguese cities.

In 1990, with the Urban Lease Regime (Regime do Arrendamento Urbano/RAU–DL n. 321-B/90), there is the first major legislative reform that aims to boost the private rental market, through the introduction of fixed-term contracts (see Table 2). Until then the only permitted type of rental contract was the open-ended contract, which was very difficult for landlords to terminate. For example, landlords were not entitled to repossess the property if they needed it for their own habitation, and contracts did not expire after the property was sold or the landlord died. Since it was only after 1990 that contracts could be agreed for a fixed period of time, subsequent regulatory regimes (NRAU 2006 e NRAU 2012) would make the distinction between contracts approved before 1990 (controlled rents) and those signed later (free rents).

Table 2.

Main tenancy regimes in Portugal.

Both the 2006 and 2012 NRAU set the general goal of updating rents in pre-1990 contracts, and defined safeguard clauses for so-called ‘socially vulnerable groups’ to avoid social disruption. However, because they were formulated in quite different economic and ideological contexts, the former under a socialist government (before the 2008 crisis), and the latter during an economic crisis under a centre-right government, they seem to have led to different results in terms of the regulation of rent increases and tenant security.

The key goal of the 2006 NRAU (Lei n. 6/2006) was to enable the updating of old rents, but to make this conditional on the valuation of the property, which had to meet minimum standards (an indoor toilet, bathroom, the quality of the dwelling/building, etc.). The update of rents was conditional to the evaluation of the conservation coefficient of the property equal or greater than 3 (in a scale of 1 for terrible and 5 for excellent). To attain this valuation, the landlord had to arrange for a technical team of architects/engineers from the municipality to assess the property’s condition. If this was not satisfactory, the landlord would have to pay for maintenance works, and only afterwards could ask for a tax assessment of the property and, based on that, increase the rent. Only then could tenants with few financial resources apply for a housing allowance. Thus, in short, the process of updating rents and providing access to housing allowances depended on the condition of the property and on the capacity of landlords, who for many decades received very low rents, to invest in conservation works.

Regarding the 2012 NRAU regime (Lei n. 31/2012), it is important to understand the economic and political context in which it was created, and its main objectives. Therefore, it is worth to begin by mentioning that, as happened in other countries, the global financial crisis of 2007–2008 had considerable impacts in Portugal, resulting in higher interest rates, the stagnation of civil construction, and an increase in unemployment rates. As a consequence, many loans could no longer be paid back and mortgages were foreclosed, and the financial system became more reticent in providing mortgage loans to finance home purchases. In 2011, the prospective insolvency of Portugal led the socialist Portuguese Government under then-Prime Minister José Sócrates to ask for international support. The consortium of the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund (which became known as the Troika) responded with a 78-billion-euro bailout programme (known as “The Economic Adjustment Programme for Portugal”) that required a three-year programme of austerity measures. The “Memorandum of Understanding on specific economic policy conditionality”, signed by the socialist government and the “troika” team of lenders, defined the conditions that would be implemented by a centre-right government. The Memorandum acknowledged the problem of household indebtedness related to the purchase of housing, and how it negatively affected the Portuguese economy. It emphasized the advantages of a dynamic rental and property renovation/rehabilitation market that would respond to the needs of a more mobile population and flexible labour market.

The government agreed to undertake a review of the urban tenancy regime according to the following general guidelines:

- -

- To broaden the conditions under which renegotiation of open-ended residential leases could take place, limiting the possibility of transferring the contract to first-degree relatives;

- -

- To introduce a framework to make it easier for the landlord to give notice of updating the rent in the case of open-ended contracts, as long as the tenant had not reached the age of 65, and did not have more than 60% incapacity/disability;

- -

- To phase out rent control mechanisms, but protect socially vulnerable tenants;

- -

- To reduce the period of notice for termination of leases for landlords;

- -

- To establish an extrajudicial eviction procedure for breach of contract, aimed at shortening the eviction time to three months; the so-called “special eviction procedure” (processo especial de despejo) that would make the eviction procedure faster.

- -

- There was also a concern to promote the valuation of old properties in order to bring their property tax value—which is set by the fiscal authorities—closer to their real market value, and to end benefits for the purchase of properties (existing tax exemptions and deductions).

The 2012 NRAU regime also made it possible for landlords to ask for a lease to be terminated in order to undertake major renovation works (i.e., those that affect the building’s structure and stability) with a maximum of 6 months’ prior notice. The law stipulated that, except where tenants were elderly or had disabilities, when the building needed structural renovation, the eviction could take place provided that compensation was paid. If tenants were seniors or people with severe disabilities, they would have to be rehoused.

5. The Cumulative Impacts of Decades of Rent Regulation on the Private Rental Sector

In this section, we present the main results of the analysis of the 2011 Census data related to population and housing at the national, municipal and parish level.

5.1. Portugal and Lisbon

The rental sector in Portugal—comprising the private, public and subletting segments—has been in decline for several decades due to the combination of incentives towards homeownership—such as subsidized loans and tax exemptions—and the lack of incentives for the social, non-profit and PRS [35,36,37]. In 1991, 27.5% of the residential housing stock was rented, a percentage that has fallen consistently, first to 20.8% in 2001, and then to 19.9% in 2011.

According to the 2011 Census data, see Table 3, this 19.9% (794,465 dwellings) is distributed as follows. The private sector is by far the largest segment and within this, the majority, 57.9%, of the housing stock (459,683 dwellings) is let through open-ended contracts. It worth recalling that, with very few exceptions, these open-ended contracts were signed prior to 1990. Fixed-term contracts, on the other hand, account for 31.6% (250,840 dwellings) of the rental stock. Then, a much lower proportion, 8.6% (68,360 dwellings), are accounted for by social rents or equivalent1. Finally, there are 15,582 cases of subletting (2%).

Table 3.

Rented dwellings by type of contract (n.° and %), Portugal, Lisbon and Santa Maria Maior, 2011. Source: Own elaboration, with 2011 Census data.

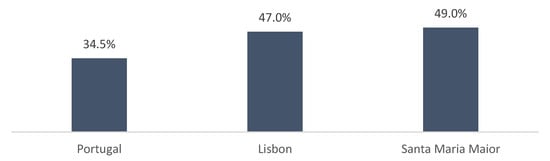

Lisbon’s rental sector comprises 100,241 dwellings. Experiencing a similar trend of decline, it shrank from 60% of the housing stock in 1991 to 48.6% in 2001, and to 42.3% in 2011. Therefore, although there is a long-term trend of decline both at the national level and at the municipal level in Lisbon, an important difference between these two scales remains: in Lisbon the rental sector still accounts for a high proportion of housing. As at the national level, in Lisbon most of the contracts in the private sector are also open-ended (55.5%, 55,643 dwellings) followed by fixed-term contracts (28.4%, 28,505 dwellings). The social housing sector in Lisbon is larger than at the national level (14.7% of the rental sector, 14,765 dwellings), and subletting accounts for 1.3% of the rental sector (1328 dwellings). Unsurprisingly, the proportion of contracts signed before 1990 is particularly high: 47% (46,523 dwellings) of the rental sector, excluding subletting (98,913 dwellings).

5.2. The Parish of Santa Maria Maior

According to the 2011 Census, SMM has 12,961 residents and 6426 households. Located in the heart of Lisbon’s downtown (Figure 1) and well served by public transportation, with its picturesque neighbourhoods, SMM attracts a large number of tourists and related economic activities. When compared with the average prices in the city centre, in some streets of SMM housing prices are extremely high, close to 6000 euros per square meter. The supply of new housing is aimed at medium-high and high-income households, including foreigners who benefit from diversified tax incentives for investments in housing.

Figure 1.

Location of the parish of Santa Maria Maior, municipality of Lisbon.

This same area also concentrates an important stock of rental housing, much of it protected by the rent regulation regimes, with low rent values and problems due to dereliction. The socio-demographic and economic portrait of its population warns of diverse vulnerabilities: an elderly population, a high proportion of single-person households, low educational levels, a high proportion of labour immigrants, and high levels of unemployment and economic inactivity [38].

The residential housing stock in SMM comprises 10,787 dwellings (Box 1).

Box 1. Residential housing stock key-facts, Santa Maria Maior, 2011. Source: Own elaboration, with 2011 Census data.

Residential housing stock: 10,787 dwellings

Dwellings used as main residence: 5993 (55.6%)

Ownership: 1436 (24.0%)

Tenancy 4302 (71.8%)

Tenancy, fixed-term contract: 1482 (24.7% within the total; 34.4% within the rental sector)

Tenancy, open-ended contract: 2680 (44.7% within the total; 62.3% within the rental sector)

Tenancy, social rent or equivalent: 76 (1.3% within the total, 1.8% within the rental sector)

Subletting: 64 (1.1% within the total; 1.5% within the rental sector)

Other: 255 (4.3%)

Dwellings used as secondary residence: 1296 (12%)

Vacant dwellings: 3498 (32.4%)

To sale: 195 (5.6%)

To rent: 937 (26.8%)

To demolish: 151 (4.3%)

Other: 2215 (63.3%)

Just over half (5993; 55.6%) are occupied as a main residence. This is partly due, on the one hand, to the proportion of secondary residences, i.e., dwellings occupied only occasionally (1296; 12%). On the other hand, in SMM in 2011 there was an extremely high proportion of vacant dwellings (3.498; 32.4%), of which only a small part was for rent (26.8%; 937 dwellings). A high number of vacant dwellings in SMM was already noticeable in the 2001 Census (30.7%) and this stands out clearly from the picture observed in the municipality of Lisbon and at the national level (15.6% and 12.5% in 2011, respectively). At the same time as the historic centre’s population is decreasing, vacant dwellings are increasing, suggesting that the housing market is unable or unwilling to attract permanent residents.

Of the dwellings used as a main residence, in SMM the majority are in the rental sector (71.8%; 4302 dwellings). This distribution of housing tenure type is very different from that seen at the national level, and also, to some extent, in Lisbon as a whole.

Although the 2011 Census data have shortcomings2, they allows us to briefly paint a picture of the rental sector that delineates: the types of contracts in use, the socio-economic status of tenants, rent prices and the material condition of buildings according to their owners.

Among all types of rental contract, open-ended ones are most prevalent (62.3%; 2680 dwellings). Fixed-term contracts account for 34.4% (1428 dwellings). Both social rents or equivalent and cases of subletting are residual, at 1.8% (76 dwellings) and 1.5% (64 dwellings), respectively. Even more compellingly, and in direct answer to the first questions posed by this study: almost half of these contracts (the cases of subletting excluded), date back to before 1990 (49%; 2076 dwellings).

The socio-economic group of the tenant responsible for the accommodation can be used, to some extent, as a proxy for the household’s economic status3. Table 4 systematises a social portrait of these tenants, who are mostly retired and other inactive people (2181; 50.7%); professionals and intermediate technicians working in commerce and services (896; 20.8%); and intellectual and scientific professionals (408; 9.5%).

Table 4.

Rented dwellings used as a main residence, by socio-economic group of the person responsible for the tenancy (n.° and %), Santa Maria Maior, 2011. Source: Own elaboration, with 2011 Census data.

The high proportion of economically inactive tenants is explained by an ageing population and the rent regulation policies that have given them protection against rental contract updates. The significant proportion of professionals and intermediate technicians working in commerce and services is accounted for by the economic function of the historic city centre, which for a long time, as Central Business District, has been linked to trade and services and, more recently, also to tourism. The presence of intellectual and scientific professionals is partly due to a process of social recomposition of the resident population—similar to that seen in other parishes in Lisbon’s historic centre—which since the 1990s has been experiencing some gentrification and the arrival of new residents from higher socio-economic groups, as they replace former residents, who tend to be older and from lower socio-economic groups.

Having looked at the significance of pre-1990 rental contracts in terms of households and dwellings, it is important to understand the impact of rent regulation on prices and housing quality. The distribution of prices by rent bracket allows us to understand the impact of decades of rent regulation on prices (Table 5). In SMM, in 2011, 32% of rents were below 75 euros per month. This figure contrasts with much higher values in the same area, most likely associated with fixed-term contracts. A total of 20.7% of contracts are in the highest rent brackets, above 400 euros. It is as if two rental sectors coexisted in the same area due to the rules according to which each sub-sector is run. To some extent, this distribution already anticipated the possibility of a price escalation as soon as the regulatory brake loosened.

Table 5.

Rented dwellings used as a main residence, by the rent bracket in nominal prices (n.°, % and cumulative percentage), Santa Maria Maior, 2011. Source: Own elaboration, with 2011 Census data.

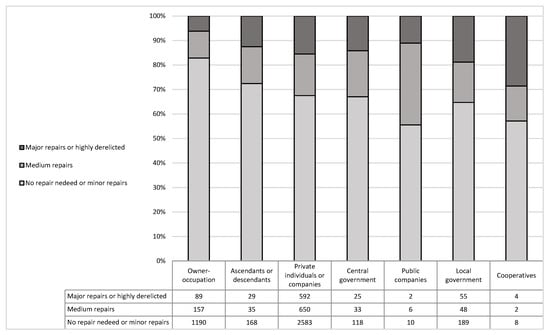

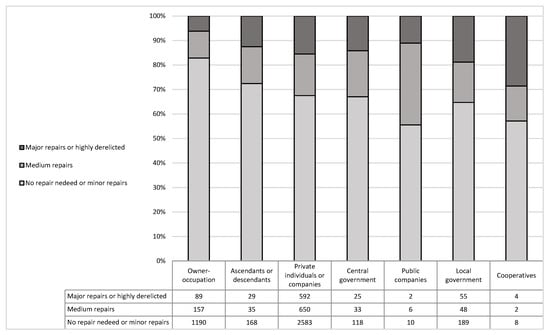

The rent regulation system has also had an important impact in housing quality. In SMM, of the 5993 dwellings occupied as a main residence, 71.2% (4266 dwellings) were in good condition or in need of minor repairs only. A small proportion, 13.3% (796 dwellings), needed major repairs or were highly derelict. Homes owned by their occupants—or by their occupants’ immediate family members—tended to be in better material condition. In private rented dwellings the need for repairs is higher, matching, to some extent, both the claims of tenants about landlords not carrying out maintenance works on the buildings, and of landlords, who say they cannot afford maintenance works while rents are kept at such low levels. Finally, the large number of public buildings in need of significant repairs is striking, showing the state’s failure in managing its public housing stock (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Dwellings by the building’s material condition, according to the owner (n.°), Santa Maria Maior, 20114. Source: Own elaboration, with 2011 Census data.

Finally, the 2011 Census allows us to quantify the tenants with contracts prior to 1990 who were aged 65 and over. In Portugal, they accounted for 20.9% of all contracts (163,061 out of the 778,883 dwellings), approximately half of which (49.8%) in 2011 had rents below 50 euros/month. At the local level, in the parish of SMM the proportion of tenants aged 65 and over on old (pre-1990) contracts was even higher, equivalent to 32.3% (1369 of 4238 dwellings). In addition, almost half (49.1%) with rents below 50 euros/month.

In sum, analysis of the PRS in SMM, Lisbon and Portugal—one year before the NRAU 2012 came into force—shows that the number of pre-1990 contracts was very significant (Figure 3). Against this backdrop, we can hardly classify the Portuguese PRS as a free rental market, as suggested by Kettunen and Ruonavaara [16]. In the next section we will show, using qualitative data, that even though theoretically the NRAU 2012 opened up the opportunity to liberalize the sector, this was not fully implemented.

Figure 3.

Dwellings in the rental sector with contracts prior to 1990 (%), Portugal, Lisbon and Santa Maria Maior, 2011. Source: Own elaboration, with 2011 Census data.

6. The Reforms of NRAU 2006 and 2012 in the Private Rental Sector

This section discusses the impacts of the 2006 and 2012 reforms upon tenants/landlords relations, the overall functioning of the PRS, and urban regeneration processes in inner-city Lisbon, and whether or they focused on social sustainability.

6.1. NRAU 2006

As mentioned earlier, the main goal of the New Urban Lease Regime (Novo Regime de Arrendamento Urbano, hereafter NRAU) of 2006 was to create conditions for the gradual updating of old low rents, which for decades had been subject to strict regulation. One other purpose of this reform was to promote the rehabilitation of derelict rented dwellings, as the updating of the rents was conditional on the evaluation of the state of conservation of the building or dwelling. Among interviewees there was a consensus, that the 2006 reform failed to achieve these goals. Respondents were asked to identify the main reasons that led to the failure of these reforms.

“The increase in rent was dependent on significant work being done in the property, that’s why many landlords did not initiate the process (of rent increases)”.(LAT2)

“The problem of NRAU 2006 was the material condition of buildings! (…) also the whole process was very bureaucratic and complex, that’s why most owners did not take part in the NRAU 2006”.(NA)

“One of the problems we have had, and still have, has to do with the value of rents, because we still have low rents, and houses need a lot of work! Even in situations where it has been possible to increase the rents, according to an updated property tax assessment, the rent turned out to be low vis-à-vis the amount of work needed”.(LAT2)

Accordingly to interviewees, there are three fundamental reasons that help to understand the low implementation of the 2006 NRAU and the consequent preservation of rents at low levels in old contracts: (i) rent increases were associated with the state of conservation of the building; (ii) low number of landlords that requested the technical inspection of buildings and (iii) low number of subsidies paid by the Social Security system.

The rent increase was conditional on the evaluation of the conservation coefficient of the property, as already mentioned, but the evaluation would entail an immediate increase in property tax5 and thus in tax payable by landlords. However, depending on the age and degree of disability of the tenants, rent increases could take up to 10 years to implement. Additionally, rent increases was limited to a maximum value of 4% of the tax equity value of the property, which according to Melo [39] corresponded broadly to about 1/3 of the market values.

As a result, landlords of buildings in an advanced state of degradation did not require the transition of contracts for the NRAU 2006, because that would require large investments in rehabilitation works and these were either decapitalized due to decades of freezing of rent, or not motivated to invest in refurbishment/maintenance of their dwellings and to rehouse their tenants during the period of works) for a low return of their investments.

In Lisbon, in 2008, only 4217 requests for inspections had been received and the monthly average of inspections was between 120 to 150 [40]. According to the municipality, after two years after the regime came into force, only 75 landlords had requested updating of rent values in Lisbon.

The low number of subsidies paid by the Social Security system at the national level confirms the interviews claim of a very low level of implementation of NRAU 2006. The legislation determined that in the case of tenants with economic vulnerabilities, the state should provide a housing allowance. Between 2012 and 2015 the number of subsidies increased from 2881 (in 2012) to 4111 (in 2013), as well as the annual spending on housing allowances increased during that period, from 140,000 thousand euros in 2012 to 500,000 thousand euros in 2015. All in all, a very low number of subsidies and spending, when we consider that the estimated number of contracts signed before 1990 and with very low rents was about 390 thousand [39].

One jurist recalled that the delay and the lack of response from the State vis-à-vis the request for housing allowances by tenants had the effect of stopping the process of rent increases, because many applications went unanswered by social security departments.

“During the NRAU 2006 there was a form that tenants could use to apply for a rent subsidy (housing allowance). And I had many cases that did not get any answer (not even an evaluation) … Many, many cases! […] When we realised that the Social Security services were not responding to rent subsidy applications, we started making subsidy applications for everyone, because we knew that the process (of updating rents) would end there”.(LAT2)

Due to the lack of implementation of the 2006 NRAU, a high proportion of tenants remained with low rents and low housing conditions. Additionally, the interviewees reported that the 2006 reform did not solve the issues in the judicial system, namely the delays in the evictions in the case of tenants who did not pay rent and the condemnation of landlords who did not carry out the works. In practice, this meant the continuation of poor housing conditions for tenants, who were nonetheless able to keep low rents.

6.2. NRAU 2012

The NRAU 2012 sought to address the 2006 scheme’s failure to alter pre-1990 contracts—namely by updating their rent values and changing their type/duration (from open- to fixed-term). It also aimed to speed up the eviction procedure in a wider range of cases.

With the exception of protected groups (see below), the law also made it possible for the landlord to terminate the contract when he/she needed the accommodation for him/herself or his/her descendants. The landlord could also ask for termination of the contract in order to carry out structural works or in case of demolition. Protected groups had either to be re-housed by the landlord in the same municipality or to receive compensation.

The law defined the so-called socially protected groups on the basis of age (65 or older), degree of disability (over 60%) economic deprivation (when annual household income was below five national minimum wages).

Age and disability could only be invoked to maintain contracts’ type/duration—that is, as open-ended—preventing their transition to a fixed-term contract. The law stipulates that older tenants or people with more than 60% disability can retain an open-ended contract. Otherwise, contracts are for 5 years.

Economic deprivation was the key criterion for limiting rent increases. The NRAU 2012 determined that the update should take place: (i) in the case of families without economic need, through a free negotiation process between the landlord and the tenant; (ii) but, in the case of families with economic need (defined as salaries below five minimum wages), increases were limited, and these families were entitled to a transitional period. During that period the maximum rent would be defined according to their wages, as follows: 10% of household income if this income did not exceed 500 euros per month; 17% if the value of the income was between 501 and 1500 euros; and 25% if the income was between 1501 and 2425 euros. Economically deprived tenants were protected for the first five years. After the transitional period, rents would be updated up to 6.6% of the property value of the dwelling.

Thus, lessees who demonstrated economic deprivation could benefit from protection against a large increase in rents during the transitional period. Only at the end of this period the rent could be updated (up to 6.6% of the property value of the dwelling), and tenants could apply for a rent subsidy from social security.

“Rare are the cases of people with pre-1990 contracts who were not protected by the NRAU 2012, as most of them had a socially protected status related to economic deprivation, age or disability. Major changes happened when landlords started applying to carry out structural restoration works in the dwelling, leading to a wave of evictions”.(LAT2)

Besides condemnation of the strategy of carrying out major work, which has led to the expulsion of vulnerable populations, one of the biggest criticisms of the NRAU in 2012 took aim at the short time tenants had to respond to landlords’ proposals: only 30 days after receiving them. Tenants’ associations and lawyers have stated that the population has been caught off guard, and that the deadline of 1 month was too short for these vulnerable groups (with low levels of education and economic resources). It should be noted that failure to respond within that period meant that tenants, even without knowing it, were automatically accepting their landlords’ proposals to increase the rent and make the transition to a new 5-year contract.

The interviewees reported that evictions, due to the regime of deep remodelling and restoration works, mainly occurred in large urban centres, where there was an interest in affecting the buildings to short term rentals, as in the case of SMM.

The president of the parish (Junta de Freguesia) said that in the historical centre of Lisbon, and particularly in SMM the “impact was terrible”:

“We ran the risk of this parish losing its characteristics, the characteristics of the people. We had to hire lawyers to help people. Tenants received the letter of termination of contract, or the announcement that their contract was for a fixed term, or they were going to do works and had to leave, or their rents went from two hundred to a thousand euros. […] dozens of people received letters that said their contract was now for a fixed term and their rent had changed. If they did not reply within a month, by law they had accepted the conditions. That was terrible and unfair, because these people have little literacy due to their age, many keep their letters waiting for their children to arrive to open them”.(LA1)

It is important to note that after a wave of evictions, the impacts of NRAU 2012 were mitigated after the election of a left-wing coalition that and passed a set of new protective laws in parliament.

In 2017, nearing the end of the transitional five-year period of for updating old rents, when a new wave of evictions was anticipated, the government established an eight-year extension (three years more than the initial five years). The transitional period for updating rents was thus extended until 2020. In practice this meant that instead of the state starting to pay housing allowances to tenants with proven economic deprivation, landlords would continue to be responsible for guaranteeing these families’ right to housing without any state compensation.

Law n. 30/2018 also created an extraordinary and transitory regime for the protection of elderly or disabled tenants who have been living in the same property for more than 15 years. It introduced the temporary suspension of landlords’ ability to refuse to renovate the property and terminate the contract, and the suspension of special eviction and eviction proceedings.

For some interviewees, the extension of the transitional period has delayed the necessary reform of the sector—that is, the updating of rents and the allocation of rent subsidies. Landlords have been forced to keep housing at derisory prices without compensation from the state. This has resulted in a lack of confidence among landlords and homeowners in the state, which has been an obstacle to the sector’s necessary modernization and to attracting more landlords to the PRS:

“What you cannot do is launch a reform and, when you need public investment to implement it, make a change to the law and postpone implementation. And that neglects the landlord, who cannot trust the rental sector”.(LAT2)

“I sympathise with the owners’ views: it is not up to them to make social policy”.(LA)

Another aspect highlighted by the interviewees is that the regulatory framework of NRAU 2012, unlike the previous NRAU 2006, does not limit the update of rent to the state of conservation of the building. However, the negotiation of the new rents is not completely unrestricted, because: (i) in the case of families with economic needs, the rent value is indexed to the household’s Gross Annual Corrected Income (RABC); and (ii) in the other cases, the rent increase has always a maximum value, which is 6.6% of the property value of the dwelling.

The interviewees also mentioned that the special eviction process has done little to improve the existing model. This is because some regulations foreseen in the current legislation have not, inexplicably, been approved. An example is the case of article 13-B of the NRAU, which foresees the possibility of injunctions, as well as the application of financial penalties, but in practice cannot be applied due to lack of regulation.

7. Discussion

Guided by two overarching goals—(i) to deepen understanding of the Portuguese rent regulation system, and (ii) to investigate the effects of the rent regulation regimes implemented during recent decades on social sustainability-focused urban regeneration in inner-city Lisbon—this paper answers three research questions. In this section, we try to bridge the gap between the theoretical framework applied to rent regulation and our case study.

When it comes to the first two research questions—which focus on the relative significance of regulated contracts in the private rented sector and, thus, whether the Portuguese rent regime may be classified as a free market system—our results show that open-ended contracts, the standard type of contract before 1990, still account for a significant part of the private rented sector (more than half of the sector at the national level and in Lisbon, and almost two-thirds of the sector at the parish level). Furthermore, many of these tenants belong to vulnerable protected groups, as defined in the recent reforms. Thus, Kettunen and Ruonavaara’s [16] classification of Portugal’s rent regulation regime as a free market system fails to capture the PRS’s most significant features. However, it is important to emphasize that Kettunen and Ruonavaara’s classification does accurately capture the most significant recent trend in Portugal: there has been weak public investment in the private rented sector (in terms of rent subsidies and capital grants for refurbishment), and thus it is correct to classify the approach to the PRS as neoliberal, in the sense that the Portuguese government is not implementing a comprehensive policy able to adequately protect vulnerable families against poor housing conditions and evictions. Moreover, Kettunen and Ruonavaara’s use of the ideal types approach to build theory and guide the formulation of their research hypothesis (see [41]), makes a significant contribution to the field of housing studies, and potentially to the wider field of the social sciences. By looking at differences/similarities in approaches to rent regulation between countries they make us think about how and why things are as they are. In addition, about how the patterns they identify—of rent levels and security of tenure—impact on both the wider structuration of housing markets, and on aspects of social sustainability. In Portugal, as initial rents in new contracts can in principle be set freely, rent regulation has mostly focused on regulation of properties that are already in the regulated sector, and therefore relates to an older population.

When it comes to the third research question—about the influence of the 2006 and 2012 reforms both on the trajectory of the PRS, and on aspects of social sustainability—several inferences can be drawn about the relationship between rent regulation and urban regeneration processes:

- -

- Rent regulations that affect contract duration, security of tenure and rent values have an unequivocal effect on processes of urban decline and/or regeneration;

- -

- Government subsidies and tax benefits (conditional on meeting certain standards) can provide incentives for landlords to raise quality in a way that cannot readily be enforced simply through regulation;

- -

- A combination of high demand at the controlled, low, rent level—which is associated with strict rent regulations and the lack of economic incentives for landlords—can seriously hamper the efficiency of the rental market by reducing buildings’ maintenance and tenancy mobility (as occurred with first-generation rent controls, which have benefited tenants at the expense of landlords);

- -

- Second-generation rent controls—based on longer-term tenancies with stable conditions that benefit both landlords and tenants, thus providing a more secure investment for landlords and investors and offering greater security and better-quality housing to tenants (for more details see Whitehead and Williams [10]—have hardly been implemented in Portugal;

- -

- By contrast, in Portugal, the implementation of bad regulation—even if it has been well-intentioned and might have provided short-term benefits—and/or the lack of implementation of good regulation, has resulted in disincentives to supply rented accommodation, with potential tenants being excluded from the sector, evictions and ultimately worse conditions for everyone.

Whitehead et al. [9] demonstrate that deregulation generally does not lead to growth in the private rented sector; in most countries, with few exceptions, it has been associated with continued decline in private renting. In fact, as they emphasize, countries that still have large PRSs are generally quite highly regulated, but with sophisticated regulatory frameworks that provide considerable certainty for both landlords and tenants.

This discussion inevitably leads us to a critical evaluation of the impact of the 2006 and 2012 rent regimes on the social sustainability of communities in Lisbon’s historic centre. The impacts of changes in rent regimes are, however, both complex and contradictory. Whilst the 2012 NRAU regime made it possible for landlords to ask for a lease to be terminated in order to undertake major renovation works when their building needed structural renovation, the legislation that followed, under a centre-left government, strengthened the protection mechanisms for vulnerable groups. However, this provided these groups with no more than partial protection. The postponement of the transition to NRAU for tenants with socio-economic vulnerabilities ensures that rent values are not updated to match the market level, and that the state does not have to pay housing allowances, but it fails to improve tenants’ housing conditions and the attractiveness of the PRS. Nor is it a preventive measure against new evictions, especially if tenants are younger than 65 and have not lived in their home for at least 15 years. The result is to be expected: landlords with low-income tenants do not make improvements to the rented dwellings because tenants pay very low rents. The latter, precisely on account of their economic circumstances, cannot do so either, and often have to live in poor housing conditions. In the absence of income-related housing allowances—which the NRAU 2012 foresaw being implemented after the five years of transition—the retention of rent controls does not provide an adequate rental yield for landlords who, in turn, being undercapitalized, do not carry out maintenance or renovations in their properties and so the widespread mistrust in the rental sector prevails. In the long term, this trend leads to very low maintenance and poor conservation of buildings, producing poor conditions of habitability in the built environment, worsening quality of life and the social sustainability of neighbourhoods, and blocking the initiation of urban regeneration processes.

On the other hand, the liberalization of rent values brought about by the NRAU has significantly affected rent levels in new PRS contracts. These higher rent levels, associated with growing external demand (with much higher purchasing power) and fragile and scarce supply (due to a lack of confidence on the part of landlords in the rental market), reproduce a growing mismatch between supply and demand. This hugely increases the burden on many families, making the rental market unstable and socially polarized, and therefore incompatible with healthy levels of social sustainability in the urban regeneration that has taken place.

8. Conclusions

The control mechanisms that regulate rents can take many forms and can have several consequences in terms of the quality and availability of housing, and the social sustainability of processes of urban regeneration.

The so-called rent freeze widely used in the immediate post-war period in many European countries, was reintroduced in Portugal in the mid-1970s. More recently, in 2015, stringent rent controls were implemented in the segment of older, open-ended contracts which are linked with low rents and often poor housing conditions.

The Portuguese case study provides an example of the paradoxes of rent regulation. Although expected to translate into tenants’ protection and stabilization of rent prices over a given period, namely protecting tenants against displacement and evictions, and to contribute for the social sustainability of communities and territories, without the implementation of the state subsidy that could guarantee the suitable turnover of landlords, rent regulation in Portugal ended up contributing to a reduction in affordable housing to rent and compromising the quality of the stock.

As in other European countries where rent regulation failed to balance the landlords-tenants’ interests, in Portugal, strict rent controls intimidate owners and their perception and confidence in the market, who might search for alternative uses of their properties or even keep them vacant, as has happened in many cities. At the same time, this rudimentary form of rent regulation prevents investment for maintenance and conservation works on the buildings, resulting in a worsening of the housing conditions of tenants.

In the medium- and long run, rent regulation in Portugal weakened the PRS and deepened its polarization between open-ended contracts with very low rents, on the one hand, and fixed-term contracts with high rents and poor tenure security, undermining the possibilities for a prosperous and stable development at the local scale.

In the last decade, the supply of affordable private rental contracts decreased significantly as rent levels skyrocketed in most big cities, which is jeopardizing the right to housing at affordable prices in cities, the housing conditions of tenants and the social sustainability of communities and neighbourhoods.

The new generation of housing policies in Portugal, launched in 2018 is slowly increasing the public spending on social housing, and started to new subsidies and tax advantages to landlords with rent levels being fixed at a political stage (as in the case of affordable housing). This renewed understanding of housing policies and households needs for housing in Portugal is currently promoting a different form of rent control that is dependent on supply-side subsidies and active land policies. The results are yet to be known. In the case of the old open-ended contracts, the government has introduced provisions that have increased the tenure security of tenants but has not yet invested funds and resources in rehabilitation, and a must needed economic equilibrium between tenants and landlords is still to be reached. National tenancy regulation continues to disregard important aspects of the overall functioning of the PRS as the adequate profitability of landlords and acceptable housing conditions for tenants. Therefore, rent regulation is being used, again, as a relatively cheap mechanism for ensuring the right to housing and affordability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A., A.B.A. and L.M.; Methodology, S.A., A.B.A. and L.M.; Investigation, S.A.; Writing—original draft, S.A., A.B.A., L.M. and K.S.; Writing—review & editing, S.A. and L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has received funding from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Sónia Alves under the Norma Transitória [DL 57/2016/CP1441/CT0017 (Sónia Alves); Alda Botelho Azevedo in project Population and housing needs in Portugal, 2021–2050, Grant number: 2020.01758.CEECIND/CP1615/CT0010. Sónia Alves and Alda Botelho Azevedo acknowledge financial support from the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA) research and innovation programme of the European Union’s Horizon Europe, under the grant agreement ID 101086488: Delivering sAfe and Social housing (DASH). Luís Mendes acknowledges financial support from FCT–Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the project “Care(4)Housing–A care through design approach to address housing precarity in Portugal” (PTDC/ART-DAQ/0181/2021).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | According to the 2011 Census, the social housing sector in Portugal at that point made up a very small part of the residential housing stock (1.7%, 68,360 dwellings). In 2011, Lisbon was the municipality with the largest social housing stock (6.2%, 14,765 dwellings). |

| 2 | Most variables refer to the rental sector as a whole, i.e., including social housing and subletting. Given the low proportion of social housing and sublets in SMM (140 dwellings; 3.3% of the rental sector), we believe that an accurate picture of the PRS will not be very different from that of the rental sector as a whole. In any case, when we refer to the data we clarify to which they pertain: the rental sector as a whole, or just the PRS. |

| 3 | In this paper we use an adapted taxonomy of 27 socio-economic groups constructed by the National Statistics Office. The original groups were formed using the following three primary variables: profession, situation in the profession, and number of workers in the company in which an individual works. In order to ensure coverage of the entire population, those who are inactive are included in a separate group. |

| 4 | Note: This chart is based on data that does not distinguish dwellings in the rental sector (4302) from those accounted for by other types of tenure (255 dwellings). |

| 5 | The equity value of the property was calculated based on the conservation state of the property and other indicators such as location, age of the building, and average construction costs. |

References

- Jonkman, A.; Janssen-Jansen, L.; Schilder, F. Rent increase strategies and distributive justice: The socio-spatial effects of rent control policy in Amsterdam. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2018, 33, 653–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priemus, H. Rent Policies for Social Housing. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home; Smith, S.J., Elsinga, M., Fox O’Mahony, L., Seow Eng, O., Wachter, S., Wood, G., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kholodilin, K. Long-Term, Multicountry Perspective on Rental Market Regulations. Hous. Policy Debate 2020, 30, 994–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, P. Access and affordability: Housing allowances. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home; Smith, S.J., Elsinga, M., Fox O’Mahony, L., Seow Eng, O., Wachter, S., Wood, G., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Haffner, M.; Elsinga, M.; Hoekstra, J. Access and Affordability: Rent Regulation. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística. O Parque Habitacional e a sua Reabilitação-Análise e Evolução 2001–2011; Instituto Nacional de Estatística: Lisboa, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Garha, N.S.; Azevedo, A.B. Population and Housing (Mis)match in Lisbon, 1981–2018. A Challenge for an Aging Society. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, A. Rental housing: The international experience. Habitat International 2016, 54, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, C.M.; Scanlon, K.; Monk, S.; Tang, C.; Haffner, M.; Lunde, J.; Voigtlander, M. Understanding the Role of Private Renting: A Four Country Case Study; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, C.; Williams, P. Assessing the Evidence on Rent Control from an International Perspective; Housing Supply & Rents, Occasional Reports, Regulation & Enforcement Reports; LSE: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, L. Gentrificação e políticas de reabilitação urbana em Portugal: Uma análise crítica à luz da tese rent gap de Neil Smith. Cad. Metrópole 2014, 16, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S. Spaces of inequality: It’s not differentiation, it is inequality! A socio-spatial analysis of the City of Porto. Port. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 15, 409–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, P.M.; Azevedo, A.B.; Paci, C. População e Habitação No Centro de Lisboa, 1991–2011: Declínio e Envelhecimento? ICS Research Brief 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.ics.ulisboa.pt/flipping/ie2020/ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Tulumello, S.; Cotella, G.; Othengrafen, F. Spatial planning and territorial governance in Southern Europe between economic crisis and austerity policies. Int. Plan. Stud. 2020, 25, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S. Divergence in planning for affordable housing: A comparative analysis of England and Portugal. Prog. Plan. 2022, 156, 100536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettunen, H.; Ruonavaara, H. Rent regulation in 21st century Europe. Comparative perspectives. Hous. Stud. 2021, 36, 1446–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.; Oxley, M. Using Incentives to Improve the Private Rented Sector: Three Costed Solutions; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon, K. Private Renting in Other Countries. In Towards a Sustainable Private Rented Sector; Scanlon, K., London, L.S.E., Eds.; London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, A.B.; López-Colás, J.; Módenes, J.A. Recent increase of tenancy in young Spanish couples: Sociodemographic factors and regional market dynamics. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2019, 34, 1043–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, P. Low-income tenants in the private rental market. Hous. Stud. 2011, 26, 1019–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S. Poles Apart? A Comparative Study of Housing Policies and Outcomes in Portugal and Denmark. Hous. Theory Soc. 2017, 37, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciantonio, C.D.; Aalbers, M.A. The Prehistories of Neoliberal Housing Policies in Italy and Spain and Their Reification in Times of Crisis. Hous. Policy Debate 2018, 28, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L. Tourism gentrification in Lisbon: The panacea of touristification as a scenario of a post-capitalist crisis. In Crisis, Austerity and Transformation: How Disciplinary Neoliberalism Is Changing Portugal; David, I., Ed.; Lexington: London, UK, 2018; pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lees, L.; Bang Shin, H.; López-Morales, E. (Eds.) Global Gentrifications: Uneven Development and Displacement; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Colantonio, A.; Dixon, T. Urban Regeneration and Social Sustainability: Best Practice from European Cities; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Glasson, J.; Wood, G. Urban regeneration and impact assessment for social sustainability. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2009, 27, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohon, J. Social inclusion in the sustainable neighborhood? Idealism of urban social sustainability theory complicated by realities of community planning practice. City Cult. Soc. 2018, 15, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcraft, S. Understanding and measuring social sustainability. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2015, 8, 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lind, H. Rent regulation: A conceptual and comparative analysis. Eur. J. Hous. Policy 2001, 1, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esping-Andersen, G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge and Princeton; Polity Press and Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bruun, H.H. Science, Values and Politics in Max Weber’s Methodology; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, S.; Burgess, G. Planning policies and affordable housing: A cross-comparative analysis of Portugal, England and Denmark. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Global Dynamics of Social Policy, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany, 25–26 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, P.; Aguiar-Conraria, L.; Barros, V.G.; Batista, P.; Brinca, P.; Castro, E.A.; Duarte, J.B.; Gonçalves, D.; Huget, R.; Lourenço, R.F.; et al. The Real Estate Market in Portugal: Prices, Rents, Tourism and Accessibility; Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos: Lisboa, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, L. The Dysfunctional Rental Market in Portugal: A Policy Review. Land 2022, 11, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgueiro, T.B. Lisboa, Periferia e Centralidades; Editora Celta: Oeiras, Portugal, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Antunes, G. Políticas de Habitação-200 Anos; Casal de Cambra, Caleidoscópio: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, A.B. Como Vivem os Portugueses—População e Famílias, Alojamentos e Habitação; Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos: Lisboa, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro, M.I.; Manata, L.; Costa, M. Diagnóstico Social Santa Maria Maior; Junta de Freguesia de Santa Maria Maior: Lisbon, Portugal, 2015; Available online: https://www.jf-santamariamaior.pt/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Diagnostico-Social-da-Freguesia-V1.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Melo, I.Q. O Mercado de Arrendamento: Principais Oportunidades e Fragilidades Face ao Mercado de Habitação Própria. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara Municipal de Lisboa. Relatório da Primeira Fase; Pelouro da Habitação e Desenvolvimento Local: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kemeny, J. Comparative housing and welfare: Theorising the relationship. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2001, 16, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).