Abstract

Promoting the transfer of rural residential land is paramount in enhancing the efficiency of its utilization. The willingness of farmers to transfer rural residential land is influenced by the number of permanent residents. Existing research has drawn different conclusions about the relationship between these two factors, but the differences have not been analyzed. This study is based on survey data collected from our field research in Deqing County, Zhejiang Province, and utilizes the Probit model and threshold effect model to investigate the role of per capita net income in the relationship between the number of permanent residents and the willingness to transfer rural residential land. The results indicate: (1) There is a non-linear impact of the number of permanent residents on the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in rural areas to transfer to their rural residential land with an income threshold. There is a non-linear impact of the number of permanent residents on the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in city areas to transfer out of their rural residential land, with two income thresholds. By comparing with the actual situation, the size and order of the thresholds are scientifically established. (2) The transfer of rural residential land can serve as a supplementary solution to individual household applications for rural residential land, addressing China’s historical legacy issues concerning rural residential land. Considering these findings, policymakers should first actively promote the reform of the rural residential land system while ensuring safeguards for farmers and then work to increase the value of rural residential land. Additionally, they should implement differentiated policies to promote rural residential land transfer. This study can provide a valuable reference for effectively revitalizing idle rural residential land.

1. Introduction

As one of the largest developing countries, China has a large rural population. Since China’s reform and opening-up in 1978, with the rapid progress of urbanization, the rural population in some areas has moved into the cities for employment and settlement, resulting in a declining trend in the rural population. At the same time, the area of rural residential land has continued to rise [1]. There was a 14 million hectare increase in rural residential land from 1995 to 2014, and of all rural residential land in China, it was estimated that at least 20% was idle [2]. In the past, the central government implemented a system of rural residential land that restricted the scope of the transfer of rural residential land in order to protect the residential rights of farmers and rural stability. This prevented social capital and urban residents from participating in the transfer of rural residential land, resulting in an imbalance between supply and demand in the rural residential land market. The prices of rural residential land do not accurately reflect their actual value, thereby impeding efficient allocation, ultimately solidifying the urban-rural dichotomy [3]. In response, a new tripartite entitlement system for rural residential land was recently proposed by the central government of China. Unlike farmland, the tripartite entitlement system for rural residential land is based on the system of “separation of two rights”, forming the “three rights” of “ownership right, qualification right and use right”. The objective of the tripartite entitlement system is to uphold the fundamental housing requirements of farmers while enhancing utilization efficiency through the transfer of rural residential land. The ultimate goal is to increase farmers’ income and promote the integrated development of urban and rural areas [4,5].

Urbanization is an inevitable trend in socioeconomic development. However, rapid urbanization can lead to rising unemployment, higher living costs, housing pressure, and degraded environmental quality [6]. These challenges are also driving suburbanization in developed nations [7]. In China’s urbanization process, valuable insights from developed countries have guided policymakers. As a result, China has implemented a policy that prohibits local governments from requiring farmers to give up their rural residential land when they move to urban areas. This ensures that if farmers encounter difficulties in urban living, such as higher living costs or housing pressure, they have the option to return to their rural areas. In practice, we discovered that the proportion of farmers returning to rural areas is quite low, despite their prolonged residency on the urban fringes. Consequently, numerous rural residential land remains idle, impeding the scale utilization of rural construction land. In essence, the current problems in China are a normal part of the urbanization process, such as the reduction of the rural population and the inefficient use of rural residential land, which have also occurred in the urbanization process in North America and developed European countries.

After World War II, the issue of low agricultural production efficiency became widespread in developed countries across Europe and America. Some Western European nations witnessed a gradual decline in public infrastructure within rural areas, resulting in reduced attractiveness for rural living [8,9]. Consequently, rural areas experienced a gradual decline, and in Central and Eastern European regions, a significant number of “dying villages” even emerged [10]. Some developed countries in Western Europe noticed a partial similarity between fallow farmland and idle residential land [11]. They began with land consolidation, aiming to integrate the land effectively. Subsequently, they applied the experience gained from this process to consolidate idle residential land. Practical results demonstrated that land consolidation improves rural land productivity and fosters sustainable development in rural areas [12,13]. On this basis, developed countries, led by European nations, have tackled the problem of low efficiency in using rural residential land by implementing measures like land consolidation [14,15]. Research shows that farmers as the main actors in the process of rural residential land consolidation, and their willingness to participate is closely related to their household structure, age and occupation [16,17,18].

Notably, the fundamental distinction between rural residential land in China and certain European and American countries lies in whether the land is privatized [19]. In these countries, farmers have the autonomy to freely manage and trade their land as a commodity, marking a significant contrast to the Chinese context. As a result, in addressing the matter of rural residential land in China, scholars have directed their attention toward key aspects, including property rights, consolidation and transfer of rural residential land, and the governance of hollowed villages [20,21,22,23,24,25]. Currently, international scholars have done rich and interesting research on the willingness of farmers to transfer their rural residential land. It is widely acknowledged that farmers’ willingness to transfer their rural residential land is influenced by diverse factors, including individual characteristics, family characteristics, and rural residential land characteristics [26,27,28,29,30]. Among these factors, individual characteristics primarily encompass age, education level, and whether they are members of the village collective. Household characteristics primarily encompass total household income, the number of permanent residents, the number of individuals in the labor force, and the proportion of non-agricultural income. Furthermore, rural residential land characteristics primarily include the area of the rural residential land, its distance from the county, and the number of rural residential land plots. At the psychological level of farmers, farmers’ welfare identities and risk expectations are also gradually receiving extensive attention from scholars [31,32].

The rapid development of China’s socioeconomic level has led to an irreversible trend of urban–rural transfer of rural farmers [33], resulting in a wide variation in the number of permanent residents in peasant households. In essence, the number of permanent residents determines the structure of the household and, therefore, the area of the rural residential land for each household member [34,35], influencing the willingness of farming households to transfer and even the extent and speed of expansion of the rural residential land [36]. Most existing studies consider the number of permanent residents as a control variable and provide a brief analysis of its impact on the willingness to transfer rural residential land. Based on the available research, it is evident that while there is general support for a linear correlation between the number of permanent residents and the willingness to transfer rural residential land [31,37,38,39], there is no consistent consensus regarding the direction of this interaction. Through our comprehensive analysis, we have found that farmers engage in a thorough evaluation of the advantages and risks involved in transferring their rural residential land [40].

Despite the potential “risk of rural residential land loss” associated with urban living, higher income levels enhance farmers’ capacity to withstand risks, augment their willingness to reside in urban areas and stimulate the transfer of their rural residential land [41]. Nevertheless, certain studies have also reached the conclusion that farmers residing in urban areas do not necessarily indicate their willingness to transfer their rural residential land. In the case of farmers with higher income levels, their rural residential land holds emotional significance as a symbol of their “hometown”, leading them to resist the transfer of their rural residential land [42].

Based on the aforementioned analysis, we have observed that the influence of the number of permanent residents on the willingness to transfer rural residential land may be contingent on the income levels of farmers. Furthermore, the existing studies, despite providing a solid foundation for this research, exhibit two limitations. Firstly, the majority of studies treat farmers as a homogeneous group, overlooking the fact that farmers’ preferences regarding their future residence can generate heterogeneous demand for rural residential land. This is an aspect that is less considered in current research. Secondly, existing studies rarely classify transfers into transfer in and transfer out. The crucial distinction between these two types is that the flow of funds is different, resulting in different analytical processes from a “cost–benefit” perspective and subsequently leading to disparate outcomes.

This study first categorizes farmers based on their willingness to live in urban areas. Therefore, this study first categorizes farmers based on their willingness to live in urban areas. It then reveals the income threshold at which the influence of the number of permanent residents on the willingness of farmers to transfer in or out of rural residential land changes in terms of intensity or direction. This study also provides targeted policy recommendations, which have theoretical value and practical significance in enriching research on the transfer of rural residential land and effectively promoting its transfer. Based on this, this paper establishes an analytical framework to examine the relationship between the number of permanent residents and the willingness of farmers to transfer in or out of rural residential land. This study utilizes farmer-level research data from Deqing County, Zhejiang Province, aiming to address the following questions: (1) Is there an income threshold at which the number of permanent residents influences the willingness of farmers to transfer in or out of rural residential land? (2) What are the disparities in income thresholds between farmers who prefer residing in rural areas and those who prefer urban areas in the future? This study aims to provide references for formulating specific measures for the transfer of residential land tailored to different types of farmers. Its ultimate objective is to provide guidance for effectively revitalizing idle rural residential land and implementing strategies for rural revitalization.

2. Theoretical Framework

The growing population of permanent residents presents a dual challenge for farmers. On the one hand, it necessitates increased financial investments to sustain their livelihoods, thereby demanding higher income levels. On the other hand, it can diminish their living comfort, prompting farmers to transfer rural residential land or acquire larger housing areas to enhance their quality of life. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory states that humans have five levels of needs, listed from bottom to top, which are physiological needs, safety and security needs, social and belongingness needs, esteem needs, and self-actualization needs [43]. Drawing on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory and relevant research, this article categorizes the demands of farmers for rural residential land into three aspects: survival and security needs, developmental needs, and emotional needs [44].

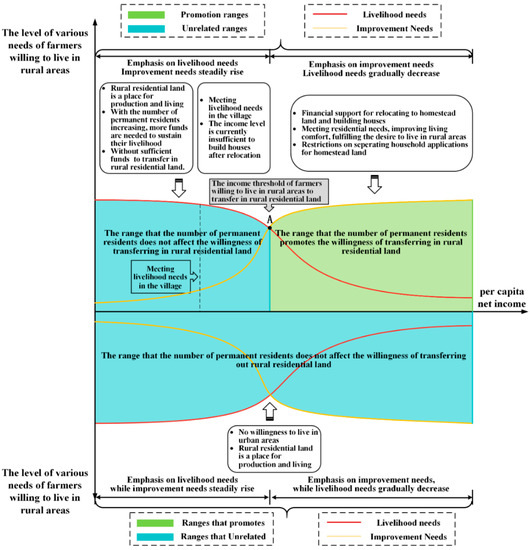

2.1. Willingness to Live in Rural Areas, the Number of Permanent Residents and Willingness to Transfer Rural Residential Land

When the household per capita net income of farmers who are willing to live in rural areas is still sufficient to meet their livelihood needs, their economic focus revolves around survival [45]. During this phase, farmers prioritize their survival and security needs, allocating their production factors toward sustaining their daily lives. Rural residential land serves as their primary location for production and living, and as the resident population grows [46], farmers are compelled to invest more funds to alleviate their livelihood pressures. However, they have limited additional funds available for transferring to rural residential land. Therefore, farmers will make changes to the elements and structure of their rural residential land, such as utilizing green spaces or courtyards to construct additional housing, in order to continuously meet their residential needs.

Once farmers’ per capita income surpasses the livelihood threshold, their economic mindset gradually shifts towards an improvement-oriented approach, developing a desire for advancement [35]. With a continuous increase in the number of permanent residents, the initial rural residential land endowment may no longer satisfy the living satisfaction of household members or meet their residential needs. In such cases, farmers generally opt to apply for additional rural residential land through separate household applications to enhance their quality of life [47]. However, in reality, there are situations where farmers are unable to apply for additional rural residential land. For instance, some villages have limited rural residential land quotas, and the acquisition of additional rural residential land may be restricted [48]. Additionally, farmers may either not meet the requirements for separate households or lack the financial means to construct and renovate houses, even if they qualify [49]. In these circumstances, farmers may choose to transfer to rural residential land. During the contract period for transferring rural residential land, the scarcity of additional rural residential land is likely to decrease as rural residential land system reforms progress. Moreover, farmers can transition from not meeting the requirements for separate households to meeting them (e.g., unmarried children getting married) or increase their family savings during this period. Transferring to rural residential land provides immediate relief from current residential pressures and fulfills their desire to continue living in rural areas. Consequently, in situations where the number of permanent residents is steadily increasing, farmers tend to opt for transferring to residential land. Generally, for farmers who are willing to live in rural areas, the rural residential land serves as their primary location for production and living, and they typically do not have the intention to transfer out [50]. It is also noteworthy that farmers who are willing to live in rural areas have an emotional attachment to their rural residential land, and this attachment becomes more apparent with increasing income. However, their emotional needs can still be satisfied on the existing rural residential land, thereby not influencing their willingness to transfer.

Based on the above analysis, this study presents the following hypotheses:

H1:

There is a non-linear impact of the number of permanent residents on the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in rural areas to transfer to their rural residential land. With an increase in the household per capita net income level, the relationship transitions from being unrelated to being promoted.

H2:

The number of permanent residents is unrelated to the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in rural areas to transfer out rural residential land.

Based on these hypotheses, a graphical representation illustrating the relationship between the number of permanent residents and the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in rural areas to transfer rural residential land can be depicted (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The relationship between the number of permanent residents under different income levels on the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in rural areas to transfer rural residential land.

2.2. Willingness to Live in City Areas, the Number of Permanent Residents and Willingness to Transfer Rural Residential Land

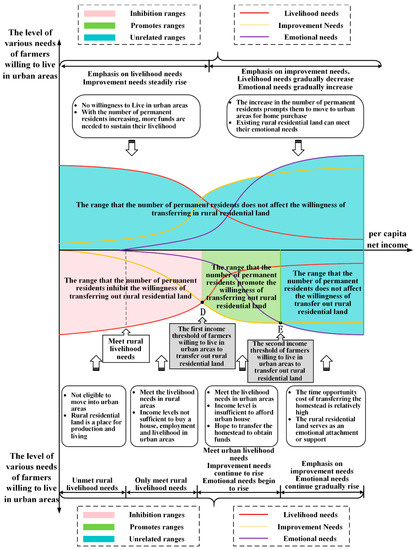

As mentioned earlier, when the household per capita net income level is low, an increasing number of permanent residents adds pressure on rural residential land to meet their livelihood needs. These farmers do not intend to move to urban areas and focus primarily on utilizing their rural residential land to meet their living requirements and achieve self-sufficiency [46]. Consequently, the number of permanent residents acts as a deterrent for farmers to transfer out of their rural residential land. However, as the income level increases, even though the household per capita net income of farmers willing to move to urban areas fully satisfies their livelihood needs in rural areas, the high cost associated with leaving the rural areas for urban living due to income disparities between urban and rural areas, becomes a significant barrier. Therefore, farmers consider transferring out their rural residential land and utilizing the rental income and potential appreciation gains to alleviate their financial pressure and solidify their urbanization achievements [51]. During this phase, there is a positive correlation between the number of permanent residents and the willingness of households to transfer out of their rural residential land, indicating a shift in their relationship.

However, it is important to note that this choice is not a consistent pattern for farmers. Transferring out the rural residential land incurs a certain time cost [41]. Once the household per capita net income level reaches a point where the potential income from alternative uses of that time exceeds the gains from transferring out rural residential land, farmers no longer consider transferring out. They gradually develop an emotional attachment to their rural residential land, considering it their “hometown” [27]. For farmers desiring to move to urban areas, they do not envision their future residence in rural areas. An increase in the number of permanent residents motivates them to acquire larger properties in urban areas rather than prompting them to transfer to rural residential land. Even if they plan to return to rural areas for retirement, their existing rural residential land can fulfill their emotional attachment.

Based on the above analysis, this study presents the following hypotheses:

H3:

With an increase in household per capita net income, there is a non-linear impact of the number of permanent residents on the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in city areas to transfer out of their rural residential land. The relationship transitions from inhibiting to promoting and ultimately becomes unrelated.

H4:

The number of permanent residents is unrelated to the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in city areas to transfer to rural residential land.

Based on these hypotheses, a graphical representation illustrating the relationship between the number of permanent residents and the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in city areas to transfer rural residential land can be depicted (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The relationship between the number of permanent residents under different income levels on the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in urban areas to transfer rural residential land.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Study Area

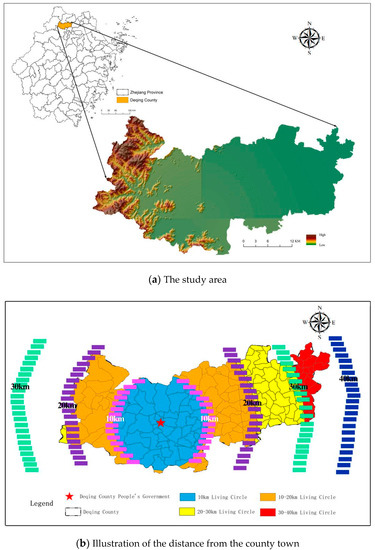

This article focuses on Deqing County, as shown in Figure 3a, located in Zhejiang Province, as the research area. Administratively, Deqing County falls under the jurisdiction of Huzhou City, Zhejiang Province. Situated in the northern part of Zhejiang, it shares borders with Shanghai to the east and is connected to Hangzhou in the south, making it a pivotal node within the Hangzhou metropolitan area. Since China’s reform and opening-up policy, Deqing County has actively participated in numerous national and provincial-level pilot projects aimed at various reforms, including optimizing government services, enhancing the business environment, and reforming the household registration system. These experiences have been replicated and promoted nationwide, resulting in tangible benefits for Deqing County. In 2021, Deqing County achieved a remarkable GDP growth rate of 8.7%, reaching 61.55 billion yuan. The county’s permanent resident population rose to 553,000, with a per capita disposable income of 57,837 yuan, representing a significant increase of 10.9% compared to the previous year. The strategic location of Deqing County in the Yangtze River Delta has led to a surge in its economy and an influx of population, leading to increased demand for land. In response, Deqing County proactively applied for a pilot project on rural land system reform, exploring a reasonable approach for “rural land marketization”. As of the on-site investigation, the “rural land marketization” project in Deqing County has seen 254 transactions, generating a revenue of 599 million yuan and benefiting the collective with an amount of 478 million yuan. This effort has contributed to resolving conflicts between people and land and facilitated increased income for farmers.

Figure 3.

The study area and the illustration of the distance from the county town.

In recent years, leveraging its abundant reform experience, Deqing County, as fertile ground for reform, has been consecutively selected as a pilot region for the first and second rounds of rural residential land system reform in China. During the first round of reforms, Deqing County issued the first batch of certificates for rural residential land, allowing farmers to transfer, lease, and mortgage their rural residential land. In the second round of reforms, Deqing County carried out comprehensive digital rural construction, integrating digitalization into the management of rural residential land and achieving full-process digital management and revitalization of residential land. Deqing County has relatively developed village industries, which have helped address the employment issues of local farmers. Rural residents can choose to work within the village or find employment in the county seat or other areas. As shown in Figure 3b, Deqing County spans approximately 60 kilometers from east to west, and the county seat’s central location within the entire county, contributes to a scenario where even those farmers employed in the county seat tend to return to their rural residential land solely during weekends, resulting in a certain difference in the number of permanent residents. Additionally, the village industries have also attracted migrant workers. Enterprises need to provide basic housing for these workers. However, Deqing County, located in the eastern part of China, has limited availability of rural residential land, and in most villages, it is difficult to meet the demand for rural residential land applications. Consequently, the phenomenon of rural residential land circulation is widespread. Therefore, selecting Deqing County as the research area for this study is feasible.

3.2. Data

In January 2022, our research team conducted a field survey in Deqing County to investigate the effectiveness of the rural residential land system reform. We selected administrative villages that showed relatively good progress in implementing the reform, covering a total of 105 villages across 13 towns (or townships). Using a random sampling method, approximately five households were randomly selected from each village for face-to-face interviews. The interview covers farmers’ personal and family characteristics, ownership of rural residential land, attributes of affiliated houses, and their willingness to transfer the rural residential land. Based on the interview content, investigators fill out questionnaires.

In the key variables, we addressed the following questions: “Are you willing to transfer your rural residential land?” “How many family members reside at home for more than six months a year?” “What is the size of your family?” and “What is your family’s approximate annual income?”. These questions aimed to understand farmers’ willingness to transfer rural residential land, the number of permanent residents, and the per capita net income. During the survey, we collected a total of 510 questionnaires. After reviewing and filtering out invalid responses, we obtained 504 valid questionnaires, resulting in an effective rate of 98.82%.

3.3. Variables

The variables selected for the study according to the research objectives are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variables and descriptive analysis.

- (1)

- Categorical variable: Farmers are classified into two categories based on their willingness to live in city areas. “Yes” indicates farmers who are willing to live in city areas, while “No” indicates farmers who prefer to live in rural areas. This variable is categorical and is not used in regression equations.

- (2)

- Dependent variable: When examining the influence of household per capita net income and the number of permanent residents on the intention to transfer rural residential land, the dependent variable is the intention to transfer in. A value of ”0” represents no intention to transfer, while a value of “1” represents the intention to transfer. When studying the impact of household per capita net income and the number of permanent residents on the intention to transfer out rural residential land, the dependent variable is the intention to transfer out. A value of 0 represents no intention to transfer out, while a value of 1 represents the intention to transfer out.

- (3)

- Independent variable: The independent variable is the number of permanent residents, defined as “the number of individuals who have resided in rural residential land for at least 6 months in a year,” which follows the commonly adopted definition in the academic community [36]. This variable is of a discrete type.

- (4)

- Threshold variable: Considering the differences in household consumption levels, this study adopts household per capita net income as the threshold variable, which is represented by the ratio of annual net income to household population.

- (5)

- Control variables: Drawing from relevant literature [27,46,51,52,53], control variables are selected from three aspects: individual characteristics of farmers, household characteristics, and village characteristics. Individual characteristics include variables such as gender, age, years of education, and health condition. Household characteristics include variables such as the number of labor force members, rural residential land area, main sources of income, the number of sources of income, the number of children, and the area of farmland. Village characteristics include variables such as village types, village area, the distance from the county town, and the development of non-agricultural industries.

3.4. Model

3.4.1. Binary Probit Model

Farmers face two options regarding the transfer of rural residential land: either being willing or unwilling to transfer in or out. This variable falls into the binary classification category. Consequently, this study adopts the binary Probit model for analysis. There are two stages in the testing process where the binary Probit model is applied. The initial stage entails a preliminary linear estimation of the association between the number of permanent residents and their willingness to transfer in/out. Subsequently, in the second stage, observations from both sides of the income threshold are estimated to ascertain the impact of the number of permanent residents on farmers’ willingness to transfer in/out. The model is specified as follows:

where represents the willingness of farmers to transfer in/out of their rural residential land, represents the number of permanent residents, represents the control variables, represents the random disturbance term, and represents the constant term. , denote the coefficients of the respective variables.

3.4.2. Threshold Regression Models for Cross-sectional Data

In order to examine the phased changes in households’ willingness to transfer in and out of rural residential land based on varying income levels, this study utilizes the threshold regression model proposed by HANSEN [54,55], which is well-suited for analyzing cross-sectional data. The fundamental form of the model is as follows:

where represents the dependent variable, while represents the independent variable. income denotes the threshold variable, which divides the observations into two groups based on the threshold value , , represent the regression coefficients for the two observation groups, and represents the random disturbance term.

The aforementioned threshold regression equation is a piecewise function that is challenging to estimate directly. Therefore, an indicator function is introduced to express it in a unified equation:

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Observations Characteristics

In the survey observations, farmers were categorized based on their willingness to live in urban areas. Among the participants, 235 expressed a willingness to live in city areas, while 269 preferred to live in rural areas. Notably, 58 farmers expressed both intentions. Out of the total number of farmers, 141 indicated a desire to transfer out, while 112 expressed a willingness to transfer in. Additionally, 66 farmers expressed both their intention to transfer out and their intention to transfer in. This section focuses exclusively on the analysis of the characteristics of farmers who have expressed an intention to transfer in or transfer out.

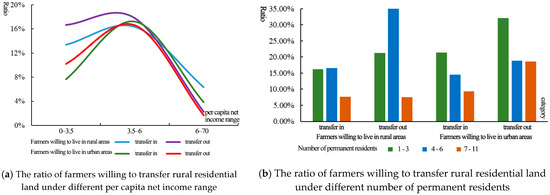

In the survey observations, the number of permanent residents in a household ranged from a minimum of 1 person to a maximum of 11 people. Based on the actual observations’ distribution, this study divided the households into three intervals: 1~3 persons, 4~6 persons, and 7~11 persons. Among the farmers willing to live in rural areas, the proportion of farmers willing to transfer in within each interval is 7.50%, 21.25%, and 35%, respectively, while the proportion of farmers willing to transfer out within each interval is 16.65%, 16.61%, and 7.69% respectively. Among the farmers willing to live in city areas, the proportion of households willing to transfer in within each interval is 21.42%, 9.69%, and 14.50%, respectively, while the proportion of households willing to transfer out within each interval is 32.14%, 18.84%, and 18.80%, respectively.

The highest household per capita net income is 700,000 yuan, and the lowest is 3500 yuan. Based on the actual observations’ distribution, this study divided the farmers into three intervals: 0~35,000 yuan, 35,000~60,000 yuan, and 60,000~700,000 yuan. Among the farmers willing to live in rural areas, the proportion of farmers willing to transfer in within each interval was 13.38%, 16.36%, and 6.32%, respectively, while the proportion of farmers willing to transfer out within each interval was 16.69%, 17.81%, and 2.23%, respectively. Among the farmers willing to live in city areas, the proportion of farmers willing to transfer in within each interval is 7.66%, 17.23%, and 3.83%, respectively, while the proportion of farmers willing to transfer out within each interval is 10.21%, 16.60%, and 1.70%, respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sample description and feature map.

4.2. Baseline Regression Analysis

Table 2 presents the regression results depicting the association between the number of permanent residents and the willingness of farmers to transfer in or out of rural residential land, encompassing farmers willing to live in rural areas as well as those willing to live in city areas. The findings reveal that the number of permanent residents significantly influences only the transfer-in willingness of farmers who intend to remain in the village, with a coefficient of 0.117, significant at the 5% level. This outcome can be elucidated from two potential perspectives. Firstly, within the study area, the number of permanent residents shows no correlation with the transfer-in and transfer-out willingness of farmers who intend to live in city areas or the transfer-in willingness of farmers who are willing to live in urban areas. Secondly, the relationship between the number of permanent residents and the willingness to transfer rural residential land is not simply linear; rather, it may exhibit a more intricate pattern. Consequently, further investigation is warranted to delve deeper into this relationship.

Table 2.

Estimation results of binary Probit model.

4.3. Robustness Test

Taking into account the strategic or courteous underreporting and overreporting tendencies of farmers during on-site surveys, which may lead to extreme values in the survey sample, this study applies Winsorization to remove outliers beyond the 1st and 99th percentiles [53]. Additionally, considering that farmers’ willingness to transfer rural residential land is a result of their comprehensive assessment of their own circumstances, it involves a certain degree of self-selection. This implies that the willingness to transfer is not random among farmers. Therefore, following relevant studies [54], this paper employs the Propensity Score Matching (PSM) method to mitigate this potential issue. After removing outliers, we apply the PSM method, and the results are presented in Table 3, which are largely consistent with those in Table 2. This demonstrates the robustness of the regression results in this study.

Table 3.

Robustness results.

4.4. Estimation Results and Analysis of Threshold Effects

4.4.1. Threshold Estimation Results for Farmers’ Willing to Live in Rural Areas

Firstly, we examine whether there are threshold effects and determine the threshold value for the relationship between the number of permanent residents and the transfer-in and transfer-out willingness of farmers who are willing to live in the village. The results of the analysis indicate that there is a threshold effect for transfer-in willingness in relation to the number of permanent residents, which passes the significance test at a 1% level. The estimated threshold value is 35,000 yuan. However, the threshold effect for the transfer-out willingness does not pass the significance test, indicating the absence of a threshold value (Table 4).

Table 4.

Table of threshold effect test results.

Table 5 presents the relationship between different per capita net income ranges, the number of permanent residents, and the willingness of rural households to transfer to rural residential land. The results indicate that when the household per capita net income is less than or equal to 35,300 yuan, the coefficient of the number of permanent residents does not pass the significance test. However, when the household per capita net income exceeds 35,300 yuan, the coefficient of the number of permanent residents is positive and passes the significance test at the 5% level. For every increase of one permanent resident, the willingness to transfer to rural residential land increases by 1.723%. This suggests a non-linear relationship between the number of permanent residents and the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in rural areas to transfer to rural residential land. As the household per capita net income level increases, the relationship transitions from being unrelated to being promoted. Notably, the number of permanent residents is unrelated to the willingness of farmers to transfer out rural residential land. Hypotheses 1 and 2 are substantiated. Through field surveys, it was observed that in some rural households in Deqing County, the number of permanent residents is relatively high, but they have not met the conditions for household separation, or their income level is insufficient to cover the expenses of housing construction and decoration.

Table 5.

The impact of the number of permanent residents on different income levels on the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in rural areas to transfer rural residential land.

Therefore, they choose not to temporarily separate households and alleviate their living pressure by transferring to rural residential land. It is important to emphasize that the majority of households, as reported in the field survey, incur housing construction costs ranging from 200,000 to 300,000 yuan. Thus, the income threshold calculated in this study does not represent the household per capita net income level required for rural households in Deqing County to meet their livelihood needs, but rather the level that can sustain their lives after transferring to rural residential land and completing housing decoration. Considering the limitations of this survey and the actual circumstances in Deqing County, the income threshold estimated in this study (35,300 yuan) should exceed the income level necessary for rural livelihood in Deqing County (2021 rural subsistence allowance standard: 8890 yuan per person/year), aligning to some extent with reality.

4.4.2. Threshold Estimation Results for Farmers’ Willing to Live in City Areas

Firstly, we examine whether there are threshold effects and determine the threshold value for the relationship between the number of permanent residents and the transfer-in and transfer-out willingness of farmers who are willing to live in city areas. The test results demonstrate a statistically significant double threshold effect of the number of permanent residents on outflow intentions at a 5% significance level. However, the test results do not provide evidence for a triple threshold effect, indicating the presence of two-income thresholds, specifically 37,800 yuan and 56,200 yuan. Conversely, the threshold effect for the inflow intentions does not pass the test, suggesting the absence of a threshold value (Table 6).

Table 6.

Results of threshold effect test.

Table 7 presents the relationship between different per capita net income ranges, the number of permanent residents, and the willingness of farmers to transfer out rural residential land. The results indicate that when the household per capita net income is less than or equal to 37,800 yuan, the coefficient of the number of permanent residents is significantly negative, passing a 5% significance test. This implies that for each additional person in the number of permanent residents, the willingness of farmers to transfer out decreases by 2.711%. Conversely, when the household per capita net income is greater than 37,800 yuan, and less than or equal to 56,200 yuan, the coefficient of the number of permanent residents is significantly positive, passing a 1% significance test. In this case, for each additional person in the number of permanent residents, the willingness of farmers to transfer out increases by 0.598%. However, when the household per capita net income exceeds 56,200 yuan, the coefficient of the number of permanent residents fails to pass the significance test. This suggests a non-linear relationship between the number of permanent residents and the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in city areas to transfer out rural residential land. As the household per capita net income level increases, the relationship transitions from inhibiting to promoting and eventually becomes unrelated. Notably, the number of permanent residents is unrelated to the willingness of farmers to transfer to rural residential land. Hypotheses 3 and 4 are substantiated.

Table 7.

The impact of the number of permanent residents on different income levels on the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in urban areas to transfer rural residential land.

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

In the process of advancing China’s rural residential land system reform, promoting the transfer of rural residential land by farmers becomes crucial for enhancing the efficiency of rural land utilization. Consequently, this aspect has garnered significant attention from experts and scholars. This study is based on survey data from 504 rural households in Deqing County, Zhejiang Province, guided by Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory; the research employs the binary Probit regression model and the threshold model using cross-sectional data, with farmers’ per capita net income as the threshold variable. It explores the non-linear impact of the number of permanent residents on farmers’ willingness to transfer rural residential land, thereby providing valuable insights for both research and practical applications.

Previous research has explored the linear relationship between the number of permanent residents and their willingness to transfer rural residential land [34,38,40]. However, the conclusions drawn have been inconsistent and lacked further analysis. This study reveals a non-linear impact of the number of permanent residents on farmers’ decisions to transfer in and out of rural residential land. Despite appearing unsupported by existing research, this finding warrants further analysis. With the development of China’s socioeconomic landscape, farmers are no longer a homogeneous group [56], particularly in terms of income [46]. This leads to differences in risk perception and perceived benefits among farmers, a phenomenon that has been confirmed by research [57,58]. Moreover, some research suggests that higher income is associated with stronger risk tolerance and a greater willingness among farmers to transfer their rural residential land [31,39,41,59]. Moreover, the progression of urbanization has led numerous farmers to migrate to urban areas; however, certain farmers remain deeply connected to rural heritage and favor residing in the countryside. Hence, when it comes to deciding their future abode, farmers face distinct choices, and this, in turn, affects their willingness to transfer rural residential land. Existing research has already confirmed the validity of this assertion [60,61]. It is worth highlighting that, in contrast to the consolidation and withdrawal of rural residential land, the transfer of rural residential land can be divided into transferring in and transferring out. As bounded rational economic agents, farmers carefully weigh the “cost-benefit” aspect before making their decisions. Intuitively, transferring in rural residential land requires funds, while transferring out can generate income, leading to different financial flows. However, existing research tends to amalgamate both transfer-in and transfer-out decisions under the umbrella term of “transfer”, inadvertently overlooking this significant distinction. In the results of this study, we found that whether it is farmers who are willing to live in the urban areas or farmers who are willing to live in the rural areas, the impact of the number of permanent residents on the willingness of farmers to transfer in and out is different, which also confirms the above statement. Considering all aspects, it is important to acknowledge that existing research has yielded diverse conclusions, which, in their respective contexts of selected study areas and samples, hold validity. The main reasons for the divergent conclusions in existing studies can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, the selected samples may belong to a specific income range, or belong to different income ranges, resulting in variations in the direction of impact. However, the analysis is often not segmented based on income intervals. Secondly, the diversity in farmers’ choices regarding future living locations can also result in differing effects. Lastly, the transfer of rural residential land has not been distinguished between transferring in and out.

From this perspective, the conclusion of a threshold effect in the relationship between the two variables is attributed to the classification of farmers based on their per capita net income level. The research findings also reveal a linear relationship between the number of permanent residents and the willingness to transfer within a certain range of per capita net income, aligning with existing research conclusions to some extent. It also shows that this study complements existing research and enhances result accuracy by comparing the income threshold derived from the threshold regression model with the actual situation. This validation demonstrates the feasibility and generalizability of the chosen model, offering valuable insights for local governments to formulate targeted measures aimed at promoting the transfer of rural residential land.

This study also identified that, theoretically, there is a limitation on the duration of transferring in rural residential land; once the time limit expires, the costs incurred by farmers, such as renovation expenses, may become sunk costs, potentially discouraging them from transferring in rural residential land. Consequently, when there is a larger number of permanent residents in a household, opting for separate applications for rural residential land should be a more reasonable approach. Field research revealed three prevalent situations in certain villages. Firstly, some farmers face low-income levels, making it challenging for them to afford construction and renovation costs after applying for rural residential land. Secondly, some families have a high number of underage members, disqualifying them from meeting the conditions for separate household applications. Thirdly, some villages encounter a scarcity of rural residential land index, rendering them unable to meet the demands for applications. Under these circumstances, farmers tend to prefer transferring to rural residential land. However, during the contract period of transferring, the aforementioned three situations gradually improve. The results of this study lend indirect support to this viewpoint.

Hence, despite a theoretical conflict between transferring to rural residential land and applying for separate household rural residential land, due to practical constraints, transferring to rural residential land can be seen as a supplementary option to separate household applications, representing a novel finding of this study. However, this conclusion has received relatively little attention in existing research. Internationally, developed countries like Europe and the United States exhibit fewer human-land conflicts compared to China. Consequently, their focus lies in achieving rural prosperity through rural residential land transfer to expand functions [62,63,64].

In contrast, In China’s rural society, the primary challenge to address is the conflict between unused rural residential land and the rigid demand for housing construction that cannot be met [65]. Hence, local governments seek to motivate urban-migrated farmers to withdraw their rural residential land in exchange for additional land indicators, enabling them to fulfill new application requirements [66]. While this approach may appear straightforward, it encounters difficulties in practice due to the deeply ingrained traditional beliefs among farmers and the widespread implementation of the system of “separation of two rights”. Consequently, the process of rural residential land withdrawal often faces challenges [67]. Furthermore, even if there is an ample supply of rural residential land, households with low incomes or a high number of underage members still remain unable to apply for rural residential land.

Therefore, we might consider adopting a compromise approach. For farmers who are reluctant to withdraw their rural residential land, we can encourage them to transfer their land, effectively preventing the rural residential land from remaining idle. This approach would also enable farmer households with limited or low incomes, as well as those with a high number of underage members, to have access to usable rural residential land. Certainly, we can interpret this approach as a transitional method. By the time the current rural residential land leasing contracts expire, the tripartite entitlement system for rural residential land has achieved significant success. More farmers will gradually have the willingness to withdraw their rural residential land; the current challenges will also gradually ease. The central government can further introduce policies to promote the revitalization and effective utilization of rural residential land. This proposal holds significant relevance for effectively resolving the historical legacy issues surrounding rural residential land in China.

5.2. Policy Suggestions

This paper analyzes the influence of the number of permanent residents on the willingness of farmers to transfer in or out of rural residential land from the perspective of threshold effects. In the future, Chinese policymakers will need to formulate rural residential land policies at both the macro and micro levels and introduce tailored measures for different types of farmers. This approach will facilitate the effective promotion of rural residential land transfer, unlock the potential of idle rural residential land resources, and enhance the utilization efficiency of rural residential land.

Firstly, the implementation and adherence to the reforming principle of “fairness priority while considering efficiency” are fundamental to actively advancing the reform of the rural residential land system. Based on the fundamental principle of guaranteeing equitable access to rural residential land for all farmers, there is a continual expansion of the transfer scope of rural residential land use rights. This expansion will facilitate the diversification of transfer and utilization methods for rural residential land, enticing urban residents and social capital to invest in rural areas. This will gradually enable the market to assume a vital role in allocating resources on rural residential land and drive the appreciation of its value. On the one hand, it ensures that farmers have access to rural residential land to meet their fundamental requirements for production and livelihood. On the other hand, it enhances farmers’ motivation to utilize rural residential land, leading to indirect improvements in their income and providing additional capital support for those farmers who are transitioning to urban areas. Ultimately, it promotes the transfer of rural residential land farmers. To achieve positive effects, the transfer policies for rural residential land should consider the future living locations and income levels of farmers and establish different priorities accordingly.

Secondly, the process of promoting the transfer of rural residential land should encompass the implementation of tailored policies. In order to achieve positive effects, policymakers of the rural land circulation policy should prioritize which farmers to promote the transfer of rural residential land based on their future living location choices and income levels. Local governments play a dual role in this process. On the one hand, encourage villages to capitalize on their local advantages and develop distinctive industries. On the other hand, they promote the marketization of collectively operated construction land, providing land resources for industrial development. Local governments should actively develop local characteristic industries, extend the industrial value chain, and enhance farmers’ income generation opportunities through industry integration and technical training. This is to continuously meet the livelihood needs of farmers, increase the number of farmers transferring their rural residential land, attract various social entities to invest in rural industries, and increase the number of individuals who wish to acquire rural residential land.

Thirdly, in regard to farmers who express a willingness to relocate to urban areas, the key to reducing their hesitation lies in the implementation of incentivization policies and measures for rural residential land transfer. Farmers with moderate income levels and larger permanent residents should be identified as potential candidates for rural residential land transfers. On the one hand, in the formulation of policies for rural residential land transfer, on the other hand, it is possible to consider relatively affluent social entities, urban residents, and other long-term users as the individuals who transfer in. This would ensure that farmers moving to cities have access to stable income sources. Simultaneously, the usage rights of the rural residential land for these households can be withdrawn, while the qualification rights would remain with the farmers. A possible approach to handling qualification rights is to adopt measures similar to the “qualification rights bank” implemented in Jiangxi Province. Through this system, farmers can continuously receive “interest” from their qualification rights, and the indicators of rural residential land can be utilized by the local government for development purposes.

In relation to farmers who are willing to stay in the village, priority should be given to households with higher income levels but temporary difficulties in separating households. To increase their willingness to transfer in, it is advisable to establish a flexible contractual period for the transfer of the rural residential land. On the other hand, for farmers with higher incomes currently residing in cities who desire to return to their hometowns for retirement, shorter circulation periods can be implemented. The shorter periods not only allow transfer-in farmers to accumulate savings and achieve household separation but also do not impede outgoing farmers from returning to their hometowns for retirement. This approach satisfies the needs of both parties and rejuvenates idle rural residential land.

6. Conclusions

This study is based on field survey data collected from 504 farmers in Deqing County, Zhejiang Province. The farmers are categorized into two groups based on their residential preferences, rural areas or urban areas. Using household per capita net income as a threshold variable, a binary Probit regression model and a threshold regression model with cross-sectional data are employed to analyze the impact of the number of permanent residents on farmers’ willingness to transfer in or transfer out of rural residential land. The following conclusions are drawn: There is a non-linear impact of the number of permanent residents on the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in rural areas to transfer to their rural residential land. The income threshold value is 35,300 yuan. As income levels increase, the effect of the number of permanent residents on farmers’ willingness to transfer shifts from being irrelevant to promoting. There is a non-linear impact of the number of permanent residents on the willingness of farmers who are willing to live in urban areas to transfer out their rural residential land, with two income threshold values of 37,800 yuan and 56,200 yuan. As income levels increase, the effect of the number of permanent residents on farmers’ willingness to transfer out shifts from inhibiting to promoting, ultimately becoming irrelevant. In terms of the magnitude of threshold values, the income threshold of farmers who are willing to live in rural areas to transfer to rural residential land is the lowest, followed by the first income threshold of farmers who are willing to live in urban areas to transfer out rural residential land, while the second income threshold of farmers who are willing to live in urban areas to transfer out rural residential land is the highest. By comparing our calculated income threshold values with the level of subsistence allowance in Deqing County and existing research, we observe a strong alignment with the real-life situation. This coherence substantiates the soundness of our model selection and underscores the practical significance of our findings. Furthermore, the possibility of transferring rural residential land emerges as a complementary strategy for farmers seeking separate household registration, offering a fresh perspective for China to adeptly tackle the historical legacy problems associated with rural residential land.

This article still has certain limitations that need to be explored. The threshold values in the results of this study are estimated based on the sample of observations, and their magnitude is related to factors such as village endowment. As Zhejiang Province is a demonstration area for “common prosperity” in China, the proportion of non-agricultural income for households is relatively high, providing a certain foundation for the gap between permanent population size and income level. However, it is unclear whether there are income threshold effects and differences in income threshold values in other regions of China compared to Deqing County. Due to constraints in time and data, this study did not further investigate these aspects; nevertheless, upon comparison with relevant research conclusions. Nonetheless, when comparing relevant research conclusions, it is found that the impact of the number of permanent residents on the transfer-in and transfer-out of households is influenced by income levels, which still have a certain reference value. Additionally, in contemporary Chinese society, there are “amphibious land use in urban and rural” farmers who possess urban footholds and rural residential land but reside and work primarily in urban areas throughout the year [54]. Due to limitations in data and survey availability, this article did not address these farmers.

As the reform of China’s rural residential land system continues to progress, the issue of rural residential land circulation remains a subject of concern. Subsequent research can delve further into the examination of income threshold values. On the one hand, we can continue to analyze the regional variations and spatial characteristics of income threshold values. On the other hand, a lower income threshold value is more favorable for facilitating rural residential land circulation. Conducting a comprehensive analysis of the impact, direction and extent of the rural residential land system reform on income threshold values can offer improved references and insights for refining the implementation of the rural residential land system reform.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft and investigation, Y.Z.; Investigation writing—review and editing, K.X.; Formal analysis, investigation, H.C.; writing—review and editing, supervision and funding acquisition, Y.H. All of the authors contributed to improving the quality of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 42171263), the Ministry of Education of Humanities and Social Science Project (Grant number 21YJA630033), and the Basic Research Funds for Central Universities (Grant number 2662023YJ006).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

We obtained informed consent from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, Y. Introduction to land use and rural sustainability in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, F.; Li, Y. Key issues of land use in China and implications for policy making. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Zhan, L.; Jiang, G.; Ma, W.; Dong, X. How to Address “Population Decline and Land Expansion (PDLE)” of rural residential areas in the process of Urbanization:A comparative regional analysis of human-land interaction in Shandong Province. Habitat Int. 2021, 117, 102441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Niu, S.; Gu, G.; Huang, X.; Chen, Z. The limited marketization of rural homestead reform: An analytical framework of “People-land-housing-industry”. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2022, 453, 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Torre, A.; Ehrlich, M. Governance Structure of Rural Homestead Transfer in China: Government and/or Market? Land 2021, 10, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Q. The trends, promises and challenges of urbanisation in the world. Habitat Int. 2016, 54, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridding, L.E.; Watson, S.C.L.; Newton, A.C.; Rowland, C.S.; Bullock, J.M. Ongoing, but slowing, habitat loss in a rural landscape over 85 years. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 35, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnå, H.; Aarsæther, N. Combating Depopulation in the Northern Periphery: Local Leadership Strategies in two Norwegian Municipalities. Local Gov. Stud. 2009, 35, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, S.R. Lost in translation: Incomer organic farmers, local knowledge, and the revitalization of upland Japanese hamlets. Agr. Hum. Values 2012, 29, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Guanghui, J.; Wenqiu, M.; Guangyong, L.; Yanbo, Q.; Yingying, T.; Qinglei, Z.; Yaya, T. Dying villages to prosperous villages: A perspective from revitalization of idle rural residential land (IRRL). J. Rural Stud. 2021, 84, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Tang, Y.T.; Long, H.; Deng, W. Land consolidation: A comparative research between Europe and China. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylon, J. Land Consolidation in Spain. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1959, 49, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, D.; Crecente, R.; Alvarez, M.F. Land consolidation in inland rural Galicia, N.W. Spain, since 1950: An example of the formulation and use of questions, criteria and indicators for evaluation of rural development policies. Land Use Policy 2005, 23, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, A.; Lisec, A. Land consolidation for large-scale infrastructure projects in Germany. Geod Vestn. 2014, 58, 46–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.; Feng, C. The Redundancy of Residential Land in Rural China: The evolution process, current status and policy implications. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufty-Jones, R. Governmentalities of mobility: The role of housing in the governance of Australian rural mobilities. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 42, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamin, E.M.; Marcucci, D.J. Ad hoc rural regionalism. J. Rural Stud. 2008, 24, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtslag-Broekhof, S.M.; Beunen, R.; van Marwijk, R.; Wiskerke, J.S.C. “Let’s try to get the best out of it” understanding land transactions during land use change. Land Use Policy 2014, 41, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kang, J. Decision Making and Influencing Factors in Withdrawal of Rural Residential Land-Use Rights in Suzhou, Anhui Province, China. Land 2023, 12, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Long, K. Farmers’ identity, property rights cognition and perception of rural residential land distributive justice in China: Findings from Nanjing, Jiangsu Province. Habitat Int. 2018, 79, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Qu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhan, L.; Guo, G.; Dong, X. Reconstruction of Rural Settlement Patterns in China: The Role of Land Consolidation. Land 2022, 11, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lo, K.; Zhang, P.; Guo, M. Reclaiming small to fill large: A novel approach to rural residential land consolidation in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Tan, R. Patterns of revenue distribution in rural residential land consolidation in contemporary China: The perspective of property rights delineation. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, L.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, H. Research on Hollow Village Governance Based on Action Network: Mode, Mechanism and Countermeasures—Comparison of Different Patterns in Plain Agricultural Areas of China. Land 2022, 11, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Fan, P.; Cheong, K.C. Social learning and dynamics of farmers’ perception towards hollowed village consolidation. Habitat Int. 2022, 128, 102652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Song, G.; Liu, S. Factors influencing farmers’ willingness and behavior choices to withdraw from rural homesteads in China. Growth Chang. 2021, 53, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Jiang, J.; Yu, C.; Rodenbiker, J.; Jiang, Y. The endowment effect accompanying villagers’ withdrawal from rural homesteads: Field evidence from Chengdu, China. Land Use Policy 2020, 101, 105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, H. Has farmer welfare improved after rural residential land circulation? J Rural Stud 2019, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wu, Y.; Chen, L. Does the land titling program promote rural housing land transfer in China? Evidence from household surveys in Hubei Province. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Torre, A.; Ehrlich, M. The impact of Chinese government promoted homestead transfer on labor migration and household’s well-being: A study in three rural areas. J. Asian Econ. 2023, 86, 101616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, G.; Zhao, W. Using Risk System Theory to Explore Farmers’ Intentions towards Rural Homestead Transfer: Empirical Evidence from Anhui, China. Land 2023, 12, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Lu, X.; Weibo, Z.; Wu, M. A Study on Farmers’ Identity with the Welfare of Homestead Transfer: A Case Study of Hubei Province. J. China Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2021, 42, 194–202. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Hui, E.C.; Lang, W.; Zheng, S.; Qin, X. Transition from factor-driven to innovation-driven urbanization in China: A study of manufacturing industry automation in Dongguan City. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 59, 101382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Fei, L. The unbalanced behavior between Farmer’ farmland transfer and rural residential land withdrawal: A Case Study of Jinzhai County. China Land Sci. 2019, 33, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. The impacts of internal demands, external policy factors on household willingness of homestead withdraw——A survey from the perspective of Maslow’s demand theory. J. China Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2023, 44, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Wang, Y. Evolution characteristics and driving factors of negative decoupled rural residential land and resident population in the Yellow River Basin. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Cheng, S.; Wu, H.; Wu, Q. Homesteads, Identity, and Urbanization of Migrant Workers. Land 2023, 12, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, P.; Tian, Y.; Zou, Y. A novel framework for rural homestead land transfer under collective ownership in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Fu, C.; Kong, S.; Du, J.; Li, W. Citizenship Ability, Homestead Utility, and Rural Homestead Transfer of “Amphibious” Farmers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, A.L.; Dou, Y.D. Farm households’ perception and responses to homestead: A case study of 2typical village in Linhu County, Hengyang City. Resour. Sci. 2015, 37, 654–662. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, H.; Ling, Y.; Shen, T.; Yang, L. How does rural homestead influence the hukou transfer intention of rural-urban migrants in China? Habitat Int. 2020, 105, 102267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Jiang, C.; Meng, L. Leaving the Homestead: Examining the Role of Relative Deprivation, Social Trust, and Urban Integration among Rural Farmers in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, H.A. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Ge, Y.; Cao, H.; Zhai, R. Withdrawal and Transformation of Rural Homesteads in Traditional Agricultural Areas of China Based on Supply-Demand Balance Analysis. Front. Env. Sci. 2022, 10, 897514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Wu, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Q. The Functional Value Evolution of Rural Homesteads in Different Types of Villages: Evidence from a Chinese Traditional Agricultural Village and Homestay Village. Land 2022, 11, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yu, C.; Jiang, J.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, Y. Farmer differentiation, generational differences and farmers’ behaviors to withdraw from rural homesteads: Evidence from Chengdu, China. Habitat Int. 2020, 103, 102231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z. Tripartite entitlement system of rural residential land: From the target of property rights allocation to the realization in legislation. China Land Sci. 2019, 33, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Mo, Z.; Peng, Y.; Skitmore, M. Market-driven land nationalization in China: A new system for the capitalization of rural homesteads. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S. Research on Reform of Distribution Policy and System Allocation of Homestead. J. Political Sci. Law 2021, 200, 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, N.; Sun, B.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, X. Future expectation, farmers’ differentiation and decision of withdrawing from rural homesteads. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin Resour Env. Yangtze Basin 2021, 30, 2383–2391. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, G.; Gai, L. Discussion on the rural residential land “Separating Rural Land Rights” Reform under the background of rural revitailzation. Econ. Manag. 2021, 35, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, Z. Influencing factors of farmers’ willingness to withdraw from rural homesteads: A survey in zhejiang, China. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ni, X.; Liang, Y. The Influence of External Environment Factors on Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads: Evidence from Wuhan and Suizhou City in Central China. Land 2022, 11, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.E. Threshold effects in non-dynamic panels: Estimation, testing, and inference. J. Econom. 1999, 93, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.E. Sample Splitting and Threshold Estimation. Econometrica 2000, 68, 575–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Li, X.; Zeng, L. Impact of farmers’ capital endowment on eco-efficiency of rice production—A case study of Hubei Province. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2022, 43, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, D. Farmland transfer and farmers’ income growth: Based on the perspective of income strcture. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2022, 32, 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Yaoyang, Z.; Scott, C.; Hongqing, L. Farmers’ Economic Status and Satisfaction with Homestead Withdrawal Policy: Expectation and Perceived Value. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7110. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Li, J.; Wang, Y. Effects of Livelihood Capital on the Farmers’ Behavioral Intention of Rural Residential Land Development Right Transfer: Evidence from Wujin District, Changzhou City, China. Land 2023, 12, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Tai, X. The Impact of Rural Housing Security on the Willingness of Homestead Transfer. Contemp. Econ. 2021, 518, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Bao, T. An empirical study on the factors influencing farmers’ willingness to settle in the city in the process of urbanizatiom. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2019, 33, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, B. Tourism, farm abandonment, and the ‘typical’ Vermonter, 1880–1930. J. Hist. Geogr. 2004, 31, 478–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, M. Rural tourism in Southern Germany. Ann. Tourism. Res. 1996, 23, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, C.; Sofer, M. Land use changes in the rural–urban fringe: An Israeli case study. Land Use Policy 2013, 33, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Wu, J.; Zhou, L.; Chen, H.; Yang, Q. The Functional Evolution and Dynamic Mechanism of Rural Homesteads under the Background of Socioeconomic Transition: An Empirical Study on Macro- and Microscales in China. Land 2022, 11, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Chai, Y.; Zhu, W.; Ping, Z.L.; Zong, H.N.; Wang, S. Archetype analysis of rural homestead withdraw patterns based on the framwork of “diagnosis-design-outcome”. Resour. Sci. 2021, 43, 1293–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y. Pilot reform of rural homestead withdraw: Model, dilemma and countermeasures. Truth Seek. 2019, 450, 84–97. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).