Abstract

This study discusses the mechanism of social trust and legal institutions and their impact on farmers’ contract selection in the farmland transfer market from the perspective of contract governance. Using data from a survey of 128 villages in Heilongjiang, Henan, Zhejiang, and Sichuan provinces, this study empirically tests the impact of social trust and legal institutions on the binding force of contracts, and the proportions of paper and long-term contracts in the farmland transfer market. The results showcase, first, that improvement in social trust and legal institutions can strengthen the binding force of farmland contracts. The strength of legal institutions, as embodied in regulation files and execution, and of social trust, as embodied in village neighborhood relations and loan relations, have significant positive impacts on the binding force of contracts in the farmland transfer market. Second, the binding force of contracts positively impacts both paper and long-term contracts in the farmland transfer market. Whether contract execution or dispute resolution rates are selected as the proxy variables for the binding force of contracts, the stronger the contract binding force, the higher the proportion of both paper and long-term contracts in the farmland transfer market. Therefore, improving formal and informal social systems to enhance contractual binding force is of great importance in standardizing contracts and improving the efficiency of market resource allocation.

1. Introduction

Since 2000, China’s farmland transfer market has developed rapidly. Although the government has repeatedly promoted the standardization of farmland transfer transactions, farmland transfers generally take the form of oral and short-term contracts. Since the document “Several Opinions on Strengthening Agricultural Infrastructure Construction and Further Promoting Agricultural Development to Increase Farmers’ Income” proposed that “farmland contract administration departments should strengthen land transfer intermediary services, improve land transfer contract, registration, records and other systems” in 2008, the central “No. 1 document” continued to pay attention to the transfer of farmland from 2013 to 2015. In July 2016, the Ministry of Agriculture issued the Operation Standards for the Transfer and Trading Market of Rural Land Management Rights (Trial), which required that farmland transfer be guaranteed to be open, fair, and standardized. Both parties were required to conclude contracts to agree on the transfer period, use, price, and liability for breach of contract. Agricultural policies actively promote the standardization of market transactions for farmland transfer. However, statistics show that 70.71 million farmers have transferred their contracted farmland, with a total area of 34.1 million hectares in China until 2017. The number and area of total farmland transferred by farmers’ accounts for 31.2% and 37.0%, respectively, of which farmland transferred through nonwritten contracts accounts for 31.7%. Many studies and surveys have shown that oral contracts account for a relatively high proportion of farmland transfers [1,2,3]. About half or more of the transfer contracts do not have an agreed term, even if the agreed term is usually 1 year [4,5,6,7]. The “non-standard” contract of farmland transfer may not only affect farmers’ rights and interests concerning farmland, investment in agricultural production, and utilization of land [8,9,10] but also affect the allocation of farmland resources in the transfer market and the development of agricultural modernization [11,12]. Therefore, agricultural policies and academic scholars have been widely concerned with transfer contracts.

Scholars have conducted many investigations on the phenomenon of oral and short-term farmland transfer contracts, but no consensus has been reached, and further research is needed. The existing literature mainly focuses on three dimensions. First, research on the dimension of farmers’ characteristics has analyzed the influence of factors such as farmers’ population structure, non-agricultural employment, behavioral ability, social capital, and risk preference on the form and term selection of transfer contracts [13,14]. Second, research on the dimension of farmland property rights has analyzed the multiple functions of farmland, and the different forms and terms of contracts that contain different property rights contents and transaction costs [15]. The stability of farmland property rights and transaction costs are believed to be key factors affecting the selection of farmers’ farmland contracts [16,17,18]. The third dimension concerns social factors. On the one hand, research has emphasized the influence of “differential patterns” of traditional rural culture on the form and rent of farmland transfer contracts [19,20]. On the other hand, research has paid attention to the influence of factors such as trust and reputation in rural society on the performance and governance of transfer contracts [21]. Although the literature has provided rich interpretations of oral and short-term farmland transfer contracts, such research tends to focus on analyzing farmland transfers, and there are deficiencies in the understanding of regional differences and changing trends of farmland contracts in the transfer market. According to a large-scale grain production survey conducted by the Nanjing Agriculture University research group in 2017, the ratios of farmland transfer in Heilongjiang, Henan, Zhejiang, and Sichuan were 43%, 61%, 41%, and 34%, respectively. However, the areas covered by paper contracts accounted for 71.5%, 63.9%, 75.6%, and 49.2%, and 84%, 80%, 18%, and 68% of the written contracts had a transfer term of three years or less, respectively. In regions with similar farmland market development, there was a significant difference in the proportions of written and long-term contracts. However, existing research conclusions do not provide a full explanation.

From the perspective of theory and practice, oral and short-term farmland transfer contracts 1 are closely related to the performance environment of the farmland market and the binding force of the contract. Existing literature on farmland transfer contracts focuses on the conclusions and influencing factors of the contracts but ignores the effects of their operability and enforceability [22,23,24]. Because of the uncertainty and complexity of the external environment, information is difficult to obtain or verify. The parties reach contracts based on limited rationality [25] because contract design cannot consider all problems and possibilities. Therefore, the performance of the contract needs to rely on “mortgage, trigger strategy, reputation, trust,” and other protection mechanisms [26]. Hence, the different institutional factors that guarantee contract performance may lead to systematic differences in the selection of farmland transfer contracts between regions. According to provincial data in the Annual Report of China Rural Operation and Management Statistics, the number of disputes over farmland transfers between 2015 and 2018 was as high as 418,000 cases per year [27]. Other research shows that owing to the long mediation time of circulation disputes and high transaction costs, many disputes and contradictions are not resolved. Interest disputes in the transfer of farmland remain common [28], and the social trust and legal institutions that guarantee the execution of contracts are also changing in the process of factor marketization. Urbanization has accelerated the collapse of the “acquaintance society” in rural areas, bringing about a gradual transformation of the rural fulfillment mechanism from the trust constraint of “rule by man” to the institutional constraint of “rule by law.” Differences in the degree of transformation of the implementation mechanism between regions may lead to differences in the contract structure of the farmland transfer market. On the one hand, the different rural social patterns between regions may create heterogeneity in social trust. On the other hand, although there is consistency in the formulation and promulgation of laws, due to different degrees of reform of the old system in different regions, the implementation efficiency and information transparency of the judicial system are significantly different [29]. This leads to differences in the degree of social trust and legal institutions between regions, which is related to the contract binding force of the farmland transfer market [22]. This affects farmers’ contract selection and market resource allocation. This paper focuses on the following questions: In the context of factor marketization, will social trust and legal institutions lead to systematic differences in the contract structure in the farmland transfer market? What is the underlying mechanism of influence?

This paper systematically analyzes the influence of social trust and legal institutions on contract structure and resource allocation in the farmland market. An empirical test is conducted using survey data from 128 villages in Heilongjiang, Henan, Zhejiang, and Sichuan provinces, which have significant differences in agricultural resource endowment and economic development. Through an analysis of households and villages, this paper reveals the influence and mechanism of social trust and legal institutions on the contract structure of the transfer market. This conclusion is helpful in analyzing the relationship between the allocation of market resources and rural social governance in the market-oriented context of current factors. The academic contributions and characteristics are discussed in the following two respects. First, based on contract binding, this paper explains the reasons for farmers’ contract selection in the farmland transfer market, which breaks from the traditional conclusion drawn from the perspective of farmers’ heterogeneity. The results are helpful in deepening the understanding of farmers’ contract selection behavior and supplement and enrich the understanding of the factors influencing contract selection in the transfer market. Second, the paper reveals the impact and mechanism of the performance environment on contract binding and market contract structure from the perspectives of social trust and legal institutions, which is helpful in analyzing the relationship between factor market development and rural social governance in the current factor marketization context. The paper also investigates the impact of rural legal system construction on the market resource allocation of farmland transfers.

2. Framework and Hypotheses

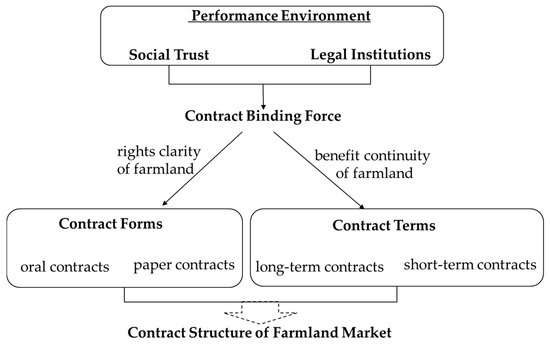

In the rational “economic man” model, a farmer’s choice of contracts usually depends on a comparison of the income produced by contracts of different forms and terms. Regardless of whether the contracts chosen are paper or oral, long-term or short-term, the implementation and execution of contracts cannot be separated from specific constraints. As an important guarantee mechanism for contract performance, social trust and legal institutions mainly set binding contracts by adjusting the cost of a breach, thus affecting the choice of contract between two parties in the farmland market. To explore the influence and mechanism of social trust and legal institutions on the contract structure of the farmland transfer market, the following section gradually analyzes and tests the influence of social trust and legal institutions on contract binding and the influence of contract binding force on farmers’ contract selection. The analysis framework is shown in Figure 1

Figure 1.

The effect mechanism of performance environment and contract binding force on the contract structure of farmland transfer market.

2.1. Influence of Social Trust and Legal Institutions on Contract Binding under Factor Marketization

According to economics theory, not all problems and possible emergencies can be considered in the contract design process because of incomplete information. The contracting parties can only set a contract on the basis of limited rationality, so its execution relies on external protection mechanisms [26], such as mortgages, reputation, trust, legal systems, and arbitration. If the mechanism to protect contract execution is not perfect, it will lead to a lack of effective binding force. From an economic perspective, the mechanism that guarantees contract execution involves enhancing the contract’s binding force by increasing the cost of a default. In contract execution, whether the contracting party violates the contract or not depends on a comparison between the costs and the benefits of the breach. When the breach is not punished or enforcement is insufficient, a “rational person” inevitably decides that a breach is profitable. Furthermore, when the expected costs of a breach are high, the “losses outweigh the gains,” and the contracting party will strictly comply with the terms of the contract.

From a contract governance perspective, the guarantee mechanism of contract performance includes two aspects: social trust and legal institutions. In a traditional rural acquaintance society, long-term and stable interpersonal communication and activities have built stable social relationships with differential patterns based on blood and geography [30]. The farmland transfer market is not purely a factor market. It is not purely business but also integrates multiple factors such as human relations, beliefs, and clan culture. Information on any breach of contract spreads quite easily among villagers, and the cost of such a breach is the rupture of credit or reputation. The label of dishonesty increases the cost of follow-up interpersonal communication or transactions, resulting in damage to one’s long-term interests [31]. As a special performance mechanism, social trust transforms a breach of contract into a kind of social pressure that plays an important role in stimulating and restricting each member’s economic behavior. On the other hand, the legal system is a formal system endorsed by potential state coercive force. As a code of conduct or rule, it guides people’s actions, excludes certain behaviors, limits possible reactions, and provides definite order and “external support” for social interaction [32]. The formal system usually ensures adherence to the contract and punishes default by stipulating a breach cost. The contracting parties generally perform the contract as promised based on legal constraints and fear of possible penalties for a breach, which prevents confusion and arbitrary behaviors, to reduce the risk of a future breach and improve contract binding.

With the development of marketization, the frequent flow of the rural population disrupts the original pattern of rural governance; not only does it dissolve the governance functions of informal institutions such as family ethics, social customs, and moral concepts to a large extent, but also impairs the transmission mechanism of social trust based on an acquaintance society [22,33]. A trust-breaker in social activities can change their living area to avoid long-term losses that may be caused by trust breaking. When the “punishment” incurred by trust breaking is reduced, the binding force of the contract is weakened [3,22,34]. The payer may also be cautious because of the uncertainty of future returns or increased risks. In this context, legal institutions provide norms for a gradually estranged rural society. The universality of rules and the compulsory punishment mechanisms have become the main basis for villagers to maintain the relationship between mutual responsibilities and obligations and solve rural social disputes. A legal institution, as a code of conduct or rules, guides people’s behavior by constraining or penalizing rule-breaking with potential state coercive power. In addition, it increases the behavioral costs of rule-breakers in interpersonal communication, which strengthens the contract binding force. People are generally concerned with the possible punishment for a breach of contract, which leads them to follow the legal system and standardize their own behavior [32]. Thus, they develop good social order and norms. However, the weakening of social trust in the process of factor marketization does not imply that social trust has no effect on contract binding within legal institutions. In reality, because of the difficulty of observing or verifying information, it is impossible to consider all problems or emergencies when setting a contract. In addition, the judgment and implementation of the legal system involve time and human resource costs. Even if the legal system is complete, some situations regarding contract performance cannot be completely resolved by legal provisions. To some extent, this still depends on trust between the contracting parties [35,36], so the weakening of social trust will inevitably reduce contract binding force.

Therefore, we propose the first hypothesis: in the context of factor marketization, the weakening of social trust negatively affects contract binding, whereas the enhancement of legal institutions has a positive impact.

2.2. Analysis of the Influence of Contract Binding on the Contract Structure of the Farmland Transfer Market

Farmlands are the most important means of production, and are an important way for families to obtain employment and income. Farmlands have multiple functions, such as social security, employment, and pensions. These multiple functions determine how the contents involved in transfer transactions of farmland vary, such as currency, physical goods, mutual labor assistance, property rights protection, and human exchange. In the following section, we compare the differences in the transaction content of farmland transfer contracts of different forms and terms. On this basis, the influence of insufficient contract binding on the income produced by different transaction contents of farmers is discussed, and then the differences in contract selection in the farmland transfer market under different contract binding conditions are systematically discussed. The following are analyzed based on the form and terms of the contract.

First, from the perspective of contract forms, there are differences in the clarity of farmland rights and interests as defined by paper and oral contracts. Generally, a paper contract specifies the circulation period, rent, breach clauses, and other aspects, and clearly divides the rights and responsibilities of both sides of the transaction. In the event of a breach, a third party can be introduced to intervene, and the black and white nature of the contract can provide effective evidence. However, contracts reached through oral negotiations are often empty. Compared with a written contract, they more clearly define the rights and responsibilities of the contracting parties and reduce the uncertainty of farmland rights and interests in the transfer transaction. These are embodied in three aspects: (1) The contract clarifies the distribution of farmland rights and interests between the contracting parties, weakens the information asymmetry, and reduces the uncertainty of the transaction in the transfer. (2) The contract clarifies the management rights of farmland, which reduces the management uncertainty caused by the change of farmland in the course of production and management. (3) The contract clarifies the right to distribute income to reduce the income uncertainty that may be caused by post-opportunistic behavior.

However, paper contracts would reduce the uncertainty of farmland rights and interests depending on the effective execution of contracts [37]. The “white paper” written contract clearly defines the rights and interests of farmland; however, if it is not effectively protected when infringed or the transaction cost is high, this will result in uncertainty about the rights and interests of farmland defined by the paper contract. Under the condition of insufficient contract binding force, there is no significant difference in the uncertainty of farmland rights and interests defined by paper versus oral contracts. This reduces farmers’ willingness to choose paper contracts to ensure the stability of rights and interests [38]. The measures that exportation may take include choosing transfers to relatives and friends, linking farmland trade, and human rights exchange, which guarantee the stability of future rights and interests of farmland. Therefore, under the condition of insufficient contract binding force, farmers are more likely to choose an oral contract in the farmland transfer market, as in the traditional countryside of China. That is, the weakening of contract binding reduces the proportion of farmland area under written contracts in the farmland transfer market.

Second, from the perspective of contract terms, long- and short-term contracts differ in the benefit continuity of farmland transfers. Compared with short-term contracts, long-term contracts can not only enhance the sustainability of farmland management and reduce the operational uncertainty caused by frequent transactions of property rights but also facilitate the investment and long-term planning of operators to obtain higher returns. The transferred farmland households have a higher willingness to pay rent, and long-term contracts tend to have higher rents than short-term contracts. Thus, long-term contracts can enhance the continuity of benefits in a revolving trade. Although long-term contracts may face certain risks, under the balance of sustained benefits and risks, “rational” farmers will choose a contract term that maximizes their utility. On the one hand, due to the consideration of property rights protection, employment security, and other factors, farmers may “transfer” part of the rent to short-term contracts to reduce risks. On the other hand, when the income difference between long- and short-term contracts is sufficiently large, farmers may be willing to bear the risks incurred by long-term contracts.

However, the lack of contract binding force increases the uncertainty of long-term contract benefits, increases the risk of long-term management for farmers, and weakens agricultural production investment and motivation for the long-term management of the transferred farmland households. This reduces the willingness of the transferred households to pay high rents for long-term transfers. This change will not only reduce the marginal income of farmers who choose long-term contracts to bear risks but also narrow the gap between long-term and short-term contract rents, thus weakening farmers’ willingness to bear risks in long-term contracts. The possible measures taken by the transferee are signing short-term transfer contracts, which reduces the uncertainty caused by the lack of binding force by shortening the transfer period, increasing the transaction frequency, reducing the risks in farmland transactions, and ensuring the continuity of returns. Therefore, under the condition of insufficient contract binding force, farmers are more likely to choose short-term contracts in the farmland transfer market. This means that weakening the contract binding force reduces the proportion of farmland area with long-term contracts in the farmland transfer market.

In conclusion, contract binding affects the stability of the property rights of transferring farmland, leading to a difference in the proportion of farmland areas that choose paper contracts and long-term contracts in the transfer market under different conditions of contract binding. Owing to the heterogeneity of the transaction contents of contracts of different forms and terms in farmland transfer and the substitution effect between different transaction contents, there are differences in the incomes of contracts with different transaction contents under different binding conditions.

Therefore, we propose the second hypothesis: Contract binding is an important factor affecting farmers’ contract selection in farmland transfer. The weakening of contract binding reduces the proportion of farmland area in which farmers choose paper contracts and long-term contracts, thus affecting the contract structure in the farmland transfer market.

3. Method

3.1. Model

The first step is to test the influence of social trust and legal institutions on contract binding in the context of factor marketization development. The econometric model is set as follows:

In Formula (1), the variable represents the contract binding in village . It is difficult to measure contract binding because of its concealment and many influencing factors. The performance of the farmland transfer contract can be divided into two situations: full execution according to the agreed content by both parties and liability for breach of contract. Therefore, contract binding is reflected in both contract performance and dispute resolution. Thus, this study chooses the contract execution rate and dispute resolution rate in village-level contracts as contract-binding agent variables in the model analysis. The village-level survey asked the following questions: “How many disputes have occurred in the village every year since 2005?”, “How many disputes have been resolved?”, and “What is the number of farmers transferring farmland in the village?” Therefore, the contract execution rate is expressed as (1 − the total number of farmland disputes/the total number of farmers in the village) × 100, and the resolution rate of disputes is expressed as the ratio of the number of disputes resolved to the total number of farmland disputes.

The key variable represents the internal social trust of village , by asking farmers “if they trust their neighbors to guard their house” and “if they are willing to lend money to close relatives or friends.” The proportion of farmers who answer “agree” or “strongly agree” is used to build the village’s level of social trust indices. represents the legal institutions of village . Usually, mediation or arbitration by the township government and arbitration organizations is the most important legal approach to solving farmland disputes. The measurement of the strength of legal institutions focuses on the system provisions and implementation related to the arbitration of farmland disputes. The survey asks “Has the township issued any documents on land dispute arbitration in the past three years?” and “Have townships organized special meetings on arbitration of land disputes in the last three years?” to construct an index of the intensity of legal institutions at the village level. is the model disturbance term. In the parameter estimation, we use sub-indices to measure the intensity of social trust and legal institutions in villages, which are directly inputted into the model for parameter estimation and hypothesis testing. We then construct a comprehensive index of social trust and legal institutions, which is constructed from two dimensions and added with the same weight for the robustness test.

The second step is to test the impact of contract binding on the contract structure of the farmland transfer market, which includes the contract form and contract term. The econometric models are set as follows:

In Formula (2), the variable represents the proportion of paper contracts, measured by the proportion of the area signed with paper contracts in the area of farmland transfer in village i.

In Formula (3), the variable represents the proportion of long-term contracts, measured by the proportion of the area signed with a term of more than three years in the area of farmland transfer in village i. represents a series of control variables that may affect the contract structure. is the model disturbance term.

3.2. Data Collection and Variable Assignment

This study empirically analyzes data from a large-scale grain production household survey conducted by a research group from Nanjing Agriculture University. The survey adopted a multi-stage sampling method and was conducted in Heilongjiang, Henan, Zhejiang, and Sichuan provinces, which differ in resource endowments and economic development. Four sample cities were randomly selected from each province 2, two towns were randomly selected from each sample city, and thirty-two farmers were randomly selected from two villages within each town. The sample covers 128 villages and 1040 households in the four provinces. The questionnaire is divided into two parts: household and village questionnaires. The data used in this paper include population and farmland resource information, economic development level and employment situation, farmland circulation market development, contract selection, contract binding, and agricultural policy information for 128 villages. The variable assignments and descriptive statistics of the models are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable definitions and descriptive statistics.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. The Effect of Social Trust and Legal Institutions on Contract Binding

4.1.1. Correlation Test of Social Trust and Legal Institutions with Contract Binding

As shown in Table 2, differences in contract binding in villages with different levels of social trust and legal institutions are analyzed, and T-tests are conducted. The village samples were divided into two groups by comparing the provincial means in the grouping of social trust indicators. Additionally, the villages were divided into two groups according to the answers of “yes” and “no” in the legal institution indicators. We then counted and tested the differences in contract binding among the different groups.

Table 2.

Correlation test of social trust and legal institutions with contract binding.

The results of the grouping statistics and testing are as follows: (1) For social trust, the contract execution and dispute resolution rates of the village group with stronger social trust are higher than those of the village group with weaker social trust. Among them, the contract execution and dispute resolution rates of villages that are above the provincial mean for “the proportion of farmers trusting their houses to neighbors” were 7.47% and 7.33% higher, respectively, than the villages that are below the provincial mean. The contract execution and dispute resolution rates of villages that are above the provincial mean for “the proportion of farmers who would lend money to non-relatives or friends” were 2.65% and 14.68% higher, respectively, than the group below the provincial mean. The standardized index of social trust also shows that the contract execution and dispute resolution rates of villages in the group above the provincial mean were 5.82% and 9.65% higher, respectively, than those in the group below the provincial mean. The results indicate that the higher the social trust reflected by the standardized index, the stronger the contract binding force in the farmland transfer market. (2) For legal institutions, the contract execution and dispute resolution rates of the village group with stronger legal institutions are higher than those of the village group with weaker legal institutions. As shown in Table 2, the contract execution and dispute resolution rates of villages in which the “township has issued documents on farmland dispute arbitration” are 6.88% and 7.01% higher, respectively, than those that have not issued such documents. Additionally, the contract execution and dispute resolution rates of villages in which the “township has organized meetings on land dispute arbitration” are 4.43% and 8.24% higher, respectively, than those that have not organized arbitration meetings. The results indicate that the higher the level of legal institutions reflected by the standardized index, the stronger the contract binding force in the transfer market.

The above statistics and tests of the correlation between social trust, legal institutions, and contract binding force show that social trust and legal institutions are positively correlated with contract binding force, which is consistent with the expectation of the theoretical analysis.

4.1.2. Empirical Analysis of the Influence of Social Trust and Legal Institutions on Contract Binding

Table 3 reports the estimation results of the standardized index econometric model of the influence of social trust and legal institutions on contract binding force. Columns (1) and (2) show the estimation results of the standardized index econometric model that selects the contract execution and dispute resolution rates, respectively, as proxy variables for contract binding force. The above model adopts a robust estimation of the least-squares method for clustering at the village level. The R-squared and goodness-of-fit F-test statistics of the model estimation show that the model has a good overall fit and a high degree of explanation for the key variables.

Table 3.

The effect of social trust and legal institutions on contract binding.

As shown in Column (1), the model parameter estimation shows a positive relationship between standardization of social trust and the legal institution strength index with the contract execution rate. This indicates that social trust and legal institutions in the farmland market strengthen the contract binding force. Specifically, when the standardized index of social trust increases by 1 percentage point, the contract execution rate of farmland transfer increases by 0.148 percentage points, which is statistically significant at the 5% level. Compared to villages with low legal institution intensity, the contract implementation rate in regions with high legal institution intensity is 4.661 percentage points higher, which is statistically significant at the 1% level. Parameter estimation in Column (2) shows a positive correlation between the standardization of social trust and the legal institution strength index with the dispute resolution rate. Specifically, when the regional social trust standardization index increases by 1 percentage point, the dispute resolution rate of the farmland transfer market increases by 0.217 percentage points, which is statistically significant at the 10% level. In addition, compared with regions with lower legal institution intensity, the dispute resolution rate in regions with stronger legal institution intensity was 9.278 percentage points higher, and the parameter was estimated to be statistically significant at the 1% level. In summary, whether the contract execution rate or dispute resolution rate is selected as the proxy variable for contract binding, improvements in social trust and legal institutions have a positive impact on contract binding in the farmland transfer market. These results verify our first hypothesis.

4.1.3. Robustness Analysis

The following replaces the standardized index with a single standardized index of social trust and legal institutions to analyze its impact on contract binding force. Table 4 reports the model estimation results for the impact. The least squares method was used to robustly estimate village-level clustering in all models. Columns (3) to (6) show the estimation results of the model that selects social trust indices 1 and 2 to replace the standardized index of social trust. Columns (7) to (10) show the model estimation results of replacing the standardized index of legal institutions with indices 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 4.

The effect of social trust and legal institutions on contract binding (single standardized index).

From the analysis results of the contract execution rate, Columns (3) and (4) show that social trust indices 1 and 2 are positively related to the contract execution rate when controlling for the standardized index of legal institutions. Specifically, when “the proportion of households who trust their neighbors to guard their house” increases by 1 percentage point, the contract execution rate increases by 0.141 percentage points, which is statistically significant at the 5% level. When “the proportion of households who would lend money to non-relatives or friends” increases by 1 percentage point, the contract enforcement rate increases by 0.099 percentage points. Columns (7) and (8) show that legal institutions indices 1 and 2 are positively correlated with the contract execution rate. Specifically, the contract execution rate of villages in which the “townships have issued documents on arbitration of land disputes” was 5.204 percentage points higher than villages without issuing such documents. The contract execution rate in villages in which the “townships have organized meetings on arbitration of land disputes” was 6.950 percentage points higher than that in villages without such arbitration meetings, and both were statistically significant at the 5% level.

From the analysis results of the dispute resolution rate, columns (5) and (6) show that legal institution indices 1 and 2 are positively related to the dispute resolution rate when controlling for the standardized index of social trust. Specifically, when the indices “the proportion of households who trust their neighbors to guard their house” and “the proportion of households who would lend money to non-relatives or friends” increase by 1 percentage point, the dispute resolution rate increases by 0.101 percentage points and 0.299 percentage points, respectively, both of which are statistically significant at the 10% level. Columns (9) and (10) show that legal institution indices 1 and 2 are positively correlated with the dispute resolution rate when controlling for the standardized index of social trust. Specifically, the dispute resolution rate of villages in which “townships have issued documents on arbitration of land disputes” was 8.826 percentage points higher than that of villages without issuing such documents. The dispute resolution rate in villages in which “townships have organized meetings on arbitration of land disputes” was 15.172 percentage points higher than in villages without such arbitration meetings, and this parameter was statistically significant at the 5% level.

The above analysis shows that the parameter estimation results of the standardized index of social trust and legal institutions have a high degree of consistency. The results indicate that whether the social trust index replaces the standardized index or the legal institutions index replaces the standardized index, the improvement in social trust and legal institutions has a positive impact on contract binding in the farmland transfer market. The robustness of the analysis results is tested, and the first hypothesis is again verified. The following section further examines the differences between paper and long-term contracts in the transfer market under different contract binding conditions, and then clarifies the impact on the contract structure of the farmland transfer market.

4.2. Influence of Contract Binding on the Contract Structure of the Farmland Transfer Market

4.2.1. Correlation Test between the Contract Binding Force and Contract Structure of the Sample Villages

As shown in Table 5, the proportion of paper and long-term contract areas in farmland transfers under different contract binding conditions is calculated in different groups, and T-tests are conducted. The results show that the proportion of paper and long-term contract areas in the farmland market in the low contract execution rate group is significantly smaller than that in the high contract execution rate group. Specifically, the paper and long-term contract areas in the low contract execution rate group are 31.98% and 29.20%, respectively, which are 10.04% and 11.90% lower than those in the high contract execution rate group, respectively. Moreover, the T-test value for the difference between the two groups is significantly below the threshold p-value of 10%. The results show significant differences between the paper contract area proportion and long-term contract area proportion of the village samples grouped by contract execution rate. In addition, when divided by dispute resolution rate, the proportion of paper and long-term contract areas in the transfer market of the group with a low dispute resolution rate is significantly smaller than that of the group with a high dispute resolution rate. Specifically, the paper contract area of village samples in the low dispute resolution rate group was 32.88%, and the long-term contract area accounted for 29.18%; these values were 9.36% and 12.81% lower in the high dispute resolution rate group, respectively. The T-test values of the differences between the two groups were significant below the threshold p-values of 10% and 5%, respectively. The results show significant differences in the proportion of paper and long-term contracts in villages grouped by the dispute resolution rate.

Table 5.

Correlation test of contract binding and contract structure of the farmland transfer market.

4.2.2. Empirical Analysis of the Impact of Contract Binding on the Contract Structure of the Farmland Transfer Market

Table 6 shows the estimated results of the effect of contract binding on the proportion of farmland transfer areas that signed contracts with paper or terms longer than three years in the farmland transfer market. The model used a robust estimation of the least squares method for clustering at the village level. The R-squared and goodness-of-fit F-test statistics of the model estimation showed that the overall degree of fit was good, and the model explained the key variables to a high degree.

Table 6.

Influence of contract binding on the contract structure of the farmland transfer market.

Columns (11) and (12) show that contract execution and dispute resolution rates are positively related to the proportion of farmland transfer areas signed with paper contracts. Specifically, when the contract execution rate or dispute resolution rate increases by 1 percentage point, the proportion of farmland area signed with paper contracts increases by 0.460 and 0.144 percentage points, respectively. Moreover, the estimated parameters are statistically significant at the 1% and 5% levels, respectively. Columns (13) and (14) show that the contract execution and dispute resolution rates are positively related to the proportion of farmland transfer areas signed with terms of more than three years. When the contract execution or dispute resolution rates increases by 1 percentage point, the proportion of farmland areas that signed contracts with terms longer than three years increases by 0.380 and 0.175 percentage points, respectively. Moreover, the estimated parameters are statistically significant at the 1% and 10% levels, respectively.

The above analysis shows that whether the contract execution rate or dispute resolution rate is selected as the proxy variable for contract binding force, the stronger the contract binding force, the higher the proportion of farmland area with paper and long-term contracts in the transfer market. In other words, villages with strong binding contracts are more inclined to choose paper and long-term contracts. When the contract binding force is insufficient, farmers tend to choose oral contracts to transfer farmland to relatives and friends, and short-term transfers are more common. The discussion focuses on the influence of contract binding force on farmers’ contract selection, which leads to systematic differences in the contract structure in the farmland transfer market. It is worth noting that the relationship between the contracting parties, content of the transaction, rights and responsibility relationship, rights and responsibility for breach of contract, and other content clauses may also affect the contract binding force in the transfer of farmlands. The two-way relationship between the transfer parties may lead to endogeneity problems in the model. However, as the research focuses on the contract binding force formed by external protection mechanisms in farmland transfer and analyzes data at the village level, the contracting information at the farmer level is not sufficient to affect the overall contract binding force. This did not lead to serious endogeneity problems.

In summary, through theoretical analysis and empirical tests, this paper discusses the influence of social trust and legal institutions on contract binding force, as well as the influence of the contract binding force on the contract structure of the farmland market. The results show that the enhancement of social trust and legal institutions strengthens farmland transfer contract binding force, which contributes to the use of paper and long-term contracts in the farmland market. Therefore, in the context of factor marketization, improving formal and informal social institutions to enhance the contract binding force in factor trading is of great importance for standardizing farmland transfer contracts and improving market resource allocation efficiency.

5. Conclusions and Suggestions

With the development of factor marketization, the continuous transfer of rural labor breaks the traditional governance model of a society of familiar people. The decline in social trust and flaws in the construction of legal institutions affect the performance environment of rural governance, weaken the binding force of contracts, and influence farmers’ contract choices, leading to systematic differences in the contract structure of the farmland transfer market. Using survey data from 128 villages in Heilongjiang, Henan, Zhejiang, and Sichuan provinces, this paper analyzes the effects of social trust and legal institutions on contract binding force, and the effects of contract binding force on the proportion of farmland areas that choose paper and long-term contracts in the market. The results show that improvement of social trust and legal institutions can strengthen the binding force of farmland contracts. The strength of legal institutions embodied in regulation files and execution, and the social trust embodied in village neighborhood relations and loan relations, have significant positive impacts on the contractual binding force of the farmland transfer market. Second, contract binding force has a positive impact on paper contract types and long-term contracts in the farmland transfer market. Whether the contract execution rate or dispute resolution rate is selected as the proxy variable for contract binding force, the stronger the contract binding force, the higher the proportion of paper and long-term contracts in the farmland transfer market.

This study has the following policy implications. First, it promotes the establishment of legal institutions for rural social governance. On one hand, we should improve relevant laws and regulations, such as the farmland property rights system, and reasonably interpret possible conflicts of applicability in the laws and regulations. On the other hand, we should improve the notarization and arbitration institutions related to the management rights of contracted land, strengthen the service function of dispute coordination, improve execution efficiency, and reduce the cost of recovery. This will protect and safeguard the legitimate rights and interests of farmers effectively. Simultaneously, strengthening publicity and education on farmland laws and policies would strengthen farmers’ awareness of property rights. Second, regional differences in rural social changes should be fully understood, and rural governance should be guided in accordance with local conditions. Regardless of the informal system, represented by morals, conventions, customs, village rules, and people’s conventions, or the formal system, represented by laws and regulations, both represent social norms that exist to deal with the tension between people’s interests and resources. All of these are important factors affecting the allocation of resources in the farmland transfer market. With the development of factor marketization, the weakening of the informal system will become an inevitable trend, and the formal system will gradually play a leading role in rural governance. However, owing to the differences and imbalances in development speed between regions, it is necessary to adjust the relationship between formal and informal systems in rural governance according to local conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C. and Y.G.; methodology, Y.G.; software, Y.G. and M.C.; validation, M.C., Y.G., and Z.X.; formal analysis, M.C.; investigation, Z.X.; resources, Z.X.; data curation, Z.X.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.; writing—review and editing, M.C.; visualization, M.C.; supervision, Z.X.; project administration, M.C. and Z.X.; funding acquisition, M.C., Y.G., and Z.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 72203079], the Major Program of the National Social Science Foundation China [grant number 20&ZD094], and the Natural Science Foundation of Colleges in Jiangsu Province [grant number 22KJB630003].

Data Availability Statement

The data that were used are confidential and thus unavailable.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge that the funding for this research was provided by the National Social Science Foundation of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1. | Regarding the contract form, an oral contract refers to an oral agreement in the farmland transfer, and a written contract is defined as a paper contract. Regarding the contract term, a short-term contract is defined as a farmland transfer term of less than three years, and a long-term contract is considered a transfer term of more than three years. |

| 2. | The sample of cities was as follows: Ning ’an, Tangyuan, Zhaodong, and Longjiang are in Heilongjiang province; Xiayi, Anyang, Xiping, and Xuchang are in Henan province; Shengzhou, Wuyi, Wenling, and Xiuzhou are in Zhejiang province; and Zhongjiang, Nanbu, Yanjiang, and Linshui are in Sichuan province. |

References

- Qian, Z.; Ji, X. Farmland transfer status and policy implications in rural China. Manag. World 2016, 2, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Luo, B.; Geng, P.; Zhu, M. Market-oriented land rentals in the less-developed regions of China. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2021, 28, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Han, H.; Ying, S. Reputation effect on contract choice and self-enforcement: A case study of farmland transfer in China. Land 2022, 11, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slangen, L.; Polman, N. Land lease contracts: Properties and the value of bundles of property rights. NJAS-Wagen J. Life Sci. 2008, 4, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Luo, B. How contract duration be determined? Based on empirical analysis from dimensions of asset specificity. China Rur. Obs. 2014, 4, 42–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Jiang, T.; Guo, L.; Gan, L. Emerging rental markets and farmers’ behavior in agricultural land in China: Evidence from rural household survey in 29 provinces from 2013 to 2015. Manag. World 2016, 6, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M. The practical mechanism of agricultural scale management from the perspective of embedding. Iss. Agric. Econ. 2022, 1, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B. Hypothesis of short-term contract and empty contract: Based on empirical evidence of agricultural land lease. Res. Financ. Econ. Iss. 2017, 1, 10–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Huang, J.; Rozelle, S. Rental markets for cultivated land and agricultural investments in China. Agric. Econ. 2016, 43, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Huang, J.; Rozelle, S.; Xu, Z. The development of China’s farmland transfer market and its impact on farmers’ investment. Economics 2011, 4, 1499–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xu, Z. Market development of farmland transfer, resource endowment and farmland scale management development. Chin. Rural Econ. 2021, 6, 60–75. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Cui, M.; Xu, Z. Effect of spatial characteristics of farmland plots on transfer patterns in China: A supply and demand perspective. Land 2023, 12, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Chen, C.; Cao, G.; Yi, Z. Spatial-temporal characteristics and influential factors decomposition of farmland transfer in China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2017, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, P. The effect of different farmland transfer patterns on household agricultural productivity based on surveys of four counties in Jiangsu Province. Resour. Sci. 2017, 39, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.; Hazell, P. Land tenure security and agricultural performance in Africa: Overview of research methodology. Rev. Nuovo Cimento 2013, 10, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangliang, Y.; Junhui, W. A new round of farmland ownership, farmland transfer and scale management: Evidence from CHFS. Economics 2022, 22, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiangyi, L. How does the confirmation of farmland rights affect the transfer of farmland? J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law. 2020, 2, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawry, S.; Samii, C.; Hall, R.; Leopold, A.; Hornby, D.; Mtero, F. The impact of land property rights interventions on investment and agricultural productivity in developing countries. J. Dev. Eff. 2016, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Hong, M.; Liu, H. Farmland transfer contract selection from the perspective of differential pattern. J. Northwest. Agric. For. Sci. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.). 2015, 4, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Luo, B.; He, Q. Does Land Rent between Acquaintances Deviate from the Reference Point? Evidence from Rural China. China World Econ. 2020, 28, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Zhuo, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, G. Exploration of informal farmland leasing mode: A case study of Huang Village in China. Land 2022, 11, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Cui, M. Does the stability of land property rights Increase farmers’ long-term investment in agriculture? Based on the perspective of contract binding. China Rur. Obs. 2021, 2, 42–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qian, L.; Hong, M. Why Does Farmland Transfer Contract Trend to be Verbal, Short-term and Unpaid? Empirical Evidence from Perspective of Control Right Preference. Financ. Trade Res. 2018, 29, 48–59. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Van Gelder, J.L. What tenure security? The case for a tripartite view. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, S.J.; Hart, O.D. The costs and benefits of ownership: A theory of vertical and lateral integration. J. Pol. Econ. 1986, 94, 691–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, O.; Moore, J. Property rights and the nature of the firm. J. Pol. Econ. 1990, 98, 1119–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yiping, Z.; Xiang, L.; Lin, W. Implementation effect of land transfer performance guarantee insurance and village differences. Iss. Agric. Econ. 2023, 2, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. Agricultural land transfer dispute: Default mechanism and empirical study. J. China Agric. Univ. 2020, 25, 216–230. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Wang, Y. Contract execution efficiency and regional export performance: Empirical analysis based on industry characteristics. Economics 2010, 9, 1007–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X. Rural Chinese Fertility System; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yinrong, C.; Yanqing, Q.; Qingying, Z. Study on the impact of social capital on agricultural land transfer decision: Based on 1017 questionnaires in Hubei Province. Land 2023, 12, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. Operation and construction of the form system of contract of agricultural land transfer—From the perspective of legal sociology. J. China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2009, 4, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huo, X. Impact of Farmland Rental Contract Disputes on Farmland Rental Market Participation. Land 2022, 11, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Ding, W. The Governance of Land Transfer Dispute: From the “Fragmentation” to “Integrity”-Based on the Field Investigation in SY County of Jiangsu Province. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 30, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Analysis on the important role of rule of law in the construction of social trust. Leg. Syst. Soc. 2017, 16, 127–128. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, H. The ‘credibility thesis’ and its application to property rights: (In)Secure land tenure, conflict and social welfare in China. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Differential governance, government intervention and contract selection of farmland management rights: Theoretical framework and empirical evidence. J. Manag. 2020, 33, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhong, F. Paid vs. free: The value added of farmland and the choice of farmers’ subcontract method under the risk of property rights. Manag. World 2015, 11, 87–94+105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).