Abstract

This article presents a stakeholders’ mapping exercise in 2017 and 2018 in the Oyapock watershed. Ninety-two maps were obtained covering almost the entire watershed. Results show that roads are becoming a more significant spatial reference to people, apart from the population minority living along the river. This latter polarizes itself into Brazilian colonization down and midstream, legal farmers on the Brazilian side, illegal gold diggers on the French Guiana side, and an Amerindian demographic growth upstream, both at the expense of the historical Saramaka/Creole area. Recent roads sticking each bank of the Oyapock River to their hinterland, Brazil, and France, respectively, like rubber bands, are separating them slowly, despite the bridge, primarily useless for now.

1. Introduction

The Oyapock watershed is still a common living area for both banks. Until the arrival and implementation of infrastructures marking their possessions by the Brazilian (2200 km) and French (7100 km) metropoles, the two banks of the river were quite similar [1,2,3]. From the beginning of the 20th century, France and Brazil gradually established their footprints and, as highlighted by [4,5,6], the watershed then became twofold: remaining a living basin until the 2000s in the upstream and mostly Amerindian hinterland, which was, it became downstream an interface for exchanges between cultures that gradually differentiated themselves. Numerous studies and long-term observation of this basin, in conjunction with the observation of Amerindian populations on both banks and the establishment of the two Amazonian Parks (the Brazilian PNMT, Parque Nacional Montanhas did Tumucumaque in 2002, and the French PAG, Parc Amazonien de Guyane: [7] in 2007), has allowed a better understanding of the Oyapock social dynamics. The construction of the Oyapock River transfrontier bridge is of little use even if it has been open to traffic since 2017. Finally, a substantial French fund was dedicated to studying the overall watershed dynamics, questioning the importance of the bridge opening under the supervision of the CNRS Human-Environment Observatory (Observatoire Homme-Milieu—OHM) Oyapock.

In this article, we propose to spatially describe the Oyapock territory watershed thanks to the perception of its inhabitants. The aim is to understand, in a way that is both holistic in terms of themes and global in spatial terms, how human communities describe this territory and its components, which they consider necessary and sufficient to characterise it, as well as the places where they live and the resources that enable them to improve their quality of life. The approach presented responds to the notion of populist legitimacy [8], as opposed to the sole legitimacy of an outside observer, particularly of scientists working there, by proposing a hybridisation of this knowledge and a formalisation of these perceptions. Here we produce a spatial analysis of the perceptions of the local actors we met over a relatively short period. The Perception-based Regional Mapping (PBRM) methodology [9] responds to this search for an alternative viewpoint by its capacity to inventory the characteristics of a vast territory as soon as this territory is traversed and included in the Oekumen in the anthropologic sense of [10], or territory experienced and known as a humanised space. If humans are willing to talk about territory, everything could be mapped.

2. Methods and Sampling

The Perception-based regional mapping PBRM) is a social survey mapping tool for populations considered relevant in a territory. Relevant here means that they are both concerned by this territory and potentially affected by it by living there, crossing it, working around, etc.). They know of it through practices, doing things individually and through a community and the transmission of books and local information. This tool is often described as “participatory”, but according to [11], participation here stops at collecting local information. Based on a methodology for the co-construction of shared diagnoses and the co-development of local management plans developed by [12], we have formalised a tool for collecting and combining local perceptions. The PBRM fills in many gaps in the spatialized approach to the development and territory environmental issues, which goes beyond a classic anthropological approach. Indeed, these gaps corresponded to the lack of a junction between inductive approaches from the human sciences and technology, and deductive approaches from the biophysical sciences and are inevitable in such qualitative elaborations:

- The first weakness concerns geographical positioning: integrating mental maps a posteriori, formalising a space without an initial connection to a cartographic base, into a geographical system is challenging [13,14]. Without this reference, the information cannot be understood without the local organisation’s prior knowledge. Nor can it be confronted with external sources, which is the only way to test a method.

- The second weakness concerns the scale: mental maps, like maps derived from field measurements, rarely go beyond the village territory unless there is a substantial budget. They, therefore, tend to be thematically restricted to the local context and resources and do not capture regional organisation and dynamics [15].

- The third weakness is disciplinary: regional tools are generally based on spatialisable variables, most often biophysical, whereas local tools are largely socio-anthropological (only the linguistics aspect of place names avoid this division). Faced with the large number of unknown local variables to be studied, several public operators in rural development, public services and local authorities (for instance, the French counterpart, the army and gendarmerie, the Forest National Office of French Guiana local authorities, but also NGOs such as Greenpeace and others) rely primarily on external data sources, such as remote sensing, with the Amazonian Park of French Guiana (PAG) being an exception. These sources give an impression of reliability: they are accurate, frequently updated, and spatially homogenous, but they are only panoptic variables that can be observed by remote sensing. However, the fact that they are visible no longer justifies their real weight regarding the issues in the concerned territory. On the other hand, local development actors (NGOs, associations, etc.) working locally tend to rely on their own, mainly qualitative, information. In both cases, the ideological context of these institutions and the academic and social background of their agents and donors also influence the points of view [8].

- Finally, the last weakness is linked to the information itself: any local dynamic only comes to the attention of a survey from the outside: a dynamic is discovered through contact and is informed by collecting data and information [16], allowing confirmation or refutation. It is never the collection of data that provides information on the variable at the origin of the data! The PBRM is thus a detector of ‘weak’ signals by the simple fact that certain dynamics are identified when they could not be otherwise. The signals identified are not necessarily crucial but should be explored in the next subsequent investigation.

The method is quite simple in its structure but requires some attention in its implementation:

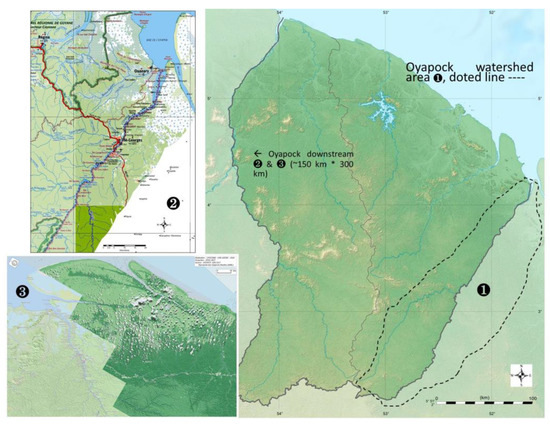

- We work based on a map incoming, in this case from three maps of the Oyapock watershed provided by the cartographic service of the UMR LEEISA CNRS research laboratory, which constitute a background on which we superpose a layer for each interview (Figure 1). The map is printed and treated to resist meteorological risks (lamination or fabric protection). It is made up to cover the targeted territory to “de-localise” the territory, i.e., not to restrict the interview to the local dynamics alone, seen only on a small map. For this map to be readable by the inhabitants, the indispensable toponymical database drawn up jointly by the UMR LEEISA CNRS and the Amazonian Park of French Guyana (localities, roads, rivers, rapids, rocks, confluences, etc.) was included [17], which is more important than the precision of the rivers meanders, for example, because it is by citing and locating them that the interviewees will be able to situate themselves;

Figure 1. Overview of the background maps used for the different PBRM surveys.

Figure 1. Overview of the background maps used for the different PBRM surveys. - As far as possible, the interview sampling should seek a diversity of profiles (status, origin, cultural capital, gender, age, professional world, etc.) and representativeness (particularly gender, which is almost systematically biased). Houses and social places should be favoured, but in practice, on both sides of the river Oyapock, they are not very frequented during the day, or it is socially difficult to ring the bell, which means that these interviews should be attempted in the early evening. The exceptions are restaurants at midday and, of course, schools and universities throughout the day. Geographical representativeness implies moving around during the survey campaign, preferably with equal time for each survey base (from city to isolated house, far/near road, river, Brazil versus France, etc.). Refusals to be surveyed are numerous: they represent 50% of the requests and increase for people in full activity (e.g., shopkeepers, representatives, and elected officials). These biases are very difficult to reduce.

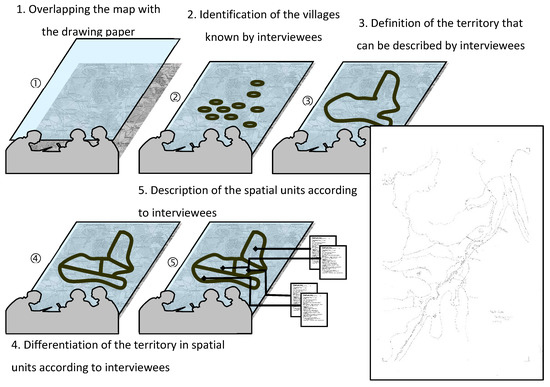

- Mapping is preferably carried out by interviewing two people simultaneously from different fields of knowledge and, if possible, who do not know each other, to limit status conflicts or preponderance based on gender, age, or other social issues. The results depend very strongly on their willingness to participate in the discussion and on the ability of the interviewers to limit the influence of social dominance relations [18,19]. Placing this knowledge on a map is undoubtedly an obligation for later use and constitutes the least harmful form of social domination, referring to the game at school. The methodology is summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Perception-based regional mapping (PBRM) methodology and example of the resulting map.

Figure 2. Perception-based regional mapping (PBRM) methodology and example of the resulting map. - How the interview was conducted:

- a.

- It begins by placing the layer on the map and giving pencils to the two interviewees. The first step is to identify the territory the two interviewees know by circling the villages they recognise and can describe. Listing the villages and place names verbally avoids fixing the interviewee’s mind on a cartographic representation, as some interviewees visualise the villages and classify them according to the criteria, they mention but not clearly their position. By facilitating the link to the map in this way, we allow the interviewee to focus on their classification and avoid asking questions about the interviewees’ unknown areas, and they will then only talk about their respective areas of knowledge.

- b.

- The second step consists in dividing the territory: a single question is asked, intentionally “simplistic”, i.e., with the least possible bias: “Is it the same everywhere?” suggesting that the differences to be sought are spatial and spatialisable. “In relation to what?” object most interviewees. “We don’t know. You’re the one who knows this country”, leaving it to the interviewee to define this criterion, which could be anything. Only the interviewees describe the differentiation criteria without any suggestion from the interviewer. The origin of these criteria is noted, in addition to the discussions and reactions between the interviewees. The criteria are then mapped according to their values (‘here a lot’, ‘there a little’) by drawing sets, individualised spatial units, identified by these criteria and homogeneous in relation to them, called HSU (Homogeneous Spatial Unit). Each HSU is drawn topologically: for a given criterion, to separate the area where a site includes this criterion and the area where a site excludes it, the border right in the middle is drawn without further complexity.

- c.

- The third step consists of a “factual” description of each HSU: local infrastructure (markets, religious buildings, dispensaries and hospitals, schools), main economic activities and trade flows between it and other HSUs, the dynamics population living in this unit (settlement and emigration).

- The data set, consisting of about 100 interviews spatialized for the Oyapock watershed area, is digitized and georeferenced in a Geographic Information System (GIS). The final step combines the maps obtained, i.e., intersecting the HSU polygons and combining the criteria and their declinations. We then obtained a single map with several thousand polygons, each with information weighted by the number of people who spoke about it in their respective maps. For example, 37 people spoke about land use during the interview. If, for a distant area, four people described this place, 3 of them as a place of ‘hunting’ and only one spoke of ‘slash-and-burn’, then the final polygon will indicate for Land use hunting3+ slash-and-burn1.

- The significant difficulty of this formalization is the management of semantic differences, in addition to the syntactic approximations of each HSU category which can, in some cases, be managed by formalization or even automatization. However, one of the advantages of this method is that the syntactic variations range around the same terms and is stored in memory.

In the framework of the FEZOADA research project of the Human-Environment Observatory (OHM) Oyapock, we applied this three-step zoning methodology for logistical reasons: A first series of surveys at the end of 2017 took place in St-Georges de l’Oyapock, then in the hamlets of Tampak, Trois-Palétuviers and finally in Ouanary municipality near the Oyapock watershed outlet.

- A second series took place in June 2018 in and around the French municipality of Camopi, and its Brazilian counterpart Villa Brasil on the other bank of the Oyapock River. We were unable to include the hamlet of Trois-Sauts, upriver 150 km away.

- Finally, work continued in July 2018 in and around the Brazilian city of Oiapoque in collaboration with UNIFAP, the Federal University of Amapá, with different populations, including some members of the Palikur and Galibi Amerindian population.

3. Results and Analysis

The results, as with any survey, present representativeness biases presented in Table 1: officials (from both countries, teachers, but also medical personnel, gendarmes, and military personnel, etc.) are over-represented, and the age and gender factors are biased towards older men. This limitation of the study, indeed a very common one in social surveys, is, however, simply recalled here, the method having been extensively explained, discussed, and subjected to reflexivity in several previous articles [9,20,21].

Table 1.

Respondent’s representation by age, occupation, and gender in the PBRM Oyapock watershed. This table containing the distribution of interviewed according to their main activity (in percent %). Nota: Non-public officier’ lives are intrinsically multi-active. The activity is the most important but not necessarily the only activity of interviewees. * Also applies to professional training. ** Unemployed and retired. *** and army pirogue driver.

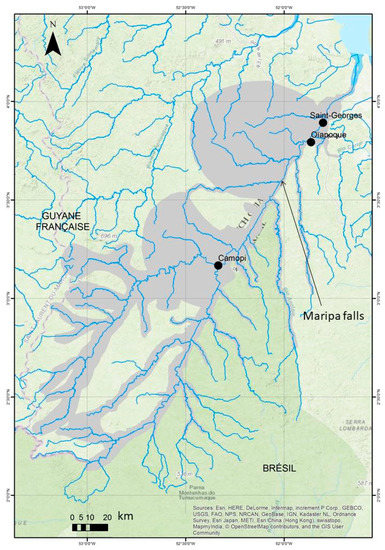

In Figure 3, the PBRM spatial coverage is significant (26,000 km2, i.e., the equivalent of 97% of the watershed) in 90 man-days, admittedly more or less intensively covered according to the number of people knowing the place. Nevertheless, certain hollow spaces appear and correspond to the hollows of habitation, places of passage only, to be investigated during future surveys if possible. Thus, some areas are known to only two or even one interviewee. Nevertheless, ten criteria were identified, of which we present the two most frequently reported.

Figure 3.

Total coverage assessed by all the PBRM mappings in the Oyapock watershed.

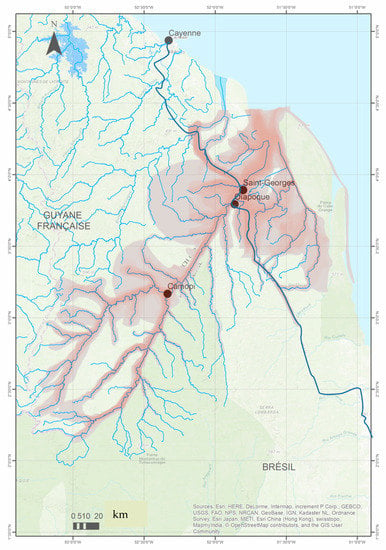

Figure 4 shows the territory knowledge density described by the sum of the PBRMs: the redder an area is, the more maps represent the area. This figure illustrates the polarisation around the road and river axes, with the known rural areas forming a halo around the three centres of Oiapoque, St Georges and Camopi and remaining the preserve of hunters, fishermen and farmers. The interviewees, both Brazilian and Guyanese, who mentioned the road as the main axis, were mostly urban: officials, traders, or transporters, but also young people from the two towns recently established locally. Those who see the river and its tributaries as the main axis are rural (farmers, pirogue drivers, hunters, etc.) and almost exclusively Amerindians, Creoles or Saramakas. In short, they are perceived as the most ancient people in the area. The territory described here is more extensive around the axes as they hunt and farm. Important point: The Palikur ethnic group area in the north of the Oiapoque-Macapá road and the colonisation area to the south are thus “countries”, the only rural areas covering a territory that is not only fluvial but has been built around coastal rivers. The Wayãpi-Teko ethnic space is also a country. Personal anchorage and representation of the territory are thus intrinsically linked.

Figure 4.

Total coverage assessed by all the PBRM mappings in the Oyapock watershed, showing the knowledge density.

Several dynamics can thus be observed:

- The road at the expense of the river: For both sides of the border, the road is becoming part of the inhabitants’ customs as they are less and less “from the river” and “from the country” and more and more urban, coming from elsewhere. St-Georges and its Brazilian twin town of Oiapoque have become the link between the Cayenne-Macapá axis and the Oyapock River, from Ouanary to Trois-Sauts village (Boudoux d’Hautefeuille, 2014). But outside this axis, the rivers and their tributaries are the routes of transit, entry, and territory knowledge. To get around, alternating roads and rivers is undoubtedly a shared practice, but it is now much easier to be connected to regional capitals than to the distant banks of the river. Therefore, this geographical differentiation between two worlds, road, and river, is also generational and cultural. The Maripa Falls divide appears (Figure 3): the ‘potato-oikumene‘ of this basin, a communication, life, and food route, is populated downstream and on both banks by Brazilians, shifting the majority of the population towards an urban and road lifestyle, and upstream by Amerindians thanks to significant population growth (up to 4 children per woman) [22]. However, although the young people of Camopi circulate, they explore less than their elders, hesitating to organize expeditions lasting several days or even weeks on the tributaries of the Camopi [23,24,25].

- Mines and slash-and-burn cultivation: the settlement was never strong in French Guyana, and certain traces (Regina, Maripa Falls) attest to failed attempts to set up export agriculture. The Creole or Saramaka farms suffer from most of their operators’ advanced age. There is no longer any installation of young farmers on the French side of the Oyapock River, supported by restrictive forestry legislation [26].

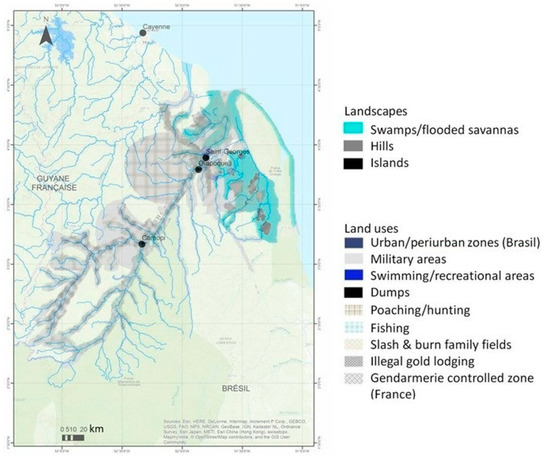

- Farms along the BR 156 road could be oriented towards supplying Oiapoque and St-Georges [27,28]. However, this leaves livestock and cash crops on the Brazilian side due to low wage costs and illegal gold panning, whose territory is defined by the area of control authorised by the French gendarmerie (Figure 5).

Figure 5. PBRM mapping of predominant landscapes and land uses in the Oyapock watershed between Brazil and French Guiana.

Figure 5. PBRM mapping of predominant landscapes and land uses in the Oyapock watershed between Brazil and French Guiana.

From then on, the slash-and-burn surfaces became family retreat areas where the grandparents lived, with food crops, primarily cassava. People come to meet, hunt and fish at weekends [29], whether in the large Palikur-Galibi-Karipuna swamp area on the downstream side of Brazil [30,31] or in the Wayãpi-Teko countries on the upstream side of Guyana [24,25], each of which is protected by a national park.

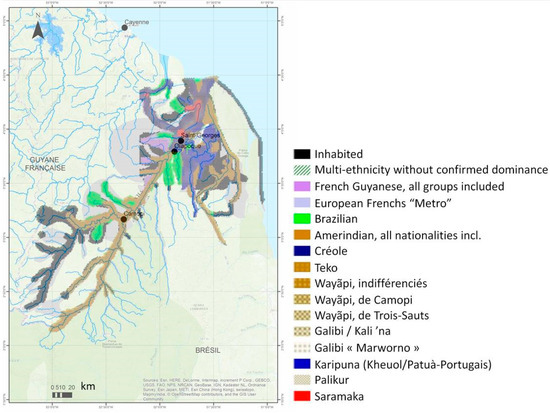

- Ethnic groups: this notion is a structuring criterion for the interviewees’ discourse (22.4% of the interviews). Figure 6 shows this spatial distribution and dynamics:

Figure 6. Results regarding ethnicity and/or nationality dominance on the territories covered by the PBRM methodology over the Oyapock watershed between Brazil and French Guiana.

Figure 6. Results regarding ethnicity and/or nationality dominance on the territories covered by the PBRM methodology over the Oyapock watershed between Brazil and French Guiana. - Expansions Brazilian and Amerindian expansion: the space between Montabo Falls and the Sikini River, including the latter, has become a de facto quasi-Brazilian space through the continuous infiltration of garimpeiros, i.e., gold diggers and the supply bases establishment, between the “road” space described above and the upstream river space. The Sikini River is seen as too dangerous for non-garimpeiros. This infiltration is far from over and could be reactivated by the economic difficulties and political orientations that affect and will affect these territories. Amapá State, south of Oiapoque and along the BR-156 road to Macapá, is also gradually being fragmented by agricultural expansion and the regular arrival of Brazilian settlers, who are being held back by Amerindian reserves and the Cabo Orange Park on the coast. Finally, the recent demographic vigour of the various Amerindian groups has not yet been reflected in its spatial dimension, as the new generation was not yet adult in 2020.

- Mixed origins and isolated groups: the map show the dominant groups but also highlights the growing importance of mixed-race identities in the city (St Georges, Oiapoque) and the forest, such as between the shores of Camopi-Villa Brasil or Trois-Palétuviers-Yamna, where Brazilian Creole and Brazilian Amerindian couples and children are gaining in importance. These new “local identities” emergence has enabled the now well-established rapprochement of Amerindian groups among themselves (Teko and Wayãpi, Palikur, Galibi and even Patuà) but also with and among others with similar customs and practices: what is cultivated, gathered, hunted, and eaten, as well as the way it is consumed, are identifiers of how one sees oneself, of what unites. This can create a link [32] when desired, in contrast to the isolated groups that are the Saramaka remnant of Tampak or the Creole rest of Ouanary village.

Comparison with other results on this Oyapock basin focuses mainly on the actual impacts of the bridge openings. However, there is a common agreement that it has little consequences for the societies on the two banks of the river and even separating each other, through the progressively easier connexion of each bank towards its hinterland and the progressive closure of the border primarily due to the application of national regulations in a territory where informal arrangements were common [5,6,33,34,35]. Indeed, roads and new connections do modify local mobility [4,24,36,37,38,39]. Our work completes these works by showing the spatial and social differentiation between the “roads world” and the “River world”, the latter losing its emprise progressively. Furthermore, we show the intertwining between such a disparity and a still-palpable differentiation based on ethnicity, which plays a major role in defining identities. However, identity intercrossing, such as the combination of ethnicities and nationalities, are here pregnant, mainly due to the very strong inequality of statutes, infrastructures and supports one may encounter between the two borders: the “road world” insinuates itself also through the more complex identities appearing in the fading “River world”. Equivalent works reveal equivalent dynamics in other Amazon areas, such as in the Ecuadorian Amazon, where mixed identities, families and villages are building a melting pot of specific identities [9,40].

4. Conclusions

We obtained a snapshot of the perception of almost the entire Oyapock catchment area using the PBRM tool. However, it remains fragmentary because the representativeness of the interviewed sample needs to be improved, and the perceptions can be seen as biased in some respects. This analysis should be completed by a survey in Trois-Sauts village, Villa Brasil and the territories managed by Funai (Fundação Nacional do Índio) in Brazil, near Cabo Orange and Tumucumaque national parks. The results presented are a first overview of the thematic richness of local views on the different dynamics affecting this territory, whether environmental, health, socio-economic or security-related. The territory seems to be experiencing a crystallization of habits around the roads to the detriment of the river and its practitioners. When we compare the knowledge territories of the rural interviewees with those of the urban ones, those of the groups most attached to the places [41] with those belonging to the most recently arrived groups and those of the oldest interviewees with the youngest, a striking contrast emerges which, in our opinion, reflects a strong dynamic underway: the rural culture linked to the river, even if it remains prevalent, is gradually being covered by the urban culture inherent in the roads, due to the differential evolution of the demographic weight. These roads, nationalist assertions and the COVID-19 pandemic have brought each bank back to their respective hinterlands, French Guyana and Amapá, like rubber bands, depending on the intensity and recurrence of these present and future crises. The first restitution was given at the end of the 2018 surveys. Since then, the conjunction of constraints, i.e., the pandemic, the Bolsonaro regime and ideology and the budget restrictions on both sides were restricting de facto access to Brazilian and French field sites until the 2023 President Lula da Silva election. Therefore, definitive results may be transmitted only to local institutions, universities, municipalities, governments, and populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and E.M.; methodology, M.S.; software, D.K. and B.G.; validation, M.S.; formal analysis, M.S. and E.M.; investigation, C.R.C., M.S., E.M., M.J.d.S.A. and R.C.S.; resources, M.S.; data curation, C.R.C., M.S. and E.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.-E.F. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S. and E.M.; visualization, C.R.C., M.S. and E.M.; supervision, M.S.; project administration, M.S.; funding acquisition, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the LABEX DRIIHM OHM Oyapock, a research organization of CNRS (See Appendix A).

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Damien Davy, Director of the OHM Oyapock (see Appendix A) and the LEEISA laboratory—Laboratoire Ecologie, Evolution, Interactions des Systèmes amazoniens. Special thanks to Jérôme Fozzani—GIS engineer—IRD Cayenne.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The study area stretches along both banks of the Oyapock River, a natural border between French Guiana and Brazil. The human-environment observatories (OHM) are a research infrastructure of the Institute for Ecology and Environment of the CNRS. The first one was created in 2007. Today there are thirteen OHM spread across metropolitan France (6), overseas (2) and abroad (5). They study anthropized systems affected by socio-ecosystemic crises resulting from Global Change and Globalization. The OHM Oyapock is located entirely within the tropical rainforest and includes the communities of Ouanary, Saint-Georges-de l’Oyapock, Camopi on the French side, and the vast community of Oiapoque on the Brazilian side. Sparsely populated, this area is being opened up to the outside world with the recent opening of two roads that reach the river. The construction of this transfrontier river bridge should further accelerate these changes. The OHM aims to identify and monitor the key processes which will influence the human population and its environment, their interactions, and their dynamics after the construction of this bridge.

References

- Boudoux d’Hautefeuille, M. La frontière et ses échelles: Les enjeux d’un pont transfrontalier entre la Guyane française et le Brésil. Cybergeo Eur. J. Geogr. 2010, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudoux d’Hautefeuille, M. La frontière franco-brésilienne (Guyane/Amapá), un modèle hybride entre mise en marge et mise en interface. Confins 2012, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudoux d’Hautefeuille, M. La route, facteur de développement socio-économique? Une analyse des enjeux portés par les projets routiers en Guyane fraçaise. Espace Soc. 2014, 156–157, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonato, R.J. La France et le Brésil de l’Oyapock, quels enjeux bilatéraux entre développement et durabilité? Confins Rev. Fr.-Brés. Géogr./Rev. Fr.-Bras. Geogr. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F. Unidos pelo rio, separados pela ponte: Desigualdades entrelaçadas na fronteira franco-brasileira. Confins 2021, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thébaux, P.; Gramaglia, C.; Davy, D. Le pont sur l’Oyapock: Entre ouverture et fermeture. Les paradoxes d’un objet socio-technique qui lie et qui délie. Probl. d’Amerique Lat. 2022, 119120, 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Demaze, M.T. Le Parc Amazonien de Guyane Française: Un Exemple Du Difficile Compromis Entre Protection de La Nature et Développement. Cybergeo 2008, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier de Sardan, J.-P. La politique du terrain. Sur la production des données en anthropologie. Enquête 1995, 1, 71–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestripieri, N.; Saqalli, M. Assessing Health Risk Using Regional Mappings Based on Local Perceptions: A Comparative Study of Three Different Hazards. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2016, 22, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descola, P. Par-delà Nature et Culture; Gallimard: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, P. Zonage à dires d’acteurs: Des représentations spatiales pour comprendre, formaliser et décider. Le cas de Juazeiro, au Brésil. In Représentations Spatiales et Développement Territorial; Lardon, S., Maurel, P., Piveteau, V., Eds.; Hermes: Paris, France, 2001; pp. 343–357. [Google Scholar]

- Bailly, A.S. Subjective Distances and Spatial Representations. Geoforum 1986, 17, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touré, I.; Bah, A.; D’Aquino, P.; Dia, I. Savoirs experts et savoirs locaux pour la coélaboration d’outils cartographiques d’aide à la décision. Cah. Agric. 2004, 13, 546–553. [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne-Delville, P. Regards Sur Les Enquêtes et Diagnostics Participatifs: La Situation d’Enquête Comme Interface; Etude/Document de Travail GRET: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bommel, P. Définition d’un cadre Méthodologique pour la Conception de Modèles Multi-Agents Adaptés à la Gestion des Ressoureces Renouvelables. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Montpellier II-Sciences et Techniques du Languedoc, Montpellier, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pavé, A.; Fornet, G. Amazonie: Une Aventure Scientifique et Humaine du CNRS; CNRS Editions Galaade: Paris, France, 2010; ISBN 978-2-35176-115-1. [Google Scholar]

- Amelot, X. Cartographie participative pour le développement local et la gestion de l’environnement à Madagascar: Empowerment, impérialisme numérique ou illusion participative? L’Inf. Géogr. 2013, 77, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guibet-Lafaye, C. La domination sociale dans le contexte contemporain. Rech. Sociol. Anthropol. 2014, 45, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqalli, M.; Caron, P.; Defourny, P.; Issaka, A. The PBRM (Perception-Based Regional Mapping): A Spatial Method to Support Regional Development Initiatives. Appl. Geogr. 2009, 29, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqalli, M.; Maestripieri, N.; Jourdren, M.; Saenz, M.; Maire, E. Spatialiser un risque environnemental via les perceptions locales: Une démarche, trois terrains (Equateur, Tunisie, Laos). In Pathologies Environnementales—Identifier, Comprendre, Agir; CNRS, Editions.77; Gaille, M., Ed.; CNRS: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Toss, X. Évolutions Démographiques et Stratégies Matrimoniales chez les Teko de Camopi. Master’s Thesis, Université de Guyane, Cayenne, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grenand, F.; Grenand, P. Les amérindiens de Guyane française aujourd’hui: Éléments de compréhension. J. Soc. Am. 1979, 66, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, D.; Tritsch, I.; Grenand, P. Construction et restructuration territoriale chez les Wayãpi et Teko de la commune de Camopi, Guyane française. Confins Rev. Fr.-Brés. Géogr. Rev. Fr.-Bras. Geogr. 2012, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritsch, I.; Gond, V.; Oszwald, J.; Davy, D.; Grenand, P. Dynamiques territoriales des Amérindiens wayãpi et teko du moyen Oyapock, Camopi, Guyane française. Bois Forêts Trop. 2012, 311, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sévelin-Radiguet, P. Usages et gestion du domaine forestier de Regina/Saint-Georges. Confins Rev. Fr.-Brés. Géogr./Rev. Fr.-Bras. Geogr. 2012, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchansia, K. L’agriculture à Saint-Georges-de-l’Oyapock: Bilan et perspectives. Confins Rev. Fr.-Brés. Géogr./Rev. Fr.-Bras. Geogr. 2012, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurença, M.-F. Les petits exploitants agricoles et l’État brésilien sur la frontière avec la Guyane française. Confins Rev. Fr.-Brés. Géogr./Rev. Fr.-Bras. Geogr. 2012, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard-Hansen, C.; Davy, D.; Longin, G.; Gaillard, L.; Renoux, F.; Grenand, P.; Rinaldo, R. Hunting in French Guiana Across Time, Space and Livelihoods. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, L.B. Povos Indígenas do Baixo Oiapoque: O Encontro das Águas, o Encruzo dos Saberes e a Arte de Viver; Iepé, Museu do índio, Eds.; Museu do índio: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2009; ISBN 978-85-98046-07-5. [Google Scholar]

- Crespi, B.; Laval, P.; Sabinot, C. La communauté de pêcheurs de Taperebá (Amapá-Brésil) face à la création du Parc national du Cabo Orange. Espace Popul. Soc. 2014, 156–157, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulain, J.-P. Sociologie de l’Alimentation; Quadrige; Presse Universitaire de France: Paris, France, 2002; ISBN 978-2-13-061940-6. [Google Scholar]

- Granger, S.; Silva, G.D.V. Enjeux transfrontaliers en période de pandémie de la COVID-19: Le cas de la circulation sur l’Oyapock entre Guyane française et Brésil. Confins 2021, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letniowska-Swiat, S.; Morel, V. Le bas-Oyapock: Un fleuve, une frontière, des frontières? Confins 2021, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F. The Oyapock River Bridge as a one-way street: (un) bridgeable inequalities in Saint-Georges (French Guiana) and Oiapoque (Brazil). In Twin Cities across Five Continents; Mikhailova, E., Garrand, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; Volume 17, pp. 223–234. [Google Scholar]

- Boudoux d’Hautefeuille, M. The Road Network as a Factor in Socioeconomic Development: An Analysis of the Challenges Raised by Road Projects in French Guiana. Espaces Soc. 2014, 156–157, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Figueiredo Azze, C. A Production of Alterity: The Wayãpi of the Upper Oyapock and Isolated Groups. Master’s Thesis, University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Cardiff, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, F. Crisscrossing the Oyapock River: Entangled histories and fluid identities in the French-Brazilian Borderland. In Migrants, Refugees, and Asylum Seekers in Latin America; Rein, R., Rinke, S., Sheinin, D.M.K., Eds.; Brill: London, UK, 2020; Volume 10, pp. 217–241. [Google Scholar]

- Tritsch, I.; Marmoex, C.; Davy, D.; Thibaut, B.; Gond, V. Towards a Revival of Indigenous Mobility in French Guiana? Contemporary Transformations of the Wayãpi and Teko Territories. Bull. Lat. Am. Res. 2015, 34, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqalli, M.; Béguet, E.; Maestripieri, N.; de Garine, E. “Somos Amazonia”, a new inter-indigenous identity in Ecuadorian Amazonia: Beyond a tacit Jus aplidia of ecological origin? Perspect. Geogr. 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debenedetti, A. Le concept d’attachement au lieu: État de l’art et voies de recherche dans le contexte du lieu de loisirs. Manag. Avenir 2005, 5, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).