1. Introduction

Urban restructuring has become a significant topic worldwide. Different urbanization development and city reconstruction stages require different methods, and developed countries reach high urbanization levels at an early stage. Generally, cities in developed countries face problems such as municipal government bankruptcy, urban population decrease, urban economic decline, industrial iteration, and environmental pollution [

1]. The main motive of urban spatial reconstruction is to avoid urban recession and maintain the sustainable growth of the urban economy [

2]. Cities adopt urban spatial reconstruction and urban government reconstruction to manage those problems [

3]. In Western and Northern Europe, some developed countries have adopted voluntary or compulsory merging to restructure urban areas, thereby reducing the degree of fragmentation of local governments and improving the economies of scale of public service supply [

4,

5,

6,

7]. However, in countries such as those in Africa and Southeast Asia, dividing administrative regions and redrawing administrative boundaries have become important ways of promoting urbanization development and meeting heterogeneous needs for public services [

8,

9,

10]. In the United States, Canada, and Australia, urban administrative regions are frequently split and merged, and they adjust dynamically with the stage of urbanization development [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Restructuring administrative divisions is an important measure used to adapt to the stages of urbanization. The rapid urbanization in developing countries makes it necessary to adjust administrative divisions and develop rational plans and designs for urban spaces to meet the needs of urban populations [

15].

Since China is the largest developing country in the world, its central government projects power into spaces through its administrative division management system. China’s urbanization is carried out against the backdrop of economic and social transformation, globalization, and informatization. Compared with developed countries, the organizational form and power structure of the Chinese government mean that the reconstruction of urban space in China is dominated by the strong administrative power of the government; this is the most important feature of China’s urbanization. Strong evidence for this can be seen in the fact that the adjustment of urban administrative divisions is frequent in China, whereas the reorganization of urban boundaries is rare in developed countries. However, this type of adjustment in China has effectively promoted urban development and economic growth. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the influence path of urban administrative division adjustment on urban spatial optimization in China.

Specifically, administrative boundaries have a strong attribute of power in China. By the end of 2022, China’s urbanization rate had reached 65.22% [

16], reflecting the country’s transition period of transforming urban space to promote economic and social development. Its central cities have now entered a new stage of development—from incremental expansion to inventory optimization [

17].

Since 1978, China’s central cities have generally reorganized their spaces by changing boundaries to meet urban development needs. As an important part of urban administrative division adjustment, district boundary reorganization promotes urban development from extensive regional expansion to refined spatial production, thus becoming the choice of many central cities in recent years. For example, in 2010, Beijing merged the Dongcheng and Chongwen districts into the new Dongcheng District and the Xicheng and Xuanwu districts into the new Xicheng District. Shanghai merged the Nanhui District and Pudong New Area into the new Pudong New Area in 2009, the Huangpu District of Luwan District into the new Huangpu District in 2011, and the Jing’an and Zhabei districts into the new Jing’an District in 2015. In 2014, Guangzhou merged the Huangpu and Luogang districts into the new Huangpu District. Thus, the research questions are as follows: How can urban stock space be optimized and the urban governance structure be reorganized? That is, how does the change in urban physical space boundaries shape the relationship between different levels of government and then affect the governance structure of the city? At the same time, what impact will the change of governance structure bring to urban space development? In this process, the population and resources are diverted to the outer urban areas, relieving the pressure on the urban center, making the urban spatial layout more reasonable, and promoting the development of urban suburbs and rural areas. To answer these questions, we must study the reorganization of regional boundaries and summarize the experience of urban spatial reconstruction in China.

The theories of scalar reorganization and regional reconstruction consider both physical and social space, having strong explanatory power for the changes in urban physical space (region) and social relations in space (scale) brought about by the reform of administrative divisions. This paper uses the theoretical tools of scalar and regional reorganization and takes Hangzhou as a case study to conduct a detailed analysis of the logic of central city district reorganization in China and its ability to optimize stock space (physical space) and reconstruct the governance structure (social space).

2. Theoretical Basis and Dimensions for Analysis

2.1. Theoretical Basis

The concept of scale comes from geography. In the globalized world, geographical space increasingly demonstrates the characteristics of “flowing space”: fluidity and plasticity [

18,

19]. We can extend the concept of scale to measure differentiations in the geographical landscape, including physical spaces and social relationships in geographical spaces [

20,

21]. Scale theory focuses on the shift of power and control between different geographical scales and the rearrangement of institutions and changes in governance. Scalar reorganization refers to changes in and transfer of the organizational mode, with scale characteristics such as rank, scale, relationship, and power. Scalar reorganization involves “rescaling” the power structure, institutional arrangements, policymaking, and governance modes to form new political and economic scales [

22,

23].

In this paper, region refers to the space occupied by a specific subject. Harvey argued that capital must be attached to a specific space and that “regionalization” is capital that remains in a particular bounded space and regional organization [

24]. The regionalization of capital is not once and for all but resolves the inherent contradictions of capitalism through repeated de-regionalization and re-regionalization, collectively referred to as regional restructuring. De-regionalization means that with the emergence of “flow space” (e.g., information, capital, and commodities), social and economic relations are separated from regions and administrative boundaries become blurred or even disappear, marking the disappearance of regionalism [

25]. Re-regionalization refers to capital leaving the original regional social structure and reconstructing a region in a new political, social, and economic space. Regional restructuring starts with the regionalization of capital and circulates between de-regionalization and re-regionalization.

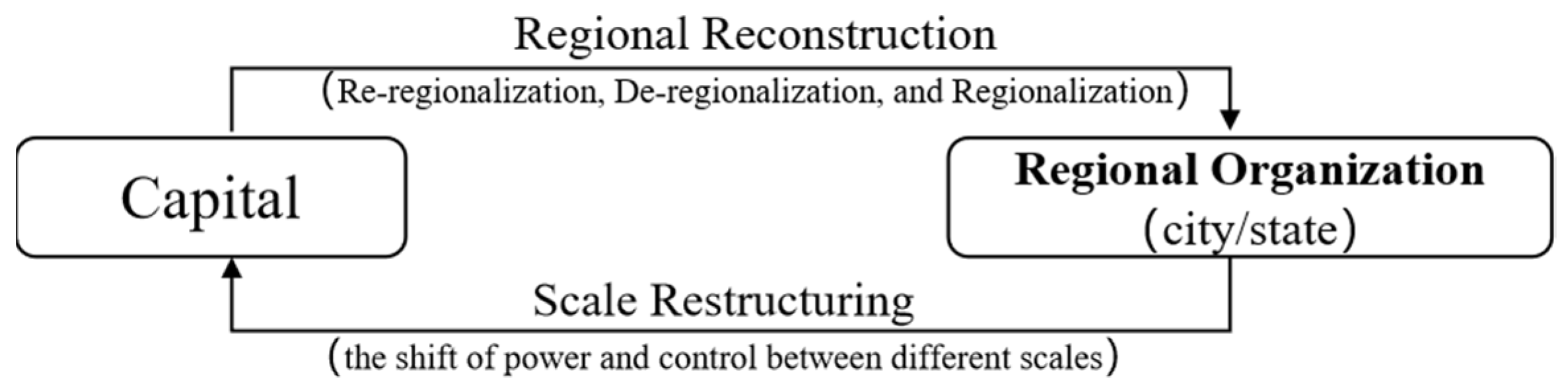

Scale and region recombination are two closely related concepts. As illustrated in

Figure 1, capital is constantly attached to new regional spaces in regional restructuring. The attachment of capital causes changes in power and control in the regional space, namely, scalar restructuring, so that it can better meet the capital’s requirements. The object of scale reconstruction is usually implemented in a specific regional space, so the regional reconstruction and scale reconstruction are closely connected, and the interaction between the two forms an integrated and two-sided process.

2.2. Dimensions for Analysis

District boundary reorganization means adjusting the administrative divisions of a district based on the municipality’s districts. It mainly involves the internal reorganization of municipal districts and the expansion of municipal and county districts [

17]. There are several types:

A large range of mergers or the separation of one or several municipal districts;

Some towns and villages formerly belonging to counties or county-level cities are classified as being under the jurisdiction of municipal districts of central cities, or there is local fine-tuning between municipal districts;

Part of the administrative region is removed from the municipal district or the surrounding counties (county-level cities) and set up as a new municipal district [

4];

Two or more municipal districts formerly belonging to prefecture-level cities are merged to form municipal districts directly under the central government.

Currently, Chinese cities with sufficient development space use options 1 or 2. The first involves a city’s large-scale reorganization and regional reconstruction, especially its central urban area, which greatly impacts the urban governance structure. The second involves fine-tuning, which has less impact on the urban governance structure. Some scholars call category 1 “strong district boundary reorganization” and category 2 “weak district boundary reorganization” [

27]. Currently, cities with insufficient urban development space struggle to set up districts by withdrawing counties (county-level cities); they are more likely to use option 3, appropriately reorganizing district boundaries to meet the needs of urban spatial development and avoid a large-scale withdrawal of counties (county-level cities). This paper will not discuss option 4 in detail since it is relatively rare, applies only to the specific period of establishing municipalities directly under the central government, and involves inter-municipal administration.

In the adjustment of urban administrative divisions, scale reorganization demonstrates that the urban government generates a new political system space and governance scale by reorganizing hierarchy, power, relationship, and scale, namely the reorganization of governance structure, focusing on the production of the political system space. Regional restructuring manifests itself as the generation of a new social economic space and regional organization by adjusting and reorganizing the boundaries of administrative divisions, which is the focus of the production of socio-economic space. Administrative division adjustment is a rigid scale adjustment tool; its occurrence period, main types, and power sources are embedded in the scale strategies adopted by countries or regions to enhance competitiveness and the corresponding scale reconstruction methods [

28].

From the perspective of scale theory, the administrative level of the spatial unit is a special scale type; this is a unique perspective from which to study the relationships among the constituent units of administrative division adjustment [

29]. Scholars use scale theory to explain changes in the administrative levels and physical spaces of Chinese cities [

30], conduct classification research on the adjustment of urban administrative divisions at the scale level [

31], and study the dynamic mechanisms and spatial influences of reforming urban administrative divisions in China [

32]. However, many studies conduct process simulation and type interpretation only at the phenomenon level [

33] and do not investigate urban administrative division reform over time and larger spatial dimensions. Furthermore, the deep logic research on the impact of administrative division reform on urban spatial production is insufficient.

The time and space of administrative division adjustment in central cities might differ under national and regional macro-strategy development; however, the logic of space production is roughly similar [

34]. Most studies have focused on first-tier cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, largely ignoring second-tier cities such as Hangzhou and Nanjing. Therefore, this study’s case study is Hangzhou, a vibrant central city in eastern China. In 2021, Hangzhou adjusted its administrative divisions by splitting large districts, merging small districts, upgrading functional districts into administrative districts, and including other forms of district boundary reorganization common in China’s central cities. Hangzhou’s administrative division adjustments provide abundant data for investigating urban space optimization through reorganizing district boundaries. The study conducted an in-depth analysis of Hangzhou’s regional boundary reorganization from the perspectives of scalar reconstruction and regional reorganization, thus adding to the literature.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Study

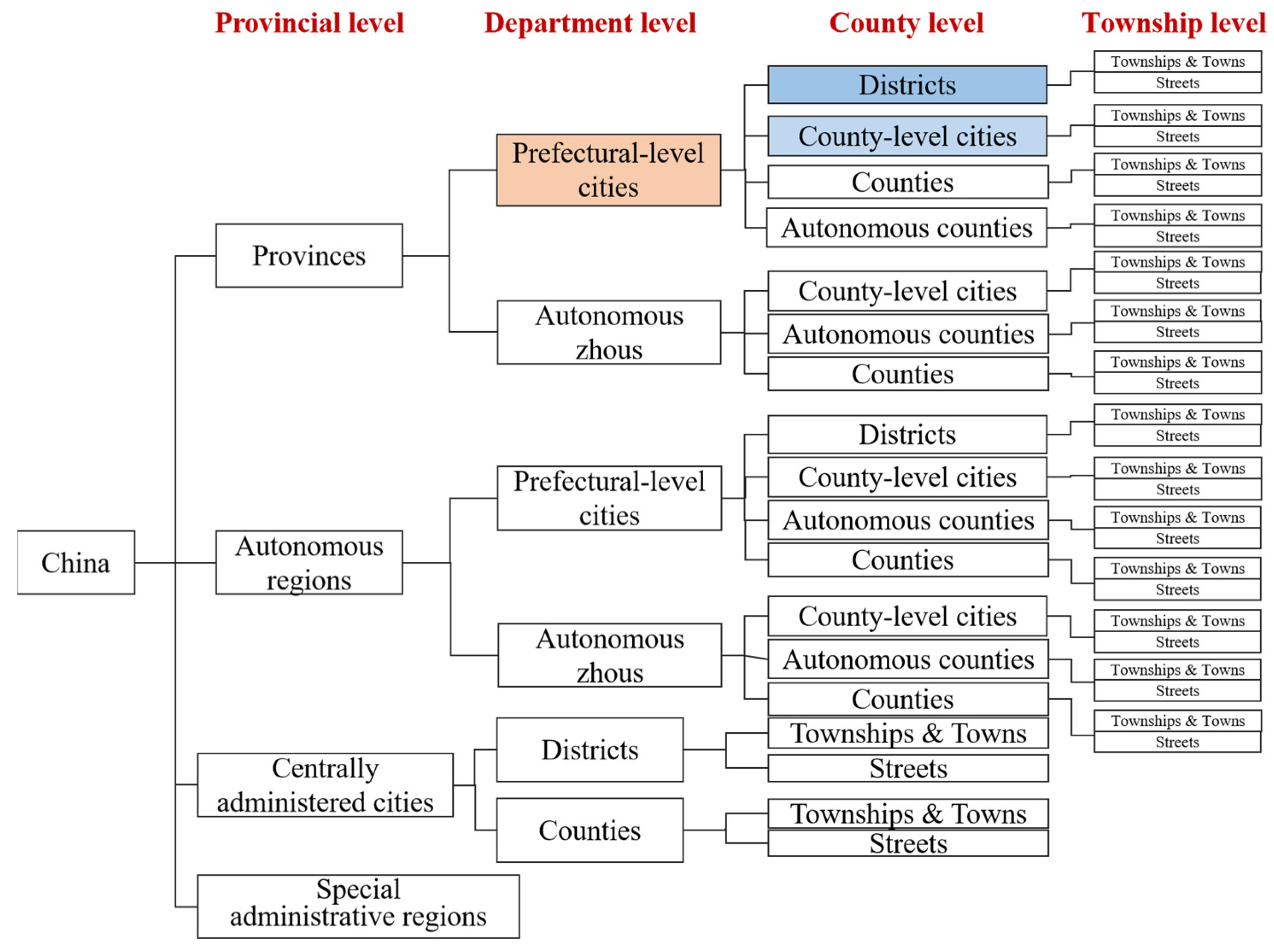

China’s local administrative regions are divided into four levels (

Figure 2). The provincial units are subdivided into provinces, autonomous regions, centrally administered cities, and special administrative regions. The prefecture-level cities (orange block) under general provinces can be subdivided into districts (dark blue block), county-level cities (light blue block), counties, and autonomous counties. Our case study, Hangzhou, is a prefecture-level city in the northern part of Zhejiang Province in eastern China, the provincial capital of Zhejiang Province, and the central city of Hangzhou Metropolitan Circle.

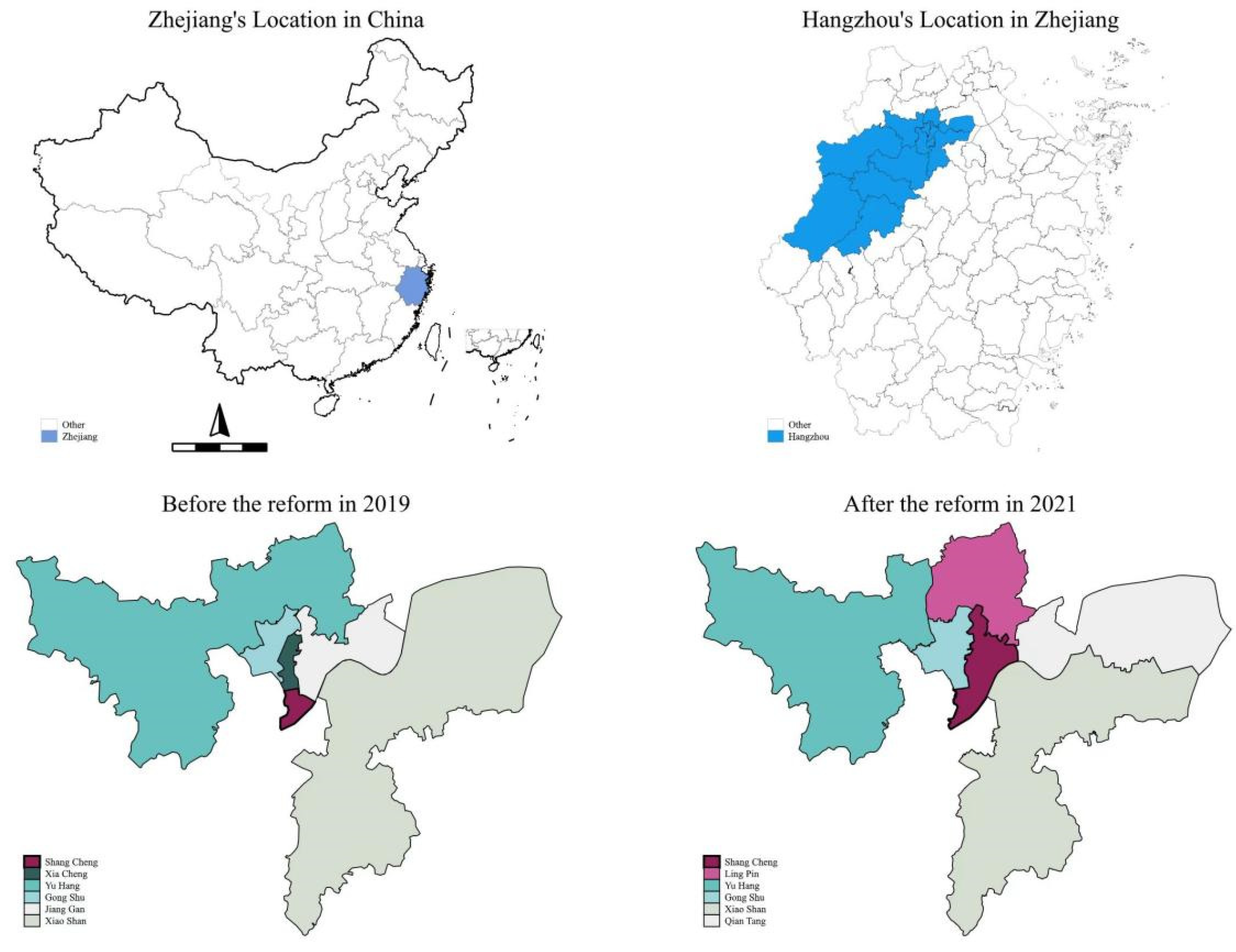

As shown in

Figure 3, Zhejiang Province is located in the eastern coastal area of China, while Hangzhou is located in the southwest of Zhejiang Province. It is the capital city and the largest city of Zhejiang Province. Hangzhou has jurisdiction over thirteen county-level administrative districts: ten districts (Shangcheng, Xiacheng, Jianggan, Gongshu, Xihu, Binjiang, Xiaoshan, Yuhang, Fuyang, and Lin’an), two counties (Tonglu and Chun’an), and one county-level city (Jiande). Since the 1990s, Hangzhou has experienced five adjustments of its administrative divisions. In 1996, three towns (Xixing, Changhe, and Puyan) were formed into a new district called Binjiang. In 2001, 2014, and 2017, four county-level cities, Xiaoshan, Yuhang Fuyang, and Lin’an, were divided into the districts of Hangzhou, and Hangzhou’s urban area expanded from 430 km

2 to 8000 km

2. The administrative division adjustment during 1996–2017 expanded the development space of the main city by creating county-level city municipal districts, laying the foundation for coordinating the urban system patterns [

35].

Chinese cities are moving from external macroscopic and regional restructuring to internal microcosmic and regional restructuring [

36]. After the four administrative division adjustments, Hangzhou became the largest city in the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration. However, the city’s structural contradictions became increasingly prominent; there was a mismatch between area and scale. Therefore, in April 2021, Hangzhou implemented a fifth administrative division adjustment. As shown in

Figure 3, this restructuring readjusted the district boundaries, merging the Shangcheng and Jianggan Districts to form the Shangcheng District and merging the Xiacheng and Gongshu districts to form the Gongshu District. It also split the Yuhang District into the Yuhang and Linping districts, with the Beijing–Hangzhou canal as the boundary. Finally, it upgraded the Qiantang New Area to the Qiantang District, which included the Xiasha District (once part of the Jianggan District) and Dajiangdong District (once part of the Xiaoshan District) [

37].

3.2. Research Methods: Content Analysis, Literature Review, and Interviews

This study used the case study method and data obtained from a field investigation in Hangzhou. Before and after the adjustment of administrative divisions (2020, 2021, and 2022), we traveled to Hangzhou for data collection and observation. We observed the administrative division adjustment process to collect first-hand data such as application and approval plans, risk assessment reports, approval process information, complaint and visit stability maintenance work plans, and information from public opinion solicitation forums in each municipal district of Hangzhou in 2021. From the Hangzhou City Planning Exhibition Hall, we obtained the statistical yearbook of various municipal districts of Hangzhou, newspapers and archives of Zhejiang Province and Hangzhou, overall plans of Hangzhou city, the adjustment process of administrative divisions since 1996, a history of urban development, and other materials. As shown in

Table 1, we interviewed government staff who had participated in Hangzhou’s administrative division adjustment, including representatives from the Hangzhou Municipal Government Office, Hangzhou Civil Affairs Bureau, Hangzhou Municipal Planning Bureau, and Hangzhou Municipal Public Security Bureau; and relevant staff from the Gongshu, Shangcheng, Yuhang, Linping, and Qiantang districts.

We conducted six symposia and nine in-depth interviews. Our interviews included the following questions:

What is the reason for the boundary reorganization?;

What must be done to split/merge municipal districts and upgrade functional areas into administrative districts? Who is responsible for this?;

What changes to government institutions and power distribution will occur after the change in the scale of municipal districts?;

During the ongoing transition period, the finances will still be under the direct management of Zhejiang Province, with the financial stock still belonging to Zhejiang Province and the increased part belonging to Hangzhou. What impact will the reorganization of the boundaries have on the original transitional policy?;

What impact will the reorganization bring?;

What impact will the reorganization of district boundaries have on urban planning?

4. Results of Case Analysis

4.1. Reasons for District Boundaries Reorganization in Hangzhou

There were three main reasons for the Hangzhou District boundary reorganization. First, the disparity in the municipal districts’ areas was not conducive to balanced development. The ten districts under the jurisdiction of Hangzhou differed significantly in area, population scale, and economic aggregates. Small areas such as Shangcheng and Xiacheng were only 20 km2, while the areas of the largest cities (Xiaoshan, Yuhang, Fuyang, and Lin’an) were above 1000 km2; the largest, Lin’an, had an area above 3000 km2. The central urban area was too small and the development space insufficient to meet the needs of the increasing population, industry, infrastructure, and other factors. The vast outer urban area had abundant land stock resources, hindering the balanced distribution of public services and industrial resources, and this problem needed to be resolved.

Second, the limited distribution of resources was not conducive to industrial upgrading. Among the six districts of Hangzhou, Shangcheng, Xiacheng, Jianggan, and Gongshu, the old core cities were geographically adjacent; Yuhang and Qiantang became districts in 2021. Tertiary industries had been developed to create industrial isomorphism, including trade, tourism, and manufacturing. Yuhang District had manufacturing facilities in the east and high-end scientific and technological innovation industries in the west. Xiasha Industrial Park and Dajiangdong Industrial Park in the Qiantang New District were problematic because, as one official said, “some people have no industry, while others have industry but no human resources”.

Third, the administrative barriers were not conducive to the flow of goods and services. In the mid-1990s, Hangzhou formulated the strategic “Yongjiang Development” plan to determine the city’s eastward expansion. With the city’s development, the new and old cities gradually developed into a cross-administrative form that did not facilitate the integration of old and new areas. The existence of administrative barriers impeded the free flow of production factors.

Scale politics describes “the struggle for the absolute control of local, regional, and spatial control” in urban geography and regional governance studies [

21]. The adjustment of urban administrative divisions is a scale political event dominated by the central city government and characterized by strengthening the administrative control of the central city and the regional reorganization of horizontal regionalization. The essence of the adjustment of the urban administrative divisions is a process of scale reengineering and regional reconstruction that is also a process of regional construction initiated by the central city government to increase the city’s competitiveness through the regionalization of capital. As a subregional construction, Hangzhou’s boundary reorganization delimited the new regional organization by administrative means to complete the reconstruction of the geographical space. Then, it rearranged the power and systems in the new regional organization to promote the de-regionalization and re-regionalization of capital [

38,

39,

40].

4.2. Scale Restructuring: Reshaping of Power Structure and Upgrading of Governance Structure

Depending on the completion stage of the power reconstruction of the regional organization, the scale reconstruction of urban administrative divisions can be divided into complete and incomplete scale reconstruction [

26]. The goal of the Hangzhou District boundary reorganization was to establish a governance structure and system on the scale of municipal districts. As shown in

Table 2, this reorganization of district boundaries did not change the administrative level and subordination of each city. The most striking changes were in the Xiaoshan, Yuhang, Fuyang, and Lin’an districts, which were divided into districts by county-level cities in the early years. At that time, Hangzhou agreed to remove the county-level cities gradually to ensure a smooth adjustment period. During the ongoing transition period, the removed county-level cities continue to maintain provincial administration of finance and county management while enjoying a high degree of autonomy in planning, transportation, education, medical care, and other responsibilities.

The transitional period effectively avoids the contradictions and conflicts related to subsuming the county-level cities into districts. However, it also obscures some of the complications. More than 20 years after Xiaoshan and Yuhang became part of its municipal district, Hangzhou still has not integrated these two cities into the main city. The adjustment splitting Yuhang District erased the geospatial scale on which the transitional system was based. Meanwhile, it assigned new scales to the new Yuhang and Linping districts and created two new municipal districts that gradually transitioned from financial “provincial management of counties” to “provincial management of counties in stock and municipal management of districts in increment”. This new scale was extrapolated to Xiaoshan, and since the integration of county-level cities into districts, the transitional system was improved, further strengthening the control over these peripheral municipal districts.

First, the scale balance has been realized horizontally and the power structure of each city reshaped. The complete scale recombination can be subdivided into three categories:

Yuhang District was split into the new Yuhang and Linping districts. Hangzhou established a city-district-level governance structure in the two new regional organizations, giving administrative power at the district level to the two administrative districts. The regional scope of power is smaller, but that does not mean less control over regional organizations; the New Yuhang and Linping districts have their own power at the municipal district level, and a complete governance system has been built.

In the main cities of Hangzhou, Shangcheng, and Jianggan, Xiacheng and Gongshu were merged. The original two district levels were integrated into one. The power structure and system did not change. After the merger, the regional organization of the power function of the new municipal district system was wider, but it did not affect the control of Hangzhou over each municipal district.

The Qiantang New Area belongs to the all-controlling management committee, which manages the economic and social affairs in the region in a unified way. Some scholars call functional areas such as the Qiantang New Area “quasi-administrative regions”. Although the Qiantang New Area has partially reconstructed its multidimensional administrative, spatial, and industrial relations, its scale reconstruction remains incomplete because of the boundary of the administrative division. In the adjustment, the district-level scale was assigned to the regional organization of the Qiantang District, completing its scale reconstruction, realizing the complete adherence of scale to the regional organization, and optimizing the governance structure and function of the former Qiantang New Area [

41].

Second, the adjustment completed the scale adaptation vertically and upgraded Hangzhou’s governance structure. In the first 20 years, Xiaoshan, Yuhang, Fuyang, and Lin’an were included in the urban map of Hangzhou, which has achieved rapid urban area and development space expansion. At the same time, the upgrade poses challenges to integrating new and old urban areas. From the view of the nationwide withdrawal of counties or integrating county-level cities into districts, there are several problems in certain areas, such as a large gap in the urban management level between central and peripheral urban areas; an uneven quality of public services; inadequate and unbalanced use of space, which requires the re-division of the internal power structure of the city; and the adjustment and reshaping of the governance structure to meet needs [

42,

43,

44]. This district boundary reorganization focused on resolving the differences in the size of Hangzhou’s municipal districts. Regionally cutting and reorganizing the municipal districts changed the power scale, reshaped each municipal district’s power structure, strengthened Hangzhou’s control over the municipal district, matched the power scale more to the regional scale, and reshaped and upgraded Hangzhou’s governance structure.

4.3. Regional Reconstruction: Optimization of Resource Elements and Urban Structure Transformation

Effective ways to optimize and integrate the resource elements of urban development on the micro-scale are scale reorganization among municipal districts’ allocation of resources, expanding the urban scale, and transforming urban structure. After reorganizing district boundaries, Hangzhou has jurisdiction over ten districts; however, new regional organizations have emerged in the city and district scales—new Hangzhou and several new municipal districts. Among them, Binjiang, Xihu, Fuyang, and Lin’an districts have the same regional scale. In contrast, Shangcheng, Gongshu, Xiaoshan, Yuhang, Linping, and Qiantang have all become new regional organizations at the district level.

First, to promote regional restructuring, Hangzhou carried out industrial optimization and collaborative layout, focusing on optimizing the urban structure of the eastern and western parts of the city. As shown in

Figure 4, focusing on the high-tech industry, the western part of the city focused on the innovation corridor platform, human resources, policies, and mechanism innovation to lead future economic development. The eastern part of the city relies on abundant higher education resources, high-end and intelligent manufacturing, and e-commerce. The eastern and western parts of the city should advance together, and the re-regionalization of capital should be promoted to create the high-quality development of the digital economy and manufacturing. The Yuhang and Linping districts have been divided geographically; according to their different development priorities, the re-regionalization of capital has been completed. The Yuhang District relies on the Science and Technology Innovation Corridor to develop high-end scientific and technological innovations and the digital economy. It focuses on digital industrialization, including artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and Big Data; emerging frontier industries, such as the metauniverse and quantum technology; and new business forms such as the digital economy and Smart Cities. The Linping District will connect workshop production equipment for biomedicine, home textiles, and equipment manufacturing to the industrial internet digital platform through 5G technology to accelerate industrial digitalization. The Qiantang New Area has been upgraded from an incomplete scale to a full-scale Qiantang District. Although the regional spatial entity has not changed, the power structure and relations have been reshaped systematically. The identity transformation from a functional area to an administrative region has made this district significantly more attractive to capital. Five leading industries (semiconductors, life and health, intelligent automobiles and intelligent equipment, aerospace, and new materials) have begun to take shape.

Second, Hangzhou promotes the construction of transportation and communication infrastructure for the regional reconstruction of capital to improve the urban construction environment, break barriers, and increase the speed of capital flow. Constructing transportation and communication facilities has the powerful effect of “space-time compression”, which can change traditional social relations; strengthen personnel interactions, economic liaisons, factor flows, and other spatial connections between the central urban area and the new jurisdiction; and promote the scalar reconstruction of capital. Following the layout of “one main city, three secondary cities, and six clusters”, Hangzhou has planned and built more than twenty new cities and more than one hundred urban complexes along the bank of the Qiantang River, including Qianjiang Century City, Zhijiang New City, Xianghu New City, Binjiang New City, and Airport New City.

In a functionally integrated but geographically dispersed production network, the smooth flow of information and materials is key to ensuring the continuity of the production process and improving production efficiency, so the construction of circulation space is particularly important.

Circulation space mainly refers to urban roads and other transportation infrastructure. Hangzhou will extend Jiefang Road east to Qianjiang New City; construct the Qingchun Road tunnel, Zizhi Tunnel, Wenyi West Road viaduct, and other traffic arteries, linking the new and old urban areas and north Jiangnan as a whole; open the Airport Express to connect Qianjiang New City with Hangzhou East Railway Station, Xiaoshan Airport, and other important transportation hubs; form a circulation network of resource elements connecting inside and outside areas; and connect the multi-group spatial layout of Hangzhou with an organic integrated regional space. Constructing circulation space has enhanced the communication and cooperation between the central city and the new districts, promoted the de-regionalization and re-regionalization of capital, and attracted capital to be embedded in the new municipal district [

45].

4.4. Summary

The administrative division adjustment patterns are closely related to the urbanization process. From 1983 to 1999, the urbanization development of China was characterized by the expansion of the absolute number of cities and the scalar expansion of key cities [

27]. The adjustments of administrative divisions in this stage are mainly registered as “region upgraded to city” and “county upgraded to city”, among which the division of counties (county-level cities) into districts (including the combination of districts and counties) was mainly concentrated in cities with higher administrative levels. Since 2000, urbanization in China has undergone large-scale urban expansion, primarily through withdrawing counties (county-level cities) by setting up districts or merging counties [

46]. The adjustment frequency is closely related to the level of economic development: the more developed the area, the higher the frequency of adjustment [

36]. Recently, Chinese urbanization has entered a new stage, moving from the expansion of the city scale to the enhancement of city function and connotation. The adjustment model of the administrative division has gradually changed from the integration of counties (county-level cities) into districts and the merger of districts and counties to the reorganization of district boundaries.

Hangzhou began its district boundary reorganization in 2021. First, it solved the problems of unbalanced urban scale and unreasonable spatial layout. Specifically, following the urban scale expansion, the area of Hangzhou’s outer city districts was too large, and the development of the inner-city space was insufficient and unbalanced. These problems have been effectively solved through district boundary reorganization, including city mergers and splits. Second, Hangzhou neatly reconstructed its urban governance structure with the district boundary reorganization. The purpose of urban administrative division adjustment was not simply to expand the scale but to optimize the spatial pattern and reshape the governance structure, releasing the city’s development potential [

47]. Third, it reduced the political cost of administrative division reform. Integrating counties (county-level cities) into districts involves inter-governmental maneuvering at the province, city, and county levels; the political costs and risks are correspondingly high. Many cases of fierce resistance from the counties (county-level cities) have been resolved. In contrast, reorganizing district boundaries involves power struggles only at the same level. The administrative subordination of each district is the same, and the difficulty coefficient and risk of the integration and coordination of the management system between them are low. Therefore, Hangzhou is gradually integrating its resources by reorganizing district boundaries, optimizing the layout of urban functions, upgrading the industrial structure, and improving the efficiency of urban governance.

Under the guidance of the “strong provincial capital” strategy, Zhejiang Province adjusted the scale strategy and regional development path in the new development stage to increase the central city and improve the urban competitiveness of Hangzhou, the provincial capital. Under the new regional strategic goal of integrating the development of the Yangtze River Delta, Hangzhou plays a leading role; its regionalization adjustment aims to strengthen the importance of this scale unit. From the perspective of scale reconstruction, Hangzhou used district boundary reorganization to adjust the power scale of municipal districts, promote coordinated development, and concentrate more local jurisdiction and development power on the Hangzhou scale level to create a new regional integrated development map.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Since 1978, after two phases of integrating counties (county-level cities) into districts from 1994 to 2003 and establishing districts since 2013, the number of municipal districts in China has increased. Many cities’ reserves for country-district mergers have become limited. Regional central cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Nanjing have entered the “district-wide model” where they can no longer rely on large-scale mergers of peripheral counties and cities to strengthen themselves as they did before. Instead, they need to intensively cultivate their own internal space.

Urban space production is a continuous process. In addition to the reorganization of district boundaries, Chinese city governments often use another approach—“setting up functional zones”—to optimize urban space without adjusting administrative divisions. However, the continuous development of functional areas will increase the chaos of governance relations, which is not conducive to the long-term development of the city. Therefore, in the long run, the reorganization of regional boundaries is still necessary. It is evident that, similar to the urbanization process in many developing countries, the increasing heterogeneous demand for city development in countries such as Indonesia, South Africa, and Brazil has led to the redefinition of urban boundaries and the addition of new administrative divisions, which in turn have prompted regional boundary restructuring. The boundary reorganization of Hangzhou District aims to optimize the internal relationship of urban space to meet the new needs of urbanization development. However, in Europe and North America, the merging of administrative divisions is used to optimize urban space to provide public services, indicating that Hangzhou’s experience can be an important reference for the urbanization process of other developing countries.

From the perspective of scale and regional restructuring, regional boundary restructuring is a regional construction scale strategy initiated by the central city government to enhance its competitiveness. It mainly achieves its goals in two ways. First, it promotes integration through segmentation. However, integrating cities and counties is problematic in China. Hangzhou removed the Xiaoshan District from the Dajiangdong area and the Jianggan District from the Xiasha area to form the Qiantang District. Hangzhou integrated the outer urban areas into the main urban area. Separating the old Yuhang District improved the transitional system; it used scale politics to extrapolate its adjustments to Xiaoshan, Fuyang, and Lin’an, which were divided into districts by counties (county-level cities) in the early years to strengthen Hangzhou’s control over peripheral municipal districts and integrate old Yuhang with the main city.

Second, this process promoted equilibrium through restructuring. Hangzhou’s broad spatial scale had caused a mismatch between regional scale and economic size and excessive differences in economic development. After the reorganization of the district boundaries, Hangzhou had jurisdiction over ten districts. However, it reorganized and optimized regional spaces by merging smaller districts and dividing larger ones to balance the development of various municipal districts.

Recently, different cities’ development demands have followed the expansion and structural adjustment of central city districts. Their expansion has been mainly conducted by withdrawing counties (county-level cities) to set up districts; structural adjustment has mainly relied on reorganizing district boundaries. Generally, after the number of central city districts expands to a certain scale, district boundary reorganization is carried out to adjust the power and regional scales of municipal districts, optimize the urban structure, and promote urban development. Thus, withdrawing counties and setting up districts can expand urban development space. According to the different development needs of the city, scale reorganization and regional reconstruction are carried out at different stages to promote development. In the future, the role of physical space expansion in enhancing urban competitiveness will become increasingly limited. Focusing on the structural adjustment and governance optimization of internal space is an effective way to enhance the central cities’ competitiveness. Urban development must solve the problems related to urbanization and urban development. Thus, district boundary reorganization will become a first choice as an effective and practical way of reforming the administrative divisions of central cities.

China is a typical developing country undergoing rapid urbanization. As an important central city in East China, Hangzhou is also a critical megacity in the Yangtze River Delta region. Using the Hangzhou District’s boundary reorganization as an example, this study has shown how Chinese city governments make urban spatial reconstruction serve urban growth by adjusting administrative boundaries. Reorganizing district boundaries reconstructs urban spaces to transform urban governments and adjust and redistribute the forces of urban governments, markets, and society. District boundary reorganization is the basis of urban planning, urban renewal, and other spatial optimization strategies, and it is important for urban space optimization and urban government reconstruction. This research can provide a general lesson for many cities in underdeveloped areas.

The contribution of this paper is mainly reflected in three points. First, the paper uses the theory of scale restructuring to analyze Hangzhou District’s boundary reorganization, expanding the scope of theoretical interpretation and further demonstrating its universal value. Second, by analyzing the case of Hangzhou, the intrinsic mechanisms of this process are summarized, providing a reference for the urbanization process of other developing countries. Finally, this paper’s research further enriches the discussion on Territorial Reforms, providing examples from a Chinese case for observing the methods and performance of Territorial Reforms.

Hangzhou District’s boundary reorganization incorporated several common forms of the spatial optimization of central cities in China. This study conducted a deep but not broad analysis of how China’s central cities optimize urban structure. Future studies should investigate internal structure optimization in more central cities in China—preferably all of them. Comparative studies should be conducted in various regions to identify differences in optimizing the inner spaces of central cities elsewhere in China.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C. and C.Y.; methodology, F.C.; software, C.Y.; validation, F.C., C.Y. and W.J.; formal analysis, F.C.; investigation, F.C. and C.Y.; resources, F.C.; data curation, F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C.; writing—review and editing, F.C.; visualization, F.C.; supervision, F.C. and W.J.; project administration, F.C.; funding acquisition, F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund Project “Risk and Prevention of Administrative Division Reform in Metropolitan Areas of China” (18BGL204) and the Special Fund for Basic Scientific Research of Central Universities for Nanjing University “Research on the Theoretical Basis and Realization Mechanism of Further Promoting Social Equity and Justice After the Building of a Moderately Prosperous Society in All Respects” (011714370119).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted with the support of Jinqun Wu, Chaochao Liao, and Sijin Chen from the School of Public Affairs, Zhejiang University. The authors thank the Hangzhou Municipal Government, Hangzhou Civil Affairs Bureau, Hangzhou Natural Resources, and Urban Planning Bureau, as well as the Yuhang, Linping, Gongshu, Qiantang, Xiaoshan, and Shangcheng District governments for their support. The authors also thank all interviewees for their cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the study’s design; data collection, analyses, or interpretation; manuscript creation; or the decision to publish the results.

References

- Boehm, L.K.; Corey, S.H. America’s Urban History; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schneidersliwa, R. Cities in Transition: Globalization, Political Change and Urban Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N.; Theodore, N. (Eds.) Spaces of Neoliberalism: Urban Restructuring in North America and Western Europe; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Saarimaa, T.; Tukiainen, J. Common pool problems in voluntary municipal mergers. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2015, 38, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weese, E. Political mergers as coalition formation: An analysis of the Heisei Municipal Amalgamations. Quant. Econ. 2015, 6, 257–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strebel, M.A. Incented voluntary municipal mergers as a two-stage process: Evidence from the Swiss Canton of Fribourg. Urban Aff. Rev. 2018, 54, 267–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlepas, N.-K. Incomplete Greek territorial consolidation: From the first (1998) to the second (2008-09) wave of reforms. Local Gov. Stud. 2010, 36, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Spolaore, E.; Wacziarg, R. Economic integration and political disintegration. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 1276–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, D. Democracy, decentralization, and district proliferation: The case of Ghana. Political Geogr. 2017, 59, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade Lima, R.C.; da Mota Silveira Neto, R. Secession of municipalities and economies of scale: Evidence from Brazil. J. Reg. Sci. 2018, 58, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, A. Regionalism and city–county consolidation in small metro areas. State Local Gov. Rev. 2000, 32, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojnovic, I. The transitional impacts of municipal consolidations. J. Urban Aff. 2000, 22, 385–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanguay, G.A.; Wihry, D.F. Voters’ preferences regarding municipal consolidation: Evidence from the Quebec de-merger referenda. J. Urban Aff. 2008, 30, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, A.; Dollery, B.; Thi Thanh Tran, C.-D. Amalgamation in action: Participant perspectives on the Armidale Regional Council merger process. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2019, 54, 436–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.J.C.; Wu, F. (Eds.) Restructuring the Chinese City: Changing Society, Economy and Space; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China’s Economic Data in 2022. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/search.htm?s=%E5%9F%8E%E9%95%87%E5%8C%96 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Wu, J.; Liao, C. Scale reorganization and regional reconstruction in urban administrative division reform: Based on data since 1978. Jiangsu Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. The Informational City; Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Rise of the Network Society; Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.; Dennis, W. The restructuring of geographical scale: Coalescence and fragmentation of the northern core region. Econ. Geogr. 1987, 63, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. Contours of a spatialized politics: Homeless vehicles and the production of geographical scale. Soc. Text 1992, 33, 54–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M. The rise of the regional state in economic governance partnerships for prosperity or new scales of state power. Environ. Plan. 2008, 33, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. Scale, state, and the city: Urban transformation in post-reform China. Habitat Int. 2007, 31, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The geopolitics of capitalism. In Social Relations and Spatial Structures; Gregory, D., Urry, J., Eds.; Macmillan: London, UK, 2011; pp. 313–333. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N. Globalization as reterritorialisation: The re-scaling of urban governance in the European Union. Urban Stud. 1999, 36, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J. Administrative Division Adjustment of Metropolitan Areas: Regional Reorganization and Scale Reconstruction; China Architecture Publishing & Media Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 92–102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Wang, X.; Geng, L. The adjustment of administrative divisions in China’s metropolitan areas: The stages and characteristics since the acceleration of urbanization. City Plan. Rev. 2015, 39, 44–49. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Li, G.; Wang, C. The dynamic mechanism of administrative division Evolution from the perspective of scale reconstruction: A case study of Guangdong Province. Human Geogr. 2016, 31, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Luo, X. Capital, power, and space: An analysis of “space production”. Human Geogr. 2012, 27, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L. Urban administrative restructuring, changing scale relations and local economic development in China. Political Geogr. 2005, 24, 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yu, Q. Structural adjustment of national space: Changes and functional transformation of China’s administrative divisions in the past 70 years. Exec. Forum 2019, 26, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Cheng, Y.; Yin, J.; Wang, Y. Province-leading-county as a scaling-up strategy in China: The case of Jiangsu. China Rev. 2014, 14, 125–146. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23723004 (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Kuang, Z.; Sun, B. The new national spatial framework interprets the spatial transformation of China: A reexamination. Prog. Geogr. 2021, 40, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, R. The transformation of regional governance in China: The rescaling of statehood. Prog. Plan. 2012, 78, 55–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hangzhou Committee of Culture and History of the CPPCC. A River of Spring Water Flowing East: Historical Data on the Adjustment of Urban Administrative Divisions in Hangzhou (1996–2017); Hangzhou Publishing House: Hangzhou, China, 2018. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Chen, T.; Wang, K.; Qi, W. The evolution and driving forces of China’s administrative division pattern since the reform and opening up. Geogr. Res. 2015, 34, 247–258. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reply of the State Council on Approval of the Adjustment of Some Administrative Divisions of Hangzhou in Zhejiang Province; Reply Guohan. 2021. Available online: https://www.zj.gov.cn/art/2021/4/10/art_1554469_59094957.html (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Hangzhou Daily. On the Optimization and Adjustment of Administrative Divisions: Bear in Mind the Eager Expectations and Shoulder the Historical Mission, 9 April 2021. Available online: https://m.thepaper.cn/baijiahao_12127040 (accessed on 14 March 2023). (In Chinese).

- Hangzhou Daily. Second Discussion on the Optimization and Adjustment of Some Administrative Divisions: Bringing Out a New Atmosphere to Promote New Development, 10 April 2021. Available online: https://www.hzzx.gov.cn/cshz/content/2021-04/11/content_7945287.htm (accessed on 14 March 2023). (In Chinese)

- Hangzhou Daily. Third Discussion on the Optimization and Adjustment of Administrative Divisions: Insisting on Benefiting the People and Enterprises and Sharing a Better Life. 11 April 2021. Available online: https://zj.zjol.com.cn/red_boat.html?id=101184563&ivk_sa=1023197a (accessed on 14 March 2023). (In Chinese).

- Wang, F.; Liu, Y. Scale politics of administrative division adjustment in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2019, 74, 2136–2146. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. The economic impact of Special Economic Zones: Evidence from Chinese municipalities. Dev. Econ. 2013, 101, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schminke, A.; Van Biesebroeck, J. Using export market performance to evaluate regional preferential policies in China. Rev. World Econ. 2013, 149, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Sun, W.Z.; Wu, J.F.; Matthew, E.K. The birth of edge cities in China: Measuring the effects of industrial parks policy. Urban Econ. 2017, 100, 80–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhejiang Daily. Some Administrative Divisions in Hangzhou Are Optimized and Adjusted to the “Full Moon”. What kind of Answers Will the Five Districts Involved in the Reform Hand in? 10 May 2021. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1699324179298001959&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 14 March 2023). (In Chinese).

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, E. Discussions and prospects on the study of “removing counties and establishing districts”. Chin. Pub. Adm. 2021, 2, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Yin, J.; Tian, D. Incomplete re-territorization and administrative division reorganization of metropolitan area: A case study of Jiangning City, Nanjing. Geogr. Res. 2010, 29, 1746–1756. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).