Urban Modeling in the Global South and Sustainable Socio-Territorial Development: Case of Puebla-San Andrés Cholula Urban Binomial, Mexico

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Case Study

3.1. Puebla-San Andrés Cholula: Foundation, Development and Globalization of an Urban Binomial

3.1.1. Cholula: The Ancient City

3.1.2. Puebla: Foundation and Development of a Colonial City

3.1.3. Modernization of a Colonial City and Emergence of the Urban Binomial

4. Results

4.1. References from the Global North: Global Economy, Expulsions, and Environmental Crisis

4.2. References from the Global South: Local Scope of the Postcolonial Southeast Asia

4.2.1. Cities and National Ambitions

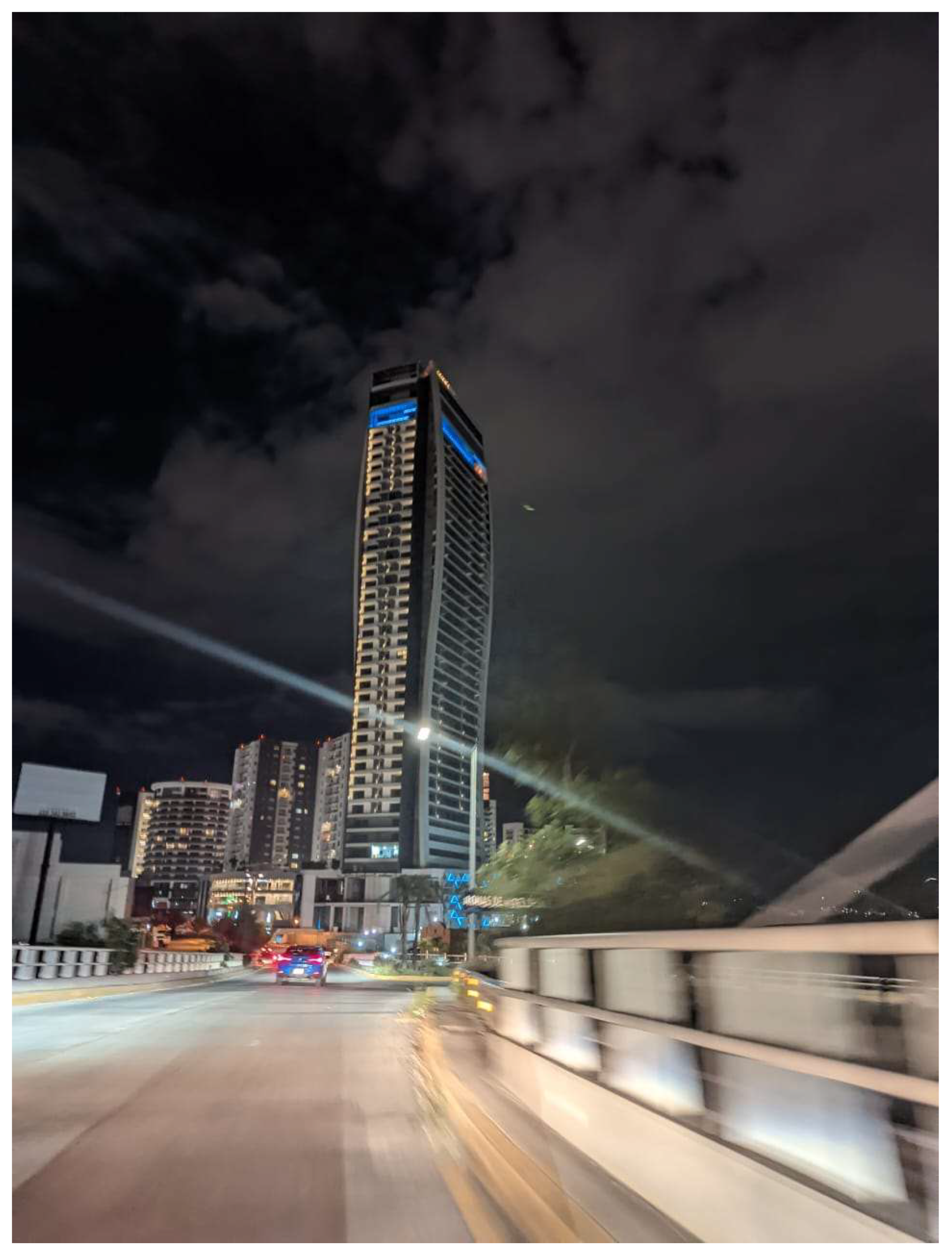

4.2.2. Territorial Order, Land Speculation, and Urban Modeling

4.2.3. Becoming Global in Latin America?

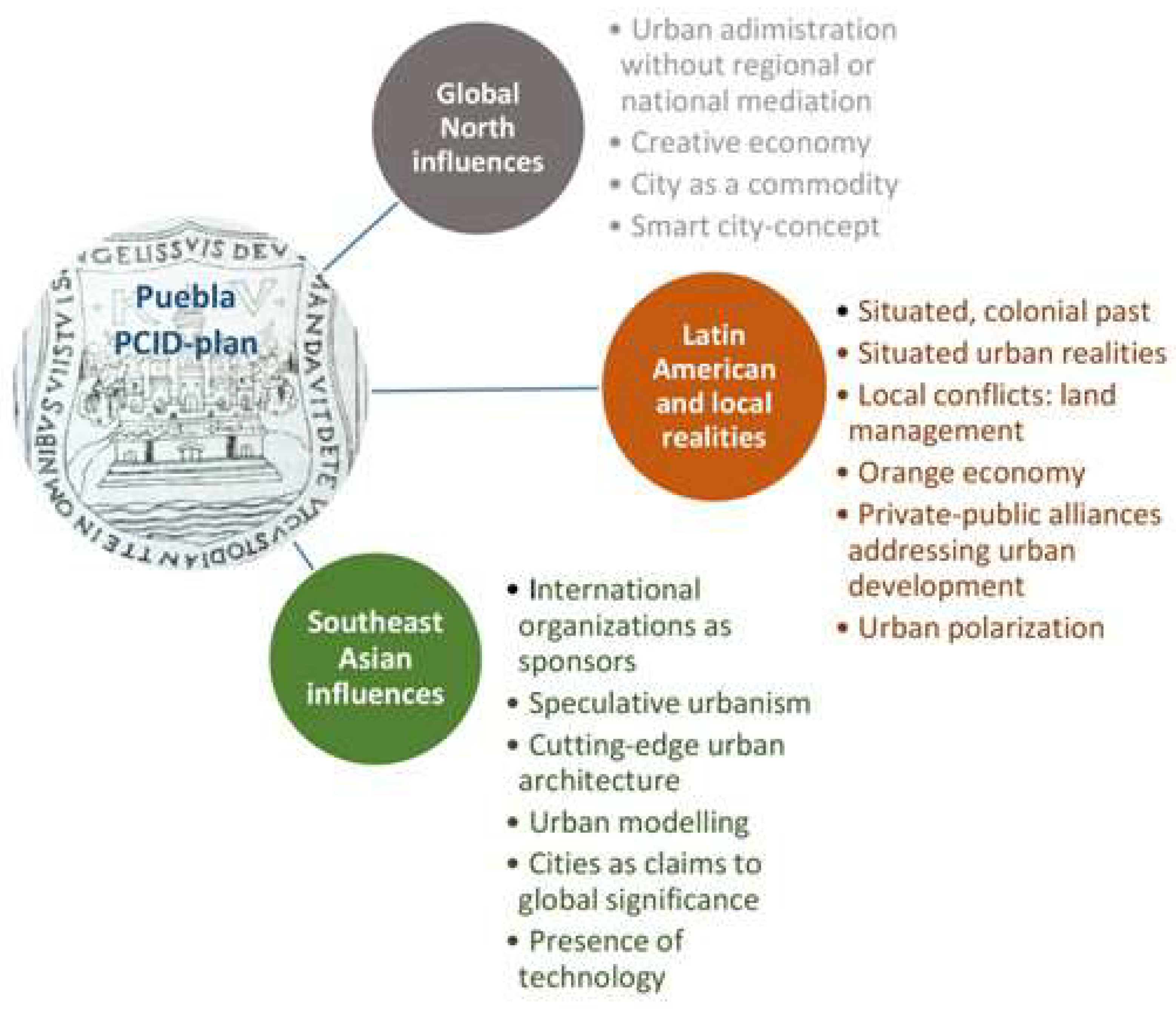

4.3. Worlding the ‘New Puebla’

4.3.1. Urban Modeling and Creation of a Global Imaginary

4.3.2. Pueblos Originarios, Neoliberal Land Management, Territorial Disputes, and Socio-Racial Discrimination

States shall consult with indigenous peoples through their own representative institutions to obtain their free prior informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the use of mineral, water or other resources.[38] (p. 12)

4.4. Key Findings

4.4.1. Global Influences

4.4.2. Urban Planning, Land Use and Management: Social Sustainability, Discrimination, and Population Displacements

4.4.3. Ecological and Environmental Sustainability

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Suggestions for Public Policy

6.2. Limitations and Future Studies

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ong, A.H. Powers of sovereignty: State, people, wealth, life. Focaal 2012, 64, 24–35. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1076.8435&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 7 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Mouton, M.; Shatkin, G. Strategizing the for-profit city: The state, developers, and urban production in Mega Manila. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2020, 52, 403–422. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0308518X19840365?casa_token=qUIUqAYABkMAAAAA:9xqHCghYVQmFnwaAUN_2mWgwnoeK1yPwKLTtwjFc2NgdQwl0LqATw2EjaHTxdYRX1q_V41TtILCD4cE (accessed on 7 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.H. Introduction: Worlding cities, or the art of being global. In Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global; Roy, A., Ong, A.H., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: London, UK, 2011; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, G. Relational comparison revisited: Marxist postcolonial geographies in practice. Progress in Human Geography 2018, 42, 371–394. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0309132516681388. (accessed on 17 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Shatkin, G. Planning to forget: Informal settlements as ‘forgotten places’ in globalising Metro Manila. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 2469–2484. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00420980412331297636?casa_token=qEUTrRsrT8AAAAAA:XhQKvO6Ody7joUpAwsn7lq4XsY4Bu0zZZzoN29npLJwmDzCsq8Tp34Fj7b4HfEw89HqtSJ7ruIeWwdk (accessed on 7 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, INEGI. Síntesis de Resultados. Zona Metropolitana de Puebla-Tlaxcala. XII Censo General de Población y Vivienda. 2000. Available online: http://internet.contenidos.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/productos/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/historicos/2104/702825496609/702825496609_1.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, INEGI, Mapa digital de México. 2023. Available online: http://gaia.inegi.org.mx/mdm6/?v=bGF0OjE5LjA2NDEwLGxvbjotOTguNzYzNjEsejozLGw6YzExMXNlcnZpY2lvcw== (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Ashwell, A. Cholula: Su herencia en una red de agujeros. Elem. Cienc. Cult. 2004, 11, 3–11. Available online: https://elementos.buap.mx/directus/storage/uploads/00000002632.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Schumacher, M.; Kurjenoja, A.K. La figuración del paisaje de Cholula a través de la mirada de Alexander von Humboldt: Reflexiones sobre su transformación territorial y socio-cultural. Tekopora Lat. Am. J. Environ. Humanit. Territ. Stud. 2021, 3, 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes García, C. Altepetl: Ciudad Indígena; Cholula en el Siglo XVI; UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfil Batalla, G. Cholula: La Ciudad Sagrada en la era Industrial; UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, N.E. Erasing Popular History: State Discourse of Cultural Patrimony in Puebla, Mexico. In Proceedings of the XXII International Congress of the Latin American Studies, Miami, FL, USA, 16–18 March 2000; pp. 1–10. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.552.5857&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Loreto López, R. El microanálisis ambiental de una ciudad novohispana. Puebla de los Ángeles, 1777–1835. Hist. Mex. 2008, 57, 721–774. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25139804 (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Vélez Pliego, F. Puebla de Zaragoza, Antigua Ciudad de los Ángeles, Patrimonio Cultural de la Humanidad. Rev. Soc. Ciudad. Territ. 2011, 1, 1–47. Available online: https://issuu.com/ablmartilu/docs/pueblafvp (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Bhabha, H. Location of Culture; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kurjenoja, A.K.; Ismael, M.E. ¿Puebla, ciudad creativa ó inteligente? In Ciudad, Capital y Cultura; Hernández, A., Kurjenoja, A., Ismael, A.K., Comp, M.A., Eds.; Editorial Itaca: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018; pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- ProMéxico. Mapa de Ruta. Puebla Capital de Innovación y Diseño; ProMéxico: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Buitrago Restrepo, F.; Duque Márquez, I. Economía Naranja; Inter-American Development Bank IDB: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Available online: https://books.google.com.mx/books/about/La_econom%C3%ADa_naranja.html?id=I9N2DwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&hl=es-419&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Kurjenoja, A.K. Interview in person with a Local Urbanist. Personal communication, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- de Puebla, G.E. Programa Regional de Ordenamiento Territorial Angelópolis; Puebla: Mexico City, Mexico, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kurjenoja, A.K. Economía creativa y cultura en la transformación desarrollo de dos ciudades mexicanas: Puebla y Tijuana. In Globalópolis (Provisional Name of the Book); Marchand, M., Morales, I.M., Meza, E., Eds.; Editorial Porrúa: Mexico City, Mexico, 2023; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. Territorio, Autoridad y Derechos de los Ensamblajes Medievales a los Ensamblajes Globales; Katz: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Rebel Cities. From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. Expulsions. Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- García Canclini, N. Imagined Globalization; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, M. Speculating on the next world city. In Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global; Roy, A., Ong, A.H., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: London, UK, 2011; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Howkins, J. Creative Economy; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- ProMéxico. Wikipedia. Available online: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/ProM%C3%A9xico (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Kurjenoja, A.K. Interview in person with the Architect of PCID Public Spaces. Personal communication, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- DataMéxico. San Andrés Cholula; DataMéxico: Municipio de Puebla, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guevara-Romero, M.L.; Ramírez Rosete, N.L. Condiciones de movilidad en colonias marginadas. Unidad territorial Atlixcáyotl, Puebla. Bitácora Urbano Territ. 2019, 29, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Maps. Available online: https://www.google.com.mx/maps/@19.0753479,-98.3221855,13z?entry=ttu (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Honorable Congreso de la Unión. Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos; 25 Legislatura Cámara de Diputados: Mexico City, Mexico, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, M.; Guizar Villalvazo, M.; Kurjenoja, A.K.; Durán-Díaz, P. The Writ of Amparo and Indigenous Consultation as Instruments to Enforce Inclusive Land Management in San Andrés Cholula, Mexico. Land 2023, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Juárez, E.G.; Kurjenoja, A.K.; Schumacher, M.; Guizar Villalvazo, M.; Gonzalez Meza, E.; Durán-Díaz, P. Neoliberal Urban Development vs. Rural Communities: Land Management Challenges in San Andrés Cholula, Mexico. Land 2022, 11, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- InLAB. Territorio and Urban Artifact Research Group. Interview in person with Cholultecas Unidos en Resistencia, CHUR. Personal communication, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tetra Tech. Effective Engagement with Indigenous Peoples: USAID Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance Sector Guidance Document. United States Agency for International Development. 2020. Available online: https://www.climatelinks.org/sites/default/files/asset/document/2020_USAID_Effective-Engagement-with-Indigenous-Peoples-USAID-Sustainable-Landscapes-Sector-Guidance-Document.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- United Nations. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. 2007. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- United Nations and General Assembly. Universal Declaration of Human Rights; United Nations: Paris, France, 1948. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights2 (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Ley de Ordenamiento Territorial y Desarrollo Urbano del estado de Puebla. 2017. Available online: https://www.congresopuebla.gob.mx/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=12924&Itemid= (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Anderson, N. Sociología de la Comunidad Urbana. Una Perspectiva Mundial; Fondo de Cultura Económica: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, M.; Durán-Díaz, P.; Kurjenoja, A.K.; Gutiérrez-Juárez, E.; González-Rivas, D.A. Evolution and Collapse of Ejidos in Mexico—To What Extent Is Communal Land Used for Urban Development? Land 2019, 8, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, INEGI. Panorama Sociodemográfico de Puebla. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020; INEGI: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2021.

- El Consejo Nacional de Evaluacion de la Politica de Desarrollo Social, CONEVAL. Estadísticas de Pobreza en Puebla. Available online: https://www.coneval.org.mx/coordinacion/entidades/Puebla/Paginas/principal.aspx. (accessed on 7 October 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurjenoja, A.K. Urban Modeling in the Global South and Sustainable Socio-Territorial Development: Case of Puebla-San Andrés Cholula Urban Binomial, Mexico. Land 2023, 12, 2081. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12112081

Kurjenoja AK. Urban Modeling in the Global South and Sustainable Socio-Territorial Development: Case of Puebla-San Andrés Cholula Urban Binomial, Mexico. Land. 2023; 12(11):2081. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12112081

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurjenoja, Anne K. 2023. "Urban Modeling in the Global South and Sustainable Socio-Territorial Development: Case of Puebla-San Andrés Cholula Urban Binomial, Mexico" Land 12, no. 11: 2081. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12112081

APA StyleKurjenoja, A. K. (2023). Urban Modeling in the Global South and Sustainable Socio-Territorial Development: Case of Puebla-San Andrés Cholula Urban Binomial, Mexico. Land, 12(11), 2081. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12112081