Abstract

Since the global crises in the 2000s, many foreign and domestic actors have acquired large tracts of land for food and biofuel crop cultivation and other purposes in Africa, often leading to the displacement of the African people living on customary land. The weak customary land rights of ordinary African people have been viewed as one of the main factors making it possible for various land-grabbers to exploit customary land with different purposes. However, it would be insufficient to conclude that the weak customary land rights are the only factor leading to land grabbing in Africa as such land rights give the inheritors the rights to use the land permanently. Therefore, the main objective of this research is to identify a more specific factor leading to land grabbing in Africa, which this article refers to as a ‘land-grabbing-friendly legal environment’. To achieve the main goal, by considering the case of Zambia, this research aims to: (1) analyze the main areas and regions where land grabbing occurs in Zambia and the land-grabbers involved; and (2) analyze the main uses of customary land and changes in tenure systems applied to customary land from the colonial era up to the present day, through a legal history research approach. The main findings of this research are as follows: (1) land-grabbing incidences have often been linked to the government-led agricultural program, involving both internal and external land-grabbers, and (2) the creation of the dual-tenure system during the colonial era and its continuation to the present day have led to the poor financial status of ordinary Zambians living on customary land, contributing to their weak customary land rights. By examining the main results, this research concludes that it is crucial for the Zambian government to bring about reasonable fees for land-titling registration for the ordinary Zambians living on customary land, as well as to separate development aspects from land laws. These steps will strengthen the land rights of the ordinary Zambians and prevent land grabbing.

1. Introduction

Due to the global crises since the 2000s, transnational companies and other economic actors have been increasingly acquiring land for food and biofuel crop cultivation, as well as the production of various types of energy sources in Africa and other developing regions. One of the negative outcomes of such land acquisition by foreign economic actors is land grabbing which results in the displacement of individuals and communities in the host countries. Thus, land grabbing often refers to financially rich but resource-poor nations and private investors searching for financially poor but resource-rich countries to secure their needs (e.g., food and energy sources), leading to the displacement of peasants and indigenous people, along with the destruction of the environment, in the Global South [1,2].

Since the 2000s, the African continent has become a hotspot for global land deals, which are often characterized as land grabbing [3,4,5]. As the land in Africa provides important export-earning sources for fiscal revenue, such as food, energy, and mineral sources, land grabbing has become a major issue in the continent’s economy. More importantly, as over 50% of the African population is working in the agricultural sector, land grabbing by foreign actors can result in the loss of their livelihood [6]. However, it would be insufficient to conclude that land grabbing occurs on the continent only due to foreign economic actors. The shady land deals of African chiefs with foreign actors and the African government’s own agricultural projects (e.g., outgrower scheme) have also resulted in the displacement of local African communities. What is more concerning is that most land-grabbing incidences in Africa occur on customary land, which is supposed to be the land of the ordinary African people [7,8,9,10]. In fact, the weak land rights of ordinary African people living on customary land—namely, customary land rights—have been viewed as one of the main factors making it possible for various land-grabbers to exploit customary land for different purposes [9]. However, much of the previous research and reporting on land grabbing in Africa seems to focus primarily on recent cases of encroachment on customary land on the continent by foreign and domestic actors. Furthermore, while weak customary land rights have often been cited as a cause of land grabbing in Africa in past studies, an in-depth analysis of the main historical factor leading to the weak customary land rights is lacking. This is a key factor that needs to be analyzed to understand the full picture of the land-grabbing research in Africa, and this research intends to fill this gap.

During the period of 1970–2020, Zambia had one of the highest numbers of large-scale land deals with foreign actors on the Continent: Mozambique (116 deals), Ethiopia (101 deals), and Zambia (63 deals) were the top three African countries to make large-scale land deals during the period of 1970–2020 [11]. In particular, since 2000, the number of land deals with foreign actors in Zambia has substantially increased, and the country is experiencing many land-grabbing incidences on its customary land [11]. Using Zambia as a case study, this research aims to: (1) Collect and analyze the land-grabbing incidences in Zambia. This process will serve to determine who the land-grabbers are and on what basis land grabbing occurs in Zambia, which will allow for a better general understanding of land-grabbing cases in Zambia; and (2) analyze the changes in the main usage of customary land throughout history, from the colonial era to the present day, and the land tenure system applied to those who live on customary land in Zambia. Identifying these changes is expected to not only indicate the historical factors that led to the weak customary land rights of the ordinary Zambians, but also whether such customary land rights are the only factor that has made them the victims of land grabbing.

The overall objective of this research is to show that the main cause of land grabbing in Zambia is the fact that different land-grabbers can manipulate the land-grabbing-friendly legal environment, in order to accumulate what they desire. This research also aims to show that ordinary Zambians continue to suffer from land grabbing, not only because of the customary land rights, but also due to the long-term inequality between the people living on state land and customary land, which has been implemented and continued from the colonial period to the present day.

2. Land Grabbing in Africa

Many large-scale land deals are made globally to produce food, energy, and minerals, and Africa seems to be a hotspot, in this regard [3]. Table 1 shows the number of large-scale land deals concluded by transnational companies in different continents during the periods of 1970–1999 and 2000–2020, from which it is possible to see that the number of land deals dramatically increased during the latter period. Africa is the continent with the second-highest number of land deals concluded, following Eastern Europe; however, most land-grabbing incidences occurred on the African continent [4,5].

Table 1.

Large-Scale Land Deals Involving Transnational Companies, 1970–1999 and 2000–2020 [11].

Although there may be many reasons for this continent being a hotspot for large-scale land deals, the global food and energy crises which began in the 2000s are known to be the main drivers. The food price spikes during the period of 2007–2008 made food-importing countries vulnerable to fluctuations of global food markets. This led many countries to focus on securing land and water beyond their own nation, in order to supply their growing populations [1]. For instance, Daewoo Logistics, a South Korean company, made a deal with the government of Madagascar in 2008 to produce palm oil and corn for export on 1.3 million hectares (ha) of populated areas. However, opponents of the Ravalomanana regime led by Andry Rajoelina used the Daewoo case to illustrate how the Ravalomanana regime was stripping the national resources and land. As a result, Daewoo’s project was abandoned and the opposition toppled the Ravalomanana regime in March of 2009 [12]. The Daewoo case is one of the most famous cases representing a foreign company’s attempts to use African land to solving the food security issues of its own nation.

Along with the food crisis, the rising and fluctuating oil prices during the period of 2007–2009 led biofuel companies to search for land for biofuel crop cultivation. In particular, the Renewable Energy Directive of the European Union (EU) played a crucial role in leading European companies to acquire land in Africa. For instance, the EU legislated that, by 2020, 20% of all energy use in the EU and 10% of the transport fuels used in member countries should come from renewable sources. Among various types of renewable sources, most energy was expected to come from biofuels [13]. It was also encouraged that such a target should be met through a combination of domestic production and import [14]. As the demand for biofuel increased, the EU countries, investors, and companies saw African land as an opportunity for the cultivation of biofuel crops [9,13]; for instance, the number of large-scale land deals between foreign companies and African countries for the cultivation of jatropha—a second-generation biofuel crop—increased substantially during the period of 2008–2009, both in Africa and other parts of developing regions, such as Asia and Latin America [15]. The main reason why foreign investors and companies chose to make land deals in Africa is that it has large, under-used land reserves, low population density, and reasonable climate and soil conditions. Another explanation for why the African continent is attractive for investors is that the land is cheap (or under-valued), making it an excellent investment [16]. Thus, the combination of the energy crisis and the African continent’s land advantages led foreign investors to lease African land to produce biofuels for exports to the EU, which often resulted in the displacement of the African people [17]. Accordingly, it is generally the case that such foreign investors have been considered as land-grabbers in Africa and other developing regions [1,2].

However, as mentioned earlier, it should be noted that land-grabbers on the continent do not only include foreign actors. For instance, there are cases where local chiefs did not consult their communities regarding foreign companies leasing their land, resulting in the displacement of the local community. Furthermore, the government’s own agricultural projects (e.g., outgrower schemes) have forced local communities to move off their land with an insufficient level of compensation [7,8,9,10]. This means that the state or government itself, as well as related actors such as chiefs, can also be considered as land-grabbers in Africa. Thus, land grabbing in Africa should be understood in a broader context, as it involves both internal and external land-grabbers. In fact, Harvey’s [18] “accumulation by dispossession” appears suitable for describing land grabbing in Africa, as it includes the commodification and privatization of land and expulsion or displacement of peasant populations through the conversion of property rights into exclusive private property rights; suppression of rights to the common; colonial, neo-colonial, and imperial processes of appropriation of assets such as land; and use of slave and credit systems as a means of primitive accumulation. Here, capital accumulation is at the heart of accumulation by dispossession. More importantly, this process includes foreign actors (e.g., multinational companies and investors) and the state or government themselves as crucial actors, which play roles in capital accumulation and dispossession [19]. Hence, land grabbing can be defined as land transactions that involve illegal behaviors and actions (e.g., no consultation between the investors and the local community, an insufficient level of compensation to the local community, and eviction of the local community), when in reality they are perfectly legal actions between internal (e.g., government and state) and external (e.g., multinational companies and investors) actors [20].

In Africa, it is often the case that land-grabbing incidences occur on customary land where a customary land tenure system is applied. Customary land tenure is the traditional land tenure system in Africa, and it has been estimated that about 90% of the land in sub-Saharan Africa is under this system [21]. Such a land tenure system is often viewed as one of the most crucial factors contributing to land grabbing in Africa [9]. Under the customary land tenure system, it is often the case that land does not belong to the individual but, rather, to families, communities, and villages. The ownership of land under this system gives the rights to occupy and use land, rather than providing absolute ownership of land, as is seen in Western society. Furthermore, there is no established system for registering who has the rights to occupy and use the land in most parts of the continent. Accordingly, it has been argued that the combination of communal ownership of land and lack of individual land rights documentation have led to the weak tenure security of the African people, as their land rights are not officially protected by law [22]. Thus, one may argue that the weak customary land rights due to the customary land tenure system may make ordinary Africans the victims of land grabbing.

However, it would be insufficient to conclude that the customary land tenure system does not protect the land rights of ordinary Africans at all. Traditionally, African land was first preserved by community ancestors, inherited by their living representatives, current occupants, and then on to the future generation [8]. Here, although it is not the same as privatization of land or land rights based on land titling, the inheritors have the rights to use the land permanently. In other words, the customary land tenure system can be viewed as a long-term lease. Therefore, it can be considered that the argument that the idea of a customary land tenure system does not protect African land rights or leads to weak tenure security is purely based on Western perspectives [23]. As the customary land tenure system provides a certain level of tenure security to Africans living on customary land, it would be wrong to simply conclude that land grabbing in Africa occurs due to the customary land tenure system. Accordingly, it has become ever more important to analyze the connections among different land-grabbers, customary land tenure systems, and historical changes in the usage of customary land, in order to understand the cause driving land grabbing in Africa.

3. Materials and Methods

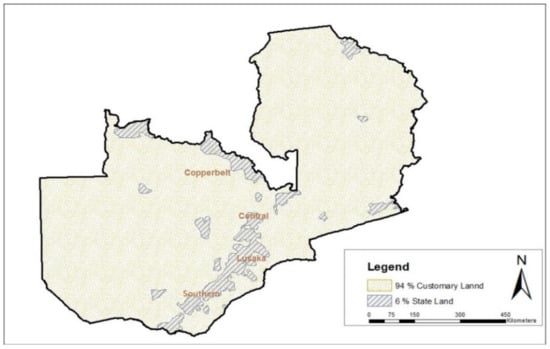

Zambia has a total surface area of 743,398 km2 and a population of 19,642,123 [24]. Zambia’s population density is 26.2 people per km2 which is one of the lowest in Sub-Saharan Africa [25]. Zambia consists of 10 provinces (Western, North-Western, Copperbelt, Central, Luapula, Northern, Muchinga, Eastern, Lusaka, and Southern). Each province is divided into several districts. Customary land accounts for 94% of the total land area in Zambia while state land accounts for 6% of the total land area [26]. As shown in Figure 1, state land mainly consists of a patch of land in the central part of the country, from the Southern Province to the Copperbelt Province, and the rest is customary land. Further, the populations of Lusaka Province (2,777,439), Copperbelt Province (2,362,207), and Southern Province (1,853,464) are the highest among other Provinces, which are the main state-land areas [27].

Figure 1.

Distribution percentage of state land and customary land in Zambia [28].

As mentioned above, the overall objective of this research was to determine the main cause of the continuous land grabbing on the continent, taking Zambia as a case study. In order to achieve the main aim, this research was conducted in two main steps.

3.1. Data Source and Method for Analyzing the Main Land-Grabbing Areas and the Land-Grabbers in Zambia

First, this research analyzed the land deals and land-grabbing incidences in Zambia, with the aim of showing the main areas and regions where land deals and land grabbing occur, as well as the different actors involved in land grabbing (i.e., land-grabbers). The overall objective of the first step is to show that it is not only foreign actors, but also internal actors (e.g., government, chiefs) that are involved in land grabbing in Zambia. Thus, we aim to prove that land grabbing in Zambia should be understood as ‘accumulation by dispossession,’ as stated by Harvey [18]. This process also serves to indicate the basis (e.g., governmental agricultural projects) on which land grabbing occurs in the country, which is crucial for understanding land-grabbing trends in Zambia. To collect such information, this research used the database provided by Land Matrix.

Land Matrix is an independent global land monitoring initiative which provides a systematic overview of large-scale agricultural investments. It provides information about land deals in almost 100 countries, including intended, concluded, and failed attempts to acquire land, the deal size, and intention of investment (e.g., agriculture, forestry, or mining). More importantly, Land Matrix provides each land deal with information about whether land grabbing (e.g., displacement of local people) has taken place, and who the displaced people consider as the land-grabber [29].

Once all land deals were collected, this research selected all the deals that are connected to land-grabbing incidences. As this section aims to gather as much land-grabbing information as possible, all land deals (intended, concluded, failed negotiation status, and implementation status) with all types of investment (agriculture, forestry, and mining) were collected. After collecting land deals with the land-grabbing incidence, each case’s relevant literature provided by Land Matrix was analyzed. During this process, the displacement process, land deal negotiations among the local people and other actors (e.g., transnational company, chiefs, government), and the main land-grabbers were analyzed. A concerning matter is that Land Matrix provides information about land deals between 1970 and 2020. This means that it was not possible to obtain information on land deals made in Zambia during the colonial period. However, as our main purpose is to understand the trend of land grabbing (e.g., location, land-grabber, displacement) in Zambia, which started to receive more attention since 2000s, coverage of only the period of 1970–2020 was not considered a shortcoming.

3.2. Material and Method for Analyzing the Uses of Customary Land and Changes in Tenure Systems Applied to Customary Land throughout History

Second, in order to determine the changes in customary land rights and the usage of customary land, this research analyzed relevant land laws of Zambia, ranging from the colonial era up to the present day. This is because land laws present and clarify how different types of land should be used in the country. Furthermore, they indicate how customary land itself is used and how customary land rights are secured. As Zambia’s land law was initially commenced during the colonial period, it is crucial to analyze relevant land laws from the colonial period until present.

More specifically, this research analyzed land laws that are directly connected to customary land and land rights in three main periods of time: (1) the pre-colonial era; (2) during the colonial era; and (3) after independence. Comparison between the first two periods indicates the impact of the colonial era on traditional land rights and the use of land in Zambia, while analysis of the latter two periods demonstrates whether the Zambian government restored the (customary) land rights of the ordinary Zambians after independence.

Table 2 lists the main land laws analyzed in this paper, in order to determine how the customary land rights and the usage of customary land changed. For the Colonial era, the Northern Rhodesia Order in Council, 1911, was selected, as this is the first official land law that took land rights away from Zambians. Furthermore, the Northern Rhodesia (Crown Lands and Native Reserves) Order in Council, 1928, and Native Trust Land Order in Council, 1947, were selected for the colonial era, as these laws officially categorized Zambian land and created customary land (e.g., native reserves and native trust land). As these laws specifically differentiated the level of land rights for different categories (e.g., crown land, native reserves, and native trust land), they are important in understanding customary land rights and usage of customary land in Zambia.

Table 2.

Main land laws in different periods in Zambia.

After independence, Zambia has undergone two major land reforms: in the 1970s, under the David Kenneth Kaunda Regime, and in the 1990s, under the Frederick Chiluba regime, which enacted the Land (Conversion of Title) Act 1975 and Land Act 1995, respectively. These land laws attempted to change the nature of the land rights and tenure systems, and had a great impact on foreign actors (e.g., companies and investors) entering the country. Thus, it is crucial to analyze these laws, as they deal with land rights of the ordinary people living on customary land, which may help to determine the factors making them the victims of land grabbing.

The present legal system and the land values underlying them are the culmination of historical development. Therefore, a legal history research approach was followed in this research section. Historical legal research approach method demonstrates the social transformation dimensions of law and gives ideas for understanding the present law. Legal history “seeks to liberate us from the tyranny of the old, from the sway or hold of the past, by explaining the historical context of some legal text or institution” [30] (p. 207). As this approach can be used to compare a certain aspect of the law in a given jurisdiction at different periods of time, it can help to present the legal problems which are rooted in the past, and also provide guideposts by showing how the law has developed and evolved over the years [31,32]. Thus, this method was considered a good fit to analyze how customary land rights and the use of customary land have changed in the context of law, as well as how related problems (e.g., weak land rights) have developed.

4. Results

4.1. Land Grabbing in Zambia

During the period of 1970–2020, there were 63 large-scale land deals with different negotiation statuses in Zambia. Among these land deals, 52 were concluded, seven were failed, and four were intended. Regardless of negotiation status, 44% of land deal intention of investment was for food crops, followed by livestock (17%), biofuel (15%), non-food agricultural commodities (7%), mining (7%), renewable energy (4%), unspecified agriculture (3%), and others (4%) [33].

As can be seen from Table 3, during the period of 1970–2020 in Zambia, the district where most land deals was made was Serenje (six deals in Central Province), followed by Solwezi (North-Western), Mkushi (Central), and Choma (Southern), with four deals each, and Mumbwa (Central), Mbala (Northern), Mazabuka (Southern), Lusaka (Lusaka), Lufwanyama (Copperbelt), Kawambwa (Luapula), and Chimbombo (Central), with three deals each. When looking at these land deals, it may appear as if the large-scale land deals were evenly made across the country. However, when one looks at the land deals made by province, it is possible to see that more than half were made in the Central, Southern, and Copperbelt provinces. For instance, the province where the most land deals were made during the period of 1970–2020 was the Central province (20 deals), followed by Southern (14 deals), Copperbelt (nine deals), Northern (eight deals), Lusaka (six deals), Luapula (five deals), North-Western (five deals), and Muchinga (three deals); see Table 3.

Table 3.

Large-Scale Land Deals made in Zambia, by province and district (1970–2020) [11].

Table 4 presents 13 large-scale land deals made during the period of 1970–2020 where land-grabbing incidences occurred. Most land-grabbing incidences occurred in Serenje district, which is in the Central province. In fact, 11 out of 13 land-grabbing incidences occurred in the Central, Copperbelt, and Southern provinces, where the most land deals were made; see Table 3.

Table 4.

Large-Scale Land Deals with land-grabbing cases (1970–2020) [11].

All 13 land deals were concluded after the year 2000, except for case 2021, which failed in negotiations in 2011. In all 13 land deals, the displacement and eviction of local people, insufficient compensation for those who had to move away from their land, and land degradation occurred. For instance, in the case of land deal 4797, half of the villagers of Mugoto Village in Mazabuka District (142 people) were displaced as the Munali Nickel Mine (MNM)—which is now owned by the British company named Consolidated Nickel Mines (CNM)—came to their land to mine nickel. Each displaced family received 3373.40 USD as compensation, but leaving the place where they had lived for generations was devastating for them. According to Henry Machina—a land rights activist from the Zambia Land Alliance—this is a classical case, where poor people have no power and end up losing their livelihood as the laws do not protect them [34].

One of the common features in these land deals (except for cases 4797 and 5123) was that the intention of negotiation was food crop cultivation. It should be emphasized that cases 2021, 2401, 3783, 5892, 5895, and 5896 were all connected to the Farm Block Development Program (FBDP), which is the Zambian government’s agricultural project. In 2002, the Zambian government approved the FBDP, which was earmarked for agricultural investment in 11 farm blocks. Each farm block was divided into four categories, namely, ‘core venture’, ‘commercial farm’, ‘emergent farms’, and ‘small-scale farms’. The core venture was a large-scale corporate interest that was allocated 10,000 ha of land. In turn, commercial farms (1600–4000 ha), emergent farms (50–900 ha), and small-scale farms (10–50 ha) are linked to the core venture [35].

In each farm block, the Zambian government had committed to investing into public services such as electrification, health clinics, roads, schools, water, and so on. Such commitment was intended to stimulate or attract sustainable partnerships with private sector investors in conducting agricultural, agri-business, and economic activities [36]. The starting point of the FBDP goes back to 1996, when the Zambian government established the Zambia Development Agency (ZDA) with the intention to facilitate the transfer of customary areas to foreign investors through the farm block concept. The ZDA put efforts into ensuring the fast endorsement of licenses by government departments, supporting the securing of work permits for foreign workers, and assisting in the acquisition of land for commercial ventures, being connected to Foreign Direct Investment [37]; in other words, it was the Zambian government who tried to attract the private investors which brought about the starting point of many cases of land grabbing connected to the FBDP. In fact, all of the land deals connected to FBDP involved either foreign operating companies or the Zambian operating companies with a foreign partner company as investors, who were invited and supported by the Zambian government, and resulted in the displacement of the local people; see Table 5.

Table 5.

Land Deals Connected to FBDP and Operating Companies and Investors [11].

For instance, Nansanga Farm Block, regarding cases 2021 and 2401 in Table 5, was one of the first farm blocks to be developed under the 2005–2006 FBDP. The Nansanga farm block consisted of one core venture (9350 ha) and three commercial farms (1620 ha, 2571 ha, and 3959 ha). While preparing for the block, the Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operative (MACO) decided to allocate the best land along the river to the large-scale commercial venture, which resulted in 43 families who occupied this land having to relocate to another area of the farm block [38]. Furthermore, although the government officially set aside 30% of the small-scale farms for the vulnerable population and women, the high and non-refundable application fees (roughly 50–700 USD) made it impossible for small-scale farmers to participate in this program. In fact, the creation of Nansanga farm block resulted in the eviction of 9000 local residents who were unable to meet the application requirements to acquire land in the block [35].

The Kasary Kuti Ranch, regarding case 5896 in Serenje district (see Table 5), is a 264 ha farm in the Ntenge section of the Luombwa farm block. Kasary Kuti Ranch is also known as Jackman Farm, after its owner Philip Jan Jackman. The Serenje District Council approved this farm application in 2014. In the following year, the Ministry of Lands issued an offer letter and, in 2016, the Ministry issued a certificate of title to the owner. During the process of obtaining the certificate of title, the Kasary Kuti Ranch sued the local people, as it saw them as squatters with no land rights. The local people then submitted land occupancy documents to the court, but the judge ruled in favor of the commercial farmers and ordered the families to be evicted. As a result, 12 families of the Ntenge community were displaced, but many of them remained on the land to appeal against the eviction [39,40].

There are some cases where justification was made for the displacement of the community. For instance, Billis Farm Limited, regarding case 5895 (see Table 5), is in the Milumbe area of Luombwa farm block in Serenje district. They registered the company in 2011 and purchased the farm from another private corporation in 2012; this farm covers 2071 ha. In July 2012, Billis Farm Limited and Abraheam Lodeikus Vileoen (a parent company) came to the concerned area and told the local people that they had paid the government to take over the land. In 2013, Abraheam Lodewikus Vileoen came back to the land with workers and bulldozers and destroyed the local people’s houses, trees, and crops. As a result, 65 local people were forcibly evicted and fled into the Musangashi Forest Reserve. The evicted people asked the Serenje District Commissioner’s Office and the Permanent Secretary for Central Province for help, but all they received was a month’s supply of food and tents, without any help regarding getting their land back [41]. The District Commissioner, Francis Kalipenta, who took office in 2016, found out that the evicted people were still waiting on the government for land; however, his office had no capacity to find land for them. As a result, the Commissioner told the evicted people to talk to their local chief regarding this matter [39].

In 2017, the evicted community members filed their case in Lusaka High court. They challenged their eviction, destruction of their houses and assets, and taking of their land which they claimed according to customary land rights. More specifically, the community argued that the commercial farmers, businesses, and the government of Zambia had violated their rights, as these respondents had turned their customary land into state land and allocated their land without consulting them. Furthermore, they argued that the respondents taking their land amounted to compulsory acquisition without sufficient amount of compensation, and not for a public purpose [41]. The judgement was delivered in favor of the evicted community in 2020; however, it is still unclear whether they have earned back their land or received any type of compensation.

As can be seen from above, most land deals made during the period of 1970–2020 in Zambia were concentrated in customary land near the Central, Southern, and Copperbelt provinces. Furthermore, all of the land-grabbing incidences occurred in these three provinces were strongly connected to the FBDP, which was initiated by the government of Zambia. Although it is true that foreign actors (e.g., investors and companies) took parts of land, especially within the FBDP, resulting in the displacement of the local people, it can be seen that the land-grabbers include ‘insiders,’ such as the government of Zambia, the Ministry of Lands, and the Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operative. In addition, it was found that individuals using off-farm income, especially those from the public sector, acquired large tracts of emergent farm areas. This group, usually from urban areas, does not have any previous farming experiences, but has acquired land titles in emergent farm areas. In this sense, these Zambian ‘elite groups’ are also land-grabbers as they push local farmers away from emergent farm areas by acquiring land titles [35]. Thus, land grabbing in Zambia can be described as ‘accumulation by dispossession,’ as offered by Harvey [18]. Additionally, as the government could easily lease land to the investors without consulting the local people, and the investors could directly pay the government and take customary land, it seems clear that the (customary) land rights of the ordinary Zambians are weak and insufficiently protected by the law. Thus, analysis of the historical roots of such weak customary land rights in the context of land law seems necessary, in order to understand land-grabbing behaviors in Zambia.

4.2. Historical Changes of Customary Land Rights in Zambia

4.2.1. Pre-Colonial Period

Until around AD 300, when the Bantu began to settle around the area of modern Zambia, the region was inhabited by the Khoisan and Twa people [42]. In the 12th century, Bantu-speaking people arrived in the region during the Bantu expansion. Among these people, the Tonga people were the first to settle in Zambia. During the early Bantu expansion, the Nkoya people—coming from the Luba-Lunda Kingdom, which was in the southern parts of the modern Democratic Republic of the Congo—arrived in Zambia. Later, in the early 18th century, the Nsokolo people settled in Mbala district, which is in the northern province of Zambia today. Further, in the 19th century, the Ngoni and Sotho people came to Zambia [43].

As can be seen from above, many different tribes have lived in Zambia. Even though there were different tribes, most of them traditionally lived under the customary land tenure system, and are still living under the same system. As mentioned earlier, about 90% of land in sub-Saharan Africa is held under customary land tenure [21,44]. In the case of Zambia, about 94% of its land is under a customary land tenure system [45].

Customary land tenure is sustained by the African communities and their customary law, rather than the state or state law [46]. Customary law can be referred to as rules with legitimacy rooted in tradition. Customary law often differs from one village to other in Africa, and its diversity arises from a range of cultural, ecological, social, economic, and political factors. Due to these various factors, customary law tends to continuously evolve throughout time [47]. Consequently, as the customary land tenure system is based on customary law, it also often evolves throughout time.

A customary land tenure system can be interpreted as a system which regulates the rights over each piece of land, including ownership, access to the land, right to cultivate it, withdraw produce, and transfer of the land [46,47]. As mentioned earlier, under the customary land tenure system, the ownership of land refers not to absolute ownership but, instead, to occupation and use [9]. Although the traditional chief or village headmen have the authority to control, distribute, and allocate land, the land does not belong to them [48]. It is often the case that land is held by groups, clans, and family; is accessed on the basis of membership; and is used according to complex systems of various rights [47]. Further, as land was often inherited by the future generation, Africans are not used to the idea of tenancy, land titling, or making profit by selling land [49]. This was also very much the case in Zambia. Accordingly, land rights came with membership or citizenship in a village. Such a membership was usually given or denied by a head or traditional chief of the concerned village [50]. Within the customary land tenure system, the links to persons through whom land was acquired and who could use the land are more important, rather than who has the rights to land [51]. Thus, customary land tenure is more like a social system, which is the de facto situation that constitutes the communally accepted rules one has to accept and follow to access and use land and other interests [52].

4.2.2. During the Colonial Period

Francisco Jesé de Lacerda, a colonial Brazilian-born Portuguese explorer, was one of the first European visitors to Zambia in the 18th century. In 1789, he planned a journey to the interior of Africa to establish a trade route between Portuguese holdings in Angola and Mozambique. However, he died in 1789, after arriving in the Kazambe kingdom (present day Zambia), where he planned to negotiate with the king on a trade route [43]. After his visit to the area, more explorers came to Zambia and the rest of the continent; one of the most prominent of these explorers was David Livingstone. Livingstone had a vision of ending the slave trade in the region, through Christianity, Commerce, and Civilization. His journeys to the continent motivated a wave of explorers, missionaries, and traders after his death in 1873 [43].

Livingstone met the Kololo people when he arrived at the Zambezi River. In the early 1800s, the Kololo people had run away from the Zulus in South Africa and arrived in the Zambezi River area. When they arrived in the area, they conquered all of the tribes in Western and Southern Zambia. However, the Kololo people did not rule the area for a long period of time. The chief of the Kololo, Sekeletu, suffered from leprosy and the people were dying from malaria. Thus, the Lozi people—the original tribe of Western Zambia—came back into power in the 1860s. The Lozi ruled most of Western and Southern Zambia and it was the king of the Lozi who could give permission to the European missionaries and settlers to settle in the region. The first foreign land deal took place in 1888, when the paramount chief gave the British South African Company (BSAC) mineral rights in the region. This area later became North Western Rhodesia [53].

Since then, the BSAC’s power over the land has grown. By the 1890s, the BSAC held administrative powers for areas under concessions from local chiefs. The BSAC particularly administered North Eastern Rhodesia and North Western Rhodesia, the protectorate status of which was established in 1895 and 1897, respectively [54]. These territories were administered by the BSAC, and the company amalgamated them into Northern Rhodesia (present-day Zambia) in 1911. For instance, according to the Northern Rhodesia Order in Council, 1911: “The Company shall from time to time assign to the natives inhabiting Northern Rhodesia land sufficient for their occupation, whether as tribes or portions of tribes, and suitable for their agricultural and pastoral requirements, including in all cases a fair and equitable proportion of springs or permanent water” [55] (p. 111). Thus, it can be said that the BSAC became the owner of Zambia’s land. More importantly, the land rights of the natives were diminished. For instance, “A native may acquire, hold, encumber, and dispose of land on the same conditions as a person who is not a native” [55] (p. 112). However, if the BSAC “should require any such land for the purpose of mineral development, or as sites of townships, or for railways or other public works, the Administrator, by direction of the Company, and upon good and sufficient cause shown, may, with the approval of the High Commissioner, order the natives to remove from such land or any portion thereof, and shall assign to them just and liberal compensation in land elsewhere, situate in as convenient a position as possible, sufficient and suitable for their agricultural and pastoral requirements, containing a fair and equitable proportion of springs or permanent water, and, as far as possible, equally suitable for their requirements in all respects as the land from which they are ordered to remove” [55] (p. 112); in other words, the natives could be displaced when the BSAC required their land.

The BSAC used the declaration of protectorate and its authority as administrator of the areas to claim vacant and unalienated land, which were labelled as wasteland [56,57]. The BSAC’s purpose in alienating wasteland was to preserve the most fertile land for the expected arrival of new European settlers. To achieve this aim, the BSAC tried to introduce native reserve land, in order to move the African natives and set aside large tracts of fertile land for free, to give to European settlers [58]. By 1913, the BSAC had established 19 provisional reserves for African occupation in the region [37].

In 1924, the BSAC handed over its administration of Northern Rhodesia to the Colonial office. The British Sovereign appointed Sir Herbert Stanley as the first governor of Northern Rhodesia. What should be emphasized in the year of 1924 is that the new Northern Rhodesia Government considered the idea of native reserves. Consequently, a Native Reserve Commission was appointed, and it recommended reserves for the Chewa, Ngoni, and Nsenga tribes. Africans then were mandated to move to the reserve (East Luangwa District Reserves) without any compensation [59]. Soon later, the category of native reserves was officially created for the settlement of African natives.

In 1928, the Northern Rhodesia (Crown Lands and Native Reserves) Order in Council, 1928, was promulgated. This Order in Council allocated mineral ownership to the BSAC and created two categories of land in Northern Rhodesia: crown land and native reserves. Crown land was vested in the Governor of Northern Rhodesia, and was administered by English statutes and set aside for Europeans. Crown land was held as either freehold or leasehold. The use of land and conveyance were governed by common law [56]. This meant that the settlers registered their land rights. On the other hand, native reserve land was administered by local customs, customary law, and was for African natives to use [60]. It was also clearly stated, in the Order in Council, 1928, that native reserves were “for the sole and exclusive use of the natives of Northern Rhodesia” [61] (p. 2219). However, despite the statement that native reserves were preserved exclusively for the native Africans, they had only surface rights of the land. More importantly, though native reserves were stated as the land for the native Africans, non-native Africans (Europeans) were allowed to lease native reserve land for a period not exceeding five years. For instance, it was stated in the Order in Council, 1928, that: “Any person recognized by the Governor or by a duly authorized officer on his behalf as being entitled to the exercise of mineral rights within a Native Reserve may enter upon land within that Native Reserve together with other persons employed by him for the purpose of exercising such rights, and may exercise the said rights subject to the terms of the Mining Proclamation and the general laws and regulation from time to time in force in Northern Rhodesia” [61] (p. 2220). In fact, the land rights of native Africans did not seem fully secured in native reserves.

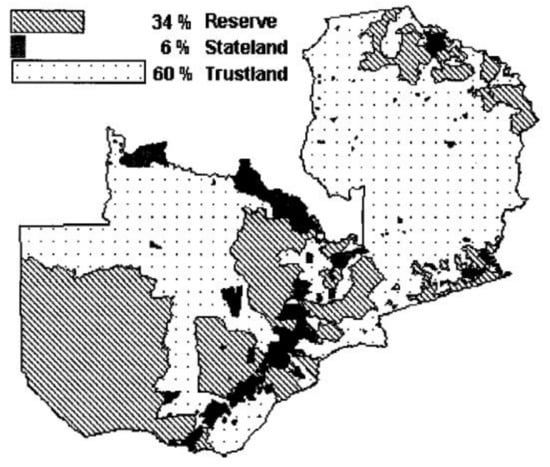

Dividing crown land and native reserves also led to other problems. As crown land was for Europeans, it was much more fertile and mineral-rich. For instance, as presented in Figure 2, crown land included a stretch of land along the railway line, which connected the Southern Province to the Copperbelt Province along the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo. On the other hand, native reserves were on the edges of European farming areas, which usually consisted of less fertile land. It was created for the native Africans who had been displaced by the demarcation of crown lands, but also to provide a ready supply of labor [62].

Figure 2.

Distribution percentage of crown land, native reserve, and trust land during the Colonial era in Zambia [63] (p. 3).

Further, as more native Africans were forced to move to the native reserves, they were becoming overcrowded and the native Africans complained about soil erosion, which was making their livelihood even worse [37]. This led to the setting up of the Pim Commission of 1938, which led to the proposal for more land for the native Africans (named native trust land). The idea of native trust land was accepted in 1941. The colonial government proposed to introduce legislation in all land in Northern Rhodesia which had not been set aside for native reserves or alienated. Then, the land was to be divided into two categories: crown land and native trust land [57]. Native trust land was made up of all unassigned land (e.g., forests, game land, and unused crown land) [60]. In 1947, the Colonial Government passed the Northern Rhodesia (Native Trust Land) Order in Council, 1947, and land was divided into crown land, native trust land, and native reserves. Native trust land was created to resolve the over-population problems in native reserves [64].

Native trust land and native reserves shared many similarities. Like the native reserves, native trust land was to be occupied and used by the native Africans, and was administered by local customs and customary law. In both lands, non-natives could be granted land; however, there was duration difference, as non-natives could be granted land in native reserves for five years, whereas it was 99 years in native trust land [65]. What should be also emphasized is that, although native trust land was supposed to be land for native Africans, it was the Governor of Northern Rhodesia who (re)distributed land in the concerned area [66]. Furthermore, unlike the European settlers in crown land, native Africans could not register land titles in both native reserves and native trust land. In other words, the land of native Africans could still be taken away whenever the Governor of Northern Rhodesia demanded.

Before the commencement of the Northern Rhodesia (Native Trust Land) order in Council, 1947, about 93.3% of Zambian land was native reserves and unused land. After the commencement, native reserves and native trust land covered about 97% of Zambian land [67,68]. Thus, 97% of the land was supposed to be the land for native Africans. The colonial government acted generous, and left the native Africans to live under their traditional life style (e.g., customary law and customary land tenure system); however, the truth is that the native Africans never had their own land, as the colonial government always had the control of customary land. Furthermore, the colonial government utilized the Western system of land titling to secure the land rights of European settlers, but which was not made applicable to the native Africans. Thus, during the colonial era, the native Africans had almost no chance of securing their land rights. Furthermore, as the native trust land consisted of forest and unused crown land, it can be suspected that the environmental condition of the native land (e.g., fertility) was not sufficient for the native Africans to make extra earnings but, instead, only allowed them to concentrate on subsistence farming for survival.

4.2.3. After Independence

Zambia gained independence in 1964 and the United National Independence Party (UNIP), led by the president Kenneth Kaunda took power. The UNIP found that there was an urgent need to change policies regarding land, as the colonial land policies were discriminatory towards Zambians. According to the Zambian government, there was a need for land reform as “the previous administrations… were discriminatory in that (until about two years before independence) one had, in general, to have a white skin before one could acquire a piece of land on State Land and provided his skin was of a dark pigmentation his only resource was in the (Native) Reserves or (Native) Trust Lands, which were far from markets, badly served by communications and transport and in some area infertile, tsetse fly infested and lacking in water. These policies were seen as an economic colour-bar of a subtle nature” [69] (p. 143). Thus, during Kaunda’s regime, it may have appeared that land was going to become the property of the ordinary Zambian people solely. Land was not to be alienated for private gain during his regime, and only small-scale private property was permitted and large-scale enterprises (e.g., agricultural, commercial, industrial, or financial) had to be undertaken by the state or institutions controlled by the state [67].

The Kaunda government decided to adopt a one-party system in 1972, which led to the amendment of the constitution in the same year. This was driven by the government desire for a socialist political ideology. Regarding land, Kaunda made it state property. His idea was that “Land, obviously, must remain the property of the State today. This in no way departs from our heritage. Land was never bought. It came to belong to individuals through usage and the passing of time” [70] (p. 14). In line with this idea, the Kaunda government introduced the Land (Conversion of Titles) Act 1975. In this Act, it is stated that “every piece or parcel of land which immediately before the commencement of this Act was vested in or held by any person-(a) absolutely, or as a freehold… or in any other manner implying absolute rights in perpetuity; or (b) as a leasehold extending beyond the expiration of one hundred years from the commencement of this Act; is hereby converted to a statutory leasehold and shall be deemed to have been converted with effect from the first day of July, 1975” [69] (p. 145). The Act basically abolished the freehold tenure system. The existing freeholds were converted to leaseholds of 100 years. Furthermore, unutilized land and land without landlords were expropriated by the state. As bare land could not be sold in the market unless one is to develop land, the value of vacant land diminished. The estate agency was abolished, as it had been accused of inflating prices on vacant land and other types of properties [71]. Furthermore, the president’s consent was required in all land dealings, which was to provide strict conditions to control ownership of land by foreigners [67]. The negative result of this Act was that the restriction of operation of the land market led to high property values and hindered property investment. Furthermore, foreign farmers and investors who were not interested in developing land began to leave the country [60].

The attempt by the Kaunda regime to prevent large foreign companies from taking land may have psychologically comforted the ordinary Zambian; however, it would be wrong to conclude that the ordinary Zambian’s customary land rights became more secure during Kaunda’s regime, as the Land (Conversion of Title) Act 1975 was only applicable to state land. In other words, the Land (Conversion of Title) Act 1975 only functioned to protect those who lived in the state land of foreign actors. In fact, there was little change in the customary land rights of the people living on customary land. The Kaunda regime inherited the colonial land law with a minimal change; for example, the land categorization made during the colonial era, including crown land, native reserve land, and native trust land, were changed to state land, reserve land, and trust land, accordingly. The reserve land and trust land that were vested in the Secretary of State (British) were now vested in the president. State land was also vested in the president, instead of Her Majesty [72,73]. In other words, only the ‘owner’ of the land changed, from the colonial government to the Zambian president, without making any change to secure the customary land rights.

More specifically, during the Kaunda regime, the administration of reserve land was governed by the Zambia (State and Reserves) Order 1928 to 1964. Under these orders, reserve land was set apart for the exclusive use of ordinary Zambians; however, the president could make grants of land to Zambians and rural councils for 99 years. In the case of trust land, under the Zambia (Trust Land) Order 1947 to 1964, the president could grant a right of occupancy to a non-Zambian for up to 99 years, and demand rent for the use of the land. Further, non-Zambians were allowed to own land titles if they qualified as investors or were approved by the president. Thus, although there was the Land (Conversion of Title) Act 1975 to protect the state land, the customary land rights of the ordinary Zambians living in the reserves and trust land were not secured legally, as the laws continued to be interpreted in light of the colonial government’s orders [67].

As mentioned before, since the commencement of the Land (Conversion of Title) Act 1975, the restriction of the operation of the land market hindered property investment and foreign investors lost their interest in investing in Zambia, as all land dealings became strict [60,71]. However, since 1991, when the Movement for Multi-party Democracy (MMD) government of President Fredrick Chiluba came into power and the country reverted from the one-party rule to a multi-party state, there has been a dramatic change in land policies. The MMD government, in its manifesto, called for land policy reforms by stating that “the MMD shall institutionalize a modern, coherent, simplified and relevant land law code intended to ensure the fundamental right to private ownership of land…… To this end an MMD government will address itself to the following fundamental land issues. A review of the Land (Conversion of Title) Acts of 1975…… the Trust Lands and Reserves Order-in Council of 1928–1947…… in order to bring about a more efficient and equitable system of tenure conversion and land allocation in customary lands; land adjudication legislation will be enacted and be co-ordinated in such a way that confidence shall be restored in land investors…… the MMD government will attach economic value to undeveloped land, encourage private real estate agency business, promote regular issuance of title deeds to productive landowners in both rural and urban areas……” [68] (pp. 33–34); in other words, the MMD promoted private ownership of land by farmers, entrepreneurs, and investors, which was the complete opposite of the UNIP’s concept of land without value.

The MMD held a national conference on land reform in 1993, and it was proposed that reserve land and trust land be merged into one category: customary land. Furthermore, it was proposed that state land remained the same, with 99 years of leasehold tenure. Regarding the price of land, it was recommended that market forces should determine the price of state land; on the other hand, the price of customary land was recommended to be left to evolve, according to the conditions of rural areas [57].

After two years of continuous discussion, the Land Act 1995 was commenced. Although this act repealed The Land (Conversion of Titles) Act 1975 and other land Acts, all land in Zambia is still vested in the president. The state land remained as it was, and trust land and reserve land were merged into ‘customary area’. When one analyzes the Land Act 1995, it may appear as though the customary land rights had become more secure. For instance, according to the Land Act 1995, “The President shall not alienate any land situated in a district or an area where land is held under customary tenure- (a) without taking into consideration the local customary law on land tenure which is not in conflict with this Act; (b) without consulting the chief and the local authority in the area in which the land to be alienated is situated, and in the case of a game management area, and in the case of a game management area, and the Director of National Parks and Wildlife Service, who shall identify the piece of land to be alienated; (c) without consulting any other person or body whose interest might be affected by the grant; and (d) if an applicant for a leasehold title has not obtained the prior approval of the chief and the local authority within whose area the land is situated” [74] (pp. Part II (4)); furthermore, ordinary Zambians “who hold land under customary tenure may convert it into a leasehold tenure not exceeding ninety-nine years on application” [74] (Part II 8 (1)). The Zambian government’s explanation of this provision was that, by converting customary land holdings to leasehold, Zambians can reduce the uncertainty regarding titles and use their land as collateral to secure credit to invest in farms and businesses [56,75]. It must be noted that, as customary land tenure and rights are based on customary law and not state law, the customary land tenure system has been viewed by many scholars as antiquated, backward, and insecure, and does not promote the land and credit market due to the lack of clarity around ownership [76,77,78,79]. On the contrary, a title deed has the potential to reduce the costs of disputes and litigation, as it facilitates easy identification of boundaries and owners of land. Thus, the possession of a title deed is seen as the most reliable way for an individual to prove ownership and enjoy their tenure security, which can be regarded as a way to secure customary land rights [79]. Furthermore, in theory, privatization of customary land rights strengthens security of tenure by accelerating the issuance of title deeds, stimulating investment in land, increasing agricultural productivity, promoting land markets, and increasing access to formal credit. These potential outcomes can contribute to the overall economic growth of a country [78,80].

However, it would be insufficient to conclude that the customary land rights of ordinary Zambians can be secured just because they are allowed to convert their customary land holdings into lease holdings, as the cost of converting customary holdings to leasehold titles is too high for ordinary Zambians. In order to acquire an initial lease, all applicants first must secure the permission of the chief and district council, and must hire a surveyor to draw a sketch map of the land and pay lease charge, which are at least about 100 USD [56]. For instance, the initial cost of a land survey to determine the position of township controls or reference mark under 1000 m2 is 1087.2 Kwacha, which is about 61 USD [81,82]. Furthermore, as a claimant needs to travel to the district headquarters and the Ministry of Land offices in Lusaka or Ndola repeatedly during the process of securing lease, additional travel costs will be incurred. Accordingly, if a claimant lives far away from Lusaka or Ndola, the travel fee may become enormous. Once the land is converted, one must pay an annual ground rent to the Ministry of Lands; in other words, one has to pay rents for the land where they have lived for a long period of time, becoming a tenant of their own land. For instance, in Zambia’s Lusaka, Copperbelt, Central, and Southern provinces, the annual ground rent fee for less than 1 ha is 1999.8 Kwacha, which is about 112 USD [83]. Furthermore, as the cost of converting is too high, it is likely that only wealthy Zambians, politicians, or foreign investors can afford to pay these fees, which could widen land inequality [56].

In fact, the Land Act 1995 did not bring about more secure customary land rights but, instead, a legal environment under which foreign investors could lease land easily. According to the Land Act 1995, the President may alienate land to a non-Zambian under the following circumstances: “(a) where the non-Zambian is a permanent resident in the Republic of Zambia; (b) where the non-Zambian is an investor within the meaning of the Investment Act or any other law relating to the promoting of investment in Zambia; (c) where the non-Zambian has obtained the President’s consent in writing under his hand” [74] (Part II 3 (3)). In other words, whilst the Kaunda regime attempted to put more strict conditions on land ownership by foreigners, Chiluba’s regime opened up the market for land to foreign investors. As analyzed in Section 3.1, the FBDP is a classic example of the Land Act 1995 bringing about great opportunities for the foreign investors to lease customary land, often resulting in land grabbing. In fact, it is possible to see an argument that the main purpose of the Land Act 1995 was to reduce the size of land in the hand of communal tenancy (customary land), and make more land available for investments [37]. Furthermore, although the Lands (Amendment) Act, 2010, and Lands (Amendment) Act, 2015, have been introduced, these new acts do not have much impact on the Land Act 1995, regarding the securing of customary land rights.

By looking at the changes in land laws, it can be seen that the customary land tenure system itself never really changed. However, since the colonial period, the customary land became the location to force the Zambians to move to, in order to make room for the British and the European settlers in crown land. Even though customary land was described as “for the Zambians”, the actual owner of the customary land was always the British. The colonial government acted as if they were respecting Zambian custom by allowing them to live under customary law; however, this ‘generosity’ can be interpreted as manipulation of the customary land law and tenure system. Although it was posed as respectful to Zambian custom, it led to weak (customary) land rights, by not giving them a chance to register their land. After independence, the weak customary land rights and the usage of customary land never really changed. During Kaunda’s regime, although the government recognized that the colonial land laws were discriminatory towards the Zambians living on customary land and the environmental conditions of such land was very poor, nothing was really done to strengthen the customary land rights, nor were any parts of the fertile land (i.e., state land) given back to the ordinary Zambians. Since the Chiluba regime up to the present day, the Land Act 1995 seems to secure customary land rights by providing the chance to convert it to leasehold tenure; however, ordinary Zambians are generally unable to pay for the process of converting their land rights to leasehold. Thus, even after independence, the land rights of the Zambians living on customary land have never really been secured.

5. Conclusions

Most research on land grabbing in Africa has pointed at Western countries and investors as land-grabbers, as they tend to lease large areas of land on the continent to grow food and biofuel crop to meet their needs. Furthermore, Africa’s weak customary land rights, or customary land tenure system, are often seen as one of the main factors leading to the displacement of ordinary African people. By analyzing land-grabbing cases in Zambia, this research aimed to determine the different actors involved in land grabbing in more depth, as well as to understand the factors leading to weak customary land rights of the ordinary Zambians which resulted in such land grabbing.

By collecting and analyzing the land-grabbing cases in Zambia, it was found that most land deals had been made in the Central, Southern, and Copperbelt provinces. These provinces are the areas where crown land and reserve land were situated during the colonial period [11,63]. The fact that land deals were made near state land (previously crown land) and its surrounding areas (customary land) means such land deals were made in the most profitable (e.g., good agricultural environment and mining) areas. This resembles the land acquisition pattern (in terms of location) during the colonial period, in which the British government and European settlers acquired the most profitable land. What is more important is that most land-grabbing incidences also occurred in the Central, Southern, and Copperbelt provinces. Among such land-grabbing incidences, there were cases in which the Zambian people were displaced by the foreign investors who had leased the land. However, when looking at each land-grabbing case more specifically, the Zambian government’s own agricultural programs (e.g., the FBDP) had invited the foreign companies to invest in their land, ultimately resulting in the displacement of ordinary Zambians. Thus, although the foreign companies and investors may have physically taken over and used the customary land, the actual factor that led to the displacement of the Zambians was often the government’s invitation to the foreign companies to develop the customary land. Thus, the land grabbing in Zambia involves various land grabbers, and should be described in connection with Harvey’s ‘accumulation by dispossession’ [18].

By analyzing the changes in customary land usage and land rights, it could be determined that the customary land tenure system (or customary land rights) itself cannot fully explain the land-grabbing behavior in Zambia. During the colonial era, registering the land rights of individuals was mostly applied to crown land, and such registration was only applicable to European settlers and British colonizers. The Zambians were forced to move to native reserves and trust land, and were not able to register individual land titles. Furthermore, the native reserves and trust land were never their land, as these lands were under the control of the Governor of Northern Rhodesia. Despite the fact that the size of the customary area was much larger than crown land, the Zambians were living in environments where the land was much less suitable for producing extra earnings (e.g., less-fertile land), compared to the foreign actors, as the British and the new settlers took most of the profitable land (crown land). Thus, not only could the Zambians not gain individual land rights, but also, it was hard for them to accumulate wealth through large-scale or commercial farming, due to the harsh environment.

After independence, the Kaunda government emphasized the colonial discrimination towards Zambians by sending them to customary land. However, the Kaunda government made little change to the land categories and inherited the colonial land laws; they only made it difficult for foreign investors to lease land in state land by commencing the Land (Conversion of Title) Act 1975. The Kaunda regime did not take any action on strengthening customary land rights, nor redistributing more fertile land (now state land) to the ordinary Zambians. The ordinary Zambians still could not register their land titles, and were living in the same harsh environment (reserve land and trust land) as before.

In 1995, the Chiluba Government brought about changes in customary land rights, as the Land Act 1995 allowed the customary tenure to be converted into leasehold tenure, which meant that ordinary Zambians living on customary land can register and strengthen their individual land rights. However, the total registration fee for converting customary tenure into leasehold tenure is too high for the ordinary Zambians living on customary land, whose annual income is about 300 USD [56,84]. This could be the result of the inequality between state land (crown land) and customary land (native reserves and trust land) created during the colonial period and continued today, as the people living on customary land were not in a condition to accumulate wealth for a long period of time. If the state land wealth had been re-distributed to the people living on customary land, they could have created the wealth to register their land rights. Such an inequality is evident, as over 90% of the people who obtained title deeds on customary land are individuals from urban centers (mostly state land) [69]. Further, the combination of the Land Act 1995 and the government’s agricultural development programs (e.g., FBDP) played a role in favoring foreign investors, who were invited by the government to invest in the country. These foreign investors have the technology and wealth to pay for leasing the land. Thus, the land of ordinary Zambians has been slowly diminished and their customary land rights—despite their right to convert it to leasehold—have been slowly fading. In fact, as ordinary Zambians and Africans cannot afford to register their land titles, it is possible to find studies stating that customary land tenure systems are more promising for obtaining land rights, compared to going through official registration [85].

By looking at the results, it appears that the continuing land laws based on the dual-tenure system implemented by the colonial era up to the present day seem to be the main cause of land grabbing in Zambia. This dual system has mostly allowed for securing the land rights of those living on state land (e.g., the government and wealthy Zambians), as well as foreign investors. Such a continuous dual-tenure system, along with the poor environmental conditions in customary land, has never benefited the ordinary Zambians living on customary land and has not allowed them to be financially ready to register their land titles. This combination has led to land-grabbing incidences and the displacement of ordinary Zambians. It must be noted that further research on financial inequality between those living on state land and those living on customary land is needed in the future to support the findings of this study. In addition, the findings of this study should be complemented by interviews and focus group discussions conducted with ordinary Zambians who were displaced from key land grabbing areas and who remained there by registering their land titles. The field work will be essential as it will help to find more detailed factors that lead to land grabbing in Zambia. In addition, although there is a substantial body of literature on the land-grabbing issue, including the Zambian case, there is a lack of theory in land grabbing that could be used for systematic and meaningful research [86]. Therefore, future studies of land grabbing must aim at developing a sound theory.

For now, the most realistic method to prevent ordinary Zambians from becoming victims of land grabbing is to find a realistic way for them to register land titles, as the Land Act 1995 is still applied in the country. In order to do this, the Zambian government should come up with a reasonable registration fee for the ordinary Zambians living on customary land for generations, finally allowing them to convert their land to leasehold and also developing a feasible annual ground rent for them. In the long term (or, perhaps, it should happen sooner), the Zambian government should separate (agricultural) development aspects from land laws. This is because considering development aspects in the land laws, as was set during the colonial period, seems to render the land rights of ordinary Zambians unimportant. In other words, development has been more prioritized than the ordinary Zambians. Separating the development aspects from land law will be a crucial step in truly moving away from the colonial influence or legacy, which can be expected to bring about more secure customary land rights and prevent land grabbing in Zambia.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Institute of African Studies (IAS-HUFS) for providing academic facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Borras, S., Jr.; Franco, J. From Threat to Opportunity? Problems with the Idea of a “Code of Conduct” for Land-Grabbing. Yale Hum. Rights Dev. Law J. 2010, 13, 507–523. [Google Scholar]

- Borras, S.-M., Jr.; Franco, J.-C. Global Land Grabbing and Trajectories of Agrarian Change: A Preliminary Analysis. J. Agrar. Chang. 2012, 12, 34–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batterbury, S.; Ndi, F. Land-grabbing in Africa. In The Routledge Handbook of African Development; Binns, T., Lynch, K., Nel, E., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 573–582. [Google Scholar]

- GRAIN Releases Data Set with Over 400 Global Land Grabs. Available online: https://grain.org/article/entries/4479-grainreleases-data-set-with-over-400-global-land-grabs (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- The Global farmland grab in 2016: How Big, How Bad? Available online: https://grain.org/article/entries/5492-the-global-farmland-grab-in-2016-how-big-how-bad (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- World Development Indicators. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Acheampong, E.; Campion, B.-B. The Effects of Biofuel Feedstock Production on Farmers’ Livelihoods in Ghana: The case of Jatropha curcas. Sustainability 2014, 6, 4587–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.J. Displaced Community’s Perspective on Land-Grabbing in Africa: The Case of the Kalimkhola Community in Dwangwa, Malawi. Land 2019, 8, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.-J. Analyzing the Changes of the Meaning of Customary Land in the Context of Land Grabbing in Malawi. Land 2021, 10, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamchiya, P.; Gausi, J. Commercialisation of Land and Land Grabbing: Implications for Land Rights and Livelihoods in Malawi, Research Report 52, Plass. 2015. Available online: http://repository.uwc.ac.za/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10566/4504/rr_42_commercialisation_land_and_land_grabbing_malawi_2015.pdf?sequence=l&isAllowed=y (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- Land Matrix. Available online: https://landmatrix.org/map/ (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Burnod, P.; Gingembre, M.; Andrianirina, R. Competition Over Authority and Access: International Land Deals in Madagascar. Dev. Change 2013, 44, 357–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachika, T. Land Grabbing in Africa: A Review of the Impacts and the Possible Policy Responses; Mokoro: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- DIRECTIVE 2009/28/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources and Amending and Subsequently Releasing Directives 2001/77/EC and 2003/30/EC. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2009:140:0016:0062:EN:PDF (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Wahl, N.; Hildebrandt, T.; Moser, C.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Averdunk, K.; Bailis, R.; Barua, K.; Burritt, R.; Groeneveld, J.; Klein, A.-M.; et al. Insights into Jatropha Projects WorldWide Key Facts & Figures from a Global Survey; Centre for Sustainability Management (CSM): Lüneburg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Von Maltitz, G.; Gasparatos, A.; Fabricius, C. The Rise, Fall and Potential Resilience Benefits of Jatropha in Southern Africa. Sustainability 2014, 6, 3615–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaque, J. Environmental Governance in Europe and Asia: A Comparative Study of Institutional and Legislative Frameworks; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The New Imperialism; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D. Primitive Accumulation, Accumulation by Dispossession and the Global Land Grab. Third World Q. 2013, 34, 1582–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aart, V. Unravelling the Land Grab: How to Prott the Livelihoods of the Poor? Rabound University: Nijmegen, The Netherlands; Oxfam Novib: Hague, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chimhowu, A. The ‘New’ African Customary Land Tenure. Characteristic, Features and Policy Implications of a New Paradigm. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakari, Z.; Richter, C.; Zevenbergen, J. Exploring the “implementation gap” in land registration: How it happens that Ghana’s official registry contains mainly leaseholds. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpofu, B. The Contribution of Archie Mafeje to the Debate on Land Reform in Africa. Int. J. Afr. Renaiss. Stud. 2014, 9, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambia-Country Summary. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/zambia/summaries (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Population Density in Africa as of 2021, by Country. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1218033/population-density-in-africa-by-country/ (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Zambia The Draft Land Policy. Available online: https://mokoro.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/zambia_draft_land_policy_nov_2002.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Population. Available online: https://zambia.opendataforafrica.org/xmsofg/total-population (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Chileshe, R.; Shamaoma, H. Examining the Challenges of Cadastral Surveying Practice in Zambia. S. Afr. J. Geomat. 2014, 3, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Land Matrix. Available online: https://landmatrix.org/ (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Bhat, P.-I. Idea and Methods of Legal Research, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Comparative Legal History. Available online: https://www.maastrichtuniversity.nl/blog/2017/07/comparative-legal-history (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- Historical Approach to Legal Research. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336676844_Historical_Approach_to_Legal_Research (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- Land Matrix. Available online: https://landmatrix.org/charts/dynamics-overview (accessed on 27 August 2022).

- Ordinary Zambians Grapple with Land Grabbing. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/ordinary-zambians-grapple-with-land-grabbing/a-18764494 (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Sitko, N.-J.; Jayne, T.-S. Structural Transformation or Elite Land Capture? The Growth of “emergent” Farmers in Zambia. Food Policy 2014, 48, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strategic Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (SESA) Executive Summary. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Environmental-and-Social-Assessments/Zambia_-_Zambia_Staple_Crops_Processing_Zone__SCPZ__Luswishi_Farm_Block__Lufwanyama_District__Copperbelt_Province__Zambia_%E2%80%93_ESIA_Summary.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2022).