Residents’ Selection Behavior of Compensation Schemes for Construction Land Reduction: Empirical Evidence from Questionnaires in Shanghai, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- (i)

- Studies on the economic impact of CLR. CLR is a path innovation to break the constraint of tight construction land quotas [22] and meet the demand for construction land for economic and social development through the optimization of construction land use structure [6,7,8]. Some studies suggest that the positive effect of industrial land reduction on local fiscal revenue growth gradually increases over time [22]. One study analyzed the impact of homestead reduction on economic agglomeration and rural revitalization and found that homestead reduction can significantly increase the income of rural residents and promote industrial integration and rural economic development; moreover, this positive impact intensifies over time [23].

- (ii)

- Studies on the mechanisms of CLR. Some studies analyzed the impact of CLR on rural transformational development based on the grounded theory and concluded that resource allocation is the core impact of CLR on rural transformational development [15]. Some studies have also focused on the land marketization mechanism [24] and operation mechanism [25] in the CLR process, etc.

- (iii)

- (iv)

- Research on land consolidation issues. Land consolidation is the most complex, technical and important stage of land reclamation [27]. Land consolidation is a spatial planning process [28,29], and this process of reorganizing property rights is often the main cause of dissatisfaction and opposition to land remediation [30]. Land consolidation inevitably leads to changes in land ownership and adversely affects the interests of landowners steadily, thus leading to controversy and discontent [27]. Some studies focused on the barriers encountered in CLR to meeting the sustainability requirements of land use [31].

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

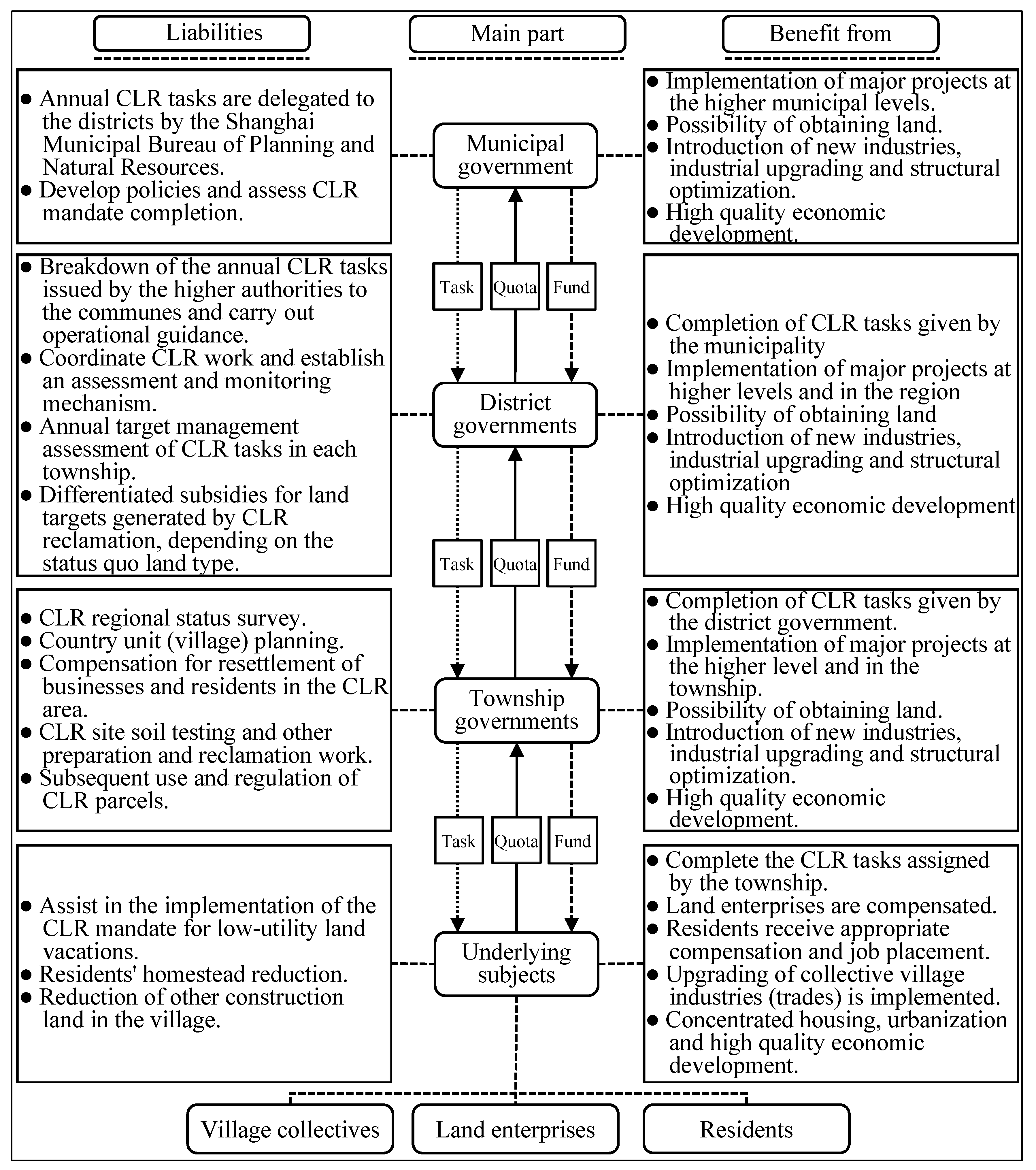

3.1. Task, Quota, Financial and Benefit Flows in the CLR Process

3.1.1. Task Flow and Quota Flow in the CLR Process

3.1.2. Financial Flows for Compensation in the CLR Process

- (1)

- The land quota of the land user or village is collected and stored in the township, and the land user or village collective will receive full compensation. The compensation comes from the township governments, including compensation funds from the municipal, district and township governments. It is used to compensate for the relocation of the site enterprise and other cost expenses of the village collective to carry out CLR.

- (2)

- For township quotas collected in the district, the townships receive compensation and any surplus is used for other CLR work. The compensation funds come from the district government, including compensation funds from both municipal and district governments and are only part of the cost of CLR.

- (3)

- For the district construction land quotas storage to the municipal government, the municipal government gives the district a subsidy of 450,000 CNY/mu (1 mu ≈ 0.067 hectares), and the shortfall is borne by the district and the township themselves. As industrial land is generally offered at low prices, the Government, in order to encourage the use of CLR quotas for the development of the real economy and industries, has increased the subsidy of 150,000 CNY/mu on top of 450,000 CNY/mu for each district to use the land quotas formed by CLR in the “198” area 3 for certified industrial projects. Moreover, the land quotas formed by the CLR in the “198” area are coordinated by the Shanghai Municipal Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources, and about 25% of the land quotas will be used for national and municipal projects. The municipal government does not subsidize the reduction of residential land.

3.1.3. Stakeholder Benefit Flows in the CLR Process

3.2. Compensation Scheme for the Loss of Development Benefits of NRACL in the CLR Process

3.2.1. Compensation Scheme I: Direct Financial Compensation in Situ

3.2.2. Compensation Scheme II: In Situ Enhancement of Development Capacity

3.2.3. Compensation Scheme III: Off-Site Enhancement of Development Capacity

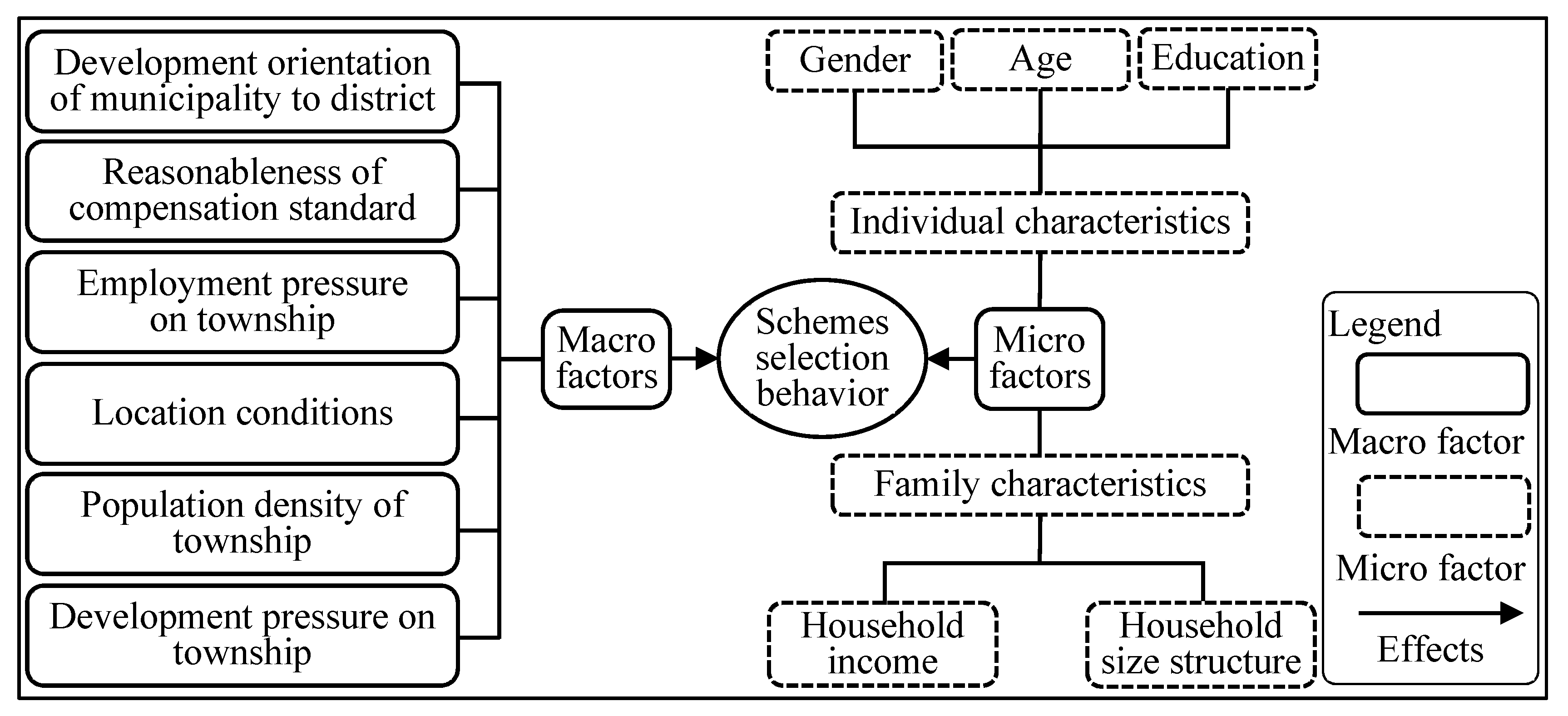

3.3. Factors Influencing the Behaviour of Residents in Choosing between the Three Compensation Schemes

3.3.1. Macro Factors

- (1)

- Development Orientation of Municipality to District

- (2)

- Reasonableness of Compensation Standard

- (3)

- Employment Pressure on Township

- (4)

- Location Conditions

- (5)

- Population Density of Township

- (6)

- Development Pressure on Township

3.3.2. Micro Factors

4. Research Methodology and Data

4.1. Model Setting

4.2. Selection of Variables and Indicator Measures

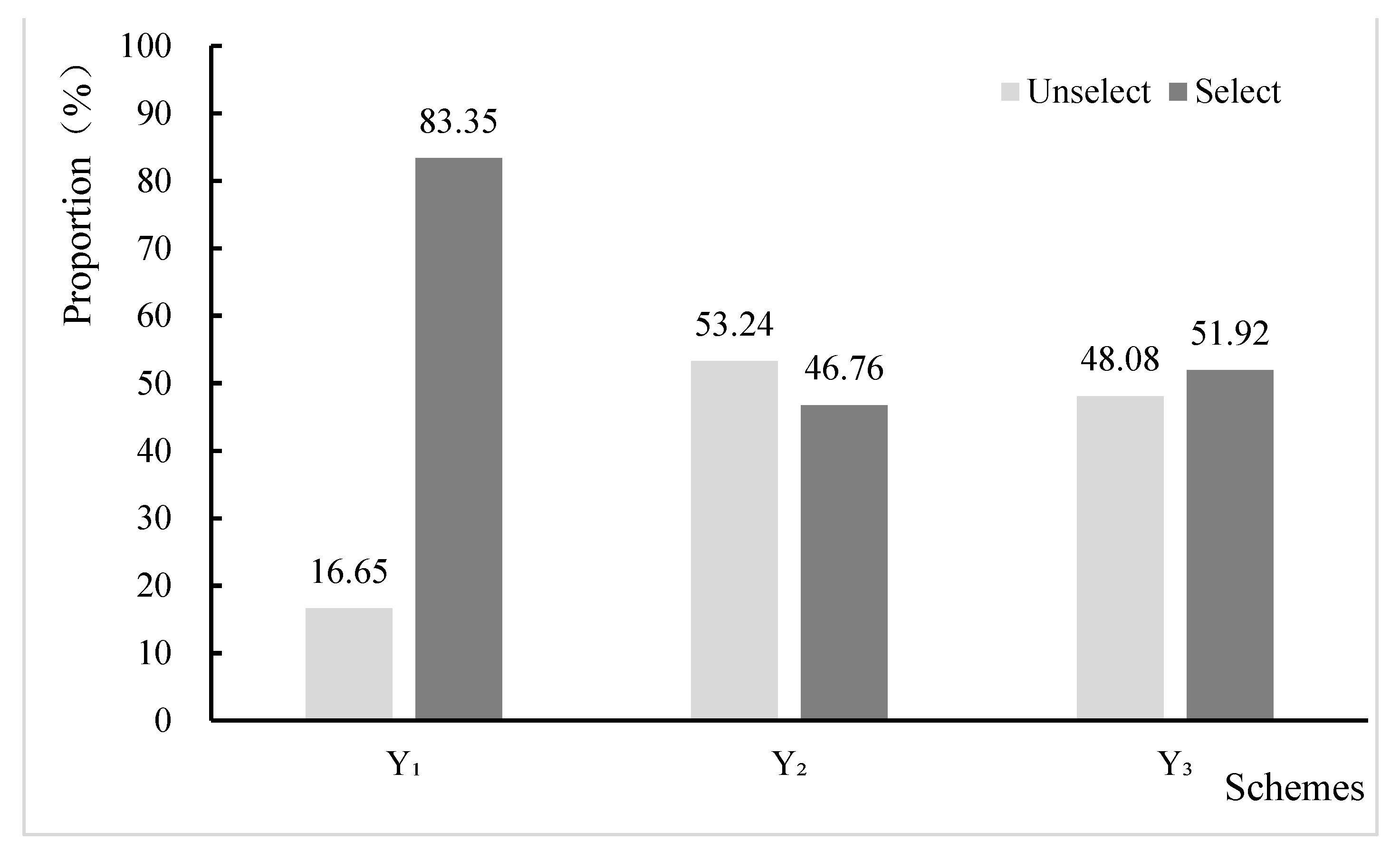

4.2.1. Dependent Variables

4.2.2. Explanatory Variables

4.3. Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics

5. Empirical Results and Analysis

5.1. Baseline Regression Results

5.1.1. Macro-Influencing Factors

- (1)

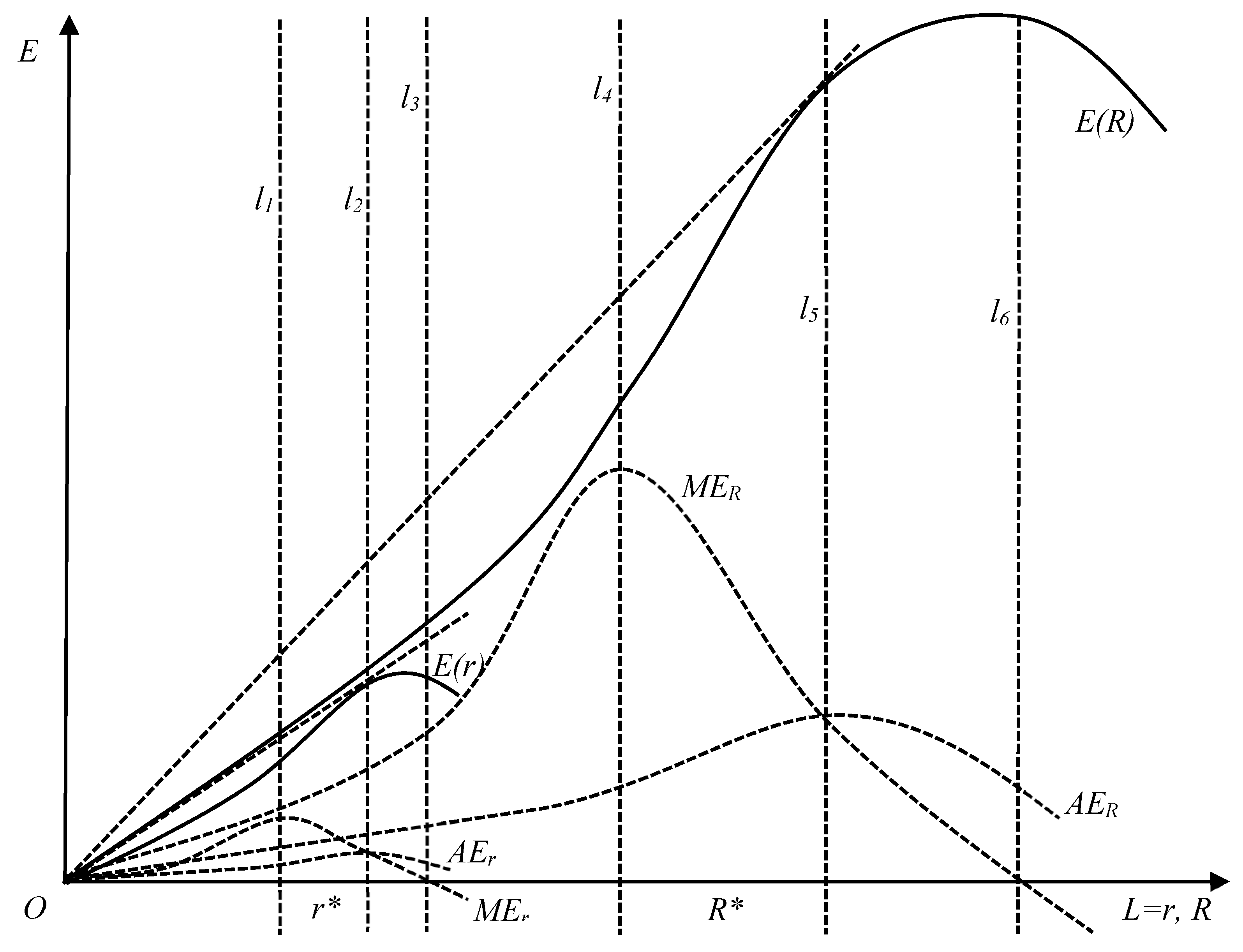

- The development orientation of the municipality to the district is not significant. The near-term plan is 2020–2025; the long-term plan is 2025–2035. The long-term plan has not yet been implemented. At this stage, the construction land used by the districts for development comes from the use of land quotas obtained from CLR for more efficient areas and from the renewal of the district’s stock of construction land, i.e., the upgrading of the capacity of the stock of construction land. Rather than CLR dominating economically developed areas in general, the pressure and incentive to renew construction land dominates. The existing system stipulates that 25% of the quotas after CLR in each district go to the municipal level, and the rest all goes to the districts for their own use. If the districts want more construction land quotas, they need to do more CLR. Such a provision is in conflict with the district-level development orientation. A coordination mechanism would be to plan for NIACL by increasing the CLR tasks and thus gaining more construction land use quotas. As shown in Figure 1, under the planned land use control, the allocation of construction land is “reduced to increase”, and the allocation of land quotas obtained from CLR is mainly coordinated within the district. The “reduction for increase” is realized to a greater extent at the district level. Therefore, the greater the proportion of the CLR-derived land quotas used for new construction land in the district, the more likely it is that the district as a whole is a construction land regeneration area so that residents are more concerned about the renewal of construction land in the district and less concerned about the CLR, which is probably why the development orientation of the municipality to the district does not have a significant influence on residents’ choice of schemes. Hypothesis 1 (H1) was verified. This is consistent with the relevant research on urban renewal [10,42,43]. Urban renewal has been an important strategic choice to promote urban development [10]. In contrast to NRACL, NIACL needs to address development challenges through urban renewal. There is a lack of attention to the reduction of construction land and its compensation.

- (2)

- Reasonableness of compensation standards significantly enhances residents’ choice of schemes I and III. Reasonableness of compensation standards helps to prompt residents to choose Scheme II, but this effect does not pass the 10% significance level test, which may be due to the fact that enhancing local competitiveness relies more on technical help from economically developed regions and the role of economic compensation is limited. From the current stage of CLR, the compensation to the relevant interest subjects is mainly economic compensation, and in the absence of other compensation, residents attach more importance to economic compensation. Thus, the more reasonable the compensation standard, the greater the likelihood that residents will benefit from the compensation, and thus this increases the number of residents who have a preference for Scheme I. If the compensation is more reasonable, then the residents expect more off-site employment, off-site development and improved living conditions, and thus the reasonableness of the compensation increases the residents’ preference for Scheme III. Hypothesis 2 (H2) was verified. As with the existing related studies, the loss of development in NRACL due to CLR needs to be compensated by reasonable compensation [2,9,34,35].

- (3)

- The employment pressure of the township significantly increases the probability of residents choosing Scheme III. CLR is accompanied by the closure of inefficient enterprises, and under the “reduce to increase” land allocation rule, NRACL are at a disadvantage in the process of adding new construction land quotas, making it difficult to introduce high-quality enterprises, and employment pressure becomes a real problem [2,9,14]. As a result, the greater the employment pressure, the greater the preference of residents for off-site schemes to enhance development capacity. Employment pressure in the township also increases the probability of residents choosing Scheme II, but this effect does not pass the 10% level of the significance test. The possible reason for this is that while enhancing development capacity through the region also helps to expand employment, this route is slow and long-lasting, and thus residents’ preference for it is not significant. Employment pressure in the township significantly reduces the probability of residents choosing Scheme I, suggesting that employment pressure reinforces residents’ concerns about employment. Hypothesis 3 (H3) was verified.

- (4)

- The locational disadvantage of the township significantly increases the probability that residents will choose schemes II and III. The district can choose either a net increase or a net decrease in construction land quotas in the allocation of land quotas formed by the CLR, which depends on the district’s development orientation of the township [8]. This development orientation is influenced by the locational conditions of the township. The further the township is from the district administrative center, the less potential it has for allocating construction land quotas, and the economic development effect of using the land quotas formed by it for a township with a better location is better than the allocation of land quotas in a disadvantaged location. That is, the larger the allocation radius of the land quotas obtained by CLR, the better the benefits of the allocation. Moreover, the locality disadvantaged areas need technical support from developed areas to improve their competitiveness. Thus, the residents of areas with poor locations in the townships have a strong desire to develop, either locally or off-site, to enhance their development capacity.

- (5)

- The influence of village location conditions on residents’ choice of Scheme I, Scheme II and Scheme III is not significant. The possible reasons for this are as follows: since the land quotas formed by CLR are mainly allocated at the township level [8], villages lack bargaining power in terms of quota acquisition [2,9,14], and since townships in Shanghai are generally small and have convenient transportation conditions, the distance between villages is not a major factor of influence; thus, the effect of village location on residents’ choice behavior is not significant. Hypothesis 4 (H4) was verified.

- (6)

- The population density of townships significantly increases the probability that residents will choose Scheme I and Scheme II. Townships with high population densities also tend to be reserved or development areas, which are also better developed in their own right and have a cumulative effect of development over the years and have an agglomeration advantage. Residents in these areas have an incentive to improve their livelihoods and employment, and thus have a preference for Schemes I and II. In addition, since the higher the population density of the area, the greater the resistance to population migration in the CLR process, the residents have less opportunity to benefit from Scheme III compared to schemes I and II, and thus the residents are less dependent on Scheme III. Hypothesis 5 (H5) was verified.

- (7)

- The higher the development pressure, the more the township tends to develop itself and increase its income level [8,9,11], with less support for cross-regional development. The greater the development pressure, the more the industry has to upgrade, and CLR can increase the mobility of enterprises so that backward enterprises exit and new enterprises enter. As a result, residents have a greater preference for schemes I and II. Due to development pressures, residents have a weaker preference for off-site upgrading of development capacity, preferring either financial compensation or the upgrading of local development capacity for long-term development. Thus, there is a weaker preference for Scheme III. Hypothesis 6 (H6) was verified.

5.1.2. Micro-Influencing Factors

- (8)

- Men have a lower preference for Scheme III compared to women. This may be due to the comparative advantage of men in the job market, where men have a weaker preference than women for compensation for off-site enhancement of development capacity.

- (9)

- The older the resident, the more he/she prefers Scheme I. The older the resident, the more he/she prefers direct financial compensation that can directly improve his/her living conditions (this is consistent with existing studies) [36].

- (10)

- Residents with higher education levels show a higher preference for Scheme II and a lower preference for Scheme I. The more educated residents are more aware of CLR and more receptive to compensation schemes that enhance NRACL’s ability to develop in situ. Thus, they do not prefer short-term, one-time compensation schemes for economic losses. The effect of this on their preference for Scheme III is not significant.

- (11)

- Households with higher household incomes have higher expectations of economic development and thus have a higher preference for all three available schemes.

- (12)

- Residents with a higher proportion of dependent family members have a higher preference for Scheme III. A high proportion of family dependents indicates a high number of children attending school or elderly people and therefore a high demand for quality education or health care. The use of the construction land quota in a different location, along with the corresponding movement of employed persons and the general population and the consequent benefits of developed areas, including employment, health care and education, is attractive to families with high family support pressure. Hypothesis 7 (H7) was verified.

5.2. Heterogeneity Regression Results

5.2.1. Heterogeneity of Resident Status

5.2.2. Heterogeneity of the Types of Land Use Planning

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | See http://www.mnr.gov.cn/gk/ghjh/201811/t20181101_2324898.html, accessed on 1 November 2022, for more information. |

| 2 | See http://www.beijing.gov.cn/gongkai/guihua/wngh/cqgh/201907/t20190701_100008.html, accessed on 1 November 2022, for more information. |

| 3 | The “198 area” is the existing industrial land outside the planned industrial zone and the planned centralized construction area, covering an area of about 198 square kilo-meters, so named because of the number of areas. |

| 4 | See http://jinshan.gov.cn/ghzyj-ghjh/20220105/825960.html, accessed on 1 November 2022, for more information. |

References

- Bai, X.; Shi, P.; Liu, Y. Society: Realizing China’s Urban Dream. Nature 2014, 509, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Gu, X. Reduction of Industrial Land Beyond Urban Development Boundary in Shanghai: Differences in Policy Responses and Impact on Towns and Villages. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, T.; Feng, Z.; Wu, K. Identifying the Contradiction between the Cultivated Land Fragmentation and the Construction Land Expansion from the Perspective of Urban-rural Differences. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 71, 101826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Introduction to Land Use and Rural Sustainability in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Wang, W.; Guo, R. Policies for Optimizing Land-use Layouts in Highly Urbanized Areas: An Analysis Framework Based on Construction Land Clearance. Habitat Int. 2022, 130, 102697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, K.; Liu, H. Construction Land Reduction, Rural Financial Development, and Industrial Structure Optimization. Growth Change 2021, 52, 1783–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, G.; Liu, H. Porter Effect Test for Construction Land Reduction. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, G.; Liu, H. Location Choice of Industrial Land Reduction in Metropolitan Area: Evidence from Shanghai in China. Growth Change 2020, 51, 1837–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Mu, B.; Ahmad, N. Fostering Land Use Sustainability Through Construction Land Reduction in China: An Analysis of Key Success Factors Using Fuzzy-AHP and DEMATEL. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2022, 29, 18757–18779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Wu, G. The Network Governance of Urban Renewal: A Comparative Analysis of Two Cities in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X. Governance of Stock Construction Land in the Background of Land Consolidation in the Developed Regions: A New Analytical Framework of Spatial Governance. City Plann. Rev. 2020, 44, 52–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Lu, J.; Ye, Z.; Xia, J.; Xu, Y. The Impact and Countermeasure of Industrial Land Reduction on the Interests of Towns and Villages in the ‘198′ Area of Shanghai. Shanghai Land Resour. 2015, 36, 39–42+46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L.; Yao, Z.; Guo, X.; Yin, W. Land Redevelopment Based on Property Rights Configuration—Local Practice and Implications in the Context of New Urbanization. City Plann. Rev. 2015, 1, 22–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.; Zhou, X.; Liu, B.; Zhang, S.; Liu, R. Using “Situation-Structure-Implementation-Outcome” Framework to Analyze the Reduction Governance of the Inefficient Industrial Land in Shanghai. J. Nat. Resour. 2022, 37, 1413–1424. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Gu, X.; Liu, J.; Lu, Z.; Qiu, S. Research on the Impacts of Inefficiently Used Construction Land Reduction on Rural Transformation Development—A Grounded Analysis based on Shanghai City. China Land Sci. 2021, 35, 65–73. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qi, W.; Li, Z.; Yin, C. Response Mechanism of Farmers’ Livelihood Capital to the Compensation for Rural Homestead Withdrawal—Empirical Evidence from Xuzhou City, China. Land 2022, 11, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Four Theses in the Study of China’s Urbanization. Int. J. Urban Reg. 2006, 30, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Lu, J.; Li, Y. Does PPP Mode Improve the Quality of New-Type Urbannization in China? Stat. Res. 2020, 37, 101–113. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sadorsky, P. The Effect of Urbanization and Industrialization on Energy Use in Emerging Economies: Implications for Sustainable Development. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2014, 73, 392–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, R. Does Population Aging Reduce Environmental Pressures from Urbanization in 156 Countries? Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 848, 157330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, W.A. Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labor. Manch. Sch. 1954, 22, 139–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, G.; Liu, H. Industrial Land Reduction, High-quality Economic Development and Local Fiscal Revenue. Public Financ. Res. 2019, 9, 33–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Li, G.; Wang, K. Homestead Reduction, Economic Agglomeration and Rural Economic Development: Evidence from Shanghai, China. China Agr. Econ. Rev. 2022, 14, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Sun, Y.; Wang, K.; Liu, W.; Long, T. Research on Land Quota Market Mechanism in the Conteeext of Construction Land Reduction—Taking Shanghai City as an Example. China Land Sci. 2017, 31, 3–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Ma, K.; Liu, H. Study on the Operating Mechanism of Construction Land Reduction in Shanghai City. China Land Sci. 2016, 30, 3–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dai, B.; Gu, X.; Xie, B. Policy Framework and Mechanism of Life Cycle Management of Industrial Land (LCMIL) in China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inceyol, Y.; Cay, T. Comparison of Traditional Method and Genetic Algorithm Optimization in the Land Reallocation Stage of Land Consolidation. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 105989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Long, H.; Cui, W. Community-based Rural Residential Land Consolidation and Allocation can Help to Revitalize Hollowed Villages in Traditional Agricultural Areas of China: Evidence from Dancheng County, Henan Province. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H. Land Consolidation: An Indispensable Way of Spatial Restructuring in Rural China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyan, M.; Cay, T.; Akcakaya, O. A Spatial Decision Support System Design for Land Reallocation: A Case Study in Turkey. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2013, 98, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhu, Y.; He, L.; Song, H.; Mu, B.; Lyu, F. Recognizing and Managing Construction Land Reduction Barriers for Sustainable Land Use in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 14074–14105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Chen, Z. Urbanization, Green Development and Residents’ Happiness: The Moderating Role of Environmental Regulation. Environ. Impact Asses. 2022, 97, 106900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, J.; Porteous, T.; Skåtun, D. What Can Discrete Choice Experiments Do for You? Med. Educ. 2018, 52, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Tian, L. Land Decremental Planning and Implementation from the Perspective of Property Right Reconfiguration: A Case Study on Xinbang Town, Shanghai. City Plann. Rev. 2016, 40, 22–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, Y. Rural Households’ Willingness to Accept Compensation for Energy Utilization of Crop Straw in China. Energy 2018, 165, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Feng, L.; Hu, L.; Cao, Y. Older Residents’ Sense of Home and Homemaking in Rural-urban Resettlement: A Case Study of “moving-merging” communities in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2022, 126, 102616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Mehar, M. Socio-economic Factors Affecting Adoption of Modern Information and Communication Technology by Farmers in India: Analysis Using Multivariate Probit Model. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2016, 22, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis; Prentice Hall International, New York University: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cappellari, L.; Jenkins, S.P. Multivariate Probit Regression Using Simulated Maximum Likelihood. Stata J. 2003, 3, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xu, L.; Zhu, D.; Wang, X. Factors Affecting Consumer Willingness to Pay for Certified Traceable Food in Jiangsu Province of China. Can. J. Agr. Econ. 2012, 60, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Leaving the Countryside: Rural-to-Urban Migration Decisions in China. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shen, Q.; Tang, B.; Lu, C.; Peng, Y.; Tang, L. A Framework of Decision-making Factors and Supporting Information for Facilitating Sustainable Site Planning in Urban Renewal Projects. Cities 2014, 40, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, V.; Grosso, R. Designing Successful Urban Regeneration Strategies through a Behavioral Decision Aiding approach. Cities 2019, 95, 102386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scheme Type | Content | Interest Claims | Specific Measures | Benefit Characteristics | Beneficiary Flows |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme I | Direct compensation for NRACL’s direct subject losses | Full compensation |

|

|

|

| Scheme II | Increasing the scale of development of non-agricultural industries in NRACL, improving the capacity and competitiveness of industries |

|

|

| |

| Scheme III | Co-development type of off-site development with the transfer of quotas, in which income is increased and employment is expanded in the process of off-site development | Off-site use of construction land quotas with corresponding movement of employment and general population and consequent enjoy the benefits of NIACL |

|

|

| Influencing Factor | Specific Influencing Factor | Hypothesis | Scheme I | Scheme II | Scheme III |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macro factors | Development orientation of municipality to district | H1 | − | − | − |

| Reasonableness of compensation standard | H2 | + | + | + | |

| Employment pressure on township | H3 | − | + | + | |

| Location conditions | H4 | − | + | + | |

| Population density of township | H5 | + | + | + | |

| Development pressure on township | H6 | + | + | + | |

| Micro factors | Gender | H7 | − | − | − |

| Age | + | +/− | +/− | ||

| Level of education | − | + | − | ||

| Household income | + | + | + | ||

| Household size structure | +/− | +/− | + |

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Variable Code | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | Preferences of Scheme I | Options for increasing the price of the use of the quota or expanding the scope and intensity of compensation: “Yes” = 1, “No” = 0 | |

| Preferences of Scheme II | Options for appropriately increasing the use of construction land quotas in the area being reduced or improving the competitiveness of the region’s industries through financial and technical support: “Yes” = 1; “No” = 0 | ||

| Preferences of Scheme III | Options for enhancing the transfer of the remaining rural population to areas where construction land quotas are used: “Yes” = 1; “No” = 0 | ||

| Explanatory variables | Development orientation of municipality to district | (%) | The total area of new construction land required within the development boundary for each district from the planning base year to 2035/the total area of reduced construction land required outside the development boundary |

| Reasonableness of compensation standard | Evaluation of the reasonableness of the reduced compensation standard in this township compared to other townships: “Very reasonable” = 5; “Quite reasonable” = 4; “Average” = 3; “Quite unreasonable” = 2; “Very unreasonable” = 1 | ||

| Employment pressure on township | Rating of how negatively you and your family’s job opportunities have been affected by reduction planning and policies: “Very little” = 1; “Quite little” = 2; “Average” = 3. “Quite large” = 4; “very large” = 5 | ||

| Location condition of township | (kilometres) | Logarithm of the distance from the town to the district government station | |

| Location condition of village | (kilometres) | Logarithmic value of the distance from the village to the township government station | |

| Population density of township | (persons/square kilometers) | Logarithmic value of the resident population of the township per unit of administrative area | |

| Development pressure on township | (%) | Ratio of the total value of industrial output on the scale in the first year of the 14th Five-Year Plan to the first year of the 13th Five-Year Plan in each township | |

| Gender | “Male” = 1, “Female” = 0 | ||

| Age | “30 years and below” = 1; “31–45 years” = 2; “46–59 years” = 3; “60 and above” = 4 | ||

| Level of education | “Primary school and below” = 1; “Lower secondary school” = 2; “Upper secondary school” = 3; “College and above” = 4 | ||

| Household income | “50,000 CNY and below” = 1; “50,000 CNY–100,000 CNY” = 2; “100,000 CNY–200,000 CNY” = 3; “200,000 CNY and above” = 4 | ||

| Household size structure | (%) | Household dependency ratio | |

| Heterogeneous variables | Resident status | Village cadres, township cadres and above = 1; others = 0 | |

| Types of land use planning | Is it a U region ? | “Yes” = 1, “No” = 0 | |

| Is it a V region ? | “Yes” = 1, “No” = 0 |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2192 | 0.8335 | 0.3726 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| 2192 | 0.4676 | 0.4991 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| 2192 | 0.5192 | 0.4997 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| 2192 | 61.7834 | 17.0095 | 53.8462 | 99.7349 | |

| 2192 | 4.0087 | 0.8516 | 1.0000 | 5.0000 | |

| 2192 | 1.8125 | 0.8829 | 1.0000 | 5.0000 | |

| 2192 | 2.4523 | 1.1146 | −0.6280 | 3.6226 | |

| 2192 | 0.9412 | 0.9167 | −9.9443 | 2.5221 | |

| 2192 | 6.5469 | 0.3757 | 5.3628 | 7.5391 | |

| 2192 | 106.0134 | 34.1628 | 59.0644 | 183.0224 | |

| 2192 | 0.5584 | 0.4967 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| 2192 | 2.5032 | 0.9390 | 1.0000 | 4.0000 | |

| 2192 | 3.0780 | 1.0478 | 1.0000 | 4.0000 | |

| 2192 | 2.6428 | 1.0186 | 1.0000 | 4.0000 | |

| 2192 | 36.2963 | 33.9932 | 0.0000 | 100.0000 | |

| 2192 | 0.2778 | 0.4480 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| 2192 | 0.0899 | 0.2861 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| 2192 | 0.1683 | 0.3743 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| −0.0030 | −0.0013 | −0.0022 | |

| (0.0020) | (0.0018) | (0.0017) | |

| 0.2104 *** | 0.0248 | 0.0673 * | |

| (0.0424) | (0.0359) | (0.0360) | |

| −0.2047 *** | 0.0300 | 0.0641 * | |

| (0.0395) | (0.0349) | (0.0352) | |

| −0.1153 *** | 0.1448 *** | 0.1507 *** | |

| (0.0386) | (0.0329) | (0.0324) | |

| −0.0290 | 0.0022 | −0.0243 | |

| (0.0347) | (0.0297) | (0.0295) | |

| 0.1991 * | 0.3359 *** | 0.0803 | |

| (0.1158) | (0.0972) | (0.0943) | |

| 0.0020 * | 0.0021 ** | 0.0008 | |

| (0.0011) | (0.0009) | (0.0009) | |

| −0.0345 | −0.0559 | −0.1034 * | |

| (0.0662) | (0.0548) | (0.0547) | |

| 0.1485 *** | 0.0556 | 0.0127 | |

| (0.0452) | (0.0380) | (0.0383) | |

| −0.0926 ** | 0.1323 *** | −0.0422 | |

| (0.0452) | (0.0367) | (0.0368) | |

| 0.1046 ** | 0.1052 *** | 0.1330 *** | |

| (0.0413) | (0.0348) | (0.0347) | |

| 0.0003 | 0.0009 | 0.0016 * | |

| (0.0011) | (0.0009) | (0.0009) | |

| Constant | −0.8146 | −3.7602 *** | −1.4066 * |

| (0.9091) | (0.7757) | (0.7575) | |

| Draws | 50 | ||

| Atrho21 | −0.2228 *** | ||

| (0.0400) | |||

| Atrho31 | −0.2291 *** | ||

| (0.0407) | |||

| Atrho32 | 0.1742 *** | ||

| (0.0343) | |||

| Wald | 240.55 *** | ||

| Likelihood ratio test | 76.1670 *** | ||

| Observations | 2192 | ||

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1256 | −0.0275 | 0.0139 | |

| (0.0858) | (0.0701) | (0.0700) | |

| −0.0023 | −0.0015 | −0.0022 | |

| (0.0021) | (0.0018) | (0.0018) | |

| 0.2078 *** | 0.0253 | 0.0670 * | |

| (0.0425) | (0.0359) | (0.0360) | |

| −0.2004 *** | 0.0288 | 0.0646 * | |

| (0.0396) | (0.0350) | (0.0354) | |

| −0.1147 *** | 0.1446 *** | 0.1508 *** | |

| (0.0386) | (0.0329) | (0.0324) | |

| −0.0233 | 0.0010 | −0.0237 | |

| (0.0349) | (0.0298) | (0.0296) | |

| 0.2088 * | 0.3346 *** | 0.0809 | |

| (0.1155) | (0.0973) | (0.0943) | |

| 0.0021 ** | 0.0020** | 0.0008 | |

| (0.0011) | (0.0009) | (0.0009) | |

| −0.0402 | −0.0548 | −0.1041 * | |

| (0.0661) | (0.0548) | (0.0548) | |

| 0.1448 *** | 0.0562 | 0.0125 | |

| (0.0453) | (0.0381) | (0.0383) | |

| −0.1115 ** | 0.1365 *** | −0.0443 | |

| (0.0470) | (0.0384) | (0.0384) | |

| 0.0958 ** | 0.1072 *** | 0.1321 *** | |

| (0.0417) | (0.0352) | (0.0350) | |

| 0.0003 | 0.0009 | 0.0016 * | |

| (0.0011) | (0.0009) | (0.0009) | |

| Constant | −0.8781 | −3.7509 *** | −1.4104 * |

| (0.9063) | (0.7760) | (0.7578) | |

| Draws | 50 | ||

| Atrho21 | −0.2225 *** | ||

| (0.0400) | |||

| Atrho31 | −0.2297 *** | ||

| (0.0407) | |||

| Atrho32 | 0.1742 *** | ||

| (0.0343) | |||

| Wald | 242.42 *** | ||

| Likelihood ratio test | 76.2250 *** | ||

| Observations | 2192 | ||

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| −0.3489 ** | 0.2311 * | 0.0432 | |

| (0.1549) | (0.1314) | (0.1310) | |

| −0.1212 | 0.2773 ** | 0.0320 | |

| (0.1315) | (0.1126) | (0.1113) | |

| −0.0011 | −0.0038 * | −0.0026 | |

| (0.0024) | (0.0020) | (0.0020) | |

| 0.2036 *** | 0.0338 | 0.0686 * | |

| (0.0426) | (0.0360) | (0.0362) | |

| −0.2015 *** | 0.0273 | 0.0637 * | |

| (0.0395) | (0.0348) | (0.0352) | |

| −0.1772 *** | 0.2176 *** | 0.1609 *** | |

| (0.0513) | (0.0443) | (0.0435) | |

| −0.0276 | −0.0039 | −0.0250 | |

| (0.0357) | (0.0299) | (0.0296) | |

| 0.1609 | 0.3458 *** | 0.0837 | |

| (0.1152) | (0.0983) | (0.0956) | |

| 0.0030 ** | 0.0017 * | 0.0006 | |

| (0.0012) | (0.0009) | (0.0010) | |

| −0.0326 | −0.0542 | −0.1033 * | |

| (0.0663) | (0.0548) | (0.0547) | |

| 0.1423 *** | 0.0622 | 0.0136 | |

| (0.0455) | (0.0382) | (0.0384) | |

| −0.0996 ** | 0.1404 *** | −0.0410 | |

| (0.0454) | (0.0370) | (0.0370) | |

| 0.1079 *** | 0.1030 *** | 0.1327 *** | |

| (0.0413) | (0.0349) | (0.0347) | |

| 0.0003 | 0.0010 | 0.0016 * | |

| (0.0011) | (0.0009) | (0.0009) | |

| Constant | −0.5304 | −3.9364 *** | −1.4394 * |

| (0.9096) | (0.7836) | (0.7639) | |

| Draws | 50 | ||

| Atrho21 | −0.2189 *** | ||

| (0.0399) | |||

| Atrho31 | −0.2284 *** | ||

| (0.0408) | |||

| Atrho32 | 0.1742 *** | ||

| (0.0343) | |||

| Wald | 253.41 *** | ||

| Likelihood ratio test | 74.8275 *** | ||

| Observations | 2192 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, J.; Wang, K.; Liu, H. Residents’ Selection Behavior of Compensation Schemes for Construction Land Reduction: Empirical Evidence from Questionnaires in Shanghai, China. Land 2023, 12, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010020

Lu J, Wang K, Liu H. Residents’ Selection Behavior of Compensation Schemes for Construction Land Reduction: Empirical Evidence from Questionnaires in Shanghai, China. Land. 2023; 12(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Jianglin, Keqiang Wang, and Hongmei Liu. 2023. "Residents’ Selection Behavior of Compensation Schemes for Construction Land Reduction: Empirical Evidence from Questionnaires in Shanghai, China" Land 12, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010020

APA StyleLu, J., Wang, K., & Liu, H. (2023). Residents’ Selection Behavior of Compensation Schemes for Construction Land Reduction: Empirical Evidence from Questionnaires in Shanghai, China. Land, 12(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010020