Abstract

The large-scale acquisition of land by investors intensified following the 2007/2008 triple crises of food, energy, and finance. In the years that followed, tens of millions of hectares of land were leased or sold for agricultural investment. This phenomenon has resulted in a growing body of scholarship that seeks to explain trends, institutional regimes, impacts, and the variety of actors involved, among other subtopics, such as impacts on food security and livelihoods. Focusing on the case study of Ghana, this paper presents a review that uses both quantitative and qualitative methods to critically assess the state of large-scale land acquisitions for agricultural development in Ghana. Our objective in this review is to provide an overview of what we know about such acquisitions in Ghana while pointing to gaps and directions for future research. Contrary to the perception of large-scale land acquisitions being undertaken by foreign investors, the review shows there is a significant role of Ghanaian investors. Additionally, we found the negative impact of these acquisitions, specifically biofuel projects, which featured predominantly in the literature captured in this study. In addition, the role of traditional authorities (chiefs) was a central focus of studies dedicated to land acquisitions in Ghana. Areas that are either understudied or missing from the literature include conflicts, climate change, biodiversity, corporate social responsibility, gendered social differentiation, ethnicity, and the role of diaspora. These gaps call for future research that examines the land question from a multidimensional and multidisciplinary perspective.

1. Introduction

Existing research points to the 2007/2008 global triple crises of food, energy, and finance as being primary drivers of the growing interest in arable land around the world [1,2]. The spike in food commodity prices between 2007 and 2008 in particular is noted as a reason why investors rushed to acquire agricultural land, leading to an estimated 56 million hectares of land being acquired globally by 2010 [3]. In the case of Africa, in 2020, it is estimated that 15.2 million hectares were leased or acquired [2]. Thanks to its central role in the global land rush, Africa remains a focal unit of analysis as well as a center for struggles and controversies over what is believed to be “land grabs” [4,5,6,7,8,9]. However, data limitations have presented challenges for macro-level studies. A commonly used database, the Land Matrix, provides a wealth of data on the land rush, but that is incomplete, and it is believed that the actual amount of land acquired, leased, or sold may be significantly more than what is suggested [10].

Given the focal nature of Africa in the global land rush and the resulting scholarly attention, the focus of this paper on Ghana is justified to capture the growing literature on this West African country, which has experienced a significant share of land deals and ramifications over the past decade and half [11,12,13,14,15,16]. While the phenomenon described is neither new nor peculiar to the abovementioned period, the spate of land transactions has dramatically increased since 2007, warranting additional attention. In the case of Ghana, an estimated total of over 1 million hectares had been acquired for agricultural purposes by 2010 [17], the Land Matrix [18] reporting that a decade later the amount of land acquired was 1,344,588 hectares. This appears to suggest a slowdown. However, during the past 10 years, many deals have been canceled or stopped, while other new investments have begun. While there are some analytical differences between large-scale land acquisitions (LSLAs) and land grabs—the former tends to depict a legal land transaction, whereas the latter implies an illegal or coerced dispossession or disenfranchisement [7,19]—we have used an alternative framing in this review, the “land rush”, to avoid those implications. However, in synthesizing the available literature, we also utilize the terminologies presented within the respective literature presented.

The objective of this paper is to provide an overview of the land rush in Ghana by pointing to key issue areas studied in the existing scholarship: the themes, controversies, and gaps that can be filled by future research. In doing so, we make use of existing scholarship as well as contextual data provided by the Land Matrix. In total, 84 papers sourced from Web of Science (WoS) and Google Scholar (GS) were reviewed for this work (details of selection criteria outlined in the methods section). The next section of the paper provides a contextual background, followed by a presentation of the methodology used and then a discussion of findings, which is broken down into a thematic synthesis of what is known and what is missing in the existing literature, in addition to briefly examining aggregate trends in knowledge production. The concluding section sums up the paper, reiterating key points and the broader implications of our findings.

2. Context/Background

According to the Land Matrix [18], the total size of land acquired in Ghana is approximately 1,344,588 hectares. Out of this total, the Land Matrix reported that 151,453 hectares (or 11.3%) of these acquisitions were declared as failed. Despite this, the lack of complete data on land transactions in Africa (see [10,20,21]) suggests that this figure of 1 million quoted for Ghana could be grossly understated. It is, therefore, safe to say that presently, well over 1 million hectares of land have been acquired in Ghana by various actors in the land-acquisition space. The acquired lands are often leased to the investor for a period ranging from 25 to 99 years, with foreign nationals limited to a period of 50 years [22,23]. For this review, an interesting find is the emergence of “new” countries as the sources of investments into Ghana’s land sector. For instance, Cook et al. [24] highlighted the role of Chinese companies in the sector. Similarly, India was identified as a major source of investments in the country (see Table 1). This growing influence aligns with the increasing interest in South–South cooperation as an alternative to the historical reliance on Western partners and development organizations such as the World Bank and IMF (see [25]).

Table 1.

Purpose of land acquisition and investor origin.

These long-term leases have implications for the people in the affected communities, particularly in terms of the real prospect of long-term alienation from their means of livelihood because of these large-scale projects. However, data from Land Matrix (2020) reveals that the top three reasons underlying the acquisition of these lands are agriculture based, with an emphasis on food crop production. The threat that these projects pose to livelihoods comes in two forms. The first is the export-driven nature of the products and source country of the investors, which provides an insight into the export-oriented nature of the business. A review of the data on Land Matrix reveals that a significant percentage of investors are foreign nationals. It is, however, estimated that 4 out of 15 investments in the land sector had the involvement of Ghanaians [26]. Though there seems to be an increasing involvement of Ghanaians in land acquisitions, as demonstrated in the Table 1, it is our contention that their involvement could be a response to the existing policy regime, which encourages local participation. The Ghanaian involvement could therefore be limited to “intermediary” status, taking advantage of the favorable legal regime for domestic investors to aid their foreign counterparts. Significantly, though, the resulting projects have Ghana stated as the source country of the investors on the Land Matrix. Some authors [27,28] do attribute the global land rush for African lands to its being driven largely by investments from outside the continent. Second, the quest to find alternative energy sources that fueled jatropha cultivation for biofuels also had an impact on livelihoods. The Land Matrix data revealed that biofuels constituted some 15% of the purposes for which lands were acquired in Ghana (see Table 1). The emphasis on biofuel production deprived people in host communities of their lands and ability to produce, with a consequent loss of livelihoods.

The policy context of land acquisition is important because land acquisitions have occurred not only in response to external events but also in response to domestic policy and at different points in Ghana’s history. Since 1844, Ghana has put in place deliberate policies to attract investments into the agricultural sector by various actors. A presentation by Ahwoi [29] outlined certain phases in the investment drive into the sector. This includes the era of noninterventionist policy (1844–1956) during the era of colonialism when the colonial authority annexed lands in the name of the crown. The colonial authority, according to Larbi [30], adopted two main policy instruments for accessing land in the Gold Coast, namely expropriation (compulsory acquisition with compensation) in the colony and Ashanti and appropriation (compulsory acquisition without compensation) in the northern protectorate (now northern, upper-east, and upper-west regions). The era of Kwame Nkrumah saw a period of total state intervention (1957–1966) in the early days of independence, then the mixed era of private/government participation in agriculture (1967–1982).

The current phase in land acquisitions started with the implementation of the structural adjustment programs (SAPs) (1983 and beyond), which was dedicated to attracting the private sector to agricultural investments [29]. The SAPs and subsequent market liberalization policies transformed the agricultural sector by liberalizing the sector and increasing foreign and domestic investors. Deliberate policies and initiatives were implemented to this effect. The implementation of the SAPs set the tone for other initiatives deliberately aimed at attracting investments into the agricultural sector. According to Takane [31], for instance, measures such as the promulgation of the Land Title Registration Law in 1986 were put in place specifically to protect the property rights of investors. In addition, the establishment of investment promotion agencies (i.e., the Ghana Investment Promotion Centre in 1994) implemented government policy to attract investment, particularly foreign investment, into the country. Their role, among others, was to facilitate land access for prospective investors and sometimes play a role in directly allocating land to investors. This new land-tenure regime created an enabling environment and removed the risks associated with establishing large-scale farms. Thus, the development of large-scale farms in the country in the 1980s was a direct result of this deliberate state policy, which invariably facilitated the expansion of investment into the agricultural sector in Ghana [29]. In addition to domestic policy, the last phase of expanded private sector investment has been facilitated by broader trends of economic liberalization that have resulted in a global boom in land-related investments [32]. In the recent context of Africa, such a boom was also further bolstered in the years following the 2007/2008 hikes in global commodity prices, which resulted in a global rush for arable land [2]. The prevailing policy context created the enabling environment for a vast number of land deals, which have taken place from the Gold Coast era to present-day Ghana. It was noted from the review that though LSLAs are not a new phenomenon, the acquisitions in the colonial era were driven largely by the quest for power and its sustenance. However, the recent land rush was driven by domestic policy to attract investments into the land sector, increasing food prices, and the quest for alternative energy sources.

3. Methods

The data for this study were compiled using literature obtained from the Web of Science and Google Scholar. Using both literature search platforms, the keywords “land grab” and “large-scale land acquisition” (hereafter LSLA) were paired with “Ghana” to identify relevant literature up until the year 2020. The Web of Science offers a platform of peer-reviewed academic literature, which is commonly used for reviews of this nature (e.g., [10,33]). The limited collection of works through WoS meant that we complemented it with a repertoire of works from Google Scholar, chosen among the first 100 searched articles using the outlined keywords. We also used Google Scholar because the Web of Science does not index all the literature important to this study, such as journals based in Africa, reports from NGOs and governments, and theses and dissertations. After conducting the searches, the results were qualitatively assessed to remove false positives; a publication was deemed a false positive when its primary focus was not large-scale land acquisition in Ghana. The search from the Web of Science database resulted in 65 publications (28 for LSLA, 37 for land grab; 11 appearing in both searches). A qualitative review of the abstracts revealed nine false positives (two for LSLA, seven for land grab; 14% of results). With regard to the 11 publications that featured in both searches, one was found to be a false positive. Therefore, the Web of Science search produced 46 true positives that were used in this review.

As noted, a parallel search was conducted using Google Scholar with the same keywords. This search revealed higher results (15,000 for “land grab”, paired with “Ghana”; 97,200 results for “large-scale land acquisition”, paired with “Ghana”). Google Scholar orders the results by relevance, and the first 100 publications in each category of the search were reviewed. Though this cut-off point was arbitrary, the decision to select only the first 100 results was informed by the fact that it was most likely to contain the publications that were most relevant to this study. A qualitative process of removing false positives was undertaken, as was done with the Web of Science results. Subsequently, the list of true positives was compared with the list from the Web of Science to remove duplicates that appeared in both searches. After the removal of false positives and duplicates, the Google Scholar search resulted in 48 unique true positives. Regarding the type of publications identified via Google Scholar, the results included 28 academic articles, 3 reports, 8 research/working papers, 1 PhD dissertation, 4 master’s theses, 1 book, 2 book chapters, and 1 news editorial. Notably, all these were not included on Web of Science, showing the importance of diversifying platform types when conducting reviews, particularly for geographies and subjects that are underrepresented in what gets indexed on the Web of Science.

The total number of true positives from both searches used in this review was 94 unique publications (Web of Science 46, Google Scholar 48). Out of this total, 88 articles, representing 93.6%, were reviewed; six of the articles (two from Web of Science and four from Google Scholar) were not accessible. The final set of 88 articles was categorized thematically, and an initial categorization was completed by a qualitative reading of titles, abstracts, and keywords. The themes were drafted by the authors’ expertise of the subject matter and country and then were iteratively expanded, as the qualitative review was undertaken. Once categorized, each article was reviewed in detail, to identify the objectives of the respective studies, the findings, and the methods adopted. A thematic synthesis was then carried out for each of the identified articles under the various themes. This was accomplished by critically evaluating the publications, extracting data, and synthesizing available evidence. To strengthen the analysis, we used NVivo to analyze this set of 88 papers, which allowed for additional qualitative and quantitative assessments of specific themes and key terms, including being able to quantitatively triangulate qualitative findings (livelihoods 92%, chiefs 61%, land tenure 58%, biofuels 51%, gender 22%, conflicts 19%, climate change 14%). To conduct this analysis with NVivo, we created an NVivo data set and then used keyword searches of the full text of all included papers to quantify the number of references of each keyword within the papers. The results identified the dominant themes within the data set (see Table 2 below), which guided the thematic analysis in the findings section.

Table 2.

Records identified from the literature search.

A study of this nature has some limitations. Generally, we relied primarily on works published in English; hence, relevant scholarly literature in other languages was not included in this study. Additionally, the reliance on specific keywords in the literature search might have excluded relevant articles that used other terms and concepts (e.g., articles written about biofuels that are related to the topic but do not use the terminology searched for). A further limitation is associated with the databases used. For instance, the Google Scholar ranking of relevant publications is not clearly determined; hence, the results that show up on top of the lists might not always be the best sources or the appropriate ones, which leaves room for subjectivity and bias in the selection of articles for the review. A further limitation lies in the process of identifying and categorizing themes. This process is driven by the subjective perspective of the researchers, albeit informed by their expert knowledge on the topic. However, as a mitigating factor, these perspectives from the authors were borne out of additional readings, which brought up information to augment those that emerged from the literature search. Further, data from the Land Matrix was sourced to complement and validate the information contained in the literature retrieved from the two databases. This usage of Land Matrix is consistent with the existing scholarship in that our NVivo analysis showed that at least 10 out of the 88 papers reviewed (representing 11%) substantially engaged with this database to augment their research findings.

4. Evidence from Existing Scholarship: What We Know from the Literature

The evidence from the systematic review presents interesting insights into the broader landscape of LSLAs in Ghana. In this section, data gathered from the review of articles on the subject matter are categorized according to the dominant themes identified in the review (see Table 3). On the basis of the results of the NVivo analysis, the themes identified and discussed in this session include land grabs and biofuels, the impact on livelihoods, the land-tenure system, the role of chiefs, and the phenomenon of conflicts associated with these projects. These were selected on the basis of the results of the NVivo analysis, which revealed that they were dominant themes in the literature on land acquisitions in Ghana. The analysis also revealed that the subject matter of the gendered and environmental impact of land grabs featured in some studies, though they were in the minority.

Table 3.

The dominant themes from Nvivo analysis.

The results of the analysis as captured above formed the basis of the themes discussed below. It provides an overview of the intersecting nature of several issues and themes that underscore the phenomenon of the land rush in Ghana.

- a.

- Literature on biofuels

A review of the literature revealed that discussions on the subject matter of biofuels was dominant. From the NVivo analysis undertaken, 51% of the papers devoted attention to biofuels. Generally, there was emphasis on the actors and the impact of biofuel projects on host communities. For instance, Boamah [34], writing on the role of the chiefs, argued that they were motivated by the desire to formalize the use of stool land to create rural development opportunities and to formalize boundaries of stool land to avert potential future land litigations. However, Ahmed et al. [19] argued that chiefs often exploited the institutional weaknesses and inertia within land administration to act beyond being land custodians to become land sellers. The authors contended that the chiefs were motivated by the expected personal gains of the proposed biofuel projects. The quest for personal gains in the land-acquisition process more often positioned chiefs to become the cause of conflicts in certain host communities [35].

Significant attention was paid to the negative impacts of biofuel projects in host communities (see [35,36,37,38]). The impacts revealed in the literature included the negative impact of biofuel projects on food production and food security (as a result of converting lands for food production to jatropha farms for biofuel), farmer livelihoods, tenure insecurity among food crop farmers, and how the nature of the project implementation became a source of conflicts and insecurity between host communities and investors. The failure of biofuel projects in Ghana, Ahmed et al. [38] contend, was therefore attributable to poor business planning, institutional barriers, limited community participation, unfair compensation practices, obstacles posed by civil society, and the unconstructive involvement of chiefs.

- b.

- Land rush and livelihoods

The impact of these land deals on rural livelihoods featured heavily in the reviewed literature. However, the conclusions arrived at portrayed the outcomes of these as largely negative. There were some positive outcomes highlighted. For instance, Gordon and Botchway [39] noted that foreign engagement in mining transformed the sector and introduced mechanization and technology transfer to local artisanal miners in Ghana. Additionally, Twene [40] identified the provision of social amenities as a positive outcome of land grabs for commercial projects. These “positives” fit into the narrative by development partners such that the investments into the land sector are win-win situations with positive outcomes for both the investor and the local populations where such transactions occur [41,42].

Despite the positives, the bulk of studies offered a contrary outlook on the impact of LSLAs on rural livelihoods (see [5,15,22,43,44,45,46,47]). For instance, Schoneveld et al. [22] found that these acquisitions led to a loss of communal access to vital forest resources, which consequently threatened the sources of income for community members. Similarly, Madueke [44], among others, found there is damage to the environment, population displacement, and a breakdown in social cohesion. Further, it was found that communities with projects resulting from land grabs had a lower livelihood security in terms of food security, health, economy, and sanitation than the communities where there were no acquisitions [43]. Additionally, Andrews [15] noted that the influx of large-scale mining firms into the industry threatened the livelihoods of local miners who lost their concessions to these companies. These livelihood threats led Alhassan et al. [5,45] to conclude that despite the promise of positive outcomes, the uneven distribution of the benefits leaves rural communities and their livelihoods at a disadvantage where land grabs have taken place.

- c.

- The land-tenure system

The legal regime governing land administration in Ghana also featured prominently in the literature on Ghana. The trajectory of Ghana’s legislative framework on lands was outlined in the work of Kuusaana and Gerber [48]. The authors traced Ghana’s legislative framework from the Lands Bill in 1894 to the 1999 Ghana Land Policy. The unique attribute that the authors identified was how, with time, governments have adopted a noninterference posture toward lands in the control of customary institutions. Writing on the subject matter, Lambrectht and Asare [49] characterized Ghana’s land-tenure system as pluralistic. This is because both customary and statutory systems are recognized and overlap in responsibilities over land administration in Ghana. The differences between the customary and statutory systems, Aha and Ayitey [37] noted, are captured in their characteristics and forms of management.

While customary lands are under the control of traditional authorities represented by stools, skins, and family/clan/community heads and are generally governed by the customary practices prevailing in communities, the laws governing state lands, on the other hand, are codified into statutes and regulations based on laws. The relationship between these two systems, Tsikata and Yaro [50] revealed, is the fact that the Ghanaian state regulates and legitimizes customary land transactions to ensure some form of uniformity in land administration. The relationship between the state and the customary structures is quite clearly highlighted in the type of being administered at any point in time. Kirst [51] outlined the three types of land ownership in Ghana: state lands, vested lands, and customary lands. However, 80%–90% of the lands are held under customary land tenureships [52,53]. The state, according to Nolte and Vath [20], administers state lands in addition to vested lands as a function of law, while the management of customary lands is in the hands of the chief, who receives rents for the usage of lands. The creation of the Office of the Administrator of Stool Lands through Act 481 further strengthened the hold of customary systems over lands in Ghana [54]. The potential of conflicts within this pluralistic arrangement also received some attention in the reviewed literature. Andrews [15], for instance, cited a case that involved conflicts over the exercise of jurisdiction; a gold mining company, Newmont Ghana Limited, reportedly refused payment of compensation to the owners of unused lands in their mining project area. These lapses, Williams et al. [55] contend, call for new institutional arrangements and measures to enable governments strike the right balance between providing the security of leasehold sought by large-scale agricultural investors and protecting the equally legitimate land rights of small-scale farmers.

Therefore, to forestall future occurrences, Ghana passed the Land Act 2020 to revise and consolidate the laws on land, with the view to harmonizing those laws to ensure sustainable land administration and management and effective land-tenure systems. An interesting component of Land Act 2020 is the restrictions placed on the acquisition of land by noncitizens, as captured in Article 10 (1). Among others, a person cannot create an interest in, or right over, land in Ghana that vests in another person who is not a citizen of Ghana. Therefore, a company or corporate body is not a citizen if more than 40% of the equity shareholding or ownership is held by noncitizens. Act 2020 therefore seeks to secure domestic actor participation in the acquisition of lands in Ghana while curtailing the influence of foreign nationals in investments into the agricultural sector. The Act further highlights the government’s intention to determine the nature and scope of land grabs in Ghana through deliberate action. As with the case of other African countries, such as Ethiopia (see [10]), it can be said that this shift in policy direction was a response to the failures of previous policies that were more focused on the privatization and commoditization of land [29]. Previous policies promoted Ghana as the place for foreign direct investment with a promised “win-win” outcome, which did not materialize. In line with policy efforts across the continent, such as the Africa Mining Vision [56,57] and local content policies in the mining and energy sectors [58,59] that aim to make natural resources beneficial to respective host populations, Land Act 2020 seeks to further entrench the government’s intention to determine the nature, scope, and eventual impact of land deals in Ghana through deliberate action. In fact, such deliberate policy actions signal what Andrews and Nwapi [60] consider to be a critical juncture for potentially bringing the state back in again.

- d.

- The role of chiefs

A significant number of scholarly works on land grabs in Ghana was dedicated to the role of customary institutions (traditional authorities) in the processes leading to land grabs in Ghana (see [34,35,50,51,61,62,63,64]). Their role was quite widely recognized in the literature, where the keyword “chiefs” was substantially used in 51 papers (representing 61% of the sample). Along these lines, a significant number of scholarly works on the land rush in Ghana included detailed discussions on the role of customary institutions (traditional authorities) in the processes leading to the land rush in Ghana. The volume of work centered on the role of traditional institutions is influenced by the fact that agricultural land is under the control of land-owning families, with most decisions made by the family heads, their elders, and chiefs [38]. Thanks to their constitutionally guaranteed power and control over lands in Ghana, chiefs exercise an immense influence on the allocation processes in their communities. Their influence is seen mostly during negotiations on compensation payments, which often benefit the chiefs at the expense of rural land users [51]. Writing on the role of chiefs in land administration in Ghana, Ahmed et al. [19] argued that there are two basic roles: serving as custodians of the land and the interface between donors and investors. The authors contended that the performance of these roles, especially the latter, increased the chiefs’ growing involvement in lan1 d politics. The control that chiefs have had over land in their trustee role enhanced their status in the negotiation process and enabled them to engage directly with developers, investors, and donors [51]. The exercise of this power, Kasanga and Kotey [52] note, was carried out without the involvement of the community members. Decisions over land sales within the communities are most often carried out at the behest of the chiefs, to the disadvantage of the community members. This view was further reinforced by the work of Kirst [51], which also concluded that chiefs do not adhere to the principles enshrined in the law regarding the allocation of lands but rather operate within (sometimes even violating) the authority yielded to them in their communities.

From the reviewed literature, it was observed that the increased investments in the biofuel sector saw a corresponding rise in the power of chiefs to allocate lands. A study by Boamah [34] revealed that during the past decade, many Ghanaian chiefs have allocated numerous large land areas to agricultural investors mainly from Italy, Norway, Israel, and Canada for biofuels and other agricultural projects in Ghana. This increased role relegated state institutions to the role of confirming and registering the agreements reached between chiefs and investors. Although estimates of biofuel land deals are often contentious, they suggest that the authority of chiefs in land allocations has in recent times increased relative to that of the state. The involvement of state institutions in land allocations now merely takes the form of the confirmation and registration of the agreements reached between the chiefs and investors. The implication of this is that chiefs in Ghana have become facilitators of land grabs in Ghana. This position, therefore, empowers them to manipulate land-acquisition processes, benefiting them in ways that go beyond their mandates. This led Kuusaana [64] to conclude that chiefs in particular were major beneficiaries of these transactions, which sharply contrasts the experiences of groups such as migrant farmers, women, poor community “commoners”, and “title-less” smallholder farmers. The effect in many cases (as cited in [51]) could lead to the alienation of the people, communal resistance, and eventually conflicts. Antwi-Bosiako [62], however, contends that chiefs cannot be solely blamed for the challenges associated with land grabs. The author argues that the state’s noninterference policy in these negotiations, the insecure nature of land ownership, and the annexation of lands by brokers all create challenges for host communities.

- e.

- Less-covered (but important) areas of research

An analysis of the reviewed literature revealed themes that for the purposes of this study, we characterized as less-researched areas. The NVivo analysis revealed areas such as gender and climate change featured in the studies of land grabs in Ghana. The history of Ghana is replete with conflicts and contestations over shared commons such as land and water. According to Campion et al. [36], recent natural resource conflicts in Ghana are associated with land related to expropriation. Specifically, their study found, among others, that land grabs for biofuel production have been major sources of conflict in host communities in Ghana. These investments deprived local communities of the use of resources on which their livelihoods depend, without adequate compensation or provision of alternative livelihoods. Other authors (see [23,48]) reinforced the point that the commodification of lands, coupled with its increasing value in response to the land rush, only exacerbated the underlying problems associated with land management in the country. A study by Abubakari et al. [16] found that the implementation of CSR interventions and benefit-sharing mechanisms had de-escalating effects on land conflicts in host communities. Writing on the experiences in Agogo and Kpaacha, the authors highlighted the fact that the initiation of community projects, the establishment of formal rent payment system, the running of flexible and rotational job schemes for community members, and derestricted communal access to unused land spaces were some of the measures taken to soften local discontent and to mitigate the outbreak of conflicts.

On gender, the dominant theme focused on the impact of land grabs on women. The underlying basis for the studies on gender was that the livelihoods of individuals and social groups (in these communities) depended on how the individuals and social groups interacted with the evolving social and political institutions [13]. Therefore, one’s proximity to the center of power to a very large extent determines the extent to which one is affected by the processes of land grabs. According to Mariwah et al. [65], in the event of land grabs in a community, the fortunes of women could become a lot worse because of their marginalized status and peripheral roles in Ghanaian society. Similarly, Hausermann et al. [66] concluded in a study that land grabbing for gold resulted in deeper gendered inequalities because of the discrimination in compensation payments, a consequence of women’s not owning lands because of the patriarchal nature of the society and the land-tenure system. These inequalities in the land-tenure systems, Tsikata and Yaro [42] find, widen the inequality gap between men and women in host communities of projects resulting from land grabs. This view is further supported by Nibi [67], who argued that agrofuel expansion into areas where women have weak tenure security because of patriarchal structures and norms only tend to worsen their situation through what the author termed “double-dispossession”: a situation where women lose both their rights and access to land for cultivation and their rights to the natural resources for food, income, medicine, and fodder. On the environment and climate change, Nyantakyi-Frimpong [68] argued that land grabs produce a social barrier to climate change adaptation, as they lead to heightened uncertainty and apprehension among farmers, which affects decisions on climate-risk management.

4.1. Knowledge Production

For this review, we were also interested in how mechanisms of knowledge production and dissemination affect what becomes dominant as useful knowledge in the field. Along these lines, we sought to examine the author affiliations stated in the papers that emerged from our review. As shown in Table 4, the search from the two databases (Web of Science and Google Scholar) revealed that though Europe-based authors contributed to knowledge on land acquisitions in Ghana, a significant number of the authors had Ghana-based affiliations. This number represents 86 Ghanaian affiliations (approximately 35%) out of a total of 158 affiliations drawn from our sample of 88 papers. This is an interesting finding that highlights how Ghana-based academics are contributors to the topic of land grabs, with specific affiliations, such as the University of Ghana, University of Development Studies (Tamale), and Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. Although the research space is driven by European-based academics, the role of researchers based within the country of study in this data set is relatively more important than what has been found elsewhere (e.g., [10]).

Table 4.

Authors’ Affiliation.

The finding also somewhat contravenes past and ongoing discussions of how scholarship on Africa is often dominated by people who neither are African nor use perspectives that properly (or accurately) reflect the contexts being studied [69,70]. Although in the “ranked” journals that are indexed on the Web of Science, this continues to be the case, in the broader Google Scholar search, which includes other types of knowledge production, Ghana-based researchers are prominent. The percentage of Ghana-affiliated researchers in comparison with those from the rest of Africa, as shown in Table 4, does not fully capture the complete picture when examined superficially. To be sure, Ghana was a destination for major land deals, and this explains why many of the early researchers on this topic (who still remain quite prominent in the field) were Ghanaian. Another justification is that this study was specifically focused on content published on Ghana, which perhaps explains the marginal representation of other Africa-based scholars working on the same topic in different African countries.

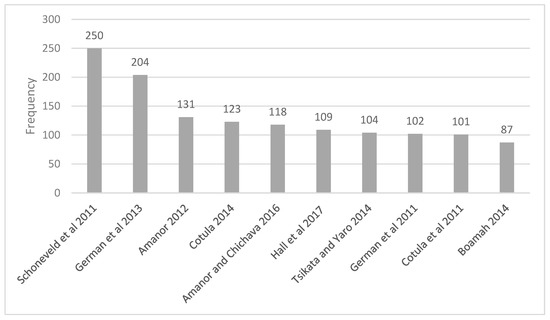

In addition to the total production of knowledge, we also wanted to assess the value attached to publications, as reflected in the citation counts of specific contributions. From Figure 1, there is significant diversity in the authorship of the top-10 most-cited articles (according to Google Scholar citation counts) from our sample of 88 publications. In the top-10 most-cited works, Amanor [71] ranked third and Tsikata and Yaro [12] ranked seventh in having Ghana-based affiliations. The paper by Amanor and Sergio [72], which ranked fifth, is an example of an Africa-based collaboration. It is important to note the cross-border research collaboration that has made such representational diversity in the existing scholarship possible, although there are some common European/Western names (e.g., Lorenzo Cotula, George Schoneveld, Laura German) in the subset of the top-10 most-cited articles. In addition, many times, national researchers are second, third, fourth, or fifth authors on publications, while Europe-based ones are first, underscoring how national experts are often used as data collectors without due regard for their overall intellectual contributions. This means that evidence of past and ongoing research collaboration does not necessarily undercut the historically determined asymmetrical power relations in social science scholarship and knowledge production in general [69,73,74,75]. However, it points to the gradual changes happening in democratizing and decolonizing knowledge production in Africa, as international research institutions such as the Indonesia-based Center for International Forestry Research (e.g., George Schoneveld’s affiliation) and the UK-based International Institute for Environment and Development (e.g., Lorenzo Cotula’s affiliation) are seeing the need to partner with experts beyond the usual groups of European or North American scholars.

Figure 1.

Top-10 Most-Cited Works, by Author.

While the emphasis here is on certain individual publications, the broader rationale behind the inclusion of this discussion is to explore the nature of aggregate knowledge production and offer some reflections on existing power asymmetries (e.g., who gets to lead certain research agendas and who does not) that may influence both the diversification of knowledge production and the inclusion of certain voices and perspectives in the knowledge that is widely disseminated. The deprovincialization of knowledge production is important because knowledge is power and because research on land tends to inform various national and global policy decisions. This is not to suggest that foreign researchers should not work on Ghana or other countries that they do not originate from or that these researchers misrepresent the realities in the country, although research has shown that the latter is possible (see [69,70]). Rather, our emphasis here is on representation and epistemic inclusion, especially since there are equally qualified researchers on both sides of the Atlantic pursuing similar research interests. In particular, we expect this brief reflection to contribute to discussions on the marginality and peripherality of Africans in both continental knowledge production and global knowledge production [76].

4.2. Identified Gaps and Directions for Future Research

This research identifies areas of research strength but also opportunities for future research on the land rush in Ghana. In this section, we note some of the missed opportunities for themes within the existing scholarship and direct scholars to them for future study. These include the themes of ethnicity and associated inequalities determined by social differentiation, corporate social responsibility, climate change, biodiversity, and diaspora.

It is fascinating that though social differentiation is a theme in a few of the papers (e.g., [5,14,15,45]), the majority of our sample makes limited reference to ethnicity and the differentiated inequalities associated with such ethnic backgrounds. To be sure, “ethnicity” as a keyword is substantially engaged in only four papers (5% of the sample). Three of these papers [13,61,77] focused on how ethnicity and social stratification intersect with the broader politics around land tenure (communal vs. statutory), while one focused specifically on the implications of ethnic boundary making (involving smallholders and Fulani pastoralists) on land rights, access, and disputes over the use of natural resources [23]. Given the customary nature of Ghana’s land-tenure system and the historical role of ethnicity in the development of the country [78,79,80], and even social norms around farming [81], one would expect to see more pages devoted to this theme in future research. It would be interesting for future research to examine whether ethnicity (and perhaps the history of conflict in certain regions) has a role to play in determining project locations or whether it is merely geography. The under-researched land rush in the northern region suggests there is more to consider than agroecology.

While the literature on corporate social responsibility (CSR) in Ghana is burgeoning, there is a significant gap in the knowledge of what role CSR plays in the context of land grabs, given that the current scholarship on this topic has focused mostly on the extractive and nonagriculture industries (see [82,83,84,85]). Given that domestic investors maintain a stake in land deals, as depicted in Table 1, this gap may be explained by the fact that CSR has often been projected as something that foreign investors are expected to undertake. However, an interesting finding in the reviewed literature points to the fact that some of these investors have used CSR initiatives as a mechanism to mitigate land disputes and conflicts. For instance, Abubakari et al. [16] found that the implementation of CSR interventions and benefit-sharing mechanisms has had de-escalating effects on land conflicts in two selected communities that have experienced the land rush (i.e., Agogo and Kpaacha). In Agogo, for instance, measures include the decision of the investor to change the investment focus from biofuel to food crops, the establishment of a formal rent payment system, and the running of flexible and rotational job schemes for community members [86]. Similar interventions in Kpaacha, including infrastructure development and de-restricted communal access to unused land spaces and economic trees for local livelihood sustainability, softened local discontent and served as a mitigation measure against the outbreak of conflicts [16]. The point is that there may be many such CSR interventions that help investors and agrarian communities address the multiple challenges posed by large-scale land deals. However, we do not know this, because only five of the 88 papers reviewed substantially engaged with the topic (see [13,15,16,87,88]), suggesting the need for further research on this issue. In particular, the understanding of CSR as a measure to de-escalate land-related conflicts (or not) is an interesting avenue for future research.

What is clear from the review is that gender has been featured in about 22% of the 88 papers sampled for this study (e.g., [12,66,67,89]). For instance, Hausermann et al. [66] concluded in a study that land grabbing for gold resulted in deeper gendered inequalities and social differentiation. This was because the compensation paid to men for the destruction of their farms far exceeds that paid to women if compensated, though women are rarely compensated. This disparity represents the exploitation of existing customary land-tenure systems, which are socially and structurally biased against women. A study by Tsikata and Yaro [12] also found that these inequalities in patriarchal land-tenure systems have contributed to women’s routinely having smaller and less-fertile land and experiencing challenges with productivity and livelihood outcomes. These findings are supported by Nibi [67], whose work examined how large-scale agrofuel development in Northern Ghana leads to women’s experiencing “double-dispossession”, involving a situation where women lose both their rights and access to land for cultivation and their rights to the natural resources for food, income, medicine, and fodder. The evidence, therefore, points to some interesting insights. However, with only 20 papers drawing on some gender analysis, we would expect future research to further engage with this topic, including the intersectionality of gender and other factors such as class/social status, age, ethnicity, and religion, among other social differentiations.

Given the nature of the land rush, which has often been based on the land’s agricultural potential (as shown in Table 1, on the intended uses of the investment), the limited research on environmental impacts is notable. There are a few papers that consider impacts on biodiversity (6 papers, 7%) and climate change (12 papers, 14%). We believe that there are significant opportunities to engage in interdisciplinary or nexus research approaches that entangle the issues of environment, livelihood, regulation, and investment, as they have often been disentangled into disciplinary studies. Similarly, there is very little research on the role of diaspora and domestic investors, despite our research’s finding them to have a significant role. In our sample, only two papers focused on the role of diaspora [17,74] and only one publication had some focus on domestic investments [89]. Much more attention is warranted, and this is more so the case following the 2020 regulatory changes that seek to prioritize Indigenous Ghanaian investments.

Finally, the topic of knowledge production and dissemination is worth re-examination as part of future work on this topic. Although we have discussed a growing diversity in the list of scholars writing about the land rush in Ghana, an important question to pose is, who is accessing or using such knowledge produced? For instance, the top-10 most-cited works (see Figure 1) are published in such journals as Ecology and Society, Feminist Economics, the Journal of Peasant Studies, World Development, Journal of Development Studies, and Food Security. Of these journals, only Ecology and Society is an open-access journal, which perhaps reflects the highest citation count (i.e., 250) for the Schoneveld et al. [22] paper published in that venue. Perhaps, the fact that this study did not yield results from many journals that are open access reflects how knowledge on this topic tends to serve more of an academic purpose than as a public policy contribution, per se. However, beyond this, the point is that the vast majority of the 88 papers are published in journals that are not easily accessible to scholars (or even policymakers) based in Ghana and elsewhere in Africa who may find a use for such publications. This creates a significant barrier to the so-called decentralization of knowledge production and dissemination, which we believe is something future research on this topic should pay serious attention to. As funding agencies are increasingly expecting research grant holders to consider open-access publishing options (with some designating funds for this), the situation is likely to improve over the next decade, but deliberate action is required.

5. Conclusions

The land rush has deep historical roots. In many places, Ghana included, this traces back to the colonial era, with some deals spanning a long history (although investors change over time, the dispossessions remain). Thanks to the historical importance of the land rush, this paper outlined the developments of land tenure and investment regulation over the long-term, finding that while there indeed has been a rush since the 2007/08 commodity price spike, this was not the first rush nor was it the first time that external actors have exerted pressure on Ghana’s land-tenure laws that have enabled foreign nationals to acquire land. The 2020 shift in regulations has the potential to narrow the opportunities for foreign investors. However, the impact of these changes will depend not only on implementation but also on their overall durability over time. For lands that are currently acquired in Ghana, investors with historical ties to Ghana (e.g., the UK and the US) remain important, but investors from new geographies have emerged, with those coming from India now holding the most amount of land of all foreign investments (according to available data). This represents an important juncture for growing South–South cooperation.

Less researched and less covered in the discourse of the land rush is the role of domestic and diaspora investors, which is an area for future research. Other understudied areas in the Ghanaian context of the land rush include aspects related to the environment (e.g., biodiversity and climate change), corporate social responsibility, and studies that look in more detail at intersectionality, such as the impacts of ethnicity, gender, and livelihood. Alongside these thematic gaps, the review has also presented questions of the politics of knowledge production, the peer-reviewed literature being led largely by Europe-based scholars, raising questions about voice and agency within the field. Additionally, most of the peer-reviewed literature is not open access, raising questions about accessibility. Addressing these gaps and issues will require research initiatives that build upon existing evidence and extend it into new domains, utilizing new modalities of dissemination. Such initiatives will have significant ramifications for the purpose and utility of future knowledge produced on this topic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization J.A., N.A. and L.C.; methodology J.A., N.A. and L.C; formal analysis J.A.; resources J.A. and L.C.; writing—original draft preparation J.A.; writing—review and editing J.A. and L.C.; supervision N.A. and L.C.; funding acquisition N.A. and L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada as part of its Insight Development Grant program (2019–2021), under the project titled The Global Land Rush, Inequalities, and Livelihoods: Enabling Environments for Strengthening Food Security in Ethiopia and Ghana.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McMichael, P. The land grab and corporate food regime restructuring. J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, L.; Andrews, N. International political economy and the land rush in Africa: Trends, scale, narratives, and contestations. In The Transnational Land Rush in Africa: A Decade After the Spike; Palgrave: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cotula, L. The international political economy of the global land rush: A critical appraisal of trends, scale, geography and drivers. J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 649–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayelazuno, J.A. Land governance for extractivism and capitalist farming in Africa: An overview. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, S.I.; Mohammed, T.S.; Kuwornu, J.K.M. Is land grabbing an opportunity or a menace to development in developing countries? Evidence from Ghana. Local Environ. 2018, 23, 1121–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, S. Struggles over land and authority in Africa. Afr. Stud. Rev. 2017, 60, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng-Odoom, F. Understanding land grabs in Africa: Insights from Marxist and Georgist political economics. Rev. Black Polit. Econ. 2015, 42, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, S. Land grabs today: Feeding the disassembling of national territory. Globalizations 2013, 10, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, J. Land grabs, government, peasant and civil society activism in the Senegal River Valley. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 2012, 399, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, L.; Legault, D. The rush for land and agricultural investment in Ethiopia: What we know and what we are missing. Land 2020, 9, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, C. Norwegian Land Grabbers in Ghana—The Case of ScanFuel. Available online: https://www.spireorg.no/uploads/1/2/7/6/127694377/land_grabbing_-_the_case_of_scanfuel_2010.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Tsikata, D.; Yaro, J.A. When a good business model is not enough: Land transactions and gendered livelihood prospects in rural Ghana. Fem. Econ. 2014, 20, 202–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boamah, F. Biofuels and Land Politics: Connecting the Disconnects in the Debate about Livelihood Impacts of Jatropha Biofuel Land Deals in Ghana. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H.; Kerr, R.B. Land grabbing, social differentiation, intensified migration and food security in northern Ghana. J. Peasant Stud. 2017, 44, 421–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N. Land versus livelihoods: Community perspectives on dispossession and marginalization in Ghana’s mining sector. Resour. Policy 2018, 58, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakari, M.; Owusu, T.K.; Amissah, A.G. From conflict to cooperation: The trajectories of large-scale land investments on land conflict reversal in Ghana. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotula, L.; Oya, C.; Codjoe, E.A.; Eid, A.; Kakraba-Ampeh, M.; Keeley, J.; Admasu, L.K. Testing claims about large land deals in Africa: Findings from a multi-country study. J. Dev. Stud. 2014, 50, 903–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land Matrix. Ghana. Available online: https://landmatrix.org/resources/country-profile-ghana/ (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Ahmed, A.; Kuusaana, E.D.; Gasparatos, A. The role of chiefs in large-scale land acquisitions for jatropha production in Ghana: Insights from agrarian political economy. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, K.; Väth, S.J. Interplay of land governance and large-scale agricultural investment: Evidence from Ghana and Kenya. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2015, 53, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagne, M.; Fent, A. The faltering land rush and the limits to extractive capitalism in Senegal. In The Transnational Land Rush in Africa: A Decade After the Spike; Cochrane, L., Andrews, N., Eds.; Palgrave: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 55–85. [Google Scholar]

- Schoneveld, G.C.; German, L.A.; Nutakor, E. Land-based investments for rural development? A grounded analysis of the local impacts of biofuel feedstock plantations in Ghana. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusaana, E.D.; Bukari, K.N. Land conflicts between smallholders and Fulani pastoralists in Ghana: Evidence from the Asante Akim North District (AAND). J. Rural Stud. 2015, 42, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.; Jixia, L.; Tugendhat, H.; Alemu, D. Chinese Migrants in Africa: Facts and Fictions from the Agri-Food Sector in Ethiopia and Ghana. World Dev. 2016, 81, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadir, F. Rising donors and the new narrative of ‘South–South’ cooperation: What prospects for changing the landscape of development assistance programmes? Third World Q. 2013, 34, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotula, L.; Vermeulen, S.; Mathieu, P.; Toulmin, C. Agricultural investment and international land deals: Evidence from a multi-country study in Africa. Food Secur. 2011, 3, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmody, P. The New Scramble for Africa; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, S.; Paris, Y.; Praveen, J. Imperialism and primitive accumulation: Notes on the new scramble for Africa. Agrar. South J. Polit. Econ. 2012, 1, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahwoi, K. Government’s Role in Attracting Viable Agricultural Investments Experiences from Ghana. In Proceedings of the World Bank Annual Bank Conference on Land Policy and Administration, Washington, DC, USA, 26–27 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Larbi, W.O.; Adarkwah, A.; Olomolaiye, P. Compulsory land acquisition in Ghana—Policy and praxis. Land Use Policy 2004, 21, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takane, T. Smallholder and nontraditional exports under economic liberalization: The case of pineapples in Ghana. Afr. Study Monogr. 2004, 25, 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zoomers, A. Globalisation and the foreignisation of space: Seven processes driving the current global land grab. J. Peasant Stud. 2010, 37, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, Ž.; Bianka, D.; Van Vliet, J.; Van Der Zanden, E.H.; Verburg, P.H. Local land-use decision-making in a global context. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 083006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boamah, F. Imageries of the contested concepts “land grabbing” and “land transactions”: Implications for biofuels investments in Ghana. Geoforum 2014, 54, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campion, B.B.; Acheampong, E. The chieftaincy institution in Ghana: Causers and arbitrators of conflicts in industrial Jatropha investments. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6332–6350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campion, B.B.; Essel, G.; Acheampong, E. Natural resources conflicts and the biofuel industry: Implications and proposals for Ghana. Ghana J. Geogr. 2012, 4, 42–64. [Google Scholar]

- Aha, B.; Ayitey, J.Z. Biofuels and the hazards of land grabbing: Tenure (in)security and indigenous farmers’ investment decisions in Ghana. Land Use Policy 2017, 60, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Campion, B.B.; Gasparatos, A. Biofuel development in Ghana: Policies of expansion and drivers of failure in the jatropha sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, G.; Botchwey, G. Conflict, collusion and corruption in small-scale gold mining: Chinese miners and the state in Ghana. Commonw. Comp. Polit. 2017, 55, 444–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twene, S.K. Land grabbing and rural livelihood sustainability: Experiences from the Bui dam construction in Ghana. Master’s Dissertation, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Smaller, C.; Mann, H. A Thirst for Distant Lands: Foreign Investment in Agricultural Land and Water; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2009; Available online: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/est/INTERNATIONAL-TRADE/FDIs/A_Thirst_for_distant_lands.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Cotula, L.; Vermeulen, S.; Leonard, R.; Keeley, J. Land Grab or Development Opportunity?: Agricultural Investment and International Land Deals in Africa; IIED: London, UK; FAO: London, UK; IFAD: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mabe, F.N.; Sulemena, N.; Eliasu, M.; Boateng, V.F. The Nexus between Land Acquisition and Household Livelihoods in the Northern Region of Ghana. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madueke, S.E. Africa faith and justice network and the damages of land grabbing: The case of the Brewaniase community, Ghana. J. Soc. Encount. 2019, 3, 58–74. Available online: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/social_encounters/vol3/iss1/9 (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Alhassan, S.I.; Mohammed, T.S.; Kuwornu, J.K.M.; Damba, O.T.; Amikuzuno, J. The Nexus of Land Grabbing and Livelihood of Farming Households in Ghana. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 23, 3289–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaro, J.A.; Tsikata, D. Savannah fires and local resistance to transnational land deals: The case of organic mango farming in Dipale, Northern Ghana. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2013, 32, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoneveld, G.C.; German, L.; Nutakor, E. Towards Sustainable Biofuel Development: Assessing the Local Impacts of Large-Scale Foreign Land Acquisitions in Ghana. 2010. Available online: https://www.cifor.org/knowledge/publication/3597/ (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Kuusaana, E.D.; Gerber, N. Institutional synergies in customary land markets—Selected case studies of large-scale land acquisitions (LSLAs) in Ghana. Land 2015, 4, 842–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, I.; Asare, S. The complexity of local tenure systems: A smallholders’ perspective on tenure in Ghana. Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikata, D.; Yaro, J. Land market liberalization and trans-national commercial land deals in Ghana since the 1990s. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Land Grabbing, Brighton, UK, 6–8 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kirst, S. Chiefs do not talk law, most of them talk power traditional authorities in conflicts over land grabbing in Ghana. Can. J. Afr. Stud. 2020, 54, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasanga, K.; Kotey, N. A Land Tenure and Resource Access in West Africa—Land Management in Ghana: Building on Tradition and Modernity; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2001; Available online: https://pubs.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/9002IIED.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Ghebru, H.; Lambrecht, I. Drivers of perceived land tenure (in)security: Empirical evidence from Ghana. Land Use Policy 2017, 66, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElHadary, Y.A.E.; Obeng-Odoom, F. Conventions, changes, and contradictions in land governance in Africa: The story of land grabbing in North Sudan and Ghana. Afr. Today 2012, 59, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.O.; Gyampoh, B.; Kizito, F.; Namara, R. Water implications of large-scale land acquisitions in Ghana. Water Altern. 2012, 5, 243–265. [Google Scholar]

- Dauda, S. “Operationalising the Africa mining vision”: Critical reflections from Ghana. Can. J. Dev. Stud./Rev. Can. D’études Dev. 2020, 41, 504–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G. The Africa Mining Vision: A manifesto for more inclusive extractive industry-led development? Can. J. Dev. Stud. 2020, 41, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovadia, J.S. Local content policies and petro-development in Sub-Saharan Africa: A comparative analysis. Resour. Policy 2016, 49, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwapi, C.; Andrews, N. A New developmental state in Africa: Evaluating recent state interventions vis-a-vis resource extraction in Kenya, Tanzania, and Rwanda. McGill J. Sust. Dev. Law 2017, 13, 223. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, N.; Nwapi, C. Bringing the state back in again? The emerging developmental state in Africa’s energy sector. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 41, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanor, K. Global Restructuring and Land Rights in Ghana: Forest Food Chains, Timber, and Rural Livelihoods; Research Report No. 108; Nordic Africa Institute: Uppsala, Sweden, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Antwi-Bediako, R. Chiefs and nexus of challenges in land deals: An insight into blame perspectives, exonerating chiefs during and after Jatropha investment in Ghana. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 1456795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablo, A.D.; Asamoah, V.K. Local participation, institutions and land acquisition for energy infrastructure: The case of the Atuabo gas project in Ghana. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 41, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusaana, E.D. Winners and losers in large-scale land transactions in Ghana—Opportunities for win-win outcomes. Afr. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2017, 9, 62–95. Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/aref/article/view/162144 (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Mariwah, S.; Evans, R.; Antwi, B.K. Gendered and generational tensions in increased land commercialisation: Rural livelihood diversification, changing land use, and food security in Ghana’s Brong-Ahafo Region. Geo Geogr. Environ. 2019, 6, e00073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausermann, H.; Ferring, D.; Atosona, B.; Mentz, G.; Amankwah, R.; Chang, A.; Hartfield, K. Land-Grabbing, land-use transformation and social differentiation: Deconstructing “small-scale” in Ghana’s recent gold rush. World Dev. 2018, 108, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibi, S.H.A. Feminist Political Ecology of Large-Scale Agrofuel Production in Northern Ghana: A Case Study of Kpachaa. Master’s Dissertation, International Institute of Social Studies, The Hague, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H. What lies beneath: Climate change, land expropriation, and zaï agroecological innovations by smallholder farmers in northern Ghana. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ake, C. Social Science as Imperialism: The Theory of Political Development, 2nd ed.; Ibadan University Press: Ibadan, Nigeria, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbalist, Z. So many ‘Africanists’, so few Africans: Reshaping our understanding of ‘African politics’ through greater nuance and amplification of African voice. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 2020, 47, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanor, K.S. Global resource grabs, agribusiness concentration and the smallholder: Two West African case studies. J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 731–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanor, K.S.; Sérgio, C. South–South cooperation, agribusiness, and African agricultural development: Brazil and China in Ghana and Mozambique. World Dev. 2016, 81, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arowosegbe, J.O. African scholars, African studies and knowledge production on Africa. Africa: The J. Int. Afr. Inst. 2016, 86, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloruntoba, S. Pan-Africanism, knowledge production and the third liberation of Africa. Int. J. Afr. Renaiss. Stud. -Multi- Inter-Transdiscipl. 2015, 10, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.; Eyene, O. Trends of epistemic oppression and academic dependency in Africa’s development: The need for a new intellectual path. J. Pan Afr. Stud. 2012, 5, 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S.J. Epistemic Freedom in Africa: Deprovincialization and Decolonization, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, C. Land tenure regimes and state structure in rural Africa: Implications for forms of resistance to large-scale land acquisitions by outsiders. J. Contemp. Afr. Stud. 2015, 33, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazan, N. Ethnicity and politics in Ghana. Polit. Sci. Q. 1982, 97, 461–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, C. Ethnicity and the Making of History in Northern Ghana; Edinburgh University Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, A. The situational importance of ethnicity and religion in Ghana. Ethnopolitics 2010, 9, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanko, M. Is farming a belief in Northern Ghana? Exploring the dual-system theory for commerce, culture, religion and technology. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuada, J.; Hinson, E.R. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices of foreign and local companies in Ghana. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 54, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah-Tawiah, K.; Dartey-Baah., K. Corporate social responsibility in Ghana: A sectoral analysis. In Corporate Social Responsibility in Sub-Saharan Africa; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 189–216. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, N. Gold Mining and the Discourses of Corporate Social Responsibility in Ghana; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Kojo, A.; Andrews, N. A developmental paradox? The “dark forces” against corporate social responsibility in Ghana’s extractive industry. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 1051–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukari, K.N.; Elias, D.K. Impacts of large-scale land holdings on fulani pastoralists’ in the agogo traditional area of ghana. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, L.; Schoneveld, G.; Mwangi, E. Contemporary processes of large-scale land acquisition in Sub-Saharan Africa: Legal deficiency or elite capture of the rule of law? World Dev. 2013, 48, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayelazuno, J.A. Water and land investment in the “overseas” of Northern Ghana: The land question, agrarian change, and development implications. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 915–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nketiah, P. Agricultural Land Deals, Farmland Access and Livelihood Choice Decisions in Northern Ghana. Ph.D. Thesis, University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).