The Environmental and Socio-Economic Effect of Farmland Management Right Transfer in China: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

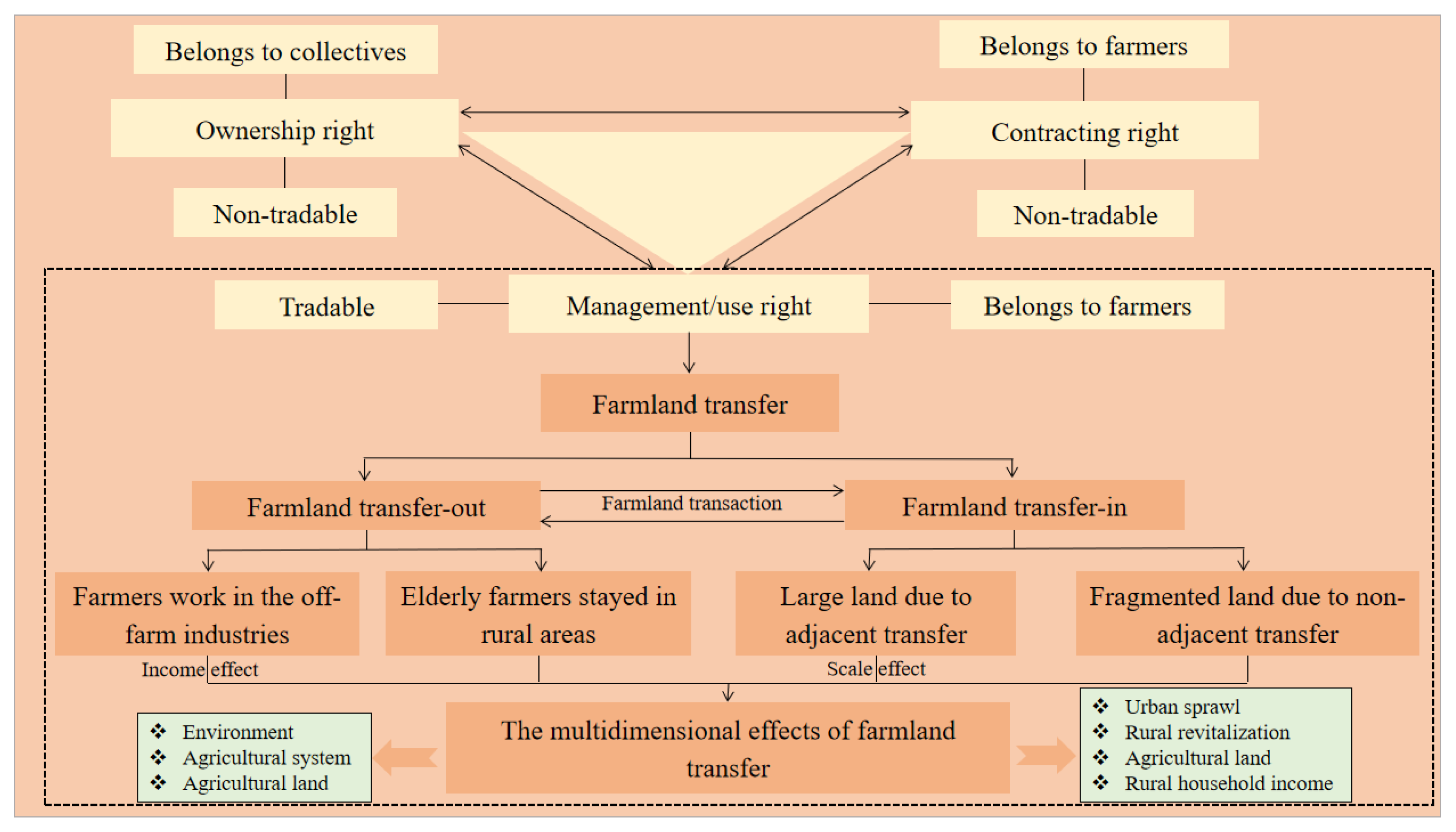

Conceptualizing Farmland Transfer in China

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Determining the Scope

2.2. Literature Search and the Inclusion Criteria

3. Results

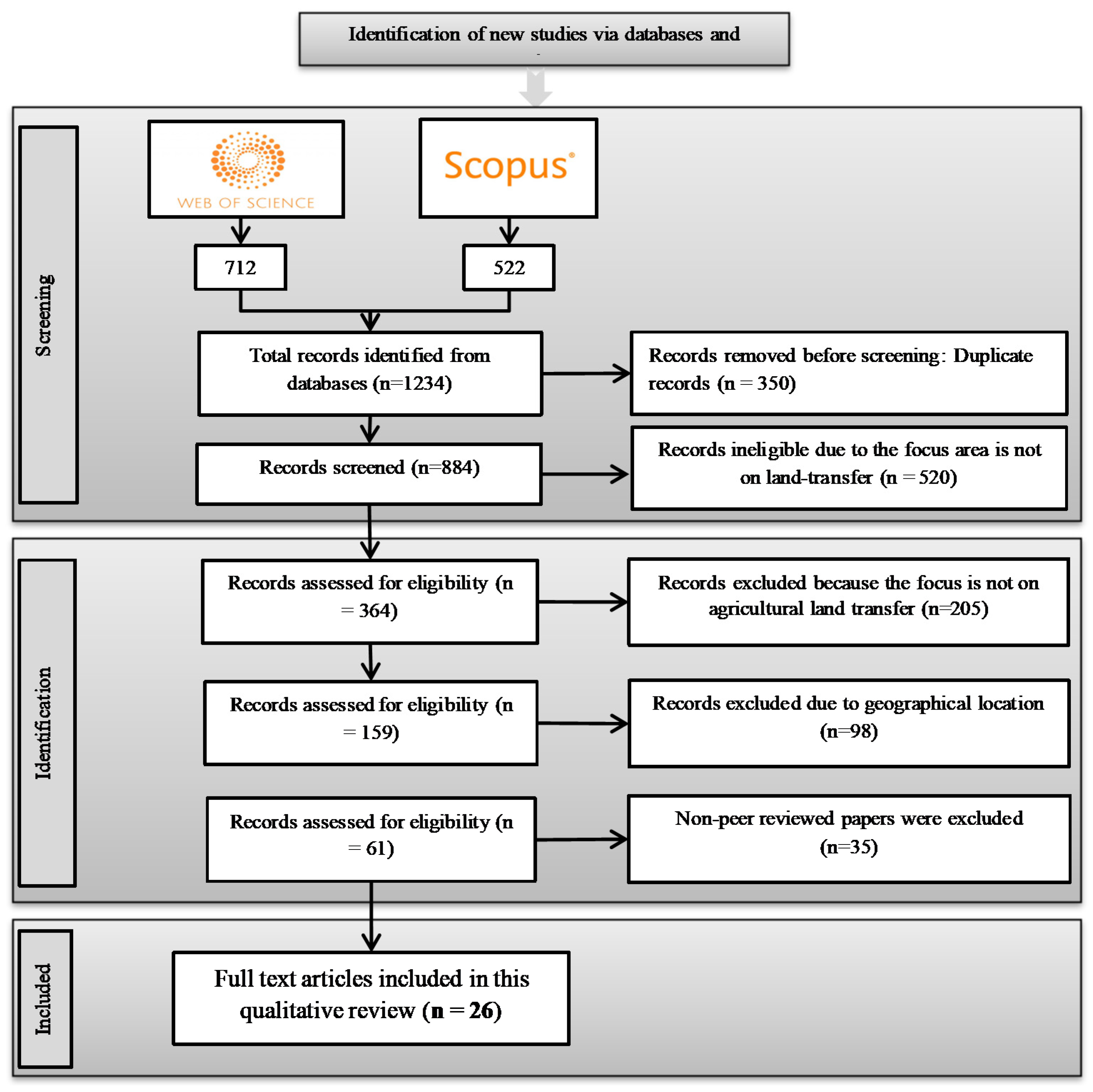

3.1. Search Results

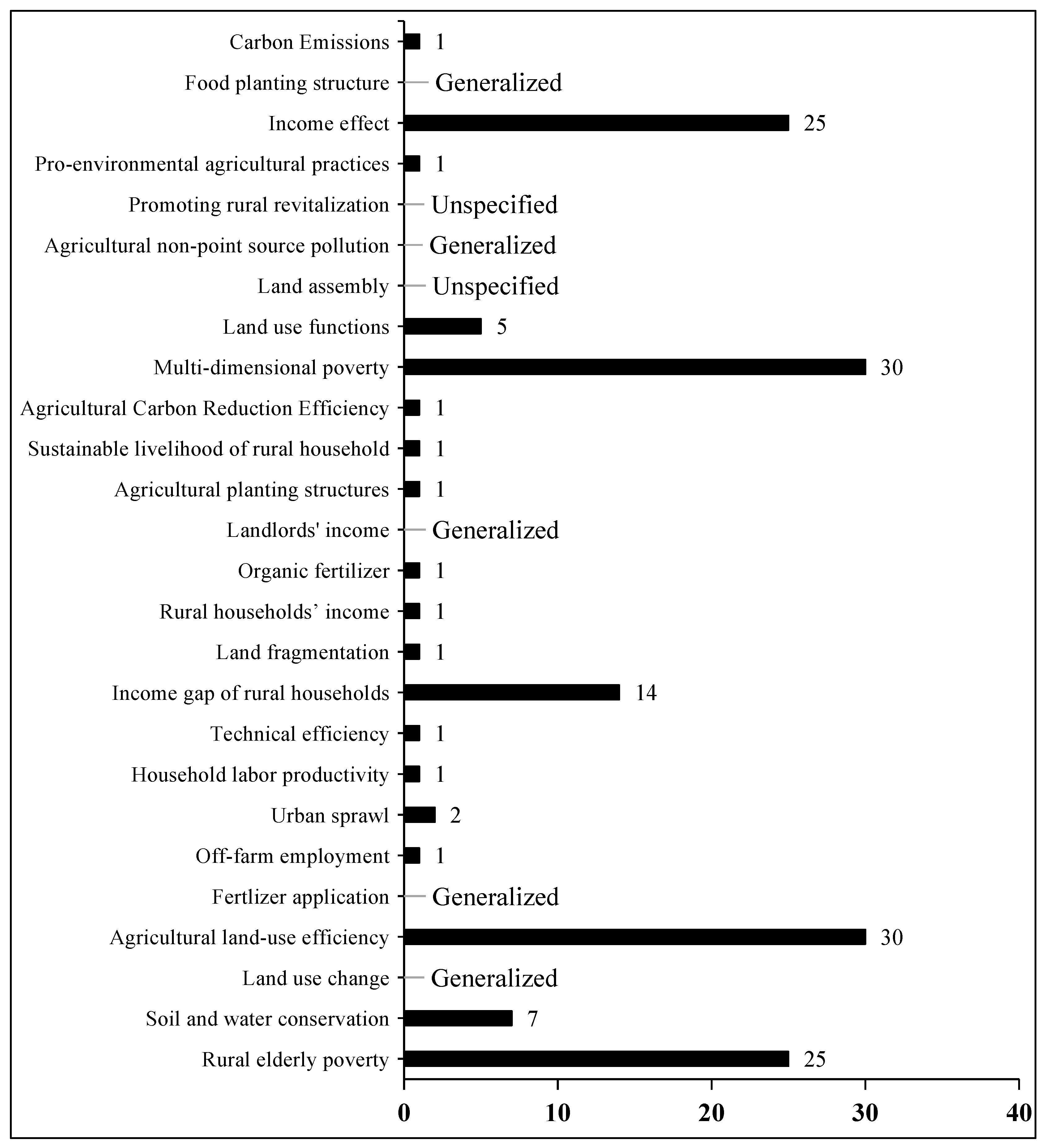

3.2. Topic Categorization

3.3. Research Trends: Temporal and Spatial Context

3.3.1. Temporal Distribution of the Studies

3.3.2. Spatial Distribution of the Studies

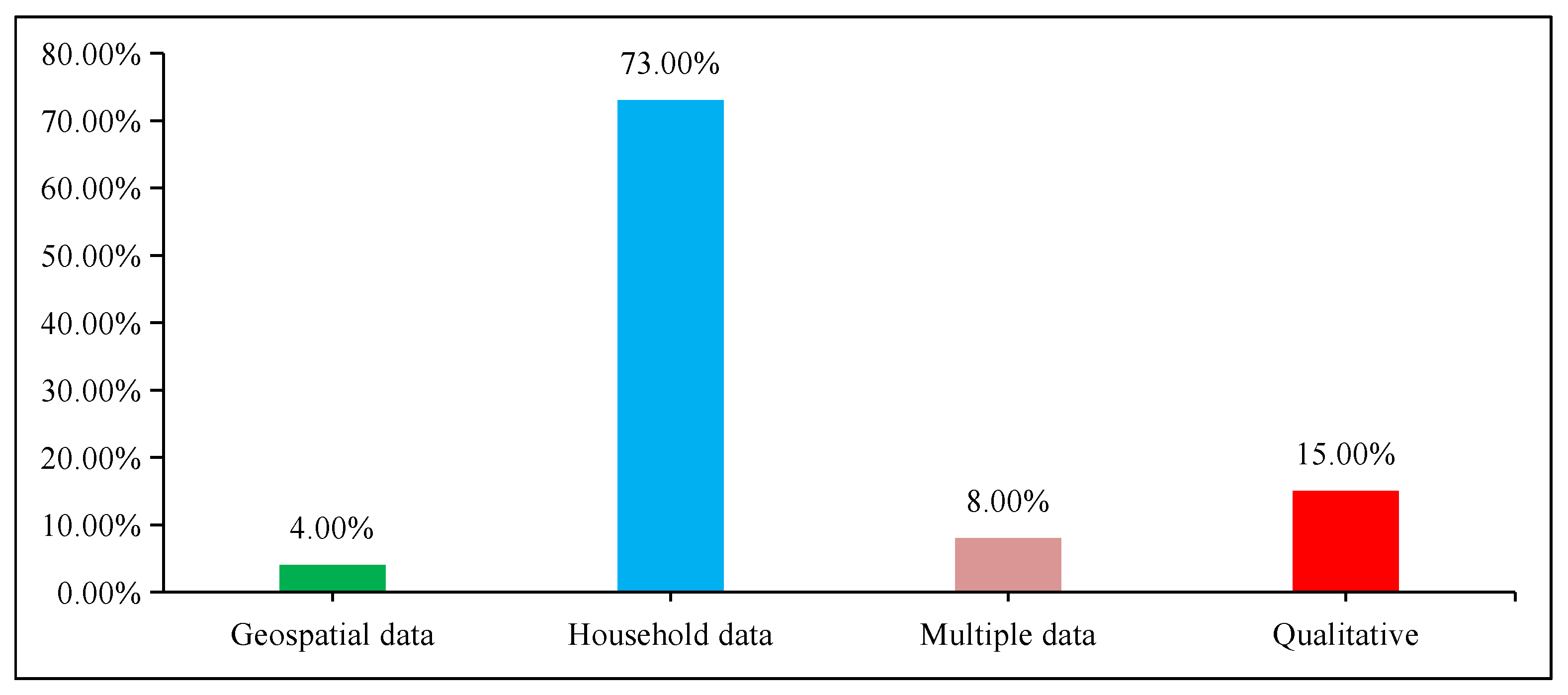

3.3.3. Methodological Based Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Finding-Based Analysis of the Studies

4.1.1. Topical Category 1: The Influence of Farmland Transfer on the Environment

4.1.2. Topic Category 2: The Influence of Farmland Transfer on Agricultural Systems

4.1.3. Topic Category 3: The Influence of Farmland Transfer on Household Income

4.1.4. Topic Category 4: The Influence of Farmland Transfer on Rural Revitalization

4.1.5. Topic Category 5: The Influence of Farmland Transfer on Agricultural Land

4.1.6. Topic Category 6: The Influence of Farmland Transfer on Urbanization (Urban Sprawl)

4.1.7. Topic Category 7: The Influence of Farmland Transfer on Agricultural Labor

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations (UN). The World Population Prospects: Published by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2017. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/desa/world-population-projected-reach-98-billion-2050-and-112-billion-2100 (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Font Vivanco, D.; Sprecher, B.; Hertwich, E. Scarcity-weighted global land and metal footprints. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 83, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I.; Smalley, R.; Hall, R.; Tsikata, D. Narratives of scarcity: Framing the global land rush. Geoforum 2019, 101, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, S. Property as a human right and property as a special title. Rediscussing private ownership of land. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Shi, X.; Fang, S. Property rights and misallocation: Evidence from land certification in China. World Dev. 2021, 147, 105632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambio, Y.; Bouayad Agha, S. Land tenure security and investment: Does strength of land right really matter in rural Burkina Faso? World Dev. 2018, 111, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Huo, X. Impacts of tenure security and market-oriented allocation of farmland on agricultural productivity: Evidence from China’s apple growers. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Lu, D.; Yan, J. Evaluating the impact of land fragmentation on the cost of agricultural operation in the southwest mountainous areas of China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, D.; Yu, Z. Land resource degradation in China: Analysis of status, trends and strategy. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2006, 13, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jin, X.; Xu, W.; Zhou, Y. Evolution of cultivated land fragmentation and its driving mechanism in rural development: A case study of Jiangsu Province. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 91, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Wang, J.Y.; Long, H.L. Analysis of arable land loss and its impact on rural sustainability in Southern Jiangsu Province of China. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Brown, C. Addressing Shortcomings in the Household Responsibility System: Empirical Analysis of the Two-Farmland System in Shandong Province. China Econ. Rev. 2001, 12, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lo, K.; Zhang, P.; Guo, M. Reclaiming small to fill large: A novel approach to rural residential land consolidation in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, C. Land consolidation and rural revitalization in China: Mechanisms and paths. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Yang, C.; Chen, Y. Land transfer in rural China: Incentives, influencing factors and income effects. Appl. Econ. 2020, 52, 5477–5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Paudel, K.; Mi, Y. Factors affecting agricultural land transfer-in in China: A semiparametric analysis. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2018, 25, 1547–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tan, S.; Zhang, X. How do varying socio-economic factors affect the scale of land transfer? Evidence from 287 cities in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 40865–40877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Xu, D.; Zeng, M.; Qi, Y. Does early-life famine experience impact rural land transfer? Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Yong, Z.; Deng, X.; Zhuang, L.; Qing, C. Rural-urban migration and its effect on land transfer in rural China. Land 2020, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Rommel, J.; Feng, S.; Hanisch, M. Can land transfer through land cooperatives foster off-farm employment in China? China Econ. Rev. 2017, 45, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, R.; Lin, Z.; Chunga, J. How land transfer affects agricultural land use efficiency: Evidence from China’s agricultural sector. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udimal, T.B.; Liu, E.; Luo, M.; Li, Y. Examining the effect of land transfer on landlords’ income in China: An application of the endogenous switching model. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, D. Fragmentation reduction through farmer-led land transfer and consolidation? Experiences of rice farmers in Wuhan metropolitan area, China. Agriculture 2021, 11, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Liang, Y.; Fuller, A. Tracing agricultural land transfer in China: Some legal and policy issues. Land 2021, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Will land transfer always increase technical efficiency in China?—A land cost perspective. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Fang, X.; Li, G. Does land tenure fragmentation aggravate farmland abandonment? Evidence from big survey data in rural China. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 91, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Sun, D.; Ma, C. The Impact of Farmland Transfers on Agricultural Investment in China: A Perspective of Transaction Cost Economics, China & World Economy, Institute of World Economics and Politics. Chin. Acad. Soc. Sci. 2019, 27, 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Wen, X.; Qi, X.; Fang, S.; Xu, C. More land, less pollution? How land transfer affects fertilizer application. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, R.; Lu, Q. Land transfer, collective action and the adoption of soil and water conservation measures in the Loess Plateau of China. Nat. Hazards 2020, 102, 1279–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, C.; Chen, L. Research on the impact of land circulation on the income gap of rural households: Evidence from chip. Land 2021, 10, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S.; Wilmsen, B.; Han, X.; Wang, Z.J.-H.; Duan, Y.; He, J.; Li, J.; Lin, W.; Wong, C. Scaling up agriculture? The dynamics of land transfer in inland China. World Dev. 2021, 146, 105563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xie, H. Impact of changes in labor resources and transfers of land use rights on agricultural non-point source pollution in Jiangsu Province, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 207, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Shen, Y. Effects of land transfer quality on the application of organic fertilizer by large-scale farmers in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 105124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hou, X. Structural and efficiency effects of land transfers on food planting: A comparative perspective on north and south of China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Y. How does non-farm employment stability influence farmers’ farmland transfer decisions? Implications for China’s land use policy. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Version 6.0. Cochrane, 2019. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Ou, M.; Gong, J. Farmland transfers in china: From theoretic framework to practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Yang, Y.; Xia, F. Subjective land ownership and the endowment effect in land markets: A case study of the farmland “three rights separation” reform in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, N.; Naveed, S.; Zeshan, M.; Tahir, M.A. How to Conduct a Systematic Review: A Narrative Literature Review. Cureus 2016, 8, e864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Hatab, A.; Cavinato, M.E.R.; Lindemer, A.; Lagerkvist, C.J. Urban sprawl, food security and agricultural systems in developing countries: A systematic review of the literature. Cities 2019, 94, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir Ahmad, N.S.B.; Mustafa, F.B.; Muhammad Yusoff, S.Y.; Didams, G. A systematic review of soil erosion control practices on the agricultural land in Asia. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2020, 8, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Zhu, X.; Heijman, W.; Zhao, K. The impact of land transfer and farmers’ knowledge of farmland protection policy on pro-environmental agricultural practices: The case of straw return to fields in Ningxia, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, S.; Luan, J. Land Circulation, Scale Operation, and Agricultural Carbon Reduction Efficiency: Evidence from China. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2021, 2021, 9288895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lu, S.; Lu, B.; Nie, X. Overt and covert: The relationship between the transfer of land development rights and carbon emissions. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, H.; Zou, C.; Liu, Y. The impact of farmland transfer on rural households’ income structure in the context of household differentiation: A case study of Heilongjiang Province, China. Land 2021, 10, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, J. Poverty alleviation through labor transfer in rural China: Evidence from Hualong County. Habitat Int. 2019, 116, 102402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Chen, J.; Su, C.; Wu, Z.; Yang, L.; Liu, W. Will land circulation sway “grain orientation”? The impact of rural land circulation on farmers’ agricultural planting structures. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, S.; Yuang, D.; Kong, W. Land cooperatives as an approach of suburban space construction: Under the reform of Chinese land transfer market. Front. Archit. Res. 2016, 5, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Luo, X.; Zhang, C.; Song, J.; Xu, D. Can land transfer alleviate the poverty of the elderly? Evidence from rural China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng A min Li, Z. The impact mechanism of rural land circulation on promoting rural revitalization based on wireless network development. Eurasip J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2019, 2019, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xin, L.; Li, X.; Yan, J. Impact of land use rights transfer on household labor productivity: A study applying propensity score matching in Chongqing, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, K. Creating land markets for rural revitalization: Land transfer, property rights and gentrification in China. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 81, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Zhen, L. Impact of rural land transfer on land use functions in Western China’s Guyuan based on a multi-level stakeholder assessment framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Databases | Search Strings with Relevant Keywords | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Web of Science | TS = ((“Land transfer” OR “Farmland transfer” OR “Land circulation” OR “Farmland circulation *)) |

| 2. | Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“Land transfer” OR “Farmland transfer” OR “Land circulation” OR “Farmland circulation *)) |

| Topical Category | Main Findings | Analysis of Results | Main Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| TC1 Environment |

|

| Jia and Lu, (2020) [29]; Wu et al. (2021) [28]; Li and Shen, (2021) [33]; Song et al. (2021) [45]; Lu and Xie, (2018) [32]; Cao et al. (2020) [44]; Wang et al. (2021) [51] |

| TC2 Agricultural System |

|

| Fei et al. (2021) [21]; Liu et al. (2019) [25]; Peng et al. (2021) [49]; Leng et al. (2021) [34] |

| TC3 Rural household income |

|

| Liu et al. (2017) [20]; Huo and Chen, (2021) [30]; Chen et al. (2021) [47]; Udimal et al. (2020) [22]; Guo et al. (2019) [48]; Peng et al. (2020) [49]; Kan, (2021) [53]; |

| TC4 Agricultural land |

|

| Zhang and Chen, (2021) [23]; Xue and Zhen, (2018) [55]; Zhou et al. (2021) [24] |

| TC5 Urbanization |

|

| Dang et al. (2016) [41] |

| TC6 Agricultural labor |

|

| Wang et al. (2017) [53] |

| TC7 Rural revitalization |

| FLT is seen as a mechanism to achieve the government’s priority agenda of rural revitalization. | Wang et al. (2021) [51]; Li et al. (2021) [7]; Zheng and Li, (2019) [52] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abatechanie, M.; Cai, B.; Shi, F.; Huang, Y. The Environmental and Socio-Economic Effect of Farmland Management Right Transfer in China: A Systematic Review. Land 2022, 11, 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081333

Abatechanie M, Cai B, Shi F, Huang Y. The Environmental and Socio-Economic Effect of Farmland Management Right Transfer in China: A Systematic Review. Land. 2022; 11(8):1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081333

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbatechanie, Meseret, Baozhong Cai, Fang Shi, and Yuanji Huang. 2022. "The Environmental and Socio-Economic Effect of Farmland Management Right Transfer in China: A Systematic Review" Land 11, no. 8: 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081333

APA StyleAbatechanie, M., Cai, B., Shi, F., & Huang, Y. (2022). The Environmental and Socio-Economic Effect of Farmland Management Right Transfer in China: A Systematic Review. Land, 11(8), 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081333