Abstract

Growing demand for National Forests (NFs) recreational activities makes it crucial to understand the attitudes towards valuing public recreational resources and the potential conflicts with other functions of the forests. The study was conducted to identify the primary drivers influencing individual participation in outdoor recreation on NF lands in the southeastern region of the US among participants of various socioeconomic backgrounds. The study was based on the 2010–2014 dataset of fourteen NFs across thirteen states in the Southeastern USA—retrieved from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Different statistical models and statistical analyses were utilized for the study. The statistical results revealed that individual needs for relaxation were the main driver for participation in forest recreation for the whole sample and pulled data (approximately 52% of the participants). It has been noted that the drivers varied depending on the forest. The personal need for mental development was the least valued driver with only 2%. Some significant differences were observed by gender, age category, and income level. The study results have practical importance for different stakeholders such as tourism operators, the USDA Forest Service, and local authorities.

1. Introduction

In recent centuries, human societies have increased the value they place on leisure time, increasing the demand for open areas for outdoor recreation on National Forest (NF) lands [1]. NFs provide a combination of interrelated beneficial outcomes to an individual or community, including creating a new appreciation of the environment, fostering an environment for family togetherness, and providing an escape from everyday stress. According to the USDA Forest Service, the overall annual number of NF visits in 2016 was 148.1 million [2]. Approximately 84% of the visitors indicated recreation opportunities provided by NF as the primary reasons for their trip to an NF [2]. Therefore, outdoor recreation is one of the most widely recognized ecosystem services (ES) provided by forests and grasslands.

It is estimated that the surplus demand for NFs recreation negatively impacts the quantity and the quality of forest recreation values and puts pressure on many other ecosystem services these forests provide. Studies have found that high levels of recreational use are endangering the ecological status of these forests [3]. A growing body of literature [4,5] has recognized that even low levels of recreational use in national forest lands have resulted in resource degradation. Intensive forest visitation can cause severe ecological impacts, such as soil compaction and erosion, water pollution, and wildlife disturbances. It can produce social impacts such as overcrowding, conflict, aesthetic degradation, and changes to the managerial environment [6].

Within this context, there is a need to understand attitudes towards valuing public recreational resources and potential conflicts with other functions of the forests, such as biodiversity and consumption goods. It is important to understand that to satisfy their primary needs, each person perceives different tangible and non-tangible benefits provided by the environment that can be formalized as “values” of the landscapes’ functions for people [7]. Previous studies indicate that various landscape values have different degrees of importance for people [8,9]. The held values are defined as the most stable and basic elements of cognizance that a particular mode of activity is preferable for a specific person [10]. Researchers often conceptualize such perceptions as values of the landscape functions [11]. Some results indicate that the most important motives to visit a specific area in the case of nature-based tourism are clean surroundings and the landscape environment in general [8]. Similarly, a study across six sites in different European countries also identified these values related to outdoor recreation and aesthetics to have a high importance for visitors [9]. However, there is another critical marginal benefit to visitors that should be considered and depends on several factors, including social value, socioeconomic and demographic factors, quality of the site, and the cost involved in visiting other competing locations. According to Valles-Planells [12], landscapes have self– and social–cultural aspects of their contribution to people’s well-being.

Some studies have considered four dimensions of human well-being related to landscapes: enjoyment, personal fulfillment, health, and social fulfillment [13]. Landscape services related to humans’ health are divided into services related to mental health and services related to physical health [12]. Also, within personal self-fulfillment, the researchers distinguished educational and scientific resources and a spiritual experience provided by forest landscapes [14]. Marcus [15] discussed the advantages of healing landscapes in healthcare facilities by providing examples related to patient-particular gardens, green spaces, parks, etc. In their report, they concluded that National Forests have historical, aesthetic, and cultural values for recreational activities and visitors with different forest value priorities who have different recreation service demands.

In the United States, the demographic structure of the US population is constantly changing. Increased ethnic diversity and an aging population present unique challenges [16]. The ‘new’ elderly are likely to have more time and money but will likely be less physically fit and have special requirements. Likewise, the ‘new’ ethnically diverse participants are likely to have differing perceptions, attitudes, values, and interpretations regarding natural resources, but little is often known about their demand for outdoor recreation [17]. In general, improved socioeconomic prosperity among recreationists offers multiple opportunities to travel to NF areas [18]. However, the requirements of lower-socioeconomic-class individuals may differ from those of their wealthier counterparts.

The need to develop knowledge of the intensity and forms of recreational usage and users’ perceived values and behavior in NF areas is now more important than ever. Indeed, several studies have examined the actual usage of NF areas and NF recreation. However, to date, limited research studies have been carried out in reference to NFs in the Southeastern United States. Similarly, studies that consider ethnicity-based differences or those that explored socioeconomic class to explain trip-taking behavior in recreation demands on NF lands are also limited. Therefore, there has been an increased demand for information from researchers and NF managers on the actual usage of NF areas (by different population groups), followed by the growing awareness of the importance and complexity of the services NFs provide. Understandably, an investigation of the main drivers for individuals to participate in NFs recreation is relevant to developing tourism on NFs lands.

The main objective of this research was to assess the outdoor recreational value of NFs in the Southeastern United States and evaluate the choices and behavior of visitors to these forests based on demographic and social characteristics. Moreover, this research evaluated recreationists’ ethnicity-based differences and explored socioeconomic class in demand models to explain trip-taking behavior for recreation in these forests. It was accomplished by identifying the main drivers for individuals to participate in recreational activities on NF lands in the Southeastern United States, estimating the most important drivers and quantifying and qualifying the recreational values on NF lands. The main drivers and barriers for individuals to participate in NF recreation were investigated using the Ecosystem Services (ES) framework [19,20].

Based on the literature presented above, the hypothesis for the study was proposed as follows:

What are the primary drivers influencing individual participation in outdoor recreation on National Forest lands in the southeastern region of the US among participants of various socioeconomic backgrounds? (H1)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

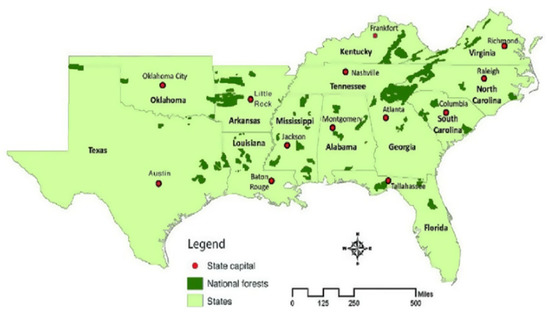

This study selected fourteen National Forests (NFs) in the Southeastern USA with different characteristics. These NFs are distributed across 13 states in Region 8 (Figure 1). They represent recreational sites with different landscapes and various recreational demands (Table 1), such as bicycling, hiking, swimming, and canoeing for visitors. The study also included the “Land Between the Lakes” NF, a designated UNESCO Biosphere reserve in Kentucky and Tennessee between Lake Barkley and Kentucky Lake [2]. Five wildlife areas are also located in these NFs. These wildlife areas provide additional fishing, boating, camping, hunting, hiking, horseback riding, picnicking, and wildlife viewing as recreational activities. Numerous species of birds, fish, mammals, amphibians, and reptiles inhabit these NFs. People can view rare and endangered species in these wildlife areas, such as the flattened musk turtle, the gopher tortoise, and the red-cockaded woodpecker. Elevations and landscapes in these NFs differ widely, ranging from 100 feet in the Coastal Plain to over 2100 feet in the Appalachian areas [2].

Figure 1.

Map reflecting the spatial distribution of the National Forests in the Southeastern region (source: https://www.fs.usda.gov/alabama/ forest, accessed on 28 March 2017).

Table 1.

Matrix of National Forests in the Southeast United States of America.

2.2. Data Collection

The 2010–2014 National Visitor Use Monitoring (NVUM) dataset for this research was provided by the USDA Forest Service in 2018. The objectives of the NVUM program were: First, to estimate the number of recreation visits to national forests and, second, to produce descriptive information about visitation, including activity participation, demographics, visit duration, measures of satisfaction, and trip spending connected to the visit. This dataset was based on a survey of over 155,000 visitors at 7532 different sites across 120 national forests during 1368 days of sampling between January 2000 and September 2003 [21]. Among the recorded visitors, 136,584 agreed to be interviewed (an 88% participation rate).

Interviewers (typically Forest Service employees), trained by the national training and certification program attendees, conducted face-to-face, on-site interviews using a 4-page National Visitor Use Survey forms. The survey form had questions relating to demographics and visit descriptions and six socioeconomic-related questions. Moreover, one-third of the forms had 16 satisfaction and 14 satisfaction question elements. The duration of the interviews varied between 8 and 12 min [2].

The surveys used a double sampling method with a two-step approach. In the first step, the survey days and sites were randomly selected from a stratified set of days and recreational sites, with strata defined by site type and daily exit volume. The exact survey location was determined by road/weather conditions, type of road, and stopping distance. Interviews were given to randomly selected vehicles or groups that stopped at the randomly selected sites. In the second step, an interview was conducted with the individual who had the most recent birthday among the individuals in the randomly selected vehicle exiting the selected recreational site. For each chosen site day, six hours of exit interviews were conducted. Site-visit estimates were acquired for each sample day, averaged by strata, and then expanded by a stratified-sampling weight. The results from the NVUM program were used to construct NVUM data. The NVUM quality-assurance-check procedure was implemented to ensure the quality of the survey data [2].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The main objective of this study was to investigate the primary drivers for individuals participating in forest recreational activities at the NFs. First, the proportions of the respondents that indicated each driver were compared using pairwise techniques. The primary drivers are defined according to the main landscape values adapted to NFs recreation [14]. According to Garcia-Martin et al. [14], the values describe the sociocultural perception of landscape functions. National Forest recreation values can be defined as the sociocultural perception of National Forest recreation functions. The relationships between the main drivers for individuals to participate in Alabama’s National Forest Recreation, the main values for National Forest Recreation, and the corresponding questionnaire items are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Relationships between main drivers for individuals to participate in Alabama’s National Forest Recreation and corresponding questionnaire items.

Respondents had the opportunity to indicate more than one reason for participation in forest recreation. Therefore, groups of respondents that reported two different reasons could overlap. In general, ten possible pairs were compared, considering partial overlapping. Statistics for the given test were calculated according to Derrick, Toher, and White [22]:

With , p1 and p2 are compared proportions;

n1 and n2 represent non-overlapping samples; and

n12 is the length of the overlapping part.

The calculated z-value is often compared to the p-value for making decisions. The significance level in this study was set at 0.05. Thus, if the p-value was less than 0.05, the null hypothesis was rejected. To estimate the significance of the main barriers, a paired t-test was used, given that that respondents estimated the significance of all barriers. The corresponding t-statistics were calculated using the formula below:

where:

is a mean of differences in scores for two barriers;

is the standard deviation of the differences; and

n is the sample size.

Afterwards, the main clusters of the respondents related to drivers for forest recreation were identified using K-mean methods. Considering the social descriptive characteristics of the respondents, the social-demographic portrait of each cluster was determined. Multiple discriminant analyses were conducted to test the accuracy of the cluster solution using discriminate functions, the significance of which was tested by Wilks’s Lambda test, Chi-square test, canonical correlation statistic, and univariate F-test.

To estimate the significance between the main sociodemographic groups of the visitors, the t-test with a level of significance of 0.05 was used:

where:

() is the difference between the observed means of the two groups;

() is the difference of the hypothesized means; and

and are the variances of the two groups.

One-way ANOVA was used when there were more than two groups to compare. It is a generalization of the independent sample t-test, but the test statistic of ANOVA is based on the variances between and within groups:

where SSB, MSB, SSW, and MSW are between the sum of squares, between mean square, within the sum of squares, and within the mean square. K represents the number of groups and n represents the sample size. As usual, the p-value was used for final decisions.

Also, to explore the association between respondents’ social-demographic characteristics and forest recreation values, the corresponding contingency tables were used. Then, χ2 was applied to identify statistically significant associations. The χ2 value was calculated using Equation (5):

where:

and are the observed and expected values in ith position in the contingency table.

The p-value of χ2 was calculated considering that it was distributed as a Chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom , where represents the number of columns in the contingency table and r is the number of rows. If the p-value was larger than the significance level, that indicated no statistically significant difference across the investigated groups.

3. Results

The main driving factors influencing individual engagement in recreational activities at National Forests varied considerably with different sociocultural characteristics of the respondents, such as gender, age, race, and income in the southeastern region of the US.

3.1. Primary Drivers

The primary drivers were defined according to the main landscape values, which were adapted to NFs recreation values [14]. According to Garcia-Martin [14], these values describe the sociocultural perception of landscape functions. NF recreation values can be defined as the sociocultural perception of NF recreation functions. The relationships between the main drivers for individuals to participate in NF recreation in the southeastern region of the US, the main values of National Forest Recreation, and the questionnaire items are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Relationships between main drivers for individuals to participate in Southeastern National Forest Recreation, main values of National Forest Recreation, and questionnaire items.

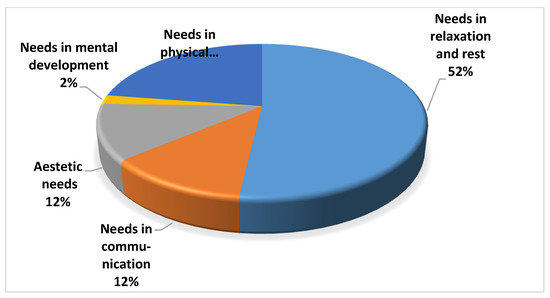

First, the main drivers for all respondents were investigated for pulled data and among forests (Table 4). As reported in Table 4, Individual needs in relaxation and resting was identified as the main driver for participation in forest recreation for the whole sample and pulled data, as reported by 52% of the respondents (Figure 2). Personal needs in relaxation and rest were identified as the main driver to visit forests across 13 of 15 NFs investigated. Personal needs in physical development was also reported to be the main driver in the following forests (William B. Bankhead, Talladega, Tuskegee, Conecuh), (Ozark), and (Francis Marion, Sumter); while it was the second most important driver at eight forests, including (Daniel Boone), (Cherokee), (Apalachicola, Osceola, Ocala), (Kisatchie), (George Washington-Jefferson), (Nantahala, Pisgah, Uwharrie, Croatan), (Davy Crockett, Angelina, Sabine, Sam Houston, Caddo Lyndon B., Johnson Grasslands), and (Land Between the Lakes); the third most important driver for (Chattahoochee-Oconee), (De Soto, Homochito, Bienville, Delta, Tombigbee, Holly Springs), and (St. Francis, Ouachita) forests; and the fourth most important driver at (El Yunque) forest. Other drivers were found to be relatively less significant, e.g., Personal needs in mental development was ranked fifth in importance for all forests—excluding (El Yunque) where it was ranked third. The Personal needs for communication and Aesthetic needs ranked third and fourth, respectively, across all NFs investigated.

Table 4.

Main drivers for recreation activities across forests (all visitors).

Figure 2.

Percentage distribution of the respondents among the main drivers for forest recreation activities.

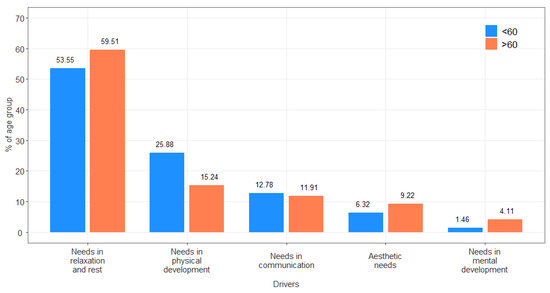

3.2. Primary Drivers by Age

Significant drivers for two main age groups, persons older than 60 years and persons younger than 60 years, were also identified. The percentage distribution of visitors by these age groups among the main drivers across the forests are reported in Table 5. According to Figure 3, significant differences are observable between the two age groups in Personal needs for relaxation and Needs in physical development drivers. The Chi-square test indicated that Personal needs in relaxation and rest were the main driver for a larger proportion of the older visitors to NFs compared to younger visitors (χ2 = 26.75, p < 0.001). Needs in physical development was the main driver for a significantly larger proportion of younger visitors to NFs compared to older visitors (χ2 = 116.43, p < 0.001). Personal needs in mental developments and Aesthetic needs were also identified to be an essential driver for older visitors (χ2 = 68.05, p < 0.001 and χ2 = 24.61, p < 0.001).

Table 5.

The results of the Chi-squared test for between-group (age) comparisons across forests.

Figure 3.

Percentage distribution of the main drivers for forest recreation activities among the respondents from the different age groups.

Across all forests, four forests (William B. Bankhead, Talladega, Tuskegee, Conecuh), (Chattahoochee-Oconee), (Ozark), and (El Yunque) did not show statistical significance at the level of <0.05 differences in the importance of main drivers between age groups (Table 5).

The forests of (Apalachicola, Osceola, Ocala) (48.42% vs. 34.79%, χ2 = 9.95, p = 0.002), (Kisatchie) (58.26% vs. 43.43%, χ2 = 8.85, p = 0.003), (Davy Crockett, Angelina, Sabine, Sam Houston, Caddo Lyndon B., Johnson Grasslands) (74.51% vs. 60.40%, χ2 = 8.85, p = 0.001), and (Land Between the Lakes) (58.11% vs. 60.40%, χ2 = 3.91, p = 0.048) indicated the larger importance of personal needs in relaxation and rest as the main driver to visit the forest for the older age group (Section S2 in Supplementary Materials). No significant differences between age groups were found for this driver for the rest of the NFs.

Personal needs in physical development was another important driver to visit the forests for younger visitors in the case of NFs:

(Cherokee) (31.43% vs. 19.61%, χ2 = 11.63, p < 0.001);

(Apalachicola, Osceola, Ocala) (38.80% vs. 23.27%, χ2 = 8.89, p = 0.003);

(Kisatchie) (27.62% vs. 13.91%, χ2 = 9.79, p = 0.002);

(Kisatchie) (19.97% vs. 6.42%, χ2 = 7.412, p = 0.006);

(Nanatahala, Pisgah, Uwharrie, Croatan) (15.07% vs. 5.70%, χ2 = 38.25, p < 0.001);

(Francis Marion, Sumter) (48.25% vs. 29.46%, χ2 = 12.70, p < 0.001);

(Davy Crockett, Angelina, Sabine, Sam Houston, Caddo Lyndon B., Johnson Grasslands) (19.88% vs. 9.15%, χ2 = 9.72, p = 0.002); and

(Land Between the Lakes) (28.47% vs. 5.41%, χ2 = 17.25, p < 0.001).

No significant differences in Personal needs in physical development between two age groups were found in the case of other forests. According to Section S2 in Supplementary Materials, Needs in communication exhibited a significant difference in the importance between younger (13.33%) and older (22.02%) visitors in only the NF of (De Soto, Homochito, Bienville, Delta, Tombigbee, Holly Springs) (13.33% vs. 22.02%, χ2 = 4.72, p = 0.03). Personal needs in aesthetic development were an essential driver to visit NFs for older visitors in the case of three forests: (Daniel Boone) (11.32% vs. 6.34%, χ2 = 5.34, p = 0.02), (Nantahala, Pisgah, Uwharrie, Croatan) (9.60% vs. 3.98%, χ2 = 11.77, p < 0.001), and (Francis Marion, Sumter) (16.94% vs. 8.39%, χ2 = 7.15, p = 0.008). Finally, Personal needs in mental development were a more essential driver to visit NFs for older visitors in the case of five forests: (Daniel Boone) (3.77% vs. 0.35%, χ2 = 21.29, p < 0.001), (Cherokee) (1.47% vs. 0.26%, χ2 = 5.80, p = 0.02), (George Washington-Jefferson) (3.88% vs. 0.40%, χ2 = 20.13, p < 0.001), (Nantahala, Pisgah, Uwharrie, Croatan) (4.80% vs. 2.14%, χ2 = 11.63, p < 0.001), and (Francis Marion, Sumter) (14.30% vs. 3.50%, χ2 = 19.14, p < 0.001). The differences in the importance of both the above-mentioned drivers to visit NFs were insignificant at the level of 0.05 in the case of other forests (Table 5).

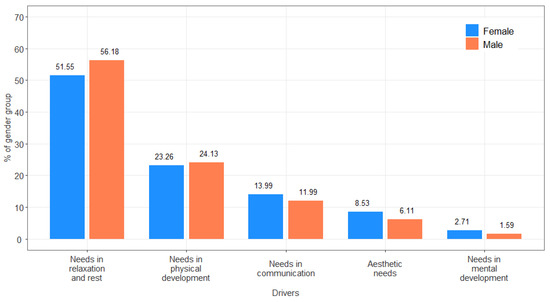

3.3. Recreation Drivers by Gender

As shown in Figure 4, the largest difference between males and females was observed for Needs in relaxation and rest. This driver had significantly larger importance for males in comparison with females (56.18% vs. 51.50%, χ2 = 23.31, p < 0.001). There were no significant differences between gender groups for Needs in physical development (males 24.13% vs. females 23.26%, χ2 = 1.09, p < 0.256). The other three drivers had larger importance for females in comparison with males. Personal needs in communication was reported as the main driver by 13.99% of females compared to 11.99% of males (χ2 = 9.60, p = 0.002). Aesthetic needs was reported as the main driver by 8.53% of females and 6.11% of males (χ2 = 24.21, p < 0.001). Finally, Mental development was reported as the main driver to visit NFs by 2.71% of females and 1.59% of males (χ2 = 17.10, p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Percentage distribution of the main drivers for forest recreation activities among the respondents from the different gender groups.

Table 6 presents gender differences in the importance of main drivers for visits to NFs across all forests selected for this study. According to Table 6, gender differences were more clearly observed for Needs in relaxation and rest and Aesthetic needs. The first driver had a higher importance for males in comparison with females in seven forests, while the second had higher importance for females in six forests (Section S2 in Supplementary Materials). A contradictory result was observed for the driver, Needs in physical development; this driver had higher importance for females in six forests (Daniel Boone), (Kisatchie), (De Soto, Homochito, Bienville, Delta, Tombigbee, Holly Springs), (William B. Bankhead, Talladega, Tuskegee, Conecuh), (Davy Crockett, Angelina, Sabine, Sam Houston, Caddo Lyndon B., Johnson Grasslands), and (El Yunque), while it had higher importance for males at (George Washington-Jefferson), (Nanatahala, Pisgah, Uwharrie, Croatan), and (Francis Marion, Sumter) NFs. Needs in physical development exhibited insignificant differences between gender groups for pulled data. Needs in communication were the most important driver to visit NFs for females in comparison with males (Section S2 in Supplementary Materials) for five forests: (Apalachicola, Osceola, Ocala), (Kisatchie), (De Soto, Homochito, Bienville, Delta, Tombigbee, Holly Springs), (Davy Crockett, Angelina, Sabine, Sam Houston, Caddo Lyndon B., Johnson Grasslands), and (Land Between the Lakes).

Table 6.

(a)The results of the Chi-squared test for between-group (gender) comparisons across forests. (b) The results of the Chi-squared test for between-group (ethnicity) comparisons across forests.

3.4. Recreation Drivers by Ethnicity

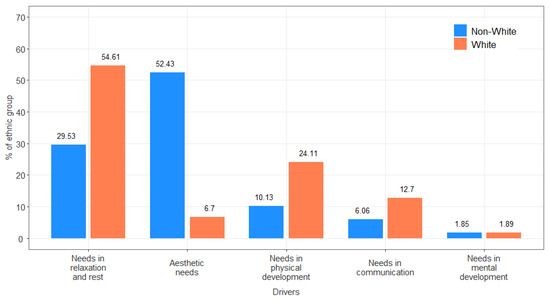

Considering that most of the visitors were white (more than 96%), all visitors were divided into two ethnicity groups: “white” and “non-white” (which included reported races of Asian, Black, Native American, and Pacific Islander). The importance of the main drivers to visit NFs for recreation by ethnic groups across forests is reported in Table 6 and shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Percentage distribution of the main drivers for forest recreation activities among the respondents from the different ethnic groups.

According to Figure 5, ethnicity significantly affects the importance of the main drivers. The ranks of the main driver for “white” corresponds to the ranks for all samples. The primary driver for white users is Personal needs in relaxation and rest, followed by Needs in physical development, Needs in communication, Aesthetic needs, and Needs in mental development. However, for non-white users, Aesthetic needs is the primary driver to visit NFs. Personal needs in relaxation and rest was ranked second, followed by Personal needs in physical developments, Needs in communication, and Needs in mental development. As shown in Figure 5, Personal aesthetic needs had a much larger importance for non-whites (52.43%) in comparison with whites (6.70%), (χ2 = 2525.83, p < 0.001). The importance of Personal needs in relaxation and rest was essentially higher for whites (54.61%) in comparison with non-whites (29.53%), (χ2 = 314.60, p < 0.001). Large differences between ethnic groups were observed in Needs in physical development (whites—24.11, non-whites—10.13) and Personal needs in communication (whites—12.70%, non-whites—6.06%), which were smaller than the first above-noted and were highly significant (χ2 = 139.56, p < 0.001 and χ2 = 52.16, p < 0.001, accordingly). The differences in Needs in mental development were statistically insignificant. While the differences in the importance of Aesthetic need between the two ethnic groups were highly significant in the case of all forests (Table 6).

Personal needs in relaxation and rest had a lower importance for non-whites in comparison with whites for visits to NFs for a majority of the forests (10 forests). Also, Personal needs in physical development were a less important driver to visit NFs for non-whites in comparison with whites in the case of 11 forests (Table 6). The lower importance of Personal needs in communication for non-whites compared with whites was found in the case of five forests. No statistically significant differences in the importance of the Personal needs in mental development between ethnic groups were found for all forests (Table 6).

3.5. Recreation Drivers by Income

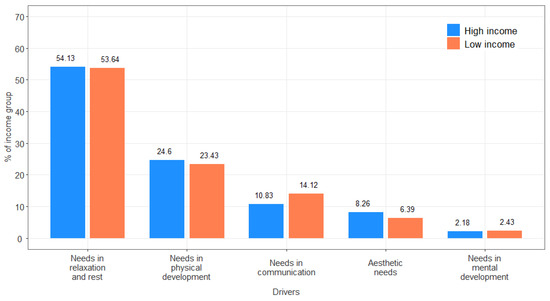

The visitors were asked about their income within six categories, which were defined as: “under 25 k”, “25–49 k”, “50–74 k” “75–99 k” “100–149 k”, “150 k+”. However, most of the visitors didn’t report their income (more than 70% of the missing data). Considering the range of 0–150 and relatively small sample size, all respondents were combined into two groups: lower-income group (income < 75,000 USD) and higher-income group (income ≥ 75,000 USD).

As presented in Figure 6, the ranks by the importance of the main drivers for different income groups are the same. The main driver for both income groups was Personal need in relaxation and rest, followed by Personal needs in physical development, Needs in communication, Aesthetic needs, and Needs in mental development.

Figure 6.

Percentage distribution of the main drivers for forest recreation activities among the respondents from the different income groups.

As shown in Figure 6, Personal needs in communication had a larger importance for the lower-income group (χ2 = 6.62, p = 0.01). The between-group differences for the importance of other drivers were statistically insignificant (χ2 = 0.07, p = 0.795 for needs in relaxation and rest; χ2 = 3.71, p = 0.054 for aesthetic needs; χ2 = 0.18, p = 0.673 for needs in mental development; and χ2 = 0.52, p = 0.470 for needs in physical development).

According to Table 7, the Personal needs in relaxation and rest had a higher importance for the lower-income group in the case of several forests, including (Apalachicola, Osceola, Ocala) and (Davy Crockett, Angelina, Sabine, Sam Houston, Caddo Lyndon B., Johnson Grasslands). Personal needs in physical development had a larger importance for the higher-income group in the case of the (St. Francis, Ouachita) NF, and Aesthetic needs was important in the case of the (Ozark) NF. Personal needs in mental development were higher for the lower-income group in the case of the (El Yunque) NF. All other between-group differences across forests were not statistically significant.

Table 7.

The results of the Chi-square test for between-group (income) comparisons across forests.

Thus, despite the importance of the internal group differences, a common pattern was observed for almost all social-demographic groups of the visitors. The primary driver for visits to NFs was reported to be Personal needs in relaxation and rest, followed by Personal needs in physical development and Personal needs in communication, which were ranked second and third by importance. Personal aesthetic needs and Personal needs in mental development were the last ones ranked by importance. However, for the non-white group, Personal aesthetic needs were the primary driver to visit NFs, followed by Personal needs in relaxation and rest, Personal needs in physical developments, Needs in communication, and Needs in mental development. This pattern was observed for most of the forests. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported only in the case of ethnicity.

4. Discussion

The growing demand for NFs recreational activities fuels the need to understand attitudes towards valuing public recreational resources as well as the potential conflicts with other crucial functions of the forests. This study mainly evaluated the outdoor recreational value of NFs in the Southeastern United States and assessed the visitors’ behaviors and choices for evaluating recreationists’ ethnicity-based differences and exploring socioeconomic class in demand models. Our objective was to identify the primary drivers for visitors to NF lands in the southeastern region of the US. Although the drivers varied with the forests, examining the main drivers for all respondents for pulled data and all forests considered in this study revealed, based on the statistical results, that Individual needs in relaxation was the main driver for participation in forest recreation (approximately 52% of the participants). The Personal needs in mental development were observed to be the least important driver, with only 2% of respondents. Our findings are persistent with other studies [12,24] that considered landscape services that satisfy humans’ fundamental needs, which are related to health, social well-being, personal self-perception, and personal realization.

Our study also identified that the most significant difference between males and females is Personal needs in relaxation and rest. This driver had a significantly larger importance for males in comparison with females. However, no significant differences between gender groups for the second important driver, Personal needs in physical development, was observed in this study. Similarly, the results obtained by Mäntymaa et al. [25] indicate that there is enough evidence to consider that landscape values have a different importance for different gender groups.

In a study, Brown [26] reported that the importance of landscape values in Kangaroo Island, South Australia, differs between tourists and residents. Additionally, a significant association has been found between respondents’ age and landscape values [14]. Our study found that Personal needs in mental developments and Aesthetic needs were an important driver for older visitors to visit NFs, while Personal needs in physical development were a more important driver for younger visitors. On the contrary, some research indicated no differences in the perception of values related to ecosystem services across age, gender, and different professions [27]. Several studies also showed that recreational satisfaction might positively impact future behavioral intentions, behaviors, and post-behaviors [28,29,30]. Lee [31] examined the ecotourism behavioral model of NFs recreation areas in Taiwan. Garcia-Martin et al. [14] investigated landscape values across six sites in different European countries and found that values related to outdoor recreation and aesthetics had a high importance for visitors. Some results indicate that the most important motives to visit a specific area in the case of nature-based tourism are clean surroundings and the landscape environment in general. Our study also found that Personal needs in relaxation and rest were the main driver to visit forests across 13 of the 15 investigated National Forests.

Based on these results, it is crucial to maintain, adjust, and expand existing or design new opportunities for nature and forest recreation, especially in areas where such opportunities have been missing to date. Emphasis needs to be placed on protecting, enhancing, and building new nature areas and forests with the potential to provide restorative effects, thereby considering and building on central pathways that mediate the effects of nature and forests on human health.

At the same time, the increase in NF visits as a coping tool to handle health and well-being issues would not incur substantial public healthcare costs, but it could contribute significantly to enhanced public health. The findings from this paper imply that forest visits may be used as an effective tool to alleviate well-being issues in the face of perceived health risks. Therefore, a dialogue among forest owners, regulators, public health administrators, policy-makers, health officials, and all stakeholders should be facilitated to ensure the pursuit of a closer-to-nature, multiple-use-oriented land and forest management approach.

5. Conclusions

The growing demand for NFs recreational activities makes understanding the attitudes towards valuing public recreational resources as well as the potential conflicts with other functions of the forests crucial. Indeed, several studies have examined the actual usage of NF areas and NF recreation. These studies consisted mainly of evaluating the outdoor recreational value of NFs in the Southeastern United States and assessing the visitors’ behaviors and choices by evaluating recreationists’ ethnicity-based differences and exploring socioeconomic class in demand models. The research model scrutinized the possible associations of five drivers (Needs in relaxation and resting, Needs for communication, Individual aesthetic needs, Personal mental development, and Needs in personal physical development) to participate in outdoor activities and NF recreation. The statistical results revealed that Individual needs in relaxation and rest is the main driver for participation in forest recreation for the whole sample and pulled data (approximately 52% of the participants). It has also been noted that the drivers vary with the forests. The Personal needs in mental development was found to be the least important driver, reported by only 2% of respondents.

Some study limitations are required to be acknowledged. First, the study period was limited to 2010–2014. A larger study period may make the results and findings more accurate. By considering a larger study period, it may allow us to fix a reference event to compare the results. The majority of the participants’ ethnicity was white, and this may bias the analysis based on this criterion; including more ethnicity groups may impact the results significantly. Also, missing data is problematic. Applying an imputation method rather than excluding missing data may make the results more accurate. Another future recommendation is to include season as a criterion to investigate its impact on the main drivers of NFs visits and on outdoor activities. Indeed, analyzing the similarities and differences across and within seasons can also provide interesting findings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land11081301/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.R.G. and S.H.; Formal analysis, R.J.; Investigation, R.J.; Resources, T.B.; Supervision, K.N. and C.S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded, in part by the USDA-McIntire Stennis (ALAX-011-M3914) and the Biological and Environmental Sciences Department, Alabama A&M University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Knetsch, J. Outdoor Recreation Demands and Benefits. Land Econ. 1963, 39, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Forest Service National Visitor Use Monitoring Survey Results National Summary Report. 2016. Available online: https://www.fs.fed.us/recreation/programs/nvum/pdf/5082016NationalSummaryReport062217.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Brabyn, L.; Brown, G. SIRC NZ 2013—GIS and Remote Sensing Research Conference University of Otago. In Proceedings of the Using GIS to Survey Landscape Values, Dunedin, New Zealand, 29–30 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hammitt, W.E.; Cole, D.N.; Monz, C.A. Wildland Recreation: Ecology and Management; John and Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, Y.F.; Marion, J.L. Recreation impacts and management in wilderness: A state-of-knowledge review. In Proceedings of the Wilderness science in a time of change conference-Volume 5: Wilderness ecosystems, threats, and management, Missoula, MT, USA, 23–27 May 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Alberini, A.; Longo, A. Combining the travel cost and contingent behavior methods to value cultural heritage sites: Evidence from Armenia. J. Cult. Econ. 2006, 30, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Riper, C.J.; Kyle, G. Capturing multiple values of ecosystem services shaped by environmental worldviews: A spatial analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 145, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Mäntymaa, E.; Ovaskainen, V. Demand for Enhanced Forest Amenities in Private Lands: The Case of the Ruka-Kuusamo Tourism Area, Finland. For. Policy Econom. 2014, 47, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, M.; Bieling, C.; Fagerholm, N.; Gounaridis, D. The Landscape Values: Place and Praxis; Centre for Landscape Studies, NUI Galway: Galway, Ireland, 2016; pp. 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Freedom of the Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Pirikiya, M.; Amirnejad, H.; Oladi, J.; Solout, K.A. Determining the recreational value of forest park by travel cost method and defining its effective factors. J. For. Sci. 2016, 62, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valles-Planells, M.; Galiana, F.; Van Eetvelde, V. A classification of landscape services to support local landscape planning. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos, D.; Mariel, P. Contingent Valuation: Past, Present and Future. Prague Econ. Pap. 2010, 4, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Martin, M.; Fagerholm, N.; Bieling, C.; Gounaridis, D.; Kizos, T.; Printsmann, A.; Müller, M.; Lieskovský, J.; Plieninger, T. Participatory mapping of landscape values in a Pan-European perspective. Landsc. Ecol. 2017, 32, 2133–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, C.C. Environmental Psychology and Human Well-Being; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, A.; Coles, T.; Fish, R. Tourism in sub-global assessments of ecosystem services. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1529–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniehotta, F.F.; Presseau, J.; Araújo-Soares, V. Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, P. The Value of Ecosystem Services for Recreation. Ecosystem Services in New Zealand-Conditions and Trends; Manaaki Whenua Press: Lincoln, New Zealand, 2013; pp. 330–342. [Google Scholar]

- Schröter, M.; Van der Zanden, E.H.; Van Oudenhoven, A.P.E.; Remme, R.P.; Serna-Chavez, H.M.; de Groot, R.S.; Opdam, P. Ecosystem services as a contested concept—A synthesis of critique and counterarguments. Conserv. Lett. 2014, 7, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stålhammar, S.; Pedersen, E. Recreational cultural ecosystem services: How do people describe the value? Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowker, J.M.; English, D.B.K.; Donovan, J.A. Toward a Value for Guided Rafting on Southern Rivers. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 1996, 28, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrick, B.; Toher, D.; White, P. Test statistics for comparing two proportions with partially overlapping samples. J. Appl. Quant. Methods 2015, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.-H.; Bowker, J.; English, D.B.; Roberts, R.K.; Kim, T. Effects of travel cost and participation in recreational activities on national forest visits. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 40, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, B.K. The Concept of Landscape Health. J. Environ. Manag. 1994, 40, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäntymaa, E.; Ovaskainen, V.; Juutinen, A.; Tyrväinen, L. Integrating nature-based tourism and forestry in private lands under heterogeneous visitor preferences for forest attributes. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018, 61, 724–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. Mapping Landscape Values and Development Preferences: A Method for Tourism and Residential Development Planning. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2006, 8, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerholm, N.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Raymond, C.M.; Torralba, M.; Moreno, G.; Plieninger, T. Assessing linkages between ecosystem services, land-use and well-being in an agroforestry landscape using public participation GIS. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 74, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heung, V.C.S.; Qu, H. Hong Kong as a travel destination: An analysis of Japanese tourists’ satisfaction levels, and the likelihood of them recommending Hong Kong to others. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2000, 9, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Graefe, A.R.; Burns, R.C. Service quality, satisfaction, and behavioural intention among forest visitors. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 17, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.H.; Chen, T.Y.; Liu, C.R. The influence of tourism image on tourist’s behavioural intention on Taiwan’s coastal scenic area: Testing the mediating variable of tourists’ satisfaction. J. Outdoor Recreat. Study 2003, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.H. An ecotourism behavioural model of national forest recreation areas in Taiwan. Int. For. Rev. 2007, 9, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).