Abstract

Greenway is an important linear public space that meets the diverse needs of the public. With the increasing popularity of greenway construction, the study of different greenway usage behavior in different socio-economic areas is of great value to the detailed design and construction of greenway in the future. Using the theory of environment-behavior studies (EBS), this study selected representative urban greenways and suburban greenways in Beijing, China, and conducted a questionnaire survey. Descriptive statistics and the chi-squared test are used to quantitatively analyze and summarize the behavior of greenway users. It is found that user gender, educational level, and residence (i.e., permanent resident or visitor), as well as season of use, are highly similar for urban greenways and suburban greenways in Beijing. However, due to a close relationship with urban location, modified by temporal, spatial, and personal factors, different behavioral characteristics are evident as follows: (1) Urban greenways are most closely related to daily life, work and education of urban residents, with short travel distances, short single use time, high frequency of use, high social and cultural value, wide distribution of age groups and wide distribution of time periods of use. (2) Suburban greenways are an important choice for residents’ outdoor activities on weekends and holidays. It is mainly used for ecological protection and sightseeing, supplemented by sports and fitness functions. It has the characteristics of low use frequency, high income level, wide distribution of time and distance, mainly used by young and middle-aged people, and used for a single time of more than 1 hour. Natural scenery along the trail is the most important attraction factor, and waterfront space and walking space are the main use behavior characteristics.

1. Introduction

As global urbanization increases year by year, the proportion of urban populations has increased rapidly. More than 55% of the world’s population resides in urban areas, which will increase to 68% by 2050. However, approximately 40% of urban residents have no access to reasonably managed environments [1]. Some studies have pointed out that China’s urbanization level may reach 70% by 2035, and presently, its development rate is higher than the world’s average [2]. Rapid urbanization has brought about many urban problems, such as traffic congestion, environmental pollution, and the lack of green open space, which hinder the sustainable development of cities [3]. Green open spaces within cities are crucial to sustainable urbanization, thus stimulating research on Green Infrastructure (GI) [4,5]. More and more scholars are exploring its important role in addressing climate change, promoting a low-carbon economy, and improving public health [6,7]. Greenway is an essential element of Green Infrastructure (GI). Greenway is a linear, natural, and open urban green space (UGS). Embedded in a large ring network, it can establish a connection between urban habitat and related biodiversity [8,9]. At the same time, it also connects urban and rural areas [10], connecting various community spaces [11,12]. Like other urban assets such as parks, greenway is very beneficial for the improvement of the quality of public life [10,11,12,13].

Greenway can be placed into many different categories, and presently there are three principal ways of classifying greenway. The first classification method divides greenways according to their scale and function. For example, Little (1990) divides greenways into urban riverside greenway; recreational greenways, featuring paths and trails; ecologically significant corridors; scenic and historic routes; and comprehensive greenway systems or networks [14]. The second classification method divides greenways into different grades according to regional scales. For example, Ahern (1995) divides greenways into four types: urban greenway, municipal greenway, provincial greenway, and regional greenway [15]. The third classification method classifies greenway according to its location. For example, Jing et al. (2012) divided greenways into urban greenways, suburban greenways, and rural greenways [16].

With the dynamic development of cities, urban–rural integration is regarded as a beneficial urban–rural relationship [17]. The transition zone between urban and rural areas can be defined as a separate spatial unit referred to as a “suburb” [18,19]. This study focuses on urban and municipal greenways and divides greenways into two categories according to their locations: “urban greenway” and “suburban greenway”. Urban greenways mainly refer to greenways distributed in urban areas, which have important values in ecology, environment, society, education, etc. [5]. For example, it can improve the ecological environment in the central area of a city and provide outdoor activities for urban residents to improve the quality of life [20,21,22]. Suburban greenways refer to the greenway mainly located in suburban areas, with the main purpose of strengthening the ecological connection between urban and rural areas and meeting the leisure needs of urban residents in the countryside.

Research into greenway usage behavior is mainly divided into two kinds. The first considers the use behavior related to a single type of greenway. For example, Gordon (2004) studied the use of a community greenway [23], Keith et al. took two community greenways as subjects to compare the behavioral characteristics and preferences of greenway users [24], while Akpinar (2016) and Zhao (2021) studied the use of an urban greenway [5,25].The second focuses on the use of greenways in different built environments. For example, Gobster (1995) used 13 greenways in the Chicago area to study how different built-up environmental factors affect people’s use patterns and preferences [26]. Liu et al. (2020) studied the heterogeneity of traffic greenways, forest greenways, park greenways and rural greenways from the aspects of land use, traffic impact, and corridor width [27]. However, there is a lack of research on the differences in usage behavior due to differences in location, specifically for urban and suburban greenways.

Different usage behaviors can reflect the different needs of users. If the construction of a greenway does not meet the needs of users, then the use of the greenway may be reduced [28]. With the continuous promotion of greenway construction, in order to enhance the vitality of greenway use, quality and differentiated planning and design will become an important development direction in the future [29,30]. Hence, research on the behavioral characteristics of different greenway users has important significance for the detailed construction of greenway in the future.

The theory of environmental behavior developed rapidly on the basis of the rapid development of society and economy, and society and academia began to think about how to improve people’s quality of life. The theory takes the human-centered scale as the starting point, focuses on understanding the behavior and motivation of users, and comprehensively reveals the relationship between people and the environment from a multidisciplinary perspective. It has a wide range of applications in urban planning [31,32,33]. The objects involved in this theoretical research range from the large-scale planning level to the small-scale spatial level, among which the related research on green spaces includes many types of urban residential streets, urban villages, commercial blocks, and parks [34,35,36,37,38,39]. Thus, a variety of logical models of space user activity relationships are generated, For example, Golledge (1997) and others proposed the classic “cognition preference behavior” interaction theory and research paradigm [40], and Chai Yanwei and others proposed the “research framework of urban activity space based on mobile activity behavior” [41]. The relationship between space and its users is logically combined through the model, but there is no model of the relationship between greenway and its users at present.

This study hypothesizes that the usage behaviors of urban greenway and suburban greenway are different, which contain use crowd attributes, spatiotemporal behaviors, personal behaviors, and other aspects. Meanwhile, different usage behaviors can reflect different needs of users. This study establishes a greenway space-usage behavior relationship model based on the theory of EBS, and optimizes questionnaire survey indicators using available literature, so as to provide a logical and targeted data basis. Through the comparative study of the use behavior characteristics of urban greenways and suburban greenways, it aims to provide a theoretical basis for the construction of humane and dynamic greenways in China.

2. Methods and Data Collection

2.1. Study Area

The greenways used in this study were located in Beijing, the capital of China. Beijing was chosen as it has a multicultural population [42]. Beijing started the construction of greenway projects in 2013 [43]. By 2021, the government had built three relatively complete greenway groups, namely the Second Ring Road Greenways, Three Hills and Five Gardens Greenways, and the Wenyu River Greenways, covering a total length of 500 km. According to the requirements of the Beijing Master Plan (2016–2035) and the Beijing Municipal greenway planning system, 740 km of greenways are still to be planned. Therefore, it is urgent to study the differences in the use behavior characteristics of the different types of greenways already constructed, and to clarify the activity needs for different types of greenways, so as to provide some guidance for future planning and design.

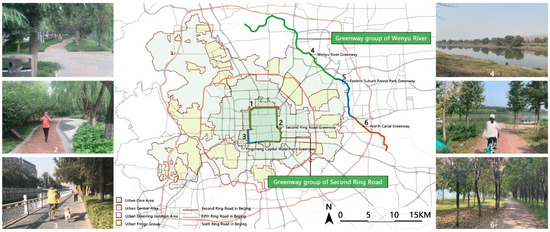

The urban “Second Ring Road Greenway” and the suburban “Wenyu River Greenway” were selected for this study (Figure 1). The greenway group around the second ring road is mainly composed of two greenways: an urban greenway around the second ring road and the Ying-Cheng waterfront greenway. The second Ring Road Greenway lies along the ring road around Beijing, built around the Beijing moat, and connects urban public green space, municipal road green space, river green space and historical sites, and plays a core role in the green space system of Beijing. The Wenyu River greenway cluster consists of the Wenyu River greenway, the Eastern Suburb Forest Park greenway, and the North Canal greenway. The cluster is located in the urban suburbs of the fifth and sixth ring roads around Beijing. It is arranged along the natural course of the Wenyu River. It is an important green barrier in Beijing and an important ecological belt connecting the green space on the outer edge of the city.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the location of the study object.

The Second Ring Road Greenway Group and the Wenyu River Greenway Group are good representatives of Beijing’s urban greenway construction and are important pilot greenway projects in Beijing. They are also a good model of ecological priority development in contemporary big cities. Both greenways were completed in 2015, after 7 years of construction.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Construction of Greenway Space-Behavior Relationship Model

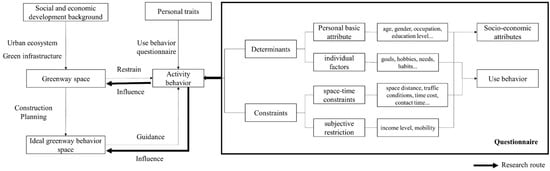

This study draws on the theory of EBS to construct a greenway space-usage behavior relationship model, which is used as the main basis for the selection of questionnaire indicators, so that the study of the behavior characteristics of greenway use is comprehensive and logical.

As shown in Figure 2, a greenway space-user behavior relationship model was established, which was suitable for this study. This study uses the “Spatial Cognition–Spatial Preference–Spatial Behavior” method commonly used in EBS in urban spatial research, as well as the “Travel Activity-Based Research Frame of Urban Spatial Structure” method proposed by Yan-wei et al. (2006) (Figure 2) [32,41]. We integrate and condense the two methods into a greenway space-usage behavior relationship model suitable for this study. The main line of the model is to integrate temporal and spatial constraints on the basis of subjective cognition. Studies have shown that individual factors such as subject motivation and living habits and basic attributes of individuals play a decisive role in the choice of activity behavior [32], and are also affected and restricted by factors such as time, space, and subject ability [35,37,38]. Hence, the aggregation of behaviors needs to consider the influences of different spatial scales, temporal scales, and group types [44].The model not only explains the interaction process between usage behavior and greenway space, but also provides direction for the data collection. The ultimate goal of the model is to maximize the harmony between individual behavior and the overall space of the greenway.

Figure 2.

Relationship model of greenway space-user behavior based on the theory of space-behavior.

2.2.2. Questionnaire Design

In order to obtain detailed information and data on user behavior, this paper used a questionnaire survey. The questionnaire survey is a data collection method that is frequently used in planning and design (e.g., Akpinar, 2016; Han, 2021; Qin, 2013; Wan-Yu Liu, 2018) to collect preliminary data [5,45,46,47].

The backbone of a questionnaire usually consists of two parts: background questions and thematic questions [48]. Therefore, in the design of the questionnaire in this study, user’s socio-economic attributes and user behavior was included first, and then user’s socio-economic attributes. This should include the basic social attributes of the subject and the constraints faced by the subject. The behavioral part of the questionnaire included thematic problems of individual factors and temporal and spatial constraints.

With reference to published papers on the use behavior of greenways with high citations in core journals in the past 5 years (Table 1 and Table 2), the questionnaire was formed and was found to provide a relatively stable and complete index system. On the basis of greenway space-usage behavior relationship model, combined with the relatively stable and complete index system in the literatures, the questionnaire index suitable for this study could be formed.

Table 1.

Reference indicators of socio-economic attributes.

Table 2.

Using behavioral reference metrics.

Based on the literature analysis and field research, and through the greenway space-usage behavior relationship model, survey indicators were optimized. The final questionnaire included two parts: The first part explored the socio-economic attributes of the user and contained two parts: (1) the basic social attributes and constraints of the subject, including specific characteristics such as gender, age, education level, occupation, income and inhabitancy (i.e., permanent or visitor); (2) use behavior, including the frequency of use, transport methods, time spent on the road, usage period, duration of use, date of use, month of use, accompanying people, purpose of use and activities, information pathways, reason for selection, and type preference of space.

Using the greenway space-usage behavior relationship model for guidance, a non-quantitative questionnaire was designed. After a content validity test was performed, all analyses were carried out using SPSS (25.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) software to conduct descriptive statistical analyses and chi-square tests, which quantitatively analyzed and evaluated the attributes and behavior characteristics of the users. The Z-test and Bonferroni method were used for comparison between groups.

2.3. Data Collection

Beijing has a warm temperate semi-humid semi-arid monsoon climate, with a rich plant landscape from September to November, and this is the peak period for outdoor activities [59,60]. Hence, this study chose to conduct the survey from 18 October 2021 to 24 October 2021. We collected data along both greenway groups using intercept surveys of greenway users at key access points. The access points were identified by investigators based on good scenery and main entrance. The same interception survey method is also used in other similar studies [11]. Since the width and length of the two sets of greenways are different, we chose different interview locations to attract respondents. Each visit lasted 2–3 h, and the survey time consisted of 5 working days and 2 rest days. Interviews were randomly carried out within the time slots 07:30–10:00, 11:30–14:00, 15:30–18:00, and 19:30–21:00. Face-to-face interviews were conducted by the investigators to explain questions that might arise during completion of a questionnaire. Each questionnaire was filled out and analyzed on site to better ensure that the participants’ answers reflected their real use of the greenway.

The investigators were graduate students with professional academic backgrounds and field investigation experience, and they received systematic training in research methods and data collection before conducting the surveys. We made every effort to survey a wide range of respondents to understand different demographics and socioeconomic groups. The questionnaire took about 8 min to complete. A total of 232 questionnaires were collected, and after excluding the questionnaires with missing data from key analytical variables and other invalid questionnaires, 220 valid questionnaires remained: 115 from the Second Ring Road Greenway and 105 from the Wenyu River Greenway.

3. Results

3.1. Basic Sample Characteristics

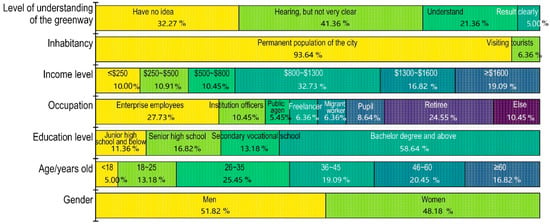

The gender composition of the samples was basically balanced (Figure 3). The gender and age of the 232 respondents represent the population of Beijing. In terms of monthly income level, the majority earned USD 800–1300/month, compared with the average income of USD 925 per month in Beijing. The key sociodemographic data of our respondents were largely consistent with government statistics. Therefore, the population sample of this study is representative of the population in Beijing to a certain extent. This also shows that the greenway is an important spatial carrier for the use and interaction of various social groups. In the course of the questionnaire interview, it was found that the public’s understanding of the concept of the greenway was generally low.

Figure 3.

Demographic characteristics of the sample.

3.2. Differences in the Socio-Economic Attributes of Consumers

Table 3 presents the results of an analysis of the socio-economic attributes of respondents. After applying the chi-square test, it was found that there were no statistically significant differences in gender, education level, and inhabitancy (i.e., permanent or visitor) among users of the different types of greenways, but there were significant differences in age, occupation, and income level.

Table 3.

Chi-square test of pairwise comparison of socioeconomic attributes.

(1) The proportion of male and female users of urban greenways and suburban greenways was basically balanced. (2) In terms of education level, the proportion of users with “bachelor’s degree and above” of the two types of greenways was high and there was no difference. (3) The users of urban greenways and suburban greenways were mainly permanent residents of the city, accounting for more than 90%. (4) In terms of the composition of user income, urban greenways and suburban greenways had some differences. Overall, the income distribution of urban greenway users was relatively scattered, while the user income of suburban greenways is concentrated in USD 800–1300, accounting for 41.0%. (5) In terms of the age composition of users, urban greenways users were of more widely distributed ages, while the users of suburban greenways were mainly young and middle-aged as the proportion of people aged 25–60 accounted for 86.6% of the number of respondents. (6) In terms of occupational composition, the difference between urban greenways and suburban greenways was mainly reflected in the “retiree” option. Users of urban greenways were mainly retirees, accounting for 34.8%, which was much higher than that of suburban greenways. Users of suburban greenways were mainly enterprise employees, with a proportion of 28.3%.

3.3. Differences in Usage Behaviors

Table 4 presents the results of the analysis of the spatio-temporal characteristics of greenway use, and Table 5 presents an analysis of the personal behavior characteristics of greenway users. There were no significant differences between users of urban greenways and suburban greenways in terms of “month of use” and “companions”, but there were significant differences in the other 10 aspects.

Table 4.

Chi-square test for spatio-temporal behaviors.

Table 5.

Chi-square test for personal behaviors.

3.3.1. Differences in Spatiotemporal Behaviors

Users had different behavioral characteristics due to the temporal and spatial constraints caused by different locations of greenways (Table 4), i.e.,

- (1)

- In terms of months of use, there was no significant difference between urban greenways and suburban greenways; most people’s outdoor activities were not affected by the season, and the proportion of greenways used in all four seasons was relatively high.

- (2)

- In terms of frequency of use, the frequency of use of urban greenways was significantly higher than that of suburban greenways, and the proportions of “four times a week or more” and “one to three times a week” accounted for 35.7% and 25.2%, respectively. The frequency of use of suburban greenways was relatively low, mainly “one to three times a month” and “seldom”, accounting for 38.1% and 32.4%, respectively.

- (3)

- In terms of time spent on the road, the time spent by users of urban greenways was concentrated around 20 min (68.7%). The distribution of travel time spent by users of suburban greenways was relatively scattered. The number of people who spend 20 to 30 min was the largest, accounting for 30.5%.

- (4)

- In terms of the duration of use, the distribution of the use time of urban greenways was relatively scattered, of which the number of people with a use time of 30 min to 1 h was the largest, accounting for 33.9%. The use time of the suburban greenway was generally more than 1 h (75.2%), followed by the proportion of people with a use time of 30 min to 1 h.

- (5)

- In terms of the date of use, the number of users of urban greenways who carry out outdoor activities on weekdays or weekends was larger, accounting for 36.8% and 52.2%, respectively, while the users of suburban greenways were more likely to choose weekends and holidays to travel, and there were very few people traveling on weekdays, accounting for only 9.9% of the total number of people interviewed on this greenway.

- (6)

- In terms of the usage period, the use of urban greenway users was mainly between 6:00 and 18:00, of which the time slot between 14:00 and 18:00 accounted for 32.9% of the use time. The use time of the users of the suburban greenway was mainly concentrated between 9:00 and 18:00. Compared with the urban greenway, the use time of the suburban greenway was shorter, with the peak period of morning use being later, and the end time of the afternoon use being earlier. The number of people using both types of greenways after 18:00 was small.

- (7)

- In terms of transport method, urban greenway users mainly walked (50.4%), followed by people using public transportation (24.8%). Users of suburban greenways were more likely to travel by car, accounting for 51.3%.

3.3.2. Differences in Personal Behaviors

Greenway users also had different usage behaviors due to personal factors (Table 5), i.e.,

- (1)

- In terms of recreational companions, most of the users of the two types of greenways had chosen the two options of “alone” and “relatives and friends”, of which the number of people who chose to travel with relatives and friends exceeded 50% of the total number of respondents, and only a very small number of people came to visit the greenways in the “group organization” category.

- (2)

- Users of urban and suburban greenways liked the “quiet surroundings” and “natural scenery” of greenways. The proportion of urban greenway users choosing “cultural landscape” reached 14.8%, which was significantly higher than the 2.9% of suburban greenway users.

- (3)

- In terms of spatial types of greenways, greenway spaces were divided into four types: “square space”, “waterfront space”, “walking space”, and “facilities with space” (i.e., space containing infrastructure such as seats and fitness equipment)[61,62]. For these types, the choice distribution of urban greenway users was varied, while suburban greenway users preferred “waterfront space” and “walking space”, accounting for 40.0% and 43.8%, respectively.

- (4)

- In terms of the purpose of use, there were significant differences between urban greenways and suburban greenways. As shown in Table 6, after on-site research, 12 main forms of user activities were identified, and these activities were divided into five categories: “sightseeing”, “exercise and fitness”, “leisure and entertainment”, “commuting”, and “internship/research survey”. Both types of greenways carried important sports and fitness functions. However, differences were found in the two aspects of “sightseeing” and “commuting”. Users of urban greenways did not use sightseeing as a main purpose of use, but most of them used sports and fitness, accounting for 41.8%. Their sports forms were mainly walking and running. Commuting functions were also important, accounting for 7.3%. However, most of the users of suburban greenways stated “sightseeing” and “exercise and fitness” as the main purpose of their use, accounting for 38.3% and 35.3% of users, respectively. Commuting along suburban greenways was weak, accounting for only 0.7%.

Table 6. Purpose of use and activities.

Table 6. Purpose of use and activities.

- (5)

- In terms of information channels for obtaining information about greenways, most of the users of urban greenways had learned about them as they lived nearby, accounting for 62.2%. Most people learnt about suburban greenways mainly because they were publicized by others, accounting for 48.6%.

3.4. Summary

Detailed results (Table 7) are as follows: (1) Urban greenways are most closely related to daily life, work, and learning of urban residents, with short travel distances, short single use time, high frequency of use, high social and cultural value, wide distribution of age groups, and wide distribution of time periods of use. (2) The suburban greenway is an important choice for outdoor activities on weekends and holidays. It is mainly used for ecological protection and sightseeing, supplemented by exercise and fitness functions. It has the characteristics of low use frequency, high income level, wide distribution of time and distance, mainly used for young and middle-aged people, and used for a single time of more than 1 hour for a long time. Natural sceneries are the most important attraction factor, and waterfront space and walking space are the main use behavior characteristics of the main activity space.

Table 7.

Summary of the use characteristics of the two types of greenways.

4. Discussion

The present study uses two greenways in Beijing as a test case to study the usage behavior characteristics of different regional types of greenways. The results showed that the usage behavior of urban greenways and suburban greenways were different. The study summarizes and compares the characteristics of the use behavior of urban greenways and suburban greenways from three aspects: the attributes of the users, behaviors related to time and space, and behaviors affected by individual factors. Thus, our research hypothesis is further confirmed.

Urban greenway use is most closely related to the daily life, work, and study of city residents. According to existing studies [46,63], population density, mixed land use types, and accessibility around greenways can affect the intensity of greenway use. As urban greenway has a high density population and a high mix of land use types close by, and accessibility is generally better [64], the frequency of use of urban greenway is very high both during the working week and at weekends, and the user population comes mainly from residents who live nearby. Most users can reach urban greenway within 20 min by walking and public transportation, and urban greenway provides one of the most important outdoor activity spaces for retirees during weekdays. This finding is consistent with other literature on urban greenways [11,65]. Since most urban greenways are located in central urban areas, they can play their socio-cultural functions at the same time as satisfying the ecological functions of greenways [7]. Related research shows that people’s frequent use of urban greenways is also related to the social and cultural functions provided by greenways [66].

The suburban greenway is mainly based on ecological protection and appreciation and excursion functions, supplemented by sports activities [67]. Most of the suburban greenways are built using natural landscapes such as mountains, forests, lakes, and fields; the frequency of use is low and relatively fixed. This is consistent with the low user density and frequency of suburban trails pointed out in the study of Keith et al. [11]. The use of greenways is affected by the surrounding environment [3,68]. Thus, the low use frequency of suburban greenways may be related to lower population density and land type richness around suburban greenways. The suburban greenway mainly relies on the “natural scenery” to attract people. This is likely due to the fact that the greenway is built in a riparian area with lush natural vegetation, thus providing an opportunity to connect with nature.

The results of this study show that the majority of users of greenways are residents of the city [69,70].Users of suburban greenways have higher income levels and are younger than users of urban greenways. These findings may help us identify the factors that influence individuals in their use of greenways [3]. For instance, the elderly may be constrained by mobility, unable to reach greenways that are at some distance away and face economic constraints such as transportation costs.

Different types of greenway users have high similarities in terms of months of use and accompanying companions. Most people’s recreational activities are not affected by the seasons, although some prefer to travel in autumn, which is consistent with the city’s climatic characteristics. In terms of travel companions, most of the users of the two kinds of greenways choose to carry out greenway activities alone or with family and friends, which is in line with the psychological “solitude” and “companion effect”. Solitude can help people’s self-recovery and rebuild their feelings [71], and companion behavior has a positive impact on mental health, emotional regulation, and the establishment of good interpersonal relationships [72]. Hence, greenway as an open green space provides an important place for people’s physical and mental health development [73,74].

One unanticipated finding was that in the era of highly developed media, the number of individuals who learned about the greenway through media publicity was very small, although the overall cultural level of greenway users was high. However, the understanding of the greenway was generally low, and many individuals had never heard of the concept of “greenway”. We call on more citizens to participate in the use of greenways and provide suggestions for the continuous improvement of these greenways, which will help greenways truly reflect users’ needs and preferences, so as to maximize the multi-faceted benefits of greenways.

5. Conclusions

Based on the theory of environment-behavior studies, this study designed a greenway space-usage behavior relationship model as a research guide and used methods such as questionnaire interviews and chi-square tests to study the behavior characteristics of people on urban and suburban greenways. It was found that for the two types of greenways in the same city, the gender, education level, inhabitancy, and month of use have a high degree of similarity, but due to the relationship with the location of the city, they are constrained by temporal and spatial factors and the influence of personal factors, which all produce different behavioral characteristics.

Greenway is an important infrastructure and understanding the usage behavior of populations in greenway is of great importance for planning, design, and management. According to the results of this study, city planners and managers should consider the local residents’ needs and expectations for greenway. In order to meet the needs of interaction between man and nature, they should reasonably draw up the location of the green-way and the landscape elements in the greenway, and pay attention to the sports and fit-ness function of the greenway groups. The connectivity between the greenway groups is also of concern to urban planners. A good greenway network is very important to improve the quality of life in a city.

The present study has several limitations. One limitation of this study is that it ignores differences within a single type of greenway, and in future studies, the differences within a single greenway should also be considered. The second limitation of this study is the small sample size and limited geographical environment. Although we have selected two types of greenway groups and they are representatives of Beijing greenway groups, the results of this study may not be applicable to Western countries and regions, nor to small and medium-sized cities in China. Follow-up research could expand the geographical scope of the research and consider greenways in different climates or within regions of different economic levels. The third limitation is that our sampling approach did not cover the trail during all possible periods of use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L. and X.G.; methodology, L.L.; software, X.G. and L.Y.; validation, L.L., X.G. and J.L.; formal analysis, X.G. and L.Y.; investigation, X.G., J.L. and L.M.; data curation, X.G. and L.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, X.G. and J.L.; writing—review and editing, L.L. and Z.W.; visualization, L.M.; supervision, L.M.; funding acquisition, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 32071833, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China, grant number 2021BLRD25.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 32071833, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China, grant number 2021BLRD25. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO. Urban health. Available online: https://www.who.int/zh/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/urban-health (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Li, G.; Sun, Y. An Analysis of China’s Urbanization and Its Regional Differences towards 2023. Reg. Econ. Rev. 2020, 04, 72–81. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gu, W.; Tao, L.; Lei, Y.; Zeng, M. Increasing the Use of Urban Greenways in Developing Countries: A Case Study on Wutong Greenway in Shenzhen, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obaa, B.; Aei, A.; Tem, C.; Ooo, A. Urban green infrastructure in Nigeria: A review. Sci. Afr. 2021, 14, e01044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, A. Factors influencing the use of urban greenways: A case study of Aydin, Turkey. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 16, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Guo, F.; Lin, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, P. Optimization of green infrastructure networks based on potential green roof integration in a high-density urban area—A case study of Beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 834, 155307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, Y. Evaluation of the Health Promotion Capabilities of Greenway Trails: A Case Study in Hangzhou, China. Land 2022, 11, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, J. Urban landscape sustainability and resilience: The promise and challenges of integrating ecology with urban planning and design. Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 28, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, M.M. Urban landscape conservation and the role of ecological greenways at local and metropolitan scales. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 76, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.Y.; Ye, Y.; Jiang, Z.D.; Fu, C.W.; Huang, R.; Yao, D. A data-informed analytical approach to human-scale greenway planning: Integrating multi-sourced urban data with machine learning algorithms. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, S.J.; Larson, L.R.; Shafer, C.S.; Hallo, J.C.; Fernandez, M. Greenway use and preferences in diverse urban communities: Implications for trail design and management. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 172, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark Benedict, E.M. The Conservation Fund, Bergen, Lydia. In Green Infrastructure: Linking Landscapes and Communities. Bibliovault OAI Repository; Island Press: St. Louis, CA, USA, 2006; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, F.; Kowarik, I.; Säumel, I. A walk on the wild side: Perceptions of roadside vegetation beyond trees. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, C.E. Greenways for America; The John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA; London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, J. Greenways as a planning strategy. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 131–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, C.; Rui, Y. Research on the Construction Standard of Greenway Slow System Based on Classification System. Guangdong Landsc. Archit. 2012, 34, 15–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Research on the urban-rural integration and rural revitalization in the new era in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2018, 73, 637–650. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yt, A.; Jing, Q.B.; Lei, W.A. Village classification in metropolitan suburbs from the perspective of urban-rural integration and improvement strategies: A case study of Wuhan, central China. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y. Mapping Suburbs Based on Spatial Interactions and Effect Analysis on Ecological Landscape Change: A Case Study of Jiangsu Province from 1998 to 2018, Eastern China. Land 2020, 9, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, L.d.C.; Riedel, P.S. Multi-criteria spatial decision analysis for demarcation of greenway: A case study of the city of Rio Claro, São Paulo, Brazil. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 84, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.-J.; Tsou, C.-W.; Li, Y.-S. Urban-greenway factors’ influence on older adults’ psychological well-being: A case study of Taichung, Taiwan. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Jin, L.; Wang, L.; Huang, C. Measuring patterns and mechanism of greenway use—A case from Guangzhou, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 34, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, P.M.; Zizzi, S.J.; Pauline, J. Use of a community trail among new and habitual exercisers: A preliminary assessment. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2004, 1, A11. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, S.J.; Boley, B.B. Importance-performance analysis of local resident greenway users: Findings from Three Atlanta BeltLine Neighborhoods. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 44, 126426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Gan, H.; Qian, X.; Leng, J.; Wu, P. Riverside Greenway in Urban Environment: Residents’ Perception and Use of Greenways along the Huangpu River in Shanghai, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P.H. Perception and use of a metropolitan greenway system for recreation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Meulder, B.D.; Wang, S. Heterogeneous landscapes of urban greenways in Shenzhen: Traffic impact, corridor width and land use. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 55, 126785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Päcke, S.R.; Figueroa Aldunce, I.M. Distribución, superficie y accesibilidad de las áreas verdes en Santiago de Chile. EURE (Santiago)-Rev. Latinoam. De Estud. Urbano Reg. 2010, 36, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Lv, M. Detailed Planning Management From Urban Design Viewpoin. Planners 2017, 33, 24–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, N.; Espie, P.; Hankin, R. Rational landscape decision-making: The use of meso-scale climatic analysis to promote sustainable land management. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 67, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Qiu, X.; Xu, J.; Hou, Y. Review of Research Methods for Green Spatial Behavioral Activities and Environmental Cognition. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 27, 56–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Song, W.; Li, X. Coupling and Mutual Feedback of Urban Spatial Cognition-Preference-Behavior—Based on the Follow-up Survey of Graduate Students from the University of ChineseAcademy of Sciences. Trop. Geogr. 2021, 41, 1023–1033. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y. Spatial Behavior and Behavioral Space, 1st ed.; Nanjing Southeast University Press: Nanjing, China, 2014; p. 303. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Blennerhassett, J.M.; Borschmann, K.N.; Lipson-Smith, R.A.; Bernhardt, J. Behavioral Mapping of Patient Activity to Explore the Built Environment During Rehabilitation. Herd 2018, 1937586718758444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, K.R.; Jones, S.A.; Holliday, K.M.; Cohen, D.A.; McKenzie, T.L. Park characteristics, use, and physical activity: A review of studies using SOPARC (System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities). Prev. Med. 2016, 86, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wu, C. An Observational Study of Park Attributes and Physical Activity in Neighborhood Parks of Shanghai, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chai, Y. Residents’ activity-travel behavior variation by communities in Beijing, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 23, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chai, Y.; Li, F. Built environment diversities and activity–travel behaviour variations in Beijing, China. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 1173–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Chai, Y.; Kwan, M.P. Space–time fixity and flexibility of daily activities and the built environment: A case study of different types of communities in Beijing suburbs. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 2214–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golledge, R.G. Spatial Behavior: A Geographic Perspective; The Guilford Press: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Y.; Shen, J. Travel-Activity based research frame of urban spatial structure. Hum. Geogr. 2006, 5, 108–112+154. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, L. Study on the Management of Foreigners in Beijing under the Background of Building World City. J. People’s Public Secur. Univ. China 2014, 4, 7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L.; Zhao, X.; Li, L. Evaluation of Typical Built Greenways in Beijing Based on Multi-Source Big Data Analysis. Mod. Urban Res. 2019, 10, 36–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Downs, R.M. The Future of Behavioral and Cognitive Geography:A Coda; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 389–406. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.; Li, D.Y.; Chang, P.J. The effect of place attachment and greenway attributes on well-being among older adults in Taiwan. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.Y.; Chuang, C. Preferences of Tourists for the Service Quality of Taichung Calligraphy Greenway in Taiwan. Forests 2018, 9, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Zhou, X.; Sun, C.; Leng, H.; Lian, Z. Influence of green spaces on environmental satisfaction and physiological status of urban residents. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.; Zhang, J. The Survey Methods in Planning and Design 1—Questionnaire Survey (Theory Part). Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2008, 10, 82–87. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, F.; Yin, H.; Kong, F. The Using Characteristics and Satisfaction of Urban Greenway—A Case Study of the Purple Mountain Greenway in Nanjing. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2015, 31, 50–54. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Niu, Z.; Hu, N.; Yu, Y. Greenway Satisfication Investigation Based on the Importance-PerformanceAnalysis Method. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2016, 25, 815–820. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xuan, G.; Zhu, Y. Motivation and Behavioral Characteristics of the Park-based Recreation for Urban Residents in Transitional Period: A Case Study of Xuanwu Lake Park in Nanjing. Areal Res. Dev. 2016, 35, 113–118+133. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Z.; Jinhong, G.; Yanli, L. Research on the Recreational Greenway User’s Behavior and Experience Satisfaction in Rural Areas. Areal Res. Dev. 2016, 35, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, B.; Yang, J. Post Occupancy Evaluation (POE) on the Rural Greenway System: A Case Study of Jinjiang 198 LOHAS Greenway in Chengdu Province. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2018, 34, 116–121. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Zhu, N.; Wang, D.; Cheng, H.; Fan, X.; Huang, P.; Lan, S.; Li, X. Research on Urban Greenways Optimization Strategy Based on the Tourist Recreational Motivation and Behavior Characteristics——A Case in Fu Forest Trail of Fuzhou City. J. Shandong Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 49, 639–645. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zou, D. Influences of greenway on the physical activities of users with different proximity degrees: A study on waterfront greenway in guangzhou city. City Plan. Rev. 2019, 43, 75–80. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Can, X.; Huichao, T.; Bin, X.; Quan, H. Using characteristics and satisfaction of country greenway. J. Zhejiang AF Univ. 2019, 36, 154–161. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Chen, L.; Yang, C. The Impact of the Greenway Environment on the Intensity of Residents’ Use from the Perspective of Health. South Archit. 2021, 03, 15–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, U.; Lee, J.; He, S.Y. Pedestrianization Impacts on Air Quality Perceptions and Environment Satisfaction: The Case of Regenerated Streets in Downtown Seoul. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, X.; Hao, P.; Li, G.; Li, H.; Dong, L. Seasonal dynamic of plant phenophases in Beijing—A case study in Beijing Botanical Garden. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2018, 42, 906–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Wang, Z.; Miao, S.; Xuan, C.; Su, C.; Cheng, C. Research on Urban Design Optimization Strategy based on Microclimate Environment Improvement: Take Wanpingcheng in Beijing as an Example. Urban Dev. Stud. 2022, 29, 34–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, J. How to study public life. Planning Perspectives 2014, 29, 584–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Xue, Z. The Research of Staying Space of Urban Living Street for the Aged—Take Zhengzhou as an Example. Chin. Overseas Archit. 2018, 3, 91–93. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.; Lu, J. Explore the Relevance between Greenway Accessibility and Users’ Activity Level:A Case Study of “TCB” Greenway Trail at Baltimore, USA. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2013, 29, 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Lee, H.S.; Jeong, D.; Shafer, C.S.; Chon, J. The Relationship between User Perception and Preference of Greenway Trail Characteristics in Urban Areas. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.A.; Hooker, S.P.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Hutto, B. User demographics and physical activity behaviors on a newly constructed urban rail/trail conversion. J. Phys. Act. Health 2011, 8 4, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xu, H.; Fu, F.; Miao, M. What Is the Effect of Cultural Greenway Projects in High-Density Urban Municipalities? Assessing the Public Living Desire near the Cultural Greenway in Central Beijing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.H.; Moorman, C.E.; Hess, G.R.; Sinclair, K. Designing suburban greenways to provide habitat for forest-breeding birds. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 80, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Siu, K.W.M.; Gong, X.Y.; Gao, Y.; Lu, D. Where do networks really work? The effects of the Shenzhen greenway network on supporting physical activities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 152, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, G. Sustainability and Urban Greenways: Indicators in Indianapolis. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2003, 69, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff-Hughes, D.L.; Fitzhugh, E.C.; Bassett, D.R.; Cherry, C.R. Greenway siting and design: Relationships with physical activity behaviors and user characteristics. J. Phys. Act. Health 2014, 11, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, L.; Cheng, J.; Swanson, S. The companion effect on adventure tourists’ satisfaction and subjective well-being: The moderating role of gender. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 897–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.; Zuzanek, J.; Mannell, R. Being Alone Versus Being with People: Disengagement in the Daily Experience of Older Adults. J. Gerontol. 1985, 40, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszczak, A.; Vaznoniene, G.; Vaznonis, B. Green infrastructure spaces as an instrument promoting youth integration and participation in local community. Manag. Theory Stud. Rural. Bus. Infrastruct. Dev. 2018, 40, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Lu, Y.; Zheng, Y. Casual evaluation of the effects of a large-scale greenway intervention on physical and mental health: A natural experimental study in China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 67, 127419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).