Abstract

Rural entrepreneurship is an important way to promote rural revitalization, narrow the gap between urban and rural areas and increase farmers’ income. With the acceleration of urbanization, land resources have become scarcer than capital, technology, and human resources in China. At the same time, food-security pressure makes the stock of rural construction land in China extremely tight. Therefore, how to meet the demand for rural entrepreneurial land without touching the red line of cultivated land or occupying the existing rural construction land available is an urgent problem that needs to be solved. Reviewing the relevant literature, it was found that some regions in China innovated the way of “capital compensation and land equity” to obtain the use rights of marginal land resources such as idle farmhouses, workshops and school buildings and transformed them into entrepreneurial development spaces, which alleviated the scarcity of entrepreneurial construction land. At the same time, it also promoted the local residents’ employment and economic development. We believe that according to the social and economic conditions of different regions, the in-depth tapping of rural marginalized land is an effective way to solve the lack of development space for rural entrepreneurship and should be implemented worldwide.

1. Introduction

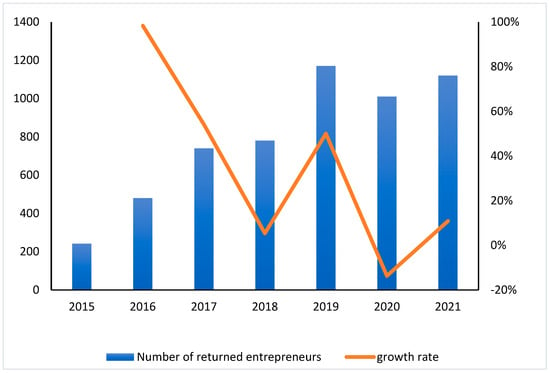

Rural entrepreneurship is the main force that promotes rural economic development, as well as an effective way to break the imbalance between urban and rural development and a major measure to promote the employment of surplus labour. Rural entrepreneurship can help farmers to overcome poverty and achieve the goal of revitalizing the countryside [1,2,3,4]. With the deepening of “mass entrepreneurship and innovation” and the further improvement of relevant policies, the number of all kinds of entrepreneurial activities has increased. Figure 1 shows the overall change in the number of returning entrepreneurs in China from 2015 to 2021. Although affected by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the number of home-returning entrepreneurial activities declined, but the overall trend was still rising, indicating that home-returning entrepreneurial activities had become an important development model in that period. The essence of returning home entrepreneurship is the process of population migration from urban to rural, which can be explained by Bogue’s push-pull theory [5]. Specifically, on the one hand, it stems from the “thrust” of the city, namely the repulsion. First of all, the pace of urban development is getting faster and faster, followed by the elimination of a large number of backward production capacity, which leads to the reduction of a large number of low-tech jobs, and laid-off workers can only find another way. Secondly, the city life rhythm is fast, all walks of life competition pressure, low quality of life, personal value is not very high. Finally, for modern young people, everyone wants to break out of their own business. Urban entrepreneurship has strict requirements for technology, funds and places. The cost of entrepreneurship is very high, and it is difficult for ordinary people to achieve. Returning home to start a business becomes a good choice. On the other hand, the “pull” of rural areas is attractive. First of all, the national policy formulation is constantly tilted to rural areas, such as the preferential policy for returning entrepreneurs in land use and electricity, and the support for rural entrepreneurs in funds. Secondly, the rural entrepreneurship market has just begun, the market development is insufficient, there are many gaps, and the entrepreneurial competition pressure is small, which provides a broader development space and prospect for rural entrepreneurs. Finally, most of China’s rural areas have achieved water conservancy, power grid, road hardening, network communications and other infrastructure construction, in line with the basic conditions for the development of production requirements. Many reasons prompted the current number of rural entrepreneurs to increase year by year.

Figure 1.

Changes in the number and growth rate of returning entrepreneurs between 2015 and 2021. (Data from 2015 came from the National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Data from 2016 were obtained from the Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China, while 2017 and 2018 data were obtained from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Data from 2019 and 2020 were derived from the Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. Data from 2021 came from the National Bureau of Rural Revitalization).

Rural entrepreneurship needs the participation of talents, capital, land and other resources [6,7,8,9]. Talent and capital can be obtained through entrepreneurial bricolage. The imbalance between the supply and demand of construction land has become the primary factor restricting the development of rural entrepreneurship, which is embodied in the fact that rural entrepreneurs cannot find suitable production and operation sites and cannot carry out large-scale production. On the one hand, against the background of rapid socio-economic development and rapid expansion of urbanization, rural space is further squeezed, resulting in a more prominent contradiction between the limited availability of rural construction land and the surge in demand for rural entrepreneurial land [10,11,12,13,14]. On the other hand, with the growing number of nationals, food-security issues cannot be ignored. In fact, 120 million hectares (representing the “red line”) cannot be assigned to other uses in China, exacerbating industrial development land conflicts.

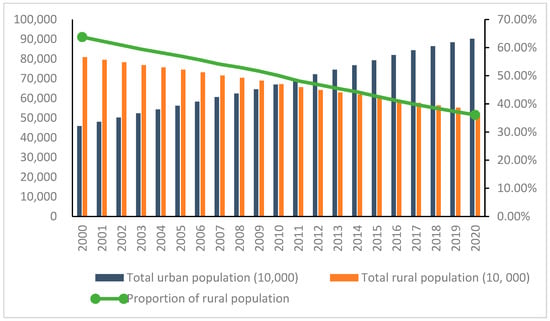

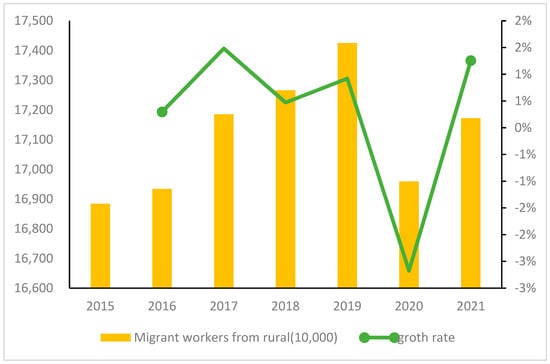

At the same time, the acceleration of urbanization in China has led to a large number of rural populations pouring into cities. As shown in Figure 2, by 2020, the rural population accounted for only 36.11 % of the national population. The rapid development of the urban economy has created a large number of employment opportunities. As shown in Figure 3, in order to achieve better development, a large number of rural labourers chose to work away from rural areas, in urban centres, to obtain higher economic benefits; however, we also need to pay attention to the large number of the rural population that moved to the city, who has also brought the loss of rural labour, rural “hollowing out” and other negative effects, deepening the idle waste of rural land space (farm houses, school buildings, idle factories) and the contradiction relative to the shortage of entrepreneurial construction land; however, due to the impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the number of migrant workers in 2020 showed a cliff-like decline. With the effective control of the epidemic, the number of migrant workers in 2021 increased significantly (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Urban and rural population changes in China from 2000 to 2020. (Data from the Seventh National Census Bulletin of National Bureau of Statistics of China).

Figure 3.

Number of migrant workers in China from 2015 to 2021. (Data from the China National Bureau of Statistics 2015-2021 Monitoring Survey of Migrant Workers).

Previous studies on solving the difficulty of land use for rural entrepreneurship have focused on two aspects. On the one hand, the overall planning of urban and rural construction land has been regarded as an effective means to balance the contradiction between land demand for economic development and land protection. For instance, some towns reserve a small number of land lots for new industries and new forms of business in rural areas [15,16,17,18,19]; however, some local governments, guided by Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and tax revenue, allocate all or most of the available construction land to non-agricultural industries, resulting in a certain gap between the actual demand for construction land for agriculture-related industries and the actual supply. On the other hand, according to development needs, rural industrial land areas have increased in China, but only for traditional agricultural industries such as planting and breeding, thus excluding the demand for non-agricultural entrepreneurial construction land for many new rural industries [16,20] (the total land used for construction was 4,086,666.7 hectares, of which 21,933,333.3 hectares, or 53.67%, was used for rural construction in China [21]). At the same time, due to the unreasonable distribution of regional construction land and the general phenomenon of rural hollowing [22], a large amount of land is used inefficiently or left idle, resulting in the waste of land resources [23,24,25,26]. Therefore, how to fill the huge demand gap for rural entrepreneurial construction land is an important issue worthy of scholarly discussion.

The purpose of this paper is to explore a feasible method to alleviate the difficulty of rural entrepreneurial construction land in China, and to demonstrate its feasibility by taking marginal land as an important resource supplement to solve the problem of rural entrepreneurial construction land in China. Through a review of previous studies, we found that few works have analyzed issues relative to rural entrepreneurial construction land, and these studies have mainly focused on the status, policies, and other aspects. Some scholars have noticed that there are large amounts of wasteland and residential land in rural areas that have been extensively left idle for a long time [27,28,29,30,31,32]; however, there are no clear answers to how to use these marginal land resources to support rural entrepreneurship and development. In our study, we believe that the utilisation of idle land in rural areas, such as idle farmhouses, workshops, and school buildings, can be improved by innovative use and transformed into land for production, which is an effective way to alleviate the problem of land use for rural entrepreneurship. Considering the current background of China, the rational use of marginalized land for rural entrepreneurship could optimize land-use structure, improve village appearance and promote rural revitalisation and regional sustainable development, which have great practical significance [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

2. Background and Methods of Analysis

There are various interpretations of “marginal land” depending on different research backgrounds; generally, it is referred to as land not used for production, wasteland, or inadequate or idle land [41,42]. The concept of marginal land varies according to its application areas, management objectives, countries and organisations. For example, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) proposed that marginal lands are climate-poor and hard to cultivate, such as deserts and saline-alkali land. The United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Protection Agency (USDA-NRCS) proposed that marginal land is affected by soil physical, chemical or environmental factors, which restrict crop production. In the field of ecology, the marginal land mainly focuses on the vulnerability of the land ecosystem. In the field of economics, the form of marginal land is various and the scope is difficult to define. Generally, marginal land is defined according to the economic feasibility of land use. Based on the research results of a review of relevant scholars [43,44,45,46,47], we define “marginal land” as idle land that has been vacant for more than three years in rural areas and whose resources are not used for agricultural production, rural planning or other social purposes. Some scholars have found that there is a large waste of marginal land resources in rural China and have put forward that these land resources can be used as rural entrepreneurial development land, but no specific implementation plans for how to use them have been proposed so far.

China and most developing countries are in the stage of rapid urbanisation. The contradiction between the growth of construction land demand and the protection of agricultural land is prominent. The land-use conflict between cities and villages may also become more and more intense with the growing demand for construction land [48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. On the one hand, China is the most populous country in the world, facing serious food-security problems. To ensure the food security of 1.4 billion people, the “red line of cultivated land” cannot be assigned to other uses [55,56,57]. On the other hand, the deepening of the urbanisation process inevitably occupies rural construction land, which makes the space of rural construction land further tighten and aggravates the problem of rural entrepreneurial land [58]. Therefore, how to break through the bottleneck of the scarcity of rural entrepreneurial construction land without impeding food security and increasing construction land areas is the main source of pressure for rural entrepreneurship [59,60].

Over the years, research on land-system reform, land-use situation, land-use policies, and regional sustainable development has been very comprehensive in China [61,62,63], with one of the aims being finding an effective way to solve the problem of land construction for entrepreneurship land. It should be emphasized that this effective method is not aimed to expand non-agricultural land on a large scale in rural areas, nor add new construction land areas, but to better tap the marginal land characterized by idle and inefficient production in rural areas and transform it into rural entrepreneurial construction land resources through certain policy guidance, so as to promote the development of rural industries. Marginal land use is a hot topic worldwide [44,64,65,66]; our research study, in this sense, conforms to the needs of development and can offer the Chinese experience to other countries facing the same problem.

We adopted the following overall research approach:

Step 1: Identification of the questions. We hope to answer the following three questions by exploring the land-use strategies adopted by the subjects and analyzing the types of data available: (1) What methods have been used in China to obtain rural entrepreneurial construction land? (2) What obstacles may exist in the process of marginal land use in rural areas? (3) Can the use of marginal land aimed to increase rural entrepreneurial construction land effectively enhance rural economic development?

Step 2: Case selection. We selected the following cases of idle houses, idle workshops and idle school buildings in rural areas that aimed to solve the problem of rural entrepreneurial land: (1) Activation Plan for Idle Farmhouse in Shaoxing City, Zhejiang Province; (2) “Zero Rent” Scheme for Unoccupied School Buildings in Xinmin Village, Hainan Province; (3) Renovation of Idle Workshop in Youfangtou Village, Shanxi Province.

Step 3: Data collection. Our research data were obtained from government reports, a literature review and the author’s survey in relevant fields. The research data on the Activation Plan for Idle Farmhouse in Shaoxing City mainly came from the literature review [29,62,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74]. The research data on the “Zero Rent” Scheme for Unoccupied School Buildings in Xinmin Village came from the literature review and official data [63,75,76,77,78,79,80,81]. The research data on the Renovation of the Idle Workshop in Youfangtou Village came from the author’s visits and investigation. At the same time, in order to further explore similar cases, we selected a case from the United States relative to the utilisation of idle schools and a case from South Korea relative to the utilisation of idle workshops for a comparative analysis [79,80,82,83,84,85,86,87].

Step 4: Case analysis. There are huge differences in natural resources and economic conditions in rural areas of China, and the problem of rural land construction needs to be solved by applying different methods. Based on the existing research data, we conducted an in-depth analysis of the utilisation status, economic benefits, contributions to rural revitalisation and some existing problems of rural idle farmhouses, school buildings and workshops in this study.

Step 5: Case summary. We analyzed and summarized the utilisation methods, achievements, and shortcomings of marginal land resources in the three research cases and answered the three questions raised in the first step of the research method, so as to provide an effective reference for similar countries or regions to solve the problem of rural entrepreneurial construction land.

3. Results: Responses to the Shortage of Land Resources for Rural Entrepreneurship Construction in China

3.1. Activation Plan for Idle Farmhouse in Shaoxing City

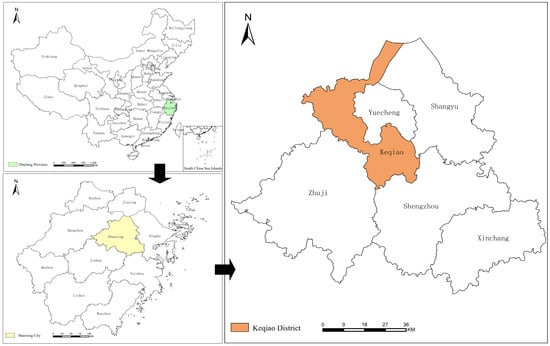

In our study, idle houses refer to farmer houses built on village collective land with clear property rights, uninhabited for more than one year and with no practical use. According to the data from “China Rural Development Report 2018”, the country’s rural collective construction land was 19 million hectares in 2018, 70% of which were homesteads, about 30% of which were idle, and the total amount was close to 4 million hectares [67]. Shaoxing City is one of the most dynamic cities in China’s private economy. Different from the rapid development of the urban social economy, the shortage of construction land limits the development of rural industry in Shaoxing [68]. As shown in Figure 4, there are 1140 such idle rural houses in the Keqiao District of Shaoxing City, Zhejiang Province, covering an area of 8.7 hectares, resulting in a waste of about 15.3 hectares of the construction area. Villages with idle rural houses account for 38 % of the total administrative villages. [29,61,69,70,71,72].

Figure 4.

Study area: Keqiao District, Shaoxing City, Zhejiang Province.

In order to solve the contradiction between the abandonment of a large number of farmhouses and the shortage of construction land in rural areas, Keqiao District in Shaoxing city was built as a pilot to implement the “idle farmhouse activation” plan in 2019. Keqiao District acquired the right to use 70 idle farm houses by leasing them and transforming them into an experience centre of “integration of agriculture and tourism”, bringing in returnee entrepreneurs to invest Chinese Yuan (CNY) 20 million; this project not only solved the employment of 60 local residents, but also brought more than CNY 1.5 million of economic income to the villagers each year and made the village collective increase by more than CNY 500,000 per year. Specific implementation methods: The first step was to acknowledge the need to revitalize the number of idle farmhouses, land and other resources, ownership and distribution. The second was to build a transfer platform for the use right of idle rural housing to provide idle rural housing resources for returning entrepreneurs. The third step consisted of the activation of rural idle housing units or individuals for financial incentives. In the fourth step, the deep integration of idle farmhouses, beautiful rural constructions and agricultural industrialisation had to be activated to promote local economic and social development. For example, in the Meishan Village of Keqiao District, for idle rural housing that is intended to rent and sell, the village committee shall uniformly rent back the use right of rural housing to farmers, and pay rent according to the construction area and different quality. The leased farmhouses are leased to the investors at the original price, and the investors are paid to the village collective according to the rent of CNY 5 per square meter; thus far, the Keqiao District of Shaoxing City has absorbed CNY 1.9 billion of relevant social capital, and 6274 idle agricultural houses have been introduced online, for a total of 186.03 million hectares. This project has increased the number of rural entrepreneurs to 650, generated employment for 4000 farmers, increased farmers’ income by nearly CNY 90 million and increased the collective economic efficiency by more than CNY 70 million.

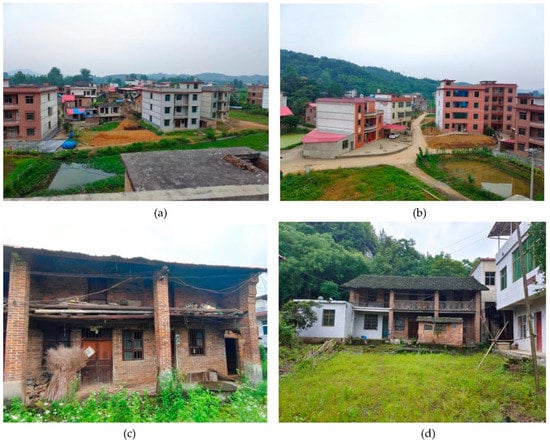

We believe that the reuse of idle rural houses is of great significance for improving village appearance, optimizing the living environment, promoting local employment and entrepreneurship and promoting the high-quality development of the rural society and economy. For example, the practice of “invigorating idle rural houses” in Keqiao district not only does not disrupt the “red line of cultivated land” but also allows village collectives or individuals to develop idle rural houses through cooperation, joint venture, joint stock and other different ways, so as to build old houses and empty houses into farmhouse restaurants, characteristic book stores, art creation bases, etc.; this utilisation mode effectively avoids the waste of land space and gives new value to idle houses. Furthermore, it not only generates employment for local farmers in Keqiao District, but also increases the collective income of the village. As shown in Figure 5, the phenomena of rural idleness and abandonment not only exist in Keqiao, but also in most of China’s rural areas, especially in backward areas. Therefore, the development and utilisation of idle rural housing in Keqiao District is a good reference for other rural areas in China that also have the problem of idle rural housing utilisation.

Figure 5.

Idle farmhouses in Meizhou Village, Shaoyang County, Hunan Province. (Meizhou Village is a typical hollow village with a serious loss of young and middle-aged labour. Due to the lack of industrial support, the local economic development is backward. In order to make a living, people can only go out to work to obtain income, which also leads to serious problems for local left-behind children and left-behind elderly people. The contents shown in (a,b) in Figure 5 are that the local farmers used all the savings saved by migrant workers to build new houses on the outskirts of the village and near the roads; (c,d) show the contents of After local farmers built new houses, they were left idle for a long time, resulting in a waste of land resources. The pictures were taken by our co-author, Lei Zhu).

3.2. “Zero Rent” Scheme for Idle School Buildings in Xinmin Village

Idle school buildings refer to campuses idle due to the withdrawal, merger and suspension of rural primary and secondary schools. According to the survey data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, due to the acceleration of urbanisation, the population in rural areas has decreased, and the number of students in China’s rural areas has dropped sharply. In order to optimize the allocation of educational resources in rural areas, many schools have been merged, leaving the original school buildings and land idle. From 2000 to 2013, at least 323,000 schools in rural areas were idle, resulting in a huge waste of land resources [75]. In other words, if these idle school buildings were reused, the construction land problem of at least 300,000 start-ups would be solved, which would play a great role in solving the employment of local residents and driving economic development. In the process of reviewing the literature, it was found that the idleness of school buildings is a common problem in many countries [76,77,82,83,84,88]. We also found that idle school buildings in different areas can be used to build community centres, public libraries, farmers’ markets, entertainment facilities and retirement homes according to the needs of development [78,79,80,88,89].

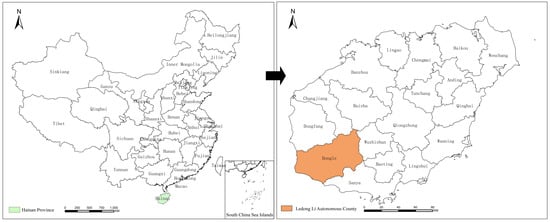

As shown in Figure 6, Xinmin Village is located in Ledong County, Hainan Province, with a total area of 9000 mu. Fishing had been its main industry, and with the implementation of the national fishing ban, industrial development was in urgent need of transformation. In order to attract local young people to return home to start a business and develop the local economy, the village committee of Xinmin Village decided to lease idle school buildings to entrepreneurs returning to develop clothing production. The village collective signed an agreement with the investors, which agreed that in the first three years of the initial stage of entrepreneurship, the investors would pay CNY 50,000 per year for the site rent to the village collective. In the fourth year, the village collective would return all the rent paid by the investors, so as to truly realize the “zero rent” of idle school buildings for entrepreneurial production. Xinmin Village Primary School covers an area of 2.3 hectares, with three teaching buildings and more than 20 classrooms; moreover, the school occupies the best part of the village, playground and classroom area are large, and suitable for enterprise offices. The clothing factory repaired the doors and windows of the school buildings, refitted water and electricity, painted the classrooms, etc. The village committee also invested CNY 500,000 in the garment factory with the help of the state to strengthen the collective economy of the village, and they now receive dividends at the end of the year. An idle school building was transformed into a production workshop, with classrooms hosting parts of the process of the production workshop. The second floor was transformed into offices, meeting rooms and staff dormitories for business reception. The garment factory mainly produces tools and curtains for hotels, and the vocational skills required are not strict, thus being suitable for local villagers. The annual output value can reach more than CNY 3 million and, so far, has allowed more than 50 people from the village to secure employment, with monthly salaries reaching up to CNY 4000.

Figure 6.

Study area: Ledong Autonomous County, Hainan Province.

Our study brings us to believe that idle school buildings in rural areas represent opportunities for innovative schemes to alleviate the difficulty of land use for entrepreneurship in rural areas, with good promotion and reference values. For example, Xinmin Village Primary School was used for production after being idle for 7 years, which solved the problem of local employment and promoted local economic growth [81]. As shown in Figure 7, idle campus land and vacant classrooms can be used as entrepreneurial spaces to provide production places for rural entrepreneurs, which is an effective way to solve the employment problem of local residents and an important driving force for rural economic development.

Figure 7.

An example of a typical idle school building in China. (The content shown in (a) in Figure 7 is a school building that has been idle due to the adjustment of the educational layout. The basic construction of the school building is in good condition. The long-term idle school building not only causes waste of land resources, but also affects the quality of the local living environment; (b) The content of the display is to simply decorate the vacant classrooms and transform them into commercial stores by signing lease contracts with merchants. The content is a school building that has been idle due to the adjustment of the educational layout. It not only causes waste of land resources but also affects the quality of the local living environment; (b) The content displayed is to simply renovate vacant classrooms into commercial shops by signing lease contracts with merchants. The pictures were taken by our co-author, Lei Zhu).

3.3. Renovation of Idle Workshops in Youfangtou Village

“Abandoned architectural heritage” refers to large abandoned industrial areas, uninhabited buildings, abandoned large buildings or areas that have lost their productive and recreational functions [90,91]. A large derelict building can have a negative impact on the local community [92]; however, the reuse of vacant buildings can serve as a potential resource for improving and revitalizing regional development, as well as bringing about environmental, social, and economic sustainability [80,93,94]. In recent years, as the renovation and reuse of idle buildings can save energy and economic costs, policymakers, developers and investors have paid more attention to it. Idle buildings may be used as entrepreneurial construction spaces for rural industrial development [89]. At the same time, the redevelopment of existing idle buildings may be an effective solution to ease the contradiction between urban and rural land uses, which can also create new employment opportunities [88,95].

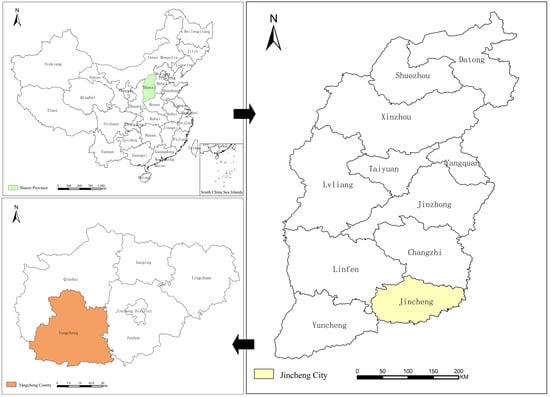

As shown in Figure 8, Youfangtou Village is located in Yangcheng County, Shanxi Province, with an overall area of 660 hectares, a farmland area of 101 hectares, a construction land area of 8 hectares and a homestead land area of 3 hectares. Youfangtou Village, as a demonstration village of new rural construction in Shanxi Province, has achieved good results in terms of developing the rural economy by utilizing marginal land resources such as idle workshops. For a long time, coal mining had been the main economic source of Youfangtou Village. In 2009, however, as China clamped down on coal mining, the village’s coal mining enterprises merged, leaving office buildings behind. Youfangtou Village, with convenient traffic conditions and perfect infrastructure, attracted a number of entrepreneurs. After negotiation, the coal mine workshops that had been idle for 8 years were leased to returning entrepreneurs at the price of CNY 28,000 per year. After simple repairs, the idle workshops were transformed into construction workshops for production, helping entrepreneurs to solve the problem of office space. Subsequently, Youfangtou Village introduced a number of start-up companies in the same way. Through the lease of the idle workshops, Youfangtou Village collects a total rent of about CNY 200,000 per year. In the conversation with the director of the village committee, we learned that the local enterprises using idle workshops to start businesses are mainly small- and medium-sized enterprises with processing industries such as food processing plants and material decoration plants. The profit of such processing enterprises is relatively low; it is difficult for them to bear the high site rent and labour prices in the cities. In contrast, rural areas have low prices and affordable site costs, which can significantly reduce their entrepreneurial costs. Therefore, rural areas with convenient transportation have become the primary choice for returning entrepreneurs.

Figure 8.

Study area: Yangcheng County, Jincheng City, Shanxi Province.

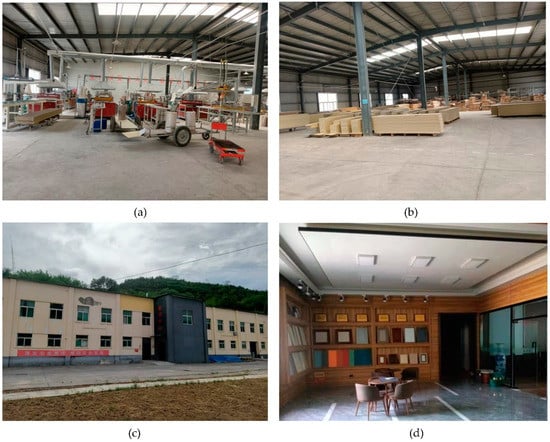

According to our study, the transformation of idle factories in Youfangtou Village not only solved the land-use problem of entrepreneurial enterprises but also brought idle resources into play (Figure 9); this method avoided the waste of resources and has important reference significance for other areas to develop their rural economy by using marginal land resources; however, we also found that Youfangtou Village still faces two prominent problems. On the one hand, the industrial structure of the village is dominated by the primary and secondary industries, and the added value of products is low. On the other hand, in order to seek better development, young and middle-aged people work outside the village, in urban centres, all year round, resulting in the lack of endogenous power for village development. Although the use of idle workshops temporarily alleviates the problem of land shortage for industrial development in Youfangtou Village, it is still difficult to promote the overall revitalisation of rural areas only by renovating idle workshops.

Figure 9.

Renovation of idle workshops. As shown in Figure 9, Youfangtou Village renovated a coal mine that had been idle for 8 years and leased it to two local start-up companies returning home as offices and production sites. The village collective can collect rents of more than CNY 200,000 per year. (a,b) show the production workshop transformed from the idle factory. (c) shows the remodeled appearance of the idle factory building. (d) Shows the office converted from vacant factory building. The pictures were taken by the co-author Yuanyuan Zhang.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Rational Utilisation of Marginal Land Is an Effective Way to Solve the Problem of Rural Entrepreneurial Land Use

Marginal land is an important resource supplement to solve the problem of rural entrepreneurial construction land in China. In the process of urbanisation, reversing the decline of rural areas and stimulating the vitality of rural development is the only way to realize the strategy of rural revitalisation [96,97]. Innovation and entrepreneurship are important driving forces for the activation of the rural economy and the promotion of rural development. When the investment of capital, technology and human resources reaches the threshold, the shortage of construction land is the main factor restricting rural economic growth. Therefore, considering the dual limitations of the limited area of rural construction land and the red line of guaranteed arable land, it is good practice to choose an appropriate way to activate local marginal land resources for rural innovation and entrepreneurship, which can simultaneously achieve multiple objectives.

In urbanisation, the key to food security, environmental protection and regional development is sustainable land use [63,98,99,100]. China’s rural population continues to shrink; it fell to 509 million in 2020, down 164 million from 2010 [101]. At the same time, the acceleration of China’s integration of urban and rural and a large number of rural emigrants result in rural hollowing and idle land problems. Marginal land use in rural areas has broad prospects, as it can be used as a land resource reserve for rural entrepreneurial development and can also create new value, avoiding the waste of resources.

The three cases analyzed in our study (idle farm houses, school buildings and workshops) show that the appropriate utilisation of marginal land resources can alleviate the problem of rural entrepreneurial land and promote rural economic development. Firstly, the structure adjustment of rural and social economy is closely related to land policy and system. With the scarcity of land resources, it is very important to make full use of existing land resources, including inadequate marginal land, to promote regional economic development. Secondly, the decision-making process of marginal land use can give priority to meeting local development needs, so that the types of marginal land use can adapt well to local development directions [82]. The cases we provided were effective in solving the challenges brought by the scarcity of rural construction land to rural entrepreneurship, and the mechanisms and methods used in these case studies could also be applied to other countries or regions facing the shortage of construction land.

4.2. Similarities and Differences between Our Case Studies and Similar Projects around the World

The use of marginal land resources (idle farmhouses, schools, and workshops, etc.) is a common problem all over the world, including in the United States [82,83,84], South Korea [85,86,87] and other countries. The process of socio-economic development varies widely in different regions of the world, so understanding the characteristics of the local social economy is an important prerequisite for formulating marginal land-use plans.

In China, idle school buildings can be reused as factories, warehouses, and breeding farms. Transforming idle workshops into technology parks not only can effectively utilize idle space, but can also enhance the level of regional scientific and technological innovation [102,103]. Idle farm houses can be transformed into family workshops for production in order to obtain higher economic returns [44,104]. The United States also face the problem of disposal of a large number of idle school buildings, which not only hinder local economic development and social progress [83] but also cause environmental damage, including air and water quality problems [82]. A number of studies have shown that converting idle school buildings into new uses, such as community centres, can bring many benefits [79,80,84,94]. In the case of South Korea, we found that an idle factory was creatively transformed into a cafe with cultural value and experience value; as an independent tourist attraction, it promotes the sustainable development of the local economy and also provides us with a new idea for the utilisation of idle factories and similar buildings [85,86,87]. Italy has taken measures to reduce the need for soil sealing by reactivating abandoned or unused buildings, sites, and areas [105]. Numerous studies have shown that the adverse effects of past industrialisation can be offset by improving and integrating the reuse of abandoned areas and buildings [106,107]. For example, Tate Modern, in the UK, was formerly an abandoned power plant [108]. From an economic perspective, Canada’s approach to the disposal of idle buildings is to transform them into economically viable buildings, which not only can save labour and energy costs related to construction, but can also create new employment opportunities in non-residential areas [109]. At the same time, the rational development and utilisation of these idle buildings can improve the local environmental, social, and economic quality, including the preservation of the local identity [110,111,112].

Although different regions use marginal land resources in different ways, a number of studies have proved that the adaptive reuse of these marginal lands can produce better economic and social benefits. Therefore, the rational utilisation of marginal land resources can be an effective way to alleviate the problems of rural entrepreneurial construction land.

4.3. Limitations of This Study and Need for Future Research

Firstly, we emphasize the use of marginal land in rural areas to solve the problem of insufficient land for entrepreneurship. The three case studies here analyzed showed the significant advantages of such practice for solving the construction land problem of rural entrepreneurship [113]; however, these benefits and costs require additional research and quantification from economic and ecological points of view, including direct costs, such as renovation and maintenance costs; risk costs, such as the proportion of benefits and costs of production reusing marginal land; and environmental costs, such as environmental pressure on the region caused by industrial development. At present, there are not enough data to conduct a cost–benefit analysis, especially in terms of costs other than direct costs [114,115,116].

Secondly, here, we do not consider the benefit distribution of marginal land resources, which may be the most important factor due to which a large number of marginal land resources in rural areas are idle [117,118]. The study of China’s marginal land use can enrich the ways to create economic value and may better help us to adopt effective land resource utilisation strategies. It should be noted that the shortage and constraints of capital, talents and other resources faced by rural entrepreneurship can be solved through the entrepreneurial model of resource patchwork; however, the non-agricultural construction land required for the development of new business forms of rural entrepreneurship needs institutional reform as support, which should be solved jointly by rural entrepreneurs themselves, the government and other stakeholders.

Finally, the use of marginal land involves policy-making, environmental carrying capacity, economic development and other fields. Therefore, in future research, it is necessary for researchers from different fields to pay attention to all aspects of marginal land use and ensure the compatibility between policy-making and all stakeholders, so as to create a perfect marginal-land-use system to improve the comprehensive benefits of marginal land use.

5. Conclusions

Rational use of marginal land resources is an important way to solve the problem of rural entrepreneurial construction land in China. Rural entrepreneurship is strong support for increasing farmers’ income, promoting rural development and realizing rural revitalisation; however, with the acceleration of urbanisation, urban land is constantly expanding to the countryside, resulting in the reduction in rural construction land stock. At the same time, China’s permanent basic farmland system to ensure food security has exacerbated the shortage of land for rural construction, limiting the development of rural entrepreneurship. China’s 2020 census data show that the further reduction in the national rural population has exacerbated the phenomenon of idle rural homesteads and housing, resulting in a significant waste of land space. Correspondingly, there is the problem of insufficient land for the development of rural entrepreneurship. Therefore, it is necessary to consider how to use the limited rural land resources to implement rural entrepreneurship and achieve the goal of rural revitalisation under the constraints of limited construction land and food security. Therefore, we suggest that future land use should aim at protecting cultivated land, improving land-use efficiency, and building intensive production and living space. The specific implementation mode is as follows: First, overall planning of urban and rural land use. Second, optimisation of rural land stock, innovation of the way construction land is used and revitalisation of rural construction land resources. Third, as shown in the three cases we selected, creative use of idle farmhouses, workshops, school buildings, etc., to solve the problem of rural entrepreneurial construction land and improve the utilisation rate of marginal land to create maximum economic and social benefits. With the continuous development of urban–rural integration, as well as the rapid growth of new industries and new forms of business in rural areas, it is urgent to excavate rural marginal land resources to meet the needs of rural entrepreneurial construction land.

According to the results obtained in our study, as well as the above-mentioned three-point implementation method, future research should focus on the below.

First, there is the need to fully analyze the costs for rural entrepreneurs to obtain marginal land resources and the benefits that rural marginal land resources can provide to the owners.

Second, how well local residents accept the new use of idle farmhouses, school buildings and workshops requires research attention.

Third, what restrictions and opportunities the users of idle farmhouses, school buildings and idle workshops encounter when adapting to current uses also requires the attention of researchers.

Although there are some shortcomings in our study, the solutions described may provide inspiration for improving the mode of rural economic development and the utilisation of idle land resources. Not only China, but most countries in the world are facing a shortage of land resources and rural depression. We hope that these Chinese case experiences can help other parts of the world that are facing the same dilemma.

Author Contributions

L.Z. developed the research topic; L.Z. wrote the original draft; C.Y. and Y.Z. were responsible for the review and editing. All the authors contributed to writing the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Beijing Social Science Fund, 20LLZZB047; and the Beijing Social Science Fund, 19YJB015; and the Social Science Fund of Beijing Education Commission, SM202010038014.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I sincerely thank Vitina Li, the editor in charge, for her timely feedback and patient communication, which gave me an unforgettable submission experience. At the same time, I would like to thank the reviewers for their affirmation and guidance. Your professional advice has dramatically improved the quality of my thesis and gave me a deeper understanding of thesis writing. Secondly, thanks to the English editor A.S. for taking on the polishing work of this paper. Your excellent workability allows us to avoid mistakes in manuscript writing and help many non-native English-speaking contributors to accurately convey the view. Thirdly, I would like to thank my friend Xiangxin Dai from Central South University of Forestry and Technology and my brother Rui Liu for their help in the writing of my thesis. Finally, thanks to everyone who contributed time and effort to the this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- He, C.; Lu, J.; Qian, H. Entrepreneurship in China. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 52, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, C.; Bruton, G.D.; Chen, J. Entrepreneurship as a solution to extreme poverty: A review and future research directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.W.; Tang, B.; Liu, J. Rethinking China’s Rural Revitalization from a Historical Perspective. J. Urban Hist. 2022, 48, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Xu, W.; Cha, J. Rural entrepreneurship and job creation: The hybrid identity of village-cadre-entrepreneurs. China Econ. Rev. 2021, 70, 101704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogue, D.J. The Study of Population, An Inventory Appraisal; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Fan, P.; Liu, Y. What makes better village development in traditional agricultural areas of China? Evidence from long-term observation of typical villages. Habitat Int. 2019, 83, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonita, E.; Miswardi, M.; Nasfi, N. The role of Islamic higher education in improving sustainable economic development through Islamic entrepreneurial university. Int. J. Soc. Manag. Stud. 2021, 2, 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ataei, P.; Karimi, H.; Ghadermarzi, H.; Norouzi, A. A conceptual model of entrepreneurial competencies and their impacts on rural youth’s intention to launch SMEs. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 75, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1991, 33, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y. An analysis of land use conflict potentials based on ecological-production-living function in the southeast coastal area of China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 122, 107297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Meng, J.; Zhu, L.; Cheng, H. Spatial-temporal pattern of land use conflict in China and its multilevel driving mechanisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 801, 149697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Mason, R.J.; Wang, Y. Governments’ functions in the process of integrated consolidation and allocation of rural–urban construction land in China. J. Rural. Stud. 2015, 42, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, C.; Hurst, W. China’s phantom urbanisation and the pathology of ghost cities. J. Contemp. Asia 2016, 46, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. The Construction of Villages in China. J. Sociol. Ethnol. 2022, 4, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Rural land system reforms in China: History, issues, measures and prospects. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, E.; Wei, H. Transitions in land use and cover and their dynamic mechanisms in the Haihe River Basin, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wen, C. Traditional villages in forest areas: Exploring the spatiotemporal dynamics of land use and landscape patterns in enshi prefecture, China. Forests 2021, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Jiang, G.; Ma, W.; Li, Z. How does the rural settlement transition contribute to shaping sustainable rural development? Evidence from Shandong, China. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 82, 279–293. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Y.; Yu, B. Spatial Reconstruction of Rural Settlements in Central China. J. Landsc. Res. 2018, 10, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Qu, Y.; Tu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y. Development of land use transitions research in China. J. Geogr. 2020, 30, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China. Bulletin of the Main Data of the Third National Land Survey. Available online: http://www.mnr.gov.cn/dt/ywbb/202108/t20210826_2678340.html (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Available online: https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E5%86%9C%E6%9D%91%E7%A9%BA%E5%BF%83%E5%8C%96/2388592 (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Zhou, T.; Jiang, G.; Ma, W.; Li, G.; Qu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, Y. Dying villages to prosperous villages: A perspective from revitalization of idle rural residential land (IRRL). J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 84, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Song, G.; Liu, S. Factors influencing farmers’ willingness and behavior choices to withdraw from rural homesteads in China. Growth Chang. 2022, 53, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Cai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wen, Q.; Marcouiller, D.W.; Chen, J. Understanding the underutilization of rural housing land in China: A multi-level modeling approach. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 89, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Jiang, G.; Li, W.; Zhou, T. How do population decline, urban sprawl and industrial transformation impact land use change in rural residential areas? A comparative regional analysis at the peri-urban interface. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 205, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Mason, R.J.; Sun, P. Interest distribution in the process of coordination of urban and rural construction land in China. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Liu, X.; Li, D.; Zhao, H.; Chen, G. Urban growth simulation by incorporating planning policies into a CA-based future land-use simulation model. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2018, 32, 2294–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L. Chinese Rural Homestead Land: System evolution, disadvantages analysis, and reform path selection. Theor. Appl. Sci. 2019, 79, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Zhang, L. Does cognition matter? Applying the push-pull-mooring model to Chinese farmers’ willingness to withdraw from rural homesteads. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2019, 98, 2355–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Niu, H.; Fan, L.; Zhao, S.; Yan, H. Farmers’ satisfaction and its influencing factors in the policy of economic compensation for cultivated land protection: A case study in Chengdu, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cloutier, S.; Li, H. Farmers’ economic status and satisfaction with homestead withdrawal policy: Expectation and perceived value. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; He, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zeng, S.; Xiao, L. Optimizing the spatial organization of rural settlements based on life quality. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, S. Rural vitalization in China: A perspective of land consolidation. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, J.; Shao, Z.; Iris, Ç.; Pan, B.; Li, X.; et al. A review of China’s municipal solid waste (MSW) and comparison with international regions: Management and technologies in treatment and resource utilization. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Wang, J.; He, K. Analysis on the urban land resources carrying capacity during urbanization—A case study of Chinese YRD. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 116, 102170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.Y.; Guo, Y.K. Research on the function evolution and driving mechanism of rural homestead in Luxian County under the “Rural Revitalization”. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 199, 969–976. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W.; Wang, J.; Qin, X.; Li, Y. Trends and types of rural residential land use change in China: A process analysis perspective. Growth Chang. 2021, 52, 2437–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Rong, S.; Song, M. Poverty vulnerability and poverty causes in rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 153, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Long, H.; Tang, Y.; Deng, W.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Y. The impact of land consolidation on rural vitalization at village level: A case study of a Chinese village. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 86, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Post, W.M.; Nichols, J.A.; Wang, D.; West, T.; Bandaru, V.; Izaurralde, R.C. Marginal lands: Concept, assessment and management. J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 5, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exner, A.; Bartels, L.E.; Windhaber, M.; Fritzd, S.; See, L.; Politti, L.; Hochleithner, S. Constructing landscapes of value: Capitalist investment for the acquisition of marginal or unused land—The case of Tanzania. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Lewandowski, I.; Wang, X.; Yi, Z. Assessment of the production potentials of Miscanthus on marginal land in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Chaubey, I.; Cibin, R.; Engel, B.; Sudheer, K.P.; Volenec, J.; Omani, N. Perennial biomass production from marginal land in the Upper Mississippi River Basin. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 1748–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, D.; Jiang, D.; Liu, L.; Huang, Y. Assessment of bioenergy potential on marginal land in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1050–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliu, I.R. Marginal land use and value characterizations in Lagos: Untangling the drivers and implications for sustainability. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2016, 18, 1615–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.C.S.; Ho, S.P.S. China’s land resources and land-use change: Insights from the 1996 land survey. Land Use Policy 2003, 20, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, R.; Lin, Z.; Chunga, J. How land transfer affects agricultural land use efficiency: Evidence from China’s agricultural sector. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molotoks, A.; Smith, P.; Dawson, T.P. Impacts of land use, population, and climate change on global food security. Food Energy Secur. 2021, 10, e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Liu, C.; Shan, L.; Lin, J.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, G. Spatial-Temporal responses of ecosystem services to land use transformation driven by rapid urbanization: A case study of Hubei Province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Wang, L.; Xie, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. Exploring the global research trends of land use planning based on a bibliometric analysis: Current status and future prospects. Land 2021, 10, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Mu, B.; Ahmad, N. Fostering land use sustainability through construction land reduction in China: An analysis of key success factors using fuzzy-AHP and DEMATEL. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 18755–18777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. What constrains impoverished rural regions: A case study of Henan Province in central China. Habitat Int. 2022, 119, 102477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Li, X. The changing settlements in rural areas under urban pressure in China: Patterns, driving forces and policy implications. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 120, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riao, D.; Zhu, X.; Tong, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, A. Study on land use/cover change and ecosystem services in Harbin, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Anna, H.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, J.; Ouyang, Z. Spatial and temporal changes of arable land driven by urbanization and ecological restoration in China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liao, H.; Zhu, L.; Li, T. A Study on Forming a Construction Land Market That Unifies Urban and Rural Areas during the Process of the New-Type Urbanization in China. Stud. Sociol. Sci. 2014, 5, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, D.; Wang, X.; Wu, L.; Zhao, N. Land ownership and the likelihood of land development at the urban fringe: The case of Shenzhen, China. Habitat Int. 2018, 73, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Du, X.; Castillo, C.S.Z. How does urbanization affect farmland protection? Evidence from China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 145, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, J. Urbanization through dispossession: Survival and stratification in China’s new townships. J. Peasant. Stud. 2015, 42, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Long, H. The process and driving forces of rural hollowing in China under rapid urbanization. J. Geogr. Sci. 2010, 20, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Xu, Q.; Long, H. Spatial distribution characteristics and optimized reconstruction analysis of China’s rural settlements during the process of rapid urbanization. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; He, T.; Lin, Y. Changes in ecological, agricultural, and urban land space in 1984–2012 in China: Land policies and regional social-economical drivers. Habitat Int. 2018, 71, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, P.; Lord, R.A.; João, E.; Thomas, R.; Hursthouse, A. Identifying non-agricultural marginal lands as a route to sustainable bioenergy provision-a review and holistic definition. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallustio, L.; Pettenella, D.; Merlini, P.; Romano, R.; Salvati, L.; Marchetti, M.; Corona, P. Assessing the economic marginality of agricultural lands in Italy to support land use planning. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Liu, Y. Rural restructuring in China. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/jd/wsdwhfz/202008/t20200826_1236869.html?code=&state=123 (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Huang, B.; Jin, M.Q. Taking the comprehensive improvement of rural land as a platform to jointly promote the construction of beautiful countryside. Zhejiang Land Resour. 2012, 11, 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H. Land consolidation: An indispensable way of spatial restructuring in rural China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, S.; Niu, Y.; Chen, M. Village-scale livelihood change and the response of rural settlement land use: Sihe village of tongwei county in mid-gansu loess hilly region as an example. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Hu, B.; Shi, K.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Q. The structural and functional evolution of rural homesteads in mountainous areas: A case study of Sujiaying village in Yunnan province, China. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, X.; Xie, W.; Xie, H. Dynamic change of land use in shaoxing and research on urban sustainable development. J. Anhui Jianzhu Univ. 2019, 27, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of China. Available online: http://www.hzjjs.moa.gov.cn/zjdglygg/202202/t20220209_6388265.htm (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Zhejiang News. Available online: https://zj.zjol.com.cn/news/823712.html (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- China Rural Research Network. Available online: http://ccrs.ccnu.edu.cn/List/Details.aspx?tid=17313 (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Zhang, J.; Chang, G.H. Discussion on the feasibility of idle schoolhouse reconstruction for elderly care facilities in rural areas. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Culture, Education and Financial Development of Modern Society (Iccese2017), Moscow, Russia, 12–13 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. Study on the Elderly-oriented Improvement of Rural Idle Schools. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Architecture: Heritage, Traditions and Innovations (AHTI 2019), Moscow, Russia, 26–27 February 2020; pp. 385–388. [Google Scholar]

- Juan, Y.K.; Hsu, Y.C.; Chang, Y.P. Site selection assessment of vacant campus space transforming into daily care centers for the aged. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2021, 25, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galan, J.; Perrotti, D. Incorporating metabolic thinking into regional planning: The case of the Sierra Calderona strategic plan. Urban Plan. 2019, 4, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merabtine, A.; Maalouf, C.; Hawila, A.A.W.; Martaj, N.; Polidori, G. Building energy audit, thermal comfort, and IAQ assessment of a school building: A case study. Build. Environ. 2018, 145, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunnan Network. Available online: http://society.yunnan.cn/system/2020/11/02/031090511.shtml (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Hale, K. SCHOOL CLOSURES & ADAPTIVE REUSE: A Market Analysis for the Adaptive Reuse of Gaston School in Gaston. NC. 2018. Available online: https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/masters_papers/h989r480r?locale=en (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Sullivan, N.D. Repurposed or Unpurposed? The Evolution of Chicago Public School Buildings Closed in 2013. Bechelor’s Thesis, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Ji, W.; Wang, Z.; Lin, B.; Zhu, Y. A review of operating performance in green buildings: Energy use, indoor environmental quality and occupant satisfaction. Energy Build. 2019, 183, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilland, B. Baker, Kings, Rice Liquor Princesses, and the Coffee Elite: Food Nationalism and Youth Creativity in the Construction of Korean" Taste" in Late 2000s and Early 2010s Television Dramas. Acta Koreana 2021, 24, 77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Eom, J.S. A Study on the Regenerative Characteristics of Cafes Utilizing Idle Industrial Facilities in South Korea-Focusing on the Recent Cases Regenerated from Large Modern Cultural Heritage. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Plan. Des. 2019, 35, 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Eom, J.S.; Yoon, S.H.; An, D.W. The Sustainability of Regenerative Cafes Utilizing Idle Industrial Facilities in South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueckner, J.K. Urban sprawl: Diagnosis and remedies. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2000, 23, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, Y.K.; Cheng, Y.C.; Peng, Y.H.; Castro-Lacouture, D. Optimal decision model for sustainable hospital building renovation—A case study of a vacant school building converting into a community public hospital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micelli, E.; Pellegrini, P. Wasting heritage. The slow abandonment of the Italian Historic Centers. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 31, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifi, Y.; Yüceer, H. Maintaining the absent other: The re-use of religious heritage sites in conflicts. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G. Circular economy strategies for adaptive reuse of cultural heritage buildings to reduce environmental impacts. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, K.E. Cultivating Curriculum: How Investing in School Grounds, the Streetscape and Vacant Land as Urban Ecosystems Can Address Food Security, the Community and Institutions of Public Education. Master’s Thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Alexandria, VA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Kim, K.; Ramirez, G.C.; Orejuela, A.R.; Park, J. Improving well-being via adaptive reuse: Transformative repurposed service organizations. Serv. Ind. J. 2021, 41, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L.; Gargiulo Morelli, V. Unveiling Urban Sprawl in the Mediterranean Region: Towards a Latent Urban Transformation? Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1935–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Chou, R.J. Rural revitalization of Xiamei: The development experiences of integrating tea tourism with ancient village preservation. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 90, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.S. The Inspiration of European Countries’ Rural Value Orientation to China’s Rural Revitalization. Sci. Soc. Res. 2021, 3, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Ke, S. Evaluating the effectiveness of sustainable urban land use in China from the perspective of sustainable urbanization. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Fu, Z.; Chen, L.; Shen, H. Innovation of Zhanjiang Rural Land Circulation Financing Mode under inter Period Credit. Financ. Eng. Risk Manag. 2020, 3, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Kong, X.; Li, Y. Identifying the Static and dynamic relationships between rural population and settlements in Jiangsu Province, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/tjgb/rkpcgb/qgrkpcgb/202106/t20210628_1818826.html (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Shi, K.; Zhang, N. Consideration on the Utilization of Idle Schoolhouses in Rural Primary and Middle Schools. Educ. Res. 2011, 32, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, X.; Zhu, Y.; Song, X.; Ahmad, N. Identification of key success factors for private science parks established from brownfield regeneration: A case study from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, Y.L.; Xue, F.X. Changes in Economic Structure, Village Transformation and Changes in Homestead System: A Case Study of Homestead System Reform in Luxian County, Sichuan Province. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2018, 6, 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Marika, G.; Beatrice, M.; Francesca, A. Adaptive reuse and sustainability protocols in Italy: Relationship with circular economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmeyer, C. Explaining deindustrialization: How affluence, productivity growth, and globalization diminish manufacturing employment. Am. J. Sociol. 2009, 114, 1644–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, V.; Gandino, E. Co-designing the solution space for rural regeneration in a new World Heritage site: A Choice Experiments approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 268, 1077–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, C.; Donnellan, C.; Pratt, A.C. Tate Modern: Pushing the limits of regeneration. City Cult. Soc. 2010, 1, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bullen, P.A.; Love, P.E.D. Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. Struct. Surv. 2011, 29, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J. An Exploratory Comparative Case Study of Repurposed Elementary Schools in Highly Deprived Communities in Ontario. 2020. Available online: https://qspace.library.queensu.ca/handle/1974/28207 (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Dong, M.; Jin, G. Analysis on the protection and reuse of urban industrial architecture heritage. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 787, p. 012175. [Google Scholar]

- Plevoets, B.; Sowińska-Heim, J. Community initiatives as a catalyst for regeneration of heritage sites: Vernacular transformation and its influence on the formal adaptive reuse practice. Cities 2018, 78, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca, G. Evaluation of traditional Sirince houses according to sustainable construction principles. Int. J. Archit. Plan. 2019, 7, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Zhou, W.Y. Research and Practice of Agricultural Cultural Tourism and Vernacular Landscape Design under the Background of Rural Revitalization: A Case study of Jinse Time Agricultural Park in Fu’an Village, Dianjun District, Yichang. J. Landsc. Res. 2021, 13, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; Xu, K. Hollow villages and rural restructuring in major rural regions of China: A case study of Yucheng City, Shandong Province. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2011, 21, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, F.; Macedo, R.; Relvas, S.; Barbosa-Póvoa, A. Simulation of in-house logistics operations for manufacturing. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.M.; Qian, Y.S.; Xie, X.L.; Chen, S.; Ding, F.Y.; Ma, T. Global marginal land availability of Jatropha curcas L.-based biodiesel development. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 364, 132655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Hong, K.R.; Chen, K.Q.; Li, H.; Liao, L.W. Benefit distribution of collectively-owned operating construction land entering the market in rural China: A multiple principal–agent theory-based analysis. Habitat Int. 2021, 109, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).