Abstract

Well-implemented and functioning land administration systems are able to improve the wellbeing of rural households and support the achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. As cadastral data are an essential part of a modern land administration system for documenting and securing the boundaries of parcels, Ethiopia recently embarked on one of the largest land surveying programs for rural land registration in Africa. Cadastral and land registration data provided by the land administration office of the woreda were analyzed using a Geographical Information System to investigate whether parcels of female-headed households were disadvantaged compared to parcels of male-headed households with regard to parcel size, parcel features, and access to infrastructure. In addition, the situation of female-headed households after the land registration process was analyzed in more detail. To this aim, quantitative and qualitative data were collected in the Ethiopian Machakel woreda through a household survey, in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, and key informant interviews. The results document no significant gender discrepancies in parcel features and access to infrastructures. In general, women confirmed an improvement in the wellbeing of female-headed households after the land registration and certification process.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Justification

Globally, land has significant socio-economic value since it is a major source of livelihood [1] and it has a positive effect on rural household welfare [2]. In Ethiopia, land is the key socio-economic asset of the rural community. The Ethiopian government provides holding rights for rural land to rural people. The right to ownership is vested in the state and the public. According to the constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE), land is a common property of the Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples of Ethiopia and shall not be subject to sale or to other means of exchange. Therefore, in Ethiopia, land is not allowed to be sold or exchanged. However, landholders have the right to use the land for a lifetime and can transfer it to family members or others, for instance, by inheritance or as a gift.

Therefore, access to land is the mainstay for most African communities, and land resources are the basis for achieving many of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [3], with a focus on Goal 1, addressing poverty; Goal 2, addressing hunger, food security, nutrition, and sustainable agriculture; and Goal 5, addressing gender equality, as well as the empowerment of women and girls [4].

Land administration constitutes the socio-technical system that governs land tenure, land use, land value, and land development within a jurisdiction [5]. The establishment of secure and easily transferable land rights is a key component of rural development and poverty reduction strategies in many developing countries [6]. Controversially, some experts perceive easily transferable land rights as a risk for the poor, e.g., if the poor have the right to sell their land, then the rich will buy the land and the poor will become poorer and poorer. To avoid this, the Ethiopian government does not allow the sale or exchange of land.

A land administration system enables the identification, registration, and sharing of information about land by using information technologies effectively to provide tenure assurance and to manage natural resources sustainably [7]. Land administration systems, and particularly their core cadastral components, are important infrastructures that facilitate the implementation of land use policies and they support secure property rights and effective land management [8]. Geospatial information, embedded in cadastral sketches, plans, maps, and databases, is fundamental as it documents the boundaries between land parcels [5,8]. Land registration and cadaster together play an important role [9] and are essential to effective and sustainable land use [10,11].

The successful implementation of sustainable land administration systems requires strong national land administration institutions with competence in geospatial information management [12]. In countries of the south, land is often poorly managed and inaccessible [13]. As a consequence, many countries implemented land administration systems incorporating land distribution, land registration, and cadaster programs [14]. For example, Rwanda, China, and Vietnam implemented a cost-effective, fast, inclusive, and scalable land registration program to secure land rights [15,16]. Similarly, Zimbabwe, Namibia, and South Africa have pursued redistributive land reform as a means to address rural poverty [17]. Kenya, Mozambique, Botswana, and Turkey also launched land registration and administration regularization programs [11,18,19,20,21]. Some countries still suffer from a lack of land administration systems. As documented by [22], only 4% of lands in Burkina Faso are under formal rights.

Land registration and cadaster are the key components of a modern land administration system, which promote sustainable development, and are essential tools for land taxation [23,24].

Ethiopia has established a modern rural land administration system by launching the rural Land Registration and Certification Program (LRCP). The LRCP encompasses both the legal aspects of the holder and geospatial information on the parcel. Generally, there are two levels of LRCP in Ethiopia: The first level, the registration of land parcels, began in 1998 when titles were given to landholders, and it is almost complete. The second level is based on cadastral surveying and has been supported by a digitalization program, named the National Rural Land Administration Information System (NRLAIS) [25]. The survey of parcel boundaries and land certificates with parcel maps are provided to rural households. The manual records are documented in computers to facilitate a modern land administration system [25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

Empirical studies document women in developing countries as a disadvantaged group regarding access to and control over land. A study by [22] found that women have less land rights than men. When a woman moves out of the marital home, she loses her right to the land, and most of the land offered to women is far from human settlements, which poses a challenge to reaching tenure security. Similarly, the study by [32] documented a significant gender gap across six African countries using indicators of land rights (land ownership, plot management, control over output, rights for each plot, rights to sell land, use of plots as collateral, rights to bequeath, concern dispute, and tenure system). For instance, in all countries, the percentage of plots owned by women is significantly lower than the percentage of plots managed by women and plots for which women control the outputs. However, the gaps are much larger in Nigeria and Niger than in East and Southern Africa. In Nigeria, only 4% of women, compared to 23% of men, own agricultural land (whether solely or jointly with someone else), and less than 2% of women are the sole owners of land compared to almost 17% of men. Moreover, more than 70% of plots are owned solely by a man, while only 8% are owned solely by a woman. In Niger, 63% of men and 35% of women own agricultural land. In addition, only 14% of women are the sole owners of land compared to 40% of men. Moreover, almost half of plots in Niger (47%) are managed solely by men, while only 13% are managed solely by women. In Nigeria, 72% of the plots are managed by men and they control the output of 53% of the plots. A study by [33] documents that women also are face different forms of tenure insecurity.

In addition, studies provide evidence that female-headed households (FHHs) have less resources, such as land, capital investment, income, cattle, and lower access to credit, than male-headed households (MHHs). For example, the study by [34] found a gender dimension to poverty. The Headcount Index (HCI) of MHHs and FHHs is approximately 39% and 58%, respectively, assuming all members in the household receive an equal food share. In addition, the FHH share of poverty increases from 32% to 41% when a household size adjustment is made. This indicates that FHHs are more likely to be poorer than MHHs, with or without household size adjustment. This is because FHHs have fewer resources (land, cattle, and capital investment) than MHHs. For instance, the percentage of landless FHHs (20%) is higher than the percentage of landless MHHs (6%). The study also found gender inequality in the distribution of income: FHHs receive a lower average per capita income than MHHs, and they rely on low-paid agricultural labor as a major source of income. Similarly, a study by [35] documented FHHs as more likely to be vulnerable to food insecurity than MHHs because of poor access or control over resources. This study attests that the average land size of a FHH (1.56 ha) is less than the average land size of a MHH (2.15 ha). Furthermore, total income, access to credit facilities, climatic information, modern agricultural technologies, extension services, and education are low among FHHs. A study by [36] also found that, in Nigeria, FHHs have less natural resources; for example, only 5.39% of women own land.

As a result, providing rights for women in terms of equal access to land and maintaining tenure security for male as well as female rural households were the major aims of the Ethiopian LRCP.

The authors of Refs. [37,38,39,40] documented that land registration and certification (LRC) improved women’s land rights/tenure security and increased the wellbeing of rural women. In this way, land rights equity is an important tool for increasing empowerment and economic welfare for women in developing countries [41].

Some empirical studies carried out in different regions of Ethiopia employed gender analysis [42,43,44] in line with LRCP. However, they did not analyze the field-level realities of male and female households. Another interesting study, by [28], investigated land size distribution in the Tigray region by using registry data. However, it did not distinguish other gender differences of parcels registered to FHHs and MHHs.

Hence, in the Machakel woreda of the Amhara National Regional State of Ethiopia, existing land administration data were used to investigate gender responsiveness related to landholdings and infrastructure accessibility. In addition, a detailed survey was carried out to gain knowledge about women’s perceptions of the impact of the LRCP and their wellbeing after the implementation of the formal land administration system in the area.

This study is based on two general hypotheses: the LRCP is a key factor in reducing gender disparities in landholdings, the access of parcels to infrastructures, and cultivation-specific features of parcels (H1); the LRCP improves the wellbeing of FHHs (H2). To test these hypotheses, sub-hypotheses were formulated; they are described in Section 2.

1.2. Land Registration and Certification Program (LRCP) in Ethiopia

Land certification and registration programs are addressing the problem of weak property rights [45]. As mentioned above, the formal Rural Land Registration and Certification Program in Ethiopia has been implemented since 1998 to increase the tenure security of rural households and to improve sustainable land use planning. The first level of the LRC process was initially launched in only four regions of the country, namely Tigray, Amhara, Oromiya, and Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples (SNNP). Currently, all regional states have started both first- and second-level land registration and certification activities.

To implement the rural land registration and certification process and other land issues, the Ethiopian government has enacted the legal frameworks and established structures at different levels. After the fall of the Derg regime, the Ethiopian federal government (EPRDF) enacted the country’s constitution in 1995. The administration of land and other natural resources is one concern of this constitution. It mandates the regional governments to administer and manage the regional land and states that the administration of land and natural resources must be implemented in the accordance with federal laws (Art 52 (2d)). Women’s equal land rights is among the major concerns of the constitution: Art 35 (7) states that “women have the right to acquire, administer, control, use and transfer property. In particular, they have equal rights with men with respect to use, transfer, administration and control of land. They shall also enjoy equal treatment in the inheritance of property”. The constitution also provides free rights of land access to rural people (Art 40 (4 and 5)).

The federal government established structures and enacted land rules and regulations to implement and coordinate land issues. The Rural Land Administration and Utilization Directorate under the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) is the responsible institution for coordinating land issues at the federal level. In 1997, the federal government enacted land proclamation (No. 89/1997) in accordance with the constitution. This proclamation was amended and replaced in 2005 by the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Rural Land Administration and Land Use Proclamation (No. 456/2005). In line with the constitution, the federal rural land administration and use proclamation (No. 456/2005) gives rights to regional governments to administer rural land and other natural resources, and the right to enact their own laws and land administration institutions. Art 17 (1) of the proclamation states that “each regional council shall enact rural land administration and land use law, which consists of detailed provisions necessary to implement this Proclamation”. Art 17 (2) states “regions shall establish institutions at all levels that shall implement rural land administration and land use systems, and shall strengthen the institutions already established”. This proclamation also emphasizes gender equality in land access rights to reduce past discrimination against women regarding land access and other property rights. Generally, the proclamation gives detailed information about how to administer and manage rural land.

According to the federal government’s land administration rules and regulations, different regions have established land administration structures and enacted their own land administration proclamations and regulations. As a result, in the Amhara region, land administration structures and institutions have been established from the regional to the local levels to administer and manage rural land. In the Amhara region, in 2001, an organization responsible for administering rural land at the regional level was established, called the Environmental Protection and Land Administration and Use Authority (EPLAUA) [45]; currently, EPLAUA is called the Amhara Region Land Bureau. The rural Land Registration and Certification Program started in the region in 2003 [46].

To implement the land registration and certification process and solve other land issues, the Amhara regional state enacted its land proclamation in accordance with the federal proclamation. Both the previous and the revised land Amhara national regional state proclamations include the equal land rights of women and strengthen the land use rights of women. In the current/revised rural land administration and use proclamation (No. 252/2017), Art 35 (3) states “the land certificate shall include the names of all parties if the land is held by spouses or by other persons in common”. The proclamation also gives priority to women when rural land is being distributed (Art 5 (6)).

As a result, the Amhara region LRCP acknowledges women’s equal land rights, by registering and certifying the land in the names of the husband and wife (joint certification), as well as for female-headed households (single registration).

Generally, the Ethiopian LRCP is implemented via establishing land administration structures at different administration levels (federal, regional, zonal, woreda, and kebeles) and enacting legal frameworks in the federal and regional governments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

This study was conducted in the Machakel woreda found in the East Gojjam Zone of the Amhara National Regional State of Ethiopia (Figure 1). The Machakel woreda is located 330 km north of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, and 235 km east of Bahir Dar, the capital city of Amhara regional state. Machakel has a total population of 133,188 and 26 kebeles (comparable to municipalities; 1 urban and 25 rural) [47]. Furthermore, 50% of the population of the woreda are females and 93% of the population reside in rural areas [48]. Machakel woreda covers 2250 km2 and is a mountainous area with an altitude of 1200 m to 3200 m above sea level [49].

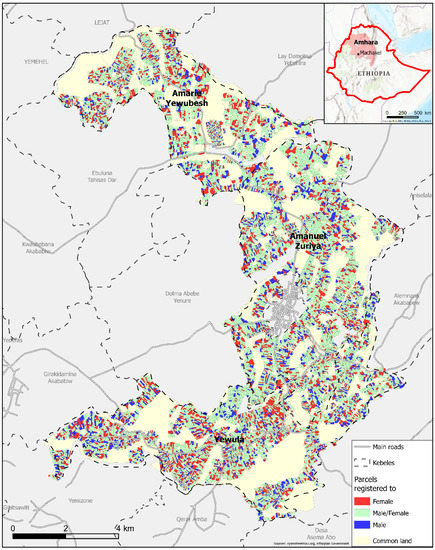

Figure 1.

Map of the study area (three kebeles) documenting different groups of land holders.

Agriculture is the dominant economic activity, on which more than 92% of the total population’s livelihood directly depends, and is characterized by a subsistence farming system. The agricultural system in the study area is mixed farming, with rainfed crops as the main crop and livestock as an additional component. The farm land, human labor, and livestock are therefore the most important livelihood assets of the households [48,50].

The study was carried out in three rural kebeles of the Machakel woreda, namely Amarie Yewubesh, Amanuel Zuriya, and Yewula (Figure 1). The status of the registration and certification process was the main criterion for the selection of the kebeles. In all three kebeles, land registration and certification programs had been largely completed. In addition, the kebeles were close to the residence of the Ethiopian authors, which also facilitated access during COVID-19.

2.2. Data and Sample Design

The information of 14,718 registered parcels (Figure 1) was used to evaluate gender discrepancies in landholdings. The registry data contained the parcel ID, holder name, the area of the parcel, northing and easting centroid, type of registry, book/certificate ID, land use type, fertility status (roughly estimated) of the parcel, etc. As the study focused on household parcels, communal and church land was not considered in this investigation.

A detailed validation of the LRCP was not carried out as this was beyond the scope of this study. As none of the respondents reported any errors (geometry of the parcels or legal allocations) during the interviews, it can be assumed that the LRCP data are reliable and free of significant systematic errors. As analysis was applied for the whole area, it can be expected that even minor errors did not affect the achieved results.

As Figure 1 depicts, household parcels are registered either jointly under the name of wife and husband or by a single holder. As indicated in the legend, male/female denotes household parcels that are registered jointly in the name of both the husband and wife, female indicates parcels registered by a single female, and male indicates parcels that are registered by a single male.

In addition, the following countrywide available geodata were used for the analysis:

- Land cover data (African land cover 2017), provided by ESA and based on Sentinel-2 satellite images; ground resolution: 20 m; https://www.esa.int/ESA_Multimedia/Images/2017/10/African_land_cover (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Digital Terrain Model (Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM)); ground resolution: 1 arc-second (~30 m); https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/usgs-eros-archive-digital-elevation-shuttle-radar-topography-mission-srtm-1 (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- OpenStreetMap; https://download.geofabrik.de/africa.html (accessed on 20 January 2022).

For the assessment of the wellbeing and general situation of FHHs, a qualitative and quantitative survey was carried out. The number of individual FHHs was selected by applying the following formula [51]:

where N is the total number of FHHs in all investigated kebeles according to the land administration systems of the local authorities, e is the sampling error, and n is the total sample size of all kebeles.

n = N/(1 + N (e) 2)

According to Formula (1), the sample size of FHHs selected for the survey questionnaire was 285 from a total of 990 FHHs in the three kebeles. The sampling error e is denoted by 0.05, according to a 95% confidence level.

The sample size of each kebele was assigned proportionally to the total number of FHHs in each of the kebeles (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample size of the study.

Sixteen volunteer FHHs were interviewed in depth. Two focus group discussions (of seven members each) were carried out. Finally, two voluntary key informants of land administration experts were interviewed to obtain a general outlook of the LRCP.

2.3. Data Collection

Numerous data collection techniques were applied to collect qualitative and quantitative information. The cadastral and land registry data were provided by the woreda land administration office and used to analyze the gender discrepancies of landholding. A digital terrain model, land cover map, and OpenStreetMap are open-source data that were downloaded from the respective providers.

To evaluate the situations of FHHs after the LRCP, household surveys, key informant interviews, focus group discussions (FGD), and in-depth interviews were performed. They were used to examine the perception and wellbeing of FHHs. The reason for using mixed methods is that triangulation and crosschecks of the results of different methods improve the accuracy and validity of the overall study. The use of quantitative and qualitative methods provides a richer base for analysis, where data from each method help to interpret the others. Therefore, a combined approach can provide a more conclusive analysis than any single method [52].

The questionnaires provide information on the economic assets of FHHs, such as land size, livestock size, and savings. They also provide evidence on infrastructural accessibilities and FHHs’ perceptions of the LRCP, tenure security, household income, food access, participation status, and general wellbeing of FHHs after the LRCP. Table 2 explains the major variables of the study used to analyze the gender discrepancies in landholdings, while Table 3 shows the variables used to determine the situations of FHHs after the LRCP.

Table 2.

Definitions and measurements of variables to evaluate differences between parcels registered to females and/or males with regard to size, scatter, distance to infrastructure, land cover, and slope.

Table 3.

Definitions and measurements of variables to analyze the situation of FHHs after LRCP.

2.4. Research Hypotheses and Data Analysis Tools

As mentioned in the introduction, the current study is based on two general hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

assumes that the LRCP is a key factor to reduce gender disparities in land holdings, parcel features (slopes, scatterings, and land use), and access to infrastructures. The background for this hypothesis is based on previous studies, for example, [40,42,43,53], which confirm that land registration and certification as well as women’s formal land rights contribute to reducing the gender gap in land issues.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

assumes that the LRCP improved the wellbeing of female-headed households. H2 is also based on the findings of previous studies, for example, [19,37,38,39,41,54,55,56], in which it was found that women’s formal land rights improve women’s wellbeing in terms of land access, tenure security, land rental market, food expenditure, and empowerment.

To test these research hypotheses, the general hypothesis was divided into sub-hypotheses (see Table 4).

Table 4.

The proposed hypothesis and sub-hypothesis of the study and sources of data.

The Geographic Information System Arc GIS Pro (ESRI) was used for the geospatial analysis of the data. SPSS (IBM) and Excel (Microsoft) software were applied for the analysis of quantitative data, using descriptive and inferential statistic tools such as the percentage, mean, standard deviation, chi-square test, t-test, and ANOVA test. The qualitative data of the study were elaborated and interpreted by applying Atlas.ti 9 software.

3. Results

3.1. Types and Gender Disparities after Land Registration and Certification Program

3.1.1. Types of Registration

Of the total registered parcels, 62% were jointly registered under the names of both husband and wife; 22% were registered in the name of a single woman (female-only); and 16% were registered in the name of a single man (male-only). Table 5 documents the trend of the higher amount of jointly registered household parcels in all sample kebeles.

Table 5.

Total registered parcels at the second level of registration in the sample kebeles.

In the Amhara region of Ethiopia, parcels of each rural household were registered, coordinates of boundaries were measured, parcel areas were calculated, and land uses were documented. In the sample kebeles, legal and geospatial information of the majority of parcels was registered, with the mapping of parcels not completed for only a few parcels in the second level. The participants of the focus groups also mentioned the incompleteness of the parcel map, particularly for inherited and donated land, as a problem of the LRC process.

3.1.2. Land Size

The area of the parcels was calculated to examine area differences between holding types. The mean area of jointly registered parcels (0.41 ha) was larger than the mean area of male-only (0.37 ha) and female-only (0.38 ha) registered parcels (Table 6).

Table 6.

Parcel area distribution across the registered types.

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was employed to check whether this difference was significant. The result revealed significant mean differences (F = 22.306, p < 0.001) of the area of the parcel across the registered types (Table 6).

Moreover, the Tukey HSD test showed a significant mean difference (p < 0.001) in the area of jointly registered and female-only registered parcels. Therefore, jointly certified households (MHHs in the case of Ethiopia) had a greater parcel area than FHHs. As a result, the research hypothesis (H1a) that states there is no difference in the parcel areas of males and females was rejected since p < 0.001. There was also a significant mean difference (p < 0.001) between the mean area of jointly registered parcels and the mean area of male-only registered parcels. As households have access to more than one parcel, the total landholding size of the households was also analyzed. The mean of the total land size of jointly registered households was 2.07 ha, whereas the mean land size of female- and male-only registered households was 1.37 ha and 1.20 ha, respectively. This also allows us to reject H1a since jointly registered households had a larger land size than individually registered households.

3.1.3. Slope and Land Cover

This study also investigated gender discrepancies in the slopes and in land cover types of parcels registered to females and/or males. For the analysis of land cover, the African Land Cover dataset provided by the European Space Agency (ESA) was applied (see Figure 2a). This dataset is the most accurate and up-to-date data available. The calculation of slopes was based on the digital terrain model provided by the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (Figure 2b).

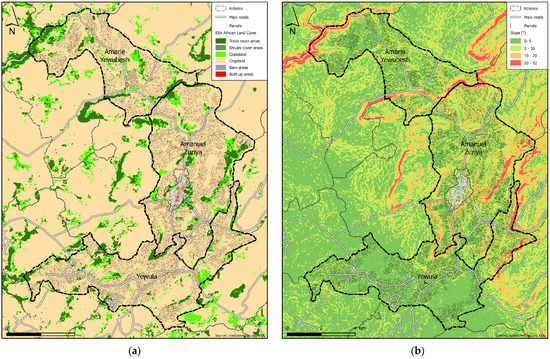

Figure 2.

Features of parcels in the sample area: (a) land cover classifications (sentinel-2: African Land cover 2017); (b) slope classification of parcels based on SRTM.

There was no significant difference in the slopes of parcels registered to females and/or males: the mean slope of jointly registered parcels was 5.36°, of male-only registered parcels was 5.22°, and of female-only registered parcels was 5.06°. Based on this result and Figure 2b, we accepted the proposed hypothesis (H1b) since male- and female-registered parcels had almost the same degree of slopes.

With a ground resolution of 30 m, the DTM is relatively inaccurate, but as shown in Figure 2b, the data show zones of steepness. Due to the lack of detailed DTM data, this investigation aimed to obtain information as to whether parcels are situated in more flat areas or in areas with more topographical roughness. We are aware that terraced parcels could be classified as parcels with a higher slope, but even the cultivation of these terraces has drawbacks compared to parcels in flat areas. Therefore, these data allow general statements about topography.

The GIS analysis of the parcels also documented no difference between male and female parcels in land-use types (see Figure 2a). Cropland was the dominant land use type of all household types in the study area: 92.80%, 92.68%, and 91.59% of jointly, male-only, and female-only registered parcel areas, respectively, were cropland. Therefore, H1c, which states that there is no difference in the land cover types of male and female parcels, was accepted.

Additionally, in this case, a higher ground resolution of the land cover map would be preferable for the existing parcel sizes in the study area. However, as mentioned in the analysis of parcel slopes, we aimed to observe the trends in the whole study area.

3.1.4. Scattering of Parcels and Infrastructure Accessibility

For the analysis of the spatial distribution of parcels, a simple point pattern analysis approach was applied. The geographic center (the center of concentration) for a set of parcels owned by the same person (referring to the holder’s name) was estimated by using the average x- and y-values of the parcels’ feature centroids. The distances between the center of concentration and the parcel centroids were then calculated (Figure 3a).

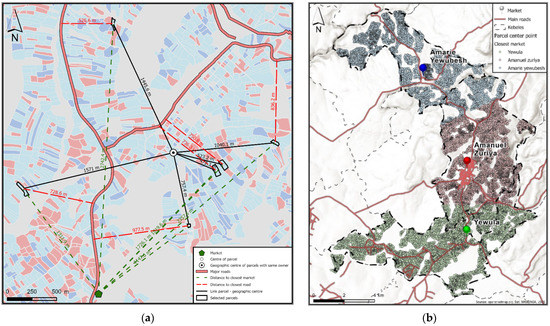

Figure 3.

Scattering and infrastructure accessibility of female and/or male parcels: (a) sample map documenting distances from parcels to center of concentration (black lines), to closest market (green lines), and to main roads (red lines); (b) a general overview of market centers and main roads of the sample kebeles.

Table 7 displays the mean distances (listed according to the number of parcels per households) and standard deviations. The results showed no significant differences between male and/or female parcels, which was also confirmed by an employed ANOVA test (F = 0.119, p > 0.1). Accordingly, H1d was accepted since we did not find significant differences in the scattering of parcels of males and females.

Table 7.

Scattering of parcels: mean distance between parcels per household.

The accessibility to roads and market centers from parcels was assessed. For this purpose, the distance (meters) from the center point of the parcel to the closest market or main road was calculated.

The road network was provided by OpenStreetMap, with all roads except the categories “path” and “footway” taken for the analysis (Figure 3b). The completeness of the road network was checked with other available datasets (online map services and Sentinel 2 data).

A more detailed analysis of infrastructure access also regarding terrain information and footpaths could not be carried out due to lack of data. A detailed path network that includes the smallest footpaths would require additional fieldwork beyond the scope of this study. The available elevation model mentioned above is not suitable for such a detailed analysis.

The applied method documented distances of properties to main roads and alongside a rough overview of accessibility to infrastructure.

Table 8 documents the mean distance of the center point of parcels registered to females and/or males to the closest market and road. The results were similar and showed that there were no significant differences in distances between markets or roads to parcels registered to females and/or males. Hence, hypotheses H1e and H1f were accepted since no significant differences in the accessibility of male and female parcels to markets and roads could be observed.

Table 8.

Distances of center point of the parcels to the closest market and road (near-function).

3.2. Situation of Female-Headed Households after Land Registration and Certification Program

3.2.1. Economic Basis of Female-Headed Households

Economic bases such as land size, livestock size, and savings were assessed to identify differences before and after the LRCP. A paired sample t-test showed a significant mean difference in land size, livestock size, and money savings before and after the LRCP (Table 9). H2a was accepted since land size significantly (p < 0.001) increased after the LRCP. H2b and H2c were also accepted since the number of livestock and the amount of money saved after the LRCP were significantly increased by 1% and 0.1%, respectively.

Table 9.

Mean distribution of land size, livestock, and savings before and after LRCP.

Generally, the economic bases/assets of FHHs were increased after the LRCP. Even though land size was increased after the LRCP, there was a variation in land size with the different marital statuses of women. Thus, the mean land size of widowed women was 1.72 ha, whereas the mean land sizes of divorced and single women were 1.15 ha and 0.71 ha, respectively.

In addition, 33% of the respondents had taken out a loan during the last five years; 90% of them had taken out a loan from the microfinance institution Amhara Credit and Saving Institution (ACSI). This indicates that women borrowed money from formal savings and credit institutions: H2d, which states that women borrowed money from microfinance institutions, was thus accepted.

3.2.2. General Wellbeing of Female-Headed Households

Wellbeing is a multi-dimensional concept embracing elements such as income and consumption, living standards, self-reported happiness (life satisfaction), quality of life, and empowerment [57,58]. Wellbeing can be measured either objectively or subjectively. It can be material or non-material. Objective wellbeing is expressed by the economic bases. Subjective wellbeing is a collection of feelings of an individual, such as feelings of prosperity, happiness, being respected, being acknowledged, and being poor [59]. Subjective wellbeing can be assessed through the perception of satisfaction, happiness, land rights, tenure security, income, food access, participation status, and feelings about general wellbeing.

In the current study, the assessment of subjective wellbeing was related to the resource land. The wellbeing of FHHs after the LRCP was assessed using a questionnaire. The results of the questionnaire are documented below.

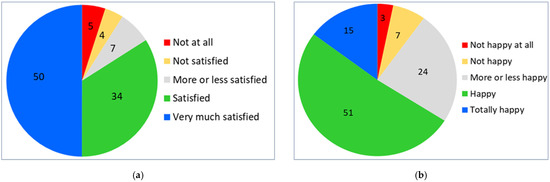

Figure 4 depicts the extent to which the respondents were satisfied with the LRCP (4a) and happy with their quality of life (4b). It documents that the majority (91%) of the sample respondents were satisfied with the LRCP, whereas a few (9%) were not satisfied. Similarly, 90% of the respondents were happy with their household’s quality of life. Therefore, H2e and H2f were accepted since the majority of the respondents were satisfied with the LRCP and happy with their quality of life.

Figure 4.

Percentages of the level of: (a) satisfaction with LRCP; (b) happiness with quality of life.

To test H2g, the perception of FHHs on the current land administration system/legislation was assessed. According to the survey, 78% of the sample respondents replied that the current land administration system provided equal land rights for men and women. As a result, H2g is accepted since the majority of the respondents perceived equal land rights for males and females. However, 22% of the FHHs perceived gender inequality in land holding. They cited small land sizes, corruption, male domination (men taking women’s land either by force or false testimony), and agency affiliation (to be a former government official) as the main reasons for the unequal land rights of men and women.

With regard to the feelings of tenure security, the majority of respondents (86%) felt tenure secured. However, 14% identified problems related to sharecropping and other land-related conflicts as reasons for tenure insecurity. A large number of the respondents were tenure secured, therefore, H2h—women´s tenure security was improved after the LRCP—was accepted. For this reason, 75% of the interviewees rented their land. Therefore, the LRCP contributes to protecting their landholding rights to rent their land. Hence, H2i was accepted since the majority of respondents rented their land after the LRCP.

In total, 66% of the respondents’ households realized an increased income after the LRCP; 28% replied that their income was the same as before the LRCP; and 6% said the situation worsened after the LRCP. H2j was accepted since only 6% of the respondents’ income decreased and more than 50% of the respondents’ income increased after the LRCP.

Moreover, a word cloud analysis [60] was employed to understand the reasons for a household’s income increasing (Figure 5). The total number of words (reasons) listed by the respondents were 18. The minimum- and maximum-frequency words were 1 and 96, respectively. The most frequently reported words were tenure security (96), landholding (43), rent (38), crops (18), and borrow (13). Hence, tenure security, landholding rights, the availability to rent their land, the ability to produce crops, and the borrowing of money from formal financial institutions were the major listed reasons for increases in household income.

Figure 5.

Word cloud analysis: reasons for the household income increases (the size of terms indicates the most frequent words).

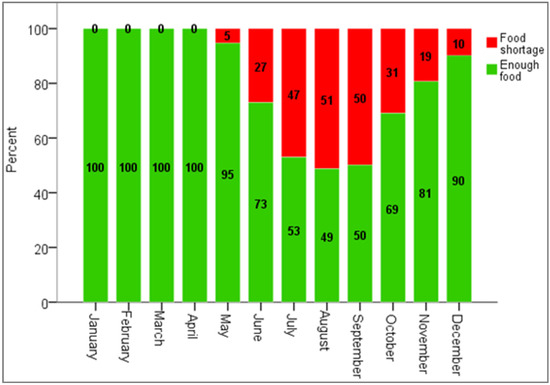

Obtaining enough food throughout the year is a further indicator of household wellbeing. In total, 49% of the respondents responded that their household had enough food (at least three meals per day) during the whole year, while 51% did not have enough food for at least one month of the year. Therefore, H2k was rejected since more than 50% of the respondents did not have enough food throughout the year. The research also identified the months in which a food shortage was faced (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Seasonality of food access.

Finally, the perception of the respondents about the general wellbeing of their households was assessed: 72% had a better sense of wellbeing after the LRCP, whereas 24% of the respondents felt the same as before and 4% felt worse after the LRCP. This is underpinned by the results of another question, where the majority (92%) of the respondents responded that the participation situation in socio-economic and political spheres improved after the LRCP. Hence, H2l was accepted since the majority of the respondents felt their wellbeing improved after the LRCP. Generally, H2 was accepted since all sub-hypotheses were accepted, except H2k, which concerns the wellbeing of FHHs.

Additional analysis was carried out in the study. It was investigated whether the land size was associated with the satisfaction, happiness, food access, perceptions of land rights, and general wellbeing of the respondents. An ANOVA test was employed to examine the relationship of land size to the satisfaction, happiness, and wellbeing of the respondents. It revealed statistically significant differences between the mean land size and satisfaction levels (F = 15.255, p < 0.001), happiness levels (F = 3.512, p < 0.01), and wellbeing (F = 15.026, p < 0.001).

A Tukey HSD test found that the mean land size of more satisfied respondents was larger than the mean land size of respondents who were less or not satisfied with the LRCP. Similarly, the mean land size of respondents with a higher wellbeing was larger than the mean land size of persons who felt their wellbeing was unchanged or reduced (Table 10).

Table 10.

Tukey HSD results of comparisons between perceptions of wellbeing and land size.

In addition, an independent sample t-test (Table 11) documented a significant relationship of land size with food access (p < 0.01) and the perception of equal land rights (p < 0.001). The mean land size of those with enough food throughout the year was larger than the mean land size of respondents who did not have enough food. This result was correlated with the finding that the mean land size of respondents perceiving gender equality was larger than that of respondents with the opinion that the current land administration system does not guarantee equal land rights for males and females.

Table 11.

Land size distribution of respondents and its relationship with food access and the perception of land rights.

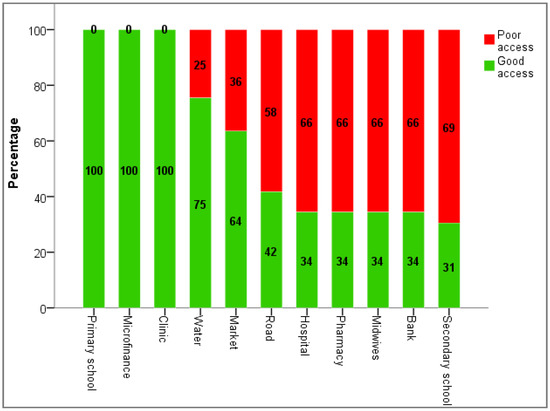

3.2.3. Accessibility to Social Infrastructures

According to the respondents, primary schools, clinics, and microfinance are mostly accessible at the local level. Of the total number of respondents, 75% replied that they had good access to clean and adequate water and 64% stated that they had good access to markets. The majority (more than 50%) of the respondents indicated poor access to roads (asphalt), hospitals, pharmacies, midwives, banks, and secondary schools at the local level (Figure 7). As a result, H2m was not accepted since the respondents had poor access to the majority of social infrastructures (Figure 7). They only had good access to schools, water, and clinics.

Figure 7.

Responses of respondents about the infrastructure accessibility.

Table 12 documents differences between the three sample kebeles with regard to accessibility to specific infrastructures. Slight differences between the sample kebeles were identified in relation to access to clean and adequate water, as well as to markets. Table 12 also provides evidence of missing infrastructures of kebeles. In Amanuel Zuriya, there was better access to secondary schools, to hospitals, to pharmacies, and to bank offices than in the two other kebeles, Yewula and Amarie Yewubesh.

Table 12.

Chi-square test examining infrastructure distributions in the sample kebeles.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effectiveness of Land Registration and Certification Program in Reducing Gender Inequalities

The Ethiopian rural LRCP not only includes the registration and certification of household parcels but also the legal framework of land administration, as well as the implementation and documentation of land rights. Thus, the current land administration system emphasizes women’s land tenure rights by registering and certifying household landholdings either jointly (in the name of husband and wife) or singly (female-only) and by providing equal rights to access land for women. The program has made remarkable progress in registering land titles as well as the determination of parcel boundaries. In addition to land rights, the addition of geospatial information within the LRCP highly contributes to the improvement and sustainability of modern land administration systems [24,61].

However, the key informant identified the shortage of technical experts as a major constraint of an efficient and effective implementation of the land administration tasks in the study area. Even though there were land administration experts at the kebele level, there was only one GIS expert at the woreda level. A study by [62] explains that surveyors’ expertise is an important factor influencing the success of parcel boundary settlement. Therefore, strengthening the technical and operational capacity of land administration experts is important for robust and sustainable digitalization [25]. Thus, the government should increase the number of male and female technical experts (GIS and surveying) to guarantee an efficient and effective implementation of second-level land registration, alongside the sustainable geospatial development of the country.

According to the analysis of the land administration data, no significant gender disparities were observed in land cover type, slope, or the scattering of parcels. Additionally, no differences in parcels registered to females and/or males regarding access to roads and markets were observed. Therefore, the proposed hypothesis Hl was accepted. This confirms a great contribution of the LRCP in the Amhara region to reduce gender gaps of access to resources and infrastructure. Studies by [21,42] found a significant impact of land registration programs in reducing gender inequality on access to land and other natural resources. Similarly, studies by [63,64] found that land tenure reform, including land registration and land certification, has positive effects on women’s land rights and welfare. However, the previous studies did not investigate the field-level realities of male and female parcels. They did not evaluate the parcel features of males and females and considered gender equality in terms of women’s land rights and women’s access to household land and other resources. Therefore, to make up for the shortcomings of the previous studies, the current study provided evidence of male and female parcels by comparing parcel features of MHHs and FHHs using GIS.

Nevertheless, we identified significant differences in land size of male and/or female parcels: hypothesis H1a was not accepted. This finding is in line with previous studies in Ethiopia, e.g., [28,65,66] in the Tigray and Oromia region. Other studies in developing countries, e.g., [34,35,38,67], provide evidence that FHHs have, on average, smaller land sizes than MHHs. If we assumed that joint-registered households are traditionally male-headed, this would fit into our findings.

Generally, the land size of rural households in Ethiopia is becoming increasingly smaller due to population growth [28]. As a result, small land size is not only a problem for FHHs but also for MHHs. Of course, the severity is higher among FHHs. For example, the majority of the interviewees responded that their land was not large enough to secure their livelihood. Some respondents also mentioned that even if their land size was large enough, the outputs of their land would be reduced to cover the consumption of their family since the outputs of the land are shared with sharecroppers. For this reason, the majority of FHHs receive smaller portions of their land products. The problems stated by the participants of focus group discussions are not only the shortage of cultivated land, but also the shortage and conflicts of grazing land for their livestock. They report that “We had a common grazing land in our kebele. However, last time, the government prohibits us to use this land and gives it to investors. Livestock is very important for us to pay tax and to buy fertilizer by selling them. If we haven’t a grazing land, we will not have livestock in the future. There is also a conflict among the community to use this land”.

After the fall of the Derg regime in 1991, land was distributed once. Currently, a person acquires land by inheriting it from their family. In the study area, the government stores illegally used land in a so-called land bank. This land is distributed to landless individuals. For instance, as the key informant in Yewula kebele explains, land from the bank was disseminated to 106 landless youths, but the land size was very small and not satisfactory. This shows the limits of the government to distribute land to new applicants (mostly youths and landless). As a result, the majority of youths have faced land shortage problems [68].

4.2. Female-Headed Households Wellbeing

Women’s tenure insecurity impedes social and economic development. Hence, formal land rights documentation is effective in protecting women’s land rights and is seen as an important means to promote a range of development objectives including poverty reduction [69,70,71]. Respondents of the current study identified an improved access to land for women. Women’s land rights were protected by the LRC process, with their tenure security increased after the LRCP. The results of [42,63,72,73] support these findings. In general, women of the study area perceived that they had the same land rights as men after the LRCP.

Currently, FHHs have landholding rights. However, in the past, their land rights were not granted by law. Women were disadvantaged, especially during divorce. For example, in [69], it was stated that women are more likely to feel threatened by internal sources of insecurity from within the family or the community, particularly when faced with scenarios of divorce or spousal death over the long-term expected duration of their tenure.

Nowadays, women’s land rights in Ethiopia are constitutionalized to make up for past gender discrimination regarding access to land and other natural resources. Hence, the landholding size of FHHs increased after the LRCP. However, variations in household landholding sizes were raised in focus group discussions. Participants highlighted the marital status of households as the main reason for the variations in land size. Similarly, the results of the household survey showed that widowed FHHs had a larger land size than single and divorced FHHs, as in the case of a divorce, the land is split between husband and wife. In the case of the death of the husband, the land is either kept in full by the wife or split between the mother and the deceased spouse’s children. Previous studies [66,74] support this finding.

An advantage of the LRCP for FHHs is the sharing of land in the case of divorce. This issue was also confirmed by focus group discussions and interviews with key experts. For example, the following interviewee explained the advantages of the LRCP and how women’s land rights changed after the LRCP: “LRCP is very important and has great implications for women. In the past, women had no land registered by their name, but the current government gives land rights to women. Now we have land rights. For example, in the past, during divorce, women go back to her family’s home without sharing the land and other properties of the household; only may have her hand-crafts and clothes. However, currently, she has the right to share the land equally with her husband, if the land is jointly registered (Interviewee #7)”.

The LRCP also helps widowed women by keeping their family land after the death of their spouse. After the death of the spouse, the land will be kept in the wife’s name or can be shared with the spouse’s children [74]. Therefore, no one can take the land after the death of a woman’s spouse since her name is registered on the joint certificate. Some women mentioned that having land in their name enables them to marry, and this in turn helps them to make up for the labor shortages of ploughing their land.

Another advantage of the LRCP for FHHs is the right to rent land. The revised Rural Land Administration and Use Determination Proclamation of the Amhara National Regional State (No. 252/2017) specifies that renting means that the right of use is transferred to another person through a contract for a limited period of time in exchange for goods or cash. Moreover, Art 15(1) of this proclamation states that any rural landholder can transfer his/her land-using right to any person through rent contracts as long as it does not displace himself from his holding. Hence, participation in the rental market increased after the LRCP. Sharecropping (Timado) is the dominant type of land renting of FHHs in the study area. Studies [28,75] carried out in the Tigray region support this finding. Similarly, in [6,73,76], it was found that LRC processes enhance the development of the farmland rental market by reducing landholders’ fear of losing land to renters.

The Ethiopian LRCP has a positive effect on FHHs by protecting their usufruct rights in case of renting and of conflicts. The proclamation states that any type of rural land rent contract should be made in written format (Art 15 (3)); the agreement of land rent should clearly indicate the area of the land, the duration of rent, the rental amount, and the way in which the payment is made (15 (4)). Art 15 (8) states that land rent contractual agreements should be registered. Rent agreements up to a period of two years should be presented to the kebele administration and to the office of the rural land administration if the agreement is longer than two years.

However, it was reported during FGD that the majority of FHHs were still renting their land without formal contracts (mostly no written documentation) for a duration of three or four years, as after that time the renter would likely want to claim full access to the land. If FHHs change to another renter, the previous renter does not voluntarily give the land to the new renter. It was also reported that renters did not effectively manage the rented land. In many cases, the renters also did not respect the cultivation of crops preferred by females. Sharecroppers often make the major decisions on the management of land and on cropping patterns. This information collected during FGD is in line with the findings of [76], that before land registration, the renting farmers often violated the usufruct rights of FHHs and claimed full access to the land in which they invested several years of labor.

Therefore, the kebele administration, as well as the land administration offices, must create awareness of formal contracts, specifically for FHHs, and to facilitate this process to reduce rent-related conflicts. In [77], it is recommended that land rental and exchange agreements should be written and should be registered at a governmental office.

Limited access to labor (mostly male labor) and oxen are major reasons that FHHs rent out their land [74]. The customary laws can also influence women to rent out their land since the culture does not allow women to plough their farms [42]. Even though women have oxen, they do not plough their land. In focus group discussion, it was noted that nowadays the culture/community has slightly changed and the younger women are starting to plough their farmland by themselves.

For example, interviewee (#13) stated “I have not enough (male) labor forces and I am also too old to plough my farm. However, my daughter besides her schooling ploughs the farmland. Last year, she grew maize crop and we ate maize grains the same as the community. The community encourages her”.

Similarly, focus group discussion provided evidence that there are some female farmers ploughing their farms themselves, which has changed their livelihood. For instance, one woman, whose husband was in the armed forces, ploughed the land for two years during the absence of her husband. She managed her family well and did not put the land up for rent.

Another important contribution of the LRCP is that women use their land as collateral. A study by [78] found that FHHs are less likely to have access to financial resources: men and male-headed households are more likely to access formal loans. Therefore, formal land rights for women and the LRCP help women to access formal credit. Participants in FGD mentioned that parcel maps are used as collateral to access loans from financial institutions. This proclamation allows landholders mortgage rights for credit institutions. Thus, the LRCP supports women to borrow money from financial institutions. This is confirmed by [21,79] providing evidence that the land registration program provides significant benefits of credit access as credit collateral for investment and economic growth. In general, after the LRCP, women’s access to formal financial credit is increased. This is a great improvement since access to credit is very important to solve financial problems as well as seasonal food shortage problems among FHHs. According to [57], access to credit institutions is very important to women’s livelihoods since they have a positive and significant effect on household wellbeing.

In this way, credit access is improving the wellbeing of FHHs by allowing them to diversify their livelihood strategies. This can be underpinned by the following case in which a woman borrowed money from a formal financial institution and solved her financial problem: “I had a financial problem to improve my life. I solved the problem by borrowing 50,000 Birr (around USD 1000) from Amhara Credit and Saving Institution by my land contracts. I bought a good species of milking cow and support my sister’s son to buy Bajaj (three-wheel vehicle). Now he is working well”.

According to the respondents, the major purpose of borrowing money was for fattening cattle and sheep, buying milking cows and oxen, and buying agricultural inputs (e.g., fertilizer and improved seeds). In addition, the money was used as an investment for non-farming activities (e.g., preparing and selling Arekie, a local alcoholic drink) and for launching other small-scale enterprises. These possibilities contribute to improving the economic bases of FHHs, which can be seen in the increase in income and livestock after the LRCP. Similarly, one study by [78] found formal loans to be strongly associated with agriculture and/or livestock inputs. In general, access to credit is positively and strongly associated with households’ economic wellbeing and poverty alleviation [80,81]. However, FGD revealed high interest rates of credit as a limit for FHHs to borrow money.

The current study found that food availability in the study area was influenced by seasonality. In the study area, food shortages were reported from May to December, with a major shortage in July, August, and September. Figure 6 documents the significant relationship between food shortages and the rainy season (Kiremt) in June, July, and August. During the rainy season, no crop is harvested and the previously harvested surplus cereals run out steadily. Livelihoods in northern Ethiopia depend on small-scale, mixed, rainfed, subsistence agriculture [82]; therefore, the temporal and spatial variability of rainfall leads to serious food shortages and this is the major reason for the seasonality of food access [83]. In [84], it was also reported that the post-harvest season, particularly from November to March, is a food surplus season, whereas the pre-harvest rainy period (July to August) is a time of food shortages.

The current study also showed households with large land sizes were less likely to experience food shortages. This is confirmed by [35,85], which found a significant impact of cultivated land on food security status; hence, the holding of larger sizes of cultivated land means there is a higher probability of producing more food and sources of cash products than households with smaller sizes of cultivated land.

As documented in Table 10, the land size of FHHs is associated with the happiness, satisfaction, and general wellbeing of the respondents. Households with more land were very happy, felt better, and were more satisfied with the LRCP than those with a smaller land size. This is because in rural Ethiopia, land is the key socio-economic asset and an indicator of wealth and happiness.

Generally, the majority of the respondents perceived that their wellbeing improved and that their income increased after the LRCP. Consequently, they were happier with their quality of life. One study [38] found that women who own land have better wellbeing and a higher social status. Similarly, another study [73] found that farmland registration significantly increases agricultural productivity and net income. The majority of respondents were satisfied by the LRCP since their landholding size and tenure security increased. They could also borrow money through microfinance; hence, their ability to save money after the LRCP increased. As a result, the overall hypothesis (H2) was accepted. For example, interviewee (#5) stated the improvements of women’s wellbeing as: “We women have greatly changed after LRCP. Now we have good clothes, good livelihood, we can go to market and buy what we need, and we are caring (for) our children in a better way than before”.

The following two cases of participants of FGD also underpin how the LRCP program contributes to the improvement of women’s wellbeing:

Case 1: “In the past, I had no land at all; I was a daily worker and led my family with this situation. I was buying grains from the market, but it was not enough for family food consumption. However, currently, I have land and rent it to sharecroppers. Even if there is a problem of sharecropping, I do not have to buy grains, I am just sharing it with the sharecropper. Crops produced from my land are enough for household food consumption. I also sold some cereals and bought clothes for my family. We are now happy living in a better situation than before.”

Case 2: “When my father and mother died, my brothers took all (the) lands of our families. They said you can go anywhere, you are a female and you cannot share our family’s land. They did not allow me to share our family’s land without any reason. Then, I managed my life by selling firewood and local drinks (Arekie and Tella) since I had no land. Now, with the LRCP, I received some land, I am living in a better situation, got married and have children.”

4.3. Accessibility to Social Infrastructures

A lack of basic rural infrastructures, such as roads and potable water, has a negative impact on the livelihood of rural households in general and of FHHs in particular [86]. The key informants believes that land registration, specifically the second level of registration, indirectly contributes to the development of infrastructures since every infrastructure is built or will be developed from the land. They stated that in the past, land was not appropriately registered and certified, but with the LRCP, land is registered and measured. Accordingly, appropriate tax can be collected from the landholders. This contributes to an increased capital income of the woreda; in turn, money will be used to build infrastructures for the communities.

According to FGD and key informant interviews, social infrastructures such as schools, water, and health centers have already improved in the woreda, whereas roads and electricity have not yet improved. Experts confirm that ORDA (Organization for Rehabilitation Development in Amhara) is implementing infrastructure development projects in the woreda, e.g., schools, health centers, and several potable water facilities. As mentioned in FGD, the water problem in most of the kebeles of the woreda can be more or less solved by ORDA. This greatly improves women’s wellbeing, since most of the time in rural areas of Ethiopia, women have to travel several kilometers to have access to water.

In the current study, respondents confirmed the availability of primary schools, clinics, and microfinance at local levels (see Figure 7). Hospitals, banks, and secondary schools are rare at the local level, but they are available at woreda level. The Amanuel Zuriya kebele is located close to the woreda town, and due to this fact, the households of this kebele have good access to hospitals, banks, and secondary schools. FGD participants identified road access and health centers as being very important to rural communities, specifically for women. They mentioned the death of two pregnant women due to the inaccessibility of hospitals and unavailability of midwives (delivery centers) two years ago. Nowadays, the government offers free rural ambulance services to transport pregnant women to the hospital, with the aim of reducing pregnancy-related deaths. This is a good option to reduce the probability of maternal deaths, but it does not solve the problem completely. Women’s livelihood can be improved by establishing and reconstructing rural roads for faster access to hospitals and though the implementation of additional delivery services.

5. Conclusions

Even though all improvements in the community, as well as for FHHs, have not been achieved by the LRCP alone, the remarkable outcomes of the LRCP contribute to creating better conditions for FHHs. In general, the effectiveness of the LRCP in terms of gender equality had great success. The LRCP is a driver for women’s wellbeing through reducing gender differences in access to land and, as a consequence, through the improvement of their economic bases.

This study found no gender discrepancies at the field level after the LRC process and confirmed the hypothesis (H1) that the LRCP is a key factor in reducing gender disparities in landholding, in the access of parcels to infrastructures, and the cultivation-specific features of parcels. Generally, the wellbeing of FHH was improved after the LRCP. Therefore, the second research hypothesis of this study (H2) can be confirmed. However, women’s wellbeing is influenced by seasonal food shortage problems caused by small land sizes and rent-related problems. Governments and development organizations should focus on diversifying livelihood strategies rather than relying only on crop production. In addition, land renting agreements should be documented in a written format and be registered at either the local government or land administration offices according to the duration of the rental contract.

In general, the LRCP can be seen as a means to achieve many SDGs, especially SDG 1 (no poverty), SDG 2 (zero hunger), and SDG 5 (gender equality). Indirectly, the LRCP is the basis for fulfilling further SDGs related to community, economic, and infrastructure development, as they are pivotal to ground land tax systems and financing public investments. The second level of land registration and certification, which contains geospatial data with a large amount of information, is an important step for the development of a modern land administration system in Ethiopia. The existence of computerized cadastral data and parcel maps is an excellent basis for the sustainable geospatial development of communities. All woredas in the Amhara region should complete the second level of land registration to support sustainable land use planning.

The current study documents the importance of cadastral data for gender analysis of landholding. As this study is new in using cadastral data for gender-disaggregated analysis in Ethiopia, it can be used as an input for other researchers to carry out similar parcel-based analyses to document the gender dimension in land ownership. Moreover, development organizations can use the cadaster/registry data to build social infrastructures in appropriate places. Other developing countries can also learn from the experiences of the land registration program in Ethiopia and focus on building cadastral data for the sustainable development of their country.

The current study was conducted in one woreda of the Amhara region. In this way, the findings can represent the situation of the Amhara region, as the legal framework and the stage of completion of the LRCP in the other woredas of Amhara are the same or similar to Machakel woreda, respectively. However, the results cannot be generalized for the whole country, as different regions of the country have different legal frameworks and the registration program is implemented in different ways.

Another limitation of this research is that for the analysis of all available cadastral datasets, the distances for household-related investigations referred to the center point of all parcels owned by the households and not to their dwellings. This was necessary due to the lack of information on residential addresses in the datasets. In addition, the size of the household unit was not included in the analysis due to the unavailability of information in the land registry data.

Therefore, further research is recommended to understand the overall situation of FHHs in Ethiopia and for more detailed dwelling-related and household-unit-size results of FHHs in the study area. Besides the land registration and certification process, there may be other causes that contribute to the wellbeing and satisfaction of rural households. Therefore, future research could investigate other causes, for instance, identifying and quantifying the quality legislation on land rights. Results of the current study can be used for future investigations on the topic of sustainable rural land use planning and infrastructure development.

Generally, the current research summarizes the following recommendations for the improvements of the land administration system and women’s wellbeing.

- The government should employ technical experts in land administration for the effective and efficient implementation of the second level of the land registration and certification process, as well as for the geospatial development of the country.

- Formal contracts of land renting should be registered at governmental offices.

- Government and development organizations should emphasize the diversification of rural livelihoods to reduce land shortage-related problems.

- Government and development organizations should focus on the improvement of social infrastructures such as road access, electricity, schools, and health centers at the local level for the development of rural areas.

- The high interest rate of credit institutions restricts the rural poor population from borrowing money. Therefore, microfinance institutions, specifically, Amhara Credit and Saving Institution, should focus on this situation and provide credit services at an affordable interest rate.

- For the successful implementation of the rural Land Registration and Certification Program and the development of the sustainable land administration system, processes to efficiently maintain the data and their quality should be developed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.M., G.S., R.M. and D.D.; methodology, A.K.M., T.B., R.M., G.S. and D.D.; software, T.B., R.M. and A.K.M.; validation, T.B., R.M. and A.K.M.; formal analysis, T.B., R.M. and A.K.M.; investigation, T.B., R.M. and A.K.M.; resources, A.K.M.; data curation, T.B., R.M. and A.K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.M. and T.B.; writing—review and editing, A.K.M., T.B., R.M., G.S., D.D. and S.K.A.; visualization, A.K.M., T.B., R.M., G.S., D.D. and S.K.A.; supervision, G.S., R.M., D.D. and S.K.A.; project administration, G.S. and R.M.; funding acquisition, R.M. and S.K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Austrian Partnership Programme in Higher Education and Research for Development (APPEAR), a program of the Austrian Development Cooperation (ADC), and was implemented by Austria’s Agency for Education and Internationalisation (OeAD); Project no. 113 “Implementation of Academic Land Administration Education in Ethiopia for Supporting Sustainable Development” (EduLAND2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Machakel woreda rural land administration office for providing the cadastral and land register data and for their cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Andrews, N. Land versus Livelihoods: Community Perspectives on Dispossession and Marginalization in Ghana’s Mining Sector. Resour. Policy 2018, 58, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovo, S. Analyzing the Welfare-Improving Potential of Land in the Former Homelands of South Africa. Agric. Econ. 2014, 45, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbow, C. Use It Sustainably or Lose It! The Land Stakes in SDGs for Sub-Saharan Africa. Land 2020, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawki, N. Norms and Normative Change in World Politics: An Analysis of Land Rights and the Sustainable Development Goals. Glob. Chang. Peace Secur. 2016, 28, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.; van Oosterom, P.; Lemmen, C.; Koeva, M. Remote Sensing for Land Administration. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, H.; Admasu, Y.; Chamberlin, J. Is Land Certification Pro-Poor? Evidence from Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 105483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydinoglu, A.C.; Bovkir, R. Generic Land Registry and Cadastre Data Model Supporting Interoperability Based on International Standards for Turkey. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, D.; Enemark, S.; Zevenbergen, J.; Mitchell, D.; McCamley, G. The Cadastral Triangular Model. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zevenbergen, J. A Systems Approach to Land Registration and Cadastre. Nord. J. Surv. Real Estate Res. 2004, 1, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Krigsholm, P.; Riekkinen, K.; Ståhle, P. The Changing Uses of Cadastral Information: A User-Driven Case Study. Land 2018, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yìldiz, O.; Coruhlu, Y.E.; Biyik, C. Registration of Agricultural Areas towards the Development of a Future Turkish Cadastral System. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekole, S.D.; de Vries, W.T.; Durán-Díaz, P.; Shibeshi, G.B. Analyzing the Effects of Institutional Merger: Case of Cadastral Information Registration and Landholding Right Providing Institutions in Ethiopia. Land 2021, 10, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, Z.X.; Moore, A.B.; Goodwin, D.P. Accessibility of Land Data and Information Integration in Recently-Independent Countries: Timor-Leste Case Study. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2021, 100, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, S.; Smith, J.; Ting, L.; Williamson, I. Developing a Common Spatial Data Infrastructure between State and Local Government-an Australian Case Study. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2002, 16, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byamugisha, F.F.K. Experiences and Development Impacts of Securing Land Rights at Scale in Developing Countries: Case Studies of China and Vietnam. Land 2021, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enemark, S.; McLaren, R.; Lemmen, C. Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration—Providing Secure Land Rights at Scale. Land 2021, 10, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliber, M.; Cousins, B. Livelihoods after Land Reform in South Africa: Livelihoods after Land Reform in South Africa. J. Agrar. Change 2013, 13, 140–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balas, M.; Carrilho, J.; Lemmen, C. The Fit for Purpose Land Administration Approach-Connecting People, Processes and Technology in Mozambique. Land 2021, 10, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizoza, A.R.; Opio-Omoding, J. Assessing the Impacts of Land Tenure Regularization: Evidence from Rwanda and Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayumba, R.N. Capacity Building on Land Registration Systems for Sustainable Development in Kenya. Int. J. Res. Eng. Sci. 2019, 7, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, D.A.; Deininger, K.; Duponchel, M. New Ways to Assess and Enhance Land Registry Sustainability: Evidence from Rwanda. World Dev. 2017, 99, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambio, Y.; Bouayad Agha, S. Land Tenure Security and Investment: Does Strength of Land Right Really Matter in Rural Burkina Faso? World Dev. 2018, 111, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, I.; Enemark, S.; Wallace, J.; Rajabifard, A. Land Administration for Sustainable Development, 1st ed.; ESRI Press Academic: Redlands, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Enemark, S.; Williamson, I.; Wallace, J. Building Modern Land Administration Systems in Developed Economies. J. Spat. Sci. 2005, 50, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abab, S.A.; Wakjira, F.S.; Negash, T.T. Determinants of the Land Registration Information System Operational Success: Empirical Evidence from Ethiopia. Land 2021, 10, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamie, B.A. Land Property Rights and Household Take-up of Development Programs: Evidence from Land Certification Program in Ethiopia. World Dev. 2021, 147, 105626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biraro, M.; Zevenbergen, J.; Alemie, B.K. Good Practices in Updating Land Information Systems That Used Unconventional Approaches in Systematic Land Registration. Land 2021, 10, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, S.T.; Tilahun, M. Farm Size and Gender Distribution of Land: Evidence from Ethiopian Land Registry Data. World Dev. 2020, 130, 104926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, A.K.; Mansberger, R.; Damyanovic, D.; Stoeglehner, G. Impact of Land Certification on Sustainable Land Use Practices: Case of Gozamin District, Ethiopia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinigò, D. The Politics of Land Registration in Ethiopia: Territorialising State Power in the Rural Milieu. Rev. Afr. Political Econ. 2015, 42, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Ali, D.A.; Holden, S.; Zevenbergen, J. Rural Land Certification in Ethiopia: Process, Initial Impact, and Implications for other African Countries. World Dev. 2008, 36, 1786–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavchevska, V.; Doss, C.R.; de la O’Campos, A.P.; Brunelli, C. Beyond Ownership: Women’s and Men’s Land Rights in Sub-Saharan Africa. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2021, 49, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yngstrom, I. Women, Wives and Land Rights in Africa: Situating Gender Beyond the Household in the Debate Over Land Policy and Changing Tenure Systems. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2002, 30, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyaw, D.; Routray, J.K. Gender and Rural Poverty in Myanmar: A Micro Level Study in the Dry Zone. J. Agric. Rural. Dev. Trop. Subtrop. 2006, 107, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kakota, T.; Nyariki, D.; Mkwambisi, D.; Kogi-Makau, W. Determinants of Household Vulnerability to Food Insecurity: A Case Study of Semi-Arid Districts in Malawi. J. Int. Dev. 2015, 27, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladokun, Y.O.M.; Adenegan, K.O.; Salman, K.K.; Alawode, O.O. Level of Asset Ownership by Women in Rural North-East and South-East Nigeria. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2018, 70, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosaena Ghebru, H.; Holden, S.T. Links between Tenure Security and Food Security: Evidence from Ethiopia. SSRN J. 2013, 2343158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, N.; Rodgers, Y.; Kennedy, A.R. Land Reform and Welfare in Vietnam: Why Gender of the Land-rights Holder Matters. J. Int. Dev. 2017, 29, 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, N.; van der Meulen Rodgers, Y.; Nguyen, H. Women’s Land Rights and Children’s Human Capital in Vietnam. World Dev. 2014, 54, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]