Do Agricultural Advisory Services in Europe Have the Capacity to Support the Transition to Healthy Soils?

Abstract

1. Introduction

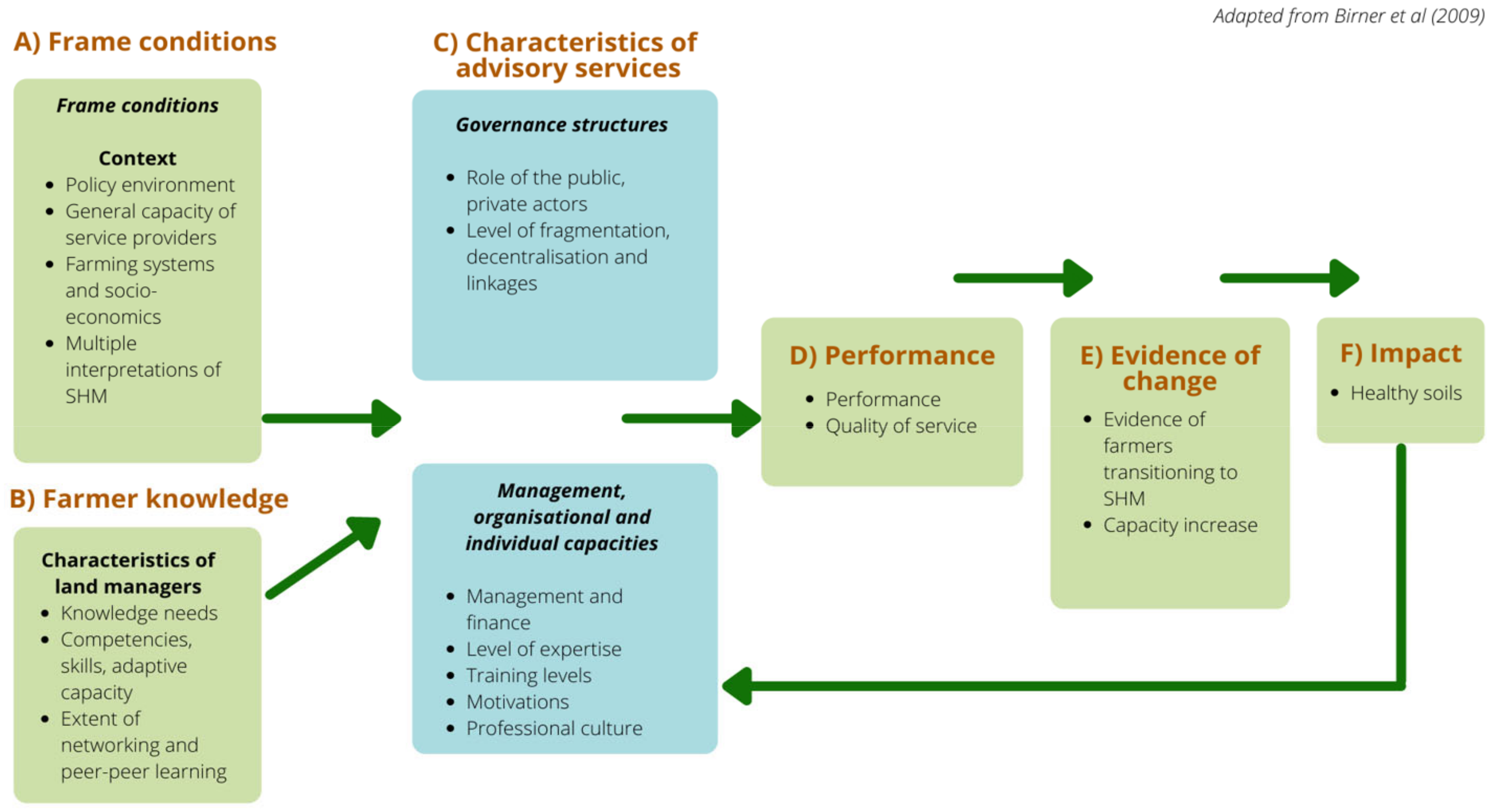

2. Concepts and Framework

- Governance structures: the roles of the public and private sectors and civil society in providing and financing advisory services, the level of decentralisation and the linkages and partnerships among agents in the innovation system.

- Management, organisational and individual capacities: this refers to the expertise, training, motivations of the members of the advisory service as well as their incentives, professional and organisational culture.

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Framing Conditions

4.2. Governance Structures

4.2.1. Governance Arrangements

4.2.2. Integration/Fragmentation

The system is not fully integrated, this affects sustainable soil management negatively because conflicting advice is given, or conflicting objectives are pursued [….] when there are commercial interests, we do find contradiction.ES2

There are companies whose approach is to sell their products, and there are companies that act for example together with associations promoting the welfare of the natural environment recommending the use a range of suitable products.PL2

4.3. Advisory Services Capacity

4.3.1. Management and Organisation for Delivering Advice on SHM

From the public side, we in the agricultural administration are mostly limited by the staff capacities. That is an aspect, which has deteriorated dramatically everywhere in recent years, so if we want to work towards [soil] sustainability, it’s only possible through increased commitment beyond the actual working hours.GR1

There are private companies that have appeared in the market and provide these services at a good level [ …….].. The institutes [public] have the potential, equipment, experience and knowledge, but it seems that due to financial and personnel constraints as well as other obligations, they are unable to respond to the very high market demand, and it is very large, while possibilities for conducting research are limited. Private companies, which are more and more visible on the market, are trying to fill this gap, which is good, because such companies can provide services as part of, for example, soil or plant research projects.PL3

We have to be a profitable organisation, which means that we haven’t the luxury of an infinite amount of time […..] we do the very best we can with the resources we’ve got, but that some of the expectations of what it actually costs to deliver service are unrealistic.UK2

And every consultation service is required to adapt, to continuously improve, and to be up to date with the latest science and technology. I think that’s actually a very positive development [….]. But it is clear to them that if they do not consult their farms in the direction of sustainability, they will lose them completely in 10–20 years.GR1

4.3.2. Level of Advisers’ Knowledge about SHM

Knowledge and Practical Experience

I think, the quality of consultation is high [….] many of the consultants are running agricultural businesses themselves, so they have a certain practical background, or they have simply been working at an agricultural office for many years, so they have a very high level of knowledge [….] so far,[this] has mostly been on crop protection and, I think, especially in terms of sustainability, sustainable soil management, crop rotation, intercropping, things like that—there is still room for improvement.GR2

A strong point of commercial services is that they have capable advisers. With regard to government institutions, their strong point is certainly their infrastructure and the preparation of speakers, i.e., advisors, who are very knowledgeable, but then somehow nothing happens. And this is the weak point, that there is a lack of continuity, on-site continuity, during on-site workshops. Often these advisers lack practical experience and […. ] are unable to keep up with these new solutions and products.PL2

Soil Fertility Focus

Many advisers are enslaved by receiving payment from the company, so they have to advise according to the company’s offer, and this limits their freedom to act; they have the knowledge but they will necessarily be focused on bonuses, on a raise, on finances, and this restricts them.PL3

I don’t think there is one main advisory service that has either a positive or negative impact. Normally advisers have the objective of increasing overall production. The adviser does not go against soil sustainability or soil quality, but [… ] the use of these technologies continuously without other guidelines in the end leads to an overall degradation of the system, mainly of the soil.ES2

Environmental Shift

In recent years companies have emerged that strive towards sustainability, selling crop fortifiers, soil additives and so on. Active local consultants and some farms use these products in their cultivation. This is of course due to the fact that, in the last few years, little has been done in terms of soil fertility and sustainability on many farms. They are now reaching their limits in terms of plant cultivation, they have problems with diseases, with the soil, etc., and companies, which offer the appropriate products, have been in greater demand in recent years.GR1

Heterogeneity

Some of them are extremely knowledgeable and interested [about soil] and have been in their post for quite a long time. Some of them are on short term contracts. And some of them who are less good than others, in terms of their understanding of the technicalities of what they’re talking about, and what they’re being asked to do.UK2

There are consultation services, or even individual consultants on the part of the industry, who attach importance to the topic [soil]. But there are also people who have never bothered with the subject, because it is still possible to achieve good yields with the use of mineral fertilizers or chemical-synthetic pesticides.GR1

Rather than being experts on that particular aspect, we reflect the farming community, in the sense that we are people with a wide range of skills, but an expert in nothing. An expert—he’s talking purely about the soil, and the health of the soil, we will be talking about it on the profitability of the rotation, the control of various injurious weeds, diseases and pests, and then looking at a rotation that is sustainable, which then comes back to the soil. However, we know where to go to get expert [soil] advice.UK1

4.3.3. Advisers’ Training for Delivering SHM Advice

It seems to me that every commercial business tries to train its advisers so that they do at least have this information as regards their own products, how they affect the soil and therefore they must have prior knowledge or learn about the soil, its quality, the processes that take place in the soil environment.PL3

Every adviser needs to participate in continuing education, as the knowledge gained when graduating from college is not enough [….]. It is necessary to educate, educate and again educate advisers and farmers, and to provide this new knowledge about sustainable soil management, which is completely different from the information provided before.PL1

In terms of sustainability, I think they’re both useless. They’ve evolved out of a commercial requirement. So it wasn’t evolved to deliver good, independent, impartial information [… ] they do provide a level of professionalism.UK1

So as far as, is the training fit for purpose for the next generation of advisors? One of the problems that we and the whole industry has got to know that there’s plenty of advisers who are qualified, but not necessarily have a good understanding of the principles[…] you need to be able to understand what you’re doing. And why are you doing it.UK2

From my point of view, there is enough organisation to provide advice on sustainable soil management and there are enough people capable of providing basic guidelines for sustainable soil management but there is a lack of general training on what is the true nature of soil quality beyond nutrient fertility.ES3

4.3.4. Attitudes and Motivations of Different Advisers and AAS

An adviser who belongs to a trade union or a regional agricultural office has a different vocation than an adviser who belongs to a commercial company or to a research centre; their motivations are very different, which means that their inclinations are also very different.ES1

Yes, well, there are advisers who are just all-around good advisers who really give their best and try to constantly educate themselves in order to be able to provide the best possible consultation to the farmers… I think most of the vocational counsellors actually—and yes, I think that of the ones that I know, most really put their full effort into it.GR2

5. Discussion

5.1. Governance Structures

5.2. Advisory Services Capacity

5.2.1. Management and Organisation Capacities for SHM Advice

5.2.2. Individual Capacities for SHM Advice

5.2.3. Narrowing Down

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAS | Agricultural Advisory Service |

| AKIS | Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation System |

| FAS | Farm Advisory System |

| FBO | Farmer based organisation |

| NGO | Non-governmental organisation |

| EU | European Union |

| GAEC | Good Agricultural and Environmental Condition |

| PROAKIS | Prospects for Farmers’ Support: Advisory Services in European AKIS |

| NRL | Norwegian Advisory Service (Norsk landbruksrådgiving) |

| SHM | Soil Health Management |

| SSM | Sustainable Soil Management |

| CVBB | Coordination centre for education and guidance to sustainable fertilisation, Belgium |

| B3W | Coaching service for a better soil and water quality, Belgium |

| OPAs | Professional farmer’s organisations and Agri Food cooperatives, Spain |

| ODRs | Agricultural Advice Centres, Poland |

| NIBIO | Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| CPD | Continuing Professional Development |

References

- European Commission. Communication From the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions—Thematic Strategy for Soil Protection (COM(2006) 231 Final); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stolte, J.; Tesfai, M.; Øygarden, L.; Kværnø, S.; Keizer, J.; Verheijen, F.; Panagos, P.; Ballabio, C.; Hessel, R. Soil Threats in Europe; Publications Office Luxembourg: Luxembourg City, Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Montanarella, L.; Panagos, P. The relevance of sustainable soil management within the European Green Deal. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Juerges, N.; Hansjürgens, B. Soil governance in the transition towards a sustainable bioeconomy–A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1628–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, K.; McKee, A. Co-production of knowledge in soils governance. Int. J. Reg. Rural. Remote Law Policy 2015, 1, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vrebos, D.; Bampa, F.; Creamer, R.E.; Gardi, C.; Ghaley, B.B.; Jones, A.; Rutgers, M.; Sandén, T.; Staes, J.; Meire, P. The Impact of Policy Instruments on Soil Multifunctionality in the European Union. Sustainability 2017, 9, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Voluntary Guidelines for Sustainable Soil Management Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, G.A.; Lilly, A.; Corstanje, R.; Mayr, T.R.; Black, H. Are existing soils data meeting the needs of stakeholders in Europe? An analysis of practical use from policy to field. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, A.; Bradley, H.; Muro, M.; Merriman, N.; Pederson, R.; Tugran, T.; Lukacova, Z. Inventory of opportunities and bottlenecks in policy to facilitate the adoption of soil-improving techniques. SoilCare, Scientific Report Milieu, 2 March 2018. Available online: https://www.soilcare-project.eu/resources/deliverables (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Lobry de Bruyn, L.; Ingram, J. Soil information sharing and knowledge building for sustainable soil use and management: Insights and implications for the 21st Century. Soil Use Manag. 2019, 35, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Velasco-Muñoz, J.F.; López-Felices, B.; del Moral-Torres, F. Barriers and Facilitators for Adopting Sustainable Soil Management Practices in Mediterranean Olive Groves. Agronomy 2020, 10, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A Soil Deal for Europe Implementation Plan; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, J. Are farmers in England equipped to meet the knowledge challenge of sustainable soil management? An analysis of farmer and advisor views. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 86, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgart-Getz, A.; Prokopy, L.S.; Floress, K. Why farmers adopt best management practice in the United States: A meta-analysis of the adoption literature. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 96, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, J.W.; Zeiss, M.R. Soil health and sustainability: Managing the biotic component of soil quality. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2000, 15, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Bossio, D.A.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Rillig, M.C. The concept and future prospects of soil health. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattila, T.J.; Hagelberg, E.; Söderlund, S.; Joona, J. How farmers approach soil carbon sequestration? Lessons learned from 105 carbon-farming plans. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 215, 105204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Bolan, N.S.; Tsang, D.C.; Kirkham, M.B.; O’Connor, D. Sustainable soil use and management: An interdisciplinary and systematic approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 729, 138961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlen, D.L.; Veum, K.S.; Sudduth, K.A.; Obrycki, J.F.; Nunes, M.R. Soil health assessment: Past accomplishments, current activities, and future opportunities. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 195, 104365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinot, O.; Levy, G.J.; Steinberger, Y.; Svoray, T.; Eshel, G. Soil health assessment: A critical review of current methodologies and a proposed new approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 1484–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs, S.; Eclair-Heath, G. Helping UK farmers to choose, use, and interpret soil test results to inform soil management decisions for soil health. Asp. Appl. Biol. Crop Prod. South. Br. 2017, 134, 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Knierim, A.; Labarthe, P.; Laurent, C.; Prager, K.; Kania, J.; Madureira, L.; Ndah, T.H. Pluralism of agricultural advisory service providers–Facts and insights from Europe. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 55, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnone, C.; Simon, B. Cooperation and competition among agricultural advisory service providers. The case of pesticides use. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 59, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kania, J.; Vinohradnik, K.; Knierim, A. WP3—AKIS in the EU: The Inventory Final Report Volume I—Summary Findings; Krakow, Poland, 2014. Available online: https://proakis.webarchive.hutton.ac.uk/sites/proakis.hutton.ac.uk/files/FINAL_REPORT_08_07_2014_VOL_I.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Dhiab, H.; Labarthe, P.; Laurent, C. How the performance rationales of organisations providing farm advice explain persistent difficulties in addressing societal goals in agriculture. Food Policy 2020, 95, 101914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, C.; Nguyen, G.; Triboulet, P.; Ansaloni, M.; Bechtet, N.; Labarthe, P. Institutional continuity and hidden changes in farm advisory services provision: Evidence from farmers’ microAKIS observations in France. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L.; Proctor, A. Beyond fragmentation and disconnect: Networks for knowledge exchange in the English land management advisory system. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garforth, C.; Angell, B.; Archer, J.; Green, K. Fragmentation or creative diversity? Options in the provision of land management advisory services. Land Use Policy 2003, 20, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, K.; Creaney, R.; Lorenzo-Arribas, A. Criteria for a system level evaluation of farm advisory services. Land Use Policy 2017, 61, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L.; De Grip, K.; Leeuwis, C. Hands off but strings attached: The contradictions of policy-induced demand-driven agricultural extension. Agric. Hum. Values 2006, 23, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, K.; Labarthe, P.; Caggiano, M.; Lorenzo-Arribas, A. How does commercialisation impact on the provision of farm advisory services? Evidence from Belgium, Italy, Ireland and the UK. Land Use Policy 2016, 52, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labarthe, P.; Laurent, C. Privatization of agricultural extension services in the EU: Towards a lack of adequate knowledge for small-scale farms? Food Policy 2013, 38, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L.; Jansen, J. Building knowledge systems for sustainable agriculture: Supporting private advisors to adequately address sustainable farm management in regular service contacts. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2010, 8, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, A.B.; Nielsen, H.Ø.; Christensen, T.; Ørum, J.E.; Martinsen, L. Are independent agricultural advisors more oriented towards recommending reduced pesticide use than supplier-affiliated advisors? J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 242, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kik, M.; Claassen, G.; Meuwissen, M.P.; Smit, A.; Saatkamp, H. Actor analysis for sustainable soil management–A case study from the Netherlands. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 105491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, L.; Barros, A.B.; Fonseca, A.F. Deliverable D2. 5: Synthesis Report Innovation, Farm Advice, and Micro-AKIS in Europe; AgriLink: Castanet, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Louwagie, G.; Gay, S.H.; Sammeth, F.; Ratinger, T. The potential of European Union policies to address soil degradation in agriculture. Land Degrad. Dev. 2011, 22, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.; Mills, J. Are advisory services “fit for purpose” to support sustainable soil management? An assessment of advice in Europe. Soil Use Manag. 2019, 35, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House of Commons. Environmental Audit Committee on Soil Health; House of Commons: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Landini, F. How to be a good rural extensionist. Reflections and contributions of Argentine practitioners. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 43, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettle, R.; Crawford, A.; Brightling, P. How private-sector farm advisors change their practices: An Australian case study. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 58, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.; Reed, M.; Skaalsveen, K.; Ingram, J. The use of Twitter for knowledge exchange on sustainable soil management. Soil Use Manag. 2019, 35, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalsveen, K.; Ingram, J.; Urquhart, J. The role of farmers’ social networks in the implementation of no-till farming practices. Agric. Syst. 2020, 181, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daxini, A.; O’Donoghue, C.; Ryan, M.; Buckley, C.; Barnes, A.P.; Daly, K. Which factors influence farmers’ intentions to adopt nutrient management planning? J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 224, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, K.; McKee, A. Use and awareness of soil data and information among local authorities, farmers and estate managers. James Hutton Inst. Intern. Rep. 2014. Available online: https://www.hutton.ac.uk/sites/default/files/files/Use%20of%20soil%20information_final%20report_14Jan2014.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Rhymes, J.M.; Wynne-Jones, S.; Williams, A.P.; Harris, I.M.; Rose, D.; Chadwick, D.R.; Jones, D.L. Identifying barriers to routine soil testing within beef and sheep farming systems. Geoderma 2021, 404, 115298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppe, K. 2. Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems in transition: Findings of the SCAR Collaborative Working Group on AKIS. In Improving Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Labarthe, P.; Caggiano, M.; Laurent, C.; Faure, G.; Cerf, M. Concepts and Theories Available to Describe the Functioning and Dynamics of Agricultural Advisory Services. Learning for the Inventory (PRO AKIS WP3): Deliverable WP2-1 (Pro AKIS: Prospect for Farmers’ Support: Advisory Services in European AKIS; WP2: Advisory Services within AKIS: International Debates); European Union: Brusssels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Birner, R.; Davis, K.; Pender, J.; Nkonya, E.; Anandajayasekeram, P.; Ekboir, J.; Mbabu, A.; Spielman, D.J.; Horna, D.; Benin, S. From best practice to best fit: A framework for designing and analyzing pluralistic agricultural advisory services worldwide. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2009, 15, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, G.; Desjeux, Y.; Gasselin, P. New challenges in agricultural advisory services from a research perspective: A literature review, synthesis and research agenda. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2012, 18, 461–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietra, R.; Heinen, M.; Oenema, O. A Review of Crop Husbandry and Soil Management Practices Using Meta-Analysis Studies: Towards Soil-Improving Cropping Systems. Land 2022, 11, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, I.; Seehusen, T.; Bussell, J.; Vizitu, O.; Calciu, I.; Berti, A.; Börjesson, G.; Kirchmann, H.; Kätterer, T.; Sartori, F.; et al. Opportunities for Mitigating Soil Compaction in Europe—Case Studies from the SoilCare Project Using Soil-Improving Cropping Systems. Land 2022, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.; Lester, B.J.; Du, X.; Reiter, M.S.; Stewart, R.D. A calculator to quantify cover crop effects on soil health and productivity. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 199, 104575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.R.; Karlen, D.L.; Veum, K.S.; Moorman, T.B.; Cambardella, C.A. Biological soil health indicators respond to tillage intensity: A US meta-analysis. Geoderma 2020, 369, 114335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettle, R.; Klerkx, L.; Faure, G.; Koutsouris, A. Governance dynamics and the quest for coordination in pluralistic agricultural advisory systems. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2017, 23, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisinger, P. Organizational Capacity and Organizational Effectiveness among Street-Level Food Assistance Programs. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2002, 31, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labarthe, P.; Laurent, C. The Importance of the Back-office for Farm Advisory Services. EuroChoices 2013, 12, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. The new extensionist: Core competencies for individuals. GFRAS Brief 2015, 3. Available online: https://www.g-fras.org/en/gfras/652-the-new-extensionist-core-competencies-for-individuals.html (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Suvedi, M.; Ghimire, R.; Channa, T. Examination of core competencies of agricultural development professionals in Cambodia. Eval. Program Plan. 2018, 67, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilis, E.; Adamsone-Fiskovica, A.; Šūmane, S.; Tisenkopfs, T. (Dis)continuity and advisory challenges in farmer-led retro-innovation: Biological pest control and direct marketing in Latvia. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2021, 1–18. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1389224X.2021.1997770 (accessed on 20 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L.; Van Mierlo, B.; Leeuwis, C. Evolution of systems approaches to agricultural innovation: Concepts, analysis and interventions. In Farming Systems Research into the 21st Century: The New Dynamic; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 457–483. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, B.; Gerster-Bentaya, M.; Tzouramani, I.; Knierim, A. Advisory services and farm-level sustainability profiles: An exploration in nine European countries. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2019, 25, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Key Figures on the European Food Chain; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, M.J.; Bunce, R.G.H.; Jongman, R.H.; Mücher, C.A.; Watkins, J.W. A climatic stratification of the environment of Europe. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2005, 14, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PROAKIS Project. Prospects for Farmers’ Support: Advisory Services in European AKIS (PRO AKIS). Available online: https://proakis.hutton.ac.uk/ (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- i2connect. i2onnect Project AKiS Country Reports. Available online: https://i2connect-h2020.eu/resources/akis-country-reports/ (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Knuth, U.; Knierim, A. Interaction with and governance of increasingly pluralistic AKIS: A changing role for advisory services. In Knowledge and Innovation Systems towards the Future; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- Klerkx, L.; Petter Stræte, E.; Kvam, G.-T.; Ystad, E.; Butli Hårstad, R.M. Achieving best-fit configurations through advisory subsystems in AKIS: Case studies of advisory service provisioning for diverse types of farmers in Norway. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2017, 23, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuylsteke, A.; De Schepper, S. Agricultural knowledge and innovation systems. In The Case of Flanders; Deparment of Agriculture and Fisheries, Division for Agricultural Policy Analysis and Institute for Agricultural and Fisheries Research: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Knierim, A.; Boenning, K.; Caggiano, M.; Cristóvão, A.; Dirimanova, V.; Koehnen, T.; Labarthe, P.; Prager, K. The AKIS concept and its relevance in selected EU member states. Outlook Agric. 2015, 44, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.-A.; Madureira, L.; Dirimanova, V.; Bogusz, M.; Kania, J.; Vinohradnik, K.; Creaney, R.; Duckett, D.; Koehnen, T.; Knierim, A. New knowledge networks of small-scale farmers in Europe’s periphery. Land Use Policy 2017, 63, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrain, E.; Lovett, A. The roles of farm advisors in the uptake of measures for the mitigation of diffuse water pollution. Land Use Policy 2016, 54, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.; Chiswell, H.; Mills, J.; Debruyne, L.; Cooreman, H.; Koutsouris, A.; Alexopoulos, Y.; Pappa, E.; Marchand, F. Situating demonstrations within contemporary agricultural advisory contexts: Analysis of demonstration programmes in Europe. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2021, 27, 615–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creaney, R.; McKee, A.; Prager, K. Designing, implementing and maintaining (rural) innovation networks to enhance farmers’ ability to innovate in cooperation with other rural actors. Monitor Farms in Scotland, UK. Report for AKIS on the Ground: Focusing Knowledge Flow Systems (WP4) of the PRO AKIS Project; February 2015. Available online: www.proakis.eu/publicationsandevents/pubs (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Knuth, U.; Knierim, A. Characteristics of and challenges for advisors within a privatized extension system. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2013, 19, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, S.P.; Pannell, D. Agricultural extension policy in Australia: The good, the bad and the misguided. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2000, 44, 605–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivers, C.-A.; Collins, A.L. (Un)willingness to contribute financially towards advice surrounding diffuse water pollution: The perspectives of farmers and advisors. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2022, 1–24. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1389224X.2022.2043917?journalCode=raee20 (accessed on 20 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- Compagnone, C.; Hellec, F. Farmers’ Professional Dialogue Networks and Dynamics of Change: The Case of ICP and No-Tillage Adoption in Burgundy (France). Rural. Sociol. 2015, 80, 248–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J. Technical and social dimensions of farmer learning: An analysis of the emergence of reduced tillage systems in England. J. Sustain. Agric. 2010, 34, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywoszynska, A. Making knowledge and meaning in communities of practice: What role may science play? The case of sustainable soil management in England. Soil Use Manag. 2019, 35, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillipson, J.; Proctor, A.; Emery, S.B.; Lowe, P. Performing inter-professional expertise in rural advisory networks. Land Use Policy 2016, 54, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, N.A.; Stankovics, P.; Jarvis, R.M.; Morris-Trainor, Z.; de Vries, J.R.; Ingram, J.; Mills, J.; Glikman, J.A.; Parkinson, J.; Toth, Z.; et al. Have farmers had enough of experts? Environ. Manag. 2022, 69, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanloqueren, G.; Baret, P.V. Why are ecological, low-input, multi-resistant wheat cultivars slow to develop commercially? A Belgian agricultural ‘lock-in’case study. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 66, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, M. Becoming an agricultural advisor—The rationale, the plan and the implementation of a model of reflective practice in extension higher education. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2019, 25, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, L. Factors influencing farmer adoption of soil health practices in the United States: A narrative review. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2016, 40, 583–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerf, M.; Guillot, M.-N.; Olry, P. Acting as a change agent in supporting sustainable agriculture: How to cope with new professional situations? J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2011, 17, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Fry, P.; Ledermann, T.; Rist, S. Social learning processes in Swiss soil protection—The ‘from farmer-to farmer’project. Hum. Ecol. 2009, 37, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L. Advisory services and transformation, plurality and disruption of agriculture and food systems: Towards a new research agenda for agricultural education and extension studies. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2020, 26, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Norway | Flanders (Belgium) | Spain | England (UK) | Germany | Poland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 Representative of NLR (Norsk Landbruksrådgivning) Norwegian Agricultural Advisory Private independent/ FBO | BE1 Researcher and extension worker at Flemish Research Station Public | ES1 Technical director of agriculture and research at association of farmers and livestock breeders FBO | UK1 Independent agricultural consultant Private independent | GR1 Representative from the district administration, Agricultural Office Baden-Württemberg Public | PL1 Professor of Agriculture Science (fruit and veg sector) Public |

| N2 Representative of NLR Private independent/ FBO | BE2 Adviser at the Soil Service of Belgium Private independent | ES2 Professor of soil science and agricultural chemistry Public | UK2 National farm advice manager for a consultancy Private commercial | GR2 Representative from the district administration, Agricultural office, Baden-Württemberg Public | PL2 Company producing micro-organisms and organic grower Private commercial |

| N3 Representative of NLR Private independent/ FBO | BE3 Representative of Flemish Land Agency Public | ES3 Research coordinator at research and transfer centre Private commercial | GR3 Board member of agricultural cooperative, Brandenburg FBO | P3 Company adviser for horticultural sector Private commercial | |

| ES4 Researcher in agricultural research and transfer centre Private commercial |

| Characteristics of AAS for Supporting SHM |

|---|

| Governance Structures |

With respect to advice that supports or impacts soil management:

|

| Management, organisational and individual capacities |

|

| Governance Structure | Norway | Flanders (Belgium) | Spain | England (UK) | Germany | Poland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integration/fragmentation | Private or FBOs cooperate and obtain support from public bodies for SHM | Research institutes collaborate to address soil topics | Synergies exist, but some conflict and tensions at farm level | Horizontally fragmented, but partnerships work with shared goal | Synergies exist, but some tensions between individuals | Synergies between public ODRs and private sector but some tensions |

| AAS capacity | ||||||

| Management and organisation for SHM advice | Good competence and capacity to deliver SHM advice in NRL Staff recruitment and retention is a problem | Reliance on short-term project funding reduces continuity in SHM advice | Good organisation and management in FBOs but limited in others Culture of short-term projects limits outlook | Absence of planning for the necessary SHM skills and staff | Consultation services are well equipped, good resources; public provision has staffing limitations (Brandenburg) | Public sector under-resourced |

| Level of advisers’ SHM knowledge Knowledge and practical experience Soil fertility focus Environmental shift Heterogeneity | Public bodies not very competent or up to date, main role in supporting fertilizer plans and subsidies, but high standard of soil management in the independent NRL | Good knowledge where advice linked to research institutes and independent services but commercial advisers have fertilizer focus | Unequal distribution of quality SHM advice Commercial and technical advisers emphasise fertilizers Big range in SHM advice quality, poor quality linked to new untrained advisers, good quality in organic sector | Some shift in private adviser activities to environmental and soil advice Large range, some excellent advisers (independent and in non-commercial initiatives) but commercial advisers have limited SHM knowledge | Good quality advice in consultation services, but scope could be wider Commercial advisers’ emphasis on fertilization conflicts with advice for other soil functions but some shift to supplying environmental advice | Commercial advisers more active than public advisers but ‘locked-in’ by company goals Knowledgeable public advisers move to private sector Organic sector provides high-quality SHM advice |

| Advisers’ training for SHM advice | Time and resources for soil training are often limited | Good attendance at dissemination events Limited time and resources for soil training in all sectors | Limited SHM training of technical advisers Need continuing education, as college training inadequate No unified certification | Good attendance at dissemination events Good quality CPD courses but could be more integrated | Large range of training courses, with more offered in recent years | In-service training in ODRs All sectors need continuing education to update college training |

| Attitudes and motivations of advisers and AAS | Positive NRL adviser attitudes towards the soil | High level of personal commitment to SHM needed | Horticulture advisers’ commercial motivations can lead to low social value | A range of attitudes linked to advisers’ objectives | High level of personal commitment to SHM needed | Balancing commercial advantage and farmer respect is important |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ingram, J.; Mills, J.; Black, J.E.; Chivers, C.-A.; Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Elsen, A.; Frac, M.; López-Felices, B.; Mayer-Gruner, P.; Skaalsveen, K.; et al. Do Agricultural Advisory Services in Europe Have the Capacity to Support the Transition to Healthy Soils? Land 2022, 11, 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11050599

Ingram J, Mills J, Black JE, Chivers C-A, Aznar-Sánchez JA, Elsen A, Frac M, López-Felices B, Mayer-Gruner P, Skaalsveen K, et al. Do Agricultural Advisory Services in Europe Have the Capacity to Support the Transition to Healthy Soils? Land. 2022; 11(5):599. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11050599

Chicago/Turabian StyleIngram, Julie, Jane Mills, Jasmine E. Black, Charlotte-Anne Chivers, José A. Aznar-Sánchez, Annemie Elsen, Magdalena Frac, Belén López-Felices, Paula Mayer-Gruner, Kamilla Skaalsveen, and et al. 2022. "Do Agricultural Advisory Services in Europe Have the Capacity to Support the Transition to Healthy Soils?" Land 11, no. 5: 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11050599

APA StyleIngram, J., Mills, J., Black, J. E., Chivers, C.-A., Aznar-Sánchez, J. A., Elsen, A., Frac, M., López-Felices, B., Mayer-Gruner, P., Skaalsveen, K., Stolte, J., & Tits, M. (2022). Do Agricultural Advisory Services in Europe Have the Capacity to Support the Transition to Healthy Soils? Land, 11(5), 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11050599