1. Introduction

Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, a socialist public ownership of land was introduced. Based on the ideology that all land was public property, land reform became one of the most paramount tasks when the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) came to power. The nationalization of urban land, corresponding with the collectivization of rural land and gradual abolition of private land ownership, laid the groundwork for the current land system in which urban land is owned by the state and rural lands are owned by village collectives. Under such an arrangement of property rights, there is no transaction of land ownership between individuals. However, with the economic reform and ideology liberation initiated by Deng Xiaoping, the land use rights system, learned from the land leasehold system in Hong Kong, was formed to accommodate the needs of foreign direct investments [

1]. Since then, the land market has gradually formed and played an important role in China’s economy [

2].

In such a land system, the local government firmly controls land resource in its jurisdiction. On the one hand, the local government is the only entity that is endowed with authority to expropriate rural land, by which collective land is converted into state land [

3]. On the other hand, with the establishment of a land bank system, the local government has become the single entity that supplies land in the primary land market [

4]. Therefore, local governments are passionate about exploiting their authority to develop land. They not only directly reap considerable land conveyance fees by transferring land (known as land revenue) but also use land as collateral for local bonds (known as land finance).

1 By utilization by local governments, land has become an indispensable financial source for urbanization and a critical engine for China’s economic growth [

5].

However, the seemingly great power of local governments on land resource is constrained by the central authority [

6]. Since the amendment of Land Administration Law in 1998, land quota, a ceiling of land that is allowed to be converted from agricultural use to non-agricultural use, has been introduced to limit the impulse of local governments to expand their urban areas. Another method the central government uses to regulate land development is a land approval system, which stipulates that each parcel of newly developed land should be approved by either central or provincial government. With the exception of formal means embedded into the land system, a more effective mean for central government to control land use is rooted in political centralization. A top-down controlled personnel system provides the central government a powerful weapon to punish local officials who deviate from central directives.

In this paper, we use the term ‘limited decentralization’ to characterize the relationship between local governments and the central government in land systems. In such a system, local governments are endowed with considerable discretion on land issues, while decentralization is constrained by central authority. We will show that this analytical framework could be used to understand a series of land issues. We believe the degree of decentralization is primarily determined by the purpose of the central government, making decentralization unstable and reversible. During the last decades, the main target of the entire country is to pursue economic development. Compared with the central government, local governments have their advantages on local information, which is critical for economic growth [

7]. Therefore, the central government launched waves of decentralization in land systems to encourage local administrations to function as a ‘developmental state’ [

8,

9]. In recent years, however, with the increased emphasis on farmland protection, ecological system conservation,

2 and the trend of recentralization emerged. By admitting the leading role of the central government, however, we do not suggest that the local government is a mere instrument of policy implementation. Instead, we find that the initiative of local governments is also important. By negotiating and bargaining in some issues and innovating some experimental policies, the locality frequently leads to the change of the degree of decentralization, which further results in rights definition, power distribution, and, consequently, land use policies change over time, as long as there are no conflicts with the main objectives of the central government.

The contributions of this paper to the existing literature are twofold. First of all, this paper speaks to the literature on centralization/decentralization in China studies. Many studies have noticed that the central-local relation is essential to understand the transitional economy in China. Market-preserving federalism theory, for example, argues that the political and economic decentralization has led to a stable central-local government relation and laid the foundation for economic success in China [

10,

11,

12]. Distinct from their general discussions, we focus on a specific and important field, namely the land system, and enrich the relevant literature by uncovering the similarities and differences in decentralization/centralization happened in the land system. Second, this paper provides a new perspective to understand China’s land system. Most studies on land use have focused on the local administrative levels. For example, Zhu noticed China’s gradual urban land reforms since 1984 led to the formation of pro-growth coalition between local government and local enterprises [

13]. However, the role of central government has not been fully discussed. Furthermore, there are few studies incorporating both local and central government to analyze China’s land system, not to mention discussing their interaction and its consequences on land use policies. Our study endeavors to make up these gaps by providing a unified theoretical framework called “limited decentralization”, in which we both analyze the incentives and behavior of local and central government and investigate how their interaction contributes to the formation of land policies.

In the following of this paper, we will first distinguish local governments and the central government and independently discuss their roles in land system, which are the main tasks of

Section 2 and

Section 3. In

Section 4, we introduce how this analytical framework could be applied to understand some land issues. We further discuss the central-local relation from a dynamic perspective and the determinants of the degree of decentralization in

Section 5. The Discussion and Conclusion sections are arranged in

Section 6.

2. Decentralization: Local Governments as Land Developers

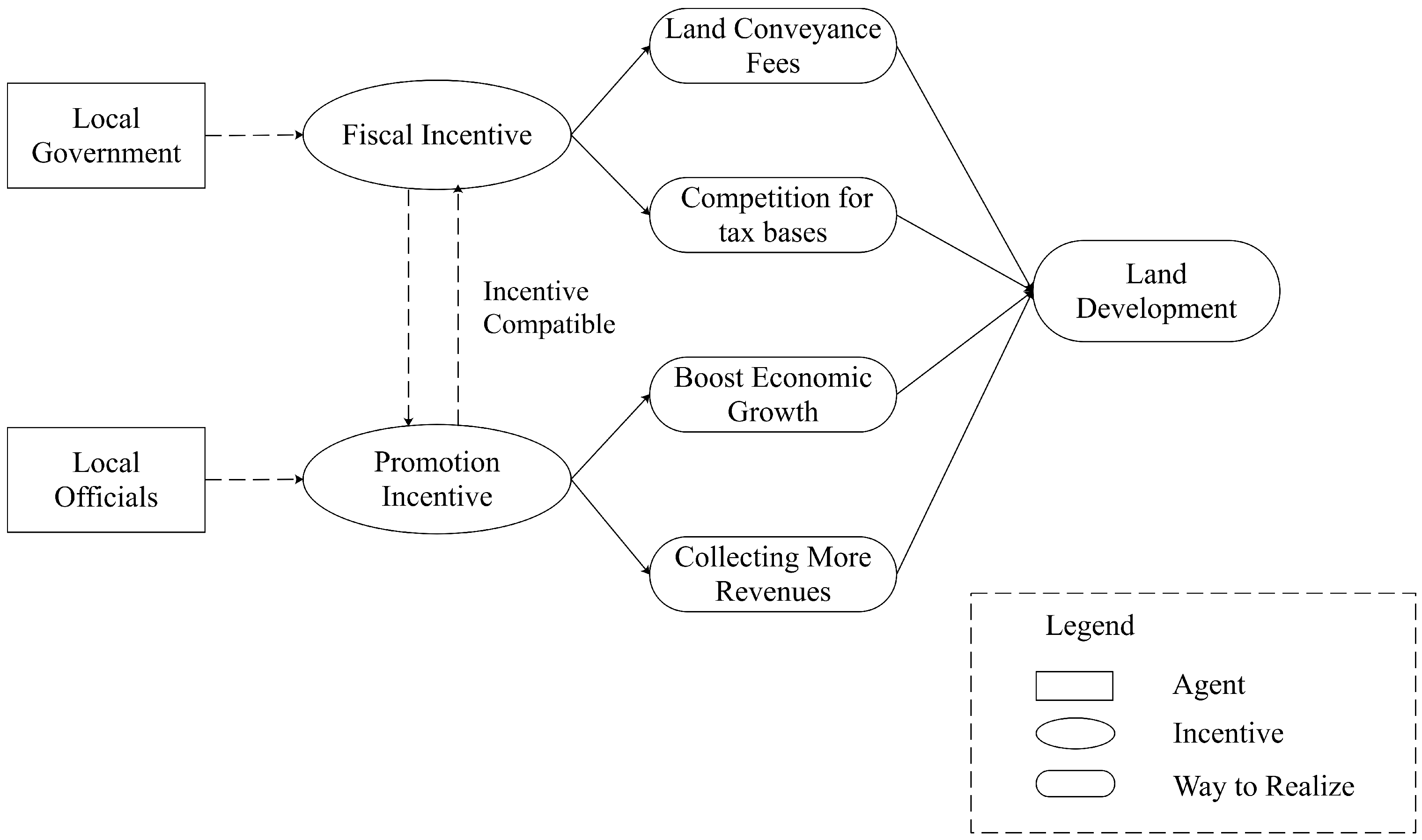

To disentangle how decentralization leads to land becoming a financial resource and growth engine, we first need to figure out the incentives rooted in local administrative levels. We summarize three critical motivations accounting for the enthusiasm of local governments on land development since the late 1990s. Distinct from most studies treating local government as a whole, we separate officials (as individuals) from government (as an organization), as shown in

Figure 1. By performing this, we explore their respective incentives and find that these incentives are compatible.

2.1. Land for Jurisdiction Competition

Since the late 1990s, local governments have paid a lot of attention toward attracting manufacturing firms to their jurisdiction. Two categories of revenues generated by manufacturing firms are attractive to local governments: The first includes value-added tax (VAT), 25% of which is retained by local governments. The second is income tax, including enterprise income tax and personal income tax paid by employees. Income tax used to be all retained at local administrative levels but shared with the central government since 2003 (only 40% of the enterprise income taxes are retained in local governments). Given that the bulk of direct revenues from manufacturing firms are extracted by the central government, another reason that motivates local government to engage in race-to-bottom competition lies in the spillover effect from manufacturing to service sectors. Once factories are placed into production, workers and managers will spend their earnings on malls, restaurants, and entertainment to activate these businesses [

14]. These activities further contribute to a growing stream of business taxes, all of which are owned by local governments.

Actually, local governments adopt various strategies to attract investments, such as direct subsidy, relaxed labor and environmental standards, favorable tax rates, and cheap industrial land. To lure footloose manufacturing firms, local governments set up a series of development zones, in which plentiful low-price land and complete infrastructure are provided. By 2006, there were 6015 development zones in China or about two for each county [

15]. We collect the supply and price of industrial land, commercial land, and residential land from 2003 to 2015. Obviously, local governments oversupply industrial land with low-price. The amount of supplied industrial land is much higher than residential and commercial land. In contrast, the price of industrial land increased at a slow pace from 469 to 760 CNY/m

CNY during 12 years, while the price of commercial and residential land skyrocketed nearly 500% (see

Figure 2). Using cheap land for jurisdiction competition effectively depressed production costs and turned China into the world’s workshop [

16].

2.2. Land for Maximizing Fiscal Revenue

With the extraordinarily low price of industrial land, local governments generally cannot earn profits from the gap between compensation to peasants and land conveyance fees from industrial land. On the contrary, local governments might bear fiscal loss in transferring industrial land. Our survey in the southern Jiangsu province shows that, at the beginning of this century, the costs of expropriating and developing land were around 200,000 CNY per Mu, while the land conveyance fees for industrial land were only 150,000 CNY per mu. In some areas, the price was even depressed to 50,000–100,000 yuan per Mu to make themselves more attractive in race-to-bottom competition [

17]. Therefore, local governments turn to residential and commercial land for reparation. Different from manufacturing firms, real estate, and service sectors are local-specific, giving local governments opportunities to raise the price of residential and commercial land. Beginning in the late 1990s, cities such as Hangzhou introduced competitive bidding for land. Real estate developers and service businessmen had no choice but to pay local governments exorbitant land conveyance fees, although the increasing land costs are passed onto buyers and consumers.

The windfalls from residential and commercial land should, to a large extent, be owed to the limited amount of land supplied by local governments. As shown in

Figure 2, there was a, respectively, small amount of commercial and residential land supplied. Limited supply and massive demand together drive the increase in land prices. Consequently, the local government reaps a bonanza from the rising land prices for commercial development. Since the early 21st century, revenues from land conveyance fees played an increasingly important role in local treasuries. The share of land revenue fluctuated around 50% during the last 10 years. This means that land has been a critical factor for local governments to maximize their fiscal revenues.

2.3. Land for Career Advancement

Politicians all over the world pursue political career advancement [

18]. China is no exception. Although Chinese official files promulgate that loyalty, capability, achievements, and other merits are criteria for the promotion of officials, specific yardsticks of career advancement still constitute a ‘black box’ [

19]. Plenty of empirical evidence has confirmed that political centralization and economic decentralization in China lead to a ‘promotion tournament’ [

20]. That is, the possibility of promotion is positively correlated with the economic performance in officials’ jurisdiction. The first critical judgment is the growth rate of GDP. With the emphasis shifting from class struggle to economic development since 1978, the CCP urges its officials to pay attention to economic growth and the enhancement of people’s living standards. Therefore, the growth rate of GDP of a jurisdiction is viewed as a representation of the capability and achievements of local officials and is intimately connected with career advancement. The second direct standard is the amount of fiscal revenues. By ‘showing the money’ to the central government, local officials not only signal more than their capability of governance but also their loyalty to the central authority, since local revenues finally determine their contribution to the central treasury [

21]. Consequently, local officials compete with each other both in economic growth and revenue collection [

22].

Coincidentally, as we mentioned above, urban land functions both in boosting economic growth and maximizing fiscal revenues. Therefore, it goes as no surprise that promotion-seeking local officials turn to land for career advancement. A series of studies have found local officials adjust strategies in land transfer, according to their goals of political promotion. For example, local officials are found to be more aggressive in transferring industrial land early in their office. In comparison, residential land is more transferred in their late stages, since the revenues generated by residential land could be reaped immediately while those of industrial land cannot be collected until two years later [

23]. Another piece of study focuses on another source of promotion incentive, i.e., age of officials, and finds that authorized officials would approve more land for construction in their critical age of career advancement [

24]. In sum, we conclude that by controlling the land development rights in their jurisdiction, local governments could use their autonomy on land for career advancement when appropriate.

3. Central Control: Central Government as Land Planner

Compared with = local governments, the objectives of the central government are more complicated. First of all, the central government needs to mobilize local governments to take their advantages on local information for economic growth, which is the main reason for decentralization. However, except for economic development, central government also pursues other goals such as protecting farmland, keeping food security, and maintaining social stability. These goals, in practice, are hard accomplish simultaneously by only using the ‘invisible hand’. Fortunately, the central government retains a variety of policy instruments to regulate the behavior of local governments (

Figure 3). Although there are other policy instruments, this paper focuses on three of them that are directly controlled by the central government: land quota, land approval, and nomenklatura.

3.1. Land Quota

China’s land system is still in the deep shadow of a planned economy, which is mainly reflected in top-down distributed land quotas. Land quotas govern the permissible conversion of land to non-agricultural uses in a region [

25]. These can be further divided into ‘overall planning quota of land conversion’ (

guihua zhibiao in Chinese, overall quota following), which is defined by Master Land Use Plan, and the ‘annual quota of land conversion’ (

jihua zhibiao, annual quota following) defined by the annual land use plans in a locality. In principle, the amount of newly developed land in a region during a, respectively, long period (usually 10–15 years) cannot exceed the total amount of overall quota. On the premise of meeting the overall quotas, annual quotas further stipulate the amount of farmland that can be converted to construction land in a single year. In other words, from the perspective of land planning, it is necessary to be in accordance with both

guihua zhibiao and

jihua zhibiao should a parcel of farmland be legally converted into non-agricultural use.

Land quotas are distributed one-level-down starting from the central government, which ensures the central government to hold the supreme authority to control the amount of land use conversion. Although the articles on official files acknowledge that the distribution of land quotas is based on ‘differentiated regional land use policy, comprehensively considering the level of economic and social development, development trend, resources and environmental conditions, land use status and potential and other factors’, other factors such as political powers also drive the land resource distribution [

6]. In view that annual quotas are generally not publicized, we collect the data of overall quotas from the Master Land Use Plan compiled by governments at central and local levels.

Figure 4 shows the spatial distribution of overall quotas among provinces during 2006–2020. For example, Zhejiang province had 940,852 hectares of construction land in 2005, while the overall quota placed a constraint on the amount of construction land, which stipulated that it should not exceed 1,132,600 hectares in 2020, suggesting there a total of 191,748 hectares of land that could be developed for construction use. On the basis of the quotas received from the central government, three steps would be taken by the Zhejiang provincial government to further decompose these 191,748 hectares of construction land quotas to its 11 prefectural level cities

3. First, according to the needs of the national and provincial key projects of transportation, irrigation, water conservancy and energy generation, some land quotas are allocated to individual prefectural-level cities. Second, construction lands for regular projects such as transportation, irrigation, and rural residential purposes were distributed to each municipal based on the municipal’s share of that land category in the province. Finally, quotas prepared for urban development are allocated to each municipal using the municipal-level urban land area, the GDP of secondary and tertiary sectors, and the predicted city-level land needs as three weighing factors [

26]. The decompositions of land quotas among municipals for Zhejiang province and its spatial distribution are shown in

Figure 4. The capital of Zhejiang province, Hangzhou, for example, receives 19,737 hectares (around 10.3%) of quotas from the provincial government. The land quota system ensures that the central government controls land development in quantity.

3.2. Land Approval

The land approval system had evolved since the reform in 1978. Before 1982, there is no requirement to obtain approval from higher-level governments for land use conversion. Communes (now township-level governments) held the authority of deciding to use agricultural land for construction. Beginning in 1982, it is necessary receive approval from higher-level governments before legally converting land from agricultural use to non-agricultural use. From 1982 to 1986, the agent undertaking the authority of land approval was the Agricultural Bureau at the county level. Since the Land Administration Law enacted in 1986, the dedicated Land Bureau was correspondingly set up. Then, the power of land approval was transferred to the Land Bureau. At the outset, this power was shared by all levels of governments higher than the county-level. The power arrangements changed again since the Land Administration Law was amended in 1998 (came into force in 1999). Since then, the power of land approval is shared by provincial governments and the central government only. Accordingly, the cases that involve the basic farmland, more than 35 hectares of farmland except for basic farmland, or more than 70 hectares of other land should be approved by the central government or, otherwise, by provincial governments.

The core intention of the land approval system is to allow high-level governments to control land conversion by giving them the authority to review land development projects. However, the local government could easily use some expedients to avoid supervision from the central government [

27]. In addition, noticing that the provincial government also has incentives similar to the local administration, it is theoretically reasonable for provincial governments to conspire with lower-level governments in land development. Provincial-level officials are found to adopt their authority of land approval to promote career advancement [

24]. Therefore, we wonder whether the power of land approval is overseen by the provincial government and to what extent the authority of land approval is reserved by the central government. Actually, around 40% of land is approved by the central government in most years (see

Figure 5). This implies that, despite the decentralization of the power on land approval, the central government still holds considerable authority on reviewing and approving land development.

3.3. Nomenklatura

With the exception for the policy instruments embedded in land systems, the personnel arrangement that is tightly controlled by the central government provides another effective method to regulate the behavior of local governments. The CCP strictly clings to the fundamental Leninist principle: ‘The Communist Party controls the cadres’ (

dang guan ganbu, in Chinese) [

28]. In such a system, the leadership of a certain hierarchy is determined by its one-level-up superior. That is, provincial leadership is appointed by the central authority, and municipal leadership is appointed by the provincial authority [

29]. Through the nomenklatura system, the central authority essentially controls the appointment, promotion, and removal of all ranking officials.

Some cases have shown that the central authority uses the nomenklatura system to achieve its goals in land management. In 2005, the State Council issued the Notice on Assessment of Provincial Government Farmland Protection, which clearly defined that the governor of a province is responsible for the protection of farmland. The provincial government further delegates this responsibility to leadership at the municipal and county levels. Officials who do not seriously perform their duties on farmland protection will face severe punishment from the central government. A recent case is from the purge of Zhao Zhengyong, the former Secretary of Shaanxi Provincial Party Committee. In his term, hundreds of villas were illegally built on agricultural land of the Qinling Mountains. The biggest villa even occupied 14.11 Mu of basic farmland. Although the central government has repeatedly stressed the need to dismantle illegally built villas, the execution by local governments in Shaanxi province was far from enough. Only by appointing the deputy secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection as the head of the inspection team stationing in Shaanxi could the central government finally dismantle all illegal villas. Due to their recalcitrance to the commands from the central government, four provincial-level officials were accused, including the former top leader of Shaanxi province, and nearly a thousand officials were investigated. Obviously, as a reserved weapon, nomenklatura provides the central government with another method to supervise local governments, especially when methods embedded in land system fail.

4. Limited Decentralization: Some Applications

Our proposal on limited decentralization could be applied to explain a range of land issues in China. Local governments’ pursuit of their goals, especially economic growth and fiscal revenues, sometimes results in serious negative externality. That is, local governments gain the benefits from their strategical land development while the detriments are dispersed to the entire society. Under such a circumstance, the central government plays a role in rectifying the distortion and chaos in land systems since negative externality generally damages their other targets. Below, we will use the formation and regulation of real estate bubble and price distortion of industrial land and its rectification as examples to illustrate the application of our theoretical framework.

4.1. Real Estate Bubble and Regulation

Over the past 20 years, China has been experiencing an unprecedented surge of housing prices. Although the skyrocketed housing prices are consequences complicated factors, such as GDP, population, inflation rate, costs of construction, interest rate, and tax policy [

30,

31,

32], it has been found that the manipulation of the local government on land supply is also an essential reason given the special land system in China [

33]. As we mentioned above, revenue-oriented local governments are supposed to undersupply residential and commercial land to reap high land conveyance fees. It is a fiscal deficit driving local governments adopt land finance strategies to increase land conveyance fees, which further causes an increase in land cost and finally leads to an increase in the total value of commodity buildings [

34]. Wang and Zhang found that the contradiction between mass housing demand and limited land supply accounts for the major proportion of the actual housing price appreciation. The increased house price, in turn, results in an increase in land price, giving a bonanza for local treasury [

35].

However, although local governments gain benefits from skyrocketed housing prices, the stability of residential property markets has become an important concern of the central government for two reasons. First, the collapse of the subprime mortgage market in the United States resulted in the most massive economic crisis experienced in that country since the Great Depression [

36]. Given its extraordinary boom and astonishing growth, many observers raised questions whether the constant increase in housing price could jeopardize the stability of China’s economy [

37,

38]. Second, the central government is afraid that the excessively high housing price might be a potential threat of social stability. The State Council claimed in 2010 that the housing issue is not only an economic issue but also an important issue that affects social stability

4. Therefore, to curb the irrational trend of house prices, the central government has issued waves of national policies and also urged local governments to regulate local real estate market since 2004 [

39]. These policies include restricted purchase, restricted loans, and even directly restricted price. The central government even commanded local governments to reasonably determine and publicize the housing price control targets in the region

5. For example, Shanghai announced that the target of real estate regulation in 2011 was to control the growth rate of house prices within 8%. The central government even adopt nomenklatura to press local governments to conscientiously regulate real estate. The leaders of cities with excessively fast housing price growth rates even might be admonished by the central government

6.

4.2. Price Distortion of Industrial Land and Rectification

Cheap industrial land has become a significant endowment for local governments to engage in race-to-bottom competition for manufacturing firms. In situations where manufacturing firms generate long-term taxes and have spillover effects on service sectors, local governments would rather depress the price of industrial land lower than its land expropriation cost to attract footloose manufacturing firms. In some cases, local governments even provide manufacturing firms with free industrial land. The transaction of industrial land between local governments and firms was frequently proceeded through private negotiation. Although the depressed price of industrial land brings considerable benefits to local governments, it also caused problems from the perspective of social welfare, such as real estate bubbles [

33], inefficient use of industrial land [

40], and even corruption [

41].

Facing the price distortion of industrial land and its detrimental consequences, the central government introduced a series of policies to rectify it. The first measure is stipulating the minimum price of industrial land. The National Industrial Land Transfer Minimum Price Standard, which was first released in 2006 and amended in 2009, divides the land of the country into fifteen grades and specifies the minimum price for each grade of land. For example, the minimum price of the first-class land is 840 yuan/m and that of the lowest class land is 60 yuan/m. The second measurement is to strictly prohibit local governments from leasing industrial land through under-desk negotiation. Instead, industrial land is required to adopt market-oriented methods to lease, that is, public tender (zhaobiao), auction (paimai), and listing of quotation (guapai). By using these methods, the price of industrial land rose from 473 yuan/m in 2006 to 760 yuan/m in 2015, implying that the policy instruments utilized by the central governments effectively contributed to the recovery of industrial land prices to its market prices.

5. The Dynamics of the Central-Local Relation: What Determines the Degree of Decentralization

The degree of decentralization is not constant over time. Now, we turn to discuss the dynamic of the central-local relationship and the determinants of the degree of decentralization. In the Mao era, the central planning system allocated land plots to land users through administration channels, which did not charge users for fees and land users had no rights to transferred land [

4]. Since the reform and opening up initiated by Deng Xiaoping in 1979, the rudiment of the current land system has gradually emerged. Even so, we could still find some critical junctures indicating significant adjustments of the central-local relationship during the last 40 years.

Figure 6 presents a part of the dynamic and some junctures. For example, at the beginning of reform, it was unnecessary to receive land approval when developing land, and communes were encouraged to boost economic growth and could independently convert land to non-agricultural use. With inefficient land use and farmland loss, this changed and land use conversion was required to be approved by higher-level governments. The land approval system became more centralized when the power of land approval was pulled back to central and provincial governments in 1998.

The question then becomes as follows: What determines the degree of decentralization? We argue that central government plays a leading role in the dynamic of central-local relations. With a series of instruments such as legislative and personnel appointment power, it is feasible for the central government to readjust the degree of decentralization, while this is not the case for local governments. Therefore, we believe that decentralization in the land system is still far from being institutionalized and lacks stability, credibility, and irreversibility. Nevertheless, although we acknowledge that the local government has an inferior status, we still note that it is more than an instrument of policy implementation. The local government has its own targets and is always proactively negotiating and bargaining with the central government. The interactions between the center and the locality are important and also lead to a change of rights definition and power distribution and, consequently, can lead to a variation of land use policies.

5.1. Leading Role of Central Government

In the model of ‘federalism, Chinese style’, the authors argued that waves of fiscal decentralization endowed the local government with the primary authority on economic issues in its jurisdiction, which further formed a credible and irreversible central-local relation in China [

10,

11,

12]. Although we agree with the considerable autonomy owned by local governments, we are suspicious of the stability, credibility, and irreversibility of decentralization, at least in terms of decentralization in land systems. Given political centralization and centralized legislative power in China, we argue that it is feasible, even though accompanied with administrative costs, for central government to reallocate the authority and responsibility between the center and locality. Monopolistic legislative power authorizes central government to promulgate and amend law, through which the rights definition and power distribution could be readjusted. For example, the amendment of the Land Administrative Law in 1998 led to the formation of a land quota system, which effectively constrained the frenetic land development by local governments. Meanwhile, tight control over personnel arrangement guarantees that there would not be a significant deviation from the orientation of the central government. Those who are recalcitrant to the central government or failed to complete the goals of central government will be pressured, punished, or even purged.

We believe it is the variation of targets of central government, which is caused by the changes in the external macro-socioeconomic environment or by changes of the top leadership, that motivates the central authority to readjust the degree of decentralization. Since the Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee, the CCP shifted its emphasis to economic construction and improving people’s living standards. The optimal choice for the party was to mobilize subnational governments to utilize their advantages on local information to boost economic growth. As a result, the authority of land development was decentralized to grassroots, including communes in the urban area and collectives in the rural area. Sufficient land supply became a critical factor for the prosperity of township and village enterprises, which contributed 30% of total industrial output in 1990 [

42]. With the separation of land ownership and use rights in 1987, local governments further utilized land use rights transfer to collect urban construction funds and stimulate development. The pattern of local state-leading urbanization caused a rapid loss of farmland from 99.5 million hm

in 1979 to 95.1 million hm

in 1995, which compelled the central government to place more attention toward protecting farmland and retaining food security. To carry out ‘the most stringent farmland protection system’, the central government amended the Land Administration Law in 1998, producing a land quota and land approval system.

Another important reason accounting for the change of targets of central government is the change in top leadership and, correspondingly, the change in governing philosophy. After the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in November 2012, the new Secretary General, Xi Jinping, came to power. Although farmland protection has been a key concern of the central government and strict policies had been formulated, the leadership with Xi at the core further emphasized the importance of ecosystem conservation, of which farmland protection is a critical part. In May 2015, Xi urged authorities to protect farmland: ‘Farmland is the country’s most valuable asset… we should protect it the way we protect pandas’. Several policies were introduced to clear up and scale up the farmland [

23]. Around 1.55 million Mu farmland was designated as permanent basic farmland, which could not be converted to other use under any circumstances. The new government further facilitates farmland transfer and consolidation to improve the usage efficiency of farmland [

43]. As for the quality of farmland, the government controlled the use of plastic, fertilizer, and pesticides. Greener agricultural development has become a vital approach in solving the country’s prominent problems on farmland pollution and degradation. Under Xi’s leadership, the central government’s emphasis on farmland protection has obviously been improved.

5.2. Initiative of Local Government

From our perspective, local governments are more likely to be the ones who take care of their interests, but their actions are supervised and constrained by the central authority. In the land system, based on the discrepancy of the targets between local governments and central government, we hold the view that local governments are neither instruments of policy implementation, nor the honeycombs creating isolation from the center [

44]. Although we argue that the central government plays a leading role in determining the degree of decentralization, we still find numerous cases in which local governments are influential in the central-local relation in the land system. It is common that local governments successfully negotiate and bargain with the central authority for more leeway. For example, the first version of the National Master Land Use Plan (2006–2020) published in October 2008 formulated that there would be 5.32 million hectares of construction land quotas for the entire country during 2006–2020. However, land quotas planned until 2020 were used up in some areas at the early beginning of the 2010s. Consequently, these local governments were forced to apply for additional quotas from the Ministry of Land Resource. With more and more areas facing empty land quotas, the central government amended the National Master Land Use Plan (2006–2020) in 2017, in which an additional 3.48 million hectares of land quotas was distributed to provinces. This evolution reflects the interaction between local and central governments: The central government initiates its plan first; in the process of implementation, local governments find that the central plan is unreasonable and negotiate with the central government. The central government finally accepts the bottom-up complaints and rectifies its previous plan.

The second case that demonstrates that the role of local government should not be overlooked is from some influential policy innovations from localities. In the late 1990s, to balance development and farmland preservation, the Zhejiang provincial government allowed its subordinates to earn land-use quotas and, more importantly, established a market for trading. More developed areas traded in land-use quotas to grow their businesses and cities, while poor areas traded out development rights for financial compensation [

26]. While keeping the total amount of farmland unchanged, such a market of land quotas effectively unlocked huge development potentials for both developed and developing regions in the province. In spite of the advantages of the ‘Zhejiang model’, the central government prohibited the transactions of land quotas among regions in June 2004. Nonetheless, the transfer of land development rights was camouflaged into other forms and was popular in other regions. For example, the boom of the ‘land tickets’ (

di piao) system in Chongqing since 2007 allowed local governments to remediate rural land for transactable land quotas. Following Chongqing, Chengdu also launched similar experiments in the transaction of land quotas. Although the central government’s attitude towards land quota transaction had been ambiguous and changeable during a decade, it eventually legalized the transaction of land development rights or land quota among regions in 2018

7.

The cases from Zhejiang and Chongqing uncover how different economic development stages among different regions affect policy shifts. As developed regions in coastal areas and inner areas, Zhejiang and Chongqing have stronger demands for construction land quotas, which prompted these provinces to take the initiative to innovate policy. Distinct from centrally managed reform, these bottom-up (spontaneous) innovations have, at a minimum, been necessary complements to central-leading reforms [

45]. Standing in the central government’s position, it could stifle, straddle, or legalize spontaneous policy innovations from a locality depending on the experimental results of the pilot project and the judgments of central government. Policy diffusion happens soon once the central government endorses policy innovations. The process of proactive innovation of local governments and reaction of central government also drives the variation of the degree of decentralization, power distribution, and consequently land use policies. For example, the innovation and legalization of land development rights transfer obviously reinforce the autonomy of local governments, while it softens the centrally imposed restriction of land quotas in an area.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper endeavors to establish a theoretical framework to understand China’s land system from the perspective of central-local relations. We argue that the discrepancy of targets between central and local governments results in ‘limited decentralization’. During the last decades, the central government decentralized the considerable autonomy of land development to local governments to encourage the latter to adopt their advantages in local information for economic growth. The local government pursues more development-oriented targets, such as collecting fiscal revenues and boosting economic growth. The incentives of local governments are compatible with that of local officials, whose career advancement to a large extent depends on the economic performance in their jurisdictions. The local government’s pursuit of economic development has rendered land an endowment for jurisdiction competition, maximizing fiscal revenues and career advancement. Land development fever directly handicaps the achievement of the central government’s other goals on land administration, especially protecting farmland and retaining food security. Therefore, the central government utilizes varieties of policy instruments (e.g., land quota, land approval, and nomenklatura system) to constrain the autonomy of local governments. This is the reason why we call decentralization a limited method.

Our proposal on limited decentralization could be applied to explain a range of land issues in China. In the framework incorporating both central and local governments, we find that the local governments’ pursuit of their goals sometimes results in serious negative externality. That is, local governments gain the benefits of their strategical land development at the cost of social welfare. Under such a circumstance, the central government plays a role in rectifying the distortion and chaos in the land system since the negative externality generally damages other targets. Two examples are provided in this paper to present the application of our theoretical framework: the formation of a real estate bubble and regulations and price distortion of industrial land and its rectification.

Actually, the central-local relation in land system is varied over time. Sometimes, local governments are endowed with more autonomy on land development, but at other times, the central government centralizes more authority to its hand. Therefore, we also attempt to reveal the determinants of the degree of decentralization. Given the fact of political centralization and centralized legislative power in China, we argue that it is feasible for central governments to reallocate the authority and responsibility between the center and locality. The variation of targets of central government, caused by the changes in the external macro-socioeconomic environment or by changes of the top leadership, motivates the central authority to readjust the degree of decentralization. Although acknowledging that the central government plays a leading role, we also find that local governments could proactively affect the degree of decentralization by negotiation and spontaneous policy innovation, creating rights definition, power distribution, and, consequently, a change in land use policies over time.

As a paper aiming to advance the understanding of China’s land system by taking advantage of the theory of central-local relations, this paper was not supposed to provide new empirical findings on land governance nor does it propose a reformative framework of redressing the current situation. Instead, we hope that this paper could be viewed as a starting point or a useful framework for further works discussing land development from political views. From this perspective, our paper calls for further in-depth research studies, especially empirical ones. First, vertical decentralization proceeds beyond relations between central and local government and also involves vertical subnational governments. As land developers, to what extent are municipal and county-level governments constrained by provincial government? Is there a local variation of the degree of decentralization within local governments? Second, although we have noticed that the degree of decentralization has changed over time and depicted its direction, we failed to quantify it. The quantitative indicators of decentralization are needed to capture the time-variant and local-variant degrees of decentralization. Finally, based on the consummation of the former two questions, quantitative studies are also needed to reveal more specific determinants of decentralization.

Author Contributions

S.L., Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, and visualization; H.W., supervision, resources, project administration, and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Major Foundation of China (15ZDA024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The 1994 Budget Law stipulates that local governments may not issue bonds unless allowed by the State Council. Therefore, local governments turn to city construction investment companies (CCIC) for raising funds. In general, the assets of CCIC come from the local treasury. Then, CCIC could borrow from banks with fiscal revenues, land as collateral. |

| 2 | Since the new president of China, Xi Jinping, came to power, farmland and ecological system protections have been receiving more and more attention. His famous saying, protecting farmland just like protecting panda (a national protected animal in China), raised the importance of farmland protection to an unprecedented height. |

| 3 | Similar steps are taken by the municipal, county, and township levels of governments. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | For example, the mayors of Haikou, Sanya, Yantai, Yichang, and Yangzhou were admonished by Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development due to the rapid growth of house price in their cities. The report could be found in http://politics.people.com.cn/n1/2018/0818/c1001-30236376.html. Accessed on 24 February 2022. |

| 7 | The State Council issued two documents named Measures of Inter-provincial Supplementary Farmland Management and Measures of Inter-provincial Transaction of Land Quotas in March 2018, both of which confirm the legality of the transaction of land development right. |

References

- Ding, C. Land policy reform in China: Assessment and prospects. Land Use Policy 2003, 20, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Ma, W. Government intervention in city development of China: A tool of land supply. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X. Land expropriation and rural conflicts in China. China Q. 2001, 166, 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. A transitional institution for the emerging land market in urban China. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1369–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Lichtenberg, E. Land and urban economic growth in China. J. Reg. Sci. 2011, 51, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wang, H. Distributive politics in China: Regional favouritism and expansion of construction land. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 1600–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, F.A. The use of knowledge in society. Am. Econ. Rev. 1945, 35, 519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Oi, J.C. Fiscal reform and the economic foundations of local state corporatism in China. World Politics 1992, 45, 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oi, J.C. The role of the local state in China’s transitional economy. China Q. 1995, 144, 1132–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montinola, G.; Qian, Y.; Weingast, B.R. Federalism, Chinese style: The political basis for economic success in China. World Politics 1995, 48, 50–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qian, Y.; Weingast, B.R. China’s transition to markets: Market-preserving federalism, Chinese style. J. Policy Reform 1996, 1, 149–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Weingast, B.R. Federalism as a commitment to reserving market incentives. J. Econ. Perspect. 1997, 11, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. Local growth coalition: The context and implications of China’s gradualist urban land reforms. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1999, 23, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Su, F.; Liu, M.; Cao, G. Land leasing and local public finance in China’s regional development: Evidence from prefecture-level cities. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 2217–2236. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.Y.R.; Wang, H.K. Dilemmas of local governance under the development zone fever in China: A case study of the Suzhou region. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 1037–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, J.; Dunaway, S. China’s rebalancing act. Financ. Dev. 2007, 44, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Lu, S. From Local Government-Led to Collaborative Governance: The Changing Role of Local Governments in Urbanization. In The Palgrave Handbook of Local Governance in Contemporary China; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 589–615. [Google Scholar]

- Tullock, G. The Politics of Bureaucracy; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- David, G. Handbook of the Politics of China; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li-An, Z. Governing China’s local officials: An analysis of promotion tournament model. Econ. Res. J. 2007, 7, 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, X.; Landry, P.F. Show me the money: Interjurisdiction political competition and fiscal extraction in China. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2014, 108, 706–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Tao, R.; Xi, L.; Li, M. Local officials’ incentives and China’s economic growth: Tournament thesis reexamined and alternative explanatory framework. China World Econ. 2012, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Tian, C.; Yin, X.; Song, Y. Political cycles and the mix of industrial and residential land leasing. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, S.; Yao, Y.; Wang, H. Testing the Relationship between Land Approval and Promotion Incentives of Provincial Top Leaders in China. J. Chin. Political Sci. 2022, 27, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, N.H.; Zhang, W. Harnessing the forces of urban expansion: The public economics of farmland development allowances. Land Econ. 2011, 87, 488–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tao, R.; Wang, L.; Su, F. Farmland preservation and land development rights trading in Zhejiang, China. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.C.; Ho, S.P. The state, land system, and land development processes in contemporary China. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2005, 95, 411–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, S.; Kirchberger, S. The Chinese nomenklatura in transition. Leadership 2000, 15, 24–917. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, H.S. Cadre personnel management in China: The nomenklatura system, 1990–1998. China Q. 2004, 179, 703–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearl, J.R. Inflation, mortgage, and housing. J. Political Econ. 1979, 87, 1115–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsatsaronis, K.; Zhu, H. What drives housing price dynamics: Cross-country evidence. BIS Q. Rev. March 2004, 3, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.B. Housing and Monetary Policy; Technical Report; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, W.; Lu, M.; Zhang, H. Housing prices raise wages: Estimating the unexpected effects of land supply regulation in China. J. Hous. Econ. 2016, 33, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.N.; Huang, J.T.; Chiang, T.F. Empirical study of the local government deficit, land finance and real estate markets in China. China Econ. Rev. 2015, 32, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q. Fundamental factors in the housing markets of China. J. Hous. Econ. 2014, 25, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Gyourko, J.; Wu, J. Land and House Price Measurement in China; Technical Report; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Anderlini, J. Chinese Property: A Lofty Ceiling. FT.com Site. 2011, Volume 13. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/6b521d4e-2196-11e1-a1d8-00144feabdc0 (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Chovanec, P. China’s Real Estate Bubble May Have Just Popped. Foreign Affairs 2011. Available online: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/asia/2011-12-18/chinas-real-estate-bubble-may-have-just-popped (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Ye, J.P.; Wu, Z.H. Urban housing policy in China in the macro-regulation period 2004–2007. Urban Policy Res. 2008, 26, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, F.; Li, Y. Key issues of land use in China and implications for policy making. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T. Corruption and local governance: The double identity of Chinese local governments in market reform. Pac. Rev. 2006, 19, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, A.G.O.; Li, X. Economic development and agricultural land loss in the Pearl River Delta, China. Habitat Int. 1999, 23, 373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M. Dragon head enterprises and the state of agribusiness in China. J. Agrar. Chang. 2017, 17, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shue, V. The Reach of the State: Sketches of the Chinese Body Politic; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Jefferson, G.H.; Singh, I. Lessons from China’s economic reform. J. Comp. Econ. 1992, 16, 201–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).