Old Sacred Trees as Memories of the Cultural Landscapes of Southern Benin (West Africa)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

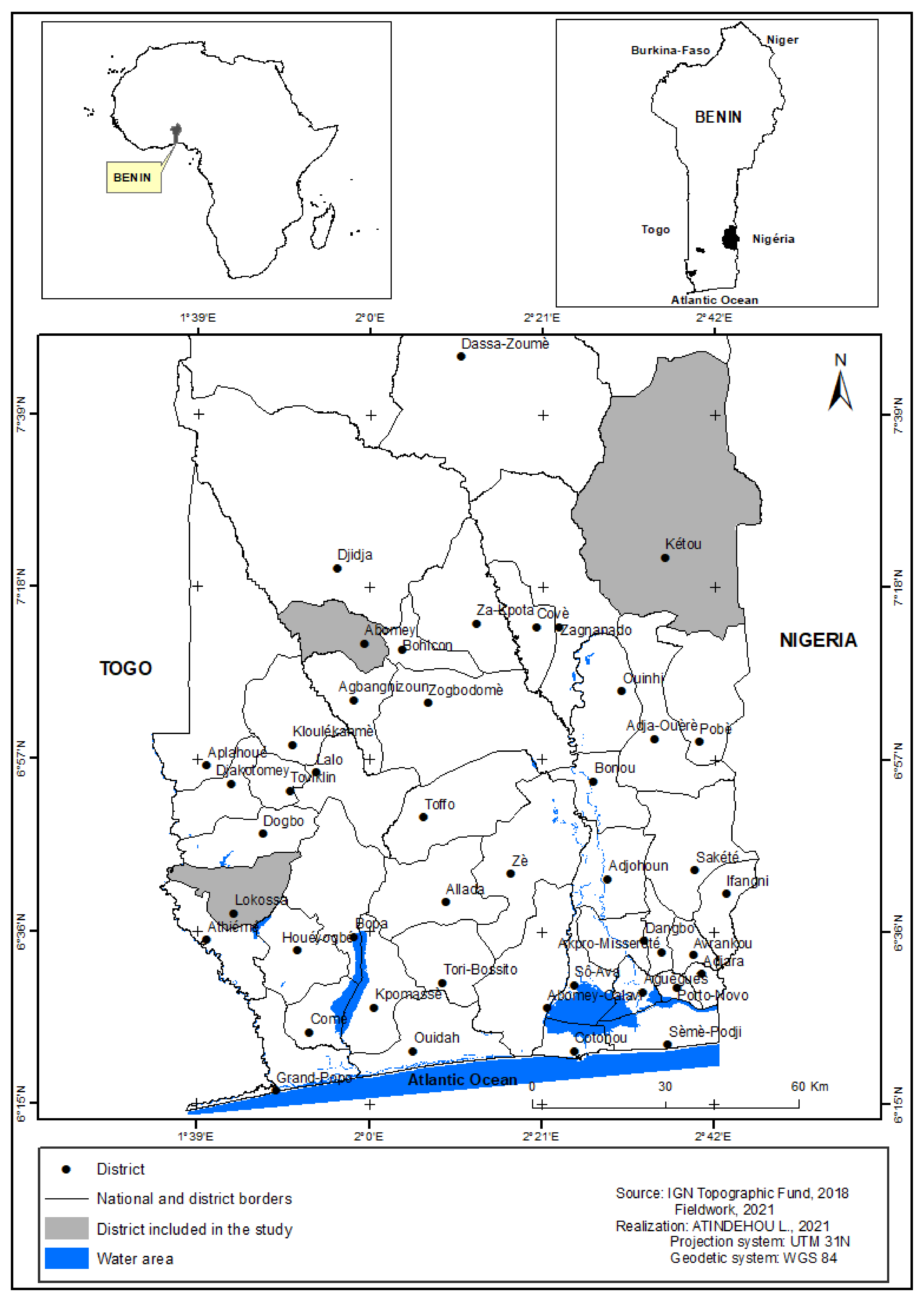

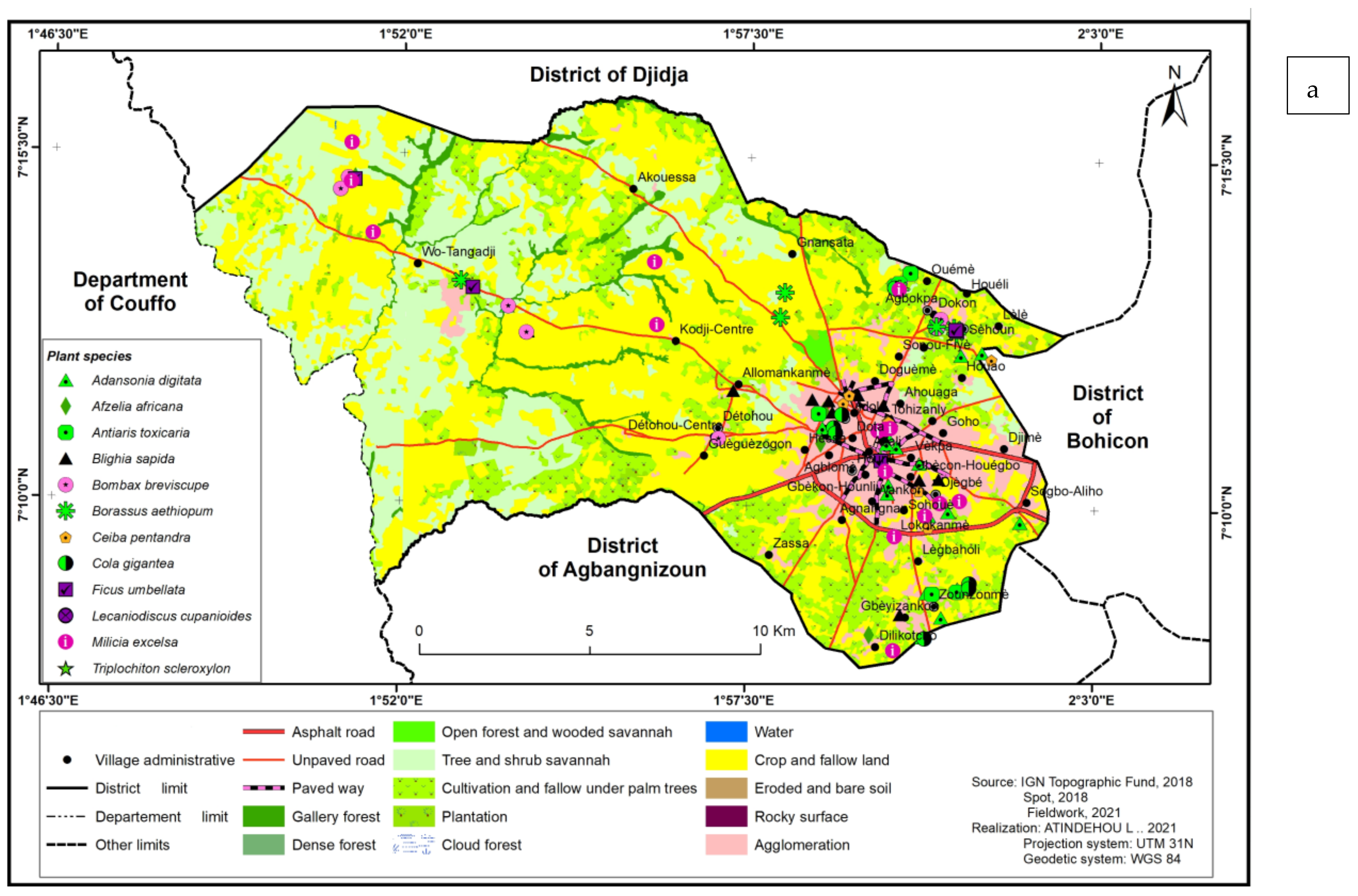

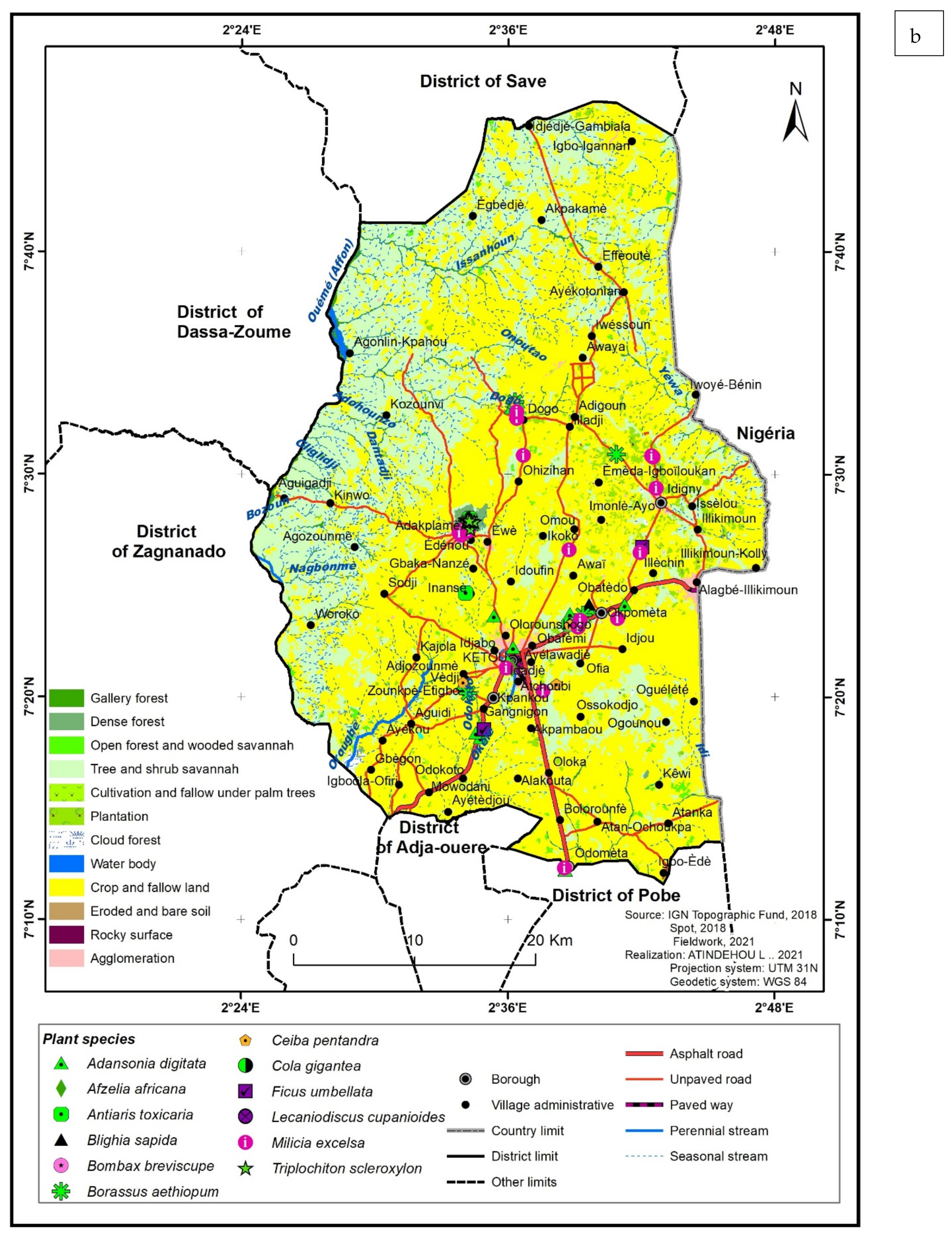

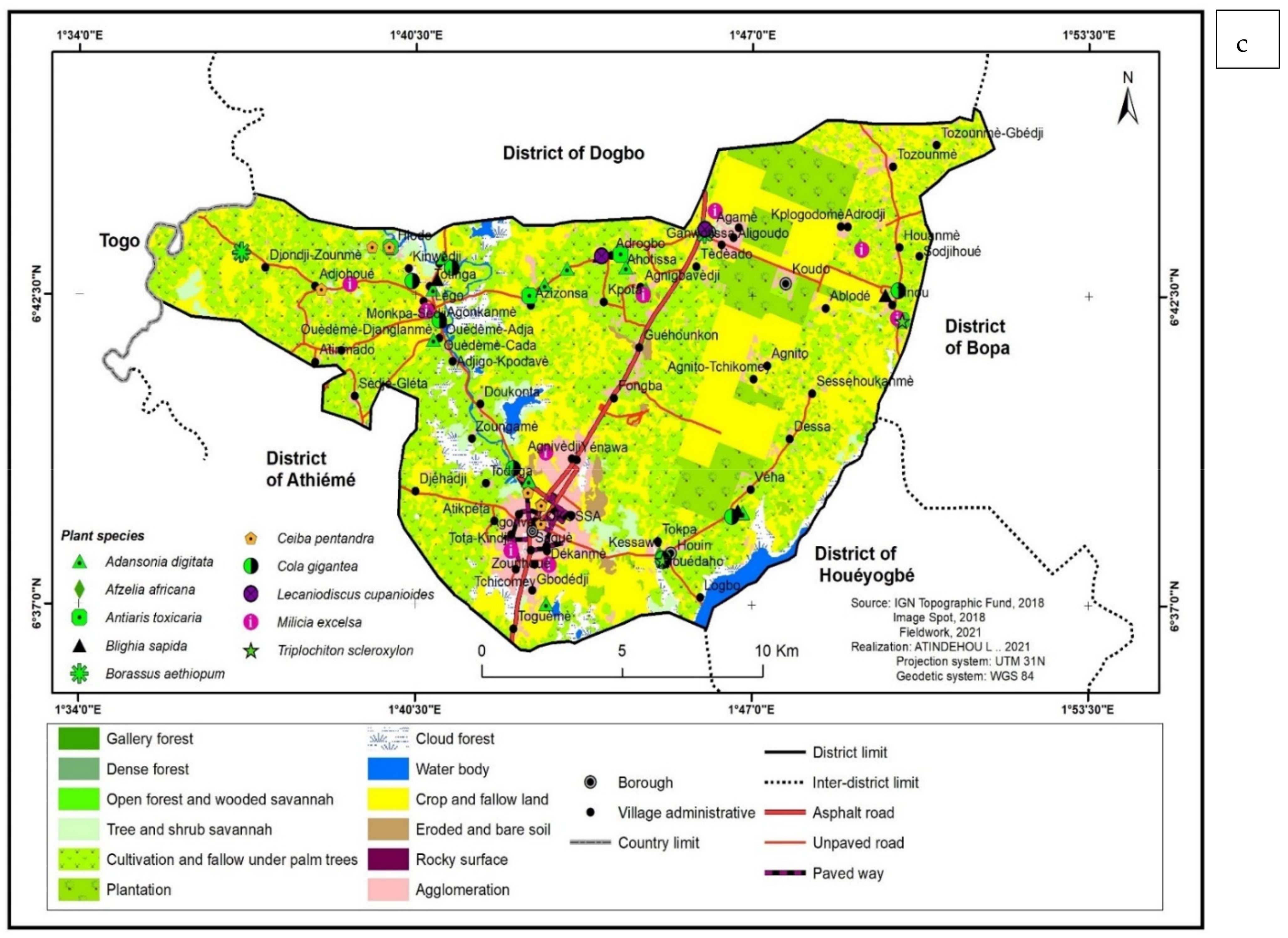

2.1. Study Area and Sites

2.2. Coordination with the Administration and Obtaining Consent of Interview Partners

2.3. Sampling Design and Data Collection

- –

- The local names of the LOTs and their meanings;

- –

- The factors that favored the conservation or threatened the existence of LOTs in terms of cultural, political, and natural events that occurred in the district;

- –

- Ethnobotanical uses (food, medicinal, handicraft, and cultural);

- –

- The dynamics of LOT populations in terms of increases or decreases in the number of tree individuals.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Definitions of Terms

2.5.1. Biological Terms

2.5.2. Social Terms

2.5.3. Terms Used to Describe the Social Context of the Sites of Large Old Trees

3. Results

3.1. Taxonomy, Life Forms, and Biogeographic Types of LOTs

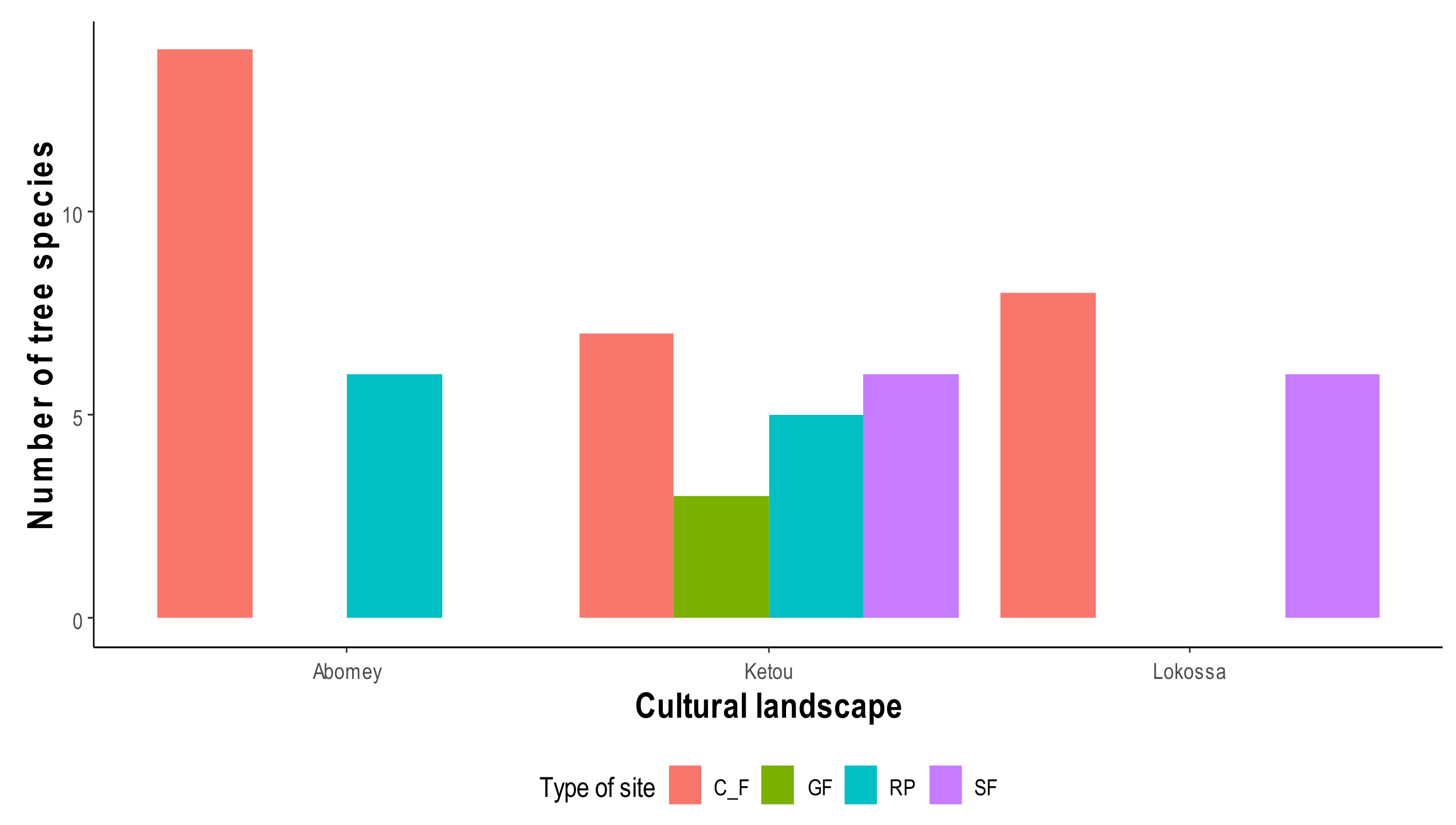

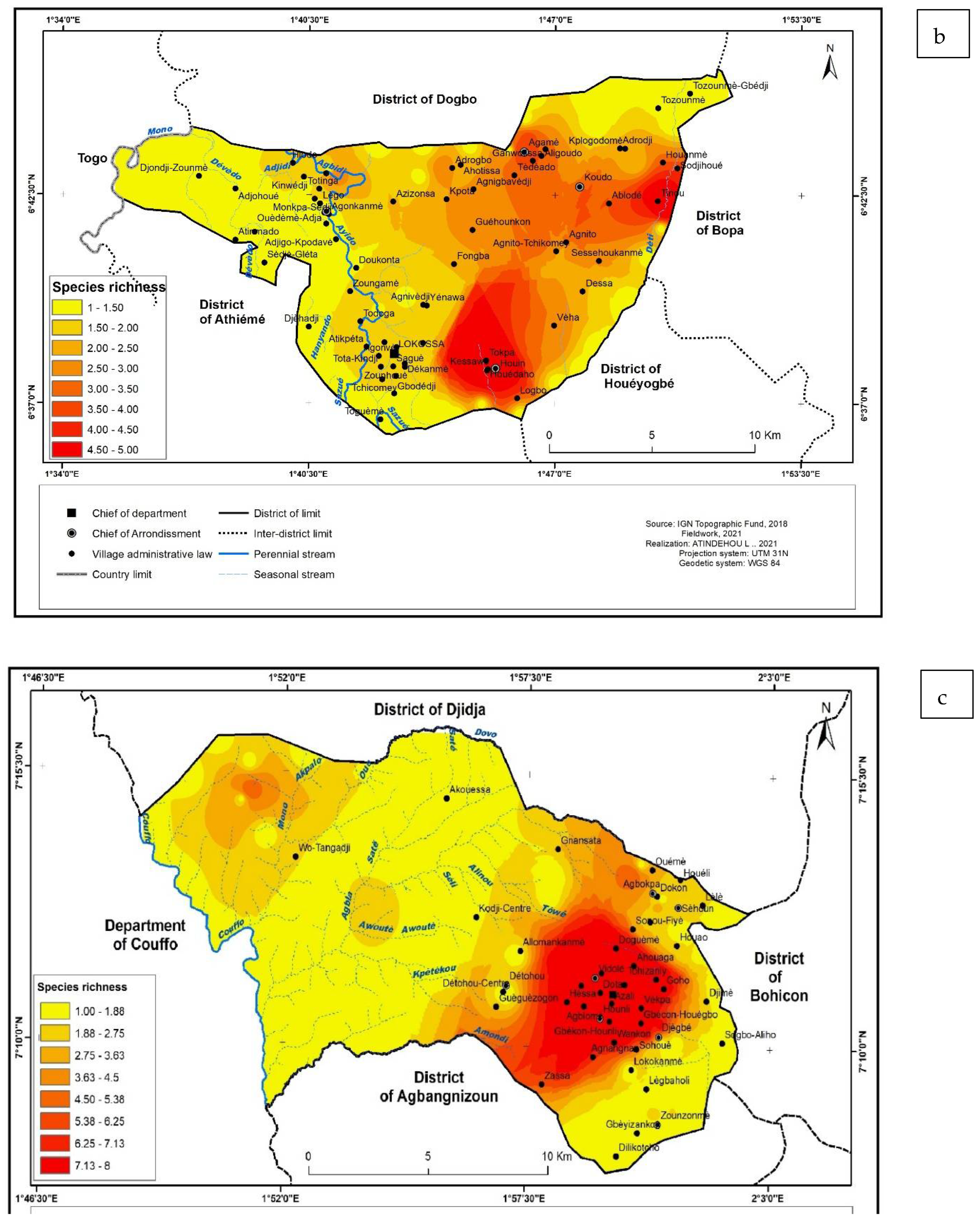

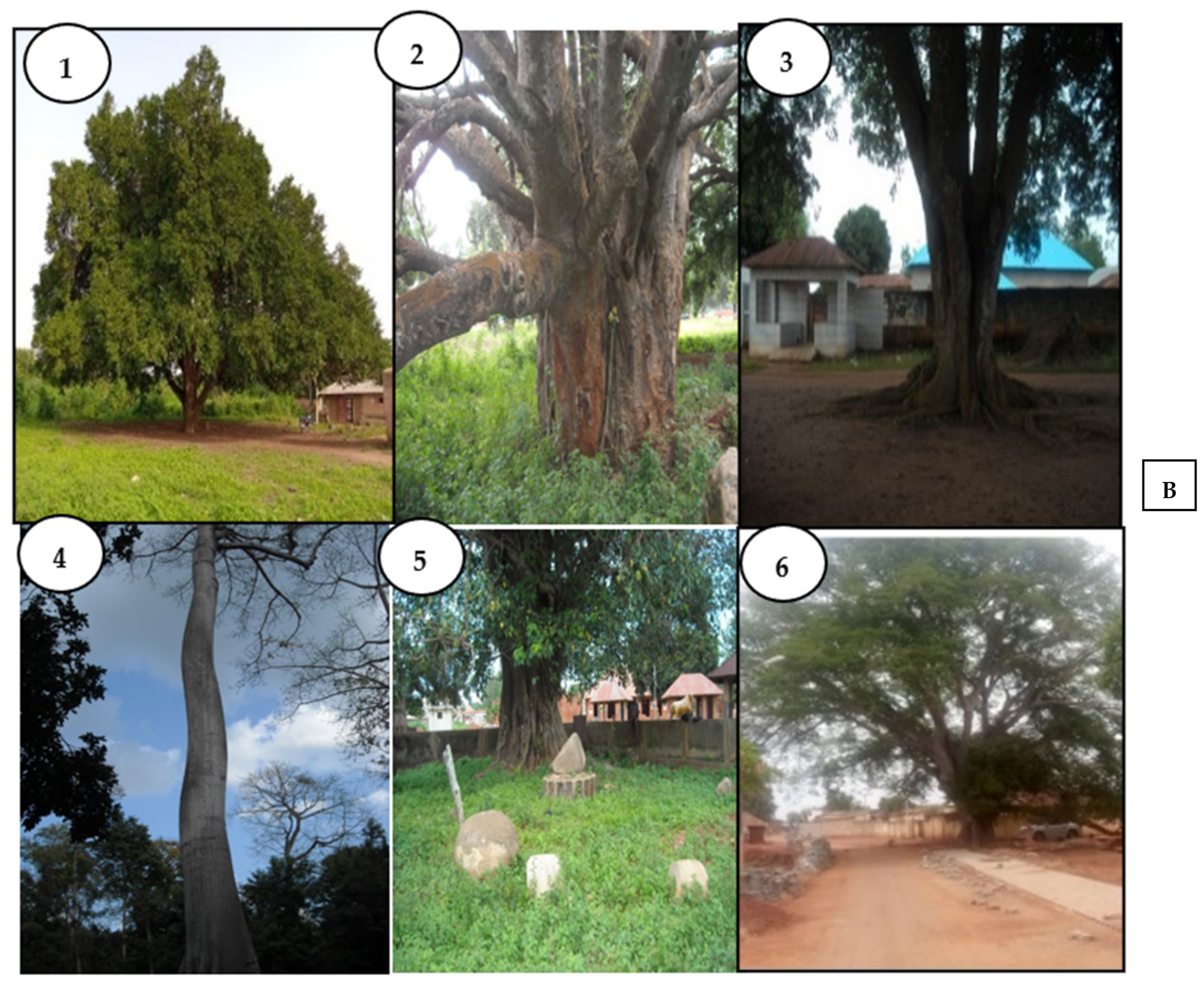

3.2. Diversity of LOT Species

3.3. Traditional Knowledge of LOTs

3.3.1. Local Taxonomy and Basis

3.3.2. Use of LOTs

3.3.3. Cultural Importance of LOTs

- –

- Axis 1 is the axis of use of A. toxicaria, M. excelsa, P. biglobosa, B. aethiopum, B. sapida, C. pentandra, L. cupanioides, A. digitata, A. africana, and R. brevicuspe (correlation coefficients > 0.5). It is formed mainly by species planted around royal palaces and princely courts, and used to delimit concessions and endogenous temple sites. On this axis, we note that good knowledge and use of A. toxicaria and M. excelsa is often associated with knowledge and use of B. sapida, C. pentandra, A. digitata, and R. brevicuspe;

- –

- Axis 2 is the axis of use of T. scleroxylon. This axis is formed by the use of T. scleroxylon, which is a sacred species;

- –

- Axis 3 is the use of F. umbellata, C. gigantea, and I. gabonensis. This axis is formed by species used for shade and for food.

| LOT Species | Axis 1 | Axis 2 | Axis3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adansonia digitata | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.04 |

| Afzelia africana | 0.62 | 0.43 | −0.26 |

| Antiaris toxicaria | 0.92 | 0.11 | 0.07 |

| Blighia sapida | 0.81 | 0.21 | 0.30 |

| Borassus aethiopum | 0.82 | −0.54 | 0.07 |

| Ceiba pentandra | 0.77 | 0.40 | 0.01 |

| Cola gigantea | −0.09 | 0.15 | 0.78 |

| Ficus umbellata | −0.02 | 0.20 | 0.90 |

| Irvingia gabonensis | −0.00 | 0.15 | 0.45 |

| Lecaniodiscus cupanoides | 0.72 | −0.59 | −0.02 |

| Milicia exelsca | 0.90 | 0.26 | 0.06 |

| Parkia biglobosa | 0.89 | −0.25 | −0.06 |

| Rhodognaphalon brevicuspe | 0.56 | −0.08 | −0.15 |

| Triplochiton scléroxylon | 0.31 | 0.70 | −0.40 |

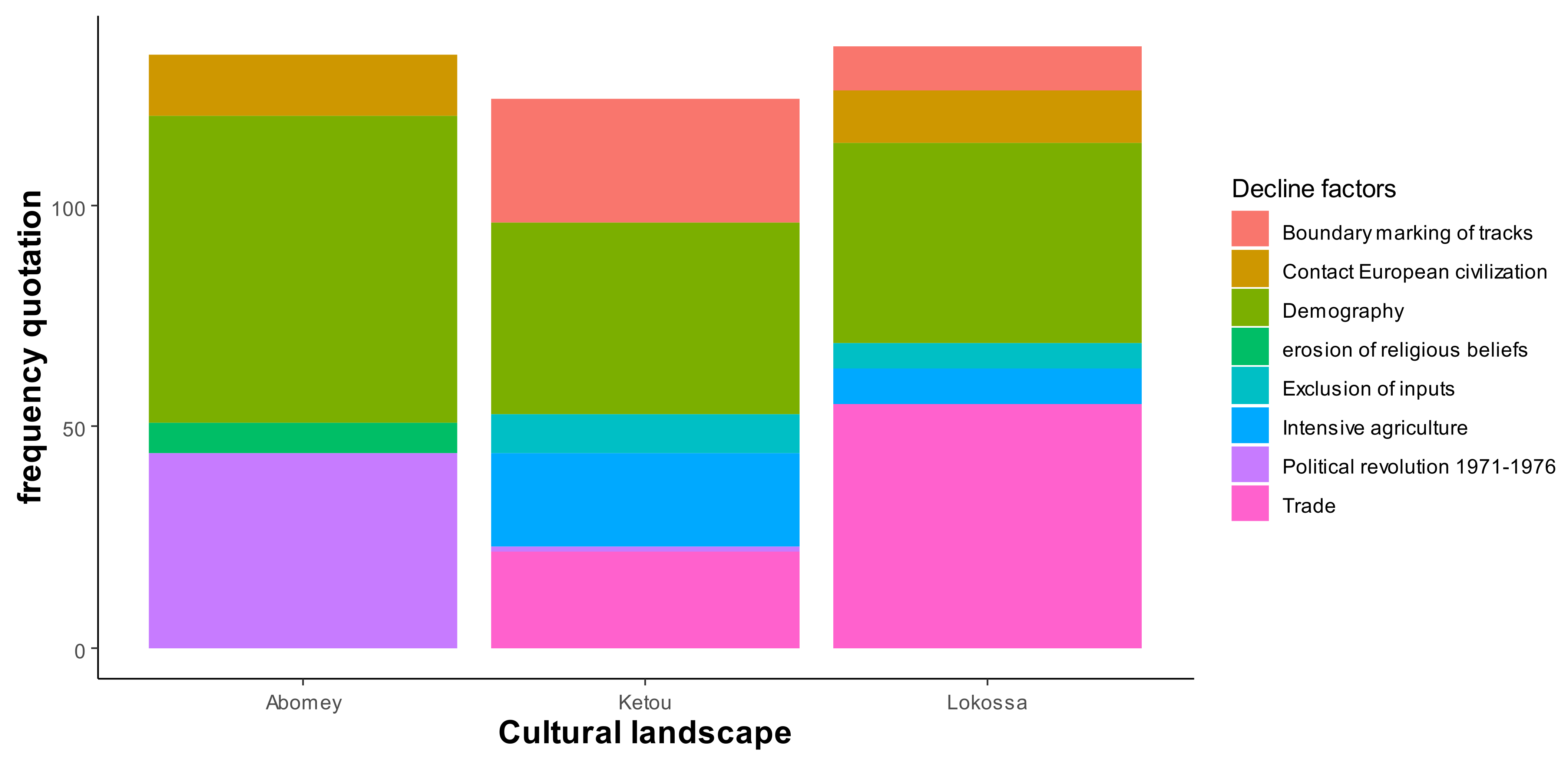

3.3.4. Population Dynamic of LOTs and Decline Factors of the Species

4. Discussion

4.1. Species Diversity, Traditional Knowledge, and Decline Factors of LOTs

4.2. Large Old Trees: Memories of Cultural Landscapes

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Charbonnier, J. In the Shadow of the Palm Trees: Time Management and Water Allocation in the Oasis of Ādam (Sultanate of Oman); Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Clavel, J.; Julliard, R.; Devictor, V. Worldwide decline of specialist species: Toward a global functional homogenization? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kunz, T.H.; Fenton, M.B. Bat Ecology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005; pp. 430–493. [Google Scholar]

- Vonhof, M.J.; Gwilliam, J.C. Intra- and interspecific patterns of day roost selection by three species of forest-dwelling bats in Southern British Columbia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 252, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Jiang, B.; Yuan, W.; Shen, A.; Yang, S.; Yao, S.; Liu, J. On the Management of Large-Diameter Trees in China’s Forests. Forests 2020, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lutz, J.A.; Furniss, T.J.; Johnson, D.J.; Davies, S.J.; Allen, D.; Alonso, A. Global importance of large-diameter trees. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018, 27, 849–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vandekerkhove, K.; Vanhellemont, M.; Vrška, T.; Meyer, P.; Tabaku, V.; Thomaes, A.; Leyman, A.; De Keersmaeker, L.; Verheyen, K. Very large trees in a lowland old-growth beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) forest: Density, size, growth and spatial patterns in comparison to reference sites in Europe. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 417, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orłowski, G.; Nowak, L. The importance of marginal habitats for the conservation of old trees in agricultural landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 79, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.J.G.; Bunce, R.G.H. Mature trees as keystone structures in Holarctic ecosystems—A quantitative species comparison in a northern English park. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2011, 4, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.B.; Laurance, W.F.; Franklin, J.F.; Likens, G.E.; Banks, S.C.; Blanchard, W.; Gibbons, P.; Ikin, K.; Blair, D.; Mcburney, L.; et al. New policies for old trees: Averting a global crisis in a keystone ecological structure. Conserv. Lett. 2014, 7, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poltz, K.; Zotz, G. Vascular Epiphytes on Isolated Pasture Trees Along a Rainfall Gradient in the Lowlands of Panama. Biotropica 2011, 43, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, B.J.; Fitzgibbon, S.I.; Wilson, R.S. Landscape and Urban Planning New urban developments that retain more remnant trees have greater bird diversity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 136, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derroire, G.; Coe, R.; Healey, J.R. Isolated trees as nuclei of regeneration in tropical pastures: Testing the importance of niche-based and landscape factors. J. Veg. Sci. 2016, 27, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Medhi, P.; Sarma, A.; Borthakur, S.K. Wild edible plants from the Dima Hasao district of Assam, India. Pleione 2014, 8, 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer, D.; Laurance, W.F. The ecology, distribution, conservation and management of large old trees. Biol. Rev. 2017, 92, 1434–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Tian, L.; Zhou, L.; Jin, C.; Qian, S.; Jim, C.Y.; Lin, D.; Zhao, L.; Minor, J.; Coggins, C.; et al. Local cultural beliefs and practices promote conservation of large old trees in an ethnic minority region in southwestern China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touré, M. Nere tree, a cultural heritage of Upper Guinea. Belgeo 2018, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Milberg, P.; Bergman, K.O.; Sancak, K.; Jansson, N. Assemblages of saproxylic beetles on large downed trunks of oak. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 1614–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cossi, A.E.; Christine, O.; Nestor, S. Facteurs déterminants de la fragmentation du bloc forêt classée-forêts sacrées au Sud-Bénin. J. Appl. Biosci. 2016, 101, 9618–9633. [Google Scholar]

- Patrut, A.; Woodborne, S.; Patrut, R.T.; Rakosy, L.; Lowy, D.A.; Hall, G.; von Reden, K.F. The demise of the largest and oldest African baobabs. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kell, S.; Qin, H.; Chen, B.; Ford-lloyd, B.; Wei, W.; Kang, D.; Maxted, N. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment China’ s crop wild relatives: Diversity for agriculture and food security. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 209, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovie, D.B.K.; Witkowski, E.T.F.; Shackleton, C.M. Knowledge of plant resource use based on location, gender and generation. Appl. Geogr. 2008, 28, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, A.S.E.; Shackleton, C.M.; Netshiluvhi, T.R.; Geach, B.S.; Ballance, A.; Fairbanks, D.H.K. Use patterns and value of savanna resources in three rural villages in South Africa. Econ. Bot. 2017, 56, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salako, K.V.; Moreira, F.; Gbedomon, R.C.; Tovissodé, F.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Glèlè Kakaï, L.R. Traditional knowledge and cultural importance of Borassus aethiopum Mart. in Benin: Interacting effects of socio- demographic attributes and multi-scale abundance. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pauchard, A.; Aguayo, M.; Peña, E.; Urrutia, R. Multiple effects of urbanization on the biodiversity of developing countries: The case of a fast-growing metropolitan area (Concepción, Chile). Biol. Conserv. 2006, 127, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehinnou Koutchika, R.; Chougrou, D.; Agbani, P.; Sinsin, B. Étude de la diversité floristique par strates de quelques bois sacrés du Centre Bénin. J. Appl. Biosci. 2013, 69, 5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djagoun, C.A.M.S.; Zanvo, S.; Padonou, E.A.; Sogbohossou, E.; Sinsin, B. Perceptions of ecosystem services: A comparison between sacred and non-sacred forests in central Benin (West Africa). For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 503, 119791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjakpa, B.J.; Ahoton, E.L.; Weesie, D.M.W.; Akpo, L.E.; Chidikofan, D.M.G.F.; Hounssinou, A.R.S.A. Exploitation, commercialisation et consommation du bois de feu dans les zones humides du Sud-Bénin: Cas de la Commune de Sô-Ava. Clim. Et Développement 2009, 8, 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Juhé-beaulaton, D. Le vodou au cœur des processus de création et de patrimonialisation au Bénin. Afr. E Mediterr. 2009, 67, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Adomou, A.C. Vegetation Patterns and Environmental Gradients in Benin: Implications for Biogeography and Conservation; Wageningen University and Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- INSAE. Que Retenir des Effectifs de Population en 2013? Direction des Etudes Démographiques; INSAE/Ministère du Développement, de l’Analyse Economique et de la Prospective: Cotonou, Benin, 2013; 33p. [Google Scholar]

- Dagnelie, P. Statistique Théorique et Appliquée. Tome 2. Inférence Statistique à Une et à Deux Dimensions; De Boeck & Larcier sa: Paris, France; Bruxelles, Belgium, 1998; pp. 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Frontier, S.; Pichod-Viale, D. Ecosystèmes: Structure-Fonctionnement-Evolution; Masson: Paris, France, 1993; 447p. [Google Scholar]

- Jim, C.Y.; Zhang, H. Species diversity and spatial differentiation of old-valuable trees in urban Hong Kong. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindt, R.; Coe, R. Tree Diversity Analysis: A Manual and Software for Common Statistical Methods for Ecological and Biodiversity Studies; World Agroforestry Centre: Nairobi, Kenya, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Raunkiaer, C. The life forms of plants and statistical plant geography; being the collected papers of C. Raunkiaer. In The Life Forms of Plants and Statistical Plant Geography; Being the Collected Papers of C. Raunkiaer; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- White, F. The Vegetation of Africa. Nat. Resour. Res. UNESCO 1983, 20, 356. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, O.; Gentry, A.H. The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru: II. Additional hypothesis testing in quantitative ethnobotany. Econ. Bot. 1993, 47, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossato, S.C.; De LeitãO-Filho, H.F.; Begossi, A. Ethnobotany of caiçaras of the Atlantic Forest coast (Brazil). Econ. Bot. 1999, 53, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua Zambrana, N.Y.; Bussmann, R.W.; Hart, R.E.; Moya Huanca, A.L.; Ortiz Soria, G.; Ortiz Vaca, M.; Ortiz Álvarez, D.; Soria Morán, J.; Soria Morán, M.; Chávez, S.; et al. Traditional knowledge hiding in plain sight—Twenty-first century ethnobotany of the Chácobo in Beni, Bolivia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maranise, A.M.J. Investigating the syncretism of Catholicism and voodoo in New Orlean. J. Religion Soc. 2012, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Juhé-Beaulaton, D.; Roussel, B. A propos de l’historicité des forêts sacrées de l’ancienne Côte des Esclaves. In Plantes et Paysages d’Afrique, une Histoire à Explorer; Chastanet, M., Ed.; Karthala: Paris, France, 1998; pp. 353–382. [Google Scholar]

- Pazzi, R. Eléments de cosmologie et d’anthropologie Evé, Adja, Gen, Fon. In Annales de l’Université du Bénin; Université du Bénin: Lomé, Togo, 1979; pp. 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Ying, P.; Jim, C.Y. Landscape and Urban Planning Species diversity and spatial pattern of old and precious trees in Macau. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 162, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Yang, W.; Ren, Y.; Campbell, M.J.; Wu, C.; Luo, Y.; Zhong, L.; Yu, M. Diversity and density patterns of large old trees in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amontcha, A.A.M.; Djego, J.G.; Lougbegnon, T.O.; Sinsin, B.A. Typologie et répartition des espaces verts publics dans le grand Nokoué (Sud Bénin). Eur. Sci. J. 2017, 13, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. Ambient Air Pollution: A Global Assessment of Exposure and Burden of Disease; WHO Document Production Services: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; 131p. [Google Scholar]

- Avoce, C.; Sinsin, B.; Ade, A. Sustainable use of non-timber forest products: Impact of fruit harvesting on Pentadesma butyracea regeneration and financial analysis of its products trade in Benin. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 257, 1930–1938. [Google Scholar]

- Dibs, H.; Hussain, T.H. Estimation and Mapping the Rubber Trees Growth Distribution using Multi Sensor Imagery With Remote Sensing and GIS Analysis. J. Univ. Babylon Pure Appl. Sci. 2018, 26, 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Plieninger, T.; Draux, H.; Fagerholm, N.; Bieling, C.; Bürgi, M.; Kizos, T.; Kuemmerle, T.; Primdahl, J.; Verburg, P.H. The driving forces of landscape change in Europe: A systematic review of the evidence. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Engelbrecht, F.; Adegoke, J.; Bopape, M.-J.; Naidoo, M.; Garland, R.; Thatcher, M.; McGregor, J.; Katzfey, J.; Werner, M.; Ichoku, C.; et al. Projections of rapidly rising surface temperatures over Africa under low mitigation. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 085004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blicharska, M. Incorporating Social and Cultural Significance of Large Old Trees in Conservation Policy. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 1558–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartena, D. Styles of Making a Living and Ecological Change on the Fon and Adja Plateaux in South Bénin, ca. 1600–1990; Wageningen University and Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Karl, A. Traditions Orales au Dahomey-Bénin; Centre Régional de Documentation Pour la Tradition Orale: Niamey, Niger, 1974; 420p. [Google Scholar]

- Savadogo, S.; Ouedraogo, A. Diversité et enjeux de conservation des bois sacrés en société Mossi (Burkina Faso) face aux mutations socioculturelles actuelles. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2011, 5, 1639–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Cultural Landscape | Variables | Categories | Number of Individuals | Relative Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abomey | Gender | Women | 17 | 34 |

| Men | 33 | 66 | ||

| Age | 60 ≤ i ≤ 80 | 45 | 90 | |

| More than 80 years | 05 | 10 | ||

| Ethnicity | Fon | 50 | 100 | |

| Religion | Christian | 10 | 20 | |

| Animists | 40 | 80 | ||

| Social and economic category | Farmer | 14 | 28 | |

| Craftsman | 13 | 27 | ||

| Commercial | 7 | 14 | ||

| Community leader | 8 | 15 | ||

| Traditional therapist | 8 | 16 | ||

| Ketou | Gender | Women | 6 | 12 |

| Men | 44 | 88 | ||

| Age | 60 ≤ i ≤ 80 | 48 | 96 | |

| More than 80 years | 2 | 4 | ||

| Ethnicity | Ilè-ifè | 3 | 6 | |

| Mahi | 26 | 52 | ||

| Nago | 21 | 42 | ||

| Social and economic category | Farmers | 30 | 60 | |

| Craftsman | 9 | 18 | ||

| Commercial | 3 | 6 | ||

| Community leaders | 4 | 8 | ||

| Traditional therapist | 4 | 8 | ||

| Religion | Christian | 25 | 50 | |

| Animists | 24 | 48 | ||

| Muslim | 1 | 2 | ||

| Lokossa | Gender | Women | 6 | 12 |

| Men | 44 | 88 | ||

| Age | 60 ≤ i ≤ 80 | 42 | 84 | |

| More than 80 years | 8 | 16 | ||

| Ethnicity | Adja | 17 | 34 | |

| Kotafon | 33 | 66 | ||

| Social and economic category | Farmers | 12 | 24 | |

| Craftsman | 12 | 24 | ||

| Community leaders | 16 | 32 | ||

| Traditional therapist | 10 | 20 | ||

| Religion | Christian | 11 | 22 | |

| Animists | 39 | 78 |

| Species | Family | Life Form | Chorology | Tree Count | Tree Count (%) | c P d | d P L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ficus umbellata Vahl | Moraceae | mPh | SG | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Lecaniodiscus cupanioïdes Planch. | Sapindaceae | mPh | Pal | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Irvingia gabonensis Baill | Irvingiaceae | MPh | AT | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Parkia biglobosa (Jacq.) R. Br. | Fabaceae | mPh | SG | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Afzelia africana Smith ex Pers. | Fabaceae | mPh | AT | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Cola gigantea A. Chev. | Sterculiaceae | mPh | SG | 10 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Rhodognaphalon brevicuspe Sprague | Malvaceae | MPh | GC | 11 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Borassus aethiopum Mart. | Arecaceae | mPh | AT | 15 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| Triplochiton scleroxylon K. Schum. | Sterculiaceae | MPh | GC | 18 | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| Antiaris toxicaria Engl. | Moraceae | MPh | Pal | 20 | 7 | 3 | 2 |

| Blighia sapida K. D. Koenig | Sapindaceae | mPh | Pal | 25 | 9 | 3 | 3 |

| Ceiba pentandra L. Gaertn. | Malvaceae | MPh | Pan | 37 | 14 | 3 | 2 |

| Milicia excelsa (Welw.) C. C. Berg | Moraceae | MPh | AT | 47 | 17 | 3 | 3 |

| Adansonia digitata L. | Malvaceae | mPh | AM | 70 | 25 | 3 | 4 |

| LOT Species | Diameter (cm) | Height (m) | bAge m (Years) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Min | Max | ||

| Adansonia digitata | 57 | 373 | 5.22 | 30.55 | 133.23 ± 48.17 |

| Milicia excelsa | 100 | 262 | 16.33 | 36.98 | 132.13 ± 47.28 |

| Ceiba pentandra | 101 | 248 | 16.64 | 62.62 | 132.90 ± 46.99 |

| Parkia biglobosa | 91 | 91 | 12.88 | 12.88 | 123.18 ± 33.77 |

| Blighia sapida | 87 | 192 | 8.7 | 29.82 | 130.82 ± 46.43 |

| Antiaris toxicaria | 32 | 229 | 21.45 | 48.14 | 120.84 ± 31.82 |

| Triplochiton scleroxylon | 91 | 231 | 15.04 | 62.4 | 122.60 ± 20.39 |

| Cola gigantea | 106 | 283 | 15.04 | 21.96 | 122.74 ± 33.69 |

| Ficus umbellata | 56 | 126 | 13.92 | 13.92 | 190 |

| Lecaniodiscus cupanioïdes | 195 | 201 | 25.46 | 34.44 | 141.66 ± 20.41 |

| Irvingia gabonensis | 278 | 380 | 12.23 | 15.30 | 119.74 ± 44.64 |

| Afzelia africana | 92 | 132 | 11.85 | 17.11 | 121.29 ± 32.82 |

| Rhodhognaphalon brevicuspe | 56 | 126 | 13.86 | 26.65 | 117.21 ± 18.52 |

| District | Area (km2) | Density of Human Population (hbts/km2) | Nb. Observ. (Trees) | Species Richness | Species Richness (Mean ± SD) | Shannon’s Index | Pielou Evenness |

| Abomey | 142.1 | 641.3 | 93 | 11 | 4.5 ± 3.5 | 0.74 | 0.62 |

| Ketou | 1792.6 | 87.8 | 109 | 12 | 3.5 ± 2 | 0.75 | 0.66 |

| Lokossa | 300.3 | 349.52 | 68 | 10 | 3.5 ± 2.5 | 0.62 | 0.49 |

| District | Total Species Richness/100 km2 | Nb Observ./100 km2 | Shannon’s Index/100 km2 | Shannon’s Index (Mean ± SD) | Pielou Evenness/100 km2 | Pielou Evenness (Mean ± SD) | |

| Abomey | 8.44 | 65.44 | 0.52 | 0.42 ± 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.35 ± 0.31 | |

| Ketou | 1 | 6.10 | 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.37 | |

| Lokossa | 3.33 | 22.65 | 0.20 | 0.27 ± 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.21 ± 0.24 | |

| LOT Species | Vernacular Names | Meanings | Used Parts | Uses Category | Status/IUCN | Status Benin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adansonia digitata | Kpassa a, azizon b Lagba c, Otché oriri d | Tree embodying strength and wealth a Tree that restores energy b Tree of abundance d | Leaf, root, bark, fruit | Food, med, cult, handicraft | LC | LC |

| Milicia excelsa | Loko a,b,c,e, Iroko d | Majestic tree a,b,c,e Sacred tree d | Bark, fruit, stem (Lumber product) | Med, cult, handicraft | VU | EN |

| Ceiba pentandra | Gueédéhountin a,b,e, Houtchin c, Aagou d,f | Tree of Guede divinity a,b,c Thorn tree d f | Stem (lumber product) | Med, cult, handicraft | LC | LC |

| Irvingia gabonensis | Assrotin a | - | Fruit | Food, med, cult, handicraft | NT | NT |

| Blighia sapida | Lissètin a, Agnissètin b,c, Esinsin e, Ishin d,f | Tree with red and sweet fruit a Tree of peace for the kingdom e Tree that bears fruit by opening d,f Tree of the Oro fetish ritual d,f Tree embodying the Gu divinity a,b,c | Fruit | Food, cult | LC | LC |

| Antiaris toxicaria | Guhotin a,b,e, Gbéhortin c, Ooro d,f | Tree used for ritual of the Oro fetish d,f Tree embodying the Gu divinity a,b,c | Stem (lumber and energy) | Cult, handicraft | LC | NT |

| Ficus umbellata. | Vunvuntin a,b, Odan d | Tree with large shade a Palaver tree for meetings d | - | Cult | LC | LC |

| Parkia biglobosa | Ahwatin a,b, Ayi d | - | Bark, fruit | Food, cult, handicraft | LC | LC |

| Rhodognanphalon brevicuspe | Kpatin-dehuntin a, Huntchin b,c | Tree to delimit fences | Bark, stem (lumber and energy) | Cult, handicraft | VU | LC |

| Triplochiton scleroxylon | Ewetin e, Arere d | Sacred tree e Tree of Oro ritual d | Bark, stem (lumber and energy) | Cult, handicraft | LC | EN |

| Lecaniodiscus cupanioides | Ganhotin a,b, Ganhotchin c | - | Bark, lumber | Cult, handicraft | LC | LC |

| Afzelia africana. | Kpakpatin a, Aïran d | - | Bark, stem (lumber) | Cult, handicraft | VU | EN |

| Cola gigantea | Golotin a | Tree of protection a | Fruit | Food | LC | LC |

| Borassus aethiopum | Gbégontin a | - | Fruit, leaf | Food, handicraft, med | LC | VU |

| Species | Use Value | Reported Use by Organ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∑ UR | UV | ∑ UR | UV | |

| Cola gigantea | 2 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 |

| Ficus umbellata | 2 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 |

| Lecaniodiscus cupanioïdes | 2 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 |

| Triplochiton scleroxylon | 3 | 0.02 | 3 | 0.02 |

| Parkia biglobosa | 4 | 0.03 | 2 | 0.01 |

| Rhodognaphalon brevicuspe | 5 | 0.03 | 3 | 0.02 |

| Irvingia gabonensis | 6 | 0.04 | 5 | 0.03 |

| Afzelia africana | 11 | 0.07 | 4 | 0.03 |

| Antiaris toxicaria | 11 | 0.07 | 8 | 0.05 |

| Blighia sapida | 18 | 0.12 | 10 | 0.07 |

| Ceiba pentandra | 27 | 0.18 | 6 | 0.04 |

| Milicia excelsa | 72 | 0.48 | 7 | 0.05 |

| Adansonia digitata | 103 | 0.69 | 10 | 0.07 |

| LOTs | PU | Associated Cultural Practices/Medicinal Uses | FRC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceiba pentandra | Thorn | Search for 16 thorns and keep them with you to protect you from evil spirits. | 0.66 |

| Leaf | Drink a glass of the decoction to reduce a high fever. | 1.33 | |

| Milicia excelsa | Leaf | Drink the decoction to treat the spleen. | 1.33 |

| Sap | Put on the head of babies to close a fontanelle. | 1.33 | |

| Stem | For the collection of sacrifices. | 2 | |

| Blighia sapida | Fruit | Dry, crush, and use as soap. | 2.16 |

| Triplochiton scleroxylon | Stem | Wrapped in a white cloth, is used to prepare for the release of the deity Oro. | 2.66 |

| Root | Drink half a glass a day of the decoction for the improvement of visual acuity. | 4.66 | |

| Adansonia digitata | Leaf | Triturate + honey, macerate for 7 days, and drink a glass (3 times a day): Strengthens male fertility. | 7.33 |

| Root | To be combined with other species to fight against evil spirits. | 11..33 | |

| Bark | Drink a glass (twice a day) of the infusion for the treatment of malaria. | 53.33 |

| Species | Cultural Values and Associated Totems | Utilities |

|---|---|---|

| Adansonia digitata | Shelter of the cult of the divinity “Tôhwiyô” Tree marked by the presence of fetish temple |

|

| Antiaris toxicaria | Sacred tree for the followers of the deity “Toxôsù” The tree is surrounded by a white cloth |

|

| Ceiba pentandra | Sacred tree for the followers of the deity “Dan” Tree marked by the presence of an altar for the divinity | Place of ritual to ask the deity for protection, prosperity, and wealth |

| Milicia excelsa | Sacred tree for the followers of the Oro cult Tree with specific markings and present in or near the convents |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Atindehou, M.M.L.; Avakoudjo, H.G.G.; Idohou, R.; Azihou, F.A.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Adomou, A.C.; Sinsin, B. Old Sacred Trees as Memories of the Cultural Landscapes of Southern Benin (West Africa). Land 2022, 11, 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11040478

Atindehou MML, Avakoudjo HGG, Idohou R, Azihou FA, Assogbadjo AE, Adomou AC, Sinsin B. Old Sacred Trees as Memories of the Cultural Landscapes of Southern Benin (West Africa). Land. 2022; 11(4):478. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11040478

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtindehou, Massogblé M. Lucrèce, Hospice G. Gracias Avakoudjo, Rodrigue Idohou, Fortuné Akomian Azihou, Achille Ephrem Assogbadjo, Aristide Cossi Adomou, and Brice Sinsin. 2022. "Old Sacred Trees as Memories of the Cultural Landscapes of Southern Benin (West Africa)" Land 11, no. 4: 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11040478

APA StyleAtindehou, M. M. L., Avakoudjo, H. G. G., Idohou, R., Azihou, F. A., Assogbadjo, A. E., Adomou, A. C., & Sinsin, B. (2022). Old Sacred Trees as Memories of the Cultural Landscapes of Southern Benin (West Africa). Land, 11(4), 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11040478