A Study on Policy and Institutional Arrangements for Urban Green Space Development in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Need of Urban Green Space in Ulaanbaatar City

1.2. History of Urban Planning and Green Space Development in Ulaanbaatar City

2. Methodology

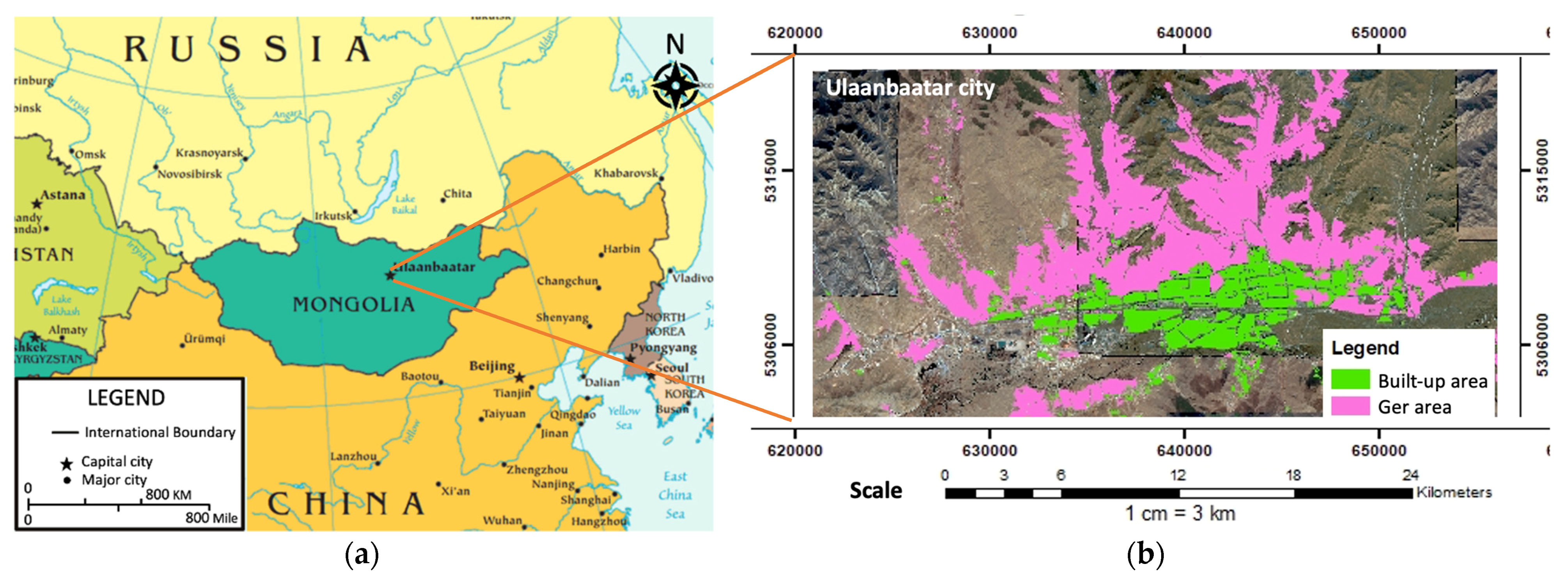

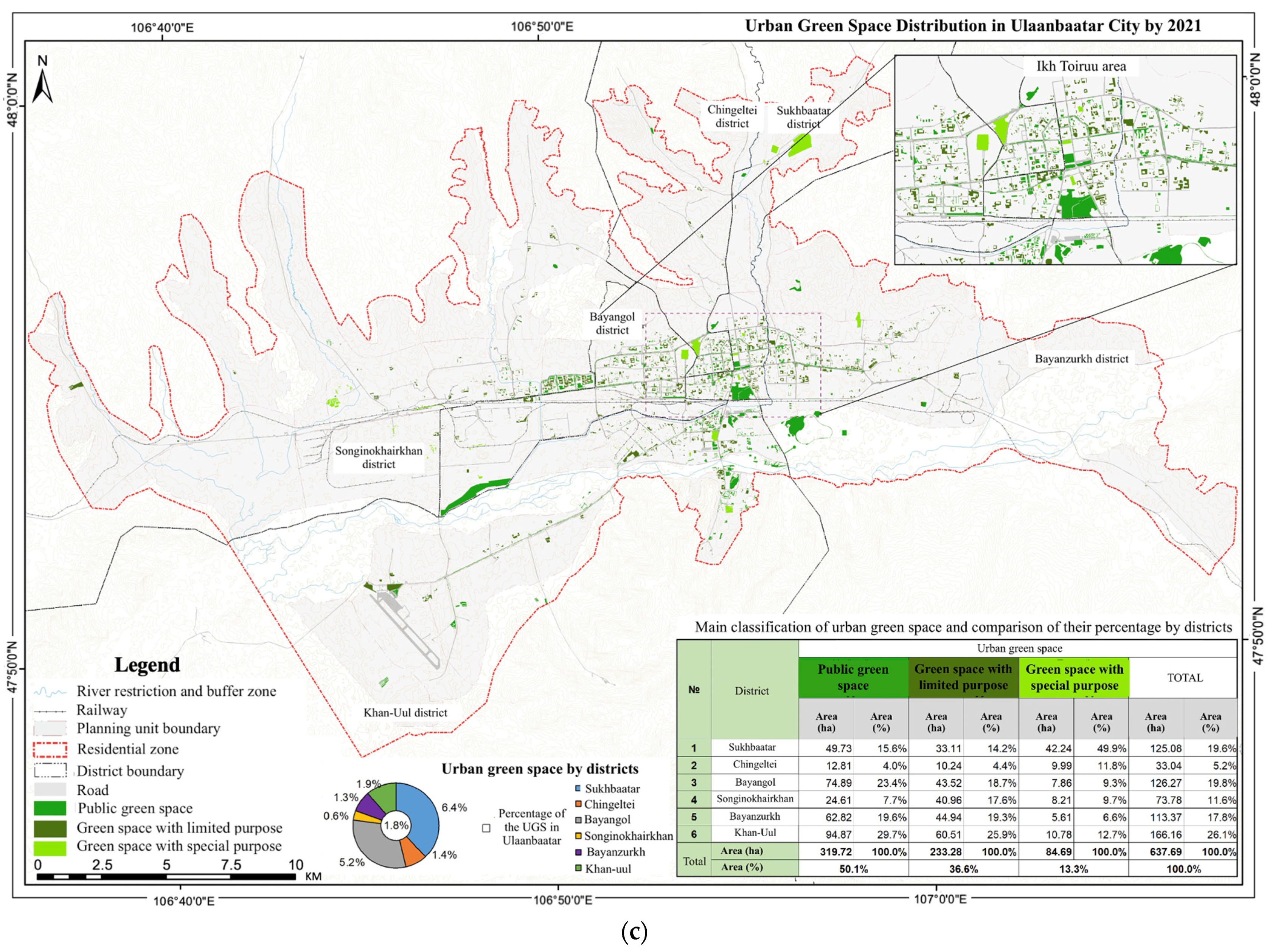

Study Area

3. Results

3.1. Importance of Urban Green Space in Policy Documents

3.1.1. Laws and Regulations

3.1.2. Urban Development Plans for Green Space

3.1.3. Green and Sustainable Development Policies

3.2. Relevant Actions Recognized in Action Plans

3.3. Institutional Arrangement for Urban Green Space Policy Implementation

3.4. Financial Feasibility

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mincey, S.K.; Hutten, M.; Fischer, B.C.; Evans, T.P.; Stewart, S.I.; Vogt, J.M. Structuring institutional analysis for urban ecosystems: A key to sustainable urban forest management. Urban Ecosyst. 2013, 16, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, C.; Threlfall, C.G.; Livesley, S.J.; Kendal, D.; Fuller, R.A.; Davern, M.; van der Ree, R.; Hochuli, D.F. Decision-making of municipal urban forest managers through the lens of governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 104, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanath, J. The Relationship between Public Green Spaces and Population in a City. 2022. Available online: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/relationship-between-public-green-spaces/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Byrne, J.; Sipe, N. Green and open space planning for urban consolidation—A review of the literature and best practice. In Issues Paper; Griffith University: Brisbane, Australia, 2010; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Rupprecht, C.D.D.; Byrne, J.A. Informal urban greenspace: A typology and trilingual systematic review of its role for urban residents and trends in the literature. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biernacka, M.; Kronenberg, J. Classification of institutional barriers affecting the availability, accessibility and attractiveness of urban green spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 36, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, S.M.A. Urban Green Spaces and an Integrative Approach to Sustainable Environment. J. Environ. Prot. 2011, 2, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, A.; Chan, E. Institutional factors affecting urban green space provision–from a local government revenue perspective. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 2313–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; van den Bosch, C.C.K.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhu, L.; Chen, J.; Lin, Y.; Dong, J. China’s Green space system planning: Development, experiences, and characteristics. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 60, 127017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshetu, S.B.; Yeshitela, K.; Sieber, S. Urban green space planning, policy implementation, and challenges: The case of Addis Ababa. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelan, E.; Girma, Y. Urban green infrastructure accessibility for the achievement of SDG 11 in rapidly urbanizing cities of Ethiopia. GeoJournal 2021, 87, 2883–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Halik, Ü.; Abliz, A.; Mamat, Z.; Welp, M. Urban green space accessibility and distribution equity in an arid oasis city: Urumqi, China. Forests 2020, 11, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. The State of the World’s Cities 2006/7; Warah, R., Ed.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2006; p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- Mayor’s Office. Ulaanbaatar City Mayor Office’s Working Plan for 2017–2020 Plan; Mayor’s Office: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 2017. (In Mongolian) [Google Scholar]

- Russo, A.; Cirella, G.T. Modern compact cities: How much greenery do we need? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Byambaa, E. A Study on Public Green Space Accessibility; Mongolian University of Science and Technology: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 2018; Available online: http://catalog.must.edu.mn/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=78372 (accessed on 21 November 2022). (In Mongolian)

- Bodikhand, B. A Study on Urban Green Space Zoning in Ulaanbaatar City; Mongolian University of Science and Technology: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 2013; Available online: http://catalog.must.edu.mn/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=76694 (accessed on 21 November 2022). (In Mongolian)

- Badrakh, C. The Basis of Dendrology, Small-scale Landscape and Urban Green Space, 2nd ed.; Chultem, D., Ch, S., Eds.; Admon Publishing: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Batsuuri, G. Public Feedback for the Draft of General Development Plan of Ulaanbaatar City until 2040; Youtube Official Channel of Ulaanbaatar 2040: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- City Governor’s Office. Action Plan for Ulaanbaatar 2020 Master Plan and Development Approaches for 2030 Plan. City Governor’s Office: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 2016. Available online: https://www.gazar.gov.mn/p/546-109 (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Galdnaa, M. Study on the Violation of Norm of Urban Planning in Ulaanbaatar City, Mongolia. University of Tsukuba: Ibaraki, Japan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mongolian Government. Vision-2050: Long-Term Development Policy of Mongolia. 2019. Available online: https://www.legalinfo.mn/annex/details/11057?lawid=15406 (accessed on 17 March 2022). (In Mongolian).

- Urban Planning and Research Institute. Second General Development Plan of Ulaanbaatar City Plan. 2021. Available online: https://ulaanbaatar2040.mn/p/34/xoyordugaar-eronxii-tolovlogoo-1961-1976-on (accessed on 21 March 2022). (In Mongolian).

- Urban Planning and Research Institute. Third General Development Plan of Ulaanbaatar City Plan. 2021. Available online: https://ulaanbaatar2040.mn/p/35/guravdugaar-eronxii-tolovlogoo-1976-1986-on (accessed on 21 March 2022). (In Mongolian).

- Byambadorj, T.; Amati, M.; Ruming, K.J. Twenty-first century nomadic city: Ger districts and barriers to the implementation of the Ulaanbaatar City master plan. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2011, 52, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Planning and Research Institute. Fifth General Development Plan of Ulaanbaatar City Plan. 2021. Available online: https://ulaanbaatar2040.mn/p/37/tavdugaar-eronxii-tolovlogoo-2002-2013-on (accessed on 21 March 2022). (In Mongolian).

- Chakma, K.; Matsui, K. Responding to climate-induced displacement in Bangladesh: A governance perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, N. Mainstreaming climate change adaptation in least developed countries in South and Southeast Asia. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2013, 18, 825–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Construction and Urban Development. Urban Planning and Construction Norms and Rules (No.30.01.04). 2004. Available online: https://www.barilga.mn/bk/118/?fbclid=IwAR3BI0YH-g3nnNktdo3DUKJQVWp6tpoL5TLsG2JFvVLYvwtaMLxY1onoais (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Urban Planning and Research Institute. Ulaanbaatar 2020 Master Plan and Development Approaches 2030 Plan. 2021. Available online: https://ulaanbaatar2040.mn/p/38/ulaanbaatar-xotyg-2020-on-xurtel-xogzuulex-eronxii-tolovlogoo-nii-todotgol-2030-ony-xogzliin-cig-xandlaga (accessed on 21 November 2022). (In Mongolian).

- Ulaanbaatar Planning and Designing Institute. Explanatory Document of UB General Development Plan Concept for 2040. 2019. Available online: https://home.uda.ub.gov.mn/?p=8593 (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Agency of Urban Development. Status of Implementation of the Ulaanbaatar 2020 Master Plan and Development Approaches for 2030. 2020. Available online: https://home.uda.ub.gov.mn/?p=7637 (accessed on 27 March 2022).

- Urban Planning and Research Institute. General Development Plan of Ulaanbaatar City Until 2040. Plan. 2021. Available online: https://ulaanbaatar2040.mn/p/159/xogzliin-eronxii-tolovlogoo (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Municipality of Ulaanbaatar. Green Development Strategic Action Plan for Ulaanbaatar 2020. Municipality of Ulaanbaatar. 2015. Available online: https://1oj61m3rln3bdse82pw7b343-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Green-Development-Strategic-Action-Plan-2020.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2022).

- Repealed Legal Act: Green Development Policy, Pub. L. No. 89. 2021. Available online: https://legalinfo.mn/mn/detail/10482 (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Mongolian Parliament. Sustainable Development Concept 2030. 2016. Available online: http://nda.gov.mn/backend/f/PtNQFjbNQ6.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Dalai, S.; Dambaravjaa, O.; Purevjav, G. Water Challenges in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. In Urban Drought. Disaster Risk Reduction; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Municipality of Ulaanbaatar. Green City Action Plan for Ulaanbaatar City (Issue November). 2019. Available online: https://www.ebrdgreencities.com/assets/Uploads/PDF/8be8318df3/Ulaanbaatar-GCAP_Eng.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Asian Development Bank. Mongolia: Ulaanbaatar Green Affordable Housing and Resilient Urban Renewal Sector Project. 2019. Available online: https://www.adb.org/projects/49169-002/main (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Resolution for Ratifying the Implementing Measures for “Billion Tree” National Movement, Pub. L. No. 380, 4. 2021. Available online: https://legalinfo.mn/mn/detail?lawId=16389636287911&showType=1 (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Brandli, L.L.; Salvia, A.L.; da Rocha, V.T.; Mazutti, J.; Reginatto, G. The Role of Green Areas in University Campuses: Contribution to SDG 4 and SDG 15. In World Sustainability Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chankseliani, M.; McCowan, T. Higher education and the Sustainable Development Goals. High. Educ. 2021, 81, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayor’s Office. Department of Urban Landscape and Horticulture. In Official Website.; 2014. Available online: https://ubservice.ub.gov.mn/?page_id=2254 (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Municipality of Ulaanbaatar. City Governors. 2022. Available online: https://ulaanbaatar.mn/about/#MAP (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- National Statistics Office. Numbers, Structure and Changes of Civil Servants in Mongolia (1995–2017). 2017. Available online: https://esan.mn/p/research/politics-and-the-public/mongol-ulsyn-toerijn-alban-haagchdyn-too-buetec-oeoerchloelt-2017 (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- Statistics Department of Ulaanbaatar. Ulaanbaatar City Budget Expenditure 2013–2016. 2020. Available online: http://ubstat.mn/StatTable.aspx?tableID=387 (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Swanwick, C.; Dunnett, N.; Woolley, H. Nature, Role and Value of Green Space in Towns and Cities: An Overview. Built Environ. 2003, 29, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, M.A.V.D.; Mudu, P.; Uscila, V.; Barrdahl, M.; Kulinkina, A.; Staatsen, B.; Swart, W.; Kruize, H.; Zurlyte, I.; Egorov, A. Development of an urban green space indicator and the public health rationale. Scand. J. Public Health 2016, 44, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, C.S.; Suklje Erjavec, I.; Mathey, J. Green spaces—A key resources for urban sustainability: The GreenKeys approach for developing green spaces. Urban Izziv 2008, 19, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiu, D.L.; Iojă, C.I.; Pătroescu, M.; Breuste, J.; Artmann, M.; Niță, M.R.; Grădinaru, S.R.; Hossu, C.A.; Onose, D.A. Is urban green space per capita a valuable target to achieve cities’ sustainability goals? Romania as a case study. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 70, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, J. Why not to green a city? Institutional barriers to preserving urban ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 12, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Municipality of Ulaanbaatar. Mongolia: Ulaanbaatar Urban Services and Ger Areas Development Investment Program. 2015. Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-documents/45007/45007-005-pfrr.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

| Documents Reviewed | Year of Release |

|---|---|

| Law on Land | 2002 |

| Urban Planning and Construction Norms and Rules /БНбД 31-01-04/ | 2004 |

| Law on Urban Development | 2008 |

| Ulaanbaatar 2020 Master Plan and Development Approaches for 2030 | 2013 |

| Green Development Policy | 2014 |

| Sustainable Development Concept of Mongolia | 2016 |

| Action Plan for Ulaanbaatar 2020 Master Plan and Development Approaches for 2030 | 2016 |

| Ulaanbaatar City Mayor Office’s Working Plan for 2017–2020 | 2016 |

| Green City Action Plan | 2019 |

| Vision 2050 | 2020 |

| General Development Plan of Ulaanbaatar City for 2040 | (under draft) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Enkhbold, B.; Matsui, K. A Study on Policy and Institutional Arrangements for Urban Green Space Development in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. Land 2022, 11, 2205. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11122205

Enkhbold B, Matsui K. A Study on Policy and Institutional Arrangements for Urban Green Space Development in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. Land. 2022; 11(12):2205. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11122205

Chicago/Turabian StyleEnkhbold, Bayarmaa, and Kenichi Matsui. 2022. "A Study on Policy and Institutional Arrangements for Urban Green Space Development in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia" Land 11, no. 12: 2205. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11122205