Unlocking Romania’s Forest-Based Bioeconomy Potential: Knowledge-Action-Gaps and the Way Forward

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- What are the challenges that Romanian forests/forestry face when it comes to transitioning to a sustainable bioeconomy?

- -

- What would a sustainable circular-bioeconomy entail for Romanian forests and forestry?

- -

- How do we get there by the year 2030?

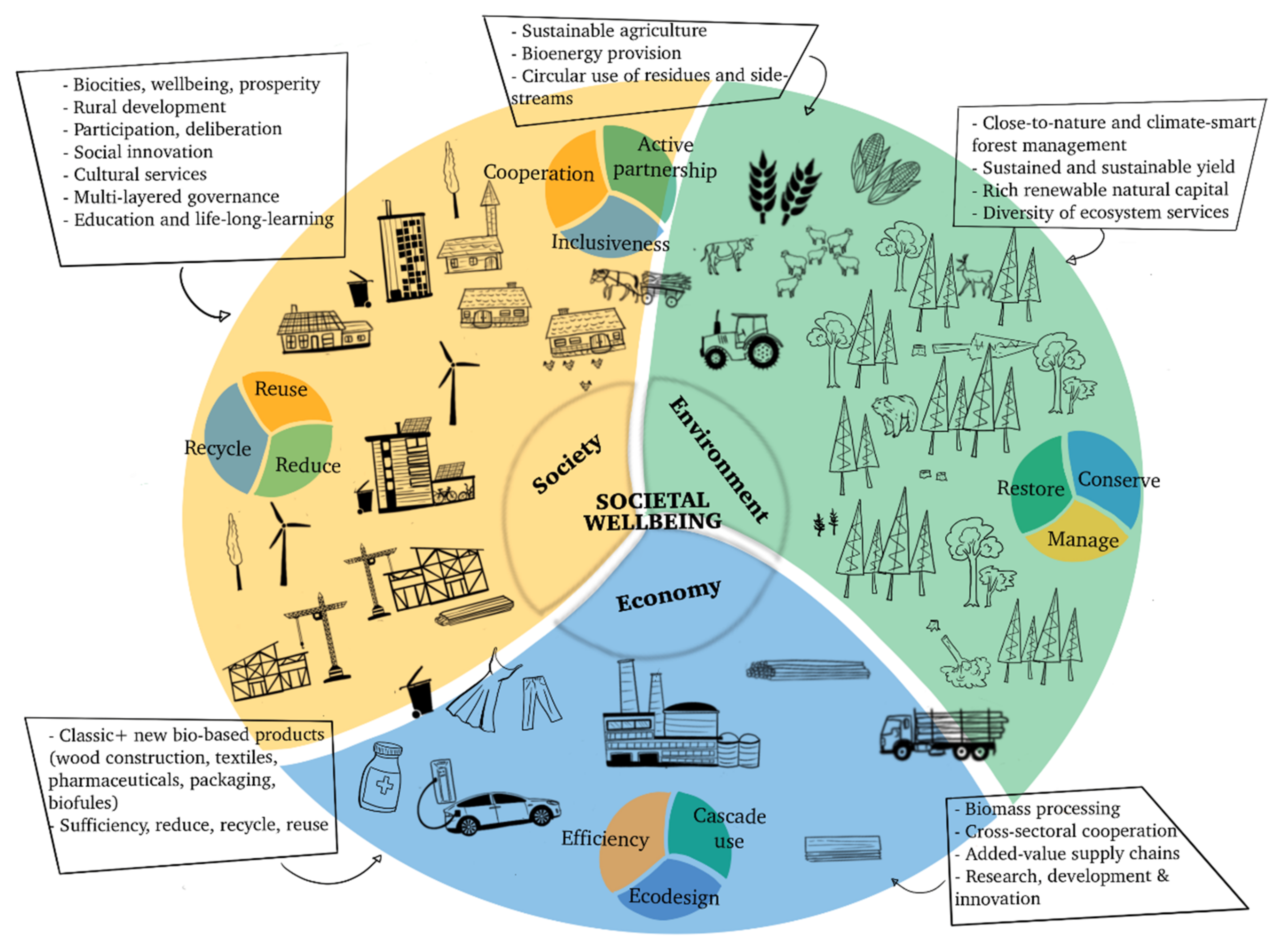

2. Conceptual Underpinnings

3. Study Design

3.1. Foresight Exercises

- i.

- Diagnosing the past and current situation in order to gain an understanding of the present state of affairs;

- ii.

- Exploring possible alternative futures;

- iii.

- Choosing a preferable or desirable future scenario where the experts would prefer the future to be directed;

- iv.

- Identifying concrete actions to achieve the preferred future.

3.2. Expert Selection

- activity within the forest-based sector, or other related sectors working closely with the forest-based sector and/or using wood-based raw materials or products;

- relevant job title or job description both in national and international context;

- relevant publications or academic contributions on the topic;

- membership in bioeconomy-relevant boards, committees, working groups, or technology clusters.

3.3. Workshop Facilitation and Qualitative Content Analysis

4. Main Insights

4.1. Romania’s Forests and Forestry: Past and Present Diagnosis

4.1.1. Forestland and Forest Management

4.1.2. Policy and Governance

4.1.3. Data and Metrics

4.1.4. Innovation and Trade

4.1.5. Cooperation

4.1.6. Education

4.1.7. Communication

4.2. Top-Down and Bottom-Up Initiatives to Support the Forest Bioeconomy

4.3. The Way Forward

- i.

- Romania potentially has the forest biomass and know-how prerequisites needed to enable a bioeconomy strategy built around the forest sector. However, important knowledge and policy gaps, as well as conflicting information related to the availability of forest biomass, carbon storage, biodiversity status, ecosystem services, or governance arrangements still persist. There is an urgent need for addressing these action-knowledge gaps before making projections about the future possibilities of a circular forest bioeconomy.

- ii.

- A circular (forest) bioeconomy of wellbeing must focus on regional and rural development. A national bioeconomy strategy must also acknowledge the country’s distinct socio-ecological configuration. The national forest-bioeconomy must both include traditional wood use, as well as new wood-based products. Close cooperation with communities and concerned stakeholders must continue being at the center of these developments, both for fostering nature conservation and for continuing to provide much-needed services (e.g., bioenergy provision for rural households). In consequence, innovations must not necessarily come from high-tech technologies and bio-refining facilities, but build on local know-how and inclusive social innovation.

- iii.

- The transition to a forest-based bioeconomy needs investments in forests, forest infrastructure, and labor force. The potential of Romanian forests for providing timber for long-lived products, for example in buildings and furniture, is limited by the poor forest road infrastructure, the outdated forest harvesting equipment, the lack of wood warehouses for timber valuation. The implementation of cascading principles also needs a strategic development of the infrastructure required for the recycling of timber-based products. At the same time, a stronger emphasis on economic instruments is needed as an alternative to the command-and-control instruments. This involves setting clear compensation schemes for biodiversity conservation, setting payments for ecosystem services, and creating financial programs to support forest owners for the implementation of responsible forest management.

4.4. Limitations and Outlook

5. Conclusions

- -

- Adequate funding for sustainable forest management at all ownership levels (and especially for private ownership and community forests);

- -

- Offering incentives/financial support for local communities and local businesses;

- -

- Minimizing bureaucracy so that local small business can access EU funding more easily;

- -

- Incentivizing cooperation between different stakeholders, especially between the forest-based sector and other industries;

- -

- Continuous investment in research, development, education and training.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Workshop Participants

| Workshop 1 | Gender | Group | Affiliation | Expertise | Country |

| F | Academia | Forestry Faculty in Romania (a) | Forest governance, forest education, women in forestry | Romania | |

| M | Academia | Forestry Faculty in Romania (b) | Sustainable forest management certification, chain of custody certification | Romania | |

| M | Academia | Forestry Faculty in Romania (b) | Ecosystem services, forest management | Romania | |

| F | NGO | International NGO | Biomass certification, biodiversity conservation | Romania/International | |

| M | Academia | Forestry Faculty in Romania (b) | Biodiversity conservation, close to nature forest management | Romania | |

| M | Policy | Policymaking Body | Research and development | Belgium | |

| M | Academia | Forestry Faculty in Romania (a) | Forest governance, restitution rights | Romania | |

| Workshop 2 | M | Academia | Forestry Faculty in Romania (b) | Silviculture | Romania |

| F | Academia | Forestry Faculty in Austria | Local governance, social innovation | Austria | |

| M | Research | International Research Institute (a) | International trade networks, Bio-based products trade | Finland | |

| M | Research | International Research Institute (b) | Carbon storage, material substitution, LULUCF | Italy | |

| F | Academia | Romanian University | Social-ecological systems, knowledge co-creation, rural development | Romania | |

| M | Academia | Forestry Faculty in Austria | International forest governance, forest policy | Austria | |

| M | Academia | Austrian University | Wood-based innovations, technology innovation systems | Austria | |

| M | Academia | Forestry Faculty in Romania (b) | Remote sensing | Romania | |

| M | Private sector | International Company | Forest management, forestland investment | Romania/International |

Appendix B. Discussion Results of the Two Expert Workshops

- -

- Missing discussion about the meaning of “weak” and “strong” Sustainability concepts;

- -

- Lack of appropriate assessment of social and economic costs of Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) (especially environmental costs);

- -

- Lack of understanding of what sustainable forest management entails;

- -

- Lack of integrated approaches to management;

- -

- Tension between production forestry and conservation management;

- -

- Certification as an indicator for sustainable bioeconomy needs to be strengthened;

- -

- Top-down property rights. No policy, instruments, governance for property rights;

- -

- Unclear (financial) contribution of property rights to the economic sector;

- -

- Forest owners are not aware and not involved in the bioeconomy discussion;

- -

- Lack of appropriate funding (incentives) for SFM;

- -

- Funding goes to already established actors, not to small businesses and entrepreneurs;

- -

- Lack of appropriate funding for research and Development (R&D);

- -

- At European Union (EU) level, the bioeconomy is still a very broad, interdisciplinary concept: hard to grasp, implement, apply in practice;

- -

- EU strategies are shallow and broad. No bottom-up approach;

- -

- Romania has yet to produce a national bioeconomy strategy;

- -

- Romania does not have clear objectives, targets, visions, definitions etc. when it comes to bioeconomy and the forest-sector in particular;

- -

- The forest-based sector is not independent; there is pressure from different interest groups;

- -

- The forest-based sector lacks cross-connections with other sectors; Collaborative, cross-institutional collaboration is needed BUT lack of collaborative mindset in Romania, at individual level;

- -

- The political environment is highly unstable with short-term approach;

- -

- Politicians “hunt” academics and high profile specialists in order to gain personal benefits and political clout;

- -

- Decision-making highly influenced by emotional reasons rather than rational thinking;

- -

- Lack of discussion about the role of foreign investors and companies. What role do they play in the “national” bioeconomy;

- -

- Decision and lawmaking are not science-based;

- -

- Limited dialogue between professionals and policy makers;

- -

- Lack of adequate regulatory and policy support;

- -

- No agreement within political parties, who is responsible for what;

- -

- Sorting wood problem- high quality wood ends up as wood fuel;

- -

- Inaccurate and unreliable data;

- -

- Biometrics in Romania are based on forest that no longer exist;

- -

- There is no reliable data on the “true” annual removal;

- -

- Government is not yet fully acknowledging the National Forest Inventory (NFI) results-what is the base of “calculation”?

- -

- It is not known if there is enough biomass to feed a national forest-bioeconomy, not to mention an export-oriented one;

- -

- High competition for existing resources;

- -

- Unbalanced/unequal distribution of wood removals;

- -

- Lack of proper forest accessibility;

- -

- CO2 schemes not yet implemented at property level;

- -

- Romania is not aware of the effort ahead in terms of reductions of CO2 emissions;

- -

- Lack of knowledge regarding market tools/carbon farming;

- -

- It is unclear if Romania has enough forest resources for phasing out fossil fuels and nuclear energy;

- -

- Half of forest harvest is fuelwood-Romania must acknowledge this dire need for fuel wood;

- -

- fuel wood consumption/availability is an important aspect of local bioeconomies and rural development which has so far been ignored in policy discussions;

- -

- Unclear if fuelwood should even be part of bioeconomy discussion. Unknown if it is contributing to climate change mitigation;

- -

- Rural areas are not included in the bioeconomy discussion;

- -

- Regional vs. Global, lack of discussion on how to bring the global to the regional benefits;

- -

- Local communities’ role in bioeconomy is so far absent from discussions. There is no discussion about “local bioeconomy”;

- -

- Lack of discussion about RURAL DEVELOPMENT in bioeconomy strategies;

- -

- At a local level, we don’t have an adaptation of forest bioeconomy to social needs;

- -

- Stakeholder processes rather weak-trying to consider everyone and everything;

- -

- Lack of new, innovative products that can add value to existing supply chains;

- -

- There is no diversification of products;

- -

- Primitive approach in terms of selling the (raw) resources- increase harvesting in order to feed the bioeconomy and add value to the supply chains;

- -

- General lack of innovative products and services; It’s success is dependent on many actors’ capacity to collaborate;

- -

- A serious discussion about the role of social innovation, collaborative, bottom-up approaches is lacking;

- -

- Brain-drain, lack of skilled workers, low quality (funding, working conditions);

- -

- Lack of qualified people and personnel;

- -

- Education is highly centralized and outdated;

- -

- No adequate communication between the forest sector, NGOs and the general public;

- -

- Unknown consumer perception when it comes to wood-based products, e.g., wood construction and other bio-based products;

- -

- Consumer market is not there, lack of instruments. Fuelwood Ex. of Upscaling Romania’s needs to be transformed from a “handicap” to “advantage”

- -

- A common understanding of the concept- shared by professionals, policy makers and the general public;

- -

- A vision that goes beyond wood use, and the bioreffinery concept. One that includes the source (forests and forestry), consumers, along the entire value chain;

- -

- A holistic concept, that starts from source, goes along the value chain and ends with the consumer;

- -

- A service-based bioeconomy with the help of adequate tools (top-down, bottom up) to satisfy local (customer) needs;

- -

- One that starts from EU perspective but is adapted to Romanian reality (local, finance etc.) Upscaling of Romanian needs;

- -

- A system change, e.g., fuel demand with biofuels. Reduce our fuel consumption;

- -

- Go beyond market and production! Business as usual this time with natural resources;

- -

- Go beyond just being innovative with biomass; additionally including a system change;

- -

- Do things better, so that we manage to capture and store more Carbon;

- -

- A bioeconomy that balances resources with demand from industry and population;

- -

- Value added on chemically processed products-pulp paper, textile, food feed, energy;

- -

- Clear overview of the sector and its future development;

- -

- Qualified people in the forest-especially in the harvesting sector (the strongest visual impact on society);

- -

- A pathway to regionalizing value-chains, e.g., car or textile industry- shifting value chains back to Europe;

- -

- Link top-down to bottom-down strategies; tackle the problem from both sides;

- -

- Proper funding/incentives for economically viable and socially/environmentally responsible forest management;

- -

- High value-added forest economy with emphasis on local communities (which should be viable and prosperous) and local businesses;

- -

- Rational nature conservation in partnership with communities and in agreement with bioeconomy.

- -

- Set long-term goal and approaches;

- -

- Legislation, strategies, forest law- implement the concept of bioeconomy;

- -

- Cooperation between Ministry of Environment and Ministry of Agriculture;

- -

- Incentivize cooperation between different stakeholders, especially between the forest-based sector and other industries;

- -

- Improve data collection and data on indicators and monitoring;

- -

- Acquire better data on usage of wood in rural areas;

- -

- Use facts and scientific knowledge for decision-making in forest management and nature conservation (rooted in social and economic realities);

- -

- Proper funding for SFM at all ownership scales (and especially for private ownership);

- -

- Increase initiatives supported by NGOs and EU institutions;

- -

- Support innovative approaches and integrate them into practice;

- -

- Offer incentives/financial support for local communities and local businesses;

- -

- Reduce bureaucracy so that local small business can access EU funding more easily;

- -

- Reconsider the scaling issue;

- -

- Acknowledge the issues of migration, land abandonment, corruption. Keep the people in rural areas;

- -

- High-tech is good but acknowledge and support the traditional practices which are sometimes even more sustainable;

- -

- Move beyond production and growth narrative, focus on sufficiency and circularity;

- -

- Avoid embracing pathways that would destroy what’s already on the ground. Embrace and encourage local-level production and innovation, local consumption, local use etc.

- -

- Local and regional approaches depending on the particularities;

- -

- Diversify products from, e.g., lignin, pulp mills, etc.

- -

- Build upon the entire spectrum of ecosystem services;

- -

- Implement biodiversity-smart approaches;

- -

- Embrace innovation;

- -

- Develop vocational training;

- -

- Professionals at the top of decisions;

- -

- Forestry Curricula reform!

- -

- Create and share knowledge, with a focus on forest owners and other stakeholders;

- -

- Establish citizen information platforms;

- -

- Open social services;

- -

- Communication and social outreach;

- -

- Improve “image” of wood coming from Romania. Focus on different positive aspects (biodiversity, parks etc.);

- -

- Manage public opinions, negative image, bias media reporting etc.

- -

- Better public communication!

- -

- Enhance transparency (in reporting and policy making);

- -

- Make EU regulatory framework known to stakeholders;

References

- Staffas, L.; Gustavsson, M.; McCormick, K. Strategies and Policies for the Bioeconomy and Bio-Based Economy: An Analysis of Official National Approaches. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2751–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Langeveld, J.W.A.; Meesters, K.P.H.; Breure, M.S. The Biobased Economy and the Bioeconomy in the Netherlands; Biomass Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pülzl, H.; Giurca, A.; Kleinschmit, D.; Arts, B.; Mustalahti, I.; Sergent, A.; Seccco, L.; Pettenella, D.; Brukas, V. The Role of Forests in Bioeconomy Strategies at the Domestic and EU Level. In Towards a Sustainable European Forest-Based Bioeconomy-Assessment and the Way Forward; Winkel, G., Ed.; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2017; pp. 36–51. ISBN 9789525980417. [Google Scholar]

- Nordic Council of Ministers. Norden Nordic Bioeconomy: 25 Cases for Sustainable Change; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Piplani, M.; Smith-hall, C. Towards a Global Framework for Analysing the Forest-Based Bioeconomy. Forests 2021, 12, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MMAP. The National Forest Strategy 2030; Ministry of Environment, Waters and Forests: Bucharest, Romania, 2022; Available online: http://www.mmediu.ro/categorie/strategia-nationala-a-padurilor-2022-2031/386 (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Bosman, R.; Rotmans, J. Transition Governance towards a Bioeconomy: A Comparison of Finland and The Netherlands. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erkman, S. Industrial Ecology: An Historical View. J. Clean. Prod. 1997, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinski, L.W.; Graedel, T.E.; Laudise, R.A.; McCall, D.W.; Patel, C.K.N. Industrial Ecology: Concepts and Approaches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patermann, C.; Aguilar, A. The Origins of the Bioeconomy in the European Union. N. Biotechnol. 2018, 40, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioras, F.; Abrudan, I.V.; Dautbasic, M.; Avdibegovic, M.; Gurean, D.; Ratnasingam, J. Conservation Gains through HCVF Assessments in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Romania. Biodivers. Conserv. 2009, 18, 3395–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stăncioiu, P.T.; Niță, M.D.; Lazăr, G.E. Forestland Connectivity in Romania—Implications for Policy and Management. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichiforel, L.; Duduman, G.; Scriban, R.E.; Popa, B.; Barnoaiea, I.; Drăgoi, M. Forest Ecosystem Services in Romania: Orchestrating Regulatory and Voluntary Planning Documents. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 49, 101276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stăncioiu, P.T. Biodiversity Conservation in Forest Management. In The Plan B for Romania’s Forests and Society; Giurca, A., Dima, D.-P., Eds.; Transilvania University Press: Brasov, Romania, 2022; p. 49. ISBN 978-606-19-1463-0. [Google Scholar]

- Nichiforel, L.; Bouriaud, L. Changing Governance and Policies. In The Plan B for Romania’s Forests and Society; Giurca, A., Dima, D.-P., Eds.; Transilvania University Press: Brasov, Romania, 2022; ISBN 978-606-19-1463-0. [Google Scholar]

- Nichiforel, L.; Deuffic, P.; Thorsen, B.J.; Weiss, G.; Hujala, T.; Keary, K.; Lawrence, A.; Avdibegović, M.; Dobšinská, Z.; Feliciano, D.; et al. Two Decades of Forest-Related Legislation Changes in European Countries Analysed from a Property Rights Perspective. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 115, 102146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetemäki, L. Future of the European Forest-Based Sector: Structural Changes Towards Bioeconomy; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hetemäki, L.; Hanewinkel, M.; Muys, B.; Ollikainen, M.; Palahí, M.; Trasobares, A. Leading the Way to a European Circular Bioeconomy Strategy; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Winkel, G. Towards a Sustainable European Forest-Based Bioeconomy-Assessment and the Way Forward; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lovrić, M.; Lovrić, N.; Mavsar, R. Mapping Forest-Based Bioeconomy Research in Europe. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 110, 101874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navrátilová, L.; Výboštok, J.; Šálka, J. Stakeholders and Their View on Forest-Based Bioeconomy in Slovakia. Cent. Eur. For. J. 2021, 67, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwestri, R.C.; Miroslav, H.; Šodkov, M.; Sane, M.; Kašpar, J. Bioeconomy in the National Forest Strategy: A Comparison Study in Germany and the Czech Republic. Forest 2020, 11, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwestri, R.C.; Hájek, M.; Hochmalová, M.; Palátová, P.; Huertas-Bernal, D.C.; Garciá-Jácome, S.P.; Jarský, V.; Kašpar, J.; Riedl, M.; Marušák, R. The Role of Bioeconomy in the Czech National Forest Strategy: A Comparison with Sweden. Int. For. Rev. 2022, 23, 492–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad, I.M.; Toma, E. The Assessment of the Bioeconomy and Biomass Sectors in Central and Eastern European Countries. Agronomy 2022, 12, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scriban, R.E.; Nichiforel, L.; Bouriaud, L.G.; Barnoaiea, I.; Cosofret, V.C.; Barbu, C.O. Governance of the Forest Restitution Process in Romania: An Application of the DPSIR Model. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 99, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurca, A.; Dima, D.-P. (Eds.) The Plan B for Romania’s Forests and Society; Transilvania University Press: Brasov, Romania, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bugge, M.; Hansen, T.; Klitkou, A. What Is the Bioeconomy? A Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2016, 8, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jankovský, M.; García-Jácome, S.P.; Dvořák, J.; Nyarko, I.; Hájek, M. Innovations in Forest Bioeconomy: A Bibliometric Analysis. Forests 2021, 12, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Bioeconomy to 2030 -Designing a Policy Agenda. Main Findings and Policy Conclusions; OECD: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren, S.; D’Amato, D.; Giurca, A. Bioeconomy Imaginaries: A Review of Forest-Related Social Science Literature. Ambio 2020, 49, 1860–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goven, J.; Pavone, V. The Bioeconomy as Political Project: A Polanyian Analysis. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2015, 40, 302–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, S.; Ruault, J.F.; Moraine, M.; Madelrieux, S. The ‘Bioeconomics vs Bioeconomy’ Debate: Beyond Criticism, Advancing Research Fronts. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2022, 42, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausknost, D.; Schriefl, E.; Lauk, C.; Kalt, G. A Transition to Which Bioeconomy? An Exploration of Diverging Techno-Political Choices. Sustainability 2017, 9, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Georgescu-Roegen, N. Bio-Economics Aspects of Entropy. In Entropy and Information in Science and Philosophy; Kubat, L., Zeman, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, K.; Levidow, L.; Papaioannou, T. Sustainable Capital? The Neoliberalization of Nature and Knowledge in the European “Knowledge-Based Bio-Economy”. Sustainability 2010, 2, 2898–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Birch, K. The Neoliberal Underpinnings of the Bioeconomy: The Ideological Discourses and Practices of Economic Competitiveness. Genom. Soc. Policy 2006, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kircher, M. Bioeconomy: Markets, Implications, and Investment Opportunities. Economies 2019, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolfslehner, B.; Linser, S.; Pülzl, H.; Bastrup-Birk, A.; Camia, A.; Marchetti, M. Forest Bioeconomy—A New Scope for Sustainability Indicators. From Science to Policy 4; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfahrt, J.; Ferchaud, F.; Gabrielle, B.; Godard, C.; Kurek, B.; Loyce, C.; Therond, O. Characteristics of Bioeconomy Systems and Sustainability Issues at the Territorial Scale. A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawel, E.; Pannicke, N.; Hagemann, N. A Path Transition Towards a Bioeconomy—The Crucial Role of Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palahí, M.; Pantsar, M.; Costanza, R.; Kubiszewski, I.; Potočnik, J.; Stuchtey, M.; Nasi, R.; Lovins, H.; Giovannini, E.; Fioramonti, L.; et al. Investing in Nature as the True Engine of Our Economy: A 10-Point Action Plan for a Circular Bioeconomy of Wellbeing; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Markard, J.; Stadelmann, M.; Truffer, B. Prospective Analysis of Technological Innovation Systems: Identifying Technological and Organizational Development Options for Biogas in Switzerland. Res. Policy 2009, 38, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurmekoski, E.; Hetemäki, L. Studying the Future of the Forest Sector: Review and Implications for Long-Term Outlook Studies. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 34, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, P.J.; Kramp, A.; Skog, K.E. Evaluating Economic Impacts of Expanded Global Wood Energy Consumption with the USFPM/GFPM Model. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Rev. Can. D’agroeconomie 2012, 60, 211–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzbauer, P.; Weinfurter, S.; Stern, T.; Koch, S. Economic Crises: Impacts on the Forest-Based Sector and Wood-Based Energy Use in Austria. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 27, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, K.B.; Westholm, E. Future Forests: Perceptions and Strategies of Key Actors. Scand. J. For. Res. 2011, 27, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, R. Trends and Possible Future Developments in Global Forest-Product Markets—Implications for the Swedish Forest Sector. Forest 2011, 2, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bell, W. Foundations of Futures Studies: History, Purposes, and Knowledge; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann, N.; Gawel, E.; Purkus, A.; Pannicke, N.; Hauck, J. Possible Futures towards a Wood-Based Bioeconomy: A Scenario Analysis for Germany. Sustainability 2016, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hurmekoski, E.; Lovrić, M.; Lovrić, N.; Hetemäki, L.; Winkel, G. Frontiers of the Forest-Based Bioeconomy—A European Delphi Study. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 102, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Entman, R.M. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NFI. Rezultate IFN—Ciclul II | National Forest Inventory. Available online: https://roifn.ro/site/rezultate-ifn-2/ (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Nicolescu, V.-N. Romanian Forests and Forestry: An Overview. In The Plan B for Romania’s Forests and Society; Giurca, A., Dima, D.-P., Eds.; Transilvania University Press: Brasov, Romania, 2022; pp. 39–48. ISBN 978-606-19-1463-0. [Google Scholar]

- MAPPM. Norme Tehnice Pentru Amenajarea Pădurilor (Ministry Order 1672/2000, Technical Norms for Forest Management Planning); MAPPM: Bucharest, Romania, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives. COM(2020) 380 Final.; European Commission: Brusse, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Drăgoi, M.; Toza, V. Did Forestland Restitution Facilitate Institutional Amnesia? Some Evidence from Romanian Forest Policy. Land 2019, 8, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- INDUFOR. Support to the Establishment and Development of Associations for Local ForestOwners (ALFOs); INDUFOR: Helsinki, Finland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Borz, S.A.; Derczeni, R.; Popa, B.; Nita, M.-D. Regional Profile of the Biomass Sector in Romania; Brasov, Romania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Osburg, V.S.; Yoganathan, V.; Brueckner, S.; Toporowski, W. How Detailed Product Information Strengthens Eco-Friendly Consumption. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 1084–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buliga, B.; Nichiforel, L. Voluntary Forest Certification vs. Stringent Legal Frameworks: Romania as a Case Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blujdea, V.N.B. How to Balance Forest Management with Wood-Use for a Climatically Neutral Economy? In The Plan B for Romania’s Forests and Society; Giurca, A., Dima, D.-P., Eds.; Transilvania University Press: Brasov, Romania, 2022; pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Energy. Strategia Energetică a României 2016-2030 Cu Perspectiva Anului 2050 [The Energy Strategy of Romania 2016-2030 with the Perspective of 2050]; Ministry of Energy: Bucharest, Romania, 2016.

- National Institute of Statistics. Consumurile Energetice Din Gospodării [Household Energy Consumption]; National Institute of Statistics: Bucharest, Romania, 2010.

- Popa, B.; Nița, M.D.; Nichiforel, L.; Bouriaud, L.; Talpa, N.; Ionița, G. Sunt Datele Publice Privind Recoltarea Și Utilizarea Lemnului În România Corelate? Studiu de Caz: Biomasa Solida Cu Destinatie Energetica, Provenita Din Silvicultura. Rev. Pădurilor 2020, 135, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lovrić, M.; Moiseyev, A. Romanian Production and International Trade of Forest-Based Products. In The Plan B for Romania’s Forests and Society; Giurca, A., Dima, D.-P., Eds.; Transilvania University Press: Brasov, Romania, 2022; pp. 118–129. [Google Scholar]

- Dima, D.-P. Business Models That Can Unlock the Potential of the Romanian Forest-Based Sector. In The Plan B for Romania’s Forests and Society; Giurca, A., Dima, D.-P., Eds.; Transilvania University Press: Brasov, Romania, 2022; pp. 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ludvig, A.; Zivojinovic, I.; Hujala, T. Social Innovation as a Prospect for the Forest Bioeconomy: Selected Examples from Europe. Forests 2019, 10, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvig, A.; Diaconescu, A. Social Innovation and the Forest Bioeconomy: Challenges and Prospects for Romania. In The Plan B for Romania’s Forests and Society; Giurca, A., Dima, D.-P., Eds.; Transilvania University Press: Brasov, Romania, 2022; pp. 112–117. [Google Scholar]

- Horcea-Milcu, A.I. Rural Development and Sustainable Transformations. In The Plan B for Romania’s Forests and Society; Giurca, A., Dima, D.-P., Eds.; Transilvania University Press: Brasov, Romania, 2022; pp. 176–184. [Google Scholar]

- Bouriaud, L. Forest Education in the Era of Bioeconomy. In The Plan B for Romania’s Forests and Society; Giurca, A., Dima, D.-P., Eds.; Transilvania University Press: Brasov, Romania, 2022; pp. 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Masiero, M.; Secco, L.; Pettenella, D.; Da Re, R.; Bernö, H.; Carreira, A.; Dobrovolsky, A.; Giertlieova, B.; Giurca, A.; Holmgren, S.; et al. Bioeconomy Perception by Future Stakeholders: Hearing from European Forestry Students. Ambio 2020, 49, 1925–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urmetzer, S.; Lask, J.; Vargas-Carpintero, R.; Pyka, A. Learning to Change: Transformative Knowledge for Building a Sustainable Bioeconomy. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 167, 106435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRES Percepții Și Atitudini Privind Protejarea Mediului Și a Animalelor Sălbatice. Available online: https://ires.ro/uploads/articole/ires_protejarea-mediului-si-a-animalelor-salbatice_2021_sondaj-national_partea-a-iii-a.pdf?fbclid=IwAR3gtADXLNftWhjwb0RRXX5TcBrdmAMK1kW5kJwa2IVsbwkel04HXSm0pww (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Holmgren, S.; Giurca, A.; Johansson, J.; Kanarp, C.S.; Stenius, T.; Fischer, K. Whose Transformation Is This? Unpacking the ‘Apparatus of Capture’ in Sweden’s Bioeconomy. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2022, 42, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivien, F.D.; Nieddu, M.; Befort, N.; Debref, R.; Giampietro, M. The Hijacking of the Bioeconomy. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 159, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Types of Expertise | Country |

|---|---|---|

| 12 male 4 female | 11 Academia 2 International research 1 Policy making 1 Industrial Company 1 NGO | 8 Romania 2 Romania/international 3 Austria 1 Finland 1 Italy 1 Belgium |

| Theme | Main Arguments | Specific Initiatives |

|---|---|---|

| Forward-looking policy-making Different initiatives related to policies, politics and policymaking at a national and EU- level are grouped under this theme. | Romania does not have a clear vision, objectives and targets when it comes to the bioeconomy. The political environment is highly unstable and decision-making is often short-termed. The EU bioeconomy policies are rather broad and bottom-up approaches are needed to adapt them to the national context. |

|

| Enhance Cooperation This theme mainly refers to cooperation between different stakeholders of the forest-based sector but also to cooperation between the forest industry and other sectors and industries relevant to the bioeconomy. | The forest-based sector is not independent and must cooperate with other sectors (e.g., agriculture, energy, biodiversity, pharmaceutical industry, textile industry etc.). The sector also lacks cooperation with other sectors. There is a lack of collaborative mindset at both individual and policy level. |

|

| Provide better data, indicators, and monitoring This theme groups various data- and monitoring- related initiatives to support fact-based decision-making. | Important discrepancies exist between the data collected by different institutions in Romania describing the forest status, wood production, timber processing and consumption (see Section 4.1); moreover, for non-timber forest products (NTFP) there is a lack of accurate data regarding their share on the market. |

|

| Increase funding/financial incentives This theme mainly includes financial incentives for supporting the development of the forest-based sector. | Romanian forest policy remained focused on the command-and-control paradigm for implementing sustainable forest management. This top-down approach is inefficient. Financial incentives are necessary for the forest sector to unlock its innovative potential. |

|

| Focus on rural development This theme bundles together different initiatives targeted at supporting and incentivizing local bioeconomy initiatives that can support rural development. | Local communities are an important pillar in the Romanian economy and particularly in the forest sector. They are crucial for providing forest-related jobs, for developing local businesses, and producing and marketing different forest products. The needs, capabilities and values of local communities are diverse providing for contrasting approaches at local levels in the management of forest resource. Navigating these challenges constitutes a delicate act for implementing the bioeconomy principles. |

|

| Diversify products and supply chains This theme includes initiative targeted at diversifying supply chains and product portfolios, beyond the classical forest-based products and services. | Despite the positive foreign trade balance of the forest sector, which relies on value added products (e.g., furniture, particle boards, timber frames), the high value timber products provided by Romanian forests are not efficiently used along the supply chain. The approach used for timber selling, firewood consumption, and the high bureaucratic costs hinders innovation capacities. |

|

| Strengthen education and training This theme refers both to academic education (i.e., establishing bioeconomy curricula) but also to training targeted at professionals. | Generally, the current forestry educational system integrates economy, society and natural sciences in its curricula thus offering good preconditions for a bioeconomy educational program. However, the rapidly changing societal and technological development requires research and education to support an adaptive forest management, innovation in forest-based bioeconomy and to provide skilled workers for the forest sector of tomorrow. |

|

| Improve Communication This theme mainly refers to improving communication within and between the institutions responsible for the forest sector and decision-making, as well as between forest managers and the general public. | The lack of proper communication strategies from national authorities and professional associations have resulted in a negative image of the forest sector at the national and international level. The current messages presented to the general public are focused on illegal logging, deforestation and improper natural protected areas management which are more often not backed-up by accurate data. Promoting the role of sustainable management for ensuring stable and resilient forests and the role of wood products resulting from sustainably managed forests is an important challenge for the implementation of bioeconomy principles. |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giurca, A.; Nichiforel, L.; Stăncioiu, P.T.; Drăgoi, M.; Dima, D.-P. Unlocking Romania’s Forest-Based Bioeconomy Potential: Knowledge-Action-Gaps and the Way Forward. Land 2022, 11, 2001. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11112001

Giurca A, Nichiforel L, Stăncioiu PT, Drăgoi M, Dima D-P. Unlocking Romania’s Forest-Based Bioeconomy Potential: Knowledge-Action-Gaps and the Way Forward. Land. 2022; 11(11):2001. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11112001

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiurca, Alexandru, Liviu Nichiforel, Petru Tudor Stăncioiu, Marian Drăgoi, and Daniel-Paul Dima. 2022. "Unlocking Romania’s Forest-Based Bioeconomy Potential: Knowledge-Action-Gaps and the Way Forward" Land 11, no. 11: 2001. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11112001

APA StyleGiurca, A., Nichiforel, L., Stăncioiu, P. T., Drăgoi, M., & Dima, D.-P. (2022). Unlocking Romania’s Forest-Based Bioeconomy Potential: Knowledge-Action-Gaps and the Way Forward. Land, 11(11), 2001. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11112001