1. Introduction

Secure land rights are intrinsic to achieving the 2030 agenda and specifically the land related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

1 [

1]. The need for secure land rights demands that existing land governance approaches are adapted and gives rise to calls for more responsive or responsible land administration [

2]: conventional land administration approaches have been seen to be too inefficient and not sustainable in delivering formal land documentation [

3]. The various inefficiencies present in existing land administration approaches need to be overcome in order to achieve the 2030 agenda [

4].

In this vein, a marked momentum towards innovative land administration can be seen. Global institutions, in support of national and more local governments, promote developments reflecting the continuum of land rights [

5,

6]. The International Federation of Surveyors (FIG) supports the adoption of fit-for-purpose land administration (FFPLA). This philosophy counters dogmatic legal and administrative techniques and calls for nationally or locally appropriate methods [

3,

7]. FFPLA solutions are intended to be flexible, affordable, and achievable: they present opportunities for the application of innovative and suitable technologies [

8]. This approach allows flexibility in land administration design, and upgrades or improvements in terms of data quality, or reductions to time and costs.

Key issues for FFPLA include sustainable funding models and overcoming land agency inertia, amongst others. Even though global development institutions—most notably via the World Bank—assist and fund reforms and programmes, implementation may remain dependent on the recipient government’s human resources and operational budget allocated for execution and long-term maintenance. The responsibility to deliver on donor projects objectives can be too overwhelming for governments in this regard.

Existing research has explored land administration interventions in the frame of partnerships mostly funded by donors, where the private sector actors involved tend to come from within the land sector, as service providers, and their involvement is often merely focusing on technical delivery [

9,

10,

11]. It is therefore worthy to continue exploring novel ways in which broader private sector actors, such as food and agricultural sectors, who may often deeply rely on land tenure security, can engage in the land administration initiatives through partnerships.

In this regard, the paper begins from the premise that private sector companies in sectors such as agriculture and food production are now increasingly incentivised to engage in land administration. This is particularly relevant to those transitioning towards sustainable supply chains and having the required evidence surrounding those to ensure the achievement of corporate social responsibility ambitions. Private sector corporations often have a close relationship to certain commodity-producing countries and governments. This creates a context and opportunity that allows for new flexible types of public-private partnership financing and implementation of FFPLA.

In response, the aim of this paper is to introduce a novel PPP to the FFPLA literature; one that further examines alternatives for the participation of private actors from outside the land administration sector. Rather than building solely from theory or literature, a case from practice in the context of Côte d’Ivoire is used to illustrate the approach. Due to the recency of the case, and constraints on presenting any longitudinal impacts, the paper focuses on presenting the drivers, requirements, and possible design options of such a PPP. Despite this limitation, what is presented is considered to be of high interest to the FFPLA discourse.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. First, a background section unpacks the needs and challenges in adopting the FFPLA approach and previous experiences of land administration PPPs. Second, the case study method applied is explained. Third, the results of the case study are described based on analysis of the context, differences of the case when contrasted with other land administration PPPs, and other novel aspects. Fourth, the key learnings, challenges and opportunities—including the possibility for generalisation—are discussed in order to lay the ground for future innovations to PPPs implementing FFPLA.

2. Background

2.1. Sustainability and FFPLA

It is necessary to provide a brief background on FFPLA in terms of how it intends to contribute to the broader sustainability agenda, but, also to unpack the issues relating to the sustainability of FFPLA initiatives in their own right, particularly with regards to financing.

Recording the relationships of people to land unveils complexities that are intrinsic to each local social system. For those involved in the design and execution of land administration, registering land rights is a cross-cutting disciplinary challenge, from technical implications through to social dimensions. Acknowledging that tenures come in different forms, and can exist beyond legal or statutory prescriptions, new tools and approaches are needed to facilitate the recording of so-called ‘customary’ or ‘traditional’ rights. Attention must be paid to ways that the complexities and pluralities of existing customary rights can be addressed in land administration systems [

12]. It is argued that land administration systems should seek to follow emerging global policies and guidelines, as advised in the Framework for Effective Land Administration (FELA), a guidance document which serves as a global reference for land administration policy [

13].

In comparison to conventional land administration approaches, which tend to be generalised and technically standardised, the FFPLA approach focuses on fitting characteristics into a specific context, for a purpose, and to meet the needs of all people, including vulnerable groups. On this, FELA refers to FFPLA because it aligns to the continuum of land rights, with the objective of providing ‘security of tenure through recognition of legitimate rights’ and recording the corresponding evidence of rights on a national register that is publicly accessible [

14]. Especially, with the adoption of technology, FFPLA can contribute improvements to processes and enable the necessary functionalities for the recordation of the continuum of land rights that conventional methods tend to lack. This is in addition to, for example, recognition of broader land-related social elements; cost-effectiveness, efficient and interoperable capabilities; expedited data collection and automation; and bottom-up processes (although the FFPLA approach is usually implemented top-down), among others [

15,

16,

17].

When implementing FFPLA, a multi-stakeholder and multi-disciplinary approach can potentially translate into more complexity in technical processes [

16]. It is therefore important to carefully discern the roles and responsibilities of actors, funding, partnerships, and other FELA aspects. Implementers need to achieve ‘balance’ between global technical norms and local land governance arrangements. An issue complicating innovation is often found at the financial level: developing innovative approaches, adapting them to unique contexts and involving multiple stakeholders across all levels, can all help to spiral out costs as in previous experiences in Canada and Malaysia (addressed later) [

9].

Sustainable funding mechanisms remain a major barrier for governments in developing countries to both introduce and sustain land administration efforts. The land administration community should always remain open to exploring novel models of collaboration between stakeholders; ones that may open new funding opportunities to deliver FFPLA. In this regard, the private sector can benefit from FFPLA as a vehicle for delivering on the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests (VGGT), that supports the SDGs and corporate social responsibility objectives [

8]. In these guidelines, the private sector can adopt voluntary roles such protecting human and legitimate tenure rights of local and indigenous communities, creating partnerships, and preventing conflict [

8]. Additionally, understanding that sectors are interdependent, there may be opportunities for a deeper engagement of the private sector in FFPLA for generating shared value between partners and supporting SDGs delivery [

18,

19]. The literature provides an understanding of how land administration partnerships allow private sector actors, mainly from within the land sector to assist governments. However, alternative models bringing corporate actors into FFPLA are still rare and underexplored, at least in the published literature.

Therefore, in summary there is an opportunity to explore cases within FFPLA where private sector actors play a key role—even as drivers of FFPLA—and facilitate recordation and documentation of the land rights of smallholders

2 [

20] within supply chains, as part of their broader social corporate responsibility and sustainability actions.

2.2. PPPs in Land Administration

Historically, the public sector has been responsible for owning (on behalf of citizens), operating and delivering most land administration services. Large-scale operations require large investments to not only cover the cost of land documentation, but, other overhead expenditures (e.g., technical assistance, training etc.) [

9,

21]. Developing countries have often struggled to afford land administration systems without external financial support, in comparison with developed countries, where land administration systems are well established and often profitable through enforced land related taxes, fees, and other charges [

22].

For decades, the international community

3 has been providing financial support to governments to assist their endeavours to register land and to develop or modernise land administration methods and systems [

23,

24,

25]. On this, the World Bank has supported land reforms, policy and land registration projects in developing countries [

26]. Not only financial institutions, but, also different actors other than governments can play a substantial role too. A PPP can be considered an approach involving shared responsibilities through contractual cooperation between the public and private sectors to provide a product or service, often sharing risks, responsibilities and remuneration [

27,

28,

29].

Able to be classified as different types (addressed later in the paper), PPPs involve different sectors, not only land, and have been utilised in developing countries to maximise use of public resources. Also, PPPs allow other non-traditional actors and international development organisations to take part in solution development.

There already exists recorded cases of PPPs dedicated to traditional land administration activities, originated by governments and/or donors with land service operators [

30]. Learnings include that PPPs can facilitate private investment, cost-sharing, efficient risk-allocation, and efficient use of public funds. In terms of management, PPPs can enable expertise-based efficiency, and strengthen the public sector capacity for delivery, and allow the private sector to share innovations and new technologies securely [

10]. PPPs may also bring flexible and customer-oriented land registration services and may improve procedures of land registration [

27]. Additionally, PPPs are said to bring higher levels of service delivery, cost-effectiveness and reduction of investment risks for the parties involved [

8,

27]. However, the success or failure of a PPP can be marked by any resultant increase in levels of corruption, and any increase of costs of services as a result of a PPP [

31,

32].

Over the years, PPPs for conventional land administration focused on reform and infrastructure developments, and also focused on Land Administration Systems (LAS) [

28]. In most cases, private specialised firms executed projects directly through contracting out services and focusing on creating land registries in both developing and developed countries [

8,

10]. The following paragraphs show some of these experiences.

Recent land administration PPPs in Canada and Australia, relating to the management and storage of transactions, are characterised by long-term relationships between governments and operators for periods of over 35-40 years duration, as well as the interest of reformulating processes and building automated systems with IT infrastructures [

8,

10]. Some of the challenges identified in those two cases are: the risk of customer needs being poorly integrated into the registry system; unexpected delays and increased implementation costs; risky public data management; overly long-term periods of registries operated by private parties (it may be difficult for the government to resume control of the system successfully immediately without the experience, capacity or human resources required); a structural lack of transparency; vulnerability to corruption within related sector, and dependency to private operators interests [

8,

10]. Besides, it is important to consider if long-term relationships have implications on the property market.

Cases in the Philippines, India and Malaysia have focused on progressing digitisation of processes and e-Government [

8,

9,

10]. Showing that difficulties to digitise registries, even with participation of private sector, may originate from the government’s lack of operational capacity; failure of private parties to ensure fully functioning systems; lack of expertise by private sector parties in land registry/automation; and thereby, unexpected long delays to delivery. In the case of Malaysia, the creation of e-Tanah (electronic land administration and management system) provides important lessons. After an initial failure, the private sector re-invested and eleven years were necessary before e-Tanah showed results

4.

On the other hand, New Zealand seems to have adopted an innovative approach in which collaboration with the private sector consists of procuring a suitable service model and paying the provider for its use [

8].

Other experiences of a less dominant, but, complementary participation of private sector parties in diverse FFPLA projects worldwide, have depended heavily on donor funding. In Mozambique, for example, registration projects have been mainly funded by international donors focused on supporting local communities in registering their land rights. Mapping, delimitation and registration processes were supported by private land service providers contracted by the government with donor funding. Since 2011, land rights registration has been conducted with five different complex programmes but most of the donors involved have been discontinuing their support. Despite the potential opportunities, implementation challenges included lack of capacity, funding to develop a database of community landholdings, difficulties in maintaining the register, and the weak integration of local communities’ data into governmental datasets [

33,

34]. In the cases of Canada and Malaysia, for example, risks have been jointly mitigated between parties through re-investment, sustaining allocation of resources and agreeing on an extension of the project duration [

9].

These past experiences provide not only lessons on challenges—such as limited resources and weak contract/contractor management—but, also indications of success factors for private sector implementers. Examples include knowledge of global and regional contexts, requirements, processes, products and activities; capacity in different disciplines and capacity required for land administration; organisational stability despite context changes; risk management capacities; and direct supervision over contractors and collaboration flexibility [

35].

That said, it is still somewhat unclear if and to what extent the FFPLA approach has been adopted in previous land administration PPPs. FFPLA PPPs seem new, or the FFPLA literature often does not describe the use of PPPs in FFPLA explicitly, and it is still necessary to seek to understand how FFPLA and PPPs can be most suitably combined to identify differences with the traditional PPP models.

Overall, no cases led by commodity sector industries (such as the cocoa sector) are observed in the literature. Exploring other collaboration formulas may contribute to broader and more innovative avenues for providing financial solutions and added capacity to FFPLA.

3. Methodology

Fundamentally, the exploratory work underpinning this paper can be considered to follow the interpretivist, if not pragmatic, research paradigm, and subsequently a qualitative research methodological approach could be applied. Specifically, in order to respond to the aims of the paper, that is, to further explore and expand upon knowledge relating to the use of PPPs in FFPLA, and to introduce a new type of PPP, a case study approach was applied. Specifically, a case study of the ‘Côte d’Ivoire Land Partnership’ [

36], was undertaken, and the potential innovations to PPPs in land administration were explored. The case study initiative was selected because of the familiarity of the authors with the case. This potential for bias needs to be acknowledged. The case study largely included collection and analysis of secondary data sources, although the author experiences also informed the critique. The case study was exploratory in nature, rather than explanatory or confirmatory. The aim was to explore the involvement of non-conventional private sector actors in innovative FFPLA partnerships—in terms of how they might engage actively, or not, in securing land rights for vulnerable smallholders in developing countries.

Regarding the case study selection, Côte d’Ivoire was considered ideal since it is actively seeking to develop its agricultural markets and also its land administration system at the same time. The country has a high cocoa production as well as a current lack of alternatives for formalisation of land rights different to donor-led initiatives. The case, the Côte d’Ivoire Land Partnership (CLAP), was setup by the partners in CLAP, primarily through Meridia (explained below). Since July 2019, three phases were introduced before an early scale implementation: country scoping, feasibility, and design and testing (to be finalised in mid-2021). The early scale implementation is intended to run from April 2021 until the end of 2023. Therefore, it is acknowledged that results presented here, with regards to implementation success and impact, can only be considered preliminary. However, aspects relating to drivers, requirements, and design inputs are considered to provide insights on how a PPP in FFPLA could look like.

A review of existing evidence in the literature presenting FFPLA and relevant PPP references, guidelines and previous experiences, as well as private documentation of Meridia’s FFPLA experiences, and the authors’ experiences informed the data collection. Then, data was analysed and contrasted with the existing literature to analyse the results systematically. Including the specific context of Côte d’Ivoire, partners, rationale and nature of the PPP model, how it adopts FFPLA and the challenges and limitations involved were explored.

In terms of data collection, to commence the case study work, an initial literature review based on documents and reports—both publicly available and privately sourced—was used to build the background context on PPPs and the case country. Secondary data was then collected from the documented experiences of involved private sector actors, that were involved in Côte d’Ivoire between 2019 and 2021. These materials were made available to the authorship team: it is acknowledged that some members of the authorship team have direct affiliation with Meridia, the Dutch-based private land documentation firm, implementing the case explored.

With regards to data analysis, extracting details on the country context, the partners involved, the rationale of the PPP, the type and design of partnership models, the adoption of FFPLA by the PPP and implementation challenges were considered. It is important to note that the paper does not examine in-depth the funding/finance issues. Novel aspects were also analysed with existing FFPLA frameworks in mind [

10,

37,

38].

After compiling the data into results, these were presented systematically. This paid attention to PPP design characteristics, the functioning of the case, and the generalisation of findings to other FFPLA interventions.

4. Case Study Results

In the following sub-sections, the case of Côte d’Ivoire, describing a variation of a conventional land administration PPP from the cocoa sector—in the implementation of land registration for rural right holders—is described. First, an overview of land administration is provided. Then, a description of the novelty in terms of design, requirements, and implementation, based on the early learnings from an on-going pilot, are presented. Subsequently, discussion undertakes a comparison and contrast with other more traditional partnership models.

4.1. Land Administration in Cote d’Ivoire

Until 2019, rural land comprised 71% of the country and occupied 48.75% of the total population. Agriculture has been a major driver for economic growth since 1950s. Similarly, cocoa production has been mobilising people within and from outside the country. The country has seen decades of conflicts and political tension [

39,

40].

Conflicts between customary land holders and more recent migrants (both nationals and/or foreigners, or allochtones and/or allogènes in French—respectively) are mostly related to disputed land rights [

41]. Without secure over ownership or use rights, tensions between social groups are, and were, constantly increasing. Besides, land governance is complex because customary and statutory tenures can coexist: land has been traditionally held by customary law, but the State administers land and property through formal registration processes. Findings from similar settings in other geographic locations indicate that FFPLA could be relevant to the Ivorian context: FFPLA has the same characteristics in both land-related conflict contexts and non-conflict contexts [

42].

The Ivorian Government has set up reforms, updated policies and introduced specialised institutions that facilitate the advancement of rural land registration. The Rural Land Law, created in 1998 and amended in 2019, recognised rights acquired before the law took place, taking customary rights into account while promoting the formalisation of these and other types of rights [

39,

43]. The law promotes the conversion of customary rights into statutory rights, and originally established a 10-year period for rural land registration and delivery of land certificates to traditional owners before unregistered land would return to the State’s ownership. Also, modifications to the constitution in 2016 established the right to property as a guarantee for all Ivorians and vested ownership of rural and agricultural lands to the State, public entities and Ivorian citizens.

Rural land registration in the country can be done through three different types of formal documents recognised by the government: land titles, land certificates and land use contracts

5 [

44].

Land registration involves an interaction of multiple actors across the national, sub-prefecture and village level. As part of the institutional setting, the Ivorian government created AFOR (Agence Foncière Rurale—AFOR), or Rural Land Agency, in 2016. AFOR is a decentralised institution dedicated to implementing the Rural Land Law and is in charge of land registration operations. Just as in other cases, decentralisation can be considered as effective, but also challenging for the implementation of FFPLA [

45].

At any rate, the Ivorian government has not been able to register existing customary rights over rural land, at least, at scale. In 2019, only around 0.5% of the targeted land certificates have been delivered

6 [

46]. The government must ensure efficiency in the implementation of its land registration programme before unregistered land can be retrieved by the state. However, challenges have overruled recent efforts. The commonly expensive cost of issuing land certificates, without funding from donors, are not affordable for landowners, including cocoa farmers, considering that the income of a cocoa household from all sources is around 2400 EUR per annum [

47]. People used to pay between XOF 980 k—1.4 M (equivalent to USD 1747–2621 or EUR 1498–2247) when applying for a certificate individually.

In early pilot free registration programmes

7 the cost of land certification to the government was between 500,000 XOF and 1 million XOF (equivalent to around 760 to 1500 EUR) for a 3-hectare parcel in the south of the country [

39].

AFOR has been working to improve documentation processes at the same time as prioritising land certificates and land use contracts [

48]. Currently, AFOR—with support from the World Bank—is implementing the Land Policy Improvement and Implementation Project for Cote d’Ivoire (PAMOFOR). AFOR is being assisted in implementing the country’s land policy, establishing national geodetic infrastructure, developing the capacities necessary to operate land registration, modernising the land information system, and testing the roll out of systematic registration and documentation under participatory, streamlined, simplified and less costly processes [

49].

AFOR developed the national land administration system (Système d’Informations Foncières de l’AFOR—SIFOR) and started a free registration project. According to AFOR’s Manual of Operations, the national registration process involves institutions from all levels including grassroot village land governance institutions [

46]. At the community level, village land management committees (Comité Villageois de Gestion Foncière Rurale—CVGFR) are in charge of community-based management of traditional land. These committees are formed by the traditional chief as well as other community leadership and group representatives. These committees are supervised by sub-prefectures, sub-prefectural rural land management committees (Comité Sous-Préfectoral de Gestion Foncière Rurale—CSPGFR) and AFOR, and are supported by land surveyors—especially in management of land owner-tenant agreements contracts. Given the pressing timeline, limited capacities and human capital available to implement the Rural Land Law it appears that, although supported by the World Bank through PAMOFOR

8, the government still requires support in order to meet the rural land registration deadline.

4.2. The Cote d’Ivoire Land Partnership (CLAP)

4.2.1. Drivers and Motivation

The fragile tenure security of cocoa farmers including migrants, in conjunction with the sustainability issues of the country related to agricultural activities (deforestation, land pressure), led to attention by private transnational companies to securing rural land tenure, in support of their own objectives. Since 2019, The Hershey Company, based on an earlier positive experience in Ghana with USAID

9, engaging on the sensitive topic of affordable and acceptable land titling documents, brought together companies to promote the creation of the Côte d’Ivoire Land Partnership (CLAP).

With this antecedent, CLAP focused on developing affordable land documentation at scale for Ivorian smallholder farmers by aiming to develop a similar cost-efficient service approach—thus accelerating land registration in cocoa farming areas, as well as helping the government maximise public resources in other areas across the country as needed. Then, documents were to be facilitated and subsidised for supply chain farmers to register their own rights to land or crops depending on their tenure situation. The only commitment needed from farmers was to contribute to the cost of the document by paying a small part (up to 20%).

4.2.2. Partners and Relationships

The partnership was originally formed by cocoa industry leaders—The Hershey Company, Unilever and Cocoa Horizons Foundation, the Ivorian government through AFOR, the Foundation of the German Cocoa and Chocolate Industry, and Meridia. While the private sector actors provide funding and service delivery, the local government enabled a political environment for interventions, provided in-kind contributions, collaborated in the execution of projects and operated the land information system/registry to which CLAP service connects with.

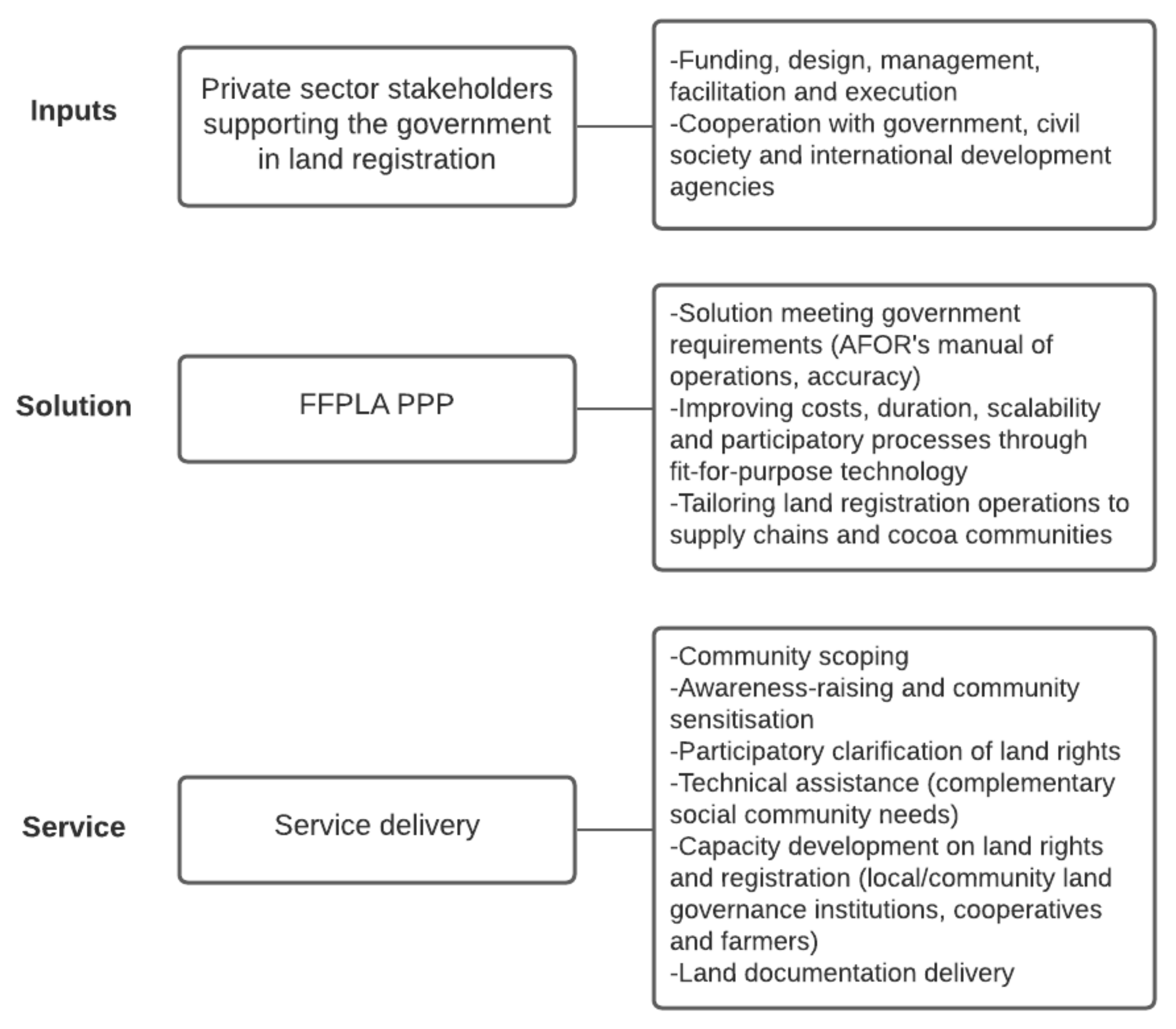

The design also involves donor agencies and civil society (see

Figure 1): International development agencies provided funding and technical assistance needed at the social and sustainability levels, and civil society organisations address needs at the community level.

4.2.3. Initiation and Timeline

In 2020, CLAP conducted a feasibility study; one recommended step for the establishment of a PPP for land administration [

50]. During eight months, the partners explored the land tenure and social local contexts in the country’s farming areas; the legal, regulatory and institutional frameworks and their suitability for CLAP tenure projects under a commercial model; a solution to scale-up land rights registration specifically focused on cocoa farming areas; and a financial model adjusted to the context. Specifically, the feasibility study components included the understanding of specific issues of the Ivorian rural land context, alignment of stakeholders and identification of actors relevant to the partnership and its objective, social/community acceptance (including demand and affordability from farmers), identification of vulnerable groups and types of access to land, legal and institutional structures (from government to community levels), legal operational compliance, validation of a business case for investment by the private sector in the land rights of cocoa farmers within supply chains, and adaptation of systems and fit-for-purpose technologies.

Then, in the design phase, from mid-2020 to mid-2021, the partnership with support from the Dutch government, focused on testing the service model through a first pilot in one area in the south of the country

10. The on-going pilot was accepted by the communities targeted, the rest of the stakeholders subsequently committing to continuing the partnership and running an early scale project until 2023.

In terms of duration, CLAP has been conducted through sub-projects and by stages without foreseeable permanent system leasing with the government. In the first stage, the PPP aimed to operate an early scale registration project from 2021 to 2023. The short period of the first project may be an opportunity for improvements and adjustments that long-term agreements in other PPPs do not easily enable.

4.2.4. Ownership, Management, and Finance

CLAP focused on service delivery and improvement of processes. Compared to other PPPs in the sector, no relevant partnership type was found to align fully with CLAP.

Starting with the distribution of responsibilities, in CLAP, these differed from those in the most common and accepted types for land registration services discussed in existing scholarship and thematic texts [

8,

24]. The land administration system, to which the CLAP projects integrated, is fully designed, built, owned and operated by the Ivorian government. For this reason, CLAP does not fit either in the types of ‘Design Build’ or ‘Operation and Maintenance Contract’. Additionally, since the private sector actors do not only finance the intervention, but, also bring the registration service, CLAP cannot be categorised under ‘Finance Only’. Moreover, the registry, asset or facility are not built, leased or transferred, so CLAP is not ‘Design, Build, Finance and Operate’, ‘Operate and Transfer’, ‘Lease, Develop and Operate’, ‘Build Lease, or ‘Build, Own, Operate and Transfer’. Whilst CLAP does relate partially to ‘Build, Own, Operate’, since the private sector partners were in charge of the end-to-end process, those actors do not take part in ownership transfer to the public sector, or permanent service, or administrative operations.

Whilst Meridia was (and is) responsible for collection, management, cleaning, processing and submission of data to the system, AFOR validates data and issues the land documents. No asset has been transferred between the public and private sectors.

CLAP cocoa sector members provided direct investment in land documentation. The private land firm was responsible for improving and innovating processes and the overall service delivery based on the FFPLA approach. The firm held a contract with the local government and both sectors cooperated to improve the service, execute projects, reduce administrative costs and increase efficiency of rural land registration. The government also facilitated engagement with other authorities.

Based on this formula, it can be recognised that the private sector engagement in CLAP was high, moving from management or operational contracts, leases or concessions, to a more hybrid PPP types between ‘partial divestiture of public assets’, ‘joint venture’ and ‘full private sector divestiture’ [

10]. However, it cannot be considered as any of those categories solely, and can be best described as a new model that fits the purpose.

When compared with other cases, this case varies in terms of funding. CLAP projects included two main components: land documentation delivery and technical assistance. The financial model was a mixed set up where land registration was paid by the private sector actors and users (80/20% of the costs of documents, respectively)

11. Revenue from land documentation went to the private land service provider and local private surveyors sub-contracted. These payments for land documentation represented 60% of the total project cost. Then, contributions from donors leveraged the other 40% to cover technical assistance, development-focused actions needed, capacity-building for community land governance institutions, and other project costs. For example, the contribution was dedicated to organisations from the civil society supporting activities in the community and participatory processes, and any work required for context exploration and attention to social issues in the communities. In general, capacity-development was financed by both private sector actors and donors. The government held a contract with the private land service provider (as manager of the partnership and representing all partners) to work together in improving services for rural communities and contributing internal capacity for joint technical activities and final issuance of land documents. Overall, this scheme can be replicated in any other sector or context.

4.2.5. Data, Innovation, Processes and Technologies

Two central aspects found in the technical approach are worthy of mention: adaptability and replicability. As the approach followed the configuration of existing legitimate rights it can be adapted to register different tenure types as long as the registration approach complies with the legal requirements and regulations set by the law. The tools applied can be adapted to the accuracy required and integrated to other systems—including the national land administration system and existing government data. Use can also be made of the National Reference System, parcel monuments and use of Continuously Operating Reference Stations (CORS). Also, different alternatives of registration and ‘smart’ surveying tools are available, particularly for use in mass operations where digitisation, technology and processes interrelate. Those tools can be used by professionals and non-professionals. Community members, including women, can collect data, if trained technically. However, just as with other digital tools, digital illiteracy in combination with technology can imply a first layer of exclusion for some individuals. Data goes through seamless data processing and certified local surveyors and authorities can use the tools (backoffice) to fully validate data once submitted to the land administration system. Then, authorities approve applications and issues the respective land documents.

4.2.6. Gender and Vulnerable Group Sensitivity

Specifically, in relation to tenure insecurity, the CLAP model entailed attention to vulnerable groups through affordability approaches such as tailored subsidies. The finance model vested the major part of the cost in companies’ payment. It aimed to first reduce the cost of a sole land certificate by more than 10 to 15 times: further funding was used to subsidise up to 80% of the total cost of documents to make those affordable for smallholders within the cocoa supply chains.

Then, as higher volumes drive the cost down at scale, it was (and is) expected that smallholders’ contributions will increase over time, without depending mainly on external funding. If the model is successful, the outcome would be an alternative for affordable documentation filling the gaps after PAMOFOR concludes.

The partnership can contribute to addressing the Ivorian Government’s financial gap, reducing costs along lands involved in cocoa supply chains, and bringing efficient land administration service delivery [

23]. In return, some of the benefits for the companies engaging in this can be an overall strengthening of the land security of farmers within their supply chains.

The method also facilitates joint documentation for families to secure not only the farmer, who is often a male, but also secure the rights of female spouses (or other members of the family) by also recording their name in the land documents. In addition, sensitization activities in the process included discussions with women and specific vulnerable groups (e.g., youth, migrants), with a view to seeking to make their voices heard.

4.2.7. CLAP, PPP, FFPLA, and FELA

As explained in

Figure 2 below, the PPP analysed enabled the creation of a FFPLA solution for Côte d’Ivoire. This solution then allowed for alternative service delivery. Both the PPP model and the service may evolve over time informed by the early scale efforts.

Table 1 presents the detailed key distinguishing features of the CLAP FFPLA PPP against the nine strategic pathways (SP) of FELA. FELA’s nine strategic pathways provide an overarching guide for an overall summary of key features.

5. Discussion

Having presented the core results from the Côte d’Ivoire case study, a discussion is undertaken with regards to (i) the potential benefits and advantages of the CLAP model (with respect to other PPPs), (ii) the potential challenges with the approach, (iii) the generalisation/adaptability of the model more generally; and (iv) the future ahead for the specific case.

5.1. Potential Benefits and Advantages

CLAP serves as a novel reference for more innovative PPP models to transit from traditional land administration PPPs to FFPLA PPPs, and enable more active engagement of the private sector in improving land tenure governance from social responsibility and sustainability perspectives.

CLAP is a relatively new partnership, for which early implementation started in 2021. Despite no further empirical evidence being able to be offered at this point, the potential benefits of the model can be already perceived in the creation of a FFPLA PPP framework, utilising the FELA, that merges efforts and objectives from a non-common group of actors, who do not naturally interact in the land space (at the funding and execution levels). It provides broader support to the government without it needing to depend on donor funding solely.

For governments, this type of partnership may allow for operational flexibility. While CLAP focuses on cocoa farming areas, the government can still orient public resources and donor funding to other areas. Although, it is yet unknown how both services will co-exist, the commercial approach by CLAP tests an alternative and appears an affordable choice for smallholders.

CLAP as a PPP entails cooperation between the public sector, both through the local government and governments, from donor countries and the private sector. The partnership is formalised through contracts

16, and; cooperation with non-governmental organisations, and offers the possibility to cooperate with other different civil society institutes and foundations.

Other novelties are found in the focus on a certain commodity value chains; re-thinking the financial streams for funding land administration, applying the FFPLA approach in developing countries; the sector-oriented attention to the poor and social needs, and; the interaction of non-conventional actors when driven by the private sector (outside traditional land sector actors), supported by government, compatible with international development agencies, and managed by a land rights documentation private company.

CLAP as a FFPLA PPP adds purpose and flexibility to land registration services, provides possibilities for multiple context-specific developments for scaling, and drives service delivery through technological approaches. It further facilitates attention to wome—e.g., facilitation of joint documentation with the name of women recorded on land documents—and vulnerable groups, as mandated by corporate sustainability ambitions.

5.2. Challenges and Limitations

At the social and political levels, any lack of commitment from government, community leadership would challenge land tenure interventions under a PPP like CLAP. The same applies to cooperatives, since they are at the heart of value-chain implementations.

At the financial level, funding is still an aspect to pay attention to. The finance availability in this FFPLA PPP may be still influenced by the number of companies engaging in the partnership and their contributions and the extent of donor funding leveraging. Similar to the situation of the governments’ lack of funding, companies alone may not be able to allocate the necessary budget for systematic registration either. Without leveraging sufficient co-funding from other actors, it may be difficult to navigate how the FFPLA-focused services can be delivered systematically in the communities. Though it should be again noted, any financial risks are mostly shared by the private sector partners, in terms of investment and revenue, and by the beneficiaries in terms of sharing the service cost. Similarly, the level of community acceptance and demand for land tenure interventions may enable or limit projects under this type of PPP financially and socially.

It also must be recognised that dependence on private funding by private companies could also potentially present drawbacks, and needs to be further explored in future discussions.

On the other hand, continuing cooperation with donors is important to guarantee funding for technical assistance, but, the risk of ‘competing’ with other future free documentation programmes for donor funding must be considered.

At the technical level, as Côte d’Ivoire is still setting up its land administration system, CLAP may still depend to a certain extent on the government progress if traditional methods dominate the national approach. In order to sustain the efficiency of the process, projects would rely on technology and digital processes to overcome any delays of the land administration system being developed in PAMOFOR. Even if the system is not fully in place, implementation can continue as long as the private land firm provides the service, manages the hybrid methods, and maintains data digitally, until the integration with the national system can be done.

Overall, improvements to CLAP processes will need to be a constant. Also, due to the early stage of the CLAP pilot project, issues such as the sustainability of the model and relationship to the national efforts cannot be fully assessed yet. A deeper evaluation of the PPP may be possible only in later stages.

5.3. Generalisation and Adaptability

Whereas CLAP has been developed for Côte d’Ivoire, the aim is for replicability to other contexts. Transfer to other contexts is possible as long as social, legal and institutional environments allow it, and technological innovations are adjusted to the local context. Nevertheless, not only the advantages but also challenges at different levels may be transferred too.

In the end, the blueprint developed by CLAP will inform future innovations and partnerships about opportunities and success elements. It is worth to continue investigating how CLAP develops, from a pioneering model to potentially a mature partnership.

Similarly, it may be relevant for other cases to monitor the outcomes and evidence gathered in the following years as the CLAP land registration project progresses. The flexibility of CLAP can be expected to allow more actors to join the PPP and so develop expansion possibilities. In a future scenario, two important steps for CLAP would be important: to ensure a future integration with other value chains through a more systematic land registration, as well as to continue working with the government and donors to fulfil existing gaps. The CLAP model also allows the opportunity for donors to experiment with innovative collaborations with the private sector in land administration, outside the traditional PPPs.

It is yet unknown if and how the broader industry or broader sectors may embrace a FFPLA PPP. However, considering the current interest and local acceptance of the early scale project by cocoa farming communities, the government, the private sector actors and generally all the stakeholders involved, the authors argue that a FFPLA PPP such as CLAP may lead to strengthening actions by the private sector across different sectors to support the achievement of the SDGs. Promising, as well, is the realisation of the potential of multi-stakeholder cooperation through partnerships (SDG 17) and the impact of the private sector in securing land rights.

5.4. Looking Ahead

Whilst a longitudinal study will be required to further assess the long-term validity and added value of the CLAP model, at this moment, the most important preliminary key success factor to highlight is political will and a long-term commitment from all parties. Especially the political-will of customary landowners, local village land management committees and the local government and community leaderships can be considered a preliminary key success factor for the model. Even though the duration of this CLAP model is relatively still short (3 years), in comparison to other cases (with a 10 year or longer period), this type of industry-based partnerships requires a long-term commitment from all actors involved and continuous budget allocation. This support will depend directly on the focus on land rights within the corporate sustainability agendas, which can be considered as a relatively pioneering focus in this contemporary period, but is likely to increase in the future.

This FFPLA PPP provides the private and public sectors with an alternative to document land for farmers or the agricultural sector. Especially relevant for private companies is to integrate this type of effort within the supply chains, and to explore the potential of securing investment in farmers and land, the ability to strengthen existing sustainability/social programming, and the potential of obtaining an overall return on investment.

Overall, this PPP type offers one way of involving other sectors to land registration processes within the country, or experimenting in other contexts. This can further benefit other government entities such as those responsible for taxation, infrastructure planning and development, rural development and agriculture.

There is also an opportunity that the scaling up of the project volume drives the cost of documentation down, as dependencies on private investment are reducing. Hence, documents continue to be affordable to smallholders and less subsidies will be required. This aspect reduces the possibility of costs increases later on, which often represents a disadvantage for PPPs.

6. Conclusions

This paper sought to introduce a new form of PPP to the FFPLA literature, by expanding the discourse on PPPs in land administration and focusing specifically on their role in FFPLA initiatives, and more specifically exploring the role of non-conventional land administration sector actors. These actors, for example, global food and agricultural corporations, are typically not directly involved in land administration interventions, but, for corporate social responsibility objectives, are intrinsically reliant upon it. Closer embedding of these actors into land administration interventions were suggested as having the potential to unlock the financial capacities of those organisations, making them available for national government-led land administration initiatives, that often lack sustainable funding mechanisms.

The work therefore commenced from the premise that increased corporate-style partnerships may also further facilitate the implementation of FFPLA—because, anecdotally, major funding is required by governments to implement FFPLA—and donor interventions would not be sufficient after projects end. The background review confirmed this notion, finding that whilst public-private partnerships have long standing use in land administration, there is room to explore innovation of partnerships with an increased involvement of non-conventional private sector actors in certain roles and activities.

The case study methodology was applied to review the recent developments of FFPLA in Côte d’Ivoire through a partnership between the government and a consortium of companies. The results showed that the CLAP approach brought novelty to PPPs in FFPLA in terms of actors, roles, the financing model, and the specific use of the FFPLA technical approach. That said, it was recognised that a longitudinal study would be needed to fully assess the validity and sustainability of the approach. Preliminary key success factors, like all land administration interventions included the importance of high-level political will (from government and communities) and long-term stability surrounding land access and availability for the corporate actors. Another factor that would protect land tenure interventions is the government’s capacity to incorporate the demand and applications from the partnership projects into their national registry in order to sustain the efficiency of the process.

In terms of generalisation possibilities and future developments, it was found that the innovative partnership may create new avenues for financing FFPLA in developing countries and for more active forms of participation of the corporate. Results from the case study are considered preliminary and even though achievements and impact cannot be fully defined until the approach is scaled up, the type of partnership studied can be considered novel in terms of design, requirements and implementation. The model potentially creates a long lasting and sustainable buy-in from private sector corporations, who whilst not conventionally closely tied to land administration efforts, rely intrinsically on it to achieve corporate social responsibility objectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.-M., S.U. and E.-M.U.; methodology, A.G.-M. and E.-M.U.; formal analysis, A.G.-M., E.-M.U. and R.M.B.; investigation, A.G.-M. and S.U.; writing, A.G.-M., S.U., E.-M.U. and R.M.B.; original draft preparation, A.G.-M., E.-M.U. and R.M.B.; data collection, A.G.-M. and S.U.; writing—review and editing, E.-M.U. and R.M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The funding for the publication costs for this article were kindly provided by the School of Land Administration Studies, Faculty ITC from the University of Twente, in combination with Kadaster International, The Netherlands.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the journal editors and guest editors of the Special Issue “Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration—Providing Secure Land Rights at Scale” for their support and the granting of funding covering the fees related to the publishing of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The first and second authors mentioned at the beginning of the manuscript declare their direct involvement in the PPP case presented in this paper. The funders of this article had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Notes

| 1 | Specifically, SDGs: 1 No Poverty, with the target 1.4; 2 Zero Hunger, with the target 2.3; 5 Gender Equality, with the target 5.a, and; 15 Life on Land with the target 15.2. |

| 2 | The term ‘smallholder’ varies across countries under different criteria. The definition used in this paper for reference is “..a farmer (producing crop or livestock) practicing a mix of commercial and subsistence production…, where family provides the majority of labour and the farm provides the principal source of income”. |

| 3 | ‘International community’, refers to global governance and multilateral entities such as the World Bank, and international development and cooperation agencies such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). |

| 4 | Including improvement of the delivery of land administration services, introduction of innovations such as online applications and payments, simplification of procedures and better customer experience, reduction of the time for transactions, increasing revenue for the government agency in charge, and contributing to efficient e-Government platforms. |

| 5 | Land titles are the final formal document proving the permanent conversion of land rights to property rights. Land certificates prove registered ownership rights over land and plots, and are the document which can be converted to titles. Land use contracts are community-managed formalised agreements between customary owners and occupants. Indeed, tenancy contracts are the most common agreement that have allowed non-landowner cocoa farmers to access to land and their application may be key in conflict prevention in Côte d’Ivoire. |

| 6 | 6421 out of 1,500,000 land certificates aimed by the government. |

| 7 | Referring to the DP3 and DP4 projects partly funded by the European Union debt swap programmes (Devis-Programme, or DP). |

| 8 | PAMOFOR also includes support to the government in aspects such as institutional capacity building and institutional systemic improvements. |

| 9 | In Ghana, costs of land titling documents were reduced from $400 to $100 EUR, the process for farmers was made easier and the delivery time shortened from 18 months to 8 weeks. |

| 10 | The region where the service model has been tested is Lôh-Djiboua. The service design phase was still running and conversations around the onboarding of one donor to the partnership was in process when this paper was written. |

| 11 | For the private sector actors, return on investment was expected in the productivity and sustainable sourcing dimensions across their supply chains. For the cocoa farmers, return on investment was expected to be figuratively in the form of sense of land security and any positive behavioural change that led to their welfare. Unless farmers who own land and receive documentation decided to use the document for immediate land transactions, for a direct economic return. |

| 12 | Referring to cocoa farmers who are landowners or to people owning land occupied by cocoa farmers. Both types of landowners can be beneficiaries of the project. |

| 13 | Most cocoa farmers are migrants who do not own the land they occupy. Therefore, in that situation they are land occupants/users. |

| 14 | In this FFPLA PPP, the private sector brings funding for covering 80 percent of the total cost. Smallholders pay the 20 percent left and the Government provides in-kind contributions at the same time while working with the land administration firm to reduce administrative costs. |

| 15 | These two processes mentioned are implemented by organisations from the civil society subcontracted for the projects. These activities are independent to any structural efforts by the government (through PAMOFOR) to communicate the national implementation of the Rural Land Law and rural land registration policies. |

| 16 | On behalf of the private partners in CLAP and as the main intervention executer, Meridia signs contracts with AFOR for land tenure projects under the partnership. The first contract of the PPP was the on-going pilot (at the time of writing) conducted in two villages of the country to test the service. |

References

- Musinguzi, M.; Enemark, S. A Fit-For-Purpose Approach to Land Administration in Africa: Supporting the global agenda. Int. J. Technosc. Dev. 2019, 4, 69–89. Available online: https://vbn.aau.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/318235502/2019_issue_Vol_4_Musinguzi_Enemark.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- Unger, E.M. Responsible Land Administration in Disaster Risk Management: Approaches for Modelling Integrated Governance and Policy Transfer of People, Land and Disasters. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 26 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enemark, S.; Bell, K.C.; Lemmen, C.H.J.; McLaren, R. Fit for Purpose Land Administration, No. 60; International Federation of Surveyors (FIG), The World Bank: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zevenbergen, J.A.; De Vries, W.; Bennett, R.M. (Eds.) Advances in Responsible Land Administration; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zevenbergen, J.A. Handling Land: Innovative tools for Land Governance and Secure Tenure: E-Book; UN-HABITAT, International Institute of Rural Reconstruction (IIRR), Global Land Tool Network (GLTN): Nairobi, Kenya, 2012; 152p, Available online: https://www.local2030.org/library/76/Handling-land,-Innovative-Tools-for-Land-Governance-and-Secure-Tenure.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Asiama, K.O. Responsible Consolidation of Customary Lands. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 17 April 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.; Masli, E.; Potel, J.; Unger, E.M.; Lemmen, C.H.J.; de Zeeuw, K. Cadastral Entrepreneurs Recognizing the Innovators of Sustainable Land Administration. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week 2019: Geospatial Information for a Smarter Life and Environmental Resilience, Hanoi, Vietnam, 24–26 April 2019; Available online: http://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2019/papers/ts02g/TS02G_bennett_masli_et_al_9950.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- FAO. Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security; Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2012; 40p, Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i2801e/i2801e.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2020).

- Bell, K. Global Experiences with Public Private Partnerships for Land Registry Services: A Critical Review; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Halid, N. Public-Private Partnerships in Land Administration: The Case of e-Tanah in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Public-Private Partnerships in Land Administration: Analytical and Operational Frameworks; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34072 (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Lavigne Delville, P.; Deininger, K.; Augustinus, C.; Enemark, S.; Munro-Faure, P. Registering and Administering Customary Land Rights: Can we deal with complexity. In Innovations in Land Rights Recognition, Administration and Governance; Deininger, K., Augustinus, C., Enemark, S., Munro-Faure, P., Eds.; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- UN-GGIM. Framework for Effective Land Administration: A reference for developing, reforming, renewing, strengthening, modernizing, and monitoring land administration. In Proceedings of the Tenth Session of the United Nations Committee of Experts on Global Geospatial Information Management (UN-GGIM), New York, NY, USA, 26–27 August–4 September 2020; Available online: https://ggim.un.org/meetings/GGIM-committee/10th-Session/documents/E-C.20-2020-29-Add_2-Framework-for-Effective-Land-Administration.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Enemark, S.; Mclaren, R.; Lemmen, C. Fit-For-Purpose Land Administration: Guiding Principles for Country Implementation; United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), Kadaster International, Global Land Tool Network (GLTN): Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; p. 118. Available online: https://gltn.net/download/fit-for-purpose-land-administration-guiding-principles-for-country-implementation/ (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Lemmen, C.; Unger, E.M.; Bennett, R. How Geospatial Surveying is Driving Land Administration: Latest innovations and developments. GIM Int. 2020, 34, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lengoiboni, M.; Richter, C.; Zevenbergen, J. Cross-cutting challenges to innovation in land tenure documentation. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulvund, S.; Unger, E.M.; Lemmen, C.; Van den Berg, C.; Wits, T.; Utami, R.D.; Lukman, H. Inclusive and Gender Aware Participatory Land Registration in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 2019 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty: Catalyzing Innovation, Washington, DC, USA, 25–29 March 2019; Available online: https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/inclusive-and-gender-aware-participatory-land-registration-in-ind (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Chandler, D. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: Sustainable Value Creation; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The Big Idea: Creating Shared Value. How to Reinvent Capitalism—and Unleash a Wave of Innovation and Growth. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, S.; Gulati, A. Globalization and the Smallholders: A Review of Issues, Approaches, and Implications; Markets and Structural Studies Division [Discussion Paper], 50; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pagiola, S. Economic Analysis of Rural Land Administraton Projects; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, I.; Enemark, S.; Wallace, J.; Rajabifard, A. Land Administration for Sustainable Development; ESRI Press Academic: Redland, AB, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tulder, R. Business and the Sustainable Development Goals: A Framework for Effective Corporate Involvement; Rotterdam Schoool of Management, Erasmus University: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, K.C. Focusing on Innovation and Sustainability in Rural and Urban Land Development: Experiences from World Bank Development Support for Land Reform; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- De Zeeuw, K.; Lemmen, C. Securing Land Rights for the World. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week 2015: From the Wisdom of the Ages to the Challenges of the Modern World, Sofia, Bulgaria, 17–21 May 2015; Available online: https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2015/papers/ts01b/TS01B_de_zeeuw_lemmen_7502_abs.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- World Bank. Public-Private Partnerships: Reference Guide Version 3; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29052 (accessed on 3 August 2020).

- Burns, T.; Wright, F.; Rickersey, K. How to Conceptualize a PPP for Land Administration Services: Understanding the private sector and commercial feasibility. In Proceedings of the 2020 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty: Institutions for Equity and Resilience, Washington, DC, USA, 16–20 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantari, M.; Paez, D.; Anand, A.; Burns, T.; Rickersey, K. A Review of Public-Private Partnerships in Land Administration. In Proceedings of the 2019 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty: Catalyzing Innovation, Washington, DC, USA, 25–29 March 2019; Available online: https://www.conftool.com/landandpoverty2019/index.php/04-11-Kalantari-625_paper.pdf?page=downloadPaper&filename=04-11-Kalantari-625_paper.pdf&form_id=625&form_version=final (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Tang, L.; Shen, Q.; Skitmore, M.; Cheng, E.W. Ranked Critical Factors in PPP Briefings. J. Manag. Eng. 2013, 29, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Datta, A. Public-Private Partnerships in India: A case for reform? Econ. Political Wkly. 2009, 44, 73–78. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25663449 (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Galilea, P.; Medda, F. Does the Political and economic Context Influence the Success of a Transport Project?: An analysis of transport public-private partnerships. Res. Transp. Econ. 2010, 30, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives, A.; Paris, A.M.; Benavides, J.; Raymond, P.D.; Quiroga, D.; Marcus, J. Financial Structring of Infrastructure Projects in Public- Private Partnerships: An Application to Water Projects; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Norfolk, S.; Quan, J.; Mullins, D. Options for Securing Tenure and Documenting Land Rights in Mozambique: A Land Policy & Practice Paper; LEGEND, Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich: Chatham, UK, 2020; Available online: https://images.agri-profocus.nl/upload/post/Moz_Policy_Paper1587375947.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Monteiro, J.; Inguane, A.; Oliveira, E.; Weber, M.; Palomino, D. Mapping Community Land In Mozambique: Opportunity and challenges for combining technology with good land governance. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty: Land Governance in an Interconnected World, Washington, DC, USA, 19–23 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Endo, V.; Pantoja, E.; Trevino, L. Contracting Out Services for Land Regularization: The new roles of the private sector in land administration. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty: Land Governance in an Interconnected World, Washington, DC, USA, 19–23 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Enemark, S.; McLaren, R.; Lemmen, C. Building Fit-For-Purpose Land Administration Systems: Guiding principles. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week 2016: Recovery from Disaster, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2–6 May 2016; International Federation of Surveyors: Copenhagen, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- GLTN. Handling Land: Innovative Tools for Land Governance and Secure Tenure; UN-Habitat, Global Land Tools Network and IIRR: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020; Available online: https://cepa.rmportal.net/Library/natural-resources/Handling%20Land%20-%20Innovative%20tools%20for%20land%20governance%20and%20secure%20tenure.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Boone, C.; Bado, P.; Dion, A.M.; Irigo, Z. Push, Pull, and Push-Back to Land Certification: Regional dynamics in pilot certification projects in Côte d’Ivoire. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2020. draft. [Google Scholar]

- François, K.N. Social constraints of rural land management in Côte d’Ivoire and legal contradictions. Int. J. Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 310–319. Available online: http://www.aessweb.com/pdf-files/IJASS,%202(3),PP.310-319.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Colin, J.P.; Kouamé, G.; Soro, D. Outside the Autochthon-Migrant Configuration: Access to land, land conflicts and inter-ethnic relationships in a former pioneer area of lower Côte d’Ivoire. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2007, 45, 33–59. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4486719?seq=1 (accessed on 10 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Augustinus, C.; Tempra, O. Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration in Violent Conflict Settings. Land J. 2021, 10, 139. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/10/2/139/htm (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- AFOR—La Consolidation des Droits Concedes. Available online: http://www.foncierural.ci/index.php/la-consolidation-des-droits-concedes (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Ruf, F.O. “You Weed and We’ll Share”: Land dividing contracts and cocoa booms in Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire and Indonesia. CIRAD/GTZ Surv. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.; Choudhury, P.R.; Haran, N.; Leshinsky, R. Decentralization as a Strategy to Scale Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration: An Indian Perspective on Institutional Challenges. Land J. 2021, 10, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koffi, M. Présentation du Projet d’Ámélioration et de Mise en Œuvre de la Politique Foncière Rurale de Côte d’Ivoire—(PAMOFOR); AFOR, World Cocoa Foundation: Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bymolt, R.; Laven, A.; Tyzler, M. Demystifying the Cocoa Sector in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire; The Royal Tropical Institute (KIT): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- AFOR. Manuel de Sécurisation Foncière: Opérations Intégrées; Ministere de L’Agriculture et du Developpement Rural: Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Côte d’Ivoire-Land Policy Improvement and Implementation Project (No. PIDISDSC18852, 1–14). 3 October 2017. Available online: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/823571509717469081/pdf/ITM00184-P157206-11-03-2017-1509717464849.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Paez, D.; Burns, T. Conceptual Design of a Private Investment Scorecard for Land Administration in Developing Countries. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty: Land governance in an Interconnected World, Washington, DC, USA, 19–23 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).