1. Introduction

This paper aims to analyze the financial and operational approach to land regularization and financing used in Brazil by an innovative private social enterprise called Terra Nova, in order to demonstrate that the approach widens the concept fit-for-purpose land regularization to include fit-for-purpose land financing. The feasibility of the approach has relevance for wider efforts in informal settlement regularization and upgrading.

First, the paper reviews the literature on informal settlement expansion and regularization. This review identifies the need for a broader set of approaches to informal settlement regularization given the continued proliferation of this type of settlement globally. The review also identifies financing for land and housing as a barrier which prevents regularization of informal settlements on a wider scale and impedes the linkage between informal and formal systems for urban services. Multiple observers have hypothesized that improved land financing is a key to resolving the challenge of informal settlement regularization. However, land financing for poor populations is challenging because of low and inconsistent incomes, and requires specific fit-for-purpose arrangements which traditional financing institutions have been reluctant to provide.

The paper then introduces the case of the private social enterprise Terra Nova and presents the central features of its bundled approach to land regularization and land financing, with emphasis on the ways in which the approach conforms to the principles of fit-for-purpose land regularization and land financing. In this approach, the enterprise acts as a coordinator and broker to organize the residents of informal settlements to regularize their settlements by negotiating buyouts of the underlying private owners at discounted values, handling titling and registration of the occupants, and coordinating with municipal governments to provide infrastructure.

The paper then presents empirical results about the performance of Terra Nova’s approach. The analysis of parcel-level repayment and price data provides evidence of the sustainability of the business model and increase of property values of the regularized parcels. The results presented from the enterprise’s own repayment data demonstrate that under (non-pandemic) historical conditions residents are largely able to pay an affordable monthly payment over 7–10 years to the enterprise for the service to purchase the plots and maintain the enterprise. In operation since 2001, the enterprise has regularized over 20,000 parcels in more than 30 settlements, primarily in the cities of Sao Paolo and Curitiba in Brazil.

The paper concludes that approach expands the toolkit of fit-for-purpose land administration to include the bundling together of fit-for-purpose land administration and land financing. The conclusion suggests that this bundled approach of fit-for-purpose land administration and land financing holds the potential to be replicable in many contexts and add to the set of options for regularizing informal settlements, especially when purchase of private land is required.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Urban Informal Settlements Pose a Global Challenge for Development

Urban population growth is arguably the biggest demographic trend of the last hundred years. Around the year 2000 more than half of the world population lived in urban areas. As of 2015, nearly 4 billion people—or 54 per cent of the world’s population—was urban, and the number was expected to reach 5 billion by 2030 [

1].

Much of the growing urban population is involved in the informal economy. The informal economy includes actors and activities “unregulated by the institutions of society in a legal and social environment in which similar activities are regulated” [

2]. The informal economy is a major provider of housing and livelihoods for large populations of urban workers in low-income countries [

3]. Approximately a billion people live in informal settlements or approximately 1 in 10 people globally, live in informal settlements [

4]. Their numbers are expected to continue to grow to about 2 billion people by 2030 [

1]. The prevalence of informal urban settlement is global. Fifty-nine percent of the urban population in sub-Saharan Africa lives in informal settlements, as does 28 percent of the urban population in Asia, and 21 percent of the urban population in Latin America and the Caribbean [

5].

The continuing prevalence of informal settlements as a predominant form of housing and urban services in low and middle-income countries is a major development challenge for urban growth. Informal settlement puts high social and economic burdens on residents and incurs large public costs. These burdens and costs include insecurity of tenure, lack of public services, stigmatization and discrimination by others including law enforcement, environmental and health hazards, inequitable civil rights, direct costs for local governments in upgrading programs and foregone revenues, and indirect costs when coping with other impacts of informality, such as public health (e.g., COVID-19), criminal violence, and related social problems [

6].

2.2. Regularization of Informal Settlements Has Been a Global Development Policy Priority for Decades, but Regularization Has Fallen behind the Growth of New Informal Settlements

Informal settlements are perpetuated due to high land costs in comparison to incomes, exclusion from access to credit for low-income groups, and insufficient affordable housing options in the formal sector (i.e., housing in comformity with planning requirements and property rights recognized by land administration authorities) [

3]. Regularization of informal settlements has been characterized as a “perpetual problem” without a no sufficient policy or market response [

7,

8,

9]. As global population growth and urbanization has increased during the second half of the 20th century and first decades of the 21st century, the issue of informal settlement regularization has been a continual focus of international development policy concern and targeting for decades, featuring in the Millenium Development Goals, the, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) goals (principally goal 11), and New Urban Agenda.

Over the years, policy and programmatic responses to informal settlement regularization by national and municipal governments, international development partners, and non-governmental and community-based organizations have resulted in some relative improvements in conditions but not in absolute numbers. The proportion of the urban population living in slums (i.e., informal settlements with the worst living conditions) worldwide fell from 28 percent in 2000 to 23 percent in 2014. Despite this improvement in the relative proportion of the informal settlement population, however, the absolute number of residents of informal settlements has continued to grow in the face of accelerating urbanization, population growth, and lack of appropriate land and housing alternatives. In 2014, an estimated 880 million urban residents lived in slums, compared to 792 million in 2000 [

10].

Commenting on the lack of achievement of the goals of informal settlement in the Millenium Development Goals, Durand-Lesserve [

11] observes policy failure at the level of governments and the lack of success in integrating informal markets for land and housing with formal markets in the following way:

The global rise of urban poverty and insecure occupancy status is taking place in a context […] of massive government disengagement from the urban and housing sector. Attempts to integrate informal markets—including land and housing markets—within the sphere of the formal market economy, especially through large-scale land ownership registration and titling programs, along with the lack of, or inefficiency of, safety net programs and poverty alleviation policies, have resulted in increased inequalities in the distribution of wealth and resources at all levels. In most countries, the public sector no longer contributes to the provision of serviced land or housing for low-income groups. Furthermore, the private sector targets its land and housing development activities at high-income and middle-income groups with regular employment and access to formal credit [

11].

In 2015 the Millennium Development Goals were replaced by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG 11 aims to ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums (Target 11.1, Indicator 11.1.1) [

10]. By making informal settlement regularization and SDG target, the UN member states sought to elevate the issue to the top priority of development policy action. As of 2020, progress on SDG 11.1 was deteriorating, with the COVID-19 pandemic contributing to an increase in the absolute number of people in informal settlements. The increase was most acute in Northern Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and in Western Asia [

12].

Echoing the Millennium Development Goals and the SDGs, The New Urban Agenda, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2016, aims a specific agenda item at informal settlements, calling for strategies for their prevention, regularization, upgrading, and monitoring [

13].

In spite of the high priority accorded to informal settlements in these long-standing global development agendas and similar national development agendas, analysts like Millington and Cleland [

14] have observed that despite 50 years of efforts, the growth of slums and informal settlements is increasing, particularly in developing countries, and the total number of slum dwellers has increased, undermining the ability of cities in developing countries to economically grow, prosper, and generate wealth for all inhabitants.

2.3. Models for the Prevention or Regularization of Informal Settlements That Can Keep up with Demand Have Been Inadequate

Given the longstanding and globally-prioritized problem of informal settlement proliferation and inadequate regularization, it is relevant to ask why the problem has been so intractable by conventional policies. Measures to address the problems of informal settlements in developing countries have had several different areas of emphasis over the last 20 years. Some measures have emphasized physical upgrading of settlements, others provision of housing subsidy [

7], clearing of informal settlements and relocating of the residents to public housing, as well as participatory regularization and attempts at addressing market imperfections [

15]. Observers have noted low levels of awareness about the ongoing housing and infrastructure needs settlements by policymakers, and their tendency to underprioritize and poorly understand the dimensions of settlement rehabilitation [

16].

In many situations, neither public bodies nor formal markets are able to respond to rapid urbanization quickly enough to with sufficiently priced housing to pre-empt informal settlement by channeling housing demand into formal pathways. New residents arrive to cities more rapidly and with less ability to pay than formal-sector arrangements can offer.

Most public jurisdictions do not have the planning and financing tools to deal with the rapid urbanization, or the tools in place are not sufficiently responsive to the reality on the ground [

17]. For example, Tellman, et.al. [

3] note that in Mexico City, “regularization is a complex, multi-institutional process, dependent on land tenure type and location, taking anywhere from 5 to 20 years. Many communities are never regularized due to this long and convoluted process. Informal urbanization has outpaced regularization” [

3]. The World Bank notes that globally, “narrowly-focused, neighborhood-level slum upgrading interventions, while generally effective, have fallen short of addressing the magnitude and scope of expanding informality and slums” and that the output of informal settlement regularization projects has been minimal when compared to the growing slum population worldwide [

18].

2.4. Financing Land Regularization and Acquisition through Private Sector-Led Approaches Has Been Hypothesized to Address Many of the Weaknesses in Models of Informal Settlement Regularization

In low-income countries the financial sector frequently filters out the informal urban population from access to its products and services such as housing mortgages due to perceived high risks and low returns [

15]. The financial sector perceives risks of non-payment, delinquency, and default because land and housing of the informal settlement itself cannot be used as a collateral, household savings are often small or non-existent and incomes are irregular. The financial sector also perceives low returns because of the low relative property values and long payback horizons compared to other market segments.

In theory, incentives and legal measures provided by the public sector should be able to bridge the financing gap created by these risks and induce private sector involvement in housing provision. However, the track record of such financial strategies, both those aimed at existing informal settlements and at new social housing, is weak due to misalignment of incentives by developers and government, and land cost itself [

19]. The experience of Brazil’s Minha Casa Minha Vida program, for example, which has provided a variety of public credits, subsidies, and guarantees for private developers and contracted over 3 million housing units since 2009, shows high delinquency of repayment (28 percent), abandonment of housing due to undesirable locations and moral hazard in the management of the program resulting in high costs for land and construction [

20].

Strategies such as loan guarantees or social funding, modeled on microfinance ideas, at the lower end of the market have been called for by observers of these issues [

15]. For example, Nzau and Trillo [

19] conclude their review of informal settlement upgrading with the observation that, while public-sector driven attempts to provide decent housing to slum residents in developing countries have either failed or achieved minimal output when compared to the growing slum population, these countries exhibit vibrant real estate markets that may hold the potential to bear the costs of regenerating informal settlements.

Based on these conclusions about the inadequacy of public sector led responses to informal settlements’ needs for regularization, Nzau and Trillo [

19] call for private-sector or public-private partnerships and focus on the need for engaging private sector developers by attracting their finances and expertise, in other words, fit-for-purpose land financing. They note that in many urban areas the real estate market is vibrant and highly dynamic and may hold the potential of bearing the costs of regenerating slums through the value increase from regularization and upgrading which can be shared by owner-occupants, private sector actors and the public sector [

19]. However, they maintain that little has been explored in the way public–private-based approaches to develop a market-driven processes for informal settlement regularization. They speculate that this lack of experiences may be due to the limitations of the social construct or social cohesion in informal settlements which could also be understood as coordination failures [

19]. Similarly, UN has also called for participatory and inclusive approaches that explore new innovative and effective financing avenues for land regularization and financing of land and infrastructure acquisition. [

21]

Ward et al. [

16] also call for new financing mechanisms (mortgages, etc.) to facilitate property sales for informal settlement upgrading, including buy-outs by inheritors and other stakeholders. In this call for action, governmental and private sector actors are envisioned to support provision of micro credits for home improvement and rehabilitation, linked to financial assistance to promote clean titles among stakeholders in order to leverage loans and financing [

16].

3. Fit-for-Purpose Solutions

3.1. Taken as Whole This Review of the Literature on Informal Settlement Regularization and Upgrading Identifies a Need for Fit-for-Purpose Solutions Which Bundle Land Regularization and Land Financing Together in a Package to Resolve the Needs of Residents

The above literature demonstrates the need to solve critical land financing imperfections in the relationship of informal settlements to private land markets and property rights. The discussion above identifies a need or gap for private sector-led or public-private partnerships to leverage land markets and land values in the regularization and upgrading of informal settlements. The identification of the need to provide this type of service within a number of constraints linked to affordability and tenure security can be viewed as a search for fit-for-purpose land regularization bundled together with fit-for-purpose land financing. This implies the need to establish new categories of land market transactions which are based on the ability of occupants of informal settlements to pay, which recognize the ‘sunk capital’ or ‘fact-on-the-ground’ of existing occupation, and the potential for security of tenure and value increases to support a stream of payments for land regularization and financing services.

However, in most situations where urban land value is expected to increase over time, the notional expected market price will still be above the reservation price or maximum willingness to pay of low-income occupants. This situation has been referred to as the “fundamental financing problem of the poor” [

22]. Therefore, a negotiated, “adjusted discount price” may be required to buy out a prior owner whose land is occupied by an informal settlement. Creating the conditions to manage and consolidate these types of market transactions via coordination of the informal settlement residents and negotiation with the underlying land owner, can be viewed as fit-for-purpose land financing.

Fit-for-purpose land financing for informal settlements is a natural extension of fit-for-purpose land administration. Fit-for-purpose land administration means applying the spatial, legal, and institutional methodologies that are most fit for the purpose of providing secure tenure for all, usually meaning they are low-cost, technologically accessible, and precise enough for the needs of the land boundaries in question [

23]. In the context of informal settlements fit-for-purpose land administration implies bringing together the advantages of formality (legal security, ability to access infrastructure and public services), with the advantages of informality (affordability, accessibility, adaptability).

As the above discussion has demonstrated, provision of the mechanisms for financing of land acquisition, and infrastructure bundled together with land regularization may be one of the missing elements for addressing regularization and upgrading of informal settlements at a wider scale. Such mechanisms potentially can create ‘bridges’ between informal settlements and formal property markets by connecting the low-income market segment of informal, self-built housing with formal property markets and financial institutions, and bring the settlement into a position to receive and pay for municipal infrastructure.

Financing of land acquisition and infrastructure is often a key missing element of informal settlement upgrading, and it is therefore valuable to identify cases in which land regularization and land financing are bundled together as a fit-for-purpose response [

19]. The idea of bundling regularization and financing together appears to be an important innovation to enable the informal settlement regularization within a reasonable time and at affordable costs. The paper now turns to the relevance of these concepts in Brazil, and focuses on an innovative, private sector social enterprise which puts these principles into action.

3.2. The Need for Fit-for-Purpose Bundled Land Regularization and Land Financing Is Acute in Brazil

Addressing the financing element is central to Brazil’s challenge to regularize tenure and upgrade urban services for informal settlements. As Brazil urbanized, going from 37 percent urban in 1950 to 86 percent urban in 2018, informal settlements of self-built housing filled the gap for affordable housing and access to urban space for large segments of the population. Informal settlements in Brazil are typically comprised of self-built housing constructed by semi-organized groups on unoccupied land, either on the urban periphery or in less favorable building sites within urban agglomerations, such as the slopes of hills. Although some informal settlements in Brazil occupy public land, most are built on land with an underlying private owner. The fact of underlying private ownership makes regularization of informal settlements in Brazil financially demanding due to requirements for expropriation with compensation to the private owner, as well as payment of the costs of preparing urbanization plans and legal procedures to title regularized parcels. Before the informal parcels and structures can be regularized (i.e., parcels and occupants recognized through regular titles of ownership and the settlement incorporated into municipal service arrangement for roads, water, and sewerage), the underlying private land must be acquired from the original owner with due compensation, and an urbanization plan accepted by the municipal government.

These situations generally create long-term impasses with high costs to residents, underlying landowners, and local governments. Residents of informal settlements on private land and the underlying owners in Brazil often become trapped in a type of ad hoc unresolved arrangement in which residents occupy land but do not have access to land titles, while owners hold legal title but have no ability to use or dispose of the land.

Evictions of informal settlement residents by underlying private landowners are also costly and contentious. Landowners must undergo costly and lengthy legal processes to evict informal settlement dwellers. Even if successful in legally recovering the land, the underlying private owners still have to cover the costs of reconfiguration, infrastructure, and overdue taxes. Meanwhile, informal occupants live under the threat of forced evictions, without formal infrastructure and in social exclusion from education, health, and postal services. Local government receives no tax collection on the informally occupied areas and is burdened by low-quality urban surroundings.

In the next sections, we examine how these issues are being resolved through a private-sector-led experience in Brazil, with the aim of analyzing its fit-for-purpose qualities which could make it relevant for replication in a wider set of contexts, especially for the financing of land acquisition and infrastructure.

4. The Terra Nova Case

4.1. An Innovative Private Sector Social Enterprise Called Terra Nova Is Bundling Land Regularization and Financing for Informal Settlement Upgrading in Brazil

The Brazilian private social enterprise Terra Nova takes a new approach to solving the financing problem of informal settlements in Brazil which overcomes the low-income land financing gap and can be viewed as a fit-for-purpose bundling of land regularization and land financing for informal settlement regularization and upgrading.

Terra Nova began as a family-owned business begun in 2001 by two brothers, Andre and Daniel Albuquerque, with experience in dispute resolution. Originally, the business worked as an advocate with community associations to lobby authorities to invest in infrastructure and services for informal settlements. This evolved into mediating agreements between landowners and associations representing residents in which the land would be expropriated by municipal or state government and compensation paid to the underlying private owner by Terra Nova in installments based on streams of payments from residents, under an agreement ratified by a court order. Terra Nova would restructure the settlement’s spatial plan to permit municipal infrastructure, document and map each individual parcel, supervise execution of contracts and manage payments, earning revenue from a retained share of the installment payments made by the residents. As individual residents completed payments, full ownership title was provided to them. Municipal governments in turn provided infrastructure to the regularized settlements. Legal title and infrastructure raised property values and made the properties marketable.

The value of informal settlement regularization is high. It has been estimated that the value of all private land under dispute in Brazil was R

$15 billion, with the potential of the land value to reach R

$45 billion once areas were regularized and received infrastructure [

24].

The evidence from Terra Nova’s experience suggests that a private entity can help resolve this problem by creating a coordination mechanism that is able to negotiate and mediate between informal settlement residents and private owners to reach a solution to the financing problem. The historical performance of the enterprise demonstrates that this approach is feasible (‘feasible’ here is defined as having the ability to achieve the objective of regularization over a sustained period of time and an expanding base of settlements without external subsidy at levels of affordability which enable low-income residents to pay for the regularization process themselves at a level which is manageable within their household budgets) from both financial and social points of view and is able to overcome the fundamental financing problem in two critical ways. From the residents’ payment side, it solves the problem of coordination of individual residents by aggregating residents’ payments. It solves the affordability problem by stretching the period of repayments to 7–10 years, which allows for monthly payments which do not restrict consumption beneath residents’ subsistence threshold. From the land price side, discounted purchase prices are arranged which reduce the sales price below prevailing market rates, to levels which are likely closer to the owners’ true reservation price for the occupied site.

Terra Nova typically enters when the ad hoc unresolved legal status generates a conflict over the land, creating an opportunity to broker an agreement between the parties to purchase and compensate the land from the underlying private owner. Terra Nova simultaneously coordinates the residents to enter into contracts with Terra Nova to pay for the land compensation and the regularization procedure, and with the underlying private owner to accept a stream of payments for the overall compensation. Terra Nova then maintains both the collection and the payment accounts over a period of time, using local and federal regulation and government titling mechanisms to fully legalize and include the settlements into formally provided municipal services.

As an intermediary, Terra Nova negotiates a compensation price at which landowners will agree to sell (typically at a discount of 20–40 percent below comparable market prices) and informal residents can afford to buy. The purchase is made by low monthly installment payments over a 7–10-year period adjusted to affordability determined by a social evaluation of the settlement. Local authorities provide the verified land title to Terra Nova after acquisition of the land and Terra Nova provides title to residents after the full stream of payments is completed.

With this fit-for-purpose model for regularization and financing of informal settlements as a bundled package, Terra Nova empowers community associations and facilitates authorities to invest in basic infrastructure and services for the underserved areas. Since 2001, Terra Nova has received judicial approval to regularize 30 areas with about 20,000 occupants in total and 3 million square meters of housing stock. It has facilitated the installation of 21 km of water and energy networks, 12 km of sewage networks and 19 km of paved roads. The enterprise has also facilitated the construction of four schools, eight daycare centers, five health care centers, five social assistance centers, and 18 recreational facilities. Since 2012, residents’ payments had grown eightfold, and net revenues of the enterprise reaching R

$1.9 million in 2018 [

24].

4.2. Terra Nova’s Model Adapts Traditional Land Purchase Arrangements for the Low-Income Population in a Fit-for-Purpose Manner in Which Payment Requirements Are Adapted to the Capacities of Residents, and the Price of Compensation to the Original Landowners Is Also Negotiated

In this way Terra Nova’s model can be viewed as a type of fit-for-purpose land financing, distinct from both traditional commercial financing, and from subsidized public financing.

The initial step is to reach an agreement with the informal settlement population to carry out the regularization process. This is facilitated by community neighborhood associations discussing the regularization plan and terms with residents. It is necessary to have the agreement of a minimum of 75 percent of the households in a settlement to ensure the financial stability of the compensation arrangement. A parcel map and upgraded land use map for the post-regularization street and social infrastructure lay-out is prepared. Usually, the process of reaching agreement with the community members takes 30–60 days of meetings and, in some cases, door-to-door discussions with individual residents. In some large communities, factions among residents, conflicts of interest, and organized groups may oppose the regularization project. In these cases, Terra Nova either has to withdraw or facilitate a leadership change among the community.

Working with the local neighborhood association, Terra Nova’s staff carries out a social assessment to estimate the payment capacity of the residents, prior to negotiation with the landowners about compensation. In the social assessment the household is interviewed to determine its sources of incomes, the stability of those sources (most often in the informal sectors), and the household’s expenditures. Checks are made with local references to ensure the veracity of the information. The target for the monthly installments to be paid by residents is approximately 30 percent of the one individual’s minimum salary. Depending on the capacity to pay and the negotiated land price, these monthly instalments are typically paid for 7–10 years (at IPCA + 4% or ~9% p.a.), agreed to in an individual contract made directly between Terra Nova and the resident Currently, the average instalments are R$ 250–350 per month per household.

At the same time, Terra Nova makes an assessment of the land value and enters into a negotiation with the landowner for a compensation arrangement. Typically, this is a discounted market price, to be paid over a 7-to-10-year period as a compensation contract by Terra Nova to the landowner. The municipal government then expropriates the land from the landowner. In most of the settlements regularized to date, the original landowner receives 60–65% of the monthly payments from the overall stream of payments from residents. Terra Nova receives 30–35% for its staff and services. Lawyers and community-owed Social Funds receive 5%. The median land value for contracted parcels is R$ 7400 (constant 2010 Reals) and the median lot size, which includes shared common areas such as walkways, is 175 square meters.

Terra Nova’s property titling process, the duration of the payment process is based upon 10 years of affordable monthly payments for a favela resident to acquire the property title but may be advanced to as few as seven years depending on the payment capacity of residents and the cost of the land acquisition.

Along with this focus on adaptability and affordability, other fit-for-purpose factors are present in the regularization and financing model. The project identification and selection process is rigorous and restrictive; only when residents, the landowner, and the municipal government are all in agreement can the process be carried out. This means that strong relationships with local bodies and municipalities have to be maintained at all times. Terra Nova uses only highly experienced negotiators with deep expertise in legal matters to work out a win-win solution for all stakeholders. Terra Nova has to accurately assess the payment capacity of residents. It also employs a strong technological backbone to track individual payments in from residents and payments out to landowners and has a robust delinquency assessment [

24]

5. Evidence of Performance

5.1. Materials and Methods

This section presents evidence about the performance of the approach over time from the case study of Terra Nova. The evidence presented aims to show two basic performance indicators of the viability of the social enterprise over time: (1) sufficient payments with low-enough delinquency rates to maintain the business in operation and achieve formalization for landholders; and (2) increases in land value of the regularized land parcels.

The dataset used for this study represents all financial transactions and obligations between Terra Nova and residents from 2000 to 2019. There are a total of 8193 contracts (which correspond to 7103 lots and 7414 occupants) in the dataset. We also analyze a subset of lots pertaining to Paraná state (4527 lots, 5388 contracts, and 4990 occupants) since Terra Nova has the longest history in this area. We do not consider transactions in 2020 given the unique circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic impact in Brazil.

Several types of financial transactions and obligations are considered which include the following: contract entry fee (2% of total obligations), administrative fees (3%), and instalments (95%). We do not distinguish between these types of financial flows, but rather we compare each title holder’s complete vector of ‘obligations’ versus ‘payments’ to run our analysis on the reliability of Terra Nova’s credit model. All financial data is in real Brazilian Reals, deflated using Consumer Price Index (base year 2010) available from the World Bank.

Besides financial transactions and obligations, the dataset offers basic demographic information on title holders (year of birth, sex, profession, marital status) but no data on other members of each household. Occupant identifiers are anonymized, and geographic information is limited to city and neighborhood. The data also contains lot-level information such as lot size (meters squared), size of shared space with neighboring lots (such as common walkways), and price per square meter (assessed at a fixed value for each community on a yearly basis).

5.2. Empirical Results on Payments and Parcel Value

This section presents evidence about the capacity of residents to make payments for land regularization. Regular payments by residents are the critical element of the revenue stream of the social enterprise.

We analyzed financial transactions and obligations between Terra Nova and residents from 2000 to 2019 in the state of Paraná, which is where Terra Nova started its operations and is home to 64% of Terra Nova’s total lots. We discuss the utility of Terra Nova’s business model from two perspectives. One, from the point of view of the business, we ask, “Do title holders meet their financial obligations?” We verify that occupants overwhelmingly tend to meet their financial obligations, which suggests the business model is sustainable. In fact, we find that many occupants complete payments and do so ahead of schedule, indicating a strong willingness to become landowners under Terra Nova’s structure.

Two, from the point of view of the occupants, we ask, “Do real land prices increase over time?” We find that the real price of land (as assessed by independent appraisers hired by Terra Nova) on average increases over time. This asset appreciation can be expected to render future benefits for the occupants in terms of job security, credit worthiness, and the ability to make long-term economic investments, as well as improved mental and physical health as municipal amenities are improved for regularized settlements by municipal governments.

5.2.1. Descriptive Data

By 2019, Terra Nova had projects in three states: Paraná (64% of total lots), São Paulo (35%), and Minas Gerais (1%). In Paraná, Terra Nova accumulated 5388 unique contracts and 4990 title holders, covering 4527 lots. The median age of title holders in Paraná is 50, with a minimum age of 19 and a maximum age of 99 years. Terra Nova did not record sex for around half of the title holders, however 23% report as female and 27% report as male. Around 40% of title holders are single (never married), 40% are married or living with a spouse, 15% are divorced or separated, and 5% are widowed.

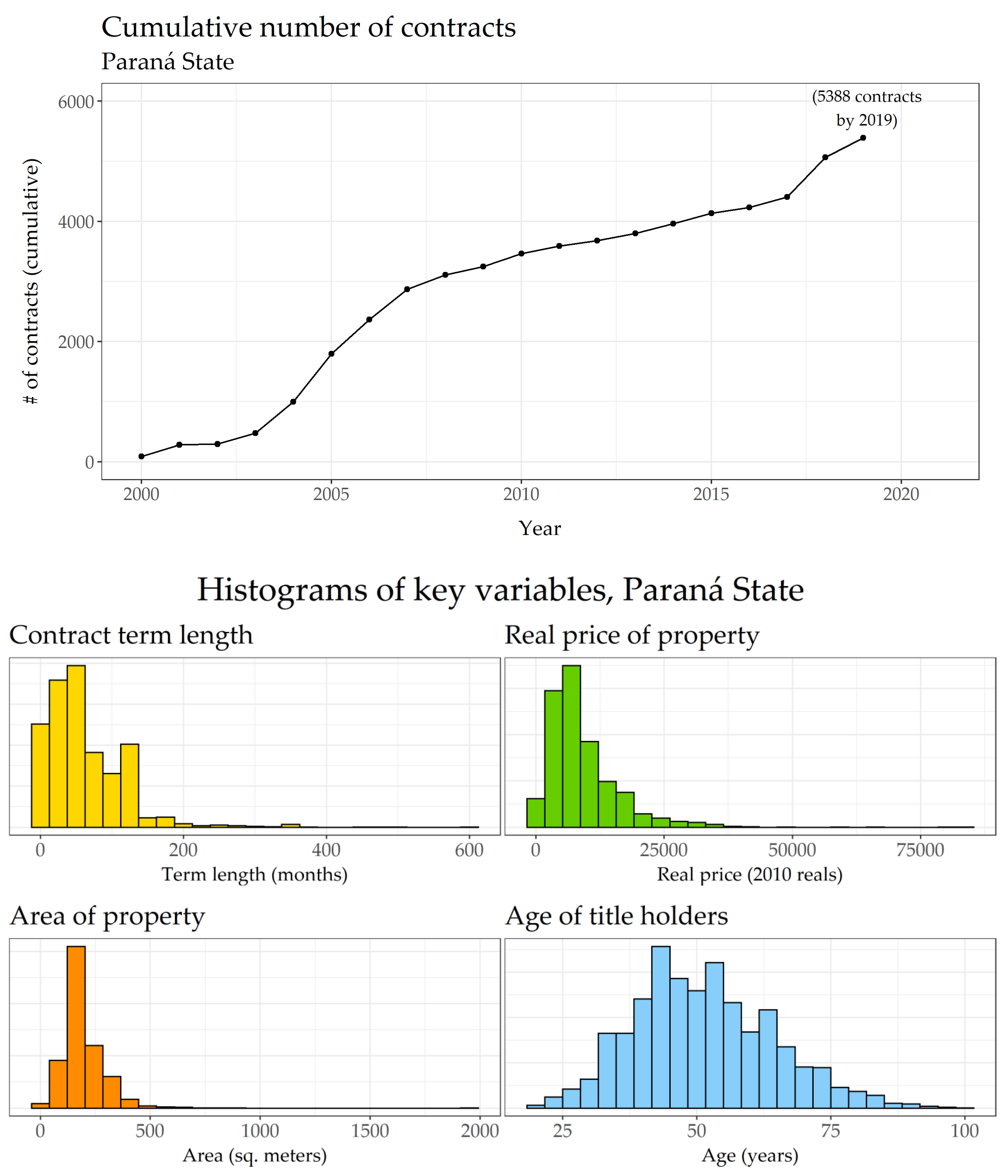

Each of the regularized parcels is issued a contract by Terra Nova which sets out the terms for repayment in installments and titling. These contracts are the basis for the data we analyze. The number and year of origination of the contracts included in the dataset are depicted in

Figure 1, as well histograms describing the distributions of contract length, real price of the parcel, the area of the property and the age of the title holders. The median term length of the contracts is 48 months, with a minimum of zero months (the case for 206 contracts in which land was bought upfront) and a maximum of 600 months (representing two outlier contracts). The median land value is R

$ 7400 (constant 2010 Reals) for the parcel and the median parcel size, which includes shared common areas such as walkways, is 175 square meters.

5.2.2. Empirical Questions

Question I: Do Title Holders Meet Their Financial Obligations?

As depicted in

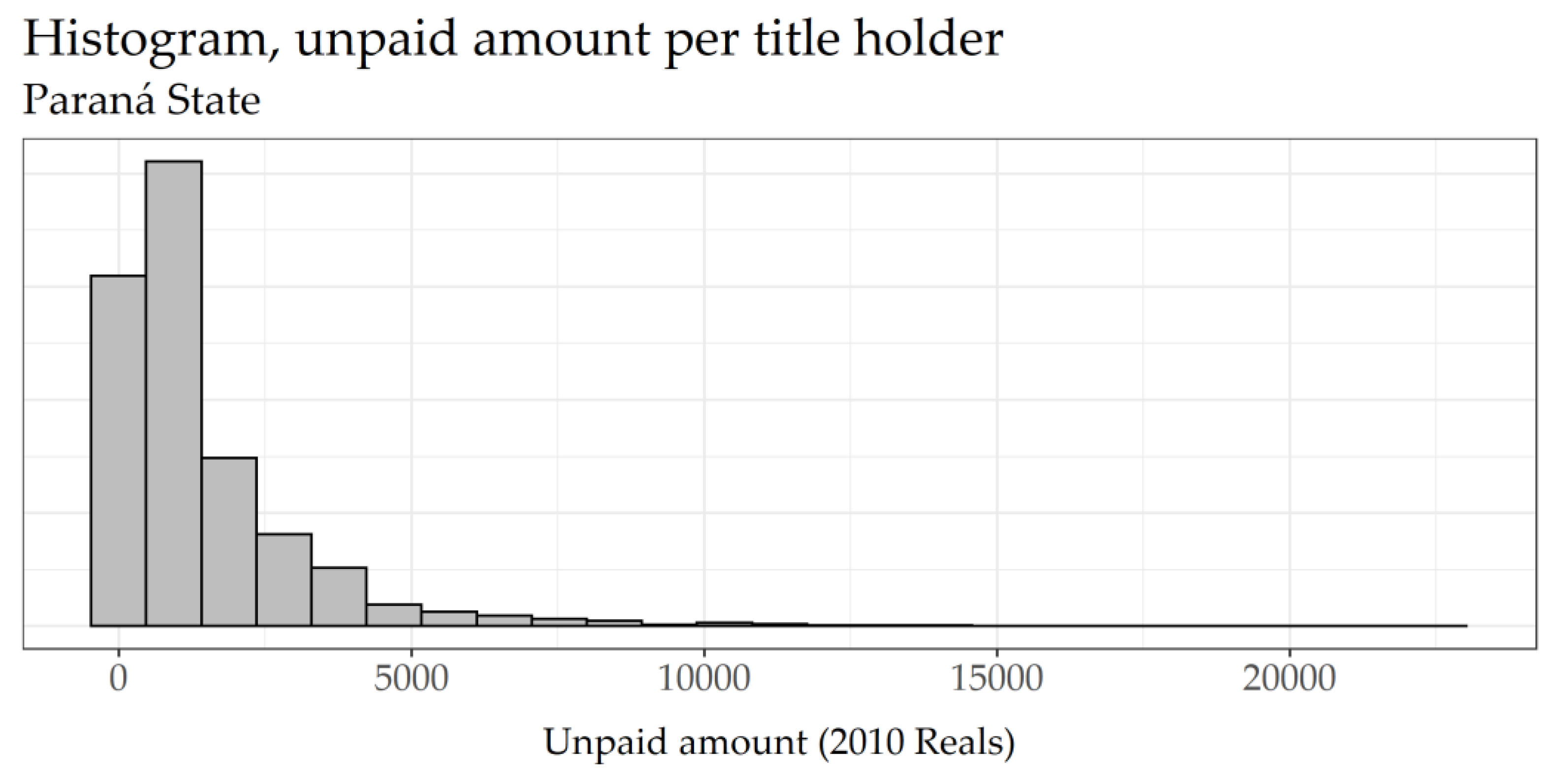

Figure 2, over the twenty-year period studied (2000–2019), obligations owed by title holders in Paraná state totaled R

$ 23.8 million (constant 2010 Reals), while the same title holders paid a total of R

$ 20.9 million (constant 2010 Reals). The unpaid amount (R

$ 3.1 million) represents 12.9% of the total financial obligations over the period. The unpaid amount, in this aggregate measure, includes all lengths of delinquency, ranging from a few days to many months of lateness. Roughly 25% of the volume of late payments is in arrears by one month or less, while less than 1% is in arrears by six months or more. Overall, Terra Nova occupants have shown a high capacity to pay on their obligations and the organization has operated successfully from a financial standpoint over the time period.

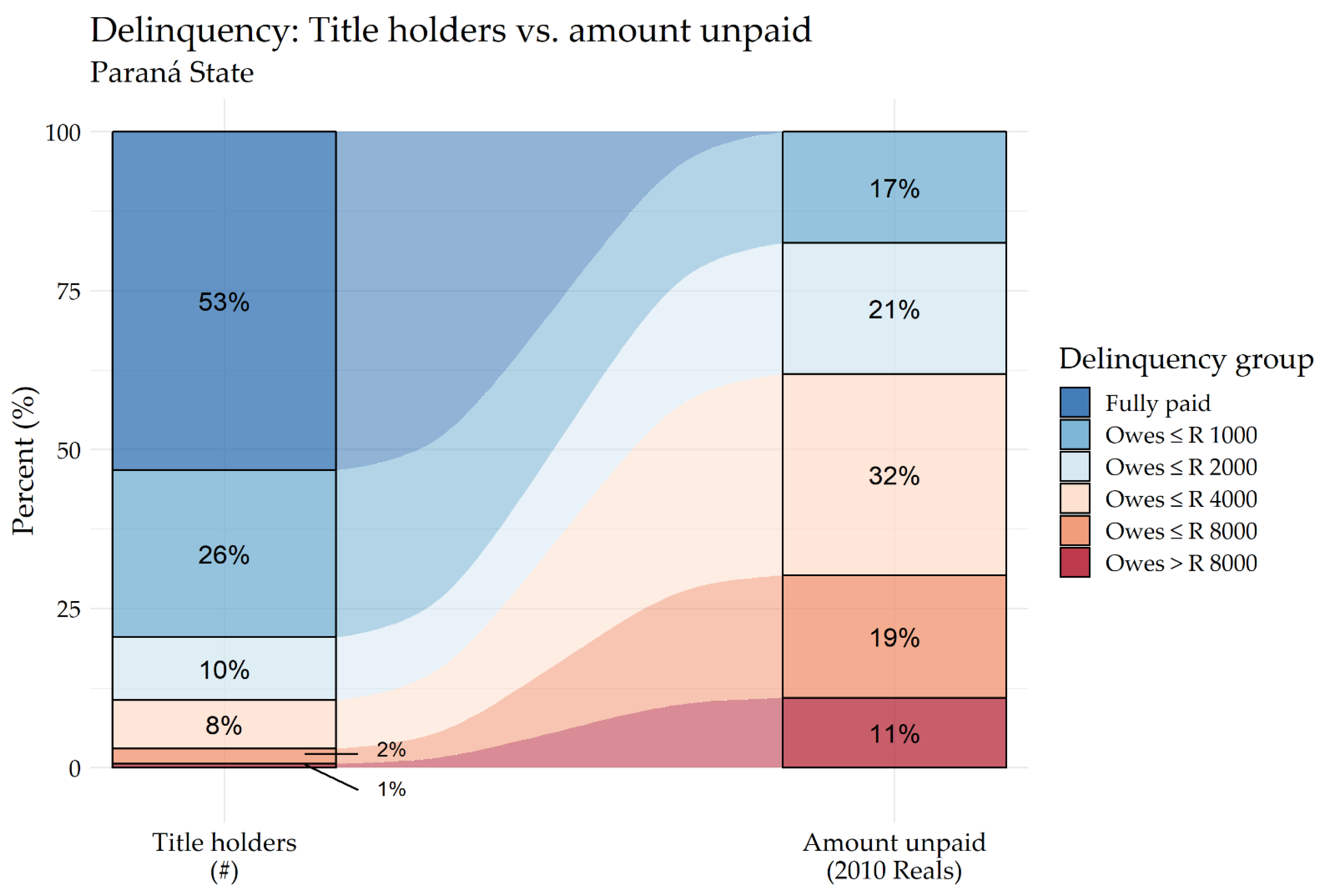

As of 2019, most delinquent title holders owe a relatively small sum (see

Figure 2). Less than 2% of title holders owe more than R

$ 8000. Of the title holders with an outstanding obligation, over 81% owe less than R

$ 2000 (constant 2010 Reals). This evidence suggests that most occupants are reluctant to fall behind on their payments and few assume tremendous debt (see

Figure 3).

Furthermore, many occupants have paid ahead of their obligations: 44% of occupants have paid more than is due as of 2019, totaling around R 300,000 (constant 2010 Reals) in early payments to Terra Nova. This reinforces the contention that occupants are eager to become landowners and are making great efforts to meet their financial obligations in this regard.

Question II: Do Real Land Prices Increase Over Time?

For occupants, there are numerous benefits of land ownership; the most basic concern is to avoid repossession by the hitherto legally recognized landowner. However, there are also plentiful economic benefits of owning land, especially land that is increasing in value.

In the process of negotiating contracts with landowners and occupants, Terra Nova hires outside appraisers who assess the value of land each year within each settlement. Land is appraised at a fixed rate (value per square meter) across an entire settlement at regular intervals. Thus, assessed land values can change over time within a settlement. We analyze real land prices over time at the project level in Paraná state.

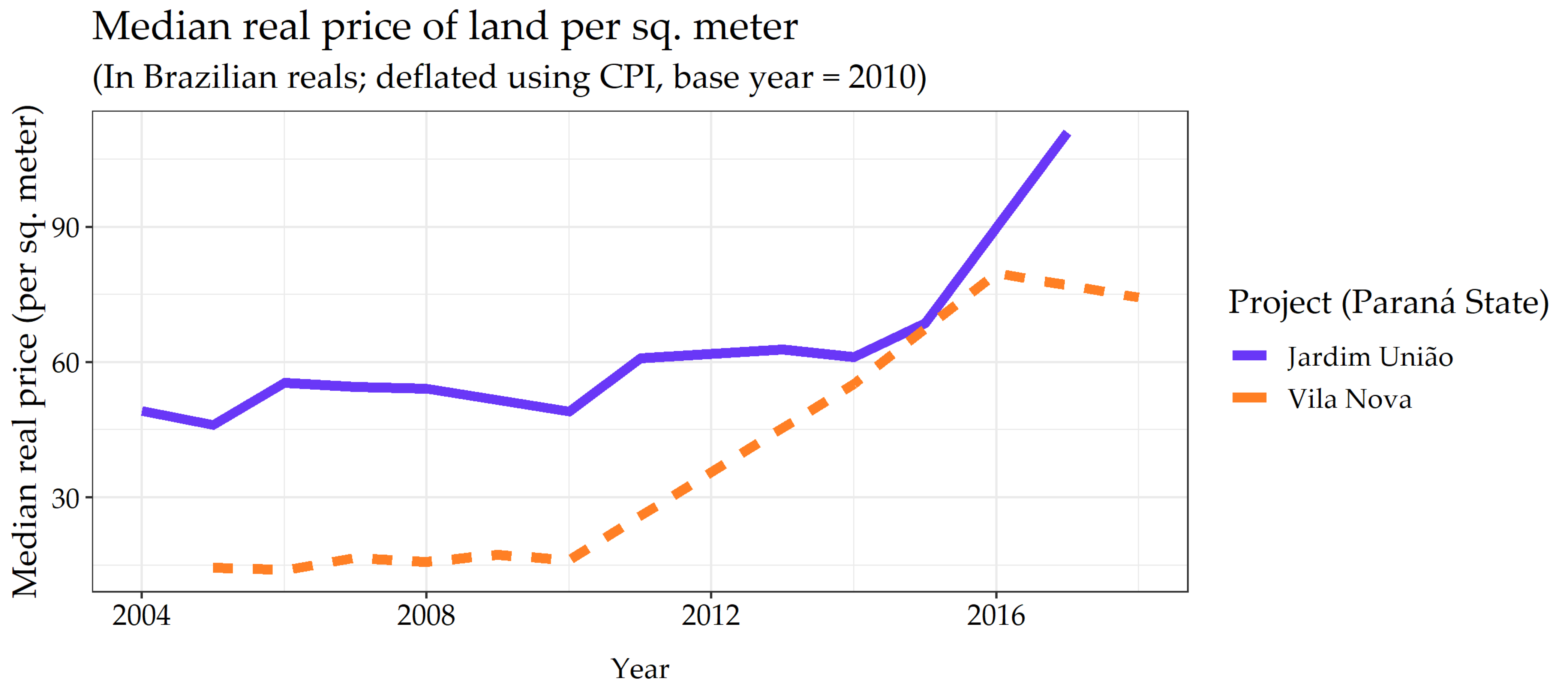

Figure 1 below presents the change in real median price for the largest ten projects in Paraná by number of lots. ‘Years active’ refers to years during which new contracts are made. For most projects that are active for more than one year, the change in the median real price per square meter is positive; moreover, the increase is greatest for projects that are active for many years (such as Jardim União and Vila Nova). In the one case (Vila União) where the median price decreases, the decrease is relatively small (R

$ -4).

The median price increase is most prominent for Jardim União and Vila Nova, the two projects with the longest history with Terra Nova (see

Figure 4 below). For Jardim União, the real mean price per square meter was just R

$ 49 in 2004 rising to R

$ 111 in 2017, a change of R

$ 62. For Vila Nova, the real mean price per square meter was just R

$ 14 in 2005 rising to R

$ 72 in 2018, a change of R

$ 60.

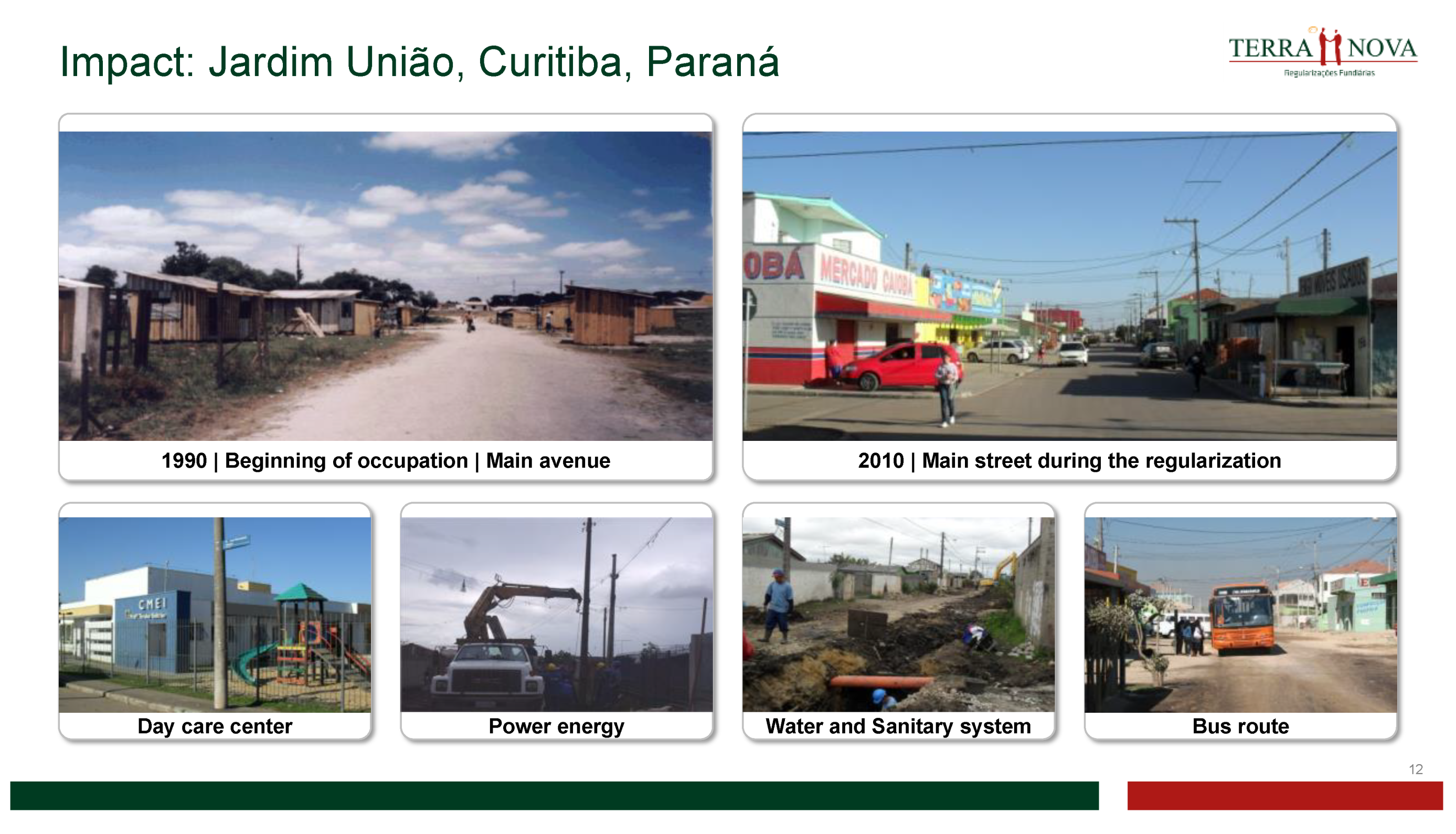

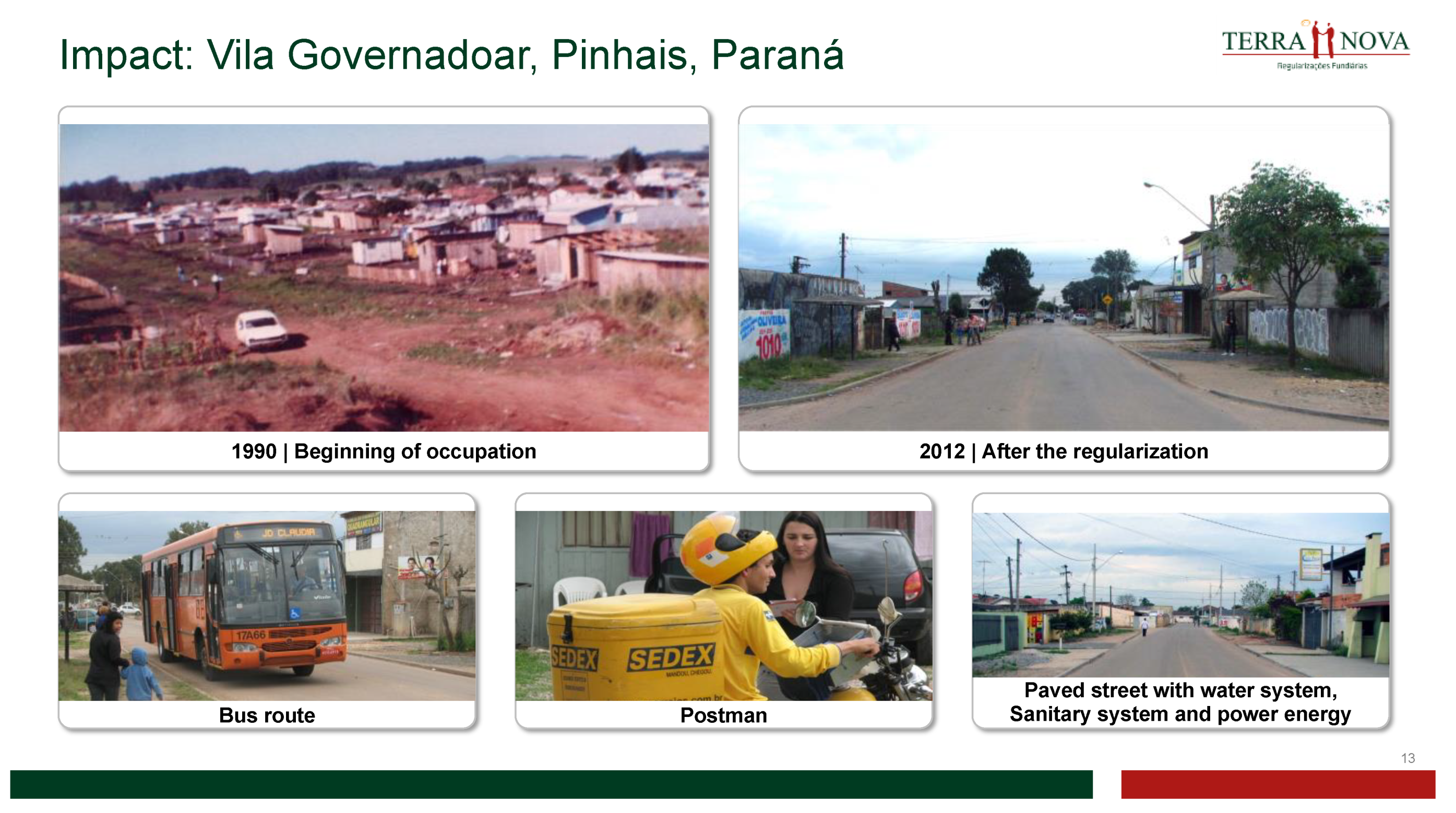

5.3. Qualitative Evidence of Impact: Pictures and Perceptions

It is also relevant to view the operation of the social enterprise from a qualitative perspective. Below in

Figure 5 we present several before-after images of settlements regularized by Terra Nova, and a summary of preliminary findings of an ongoing qualitative impact assessment in one settlement which was regularized by Terra Nova.

5.4. Residents Perceptions of Impact

Residents’ subjective perceptions of the value of the regularized land are positive. According to initial reports from qualitative studies conducted by the Getulio Vargas Foundation in 2020 in communities regularized by Terra Nova, residents perceive a variety of significant benefits from the regularization. Benefits cited by residents included relief from fear of eviction, gains in the value of fixed assets, individual feelings of achievement, access to energy, clean water and sewage services, access to postal codes, public education and health services, and changing life expectations for children. Residents also expressed that payment for the land to achieve full ownership was a major household budget priority, even during the period of economic hardship imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

6. Discussion: Bundling Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration and Land Financing Together

Terra Nova demonstrates a case of a feasible, fit-for-purpose social enterprise model for informal settlement regularization and financing which bundles land regularization and land financing together. The case fills a gap in the practice of the regularization of informal settlements which has been remarked on in the literature and thus deserves to be discussed more widely and potentially to be replicated. The relevance of the case is high in Brazil, where most informal settlements are located on land with an underlying private landowner who must be compensated in order to relinquish rights to the occupants. The case may be relevant for a wider set of applications as well in which the land value and willingness-to-pay for it by residents can be leveraged to finance infrastructure for the informal settlement in a bundled package with land regularization.

The presentation of these findings has certain limitations. The data used was not originally intended for analytical use and may have gaps and inconsistencies for that reason. Only a single case is presented and there is no evidence that the approach or model presented has been replicated directly elsewhere. The results are all based on performance prior to the COVID-19 pandemic which has been reported to have reduced the incomes of many residents of informal settlements in Brazil.

7. Conclusion: An Example of Fit-for-Purpose, Private-Sector Led Land Regularization and Financing

Terra Nova’s model demonstrates feasibility in Brazil and has the potential for wider replication. It combines fit-for-purpose, socially-embedded procedures for land regularization among informal residents, land owners, and municipal governments in an affordable package which is broadly sustainable for both residents and the social enterprise delivering the service. Terra Nova’s example of fit-for-purpose land regularization and fit-for-purpose land financing addresses the coordination failure among residents, the market failure in the residential land market for low-income groups, and the governance failure in public regularization and social housing.

Further developments to scale up which Terra Nova is now developing include the packaging of infrastructure provision into the financing package (i.e., land and infrastructure together), creation of compensation funds which can be flexibly utilized to compensate multiple landowners and securitizing streams of payments to leverage of investment capital to increase the number of settlements which can be regularized at any given time by expanding operating capital and workflow. In the current circumstances of limited public sector activity for informal settlement regularization and upgrading in Brazil, private-sector led regularization and financing is likely the only model which is feasible at the scale of the problem. Continued success of Terra Nova’s example in Brazil could pave the way for replication in other countries in Latin America and potentially in other regions where informal settlement has long been identified as a widespread and critical issue for social wellbeing and asset-building for low-income groups.

Author Contributions

M.C. contributed the conceptualization of the paper, the main drafting of the literature review, discussion and conclusions. S.C. contributed the preparation of the data set and the main drafting of the empirical results section and interpretation of results. E.B. contributed to the overall conceptualization of the paper, drafting of the sections on informal settlements in Brazil and the qualitative impact results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Support for this research was provided in part by a grant from the Omidyar Network (No. 00033443-3). Funding for the publication costs of this article has kindly been provided by the School of Land Administration, University of Twente in combination with Kadaster International, the Netherlands.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is exempt from IRB approval because it utilizes de-identified data provided by the social enterprise for purposes of improving the efficacy of its programs through additional analysis.

Informed Consent Statement

The study utilizes de-identified data provided by the social enterprise.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request from qualified researchers through the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UN Habitat. Pro-Poor Action for Climate Change in Informal Settlements. 2018. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/pro-poor-climate-action-in-informal-settlement (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Portes, A.; Castells, M.; Benton, L. (Eds.) The World Underneath: The Origins, Dynamics and Effects of the In-formal Economy. In The Informal Economy: Studies in Advanced and Less Developed Countries; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tellmann, B.; Eakin, H.; Janssen, M.; de Alba, F.; Turner, B. The role of institutional entrepreneurs and in-formal land transactions Mexico City’s urban expansion. World Dev. 2021, 140, 105374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High Level Forum on Sustainable Development. 2018. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/197282018_background_notes_SDG_11_v3.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- UN Habitat. A Practical Guide to Designing, Planning and Implementing City-wide Slum Upgrading Programs. 2014. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Housing/InformalSettlements/UNHABITAT_A_PracticalGuidetoDesigningPlaningandExecutingCitywideSlum.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Fernandes, E.; Regularization of Informal Settlements in Latin America. Policy Focus Report. The Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. 2011. Available online: https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/regularization-informal-settlements-latin-america-full_0.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Huchzermeyer, M.; Karam, A. Informal Settlements: A Perpetual Problem? 1st ed.; University of Cape Town Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 1 April 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Huchzermeyer, M. The struggle for in situ upgrading of informal settlements: A reflection on cases in Gauteng. Dev. South. Afr. 2009, 26, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huchzermeyer, M. Pounding at the Tip of the Iceberg: The Dominant Politics of Informal Settlement Eradication in South Africa. Politikon 2010, 37, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Stats SDG 11. 2016. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2016/goal-11/ (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Durand-Lesserve, A. Informal settlement and the Millenium Development Goals: Global Policy Debates on Property ownership and security of tenure. Glob. Urban Dev. 2006, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- UN. The Sustainable Development Goals Report. 2020a. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2020.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Habitat III. The New Urban Agenda. 2016. Available online: https://habitat3.org/the-new-urban-agenda/ (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Millington, K.A.; Cleland, J. Counting People and Making People Count: Implications of Future Population Change for Sustainable Development; K4D Helpdesk Report; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.ids.ac.uk/publications/counting-people-and-making-people-count-implications-of-future-population-change-for-sustainable-development/ (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Wekesa, B.; Steyn, G.; Otieno, F. A review of physical and socio-economic characteristics and intervention approaches of informal settlements. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.P.; Jiménez, E.; di Virgilio, M.; Camargo, A. (Eds.) Políticas de vivienda en ciudades Latinoamericanas: Una nueva generación de estrategias. In Housing Policy in Latin American Cities: A New generation of Strategies and Approaches for 2016 UN-Habitat III; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cities Alliance. Informal Settlement. 2021. Available online: https://www.citiesalliance.org/themes/informal-settlements (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- World Bank. Systems of Cities: Harnessing Urbanization for Growth and Poverty Alleviation. 2020. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/publication/urban-local-government-strategy (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Nzau, B.; Trillo, C. Affordable Housing Provision in Informal Settlements through Land Value Capture and Inclusionary Housing. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acolin, A.; Hoek-Smit, M.C.; Eloy, C.M. High delinquency rates in Brazil’s Minha Casa Minha Vida housing program: Possible causes and necessary reforms. Habitat Int. 2019, 83, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Cities of Opportunity: Partnerships for an Inclusive and Sustainable Future. In Proceedings of the Fifth Asia-Pacific Urban Forum, Bangkok, Thailand, 20–25 June 2011. Available online: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/report.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Binswanger, H.P.; Elgin, M. Reflections on land reform and farm size. In Agricultural Development in the Third World; Eicher, C.K., Staatz, J.M., Eds.; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Enemark, S.; McLaren, R.; Lemmen, C. Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration—Guiding Principles for Country Implementation; GLTN/UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Harvard Business School. Terra Nova: A Social Business Trying to Unlock Land Rights for the Urban Poor in Brazil—Case Study; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).