Co-Management of Protected Areas: A Governance System Analysis of Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How can a co-management governance system be designed for a large national park?

- What have been the main challenges impacting the performance of the co-management governance system?

- What are the key policy implications and how can they inform park governance and rural development?

2. Materials and Methods

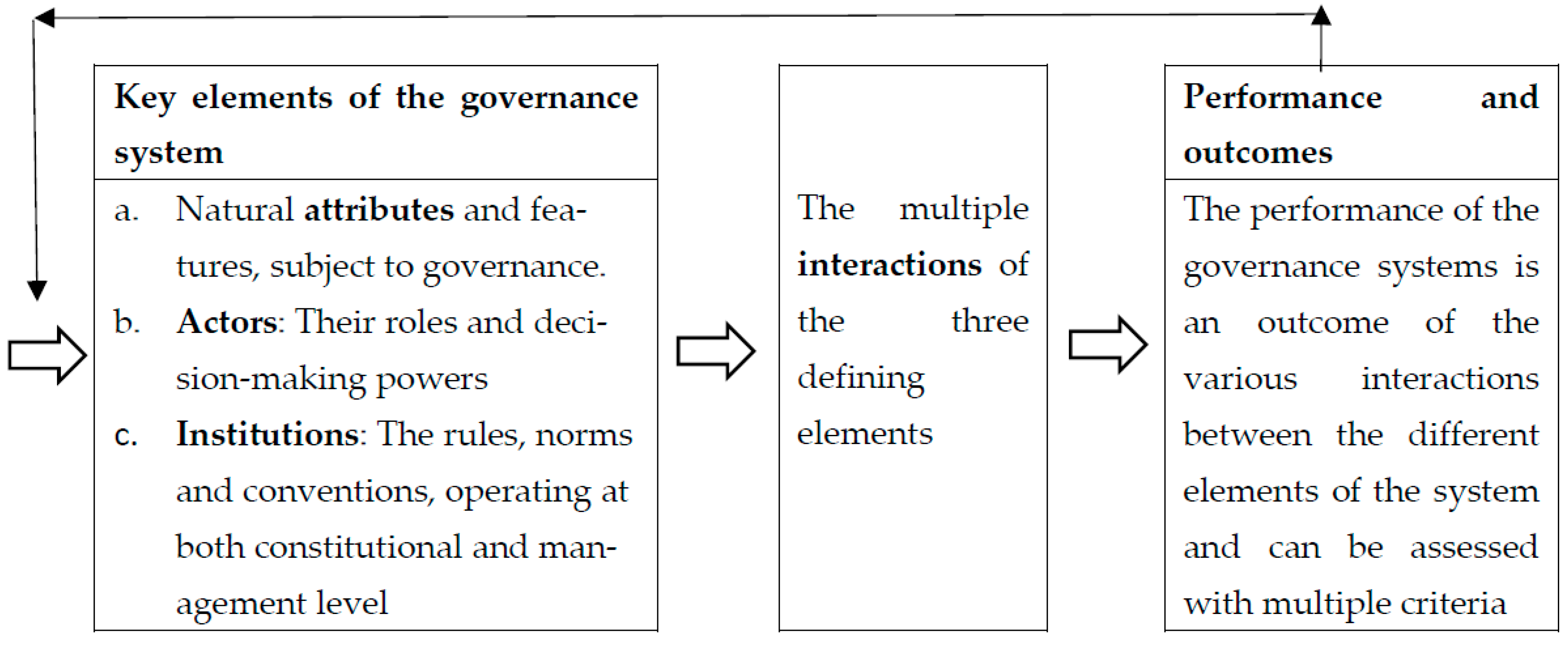

2.1. Governance System Analytical Framework

2.2. Assessing Performance of a Governance System

2.3. The Study Site and Its Governance Context

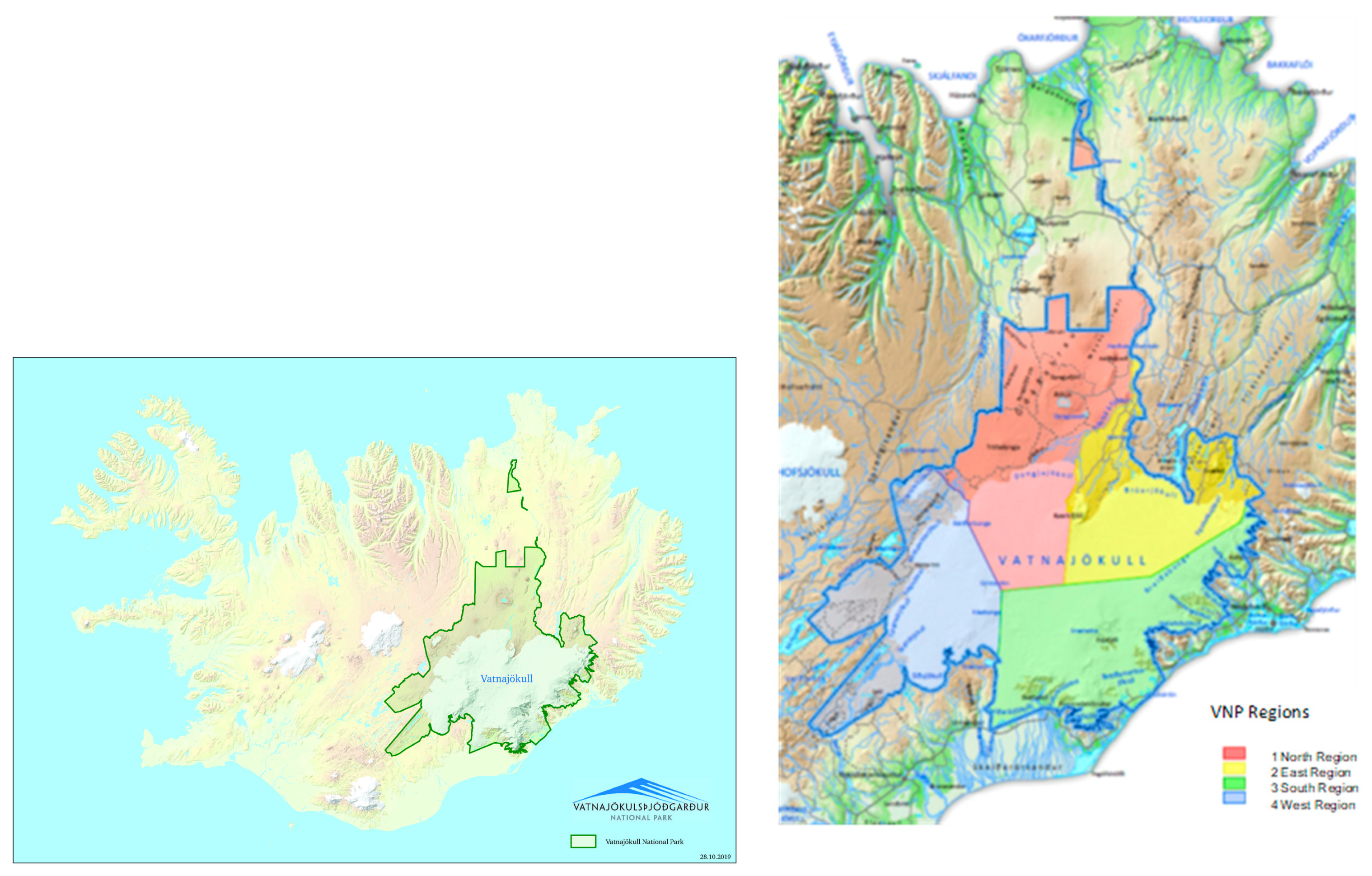

2.3.1. The Case: Vatnajökull National Park

2.3.2. Some Governance Factors Related to Area-Based Conservation in Iceland

2.4. Data Sources

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Historical and Political Legacies Shaping VNP Approach to Governance

3.2. Institutions for Park Co-Management, Their Fit and Interplay

- (a)

- Conservation of nature and culture;

- (b)

- Public access;

- (c)

- Research and education;

- (d)

- Regional economic development and sustainable use.

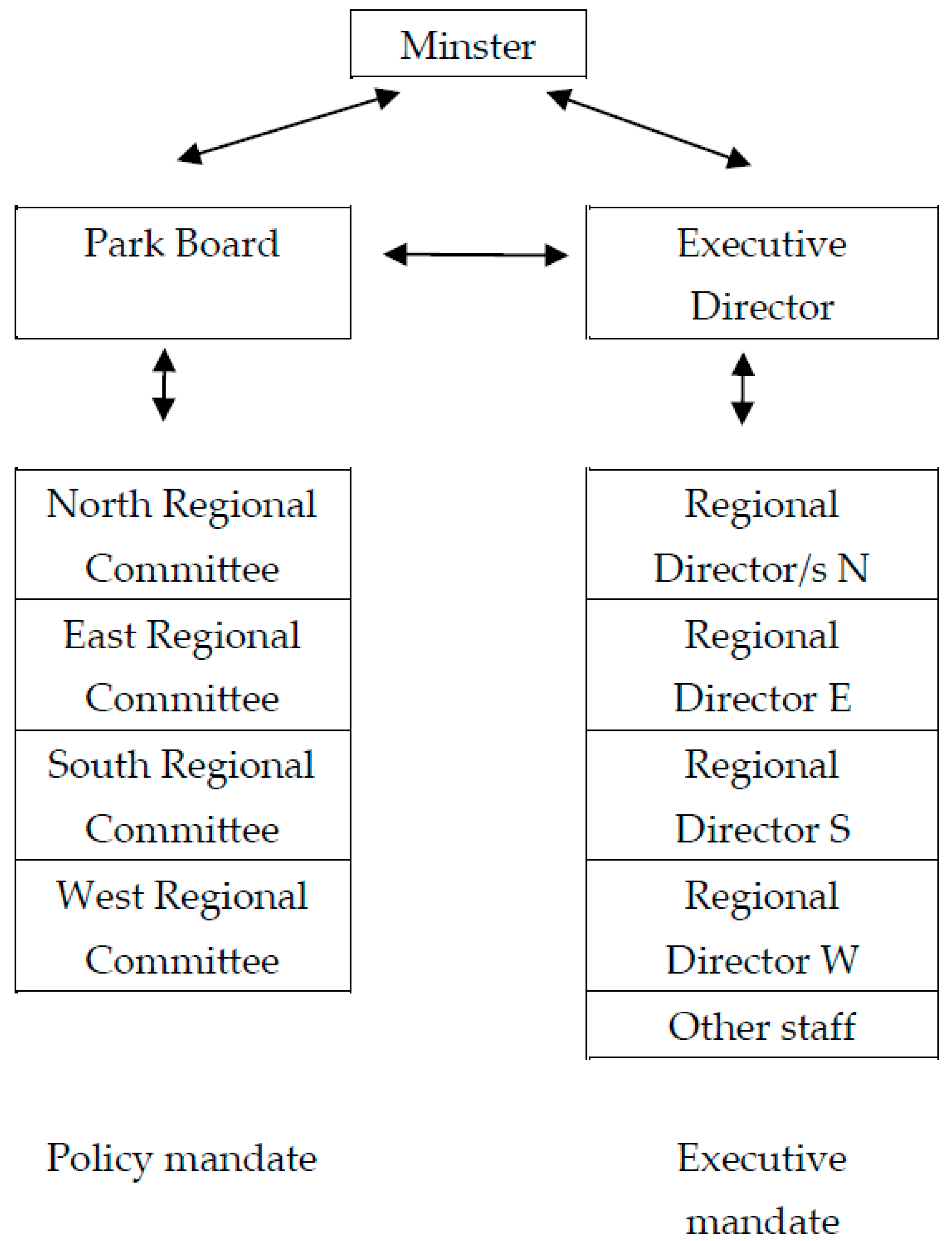

3.3. The Actor Structure, Their Roles and Powers

3.3.1. The Actor Structure, Power and Membership

3.3.2. Actor Complexity and Role Ambiguity

4. Conclusions and Implications for Policy

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leclère, D.; Obersteiner, M.; Barrett, M.; Butchart, S.H.; Chaudhary, A.; De Palma, A.; DeClerck, F.A.; Di Marco, M.; Doelman, J.C.; Dürauer, M.; et al. Bending the curve of terrestrial biodiversity needs an integrated strategy. Nature 2020, 585, 551–556. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, M.; Saura, S.; Williams, B.; Ramírez-Delgado, J.P.; Arafeh-Dalmau, N.; Allan, J.R.; Venter, O.; Dubois, G.; Watson, J.E. Just ten percent of the global terrestrial protected area network is structurally connected via intact land. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, J.E.M.; Dudley, N.; Segan, D.B.; Hockings, M. The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature 2014, 515, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Dudley, N.; Jaeger, T.; Lassen, B.; Pathak Broome, N.; Phillips, A.; Sandwith, T. Governance of Protected Areas: From Understanding to Action; IUCN: Gland, Switserland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eklund, J.; Cabeza, M. Quality of governance and effectiveness of protected areas: Crucial concepts for conservation planning. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1399, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, L.; Berkes, F. Co-management: Concepts and methodological implications. J. Environ. Manag. 2005, 75, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Wakjira, D.T.; Weldesemaet, Y.T.; Ashenafi, Z.T. On the interplay of actors in the co-management of natural resources—A dynamic perspective. World Dev. 2014, 64, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Farvar, M.T.; Nguinguiri, J.C.; Ndangang, V.A. Co-Management of Natural Resources: Organising, Negotiating and Learning-by-Doing; GTZ and IUCN: Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fedreheim, G.E.; Blanco, E. Co-management of protected areas to alleviate conservation conflicts: Experiences in norway. Int. J. Commons 2017, 11, 754–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovik, S.; Hongslo, E. Balancing local interests and national conservation obligations in nature protection. The case of local management boards in norway. J. Environ. Plann. Manag. 2017, 60, 708–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plummer, R. The adaptive co-management process: An initial synthesis of representative models and influential variables. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.; Cherrett, N.; Pemsl, D. Assessing the impact of fisheries co-management interventions in developing countries: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 1938–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, M. Good governance for terrestrial protected areas: A framework, principles and performance outcomes. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petursson, J.G.; Vedeld, P. Rhetoric and reality in protected area governance: Institutional change under different conservation discourses in mount elgon national park, uganda. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 131, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrini, G.; Kothari, A.; Oviedo, G. Indigenous and Local Communities and Protected Areas. Towards Equity and Enhanced Conservation; IUCN: Gland, Switerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cundill, G.; Thondhlana, G.; Sisitka, L.; Shackleton, S.; Blore, M. Land claims and the pursuit of co-management on four protected areas in south africa. Land Use Policy 2013, 35, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J.C.; Agrawal, A.; Larson, A.M. Recentralizing while decentralizing: How national governments reappropriate forest resources. World Dev. 2006, 34, 1864–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, J.; Adams, W.M.; Murombedzi, J.C. Back to the barriers? Changing narratives in biodiversity conservation. Forum Dev. Stud. 2005, 32, 341–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, B.A. Parks in transition: Adapting to a changing world. Oryx 2014, 48, 469–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spenceley, A. Tourism and protected areas: Comparing the 2003 and 2014 iucn world parks congress. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 17, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandwith, T.; Enkerlin, E.; MacKinnon, K.; Allen, D.; Andrade, A.; Badman, T.; Brooks, T.; Bueno, P.; Campbell, K.; Ervin, J.; et al. The promise of sydney: An editorial essay. Parks 2013, 20, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, S. Legitimacy and disappointment in fisheries management. Mar. Policy 2000, 24, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Evolution of co-management: Role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1692–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenseke, M. Local participation in cultural landscape maintenance: Lessons from sweden. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petursson, J.G.; Thorvardardottir, G.; Crofts, R. Developing iceland’s protected areas: Taking stock and looking ahead. Parks 2016, 22, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1990; p. xviii. 280p. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vatn, A. Institutions and the Environment; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatn, A. Environmental Governance; Institutions, Policies and Actions; Edward Elgar: Celtenham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Young, O.R. The Institutional Dimensions of Environmental Change: Fit, Interplay, and Scale; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy, R.S.; Berkes, F. Two to tango: The role of government in fisheries co-management. Mar. Policy 1997, 21, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, B. Non-State Actors in Global Governance: Three Faces of Power; Max-Planck-Projektgruppe Recht der Gemeinschaftsgüter: Bonn, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984; p. xxxvii. 402p. [Google Scholar]

- Backstrand, K. Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainable development: Rethinking legitimacy, accountability and effectiveness. Eur. Environ. 2006, 16, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. Integrating conservation and development: A case of institutional misfit. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2003, 1, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatn, A.; Vedeld, P. Fit, interplay, and scale: A diagnosis. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baldursson, S.; Gudnason, J.; Hannesdottir, H.; Thordarson, T. Nomination of Vatnajökull National Park for Inclusion in the World Heritage List; Vatnajökull National Park: Reykjavik, Iceland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Umhverfisstofnun. The 2021 Annual Report of The Icelandic Environment Agency; Iceland Environment Agency: Reykjavik, Iceland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. “Iceland”; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Siltanen, J. Economic Impact of Iceland’s Protected Areas and Nature-Based Tourism Sites; Institute of Economic Studies: Reykjavik, Iceland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Solnes, V. Administrative committee clarifying land ownership. The icelandic wasteland commission. Nord. Adm. J. 2017, 94, 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson, V. Orðræða um Stofnun Vatnajökulsþjóðgarðs. Ferðamennska, Sjálfbærni og Samfélag. Master’s Thesis, Univerisity of Iceland, Reykjavík, Iceland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Feingold, M. The Political Ecology of Protected Areas: The Case of Vatnajökull National Park. Master’s Thesis, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Petursson, J.G.; Ingolfsdottir, G.; Kristofersson, D.M. Endurskoðun á Stjórnfyrirkomulagi Vatnajökulsþjóðgarðs; Reykjavik, Iceland. 2013. Available online: https://rafhladan.is/bitstream/handle/10802/24252/vatnajokull_lokaskyrsla-180713.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Benediktsson, K.; Thorvardardottir, G. Frozen opportunities? Local communities and the establishment of vatnajökull national park iceland. In Mountains of Northern Europe: Conservation, Management, People and Nature; Thompson, D.B.A., Price, M.F., Galbraith, C.A., Eds.; Scottish Heritage: Edinburgh, UK, 2005; pp. 333–347. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson, S.B. Vatnajökulsþjóðgarður (vatnajökull national park). Glettingur 2007, 44, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Saeporsdottir, A.D.; Hall, C.M.; Wendt, M. Overtourism in iceland: Fantasy or reality? Sustainability 2020, 12, 7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingólfsdóttir, A.I.; Árnason, T.; Siltanen, J.; Jóhannesson, H. Náttúruvernd og Byggðaþróun: Hrif Verndarsvæða á Grannbyggðir; Hagfræðistofnun Háskóla Íslands: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- National Audit Office. Vatnajökulsþjóðgarður. Ríkisendurskoðun, Skýrsla til Alþingis (Vatnajökull National Park. National Audit Office, Report to the Parliament); National Audit Office: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Analytical Criteria | Relative to Park Governance | |

|---|---|---|

| Legitimacy | Input level | Factors that shaped the park creation. Focus on participation and representation. |

| Output level | Factors related to park operation. Focus on accountability and performance. | |

| Institutional fitness | Fit | The fitness of the governance system to the physical attributes. Concerns mainly spatial fit, but is to a lesser degree temporal and functional. |

| Interplay | The interplay with other institutions at both horizonal and vertical levels. | |

| Lead Document | Responsible Actors | Adoption and Amendment Power | Key Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legislation | The Icelandic Parliament | By majority at the parliament | Outlines the overall objectives and the governance structure including role and mandates of key actors |

| By-law | The Minister | The minister can make changes, however, usually following consultation with the Park Board | Defines the park spatial boundaries. Sets out key rules |

| Management Plan (stjórnunar og verndaáætlun) | The Park Board | The management plan is produced by regional councils and the Park Board. The Minister signs and ratifies the Plan but his options to make changes are limited to issues that might conflict the park legislation | Give detailed account of how the park is supposed to be governed, sets out decisions on infrastructure and access rules |

| Commercial activity policy (atvinnustefna) | The Park Board | Produced by the regional councils and Park Board. Issued by the Park Board | Outlines VNP’s policy on commercial operations within the park and instruments for their governance |

| Other rules, norms and conventions | The regional councils, Park Board and Director | Diverse Codes of conduct and Rules of procedures that apply to different administrative units within the co-management system. Amendment power by the respective units. | |

| Resources Use | Main Rules of Access | Manifestation |

|---|---|---|

| General access and recreation | Allowed | According to the Icelandic free right to roam (almannaréttur), all individuals are entitled to enter the park and wander. |

| Sheep grazing | Summer grazing is allowed for a given set of pastures under traditional uses | Farmers have legally protected long-term usufruct rights to grazing to most lands within the park boundary. |

| Hunting: reindeer | Allowed in defined areas according to the national reindeer hunting regime | Hunting licences are allotted by government annually. Some no-hunting zones within the park. |

| Hunting: birds | Generally allowed Prohibited in defined areas with the park | Subject to hunting licences issued by the government. Some no-hunting zones within the park. |

| Non-commercial fishing | Traditional rules prevail | Farmers groups keep the fishing rights they had before the park. Fishing licences. |

| Commercial Tourism * | Subject to permit from the park | The changes in the park legislation in 2016 made clauses of licencing for commercial tourism activities within the park. |

| Level | Actors | Description | Some Important Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central | Ministry for the Environment and Natural Resources | VNP is an independent government authority, directly reporting to the Ministry | Appoints the Board Formalises Director’s appointment according to the Board’s recommendation Financial supervision relative to the state budget Overall responsibility |

| Park Board | Seven board members. Two appointed by the minister, one from each of the four regional units, one from environment civil society. Also, two civil society actors have observer status. | Policy and decision-making Coordination of regional inputs and creation of the management plan Approve the budget and allocate to regions Harmonise the operation of the four regions | |

| Executive Director | The executive director of the park | Execute decisions and policy, set out in the management plan Daily management Staff Finance | |

| Regional | Regional committees | The park is divided into four administrative regions: north, east, south and west. | Responsible for park management policy-making within each region Prepares regional sections of the overall park management plan |

| Regional park managers | For each of the four management regions. Appointed after recommendation from the regional boards | Responsible for the management activities of individual regions | |

| Local | Local governments | There are eight local governments that border the park | Have three members on the regional boards and four in the Park board |

| Recreational NGOs | A group of NGOs engaged in recreation. | Members of the regional committee and observer at the Park Board | |

| Environmental NGOs | A group of NGOs engaged in conservation. | Members of the regional board and Park Board | |

| Tourism actors | The regional tourism societies | Members of the regional committee and observer at the Park Board |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petursson, J.G.; Kristofersson, D.M. Co-Management of Protected Areas: A Governance System Analysis of Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland. Land 2021, 10, 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10070681

Petursson JG, Kristofersson DM. Co-Management of Protected Areas: A Governance System Analysis of Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland. Land. 2021; 10(7):681. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10070681

Chicago/Turabian StylePetursson, Jon Geir, and Dadi Mar Kristofersson. 2021. "Co-Management of Protected Areas: A Governance System Analysis of Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland" Land 10, no. 7: 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10070681