1. Introduction

China’s reservoir-building spree has been fuelled by the reform and opening-up that has occurred since 1978. By 2018, there were more than 98,795 reservoirs, including 732 large reservoirs with a capacity of more than 100 million m

3 [

1]. Because of the considerable increased capacity in terms of water storage, many people have been subjected to enormous risks due to physical displacement, relocation, and resettlement [

2]. In the late 20

th century, due to the pervasive lack of prior surveys, sufficient planning and use of meticulous designs [

3], millions of reservoir resettlees were not sufficiently compensated, nor were their livelihoods and property properly reinstated. This has shaped the initial image of resettlement in China. The extensive resettlement activity in China has been gradually rectified since the 21

st century due to remarkable growth in international investment and guidelines injected into China’s dam industries. The pursuit of “best practice” for resettlement, relieving the “trauma” [

4], and ensuring that resettlement is “naturalised, legitimate and durable” [

5] have become prevalent. Therefore, the traditional budget structure, time metrics, and technical specifications of resettlement are being updated and improved [

6], and academia is concerned with more aspects, such as livelihood building, land reallocation, psychological recovery, voluntarism, and self-fulfilment [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

In China, a reservoir project and its induced resettlement action would generate multiple impacted identities, including distant-resettlees, nearby-resettlees, non-movers, and host households in both reservoir and resettlement areas. This paper focuses on the former three groups. There was little distinction among them before resettlement occurred. The overwhelming majority are rural people [

12] as most of China’s reservoir projects are located in rural areas. In the (post-) resettlement stage, they are classified into three sectors according to their movement characteristics.

Distant-resettlees are generally people who are required to relocate far from their original counties to resettlement villages in other counties outside of the reservoir area, i.e., submergence-affected counties. Their movements and final destinations are mostly managed by authorities to ensure sufficient exploitable land resources and better living conditions [

13,

14,

15]. In addition to obtaining reallocated land, distant-resettlees would receive land acquisition compensation and resettlement subsidies based on times of their average annual output value (AAOV). Moreover, to help distant-resettlees overcome the incompatibility caused by long-distance resettlement, usually some targeted measures and mutually beneficial mechanisms are employed to address the lifestyles, religious beliefs, customs, and habits of the distant-resettlees and receiving communities [

15]. Distant-resettlement is costly, but is growing in popularity in China. This is because it can largely alleviate land shortage caused by dam impoundment and is conducive to the restructuring of supporting water conservancy facilities and the protection of the ecological environment.

Nearby-resettlees are individuals whose housing or land (or both) are resettled to another place within the counties of the reservoir area [

14,

15,

16]. This group has mostly moved a short distance within their original county, thus they are also called near-relocated people or intra-county resettlees [

17]. All nearby-resettlees are similarly paid once-off land requisition fees and resettlement subsidies similar to distant-resettlees. Nearby-resettlement is widely practised in China as it is generally cost effective, easily implemented, and has less influence on the resettlees’ social networks. Compared to distant-resettlement, most people are inclined to relocate nearby if their original fixed assets are submerged and movement is inevitable. However, the principle of proximity has been no longer encouraged in resettlement activities since the regulations on land requisition compensation and resettlement for large and medium water conservation and hydropower construction projects (2006 Amendment). Because the nearby-resettlement approach intensifies the incisive contradiction between human and land, which essentially causes the remaining unsubmerged land to be overloaded with a larger population. Given the land-based nature of China’s dam-induced resettlement [

12,

18], the shortage of land in reservoir areas results in risks of livelihood deterioration and stalled development [

19] for nearby-resettlees.

Non-movers constitute an under-defined group. In China, this group is not included in a resettlement plan, so they almost have no choice, but to stay put in the reservoir area after resettlement occurs. This is because authorities believe that this population, who live in high-elevation reservoir areas, are not directly impacted by submergence. It is worthy to note that, in the reservoir context, non-movers differ from the general non-moved people [

20,

21,

22], because the bottom half of the villages from a vertical perspective in which the former live is partially flooded in the post-resettlement stage [

23,

24]. Given this, non-movers are affected by many other aspects rather than reservoir flooding per se. It has been verified that there is a severe lack of infrastructure, public services, and development opportunities in the waterside or mountainside where non-movers live [

25]. Although the situation of this population has been partly recognised by developers and governments, the “economic displacement” experiences [

26] of non-movers are scarcely compensated. To exonerate themselves from compensation claims, non-movers are specifically named Liuzhi (literally means left and stagnant) population in some of China’s praxis [

24,

25,

27]. This identification largely confuses the concepts between those who are not moved and those who are not influenced. Thus, non-movers are kept away from the umbrella of post-resettlement support policies, which are applicable to officially identified “resettlees” [

28].

A research gap exists in reservoir-induced resettlement studies in China’s context. There is insufficient research concerning the nearby-resettlees and the literature on the non-movers in the reservoir area is still in its infancy. Thus, in general, what is known about this population left behind in the reservoir area remains unclear and their nexus with distant-resettlees has not yet been assessed in a systematic manner. There is a need to revisit the conceptual roots of resettlement, give proportionate attention to the broader reservoir-affected people, and analyse how distant-resettlees intersect with the population left behind who are important subjects for expanding research and developing legitimate resettlement practices. To address this gap, the following research questions are highlighted: are those who stay in a reservoir area less impacted than the distant-resettlees who move outside of this reservoir area? Why or why not, and what is the underlying mechanism?

This study is based on a comparative approach, which incorporates nearby-resettlees and non-movers as “stayers”, and is contrasted with the distant-resettlees. The settlements where these groups live in are respectively named “stayer communities/villages” and “distant-resettlee communities/villages”. This area-based categorisation effort roots in the fact that all distant-resettlees live in the communities outside of the reservoir area while the settlements of nearby-resettlees and non-movers are intricately distributed in the reservoir area. This grouping initially arises by referring to the Special Issue of

Population, Space and Place regarding “the nexus between migrants and the left-behind people” [

29] to bring the left-behind back into view. We use the terminology of stayers instead of the left-behind people, because the latter has its special academic connotations [

30]. Compared with stayers’ intergroup differences, their collective disparities with distant-resettlees are tentatively highlighted in our works to attract early concerns in this field.

The potential contributions of framing a comparison between distant-resettlees and stayers include the followings. On the one hand, this nexus provides a balanced analytical perspective of resettlement outcomes, divides the centric status of distant-resettlees in China, attaches importance to individuals who are nearly or are not relocated and recognises the stayers as independent and multi-dimensional subjects rather than simply by-products of resettlement. On the other hand, a comparison of distant-resettlees and stayers enables the development of a systematic and insightful perspective, which helps with the understanding of hidden governance logic and mechanism of China’s resettlement practice.

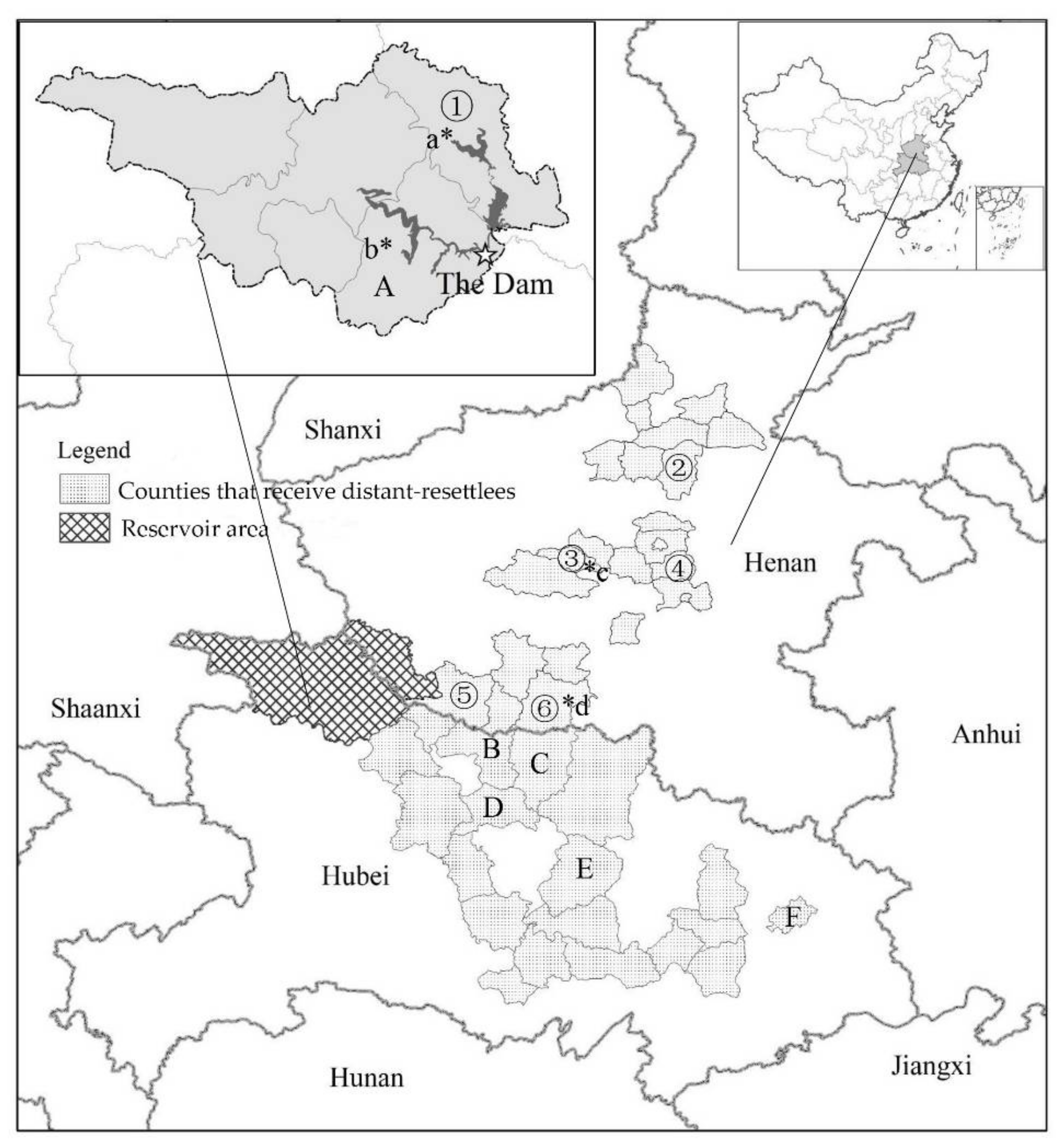

China’s Danjiangkou Reservoir is an ideal case study area, which allows us to develop a comprehensive demographic profile of distant-resettlees and stayers. The reservoir is located near the junction of the Han River and Dan River in the hinterland of China and was initially built in 1958 to control flooding, provide irrigation, and generate hydroelectricity. Since the 1990s, Danjiangkou Reservoir was meant to be more than a regular hydropower reservoir because it would function as the catchment area for the middle route of the South-to-North Water Diversion (SNWD) project, which sends water from a perceived “water surplus” area (Henan and Hubei Provinces) to a “water deficit” area, the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei plain in north China. To enrich the runoff of the SNWD, the original water-retaining dam of Danjiangkou Reservoir was heightened by 14.6 m, so that the reservoir’s water storage capacity could be increased [

18]. The increasing water storage level submerged 256,400 mu (1 mu

0.067 ha) of cultivated and garden land, 65,800 mu of forest land, and 6.24 million m

2 of buildings, resulting in large scale resettlement led by the developer and government. The official decision of moving or not was detailed to each household, while the relocation distance was designed according to relevant villages’ environmental capacity. Thus, most of the affected people were only given the right to know instead of the right to choose, which enlarged the potential social risks. Eventually, from 2009–2012, approximately 224,000 rural distant-resettlees were moved outside of the reservoir area to more than 50 counties, mainly in Henan and Hubei Provinces. In addition, approximately 315,900 stayers (85,000 nearby-resettlees and 230,900 non-movers) were left behind in the rural regions of the reservoir area distributed in Xichuan County in Henan Province, Wudangshan Special District, Danjiangkou City, Yun County, Yunxi County and Zhangwan District in Hubei Province [

23,

31].

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. In

Section 2, the background knowledge and theory basis are presented. The research area and data collection processes are described in

Section 3. The results of the comparative analysis are given in

Section 4. In

Section 5, the findings are interpreted and the implications and recommendations are presented. The concluding remarks are presented in the final section.

3. Methods

This research is a qualitative analysis, while some quantitative data is used to replenish the description. Evidence of this case study came from two instances of fieldwork in Henan and Hubei Province, China (

Figure 1) and an analysis of secondary documents. For the fieldwork, multiple methods were employed involving questionnaires, in-depth interviews and site observations. The questionnaire and its application were designed by an expert team to gather quantitative data related to household demographics, land assets, facilities, incomes, employments, and emotions, etc. The interviews were conducted to obtain more concrete and flexible information and each interview lasted for at least 30 min. In the interview records, the identities of “affected farmers” and “local officials (so-called cadres)” were separately marked with the characters “a” and “c”. The field logs were employed to document observations. To protect the privacy of the study participants, the names of all villages are abbreviated, and the respondents, unpublished reports and the titles of the officers will remain confidential.

From 10 July to 1 August, 2015, the first fieldwork was conducted. According to the sample selection criteria listed as

Table 1, a total of 12 counties were selected. Then, similar to the county selection, we chose 39 typical villages (29 distant-resettlee villages and 10 stayer villages) of which 20% of all households were investigated. A total of 517 valid questionnaires were provided to the researchers by 382 distant-resettled households and 135 stayer households. The demographic characteristics of the respondents indicated that the household size was approximately 4.9 people; the male–female ratio was 1.09. Meanwhile, at least one village official from each village was interviewed and another 35 distant-resettlees and 10 stayers were randomly interviewed at their homes or workplaces.

From 26 June to 2 July 2019, the first author conducted another survey involving 2 stayer villages (YL and LLJ) and 2 distant-resettlee villages (MN and YG) chosen from the earlier survey sites to obtain more detailed information. During this time, 42 respondents (distant-resettlees: stayers = 10:11) ranging in age from 35 to 60 years (48.8 on average) were interviewed. The study participants were employed in the following four types of occupations: eight were village congress members, 27 were smallholder farmers, four were large-holder farmers, and three were managers of village enterprises. Each interviewee was introduced to the researchers by the prior interviewee through snowball sampling. The sampling method was conducted when we accidentally entered the villages; any other more stringent sampling method was inevitably limited without contacting local officials in advance. Nevertheless, our random points of access allowed for the reordering of acquaintance-based narratives when somebody was not at home. Thus, the homogenised risk of the snowball method would be partly reduced.

In addition to the fieldwork, secondary data was gathered based on long-term team contracts with local governments and engineering departments. Two databases were most helpful for our analysis [

31]. One database contains information from 2012 and 2017, of which the data was provided by 1162 distant-resettlees and 579 stayers from 271 villages in 25 counties. The results of this database shed light on the socio-economic characteristics of the families affected by reservoir-induced resettlement, especially the comparison of the circumstances between the resettlement completion stage and the post-resettlement stage after five years. Another database was established in 2013 [

24] that generally investigated the demographic characteristics, land, and living conditions of non-movers in the Danjiangkou Reservoir area. It covered 417 non-moved villages in 40 townships in the reservoir area. The database was compiled from a landmark survey designed to better understand the non-movers.

4. Results and Analysis

Based on the multiple elements identified in the resettlement impact literature, the main intergroup differences between the distant-resettlees and the stayers are analysed, but the common characteristics (

Table 2) are not discussed due to space limitations. Overall, through the resettlement of Danjiangkou Reservoir, the distant-resettlees benefit more than the stayers and the group disparities come from external factors rather than internal ones.

4.1. Land Assets

The stayers were at risk of reduction in arable land acreage and quality. The average arable land owned by each of the stayers was 0.92 mu, slightly higher than the warning line—0.8 mu per capita [

52]. Specifically, 29% of the non-movers (67,000 people) had less than 0.8 mu arable land; and even worse, a survey indicated that the nearby-resettlees had an average of only 0.27 mu [

53]. Compared with the stayers, the distant-resettlees were compensated with more land according to the average holding of host communities (

Table 3).

In terms of land quality, there was aggravation of soil erosion in Danjiangkou Reservoir area since 2010 [

54], which aligns with our finding that the stayers suffered from the underproduction of cereal (

Table 3). Moreover, after the heightening project, any seasonal planting in the newly formed hydro-fluctuation zone was strictly prohibited, which meant that there was not much productive land available to the stayers.

Moreover, the land transfer rate and land utilisation efficiency of the stayers was lower. The infertility and fragmentation of land in the reservoir area inhibited the intensive land use and resulted in a lack of land tenants. The survey indicated that the land-transfer fee in stayer villages was about 100–200 CNY (on 30 December, 2020, 1 CNY ≈ 0.153 USD) per mu per year, which is 2–3 times less than that in distant-resettlee communities. Thus, the stayers were unwilling to transfer their land (

Table 3) even if they cannot efficiently use it. Moreover some of them with “inconvenient cultivation radius” (Interviewee C0615) even chose to abandon farmland, which was paradoxical in the stayer villages with scarce land.

Furthermore, China’s one-size-fits-all forest program “grain for green”, which imposed restrictions on profitable planting and farming activities on sloping farmland with a gradient exceeding 25 degrees, greatly influenced the stayers who generally live in mountainous areas. Interestingly, during our fieldwork, we observed abandoned forestry lands that were not exploited due to controversial ownership issues. Some distant-resettlees with “Certificates of Forest Property” petitioned as groups to be compensated for their abandoned woodland in the reservoir area. Such actions of distant-resettlees made the stayers feel “that forestland is a battlefield...it may be reclaimed or charged” (Interviewee A0615). Thus, the stayers were compelled to abandon the use of some forestland. As an official stated, in certain stayer villages, up to a quarter of the available forestland was not used properly (Interviewee C0515). Therefore, the forestland left by the distant-resettlees would not be a reliable remedy to address the land lost by the stayers.

4.2. Housing Conditions

It was found that the housing conditions were not equally equipped between the two groups (

Table 4). In light of the principle of housing compensation reaching pre-resettlement levels, both distant-resettlees and stayers’ housing areas should have been 24 m

2 per capita. However, more distant-resettlees voluntarily purchased additional space while fewer stayers did the same resulting in gaps in our measurement results. Concerning the disparities in domestic facilities, while the stayer villages were still underdeveloped, many distant-resettlee villages were supported to reach a higher standard. The coverage of clean energy was counted here, as it remained one of the most important hindrances to household development in rural China [

55].

However, some of these statistical figures are limited in their ability to depict the true status. For instance, the notes obtained during the fieldwork suggest that the popularity of new-style toilets and heating equipment in distant-resettlee households was exaggerated, as the real usage rate is low due to a mismatch with rural resident demand. The underlying causes are the risk aversion of smallholding farmers and their extreme reluctance to increase their daily costs for these “new gadgets”.

Note: The 111% in “clean energy” column indicates that the average distant-resettlee household could access 1.11 forms of clean energy including electricity and natural gas.

4.3. Finances

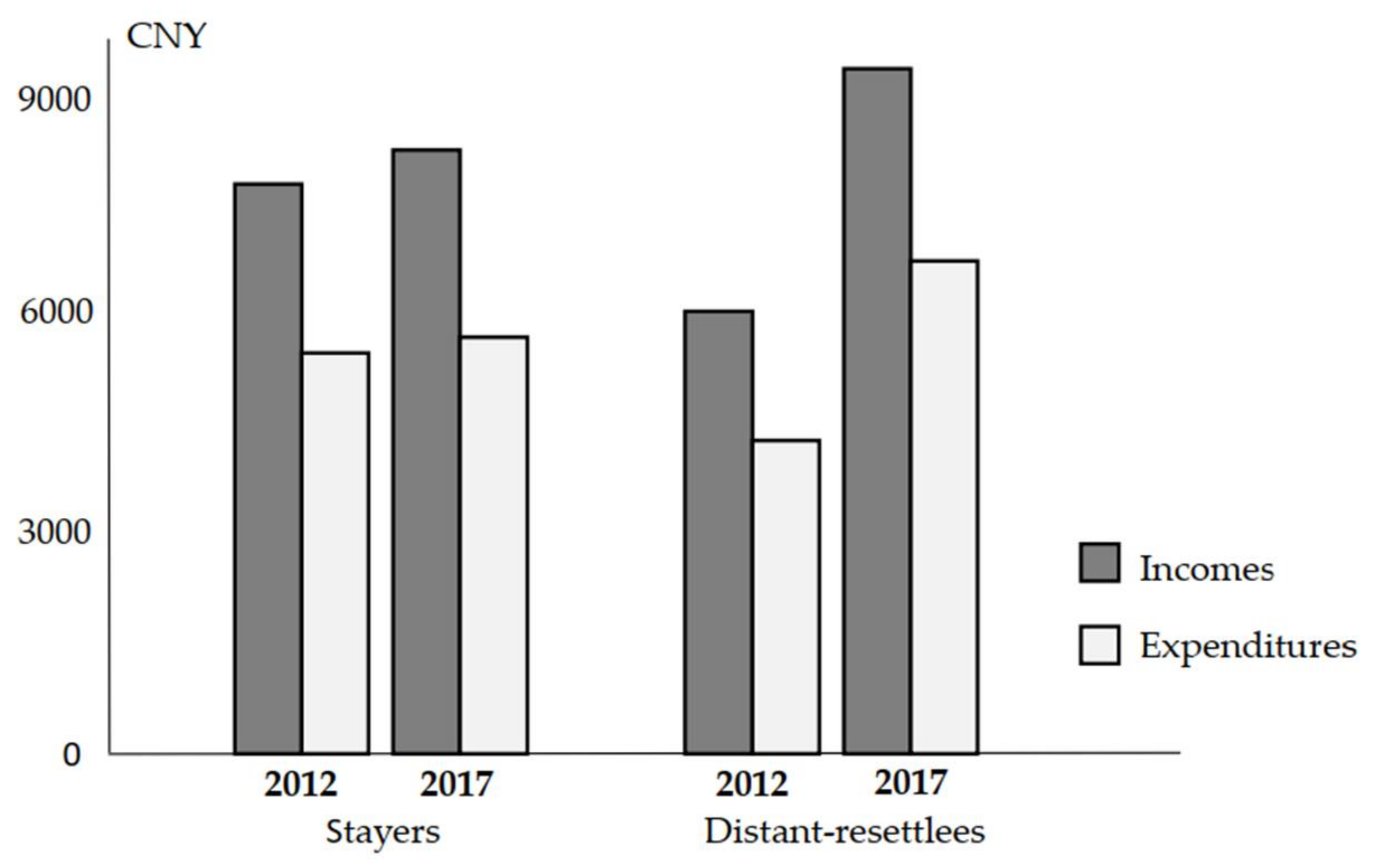

The stayers, especially the non-movers, were more vulnerable than the distant-resettlees in terms of finances. As shown in

Figure 2, while the revenue of distant-resettlees grew impressively, there was no significant increase in the income of the stayers. The distant-resettlees obtained 23% lower wages than the stayers at the end of the resettlement in 2012, but they recovered quickly and their incomes significantly surpassed those of the stayers in 2017. The expenditures of distant-resettlees and the stayers both presented a consistent trend as their incomes change and the ratio of expenses and revenue was stable at 75%. Such structural growth in income and expenditure reflects the following general conditions related to living standards: the growth in the incomes of the distant-resettlees effectively translated into improved living standards, while the living conditions of the stayers achieved minimal progress in the post-resettlement stage.

The lack of post-resettlement subsidies for over one-half of the stayers (mainly non-movers) was one reason for the overall income gap. There was obvious inequity in the “post-resettlement support policy for large and medium-sized reservoirs” [

28,

56] which provides continuous support of 600 CNY per resettlee per year whereas all non-movers are excluded from this type of support. According to the survey, 96% of the distant-resettlees claimed that they received the subsidy annually and would continue to benefit from the subsidy until the 2030s. However, approximately one-third of the nearby-resettled respondents said that the subsidy failed to arrive on time. At the local economic level, this subsidy is considerable, reaching 7–10% of the annual income of many families and directly affecting the livelihood and development potential of the residents.

4.4. Infrastructures and Services

Public facilities have been considerably improved in the distant-resettlee communities either during or after the resettlement program; however, most the stayers rely on outmoded facilities. Sun claimed that most of distant-resettlees considered their infrastructure, including roads (79.29%), home-energy (84.34%), television and internet signals (97.98%), medical care (81.36%), and schooling for children (85.35%), to have maintained or improved [

53]. In contrast, our data show that in the stayer communities, more than 200 service establishments including kindergartens, elementary schools, train stations, credit cooperatives, restaurants, inns, churches, etc., were closed due to resettlement and many other types of infrastructure impacted (

Table 5).

4.5. Industrialisation

In post-resettlement stage, there was a decrease in industrialisation in the stayer communities. To maintain water quality for the SNWD project, the Danjiangkou Reservoir area (the catchment area) was divided into water-source conservation areas [

57] since 2003. By 2014, more than 12 billion CNY of external investment was cancelled, about 890 enterprises with serious pollution discharge were closed or limited [

31] and 60,000 staff members lost their non-farm jobs. When large factories were closed, the downstream workshops lost their vitality and adaptability, leading to a decrease in industrialisation. To control the water pollution by non-point sources from the reservoir area, hundreds of enterprises involved in the turmeric processing, brick firing, and mining sectors, which significantly contribute to the local economy, were forced to file for bankruptcy because of their substandard waste treatment equipment. In addition, approximately 102,000 fishing cages were dismantled due to environmental considerations, which has had a large impact on aquaculture-based livelihoods [

58] and specialised fish-cuisine catering businesses.

In contrast, industrialisation increased in the distant-resettlee villages. On the one hand, the data reveals that local enterprises have been established in nearly one-quarter of distant-resettlee communities since the post-resettlement stage and many development projects have been added to the agenda. On the other hand, the industrialisation of agriculture was typically booming, as the flatland in the distant-resettlee villages is more suitable for mechanised farming and processing. The number of large-holder farmers in distant-resettlee villages has increased by 95%, and the production scale of each large-holder farmer has increased 1.6 times on average. These changes further promoted the intensification of agriculture and spawned more employment opportunities for farmers in the surrounding regions. One respondent (C0215) described the following:

“…before resettlement, there was only one large-holder household in our village, who mainly planted wheat and corn, with 4–5 casual labourers at harvest time... after the heightening project of Danjiangkou Reservoir, four agricultural co-operatives built greenhouses for shiitake mushrooms and employed dozens of seasonal labourers for fertilising and picking…”

4.6. Livelihood Strategies

The livelihood strategies of the stayers largely kept pace with their depressed local industrial structure. The downturn in the processing industries generated off-farm employment [

59] opportunities in these communities to support their livelihood. As a result, increasingly, the stayers have difficulty in properly arranging their time between the sowing and harvesting periods (Interviewee A1019). Moreover, the migration for urban employment, a common phenomenon in rural China, reflected stayers’ scarcity of local livelihood choices. Such employment-driven migration after the resettlement project has become the choice of 34% of the stayers, while this proportion was 26% in the distant-resettlee villages. As a by-product of such secondary population outflow, the number of local consumers has increasingly declined, which reduced the number of local labourers needed in service industries, e.g., restaurants or hotels. Thus, the trend of agriculture-dependent livelihoods was forced to be revived. However, in contrast to that in the past, the exodus of the able-bodied rural population has led to an insufficient labour supply in the stayer villages. Consequently, grain crops have become the priority rather than labour-intensive cash crops (Interviewee C0319). Fruit trees on hillside fields with gentle slopes have been replaced with labour-saving trees that can be used for timber or fuel.

In contrast, the livelihood strategies of the distant-resettlees have been enriched. Most of their previous economic activities were recovered, except for livestock farming and the courtyard economy, etc. Several new types of employment have gradually been created and the flexible policy situations in distant-resettlee communities have helped individuals and families develop an optimal livelihood portfolio. To help distant-resettlees restore the loss of their livelihood, grass-roots officials were encouraged to actively act as financial intermediaries: they used administrative means and their social networks to attract surrounding enterprises to distant-resettlee villages, which provided more jobs to distant-resettlees. To improve the employability of the distant-resettlees, governors also provided skills training and entrepreneurial guidance. Approximately 35% of the distant-resettlees admitted that they received training for welding, construction, repair and sewing or service industry-related skills that are pertinent for commerce, catering and community services. However, according to our latest survey in 2019, some distant-resettlees who received training stated that they “indeed took a stack of training certification but had no motivation to apply these new skills (Interviewee A0719, C0119)”. That is to say, those people who truly used newly-learnt skills to manage restaurants and tailor shops or to engage in a new livelihood strategy, such as leisure farming and e-commerce, still represented a relative minority in the distant-resettlee communities.

4.7. Emotions and Feelings

Feelings of insecurity and jealousy were reported by the members of the stayer communities, while such negative emotions were uncommon in the distant-resettlee villages. Specifically, nearly 65% of the respondents in stayer villages reported feeling lonely and insecure. Because of the mountainous habitation and sparse population, the neighbourhood networks in the stayer villages have been weakened and are vital for providing mutual care and spiritual support. One specific case that caught our attention illustrated this problem. In a stayer zu (literally means group, a subunit of village) in DZ Village with only four households, there was an old and sick female living far from others. Because she was very isolated from her acquaintances, her death was not found until 5 days later [

23].

Many stayers were no longer complacent about staying in the reservoir area, which had been what 95% of them expected [

53]. Because the positive meaning of “left” was seemingly changed by the fallout of the resettlement program. Some the stayers who did not receive housing improvements began to feel jealous of the distant-resettlees because of their prioritised housing treatment, as a majority of distant-resettlees moved into well-constructed new communities (xincun in Chinese), where the buildings are painted grey or white to illustrate the important positions of the inhabitants [

60], while over three quarters of stayers still live in their simple furnished houses.

In addition, the survey revealed that 55% of the stayers have a bleak outlook of their future. This finding was subtly triangulated by the daily conversations of the stayers, which were repeatedly centred around finding good jobs and negative comments regarding “declined lands”, the “heightened living cost”, etc. One of the stayers (Interviewee A1319) stated the following using a fatalistic tone, “we can barely raise our standard of living through hard work… why not idle at home?”

Positive expectations exist alongside the grumblings in the distant-resettlee communities. Less than 7% of the interviewed distant-resettlees stated that they felt insecure or jealous. Conversely, of these distant-resettlee villagers, 78% believed that they would have a better future as they retained their ambition to make money diligently and catch up with the host communities. However, on account of moving to more unfamiliar places, the distant-resettlees usually felt more affected. According to the survey, 67% of distant-resettlees had never visited the local households of receiving communities. The inadaptability of the social network resulted in unsatisfied distant-resettlee villages. As two interviewees (A0415, A1519) said, “yes, we become better in some ways... but we are unfamiliar with the local neighbours here…we prefer to make contact with fellow-townsman…we indeed want to revisit the reservoir area to meet old friends, but it is too costly”.

5. Discussion

5.1. Why Are Stayers Generally Worse Off?

Overall, the underlying reason for the worse conditions of stayers in Danjiangkou reservoir area is cognitive inequality. Development orientation, resource distribution, and responsible entities further worsen the effects. For example, environmental protection is prioritised over the economic development in stayer communities and the stayers are influenced by depressed industrialisation projects and restricted livelihood strategies. The misallocation of resources directly leads to the stayers’ dilemma in land, housing, and compensation. The lower-level responsible entities for the stayers (especially non-movers) make the public infrastructure less resourced. Hereinto, the produced results interact further and provoke emotional impacts.

5.1.1. Cognitive Inequality

There exists cognitive inequality between the distant-resettlees and stayers. While the stayers are impacted by ignorance and indifference, the distant-resettlees receive broader attention. First, the decision rights of the resettlement scheme was legally transferred to the administration and planning departments [

61] according to Decree 471 of the State Council, which was the regulation for the Danjiangkou heightening project resettlement. Thus, respecting the safeguard of social stability, the government tended to put more weight on distant-resettlees than on nearby-resettlees. Moreover, given the financial and historical issues, no targeted regulation has been promulgated for the non-movers, which means there is a lot of flexibility for decision-makers to deal with this under-defined population in China. Moreover, since the Danjiangkou project was not financed by any international organisation, the present international standards of project-associated resettlement actions were not strictly followed. Some proposals regarding the trigger points of proceeding resettlement and compensation (e.g., in Performance Standard 5 on land acquisition and involuntary resettlement (PS5) [

62] and environmental and social standard 5: land acquisition, restrictions on land use and involuntary resettlement [

63]) are selectively carried out in this project.

The policy-driven cognitive inequality is deeply entrenched in various levels of administrations. A reflection is that, during the interactions with county governments, the researchers were encouraged to neglect the stayer villages and concentrate on the well-managed distant-resettlee communities. Moreover, the expert suggestions of dismissing the special treatment to resettlees bring little effect to eliminate such cognitive inequality, as the slogans regarding the distant-resettlees’ tremendous contributions are still common to see. The government’s disregard of the stayers is inadvertently perpetuated by outsiders, leading to the formation of a biased consensus that “distant-resettlees deserve special treatment”. For example, the focal point reporting in news media have reinforced the habitus of the weak and inherent crucial position of distant-resettlees. In turn, such actions strengthen the misidentification and neglect of the stayers even long before resettlement began.

5.1.2. Polarised Development Orientation

The difference in regional development orientation exacerbates the gaps between distant-resettlees and the stayers. Driven by the preferences of government, economic recovery has become a political and fundamental task in distant-resettlement communities. Due to economic development-related goals and the prioritisation of sustainable development, the well-conditioned settlements for distant-resettlees are selected in advance. Moreover, in the post-resettlement stage, distant-resettlee communities are provided various extra measures that are conducive to economic development from which the distant-resettlees can benefit.

In contrast, environmental protection is prioritised over the development of the stayer communities. Since reservoir areas were set as environmental protection zones, the rights of the stayers to economic development have been fettered, for instance, most of the development projects was frozen, and all “pollution-driven” factories faced increased taxation and penalties. Therefore, the industrial structure of the stayer communities are greatly limited. Did the stayers share the dividends of environmental protection? The answer is almost negative in terms of the results. In other words, the stayers are protecting the environment for others at the expense of their own development rights. This is because the key benefits of the Danjiangkou mega-project are externalised to drier northern China in the national interest [

64] while the costs of the project are unfairly borne by the stayer communities. It is concluded that such behaviour is not consistent with the principle that any sustainable development of one region must not come at the expense of exploiting another. The polarised development orientation of “environment first” and “economic priority” has been potentially misused as a manipulative governance approach and an excuse to cover up imbalances in regional development.

5.1.3. Misallocation of Resources

The resources are misallocated between the distant-resettlee and the stayer villages due to double-standard application that promote developmental resource flows to the distant-resettlee communities. As Sen stated that the food crisis is not due to the lack of food, but from lacking just mechanisms for distributing it [

65], this opinion is seemingly true for the shortage of other resources. By examining how land, the most crucial resource in rural China, is subject to unfair distributions, we tend to gain an insight into why the stayers are at risk in multiple aspects.

The per capita land of distant-resettlees is approximately 1.6 times the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO)’s warning line [

52]. However, the outmoded standard of “0.5 mu basic ration grain field per capita in southern regions in China” [

23] is still unfairly applied to many of the stayers. Because of the poor conditions of the land, thousands of stayers are forced to migrate for work, which consequently results in labour loss in the stayer villages and potentially amplifies unequitable resource allocation. In distant-resettlee villages, relatively sufficient allocation of resources helps maintain permanent residents and enables them to develop alternative livelihoods. The misallocation of resources is not only reflected in the associated statistics, it also has ripple effects on people’s production modes and livelihood substitutions.

Furthermore, the problematic redistributive mechanisms potentially harm the host communities. In the case study, the reallocated land for distant-resettlees was not idle land in the receiving areas, but taken from local communities. The resettlement scheme [

23] states that for a host community with less than 2.0 mu of arable land per capita, 10% of the land will be paid to expropriate and compensate distant-resettlees; and in communities with more than 2.0 mu per capita, the occupation proportion is up to 20%. Thus, the resource distribution mechanisms used to preserve the prioritised benefits of distant-resettlees is actually a type of encroachment on local interests and with the “help” of the unequitable policy, the distant-resettlees act as invaders and have secondary impacts on the host communities.

5.1.4. Distinct Responsible Entities

The considerable disparity among responsible entities leads to many intergroup gaps, typically in rural infrastructure. The needs of stayers are under the charge of grass-roots level governments, while senior authorities are often concerned regarding the services provided to distant-resettlees. This has been rooted in China’s mixed public goods supply system [

66] for a long time, especially in those regions that are not well off. The village-level investments, such as that for local roads and educational and cultural facilities, are never the responsibility of the senior government. However, because the distant-resettlee group is subject to political favouritism, much of the infrastructure provided to distant-resettlees is due to the influence of county-level governments or higher. Therefore, the investment and professionalism of infrastructure are better guaranteed, allowing distant-resettlees to have more advanced conditions than the stayers.

In contrast, a grass-roots government is “conventionally” responsible for the infrastructure of the stayers. Since the tax-sharing reform started in 1994, China’s local finance led to a cash-strapped regime and desperation. Therefore, some infrastructure construction and upgrading were recklessly delegated or outsourced to some village-level autonomous organisations. The outcome is that public infrastructure in the stayer villages is limited to the most basic necessities, according to the polls answered by village leaders. Due to the lack of government guidance, much of the infrastructure is frequently regarded as “extravagant demands” [

66]. This judgment could be because in the stayer communities, agricultural facilities are equipped and updated, but there is a serious and continuous shortage of development-related public goods, such as schools, nurseries, cultural auditoriums, etc.

5.2. Implications and Suggestions

According to many documents (e.g., [

67]), the grand resettlement (2009–2012) in Danjiangkou Reservoir is viewed as a showcase of good practices in China. However, such argument largely rests on the one-sided consideration of quick-finish and basic compensation, while the development of nearby-resettlees and the overall restoration of non-movers are neglected. Even such a mega-project under the spotlight is surprisingly problematic—it could be speculated that the plight of stayers is more prominent near medium-sized reservoirs, which lack public supervision. Thus, the stayers’ dilemmas and relatively unequal status is by no means limited to the Danjiangkou area, but is a general phenomenon in China.

The distant-resettlees in this research are not to be viewed over-optimistically. Some of their modern family facilities were not fully utilised and the training they received was not well converted into alternative livelihoods with long-term social network issues encountered. Furthermore, 14% of the distant-resettlees (about 30,000 involuntary individuals) were not once-off settled, but moved back to the reservoir area spontaneously [

68]. They were originally evicted by political mobilisation and failed to readapt in resettlement sites.

While we have brought the stayers, especially the invisible non-movers into consideration, the scope of the social “losers” in a reservoir project could be extended further. Therefore, we suggest that it may not be worthwhile to discuss which group is more vulnerable from a theoretical perspective. That is to say, the distant-resettlees, stayers and host households should all be classified as vulnerable groups. Following this, an initial check and process monitoring on the economic, social, and environmental impacts of each group should be conducted so that appropriate long-term support and timely adjustments can be made.

Respecting the main objects of this study, we advise a balanced treatment for both the stayers and distant-resettlees. The adjustment of policies towards the stayers or distant-resettlees should be prevented from working against the other group to produce conditions that consistently advantage some while disadvantage others. This relies on reversing the philosophy penetration of “distant-resettlee priority” into all corners of resettlement practice and by empowering lower-level governments and reservoir developers to have fact-based and rational autonomy regarding the stayers and distant-resettlee issues. Specifically, necessary and formative assessment of the stayers by resettlement must be opened to agencies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Further, channels connecting media and vulnerable groups should be provided to highlight the role of public supervision. Moreover, it is recommended to treat the stayers under different living conditions distinctively. Financial compensation (not only cash) and assistance measures should be implemented to the stayers alongside fundamental living conditions—secondary development-induced resettlement is supposed to assist stayers living in extremely impoverished conditions or suffering from human rights violation [

69].

The issue of stayers and distant-resettlees is not limited to China and may be universally spread on a very large scale. As long as a reservoir project cannot resettle all members of its affected communities, complicated situations and inherent connections usually exist between the leavers and stayers. While international standards are not always followed [

26,

62,

63], the “undercoverage” of affected people is common to see, especially in the developing economies or regions with dense populations and rapid hydropower development, e.g., Brazil, Southeast Asia, and some other countries who are participating in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Moreover, as the potential priority of the distant-resettlees exists in China, a prejudice may occur everywhere. Thus, it is helpful to take regional cultural and social socio-political milieu into consideration, and promote international standards to guide localised practices.

5.3. Research Limitations and Outlooks

Although this study contributes to the understanding of the stayers in the reservoir-induced resettlement literature, it has some limitations. First, our comparative framework combines the nearby-resettlees and non-movers because of their similar dwelling areas and developmental bases, but this framework provides only a few details regarding the differences of post-resettlement support and displacement experience among the stayer groups, especially on their housing conditions and finances. Future research might specifically consider the two subgroups of stayers.

Second, to show a holistic picture of the stayers we defined in this preliminary study, several databases have been pieced together. In light of the latent reliability mismatch between these databases, we conservatively conduct descriptive research rather than a quantitative analysis. Even so, our survey content is not exhaustive and the analysis on other affected groups like host communities tends to be fragmented. Thus, more studies with cohesive research design and statistical methods are required.

Third, some other subdivided groups are worth exploring further in China’s reservoir context. For instance, the distant-resettlees who moved from resettlement sites to big cities or back to the reservoir area in the post-resettlement stage and the nearby-resettlees who were reallocated land, but lived in situ (named “productive resettlees”). Moreover, another noteworthy group is the population who suffered from the resettlement during the initial stage of Danjiangkou in the 1950s. The past resettlement experience might have generated prejudiced opinions and confused memories for some aged residents and their families. Thus, monographic research on such unique groups are needed.

6. Conclusions

To comprehensively understand the impacts of reservoir-induced resettlement on local residents in China, this study is anchored on a comparison between those who resettled outside of the reservoir area and the group left inside the region. We tentatively define nearby-resettlees and non-movers as “stayers” to contrast with the distant-resettlees. Considering the relative priority of distant-resettlees in China’s reservoir praxis and the existing impact analysis frameworks around project-induced resettlement, a case study was conducted in Danjiangkou Reservoir to explore the disparities in the impacts on stayers and distant-resettlees.

The findings indicate that stayers are generally faced with many grave problems in terms of land assets, housing conditions, finance, public infrastructure, industrialisation, livelihood strategies, and emotional impacts, while many distant-resettlees are provided opportunities for better development and experienced more positive changes in the post-resettlement stage. The results challenge the broadly held perception that distant-resettlees are the most vulnerable group influenced by reservoir projects and question whether there should be some more flexible criteria to the international discipline of “avoiding and minimising displacement”. This is meaningful for the current knowledge of the characteristics of a broader range of affected groups and to critically understand the gaps between local practices and international norms.

While four aspects of the underlying reasons are contended, they are not all-inclusive. What we can draw from them is that the political imperative for social stability drives the responses and priorities of China’s resettlement. This can be reflected in the paradoxical co-existence of improved yet problematic resettlement outcomes due to a political nature that seeks stable governance and is oriented to achievements, which are evaluated by one’s superior. Moreover, in view of the hydropolitics, many interesting remarks could be put forward regarding the governance of resettlement, the balance between resettlement interest and the greater public interest as well as the trade-offs among economic, environmental, and social factors, etc.

Lastly, this research does not expect to shift the “most vulnerable tag” from distant-resettlees to the stayers because how people are impacted can differ. We suggest that successful resettlement action should consider all groups influenced as potentially vulnerable populations corresponding to studies on each of these groups. Drawn from this statement, some policy suggestions based on the unbiased principle are provided for both China and other countries. While this study may contribute to adding another chapter to the reservoir-induced resettlement literature, it is also instructive and generalisable to other project-induced resettlement activities. The general lesson is, where there is project-induced resettlement, there might be utilitarian politics and unequitable benefits, which is the springboard of the ongoing resettlement research for enriching the theories and improving the practices.