Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration in Violent Conflict Settings

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Definitions

3. Research Methodology and Methods

FFP LA as Part of Larger UN Programs

| Country | UN Entity | Conflicting Parties | Internally Displaced Persons/Conflicts | Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darfur/Sudan | UN-African Union Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID)-peacekeeping mission | Host community Internally Displaced People (IDP) | 2.6 million | Good offices agreements for access to land, technical assistance |

| UN-Habitat | ||||

| Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo) | UN Organization Stabilization mission in the DR Congo (MONUSCO)-peacekeeping mission | Big farmers | 4.49 million; Masisi territory case study 4600 | Good offices, human rights, protection of civilians |

| Customary owners | ||||

| Honduras | UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) | Criminal gangs | 174,000 20 urban municipalities (2004–2014) | Documenting forcibly abandoned houses |

| Displaced | ||||

| people | ||||

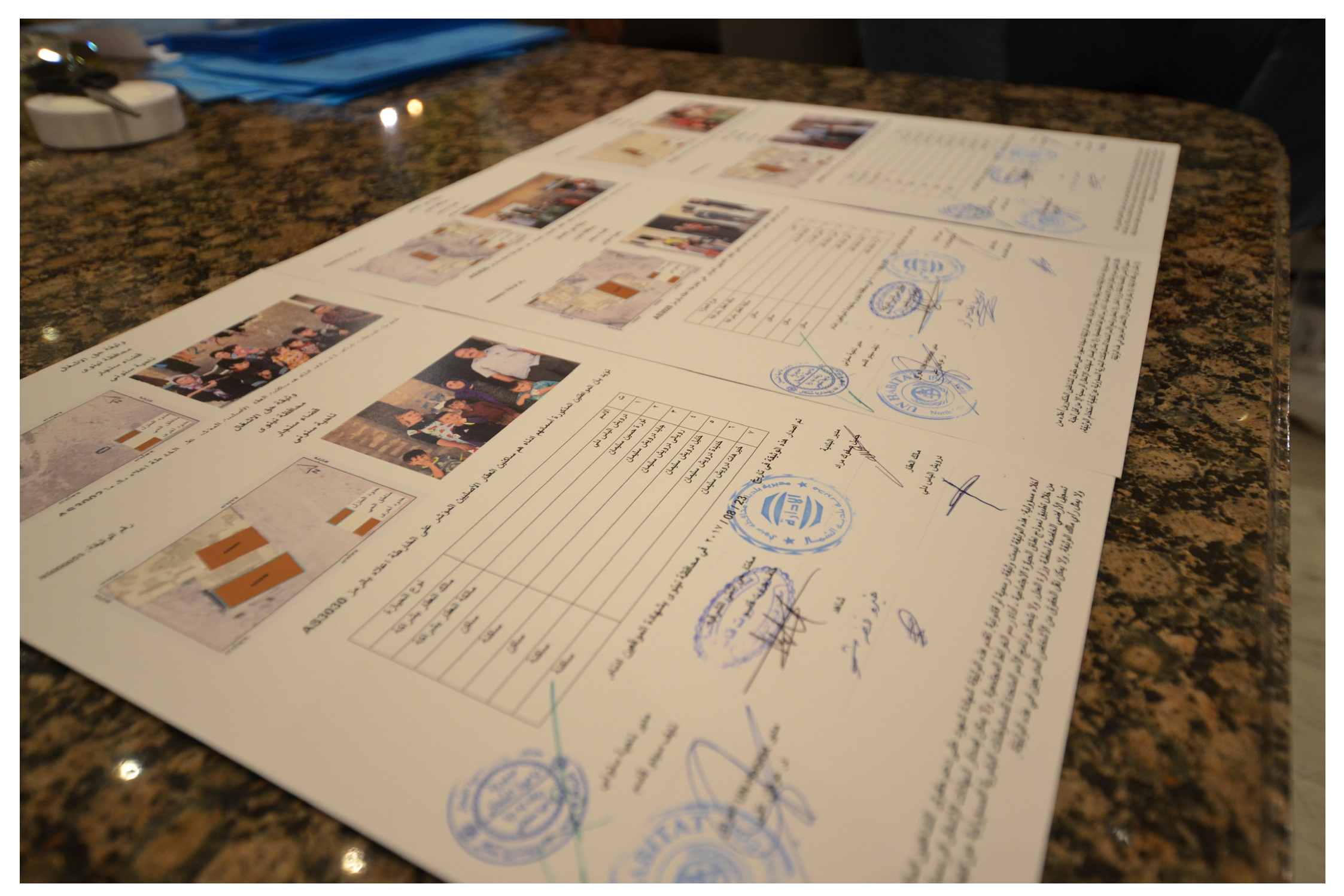

| Iraq | UN-Habitat | Different ethnic/religious groups | 3.3 million; 250,000 Yazidi from case study | Land certificates, GIS, house rehabilitation |

| Peru | UN Development Program (UNDP) | Extractive industry indigenous people | 200 conflicts a year (2006–2016), 70% linked to extractives | Territorial development agreement |

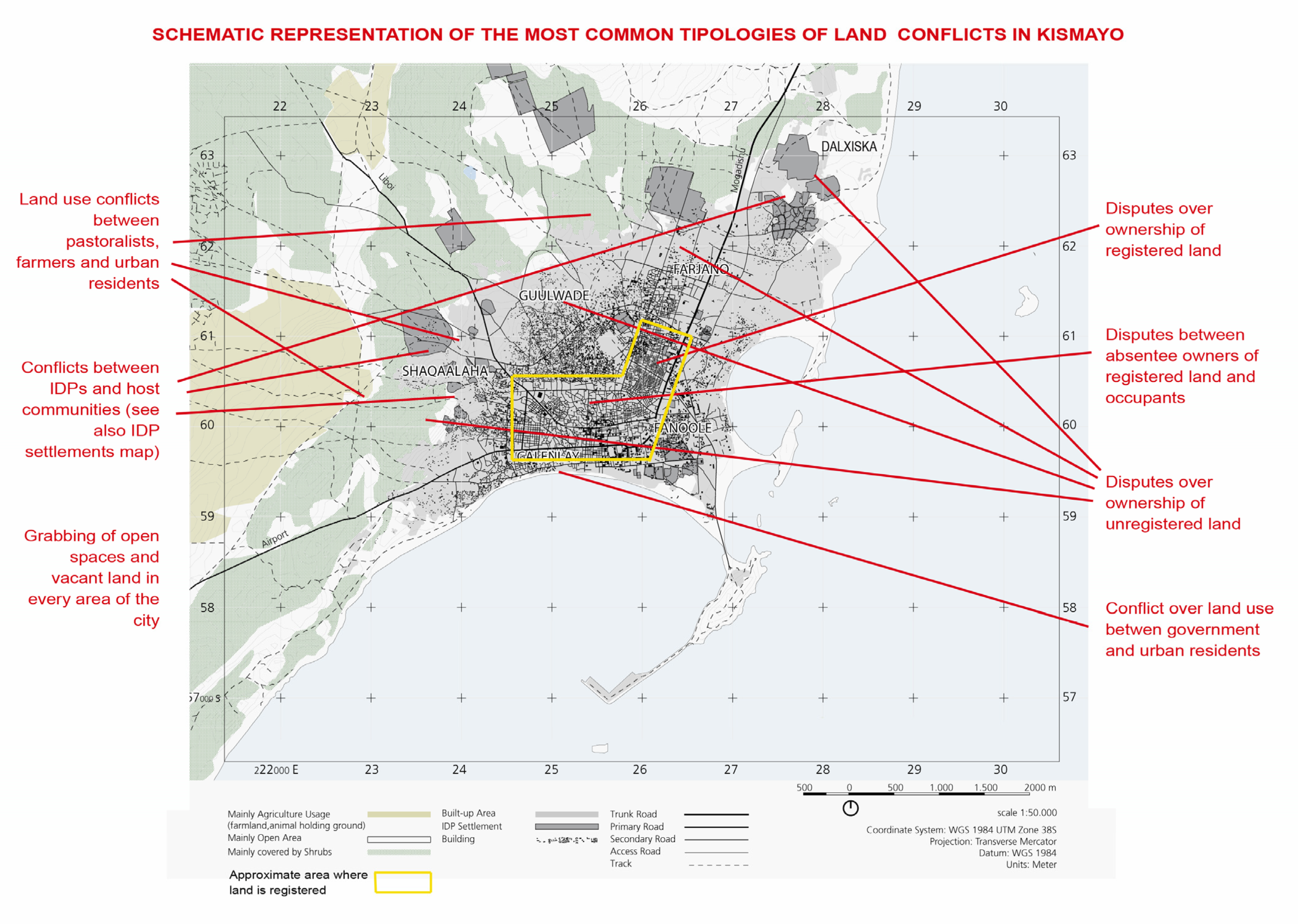

| Somalia | UN-Habitat | Pastoralists, farmers, urban residents, owners and occupants | 1.1 million for the whole of Somalia; at least 44,000 for case study area | Land policy process, LA recommendations |

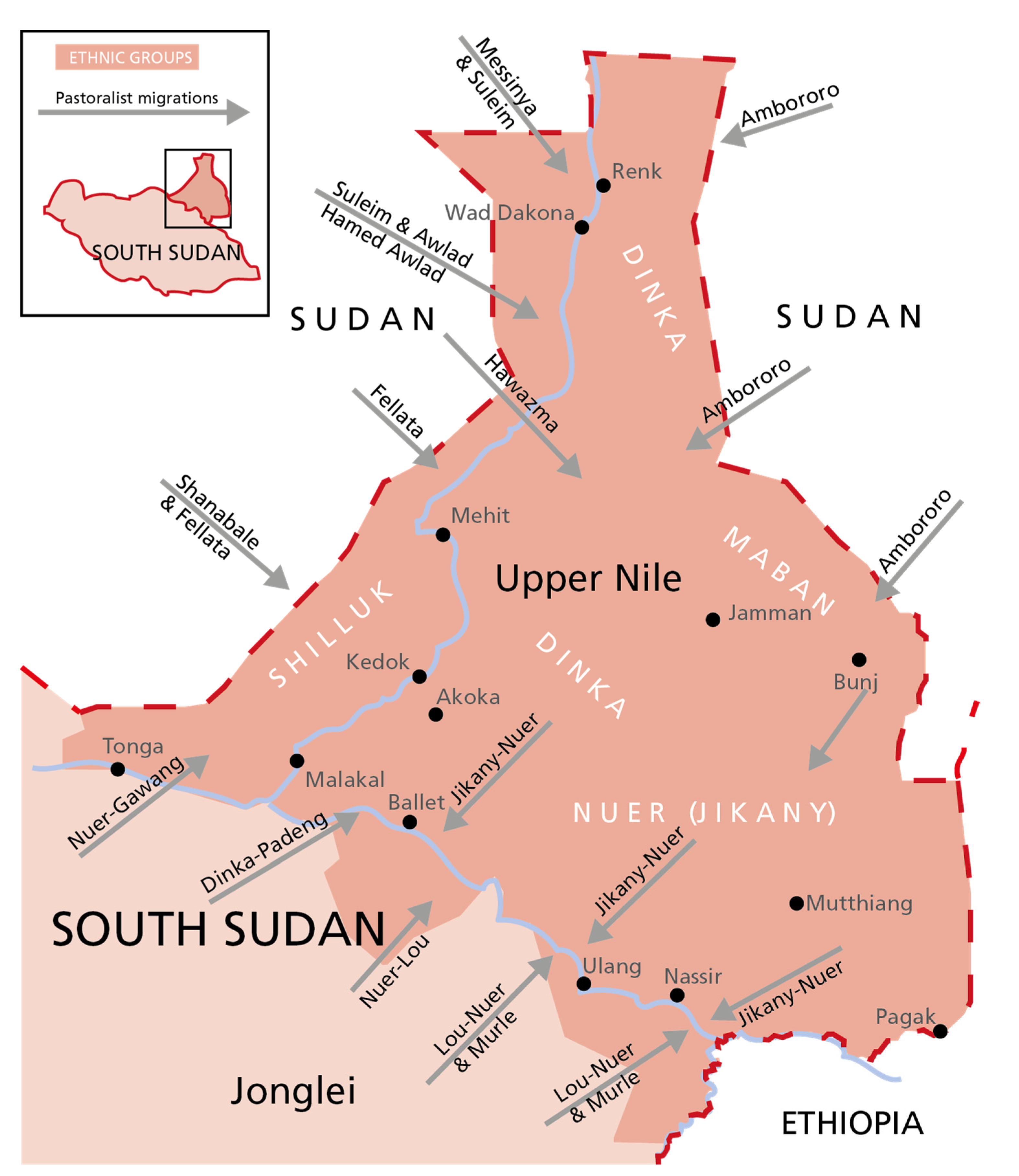

| South Sudan | UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS)-peacekeeping mission | Cattle owners, farmers, cross border | 1.94 million South Sudan; 250,406 IDP Upper Nile case study | Territorial agreement |

4. Findings

4.1. Building on Land Administration Frameworks

4.2. Building on Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration Frameworks

- Incremental building on existing capacity and legal frameworks. Focusing on adjusting regulations as much as possible as new laws can take years.

- Rapid identification and use of government-owned land for rapid delivery of security of tenure to returnees.

- Reducing planning standards and undertaking one stop planning for rapid planning approvals. This is vital for upgrading informal settlements and IDP camps.

- Reducing surveying and registration requirements. This includes allocating unplanned non-surveyed land, called Grade IV in the state-level statutory system, thereby excluding the final registration step in the Judiciary at national level. Using group areas instead of individual plots. For example, the allocation by customary authorities of land for villages for returnees can be registered as a community based right (Plot 1), where instead only the outside boundary of the village is registered.

- Legalizing the customary land management system.

- Delivering serviced land rapidly in urban areas by increasing the amount of serviced land by minimizing the time taken to deliver the services, while ensuring minimum standards.

- Improving information management to track large-scale returns and developing strategic plans for the overall management of returns, including through regional planning, land management and for conflict analysis.

- Identifying a range of dispute resolution mechanisms based on the assessment of possible return areas and conflict hot spots, and the tenure and land document types found in these areas. Using land-dispute resolution tools such as mediation, territory-wide land use agreements, and dispute resolution at the plot and territory levels [13] (pp. 9, 19, 30, 52–55, 79–84).

4.3. Building on Post Conflict Land Administration Approaches

4.4. Land Governance and the UN in Violent Conflict Contexts

- The targeted clarifying and coordinating of LAS government functions across national, state and local levels for a specific humanitarian purpose such as voluntary returns.

- Amending regulations rather than developing new laws.

- Ensuring due diligence and minimum standards to protect people and their land rights.

- By using land information management, tracking trends of people returning to their areas of origin or other areas, conflict and dispute resolution patterns, and to identify areas that need additional land-related peace-building interventions. This also requires early warning systems at the community level and along migratory routes.

- Strengthening the Land Commission to “perform its function and mandate to arbitrate between willing contending parties on land claims, (and) assess appropriate land compensation” [13] (pp. 82–85).

- Ensuring the processes for addressing housing, land and property challenges in a humanitarian setting do not discriminate against women [9] (p. 70).

- Supporting women’s access to land and tenure security across the full range of tenure types and the identification of the most viable tenure options that can reach the greatest number of women in the shortest time [13] (pp. 68, 73), as well as support to their access to justice mechanisms [9] (p. 70).

- Providing special provisions for women, particularly widows and women-headed families of returnees, in customary areas where their legal status needs to be protected. Women-headed households and widows should be considered as heads of households in the customary system with a right to access land [13] (pp. 75, 79, 84). This may also involve support for the provision of civil documentation [9] (p. 70).

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR). Figures at a Glance. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/en-ie/figures-at-a-glance.html (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- United Nations. Peace, Dignity and Equality on a Healthy Planet, Peace and Security. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/peace-and-security/ (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- United Nations Secretary General. The Guidance Note of the Secretary-General The United Nations and Land and Conflict; Endorsed on the 15th March 2019. Available online: https://gltn.net/2019/03/15/guidance-note-of-the-secretary-general-the-united-nations-and-land-and-conflict-march-2019/ (accessed on 7 June 2020).

- UN-Habitat; Global Land Tool Network; International Institute of Rural Reconstruction. Land and Conflict: Lessons Learned from the Field on Conflict Sensitive Land Governance and Peacebuilding; UNON: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; pp. 1–126. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Haar, G.; van Leeuwen, M. War-Induced Displacement: Hard Choices in Land Governance. Land 2019, 8, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Global Land Tool Network. Available online: https://gltn.net/ (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Decorte, F.; Augustinus, C.; Lind, E.; Brown, M. Scoping and Status Study on Land and Conflict: Towards UN System-Wide Engagement at Scale; UN-Habitat/Global Land Tool Network, Working Paper May 2016, Report 5/2016; UNON: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations; United Nations Security Council. Report of the High-Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations on Uniting Our Strength for Peace: Politics, Partnership and People; A/70/95, S/2015/446; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–104. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2015/446 (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Tempra, O. Land and Conflict in Jubaland Root Cause Analysis and Recommendations; UN-Habitat/Global Land Tool Network and Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs; UNON: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; pp. 1–84. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office of the High Commission for Human Rights (OHCHR). Transitional Justice and Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; 11 April 2014, HR/PUB/13/5; United Nations: New York, NY, USA; Geneva, Switzerland; Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/5347cbe74.html (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- Collins Dictionary. Available online: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/extralegal (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- UN-FAO; UN-Habitat. Towards Improved Land Governance; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Abukashawa, S.; Augustinus, C.; Mustafa, A.; Tempra, O. Darfur Land Administration Assessment—Analysis and Recommendations; UN-Habitat Sudan/Global Land Tool Network; UNON: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020; pp. 1–91. [Google Scholar]

- Scopus Preview. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/home.uri (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Global Land Tool Network. Land and Conflict Forum; Developing an Issue-Based Coalition, Final Draft, Internal Document; UN Gigiri Complex, New Office Facility: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat; Global Land Tool Network. Annual Report 2015; UNON: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015; pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Molen, P.; Lemmen, C. (Eds.) Land Administration in Post Conflict Areas: Proceedings of a Symposium held by FIG Commission 7, Cadastre and land management on 29 and 30 April 2004 at the European Headquarters, Palais des Nations, Geneva, Switzerland; International Federation of Surveyors: Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2004; pp. 1–216. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Access to Rural Land and Land Administration after Violent Conflicts; FAO Land Tenure Studies 8; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2005; pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. From Emergency to Reconstruction a Post-Conflict Land Administration and Peace-Building Handbook; Series 1: Countries with Land Records; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2007; pp. 1–102. [Google Scholar]

- Todorovski, D.; Zevenbergen, J.; van der Molen, P. Land Administration in Post Conflict Contexts. In Advances in Responsible Land Administration; Zevenbergen, J., De Vries, W., Bennett, R., Eds.; CRC Press, Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Jossam, P.; van der Molen, P.; Boerboom, L.; Todorovski, D.; de Vries, W. Displacement and land administration. In Advances in Responsible Land Administration; Zevenbergen, J., De Vries, W., Bennett, R., Eds.; CRC Press, Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 235–249. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, I.; Enemark, S.; Wallace, J.; Rajabifard, A. Land Administration for Sustainable Development; ESRI Press Academic: Redlands, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–487. [Google Scholar]

- Enemark, S.; Lemmen, C.; McLaren, R. Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration Guiding Principles; UN-Habitat/Global Land Tool Network; UNON: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015; pp. 1–118. [Google Scholar]

- Alemie, B.K.; Bennett, R.M.; Zevenbergen, J. Urbanization, Land Administration, and Good-Enough Governance. In Advances in Responsible Land Administration; Zevenbergen, J., De Vries, W., Bennett, R., Eds.; CRC Press, Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Groenendijk, L.; Lemmen, C.; Bennett, R. Experiences and lessons from Mozambique. GIM Int. 2016, 30, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, R.M.; Alemie, B.K. Fit-for-purpose land administration: Lessons from urban and rural Ethiopia. Surv. Rev. 2016, 48, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Hilhorst, T.; Songwe, V. Identifying and addressing land governance constraints to support intensification and land market operation: Evidence from 10 African countries. Food Policy 2014, 48, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paradza, G.; Mokwena, L.; Musakwa, W. Could mapping initiatives catalyze the interpretation of customary land rights in ways that secure women’s land rights? Land 2020, 9, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustinus, C.; Barry, M. Land management strategy formulation in post conflict societies. Surv. Rev. 2006, 38, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzakuma, M. Sudan: Intercommunal reconciliation of land disputes in Darfur. In Land and Conflict, Lessons Learned from the Field on Conflict Sensitive Land Governance and Peacebuilding; UN-Habitat, Global Land Tool Network, International Institute for Rural Reconstruction, Eds.; UNON: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; pp. 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Weyns, Y. Democratic Republic of Congo: Interventions to prevent evictions of subsistence farmers communities. In Land and Conflict, Lessons Learned from the Field on Conflict Sensitive Land Governance and Peacebuilding; UN-Habitat, Global Land Tool Network, International Institute for Rural Reconstruction, Eds.; UNON: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; pp. 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- El Abdellaoui, J.; Padilla, L.N. Honduras: Protecting the housing and land of displaced persons. In Land and Conflict, Lessons Learned from the Field on Conflict Sensitive Land Governance and Peacebuilding; UN-Habitat, Global Land Tool Network, International Institute for Rural Reconstruction, Eds.; UNON: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Frioud, I. Iraq: Social tenure and house rehabilitation to support the return of Yazidis in Sinjar. In Land and Conflict, Lessons Learned from the Field on Conflict Sensitive Land Governance and Peacebuilding; UN-Habitat, Global Land Tool Network, International Institute for Rural Reconstruction, Eds.; UNON: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; pp. 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Thais, L.F. Peru: Dialogue to prevent and manage conflicts over the use of natural resources. In Land and Conflict, Lessons Learned from the Field on Conflict Sensitive Land Governance and Peacebuilding; UN-Habitat, Global Land Tool Network, International Institute for Rural Reconstruction, Eds.; UNON: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; pp. 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Okumu, J. South Sudan: Migration dialogues to prevent conflict between host communities and pastoralists. In Land and Conflict, Lessons Learned from the Field on Conflict Sensitive Land Governance and Peacebuilding; UN-Habitat, Global Land Tool Network, International Institute for Rural Reconstruction, Eds.; UNON: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; pp. 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sylla, O.; Tempra, O.; Decorte, F.; Augustinus, C.; Frioud, I. Land and conflict: Taking steps towards peace. Forced Migr. Rev. 2019, 62, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kivunja, C.; Kuyini, A.B. Understanding and applying research paradigms in educational contexts. Int. J. High. Educ. 2017, 6, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hasse, C. The multi-variation approach: Cross-case analysis of ethnographic fieldwork. Paldyn 2019, 10, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Unruh, J.D. Evidencing the restitution landscape: Pre-emptive and advance techniques for war-torn land and property rights reacquisition. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCHA. Democratic Republic of Congo: Internally Displaced Persons and Returnees (as of December 2017). Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/drc_factsheet_trim4_2017_en_07022018.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- OCHA. South Sudan: Humanitarian Shapshot June 2017. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/SS_170717_Humanitarian_Snapshot_June.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Tempra, O.; (UN-Habitat, Nairobi, Kenya). Personal communication, 2020.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Land Administration Guidelines, with Special Reference to Counties in Transition; United Nations: New York, NY, USA; Geneva, Switzerland, 1996; pp. 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- New Urban Agenda. Available online: https://habitat3.org/wp-content/uploads/NUA-English.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- FAO. Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forestry in the Context of National Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Global Geospatial Information Management (UN-GGIM). Framework for Effective Land Administration, a Reference for Developing, Reforming, Renewing, Strengthening, Modernizing, and Monitoring Land Administration; E/C.20/2020/29/Add.2.; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: http://ggim.un.org/meetings/GGIM-committee/10th-Session/documents/E-C.20-2020-29-Add_2-Framework-for-Effective-Land-Administration.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Abdul-Jalil, M.; Unruh, J. Land rights under stress in Darfur: A volatile dynamic of the conflict. War Soc. 2013, 32, 156–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Violent Conflict and Gender Inequality: An Overview; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 6371, pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lengoiboni, M.; Richter, C.; Zevenbergen, J. Cross-cutting challenges to innovation in land tenure documentation. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Augustinus, C.; Tempra, O. Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration in Violent Conflict Settings. Land 2021, 10, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020139

Augustinus C, Tempra O. Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration in Violent Conflict Settings. Land. 2021; 10(2):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020139

Chicago/Turabian StyleAugustinus, Clarissa, and Ombretta Tempra. 2021. "Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration in Violent Conflict Settings" Land 10, no. 2: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020139