Abstract

Valuation problems, such as valuation inaccuracies/variations, client influence, and the use of heuristics, are common problems in property valuation practice globally. These problems have generated debate in recent times under the rubric of “behavioural issues in valuation”. This paper examines valuation problems in developing countries, as well as the current efforts that are undertaken to address these problems, with a view of determining the best approach to explain and/or address them. This stems from the persistence of valuation problems despite efforts undertaken to improve the practice of valuation. The study involves a survey of registered and practising valuers in Kenya. Respondents were asked to indicate valuation problems in practice, adopted strategies, and recommendations to address the said problems. It emerged from the study that valuation problems not only result from valuer misconduct but also market-related problems/the valuation environment in developing countries. The study further found that efforts to address these problems are mainly focused on improving valuer conduct while neglecting market-related problems (problems related to the nature of the valuation environment in developing countries). Based on these findings, the study concludes that valuation problems in practice are better understood in the context of both categories, i.e., valuer conduct and market-related problems, and recommends a holistic approach to address these problems by categorising them appropriately.

1. Introduction

Valuation problems in practice, including valuation inaccuracies/variations, client influence, and the use of heuristics, negatively impact the valuation profession globally. Empirically, these issues have been researched under the rubric of ‘behavioural valuations’, with concerted efforts to improve valuation practice through increased valuation accuracy and reliability. Researchers in developed countries such as Bretten and Wyatt [1] Bogin and Shui [2], Diaz and Hansz [3], Dunse, Jones, and White [4], and Kucharska-Stasiak, Zrobek, and Cellmar [5], among others, have confirmed the existence of valuation problems such as valuation inaccuracies/variations, client influence, and the use of heuristics. The above studies have mainly attributed valuation problems to valuer misconduct, i.e., valuers’ behaviour, such as negligence, professional misconduct, incompetence, and unethical conduct of valuers, among other things. Studies in developing nations have followed suit by mainly explaining the existence of valuation problems in the context of valuer misconduct, see, for example [6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

Consequently, efforts/strategies to improve valuation practice mainly focus on improving the conduct of the valuer through professional development programmes [10,13], periodic reviews of valuation standards and guidance notes, and strict enforcement of standards and regulations [10,11,14,15,16,17]. Further, educators have been urged to incorporate behavioural issues in valuation into valuation education and introduce practical courses in the real estate curriculum to counter negative behavioural traits [13,18].

In Kenya, attempts to minimise the above valuation problems are underway. These interventions mainly focus on improving valuer conduct/incompetence. They include the development and rigorous enforcement of valuation standards and regulations, valuer training, and disciplinary measures against errant valuers [19,20,21]. Additionally, Gitari [16] recommended the adoption of a central data bank. Ongoing efforts to improve access to information include digitising land records and developing the land value index [22,23].

Despite the above interventions, valuation problems in Kenya and many other developing countries persist. It is important to note that, compared to developed countries, valuation problems in developing countries are more pronounced mainly because of the nature of the valuation environment in these countries, characterised by immature property markets, few buyers and sellers with limited information, limited transaction activity, and inadequate market infrastructure, among other things. In addition to limited information, there are numerous other causes of valuation problems in developing countries, including corruption, poor land information management systems, valuer misconduct, failure by the regulatory and professional body to properly regulate the profession, non-enforceability of zoning regulations, and inadequate valuer training, among other things. However, this study’s specific focus is on limited and unreliable information, corruption, poor land information management systems, and valuer misconduct, which have been prominent in the literature. Accordingly, the purpose of this paper is to establish why valuation problems in developing countries persist despite efforts to improve the practice of valuation. It is hypothesised that the most important factor contributing to the persistence of valuation problems in developing countries is limited and unreliable information.

Studies on behavioural valuation, such as those carried out by Adegoke et al. [14], Aderemi [15], Ashaolu and Olaniran [9], Ogunba and Oloyede [24], Nwuba et al. [11], Oshiobugie et al. [12], and Osmond [25], among others, have established the existence of valuation problems in developing countries, including valuation inaccuracies/variations, client influence, and the use of heuristics. Literature also indicates the existence of limited and unreliable information, poor land information management systems, corruption, and valuer misconduct, among other things, in developing countries, see, for example [23,26,27].

2. Problems of Valuation Practice

Previous valuation research has mainly been studied under the title ‘behavioural valuation’, which includes valuation inaccuracies/variations, client influence, and the use of heuristics. As will be discussed, these issues have mainly been understood in the context of valuer conduct, with little focus on market-related problems that are specific to developing countries, such as limited and unreliable information.

2.1. Valuation Inaccuracies/Variations

Internationally, the issue of valuation inaccuracies and variations between valuations has been the subject of academic and professional debate for decades [6,28]. Valuation accuracy is the ability of a valuation to correctly identify the target, i.e., the sale price or rent of the property, while valuation inaccuracy is the converse [29]. On the other hand, variations in valuations focus on the ability of two or more valuations to produce the same outcome on the same basis at the same time [26]. Therefore, it attempts to measure the difference(s) between two or more valuations. In most cases, valuation variations are usually used to measure valuation accuracies, where high variations represent inaccurate valuations while low variations represent accurate valuations.

Crosby [29] found that the courts in the UK have relaxed valuation accuracy by adopting the margin of error concept of between 10 percent and 20 percent, with any valuation outside the bracket attributed to negligence. Crosby suggested widening the permissible bracket to 35 percent, indicating a reduction in valuation accuracy in the UK. Similarly, Bretten and Wyatt [1] found that variations in commercial property valuations in the UK are inevitable. In support of Crosby [29], Bretten and Wyatt [1] found that the margin of error (a legal manifestation of valuation variance) is a fair and reasonable test for negligence. Bretten and Wyatt [1] further established that the leading cause of valuation variation is the valuer’s behavioural influences.

McGreal and Taltavull de La Paz [30] found a high level of accuracy in residential property valuations in Spain, with 94.26% of the valuations being within either plus or minus 15%. In essence, unlike Crosby [29] who suggested a margin of error of 35%, McGreal and Taltavull de La Paz [30] implied a margin of error of 15%. In the same vein, Bogin and Shui [2] found that property appraisals in the USA tend to be biased upwards and may overstate the true value of the underlying collateral. They indicated that appraisal bias is particularly pervasive in rural areas, where over 25% of rural properties are appraised at more than 5% above the contract price.

In a comparative study of local office markets in nine cities in the UK, Dunse, Jones, and White [4] established that valuations in the largest market, the City of London, are more variable despite having more information. They indicate that variability in the property market rather than information is the main source of valuation inaccuracy in the UK. Therefore, Dunse et al. [4] indicated that, although the UK is characterised by a lot of information, there exist other factors that contribute to valuation variations.

Awuah et al. [26] investigated the extent of valuation variations in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Their findings indicated that valuation variation is relatively high compared to international evidence. They established major causes of valuation variations in their order of importance, including insufficient property market data, lack of standardisation in applying valuation methods, the complexity of properties, and client influence.

Unlike most studies that have studied valuation accuracy from a valuer’s perspective, Aderemi [15] surveyed valuers’ clients (commercial banks) in Nigeria and established a high degree of valuation inaccuracies, supporting previous studies that primarily focused on valuers. Further, Aderemi [15] found that valuation inaccuracy in Nigeria is mainly attributed to the behavioural characteristics of the valuer, i.e., negligence and incompetence. Contrary to Awuah et al. [26], Aderemi [15] identified inaccurate data as a minor cause of valuation inaccuracy. However, it is essential to note that this is best explained by valuers who are the users of comparable data and not entirely by clients.

Just like Aderemi [15], Adegoke et al. [14] studied clients’ (commercial banks) perception of the reliability of mortgage valuations in Nigeria and established the existence of high levels of variations between the valuation of properties on default mortgage and foreclosed values. However, unlike Aderemi [15], who identified property market data as a minute cause of valuation inaccuracy, Adegoke et al. [14] acknowledged that insufficient market data and lack of a data bank in Nigeria contribute to valuation inaccuracy.

The above studies have mainly explained valuation inaccuracies/variations in the context of valuer conduct with little emphasis on the market-related problems, such as the limited and unreliable information, that characterise developing countries. The studies recommend professional bodies to promote high ethical standards, independence, and professionalism in valuation practice, a review of valuation standards and guidance notes, effective regulatory frameworks, and strict enforcement of standards and regulations. These recommendations mainly focus on improving valuer conduct without emphasising measures to improve problems related to the valuation environment in developing countries.

As discussed, valuation inaccuracy is an international valuation problem. It is predominant in developing nations compared to developed nations. Beale [28] and Kucharska-Stasiak [31] believe that, while developing countries represent immature property markets with incomplete and unreliable property information, developed countries exhibit a more structured and mature property market that is more active with greater market transparency. Factors influencing valuation inaccuracies/variations include client influence [32], inappropriate use of heuristics [33], and other valuation problems such as limited information, corruption, etc. [26,27].

2.2. Client Influence

Client influence refers to the manipulation of the valuation process by clients’ actions to have the valuation outcome to their advantage [11]. It compromises the valuer’s independence and obligation for objectivity and unbiased reporting, contributing to biased valuation outcomes [11,34]. Mooya [35] believed that valuers’ clients often have a direct interest in the magnitude of the valuation outcome, especially in cases where their compensation depends on reported valuations. Mooya [35] indicated that clients may not be interested in objective opinions of value but in figures that further their objectives. As will be discussed in this section, client influence is a common problem of valuation practice globally.

Kucharska-Stasiak et al. [5] found that client influence exists within the valuation profession in Poland. They established that client influence results from various elements of both the client’s and the property valuer’s business environment, including non-compliance with the code of professional conduct. Similarly, in a series of interviews with senior New Zealand registered valuers, Levy and Schuck [36] found that clients indeed influence valuers. They indicated that client influence can either be positive or negative. While positive influence is essential in providing crucial information, negative influence can lead to valuation inaccuracies. Additionally, Levy and Schuck [37] interviewed valuers’ clients (senior New Zealand property management executives) and established that clients with expertise and a high level of knowledge of the property market influence valuers through expert and information power. They indicated that the client’s control over the valuation process, including the common practice of permitting clients to review draft valuations before their formalisation, affords opportunities to exert influence.

In a behavioural experiment of real estate appraisers, Worzala, Lenk, and Kinnard [38] found that client influence exists in the USA. However, they established that appraisers were not influenced by either client size, value adjustment, or the interaction of these two factors. Consequently, Worzala et al. [38] concluded that appraisers do not succumb despite the high level of client influence in the USA. Unlike Worzala et al. [38], Achu et al. [6] found that, although client size and the value adjustment demanded did not affect valuers’ judgment in Malaysia, valuers succumbed to client influence. Their finding indicated that other factors, aside from client size and value adjustment, influence valuers to succumb to client influence. They established that client characteristics and valuer characteristics are the most important factors affecting client influence on valuation. Contrary to the findings of Worzala et al. [38], Diaz and Hansz [3] found that residential appraisers succumb to client influence, resulting in biased appraisals.

Wolverton and Gallimore [39] found that client feedback in the USA negatively influences the valuation profession. On the contrary, Gallimore and Wolverton [40] established that client feedback in the USA is rare, indicating fewer debilitating effects. The Home Valuation Code of Conduct (HVCC) and its successor, the “appraisal independence standards” in the Dodd–Frank Act, were passed in 2009 and 2010, respectively [41]. This legislation aims to ensure the independence of residential appraisers from lenders, hence protecting borrowers by avoiding biased value judgments [41]. The Dodd–Frank Act disconnects lenders and residential appraisers by introducing appraisal management companies (AMCs) as intermediaries, eliminating client influence [41]. Freybote, Ziobrowski, and Gallimore [41] found that the introduction of legislation eliminated transaction price feedback, indicating its effectiveness in reducing client influence in the USA. While this study indicates the effectiveness of legislation in controlling client influence, it is essential to note that, unlike developed countries, most developing countries are characterised by weak institutions that may not curb client influence.

In a comparative study on client influence in valuation in Taiwan and Singapore, Chen and Yu [42] found that, although client influence in valuation exists in both countries, the degree and extent of the problem are different. They concluded that different market structures, development backgrounds, and modes of doing business impact the factors causing client influence. They further found that the main indication for client influence is the lack of transparent market information in Taiwan, where lack of market transparency was identified as a major problem. They argued that clients tend to take advantage of the subjectivity in valuations without clear market information and often demand an adjustment of up to 10%. As discussed, the extent of client influence varies from country to country, and it is more pronounced in environments with limited information, such as those portrayed in developing countries.

In Africa, Amidu and Aluko [7] examined client influence in residential property valuations in Nigeria and found that client influence negatively affects the valuation industry. Similarly, Ashaolu and Olaniran [9] found that client influence is a major problem in Nigeria, with over 80% of the respondents confirming that they have succumbed to client influence. Amidu, Aluko, and Hansz [43] found that client influence exists in Nigeria, and valuers succumb to this influence. Likewise, Mwasumbi [17] and Oshiobugie et al. [12] found that client influence is pronounced in valuation for mortgage purposes in Tanzania and Nigeria, respectively.

Just like the findings of Achu et al. [6], Amidu and Aluko [7] found that, while estate surveyors and valuers succumb to client influence, such decisions are not influenced by the client size and the amount of adjustment required. Their findings indicate that, in addition to client size and amount of adjustment, other factors affect client influence in Nigeria. Amidu and Aluko [8] established the three most significant influencing factors of clients to include the integrity of the valuer or valuation firm, importance of the valuation outcome to the client, and client size. The third-ranked factor, i.e., client size, contradicts the findings of Achu et al. [6], Aluko and Amidu [7] and Worzala et al. [37] who found that respondents were not influenced by either the client’s size, the value adjustment requested, or the interaction of these two factors. Contrary to the findings of Amidu and Aluko [7], Amidu and Aluko [8], Amidu et al. [43], and Oshiobugie et al. [12] found that, although clients attempt to influence valuation opinions, valuers do not succumb to this influence. This indicates that client influence does not have a significant effect on the valuation profession in Nigeria.

The above studies mainly explain client influence in the context of valuer conduct with little focus on market-related problems such as limited information. They recommend the need for regulatory and professional bodies to continuously ensure strict enforcement of the code of conduct and ethics and improve their efforts in educating clients and other stakeholders on the need for impartial property valuations. Further, they recommend incorporating client influence in valuers’ education to prepare them to react appropriately.

From the literature review, client influence is a major problem of the valuation practice globally. However, it is likely to be more pronounced in developing countries compared to developed nations. This is because developing countries are characterised by immature property markets with poor institutions and limited information. In contrast, developed countries are characterised by mature property markets with superior institutions (e.g., the Home Valuation Code of Conduct (HVCC) and the Dodd–Frank Act that have reduced client influence in the USA). Further, developed nations exhibit better access to information due to the availability of data banks [28,31,41].

2.3. The Use of Heuristics

Heuristics could be defined as rules or patterns (rules of thumb) that help to reduce the complexity of decision making [44]. They explain how people make decisions, arrive at judgments, and solve problems when faced with complex situations or incomplete information [45]. Therefore, heuristics play a key role in decision making, especially in environments with incomplete information. Nonetheless, the use of heuristics does not always guarantee desired effects, mainly because of its generality and lack of precision [46].

The most researched heuristic is the anchoring and adjustment heuristic. Other heuristics include availability, representative, and positivity heuristics [25,44,47]. Anchoring and adjustment heuristics refer to the practice where valuers rely on an initial reference point as a starting point while adjusting it as further evidence is considered until a final solution is reached [25,48]. The anchoring effect appears when different initial values imply different estimated values contributing to variations in property values [46]. Inappropriate reference points, such as clients’ value opinions and inadequate adjustments, can be sources of bias [48].

Chinloy, Cho, and Megbolugbe [49] confirmed the existence of anchoring and adjustment heuristics, where appraisers anchored on the property’s purchase price in the USA. Similarly, Hansz [50] found that American appraisers anchored towards the pending mortgage reference point, contributing to valuation variations. In a survey of leading fund managers and commercial appraisers in the UK, McAllister et al. [51] found that appraisers anchor on previous appraisals in assessing commercial property values, contributing to valuation variations. McAllister et al. [51] established lack of information and the institutional context of appraisals as key factors contributing to the use of anchoring and adjustment heuristics in commercial appraisals in the UK.

Diaz [52] found that neither apprentice nor expert appraisers operating in familiar geographical settings were influenced by previous value judgments of anonymous experts in the USA. On the contrary, Diaz and Hansz [53] established that both apprentice and expert appraisers operating in unfamiliar geographical areas were influenced by the valuation opinion of an anonymous expert. Similarly, Diaz and Hansz [54] found that the value judgments of expert commercial appraisers operating in unfamiliar geographical settings were influenced by various reference points such as the uncompleted contract price of a comparable and subject property and the value opinions of other experts. While the subjects of Diaz [52] were familiar with the subject area, the subjects of Diaz and Hansz [53] and Diaz and Hansz [54] were not familiar with the subject area. Therefore, these studies suggest that unfamiliarity with the market (characterised by limited information) has a role in evoking an anchoring and adjustment heuristic. Seemingly, an anchoring and adjustment heuristic helps valuers to assess market value in situations with limited information.

In a survey of valuers in Poland, Zrobek et al. [46] found evidence of anchoring and adjustment heuristics, where valuers were influenced by the negotiated transaction price and the property’s previous value. Zrobek et al. [46] further established that anchoring and adjustment heuristics have little impact in a market with a lot of information on property transactions. Just like the findings of Diaz and Hansz [53] and Diaz and Hansz [54], Zrobek et al. [46] established that anchoring and adjustment heuristics are not widespread in familiar environments but are much greater in unfamiliar environments. This finding confirms that geographical unfamiliarity, characterised by limited information, triggers the use of an anchoring heuristic, while geographical familiarity, characterised by greater market transparency and availability of information, reduces the use of anchoring heuristics.

In a survey of estate surveyors and valuers in Nigeria, Osmond [25] and Iroham, Ogunba, and Oloyede [24] established the existence of anchoring and adjustment heuristics. Despite the prominence given to this type of heuristic, see, for example [50,51,52,53,54], Osmond [25] and Iroham et al. [24] found that it is not the most common type of heuristic but the second, after the availability heuristic. Further, Iroham et al. [24] established that valuations conducted through an anchoring and adjustment heuristic are somewhat accurate relative to the sale prices. This study suggests that anchoring and adjustment heuristics do not necessarily contribute to inaccurate valuations in Nigeria.

The literature indicates that the use of heuristics is common within the valuation profession globally. While appropriate use of heuristics helps valuers assess market value in situations with limited information, inappropriate use contributes to inaccuracies in property valuation. The use of heuristics is rampant in unfamiliar geographical areas with limited information. Since developing countries are characterised by limited information, the use of heuristics is likely to be more pronounced in these areas than in developed countries.

2.4. Other Valuation Problems Specific to Developing Countries

Other than the above-mentioned problems of valuation practice, there are other types of valuation problems related to the nature of the property market in developing countries. Awuah et al. [26] examined property valuation practice in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and established that paucity of property market data is a major cause of valuation variations. Awuah et al. [26] attributed the paucity of property market data to the lack of a centralised data bank. Sources of property market data in SSA include parties to property transactions, informal property agents, lawyers, etc., who hardly record full transaction details and property characteristics, hence poor and unreliable property market data contributing to valuation inaccuracies [26]. In contrast, developed nations adopt sophisticated property market data sources such as the UK’s IPD property indexes [34,55] and Multiple Listing Service (MLS) [3,56]; and the House Price Index (HPI) [57] in the USA.

To improve the practice of valuation in SSA, Awuah et al. [26] developed a property market data collection template and provided effective property market data collection guidelines. Further, the study recommends the need for professional bodies to create a property market data bank, provide enhanced regulations, and undertake regular training through continuous professional development (CPD) programmes to enhance valuers’ skills to collect good quality property market data and produce high standard valuations. While Awuah et al. [26] established valuation problems in SSA, they did not categorise these problems in the context of market-related problems and valuer conduct.

Similarly, in a survey of key informants in Ghana, Rwanda, Namibia, Nigeria, Malawi, Tanzania, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Kenya, Mutema [27] found that, unlike the UK and USA, many African nations, except South Africa, do not have property price indices. The lack of property indices in developing countries contributes to the lack of transparent property market price information that aggravates valuation inaccuracies/variations [27]. Mutema [27] confirmed that the lack of property information accompanied by valuation variations is likely to be more pronounced in developing countries than in developed nations. Mutema [27] proposed the need for alternative and more flexible valuation methods that consider the prevailing property market characteristics. Mutema [27] recognised that attempts to tamper with tried and tested traditional valuation methods are likely to face stiff resistance from the valuation profession that trusts in the mainstream (traditional) valuation methods. While Mutema [27] recommended the need for flexible valuation methods that consider property market characteristics in developing countries, he failed to identify the proposed methods. Further, Mutema [27] did not recommend specific measures to improve access to property market data in developing countries.

Further, Awuah et al. [26] and Mutema [27] established that the lack of national regulation of the valuation practice and standardisation in applying valuation methods are major challenges that contribute to high levels of valuation variations in Ghana. Awuah et al. [26] found that this resulted in the proliferation of informal practitioners who often lack the requisite training and experience to practice valuation. Similarly, in Nigeria, Mutema [27] found that the lack of national valuation standards contributes to valuation inaccuracies. Just like Ghana and Nigeria, most developing countries experience lack of standardisation, poor regulations, and a failure to enforce available standards and regulations. These problems are likely to be rampant in developing countries compared to developed nations.

Additionally, Mutema [27] and Awuah et al. [26] found that unstable prices, resulting from high inflation and interest rates, an underdeveloped property market, unqualified valuers, and land tenure issues, negatively impact the valuation profession in Africa. In Uganda, Mutema [27] established major challenges affecting the valuation profession: high levels of speculation, limited public knowledge of valuation services, inadequate research on pertinent valuation issues, lack of professional integrity, and gaps in the real estate curricular. Challenges that hamper the evolution of the valuation profession in Nigeria include high inflation and an obsolete training curriculum [3]. Mutema [27] further established the lack of a proper professional body focusing on valuation as a major challenge in Malawi. Furthermore, in Kenya, Mutema [27] established corruption and high inflation rates as major challenges to the valuation profession in the country. Although the studies identified valuation problems in developing countries, they did not attempt to categorise them.

Finally, in a survey of the Ministry of Lands (MOL) staff in Kenya, Mwangi [23] found poor service delivery in terms of speed of service delivery and quality of services. Mwangi [23] attributed poor service delivery at MOL to poor land information management systems incorporating the manual system of record keeping. Mwangi [23] suggested the need to computerise the ministry’s land records and implement an integrated land information management system to ensure efficient and effective delivery of services. Mwangi [23] focused on developing an integrated land information management system but did not discuss the impact of poor land information management on the valuation profession.

3. Methods

The study involved a quantitative methodological approach, aided by descriptive and inferential statistics. Empirical data were obtained from a survey of registered valuers licensed to practice valuation in Kenya in the year 2020. There are currently 427 registered and practising valuers in Kenya [58]. The researcher collected information from the entire population of registered and practising valuers, i.e., 427 respondents; hence, sampling was not necessary. The population was key in providing insights on valuation problems in practice. Respondents were asked to indicate the effect of limited and unreliable information, poor land information management systems, corruption, and valuer misconduct on valuation inaccuracies/variations in Kenya, a typical representation of many other developing countries. Further, strategies adopted by the respondents to respond to the aforementioned problems of the valuation profession were established.

Prior to the survey, a pre-test or pilot questionnaire was sent to a small sample population comprising ten registered and practising valuers via the Survey Monkey platform. The researcher targeted registered and practising valuers within her network to respond to the pre-test questionnaire. This strategy was used to validate the questions constructed in the final questionnaire, eliminate any ambiguous or irrelevant questions, and incorporate any key issues that may have been left out. Final questionnaires were emailed to the entire population of registered and practising valuers in Kenya via the Survey Monkey platform. The researcher made follow-ups by sending email prompts, making telephone calls, and sending messages to improve the response rate. Respondents contact details (email addresses and telephone numbers) were extracted from the Institution of Surveyors of Kenya (ISK) database. The questions were drafted with predetermined response choices from which the respondents were to tick as appropriate. In addition, a Likert scale was used in determining the ratings of the respondents on predetermined statements. The researcher adopted the Likert scale due to its effectiveness and simplicity in construction [59].

The study adopted a quantitative data analysis technique by use of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27. Data obtained from the survey were coded into the SPSS software and analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistical analysis involves analysing numeric data to obtain summary indicators that can efficiently describe a group and the relationships among the variables within that group [60]. It includes means, modes, standard deviations, and ranges [61]. This study adopted means and used frequency tables in descriptive analysis. On the other hand, inferential statistics involve statistical procedures that deal with inferences from samples to populations [60]. In analysing inferential data, the study adopted the Friedman ANOVA non-parametric test followed by pairwise comparisons.

4. Results

4.1. Profile of the Respondents and the Study Response Rate

As discussed previously, questionnaires were issued to the entire population of registered and practising valuers, i.e., 427 valuers. A total of 166 questionnaires were filled and returned, constituting a response rate of 39%. Out of the 166 questionnaires, 34 were rejected and excluded from further analysis because they were either incomplete or did not meet the required criterion. Therefore, only 132 questionnaires constituting 31% of the total population were deemed valid for analysis. The response rate of 31% was considered sufficiently large for the drawing of conclusions and the making of valid inferences about the population. Table 1 below displays a summary of the survey response rate.

Table 1.

Survey response rate.

As indicated previously, respondents were registered and practising valuers in Kenya. Of the 132 respondents, 75 (56.8%) possessed a bachelor’s degree as their highest level of education and 51 (38.6%) had a master’s degree, while 6 (4.5%) had a doctorate. Table 2 below presents this information.

Table 2.

Highest level of education.

The results show that registered and practising valuers in Kenya are educated with at least a bachelor’s degree. The findings are in tandem with the ISK syllabus and the Valuers Act 1984 [21] that stipulate the conditions for valuer registration to include a bachelor’s degree in Land Economics, Real Estate, or its equivalent [21,62].

As far as the designation of the respondents is concerned, the majority of the respondents, i.e., 71 respondents (53.8%), were directors; 38 (28.8%) were senior valuers; and 21 (15.9%) were valuers, while only 2 (1.5%) were assistant valuers, as shown in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Designation of the valuer.

The results indicate that majority of the respondents act as directors in their respective valuation firms. This finding explains the country’s valuation environment where most registered and practising valuers focus on starting their valuation firms instead of looking for formal employment in established firms or government bodies, hence the existence of many small valuation firms in the country.

Further, results show that respondents are experienced in valuation as 73 (55.3%) had more than ten years’ experience in valuation work, 51 (38.6%) had between six and ten years’ experience, and only 8 (6.1%) respondents had between two and six years of experience. This finding indicates that respondents were experienced enough to understand valuation problems in practice and were best suited to respond to the survey questionnaire. Table 4 displays a summary of these results.

Table 4.

Valuer experience.

Generally, the results on valuer education, designation, and experience portray respondents who are well educated and experienced in valuation matters, making them ideal for this study.

As far as the location of the respondents is concerned, out of the 132 respondents, 104 (79%) worked in Nairobi province; 8 (6%) were based in Rift Valley province; 7 (5%) in the Coast province; 4 (3%) in Central province; 3 (2%) in Eastern and Nyanza provinces; 2 (2%) in Western province; and 1 (1%) in North Eastern province. Table 5 below presents the geographical location of the responding valuers in the country.

Table 5.

Location of the respondents.

The results indicate that most valuers were based in Nairobi; this was expected since Nairobi, the capital city, harbours most valuation firms in Kenya. It is, therefore, unsurprising that respondents in other provinces were generally low. However, the geographical location of the respondents is representative of the country. Thus, this study presents a good geographical representation of Kenya’s valuation practice.

4.2. Limited and Unreliable Information

Respondents were asked to indicate on a Likert scale of 1 to 5, ranging from very weak effect to very strong effect, whether limited and unreliable information negatively affects the valuation profession, contributing to valuation inaccuracies/variations in the country. Out of 132 respondents, 54 (40.9%) confirmed that this problem has a very strong negative effect on the valuation profession; 43 (32.6%) indicated a strong negative effect, while 22 (16.7%) indicated a moderate effect. Generally, most respondents (90.2%) agreed that limited and unreliable information contributes to valuation inaccuracies in the country. Only nine (6.8%) indicated a weak effect, with the remaining four (3.0%) indicating a very weak effect. Table 6 below presents a summary of these results.

Table 6.

Limited and unreliable information.

Findings present limited and unreliable information as a major problem contributing to valuation inaccuracies/variations in Kenya. The study further established how registered and practising valuers respond to this problem. First, findings indicate that in the absence of information, registered and practising valuers adopt alternative approaches to the market approach, such as investment or cost approach. This strategy attracted the highest mean of 4.73. The second most adopted strategy, with a mean of 4.47, is maintaining an in-house database of comparable properties. Third, with a mean of 4.25, respondents agreed that they widely seek other real estate professionals’ opinions on the subject property’s market value.

Next, with a mean of 3.91, respondents indicated that, where the subject property’s previous valuation or sale price is available, they rely on it while making adjustments to capture the time difference. Thus, the results confirm that anchoring heuristics are pronounced in environments with limited and unreliable information to solve information problems. This finding corresponds with the findings of Diaz [52], Diaz and Hansz [53], Diaz and Hansz [54], and Zrobek et al. [46], who established that anchoring heuristics are widespread in areas with limited information.

Additionally, respondents agreed, with a mean of 3.84, to seek comparable information from similar markets outside the subject area to improve valuation inaccuracies. The least adopted strategy in responding to limited and unreliable information was reliance on client information on indicative property values with a mean of 2.93. However, it is possible that respondents would not openly admit to having succumbed to client influence, as it amounts to professional misconduct. Nonetheless, this strategy is above the 50% mark (2.5), indicating that, although client influence is not a common strategy, valuers succumb to this problem in the absence of information. A summary of these strategies is provided in Table 7 below.

Table 7.

Valuers’ response to limited and unreliable information.

4.3. Corruption

To investigate the effect of corruption on the valuation industry, registered and practising valuers were asked to indicate whether corrupt officials at the lands office and bank credit managers negatively influence valuers in stamp duty and mortgage valuations, respectively, contributing to valuation inaccuracies. Findings indicate that 42 (31.8%) of the respondents believed that corruption has a very strong negative effect on the valuation profession in the country; 33 (25%) indicated a strong negative effect, while 27 (20.5%) indicated a moderate effect. In general, 77.3% of the respondents agreed that corruption contributes to valuation inaccuracies in Kenya. Only 21 (15.9%) indicated a weak negative effect, with 9 (6.8%) indicating a very weak negative effect. Table 8 below presents a summary of these results.

Table 8.

Effect of corruption on the valuation profession.

Findings indicate that registered and practising valuers do not succumb to corruption. The two variables, “bribing to get the job” and “renegotiating for a lower bribe”, were ranked with a mean of 1.49 and 1.90, respectively. Table 9 presents a summary of these results.

Table 9.

Valuers’ response to corruption.

Analysis of the findings indicates that corruption is a major problem that negatively affects stamp duty and mortgage valuations. However, while corruption exists within Kenya’s valuation profession, valuers rarely succumb to this problem. Although this could be the correct position, there is a possibility that respondents could not admit having succumbed to corruption, especially because this vice has drawn public attention with relentless efforts to eliminate it. Valuers also respond to corruption by anonymously reporting the culprits to ISK and VRB, diversification into other areas like property management, and declining instructions linked to corruption.

4.4. Poor Land Information Management Systems

The study also assessed the effect of poor land information management systems on the valuation industry. Respondents were asked to indicate whether this problem negatively affects the valuation profession, contributing to valuation inaccuracies in Kenya. According to the findings, 36 (27.3%) believed that this problem has a very strong negative effect on the valuation profession, 36 (27.3%) indicated a strong negative effect, while 33 (25%) indicated a moderate effect. Overall, 79.6% of the respondents agreed that poor land information management systems contribute to valuation inaccuracies in Kenya. However, 21 (15.9%) indicated that this problem has a weak negative effect, while 6 (4.5%) indicated a very weak negative effect. These results are summarised in Table 10 below.

Table 10.

Poor land information management systems.

In response to poor land information management systems, respondents mainly explain the situation to their clients while asking them to bear with the delay. This strategy attracted the highest mean of 4.11. Another strategy, mainly adopted by responding valuers, with a mean of 3.37, involves situations where valuers use their networks and pay an extra amount (facilitation fee) to fast-track the process. The payment of facilitation fees indicates that valuers in Kenya succumb to corruption. This contradicts our previous finding that valuers do not succumb to corruption. As discussed previously, while valuers may have succumbed to corruption, they may not directly admit to having committed this vice.

The fact that valuers exempt themselves from misinformation by indicating that they fully rely on the information provided without undertaking any further verification attracted a mean of 2.62, indicating that this may not be a popular strategy that valuers adopt in responding to poor land information management. Table 11 below presents a summary of the results.

Table 11.

Valuer’s response to poor land information management systems.

Overall, the survey findings present poor land information management systems as a major problem that negatively affects the valuation profession, contributing to valuation inaccuracies in the country. Valuers respond to this problem by explaining the situation to their clients and/or bribing land officers to fast-track the process.

4.5. Valuer Misconduct

Further, the study investigated whether valuer misconduct, i.e., professional misconduct, negligence, incompetence, and unethical conduct of valuers, including vices such as the use of unqualified staff in valuation or undercutting, among other things, negatively affects the valuation profession, contributing to valuation inaccuracies in Kenya. Respondents were asked to rate this problem on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The results are as follows: 32 (24.2%) indicated that valuer misconduct has a very strong negative effect on the valuation profession; and 33 (25%) showed a strong negative effect, while 43 (32.6%) indicated a moderate effect. Thus, 81.8% of the respondents agreed that valuer misconduct negatively affects the valuation profession in Kenya. On the other hand, only 19 (14.4%) of the respondents indicated that valuer misconduct has a weak negative effect, while 5 (3.8%) indicated a very weak negative effect. A summary of these results is provided in Table 12 below.

Table 12.

Valuer misconduct.

With a mean of 4.5, respondents strongly agreed that, where affected, they respond to valuer misconduct by attempting to improve their training and that of their employees through continuous professional development, on-the-job training, and off-the-job training. Thus, the results indicate that constant training of valuers can help improve the valuation profession by minimising valuer misconduct. This finding supports the findings of Awuah et al. [26] and Babawale and Omirin [10], who recommended the need for professional and regulatory bodies to enhance valuer knowledge and skills through regular training, i.e., CPD programmes.

In cases where other valuers are involved in professional misconduct, respondents agreed to respond to this problem by advising the affected party to adhere to professional standards and regulations with a mean of 4.62; advising the affected party to improve their training and that of their employees through continuous professional development, on-the-job training, and off-the-job training with a mean of 4.51; and reporting the affected party to the relevant professional bodies with a mean of 3.26. Table 13 below presents a summary of these results.

Table 13.

Valuers’ response to valuer misconduct.

It is evidenced that, while valuers report their colleagues acting in professional misconduct to either the ISK or VRB, this may not be a common strategy. This perhaps indicates that respondents may not have faith in the VRB and ISK’s disciplinary mechanisms. Respondents also indicated that they internally discipline errant members within the organisation.

4.6. Explaining Valuation Problems in Practice

Valuation problems, such as valuation inaccuracies/variations, client influence, and the use of heuristics, have been established to exist within the valuation profession in Kenya and many other developing countries. In explaining the aforementioned problems of valuation practice, the study relied on descriptive and inferential statistics.

Using descriptive statistics, the mean values of the different causes of valuation problems were calculated. Limited and unreliable information scored the highest mean of 4.02, indicating that majority of the responding valuers agreed that this problem has the greatest negative effect on the valuation profession, contributing to valuation inaccuracies/variations. In the second position was corrupt officials at the lands office and bank credit managers with a mean of 3.59, indicating that corruption is yet another core problem that contributes to valuation inaccuracies. Next, is the problem of poor land information management systems with a mean of 3.57, followed by valuer misconduct with a mean of 3.52. Table 14 below presents a summary of these results.

Table 14.

Causes of valuation problems in Kenya.

Generally, the study found that the aforementioned problems contribute to valuation inaccuracies/variations in Kenya. This is typical of many other developing countries. Limited and unreliable information was perceived to be the most important problem with valuer misconduct being a minor problem of the valuation profession.

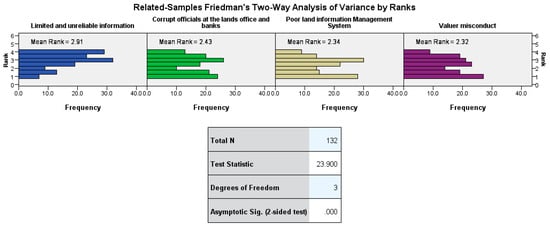

Analysis of the above causal problems using descriptive statistics alone may not conclusively explain why valuation problems persist in practice. To comprehensively explain the core problems contributing to valuation inaccuracies/variations, the study relied on inferential statistics, i.e., the Friedman ANOVA non-parametric test followed by pairwise comparisons. The test was used to rank and explain the causal problems of valuation practice, i.e., limited and unreliable information, corruption, poor land information management systems, and valuer misconduct. The Friedman test explains valuation problems by identifying the main problems that negatively affect the valuation profession, contributing to valuation inaccuracies/variations.

The Friedman ANOVA is the alternative to one-way ANOVA with repeated measures when the latter’s assumptions have been violated [63]. This test is used for testing differences between conditions when there are more than two conditions and the same participants have been used in all conditions [63]. The method calculates the mean ranks for each condition before calculating the test statistic (F) [63]. The present study violates the assumptions for a parametric test, i.e., scale data, normal distribution, and equal variances [64]. In collecting data, this study relied on the use of Likert scales that assume ordinal data. This does not meet the parametric test requirement of scale data, hence the suitability of the Friedman ANOVA non-parametric test. The mean ranks for the different valuation problems in practice were provided, with the most important problem having the highest mean rank while the least important problem had the lowest mean rank.

Findings indicate that limited and unreliable information is the main problem of the valuation profession with the highest mean rank of 2.91. Corrupt officials at the lands office and bank credit managers ranked second with a mean rank of 2.43, presenting corruption as the second major problem affecting the valuation industry in Kenya. Poor land information management systems, with a mean rank of 2.34, ranked third, while valuer misconduct, with a mean rank of 2.32, ranked as the least significant problem contributing to valuation inaccuracies in Kenya. Figure 1 below presents a summary of these results.

Figure 1.

The Friedman ANOVA non-parametric test.

The Friedman test statistic (F test) is presented at the bottom of Figure 1 above. The results indicate a significance level of 0.000, which is lower than a p-value of 0.01. This shows a significant difference in the various problems that negatively affect the valuation profession in the country. In assessing the statistical significance of the results, we adopted the criterion in Table 15 below.

Table 15.

P-values.

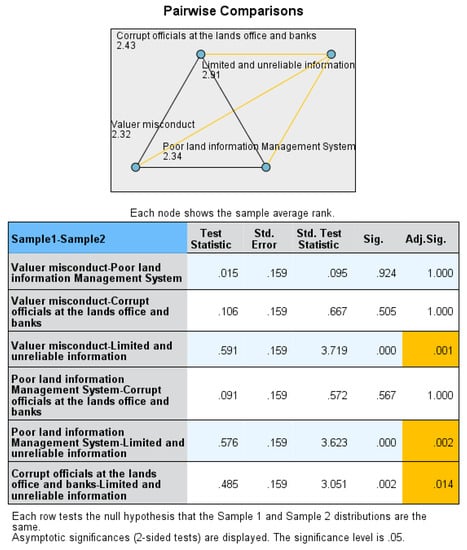

Post hoc tests, i.e., pairwise comparisons, were undertaken to establish the relationship between the various problems and their impact on the valuation industry in Kenya. The results of the pairwise comparisons are presented in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Pairwise comparisons.

The results in Figure 2 on pairwise comparisons indicate that limited and unreliable information with the highest mean rank of 2.91 is significantly different from all the three problems of valuation practice, i.e., corruption, poor land information management systems, and valuer misconduct. The significant difference between the above valuation problems with limited and unreliable information, which ranked as the main problem of the valuation profession, indicates that, unlike limited and unreliable information, these problems may not have a major impact on the valuation industry in the country. This presents limited and unreliable information as the core problem contributing to valuation inaccuracies/variations in Kenya.

On the other hand, valuer misconduct, which ranked lowest with a mean rank of 2.32, is significantly different from limited and unreliable information, as discussed above. The significant difference between this problem and the lowest-ranked problem, i.e., valuer misconduct, indicates that, unlike the latter, limited and unreliable information has a significant negative effect, contributing to valuation inaccuracies in the country. However, valuer misconduct did not significantly differ from corruption and poor land information management systems, indicating that these problems may not have a major impact on the valuation profession in Kenya.

In summary, evidence indicates that limited and unreliable information, an attribute of the valuation environment in Kenya and many other developing countries, is the main problem of the valuation industry. This problem negatively affects the valuation profession, contributing to valuation inaccuracies/variations. As discussed previously, this finding supports the findings of Awuah et al. [26], who identified paucity of property market data as a major problem affecting the valuation profession in sub-Saharan Africa. Further, our findings reinforce the findings of Mutema [27], who established lack of property market data as a major problem of the valuation profession in Africa. While our findings identify valuer misconduct as a problem of the valuation profession, this problem is not a core problem that impacts the valuation industry in Kenya. This finding contradicts the findings of most studies on behavioural issues in valuation that have mainly attributed the existence of valuation problems in developing countries, i.e., valuation inaccuracies/variations, client influence, and the use of heuristics, to valuer misconduct, see, for example [6,9,11,15,43], etc.

5. Discussion

Valuation problems such as valuation inaccuracies/variations, client influence, and the use of heuristics are more pronounced in developing countries compared to their counterparts in the developed countries. The study found that valuation inaccuracies/variations persist in developing countries mainly because of the nature of the valuation environment in these nations, characterised by limited and unreliable information. Further, evidence indicates that valuers respond to limited and unreliable information by adjusting previous valuations or sale prices and relying on client’s information. This explains why the use of heuristics and client influence persists in developing countries.

In essence, registered and practising valuers in Kenya adopt the use of heuristics to solve information problems and improve valuation accuracy. Therefore, while the use of heuristics exists within the valuation profession in Kenya, it is perceived as a solution to information problems and not a source of valuation inaccuracy. Additionally, the valuation environment in developing countries, characterised by limited information, exacerbates client influence.

Accordingly, the root causes of valuation problems in developing countries are market-related problems represented by limited information. Using the Friedman ANOVA non-parametric test, the study ranked the causal mechanisms to valuation problems in Kenya in their order of importance as follows: limited and unreliable information, corruption, poor land information management systems, and valuer misconduct. This finding contradicts previous empirical studies under the rubric of “behavioural valuations” that have mainly attributed valuation problems in practice to valuer misconduct with the neglect of problems related to the valuation environment. Consequently, efforts to improve the practice of property valuation are mainly skewed towards improving the conduct of the valuer, such as establishment and review of local valuation standards and regulations, as well as strict enforcement of these standards and regulations and valuer education on the need for independent valuations, among other things.

Fundamentally, valuation problems are less pronounced in developed countries, mainly because of the mature property markets with greater market transparency and a lot of information. On the other hand, developing countries represent immature property markets with incomplete and unreliable property information. Despite this, previous empirical studies in developing countries replicate those of developed nations. This perhaps explains why efforts to address valuation problems in practice mainly focus on improving valuer conduct with little emphasis on market-related problems, the core problem of the valuation profession in developing countries.

Valuation problems can be categorised in the context of market-related problems (problems related to the valuation environment) and valuer misconduct. This categorisation provides new insights in addressing valuation problems in practice. These insights involve the need to refocus valuation research and efforts to improve property valuation practice in developing countries to not only valuer misconduct but also problems related to the valuation environment in developing countries. Some of the recommended measures to deal with the limited and unreliable information that characterises the valuation environment in developing countries include improving access to property information by establishing a centralised database of comparable information and adopting countrywide digitisation of land records.

Having relied on the entire population of registered and practising valuers, there is a possibility that the response rate may not be fully representative of the population. However, given the large response rate, the researchers have no doubt that it is sufficient to make valid conclusions about the population. Further, as variously indicated in this paper, there is likely bias where respondents may not openly admit to having engaged in professional misconduct but may find it easier to attribute valuation problems in practice to the valuation environment. To improve the validity of the results, the study attempted to address bias by carefully formulating questions that refer to third parties and not the respondents where necessary. The study was also limited to the four main problems of valuation practice identified in the literature, i.e., limited and unreliable information, corruption, poor land information management systems, and valuer misconduct. It did not fully cover other causes of valuation problems in developing countries, such as poor standards and regulations and inadequate valuer education and training, among other things. These are possible areas of further studies.

Overall, this paper concludes that the core reason for the existence of valuation problems, such as valuation inaccuracies/variations, client influence, and the use of heuristics, in Kenya and many other developing countries is limited and unreliable information and not valuer misconduct that has gained prominence in valuation research under the title “behavioural issues in valuation”. However, this does not rule out other causes of valuation problems in practice, such as corruption, poor land information management systems, and valuer misconduct, that are equally important and should be addressed to comprehensively deal with valuation problems in practice.

Author Contributions

The article was prepared by I.C. under the supervision and guidance of M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the University of Cape Town Built Environment Ethics in Research Committee (14 June 2019) and the National Commission for Science, Technology & Innovation (NACOSTI) (NACOSTI/P/20/3784, 8 March 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The survey data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bretten, J.; Wyatt, P. Variance in commercial property valuations for lending purposes: An empirical study. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2001, 19, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogin, A.N.; Shui, J. Appraisal Accuracy and Automated Valuation Models in Rural Areas. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2019, 60, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diaz, J., III; Hansz, A. A taxonomic field investigation into induced bias in residential real estate appraisals. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2010, 14, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunse, N.; Jones, C.; White, M. Valuation accuracy and spatial variations in the efficiency of the property market. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. 2010, 3, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska-Stasiak, E.; Źrobek, S.; Cellmer, R. Forms and Effectiveness of the Client’s Influence on the Market Value of the Property—Case Study. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2018, 26, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Achu, K.; Chin, L.W.; Burhan, B.; Nordin, M.F. Factors affecting client influence on property valuation in Malaysia: Do client size and size of value adjustment matter? J. Teknol. (Sci. Eng.) 2015, 75, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amidu, A.R.; Aluko, B.T. Client influence in residential property valuations: An empirical study. Prop. Manag. 2007, 25, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidu, A.R.; Aluko, B.T. Client influence on valuation: Perceptual analysis of the driving factors. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2007, 11, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaolu, T.A.; Olaniran, M.A. Professionalism or clienteism: An X-ray of valuation practice in Southwestern Nigeria. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 8, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babawale, G.K.; Omirin, M. An Assessment of the relative impact of the factors influencing inaccuracy in valuation. Int. J. Hous. Markets Anal. 2012, 5, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwuba, C.C.; Egwuatu, U.S.; Salawu, B.M. Client influence on valuation: Valuers’ motives to succumb. J. Prop. Res. 2015, 32, 147–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiobugie, S.R.; Chukwudi, O.J.; Ifeanyi, E.F. An examination of client influence on residential property valuation in Benin Metropolis, Nigeria. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Dev. 2017, 4, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Iroham, C.O.; Ayedun, C.A.; Oloyede, S.A. A preview of non-client influence in property valuation in Nigeria. Bus. Manag. Dyn. 2012, 1, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Adegoke, O.J.; Olaleye, A.; Oloyede, S.A. A study of valuation client’s perception on mortgage valuation reliability. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 7, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderemi, O.S. Clients’ perception on the accuracy of valuation reports in Ibadan Metropolis. J. Educ. Policy Entrep. Res. 2015, 2, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gitari, B.M. Valuation of Up Market Residential Properties in Nairobi, Kenya. Master’s Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mwasumbi, A.N. External influence on valuation: Looking for evidence from Tanzania. J. Land Adm. East. Afr. 2014, 2, 224–234. [Google Scholar]

- Amidu, A.R. Research in valuation decision making processes: Educational insights and perspectives. J. Real Estate Pract. Educ. 2011, 14, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institution of Surveyors of Kenya. Kenya Valuation Standards: The Blue Book; Institution of Surveyors of Kenya: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Syagga, P.M. Training and Conduct of Graduate Valuers. Presented at the Institution of Surveyors of Kenya Workshop for Principals in the Chapter of Valuation and Estate Management. Nairobi, Kenya, 21 August 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Valuers Act 1984. Cap 532 of the Laws of Kenya. 2012. Available online: http://www.kenyalaw.org (accessed on 6 April 2020).

- Land Value (Amendment) Act. 2019. Available online: http://www.kenyalaw.org (accessed on 7 March 2020).

- Mwangi, G.W. Development of Integrated Land Information Management System in Kenya. Master’s Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Iroham, C.O.; Ogunba, O.A.; Oloyede, S.A. Relative level of occurrence of the principal heuristics in Nigeria property valuation. Int. J. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 2, 493–504. [Google Scholar]

- Osmond, I.C. Heuristics in Property Investment Valuation in Nigeria. Ph.D. Thesis, Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Awuah, K.G.; Proverbs, D.; Lamond, J.; Gyamfi-Yeboah, F.; Eriksson, C.; Arnold, A. An Evaluation of Property Valuation Practice in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Case Study of Ghana; RICS: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mutema, M. Property Valuation Challenges in Africa: The Case of Selected African Countries. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual World Bank Conference on Land Policy and Poverty, Washington, DC, USA, 14–17 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Beale, T. Real estate theory vs. practice: A case study of valuation practices of Jamaican valuers. Apprais. J. 2015, 83, 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, N. Valuation accuracy, variation and bias in the context of standards and expectations. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2000, 18, 130–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreal, S.; de La Paz, P.T. An analysis of factors influencing accuracy in the valuation of residential properties in Spain. J. Prop. Res. 2012, 29, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska-Stasiak, E. Reproduction of the real estate valuation methodology in practice. An attempt at identifying sources of divergences. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2014, 22, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, S.; Pace, K. Distressed properties: Valuation bias and accuracy. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2010, 2012, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iroham, C.O.; Ogunba, O.A.; Oloyede, S.A. Effect of principal heuristics on accuracy of property valuation in Nigeria. J. Land Rural Stud. 2014, 2, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, N.; Lizieri, C.; McAllister, P. Means, motive and opportunity? Disentangling client influence on performance measurement appraisals. J. Prop. Res. 2010, 27, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mooya, M.M. Real Estate Valuation Theory: A Critical Appraisal; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.; Schuck, E. The influence of clients on valuations. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 1999, 17, 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.; Schuck, E. The influence of clients on valuations: The clients’ perspective. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2005, 23, 182–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worzala, E.M.; Lenk, M.M.; Kinnard, W.N. How client pressure affects appraisal of residential property. Real Apprais. J. 1998, 66, 416–427. [Google Scholar]

- Wolverton, M.L.; Gallimore, P. Client feedback and the role of the appraiser. J. Real Estate Res. 1999, 18, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallimore, P.; Wolverton, M.L. The objective in valuation: A study of the influence of client feedback. J. Prop. Res. 2000, 17, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freybote, J.; Ziobrowski, A.J.; Gallimore, P. Residential real estate appraisal bias in the absence of client feedback. J. Hous. Res. 2014, 23, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.Y.; Yu, S.M. Client influence on valuation: Does language matter? A comparative analysis between Taiwan and Singapore. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2009, 27, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidu, A.R.; Aluko, B.T.; Hansz, J.A. Client feedback pressure and the role of estate surveyors and valuers. J. Prop. Res. 2008, 25, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, G. Professional socialisation of valuers: What the literature and professional bodies offers. Int. Educ. J. 2005, 5, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gitau, G.G.; Kiragu, D.N.; Kamau, R. Effect of Heuristic Factors and Real Estate Investment in Embu County, Kenya. Int. J. Acad. Res. Account. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2018, 8, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrobek, S.; Kucharska-Stasiak, E.; Trojanek, M.; Adamiczka, J.; Budzyński, T.; Cellmer, R.; Dąbrowski, J.; Jasińska, E.; Preweda, E.; Sajnóg, N. Current Problems of Valuation and Real Estate Management by Value; Croatian Information Technology Society: Zagreb, Croatia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Osmond, I.C.; Adebayo, O.O.; Adesiyan, O.S.; Moronke, O.M. Factors affecting the usage of major heuristics in Nigeria property investment valuation. J. Sustain. Dev. Stud. 2013, 4, 114–133. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, J., III. Behavioural Research in Appraisal and Some Perspectives on Implications for Practice; RICS Foundation: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chinloy, P.; Cho, M.; Megbolugbe, I.F. Appraisals, Transaction Incentives, and Smoothing. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 1997, 14, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansz, A. The use of a pending mortgage reference point in valuation judgment. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2004, 22, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, P.; Baum, A.; Crosby, N.; Gallimore, P.; Gray, A. Appraiser behavior and appraisal smoothing: Some qualitative and quantitative evidence. J. Prop. Res. 2003, 20, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, J., III. An investigation into the impact of previous expert value estimates on appraisal judgement. J. Real Estate Res. 1997, 13, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, J., III; Hansz, A. How valuers use the value opinions of others. J. Prop. Valuat. Invest. 1997, 15, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, J., III; Hansz, A. The use of reference points in valuation judgement. J. Prop. Res. 2001, 18, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, N.; Lavers, A.; Murdoch, J. Property valuation variation and the margin of error in the UK. J. Prop. Res. 1998, 15, 305–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, A.L.; Bitter, C. Spatial econometrics, land values and sustainability: Trends in real estate valuation research. Int. J. Urban Policy Plan. 2012, 29, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, A.; Berry, J.; McGreal, S. Valuation of residential property: Analysis of participant behaviour. J. Prop. Valuat. Invest. 1996, 14, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Kenya Gazette. 2020. Available online: http://kenyalaw.org/kenya_gazette/gazette/year/2020 (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- Kumar, R. Research Methodology: A Step by Step Guide for Beginners, 3rd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Teddlie, C.; Tashakkori, A. Foundation of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Institution of Surveyors of Kenya. Regulations and Syllabus—VEMS, LMS and BS Chapters. 2018. Available online: http://www.isk.or.ke (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, J.O.; Cunningham, J.B. Using IBM SPSS Statistics: An Interactive Hands-On Approach, 2nd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).