Community Perceptions of Tree Risk and Management

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- What practices are cities undertaking to reduce risk while managing canopy benefits?

- (2)

- How do community leaders characterize tree risk perceptions in their communities?

- (3)

- How do resident attitudes inform tree care and municipal forest management?

1.1. Urban Forest Management

1.1.1. Criteria and Indicators of Success

1.1.2. Urban Forest Risk Management

1.2. Community Risk Perceptions

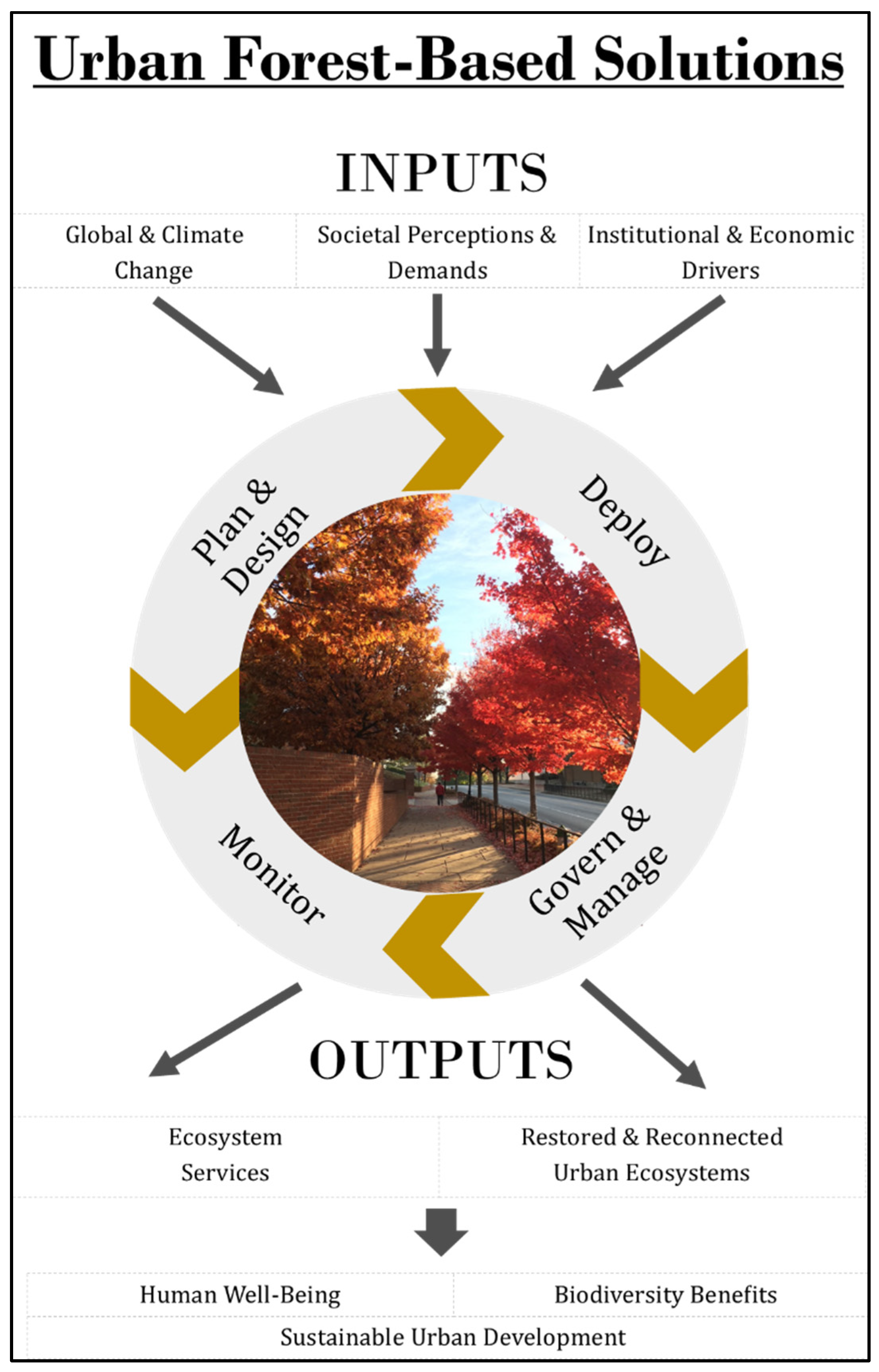

Urban Forest-Based Solutions Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Data Collection

3. Results

3.1. Community Descriptions and Risk Mitigation Practices

3.1.1. Structure

3.1.2. Practices

3.1.3. Challenges

So I hate to sound like every other government person that’s talked about resources, but the reality is that our tree budgets have not increased in 15 years. And what they used to buy, they buy a lot less of from the inflation of services. Forty thousand dollars used to get you 30 to 40 tree removals. It now gets you 15 maybe.(Municipal administrator, Aurora)

I think that comes down to resources and time. I also think if it was widely advertised that there was a [city forester], they’d probably need three [of them to meet demand]. I don’t think the county could afford that either.(Community environmental group member, Aurora)

3.2. Resident Perceptions and Actions to Reduce Tree Risks on Private Property

3.2.1. Responsibility for Risk

From my own experience, I don’t see a lot of people taking initiative or caring as much about the trees that are directly in their backyard or on their street. They’re going to gravitate towards the places that are maybe government-owned or publicly-managed or privately owned or whatever—the places that other people have to take care of, rather than putting in the effort to take care of the space in their own neighborhoods. But then I think that also goes into the issue of depending on who owns the land, what happens to that land can like be drastically different.(News media participant, Aurora)

Urban tree risk, in my mind, is a shared responsibility. There is the requirement for the municipality to be responsible for trees in their rights of ways and to educate the population about trees on their property—which they refuse to do because the residents don’t want the government telling them what to do.(Public tree manager, Chandler)

3.2.2. Factors Contributing to Failure to Mitigate Risk on Private Property

Well, I don’t think they really take a look until there’s something wrong. [laughing] You know, nobody’s going to really pay attention until something happens.(Community environmental group member, Chandler)

It’s sad because a lot of what we do is relatively expensive, versus like, getting your lawn sprayed. For $35 to $50 bucks six times a year, you got a good-looking lawn. When it translates into trees, it’s usually less frequent but more expensive.(Private arborist, Chandler)

I’ve had a number of people say to me, “Hey, I had a tree fall and hit my house. I’m going to cut every tree within 60 yards of my house down.” So that’s definitely something I’ve heard more than I’d like to.(Public tree manager, Leeds)

Because most people can point out a dead tree, but a lot of people can’t figure out that [although] the tree is green and healthy and looks great, it’s a ticking time bomb waiting to break at the base because of this cavity you can’t see for the vines that are growing around it.

It sometimes can be bad because folks really are so interested in trees that they sometimes only see planting trees as a positive. They don’t really recognize how the maintenance of trees is so important.(Municipal administrator, Aurora)

3.3. Resident Perceptions and Actions to Mitigate Tree Risk at the Community Level

3.3.1. Values and Behaviors towards Public Trees

I think the biggest thing is aesthetic beauty of a town. It looks more genuine, more welcoming if you have a mixture of plants and trees. Just going in and doing a cityscape with nothing but concrete, is not something anybody will—It’s just not appealing.(Real estate developer, Chandler)

I think shade and making the area attractive to want to be in, to spend time in, is actually one of the most important benefits. And I think that’s what people appreciate [here].(Community environmental group member, Aurora)

When you go to an area and there isn’t trees and there’s a lot of development… it just doesn’t feel right. It doesn’t look right. So I think having those trees, it provides shade, it provides the buffers between properties, it provides ambiance and a feeling—this may just be perceived but I think you feel healthier when you’re around trees in your environment, when they’re there and they appear to be healthy. You know there’s birds—there’s things that there’s supposed to be. So, I think that’s a good thing.(Real estate developer, Aurora)

I would think that they would want a piece of property that is not stripped out. That to me is the ideal country living. Where you’ve got pecan trees or oak trees or pine trees and a pond or a field to plant a garden in. I do feel the trees are important in that rural area.(Real estate developer, Clovis)

I think most people don’t appreciate some of the things we like to talk about, like traffic-calming and carbon sequestration and stuff like that. Definitely, [they appreciate] more of the aesthetic value [of the urban forest]—what it brings to the community and feeling like they’ve taken care of the town appearance. [It’s] more of a sentimental aesthetic value than anything else in these small towns with trees.(Public administrator, Leeds)

3.3.2. Risk Governance

The biggest response is they want it cleaned up. [chuckles] As far as the debris and things… if it’s a fallen tree, get it cleaned up and get it out of the way.(Real estate developer, Chandler)

Our stormwater inspectors are on site on these commercial projects fairly regularly. I’ve got good communication with those folks. They have been more and more proactive about it; I really have to commend them. Even if it’s just something of, “Hey, we need you to come out here and take a look at this.” “Maybe everything’s okay but come out here and take a look.” And so those folks have been great. They’re generally my eyes because I don’t go out on site and inspect sites until they’re done.(Public tree manager, Aurora)

I do think the city, if they could do anything better, it might be that they could help educate me better so that people like myself could pass it along. Maybe tap people on the shoulder so that there are business leaders inside the city, so that we could make sure that we pass that on to everybody else.(Real estate developer, Chandler)

4. Discussion

Urban Forest Management

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moeller, G.H. The Pinchot Institute: Toward Managing our Urban Forest Resources. J. Arboric. 1997, 4, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, D.J.; Randler, P.B.; Greenfield, E.J.; Comas, S.J.; Carr, M.A.; Alig, R.J. Sustaining America’s Urban Trees and Forests: A Forests on the Edge Report; Gen. Tech. Rep. NRS-62; Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Seamans, G.S. Mainstreaming the environmental benefits of street trees. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J. Institutionalizing urban forestry as a “biotechnology” to improve environmental quality. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 5, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, B.R. How the Public Values Urban Forests. J. Arboric. 1992, 18, 98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehler, E.; Hathaway, J.; Tirpak, A. Quantifying the benefits of urban forest systems as a component of the green infrastructure stormwater treatment network. Ecohydrology 2017, 10, e1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincetl, S. Implementing Municipal Tree Planting: Los Angeles Million-Tree Initiative. Environ. Manag. 2009, 45, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nowak, D.J.; Dwyer, J.F. Understanding the Benefits and Costs of Urban Forest Ecosystems. In Urban and Community Forestry in the Northeast; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; De Vries, S.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Schellevis, F.G.; Groenewegen, P. Morbidity is related to a green living environment. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dombrow, J.; Rodriguez, M.; Sirmans, C.F. The Market Value of Mature Trees in Single-Family Housing Markets. Apprais. J. 2000, 68, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez, C.; Threlfall, C.G.; Kendal, D.; Hochuli, D.F.; Davern, M.; Fuller, R.A.; van der Ree, R.; Livesley, S.J. Urban forest governance and decision-making: A systematic review and synthesis of the perspectives of municipal managers. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C. Political and Administrative Factors in Urban Forestry Programs. J. Arboric. 1982, 8, 160–164. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll, A.N.; Ries, P.D.; Tilt, J.H.; Ganio, L.M. Needs and barriers to expanding urban forestry programs: An assessment of community officials and program managers in the Portland—Vancouver metropolitan region. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmendorf, W.F.; Cotrone, V.J.; Mullen, J.T. Trends in Urban Forestry Practices, Programs, and Sustainability: Contrasting a Pennsylvania, U.S., Study. Arboric. Urban For. 2003, 29, 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Grado, S.; Measells, M.; Grebner, D. Revisiting the Status, Needs, and Knowledge Levels of Mississippi’s Governmental Entities Relative to Urban Forestry. Arboric. Urban For. 2013, 39, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauer, R.J.; Peterson, W.D. Municipal Tree Care and Management in the United States: A 2014 Urban & Community Forestry Census of Tree Activities; Special Publication 16-1; College of Natural Resources, University of Wisconsin—Stevens Point: Stevens Point, WI, USA, 2016; 71p. [Google Scholar]

- Treiman, T.; Gartner, J. Community Forestry in Missouri, U.S.: Attitudes and Knowledge of Local Officials. J. Arboric. 2004, 30, 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Young, R.F. Mainstreaming urban ecosystem services: A national survey of municipal foresters. Urban Ecosyst. 2013, 16, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Global Change Research Program. Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment; Global Change Research Program 2017–2018: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://science2017.globalchange.gov/ (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Slovic, P. Perception of Risk: Reflections on the Psychometric Paradigm. In Social Theories of Risk; Krimsky, S., Golding, D., Eds.; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 1992; pp. 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gullick, D.; Blackburn, G.; Whyatt, J.; Vopenka, P.; Murray, J.; Abbatt, J. Tree risk evaluation environment for failure and limb loss (TREEFALL): An integrated model for quantifying the risk of tree failure from local to regional scales. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2019, 75, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Guikema, S.; Kane, B. Statistical modeling of tree failures during storms. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 177, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrell, J. Balancing tree benefits against tree security: The duty holder’s dilemma. Arboric. J. 2012, 34, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, J.C. Planning the Urban Forest: Ecology, Economy, and Community Development. 2009. Available online: https://www.planning.org/publications/report/9026879/ (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Kenney, W.A.; van Wassenaer, P.J.E.; Satel, A.L. Criteria and Indicators for Strategic Urban Forest Planning and Management. Arboric. Urban Plan. 2011, 37, 108–117. [Google Scholar]

- Baur, J.W.; Tynon, J.F.; Ries, P.; Rosenberger, R.S. Public attitudes about urban forest ecosystem services management: A case study in Oregon cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 17, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janse, G.; Konijnendijk, C.C. Communication between science, policy and citizens in public participation in urban forestry—Experiences from the Neighbourwoods project. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, J.F.; Schroeder, H.W. The Human Dimensions of Urban Forestry. J. For. 1994, 92, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sievert, R.C. Public awareness and urban forestry in Ohio. J. Arboric. 1988, 14, 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, J.S.; Luloff, A.; Stedman, R.C. A Multisite Qualitative Comparison of Community Wildfire Risk Perceptions. J. For. 2012, 110, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carmichael, C.E.; McDonough, M.H. The trouble with trees? Social and political dynamics of street tree-planting efforts in Detroit, Michigan, USA. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavy, B.; Hagelman, R.R. Protecting the urban forest: Variations in standards and sustainability dimensions of municipal tree preservation ordinances. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, T.; Urbani, L. Variations in municipal urban forestry policies: A case study of Toronto, Canada. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galenieks, A. Importance of urban street tree policies: A Comparison of neighbouring Southern California cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 22, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricard, R.M. Shade Trees and Tree Wardens: Revising the History of Urban Forestry. J. For. 2005, 103, 230–233. [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny, J.D. Urban Tree Risk Management: A Community Guide to Program Design and Implementation; USDA Forest Service Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2003. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/11070 (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Adams, J. Dangerous trees? Arboric. J. 2007, 30, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeser, A.K.; Hauer, R.J.; Miesbauer, J.W.; Peterson, W. Municipal tree risk assessment in the United States: Findings from a comprehensive survey of urban forest management. Arboric. J. 2016, 38, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, M. Moving the Focus from Tree Defects to Rational Risk Management—A Paradigm Shift for Tree Managers. Arboric. J. 2007, 30, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, M.J.; Kane, B. Hazard tree liability in the United States: Uncertain risks for owners and professionals. Urban For. Urban Green. 2004, 2, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, N. Towards Reasonable tree risk decision-making? Arboric. J. 2007, 30, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.; Koeser, A.; Hauer, R.; Hansen, G.; Escobedo, F. Risk Assessment and Risk Perception of Trees: A Review of Literature Relating to Arboriculture and Urban Forestry. Arboric. Urban For. 2019, 45, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenburg, W.R. Heuristics, Biases, and the Not-So-General Publics: Expertise and Error in the Assessment of Risks. In Social Theories of Risk; Krimsky, S., Golding, D., Eds.; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kunreuther, H. A Conceptual Framework for Managing Low-Probability Events. In Social Theories of Risk; Krimsky, S., Golding, D., Eds.; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 1992; pp. 12–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science 1974, 185, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynne, B. Risk and Social Learning: Reification to Engagement. In Social Theories of Risk; Krimsky, S., Golding, D., Eds.; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 1992; pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Visschers, V.; Meertens, R.M.; Passchier, W.F.; Devries, N.K. How Does the General Public Evaluate Risk Information? The Impact of Associations with Other Risks. Risk Anal. 2007, 27, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O. Perception of Risks. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance. Issues Pract. 2004, 29, 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kasperson, R.E. The Social Amplification of Risk: Progress in Developing an Integrative Framework. In Social Theories of Risk; Krimsky, S., Golding, D., Eds.; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 1992; pp. 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- De Vreese, R. Urban Forest-Based Solutions for Resilient Cities. 2018. Available online: Resilience-blog.com (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Adger, W.N.; Hughes, T.P.; Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Rockström, J. Social-Ecological Resilience to Coastal Disasters. Science 2005, 309, 1036–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Godschalk, D.R. Urban Hazard Mitigation: Creating Resilient Cities. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2003, 4, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonnes, J. Urban Forests: A Natural History of Trees in the American Cityscape; Viking: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, S.E.; Handley, J.F.; Ennos, A.R.; Pauleit, S. Adapting Cities for Climate Change: The Role of the Green Infrastructure. Built Environ. 2007, 33, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steenberg, J.; Duinker, P.N.; Nitoslawski, S. Ecosystem-based management revisited: Updating the concepts for urban forests. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 186, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, E.; Johnson, M.; Roman, L.; Sonti, N.; Pregitzer, C.; Campbell, L.; McMillen, H. A Literature Review of Resilience in Urban Forestry. Arboric. Urban For. 2020, 46, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Census Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: 1 April 2010 to 1 July 2018; US Census Bureau: Washington, DA, USA, 2019. Available online: http://www.census.gov/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, B. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 5th ed.; Pearson/Allyn & Bacon: Boston, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D. Focus Groups. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1996, 22, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R.E. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, K.; Petrokofsky, G. The natural capital of city trees. Science 2017, 356, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeser, A.K.; Klein, R.W.; Hasing, G.; Northrop, R.J. Factors driving professional and public urban tree risk perception. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 968–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, L.; Flores, D.; Hong, C.-Y. The impact of extreme weather events on community risk planning and management: The case of San Juan, Puerto Rico after hurricane Maria. Urbe. Revista Brasileira de Gestão Urbana 2020, 12, 20190062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskell, C.; Allred, S.B. Residents’ beliefs about responsibility for the stewardship of park trees and street trees in New York City. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 120, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, M.; Escobedo, F.J.; Stein, T.; Orfanedes, M.; Northrop, R. Community Leader Perceptions and Attitudes toward Coastal Urban Forests and Hurricanes in Florida. South. J. Appl. For. 2012, 36, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, C.; Duinker, P.N. An analysis of urban forest management plans in Canada: Implications for urban forest management. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 116, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hewitt, V.; Mackres, E.; Shickman, K. Cool Policies for Cool Cities: Best Practices for Mitigating Urban Heat Islands in North American Cities; American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; 53p. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, K. The Community in Rural America; Greenwood Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Z.-H.; Kaloush, K.E.; Shacat, J. Perceptions of urban heat island mitigation and implementation strategies: Survey and gap analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 66, 102687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Site | Population | Growth Rate (%) | Median Income ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aurora | 100,000 | +0.80 | 36,000 |

| Chandler | 50,000 | +5.00 | 56,000 |

| Leeds | 5000 | −0.80 | 19,000 |

| Clovis | 1000 | −1.70 | 33,000 |

| Key Informant Type | Aurora | Chandler | Leeds | Clovis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public tree manager | 12 | 11 | 1 | 0 |

| Municipal administrator | 14 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| Private arborist | 12 | 16 | 0 | 1 |

| Community environmental group member | 14 | 14 | 2 | 0 |

| Real estate developer | 15 | 14 | 0 | 2 |

| News media participant | 14 | 12 | 1 | 0 |

| County extension agent | 11 | 11 | 1 | 1 |

| State Forestry Commission representative | 11 | 11 | 1 | 1 |

| TOTAL PARTICIPANTS | 23 | 23 | 7 | 6 |

| Study Site | Tree Management Personnel | Risk Mitigation Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Aurora | Community Forester (C.A.) * | Maintain city tree inventory |

| Arborist-Planner II (C.A.) | Conduct basic tree risk assessments | |

| Public Works Superintendent | Prescribe preventative pruning activities | |

| Sustainability Officer | Respond to requests for public tree assessments | |

| Beautification Director | Conduct private property outreach/assessments | |

| Landscape Management Administrator | Monitor right-of-way and utility pruning cycles | |

| Community Tree Board (volunteers) | Document tree failure rates | |

| Streets & Drainage crews | Contract for hazard tree removals | |

| Landscape Management crews | Remove storm debris affecting rights-of-way | |

| Enforce tree ordinances before, during, and after development activities | ||

| Chandler | Zoning Administrator | Conduct basic tree risk assessments upon request |

| Public Works Director | Respond to requests for public tree assessments | |

| Sustainability Manager | Provide private property outreach/assessments | |

| Tree Board | Conduct right of way/utility pruning cycles | |

| Public Works crews | Contract for hazard tree removals | |

| Remove storm debris affecting rights-of way | ||

| Leeds | Public Works Manager | Conduct right of way/utility pruning |

| Public Works crew | Conduct limited visual assessments annually | |

| Respond to requests for public tree assessments | ||

| Contract for hazard tree removal | ||

| Remove storm debris affecting rights-of way | ||

| Clovis | Mayor | Respond to requests for public tree assessments |

| City maintenance crew | Request state Department of Transportation for pruning/hazard response on state roadways |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Judice, A.; Gordon, J.; Abrams, J.; Irwin, K. Community Perceptions of Tree Risk and Management. Land 2021, 10, 1096. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101096

Judice A, Gordon J, Abrams J, Irwin K. Community Perceptions of Tree Risk and Management. Land. 2021; 10(10):1096. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101096

Chicago/Turabian StyleJudice, Abbie, Jason Gordon, Jesse Abrams, and Kris Irwin. 2021. "Community Perceptions of Tree Risk and Management" Land 10, no. 10: 1096. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101096

APA StyleJudice, A., Gordon, J., Abrams, J., & Irwin, K. (2021). Community Perceptions of Tree Risk and Management. Land, 10(10), 1096. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101096