Combined Coagulation and Ultrafiltration Process to Counteract Increasing NOM in Brown Surface Water

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Its sensitivity and the limits of the coagulant dose for NOM removal

- The use of optical sensors for online dosing of coagulants

- Its vulnerability to a further decrease in raw water quality.

2. Material and Methods

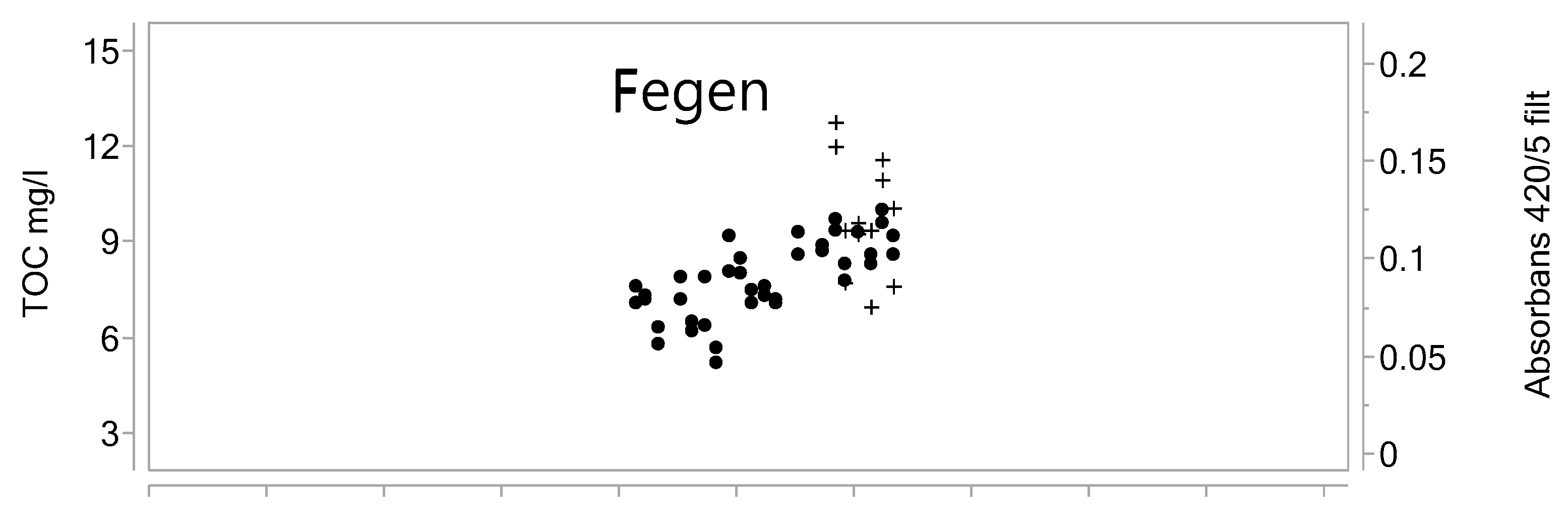

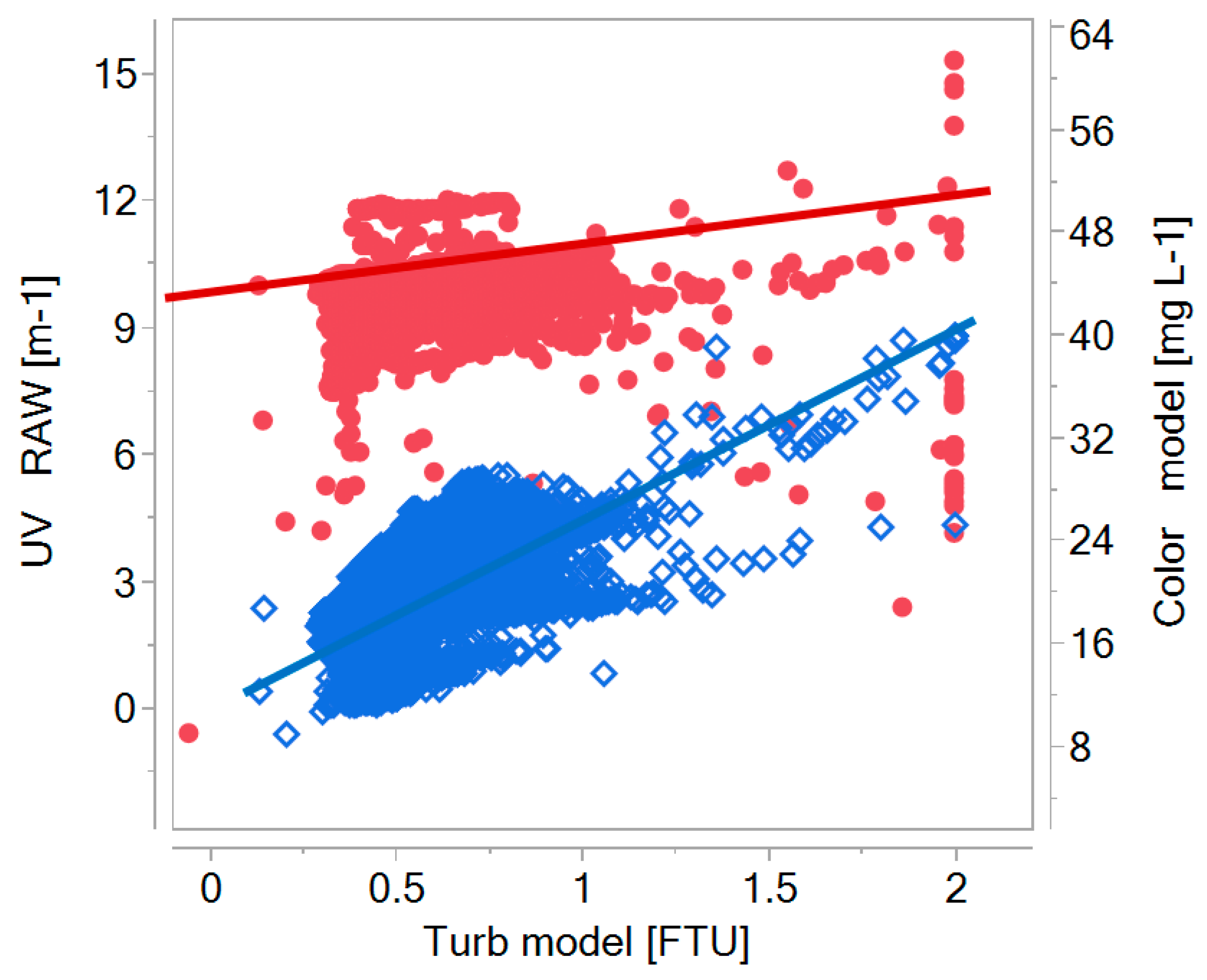

2.1. Raw Water Source Quality

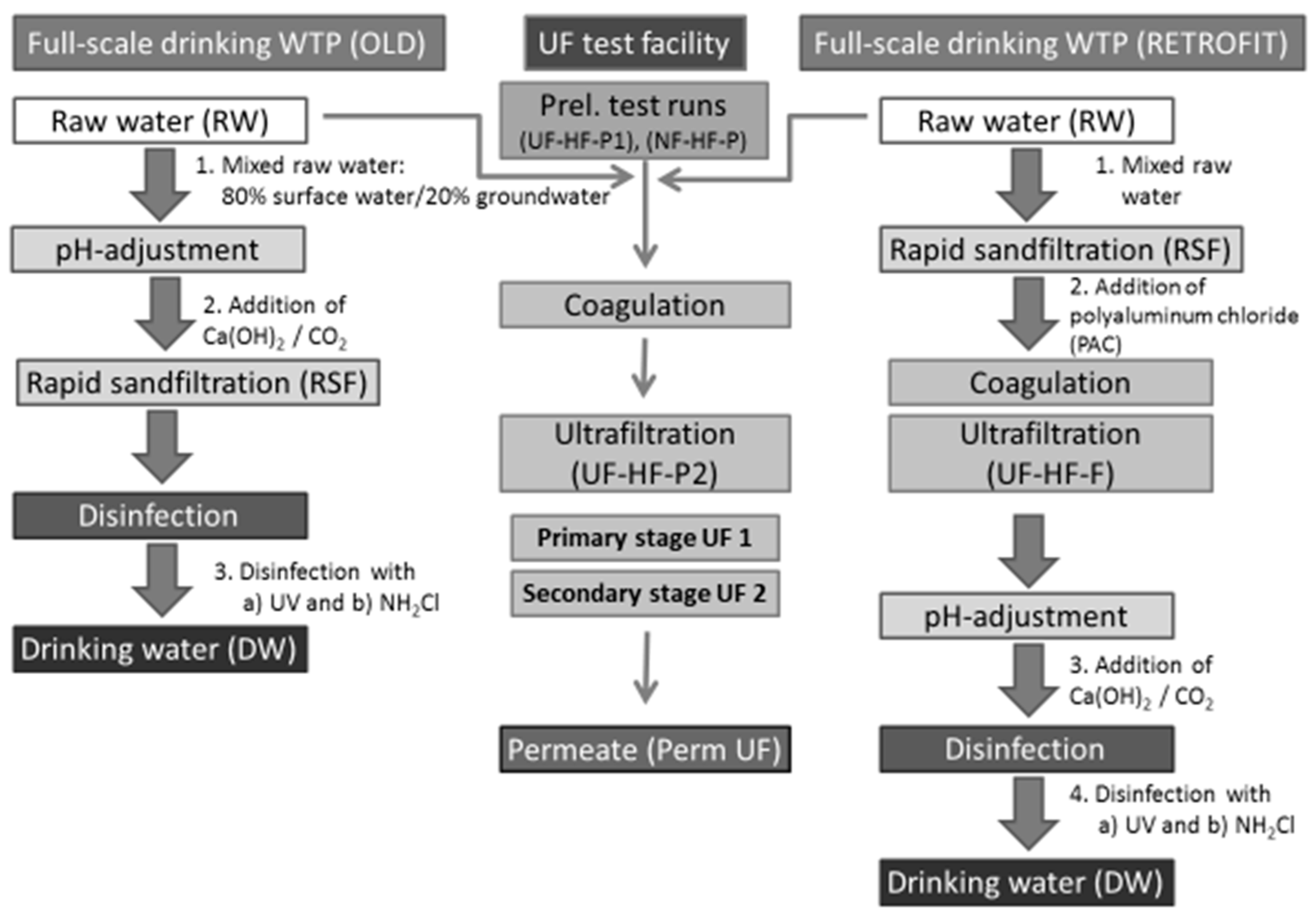

2.2. UF Full-Scale Design and Pilot Studies

2.2.1. Retrofit of Full-Scale Plant and Pilot Trials

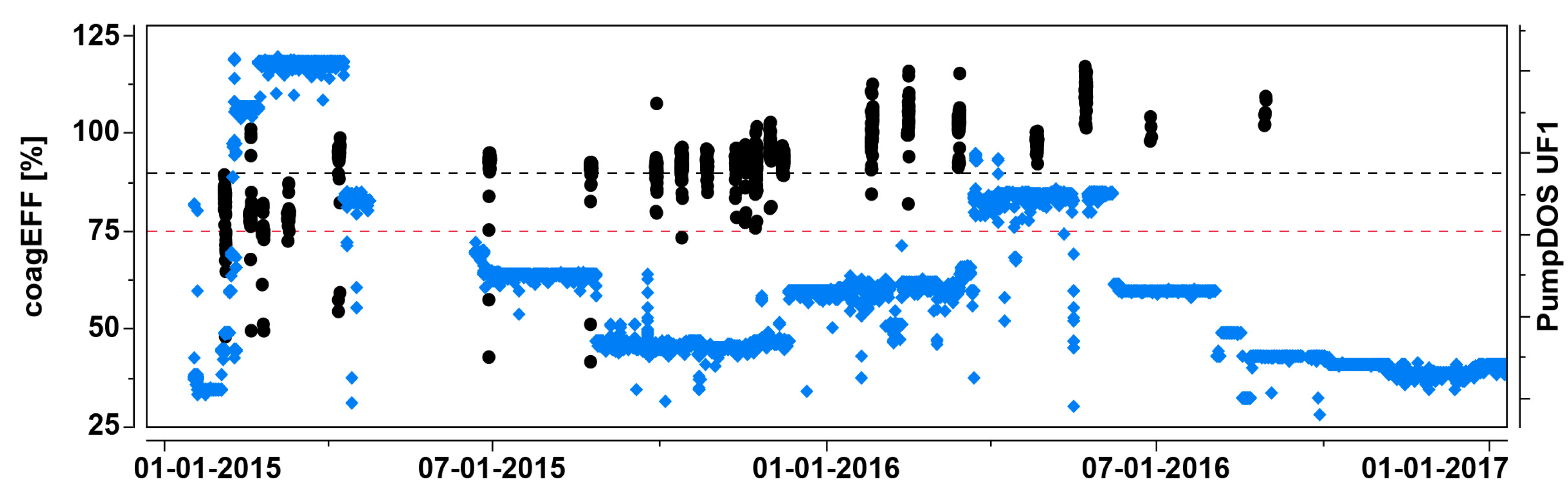

2.2.2. Control Philosophy of Pin-Floc Coagulation for Full-Scale UF Plant

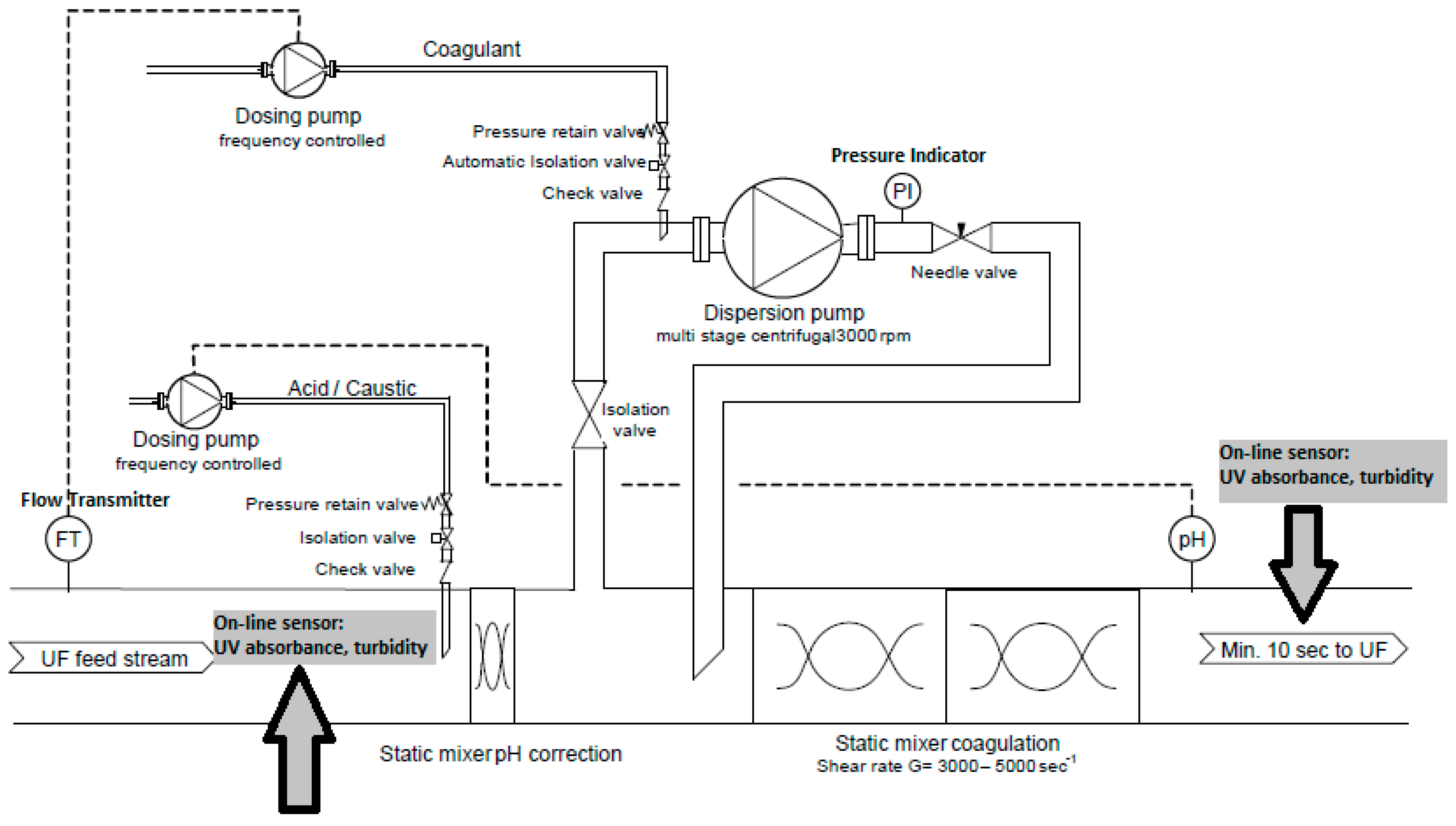

2.2.3. Two-Stage UF Test Facility (UF-HF-P2)

- Feed section, including dosing equipment for coagulant and chemicals for pH correction,

- Membrane system (two-stage UF), including air integrity testing,

- Permeate and backwash section, including chemical dosing for membrane cleaning.

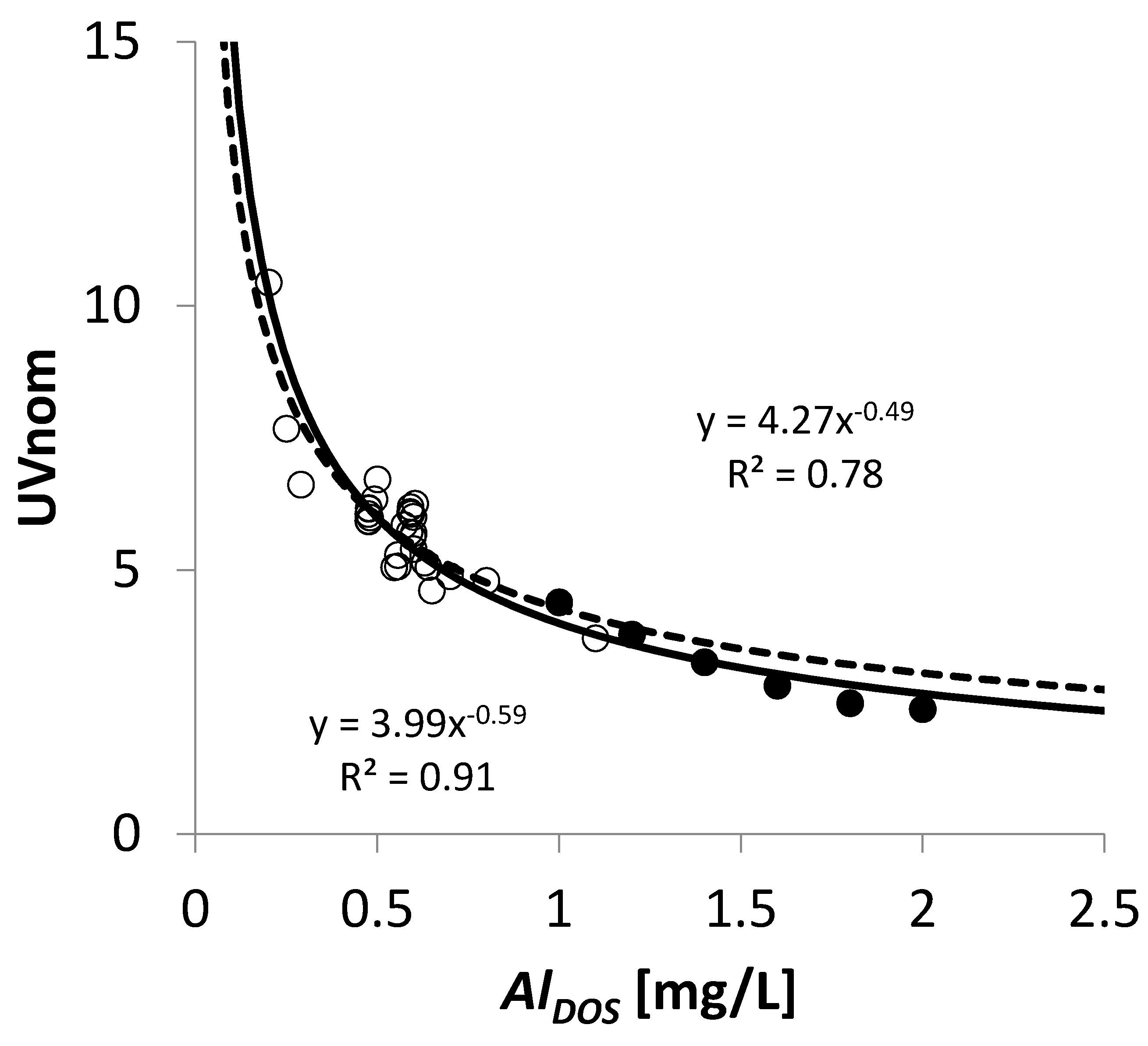

2.2.4. Coagulant Dosing System for UF Test Facility

- is the coagulant dosing concentration (mg Metal L−1)

- is the conversion factor for turbidity [-] (was set to zero during the pilot trials)

- is the conversion factor for UV absorbance [-] (range: 0.005–0.035)

- is the feed water turbidity (FTU)

- is the feed water UV absorbance (m−1)

- A is a set point for the base coagulant dosage (range: 0.2–2.0).

2.2.5. Evaluation of Coagulation Efficiency

2.3. Characterisation of Organic Fractions in Feed Water and Treated Water

2.3.1. Determination of UV, TOC, and DOC

2.3.2. Evaluation of NOM Retention by LC-OCD

2.3.3. Absorbance and Fluorescence Characterisation and Additional DOC and TOC

2.4. Optical Sensors for Online Process Control and Dosing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preliminary Membrane Trials Using NF (NF-HF-P) and UF (UF-HF-P1)

3.2. Pilot Trials Using the Two-Stage UF Pilot Plant Test Facility (UF-HF-P2)

- Impact of in-line coagulation on NOM removal and membrane performance

- Effect of operation at high flux (maxflux and subsequent regaining of permeability)

- Varying feed water quality (e.g., surface water only or variation in surface water NOM content).

3.2.1. Pilot Trials (UF-HF-P2): Episode 1—Effect of in-Line Coagulation

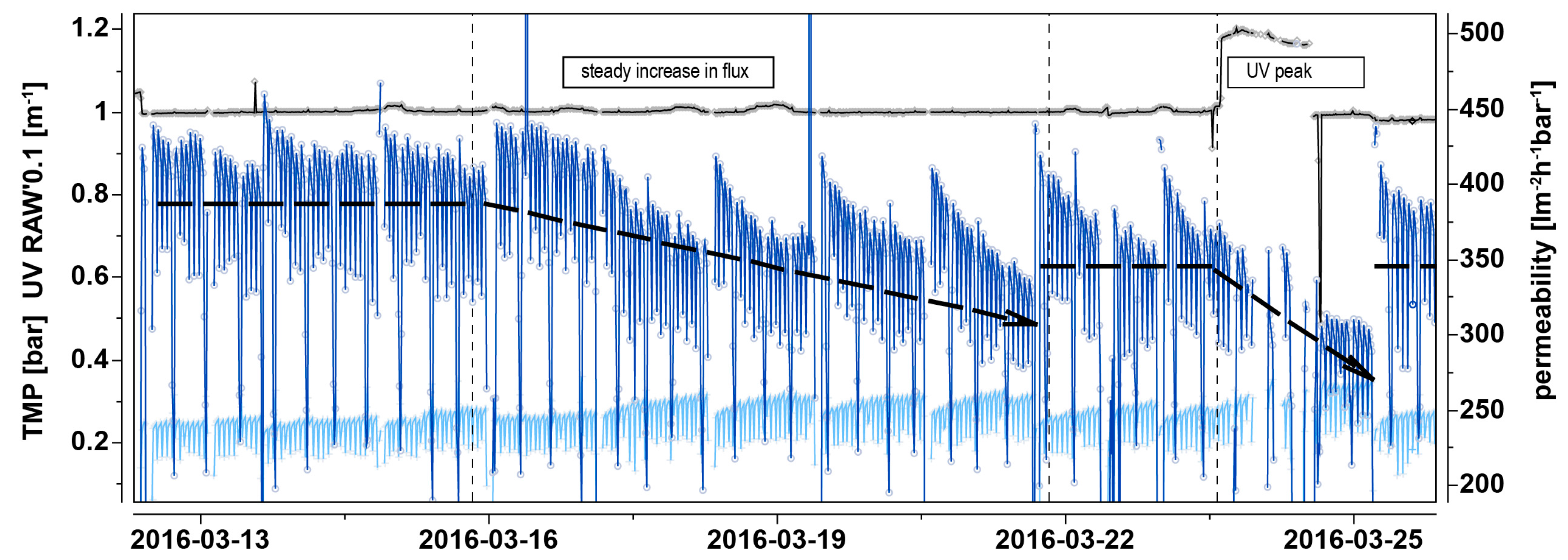

3.2.2. Pilot Trials (UF-HF-P2): Episode 2—High-Flux Testing

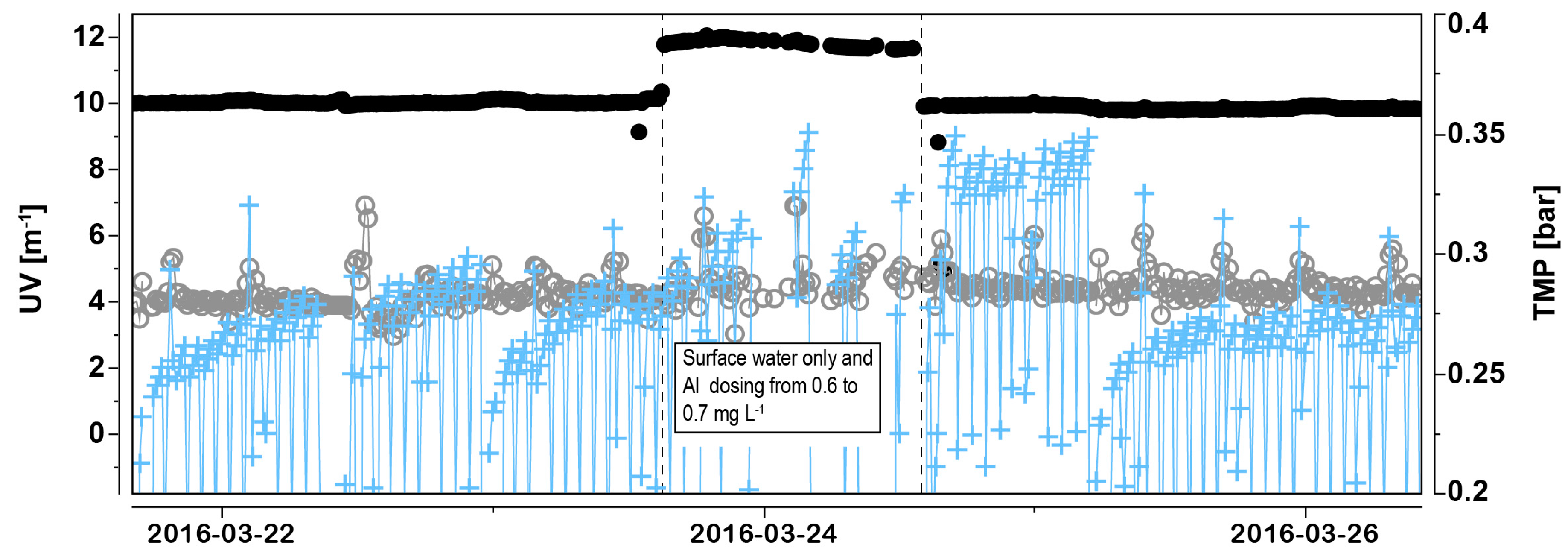

3.2.3. Pilot Trials (UF-HF-P2): Episode 3—Varying Feed Water Quality

3.3. Characterisation of Organic Matter in the Raw and Permeated Water

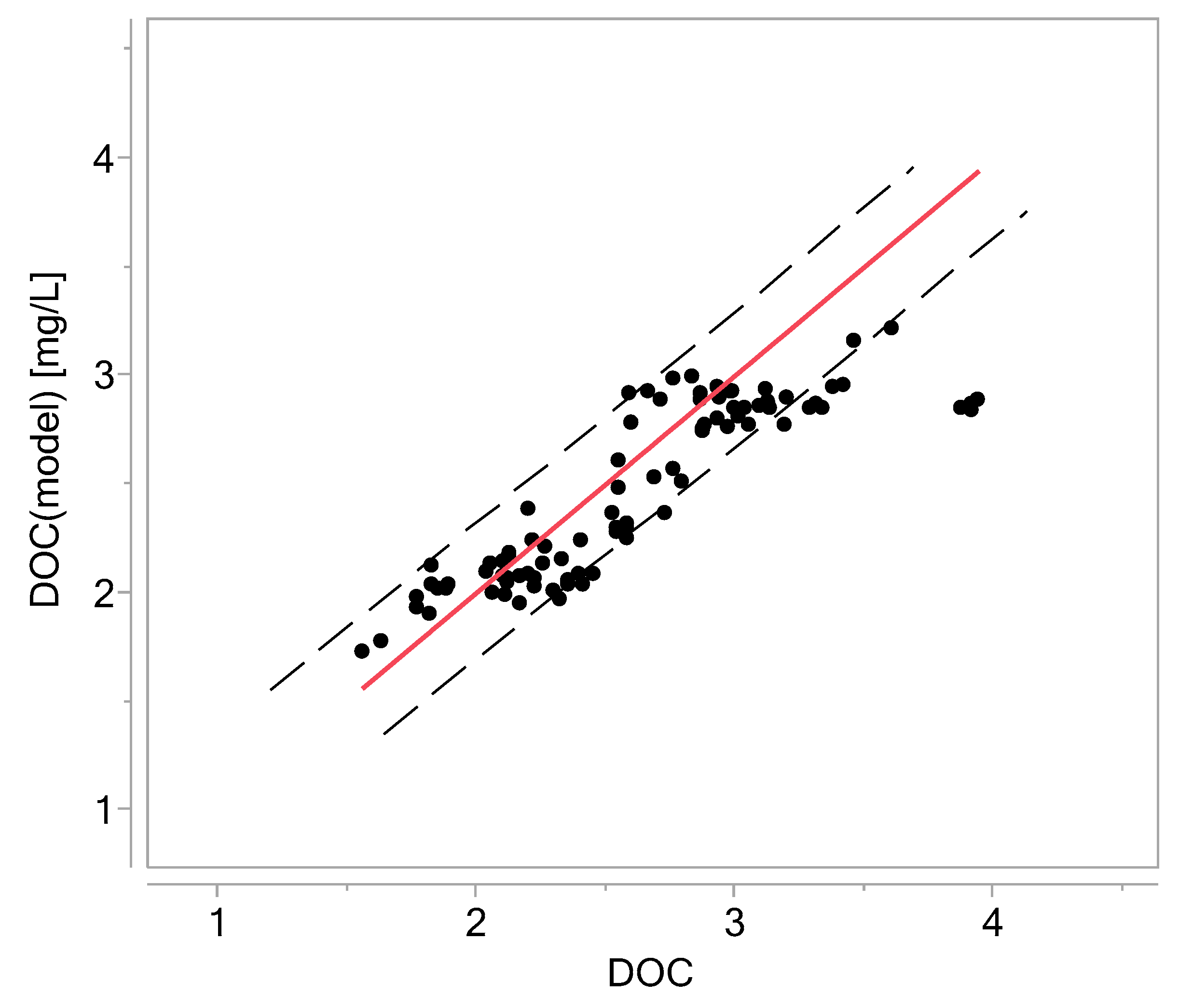

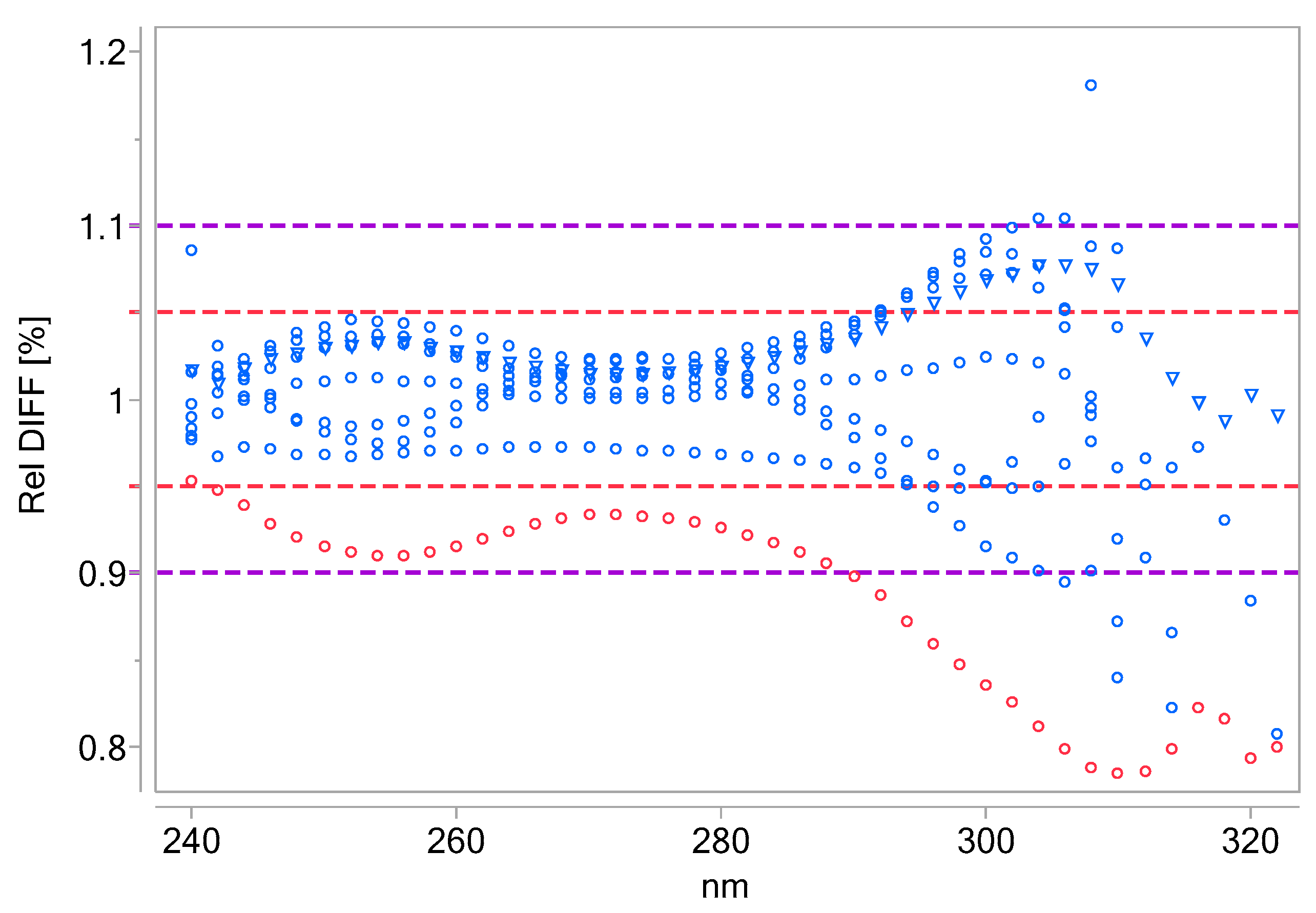

3.3.1. Absorbance and Fluorescence Data Evaluation

3.3.2. LC-OCD Data Evaluation

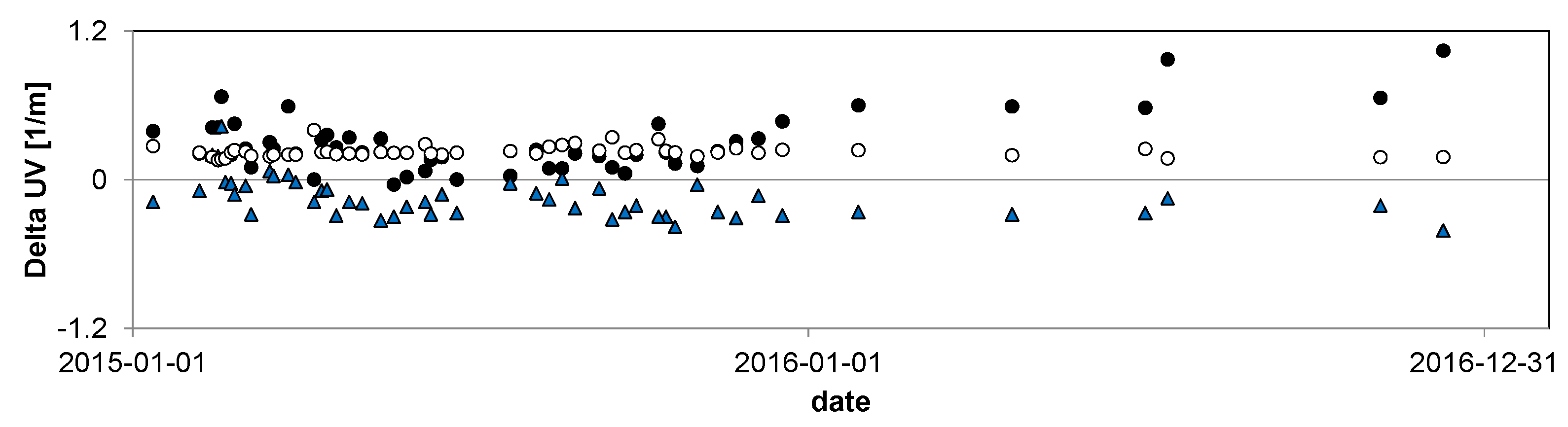

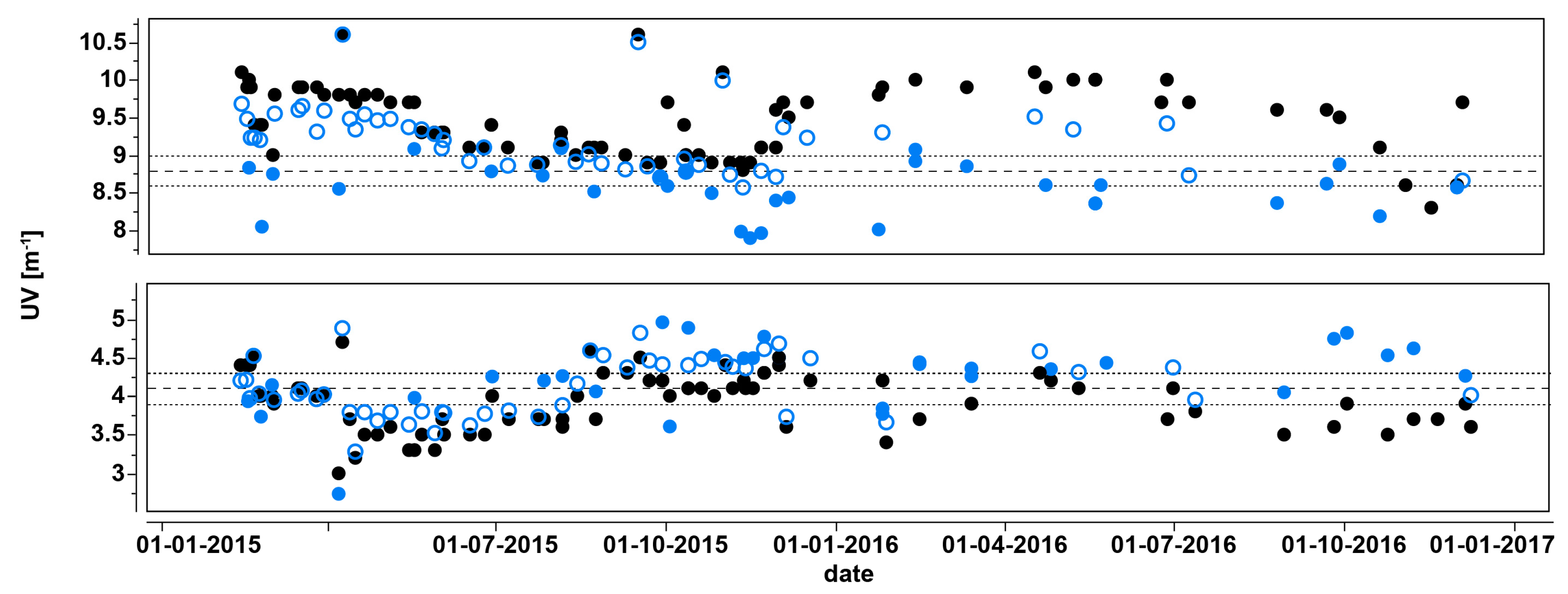

3.4. UV Sensor Data Evaluation

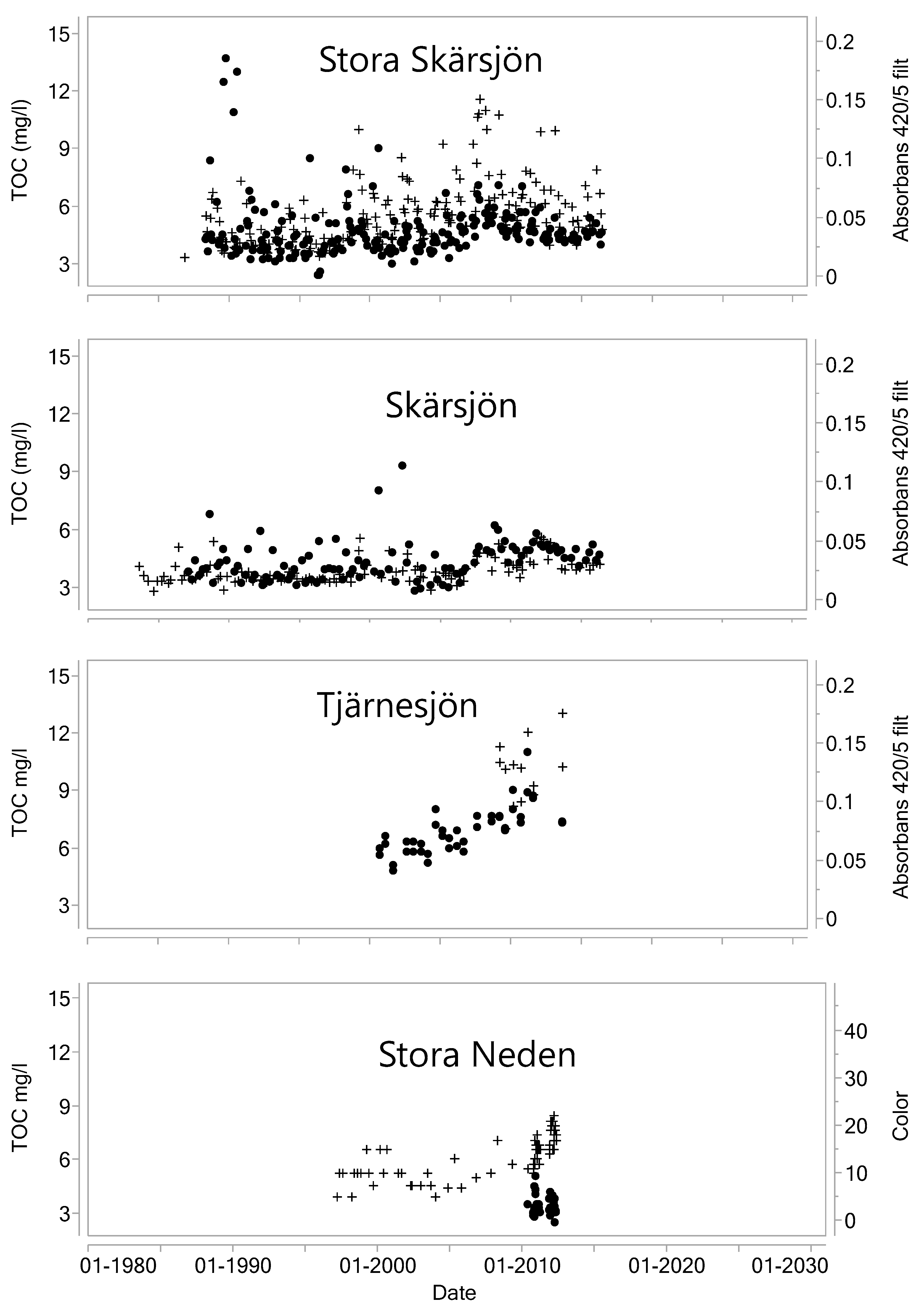

3.5. DOC Removal Efficiency

3.6. Adaptation and Resilience of the UF Process (UF-HF-P2)

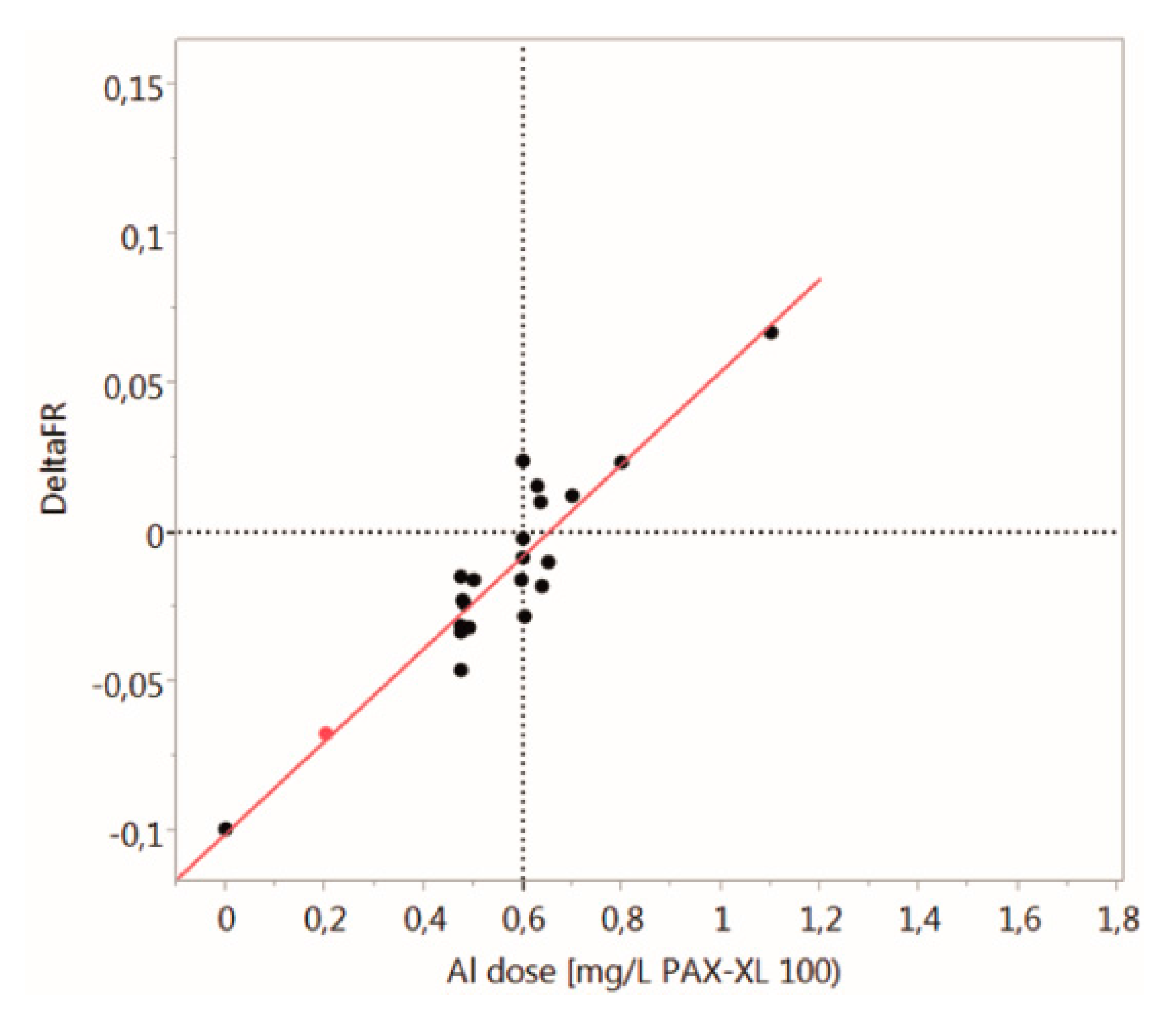

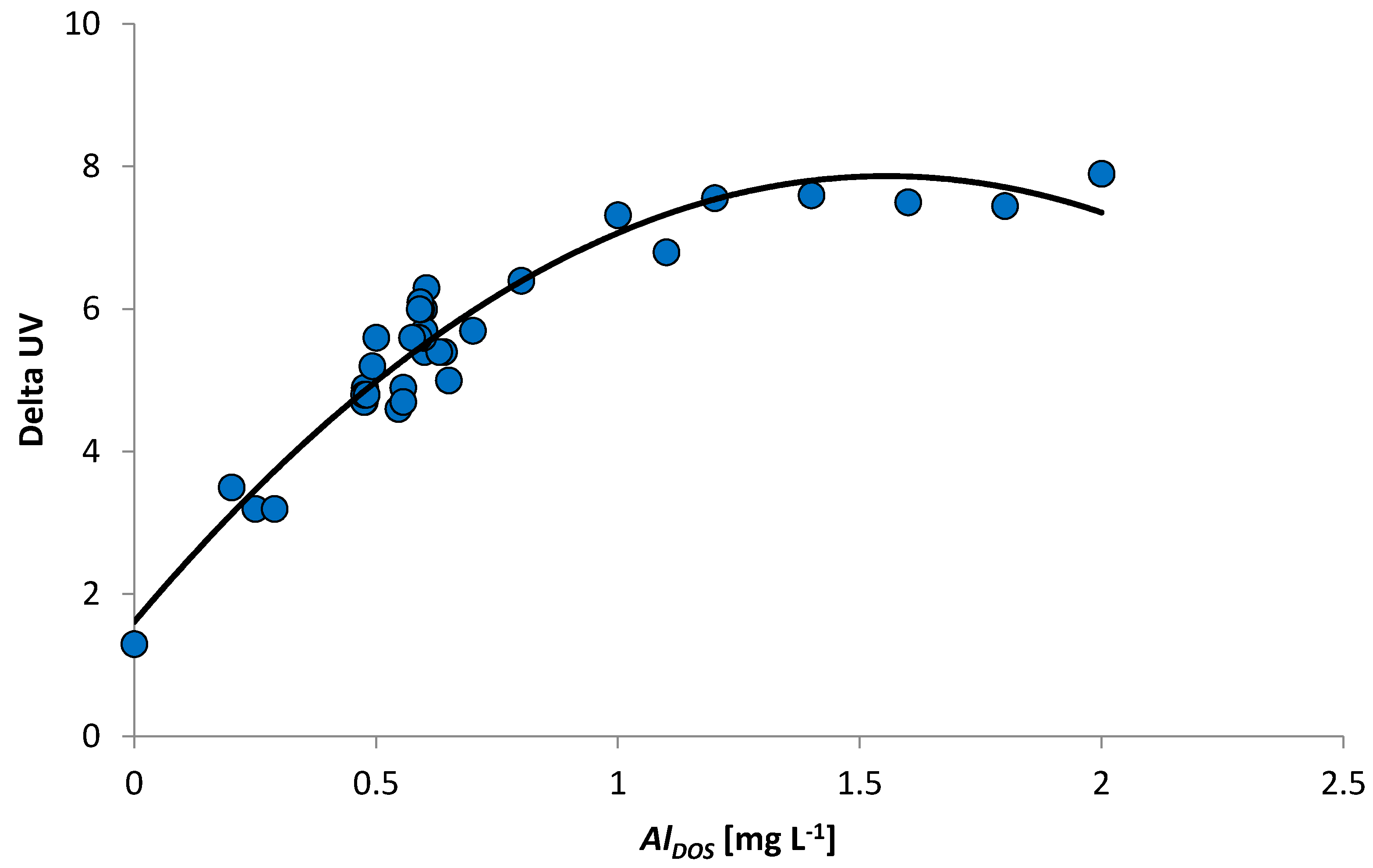

3.6.1. Determination of Maximum Coagulation Dosage

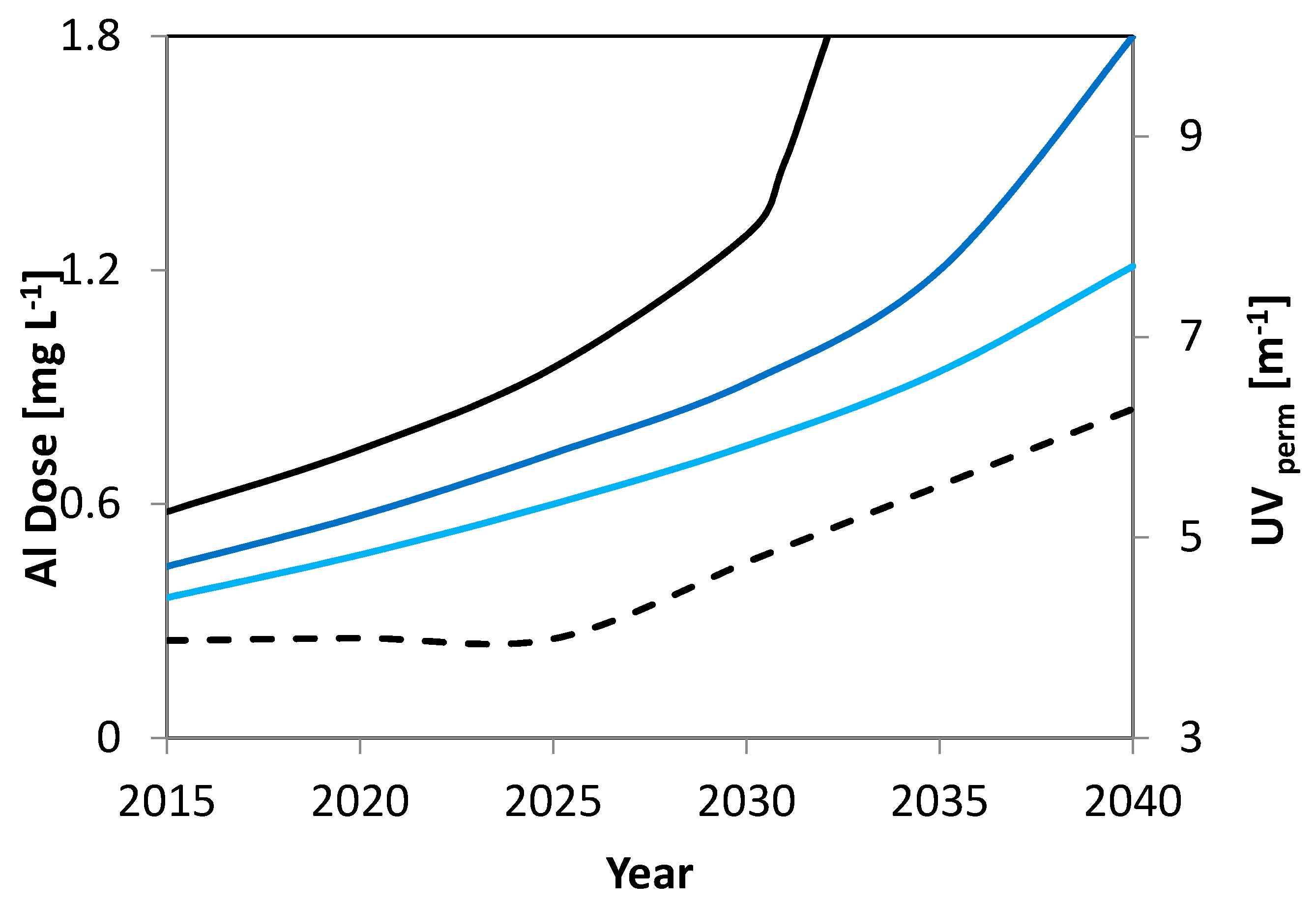

3.6.2. Scenario Analysis and Evaluation of UF Performance during Constant Rise of DOC

4. Conclusions

- The in-line coagulation/UF process produced stable water quality and facilitated the calculation of a dose–response curve for optimal dosing conditions (0.5–0.7 mg Al L−1) and potential boundaries (0.9–1.2 mg Al L−1).

- The secondary UF stage reached a critical level at 2.0 mg Al L−1, resulting in a distinct decrease in permeability during a single filtration cycle (from 740 to 150 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 @ 20 °C).

- Doubling the coagulant dosage (1.0 to 2.0 mg Al L−1) resulted in a limited decrease in UV absorbance in the permeate (0.55 m−1), raising concerns about the economic and operational aspects of process strategies to facilitate higher NOM removal.

- Systematic differences in the sensor and laboratory data must be taken into account for the different procedures to allow for the correct calculation of removal efficiency (quality control).

- The surface-water quality scenarios (up to the year 2040) indicated a potential increase in NOM, with significant effects on the coagulant dose and the quality of drinking water.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

| Term | Definition |

| BB | Building Blocks |

| CEB | Chemical Enhanced Backwashing |

| CEEF | Chemical Enhanced Forward Flushing |

| CIP | Cleaning-in-Place |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| Da | Dalton |

| DBP | Disinfection By-Product |

| DOC | Dissolved Organic Carbon |

| FNU | Formazin Nephelometric Unit |

| GW | Groundwater |

| HS | Humic Substances |

| LC-OCD | Liquid Chromatography–Organic Carbon Detection |

| LMWneutrals | Low Molecular Weight Neutrals |

| MW | Molecular Weight |

| MWCO | Molecular Weight Cut-Off |

| NF | Nanofiltration |

| NOM | Natural Organic Matter |

| PES | Polyethersulfone |

| SUVA | Specific Ultraviolet Absorbance |

| TMP | Transmembrane Pressure |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| UVabs | Absorption of UV light at 254 nm |

| UF | Ultrafiltration |

| WTP | Water Treatment Plant |

Appendix A

| Parameters | Unit | Range (UF-Stage 1) | Range (UF-Stage 2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | °C | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.5 |

| pH | (-) | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.2 |

| Turbidity | (FTU) | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 20.0 ± 2.9 |

| Hardness | ºdH | 1.5 ± 0.10 | 1.6 ± 0.15 |

| Alkalinity | (mg/L HCO3) | 19.0 ± 2.1 | 18.0 ± 3.0 |

| COD | (mg/L O2) | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 25.0 ± 7,5 |

| TOC | (mg C/L) | 2.9 ± 0.06 | 27.0 ± 3.2 |

| DOC | (mg C/L) | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.45 |

| UV254 | (/5 cm) | 0.380 ± 0.22 | 3.955 ± 3.3 |

| Pt-Co | (mg Pt/L) | 13 ± 1.0 | 15.0 ± 5.8 |

| Conductivity | (μS/cm) | 110 ± 6.9 | 110 ± 5.7 |

| Iron | (mg/L Fe) | 0.026 ± 0.02 | 0.57 ± 0.1 |

| Manganese | (mg/L Mn) | 0.035 ± 0.01 | 0.044 ± 0.01 |

| Parameters | Unit | UF Primary | UF Secondary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max. filtration time (tF) | (min) | 90 | 60 |

| Max. filtration volume | (m3) | 8.4 | 1.65 |

| Filtration flux (JF) | (L m−2 h−1) | 65–70 | 45 |

| VCF (cross flow velocity) | (m s−1) | - | 0.5 |

| R (recovery during filtration) | (%) | 100 | 100 |

| tBW (backwash time) | (s) | 30 | 30 |

| JBW (backwash flux) | (L m−2 h−1) | 250 | 250 |

| tCEFF (CEB interval) | (days) | 1.5 | 5 |

| CEB1 dosing solution (caustic) | (-) | 250–300 ppm NaOCl @ pH 12.2 with NaOH | 250–300 ppm NaOCl @ pH 12.2 with NaOH |

| CEB2 dosing solution (acidic) | (-) | 475 mg/L H2SO4 @ pH 2.4 | 475 mg/L H2SO4 @ pH 2.4 |

| tSOAK (Soak time CEB) | (min) | 10 | 10 |

| Parameters | Unit | UF Primary | UF Secondary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permeability | (L m−2 h−1 bar−1 @ 20 °C) | 350–380 | 600–220 |

| Transmembrane pressure | (bar) | 0.18–0.28 | 0.12–0.25 |

| Total number of CEBs | (-) | 267 | 37 |

| Module age before replacement | (months) | 12 | 14 |

| Total amount of filtration volume (feed water) | m3 | 57.150 1 | 2.155 2 |

| Parameter | Unit | Key Performance Values |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane Material | Sulfonated Polyethersulfone (PES) | |

| Max. backflush pressure | kPa | 300 |

| MWCO based on PEG 1 | kDa | 100 |

| Diameter (internal) | mm | 0.80 |

| Nominal pore size | nm | 20 |

| Membrane area | m2 | 55 |

| Number of fibres | ~15,000 | |

| Reduction of bacteria | log | 6 (Pseudomonas diminuta) |

| Reduction of virus | log | 4 (MS2 coliphages) |

| Module hydraulic diameter | mm | 220.0 |

| Module length | mm | 1537.5 |

| Year | GW DOC (mg L−1) | GW SUVA (L/mg*m) | GW UV abs (m−1) | Neden DOC (mg L−1) | Neden SUVA (L mg−1 m−1) | Neden UV (m−1) | GW Fraction (%) | UVabs MIX (m−1) | DOC MIX (mg L−1) | AlDOS S1 (mg L−1) | AlDOS S2 (mg L−1) | AlDOS S3 (mg L−1) | Delta UV 1 | Delta UV 1 | Uvabs Permeate (m−1) | Al DOS Max Dose (mg L−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 3 | 3.6 | 10.8 | 0.15 | 9.375 | 2.6475 | 0.58 | 5.40 | 5.40 | 3.97 | 0.58 | ||

| 2020 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 3.25 | 3.6 | 11.7 | 0.15 | 10.14 | 2.86 | 0.74 | 6.14 | 6.14 | 3.99 | 0.74 | ||

| 2025 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 12.6 | 0.15 | 10.905 | 3.0725 | 0.95 | 6.92 | 6.91 | 3.98 | 0.95 | ||

| 2030 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 3.75 | 3.6 | 13.5 | 0.15 | 11.67 | 3.285 | 1.29 | 6.92 | 7.68 | 3.98 | 0.95 | ||

| 2031 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 13.68 | 0.15 | 11.823 | 3.3275 | 1.48 | 6.92 | 7.84 | 3.97 | 0.95 | ||

| 2033 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 14.04 | 0.15 | 12.129 | 3.4125 | >2 | 6.92 | <8 | >4 | 0.95 | ||

| 2035 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 4 | 3.6 | 14.4 | 0.15 | 12.435 | 3.4975 | >2 | 6.92 | <8 | >4 | 0.95 | ||

| 2040 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 4.25 | 3.6 | 15.3 | 0.15 | 13.2 | 3.71 | >2 | 6.92 | <8 | >4 | 0.95 | ||

| 2015 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 10.44 | 0.2 | 8.612 | 2.45 | 0.44 | 4.64 | 3.96 | ||||

| 2020 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 3.15 | 3.6 | 11.34 | 0.2 | 9.332 | 2.65 | 0.57 | 5.35 | 3.98 | ||||

| 2025 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 12.24 | 0.2 | 10.052 | 2.85 | 0.73 | 6.10 | 3.95 | ||||

| 2030 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 3.65 | 3.6 | 13.14 | 0.2 | 10.772 | 3.05 | 0.91 | 6.78 | 3.98 | ||||

| 2035 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 14.04 | 0.2 | 11.492 | 3.25 | 1.2 | 7.53 | 3.95 | ||||

| 2040 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 4.15 | 3.6 | 14.94 | 0.2 | 12.212 | 3.45 | >2 | <8 | >4 | ||||

| 2015 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 10.44 | 0.25 | 8.155 | 2.3375 | 0.36 | 4.16 | 3.98 | ||||

| 2020 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 3.15 | 3.6 | 11.34 | 0.25 | 8.83 | 2.525 | 0.47 | 4.81 | 4.01 | ||||

| 2025 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 12.24 | 0.25 | 9.505 | 2.7125 | 0.6 | 5.50 | 4.00 | ||||

| 2030 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 3.65 | 3.6 | 13.14 | 0.25 | 10.18 | 2.9 | 0.75 | 6.18 | 3.99 | ||||

| 2035 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 14.04 | 0.25 | 10.855 | 3.0875 | 0.94 | 6.88 | 3.97 | ||||

| 2040 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.3 | 4.15 | 3.6 | 14.94 | 0.25 | 11.53 | 3.275 | 1.21 | 7.55 | 3.97 |

References

- Forsberg, C.; Petersen, R., Jr. A darkening of Swedish lakes due to increased humus inputs during the last 15 years. Verhandlungen des Internationalen Verein Limnologie 1990, 24, 289–292. [Google Scholar]

- Eikebrokk, B.; Vogt, R.; Liltved, H. NOM increase in Northern European source waters: Discussion of possible causes and impacts on coagulation/contact filtration processes. Water Sci. Technol. Water Supply 2004, 4, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Worrall, F.; Burt, T. Trends in DOC concentration in Great Britain. J. Hydrol. 2007, 346, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.D.; Monteith, D.T.; Cooper, D.M. Long-term increases in surface water dissolved organic carbon: Observations, possible causes and environmental impacts. Environ. Pollut. 2005, 137, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köhler, S.J.; Buffam, I.; Seibert, J.; Bishop, K.H.; Laudon, H. Dynamics of stream water TOC concentrations in a boreal headwater catchment: Controlling factors and implications for climate scenarios. J. Hydrol. 2009, 373, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpla, I.; Jung, A.-V.; Baures, E.; Clement, M.; Thomas, O. Impacts of climate change on surface water quality in relation to drinking water production. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavonen, E.E.; Kothawala, D.N.; Tranvik, L.J.; Gonsior, M.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Köhler, S.J. Tracking changes in the optical properties and molecular composition of dissolved organic matter during drinking water production. Water Res. 2015, 85, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavonen, E.E.; Gonsior, M.; Tranvik, L.J.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Köhler, S.J. Selective Chlorination of Natural Organic Matter: Identification of Previously Unknown Disinfection Byproducts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 2264–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacangelo, J.; DeMarco, J.; Owen, D.; Randtke, S. Selected processes for removing NOM: An overview. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 1995, 87, 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jacangelo, J.G.; Rhodes Trussell, R.; Watson, M. Role of membrane technology in drinking water treatment in the United States. Desalination 1997, 113, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, P.; Bilyk, K. Enhanced coagulation using a magnetic ion exchange resin. Water Res. 2002, 36, 4009–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilainen, A.; Iivari, P.; Sallanko, J.; Heiska, E.; Tuhkanen, T. The role of ozonation and activated carbon filtration in the natural organic matter removal from drinking water. Environ. Technol. 2006, 27, 1171–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zularisam, A.; Ismail, A.; Salim, R. Behaviours of natural organic matter in membrane filtration for surface water treatment—A review. Desalination 2006, 194, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Toor, R.; Mohseni, M. UV-H2O2 based AOP and its integration with biological activated carbon treatment for DBP reduction in drinking water. Chemosphere 2007, 66, 2087–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matilainen, A.; Sillanpää, M. Removal of organic matter from drinking water by advanced oxidation processes: A review. Chemosphere 2010, 80, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amy, G.L.; Alleman, B.C.; Cluff, C.B. Removal of dissolved organic matter by nanofiltration. J. Environ. Eng. 1990, 116, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, S.J.; Lavonen, E.E.; Keucken, A.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Spanjer, T.; Persson, K.M. Upgrading coagulation with hollow-fibre nanofiltration for improved organic matter removal during surface water treatment. Water Res. 2016, 89, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lidén, A.; Persson, K.M. Comparison between ultrafiltration and nanofiltration hollow-fiber membranes for removal of natural organic matter—A pilot study. J. Water Supply Res. Technol. AQUA 2015, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.-W.; Kang, L.-S. Application of combined coagulation-ultrafiltration membrane process for water treatment. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2003, 20, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, J.; Thompson, M.; Kelkar, U. The use of membrane filtration in conjunction with coagulation processes for improved NOM removal. Desalination 1995, 102, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.; Gray, S.; Naughton, R.; Bolto, B. Polysilicato-iron for improved NOM removal and membrane performance. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 280, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valinia, S.; Futter, M.; Fölster, J.; Cosby, B.; Rosén, P. Simple models to estimate historical and recent changes of total organic carbon concentrations in lakes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vattenkvalitet i Hallands Sjöar 2012. Resultat Från Omdrevsprogrammet 2007–2012 Länsstyrelsen i Hallands län Enheten för Naturvård & Miljöövervakning Meddelande; Vattenkvalitet i Hallands Sjöar: Hallands Sjöar, Swedish, 2013; ISSN 1101-1084. [Google Scholar]

- Finstad, A.; Blumentrath, S.; Tømmervik, H.; Andersen, T.; Larsen, S.; Tominaga, K.; Hessen, D.; De Wit, H. From greening to browning: Catchment vegetation development and reduced S-deposition promote organic carbon load on decadal time scales in Nordic lakes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keucken, A.; Heinicke, H. NOM characterization and removal by water treatment processes for drinking water and ultra pure process water. In Proceedings of the 4th IWA Speciality Conference on Natural Organic Matter, Costa Mesa, CA, USA, 27–29 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Keucken, A.; Donose, B.-C.; Persson, K.-M. Membrane fouling revealed by advanced autopsy. In Proceedings of the 8th Nordic Drinking Water Conference, Stockholm, Sweden, 18–20 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Keucken, A.; Wang, Y.; Tng, K.H.; Leslie, G.L.; Spanjer, T.; Köhler, S.J. Optimizing hollow fibre nanofiltration for organic matter rich lake water. Water 2016, 8, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.A.; Balz, A.; Abert, M.; Pronk, W. Characterisation of aquatic humic and non-humic matter with size-exclusion chromatography–organic carbon detection–organic nitrogen detection (LC-OCD-OND). Water Res. 2011, 45, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cory, R.; McKnight, D. Fluorescence spectroscopy reveals ubiquitous presence of oxidized and reduced quinones in dissolved organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 8142–8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohno, T.; Bro, R. Dissolved organic matter characterization using multiway spectral decomposition of fluorescence landscapes. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2006, 70, 2028–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlanti, E.; Woerz, K.; Geoffroy, L.; Lamotte, M. Dissolved organic matter fluorescence spectroscopy as a tool to estimate biological activity in a coastal zone submitted to anthropogenic inputs. Org. Geochem. 2000, 31, 1765–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidén, A.; Keucken, A.; Persson, K.M. Uses of fluorescence excitation-emissions indices in predicting water efficiency. J. Water Proc. Eng. 2017, 16, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, S.J.; Kothawala, D.; Futter, M.N.; Liungman, O.; Tranvik, L. In-Lake Processes Offset Increased Terrestrial Inputs of Dissolved Organic Carbon and Color to Lakes. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pilot Plant Type (Module Type) | Code | Scale | Start | End | Membrane Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UF HF one-stage (KOCH, HF 10-48 35) | UF-HF-P1 | Pilot | 1 June 2010 | 15 August 2011 | PES |

| UF-HF two-stage (Pentair, XIGA/AquaFlex) | UF-HF-P2 | Pilot | 1 January 2015 | Running | PES |

| NF (Pentair, HFW 1000) | NF-HF-P | Pilot | 2 November 2011 | 4 May 2012 | PES |

| UF-HF two-stage HF (Pentair, XIGA/AquaFlex) | UF-HF-F | Full | 15 February 2017 | Running | PES |

| Parameter | Raw Water | Drinking Water (Full-Scale WTP OLD) | UF without Coagulant | UF with Coagulant | NF50% | Target Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | RAW | DW | UF-HF-P1 | UF-HF-P1 | NF-HF-P | |

| COD (mg/L) | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ±0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | <4 limit |

| TOC (mg/L) | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 1.0 | |

| DOC (mg/L) | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 | |

| UV254 (L/m) | 8.7 ± 0.5 | 8.1 ± 0.5 | 7.3 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | |

| SUVA (L/mg, m) | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 2.8 | |

| Colour405nm (mg Pt/L) | 14.0 ± 1.2 | 13.0 ± 1.3 | 10.0 ± 0.7 | 2.5 ± 1.3 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | <15 limit <5 rec. |

| Turbidity (FNU) | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | <0.5 limit <0.1 rec. |

| pH | 7.6 ± 0.1 | 8.1 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 7.5–9 limit |

| Sample | UVRaw | UVLab1 unfilt. $ | UVLab2 unfilt. $ | UVLab3 filt. # | DOCLab3 | FILab3 | β/αLab3 | SUVALab3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw 2015 | 9.40 ± 0.46 | 9.23 ± 0.44 | 9.30 ± 0.38 | 8.57 ± 0.36 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Raw 2016 | 9.90 ± 0.17 | 9.30 ± 0.37 | 9.04 ± 0.48 | 8.60 ± 0.39 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Raw | 9.80 ± 0.23 | 9.40 ± 0.45 | 9.11 ± 0.41 | 8.59 ± 0.37 | 2.89 ± 0.07 | 1.47 ± 0.02 | 0.63 ± 0.01 | 2.97 ± 0.05 |

| Feed | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 5.93 ± 1.48 | 2.26 ± 0.30 | 1.58 ± 0.05 | 0.71 ± 0.03 | 2.51 ± 0.32 |

| Perm | 4.00 ± 0.78 | 4.00 ± 1.00 | 4.53 ± 1.02 | 4.41 ± 1.05 | 2.05 ± 0.22 | 1.61 ± 0.05 | 0.73 ± 0.03 | 2.12 ± 0.25 |

| DELTA | 59% | 57% | 50% | 48% | ||||

| Perm 2015 | 4.10 ± 0.74 | 4.03 ± 0.76 | 4.50 ± 1.09 | 4.23 ± 1.07 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Perm 2016 | 3.80 ± 0.34 | 4.01 ± 0.33 | 4.62 ± 0.95 | 4.43 ± 1.57 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Code | Sample | n | TOC (ppb-C) | DOC (ppb-C) | Biopolymers (ppb-C) | HS (ppb-C) | Building Blocks (ppb-C) | LMWneutrals (ppb-C) | LMWacids (ppb-C) | SUVA (L mg−1 m−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NF-HF-P | Lake | 3 | n.d. | 3235 ± 81 | 121 ± 8 | 2034 ± 54 | 568 ± 67 | 398 ± 33 | 9 ± 9 | 3.92 ± 0.03 |

| UF-HF-P1 | Lake | 4 | 3126 ± 202 | 3021 ± 204 | 100 ± 23 | 1919 ± 119 | 558 ± 49 | 401 ± 20 | 20 ± 9 | 3.82 ± 0.24 |

| UF-HF-P1 | GW | 2 | 600 ± 73 | 546 ± 213 | 5 ± 26 | 260 ± 85 | 0 ± 7 | 0 ± 2 | 0 ± 0 | 2.02 ± 0.18 |

| UF-HF-P1 | Feed | 4 | 2578 ± 402 | 2423 ± 343 | 72 ± 37 | 1603 ± 273 | 444 ± 57 | 344 ± 33 | 23 ± 11 | 3.65 ± 0.8 |

| UF-HF-P1 | Perm | 3 | 1655 ± 85 | 1714 ± 111 | 35 ± 10 | 855 ± 140 | 418 ± 28 | 315 ± 38 | 5 ± 7 | 2.62 ± 0.18 |

| UF-HF-F | Feed | 2 | 2541 ± 77 | 2337 ± 16 | 72 ± 10 | 1513 ± 10 | 409 ± 3 | 302 ± 5 | 42 ± 4 | 3.43 ± 0.22 |

| UF-HF-F | Perm | 2 | 1679 ± 34 | 1496 ± 24 | 27 ± 4 | 756 ± 53 | 424 ± 68 | 281 ± 1 | 17 ± 9 | 2.31 ± 0.26 |

| NF-HF-P | Feed | 3 | n.d. | 2593 ± 167 | 93 ± 2 | 1638 ± 55 | 508 ± 13 | 334 ± 19 | 0 ± 3 | 3.83 ± 0.04 |

| NF-HF-P | Perm | 3 | n.d. | 1158 ± 268 | 7 ± 3 | 592 ± 185 | 244 ± 56 | 210 ± 49 | 0 ± 3 | 3.09 ± 0.18 |

| NF-HF-P | Conc | 3 | n.d. | 4502 ± 1317 | 162 ± 99 | 2940 ± 980 | 804 ± 171 | 476 ± 123 | 1 ± 0 | 4.09 ± 0.16 |

| UF-HF-F | DV | 2 | 1742 ± 194 | 1473 ± 7 | 31 ± 1 | 754 ± 66 | 411 ± 70 | 272 ± 4 | 11 ± 5 | 1.88 ± 0.41 |

| Dose (mg Al L−1) | 1.00 | 1.40 | 1.60 | 1.80 | 2.00 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UF stage | UF1 | UF2 | UF1 | UF2 | UF1 | UF2 | UF1 | UF2 | UF1 | UF2 |

| Flux (LMH) | 49 | 33 | 49 | 33 | 49 | 33 | 49 | 33 | 49 | 33 |

| TMP (bar) | 0.16–0.19 | 0.05–0.14 | 0.17–0.19 | 0.06–0.17 | 0.16–0.18 | 0.06–0.22 | 0.16–0.18 | 0.06–0.24 | 0.16–0.19 | 0.06–0.25 |

| Permeability (L m−2 h−1 bar−1 @ 20 °C) | 420–360 | 760–320 | 420–360 | 760–240 | 420–370 | 740–200 | 420–360 | 740–170 | 420–360 | 740–150 |

| Feed water, UV254 (m−1) | 10.02 | n.a. | 9.9 | n.a. | 9.8 | n.a. | 9.7 | n.a. | 10.05 | n.a. |

| Permeate, UV254 (m−1) | 2.70 | 4.1 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.25 | 2.7 | 2.15 | 2.8 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keucken, A.; Heinicke, G.; Persson, K.M.; Köhler, S.J. Combined Coagulation and Ultrafiltration Process to Counteract Increasing NOM in Brown Surface Water. Water 2017, 9, 697. https://doi.org/10.3390/w9090697

Keucken A, Heinicke G, Persson KM, Köhler SJ. Combined Coagulation and Ultrafiltration Process to Counteract Increasing NOM in Brown Surface Water. Water. 2017; 9(9):697. https://doi.org/10.3390/w9090697

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeucken, Alexander, Gerald Heinicke, Kenneth M. Persson, and Stephan J. Köhler. 2017. "Combined Coagulation and Ultrafiltration Process to Counteract Increasing NOM in Brown Surface Water" Water 9, no. 9: 697. https://doi.org/10.3390/w9090697

APA StyleKeucken, A., Heinicke, G., Persson, K. M., & Köhler, S. J. (2017). Combined Coagulation and Ultrafiltration Process to Counteract Increasing NOM in Brown Surface Water. Water, 9(9), 697. https://doi.org/10.3390/w9090697