Farmers’ Perceptions about Adaptation Practices to Climate Change and Barriers to Adaptation: A Micro-Level Study in Ghana

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Design and Study Area

2.2. Statistical Analysis

| Variables | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Age (15–34 years = 1; 35–54 years = 2; above 55 years = 3) | 2.26 | 0.73 |

| Education level (literate = 1; illiterate = 0) | 0.21 | 0.41 |

| Farm size (continuous) | 4.95 | 1.70 |

| Household size (continuous) | 8.20 | 5.12 |

| Family labor (continuous) | 4.65 | 3.04 |

| Annual farm income—Ghana cedi (continuous) | 949.42 | 1909.55 |

| Annual off-farm income—Ghana cedi (continuous) | 797.20 | 2459.92 |

| Farmer’s adaptation (adapted = 1; not adapted = 0) | 0.67 | 0.47 |

- PCI = Problem Confrontation Index;

- Pn = Number of respondents who graded the constraint as no problem;

- Pl = Number of respondents who graded the constraint as low;

- Pm = Number of respondents who graded the constraint as moderate;

- Ph = Number of respondents who graded the constraint as high.

3. Results

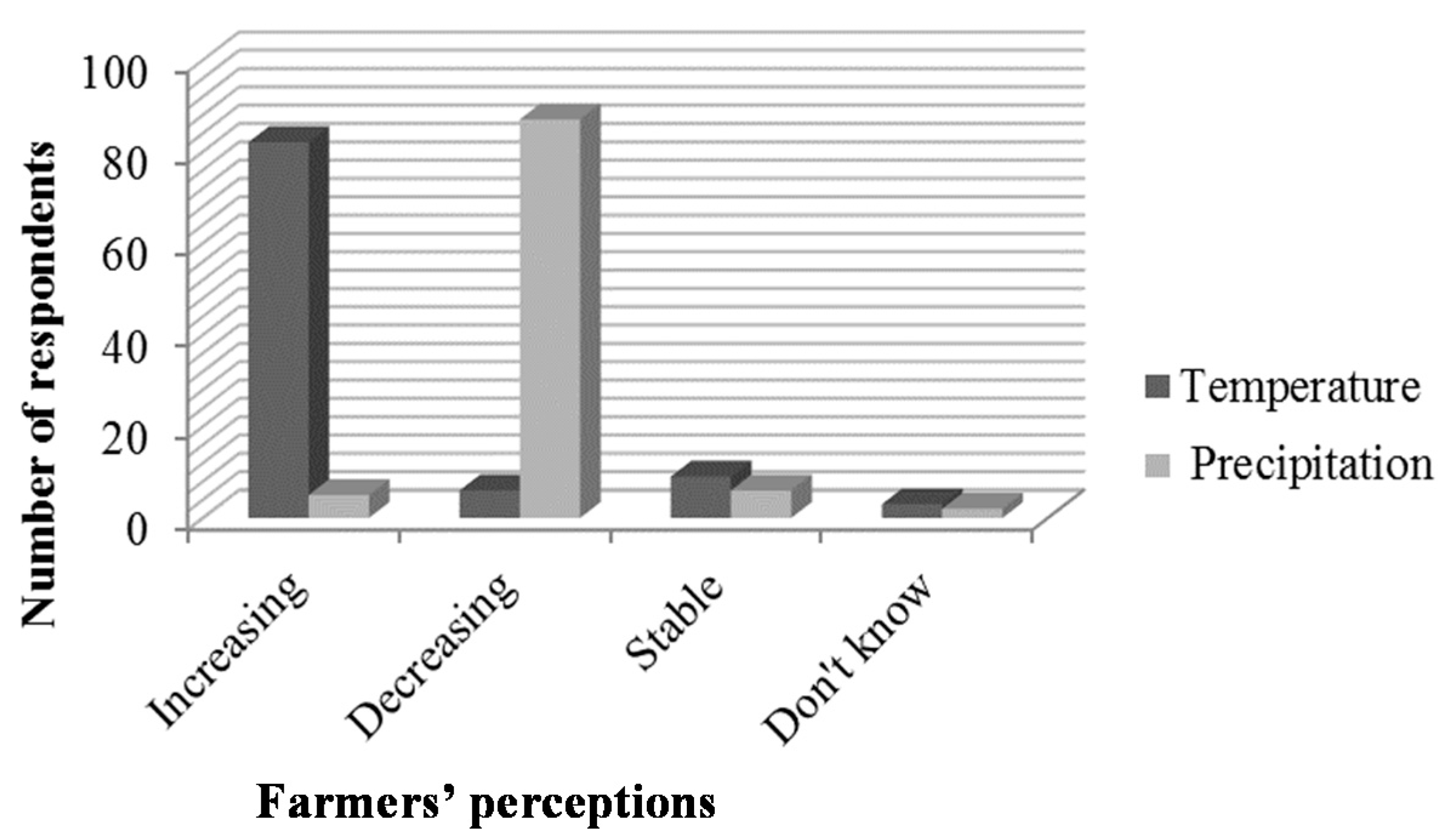

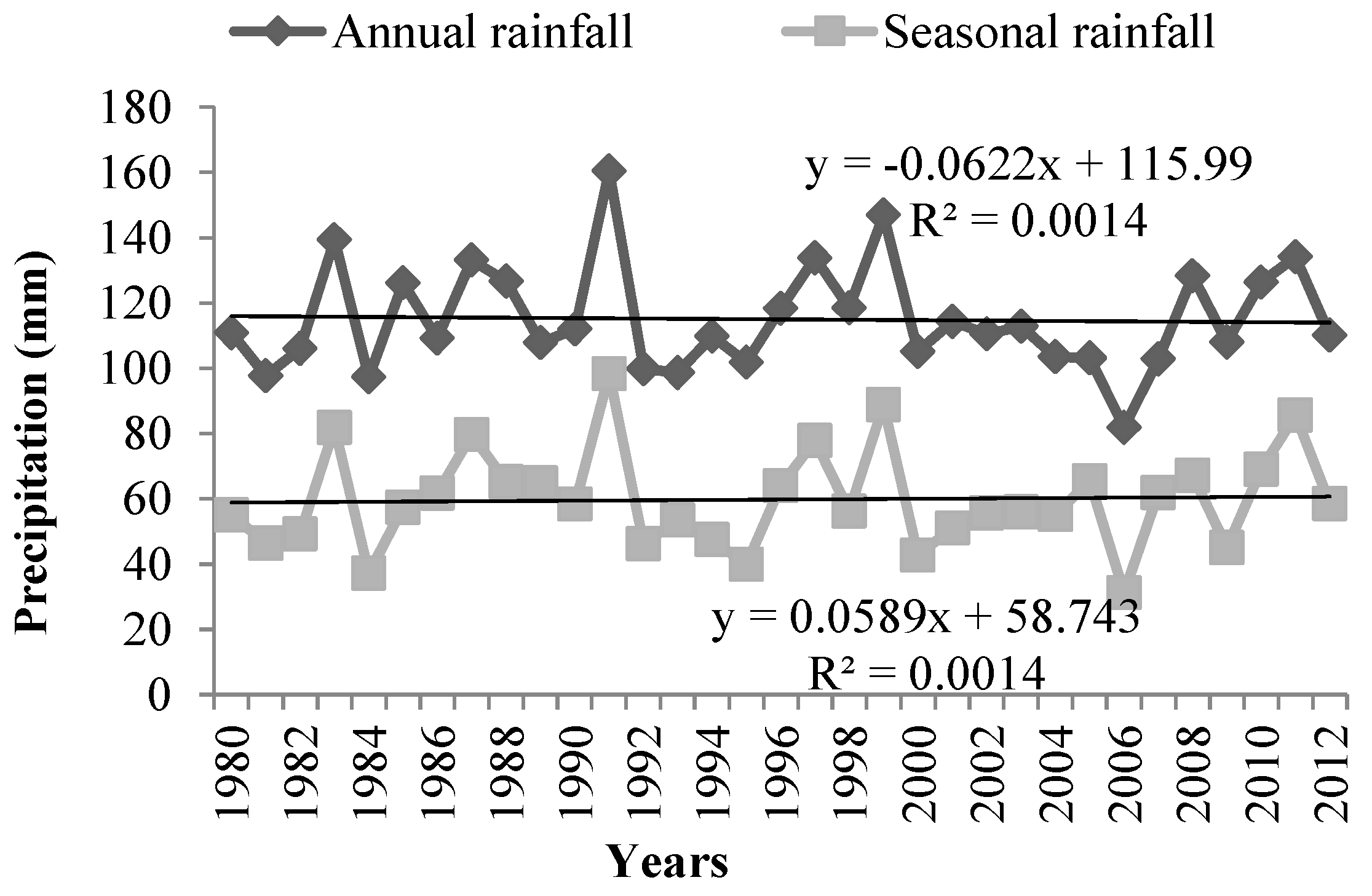

3.1. Farmers’ Perceptions of Long-Term Temperature and Rainfall Changes

3.2. Farmers’ Perceived Causes of Climatic Variability on Agriculture

| Cause Variable | Percentage of Respondents |

|---|---|

| Deforestation | 14.0 |

| Bush fires | 51.0 |

| More than one cause | 23.3 |

| Gods/ancestral spirits | 9.3 |

| Do not know | 2.4 |

| Total | 100 |

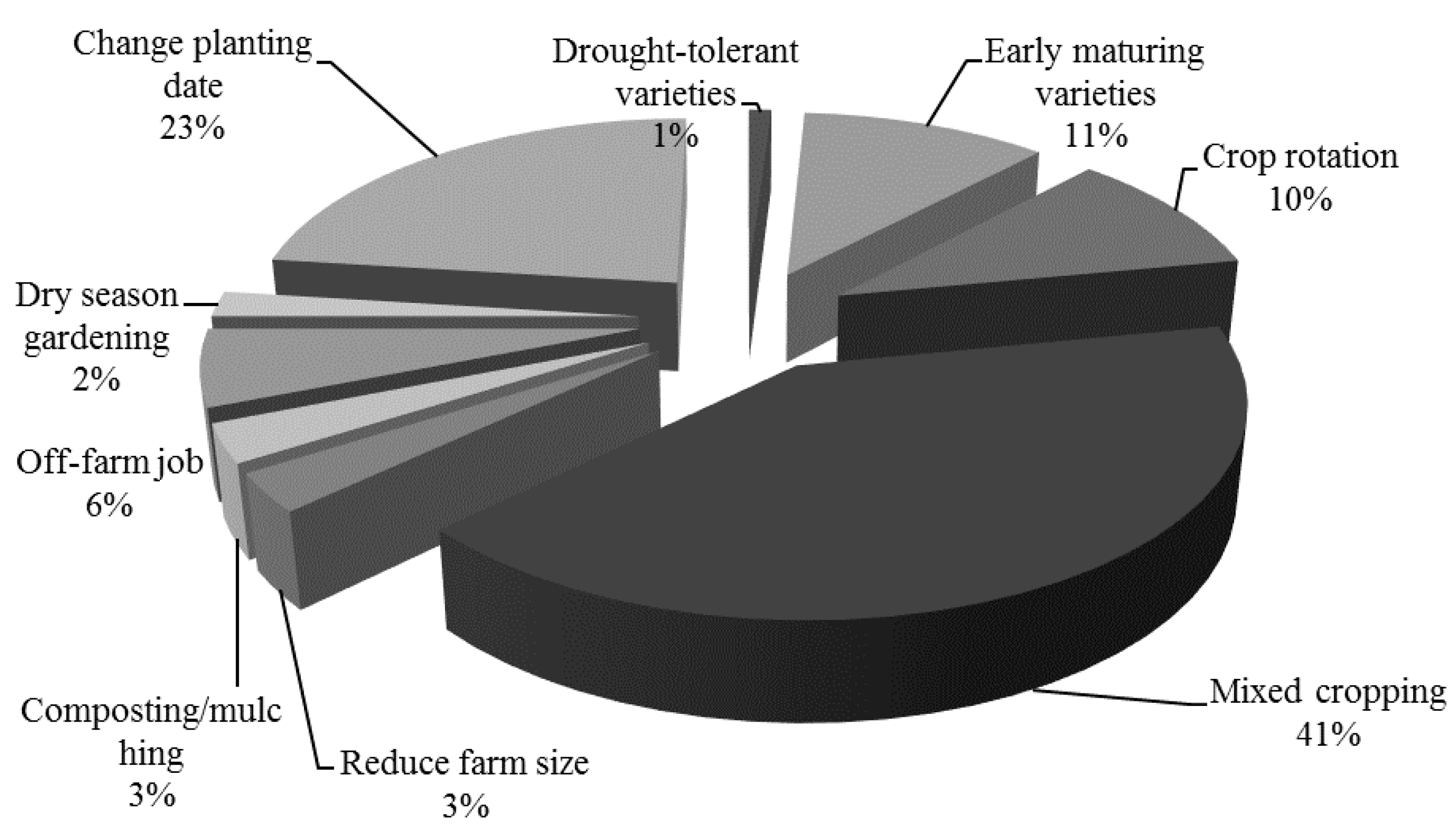

3.3. Farmers’ Adaptation to Climate Change

| Variable | Percentage of Respondents |

|---|---|

| a. Adaptation classification | |

| Adapted | 67 |

| Not adapted | 33 |

| b. Reasons for adaptation | |

| Reduce effects of flood | 7 |

| Reduce effects of drought | 20 |

| Reduce effects of dry spell | 73 |

3.4. Farmer-Perceived Importance of Adaptation Practices

| Adaptation Practice | Frequency by Each Level of Importance | WAI | Rank | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highly Important | Moderately Important | Less Important | Not Important | |||

| Improved crop varieties | 35 | 48 | 14 | 3 | 2.15 | 1 |

| Irrigation | 30 | 51 | 17 | 8 | 2.09 | 2 |

| Crop diversification | 14 | 76 | 8 | 2 | 2.02 | 3 |

| Farm diversification | 7 | 67 | 23 | 3 | 1.78 | 4 |

| Change of planting date | 10 | 44 | 26 | 20 | 1.44 | 5 |

| Income generating activities | 3 | 20 | 28 | 49 | 0.77 | 6 |

| Agroforestry practice | 0 | 9 | 56 | 35 | 0.74 | 7 |

3.5. Perceived Constraints to Adaptation to Climate Change

| Constraints to Adoption | Degree of Constraint | PCI | Rank | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Moderate | Low | No Problem | |||

| Unpredictable weather | 35 | 48 | 14 | 3 | 215 | 1 |

| High cost of farm inputs | 14 | 76 | 8 | 2 | 202 | 2 |

| Lack of access to timely weather information | 7 | 67 | 23 | 3 | 178 | 3 |

| Lack of access to water resources (e.g., dams) | 10 | 44 | 26 | 20 | 144 | 4 |

| Lack of access to credit facilities | 2 | 32 | 11 | 55 | 81 | 5 |

| Lack of access to agricultural subsidies | 3 | 20 | 28 | 49 | 77 | 6 |

| Poor soil fertility | 0 | 9 | 56 | 35 | 74 | 7 |

| Limited access to agricultural extension officers | 3 | 19 | 7 | 71 | 54 | 8 |

| Limited access to agricultural markets | 0 | 0 | 24 | 76 | 24 | 9 |

| Inadequate farm labor | 0 | 1 | 19 | 80 | 21 | 10 |

| Limited farm size | 0 | 0 | 13 | 87 | 13 | 11 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- USAID. Ghana Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment. Available online: http://www.encapafrica.org/documents/biofor/Climate%20Change%20Assessment_Ghana_%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2015).

- Jung, G.; Kunstmann, H. High-resolution regional climate modelling for the Volta Basin of West Africa. J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laux, P.; Kunstmann, H.; Bárdossy, A. Predicting the regional onset of the rainy season in West Africa. Int. J. Climatol. 2008, 28, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laube, W.; Schraven, B.; Awo, M. Smallholder adaptation to climate change: Dynamics and limits in Northern Ghana. Clim. Chang. 2009, 111, 753–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farauta, B.K.; Egbule, C.L.; Idrisa, Y.L.; Agu, V.C. Farmers’ Perceptions of Climate Change and Adaptation Strategies in Northern Nigeria: An Empirical Assessment. Available online: http://www.atpsnet.org/Files/rps15.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2015).

- Adger, W.N.; Huq, S.; Brown, K.; Conway, D.; Hulme, M. Adaptation to Climate Change in the Developing World. Available online: http://www.glerl.noaa.gov/seagrant/ClimateChangeWhiteboard/Resources/Uncertainty/climatech/adger03PR.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2015).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fosu-Mensah, B.Y.; Vlek, P.L.G.; MacCarthy, D.S. Farmers’ perceptions and adaptation to climate change: A case study of Sekyeredumase district in Ghana. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2012, 14, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhamo, N.; Daniel, M.; Fritz, O.T. Adaptation strategies to climate extremes among smallholder farmers: A case of cropping practices in the Volta Region of Ghana. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonya, J.S.; Syndikus, K.; Kroschel, J. Farmers’ perceptions of and copping strategies to climate change: Evidence from six agro-ecological zones of Uganda. J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apata, T.G. Factors Influencing the Perception and Choice of Adaptation Measures to Climate Change among Farmers in Nigeria. Evidence From farm Households in Southwest Nigeria. Available online: http://businessperspectives.org/journals_free/ee/2011/ee_2011_04_Apata.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2015).

- Nhemachena, C.; Hassan, R. Micro-Level Analysis of Farmers’ Adaptation to Climate Change in Southern Africa. Available online: http://cdm15738.contentdm.oclc.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/39726/filename/39727.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2015).

- Kusakari, Y.; Asubonteng, K.O.; Jasaw, G.S.; Dayour, F.; Dzivenu, T.; Lolig, V.; Donkoh, S.A.; Obeng, F.K.; Gandaa, B.; Kranjac-Berisavljevic, G. Farmer-perceived effects of climate change on livelihoods in Wa West District, Upper West Region of Ghana. J. Disaster Res. 2014, 9, 516–528. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, P.H.; Norman, D.A. Human Information Processing: An Introduction to Psychology. Available online: http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/courses/spsci/audper/SDT%20Lindsay%20&%20Norman%20App%20B.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2015).

- Harig, T.; Kaiser, F.G.; Bowler, P.A. Psychological restoration in nature as a positive motivation for ecological behavior. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment, Science and Technology (MEST) of Ghana. Ghana Goes for Green Growth: National Engagement on Climate Change. Available online: http://prod-http-80-800498448.us-east-1.elb.amazonaws.com/w/images/2/29/GhanaGreen.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2015).

- Luni, P.; Maharjan, K.L.; Joshi, N.P. Perceptions and realities of climate change among the Chepong Communities in rural mid-hills of Nepal. J. Contemp. India Stud. Space Soc. 2012, 2, 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Di Falco, S.; Yesuf, M.; Kohlin, G.; Ringler, C. Estimating the impact of climate change on agriculture in low-income countries: Household level evidence from the Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2012, 52, 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.E.; Pascual, U.; Hodgkin, T. Utilizing and conserving agrobiodiversity in agricultural landscapes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 121, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndamani, F.; Watanabe, T. Influences of rainfall on crop production and suggestions for adaptation. Int. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 5, 367–374. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). Population by Region, District, Locality of Residence, Age Groups and Sex, 2010. Available online: http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/population_by_region_district_locality_of_residence_age_groups_and_sex,_2010.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2015).

- Uddin, M.N.; Bokelmann, W.; Entsminger, J.S. Factors affecting farmers’ adaptation strategies to environmental degradation and climate change effects: A farm level study in Bangladesh. Climate 2014, 2, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, R.P.; Cockfield, G.; Maraseni, T.N. Perceived community-based flood adaptation strategies under climate change in Nepal. Int. J. Glob. Warm. 2014, 6, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, O.; Mbow, C.; Reenberg, A.; Diouf, A. Farmers’ perceptions of climate change and agricultural adaptation strategies in rural Sahel. Environ. Manag. 2009, 43, 804–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2007; Parry, M.L., Canziani, O.F., Palutik, J.P., Linden, P.J., Hanson, C.E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kandlinkar, M.; Risbey, J. Agricultural impacts of climate change: If adaptation is the answer, what is the question? Clim. Chang. 2000, 45, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ndamani, F.; Watanabe, T. Farmers’ Perceptions about Adaptation Practices to Climate Change and Barriers to Adaptation: A Micro-Level Study in Ghana. Water 2015, 7, 4593-4604. https://doi.org/10.3390/w7094593

Ndamani F, Watanabe T. Farmers’ Perceptions about Adaptation Practices to Climate Change and Barriers to Adaptation: A Micro-Level Study in Ghana. Water. 2015; 7(9):4593-4604. https://doi.org/10.3390/w7094593

Chicago/Turabian StyleNdamani, Francis, and Tsunemi Watanabe. 2015. "Farmers’ Perceptions about Adaptation Practices to Climate Change and Barriers to Adaptation: A Micro-Level Study in Ghana" Water 7, no. 9: 4593-4604. https://doi.org/10.3390/w7094593

APA StyleNdamani, F., & Watanabe, T. (2015). Farmers’ Perceptions about Adaptation Practices to Climate Change and Barriers to Adaptation: A Micro-Level Study in Ghana. Water, 7(9), 4593-4604. https://doi.org/10.3390/w7094593